Archive

Columbia Data Science course, week 5: GetGlue, time series, financial modeling, advanced regression, and ethics

I was happy to be giving Rachel Schutt’s Columbia Data Science course this week, where I discussed time series, financial modeling, and ethics. I blogged previous classes here.

The first few minutes of class were for a case study with GetGlue, a New York-based start-up that won the mashable breakthrough start-up of the year in 2011 and is backed by some of the VCs that also fund big names like Tumblr, etsy, foursquare, etc. GetGlue is part of the social TV space. Lead Scientist, Kyle Teague, came to tell the class a little bit about GetGlue, and some of what he worked on there. He also came to announce that GetGlue was giving the class access to a fairly large data set of user check-ins to tv shows and movies. Kyle’s background is in electrical engineering, he placed in the 2011 KDD cup (which we learned about last week from Brian), and he started programming when he was a kid.

GetGlue’s goal is to address the problem of content discovery within the movie and tv space, primarily. The usual model for finding out what’s on TV is the 1950’s TV Guide schedule, and that’s still how we’re supposed to find things to watch. There are thousands of channels and it’s getting increasingly difficult to find out what’s good on. GetGlue wants to change this model, by giving people personalized TV recommendations and personalized guides. There are other ways GetGlue uses Data Science but for the most part we focused on how this the recommendation system works. Users “check-in” to tv shows, which means they can tell people they’re watching a show. This creates a time-stamped data point. They can also do other actions such as like, or comment on the show. So this is a -tuple: {user, action, object} where the object is a tv show or movie. This induces a bi-partite graph. A bi-partite graph or network contains two types of nodes: users and tv shows. An edges exist between users and an tv shows, but not between users and users or tv shows and tv shows. So Bob and Mad Men are connected because Bob likes Mad Men, and Sarah and Mad Men and Lost are connected because Sarah liked Mad Men and Lost. But Bob and Sarah aren’t connected, nor are Mad Men and Lost. A lot can be learned from this graph alone.

But GetGlue finds ways to create edges between users and between objects (tv shows, or movies.) Users can follow each other or be friends on GetGlue, and also GetGlue can learn that two people are similar[do they do this?]. GetGlue also hires human evaluators to make connections or directional edges between objects. So True Blood and Buffy the Vampire Slayer might be similar for some reason and so the humans create an edge in the graph between them. There were nuances around the edge being directional. They may draw an arrow pointing from Buffy to True Blood but not vice versa, for example, so their notion of “similar” or “close” captures both content and popularity. (That’s a made-up example.) Pandora does something like this too.

Another important aspect is time. The user checked-in or liked a show at a specific time, so the -tuple extends to have a time-stamp: {user,action,object,timestamp}. This is essentially the data set the class has access to, although it’s slightly more complicated and messy than that. Their first assignment with this data will be to explore it, try to characterize it and understand it, gain intuition around it and visualize what they find.

Students in the class asked him questions around topics of the value of formal education in becoming a data scientist (do you need one? Kyle’s time spent doing signal processing in research labs was valuable, but so was his time spent coding for fun as a kid), what would be messy about a data set, why would the data set be messy (often bugs in the code), how would they know? (their QA and values that don’t make sense), what language does he use to prototype algorithms (python), how does he know his algorithm is good.

Then it was my turn. I started out with my data scientist profile:

As you can see, I feel like I have the most weakness in CS. Although I can use python pretty proficiently, and in particular I can scrape and parce data, prototype models, and use matplotlib to draw pretty pictures, I am no java map-reducer and I bow down to those people who are. I am also completely untrained in data visualization but I know enough to get by and give presentations that people understand.

Thought Experiment

I asked the students the following question:

What do you lose when you think of your training set as a big pile of data and ignore the timestamps?

They had some pretty insightful comments. One thing they mentioned off the bat is that you won’t know cause and effect if you don’t have any sense of time. Of course that’s true but it’s not quite what I meant, so I amended the question to allow you to collect relative time differentials, so “time since user last logged in” or “time since last click” or “time since last insulin injection”, but not absolute timestamps.

What I was getting at, and what they came up with, was that when you ignore the passage of time through your data, you ignore trends altogether, as well as seasonality. So for the insulin example, you might note that 15 minutes after your insulin injection your blood sugar goes down consistently, but you might not notice an overall trend of your rising blood sugar over the past few months if your dataset for the past few months has no absolute timestamp on it.

This idea, of keeping track of trends and seasonalities, is very important in financial data, and essential to keep track of if you want to make money, considering how small the signals are.

How to avoid overfitting when you model with time series

After discussing seasonality and trends in the various financial markets, we started talking about how to avoid overfitting your model.

Specifically, I started out with having a strict concept of in-sample (IS) and out-of-sample (OOS) data. Note the OOS data is not meant as testing data- that all happens inside OOS data. It’s meant to be the data you use after finalizing your model so that you have some idea how the model will perform in production.

Next, I discussed the concept of causal modeling. Namely, we should never use information in the future to predict something now. Similarly, when we have a set of training data, we don’t know the “best fit coefficients” for that training data until after the last timestamp on all the data. As we move forward in time from the first timestamp to the last, we expect to get different sets of coefficients as more events happen.

One consequence of this is that, instead of getting on set of coefficients, we actually get an evolution of each coefficient. This is helpful because it gives us a sense of how stable those coefficients are. In particular, if one coefficient has changed sign 10 times over the training set, then we expect a good estimate for it is zero, not the so-called “best fit” at the end of the data.

One last word on causal modeling and IS/OOS. It is consistent with production code. Namely, you are always acting, in the training and in the OOS simulation, as if you’re running your model in production and you’re seeing how it performs. Of course you fit your model in sample, so you expect it to perform better there than in production.

Another way to say this is that, once you have a model in production, you will have to make decisions about the future based only on what you know now (so it’s causal) and you will want to update your model whenever you gather new data. So your coefficients of your model are living organisms that continuously evolve.

Submodels of Models

We often “prepare” the data before putting it into a model. Typically the way we prepare it has to do with the mean or the variance of the data, or sometimes the log (and then the mean or the variance of that transformed data).

But to be consistent with the causal nature of our modeling, we need to make sure our running estimates of mean and variance are also causal. Once we have causal estimates of our mean and variance $\sigma_y^2$, we can normalize the next data point with these estimates just like we do to get from a gaussian distribution to the normal gaussian distribution:

Of course we may have other things to keep track of as well to prepare our data, and we might run other submodels of our model. For example we may choose to consider only the “new” part of something, which is equivalent to trying to predict something like instead of

Or we may train a submodel to figure out what part of

predicts

so a submodel which is a univariate regression or something.

There are lots of choices here, but the point is it’s all causal, so you have to be careful when you train your overall model how to introduce your next data point and make sure the steps are all in order of time, and that you’re never ever cheating and looking ahead in time at data that hasn’t happened yet.

Financial time series

In finance we consider returns, say daily. And it’s not percent returns, actually it’s log returns: if denotes a close on day

then the return that day is defined as

See more about this here.

So if you start with S&P closing levels:

Then you get the following log returns:

What’s that mess? It’s crazy volatility caused by the financial crisis. We sometimes (not always) want to account for that volatility by normalizing with respect to it (described above). Once we do that we get something like this:

Which is clearly better behaved. Note this process is discussed in this post.

We could also normalize with respect to the mean, but we typically assume the mean of daily returns is 0, so as to not bias our models on short term trends.

