Archive

Stuff I’m reading

- A fascinating conversation with Gerald Posner, author of God’s Bankers: a History of Money and Power at the Vaticas, with crazy and horrible details of the Vatican’s bank’s dealings with the Nazis (hat tip Aryt Alasti). Also a review of the book in the New York Times.

- Nerding out on an interesting blog post by Laura McClay, who describes her involvement researching flood insurance (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg). One of my favorite point about insurance comes up in this piece, namely if you price insurance too accurately, it fails in its most basic function, and gets too expensive for those at highest risk.

- There’s a new social network created specifically to get people more involved in politics. It’s called Brigade, and it gets users to answer a bunch of questions about their beliefs. The business model hasn’t been unveiled yet, but this is information that political campaigns would find very valuable. Also see Alex Howard’s take. Could be scary, could be useful.

Guest post: Open-Source Loan-Level Analysis of Fannie and Freddie

This is a guest post by Todd Schneider. You can read the full post with additional analysis on Todd’s personal site.

[M]ortgages were acknowledged to be the most mathematically complex securities in the marketplace. The complexity arose entirely out of the option the homeowner has to prepay his loan; it was poetic that the single financial complexity contributed to the marketplace by the common man was the Gordian knot giving the best brains on Wall Street a run for their money. Ranieri’s instincts that had led him to build an enormous research department had been right: Mortgages were about math.

The money was made, therefore, with ever more refined tools of analysis.

—Michael Lewis, Liar’s Poker (1989)

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began reporting loan-level credit performance data in 2013 at the direction of their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency. The stated purpose of releasing the data was to “increase transparency, which helps investors build more accurate credit performance models in support of potential risk-sharing initiatives.”

The GSEs went through a nearly $200 billion government bailout during the financial crisis, motivated in large part by losses on loans that they guaranteed, so I figured there must be something interesting in the loan-level data. I decided to dig in with some geographic analysis, an attempt to identify the loan-level characteristics most predictive of default rates, and more. The code for processing and analyzing the data is all available on GitHub.

The “medium data” revolution

In the not-so-distant past, an analysis of loan-level mortgage data would have cost a lot of money. Between licensing data and paying for expensive computers to analyze it, you could have easily incurred costs north of a million dollars per year. Today, in addition to Fannie and Freddie making their data freely available, we’re in the midst of what I might call the “medium data” revolution: personal computers are so powerful that my MacBook Air is capable of analyzing the entire 215 GB of data, representing some 38 million loans, 1.6 billion observations, and over $7.1 trillion of origination volume. Furthermore, I did everything with free, open-source software.

What can we learn from the loan-level data?

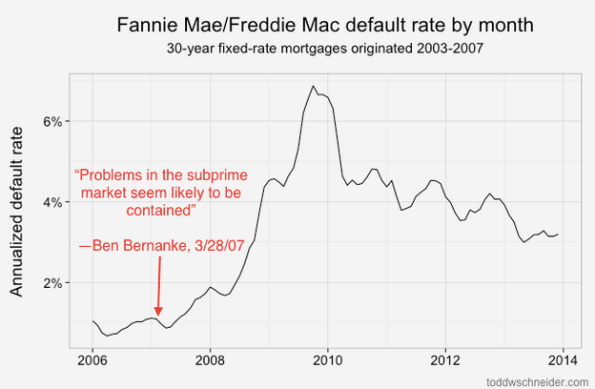

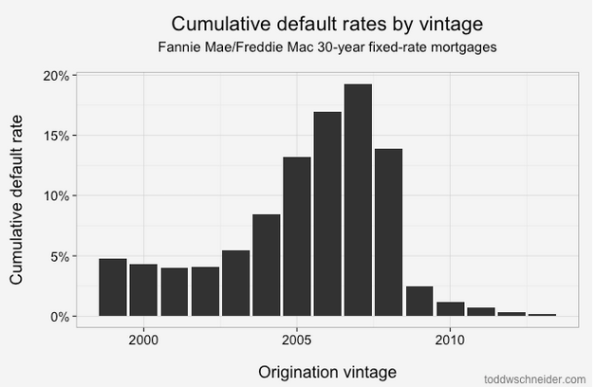

Loans originated from 2005-2008 performed dramatically worse than loans that came before them! That should be an extraordinarily unsurprising statement to anyone who was even slightly aware of the U.S. mortgage crisis that began in 2007:

About 4% of loans originated from 1999 to 2003 became seriously delinquent at some point in their lives. The 2004 vintage showed some performance deterioration, and then the vintages from 2005 through 2008 show significantly worse performance: more than 15% of all loans originated in those years became distressed.

From 2009 through present, the performance has been much better, with fewer than 2% of loans defaulting. Of course part of that is that it takes time for a loan to default, so the most recent vintages will tend to have lower cumulative default rates while their loans are still young. But there has also been a dramatic shift in lending standards so that the loans made since 2009 have been much higher credit quality: the average FICO score used to be 720, but since 2009 it has been more like 765. Furthermore, if we look 2 standard deviations from the mean, we see that the low end of the FICO spectrum used to reach down to about 600, but since 2009 there have been very few loans with FICO less than 680:

Tighter agency standards, coupled with a complete shutdown in the non-agency mortgage market, including both subprime and Alt-A lending, mean that there is very little credit available to borrowers with low credit scores (a far more difficult question is whether this is a good or bad thing!).

Geographic performance

Default rates increased everywhere during the bubble years, but some states fared far worse than others. I took every loan originated between 2005 and 2007, broadly considered to be the height of reckless mortgage lending, bucketed loans by state, and calculated the cumulative default rate of loans in each state:

4 states in particular jump out as the worst performers: California, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada. Just about every state experienced significantly higher than normal default rates during the mortgage crisis, but these 4 states, often labeled the “sand states”, experienced the worst of it.

