Archive

O’Reilly book deal signed for “Doing Data Science”

I’m very happy to say I just signed a book contract with my co-author, Rachel Schutt, to publish a book with O’Reilly called Doing Data Science.

The book will be based on the class Rachel is giving this semester at Columbia which I’ve been blogging about here.

For those of you who’ve been reading along for free as I’ve been blogging it, there might not be a huge incentive to buy it, but I can promise you more and better math, more explicit usable formulas, some sample code, and an overall better and more thought-out narrative.

It’s supposed to be published in May with a possible early release coming up at the end of February, in time for the O’Reilly Strata Santa Clara conference, where Rachel will be speaking about it and about other stuff curriculum related. Hopefully people will pick it up in time to teach their data science courses in Fall 2013.

Speaking of Rachel, she’s also been selected to give a TedXWomen talk at Barnard on December 1st, which is super exciting. She’s talking about advocating for the social good using data. Unfortunately the event is invitation-only, otherwise I’d encourage you all to go and hear her words of wisdom. Update: word on the street is that it will be video-taped.

Columbia Data Science course, week 11: Estimating causal effects

The week in Rachel Schutt’s Data Science course at Columbia we had Ori Stitelman, a data scientist at Media6Degrees.

We also learned last night of a new Columbia course: STAT 4249 Applied Data Science, taught by Rachel Schutt and Ian Langmore. More information can be found here.

Ori’s background

Ori got his Ph.D. in Biostatistics from UC Berkeley after working at a litigation consulting firm. He credits that job with allowing him to understand data through exposure to tons of different data sets; since his job involved creating stories out of data to let experts testify at trials, e.g. for asbestos. In this way Ori developed his data intuition.

Ori worries that people ignore this necessary data intuition when they shove data into various algorithms. He thinks that when their method converges, they are convinced the results are therefore meaningful, but he’s here today to explain that we should be more thoughtful than that.

It’s very important when estimating causal parameters, Ori says, to understand the data-generating distributions and that involves gaining subject matter knowledge that allows you to understand if you necessary assumptions are plausible.

Ori says the first step in a data analysis should always be to take a step back and figure out what you want to know, write that down, and then find and use the tools you’ve learned to answer those directly. Later of course you have to decide how close you came to answering your original questions.

Thought Experiment

Ori asks, how do you know if your data may be used to answer your question of interest? Sometimes people think that because they have data on a subject matter then you can answer any question.

Students had some ideas:

- You need coverage of your parameter space. For example, if you’re studying the relationship between household income and holidays but your data is from poor households, then you can’t extrapolate to rich people. (Ori: but you could ask a different question)

- Causal inference with no timestamps won’t work.

- You have to keep in mind what happened when the data was collected and how that process affected the data itself

- Make sure you have the base case: compared to what? If you want to know how politicians are affected by lobbyists money you need to see how they behave in the presence of money and in the presence of no money. People often forget the latter.

- Sometimes you’re trying to measure weekly effects but you only have monthly data. You end up using proxies. Ori: but it’s still good practice to ask the precise question that you want, then come back and see if you’ve answered it at the end. Sometimes you can even do a separate evaluation to see if something is a good proxy.

- Signal to noise ratio is something to worry about too: as you have more data, you can more precisely estimate a parameter. You’d think 10 observations about purchase behavior is not enough, but as you get more and more examples you can answer more difficult questions.

Ori explains confounders with a dating example

Frank has an important decision to make. He’s perusing a dating website and comes upon a very desirable woman – he wants her number. What should he write in his email to her? Should he tell her she is beautiful? How do you answer that with data?

You could have him select a bunch of beautiful women and half the time chosen at random, tell them they’re beautiful. Being random allows us to assume that the two groups have similar distributions of various features (not that’s an assumption).

Our real goal is to understand the future under two alternative realities, the treated and the untreated. When we randomize we are making the assumption that the treated and untreated populations are alike.

