Archive

Duke deans drop the ball on scientific misconduct

Former Duke University cancer researcher Anil Potti was found guilty of research misconduct yesterday by the federal Office of Research Integrity (ORI), after a multi-year investigation. You can read the story in Science, for example. His punishment is that he won’t do research without government-sponsored supervision for the next five years. Not exactly stiff.

This article also covers the ORI decision, and describes some of the people who suffered from poor cancer treatment because of his lies. Here’s an excerpt:

Shoffner, who had Stage 3 breast cancer, said she still has side effects from the wrong chemotherapy given to her in the Duke trial. Her joints were damaged, she said, and she suffered blood clots that prevent her from having knee surgery now. Of the eight patients who sued, Shoffner said, she is one of two survivors.

What’s interesting to me this morning is that both articles above mention the same reason for the initial investigation in his work. Namely, that he had padded his resume, pretending to be a Rhodes Scholar when he wasn’t. That fact was reported by a website called Cancer Letter in 2010.

But here’s the thing, back in 2008 a 3rd-year medical student named Bradford Perez sent the deans at Duke (according to Cancer Letter) a letter explaining that Potti’s lab was fabricating results. And for those of you who can read nerd, please go ahead and read his letter, it is extremely convincing. An excerpt:

Fifty-nine cell line samples with mRNA expression data from NCI-60 with associated radiation sensitivity were split in half to designate sensitive and resistant phenotypes. Then in developing the model, only those samples which fit the model best in cross validation were included. Over half of the original samples were removed. It is very possible that using these methods two samples with very little if any difference in radiation sensitivity could be in separate phenotypic categories. This was an incredibly biased approach which does little more than give the appearance of a successful cross validation.

Instead of taking up the matter seriously, the deans pressured Perez to keep quiet. And nothing more happened for two more years.

The good news: Bradford Perez seems to have gotten a perfectly good job.

The bad news: the deans at Duke suck. Unfortunately I don’t know exactly which deans and what their job titles are, but still: why are they not under investigation? What would deans have to do – or not do – to get in trouble? Is there any kind of accountability here?

The market for your personal data is maturing

As everyone knows, nobody reads their user agreements when they sign up for apps or services. Even if they did, it wouldn’t matter, because most of them stipulate that they can change at any moment. That moment has come.

You might not be concerned, but I’d like to point out that there’s a reason you’re not. Namely, you haven’t actually seen what this enormous loss of privacy translates into yet.

You see, there’s also a built in lag where we’ve given up our data, and are happily using the corresponding services, but we haven’t yet seen evidence that our data was actually worth something. The lag represents the time it takes for the market in personal data to mature. It also represents the patience that Silicon Valley venture capitalists have or do not have between the time of user acquisition and profit. The less patience they have, the sooner they want to exploit the user data.

The latest news (hat tip Gary Marcus) gives us reason to think that V.C. patience is running dry, and the corresponding market in personal data is maturing. Turns out that EBay and PayPal recently changed their user agreements so that, if you’re a user of either of those services, you will receive marketing calls using any phone number you’ve provided them or that they have “have otherwise obtained.” There is no possibility to opt out, except perhaps to abandon the services. Oh, and they might also call you for surveys or debt collections. Oh, and they claim their intention is to “benefit our relationship.”

Presumably this means they might have bought your phone number from a data warehouse giant like Acxiom, if you didn’t feel like sharing it. Presumably this also means that they will use your shopping history to target the phone calls to be maximally “tailored” for you.

I’m mentally tacking this new fact on the same board as I already have the Verizon/AOL merger, which is all about AOL targeting people with ads based on Verizon’s GPS data, and the recent broohaha over RadioShack’s attempt to sell its user data at auction in order to pay off creditors. That didn’t go through, but it’s still a sign that the personal data market is ripening, and in particular that such datasets are becoming assets as important as land or warehouses.

Given how much venture capitalists like to brag about their return, I think we have reason to worry about the coming wave of “innovative” uses of our personal data. Telemarketing is the tip of the iceberg.

Uber is somewhat threatened in NYC

There have been a couple of moves recently that make Uber slightly more threatened in NYC than I had thought would be possible.

First, last week de Blasio made Uber and other “hail a ride” companies very annoyed when he suggested a plan that would require them to get city approval and pay $1000 every time they want to change their app’s user interface.

If you know anything at all about how tech companies work, you know this would be a serious friction if it goes through; user interfaces are changed on a weekly basis, to add features or even just test them. In response, an angry letter was sent to de Blasio from Twitter, Facebook, Google, Yahoo, and a bunch of other tech companies. Kind of a tech posse wielding its power.

In a different story, Uber has been attacked by four credit unions who loan money to taxi medallion purchasers. They argue that taxi medallions come with contracts that promise the owners exclusive rights over hailing, but that Uber, with its hailing app, has taken over their business. In particular, the definition of “hail” is coming under scrutiny.

On the one hand, it does seem to be a different act to raise your hands on Broadway versus using an app on your phone. But by the time we have chips implanted into our heads, just thinking the words “hail a taxi” might do the trick, and that’s where the grey area lives. Or, put it another way, yellow taxis might also want to have hailing apps, and in fact they really should.

What do you think? Is de Blasio simply a pawn of the taxi commission? Should we feel sorry for tech companies? I’m conflicted myself, especially because I still don’t understand the way insurance works with these things.

Driving While Black in the Bronx

This is the story of Q, a black man living in the Bronx, who kindly allowed me to interview him about his recent experience. The audio recording of my interview with him is available below as well.