Read more

If you’re interested in more technical discussion, including an attempt to identify which loan-level variables are most correlated to default rates (the number one being the home price adjusted loan to value ratio), read the full post on toddwschneider.com, and be sure to check out the project on GitHub if you’d like to do your own data analysis.

Nobody can keep track of all the big bank fraud cases #TBTF #OWS

If you’re anything like me, this week’s announcement that 5 banks – JP Morgan, Citigroup, Barclays, RBS, and UBS – have pleaded guilty to manipulating foreign exchange markets is both confusing and more than vaguely familiar.

It was a classic price fixing cartel, and it went along these lines: these big banks had all the business, being so big, and the traders got on a chat room and agreed to manipulate prices to make more money. The myth of the free market was suspended, and eventually they got caught, in large part because of leaving stupid messages like “If you aint cheating, you aint trying”.

But hold on, I could have sworn that these same banks, or a similar list of them, got in trouble for this already. Or was that LIBOR interest rate manipulation? Or was that for mortgage fraud? Or was that for robosigning?

Shit. I mean, here I am, someone who is actively taking an interest in financial reform, and I actually can’t remember all the fines, settlements, and fake guilty pleas to criminal charges.

I say “fake” because – yet again – nobody has gone to jail, and the banks found guilty have immediately been given waivers by the SEC to continue business as usual. According to this New York Times article, the Justice Department even delayed announcing the charges by a week so those waivers could be granted in time so that business wouldn’t even be disrupted. For fuck’s sake.

But again, same thing as all the other “big bank events” that we’ve grown tired of in the last few years. What it comes down to is fines, but then again, the continued quantitative easing has essentially been a gift of cash to those same banks, so I wouldn’t even count the fines as meaningful.

In fact I’d call this whole thing theater. And really repetitive, boring theater at that, where we all nod off because every scene is the same and they’ve turned up the heat too high.

The saddest part is that, given how very little we’ve improved about the integrity of the markets – I’d argue that we’ve actually gone backwards on incentives not to commit fraud, since now everything has been formalized as pathetic – we are bound to continue to see big banks committing fraud and then not getting any actual punishment. And we will all be so bored we won’t even keep track, because nobody can.

Fingers crossed – book coming out next May

As it turns out, it takes a while to write a book, and then another few months to publish it.

I’m very excited today to tentatively announce that my book, which is tentatively entitled Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy, will be published in May 2016, in time to appear on summer reading lists and well before the election.

Fuck yeah! I’m so excited.

p.s. Fight for 15 is happening now.

A Call For Justice #OccupyCitibank

In the beautiful words of Cleveland Browns wide receiver Andrew Hawkins:

I was taught that justice is a right that every American should have. Also justice should be the goal of every American. I think that’s what makes this country. To me, justice means the innocent should be found innocent. It means that those who do wrong should get their due punishment. Ultimately, it means fair treatment. So a call for justice shouldn’t offend or disrespect anybody. A call for justice shouldn’t warrant an apology.

…

Those who support me, I appreciate your support. But at the same time, support the causes and the people and the injustices that you feel strongly about. Stand up for them. Speak up for them. No matter what it is because that’s what America’s about and that’s what this country was founded on.

I think I will take him up on that suggestion, this morning at Citigroup Headquarters, 399 Park Avenue (near 54th Street) at 10:30am, in part inspired by Liz Warren’s speech from last week. See you there!

Liz Warren nails it

I don’t have enough time for a full post today, but if you haven’t already, please watch Liz Warren’s speech from last Friday. She lays out the facts about Citigroup in an uncomplicated way. Surprising and refreshing coming from a politician.

Join Occupy the SEC in Pushing Congress to Reject Dodd-Frank Deregulation

There’s some tricky business going on right now in politics, with a bunch of ridiculous last-minute negotiations to roll back elements of Dodd-Frank and aid Wall Street banks in the current budget deal. Hell, it’s the end of the year, and people are distracted, so the public won’t mind if the banks get formal government backing for their risky trades, right?

Occupy the SEC has a petition you can sign, located here, which is opposed to these changes. You might remember Occupy the SEC for their incredible work in public comments on the Dodd-Frank bill in the first place. I urge you to go take a look at their petition and, if you agree with them, sign it.

After you sign the petition, feel free to treat yourself to some holiday satire and cheer, namely The 2014 Haters Guide To The Williams-Sonoma Catalog.

What Happens as a Bubble Deflates?

Having written a couple of guest posts about bubbles possibly inflating (college tuition, high end Manhattan condos), I thought it might be interesting to consider what a deflating bubble looks like.

A number of observers point to the oil markets, where the price of crude has fallen by about 30% since June of this year, to a multi-year low today of about $75.50 per barrel. Just last spring, Bloomberg was reporting on how the drilling and exploration business in the US was heavily dependent on the issuance of junk rated debt – over $160 billion worth by some measures – to fund the shale drilling that has been so popular lately. The junk debt had been popular because it was a source of relatively cheap funds, thanks in part to the Federal Reserve’s efforts with Quantitative Easing to drive down bond yields. Oil and shale exploration are expensive and there are quite a few people that believe that certain types of exploration only make economic sense when the price of oil is above a certain level – say $80 a barrel (or perhaps even higher). Now that the price of oil has plummeted, there is a possibility that a whole collection of oil drillings and mines are underwater, so to speak, and no longer profitable.