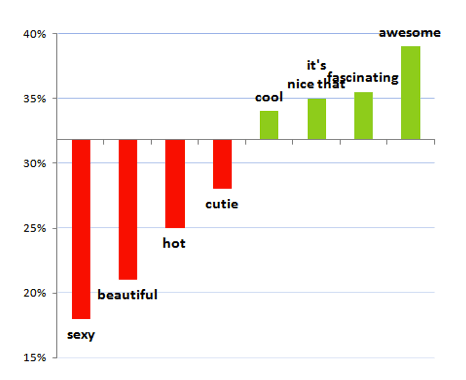

OK Cupid looked at this and concluded:

But note:

- It could say more about the person who says “beautiful” than the word itself. Maybe they are otherwise ridiculous and overly sappy?

- The recipients of emails containing the word “beautiful” might be special: for example, they might get tons of email, which would make it less likely for Frank to get any response at all.

- For that matter, people may be describing themselves as beautiful.

Ori points out that this fact, that she’s beautiful, affects two separate things:

- whether Frank uses the word “beautiful” or not in his email, and

- the outcome (i.e. whether Frank gets the phone number).

For this reason, the fact that she’s beautiful qualifies as a confounder. The treatment is Frank writing “beautiful” in his email.

Causal graphs

Denote by the list of all potential confounders. Note it’s an assumption that we’ve got all of them (and recall how unreasonable this seems to be in epidemiology research).

Denote by the treatment (so, Frank using the word “beautiful” in the email). We usually assume this to have a binary (0/1) outcome.

Denote by the binary (0/1) outcome (Frank getting the number).

We are forming the following causal graph:

In a causal graph, each arrow means that the ancestor is a cause of the descendent, where ancestor is the node the arrow is coming out of and the descendent is the node the arrow is going into (see this book for more).

In our example with Frank, the arrow from beauty means that the woman being beautiful is a cause of Frank writing “beautiful” in the message. Both the man writing “beautiful” and and the woman being beautiful are direct causes of her probability to respond to the message.

Setting the problem up formally

The building blocks in understanding the above causal graph are:

- Ask question of interest.

- Make causal assumptions (denote these by

).

- Translate question into a formal quantity (denote this by

).

- Estimate quantity (denote this by

).

We need domain knowledge in general to do this. We also have to take a look at the data before setting this up, for example to make sure we may make the

Positivity Assumption. We need treatment (i.e. data) in all strata of things we adjust for. So if think gender is a confounder, we need to make sure we have data on women and on men. If we also adjust for age, we need data in all of the resulting bins.

Asking causal questions

What is the effect of ___ on ___?

This is the natural form of a causal question. Here are some examples:

- What is the effect of advertising on customer behavior?

- What is the effect of beauty on getting a phone number?

- What is the effect of censoring on outcome? (censoring is when people drop out of a study)

- What is the effect of drug on time until viral failure?, and the general case

- What is the effect of treatment on outcome?

Look, estimating causal parameters is hard. In fact the effectiveness of advertising is almost always ignored because it’s so hard to measure. Typically people choose metrics of success that are easy to estimate but don’t measure what they want! Everyone makes decision based on them anyway because it’s easier. This results in people being rewarded for finding people online who would have converted anyway.

Accounting for the effect of interventions

Thinking about that, we should be concerned with the effect of interventions. What’s a model that can help us understand that effect?

A common approach is the (randomized) A/B test, which involves the assumption that two populations are equivalent. As long as that assumption is pretty good, which it usually is with enough data, then this is kind of the gold standard.

But A/B tests are not always possible (or they are too expensive to be plausible). Often we need to instead estimate the effects in the natural environment, but then the problem is the guys in different groups are actually quite different from each other.

So, for example, you might find you showed ads to more people who are hot for the product anyway; it wouldn’t make sense to test the ad that way without adjustment.

The game is then defined: how do we adjust for this?

The ideal case

Similar to how we did this last week, we pretend for now that we have a “full” data set, which is to say we have god-like powers and we know what happened under treatment as well as what would have happened if we had not treated, as well as vice-versa, for every agent in the test.

