The politics of data mining

At first glance, data miners inside governments, start-ups, corporations, and political campaigns are all doing basically the same thing. They’ll all need great engineering infrastructure, good clean data, a working knowledge of statistical techniques and enough domain knowledge to get things done.

We’ve seen recent articles that are evidence for this statement: Facebook data people move to the NSA or other government agencies easily, and Obama’s political campaign data miners have launched a new data mining start-up. I am a data miner myself, and I could honestly work at any of those places – my skills would translate, if not my personality.

I do think there are differences, though, and here I’m not talking about ethics or trust issues, I’m talking about pure politics[1].

Namely, the world of data mining is divided into two broad categories: people who want to cause things to happen and people who want to prevent things from happening.

I know that sounds incredibly vague, so let me give some examples.

In start-ups, irrespective of what you’re actually doing (what you’re actually doing is probably incredibly banal, like getting people to click on ads), you feel like you’re the first person ever to do it, at least on this scale, or at least with this dataset, and that makes it technically challenging and exciting.

Or, even if you’re not the first, at least what you’re creating or building is state-of-the-art and is going to be used to “disrupt” or destroy lagging competition. You feel like a motherfucker, and it feels great[2]!

The same thing can be said for Obama’s political data miners: if you read this article, you’ll know they felt like they’d invented a new field of data mining, and a cult along with it, and it felt great! And although it’s probably not true that they did something all that impressive technically, in any case they did a great job of applying known techniques to a different data set, and they got lots of people to allow access to their private information based on their trust of Obama, and they mined the fuck out of it to persuade people to go out and vote and to go out and vote for Obama.

Now let’s talk about corporations. I’ve worked in enough companies to know that “covering your ass” is a real thing, and can overwhelm a given company’s other goals. And the larger the company, the more the fear sets in and the more time is spent covering one’s ass and less time is spent inventing and staying state-of-the-art. If you’ve ever worked in a place where it takes months just to integrate two different versions of SalesForce you know what I mean.

Those corporate people have data miners too, and in the best case they are somewhat protected from the conservative, risk averse, cover-your-ass atmosphere, but mostly they’re not. So if you work for a pharmaceutical company, you might spend your time figuring out how to draw up the numbers to make them look good for the CEO so he doesn’t get axed.

In other words, you spend your time preventing something from happening rather than causing something to happen.

Finally, let’s talk about government data miners. If there’s one thing I learned when I went to the State Department Tech@State “Moneyball Diplomacy” conference a few weeks back, it’s that they are the most conservative of all. They spend their time worrying about a terrorist attack and how to prevent it. It’s all about preventing bad things from happening, and that makes for an atmosphere where causing good things to happen takes a rear seat.

I’m not saying anything really new here; I think this stuff is pretty uncontroversial. Maybe people would quibble over when a start-up becomes a corporation (my answer: mostly they never do, but certainly by the time of an IPO they’ve already done it). Also, of course, there are ass-coverers in start-ups and there are risk-takers in corporation and maybe even in government, but they don’t dominate.

If you think through things in this light, it makes sense that Obama’s data miners didn’t want to stay in government and decided to go work on advertising stuff. And although they might have enough clout and buzz to get hired by a big corporation, I think they’ll find it pretty frustrating to be dealing with the cover-my-ass types that will hire them. It also makes sense that Facebook, which spends its time making sure no other social network grows enough to compete with it, works so well with the NSA.

1. If you want to talk ethics, though, join me on Monday at Suresh Naidu’s Data Skeptics Meetup where he’ll be talking about Political Uses and Abuses of Data.

Occupy Wonder!

Now that summer is here, it’s time to unschool ourselves.

At the beginning of every school year, I ask my students to consider the question, “What is the purpose of education?” Most students understand from experience that schooling is at least in part an exercise in obedience to authority, in conformity to expectations, in bureaucracy, in knowing your place in the social and academic hierarchy. As one astute 14-year-old put it bluntly, “We’re here to be ranked and sorted.”

I shudder at the thought that my role as a teacher is to sort the winners from the losers. Like most educators, I’m aiming for a loftier mission: to unleash the curiosity and capacity for wonder that are inborn in each of us. Ironically, that mission might be best accomplished in the summer time, in the context of leisure, when the mind is at rest and at play, free from the strictures and dictates of institutional schooling.

At the end of every school year, I ask my students, “What will you think about when you are not being told what to think about? Are you prepared to trade the comforts of intellectual obedience for the risks of intellectual independence? How will you pursue your curiosities? What sets you on fire intellectually, and how will you fan those flames? What will you write feverishly in your Book of Questions?” These are the same questions we must ask ourselves as educators, as people modeling intellectual engagement, as propagandists for the Life of the Mind.

What ignites my curiosity, reliably, is insects. I just got my hands on a compound stereoscope and some live stick insects and I have the whole summer ahead of me.

What ignites your curiosity?

A girl considers insects under a microscope at the new Gallery of Natural Sciences at the Oakland Museum of California. Photo by Becky Jaffe

“The cure for boredom is curiosity. There is no cure for curiosity.” – Dorothy Parker

I am the bus queen of Stockholm

Do you know what I really love? Maps. All kinds of maps. If you come to my house, you won’t see standard artwork on the walls, but instead you’ll see: knitting, hanging musical instruments, and maps.

In my kitchen I have a huge map of New York City, which I purchased from Staples for $99 when I moved to the city in 2005, as well as a large subway map, and more recently a bike map. I’ve got New York covered.

And whenever I go to a new city, I enjoy staring at a good map for a few hours, figuring out how to get from place to place by walking or taking a subway or bus. I’m never interested in driving, because I don’t own a car nor do I enjoy riding cabs.

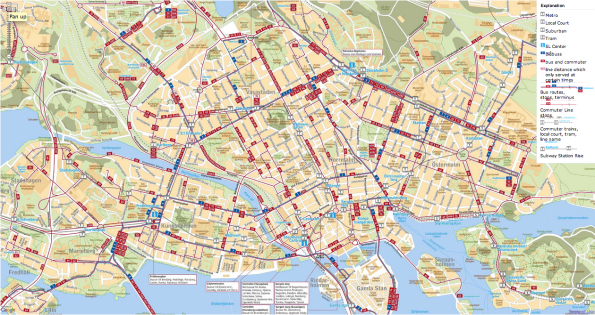

Here’s the map of Stockholm I’ve been staring at for the past few weeks:

It’s a bus map of Stockholm. We smartly bought 7-day passes our first day here, and since kids 12 and younger are free and 13-year-olds are subsidized, this has been a huge win. We’ve been whizzing around the city daily. Buses are really the way to go.

Now, if you’re from certain American cities, you might disagree. You might think buses are slow and painful. But not here! They come every few minutes, more often than subways, and they seem to magically glide from stop to stop (the stops are more infrequent here than in New York, one reason they’re much more efficient). It’s like an unguided tour every time you go anywhere, my favorite kind!

I’ve gotten so excited about (and so proficient at) getting from point A to point B on the bus system, I’ve taken to calling myself the “Bus Queen (of Stockholm),” with practically no self-consciousness whatsoever, even though everyone here speaks perfect English and can hear me brag incessantly to my kids (to their credit, the older ones roll their eyes appropriately).