Funding a bunch of expensive exploration with junk bonds makes things complicated and speculative. For instance, a substantial portion of these junk offerings were purchased by issuers of collateralized loan obligations (CLO) and then rated (up to the AAA level), securitized and distributed to an audience of investors who may or may not have been investing in energy related debt otherwise. CLOs are being issued at a record pace, by the way, and 2014 is on track to be the highest issuance year ever, exceeding the pre-crisis peak in 2007 of $93 billion. If the energy exploration companies that issued junk debt are no longer profitable and getting squeezed by the falling price of oil, will that lead to a bunch of companies defaulting and then sending shockwaves through the securitized market, via CLOs? (Note – the CLO market is much smaller than the subprime mortgage backed collateralized debt obligation market got to be before the 2007 implosion and energy companies are only a portion of the total issuance).

One thing that happens when investable asset prices fall, is that a bunch of people think that maybe it means there’s a new buying opportunity – a chance to get a hot asset at a cheap price on the expectation that prices will spring back up again soon. That’s what a bunch of hedge funds did a couple of weeks ago, betting that the sharp fall in oil would turn around. And then it fell another 6 or 7% to today’s levels. If oil prices continue to fall, as some speculate may happen, that would be called “catching a falling knife” and the investors may end up feeling rather burned by their optimism. Once cut by the falling knife, some investors become reluctant to come back a re-test their theory on rising prices, and this can contribute to a negative spiral for the falling asset.

I learned from my father-in-law, who worked at an oil company his whole life until he retired, that the oil business is always complicated. Up and down, supply and demand; they don’t work the way you’d think they would. When oil prices go down, gasoline gets cheaper, so people drive more, which drives prices back up (unless people are driving less and buying fewer cars, as appears to be happening now, perhaps because of those darn millennials and their urbanization and bike riding). Plus, there’s international politics, with Russian, OPEC, the Middle East, China the drive for energy independence, solar power, etc. On the other hand, gasoline and home heating oil and such are getting cheaper, which is a nice bonus for consumers, particularly in more car dependent regions. The economy benefits from the effect of extra money in the hands of consumers as that money gets spent elsewhere (other than on oil executives third or fourth homes, presumably). Oil is complicated.

But oil can and does crash. When it does, it can have a wider adverse impact on local oil-dependent economies, like Texas in the 80’s or perhaps, North Dakota, today. While there are a number of mysterious factors at play in the current fall in oil prices, the knock-on effects are starting to pile up. Oil producers are cutting production, idling rigs and cutting prices to stay competitive. The somewhat worried sounding consensus is that there is “too much oil supply” currently. The speculative portion of the oil market will be hit hardest, i.e. the junk-debt fueled shale companies. At some point, investors in the CLOs (and regular debt) backed by this highly leveraged debt from companies that aren’t profitable anymore, are going to get nervous (yields on such debt are already quite a bit higher) and start selling. In all likelihood, some exploration companies will fail. I wouldn’t describe it as a fear environment yet – in many cases the junk debt from exploration companies doesn’t come due for a few years – but the seeds of worry have been planted on fertile ground. One observer described the current environment as a “negative bubble”, with a herd mentality driving investors away from any optimistic assumptions for the market.

Why should we care? For most consumers, the most likely impact of a continuing deflation in oil prices will, as I mentioned, be cheaper gas and heating costs. When the housing market crashed, the negative impact was mostly felt by average Americans, as wealth was destroyed up and down the block, whereas the oil market seems very different and more removed. Still, it’s fascinating and instructive to watch the dynamics of a (potential) collapse of a bubble – on exploration, shale, oil prices, international politics – and the odds are high for unexpected consequences and global volatility. What will happen to the recent growth in solar and other renewable energies, if the price of the competing product gets much cheaper? What about the local politics of fracking? What kind of exposure do banks have to the oil markets and will it trigger any regulatory issues? What will happen to the international politicians, who like moving chess pieces around the Middle East map if oil-producing countries lose their political clout? Also, it’s odd that the Fed’s efforts to fight deflation have contributed, in part, to a price collapse of a crucial commodity, via QE-fueled easy money helping to push oil producers to dig up too much oil? How will the Fed react to this challenge?

I don’t know the answer, nor do I expect anyone else does either. But oil and energy are hugely important issues to most Americans (and the people of other countries, too, obviously) and to the national and global economies – not as big as housing, but pretty close. What happens in the next few months may affect many of us and it bears watching how our regulators, politicians, mega-companies and generals respond to the emerging (potential) collapse.

Alt Banking in Huffington Post #OWS

Great news! The Alt Banking group had a piece published today in the Huffington Post entitled With Economic Justice For All, about our hopes for the next Attorney General.

For the sake of the essay, we coined the term “marble columns” to mean the opposite of “broken windows.” Instead of getting arrested for nothing, you never get arrested, as long as you work at a company with marble columns. For more, take a look at the whole piece!

Also, my good friend and bandmate Tom Adams (our band, the Tomtown Ramblers, is named after him) will be covering for me on mathbabe for the next few days while I’m away in Haiti. Please make him feel welcome!

Bitcoin provocations

Yesterday at the Alt Banking meeting we had a special speaker and member, Josh Snodgrass (not his real name), come talk to us about Bitcoin, the alternative “cryptocurrency”. I’ll just throw together some fun and provocative observations that came from the meeting.

- First, Josh demonstrated how quickly you can price alternative currencies, by giving out a few of our Alt Banking “52 Shades of Greed” cards and stipulating that the jacks (I had a jack) were worth 1 “occudollar” but the 2’s (I also had a 2) were worthy 1,000,000,000 occudollars. Then he paid me $1 for my jack, which made me a billionaire. After thinking for a minute, I paid him $5 to get my jack back, which made me a multibillionaire. Come to think of it I don’t think I got that $5 back after the meeting.

- There’s a place you can have lunch in the city that accepts Bitcoin. I think it’s called Pita City.

- The idea behind Bitcoin is that you don’t have to have a trustworthy middleman in order to buy stuff with it. But in fact, the “bitcoin wallet” companies are increasingly playing the role of the trusted middlemen, especially considering it takes on average 10 minutes, but sometimes up to 40 minutes, of computing time to finish a transaction. If you want to leave the lunch place after lunch, you’d better have a middleman that the shop owner trusts or you could be sitting there for a while.

