Huge fan of citibikes

In spite of the nasty corporate connection to megabank Citigroup, I’m a huge of the new bike share program in downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn. I got my annual membership for $95 last week and activated it online and I already used it three times yesterday even though it was raining the whole time.

It helps that I work on 21st street near 6th avenue, which is one of the 300 stations so far set up with bikes. I biked downtown along Broadway to NYU to have lunch with Johan, and since we’d walked along Bleecker Street for some distance, I grabbed a bike from a different station on the way up along 6th.

Then later in the day I was meeting someone at Bryant Park so I biked up there, getting ridiculously wet but being super efficient. Now you know where my priorities are.

Here’s the map I’ve been staring at for the past week. It’s interactive, but just to give you an idea I captured a screenshot:

Friday I’m meeting my buddy Kiri near her work in downtown Brooklyn for lunch. Yeah!!

Sign up today, people!

New Jersey at risk of implementing untested VAM-like teacher evaluation model

This is a guest post by Eugene Stern.

A big reason I love this blog is Cathy’s war on crappy models. She has posted multiple times already about the lousy performance of models that rate teachers based on year-to-year changes in student test scores (for example, read about it here). Much of the discussion focuses on the model used in New York City, but such systems have been, or are being, put in place all over the country. I want to let you know about the version now being considered for use across the river, in New Jersey. Once you’ve heard more, I hope you’ll help me try to stop it.

VAM Background

A little background if you haven’t heard about this before. Because it makes no sense to rate teachers based on students’ absolute grades or test scores (not all students start at the same place each year), the models all compare students’ test scores against some baseline. The simplest thing to do is to compare each student’s score on a test given at the end of the school year against their score on a test given at the end of the previous year. Teachers are then rated based on how much their students’ scores improved over the year.

Comparing with the previous year’s score controls for the level at which students start each year, but not for other factors beside the teacher that affect how much they learn. This includes attendance, in-school environment (curriculum, facilities, other students in the class), out-of-school learning (tutoring, enrichment programs, quantity and quality of time spent with parents/caregivers), and potentially much more. Fancier models try to take these into account by comparing each student’s end of year score with a predicted score. The predicted score is based both on the student’s previous score and on factors like those above. Improvement beyond the predicted score is then attributed to the teacher as “value added” (hence the name “value-added models,” or VAM) and turned into a teacher rating in some way, often using percentiles. One such model is used to rate teachers in New York City.

It’s important to understand that there is no single value-added model, rather a family of them, and that the devil is in the details. Two different teacher rating systems, based on two models of the predicted score, may perform very differently – both across the board, and in specific locations. Different factors may be more or less important depending on where you are. For example, income differences may matter more in a district that provides few basic services, so parents have to pay to get extracurriculars for their kids. And of course the test itself matters hugely as well.

Testing the VAM models

Teacher rating models based on standardized tests have been around for 25 years or so, but two things have happened in the last decade:

- Some people started to use the models in formal teacher evaluation, including tenure decisions.

- Some (other) people started to test the models.

This did not happen in the order that one would normally like. Wanting to make “data-driven decisions,” many cities and states decided to start rating teachers based on “data” before collecting any data to validate whether that “data” was any good. This is a bit like building a theoretical model of how cancer cells behave, synthesizing a cancer drug in the lab based on the model, distributing that drug widely without any trials, then waiting around to see how many people die from the side effects.

The full body count isn’t in yet, but the models don’t appear to be doing well so far. To look at some analysis of VAM data in New York City, start here and here. Note: this analysis was not done by the city but by individuals who downloaded the data after the city had to make it available because of disclosure laws.

I’m not aware of any study on the validity of NYC’s VAM ratings done by anyone actually affiliated with the city – if you know of any, please tell me. Again, the people preaching data don’t seem willing to actually use data to evaluate the quality of the systems they’re putting in place.

Assuming you have more respect for data than the mucky-mucks, let’s talk about how well the models actually do. Broadly, two ways a model can fail are being biased and being noisy. The point of the fancier value-added models is to try to eliminate bias by factoring in everything other than the teacher that might affect a student’s test score. The trouble is that any serious attempt to do this introduces a bunch of noise into the model, to the degree that the ratings coming out look almost random.

You’d think that a teacher doesn’t go from awful to great or vice versa in one year, but the NYC VAM ratings show next to no correlation in a teacher’s rating from one year to the next. You’d think that a teacher either teaches math well or doesn’t, but the NYC VAM ratings show next to no correlation in a teacher’s rating teaching a subject to one grade and their rating teaching it to another – in the very same year! (Gary Rubinstein’s blog, linked above, documents these examples, and a number of others.) Again, this is one particular implementation of a general class of models, but using such noisy data to make significant decisions about teachers’ careers seems nuts.

What’s happening in New Jersey

With all this as background, let’s turn to what’s happening in New Jersey.

You may be surprised that the version of the model proposed by Chris Christie‘s administration (the education commissioner is Christie appointee Chris Cerf, who helped put VAM in place in NYC) is about the simplest possible. There is no attempt to factor out bias by trying to model predicted scores, just a straight comparison between this year’s standardized test score and last year’s. For an overview, see this.

In more detail, the model groups together all students with the same score on last year’s test, and represents each student’s progress by their score on this year’s test, viewed as a percentile across this group. That’s it. A fancier version uses percentiles calculated across all students with the same score in each of the last several years. These can’t be calculated explicitly (you may not find enough students that got exactly the same score each the last few years), so they are estimated, using a statistical technique called quantile regression.

By design, both the simple and the fancy version ignore everything about a student except their test scores. As a modeler, or just as a human being, you might find it silly not to distinguish between a fourth grader in a wealthy suburb who scored 600 on a standardized test from a fourth grader in the projects with the same score. At least, I don’t know where to find a modeler who doesn’t find it silly, because nobody has bothered to study the validity of using this model to rate teachers. If I’m wrong, please point me to a study.

Politics and SGP

But here we get into the shell game of politics, where rating teachers based on the model is exactly the proposal that lies at the end of an impressive trail of doubletalk. Follow the bouncing ball.

These models, we are told, differ fundamentally from VAM (which is now seen as somewhat damaged goods politically, I suspect). While VAM tried to isolate teacher contribution, these models do no such thing – they are simply measuring student progress from year to year, which, after all, is what we truly care about. The models have even been rebranded with a new name: student growth percentiles, or SGP. SGP is sold as just describing student progress rather than attributing it to teachers, there can’t be any harm in that, right? – and nothing that needs validation, either. And because SGP is such a clean methodology – if you’re looking for a data-driven model to use for broad “educational assessment,” don’t get yourself into that whole VAM morass, use SGP instead!

Only before you know it, educational assessment turns into, you guessed it, rating teachers. That’s right: because these models aren’t built to rate teachers, they can focus on the things that really matter (student progress), and thus end up being – wait for it – much better for rating teachers! War is peace, friends. Ignorance is strength.

Creators of SGP

You can find a good discussion of SGP’s and their use in evaluation here, and a lot more from the same author, the impressively prolific Bruce Baker, here. Here’s a response from the creators of SGP. They maintain that information about student growth is useful (duh), and agree that differences in SGP’s should not be attributed to teachers (emphasis mine):

Large-scale assessment results are an important piece of evidence but are not sufficient to make causal claims about school or teacher quality.

SGP and teacher evaluations

But guess what?

The New Jersey Board of Ed and state education commissioner Cerf are putting in place a new teacher evaluation code, to be used this coming academic year and beyond. You can find more details here and here.