My four-year-old, who thinks everything I say is true, has asked his older brother to build a Minecraft World called “Bus Queen” in honor of my title, which he has done. As I understand it, the Minecraft villagers internal to Bus Queen World are just about done erecting a Town Hall in my honor. I go!!

One of the great boons of the bus system here in Stockholm is that, unlike Citibikes in New York, you can take a sick and drugged-up 4-year-old on the bus and go places you otherwise wouldn’t be able to walk to. This has been pretty convenient for all of us, believe you me.

But here’s the sad part: there’s a bus strike today in Stockholm and a few other Swedish cities. The bus queen, sadly, may have no throne on which to sit on this, her last day of reign (because we’re coming home tomorrow).

This strike makes me realize something about workers’ conditions in the U.S. which I haven’t thought about since the 2005 New York transit workers’ strike. Namely, Americans don’t have a lot of sympathy for striking workers compared to Europeans. Partly this is because we Americans prize convenience over other people’s conditions (“Can the bus drivers please return to work until after I’ve left Stockholm? The Bus Queen beseeches you!”), and partly this is due, I’m guessing, to the fact that there’s so much income disparity in the U.S. that there’s always some other group of workers worse off than the people striking.

Why Education Isn’t Like Sports

This is a guest post by Eugene Stern.

Sometimes you learn just as much from a bad analogy as from a good one. At least you learn what people are thinking.

The other day I read this response to this NYT article. The original article asked whether the Common Core-based school reforms now being put in place in most states are really a good idea. The blog post criticized the article for failing to break out four separate elements of the reforms: standards (the Core), curriculum (what’s actually taught), assessment (testing), and accountability (evaluating how kids and educators did). If you have an issue with the reforms, you’re supposed to say exactly which aspect you have an issue with.

But then, at the end of the blog post, we get this:

A track and field metaphor might help: The standard is the bar that students must jump over to be competitive. The curriculum is the training program coaches use to help students get over the bar. The assessment is the track meet where we find out how high everyone can jump. And the accountability system is what follows after its all over and we want to figure out what went right, what went wrong, and what it will take to help kids jump higher.

Really?

In track, jumping over the bar is the entire point. You’re successful if you clear the bar, you’ve failed if you don’t. There are no other goals in play. So the standard, the curriculum, and the assessment might be nominally different, but they’re completely interdependent. The standard is defined in terms of the assessment, and the only curriculum that makes sense is training for the assessment.

Education has a lot more to it. The Common Core is a standard covering two academic dimensions: math and English/language arts/literacy. But we also want our kids learning science, and history, and music, and foreign languages, and technology, as well as developing along non-academic dimensions: physically, socially, morally, etc. (If a school graduated a bunch of high academic achievers that couldn’t function in society, or all ended up in jail for insider trading, we probably wouldn’t call that school successful.)

In Cathy’s terminology from this blog post, the Common Core is a proxy for the sum total of what we care about, or even just for the academic component of what we care about.

Then there’s a second level of proxying when we go from the standard to the assessment. The Common Core requirements are written to require general understanding (for example: kindergarteners should understand the relationship between numbers and quantities and connect counting to cardinality). A test that tries to measure that understanding can only proxy it imperfectly, in terms of a few specific questions.

Think that’s obvious? Great! But hang on just a minute.

The real trouble with the sports analogy comes when we get to the accountability step and forget all the proxying we did. “After it’s all over and we want to figure out what went right (and) what went wrong,” we measure right and wrong in terms of the assessment (the test). In sports, where the whole point is to do well on the assessment, it may make sense to change coaches if the team isn’t winning. But when we deny tenure to or fire teachers whose students didn’t do well enough on standardized tests (already in place in New York, now proposed for New Jersey as well), we’re treating the test as the whole point, rather than a proxy of a proxy. That incentivizes schools to narrow the curriculum to what’s included in the standard, and to teach to the test.

We may think it’s obvious that sports and education are different, but the decisions we’re making as a society don’t actually distinguish them.

Swedish vacation

Dear Readers,

I hope you know I miss you as much as you miss me.

For the past few days I’ve been in sunny friendly Stockholm. In my defense, I’m suffering badly from jetlag. Since I left New York last Thursday I’ve had one good night’s sleep and about 3 naps. My youngest son has an ear infection which is making him miserable, and so I’m kind of stuck at home with the kids while Johan temporarily works at the nearby KTH math department.

But honestly, traveling, even with kids, and even with jetlag, is no excuse to take off so much time from blogging. I didn’t even announce beforehand I’d be going away because I’d planned to blog every day anyway.

Here’s my confession: the real reason I haven’t blogged is because I’ve fallen into a Northern European funk.

Let me explain. Being here in gorgeous sunny Stockholm is kind of like lying back in a cloud. It’s so soft, so bereft of the natural tension and energy of New York, that you just feel like knitting all day and drinking coffee. And then, when you can’t sleep and it’s still light out at midnight, you feel like knitting some more. I’m almost done with a sweater I didn’t even have the yarn for until Saturday.

Not that I’m complaining, exactly – the Swedish people I’ve met are incredibly nice. So nice in fact that it’s almost become a personal challenge I’ve given myself to see what makes them tick.

For example, they don’t seem to value their time like we do in New York. There are lines for everything here, and although I can appreciate an organized line myself now and again, this is a different matter – it’s kind of a national pasttime.

For example, to gain entrance to an amusement park yesterday, my sons and I stood in line for 30 minutes. Then we tried to get onto some rides, but it turns out you have to stand in a second, separate line inside the park for another 30 minutes to buy tickets for the rides. Woohoo! Another line! I seemed to be the only person in line who was crazed by the system.

When I finally got to the ticket window and confronted the ticket seller in my polite-but-impatient New York way, he explained that it was the same system that the park had opened with back in 1830 or something. Naturally I felt incredibly honored to be taking part in such a hallowed ritual, as I explained to him.

Let’s talk Star Trek comparisons for a moment. There’s a spectrum of represented civilizations, from oppressed penal colonies on the one hand, where everyone’s dirty and wearing rags, but even so there’s always a shockingly articulate and thoughtful representatives, to ideal utopias on the other, where everyone’s incredibly fit and beautiful, bounding about without a care in the world (although often also hiding a dark secret – perhaps they sap the life energy from a slave race hidden underground?).

I’d have to put Stockholm and its ridiculously gorgeous citizenry firmly on the utopia end of the Star Trek spectrum, with a few inconsistent details, namely that, unlike in Star Trek, they still exchange money (although not for their high quality medical care) and that, despite their utopian existence, they don’t seem to have the requisite dirty secret. Of course I say that while temporarily residing in the Upper West Side equivalent of Stockholm, and not as an unemployed immigrant youth in the suburbs.

In any case, I’m coming back in a few days, and I’m looking forward to the friction, the hot grimy subway cars, and of course the beloved controversy over citibikes. Aunt Pythia, who missed her column this past Saturday, is also chomping at the bit (with some help from guest advice columnist Cousin Lily!), so stay tuned for that too.