Q was stopped in the Bronx driving a new car, the fourth time that week, by two rookie officers on foot. The officers told Q to “give me your fucking license,” and Q refused to produce his license, objecting to the tone of the officer’s request. When Q asked him why he was stopped, the officer told him that it was because of his tinted back windows, in spite of there being many other cars on the same block, and even next to him, with similarly tinted windows. Q decided to start recording the interaction on his phone after one of the cops used the n-word.

After a while seven cop cars came to the scene, and eventually a more polite policeman asked Q to produce his license, which he did. They brought him in, claiming they had a warrant for him. Q knew he didn’t actually have a warrant, but when he asked, they said it was a warrant for littering. It sounded like an excuse to arrest him because Q was arguing. He recorded them saying, “We should just lock this black guy up.”

They brought him to the precinct and Q asked him for a phone call. He needed to unlock his phone to get the phone number, and when he did, the policeman took his phone and ran out of the room. Q later found out his recordings had been deleted.

After a while he was assigned a legal aid lawyer, to go before a judge. Q asked the legal aid why he was locked up. She said there was no warrant on his record and that he’d been locked up for disorderly conduct. This was the third charge he’d heard about.

He had given up his car keys, his cell phone, his money, his watch and his house keys, all in different packages. When he went back to pick up his property while his white friend waited in the car, the people inside the office claimed they couldn’t find anything except his cell phone. They told him to come back at 9pm when the arresting officer would come in. Then Q’s white friend came in, and after Q explained the situation to him in front of the people working there, they suddenly found all of his possessions. Q thinks they assumed his friend was a lawyer because he was white and well dressed.

They took the starter plug out of his car as well, and he got his cell phone back with no videos. The ordeal lasted 12 hours altogether.

“The sad thing about it,” Q said, “is that it happens every single day. If you’re wearing a suit and tie it’s different, but when you’re wearing something fitted and some jeans, you’re treated as a criminal. It’s sad that people have to go through this on a daily basis, for what?”

Here’s the raw audio file of my interview with Q:

.

Putting the dick pic on the Snowden story

I’m on record complaining about how journalists dumb down stories in blind pursuit of “naming the victim” or otherwise putting a picture on the story.

But then again, sometimes that’s exactly what you need to do, especially when the story is super complicated. Case in point: the Snowden revelations story.

In the past 2 weeks I’ve seen the Academy Award winning feature length film CitizenFour, I’ve read Bruce Schneier’s recent book, Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles To Collect Your Data And Control Your World, and finally I watched John Oliver’s recent Snowden episode.

They were all great in their own way. I liked Schneier’s book, it was a quick read, and I’d recommend it to people who want to know more than Oliver’s interview shows us. He’s very very smart, incredibly well informed, and almost completely reasonable (unlike this review).

To be honest, though, when I recommend something to other people, I pick John Oliver’s approach; he cleverly puts the dick pic on the story (you have to reset it to the beginning):

Here’s the thing that I absolutely love about Oliver’s interview. He’s not absolutely smitten by Snowden, but he recognizes Snowden’s goal, and makes it absolutely clear what it means to people using the handy use case of how nude pictures get captured in the NSA dragnets. It is really brilliant.

Compared to Schneier’s book, Oliver is obviously not as informational. Schneier is a world-wide expert on security, and gives us real details on which governmental programs know what and how. But honestly, unless you’re interested in becoming a security expert, that isn’t so important. I’m a tech nerd and even for me the details were sometimes overwhelming.

Here’s what I want to concentrate on. In the last part of the book, Schneier suggests all sorts of ways that people can protect their own privacy, using all sorts of encryption tools and so on. He frames it as a form of protest, but it seems like a LOT of work to me.

Compare that to my favorite part of the Oliver interview, when Oliver asks Snowden (starting at minute 30:28 in the above interview) if we should “just stop taking dick pics.” Snowden’s answer is no: changing what we normally do because of surveillance is a loss of liberty, even if it’s dumb.

I agree, which is why I’m not going to stop blabbing my mouth off everywhere (I don’t actually send naked pictures of myself to people, I think that’s a generational thing).

One last thing I can’t resist saying, and which Schneier discusses at length: almost every piece of data collected about us by our government is more or less for sale anyway. Just think about that. It is more meaningful for people worried about large scale discrimination, like me, than it is for people worried about case-by-case pinpointed governmental acts of power and suppression.

Or, put it this way: when we are up in arms about the government having our dick pics, we forget that so do our phones, and so does Facebook, or Snapchat, not to mention all the backups on the cloud somewhere.

Affordable Housing Needs a Reset #OWS

I’m super proud of the latest Huffington Post piece that Alt Banking put out entitled Affordable Housing Needs a Reset. Here’s an excerpt:

We’ve been hearing a lot lately from New York Mayor de Blasio on his affordable housing plan. He says he will “build or preserve” 200,000 housing units, but the plan would only build 8,000 units a year. Unless it is radically changed, the mayor’s plan will squander public assets, enrich real estate developers, but do very little for the record number of people living in the shelter system or at risk of landing there.

Let’s first talk about how the term “affordable housing” is defined and whether it jives with our concept of the kinds of places New Yorkers can actually afford to live in. The mayor’s plan defines an apartment renting for $41,500 a year as affordable because a family of four with $138,435 in income can afford it ― even though that is more than twice the actual New York City median 4-person household income of $63,000. That is, most New Yorkers cannot afford an “affordable apartment” by the mayor’s standards.