Financial Modeling

One thing we need to understand about financial modeling is that there’s a feedback loop. If you find a way to make money, it eventually goes away- sometimes people refer to this as the fact that the “market learns over time”.

One way to see this is that, in the end, your model comes down to knowing some price is going to go up in the future, so you buy it before it goes up, you wait, and then you sell it at a profit. But if you think about it, your buying it has actually changed the process, and decreased the signal you were anticipating. That’s how the market learns – it’s a combination of a bunch of algorithms anticipating things and making them go away.

The consequence of this learning over time is that the existing signals are very weak. We are happy with a 3% correlation for models that have a horizon of 1 day (a “horizon” for your model is how long you expect your prediction to be good). This means not much signal, and lots of noise! In particular, lots of the machine learning “metrics of success” for models, such as measurements of precision or accuracy, are not very relevant in this context.

So instead of measuring accuracy, we generally draw a picture to assess models, namely of the (cumulative) PnL of the model. This generalizes to any model as well- you plot the cumulative sum of the product of demeaned forecast and demeaned realized. In other words, you see if your model consistently does better than the “stupidest” model of assuming everything is average.

If you plot this and you drift up and to the right, you’re good. If it’s too jaggedy, that means your model is taking big bets and isn’t stable.

Why regression?

From above we know the signal is weak. If you imagine there’s some complicated underlying relationship between your information and the thing you’re trying to predict, get over knowing what that is – there’s too much noise to find it. Instead, think of the function as possibly complicated, but continuous, and imagine you’ve written it out as a Taylor Series. Then you can’t possibly expect to get your hands on anything but the linear terms.

Don’t think about using logistic regression, either, because you’d need to be ignoring size, which matters in finance- it matters if a stock went up 2% instead of 0.01%. But logistic regression forces you to have an on/off switch, which would be possible but would lose a lot of information. Considering the fact that we are always in a low-information environment, this is a bad idea.

Note that although I’m claiming you probably want to use linear regression in a noisy environment, the actual terms themselves don’t have to be linear in the information you have. You can always take products of various terms as x’s in your regression. but you’re still fitting a linear model in non-linear terms.

Advanced regression

The first thing I need to explain is the exponential downweighting of old data, which I already used in a graph above, where I normalized returns by volatility with a decay of 0.97. How do I do this?

Working from this post again, the formula is given by essentially a weighted version of the normal one, where I weight recent data more than older data, and where the weight of older data is a power of some parameter which is called the decay. The exponent is the number of time intervals since that data was new. Putting that together, the formula we get is:

We are actually dividing by the sum of the weights, but the weights are powers of some number s, so it’s a geometric sum and the sum is given by

One cool consequence of this formula is that it’s easy to update: if we have a new return to add to the series, then it’s not hard to show we just want

In fact this is the general rule for updating exponential downweighted estimates, and it’s one reason we like them so much- you only need to keep in memory your last estimate and the number

How do you choose your decay length? This is an art instead of a science, and depends on the domain you’re in. Think about how many days (or time periods) it takes to weight a data point at half of a new data point, and compare that to how fast the market forgets stuff.

This downweighting of old data is an example of inserting a prior into your model, where here the prior is “new data is more important than old data”. What are other kinds of priors you can have?

Priors

Priors can be thought of as opinions like the above. Besides “new data is more important than old data,” we may decide our prior is “coefficients vary smoothly.” This is relevant when we decide, say, to use a bunch of old values of some time series to help predict the next one, giving us a model like:

which is just the example where we take the last two values of the time series $F$ to predict the next one. But we could use more than two values, of course.

[Aside: in order to decide how many values to use, you might want to draw an autocorrelation plot for your data.]

The way you’d place the prior about the relationship between coefficients (in this case consecutive lagged data points) is by adding a matrix to your covariance matrix when you perform linear regression. See more about this here.

Ethics

I then talked about modeling and ethics. My goal is to get this next-gen group of data scientists sensitized to the fact that they are not just nerds sitting in the corner but have increasingly important ethical questions to consider while they work.

People tend to overfit their models. It’s human nature to want your baby to be awesome. They also underestimate the bad news and blame other people for bad news, because nothing their baby has done or is capable of is bad, unless someone else made them do it. Keep these things in mind.

I then described what I call the deathspiral of modeling, a term I coined in this post on creepy model watching.

I counseled the students to

- try to maintain skepticism about their models and how their models might get used,

- shoot holes in their own ideas,

- accept challenges and devise tests as scientists rather than defending their models using words – if someone thinks they can do better, than let them try, and agree on an evaluation method beforehand,

- In general, try to consider the consequences of their models.

I then showed them Emanuel Derman’s Hippocratic Oath of Modeling, which was made for financial modeling but fits perfectly into this framework. I discussed the politics of working in industry, namely that even if they are skeptical of their model there’s always the chance that it will be used the wrong way in spite of the modeler’s warnings. So the Hippocratic Oath is, unfortunately, insufficient in reality (but it’s a good start!).

Finally, there are ways to do good: I mentioned stuff like DataKind. There are also ways to be transparent: I mentioned Open Models, which is so far just an idea, but Victoria Stodden is working on RunMyCode, which is similar and very awesome.

Next-Gen Data Scientists

This is written by Rachel Schutt and crossposted from her Columbiadatascience blog

Data is information and is extremely powerful. Models and algorithms that use data can literally change the world. Quantitatively-minded people have always been able to solve important problems, so this is nothing new, and there’s always been data, so this is nothing new.

What is new is the massive amounts of data we have on all aspects of our lives, from the micro to the macro. The data we have from government, finance, education, the environment, social welfare, health, entertainment, the internet will be used to make policy-decisions and to build products back into the fabric of our culture.

I want you, my students, to be the ones doing it. I look around the classroom and see a group of thoughtful, intelligent people who want to do good, and are absolutely capable of doing it.

I don’t call myself a “data scientist”. I call myself a statistician. I refuse to be called a data scientist because as it’s currently used, it’s a meaningless, arbitrary marketing term. However, the existence of the term, and apparent “sexiness” of the profession draws attention to data and opens up opportunities. So we need Next-Gen Data Scientists. That’s you! Here’s what I mean when I say Next-Gen Data Scientist:

- Next-Gen Data Scientists have humility. They don’t lie about their credentials and they don’t spend most of their efforts on self-promotion.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists have integrity. Their work is not about trying to be “cool” or solving some “cool” problem. It’s about being a problem solver and finding simple, elegant solutions. (or complicated, if necessary)

- Next-Gen Data Scientists don’t try to impress with complicated algorithms and models that don’t work.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists spend a lot more time trying to get data into shape then anyone cares to admit.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists have the experience or education to actually know what they’re talking about. They’ve put their time in.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists are skeptical – skeptical about models themselves and how they can fail and the way they’re used or can be misused.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists make sure they know what they’re talking about before running around trying to show everyone else they exist.

- Next-Gen Data Scientsts have a variety of skills including coding, statistics, machine learning, visualization, communication, math.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists do enough Science to merit the word “Scientist”, someone who tests hypotheses and welcomes challenges and alternative theories.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists are solving a new breed of problem that surrounds the structure and exploration of data and the computational issues surrounding it.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists don’t find religion in tools, methods or academic departments. They are versatile and interdisciplinary.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists are highly skilled and ought to get paid well enough that they don’t have to worry too much about money

- Next-Gen Data Scientists don’t let money blind them to the point that their models are used for unethical purposes.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists seek out opportunities to solve problems of social value.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists understand the implications and consequences of the models they’re building.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists collaborate and cooperate.