XOXOX,

Cathy

Guest post, The Vortex: A Cookie Swapping Game for Anti-Surveillance

This is a guest post by Rachel Law, a conceptual artist, designer and programmer living in Brooklyn, New York. She recently graduated from Parsons MFA Design&Technology. Her practice is centered around social myths and how technology facilitates the creation of new communities. Currently she is writing a book with McKenzie Wark called W.A.N.T, about new ways of analyzing networks and debunking ‘mapping’.

Let’s start with a timely question. How would you like to be able to change how you are identified by online networks? We’ll talk more about how you’re currently identified below, but for now just imagine having control over that process for once – how would that feel? Vortex is something I’ve invented that will try to make that happen.

Namely, Vortex is a data management game that allows players to swap cookies, change IPs and disguise their locations. Through play, individuals experience how their browser changes in real time when different cookies are equipped. Vortex is a proof of concept that illustrates how network collisions in gameplay expose contours of a network determined by consumer behavior.

What happens when users are allowed to swap cookies?

These cookies, placed by marketers to track behavioral patterns, are stored on our personal devices from mobile phones to laptops to tablets, as a symbolic and data-driven signifier of who we are. In other words, to the eyes of the database, the cookies are us. They are our identities, controlling the way we use, browse and experience the web. Depending on cookie type, they might follow us across multiple websites, save entire histories about how we navigate and look at things and pass this information to companies while still living inside our devices.

If we have the ability to swap cookies, the debate on privacy shifts from relying on corporations to follow regulations to empowering users by giving them the opportunity to manage how they want to be perceived by the network.

What are cookies?

The corporate technological ability to track customers and piece together entire personal histories is a recent development. While there are several ways of doing so, the most common and prevalent method is with HTTP cookies. Invented in 1994 by a computer programmer, Lou Montulli, HTTP cookies were originally created with the shopping cart system as a way for the computer to store the current state of the session, i.e. how many items existed in the cart without overloading the company’s server. These session histories were saved inside each user’s computer or individual device, where companies accessed and updated consumer history constantly as a form of ‘internet history’. Information such as where you clicked, how to you clicked, what you clicked first, your general purchasing history and preferences were all saved in your browsing history and accessed by companies through cookies.

Cookies were originally implemented to the general public without their knowledge until the Financial Times published an article about how they were made and utilized on websites without user knowledge on February 12th, 1996 . This revelation led to a public outcry over privacy issues, especially since data was being gathered without the knowledge or consent of users. In addition, corporations had access to information stored on personal computers as the cookie sessions were stored on your computer and not their servers.

At the center of the debate was the issue on third-party cookies, also known as “persistent” or “tracking” cookies. When you are browsing a webpage, there may be components on the page that are hosted on the same server, but different domain. These external objects then pass cookies to you if you click an image, link or article. They are then used by advertising and media mining corporations to track users across multiple sites to garner more knowledge about the users browsing patterns to create more specific and targeted advertising.

In August 2013, Wall Street Journal ran an article on how Mac users were being unfairly targeted by travel site Orbitz with advertisements that were 13% more expensive than PC users. New York Times followed it up with a similar article in November 2012 about how the data collected and re-sold to advertisers. These advertisers would analyze users buying habits to create micro-categories where the personal experiences were tailored to maximize potential profits.

What does that mean for us?

The current state of today’s internet is no longer the same as the carefree 90s of ‘internet democracy’ and utopian ‘cyberspace’. Mediamining exploits invasive technologies such as IP tracking, geolocating and cookies to create specific advertisements targeted to individuals. Browsing is now determined by your consumer profile what you see, hear and the feeds you receive are tailored from your friends’ lists, emails, online purchases etc. The ‘Internet’ does not exist. Instead, it is many overlapping filter bubbles which selectively curate us into data objects to be consumed and purchased by advertisers.

This information, though anonymous, is built up over time and used to track and trace an individual’s history – sometimes spanning an entire lifetime. Who you are, and your real name is irrelevant in the overall scale of collected data, depersonalizing and dehumanizing you into nothing but a list of numbers on a spreadsheet.

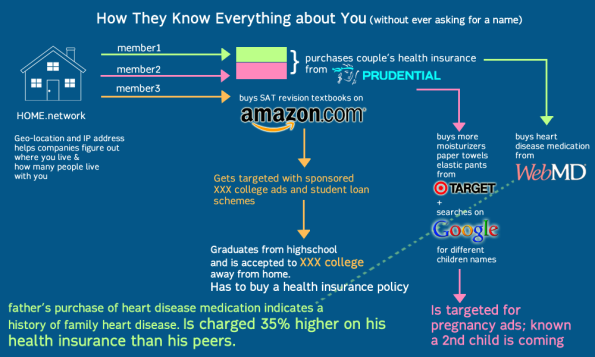

The superstore Target, provides a useful case study for data profiling in its use of statisticians on their marketing teams. In 2002, Target realized that when a couple is expecting a child, the way they shop and purchase products changes. But they needed a tool to be able to see and take advantage of the pattern. As such, they asked mathematicians to come up with algorithms to identify behavioral patterns that would indicate a newly expectant mother and push direct marketing materials their way. In a public relations fiasco, Target had sent maternity and infant care advertisements to a household, inadvertedly revealing that their teenage daughter was pregnant before she told her parents .

This build-up of information creates a ‘database of ruin’, enough information that marketers and advertisers know more about your life and predictive patterns than any single entity. Databases that can predict whether you’re expecting, or when you’ve moved, or what stage of your life or income level you’re at… information that you have no control over where it goes to, who is reading it or how it is being used. More importantly, these databases have collected enough information that they know secrets such as family history of illness, criminal or drug records or other private information that could potentially cause harm upon the individual data point if released – without ever needing to know his or her name.

What happens now is two terrifying possibilities:

- Corporate databases with information about you, your family and friends that you have zero control over, including sensitive information such as health, criminal/drug records etc. that are bought and re-sold to other companies for profit maximization.

- New forms of discrimination where your buying/consumer habits determine which level of internet you can access, or what kind of internet you can experience. This discrimination is so insidious because it happens on a user account level which you cannot see unless you have access to other people’s accounts.

Here’s a visual describing this process:

What can Vortex do, and where can I download a copy?

As Vortex lives on the browser, it can manage both pseudo-identities (invented) as well as ‘real’ identities shared with you by other users. These identity profiles are created through mining websites for cookies, swapping them with friends as well as arranging and re-arranging them to create new experiences. By swapping identities, you are essentially ‘disguised’ as someone else – the network or website will not be able to recognize you. The idea is that being completely anonymous is difficult, but being someone else and hiding with misinformation is easy.

This does not mean a death knell for online shopping or e-commerce industries. For instance, if a user decides to go shoe-shopping for summer, he/she could equip their browser with the cookies most associated and aligned with shopping, shoes and summer. Targeted advertising becomes a targeted choice for both advertisers and users. Advertisers will not have to worry about misinterpreting or mis-targeting inappropriate advertisements i.e. showing tampon advertisements to a boyfriend who happened to borrow his girlfriend’s laptop; and at the same time users can choose what kind of advertisements they want to see. (i.e. Summer is coming, maybe it’s time to load up all those cookies linked to shoes and summer and beaches and see what websites have to offer; or disable cookies it completely if you hate summer apparel.)