- People compare bitcoin to other alternative currencies like the Ithaca Hours, but there are two very important differences.

- First, Ithaca Hours, and other local currencies, are explicitly intended to promote local businesses: you pay for your bread with them, and the bread company you give money to buys ingredients with them, and they need to buy from someone who accepts them, which is by construction a local business.

- Second, local currencies like the Madison East Side Babysitting Coop’s “popsicle currency” are very low tech, used my middle class people to represent labor, whereas Bitcoin is highly technical and used primarily by technologists and other fancy people.

- There is class divide and a sophistication divide here, in other words.

- Speaking of sophistication, we had an interesting discussion about whether it would ever make sense to have bitcoin banks and – yes – fractional reserve bitcoin banking. On the one hand, since there’s a limit to the number of overall bitcoins, you can’t have everyone pretending they can pay a positive interest rate on all the bitcoin every year, but on the other hand a given individual can always write a contract saying they’d accept 100 bitcoins now and pay back 103 in a year, because it might just be a bet on the dollar value of bitcoins in a year. And in the meantime that person can lend out bitcoins to people, knowing full well they won’t all be spent at once. Altogether that looks a lot like fractional reserve bitcoin banking, which would effectively increase the number of bitcoins in circulation.

- Also, what about derivatives based on bitcoins? Do they already exist?

- Remaining question: will bitcoins ever actually be usable and trustworthy for people to send money to their families across the world below the current cost? And below the cost of whatever disruptions are being formulated in the money business by Paypal and Google and whoever else?

Update: there will be a Bitcoin Hackathon at NYU next weekend (hat tip Chris Wiggins). More info here.

Links (with annotation)

I’ve been heads down writing this week but I wanted to share a bunch of great stuff coming out.

- Here’s a great interview with machine learning expert Michael Jordan on various things including the big data bubble (hat tip Alan Fekete). I had a similar opinion over a year ago on that topic. Update: here’s Michael Jordan ranting about the title for that interview (hat tip Akshay Mishra). I never read titles.

- Have you taken a look at Janet Yellen’s speech on inequality from last week? She was at a conference in Boston about inequality when she gave it. It’s a pretty amazing speech – she acknowledges the increasing inequality, for example, and points at four systems we can focus on as reasons: childhood poverty and public education, college costs, inheritances, and business creation. One thing she didn’t mention: quantitative easing, or anything else the Fed has actual control over. Plus she hid behind the language of economics in terms of how much to care about any of this or what she or anyone else could do. On the other hand, maybe it’s the most we could expect from her. The Fed has, in my opinion, already been overreaching with QE and we can’t expect it to do the job of Congress.

- There’s a cool event at the Columbia Journalism School tomorrow night called #Ferguson: Reporting a Viral News Story (hat tip Smitha Corona) which features sociologist and writer Zeynep Tufekci among others (see for example this article she wrote), with Emily Bell moderating. I’m going to try to go.

- Just in case you didn’t see this, Why Work Is More And More Debased (hat tip Ernest Davis).

- Also: Poor kids who do everything right don’t do better than rich kids who do everything wrong (hat tip Natasha Blakely).

- Jesse Eisenger visits the defense lawyers of the big banks and writes about his experience (hat tip Aryt Alasti).

After writing this list, with all the hat tips, I am once again astounded at how many awesome people send me interesting things to read. Thank you so much!!

Guest post: New Federal Banking Regulations Undermine Obama Infrastructure Stance

This is a guest post by Marc Joffe, a former Senior Director at Moody’s Analytics, who founded Public Sector Credit Solutions in 2011 to educate the public about the risk – or lack of risk – in government securities. Marc published an open source government bond rating tool in 2012 and launched a transparent credit scoring platform for California cities in 2013. Currently, Marc blogs for Bitvore, a company which sifts the internet to provide market intelligence to municipal bond investors.

Obama administration officials frequently talk about the need to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Yet new regulations published by the Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC run counter to this policy by limiting the market for municipal bonds.

On Wednesday, bank regulators published a new rule requiring large banks to hold a minimum level of high quality liquid assets (HQLAs). This requirement is intended to protect banks during a financial crisis, and thus reduce the risk of a bank failure or government bailout. Just about everyone would agree that that’s a good thing.

The problem is that regulators allow banks to use foreign government securities, corporate bonds and even stocks as HQLAs, but not US municipal bonds. Unless this changes, banks will have to unload their municipal holdings and won’t be able to purchase new state and local government bonds when they’re issued. The new regulation will thereby reduce the demand for bonds needed to finance roads, bridges, airports, schools and other infrastructure projects. Less demand for these bonds will mean higher interest rates.

Municipal bond issuance is already depressed. According to data from SIFMA, total municipal bonds outstanding are lower now than in 2009 – and this is in nominal dollar terms. Scary headlines about Detroit and Puerto Rico, rating agency downgrades and negative pronouncements from market analysts have scared off many investors. Now with banks exiting the market, the premium that local governments have to pay relative to Treasury bonds will likely increase.

If the new rule had limited HQLA’s to just Treasuries, I could have understood it. But since the regulators are letting banks hold assets that are as risky as or even riskier than municipal bonds, I am missing the logic. Consider the following:

- No state has defaulted on a general obligation bond since 1933. Defaults on bonds issued by cities are also extremely rare – affecting about one in one thousand bonds per year. Other classes of municipal bonds have higher default rates, but not radically different from those of corporate bonds.

- Bonds issued by foreign governments can and do default. For example, private investors took a 70% haircut when Greek debt was restructured in 2012.