- Next-Gen Data Scientists bring their humanity with them to problem solving, and algorithm/model-building.

What is a model?

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about mathematical models and how to explain them to people who aren’t mathematicians or statisticians. I consider this increasingly important as more and more models are controlling our lives, such as:

- employment models, which help large employers screen through applications,

- political ad models, which allow political groups to personalize their ads,

- credit scoring models, which allow consumer product companies and loan companies to screen applicants, and,

- if you’re a teacher, the Value-Added Model.

- See more models here and here.

It’s a big job, to explain these, because the truth is they are complicated – sometimes overly so, sometimes by construction.

The truth is, though, you don’t really need to be a mathematician to know what a model is, because everyone uses internal models all the time to make decisions.

For example, you intuitively model everyone’s appetite when you cook a meal for your family. You know that one person loves chicken (but hates hamburgers), while someone else will only eat the pasta (with extra cheese). You even take into account that people’s appetites vary from day to day, so you can’t be totally precise in preparing something – there’s a standard error involved.

To explain modeling at this level, then, you just need to imagine that you’ve built a machine that knows all the facts that you do and knows how to assemble them together to make a meal that will approximately feed your family. If you think about it, you’ll realize that you know a shit ton of information about the likes and dislikes of all of your family members, because you have so many memories of them grabbing seconds of the asparagus or avoiding the string beans.

In other words, it would be actually incredibly hard to give a machine enough information about all the food preferences for all your family members, and yourself, along with the constraints of having not too much junky food, but making sure everyone had something they liked, etc. etc.

So what would you do instead? You’d probably give the machine broad categories of likes and dislikes: this one likes meat, this one likes bread and pasta, this one always drinks lots of milk and puts nutella on everything in sight. You’d dumb it down for the sake of time, in other words. The end product, the meal, may not be perfect but it’s better than no guidance at all.

That’s getting closer to what real-world modeling for people is like. And the conclusion is right too- you aren’t expecting your model to do a perfect job, because you only have a broad outline of the true underlying facts of the situation.

Plus, when you’re modeling people, you have to a priori choose the questions to ask, which will probably come in the form of “does he/she like meat?” instead of “does he/she put nutella on everything in sight?”; in other words, the important but idiosyncratic rules won’t even be seen by a generic one-size-fits-everything model.

Finally, those generic models are hugely scaled- sometimes there’s really only one out there, being used everywhere, and its flaws are compounded that many times over because of its reach.

So, say you’ve got a CV with a spelling error. You’re trying to get a job, but the software that screens for applicants automatically rejects you because of this spelling error. Moreover, the same screening model is used everywhere, and you therefore don’t get any interviews because of this one spelling error, in spite of the fact that you’re otherwise qualified.

I’m not saying this would happen – I don’t know how those models actually work, although I do expect points against you for spelling errors. My point is there’s some real danger in using such models on a very large scale that we know are simplified versions of reality.

One last thing. The model fails in the example above, because the qualified person doesn’t get a job. But it fails invisibly; nobody knows exactly how it failed or even that it failed. Moreover, it only really fails for the applicant who doesn’t get any interviews. For the employer, as long as some qualified applicants survive the model, they don’t see failure at all.

Columbia Data Science course, week 4: K-means, Classifiers, Logistic Regression, Evaluation

This week our guest lecturer for the Columbia Data Science class was Brian Dalessandro. Brian works at Media6Degrees as a VP of Data Science, and he’s super active in the research community. He’s also served as co-chair of the KDD competition.

Before Brian started, Rachel threw us a couple of delicious data science tidbits.

The Process of Data Science

First we have the Real World. Inside the Real World we have:

- Users using Google+

- People competing in the Olympics

- Spammers sending email

From this we draw raw data, e.g. logs, all the olympics records, or Enron employee emails. We want to process this to make it clean for analysis. We use pipelines of data munging, joining, scraping, wrangling or whatever you want to call it and we use tools such as:

- python

- shell scripts

- R

- SQL

We eventually get the data down to a nice format, say something with columns:

name event year gender event time

Note: this is where you typically start in a standard statistics class. But it’s not where we typically start in the real world.

Once you have this clean data set, you should be doing some kind of exploratory data analysis (EDA); if you don’t really know what I’m talking about then look at Rachel’s recent blog post on the subject. You may realize that it isn’t actually clean.

Next, you decide to apply some algorithm you learned somewhere:

- k-nearest neighbor

- regression

- Naive Bayes

- (something else),

depending on the type of problem you’re trying to solve:

- classification

- prediction

- description

You then:

- interpret

- visualize

- report

- communicate

At the end you have a “data product”, e.g. a spam classifier.

K-means

So far we’ve only seen supervised learning. K-means is the first unsupervised learning technique we’ll look into. Say you have data at the user level:

- G+ data

- survey data

- medical data

- SAT scores

Assume each row of your data set corresponds to a person, say each row corresponds to information about the user as follows:

age gender income Geo=state household size

Your goal is to segment them, otherwise known as stratify, or group, or cluster. Why? For example:

- you might want to give different users different experiences. Marketing often does this.

- you might have a model that works better for specific groups

- hierarchical modeling in statistics does something like this.

One possibility is to choose the groups yourself. Bucket users using homemade thresholds. Like by age, 20-24, 25-30, etc. or by income. In fact, say you did this, by age, gender, state, income, marital status. You may have 10 age buckets, 2 gender buckets, and so on, which would result in 10x2x50x10x3 = 30,000 possible bins, which is big.

You can picture a five dimensional space with buckets along each axis, and each user would then live in one of those 30,000 five-dimensional cells. You wouldn’t want 30,000 marketing campaigns so you’d have to bin the bins somewhat.

Wait, what if you want to use an algorithm instead where you could decide on the number of bins? K-means is a “clustering algorithm”, and k is the number of groups. You pick k, a hyper parameter.

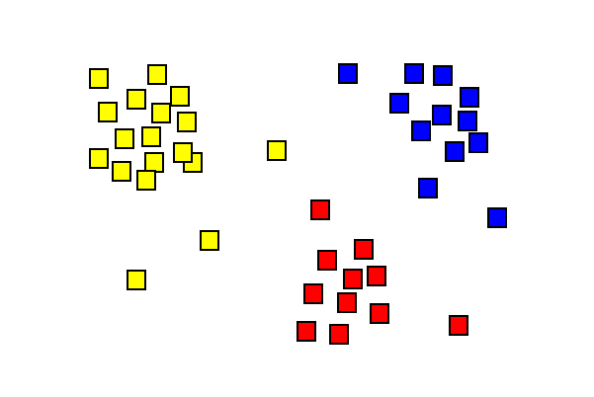

2-d version

Say you have users with #clicks, #impressions (or age and income – anything with just two numerical parameters). Then k-means looks for clusters on the 2-d plane. Here’s a stolen and simplistic picture that illustrates what this might look like:

The general algorithm is just the same picture but generalized to d dimensions, where d is the number of features for each data point.

Here’s the actual algorithm:

- randomly pick K centroids

- assign data to closest centroid.

- move the centroids to the average location of the users assigned to it

- repeat until the assignments don’t change

It’s up to you to interpret if there’s a natural way to describe these groups.

This is unsupervised learning and it has issues:

- choosing an optimal k is also a problem although

, where n is number of data points.

- convergence issues – the solution can fail to exist (the configurations can fall into a loop) or “wrong”

- but it’s also fast

- interpretability can be a problem – sometimes the answer isn’t useful

- in spite of this, there are broad applications in marketing, computer vision (partition an image), or as a starting point for other models.