Currently the game is a working prototype/demo. The code is licensed under creative commons and will be available on GitHub by the end of summer. I am trying to get funding to make it free, safe & easy to use; but right now I’m broke from grad school and a proper back-end to be built for creating accounts that is safe and cannot be intercepted. If you have any questions on technical specs or interest in collaborating to make it happen – particularly looking for people versed in python/mongodb, please email me: Rachel@milkred.net.

Crash the pick-up party with me?

I’m not sure my friend Jason Windawi will appreciate the credit, but he pointed me to this Meetup yesterday called “MEN THAT DATE HOT WOMEN”, which I have conveniently screen-shotted for y’all:

I’m not sure where to start with deconstructing this pick-up-artist wannabe clan, but let’s just START WITH THE ALL CAPS. Who does that? Update: turns out THE NAVY DOES THAT.

I’m thinking of crashing this Meetup with a posse of sufficiently ridiculous and hilarious friends.

First the good news: I can easily imagine what kind of person I’d love to attract for this action (namely, anyone who thinks this is ludicrous, in a fun way, and wants to join me) but, and here’s the other good news, I’m having trouble figuring out the perfect thing to do once we get there. Let’s think.

First thought: line dance with boas, singing “I will survive.” Maybe not that exactly, but something to intentionally and directly contrast the oppressively normative nature of a bunch of straight guys looking for “hot” women using a formulaic approach involving magic tricks. Bonus points, obviously, for ill-fitting cocktail dresses that emphasize jiggling flesh.

In other words, let’s take a page out of this book, one of my all-time favorite Occupy actions:

Other ideas welcome!

Where’s the outrage over private snooping?

There’s been a tremendous amount of hubbub recently surrounding the data collection data mining that the NSA has been discovered to be doing.

For me what’s weird is that so many people are up in arms about what our government knows about us but not, seemingly, about what private companies know about us.

I’m not suggesting that we should be sanguine about the NSA program – it’s outrageous, and it’s outrageous that we didn’t know about it. I’m glad it’s come out into the open and I’m glad it’s spawned an immediate and public debate about the citizen’s rights to privacy. I just wish that debate extended to privacy in general, and not just the right to be anonymous with respect to the government.

What gets to me are the countless articles that make a big deal of Facebook or Google sharing private information directly with the government, while never mentioning that Acxiom buys and sells from Facebook on a daily basis much more specific and potentially damning information about people (most people in this country) than the metadata that the government purports to have.

Of course, we really don’t have any idea what the government has or doesn’t have. Let’s assume they are also an Acxiom customer, for that matter, which stands to reason.

It begs the question, at least to me, of why we distrust the government with our private data but we trust private companies with our private data. I have a few theories, tell me if you agree.

Theory 1: people think about worst case scenarios, not probabilities

When the government is spying on you, worst case you get thrown into jail or Guantanamo Bay for no good reason, left to rot. That’s horrific but not, for the average person, very likely (although, of course, a world where that does become likely is exactly what we want to prevent by having some concept of privacy).

When private companies are spying on you, they don’t have the power to put you in jail. They do increasingly have the power, however, to deny you a job, a student loan, a mortgage, and life insurance. And, depending on who you are, those things are actually pretty likely.

Theory 2: people think private companies are only after our money

Private companies who hold our private data are only profit-seeking, so the worst thing they can do is try to get us to buy something, right? I don’t think so, as I pointed out above. But maybe people think so in general, and that’s why we’re not outraged about how our personal data and profiles are used all the time on the web.

Theory 3: people are more afraid of our rights being taken away than good things not happening to them

As my friend Suresh pointed out to me when I discussed this with him, people hold on to what they have (constitutional rights) and they fear those things being taken away (by the government). They spend less time worrying about what they don’t have (a house) and how they might be prevented from getting it (by having a bad e-score).

So even though private snooping can (and increasingly does) close all sorts of options for peoples’ lives, if they don’t think about them, they don’t notice. It’s hard to know why you get denied a job, especially if you’ve been getting worse and worse credit card terms and conditions over the years. In general it’s hard to notice when things don’t happen.

Theory 4: people think the government protects them from bad things, but who’s going to protect them from the government?

This I totally get, but the fact is the U.S. government isn’t protecting us from data collectors, and has even recently gotten together with Facebook and Google to prevent the European Union from enacting pretty good privacy laws. Let’s not hold our breath for them to understand what’s at stake here.

(Updated) Theory 5: people think they can opt out of private snooping but can’t opt out of being a citizen

Two things. First, can you really opt out? You can clear your cookies and not be on gmail and not go on Facebook and Acxiom will still track you. Believe it.

Second, I’m actually not worried about you (you reader of mathbabe) or myself for that matter. I’m not getting denied a mortgage any time soon. It’s the people who don’t know to protect themselves, don’t know to opt out, that I’m worried about and who will get down-scored and funneled into bad options that I worry about.

Theory 5 6: people just haven’t thought about it enough to get pissed

This is the one I’m hoping for.

I’d love to see this conversation expand to include privacy in general. What’s so bad about asking for data about ourselves to be automatically forgotten, say by Verizon, if we’ve paid our bills and 6 months have gone by? What’s so bad about asking for any personal information about us to have a similar time limit? I for one do not wish mistakes my children make when they’re impetuous teenagers to haunt them when they’re trying to start a family.

Knowing the Pythagorean Theorem

This guest post is by Sue VanHattum, who blogs at Math Mama Writes. She teaches math at Contra Costa College, a community college in the Bay Area, and is working on a book titled Playing With Math: Stories from Math Circles, Homeschoolers, and Passionate Teachers, which will be published soon.

Here’s the Pythagorean Theorem:

In a right triangle, where the lengths of the legs are given by

and

, and the length of the hypotenuse is given by

, we have

Do you remember when you first learned about it? Do you remember when you first proved it?

I have no idea when or where I first saw it. It feels like something I’ve always ‘known’. I put known in quotes because in math we prove things, and I used the Pythagoeran Theorem for way too many years, as a student and as a math teacher, before I ever thought about proving it. (It’s certainly possible I worked through a proof in my high school geometry class, but my memory kind of sucks and I have no memory of it.)

It’s used in beginning algebra classes as part of terrible ‘pseudo-problems’ like this:

Two cars start from the same intersection with one traveling southbound while the other travels eastbound going 10 mph faster. If after two hours they are 10 times the square root of 24 [miles] apart, how fast was each car traveling?

After years of working through these problems with students, I finally realized I’d never shown them a proof (this seems terribly wrong to me now). I tried to prove it, and didn’t really have any idea how to get started.

This was 10 to 15 years ago, before Google became a verb, so I searched for it in a book. I eventually found it in a high school geometry textbook. Luckily it showed a visually simple proof that stuck with me. There are hundreds of proofs, many of them hard to follow.

There is something wrong with an education system that teaches us ‘facts’ like this one and knocks the desire for deep understanding out of us. Pam Sorooshian, an unschooling advocate, said in a talk to other unschooling parents:

Relax and let them develop conceptual understanding slowly, over time. Don’t encourage them to memorize anything – the problem is that once people memorize a technique or a ‘fact’, they have the feeling that they ‘know it’ and they stop questioning it or wondering about it. Learning is stunted.