The mayor’s plan tracks the pattern New York City has religiously followed for quite some time of trying to “incentivize” private development. The city effectively pays a fortune to private developers to build this kind of stuff. Here is a frightening statistic from the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development: in 2013, New York City gave private developers a pass on $1.2 billion in taxes in order to stimulate the building of 153,000 units of housing ― just 12,000 of which met the messed-up definition of affordability. Hard to believe we couldn’t have done a lot better by simply collecting those taxes.

Read the rest of the essay here.

The re-emergence of debtors’ prisons

Yesterday at my weekly Occupy meeting we watched videos called To Prison For Poverty by Brave New Films (Part I and Part II) before discussing them. Take a look, they are well done:

It’s not the first time this issue has come up recently; the NPR investigations into court fees from last May, called Guilty and Charged, led to a bunch of reports on issues similar to this. Probably the closest is the one entitled Unpaid Court Fees Land The Poor In 21st Century Debtors’ Prisons.

A few comments:

- Ferguson is now famous for having a basically white police force patrolling a basically black populace. But it also has this fines-and-fees-and-jails problem: fines and fees associated to mostly traffic violations accounted for 21% of the city’s budget in 2013. And there were more arrest warrants than people in Ferguson last year, mostly for non-violent offenses.

- But the debtors’ prison problem isn’t just a racial issue. The people profiled in the above video were white, which could have been a documentarian’s decision, but in any case is a fact: the poverty-to-prison system is screwing all poor people, not just minorities. This is in spite of the fact that the Supreme Court found it unconstitutional in the landmark 1983 case, Bearden v. Georgia.

- This sense that “everyone is screwed” creates solidarity among poor whites and poor blacks, and especially young people. The Ferguson protests have been multi-racial, for example. And if you’ve read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, you’ll recognize a historical pattern whereby political change happens when poor whites and poor blacks start working together.

- One interesting and scary question to emerge from the above stories is, how did so many fees and fines get attached to low-level misdemeanors in the first place? It seems like privatized probation and prison companies have a lot to do with it.

- In some cases, they are putting people in jail for days and weeks, which costs the government hundreds of dollars, in order to capture a small fee. That makes no sense.

- In other cases, the fees accumulate so fast that the poor person who committed the misdemeanor ends up being responsible for an outrageous amount of money, far surpassing the scale of the original misdeed, and all because they are poor. That also makes no sense.

- It’s not just for prisons either; all sorts of functions that we consider governmental functions have been privatized, like health and human services: child welfare services, homeless services, half-way houses, and more.

- In the worst cases, the original intent of the agency (“putting people on probation so they don’t have to be in jail”) has been perverted into an entirely different beast (“putting them in jail because they can’t pay their daily $35 probation fees”). The question we’d like to investigate further is, how did that happen and why?

Reverse-engineering Chinese censorship

This recent paper written by Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret Roberts explores the way social media posts are censored in China. It’s interesting, take a look, or read this article on their work.

Here’s their abstract:

Existing research on the extensive Chinese censorship organization uses observational methods with well-known limitations. We conducted the first large-scale experimental study of censorship by creating accounts on numerous social media sites, randomly submitting different texts, and observing from a worldwide network of computers which texts were censored and which were not. We also supplemented interviews with confidential sources by creating our own social media site, contracting with Chinese firms to install the same censoring technologies as existing sites, and—with their software, documentation, and even customer support—reverse-engineering how it all works. Our results offer rigorous support for the recent hypothesis that criticisms of the state, its leaders, and their policies are published, whereas posts about real-world events with collective action potential are censored.

Interesting that they got so much help from the Chinese to censor their posts. Also keep in mind a caveat from the article:

Yu Xie, a sociologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, says that although the study is methodologically sound, it overemphasizes the importance of coherent central government policies. Political outcomes in China, he notes, often rest on local officials, who are evaluated on how well they maintain stability. Such officials have a “personal interest in suppressing content that could lead to social movements,” Xie says.

I’m a sucker for reverse-engineering powerful algorithms, even when there are major caveats.

Women not represented in clinical trials

This recent NYTimes article entitled Health Researchers Will Get $10.1 Million to Counter Gender Bias in Studies spelled out a huge problem that kind of blows me away as a statistician (and as a woman!).

Namely, they have recently decided over at the NIH, which funds medical research in this country, that we should probably check to see how women’s health are affected by drugs, and not just men’s. They’ve decided to give “extra money” to study this special group, namely females.

Here’s the bizarre and telling explanation for why most studies have focused on men and excluded women:

Traditionally many investigators have worked only with male lab animals, concerned that the hormonal cycles of female animals would add variability and skew study results.

Let’s break down that explanation, which I’ve confirmed with a medical researcher is consistent with the culture.

If you are afraid that women’s data would “skew study results,” that means you think the “true result” is the result that works for men. Because adding women’s data would add noise to the true signal, that of the men’s data. What?! It’s an outrageous perspective. Let’s take another look at this reasoning, from the article:

Scientists often prefer single-sex studies because “it reduces variability, and makes it easier to detect the effect that you’re studying,” said Abraham A. Palmer, an associate professor of human genetics at the University of Chicago. “The downside is that if there is a difference between male and female, they’re not going to know about it.”

Ummm… yeah. So instead of testing the effect on women, we just go ahead and optimize stuff for men and let women just go ahead and suffer the side effects of the treatment we didn’t bother to study. After all, women only comprise 50.8% of the population, they won’t mind.