Summarizing: for math and English teachers in grades 4-8, 30% of their annual evaluation next year would be mandated by the state to come from those very same SGP’s that, according to their creators, are not sufficient to make causal claims about teacher quality. These evaluations are the primary input in tenure decisions, and can also be used to take away tenure from teachers who receive low ratings.

The proposal is not final, but is fairly far along in the regulatory approval process, and would become final in the next several months. In a recent step in the approval process, the weight given to SGP’s in the overall evaluation was reduced by 5%, from 35%. However, the 30% weight applies next year only, and in the future the state could increase the weight to as high as 50%, at its discretion.

Modeler’s Notes

Modeler’s Note #1: the precise weight doesn’t really matter. If the SGP scores vary a lot, and the other components don’t vary very much, SGP scores will drive the evaluation no matter what their weight.

Modeler’s Note #2: just reminding you again that this data-driven framework for teacher evaluation is being put in place without any data-driven evaluation of its effectiveness. And that this is a feature, not a bug – SGP has not been tested as an attribution tool because we keep hearing that it’s not meant to be one.

In a slightly ironic twist, commissioner Cerf has responded to criticisms that SGP hasn’t been tested by pointing to a Gates Foundation study of the effectiveness of… value-added models. The study is here. It draws pretty positive conclusions about how well VAM’s work. A number of critics have argued, pretty effectively, that the conclusions are unsupported by the data underlying the study, and that the data actually shows that VAM’s work badly. For a sample, see this. For another example of a VAM-positive study that doesn’t seem to stand up to scrutiny, see this and this.

Modeler’s Role Play #1

Say you were the modeler who had popularized SGP’s. You’ve said that the framework isn’t meant to make causal claims, then you see New Jersey (and other states too, I believe) putting a teaching evaluation model in place that uses SGP to make causal claims, without testing it first in any way. What would you do?

So far, the SGP mavens who told us that “Large-scale assessment results are an important piece of evidence but are not sufficient to make causal claims about school or teacher quality” remain silent about the New Jersey initiative, as far as I know.

Modeler’s Role Play #2

Now you’re you again, and you’ve never heard about SGP’s and New Jersey’s new teacher evaluation code until today. What do you do?

I want you to help me stop this thing. It’s not in place yet, and I hope there’s still time.

I don’t think we can convince the state education department on the merits. They’ve made the call that the new evaluation system is better than the current one or any alternatives they can think of, they’re invested in that decision, and we won’t change their minds directly. But we can make it easier for them to say no than to say yes. They can be influenced – by local school administrators, state politicians, the national education community, activists, you tell me who else. And many of those people will have more open minds. If I tell you, and you tell the right people, and they tell the right people, the chain gets to the decision makers eventually.

I don’t think I could convince Chris Christie, but maybe I could convince Bruce Springsteen if I met him, and maybe Bruce Springsteen could convince Chris Christie.

VAM-anifesto

I thought we could start with a manifesto – a direct statement from the modeling community explaining why this sucks. Directed at people who can influence the politics, and signed by enough experts (let’s get some big names in there) to carry some weight with those influencers.

Can you help? Help write it, sign it, help get other people to sign it, help get it to the right audience. Know someone whose opinion matters in New Jersey? Then let me know, and help spread the word to them. Use Facebook and Twitter if it’ll help. And don’t forget good old email, phone calls, and lunches with friends.

Or, do you have a better idea? Then put it down. Here. The comments section is wide open. Let’s not fall back on criticizing the politicians for being dumb after the fact. Let’s do everything we can to keep them from doing this dumb thing in the first place.

Shame on us if we can’t make this right.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: fake sex, boredom, peeing in the toilet, knitting Klein bottles, and data project management

If you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Please submit your questions for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this column!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Do you prefer that we ask you fake [sex questions] or [fake sex] questions? From your website it seems that you prefer the former, but would you also be amused by the latter?

Fakin’ Bacon

Dear Fakin,

I can’t tell, because I’ve gotten neither kind (frowny face).

If I started getting a bunch then I could do some data collecting on the subject. If I had to guess I’d go with the latter though.

Bring it on!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

Are boredom and intelligence correlated?

Bored

Dear Bored,

It has been my fantasy for quite a few years to be bored. Hasn’t happened. All I can conclude from my own experience is that being a working mother of three, blogger, knitting freak, and activist is not correlated to boredom.

Aunt P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How can I get my husband to pee IN the toilet?

Pee I Shouldn’t See Ever, Dammit

Dear PISSED,

Start by asking him to be in charge of cleaning the bathroom. If that’s insufficient ask him to sit down to pee – turns out men can do that. If he’s unwilling, suggest that you’re going to pee standing up now for women’s lib reasons (whilst he’s still in charge of cleaning the bathroom).

Hope I helped!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How can I get my wife to stop nagging me about peeing in the toilet?

Isaac Peter Freely

Dear I.P. Freely,

Look for a nearby gas station and do your business there. That’ll shut her up.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Is there any reason I should bother knitting a Klein Bottle? Isn’t just knowing I could do it enough? Or would it actually impress (or give pleasure to) others?

Procrastinating Parametricist

Dear PP,

If you’re looking for an excuse to knit a Klein Bottle, find a high school math teacher that would be psyched to use it as an exhibit for their class.

If you’re trying to understand how to rationalize the act of knitting anything ever, give up immediately, it makes no sense. We knitters do it because we love doing it.

Love and kisses,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a Data Scientist (or Business Analytics pretending to be a Data Scientist) and I’m the leader of a small team at the company work for. We have to analyse data, fit models and so on. I’m struggling right now trying to figure out what’s the best way to manage our analysis.

I’m reading some stuff related to project management, and some stuff related to Scrum. However, at least for now, I don’t think they exactly fit our needs. Scrum seems great for software development, but I’m not so sure it works well for modeling development or statistical prototyping. Do you have any ideas on this? Should I just try scrum anyway?

Typically, most of our projects begin with some loose equirements (we want to understand this and that, or to predict this and that, or to learn the causal effect of this and that). Then, we get some data, spend sometime cleaning and aggregating it, then doing some descriptive analysis, some model fit and then preparing to present our results. I always have in mind what our results will look like, but there is always something I didn’t expect to intervene.

Say, I’m calculating the size of control group and then I realize my variables of interest aren’t normally distributed and have to adapt the way we compute sample size of control group. Then either I do a rough calculation based on assumptions of normality of data or we study and adapt new ways to better approximate our data (say, using a lognormal distribution). Anyway, I’ll probably delay our results or deliver results with inferior quality.

So, my question is, do you know of any software or methodology to use with data science or data analysis in the same ways as there is Scrum for software development?

Brazilian (fake?) Data Scientist

Dear B(f)DS,

I agree with you, data projects aren’t the same kettle of fish as engineering projects. By their very nature they take whimsical turns that can’t be drawn up beforehand.

Even so, I think forcing oneself to break down the steps of a data project can be useful, and for that reason I like using project management tools when I do data projects – not that it will give me a perfect estimate of time til completion, which it won’t, but it will give me a sense of trajectory of the project.

It helps, for example, if I say something like, “I’ll try to be done with exploratory data analysis by the end of the second day.” Otherwise I might just keep doing that without really getting much in return, but if I know I only have two days to squeeze out the juice, I’ll be more thoughtful and targeted in my work.

The other thing about using those tools is that upper-level managers love them. I think they love them so much that it’s worth using them even knowing they will be inaccurate in terms of time, because it makes people feel more in control. And actually being inaccurate doesn’t mean they’re meaningless – there’s more information in those estimates than in nothing.