She sure got my number! I thought I knew it for all those years, and it took me decades to realize that I didn’t really know it. This is especially ironic – the reason it bears Pythagoras’ name is because the Pythagoreans were the first to prove it (that we know of).

It had been used long before Pythagoras and the Greeks – most famously by the Egyptians. Egyptian ‘rope-pullers’ surveyed the land and helped build the pyramids, using a taut circle of rope with 12 equally-spaced knots to create a 3-4-5 triangle: since this is a right triangle, giving them the right angle that’s so important for building and surveying.

Ever since the Greeks, proof has been the basis of all mathematics. To do math without understanding why something is true really makes no sense.

Nowadays I feel that one of my main jobs as a math teacher is to get students to wonder and to question. But my own math education left me with lots of ‘knowledge’ that has nothing to do with true understanding. (I wonder what else I have yet to question…) And beginning algebra students are still using textbooks that ‘give’ the Pythagorean Theorem with no justification. No wonder my Calc II students last year didn’t know the difference between an example and a proof.

Just this morning I came across an even simpler proof of the Pythagorean Theorem than the one I have liked best over the past 10 to 15 years. I was amazed that I hadn’t seen it before. Well, perhaps I had seen it but never took it in before, not being ready to appreciate it. I’ll talk about it below.

My old favorite goes like this:

- Draw a square.

- Put a dot on one side (not at the middle).

- Put dots at the same place on each of the other 3 sides.

- Connect them.

- You now have a tilted square inside the bigger square, along with 4 triangles. At this point, you can proceed algebraically or visually.

Algebraic version:

- big square = small tilted square + 4 triangles

Visual version:

- Move the triangles around.

- What was

is now

- Also check out Vi Hart’s video showing a paper-folding proof (with a bit of ripping). It’s pretty similar to this one.

To me, that seemed as simple as it gets. Until I saw this:

This is an even more visual proof, although it might take a few geometric remarks to make it clear. In any right triangle, the two acute (less than 90 degrees) angles add up to 90 degrees. Is that enough to see that the original triangle, triangle A, and triangle B are all similar? (Similar means they have exactly the same shape, though they may be different sizes.) Which makes the ‘houses with asymmetrical roofs’ also all similar. Since the big ‘house’ has an ‘attic’ equal in size to the two other ‘attics’, its ‘room’ must also be equal in area to the two other ‘rooms’. Wow! (I got this language from Alexander Bogomolny’s blog post about it, which also tells a story about young Einstein discovering this proof.

Since all three houses are similar (exact same shape, different sizes), the size of the room is some given multiple of the size of the attic. More properly, area(square) = area(triangle), where

is the same for all three figures. The square attached to triangle

(whose area we will say is also

) has area

, similarly for the square attached to triangle

. But note that

which is the area of the square attached to the triangle labeled

. But

, and

, so

and it also equals

giving us what we sought:

I stumbled on the article in which this appeared (The Step to Rationality, by R. N. Shepard) while trying to find an answer to a question I have about centroids. I haven’t answered my centroid question yet, but I sure was sending out some google love when I found this.

What I love about this proof is that the triangle stay central in our thoughts throughout, and the focus stays on area, which is what this is really about. It’s all about self-similarity, and that’s what makes it so beautiful.

I think that, even though this proof is simpler in terms of steps than my old favorite, it’s a bit harder to see conceptually. So I may stick with the first one when explaining to students. What do you think?

Profit as proxy for value

I enjoyed my discussion with Doug Henwood yesterday at the Left Forum moderated by Suresh Naidu.

At the very end Doug defined capitalism pretty much like this wikipedia article:

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production, with the goal of making a profit.

Doug went on to make the point that, as a society, we might decide to replace our general pursuit of profit by a pursuit of improving our collective quality of life.

It occurred to me that Doug had identified a proxy problem much like I talked about in a recent post called How Proxies Fail. The general history of failed proxies I outlined goes like this:

- We’d like to measure something

- We can’t measure it directly so let’s come up with a proxy

- We’re aware of the problems at first

- We start to use it and it works pretty well

- We slowly forget the problems we had understood, and at the same time

- People start gaming the proxy in various ways and it loses its connection with the original object of interest.

In this example, the thing we’re trying to measure is something along the lines of “human value,” although we’d probably also want to consider value to the rest of mother nature as well. For context, we were discussing the financial system – what the purported function of the financial system is and what monstrous proportions it has taken on due to the brutal pursuit of profits over goals we might consider reasonable and useful to society.

So the proxy for value is profit. And of course we measure profit in money.

Going back to my history of proxies, it’s been a long time ago since the discussion of “whether money is a good proxy for value” was started, and a large part of economic theory, I guess, is devoted to considering the extent to which this proxy fails. I say “I guess” because I’m no economist, but I am aware of the economic concept of externality, which grapples with this discrepancy between money paid or earned, and to whom, versus actual harm or benefit, and to whom.

It could be argued that the concept and industry of regulation has been erected to deal with externalities of our profit proxy: when a chemical company pollutes the water, causing harm to nearby nature and people, regulators step in, sometimes (and sometimes people sue, of course, but most of the time they’re not even aware of the value being extracted from them, or are helpless to confront it adequately).

This is obviously more than an academic or regulatory topic: it pervades our collective lives. When an individual loses sight of the failures of the profit proxy, they value themselves or others in terms of how much money they have or the rate at which they get paid. They infer that if someone is highly paid or rich, they must be valuable. If someone’s poor, they must hold no value. There are a lot of people like this, I’m sure you’ve met them.

And that brings us to the part of the history of a failed proxy, which is that people game the proxy. We’ve seen this happen a lot lately, especially in finance and technology. And if you think about it, it’s no surprise since so much money goes through the financial system, and the financial system is now entirely technologically driven, and the systems are so complex that the regulators can’t keep up with the manufactured externalities. Someone could probably write a book reframing large parts of the financial system as purely devoted to exploiting the difference between value and money.

I don’t think I’ll start coming to different conclusions now that I have this framework to think through, but I do think it will be easier for me to spot instances of the “profit proxy failure” when I come across them. It’s especially timely for me to be thoughtful about this kind of thing, since I’m hoping to create something valuable, rather than merely profitable. I don’t want to avoid profit, obviously, but I don’t want to measure my progress with the wrong stick.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is psyched to be able to answer your questions and dispense (self-described) invaluable advice today as always.

If you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I already have great sex with my hot bearded husband, and I’ve been on hormonal birth control pills for years. So how amazing will it be if I switch to a non-hormonal copper IUD, if Obamacare makes my insurance cover it now? Please be specific. I am weighing my options.

Thank you!

Considering a Change

Dear CAC,

I love that you mentioned your husband’s beard. I needed to know that.

How amazing will it be? I’m guessing somewhat more amazing than it already is.

But I’m not sure, because I have a feeling every woman’s body responds differently to being on the pill. I’m a woman who naturally has a lot of testosterone, among other things, and so it throws me totally out of whack. For you it might not, although I’m guessing it does but just less so.