Denote this full data set by

where

denotes the baseline variables (attributes of the agent) as above,

denotes the binary treatment as above,

denotes the binary outcome if treated, and

denotes the binary outcome if untreated.

As a baseline check: if we observed this full data structure how would we measure the effect of A on Y? In that case we’d be all-powerful and we would just calculate:

Note that, since and

are binary, the expected value

is just the probability of a positive outcome if untreated. So in the case of advertising, the above is the conversion rate change when you show someone an ad. You could also take the ratio of the two quantities:

This would be calculating how much more likely someone is to convert if they see an ad.

Note these are outcomes you can really do stuff with. If you know people convert at 30% versus 10% in the presence of an ad, that’s real information. Similarly if they convert 3 times more often.

In reality people use silly stuff like log odds ratios, which nobody understands or can interpret meaningfully.

The ideal case with functions

In reality we don’t have god-like powers, and we have to make do. We will make a bunch of assumptions. First off, denote by exogenous variables, i.e. stuff we’re ignoring. Assume there are functions

and

so that:

i.e. the attributes

are just functions of some exogenous variables,

i.e. the treatment depends in a nice way on some exogenous variables as well the attributes we know about living in

, and

i.e. the outcome is just a function of the treatment, the attributes, and some exogenous variables.

Note the various ‘s could contain confounders in the above notation. That’s gonna change.

But we want to intervene on this causal graph as though it’s the intervention we actually want to make. i.e. what’s the effect of treatment on outcome

?

Let’s look at this from the point of view of the joint distribution These terms correspond to the following in our example:

- the probability of a woman being beautiful,

- the probability that Frank writes and email to a her saying that she’s beautiful, and

- the probability that Frank gets her phone number.

What we really care about though is the distribution under intervention:

i.e. the probability knowing someone either got treated or not. To answer our question, we manipulate the value of first setting it to 1 and doing the calculation, then setting it to 0 and redoing the calculation.

Assumptions

We are making a “Consistency Assumption / SUTVA” which can be expressed like this:

We have also assumed that we have no unmeasured confounders, which can be expressed thus:

We are also assuming positivity, which we discussed above.

Down to brass tacks

We only have half the information we need. We need to somehow map the stuff we have to the full data set as defined above. We make use of the following identity:

Recall we want to estimate which by the above can be rewritten

We’re going to discuss three methods to estimate this quantity, namely:

- MLE-based substitution estimator (MLE),

- Inverse probability estimators (IPTW),

- Double robust estimating equations (A-IPTW)

For the above models, it’s useful to think of there being two machines, called and

, which generate estimates of the probability of the treatment knowing the attributes (that’s machine

) and the probability of the outcome knowing the treatment and the attributes (machine

).

IPTW

In this method, which is also called importance sampling, we weight individuals that are unlikely to be shown an ad more than those likely. In other words, we up-sample in order to generate the distribution, to get the estimation of the actual effect.

To make sense of this, imagine that you’re doing a survey of people to see how they’ll vote, but you happen to do it at a soccer game where you know there are more young people than elderly people. You might want to up-sample the elderly population to make your estimate.

This method can be unstable if there are really small sub-populations that you’re up-sampling, since you’re essentially multiplying by a reciprocal.

The formula in IPTW looks like this:

Note the formula depends on the machine, i.e. the machine that estimates the treatment probability based on attributes. The problem is that people get the

machine wrong all the time, which makes this method fail.

In words, when we are taking the sum of terms whose numerators are zero unless we have a treated, positive outcome, and we’re weighting them in the denominator by the probability of getting treated so each “population” has the same representation. We do the same for

and take the difference.

MLE

This method is based on the machine, which as you recall estimates the probability of a positive outcome given the attributes and the treatment, so the $latex P(Y|A,W)$ values.

This method is straight-forward: shove everyone in the machine and predict how the outcome would look under both treatment and non-treatment conditions, and take difference.

Note we don’t know anything about the underlying machine $latex Q$. It could be a logistic regression.