One common tool we use a lot in our systems is logistic regression.

Thought Experiment

Brian now asked us the following:

How would data science differ if we had a “grand unified theory of everything”?

He gave us some thoughts:

- Would we even need data science?

- Theory offers us a symbolic explanation of how the world works.

- What’s the difference between physics and data science?

- Is it just accuracy? After all, Newton wasn’t completely precise, but was pretty close.

If you think of the sciences as a continuum, where physics is all the way on the right, and as you go left, you get more chaotic, then where is economics on this spectrum? Marketing? Finance? As we go left, we’re adding randomness (and as a clever student points out, salary as well).

Bottomline: if we could model this data science stuff like we know how to model physics, we’d know when people will click on what ad. The real world isn’t this understood, nor do we expect to be able to in the future.

Does “data science” deserve the word “science” in its name? Here’s why maybe the answer is yes.

We always have more than one model, and our models are always changing.

The art in data science is this: translating the problem into the language of data science

The science in data science is this: given raw data, constraints and a problem statement, you have an infinite set of models to choose from, with which you will use to maximize performance on some evaluation metric, that you will have to specify. Every design choice you make can be formulated as an hypothesis, upon which you will use rigorous testing and experimentation to either validate or refute.

Never underestimate the power of creativity: usually people have vision but no method. As the data scientist, you have to turn it into a model within the operational constraints. You need to optimize a metric that you get to define. Moreover, you do this with a scientific method, in the following sense.

Namely, you hold onto your existing best performer, and once you have a new idea to prototype, then you set up an experiment wherein the two best models compete. You therefore have a continuous scientific experiment, and in that sense you can justify it as a science.

Classifiers

Given

- data

- a problem, and

- constraints,

we need to determine:

- a classifier,

- an optimization method,

- a loss function,

- features, and

- an evaluation metric.

Today we will focus on the process of choosing a classifier.

Classification involves mapping your data points into a finite set of labels or the probability of a given label or labels. Examples of when you’d want to use classification:

- will someone click on this ad?

- what number is this?

- what is this news article about?

- is this spam?

- is this pill good for headaches?

From now on we’ll talk about binary classification only (0 or 1).

Examples of classification algorithms:

- decision tree

- random forests

- naive bayes

- k-nearest neighbors

- logistic regression

- support vector machines

- neural networks

Which one should we use?

One possibility is to try them all, and choose the best performer. This is fine if you have no constraints or if you ignore constraints. But usually constraints are a big deal – you might have tons of data or not much time or both.

If I need to update 500 models a day, I do need to care about runtime. these end up being bidding decisions. Some algorithms are slow – k-nearest neighbors for example. Linear models, by contrast, are very fast.

One under-appreciated constraint of a data scientist is this: your own understanding of the algorithm.

Ask yourself carefully, do you understand it for real? Really? Admit it if you don’t. You don’t have to be a master of every algorithm to be a good data scientist. The truth is, getting the “best-fit” of an algorithm often requires intimate knowledge of said algorithm. Sometimes you need to tweak an algorithm to make it fit your data. A common mistake for people not completely familiar with an algorithm is to overfit.

Another common constraint: interpretability. You often need to be able to interpret your model, for the sake of the business for example. Decision trees are very easy to interpret. Random forests, on the other hand, not so much, even though it’s almost the same thing, but can take exponentially longer to explain in full. If you don’t have 15 years to spend understanding a result, you may be willing to give up some accuracy in order to have it easy to understand.

Note that credit cards have to be able to explain their models by law so decision trees make more sense than random forests.

How about scalability? In general, there are three things you have to keep in mind when considering scalability:

- learning time: how much time does it take to train the model?

- scoring time: how much time does it take to give a new user a score once the model is in production?

- model storage: how much memory does the production model use up?

Here’s a useful paper to look at when comparing models: “An Empirical Comparison of Supervised Learning Algorithms”, from which we learn:

- Simpler models are more interpretable but aren’t as good performers.

- The question of which algorithm works best is problem dependent

- It’s also constraint dependent

At M6D, we need to match clients (advertising companies) to individual users. We have logged the sites they have visited on the internet. Different sites collect this information for us. We don’t look at the contents of the page – we take the url and hash it into some random string and then we have, say, the following data about a user we call “u”:

u = <xyz, 123, sdqwe, 13ms>

This means u visited 4 sites and their urls hashed to the above strings. Recall last week we learned spam classifier where the features are words. We aren’t looking at the meaning of the words. So the might as well be strings.

At the end of the day we build a giant matrix whose columns correspond to sites and whose rows correspond to users, and there’s a “1” if that user went to that site.

To make this a classifier, we also need to associate the behavior “clicked on a shoe ad”. So, a label.

Once we’ve labeled as above, this looks just like spam classification. We can now rely on well-established methods developed for spam classification – reduction to a previously solved problem.

Logistic Regression

We have three core problems as data scientists at M6D:

- feature engineering,

- user level conversion prediction,

- bidding.

We will focus on the second. We use logistic regression– it’s highly scalable and works great for binary outcomes.

What if you wanted to do something else? You could simply find a threshold so that, above you get 1, below you get 0. Or you could use a linear model like linear regression, but then you’d need to cut off below 0 or above 1.

What’s better: fit a function that is bounded in side [0,1]. For example, the logit function

wanna estimate

.

To make this a linear model in the outcomes , we take the log of the odds ratio:

The parameter keeps shape of the logit curve but shifts it back and forth. To interpret

further, consider what we call the base rate, the unconditional probability of “1” (so, in the case of ads, the base rate would correspond to the click-through rate, i.e. the overall tendency for people to click on ads; this is typically on the order of 1%).

If you had no information except the base rate, the average prediction would be just that. In a logistical regression, defines the base rate. Specifically, the base rate is approximately equal to

The slope defines the slope of the logit function. Note in general it’s a vector which is as long as the number of features we are using for each data point.

Our immediate modeling goal is to use our training data to find the best choices for and

We will use a maximum likelihood estimation or convex optimization to achieve this; we can’t just use derivatives and vector calculus like we did with linear regression because it’s a complicated function of our data.

The likelihood function is defined by:

where we are assuming the data points are independent and where

We then search for the parameters that maximize this having observed our data:

The probability of a single observation is

where is the modeled probability of a “1” for the binary outcome $Y_i.$ Taking the product of all of these we get our likelihood function which we want to maximize.

Similar to last week, we now take the log and get something convex, so it has to have a global maximum. Finally, we use numerical techniques to find it, which essentially follow the gradient like Newton’s method from calculus. Computer programs can do this pretty well. These algorithms depend on a step size, which we will need to adjust as we get closer to the global max or min – there’s an art to this piece of numerical optimization as well. Each step of the algorithm looks something like this:

where remember we are actually optimizing our parameters and

to maximize the (log) likelihood function, so the

you see above is really a vector of

s and the function

corresponds to our

“Flavors” of Logistic Regression for convex optimization.

The Newton’s method we described above is also called Iterative Reweighted Least Squares. It uses the curvature of log-likelihood to choose appropriate step direction. The actual calculation involves the Hessian matrix, and in particular requires its inversion, which is a kxk matrix. This is bad when there’s lots of features, as in 10,000 or something. Typically we don’t have that many features but it’s not impossible.