- Regulators explained their decision to exclude municipal bonds because of thin trading volumes, but this is also the case with corporate bonds. On Tuesday, FINRA reported a total of only 6446 daily corporate bond trades across a universe of perhaps 300,000 issues. So, in other words, the average corporate bond trades less than once per day. Not very liquid.

- Stocks are more liquid, but can lose value very rapidly during a crisis as we saw in 1929, 1987 and again in 2008-2009. Trading in individual stocks can also be halted.

Perhaps the most ironic result of the regulation involves municipal bond insurance. Under the new rules, a bank can purchase bonds or stock issued by Assured Guaranty or MBIA – two major municipal bond insurers – but they can’t buy state and local government bonds insured by those companies. Since these insurance companies would have to pay interest and principal on defaulted municipal securities before they pay interest and dividends to their own investors, their securities are clearly more risky than the insured municipal bonds.

Regulators have expressed a willingness to tweak the new HQLA regulations now that they are in place. I hope this is one area they will reconsider. Mandating that banks hold safe securities is a good thing; now we need a more data-driven definition of just what safe means. By including municipal securities in HQLA, bank regulators can also get on the same page as the rest of the Obama administration.

Crime and punishment

When I was prepping for my Slate Money podcast last week I read this column by Matt Levine at Bloomberg on the Citigroup settlement. In it he raises the important question of how the fine amount of $7 billion was determined. Here’s the key part:

Citi’s and the Justice Department’s approaches both leave something to be desired. Citi’s approach seems to be premised on the idea that the misconduct was securitizing mortgages: The more mortgages you did, the more you gotta pay, regardless of how they performed. The DOJ’s approach, on the other hand, seems to be premised on the idea that the misconduct was sending bad e-mails about mortgages: The more “culpable” you look, the more it should cost you, regardless of how much damage you did.

I would have thought that the misconduct was knowingly securitizing bad mortgages, and that the penalties ought to scale with the aggregate badness of Citi’s mortgages. So, for instance, you’d want to measure how often Citi’s mortgages didn’t match up to its stated quality-control standards, and then compare the actual financial performance of the loans that didn’t meet the standards to the performance of the loans that did. Then you could say, well, if Citi had lived up to its promises, investors would have lost $X billion less than they actually did. And then you could fine Citi that amount, or some percentage of that amount. And you could do a similar exercise for the other big banks — JPMorgan, say, which already settled, or Bank of America, which is negotiating its settlement — and get comparable amounts that appropriately balance market share (how many bad mortgages did you sell?) and culpability (how bad were they?).

I think he nailed something here, which has eluded me in the past, namely the concept of what comprises evidence of wrongdoing and how that translates into punishment. It’s similar to what I talked about in this recent post, where I questioned what it means to provide evidence of something, especially when the data you are looking for to gather evidence has been deliberately suppressed by either the people committing wrongdoing or by other people who are somehow gaining from that wrongdoing but are not directly involved.

Basically the way I see Levine’s argument is that the Department of Justice used a lawyerly definition of evidence of wrongdoing – namely, through the existence of emails saying things like “it’s time to pray.” After determining that they were in fact culpable, they basically did some straight-up negotiation to determine the fee. That negotiation was either purely political or was based on information that has been suppressed, because as far as anyone knows the number was kind of arbitrary.

Levine was suggesting a more quantitative definition for evidence of wrongdoing, which involves estimating both “how much you know” and “how much damage you actually did” to determine the damage, and then some fixed transformation of that damage becomes the final fee. I will ignore Citi’s lawyers’ approach since their definition was entirely self-serving.

Here’s the thing, there are problems with both approaches. For example, with the lawyerly approach, you are basically just sending the message that you should never ever write some things on email, and most or at least many people know that by now. In other words, you are training people to game the system, and if they game it well enough, they won’t get in trouble. Of course, given that this was yet another fine and nobody went to jail, you could make the argument – and I did on the podcast – that nobody got in trouble anyway.

The problem with the quantitative approach, is that first of all you still need to estimate “how much you knew” which again often goes back to emails, although in this case could be estimated by how often the stated standards were breached, and second of all, when taken as a model, can be embedded into the overall trading model of securities.

In other words, if I’m a quant at a nasty place that wants to trade in toxic securities, and I know that there’s a chance I’d be caught but I know the formula for how much I’d have to pay if I got caught, then I could include this cost, in addition to an estimate of the likelihood for getting caught, in an optimization engine to determine exactly how many toxic securities I should sell.

To avoid this scenario, it makes sense to have an element of randomness in the punishments for getting caught. Every now and then the punishment should be much larger than the quantitative model might suggest, so that there is less of a chance that people can incorporate the whole shebang into their optimization procedure. So maybe what I’m saying is that arriving at a random number, like the DOJ did, is probably better even though it is less satisfying.

Another possibility to actually deter crimes would be to arbitrarily increasing the likelihood of catching people up to no good, but that has been bounded from above by the way the SEC and the DOJ actually work.

Review: House of Debt by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi

I just finished House of Debt by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, which I bought as a pdf directly from the publisher.

This is a great book. It’s well written, clear, and it focuses on important issues. I did not check all of the claims made by the data but, assuming they hold up, the book makes two hugely important points which hopefully everyone can understand and debate, even if we don’t all agree on what to do about them.

First, the authors explain the insufficiency of monetary policy to get the country out of recession. Second, they suggest a new way to structure debt.

To explain these points, the authors do something familiar to statisticians: they think about distributions rather than averages. So rather than talking about how much debt there was, or how much the average price of houses fell, they talked about who was in debt, and where they lived, and which houses lost value. And they make each point carefully, with the natural experiments inherent in our cities due to things like available land and income, to try to tease out causation.

Their first main point is this: the financial system works against poor people (“borrowers”) much more than rich people (“lenders”) in times of crisis, and the response to the financial crisis exacerbated this discrepancy.