Finally, one last thing that’s super useful about those tools is that, if your data team is being overloaded with work, you can use the tool to push back. So if someone is giving you a new project, you can point to all the other projects you already have and say, “these are all the projects that won’t be getting done if I take this one on.” Make the tool work for you!

To sum up, I say you try Scrum. After a few projects you can start doing a data analysis on Scrum, estimating how much of a time fudge factor you should add to each estimate do to unforeseen data issues.

I hope that’s helpful,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your question to Aunt Pythia!

The Bounded Gaps Between Primes Theorem has been proved

There’s really exciting news in the world of number theory, my old field. I heard about it last month but it just hit the mainstream press.

Namely, mathematician Yitang Zhang just proved is that there are infinitely many pairs of primes that differ by at most 70,000,000. His proof is available here and, unlike Mochizuki’s claim of a proof of the ABC Conjecture, this has already been understood and confirmed by the mathematical community.

Go take a look at number theorist Emmanuel Kowalski‘s blog post on the subject if you want to understand the tools Zhang used in his proof.

Also, my buddy and mathematical brother Jordan Ellenberg has an absolutely beautiful article in Slate explaining why mathematicians believed this theorem had to be true, due to the extent to which we can consider prime numbers to act as if they are “randomly distributed.” My favorite passage from Jordan’s article:

It’s not hard to compute that, if prime numbers behaved like random numbers, you’d see precisely the behavior that Zhang demonstrated. Even more: You’d expect to see infinitely many pairs of primes that are separated by only 2, as the twin primes conjecture claims.

(The one computation in this article follows. If you’re not onboard, avert your eyes and rejoin the text where it says “And a lot of twin primes …”)

Among the first N numbers, about N/log N of them are primes. If these were distributed randomly, each number n would have a 1/log N chance of being prime. The chance that n and n+2 are both prime should thus be about (1/log N)^2. So how many pairs of primes separated by 2 should we expect to see? There are about N pairs (n, n+2) in the range of interest, and each one has a (1/log N)^2 chance of being a twin prime, so one should expect to find about N/(log N)^2 twin primes in the interval.

Congratulations!

Fight back against surveillance using TrackMeNot, TrackMeNot mobile?

After two days of travelling to the west coast and back, I’m glad to be back to my blog (and, of course, my coffee machine, which is the real source of my ability to blog every morning without distraction: it makes coffee at the push of a button, and that coffee has a delicious amount of caffeine).

Yesterday at the hotel I grabbed a free print edition of the Wall Street Journal to read on the plane, and I was super interested in this article called Phone Firm Sells Data on Customers. They talk about how phone companies (Verizon, specifically) are selling location data and browsing data about customers, how some people might be creeped out by this, and then they say:

The new offerings are also evidence of a shift in the relationship between carriers and their subscribers. Instead of merely offering customers a trusted conduit for communication, carriers are coming to see subscribers as sources of data that can be mined for profit, a practice more common among providers of free online services like Google Inc. and Facebook Inc.

Here’s the thing. It’s one thing to make a deal with the devil when I use Facebook: you give me something free, in return I let you glean information about me. But in terms of Verizon, I pay them like $200 per month for my family’s phone usage. That’s not free! Fuck you guys for turning around and selling my data!

And how are marketers going to use such location data? They will know how desperate you are for their goods and charge you accordingly. Like this for example, but on a much wider scale.

There are a two things I can do to object to this practice. First, I write this post and others, railing against such needless privacy invasion practices. Second, I can go to Verizon, my phone company, and get myself off the list. The instructions for doing so seem to be here, but I haven’t actually followed them yet.

Here’s what I wish a third option were: a mobile version of Trackmenot, which I learned about last week from Annelies Kamran.

Trackmenot, created by Daniel C. Howe and Helen Nissenbaum at what looks like the CS department of NYU, confuses the data gatherers by giving them an overload of bullshit information.

Specifically, it’s a Firefox add-on which sends you to all sorts of websites while you’re not actually using your browser. The data gatherers get endlessly confused about what kind of person you actually are this way, thereby fucking up the whole personal data information industry.

I have had this idea in the past, and I’m super happy it already exists. Now can someone do it for mobile please? Or even better, tell me it already exists?

Mr. Ratings Reformer Goes to Washington: Some Thoughts on Financial Industry Activism

This is a guest post by Marc Joffe, the principal consultant at Public Sector Credit Solutions, an organization that provides data and analysis related to sovereign and municipal securities. Previously, Joffe was a Senior Director at Moody’s Analytics for more than a decade.

Note to readers: for a bit of background on the SEC Credit Ratings Roundtable and the Franken Amendment see this recent mathbabe post.

I just returned from Washington after participating in the SEC’s Credit Ratings Roundtable. The experience was very educational, and I wanted to share what I’ve learned with readers interested in financial industry reform.

First and foremost, I learned that the Franken Amendment is dead. While I am not a proponent of this idea – under which the SEC would have set up a ratings agency assignment authority – I do welcome its intentions and mourn its passing. Thus, I want to take some time to explain why I think this idea is dead, and what financial reformers need to do differently if they want to see serious reforms enacted.

The Franken Amendment, as revised by the Dodd Frank conference committee, tasked the SEC with investigating the possibility of setting up a ratings assignment authority and then executing its decision. Within the SEC, the responsibility for Franken Amendment activities fell upon the Office of Credit Ratings (OCR), a relatively new creature of the 2006 Credit Rating Agency Reform Act.

OCR circulated a request for comments – posting the request on its web site and in the federal register – a typical SEC procedure. The majority of serious comments OCR received came from NRSROs and others with a vested interest in perpetuating the status quo or some close approximation thereof. Few comments came from proponents of the Franken Amendment, and some of those that did were inarticulate (e.g., a note from Joe Sixpack of Anywhere, USA saying that rating agencies are terrible and we just gotta do something about them).

OCR summarized the comments in its December 2012 study of the Franken Amendment. Progressives appear to have been shocked that OCR’s work product was not an originally-conceived comprehensive blueprint for a re-imagined credit rating business. Such an expectation is unreasonable. SEC regulators sit in Washington and New York; not Silicon Valley. There is little upside and plenty of political downside to taking major risks. Regulators are also heavily influenced by the folks they regulate, since these are the people they talk to on a day-to-day basis.

Political theorists Charles Lindblom and Aaron Wildavsky developed a theory that explains the SEC’s policymaking process quite well: it is called incrementalism. Rather than implement brand new ideas, policymakers prefer to make marginal changes by building upon and revising existing concepts.

While I can understand why Progressives think the SEC should “get off its ass” and really fix the financial industry, their critique is not based in the real world. The SEC is what it is. It will remain under budget pressure for the forseeable future because campaign donors want to restrict its activities. Staff will always be influenced by financial industry players, and out-of-the-box thinking will be limited by the prevailing incentives.

Proponents of the Franken Amendment and other Progressive reforms have to work within this system to get their reforms enacted. How? The answer is simple: when a request for comment arises they need to stuff the ballot box with varying and well informed letters supporting reform. The letters need to place proposed reforms within the context of the existing system, and respond to anticipated objections from status quo players. If 20 Progressive academics and Occupy-leaning financial industry veterans had submitted thoughtful, reality-based letters advocating the Franken Amendment, I believe the outcome would have been very different. (I should note that Occupy the SEC has produced a number of comment letters, but they did not comment on the Franken Amendment and I believe they generally send a single letter).