Another possible method to maximize our likelihood or log likelihood is called Stochastic Gradient Descent. It approximates gradient using a single observation at a time. The algorithm updates the current best-fit parameters each time it sees a new data point. The good news is that there’s no big matrix inversion, and it works well with huge data and with sparse features; it’s a big deal in Mahout and Vowpal Wabbit. The bad news is it’s not such a great optimizer and it’s very dependent on step size.

Evaluation

We generally use different evaluation metrics for different kind of models.

First, for ranking models, where we just want to know a relative rank versus and absolute score, we’d look to one of:

Second, for classification models, we’d look at the following metrics:

- lift: how much more people are buying or clicking because of a model

- accuracy: how often the correct outcome is being predicted

- f-score

- precision

- recall

Finally, for density estimation, where we need to know an actual probability rather than a relative score, we’d look to:

In general it’s hard to compare lift curves but you can compare AUC (area under the receiver operator curve) – they are “base rate invariant.” In other words if you bring the click-through rate from 1% to 2%, that’s 100% lift but if you bring it from 4% to 7% that’s less lift but more effect. AUC does a better job in such a situation when you want to compare.

Density estimation tests tell you how well are you fitting for conditional probability. In advertising, this may arise if you have a situation where each ad impression costs $c and for each conversion you receive $q. You will want to target every conversion that has a positive expected value, i.e. whenever

But to do this you need to make sure the probability estimate on the left is accurate, which in this case means something like the mean squared error of the estimator is small. Note a model can give you good rankings but bad P estimates.

Similarly, features that rank highly on AUC don’t necessarily rank well with respect to mean absolute error. So feature selection, as well as your evaluation method, is completely context-driven.

Evaluating professor evaluations

I recently read this New York Times “Room for Debate” on professor evaluations. There were some reasonably good points made, with people talking about the trend that students generally give better grades to attractive professors and easy grading professors, and that they were generally more interested in the short-term than in the long-term in this sense.

For these reasons, it was stipulated, it would be better and more informative to have anonymous evaluations, or have students come back after some time to give evaluations, or interesting ideas like that.

Then there was a crazy crazy man named Jeff Sandefer, co-founder and master teacher at the Acton School of Business in Austin, Texas. He likes to call his students “customers” and here’s how he deals with evaluations:

Acton, the business school that I co-founded, is designed and is led exclusively by successful chief executives. We focus intently on customer feedback. Every week our students rank each course and professor, and the results are made public for all to see. We separate the emotional venting from constructive criticism in the evaluations, and make frequent changes in the program in real time.

We also tie teacher bonuses to the student evaluations and each professor signs an individual learning covenant with each student. We have eliminated grade inflation by using a forced curve for student grades, and students receive their grades before evaluating professors. Not only do we not offer tenure, but our lowest rated teachers are not invited to return.

First of all, I’m not crazy about the idea of weekly rankings and public shaming going on here. And how do you separate emotional venting from constructive criticism anyway? Isn’t the customer always right? Overall the experience of the teachers doesn’t sound good – if I have a choice as a teacher, I teach elsewhere, unless the pay and the students are stellar.

On the other hand, I think it’s interesting that they have a curve for student grades. This does prevent the extra good evaluations coming straight from grade inflation (I’ve seen it, it does happen).

Here’s one think I didn’t see discussed, which is students themselves and how much they want to be in the class. When I taught first semester calculus at Barnard twice in consecutive semesters, my experience was vastly different in the two classes.

The first time I taught, in the Fall, my students were mostly straight out of high school, bright eyed and bushy tailed, and were happy to be there, and I still keep in touch with some of them. It was a great class, and we all loved each other by the end of it. I got crazy good reviews.

By contrast, the second time I taught the class, which was the next semester, my students were annoyed, bored, and whiny. I had too many students in the class, partly because my reviews were so good. So the class was different on that score, but I don’t think that mattered so much to my teaching.

My theory, which was backed up by all the experienced Profs in the math department, was that I had the students who were avoiding calculus for some reason. And when I thought about it, they weren’t straight out of high school, they were all over the map. They generally were there only because they needed some kind of calculus to fulfill a requirement for their major.

Unsurprisingly, I got mediocre reviews, with some really pretty nasty ones. The nastiest ones, I noticed, all had some giveaway that they had a bad attitude- something like, “Cathy never explains anything clearly, and I hate calculus.” My conclusion is that I get great evaluations from students who want to learn calculus and nasty evaluations from students who resent me asking them to really learn calculus.

What should we do about prof evaluations?

The problem with using evaluations to measure professor effectiveness is that you might be a prof that only has ever taught calculus in the Spring, and then you’d be wrongfully punished. That’s where we are now, and people know it, so instead of using them they just mostly ignore them. Of course, the problem with not ever using these evaluations is that they might actually contain good information that you could use to get better at teaching.

We have a lot of data collected on teacher evaluations, so I figure we should be analyzing it to see if there really is a useful signal or not. And we should use domain expertise from experienced professors to see if there are any other effects besides the “Fall/Spring attitude towards math” effect to keep in mind.

It’s obviously idiosyncratic depending on field and even which class it is, i.e. Calc II versus Calc III. If there even is a signal after you extract the various effects and the “attractiveness” effect, I expect it to be very noisy and so I’d hate to see someone’s entire career depend on evaluations, unless there was something really outrageous going on.

In any case it would be fun to do that analysis.

Filter Bubble

[I’m planning on a couple of trips in the next few days and I might not be blogging regularly, depending on various things like wifi access. Not to worry!]

I just finished reading “Filter Bubble,” by Eli Pariser, which I enjoyed quite a bit. The premise that the multitude of personalization algorithms are limiting our online experience to the point that, although we don’t see it happening, we are becoming coddled, comfortable, insular, and rigid-minded. In other words, the opposite of what we all thought would happen when the internet began, and we had a virtual online international bazaar of different people, perspectives, and paradigms.

He focuses on the historical ethics (and lack thereof) of the paper press, and talks about how at the very least, as people skipped the complicated boring stories of Afghanistan to read the sports section, at least they knew the story they were skipping existed and was important; he compares this to now, where a “personalized everything online world” allows people to only ever read what they want to read (i.e. sports, or fashion, or tech gadget news) and never even know there’s a war going on out there.

Pariser does a good job explaining the culture of the modeling and technology set, and how they claim to have no moral purpose to their algorithms when it suits them. He goes deeply into the inconsistent data policy of Facebook and the search algorithm of Google, plumbing them for moral consequences if not intent.

Some of the Pariser’s conclusions are reasonable and some of them aren’t. He begs for more transparency, and uses Linux up as an example of that – so far so good. But when he claims that Google wouldn’t lose market share by open sourcing up their search algorithm, that’s just plain silly. He likes Twitter’s data policy, mostly because it’s easy to understand and well-explained, but he hates Facebook’s because it isn’t; but those two companies are accomplishing very different things, so it’s not a good comparison (although I agree with him re: Facebook).

In the end, cracking the private company data policies won’t happen by asking them to be more transparent, and Pariser realizes that: he proposes to appeal to individuals and to government policy to help protect individuals’ data. Of course the government won’t do anything until enough people demand it, and Pariser realizes the first step to get people to care about the issue is to educate them on what is actually going on, and how creepy it is. This book is a good start.

Columbia Data Science course, week 3: Naive Bayes, Laplace Smoothing, and scraping data off the web

In the third week of the Columbia Data Science course, our guest lecturer was Jake Hofman. Jake is at Microsoft Research after recently leaving Yahoo! Research. He got a Ph.D. in physics at Columbia and taught a fantastic course on modeling last semester at Columbia.