The crisis fell on poor people much more heavily: they were wiped out by the plummeting housing prices, whereas rich people just lost a bit of their wealth. Then the government stepped in and protected creditors and shareholders but didn’t renegotiate debt, which protected lenders but not borrowers. This is a large reason we are seeing so much increasing inequality and why our economy is stagnant. They make the case that we should have bailed out homeowners not only because it would have been fair but because it would have been helpful economically.

The authors looked into what actually caused the Great Recession, and they come to a startling conclusion: that the banking crisis was an effect, rather than a cause, of enormous household debt and consumer pull-back. Their narrative goes like this: people ran up debt, then started to pull back, and and as a result the banking system collapsed, as it was utterly dependent on ever-increasing debt. Moreover, the financial system did a very poor job of figuring out how to allocate capital and the people who made those loans were not adequately punished, whereas the people who got those loans were more than reasonably punished.

About half of the run-up of household debt was explained by home equity extraction, where people took out money from their home to spend on stuff. This is partly due to the fact that, in the meantime, wages were stagnant and home equity was a big thing and was hugely available.

But the authors also made the case that, even so, the bubble wasn’t directly caused by rising home valuations but rather to securitization and the creation of “financial innovation” which made investors believe they were buying safe products which were in fact toxic. In their words, securities are invented to exploit “neglected risks” (my experience working in a financial risk firm absolutely agrees to this; whenever you hear the phrase “financial innovation,” please interpret it to mean “an instrument whose risk hides somewhere in the creases that investors are not yet aware of”).

They make the case that debt access by itself elevates prices and build bubbles. In other words, it was the sausage factory itself, producing AAA-rated ABS CDO’s that grew the bubble.

Next, they talked about what works and what doesn’t, given this distributional way of looking at the household debt crisis. Specifically, monetary policy is insufficient, since it works through the banks, who are unwilling to lend to the poor who are already underwater, and only rich people benefit from cheap money and inflated markets. Even at its most extreme, the Fed can at most avoid deflation but it not really help create inflation, which is what debtors need.

Fiscal policy, which is to say things like helicopter money drops or added government jobs, paid by taxpayers, is better but it makes the wrong people pay – high income earners vs. high wealth owners – and isn’t as directly useful as debt restructuring, where poor people get a break and it comes directly from rich people who own the debt.

There are obstacles to debt restructuring, which are mostly political. Politicians are impotent in times of crisis, as we’ve seen, so instead of waiting forever for that to happen, we need a new kind of debt contract that automatically gets restructured in times of crisis. Such a new-fangled contract would make the financial system actually spread out risk better. What would that look like?

The authors give two examples, for mortgages and student debt. The student debt example is pretty simple: how quickly you need to pay back your loans depends in part on how many jobs there are when you graduate. The idea is to cushion the borrower somewhat from macro-economic factors beyond their control.

Next, for mortgages, they propose something the called the shared-responsibility mortgage. The idea here is to have, say, a 30-year mortgage as usual, but if houses in your area lost value, your principal and monthly payments would go down in a commensurate way. So if there’s a 30% drop, your payments go down 30%. To compensate the lenders for this loss-share, the borrowers also share the upside: 5% of capital gains are given to the lenders in the case of a refinancing.

In the case of a recession, the creditors take losses but the overall losses are smaller because we avoid the foreclosure feedback loops. It also acts as a form of stimulus to the borrowers, who are more likely to spend money anyway.

If we had had such mortgage contracts in the Great Recession, the authors estimate that it would have been worth a stimulus of $200 billion, which would have in turn meant fewer jobs lost and many fewer foreclosures and a smaller decline of housing prices. They also claim that shared-responsibility mortgages would prevent bubbles from forming in the first place, because of the fear of creditors that they would be sharing in the losses.

A few comments. First, as a modeler, I am absolutely sure that once my monthly mortgage payment is directly dependent on a price index, that index is going to be manipulated. Similarly as a college graduate trying to figure out how quickly I need to pay back my loans. And depending on how well that manipulation works, it could be a disaster.

Second, it is interesting to me that the authors make no mention of the fact that, for many forms of debt, restructuring is already a typical response. Certainly for commercial mortgages, people renegotiate their principal all the time. We can address the issue of how easy it is to negotiate principal directly by talking about standards in contracts.

Having said that I like the idea of having a contract that makes restructuring automatic and doesn’t rely on bypassing the very real organizational and political frictions that we see today.

Let me put it this way. If we saw debt contracts being written like this, where borrowers really did have down-side protection, then the people of our country might start actually feeling like the financial system was working for them rather than against them. I’m not holding my breath for this to actually happen.

How do we prevent the next Tim Geithner?

When you hate on certain people and things as long as I’ve hated on the banking system and Tim Geithner, you start to notice certain things. Patterns.

I read Tim Geithner’s book Stress Test last week, and instead of going through and sharing all the pains of reading it, which were many, I’m going to make one single point.

Namely, Tim was unqualified for his jobs and head of the NY Fed, during the crisis, and then as Obama’s Treasury Secretary. He says so a bunch of times and I believe him. You should too.

He even is forced at some point to admit he had no idea what banks really did, and since he needed someone or something to blame for his deep ignorance, he somehow manages to say that Brooksley Born was right, that derivatives should have been regulated, but that since she was at the CFTC everybody (read: Geithner’s heroes Larry Summers and Robert Rubin) dismissed her out of hand, and that as a result he had no ability to look into the proliferating shadow banking or stuff going on at all the investment banks and hedge funds. So it was kind of her fault that he wasn’t forced to understand stuff, even though she warned people, and when shit got real, all he could do was preserve the system because the alternative would be chaos. And people should fucking thank him. That’s his 600 page book in a nutshell.