While the Franken Amendment may be dead, I am cautiously optimistic about the lifecycle of my own baby: open source credit rating models. I’ll start by explaining how I ended up on the panel and then conclude by discussing what I think my appearance achieved.

The concept of open source credit rating models is extremely obscure. I suspect that no more than a few hundred people worldwide understand this idea and less than a dozen have any serious investment in it. Your humble author and one person on his payroll, are probably the world’s only two people who actually dedicated more than 100 hours to this concept in 2012.

That said, I do want to acknowledge that the idea of open source credit rating models is not original to me – although I was not aware of other advocacy before I embraced it. Two Bay Area technologists started FreeRisk, a company devoted to open source risk models, in 2009. They folded the company without releasing a product and went on to more successful pursuits. FreeRisk left a “paper” trail for me to find including an article on the P2P Foundation’s wiki. FreeRisk’s founders also collaborated with Cate Long, a staunch advocate of financial markets transparency, to create riski.us – a financial regulation wiki.

In 2011, Cathy O’Neil (a.k.a. Mathbabe) an influential Progressive blogger who has a quantitative finance background ran a post about the idea of open source credit ratings, generating several positive comments. Cathy also runs the Alternative Banking group, an affiliate of Occupy Wall Street that attracts a number of financially literate activists.

I stumbled across Cathy’s blog while Googling “open source credit ratings”, sent her an email, had a positive phone conversation and got an invitation to address her group. Cathy then blogged about my open source credit rating work. This too was picked up on the P2P Foundation wiki, leading ultimately to a Skype call with the leader of the P2P Foundation, Michel Bauwens. Since then, Michel – a popularizer of progressive, collaborative concepts – has offered a number of suggestions about organizations to contact and made a number of introductions.

Most of my outreach attempts on behalf of this idea – either made directly or through an introduction – are ignored or greeted with terse rejections. I am not a proven thought leader, am not affiliated with a major research university and lack a resume that includes any position of high repute or authority. Consequently, I am only a half-step removed from the many “crackpots” that send around their unsolicited ideas to all and sundry.

Thus, it is surprising that I was given the chance to address the SEC Roundtable on May 14. The fact that I was able to get an invitation speaks well of the SEC’s process and is thus worth recounting. In October 2012, SEC Commissioner Dan Gallagher spoke at the Stanford Rock Center on Corporate Governance. He mentioned that the SEC was struggling with the task of implementing Dodd Frank Section 939A, which calls for the replacement of credit ratings in federal regulations, such as those that govern asset selection by money market funds.

After his talk, I pitched him the idea of open source credit ratings as an alternative creditworthiness standard that would satisfy the intentions of 939A. He suggested that I write to Tom Butler, head of the Office of Credit Ratings (OCR) and copy him. This led to a number of phone calls and ultimately a presentation to OCR staff in New York in January. Staff members that joined the meeting were engaged and asked good questions. I connected my proposal to an earlier SEC draft regulation which would have required structured finance issuers to publish cashflow waterall models in Python – a popular open source language.

I walked away from the meeting with the perception that, while they did not want to reinvent the industry, OCR staff were sincerely interested in new ideas that might create incremental improvements. That meeting led to my inclusion in the third panel of the Credit Ratings Roundtable.

For me, the panel discussion itself was mostly positive. Between the opening statement, questions and discussion, I probably had about 8 minutes to express my views. I put across all the points I hoped to make and even received a positive comment from one of the other panelists. On the downside, only one commissioner attended my panel – whereas all five had been present at the beginning of the day when Al Franken, Jules Kroll, Doug Peterson and other luminaries held the stage.

The roundtable generated less media attention than I expected, but I got an above average share of the limited coverage relative to the day’s other 25 panelists. The highlight was a mention in the Wall Street Journal in its pre-roundtable coverage.

Perhaps the fact that I addressed the SEC will make it easier for me to place op-eds and get speaking engagements to promote the open source ratings concept. Only time will tell. Ultimately, someone with a bigger reputation than mine will need to advocate this concept before it can progress to the next level.

Also, the idea is now part of the published record of SEC deliberations. The odds of it getting into a proposed regulation remain long in the near future, but these odds are much shorter than they were prior to the roundtable.

Political scientist John Kingdon coined the term “policy entrepreneurs” to describe people who look for and exploit opportunities to inject new ideas into the policy discussion. I like to think of myself as a policy entrepreneur, although I have a long way to go before I become a successful one. If you have read this far and also have strongly held beliefs about how the financial system should improve, I suggest you apply the concepts of incrementalism and policy entrepreneurship to your own activism.

Eben Moglen teaches us how not to be evil when data-mining

This is a guest post by Adam Obeng, a Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology Department at Columbia University. His work encompasses computational social science, social network analysis and sociological theory (basically anything which constitutes an excuse to sit in front of a terminal for unadvisably long periods of time). This post is Copyright Adam Obeng 2013 and licensed under a (Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Crossposted on adamobeng.com.

Eben Moglen’s delivery leaves you in no doubt as to the sincerity of this sentiment. Stripy-tied, be-hatted and pocked-squared, he took to the stage at last week’s IDSE Seminar Series event without slides, but with engaging — one might say, prosecutorial — delivery. Lest anyone doubt his neckbeard credentials, he let slip that he had participated in the development of almost certainly the first networked email system in the United States, as well as mentioning his current work for the Freedom Box Foundation and the Software Freedom Law Center.

A superorganism called humankind

The content was no less captivating than the delivery: we were invited to consider the world where every human consciousness is connected by an artificial extra-skeletal nervous system, linking everyone into a new superorganism. What we refer to as data science is the nascent study of flows of neural data in that network. And having access to the data will entirely transform what the social sciences can explain: we will finally have a predictive understanding of human behaviour, based not on introspection but empirical science. It will do for the social sciences what Newton did for physics.

The reason the science of the nervous system – “this wonderful terrible art” – is optimised to study human behaviour is because consumption and entertainment are a large part of economic activity. The subjects of the network don’t own it. In a society which is more about consumption than production, the technology of economic power will be that which affects consumption. Indeed, what we produce becomes information about consumption which is itself used to drive consumption. Moglen is matter-of-fact: this will happen, and is happening.

And it’s also ineluctable that this science will be used to extend the reach of political authority, and it has the capacity to regiment human behaviour completely. It’s not entirely deterministic that it should happen at a particular place and time, but extrapolation from history suggests that somewhere, that’s how it’s going to be used, that’s how it’s going to come out, because it can. Whatever is possible to engineer will eventually be done. And once it’s happened somewhere, it will happen elsewhere. Unlike the components of other super-organisms, humans possess consciousness. Indeed, it is the relationship between sociality and consciousness that we call the human condition. The advent of the human species-being threatens that balance.

The Oppenheimer moment

Moglen’s vision of the future is, as he describes it, both familiar and strange. But his main point, is as he puts it, very modest: unless you are sure that this future is absolutely 0% possible, you should engage in the discussion of its ethics.

First, when the network is wrapped around every human brain, privacy will be nothing more than a relic of the human past. He believes that privacy is critical to creativity and freedom, but really the assumption that privacy – the ability to make decisions independent of the machines – should be preserved is axiomatic.

What is crucial about privacy is that it is not personal, or even bilateral, it is ecological: how others behave determine the meaning of the actions I take. As such, dealing with privacy requires an ecological ethics. It is irrelevant whether you consent to be delivered poisonous drinking water, we don’t regulate such resources by allowing individuals to make desicions about how unsafe they can afford their drinking water to be. Similarly, whether you opt in or opt out of being tracked online is irrelevant.