After introducing himself, Jake drew up his “data science profile;” turns out he is an expert on a category that he created called “data wrangling.” He confesses that he doesn’t know if he spends so much time on it because he’s good at it or because he’s bad at it.

Thought Experiment: Learning by Example

Jake had us look at a bunch of text. What is it? After some time we describe each row as the subject and first line of an email in Jake’s inbox. We notice the bottom half of the rows of text looks like spam.

Now Jake asks us, how did you figure this out? Can you write code to automate the spam filter that your brain is?

Some ideas the students came up with:

- Any email is spam if it contains Viagra references. Jake: this will work if they don’t modify the word.

- Maybe something about the length of the subject?

- Exclamation points may point to spam. Jake: can’t just do that since “Yahoo!” would count.

- Jake: keep in mind spammers are smart. As soon as you make a move, they game your model. It would be great if we could get them to solve important problems.

- Should we use a probabilistic model? Jake: yes, that’s where we’re going.

- Should we use k-nearest neighbors? Should we use regression? Recall we learned about these techniques last week. Jake: neither. We’ll use Naive Bayes, which is somehow between the two.

Why is linear regression not going to work?

Say you make a feature for each lower case word that you see in any email and then we used R’s “lm function:”

lm(spam ~ word1 + word2 + …)

Wait, that’s too many variables compared to observations! We have on the order of 10,000 emails with on the order of 100,000 words. This will definitely overfit. Technically, this corresponds to the fact that the matrix in the equation for linear regression is not invertible. Moreover, maybe can’t even store it because it’s so huge.

Maybe you could limit to top 10,000 words? Even so, that’s too many variables vs. observations to feel good about it.

Another thing to consider is that target is 0 or 1 (0 if not spam, 1 if spam), whereas you wouldn’t get a 0 or a 1 in actuality through using linear regression, you’d get a number. Of course you could choose a critical value so that above that we call it “1” and below we call it “0”. Next week we’ll do even better when we explore logistic regression, which is set up to model a binary response like this.

How about k-nearest neighbors?

To use k-nearest neighbors we would still need to choose features, probably corresponding to words, and you’d likely define the value of those features to be 0 or 1 depending on whether the word is present or not. This leads to a weird notion of “nearness”.

Again, with 10,000 emails and 100,000 words, we’ll encounter a problem: it’s not a singular matrix this time but rather that the space we’d be working in has too many dimensions. This means that, for example, it requires lots of computational work to even compute distances, but even that’s not the real problem.

The real problem is even more basic: even your nearest neighbors are really far away. this is called “the curse of dimensionality“. This problem makes for a poor algorithm.

Question: what if sharing a bunch of words doesn’t mean sentences are near each other in the sense of language? I can imagine two sentences with the same words but very different meanings.

Jake: it’s not as bad as it sounds like it might be – I’ll give you references at the end that partly explain why.

Aside: digit recognition

In this case k-nearest neighbors works well and moreover you can write it in a few lines of R.

Take your underlying representation apart pixel by pixel, say in a 16 x 16 grid of pixels, and measure how bright each pixel is. Unwrap the 16×16 grid and put it into a 256-dimensional space, which has a natural archimedean metric. Now apply the k-nearest neighbors algorithm.

Some notes:

- If you vary the number of neighbors, it changes the shape of the boundary and you can tune k to prevent overfitting.

- You can get 97% accuracy with a sufficiently large data set.

- Result can be viewed in a “confusion matrix“.

Naive Bayes

Question: You’re testing for a rare disease, with 1% of the population is infected. You have a highly sensitive and specific test:

- 99% of sick patients test positive

- 99% of healthy patients test negative

Given that a patient tests positive, what is the probability that the patient is actually sick?

Answer: Imagine you have 100×100 = 10,000 people. 100 are sick, 9,900 are healthy. 99 sick people test sick, and 99 healthy people do too. So if you test positive, you’re equally likely to be healthy or sick. So the answer is 50%.

Let’s do it again using fancy notation so we’ll feel smart:

Recall

and solve for

The denominator can be thought of as a “normalization constant;” we will often be able to avoid explicitly calculuating this. When we apply the above to our situation, we get:

This is called “Bayes’ Rule“. How do we use Bayes’ Rule to create a good spam filter? Think about it this way: if the word “Viagra” appears, this adds to the probability that the email is spam.

To see how this will work we will first focus on just one word at a time, which we generically call “word”. Then we have:

The right-hand side of the above is computable using enough pre-labeled data. If we refer to non-spam as “ham”, we only need and

This is essentially a counting exercise.

Example: go online and download Enron emails. Awesome. We are building a spam filter on that – really this means we’re building a new spam filter on top of the spam filter that existed for the employees of Enron.

Jake has a quick and dirty shell script in bash which runs this. It downloads and unzips file, creates a folder. Each text file is an email. They put spam and ham in separate folders.

Jake uses “wc” to count the number of messages for one former Enron employee, for example. He sees 1500 spam, and 3672 ham. Using grep, he counts the number of instances of “meeting”:

grep -il meeting enron1/spam/*.txt | wc -l

This gives 153. This is one of the handful of computations we need to compute

Note we don’t need a fancy programming environment to get this done.

Next, we try:

- “money”: 80% chance of being spam.

- “viagra”: 100% chance.

- “enron”: 0% chance.

This illustrates overfitting; we are getting overconfident because of our biased data. It’s possible, in other words, to write an non-spam email with the word “viagra” as well as a spam email with the word “enron.”

Next, do it for all the words. Each document can be represented by a binary vector, whose jth entry is 1 or 0 depending whether jth word appears. Note this is a huge-ass vector, we will probably actually represent it with the indices of the words that actually do show up.

Here’s the model we use to estimate the probability that we’d see a given word vector given that we know it’s spam (or that it’s ham). We denote the document vector and the various entries

, where the

correspond to all the indices of

in other words over all the words. For now we denote “is spam” by

:

The theta here is the probability that an individual word is present in a spam email (we can assume separately and parallel-ly compute that for every word). Note we are modeling the words independently and we don’t count how many times they are present. That’s why this is called “Naive”.

Let’s take the log of both sides:

[It’s good to take the log because multiplying together tiny numbers can give us numerical problems.]

The term doesn’t depend on a given document, just the word, so let’s rename it

Same with

. The real weights that vary by document are the

‘s.

We can now use Bayes’ Rule to get an estimate of which is what we actually want. We can also get away with not computing all the terms if we only care whether it’s more likely to be spam or to be ham. Only the varying term needs to be computed.

Wait, this ends up looking like a linear regression! But instead of computing them by inverting a huge matrix, the weights come from the Naive Bayes’ algorithm.

This algorithm works pretty well and it’s “cheap to train” if you have pre-labeled data set to train on. Given a ton of emails, just count the words in spam and non-spam emails. If you get more training data you can easily increment your counts. In practice there’s a global model, which you personalize to individuals. Moreover, there are lots of hard-coded, cheap rules before an email gets put into a fancy and slow model.

Here are some references:

- “Idiot’s Bayes – not so stupid after all?” – the whole paper is about why it doesn’t suck, which is related to redundancies in language.

- “Naive Bayes at Forty: The Independence Assumption in Information“

- “Spam Filtering with Naive Bayes – Which Naive Bayes?“

Laplace Smoothing

Laplace Smoothing refers to the idea of replacing our straight-up estimate of the probability of seeing a given word in a spam email with something a bit fancier:

We might fix and

for example, to prevents the possibility of getting 0 or 1 for a probability. Does this seem totally ad hoc? Well if we want to get fancy, we can see this as equivalent to having a prior and performing a maximal likelihood estimate.