Let’s put aside Tim Geithner’s mistakes and his narrow outlook on what could have been done better, and even what Dodd-Frank should accomplish, for a moment. It’s hard to resist complaining about those things, but I’ll do my best.

The truth is, Tim Geithner was a perfect product of the system. He was an effect, not a cause.

When I dwell on the fact that he got the NY Fed job with no in-the-weeds knowledge or experience on how banks operate, there’s no reason, not one single reason, to think it’s not going to happen again.

What’s going to prevent the next NY Fed bank head from being as unqualified as Tim Geithner?

Put it another way: how could we possibly expect the people running the regulators and the Treasury and the Fed to actually understand the system, when they are appointed the way they are? In case you missed it, the process currently is their ability to get along with Larry Summers and Robert Rubin and to look like a banker.

Before you go telling me I’m asking for a Goldman Sachs crony to take over all these positions, I’m not. It’s actually not impossible to understand this system for a curious, smart, skeptical, and patient person who asks good questions and has the power to make meetings with heads of trading floors. And you don’t have to become captured when you do that. You can remember that it’s your job to understand and regulate the system, that it’s actually a perfectly reasonable way to protect the country. From bankers.

Here’s a scary thought, which would be going in the exact wrong direction: we have Hillary Clinton as president and she brings in all the usual suspects to be in charge of this stuff, just like Obama did. Ugh.

I feel like a questionnaire is in order for anyone being considered for one of these jobs. Things like, how does overnight lending work, and what is being used for collateral, and what have other countries done in moments of financial crisis, and how did that work out for them, and what is a collateralized debt obligation and how does one assess the associated risks and who does that and why. Please suggest more.

Reading Geithner’s Stress Test

I’m reading Tim Geithner’s new book Stress Test: Reflection on Financial Crises in preparation for a discussion in this week’s Slate Money podcast. I also plan to write a review here.

I don’t want to say too much because I’m not even halfway through but here’s one thing: Geithner is surprisingly honest about certain things and predictably dishonest, or at least misleading, about other things.

And although at first I thought it would be purely painful to read this book, since I don’t have any respect for the guy, now I’m glad I’m doing it, because it exposes so much about how the old boys network operates. It’s material.

Let’s stop talking about HFT for a little while

It’s unusual that I find myself in the position of defending Wall Street activities, but here goes.

I just don’t think HFT is that big of a deal relative to other Wall Street evils. I have written a couple of times about HFT and I’m not a huge fan, and I don’t buy the “liquidity is good and more liquidity is better” argument: at some point enough is enough. I do think that day-to-day investors have largely benefitted from it but that people whose money is in massive funds which are regularly traded have seen their money get skimmed every month. Overall it’s a smallish negative tax on the average person, I’d expect.

Here’s why HFT deserves some of our hatred: there’s way too much human resources going into this stuff and it’s embarrassing, what with the laying of cables and blasting through mountains and such. And it’s a great sociological look into the absolutely greed-led mindset of the Wall Street trader, but honestly I think we already had that. It’s really business as usual at a microscopic scale, and nobody should really be surprised to learn that people will do anything to make money that’s technically possible and technically legal, and that they will brag about how they’re making the world a better place while they do it. Same old same old.

So I’m not saying HFT is awesome and we should encourage more of it. I’m all for thinking about how to slow down trading to once a second and make it “more fair” for more players (although that’s hard to do even as a thought experiment), or taxing transaction to make things slow down by themselves, which would be easy.

But here’s the thing, it’s not some huge awful thing we should focus on, even though Michael Lewis is a really good and engaging writer.

You wanna focus on something? Let’s talk about money laundering in HSBC and now Citi that is not under control. Let’s talk about ongoing mortgage fraud and robo-signing and the ongoing bailout/ taxpayer subsidy and people still losing their homes, and the poor still being the targets of illegal and predatory loans, and Too-Big-To-Fail getting worse, and the direct line between the bailout and the broken pension promises for civil servants and the overall price list for fraud that has been built.

Let’s talk about the people who created the underlying fraud still at work in places like Bank of America, and how few masterminds have gone to jail and how the SEC and the Obama administration has made that happen through inaction and passivity and how Congress is sitting on its hands because of the money coming in from lobbyists. Let’s talk about the increasing distance between the justice system for the poor and the justice system for the rich in this country.

Tell me what I missed.

The HFT noise is misplaced and a distraction from the ongoing real story.

Lobbyists have another reason to dominate public commenting #OWS

Before I begin this morning’s rant, I need to mention that, as I’ve taken on a new job recently and I’m still trying to write a book, I’m expecting to not be able to blog as regularly as I have been. It pains me to say it but my posts will become more intermittent until this book is finished. I’ll miss you more than you’ll miss me!

On to today’s bullshit modeling idea, which was sent to me by both Linda Brown and Michael Crimmins. It’s a new model built in part by the former chief economist for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Andrei Kirilenko, who is now a finance professor at Sloan. In case you don’t know, the CFTC is the regulator in charge of futures and swaps.

I’ll excerpt this New York Times article which describes the model:

The algorithm, he says, uncovers key word clusters to measure “regulatory sentiment” as pro-regulation, anti-regulation or neutral, on a scale from -1 to +1, with zero being neutral.

If the number assigned to a final rule is different from the proposed one and closer to the number assigned to all the public comments, then it can be inferred that the agency has taken the public’s views into account, he says.

Some comments:

- I know really smart people that use similar sentiment algorithms on word clusters. I have no beef with the underlying NLP algorithm.

- What I do have a problem with is the apparent assumption that the “the number assigned to all the public comments” makes any sense, and in particular whether it takes into account “the public’s view”.

- It sounds like the algorithm dumps all the public comment letters into a pot and mixes it together to get an overall score. The problem with this is that the industry insiders and their lobbyists overwhelm public commenting systems.