This is even true for migraines, where 2/3rds of migraine sufferers are women.

One reason they like to exclude women: they have periods, and they even sometimes get pregnant, which is confusing for people who like to have clean statistics (on men’s health). In fact my research contact says that traditionally, this bias towards men in clinical trials was said to protect women because they “could get pregnant” and then they’d be in a clinical trial while pregnant. OK.

I’d like to hear more about who is and who isn’t in clinical trials, and why.

Christian Rudder’s Dataclysm

Here’s what I’ve spent the last couple of days doing: alternatively reading Christian Rudder’s new book Dataclysm and proofreading a report by AAPOR which discusses the benefits, dangers, and ethics of using big data, which is mostly “found” data originally meant for some other purpose, as a replacement for public surveys, with their carefully constructed data collection processes and informed consent. The AAPOR folk have asked me to provide tangible examples of the dangers of using big data to infer things about public opinion, and I am tempted to simply ask them all to read Dataclysm as exhibit A.

Rudder is a co-founder of OKCupid, an online dating site. His book mainly pertains to how people search for love and sex online, and how they represent themselves in their profiles.

Here’s something that I will mention for context into his data explorations: Rudder likes to crudely provoke, as he displayed when he wrote this recent post explaining how OKCupid experiments on users. He enjoys playing the part of the somewhat creepy detective, peering into what OKCupid users thought was a somewhat private place to prepare themselves for the dating world. It’s the online equivalent of a video camera in a changing booth at a department store, which he defended not-so-subtly on a recent NPR show called On The Media, and which was written up here.

I won’t dwell on that aspect of the story because I think it’s a good and timely conversation, and I’m glad the public is finally waking up to what I’ve known for years is going on. I’m actually happy Rudder is so nonchalant about it because there’s no pretense.

Even so, I’m less happy with his actual data work. Let me tell you why I say that with a few examples.

Who are OKCupid users?

I spent a lot of time with my students this summer saying that a standalone number wouldn’t be interesting, that you have to compare that number to some baseline that people can understand. So if I told you how many black kids have been stopped and frisked this year in NYC, I’d also need to tell you how many black kids live in NYC for you to get an idea of the scope of the issue. It’s a basic fact about data analysis and reporting.

When you’re dealing with populations on dating sites and you want to conclude things about the larger culture, the relevant “baseline comparison” is how well the members of the dating site represent the population as a whole. Rudder doesn’t do this. Instead he just says there are lots of OKCupid users for the first few chapters, and then later on after he’s made a few spectacularly broad statements, on page 104 he compares the users of OKCupid to the wider internet users, but not to the general population.

It’s an inappropriate baseline, made too late. Because I’m not sure about you but I don’t have a keen sense of the population of internet users. I’m pretty sure very young kids and old people are not well represented, but that’s about it. My students would have known to compare a population to the census. It needs to happen.

How do you collect your data?

Let me back up to the very beginning of the book, where Rudder startles us by showing us that the men that women rate “most attractive” are about their age whereas the women that men rate “most attractive” are consistently 20 years old, no matter how old the men are.

Actually, I am projecting. Rudder never actually specifically tells us what the rating is, how it’s exactly worded, and how the profiles are presented to the different groups. And that’s a problem, which he ignores completely until much later in the book when he mentions that how survey questions are worded can have a profound effect on how people respond, but his target is someone else’s survey, not his OKCupid environment.

Words matter, and they matter differently for men and women. So for example, if there were a button for “eye candy,” we might expect women to choose more young men. If my guess is correct, and the term in use is “most attractive”, then for men it might well trigger a sexual concept whereas for women it might trigger a different social construct; indeed I would assume it does.

Since this isn’t a porn site, it’s a dating site, we are not filtering for purely visual appeal; we are looking for relationships. We are thinking beyond what turns us on physically and asking ourselves, who would we want to spend time with? Who would our family like us to be with? Who would make us be attractive to ourselves? Those are different questions and provoke different answers. And they are culturally interesting questions, which Rudder never explores. A lost opportunity.

Next, how does the recommendation engine work? I can well imagine that, once you’ve rated Profile A high, there is an algorithm that finds Profile B such that “people who liked Profile A also liked Profile B”. If so, then there’s yet another reason to worry that such results as Rudder described are produced in part as a result of the feedback loop engendered by the recommendation engine. But he doesn’t explain how his data is collected, how it is prompted, or the exact words that are used.

Here’s a clue that Rudder is confused by his own facile interpretations: men and women both state that they are looking for relationships with people around their own age or slightly younger, and that they end up messaging people slightly younger than they are but not many many years younger. So forty year old men do not message twenty year old women.

Is this sad sexual frustration? Is this, in Rudder’s words, the difference between what they claim they want and what they really want behind closed doors? Not at all. This is more likely the difference between how we live our fantasies and how we actually realistically see our future.

Need to control for population

Here’s another frustrating bit from the book: Rudder talks about how hard it is for older people to get a date but he doesn’t correct for population. And since he never tells us how many OKCupid users are older, nor does he compare his users to the census, I cannot infer this.

Here’s a graph from Rudder’s book showing the age of men who respond to women’s profiles of various ages:

We’re meant to be impressed with Rudder’s line, “for every 100 men interested in that twenty year old, there are only 9 looking for someone thirty years older.” But here’s the thing, maybe there are 20 times as many 20-year-olds as there are 50-year-olds on the site? In which case, yay for the 50-year-old chicks? After all, those histograms look pretty healthy in shape, and they might be differently sized because the population size itself is drastically different for different ages.