The existing questions of ethics that science has had to deal with – how to handle human subjects – are of no use here: informed consent is only sufficient when the risks to investigating a human subject produce apply only to that individual.

These ethical questions are for citizens, but perhaps even more so for those in the business of making products from personal information. Whatever goes on to be produced from your data will be trivially traced back to you. Whatever finished product you are used to make, you do not disappear from it. What’s more, the scientists are beholden to the very few secretive holders of data.

Consider, says Moglen,the question of whether punishment deters crime: there will be increasing amounts of data about it, but we’re not even going to ask – because no advertising sale depends on it. Consider also, the prospect of machines training humans, which is already beginning to happen. The Coursera business model is set to do to the global labour market what Google did to the global advertising market: auctioning off the good learners, found via their learning patterns, to to employers. Granted, defeating ignorance on a global scale is within grasp. But there are still ethical questions here, and evil is ethics undealt with.

One of the criticisms often levelled at techno-utopians is that the enabling power of technology can very easily be stymied by the human factors, the politics, the constants of our species, which cannot be overwritten by mere scientific progress. Moglen could perhaps be called a a techno-dystopian, but he has recognised that while the technology is coming, inevitably, how it will affect us depends on how we decide to use it.

But these decisions cannot just be made at the individual level, Moglen pointed out, we’ve changed everything except the way people think. I can’t say that I wholeheartedly agree with either Moglen’s assumptions or his conclusions, but he is obviously asking important questions, and he has shown the form in which they need to be asked.

Another doubt: as a social scientist, I’m also not convinced that having all these data available will make all human behaviour predictable. We’ve catalogued a billion stars, the Large Hadron Collider has produced a hundred thousand million million bytes of data, and yet we’re still trying to find new specific solutions to the three-body problem. I don’t think that just having more data is enough. I’m not convinced, but I don’t think it’s 0% possible.

This post is Copyright Adam Obeng 2013 and licensed under a (Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License).

Money, food, and the local

I take the Economist into the bath with me on the weekend when I have time. It’s relaxing for whatever reason, even when it’s describing horrible things or when I disagree with it. I appreciate the Economist for at least discussing many of the issues I care about.

Last night I came across this book review, about the book “Money: The Unauthorised Biography” written by Felix Martin. It tells the story of an ad hoc currency system in Ireland popping up during a financial crisis more than 40 years ago. The moral of that story is supposed to be something about how banking should operate, but I was struck by this line in the review:

It helped that a lot of Irish life is lived locally: builders, greengrocers, mechanics and barmen all turned out to be dab hands at personal credit profiling.

It occurs to me that “living locally” is exactly what most people, at least in New York, don’t do at all.

At this point I’ve lived in my neighborhood near Columbia University for 8 years, which is long enough to know Bob, the guy at the hardware store who sells me air conditioners and spatulas. If our currency system froze and we needed to use IOU notes, I’m pretty sure Bob and I would be good.

But, even though I shop at Morty’s (Morton Williams) regularly, the turnover there is high enough that I have never connected with anyone working there. I’m shit out of luck for food, in other words, in the case of a currency freeze.

Bear with me for one more minute. When I read articles like this one, which is called Pay People to Cook at Home – in which the author proposes a government program that will pay young parents to stay home and cook healthy food – it makes me think two things.

First, that people sometimes get confused between what could or should happen and what might actually happen, mostly because they don’t think about power and who has it and what their best interests are. I’m not holding my breath for this government program, in other words, even though I think there’s definitely a link between a hostile food environment and bad health among our nation’s youth.

Second, that in some sense we traditionally had pretty good solutions to child care and home cooking, namely we lived together with our families and not everyone had a job, so someone was usually on hand to cook and watch the kids. It’s a natural enough arrangement, which we’ve chucked in favor of a cosmopolitan existence.

And when I say “natural”, I don’t mean “appealing”: my mom has a full-time job as a CS professor in Boston and is not interested in staying home and cooking. Nor am I, for that matter.

In other words, we’ve traded away localness for something else, which I’m personally benefitting from, but there are other direct cultural effects which aren’t always so awesome. Our dependency on international banking and credit scores and having very little time to cook for our kids are a few examples.

Housing bubble or predictable consequence of income inequality?

It’s Sunday, which for me is a day of whimsical smoke-blowing. To mark the day, I think I’ll assume a position about something I know very little about, namely real estate. Feel free to educate me if I’m saying something inaccurate!

There has been a flurry of recent articles warning us that we might be entering a new housing bubble, for example this Bloomberg article. But if you look closely, the examples they describe seem cherry picked:

An open house for a five-bedroom brownstone in Brooklyn, New York, priced at $949,000 drew 300 visitors and brought in 50 offers. Three thousand miles away in Menlo Park, California, a one-story home listed for $2 million got six offers last month, including four from builders planning to tear it down to construct a bigger house. In south Florida, ground zero for the last building boom and bust, 3,300 new condominium units are under way, the most since 2007.

They mention later that Boston hasn’t risen so high as the others hot cities recently, but if you compare Boston to, say, Detroit on this useful Case-Schiller city graph, you’ll note that Boston never really went that far down in the first place.

When I read this kind of article, I can’t help but wonder how much of the signal they are seeing is explained by income inequality, combined with the increasing segregation of rich people in certain cities. New York City and Menlo Park are great examples of places where super rich people live, or want to live, and it’s well known that those buyers have totally recovered from the recession (see for example this article).

And it’s not even just American rich people investing in these cities. Judging from articles like this one in the New York Times, we’re now building luxury sky-scrapers just to attract rich Russians. The fatness of this real estate tail is extraordinary, and it makes me think that when we talk about real estate recoveries we should have different metrics than simply “average sell price”. We need to adjust our metrics to reflect the nature of the bifurcated market.

Now it’s also true that other cities, like Phoenix and Las Vegas are also gaining in the market. Many of the houses in these unsexier areas are being gobbled up by private equity firms investing in rental property. This is a huge part of the market right now in those places, and they buy whole swaths of houses at once. Note we’re not hearing about open houses with 300 buyers there.

Besides considering the scary consequences of a bunch of enormous profit-seeking management companies controlling our nation’s housing, and changing the terms of the rental agreements, I’ll just point out that these guys probably aren’t going to build too large a bubble, since their end-feeder is the renter, the average person who has a very limited income and ability to pay, unlike the Russians. On the other hand, they probably don’t know what they’re doing, so my error bars are large.

I’m not saying we don’t have a bubble, because I’d have to do a bunch of reckoning with actual numbers to understand stuff more. I’m just saying articles like the Bloomberg one don’t convince me of anything besides the fact that very rich people all want to live in the same place.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: not at all about sex

Aunt Pythia is yet again gratified to find a few new questions in her inbox this morning. Sad to say, today’s column really has nothing to do with sex, but I hope you’ll enjoy it anyway. And don’t forget:

——

Aunt Pythia,

I’m an academic in a pickle. How do I deal with papers that are years old, that I’m sick of, but that I need to get off my slate and how do I prevent this from happening again? I always want to do the work for the first 75% of the paper and then I get bored. But then I’m left with a pile of papers which, with a biiiit more work, they could be done.

Not Yet Tenured

Dear NYT,

One thing they never teach you in grad school is how to manage projects, mostly because you only have one project in grad school, which is to learn everything the first two years then do something magical and new the second two years. Even though that plan isn’t what ends up happening, it’s always in the back of your mind. In particular you only really need to focus on one thing, your thesis.

But when you get out into the real world, things change. You have options, and these option make a difference to your career and your happiness (actually your thesis work makes a difference to those things too but again, in grad school you don’t have many options).