Also, I’ve been on the copper IUD, and when they say you bleed more on that, they aint lyin. But that problem doesn’t start for a few years.

Kind of annoying that the most obvious choices are so hard on a woman’s, body, isn’t it?

If you’re avoiding pregnancy but it wouldn’t be the end of the world, let me recommend spermicidal inserts, although you really do need to follow the instructions whereby you wait 10 minutes after insertion before any sperm enters (many women would consider this a feature, not a bug).

They obviously don’t protect you from STD’s or anything, though, so I suggest you go with spermicidal inserts for your hot bearded (bearded!) husband and condoms with anyone else.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Two questions. I googled “talk to a mathematician” because I wanted to see if anyone had an idea how I could split a league of 10 soccer teams into two groups, in order to minimise travel (well, its a bit more complex than that, but that’s sorta the gist).

But then I read your page, and of course the Sex questions, and a far more interesting one came to mind. So you said “Just to be clear, it is possible to see real female orgasms but you have to look for them, and they aren’t really considered mainstream porn.” And my question is, “Where?”

Love,

CurvePurve

Dear CurvePurve,

First the soccer question: I’d say cluster by geographic area, so nobody has to drive very far, but as you said it’s more complicated so I don’t have enough information to answer it. Even so, I’m going to take this moment to point out that the amount of traveling my friends do for their daughters’ soccer teams is super insane. They pretty much don’t have a life because of how much driving they do, even the ones who live in Manhattan. WTF?!

As for the second question, maybe try this.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Okay, I’ll bite. Why do men and women report differing numbers of sexual partners? I imagine it’s partially due to social expectations.

But I did have this conversation with my partner, and I found out we defined “sex” differently – I said oral counted, she did not (I guess this could be a reflection of social pressures as well). Is that issue of differing definitions sufficient to explain the different numbers?

More generally, how do the curves compare between men and women for number of partners?

OK I’ll Bite

p.s. I promise to ask a more interesting sex question next time.

Dear OK,

I chose your question out of the remarkable collection of people doing as I asked last week and asking me this same question (thank you everyone!) because you promised to follow up with another sex question. I totally cannot hold you to that promise, since I don’t collect email addresses or anything, but I figure by putting it in italics it’s as good as a blood pledge.

It also inspires me to appeal to my readers more generally, since last week worked so well: please follow up with another, more interesting sex question next week, thanks!

On to your question. I love what you pointed out, that the different definitions of sex come into play. And I think that makes a lot of sense, especially the example you gave of oral sex.

Because why?

Because, as I think you’ll agree, when “oral sex” occurs, it’s often only the guy getting it! And then in what sense has the woman really had sex? Unless she’s Monica Lewinsky (one of my heros), there’s really nothing much there there. Which is why it totally makes sense that she wouldn’t “count” it.

Now, going back to the discrepancy.

Let’s just agree, once and for all, that if you actually got a good sample of all (straight) men and all (straight) women, meaning you got some normal men and a few slutty men, in proportion to the population at large, and if you got normal women and slutty women, again in proportion to the population at large, then the average number of sexual partners would have to be equal. It’s just a statistical truth.

One caveat: if we all had a bunch of sex, and then there was some war or illness that only affected men, and for whatever reason only affected slutty men, then we’d get a bias if we did the poll after all the slutty men died. But I don’t think that issue is in play here, and so we can’t explain the discrepancy in any way except that woman and/or men are lying about the number of people they’ve slept with.

Reader Artem commented last week with a link to a nifty article explaining this, called Men and women lie about sex to match gender expectations. The study is published here (thanks, other anonymous reader!).

From the article:

But when it came to sex, men wanted to be seen as “real men:” the kind who had many partners and a lot of sexual experience. Women, on the other hand, wanted to be seen as having less sexual experience than they actually had, to match what is expected of women.

Well, that’s the interpretation anyway. In any case they saw big discrepancies between men and women’s reported sexual experience, although these are college kids so nobody seemed to have much. Next they hooked people up to lie-detector tests and they changed their tune. This had been done before:

Back in 2003, women went from having fewer sexual partners than men (when not hooked up to a lie detector) to being essentially even to men (when hooked up to the lie detector.)

Here’s a link to an article on that 2003 study, which satisfies my statistician’s heart. The result was not exactly replicated when they did it more recently:

In this new study, women actually reported more sexual partners than men when they were both hooked up to a lie detector and thought they had to be truthful.

Hold on a second. What? That doesn’t even jive with the oral sex issue we talked about above. There must be some other thing going on. Maybe there’s a selection bias among college kids who do these studies. Maybe we should study if women are more honest than men when they’re attached to lie detectors. Maybe they have an urge to brag when attached to lie detectors.

Next week: stay tuned for OK’s (and y’alls) even more interesting sex question! I’m counting on you guys!

Love,

Aunt Pythia

p.s. I have no idea about the distribution of sexual partners for men and women. We’d have to get our hands on the raw data, which would be awesome. One of the reasons I’m proud to call myself a data scientist.

——

Please submit your sex or data science or other question to Aunt Pythia!

Moneyball Diplomacy

I’m on a train again to D.C. to attend a conference on how to use big data to enhance U.S. diplomacy and development.

I’ll be on a panel in the afternoon called Diving Into Data, which has the following blurb attached to it:

Facebook processes over 500 terabytes of data each day. More than a half billion tweets are sent daily. And so the volume of data grows. Much of this data is superfluous and is of little value to foreign policy and development experts. But a portion does contain significant information and the challenge is how to find and make use of that data. What will a rigorous economic analysis of this data reveal and how could the findings be effectively applied? Looking beyond real-time awareness and some of the other well know uses of big data, this panel will explore how a more thorough in-depth analysis of big data could prove useful in providing insights and trends that could be applied in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy.

Also on the schedule today, two keynote speakers: Nassim Taleb, author of a few books I haven’t read but everyone else has, and Kenneth Neil Cukier, author of a “big data” article I really didn’t like which was published in Foreign Affairs and which I blogged about here under the title of “The rise of big brother, big data”.

The full schedule of the day is here.

Speaking of big brother, this conference will be particularly interesting to me considering the remarkable amount of news we’ve been learning about this week centered on the U.S. as a surveillance state. Actually nothing I’ve read has surprised me, considering what I learned when I read this opinion piece on the subject, and when I watched this video with former NSA mathematician-turned whistleblower, which I blogged about here back in August 2012.

Who speaks Hebrew?

I got covered in an Israeli newspaper talking about Occupy.

Here’s the article. If you can read Hebrew, please tell me how it reads.

Update: here’s a pdf version of it.

Book out for early review

I’m happy to say that the book I’m writing with Rachel Schutt called Doing Data Science is officially out for early review. That means a few chapters which we’ve deemed “ready” have been sent to some prominent people in the field to see what they think. Thanks, prominent and busy people!

It also means that things are (knock on wood) wrapping up on the editing side. I’m cautiously optimistic that this book will be a valuable resource for people interested in what data scientists do, especially people interested in switching fields. The range of topics is broad, which I guess means that the most obvious complaint about the book will be that we didn’t cover things deeply enough, and perhaps that the level of pre-requisite assumptions is uneven. It’s hard to avoid.