Confounding

One of the worst examples of statistical mistakes is his experiment in turning off pictures. Rudder ignores the concept of confounders altogether, which he again miraculously is aware of in the next chapter on race.

To be more precise, Rudder talks about the experiment when OKCupid turned off pictures. Most people went away when this happened but certain people did not:

Some of the people who stayed on went on a “blind date.” Those people, which Rudder called the “intrepid few,” had a good time with people no matter how unattractive they were deemed to be based on OKCupid’s system of attractiveness. His conclusion: people are preselecting for attractiveness, which is actually unimportant to them.

But here’s the thing, that’s only true for people who were willing to go on blind dates. What he’s done is select for people who are not superficial about looks, and then collect data that suggests they are not superficial about looks. That doesn’t mean that OKCupid users as a whole are not superficial about looks. The ones that are just got the hell out when the pictures went dark.

Race

This brings me to the most interesting part of the book, where Rudder explores race. Again, it ends up being too blunt by far.

Here’s the thing. Race is a big deal in this country, and racism is a heavy criticism to be firing at people, so you need to be careful, and that’s a good thing, because it’s important. The way Rudder throws it around is careless, and he risks rendering the term meaningless by not having a careful discussion. The frustrating part is that I think he actually has the data to have a very good discussion, but he just doesn’t make the case the way it’s written.

Rudder pulls together stats on how men of all races rate women of all races on an attractiveness scale of 1-5. It shows that non-black men find their own race attractive and non-black men find black women, in general, less attractive. Interesting, especially when you immediately follow that up with similar stats from other U.S. dating sites and – most importantly – with the fact that outside the U.S., we do not see this pattern. Unfortunately that crucial fact is buried at the end of the chapter, and instead we get this embarrassing quote right after the opening stats:

And an unintentionally hilarious 84 percent of users answered this match question:

Would you consider dating someone who has vocalized a strong negative bias toward a certain race of people?

in the absolute negative (choosing “No” over “Yes” and “It depends”). In light of the previous data, that means 84 percent of people on OKCupid would not consider dating someone on OKCupid.

Here Rudder just completely loses me. Am I “vocalizing” a strong negative bias towards black women if I am a white man who finds white women and asian women hot?

Especially if you consider that, as consumers of social platforms and sites like OKCupid, we are trained to rank all the products we come across to ultimately get better offerings, it is a step too far for the detective on the other side of the camera to turn around and point fingers at us for doing what we’re told. Indeed, this sentence plunges Rudder’s narrative deeply into the creepy and provocative territory, and he never fully returns, nor does he seem to want to. Rudder seems to confuse provocation for thoughtfulness.

This is, again, a shame. A careful conversation about the issues of what we are attracted to, what we can imagine doing, and how we might imagine that will look to our wider audience, and how our culture informs those imaginings, are all in play here, and could have been drawn out in a non-accusatory and much more useful way.

Wife beating education for sports fan and everyone else

Do you know what I am doing this morning? I’m glued to ESPN talk radio, which is 98.7FM in the NYC area, although it is a national station and can be streamed online as well.

Here’s a statement you might be surprised to hear from me. In the past decade, sports talk radio has become the best, rawest, and most honest source of information about how our culture condones and ignores violence against women, not to mention issues of race and homophobia. True fact. You are not going to hear this stuff from politicians or academics.

Right now I’m listening to the Mike & Mike program, which has guest Jemele Hill, who is killing it. I’m a huge fan of hers.

The specific trigger for the conversation today is the fact that NFL football player Ray Rice has been indefinitely suspended from playing now that a video has emerged of him beating his wife in the elevator. Previously we had only gotten to seen the video of her slumped body after he came out of the elevator with her. The police didn’t do much about it, and then the NFL responded with a paltry 2-game suspension, after which there was such a backlash (partly through sports radio!) that the commissioner promised to enact a stronger policy.

Questions being addressed right now as I type:

- Why didn’t the police give Rice a bigger penalty for beating his wife unconscious?

- Why didn’t the NFL ask for that video before now? Or did they, and now they’re lying?

- What does it say about the NFL that they had the wife, Janay Rice, apologize for her role in the incident?

- What did people think it would look like when a professional football player knocks out a woman?

- Did people really think she did something to deserve it, and now they are shocked to see that she didn’t?

Friday morning reading

I’m very gratified to say that my Lede Program for data journalism at Columbia is over, or at least the summer program is (some students go on to take Computer Science classes in the Fall).

My adorable and brilliant students gave final presentations on Tuesday and then we had a celebration Tuesday night at my house, and my bluegrass band played (didn’t know I have a bluegrass band? I play the fiddle! You can follow us on twitter!). It was awesome! I’m hoping to get some of their projects online soon, and I’ll definitely link to it when that happens.

It’s been an exciting week, and needless to say I’m exhausted. So instead of a frothy rant I’ll just share some reading with y’all:

- Andrew Gelman has a guest post by Phil Price on the worst infographic ever, which sadly comes from Vox. My students all know better than this. Hat tip Lambert Strether.

- Private equity firms are buying stuff all over the country, including Ferguson. I’m actually not sure this is a bad thing, though, if nobody else is willing to do it. Please discuss.

- Bloomberg has an interesting story about online PayDay loans and the world of investing. I am still on the search for someone who knows exactly how those guys target their ads online. Hat tip Aryt Alasti.