You need a process, my friend! You need a way of managing your options. Think about this from the end backwards: after you’re done you want a prioritized list of your projects, which is a way more positive way to deal with things than letting them make you feel guilty or thinking about which ones you can drop without deeper analysis.

Here’s my suggestion, which I’ve done and it honestly helps. Namely, start a spreadsheet of your projects, with a bunch of tailored-to-you columns. Note to non-academics: this works equally well with non-academic projects.

So the first column will be the name of the project, then the year you started it, and then maybe the amount of work til completion, and then maybe the probability of success, and then how much you will like it when it’s done, and then how good it will be for your career, and then how good it will be for other non-career reasons. You can add other columns that are pertinent to your decision. Be sure to include a column that measures how much you actually feel like working on it, which is distinct from how much you’ll like it when it’s done.

All your columns entries should be numbers so we can later make weighted averages. And they should all go up when they get “better”, except time til completion, which goes down when it gets better. And if you have a way to measure one project, be sure to measure all the projects by that metric, even if they mostly score a neutral. So if one project is good for the environment, every project gets an “environment” score.

Next, decide which columns need the most attention – prioritize or weight the attributes instead of the projects for now. This probably means you put lots of weight on the “time til completion” combined with “value towards tenure” for now, especially if you’re running out of time for tenure. How you do this will depend on what resources you have in abundance and what you’re running low on. You might have tenure, and time, and you might be sick of only doing things that are good for your career but that don’t save the environment, in which case your weights on the columns will be totally different.

Finally, take some kind of weighted average of each project’s non-time attributes to get that project’s abstract attractiveness score, and then do something like divide that score by the amount of time til completion or the square root of the time to completion to get an overall “I should really do this” score. If you have two really attractive projects, each scoring 8 on the abstract attractiveness score, and one of them will take 2 weeks to do and the other 4 weeks, then the 2-week guy gets an “I should really do this” of 4, which wins over the other project with an “I should really do this” score of 2.

Actually you probably don’t have to do the math perfectly, or even explicitly. The point is you develop in your head ways by which to measure your own desire to do your projects, as well as how important those projects are to you in external ways. By the end of your exercise you’ll know a bunch more about your projects. You also might do this and disagree with the results. That usually means there’s an attribute you ignored, which you should now add. It’s probably the “how much I feel like doing this” column.

You might not have a perfect system, but you’ll be able to triage into “put onto my calendar now”, “hope to get to”, and “I’ll never finish this, and now I know why”.

Final step: put some stuff onto your calendar in the first category, along with a note to yourself to redo the analysis in a month or two when new projects have come along and you’ve gotten some of this stuff knocked off.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a freshly minted data scientist working in the banking industry. My company doesn’t seem they know what to do with me. Although they are a ginormous company, I am currently their sole “official” data scientist. They are just now developing their ability to work with Big Data, and are far from the capability to work with unstructured, nontraditional data sources. There are, apparently, grand (but vague) plans in the future for me and a future DS team. So far, however, they’ve put me in a predictive analytics group. and have me developing fairly mundane marketing models. They are excited about faster, in-database processes and working with larger (but still structured) data sets, but their philosophy seems to still be very traditional. They want more of the same, but faster. It doesn’t seem like they have a good idea of what data science can bring to the table. And with few resources, fellow data scientists, or much experience in the field (I came from academia), I’m having a hard time distinguishing myself and my work from what their analytics group has been doing for years. How can I make this distinction? And with few resources, what general things can I be doing now to shape the future of data science at my company?

Thanks,

Newly Entrenched With Bankers

Dear NEWB,

First, I appreciate your fake name.

Second, there’s no way you can do your job right now short of becoming a data engineer yourself and starting to hit the unstructured data with mapreduce jobs. That would be hardcore, by the way.

Third, my guess is they hired you either so they could say they had a data scientist, so pure marketing spin, which is 90% likely, or because they really plan on getting a whole team to do data science right, which I put at 1%. The remaining 9% is that they had no idea why they hired you, someone just told them to do it or something.

My advice is to put together a document for them explaining the resources you’d need to actually do something beyond the standard analytics team. Be sure to explain what and why you need those things, including other team members. Be sure and include some promises of what you’d be able to accomplish if you had those things.

Then, before handing over that document, decide whether to deliver it with a threat that you’ll leave the job unless they give you the resources in a reasonable amount of time or not. Chances are you’d have to leave, because chances are they don’t do it.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your question to Aunt Pythia!

Dow at an all-time high, who cares?

The Dow is at an all-time high. Here’s the past 12 months:

Once upon a time it might have meant something good, in a kind of “rising tide lifts all boats” sort of way. Nowadays not so much.

Of course, if you have a 401K you’ll probably be a bit happier than you were 4 years ago. Or if you’re an investor with money in the game.

On the other hand, not many people have 401K plans, and not many who do don’t have a lot of money in them, partly because one in four people have needed to dip into their savings lately in spite of the huge fees they were slapped with for doing so. Go watch the recent Frontline episode about 401Ks to learn more about this scammy industry.

Let’s face it, the Dow is so high not because the economy is great, or even because it is projected to be great soon. It’s mostly inflated out of a combination of easy Fed money for banks, which translates to easy money for people who are already rich, and the fact that world-wide investors are afraid of Europe and are parking their money in the U.S. until the Euro problem gets solved.

In other words, that money is going to go away if people decide Europe looks stable, or if the Fed decides to raise interest rates. The latter might happen when the economy (or rather, if the economy) looks better, so putting that together we’re talking about a possible negative stock market response to a positive economic outlook.

The stock market has officially become decoupled from our nation’s future.

Star Trek is my religion

I was surprised and somewhat disappointed yesterday when I found this article about Star Trek in Slate, written by Matt Yglesias. He, like me, has recently been binging on Star Trek and has decided to explain “why Star Trek is great” – also my long-term plan. He stole my idea!

My disappointment turned to amazement and glee, however, when I realized that the episode he began his column with was the exact episode I’d just finished watching about 5 minutes before I’d found his article. What are the chances??

It must be fate. Me and Matt are forever linked, even if he doesn’t care (I’m pretty sure he cares though, Trekkies are bonded like that). Plus, I figured, now that he’s written a Star Trek post, I’ll do so as well and we can act like it’s totally normal. Where’s your Star Trek post?

Here’s his opening paragraph:

In the second episode of the seventh season of the fourth Star Trek television series, Icheb, an alien teenage civilian who’s been living aboard a Federation vessel for several months after having been rescued from both the Borg and abusive parents, issues a plaintive cry: “Isn’t that what people on this ship do? They help each other?”

That’s the thing about Star Trek. It’s utopian. There’s no money, partly because they have ways to make food and objects materialize on a whim. There’s no financial system of any kind that I’ve noticed, although there’s plenty of barter, mostly dealing in natural resources. And the crucial resource that characters are constantly seeking, that somehow make the ships fly through space, are called dilithium crystals. They’re rare but they also seem to be lying around on uninhabited planets, at least for now.

But it’s not my religion just because they’ve somehow evolved past too-big-to-fail banks. It’s that they have ethics, and those ethics are collaborative, and moreover are more basic and more important than the power of technology: the moral decisions that they are confronted with and that they make are, in fact, what Star Trek is about.

Each episode can be seen as a story from a nerd bible. Can machines have a soul? Do we care less about those souls than human (or Vulcan) souls? If we come across a civilization that seems to vitally need our wisdom or technology, when do we share it? And what are the consequences for them when we do or don’t?