Get ready to get worried: A-IPTW

What if our machines are broken? That’s when we bring in the big guns: double robust estimators.

They adjust for confounding through the two machines we have on hand, and

and one machine augments the other depending on how well it works. Here’s the functional form written in two ways to illustrate the hedge:

and

Note: you are still screwed if both machines are broken. In some sense with a double robust estimator you’re hedging your bet.

“I’m glad you’re worried because I’m worried too.” – Ori

Simulate and test

I’ve shown you 3 distinct methods that estimate effects in observational studies. But they often come up with different answers. We set up huge simulation studies with known functions, i.e. where we know the functional relationships between everything, and then tried to infer those using the above three methods as well as a fourth method called TMLE (targeted maximal likelihood estimation).

As a side note, Ori encourages everyone to simulate data.

We wanted to know, which methods fail with respect to the assumptions? How well do the estimates work?

We started to see that IPTW performs very badly when you’re adjusting by very small thing. For example we found that the probability of someone getting sick is 132. That’s not between 0 and 1, which is not good. But people use these methods all the time.

Moreover, as things get more complicated with lots of nodes in our causal graph, calculating stuff over long periods of time, populations get sparser and sparser and it has an increasingly bad effect when you’re using IPTW. In certain situations your data is just not going to give you a sufficiently good answer.

Causal analysis in online display advertising

An overview of the process:

- We observe people taking actions (clicks, visits to websites, purchases, etc.).

- We use this observed data to build list of “prospects” (people with a liking for the brand).

- We subsequently observe same user during over the next few days.

- The user visits a site where a display ad spot exists and bid requests are made.

- An auction is held for display spot.

- If the auction is won, we display the ad.

- We observe the user’s actions after displaying the ad.

But here’s the problem: we’ve instituted confounders – if you find people who convert highly they think you’ve done a good job. In other words, we are looking at the treated without looking at the untreated.

We’d like to ask the question, what’s the effect of display advertising on customer conversion?

As a practical concern, people don’t like to spend money on blank ads. So A/B tests are a hard sell.

We performed some what-if analysis stipulated on the assumption that the group of users that sees ad is different. Our process was as follows:

- Select prospects that we got a bid request for on day 0

- Observe if they were treated on day 1. For those treated set

and those not treated set

collect attributes

- Create outcome window to be the next five days following treatment; observe if outcome event occurs (visit to the website whose ad was shown).

- Estimate model parameters using the methods previously described (our three methods plus TMLE).

Here are some results:

Note results vary depending on the method. And there’s no way to know which method is working the best. Moreover, this is when we’ve capped the size of the correction in the IPTW methods. If we don’t then we see ridiculous results:

Data science in the natural sciences

This is a guest post written by Chris Wiggins, crossposted from strata.oreilly.com.

I find myself having conversations recently with people from increasingly diverse fields, both at Columbia and in local startups, about how their work is becoming “data-informed” or “data-driven,” and about the challenges posed by applied computational statistics or big data.

A view from health and biology in the 1990s

In discussions with, as examples, New York City journalists, physicists, or even former students now working in advertising or social media analytics, I’ve been struck by how many of the technical challenges and lessons learned are reminiscent of those faced in the health and biology communities over the last 15 years, when these fields experienced their own data-driven revolutions and wrestled with many of the problems now faced by people in other fields of research or industry.

It was around then, as I was working on my PhD thesis, that sequencing technologies became sufficient to reveal the entire genomes of simple organisms and, not long thereafter, the first draft of the human genome. This advance in sequencing technologies made possible the “high throughput” quantification of, for example,

- the dynamic activity of all the genes in an organism; or

- the set of all protein-protein interactions in an organism; or even

- statistical comparative genomics revealing how small differences in genotype correlate with disease or other phenotypes.

These advances required formation of multidisciplinary collaborations, multi-departmental initiatives, advances in technologies for dealing with massive datasets, and advances in statistical and mathematical methods for making sense of copious natural data.