If we denote by the maximal likelihood estimate, then we have:

In other words, we are asking the question, for what value of were the data D most probable? If we assume independent trials then we want to maximize

If you take the derivative, and set it to zero, we get

In other words, just what we had before. Now let’s add a prior. Denote by the maximum a posteriori likelihood:

This similarly asks the question, given the data I saw, which parameter is the most likely?

Use Bayes’ rule to get . This looks similar to above except for the

, which is the “prior”. If I assume

is of the form

; then we get the above, Laplacian smoothed version.

Sometimes and

are called “pseudo counts”. They’re fancy but also simple. It’s up to the data scientist to set the values of these hyperparameters, and it gives us two knobs to tune. By contrast, k-nearest neighbors has one knob, namely k.

Note: In the last 5 years people have started using stochastic gradient methods to avoid the non-invertible (overfitting) matrix problem. Switching to logistic regression with stochastic gradient method helped a lot, and can account for correlations between words. Even so, Naive Bayes’ is pretty impressively good considering how simple it is.

Scraping the web: API’s

For the sake of this discussion, an API (application programming interface) is something websites provide to developers so they can download data from the website easily and in standard format. Usually the developer has to register and receive a “key”, which is something like a password. For example, the New York Times has an API here. Note that some websites limit what data you have access to through their API’s or how often you can ask for data without paying for it.

When you go this route, you often get back weird formats, sometimes in JSON, but there’s no standardization to this standardization, i.e. different websites give you different “standard” formats.

One way to get beyond this is to use Yahoo’s YQL language which allows you to go to the Yahoo! Developer Network and write SQL-like queries that interact with many of the common API’s on the common sites like this:

select * from flickr.photos.search where text=”Cat” and api_key=”lksdjflskjdfsldkfj” limit 10

The output is standard and I only have to parse this in python once.

What if you want data when there’s no API available?

Note: always check the terms and services of the website before scraping.

In this case you might want to use something like the Firebug extension for Firefox, you can “inspect the element” on any webpage, and Firebug allows you to grab the field inside the html. In fact it gives you access to the full html document so you can interact and edit. In this way you can see the html as a map of the page and Firebug is a kind of tourguide.

After locating the stuff you want inside the html, you can use curl, wget, grep, awk, perl, etc., to write a quick and dirty shell script to grab what you want, especially for a one-off grab. If you want to be more systematic you can also do this using python or R.

Other parsing tools you might want to look into:

- lynx and lynx –dump: good if you pine for the 1970’s. Oh wait, 1992. Whatever.

- Beautiful Soup: robust but kind of slow

- Mechanize (or here) super cool as well but doesn’t parse javascript.

Postscript: Image Classification

How do you determine if an image is a landscape or a headshot?

You either need to get someone to label these things, which is a lot of work, or you can grab lots of pictures from flickr and ask for photos that have already been tagged.

Represent each image with a binned RGB – (red green blue) intensity histogram. In other words, for each pixel, for each of red, green, and blue, which are the basic colors in pixels, you measure the intensity, which is a number between 0 and 255.

Then draw three histograms, one for each basic color, showing us how many pixels had which intensity. It’s better to do a binned histogram, so have counts of # pixels of intensity 0 – 51, etc. – in the end, for each picture, you have 15 numbers, corresponding to 3 colors and 5 bins per color. We are assuming every picture has the same number of pixels here.

Finally, use k-nearest neighbors to decide how much “blue” makes a landscape versus a headshot. We can tune the hyperparameters, which in this case are # of bins as well as k.

Am I the sexiest thing about the 21st century?

Hey, I didn’t say it – mathbabe is much too modest!

It was the Harvard Business Review’s Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century.

I kind of like it how they refer to us data scientists as wanting to “be on the bridge” with Captain Kirk: true. And they refer to the “care and feeding” of data scientists like we are so many bison. Turns out we need to be free-range bison. Mooo (do bison moo?).

I’m blogging about the third week of the Data Science course at Columbia later this morning, but I couldn’t resist this title.

Two rants about hiring a data scientist

I had a great time yesterday handing out #OWS Alternative Banking playing cards to press, police, and protesters all over downtown Manhattan, and I’m planning to write a follow-up post soon about whether Occupy is or is not dead and whether we do or do not wish it to be and for what reason (spoiler alert: I wish it were because I wish all the problems Occupy seeks to address had been solved).

But today I’m taking a break to do some good and quick, old-fashioned venting.

——-

First rant: I hate it when I hear business owners say they want to hire data scientists but only if they know SQL, because for whatever reason they aren’t serious if they don’t learn something as important as that.

That’s hogwash!

If I’m working at a company that has a Hive, why would I bother learning SQL? Especially if I’ve presumably got some quantitative chops and can learn something like SQL in a matter of days. It would be a waste of my time to do it in advance of actually using it.

I think people get on this pedestal because:

- It’s hard for them to learn SQL so they assume it’s hard for other smart people. False.

- They have only worked in environments where a SQL database was the main way to get data. No longer true.

By the way, you can replace “SQL” above with any programming language, although SQL seems to be the most common one where people hold it against you with some kind of high and mighty attitude.

——-

Second rant: I hate it when I hear data scientists dismiss domain expertise as unimportant. They act like they’re such good data miners that they’ll find out anything the domain experts knew and then some within hours, i.e. in less time than it would take to talk to a domain expertise carefully about their knowledge.

That’s dumb!

If you’re not listening well, then you’re missing out on the best signals of all. Get over your misanthropic, aspy self and do a careful interview. Pay attention to what happens over time and why and how long effects take and signals that they have begun or ended. You will then have a menu of signals to check and you can start with them and move on to variations of them as appropriate.

If you ignore domain expertise, you are just going to overfit weird noisy signals to your model in addition to finding a few real ones and ignoring others that are very important but unintuitive (to you).

——-

I wanted to balance my rants so I don’t appear anti-business or anti-data scientist. What they have in common is understanding the world a little bit from the other person’s point of view, taking that other view seriously, and giving respect where it’s due.

Emanuel Derman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua

Why, if I’m so aware of the powers and dangers of modeling, do I still earn my living doing mathematical modeling? How am I to explain myself?

It’s not an easy question, and I’m happy to see that my friend Emanuel Derman has addressed this a couple of weeks ago in an essay published by the Journal of Derivatives, of all places (h/t Chris Wiggins). Its title is Apologia Pro Vita Sua, which means “in defense of one’s life.” Please read it – as usual, Derman has a beautiful way with words.

Before going into the details of his reasoning, I’d like to say that any honest attempt at trying to answer this question by someone intrigues and attracts me to them – what is more threatening and interesting that examining your life for its flaws? Never mind publishing it for all to see and to critique.

Emanuel starts his essay by listing off the current flaws in finance better than any Occupier I’ve ever met:

After giving some background about himself and setting up the above question of justifying oneself as a modeler, Derman reveals himself to be a Blakean, by which he means that “part of our job on earth is to perceptively reveal the way the world really works”.

And how does the world work? According to Norman Mailer, anyway, it’s an enormous ego contest – we humans struggle to compete and to be seen as writers, scientists, and, evidently, financial engineers.

It’s not completely spelled out but I understand his drift to be that the corruption and crony capitalism we are seeing around us in the financial system is understandable from that perspective – possibly even obvious. As an individual player inside this system, I naturally compete in various ways with the people around me, to try to win, however I define that word.