In Star Trek, technology is not an unalloyed good: it’s morally neutral, and it could do evil or good, depending on the context. Or rather, people could do evil or good with it. This responsibility is not lost in some obfuscated surreality.

My sons and I have a game we play when we watch Star Trek, which we do pretty much any night we can, after all the homework is done and before bed-time. It’s kind of a “spot that issue” riddle, where we decide which progressive message is being sent to us through the lens of an alien civilization’s struggles and interactions with Captain Picard or Janeway.

Gay marriage!

Confronting sexism!

Overcoming our natural tendencies to hoard resources!

Some kids go to church, my kids watch Star Trek with me. I’m planning to do a second round when my 4-year-old turns 10. Maybe Deep Space 9. And yes, I know that “true scifi fans” don’t like Star Trek. My father, brother, and husband are all scifi fans, and none of them like Star Trek. I kind of know why, and it’s why I’m making my kids watch it with me before they get all judgy.

One complaint I’ve considered having about Star Trek is that there’s no road map to get there. After all, how are people convinced to go from a system in which we don’t share resources to one where we do? How do we get to the point where everyone’s fed and clothed and can concentrate on their natural curiosity and desire to explore? Where everyone gets a good education? How can we expect alien races to collaborate with us when we can’t even get along with people who disagree about taxation and the purpose of government?

I’ve gotten over it though, by thinking about it as an aspirational exercise. Not everything has to be pragmatic. And it probably helps to have goals that we can’t quite imagine reaching.

For those of you who are with me, and love everything about the Star Trek franchise, please consider joining me soon for the new Star Trek movie that’s coming out today. Showtimes in NYC are here. See you soon!

Salt it up, baby!

An article in yesterday’s Science Times explained that limiting the salt in your diet doesn’t actually improve health, and could in fact be bad for you. That’s a huge turn-around for a public health rule that has run very deep.

How can this kind of thing happen?

Well, first of all epidemiologists use crazy models to make predictions on things, and in this case what happened was they saw a correlation between high blood pressure and high salt intake, and they saw a separate correlation between high blood pressure and death, and so they linked the two.

Trouble is, while very low salt intake might lower blood pressure a little bit, it also for what ever reason makes people die a wee bit more often.

As this Scientific American article explains, that “little bit” is actually really small:

Over the long-term, low-salt diets, compared to normal diets, decreased systolic blood pressure (the top number in the blood pressure ratio) in healthy people by 1.1 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) by 0.6 mmHg. That is like going from 120/80 to 119/79. The review concluded that “intensive interventions, unsuited to primary care or population prevention programs, provide only minimal reductions in blood pressure during long-term trials.” A 2003 Cochrane review of 57 shorter-term trials similarly concluded that “there is little evidence for long-term benefit from reducing salt intake.”

Moreover, some people react to changing their salt intake with higher, and some with lower blood pressure. Turns out it’s complicated.

I’m a skeptic, especially when it comes to epidemiology. None of this surprises me, and I don’t think it’s the last bombshell we’ll be hearing. But this meta-analysis also might have flaws, so hold your breath for the next pronouncement.

One last thing – they keep saying that it’s too expensive to do this kind of study right, but I’m thinking that by now they might realize the real cost of not doing it right is a loss of the public’s trust in medical research.

SEC Roundtable on credit rating agency models today

I’ve discussed the broken business model that is the credit rating agency system in this country on a few occasions. It directly contributed to the opacity and fraud in the MBS market and to the ensuing financial crisis, for example. And in this post and then this one, I suggest that someone should start an open source version of credit rating agencies. Here’s my explanation:

The system of credit ratings undermines the trust of even the most fervently pro-business entrepreneur out there. The models are knowingly games by both sides, and it’s clearly both corrupt and important. It’s also a bipartisan issue: Republicans and Democrats alike should want transparency when it comes to modeling downgrades- at the very least so they can argue against the results in a factual way. There’s no reason I can see why there shouldn’t be broad support for a rule to force the ratings agencies to make their models publicly available. In other words, this isn’t a political game that would score points for one side or the other.

Well, it wasn’t long before Marc Joffe, who had started an open source credit rating agency, contacted me and came to my Occupy group to explain his plan, which I blogged about here. That was almost a year ago.

Today the SEC is going to have something they’re calling a Credit Ratings Roundtable. This is in response to an amendment that Senator Al Franken put on Dodd-Frank which requires the SEC to examine the credit rating industry. From their webpage description of the event:

The roundtable will consist of three panels:

- The first panel will discuss the potential creation of a credit rating assignment system for asset-backed securities.

- The second panel will discuss the effectiveness of the SEC’s current system to encourage unsolicited ratings of asset-backed securities.

- The third panel will discuss other alternatives to the current issuer-pay business model in which the issuer selects and pays the firm it wants to provide credit ratings for its securities.

Marc is going to be one of something like 9 people in the third panel. He wrote this op-ed piece about his goal for the panel, a key excerpt being the following:

Section 939A of the Dodd-Frank Act requires regulatory agencies to replace references to NRSRO ratings in their regulations with alternative standards of credit-worthiness. I suggest that the output of a certified, open source credit model be included in regulations as a standard of credit-worthiness.

Just to be clear: the current problem is that not only is there wide-spread gaming, but there’s also a near monopoly by the “big three” credit rating agencies, and for whatever reason that monopoly status has been incredibly well protected by the SEC. They don’t grant “NRSRO” status to credit rating agencies unless the given agency can produce something like 10 letters from clients who will vouch for them providing credit ratings for at least 3 years. You can see why this is a hard business to break into.

The Roundtable was covered yesterday in the Wall Street Journal as well: Ratings Firms Steer Clear of an Overhaul – an unfortunate title if you are trying to be optimistic about the event today. From the WSJ article:

Mr. Franken’s amendment requires the SEC to create a board that would assign a rating firm to evaluate structured-finance deals or come up with another option to eliminate conflicts.

While lawsuits filed against S&P in February by the U.S. government and more than a dozen states refocused unflattering attention on the bond-rating industry, efforts to upend its reliance on issuers have languished, partly because of a lack of consensus on what to do.

I’m just kind of amazed that, given how dirty and obviously broken this industry is, we can’t do better than this. SEC, please start doing your job. How could allowing an open-source credit rating agency hurt our country? How could it make things worse?

WSJ: “When Your Boss Makes You Pay for Being Fat”

Going along with the theme of shaming which I took up yesterday, there was a recent Wall Street Journal article called “When Your Boss Makes You Pay for Being Fat” about new ways employers are trying to “encourage healthy living”, or otherwise described, “save money on benefits”. From the article:

Until recently, Michelin awarded workers automatic $600 credits toward deductibles, along with extra money for completing health-assessment surveys or participating in a nonbinding “action plan” for wellness. It adopted its stricter policy after its health costs spiked in 2012.

Now, the company will reward only those workers who meet healthy standards for blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides and waist size—under 35 inches for women and 40 inches for men. Employees who hit baseline requirements in three or more categories will receive up to $1,000 to reduce their annual deductibles. Those who don’t qualify must sign up for a health-coaching program in order to earn a smaller credit.

A few comments:

- This policy combines the critical characteristics of shaming, namely 1) a complete lack of empathy and 2) the shifting of blame for a problem entirely onto one segment of the population even though the “obesity epidemic” is a poorly understood cultural phenomenon.

- To the extent that there may be push-back against this or similar policies inside the workplace, there will be very little to stop employers from not hiring fat people in the first place.