- Felix Salmon, now at Fusion, has set up a nifty interactive to help you figure out your lifetime earnings.

- Felix also set up this cool online game where you can play as a debt collector or a debtor.

- Is it time to end letter grades? Hat tip Rebecca Murphy.

- There’s a reason fast food workers are striking nationwide. The ratio of average CEO pay to average full-time worker pay is around 1252.

- People lie to women in negotiations. I need to remember this.

Have a great weekend!

Student evaluations: very noisy data

I’ve been sent this recent New York Times article by a few people (thanks!). It’s called Grading Teachers, With Data From Class, and it’s about how standardized tests are showing themselves to be inadequate to evaluate teachers, so a Silicon Valley-backed education startup called Panorama is stepping into the mix with a data collection process focused on student evaluations.

Putting aside for now how much this is a play for collecting information about the students themselves, I have a few words to say about the signal which one gets from student evaluations. It’s noisy.

So, for example, I was a calculus teacher at Barnard, teaching students from all over the Columbia University community (so, not just women). I taught the same class two semesters in a row: first in Fall, then in Spring.

Here’s something I noticed. The students in the Fall were young (mostly first semester frosh), eager, smart, and hard-working. They loved me and gave me high marks on all categories, except of course for the few students who just hated math, who would typically give themselves away by saying “I hate math and this class is no different.”

The students in the Spring were older, less eager, probably just as smart, but less hard-working. They didn’t like me or the class. In particular, they didn’t like how I expected them to work hard and challenge themselves. The evaluations came back consistently less excited, with many more people who hated math.

I figured out that many of the students had avoided this class and were taking it for a requirement, didn’t want to be there, and it showed. And the result was that, although my teaching didn’t change remarkably between the two semesters, my evaluations changed considerably.

Was there some way I could have gotten better evaluations from that second group? Absolutely. I could have made the class easier. That class wanted calculus to be cookie-cutter, and didn’t particularly care about the underlying concepts and didn’t want to challenge themselves. The first class, by contrast, had loved those things.

My conclusion is that, once we add “get good student evaluations” to the mix of requirements for our country’s teachers, we are asking for them to conform to their students’ wishes, which aren’t always good. Many of the students in this country don’t like doing homework (in fact most!). Only some of them like to be challenged to think outside their comfort zone. We think teachers should do those things, but by asking them to get good student evaluations we might be preventing them from doing those things. A bad feedback loop would result.

I’m not saying teachers shouldn’t look at student evaluations; far from it, I always did and I found them useful and illuminating, but the data was very noisy. I’d love to see teachers be allowed to see these evaluations without there being punitive consequences.

What can be achieved by Data Science?

This is a guest post by Sophie Chou, who recently graduated from Columbia in Computer Science and is on her way to the MIT Media Lab. Crossposted on Sophie’s blog.

“Data Science” is one of my least favorite tech buzzwords, second to probably “Big Data”, which in my opinion should be always printed followed by a winky face (after all, my data is bigger than yours). It’s mostly a marketing ploy used by companies to attract talented scientists, statisticians, and mathematicians, who, at the end of the day, will probably be working on some sort of advertising problem or the other.

Still, you have to admit, it does have a nice ring to it. Thus the title Democratizing Data Science, a vision paper which I co-authored with two cool Ph.D students at MIT CSAIL, William Li and Ramesh Sridharan.

The paper focuses on the latter part of the situation mentioned above. Namely, how can we direct these data scientists, aka scientists who interact with the data pipeline throughout the problem-solving process (whether they be computer scientists or programmers or statisticians or mathematicians in practice) towards problems focused on societal issues?

In the paper, we briefly define Data Science (asking ourselves what the heck it even means), then question what it means to democratize the field, and to what end that may be achieved. In other words, the current applications of Data Science, a new but growing field, in both research and industry, has the potential for great social impact, but in reality, resources are rarely distributed in a way to optimize the social good.

We’ll be presenting the paper at the KDD Conference next Sunday, August 24th at 11am as a highlight talk in the Bloomberg Building, 731 Lexington Avenue, NY, NY. It will be more like an open conversation than a lecture and audience participation and opinion is very welcome.

The conference on Sunday at Bloomberg is free, although you do need to register. There are three “tracks” going on that morning, “Data Science & Policy”, “Urban Computing”, and “Data Frameworks”. Ours is in the 3rd track. Sign up here!

If you don’t have time to make it, give the paper a skim anyway, because if you’re on Mathbabe’s blog you probably care about some of these things we talk about.

Weapon of Math Destruction: “risk-based” sentencing models

There was a recent New York Times op-ed by Sonja Starr entitled Sentencing, by the Numbers (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg and Linda Brown) which described the widespread use – in 20 states so far and growing – of predictive models in sentencing.

The idea is to use a risk score to help inform sentencing of offenders. The risk is, I guess, supposed to tell us how likely the person is to commit another act in the future, although that’s not specified. From the article:

The basic problem is that the risk scores are not based on the defendant’s crime. They are primarily or wholly based on prior characteristics: criminal history (a legitimate criterion), but also factors unrelated to conduct. Specifics vary across states, but common factors include unemployment, marital status, age, education, finances, neighborhood, and family background, including family members’ criminal history.

I knew about the existence of such models, at least in the context of prisoners with mental disorders in England, but I didn’t know how widespread it had become here. This is a great example of a weapon of math destruction and I will be using this in my book.

A few comments:

- I’ll start with the good news. It is unconstitutional to use information such as family member’s criminal history against someone. Eric Holder is fighting against the use of such models.