Thanks to my awesome editor Courtney Nash over at O’Reilly for all her help!

And by the way, we have an armadillo on our cover, which is just plain cool:

How proxies fail

A lot of the time perfectly well-meaning data goals end up terribly wrong. Certain kinds of these problems stem from the same issue, namely using proxies.

Here’s how it works. People focus on a problem. It’s a real problem, but it’s hard to collect data on the exact question that one would like (how well are students learning? how well is the company functioning? how do we measure risk?).

People have trouble measuring the object in question directly, so they reasonably ask, how do we measure this problem?

They’re smart, so they come up with something, say some metric (standardized test scores, shareprice, VaR). It’s not perfect, though, and so they discuss in detail all the inadequacies with the metric. Even so, they’d really like to address this issue, so they decide to try it.

Then they start using it – hey, it works pretty well in spite of its known issues! We have something to focus on, to improve on!

Then two things happen. First, the people who were so thoughtful at the beginning slowly forget inadequacies of the metric, or are replaced by people who never had that conversation. Slowly the community involved with this proxy starts thinking this thing is a perfect measurement of the thing we actually care about. For all intents and purposes, of course, it is, because that’s what we’re measuring, and that’s how their paycheck is defined.

Second, the discrepancy between the proxy and the original underlying problem becomes more and more of a problem itself, and as people game the proxy, the effectiveness of the proxy is weakened. It no longer does a good job as a stand-in for the original problem, due to gaming and intense focus on the proxy. Sadly, that original problem, which was important, is ignored.

This is a tough problem to solve because we always have the urge to address problems, and we always make do with imperfect proxies and metrics. My guess at the best way to deal with the ensuing problems is to always have a minimum number of different ways to look at and quantify a problem, and to keep in mind each of their inadequacies. Have a dashboard approach, and of course always be on the look-out for metrics that are being gamed. It’s a hard sell of course because it requires deeper understanding and thoughtful interpretation.

How much would you pay to be my friend?

I am on my way to D.C. for a health analytics conference, where I hope to learn the state of the art for health data and modeling. So stay tuned for updates on that.

In the meantime, ponder this concept (hat tip Matt Stoller, who describes it as ‘neoliberal prostitution’). It’s a dating website called “What’s Your Price?” where suitors bid for dates.

What’s creepier, the sex-for-pay aspect of this, or the it’s-possibly-not-about-sex-it’s-about-dating aspect? I’m gonna go with the latter, personally, since it’s a new idea for me. What else can I monetize that I’ve been giving away too long for free?

Hey, kid, you want a bedtime story? It’s gonna cost you.

Let’s enjoy the backlash against hackathons

As much as I have loved my DataKind hackathons, where I get to meet a bunch of friendly nerds who are spend their weekend trying to solve problems using technology, I also have my reservations about the whole weekend hackathon culture, especially when:

- It’s a competition, so really you’re not solving problems as much as boasting, and/or

- you’re trying to solve a problem that nobody really cares about but which might make someone money, so you’re essentially working for free for a future VC asshole, and/or

- you kind of solve a problem that matters, but only for people like you (example below).

As Jake Porway mentions in this fine piece, having data and good intentions do not mean you can get serious results over a weekend. From his essay:

Without subject matter experts available to articulate problems in advance, you get results like those from the Reinvent Green Hackathon. Reinvent Green was a city initiative in NYC aimed at having technologists improve sustainability in New York. Winners of this hackathon included an app to help cyclists “bikepool” together and a farmer’s market inventory app. These apps are great on their own, but they don’t solve the city’s sustainability problems. They solve the participants’ problems because as a young affluent hacker, my problem isn’t improving the city’s recycling programs, it’s finding kale on Saturdays.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve made some good friends and created some great collaborations via hackathons (and especially via Jake). But it only gets good when there’s major planning beforehand, a real goal, and serious follow-up. Actually a weekend hackathon is, at best, a platform from which to launch something more serious and sustained.

People who don’t get that are there for something other than that. What is it? Maybe this parody hackathon announcement can tell us.

It’s called National Day of Hacking Your Own Assumptions and Entitlement, and it has a bunch of hilarious and spot-on satirical commentary, including this definition of a hackathon:

Basically, a bunch of pallid millenials cram in a room and do computer junk. Harmless, but very exciting to the people who make money off the results.

This question from a putative participant of an “entrepreneur”-style hackathon:

“Why do we insist on applying a moral or altruistic gloss to our moneymaking ventures?”

And the internal thought process of a participant in a White House-sponsored hackathon:

I realized, especially in the wake of the White House murdering Aaron Swartz, persecuting/torturing Bradley Manning and threatening Jeremy Hammond with decades behind bars for pursuit of open information and government/corporate accountability that really, no-one who calls her or himself a “hacker” has any business partnering with an entity as authoritarian, secretive and tyrannical as the White House– unless of course you’re just a piece-of-shit money-grubbing disingenuous bootlicker who uses the mantle of “hackerdom” to add a thrilling and unjustified outlaw sheen to your dull life of careerist keyboard-poking for the status quo.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: finally some sex questions!

I’m psyched to be able to answer your sex-related question today, really. I just don’t know how to thank you guys. Please keep them coming.

And by the way, if you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

A bit of a fake [sex question] and [fake sex] question. Is there a correlation between the time taken from initiation to climax in fake sex, a.k.a. porn, and the real thing in studies anywhere?

I’m assuming that the requirements for filming, and the ability of editing, and various other factors (chemicals?) might mean that the simulated stimulation will be longer than the real-life version. If so, does the modal time change over the years (e.g movie theatre production runs vs video tape vs internet streaming times)? Or to put it another way, has our ability to maintain attention actually altered as distribution means have changed?

Fake Name

Dear Fake Name,

For a moment I was confused when I read this, because I so wanted it to be another question entirely, which it really isn’t.

Namely, I was wanting it to be a question of why women’s orgasms in porn never actually happen. I have never once in my entire porn-watching adult life seen a real woman have a real orgasm. WTF? Discussion needs to ensue here, it’s very messed up. Just to be clear, it is possible to see real female orgasms but you have to look for them, and they aren’t really considered mainstream porn.

Now that I know you’re talking about men orgasming, I have the following response: who cares?

Fake questions deserve fake answer,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Help!!! An all male cast of Mathdinosaurs sat on stage at the May 2013 Math Graduation. I wanted to puke from their smugness. We need a token alpha female mathematician here! Will you ask Mathbabe to speak here, please? Can she talk about how amazing little Mathbabes are and make the Mathdinosaurs cry? At least a little?

Will you ask Mathbabe to deliver the commencement address at Berkeley Math graduation in May 2014?

Puking and in need of rehydration

Dear Puking,

I included your question even though it’s not about sex because you’ve invented the phrase “token alpha female” which needed to happen. Also you referred to the Mathbabe in the third person, which she always appreciates.

I’m pretty sure she’d say yes if asked, she loves Berkeley! And she also loves talking about young female mathematicians and how awesome they are.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I recently saw the following statistic:

The survey also questioned students about their sex lives, finding that 72 percent enroll at Harvard as virgins and 27 percent graduate without having sex.