- Or for that matter, what’s going to stop employers from using people’s full medical profiles (note: by this I mean the unregulated online profile that Acxiom and other companies collect about you and then sell to employers or advertisers for medical stuff – not the official medical records which are regulated) against them in the hiring process? Who owns the new-fangled health analytics models anyway?

- We do that already to poor people by basing their acceptance on credit scores.

When is shaming appropriate?

As a fat person, I’ve dealt with a lot of public shaming in my life. I’ve gotten so used to it, I’m more an observer than a victim most of the time. That’s kind of cool because it allows me to think about it abstractly.

I’ve come up with three dimensions for thinking about this issue.

- When is shame useful?

- When is it appropriate?

- When does it help solve a problem?

Note it can be useful even if it doesn’t help solve a problem – one of the characteristics of shame is that the person doing the shaming has broken off all sense of responsibility for whatever the issue is, and sometimes that’s really the only goal. If the shaming campaign is effective, the shamed person or group is exhibited as solely responsible, and the shamer does not display any empathy. It hasn’t solved a problem but at least it’s clear who’s holding the bag.

The lack of empathy which characterizes shaming behavior makes it very easy to spot. And extremely nasty.

Let’s look at some examples of shaming through this lens:

Useful but not appropriate, doesn’t solve a problem

Example 1) it’s both fat kids and their parents who are to blame for childhood obesity:

Example 2) It’s poor mothers that are to blame for poverty:

These campaigns are not going to solve any problems, but they do seem politically useful – a way of doubling down on the people suffering from problems in our society. Not only will they suffer from them, but they will also be blamed for them.

Inappropriate, not useful, possibly solving a short-term discipline problem

Let’s go back to parenting, which everyone seems to love talking about, if I can go by the number of comments on my recent post in defense of neglectful parenting.

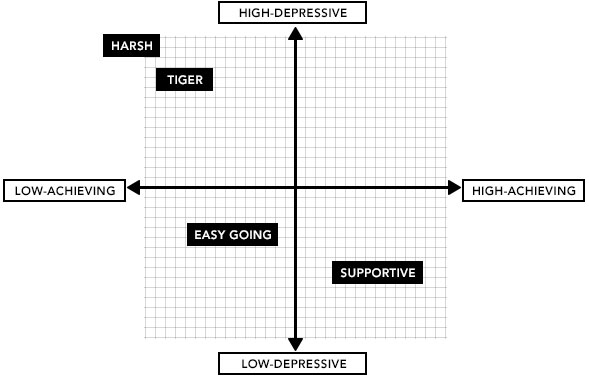

One of my later commenters, Deane, posted this article from Slate about how the Tiger Mom approach to shaming kids into perfection produces depressed, fucked-up kids:

Hey parents: shaming your kids might solve your short-term problem of having independent-minded kids, but it doesn’t lead to long-term confidence and fulfillment.

Appropriate, useful, solves a problem

Here’s when shaming is possibly appropriate and useful and solves a problem: when there have been crimes committed that affect other people needlessly or carelessly, and where we don’t want to let it happen again.

For example, the owner of the Bangladeshi factory which collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people got arrested and publicly shamed. This is appropriate, since he knowingly put people at risk in a shoddy building and added three extra floors to improve his profits.

Note shaming that guy isn’t going to bring back those dead people, but it might prevent other people from doing what he did. In that sense it solves the problem of seemingly nonexistent safety codes in Bangladesh, and to some extent the question of how much we Americans care about cheap clothes versus conditions in factories which make our clothes. Not completely, of course. Update: Major Retailers Join Plan for Greater Safety in Bangladesh

Another example of appropriate shame would be some of the villains of the financial crisis. We in Alt Banking did our best in this regard when we made the 52 Shades of Greed card deck. Here’s Robert Rubin:

Conclusion

I’m no expert on this stuff, but I do have a way of looking at it.

One thing about shame is that the people who actually deserve shame are not particularly susceptible to feeling it (I saw that first hand when I saw Ina Drew in person last month, which I wrote about here). Some people are shameless.

That means that shame, whatever its purpose, is not really about making an individual change their behavior. Shame is really more about setting the rules of society straight: notifying people in general about what’s acceptable and what’s not.

From my perspective, we’ve shown ourselves much more willing to shame poor people, fat people, and our own children than to shame the actual villains who walk among us who deserve such treatment.

Shame on us.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: online dating, probabilistic programming, children, and sex in the teacher’s lounge

Aunt Pythia is yet again gratified to find a few new questions in her inbox this morning, but as usual, she’s running quite low. After reading and enjoying the column below, please consider making some fabricated, melodramatic dilemma up out of whole cloth, preferably combining sex with something nerdy (see below for example) and, more importantly:

Please submit your fake sex question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I met this guy online and we met for three dates. I pinged him to meet up again, but he pleads busyness (he’s an academic, he has grading to do). Thing is, when I go on the dating website, I see that he’s been active–NOT communicating with me. I haven’t heard from him for a week. I sent him a quick, friendly email yesterday in which I did, yes, indicate that I was on the dating site and saw that he was active there. Is this guy a player, blowing me off, or genuinely busy with grading at the end of the semester?

Bewildered in Boston

Dear Bewildered,

I’m afraid that the evidence is pretty good that he’s blowing you off. To prevent this from happening in the future, I have a few suggestions.

Namely, you can’t prevent this kind of thing from happening in the future – not the part where some guy who seems nice blows you off. But you can prevent yourself from caring quite so much and stalking him online (honestly I don’t know why those dating sites allow you to check on other people’s activities. It seems like a recipe for disaster to me).

And the best way to do that is to have a rotation of at least 3 guys that you’re dating at a time, which means being in communication with even more than 3, until one gets serious and sticks. That way you won’t care if one of them is lying to you, and you probably won’t even notice, and it will be more about what you have time to deal with and less about fretting.

By the way, this guy could be genuinely busy and just using a few minutes online to procrastinate between grading papers. But you’ll never find that out if you stress out and send him accusing emails.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m an algebraic topologist trying to learn a bit of data science on the side. Around MIT I’ve heard a tremendous amount of buzz about “probabilistic programming,” mostly focused around its abilities to abstract away fancy mathematics and lower the barrier to entry faced by modelers. I am wondering if you, as a person who often gets her hands dirty with real data, have opinions on the QUERY formalism as espoused here? Are probabilistic programming languages the future of applied machine learning?

Curious Mathematician

Dear Curious,

I’ve never heard of this stuff before you just sent me the link. And I think I probably know why.

You see, the authors have a goal in mind, which is to claim that their work simulates human intelligence. For that they need some kind of sense of randomness, in order to claim they’re simulating creativity or at least some kind of prerequisite for creativity – something in the world of the unexpected.

But in my world, where we use algorithms to help see patterns and make business decisions, it’s kind of the opposite. If anything we want to interpretable algorithms, which we can explain in words. It wouldn’t make sense for us to explain what we’ve implemented and at some point in our explanation say, “… and then we added an element of randomness to the whole thing!”

Actually, that’s not quite true – I can think of one example. Namely, I’ve often thought that as a way of pushing back against the “filter bubble” effect, which I wrote about here, one should get a tailored list of search items plus something totally random. Of course there are plenty of ways to accomplish a random pick. I can only imagine using this for marketing purposes.

Thanks for the link!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I heard that some of the “real” reasons couples choose to have children are peer pressure and boredom. Is that true? I never understood the appeal of children, since they seem to suck the life (and money) out of people for one reason or another.

Tony’s Tentatively-tied Tubes

Dear TT-tT,

I give the same piece of advice to everyone I meet, namely: don’t have children!