- It is also presumably unconstitutional to jail someone longer for being poor, which is what this effectively does. The article has good examples of this.

- The modelers defend this crap as “scientific,” which is the worst abuse of science and mathematics imaginable.

- The people using this claim they only use it for as a way to mitigate sentencing, but letting a bunch of rich white people off easier because they are not considered “high risk” is tantamount to sentencing poor minorities more.

- It is a great example of confused causality. We could easily imagine a certain group that gets arrested more often for a given crime (poor black men, marijuana possession) just because the police have that practice for whatever reason (Stop & Frisk). Then model would then consider any such man at a higher risk of repeat offending, but that’s not because any particular person is actually more likely to do it, but because the police are more likely to arrest that person for it.

- It also creates a negative feedback loop on the most vulnerable population: the model will impose longer sentencing on the population it considers most risky, which will in turn make them even riskier in the future, if “length of time in prison previously” is used as an attribute in the model, which is surely is.

- Not to be cynical, but considering my post yesterday, I’m not sure how much momentum will be created to stop the use of such models, considering how discriminatory it is.

- Here’s an extreme example of preferential sentencing which already happens: rich dude Robert H Richards IV raped his 3-year-old daughter and didn’t go to jail because the judge ruled he “wouldn’t fare well in prison.”

- How great would it be if we used data and models to make sure rich people went to jail just as often and for just as long as poor people for the same crime, instead of the other way around?

The economics of a McDonalds franchise

I’ve been fascinated to learn all sorts of things about how McDonalds operates their business in the past few days, as news broke about a recent NLRB decision to allow certain people who work in McDonalds to file complaints about their workplace and name McDonalds as a joint employer.

That sounds incredibly dull, right? The idea of letting McDonalds workers name McDonalds as an employer? Let me tell you a bit more. And this is all common knowledge, but I thought I’d gather it here for those of you who haven’t been following the story.

Most of the McDonalds joints you go to are franchises – 90% in this country. That means the business is owned by a franchisee, a person who pays good money (details here) for the right to run a McDonalds and is constrained by a huge long list of rules about how they have to do it.

The franchise owner attends Hamburger University and gets trained in all sorts of things, like exactly how things should look in the store, how customers should be funneled through space (maps included), how long each thing should take, and how to treat employees. There’s a QSC Playbook they are given (Quality, Service, and Cleanliness) as well as minute descriptions of how to organize their teams and even the vocabulary words they should use to encourage workers (see page 24 of the Shift Management Guide I found online here).

McDonalds also installs a real-time surveillance system into each McDonalds, which can calculate the rate of revenue brought in at a given moment, as well as the rate of pay going out, and when the ratio of those two numbers reaches a certain lower bound threshold, they encourage franchise owners to ask people to leave or delay people from clocking in. Encourage, mind you, not require. They are not the employers or anything remotely like that, clearly.

Take a step back here. What is the business model of a franchise? And when did McDonalds stop being a burger joint?

The idea is this. When you own a restaurant you have to deal with all these people who work for you and you have to deal with their complaints, and they might not like the way you treat them and they might organize against you or sue you. In order to contain your risks, you franchise. That effectively removes all of those people except one, the franchise owner, with whom you have an air-tight contract, written by a huge team of lawyers, which basically says that you get to cancel the franchise agreement for any minor infraction (where they’d lose a bunch of investment money), but most importantly it means the people actually working in a given franchise work for that one person, not for you, so their pesky legal issues are kept away from you. It’s a way to box in the legal risk of the parent company.

Restaurants aren’t the only business to learn that it’s easier to sell and manage a brand than it is to sell and manage an actual product. Hotels have been doing this for a long time, and avoid complaints and legal issues stemming from the huge population of service workers in hotels, mostly minority women.

For a copy of the original complaint that gave the details of McDonald’s control over workers, read this. For a better feel for being a McDonalds worker, please read this recent Reuters blog post written by a McDonalds worker. And for a better feel for being a McDonald’s franchise owner, read this recent Washington Post letter from a long-time McDonalds franchise owner who thinks workers are being unfairly treated.

Does that sounds confusing, that a franchise owner would side with the employees? It shouldn’t.

By nature of the franchise contract, the money actually available to a franchise owner is whatever’s left over after they pay McDonalds for advertising, and buy all the equipment and food that McDonalds tells them to from the sources that they tell them to, and after they pay for insurance on everything and for rent on the property (which McDonalds typically owns). In other words the only variable they have to tweak is the employer pay, but if they pay a living wage then they lose money on their business. In fact when franchise owners complain about the profit stream, McDonalds tells them to pay their workers less. McDonalds essentially controls everything except one variable, but since it’s a closed system of equations, that means the franchise owners have to decide between paying their workers reasonably and going in the red.

That’s not to say, of course, that McDonalds as an enterprise is at risk of losing money. In fact the parent corporation is making good money ($1.4 billion per quarter if you include international revenue), by squeezing the franchises. If the franchise owners had more leverage to negotiate better contracts, they could siphon off more revenue and then – possibly – share it with workers.

So back to the ruling. If upheld, and there’s a good chance it won’t be but I’m feeling hopeful today, this decision will allow people to point at McDonalds the corporation when they are treated badly, and will potentially allow a workers’ union to form. Alternatively it might energize the franchise owners to negotiate more flexible contracts, which could allow them to pay their workers better directly.