On the one hand you can think of the above argument as weak, along the lines of “because everybody else is doing it.” On the other hand, you could also frame it as understanding the inevitable consequences of having a system which allows for corruption, which has built-in bad incentives.

From this perspective you can’t simply ask people not to be assholes or not to use lobbyists to get laws passed for their benefit. You need to actually change the incentive system itself.

Derman’s second line of defense is that the current system isn’t ideal but he uses his experience to carefully explain the dangers of modeling to his students, thereby training a generation not to trust too deeply in the idea of financial engineering as a science:

Unfortunately, no matter what academics, economists, or banks tell you, there is no truly reliable financial science beneath financial engineering. By using variables such as volatility and liquidity that are crude but quantitative proxies for complex human behaviors, financial models attempt to describe the ripples on a vast and ill-understood sea of ephemeral human passions. Such models are roughly reliable only as long as the sea stays calm. When it does not, when crowds panic, anything can happen.

Finally, he quotes the Modelers’ Hippocratic Oath, which I have blogged about multiple times and I still love:

Although I agree that people are by nature tunnel visioned when it comes to success and that we need to set up good systems with appropriate incentives, I personally justify my career more along the lines of Derman’s second argument.

Namely, I want there to be someone present in the world of mathematical modeling that can represent the skeptic, that can be on-hand to remind people that it’s important to consider the repercussions of how we set up a given model and how we use its results, especially if it touches a massive number of people and has a large effect on their lives.

If everyone like me leaves, because they don’t want to get their hands dirty worrying about how the models are wielded, then all we’d have left are people who don’t think about these things or don’t care about these things.

Plus I’m a huge nerd and I like technical challenges and problem solving. That’s along the lines of “I do it because it’s fun and it pays the rent,” probably not philosophically convincing but in reality pretty important.

A few days ago I was interviewed by a Japanese newspaper about my work with Occupy. One of the questions they asked me is if I’d ever work in finance again. My answer was, I don’t know. It depends on what my job would be and how my work would be used.

After all, I don’t think finance should go away entirely, I just want it to be set up well so it works, it acts as a service for people in the world; I’d like to see finance add value rather than extract. I could imagine working in finance (although I can’t imagine anyone hiring me) if my job were to model value to people struggling to save for their retirement, for example.

This vision is very much in line with Derman’s Postscript where he describes what he wants to see:

Finance, or at least the core of it, is regarded as an essential service, like the police, the courts, and

the firemen, and is regulated and compensated appropriately. Corporations, whose purpose is relatively straightforward, should be more constrained than individuals, who are mysterious with possibility.

People should be treated as adults, free to take risks and bound to suffer the consequent benefits and disadvantages. As the late Anna Schwartz wrote in a 2008 interview about the Fed, “Everything works much better when wrong decisions are punished and good decisions make you rich.”

No one should have golden parachutes, but everyone should have tin ones.

Why are the Chicago public school teachers on strike?

The issues of pay and testing

My friend and fellow HCSSiM 2012 staff member P.J. Karafiol explains some important issues in a Chicago Sun Times column entitled “Hard facts behind union, board dispute.”

P.J. is a Chicago public school math teacher, he has two kids in the CPS system, and he’s a graduate from that system. So I think he is qualified to speak on the issues.

He first explains that CPS teachers are paid less than those in the suburbs. This means, among other things, that it’s hard to keep good teachers. Next, he explains that, although it is difficult to argue against merit pay, the value-added models that Rahm Emanuel wants to account for half of teachers evaluation, is deeply flawed.

He then points out that, even if you trust the models, the number of teachers the model purports to identify as bad is so high that taking action on that result by firing them all would cause a huge problem – there’s a certain natural rate of finding and hiring good replacement teachers in the best of times, and these are not the best of times.

He concludes with this:

Teachers in Chicago are paid well initially, but face rising financial incentives to move to the suburbs as they gain experience and proficiency. No currently-existing “value added” evaluation system yields consistent, fair, educationally sound results. And firing bad teachers won’t magically create better ones to take their jobs.

To make progress on these issues, we have to figure out a way to make teaching in the city economically viable over the long-term; to evaluate teachers in a way that is consistent and reasonable, and that makes good sense educationally; and to help struggling teachers improve their practice. Because at base, we all want the same thing: classes full of students eager to be learning from their excellent, passionate teachers.

Test anxiety

Ultimately this crappy model, and the power that it yields, creates a culture of text anxiety for teachers and principals as well as for students. As Eric Zorn (grandson of mathematician Max Zorn) writes in the Chicago Tribune (h/t P.J. Karafiol):

The question: But why are so many presumptively good teachers also afraid? Why has the role of testing in teacher evaluations been a major sticking point in the public schools strike in Chicago?

The short answer: Because student test scores provide unreliable and erratic measurements of teacher quality. Because studies show that from subject to subject and from year to year, the same teacher can look alternately like a golden apple and a rotting fig.

Zorn quotes extensively from Math for America President John Ewing’s article in Notices of the American Mathematical Society:

Analyses of (value-added model) results have led researchers to doubt whether the methodology can accurately identify more and less effective teachers. (Value-added model) estimates have proven to be unstable across statistical models, years and classes that teachers teach.

One study found that across five large urban districts, among teachers who were ranked in the top 20 percent of effectiveness in the first year, fewer than a third were in that top group the next year, and another third moved all the way down to the bottom 40 percent.

Another found that teachers’ effectiveness ratings in one year could only predict from 4 percent to 16 percent of the variation in such ratings in the following year.

The politics behind the test

I agree that the value-added model (VAM) is deeply flawed; I’ve blogged about it multiple times, for example here.

The way I see it, VAM is a prime example of the way that mathematics is used as a weapon against normal people – in this case, teachers, principals, and schools. If you don’t see my logic, ask yourself this:

Why would a overly-complex, unproved and very crappy model be so protected by politicians?

There’s really one reason, namely it serves a political function, not a mathematical one. And that political function is to maintain control over the union via a magical box that nobody completely understands (including the politicians, but it serves their purposes in spite of this) and therefore nobody can argue against.

This might seem ridiculous when you have examples like this one from the Washington Post (h/t Chris Wiggins), in which a devoted and beloved math teacher named Ashley received a ludicrously low VAM score.

I really like the article: it was written by Sean C. Feeney, Ashley’s principal at The Wheatley School in New York State and president of the Nassau County High School Principals’ Association. Feeney really tries to understand how the model works and how it uses data.

Feeney uncovers the crucial facts that, on the one hand nobody understands how VAM works at all, and that, on the other, the real reason it’s being used is for the political games being played behind the scenes (emphasis mine):

Officials at our State Education Department have certainly spent countless hours putting together guides explaining the scores. These documents describe what they call an objective teacher evaluation process that is based on student test scores, takes into account students’ prior performance, and arrives at a score that is able to measure teacher effectiveness. Along the way, the guides are careful to walk the reader through their explanations of Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs) and a teacher’s Mean Growth Percentile (MGP), impressing the reader with discussions and charts of confidence ranges and the need to be transparent about the data. It all seems so thoughtful and convincing! After all, how could such numbers fail to paint an accurate picture of a teacher’s effectiveness?

(One of the more audacious claims of this document is that the development of this evaluative model is the result of the collaborative efforts of the Regents Task Force on Teacher and Principal Effectiveness. Those of us who know people who served on this committee are well aware that the recommendations of the committee were either rejected or ignored by State Education officials.)