- For example, go take a look at the list of public letters for the Volcker Rule. It’s not unlike this graphic on the meetings of the regulators on the Volcker Rule:

- Besides dominating the sheer number of letters, I’ll bet the length of each letter is also much longer on average for such parties with very fancy lawyers.

- Now think about how the NLP algorithm will deal with this in a big pot: it will be dominated by the language of the pro-industry insiders.

- Moreover, if such a model were to be directly used, say to check that public commenting letters were written in a given case, lobbyists would have even more reason to overwhelm public commenting systems.

The take-away is that this is an amazing example of a so-called objective mathematical model set up to legitimize the watering down of financial regulation by lobbyists.

Update: I’m willing to admit I might have spoken too soon. I look forward to reading the paper on this algorithm and taking a deeper look instead of relying on a newspaper.

Could we use eminent domain to help suffering homeowners? (#OWS)

Here are two things you might have some trouble believing if you read the papers regularly and find yourself convinced we are in a housing recovery. First, there are still huge numbers of homeowners on the brink of, or just starting to enter, foreclosure. Second, many of the banks foreclosing on those properties do not have clear legal ownership over the mortgages in question.

Obama should have addressed the first problem through TARP way back in 2008. In fact mortgage modification was an intention of TARP that was promised Congress when it passed the second half of the money but it never happened. Instead Obama came up with the garbage called HAMP, which has been dreadfully implemented and possibly a net harmful program.

Even without Obama, we should have seen a willingness to renegotiate debt. After all, we can negotiate credit card debt, and businesses routinely renegotiate their mortgages. Why are private home mortgages kept airtight? I guess the banks see it as in their interest not to allow negotiations, and whatever the banks want, the banks seem to get.

The second problem, which is essentially one of botched paperwork (explained here), is probably technically the job of some regulator to deal with, but nobody wants to “blow up the system” so nobody is dealing with it. This is especially ironic considering how often we hear about the so-called sanctity of the contract.

The result of these huge looming problems is that banks got bailed out and the system never got cleared of its actual debt and paperwork problems,.

Enter the concept of using eminent domain to force these two issues. Strike Debt, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, is pushing this in a few nationwide court cases, for example in Richmond, California.

More recently, and what inspired this post this morning, is a plan cooked up by Strike Debt using eminent domain to force courts to clear up broken chains of title, written by Hannah Appel and JP Massar.

This idea is on its face unappealing, given the history of that crude tool eminent domain. Everyone I meet has their own stories, but start here for a short list of eminent domain abuses.

And it might not work, either. A district judge might not want to deal with the complexity of the issue and might just let the bad paperwork through.

For that matter, many concerns have been voiced about the practicality of this approach, and one that deeply resonates with me is the idea of using it against current mortgages – i.e. mortgages where the homeowner is up-to-date with payment. Using eminent domain in such a case could set a precedent whereby, even though someone has been taking care of their property, the city uses eminent domain to condemn it based on historical data which implies the owner is likely to neglect their property. That would not be good enough. As far as I know the current plan only uses mortgages where there have been missed payments, though.

The bottomline is this: we’re in a situation where all these homeowners are being crushed with unreasonable monthly payments, and hugely inflated principals, where the legal ownership of the mortgage itself is under question, and nobody seems to want to do squat about it. Maybe it’s time a crude tool is used against a cruel enemy.

Gaming the (risk/legal) system

A while back I was talking to some math people about how credit default swaps (CDSs), by their very nature, contain risk that is generally speaking undetectable with standard risk models like Value-at-Risk (VaR).

It occurred to me then that I could put it another way: that perhaps credit default swaps might have been deliberately created by someone who knew all about the standard risk models to game the system. VaR was commercialized in the mid 1990’s and CDSs existed around the same time, but didn’t take off for a decade or so until after VaR became super widespread, which makes it hard to prove without knowing the actors.

For that matter it is reasonable to assume something less deliberate occurred: that a bunch of weird instruments were created and those which hid risk the most thrived, kind of an evolutionary approach to the same theory.

I was reminded recently of this conspiracy theory when Joe Burns talked to my Occupy group last Sunday about his recent book, Reviving the Strike. He talked about the history of strikes as a tool of leverage, and how much less frequently we’ve seen large-scale strikes and industry-wide strikes. He made the point that the legality of strikes has historically been uncorrelated to the existence of strikes – that strikers cannot necessarily wait for the legal system to catch up with the needs of the worker. Sometimes strikers need to exert pressure on legislation.

Anyhoo, one question that came up in Q&A was how, in this world of subsidiaries and franchises, can workers strike against the upper management with control over the actual big money? After all, McDonalds workers work for franchisees who are often not well-off. The real money lives in the mother company but is legally isolated from the franchises.

Similarly, with Walmart, there are massive numbers of workers that don’t work directly for Walmart but do work in the massive supply chain network set up and run by Walmart. They would like to hold Walmart responsible for their working conditions. How does that work?

It seems like the same VaR/CDS story as above. Namely, the legal structure of McDonalds and Walmart almost seems deliberately set up to avoid legal responsibility from disgruntled workers. So maybe first you had the legal system, then lawyers set up the legal construction of the supply chain and workers such that striking workers could only strike against powerless figures, especially in the McDonalds case (since Walmart has plenty of workers working for the mother company as well).

Last couple of points. First, only long-term, powerful enterprises can go to the trouble of gaming such large systems. It’s an artifact of the age of the corporation.

And finally, I feel like it’s hard to combat. We could try to improve our risk or legal system but that makes them – probably – even more complicated, which in turn gives massive corporations more ways to game them. Not to be a cynic, but I don’t see a solution besides somehow separately sidestepping our personal risk exposure to these problems.