Surely this can’t be right!

Dance Off Pants Off

Dear DOPO,

Wait, why? Does it surprise you that quite a few people start having sex whilst in college? Or does it surprise you that not everyone has had sex by the time they leave? Or are you reading it incorrectly? Note it says: 72% of people didn’t enter actively sexing it up, 27% of people left not actively sexing it up. There’s no contradiction in terms here.

As an aside: my experience while a resident tutor at Harvard, after being an undergrad at UC Berkeley, was that those Ivy League students could really do with some more sex. It might relax them a bit – too stressed out by far.

Again, this is not the question I was hoping for, though. I was hoping for someone to ask me about how it’s possible that on average, when polled, straight men have more sexual partners than the average straight woman. Someone please ask me that, because it’s one of my favorite subjects in statistics.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’ve started experimenting with some kink stuff—nothing too crazy, but sometimes I have rope marks or bruises on my ass. I’m still doing vanilla dating, though. What do I do to explain the marks/bruises when I get intimate with a vanilla guy? Thanks!

Boldly Daringly Sexually Mixing-it-up

Dear BDSM,

Yes! Yes! YES!!! Finally a straight up sex question. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

I have asked a bunch of my favorite kinky people this question in the last couple of days and I’ve gotten a pretty consistent response. I will put them all together in a kind of decision-tree format just to be incredibly nerdy:

1) Only explain it if he asks.

2) If he asks, depending on your mood and how much you enjoy fucking with him and/or how worried you are about his reaction, you might either just tell him the truth outright or you might want to ask him “do you really want to know?”

3) If he answers to that “No I guess not”, depending on how you feel you might want to say, “Oh it’s just from playing rugby”, which for whatever reason seems to be a catch-all explanation of any bodily harm.

4) If he answers “I’m interested in knowing” then tell him the truth outright.

5) Important: when you tell him the truth, it has to be like you’re sharing an awesome thing which he’s lucky to know about. Don’t act ashamed of your kinks, because his reaction to it will be very dependent on how you present it. In other words, talk about it like it’s a secret Star Trek series that nobody’s ever heard about but which is now on Netflix.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your sex or data science or other question to Aunt Pythia!

Technocrats and big data

Today I’m finally getting around to reporting on the congressional subcommittee I went to a few weeks ago on big data and analytics. Needless to say it wasn’t what I’d hoped.

My observations are somewhat disjointed, since there was no coherent discussion, so I guess I’ll just make a list:

- The Congressmen and women seem to know nothing more about the “Big Data Revolution” than what they’d read in the now-famous McKinsey report which talks about how we’ll need 180,000 data scientists in the next decade and how much money we’ll save and how competitive it will make our country.

- In other words, with one small exception I’ll discuss below, the Congresspeople were impressed, even awed, at the intelligence and power of the panelists. They were basically asking for advice on how to let big data happen on a bigger and better scale. Regulation never came up, it was all about, “how do we nurture this movement that is vital to our country’s health and future?”

- There were three useless panelists, all completely high on big data and making their money being like that. First there was a schmuck from the NSF who just said absolutely nothing, had been to a million panels before, and was simply angling to be invited to yet more.

- Next there was a guy who had started training data-ready graduates in some masters degree program. All he ever talked about is how programs like his should be funded, especially his, and how he was talking directly with employers in his area to figure out what to train his students to know.

- It was especially interesting to see how this second guy reacted when the single somewhat thoughtful and informed Congressman, whose name I didn’t catch because he came in and left quickly and his name tag was miniscule, asked him about whether or not he taught his students to be skeptical. The guy was like, I teach my students to be ready to deal with big data just like their employers want. The congressman was like, no that’s not what I asked, I asked whether they can be skeptical of perceived signals versus noise, whether they can avoid making huge costly mistakes with big data. The guy was like, I teach my students to deal with big data.

- Finally there was the head of IBM Research who kept coming up with juicy and misleading pro-data tidbits which made him sound like some kind of saint for doing his job. For example, he brought up the “premature infants are being saved” example I talked about in this post.

- The IBM guy was also the only person who ever mentioned privacy issues at all, and he summarized his, and presumably everyone else’s position on this subject, by saying “people are happy to give away their private information for the services they get in return.” Thanks, IBM guy!

- One more priceless moment was when one of the Congressmen asked the panel if industry has enough interaction with policy makers. The head of IBM Research said, “Why yes, we do!” Thanks, IBM guy!

I was reminded of this weird vibe and power dynamic, where an unchallenged mysterious power of big data rules over reason, when I read this New York Times column entitled Some Cracks in the Cult of Technocrats (hat tip Suresh Naidu). Here’s the leading paragraph:

We are living in the age of the technocrats. In business, Big Data, and the Big Brains who can parse it, rule. In government, the technocrats are on top, too. From Washington to Frankfurt to Rome, technocrats have stepped in where politicians feared to tread, rescuing economies, or at least propping them up, in the process.

The column was written by Chrystia Freeland and it discusses a recent paper entitled Economics versus Politics: Pitfalls of Policy Advice by Daron Acemoglu from M.I.T. and James Robinson from Harvard. A description of the paper from Freeland’s column:

Their critique is not the standard technocrat’s lament that wise policy is, alas, politically impossible to implement. Instead, their concern is that policy which is eminently sensible in theory can fail in practice because of its unintended political consequences.

In particular, they believe we need to be cautious about “good” economic policies that have the side effect of either reinforcing already dominant groups or weakening already frail ones.

“You should apply double caution when it comes to policies which will strengthen already powerful groups,” Dr. Acemoglu told me. “The central starting point is a certain suspicion of elites. You really cannot trust the elites when they are totally in charge of policy.”

Three examples they discuss in the paper: trade unions, financial deregulation in the U.S., privatization in Russia. Examples where something economists suggested would make the system better also acted to reinforce power of already powerful people.

If there’s one thing I might infer from my trip to Washington, it’s that the technocrats in charge nowadays, whose advice is being followed, may have subtly shifted away from deregulation economists and towards big data folks. Not that I’m holding my breath for Bob Rubin to be losing his grip any time soon.

Left Forum panels next weekend: #OWS Alt Banking meeting and a debate with Doug Henwood

Next weekend at Pace University in New York City I’ll be taking part in two panels at the Left Forum, a yearly conference of progressives that everybody who’s anybody seems to know about, although this will be my first year there. For example Noam Chomsky is coming this year.

First, from noon til 1:40 on Saturday June 8th, I’ll be debating how to shrink the financial sector with Doug Henwood, author of Wall Street: how it works and for whom. The panel will be moderated by my buddy Suresh Naidu, an occupier profiled in the Huffington Post. The announcement for this panel is here and includes room information.

Second, from 3:40 til 5:20, also on Saturday June 8th, I’ll be facilitating a meeting of the Alternative Banking group of OWS, which will be loads of fun. The idea is to explain to the panel audience how we roll in Alt Banking, to have a discussion about breaking up the banks, and to get the audience to participate as well. We expect them to enjoy getting on stack. The announcement for this panel is here, please come!

Registration for the Left Forum is still open and is affordable. Go here to register, and see you next weekend!