Surveillance in NYC

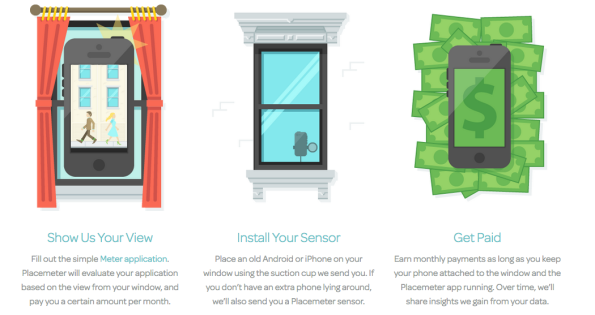

There’s a CNN video news story explaining how the NYC Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics is working with private start-up Placemeter to count and categorize New Yorkers, often with the help of private citizens who install cameras in their windows. Here’s a screenshot from the Placemeter website:

You should watch the video and decide for yourself whether this is a good idea.

Personally, it disturbs me, but perhaps because of my priors on how much we can trust other people with our data, especially when it’s in private hands.

To be more precise, there is, in my opinion, a contradiction coming from the Placemeter representatives. On the one hand they try to make us feel safe by saying that, after gleaning a body count with their video tapes, they dump the data. But then they turn around and say that, in addition to counting people, they will also categorize people: gender, age, whether they are carrying a shopping bag or pushing strollers.

That’s what they are talking about anyway, but who knows what else? Race? Weight? Will they use face recognition software? Who will they sell such information to? At some point, after mining videos enough, it might not matter if they delete the footage afterwards.

Since they are a private company I don’t think such information on their data methodologies will be accessible to us via Freedom of Information Laws either. Or, let me put that another way. I hope that MODA sets up their contract so that such information is accessible via FOIL requests.

Thanks for a great case study, Facebook!

I’m super excited about the recent “mood study” that was done on Facebook. It constitutes a great case study on data experimentation that I’ll use for my Lede Program class when it starts mid-July. It was first brought to my attention by one of my Lede Program students, Timothy Sandoval.

My friend Ernest Davis at NYU has a page of handy links to big data articles, and at the bottom (for now) there are a bunch of links about this experiment. For example, this one by Zeynep Tufekci does a great job outlining the issues, and this one by John Grohol burrows into the research methods. Oh, and here’s the original research article that’s upset everyone.

It’s got everything a case study should have: ethical dilemmas, questionable methodology, sociological implications, and questionable claims, not to mention a whole bunch of media attention and dissection.

By the way, if I sound gleeful, it’s partly because I know this kind of experiment happens on a daily basis at a place like Facebook or Google. What’s special about this experiment isn’t that it happened, but that we get to see the data. And the response to the critiques might be, sadly, that we never get another chance like this, so we have to grab the opportunity while we can.

Getting rid of teacher tenure does not solve the problem

There’s been a movement to make primary and secondary education run more like a business. Just this week in California, a lawsuit funded by Silicon Valley entrepreneur David Welch led to a judge finding that student’s constitutional rights were being compromised by the tenure system for teachers in California.

The thinking is that tenure removes the possibility of getting rid of bad teachers, and that bad teachers are what is causing the achievement gap between poor kids and well-off kids. So if we get rid of bad teachers, which is easier after removing tenure, then no child will be “left behind.”

The problem is, there’s little evidence for this very real achievement gap problem as being caused by tenure, or even by teachers. So this is a huge waste of time.

As a thought experiment, let’s say we did away with tenure. This basically means that teachers could be fired at will, say through a bad teacher evaluation score.

An immediate consequence of this would be that many of the best teachers would get other jobs. You see, one of the appeals of teaching is getting a comfortable pension at retirement, but if you have no idea when you’re being dismissed, then it makes no sense to put in the 25 or 30 years to get that pension. Plus, what with all the crazy and random value-added teacher models out there, there’s no telling when your score will look accidentally bad one year and you’ll be summarily dismissed.

People with options and skills will seek other opportunities. After all, we wanted to make it more like a business, and that’s what happens when you remove incentives in business!

The problem is you’d still need teachers. So one possibility is to have teachers with middling salaries and no job security. That means lots of turnover among the better teachers as they get better offers. Another option is to pay teachers way more to offset the lack of security. Remember, the only reason teacher salaries have been low historically is that uber competent women like Laura Ingalls Wilder had no other options than being a teacher. I’m pretty sure I’d have been a teacher if I’d been born 150 years ago.

So we either have worse teachers or education doubles in price, both bad options. And, sadly, either way we aren’t actually addressing the underlying issue, which is that pesky achievement gap.

People who want to make schools more like businesses also enjoy measuring things, and one way they like measuring things is through standardized tests like achievement scores. They blame teachers for bad scores and they claim they’re being data-driven.

Here’s the thing though, if we want to be data-driven, let’s start to maybe blame poverty for bad scores instead:

I’m tempted to conclude that we should just go ahead and get rid of teacher tenure so we can wait a few years and still see no movement in the achievement gap. The problem with that approach is that we’ll see great teachers leave the profession and no progress on the actual root cause, which is very likely to be poverty and inequality, hopelessness and despair. Not sure we want to sacrifice a generation of students just to prove a point about causation.

On the other hand, given that David Welch has a lot of money and seems to be really excited by this fight, it looks like we might have no choice but to blame the teachers, get rid of their tenure, see a bunch of them leave, have a surprise teacher shortage, respond either by paying way more or reinstating tenure, and then only then finally gather the data that none of this has helped and very possibly made things worse.