The fourth paradigm

This shift wasn’t just a series of technological advances in biological research; the more important change was a realization that research in which data vastly outstrip our ability to posit models is qualitatively different. Much of science for the last three centuries advanced by deriving simple models from first principles — models whose predictions could then be compared with novel experiments. In modeling complex systems for which the underlying model is not yet known but for which data are abundant, however, as in systems biology or social network analysis, one may turn this process on its head by using the data to learn not only parameters of a single model but to select which among many or an infinite number of competing models is favored by the data. Just over a half-decade ago, the computer scientist Jim Gray described this as a “fourth paradigm” of science, after experimental, theoretical, and computational paradigms. Gray predicted that every sector of human endeavor will soon emulate biology’s example of identifying data-driven research and modeling as a distinct field.

In the years since then we’ve seen just that. Examples include data-driven social sciences (often leveraging the massive data now available through social networks) and even data-driven astronomy (cf., Astronomy.net). I’ve personally enjoyed seeing many students from Columbia’s School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS), trained in applications of big data to biology, go on to develop and apply data-driven models in these fields. As one example, a recent SEAS PhD student spent a summer as a “hackNY Fellow” applying machine learning methods at the data-driven dating NYC startup OKCupid. [Disclosure: I’m co-founder and co-president of hackNY.] He’s now applying similar methods to population genetics as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. These students, often with job titles like “data scientist,” are able to translate to other fields, or even to the “real world” of industry and technology-driven startups, methods needed in biology and health for making sense of abundant natural data.

Data science: Combining engineering and natural sciences

In my research group, our work balances “engineering” goals, e.g., developing models that can make accurate quantitative predictions, with “natural science” goals, meaning building models that are interpretable to our biology and clinical collaborators, and which suggest to them what novel experiments are most likely to reveal the workings of natural systems. For example:

- We’ve developed machine-learning methods for modeling the expression of genes — the “on-off” state of the tens of thousands of individual processes your cells execute — by combining sequence data with microarray expression data. These models reveal which genes control which other genes, via what important sequence elements.

- We’ve analyzed large biological protein networks and shown how statistical signatures reveal what evolutionary laws can give rise to such graphs.

- In collaboration with faculty at Columbia’s chemistry department and NYU’s medical school, we’ve developed hierarchical Bayesian inference methods that can automate the analysis of thousands of time series data from single molecules. These techniques can identify the best model from models of varying complexity, along with the kinetic and biophysical parameters of interest to the chemist and clinician.

- Our current projects include, in collaboration with experts at Columbia’s medical school in pathogenic viral genomics, using machine learning methods to reveal whether a novel viral sequence may be carcinogenic or may lead to a pandemic. This research requires an abundant corpus of training data as well as close collaboration with the domain experts to ensure that the models exploit — and are interpretable in light of — the decades of bench work that has revealed what we now know of viral pathogenic mechanisms.

Throughout, our goals balance building models that are not only predictive but interpretable, e.g., revealing which sequence elements convey carcinogenicity or permit pandemic transmissibility.

Data science in health

More generally, we can apply big data approaches not only to biological examples as above but also to health data and health records. These approaches offer the possibility of, for example, revealing unknown lethal drug-drug interactions or forecasting future patient health problems; such models could have consequences for both public health policies and individual patent care. As one example, the Heritage Health Prize is a $3 million challenge ending in April 2013 “to identify patients who will be admitted to a hospital within the next year, using historical claims data.” Researchers at Columbia, both in SEAS and at Columbia’s medical school, are building the technologies needed for answering such big questions from big data.

The need for skilled data scientists

In 2011, the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that between 140,000 and 190,000 additional data scientistswill need to be trained by 2018 in order to meet the increased demand in academia and industry in the United States alone. The multidisciplinary skills required for data science applied to such fields as health and biology will include:

- the computational skills needed to work with large datasets usually shared online;

- the ability to format these data in a way amenable to mathematical modeling;

- the curiosity to explore these data to identify what features our models may be built on;

- the technical skills which apply, extend, and validate statistical and machine learning methods; and most importantly,

- the ability to visualize, interpret, and communicate the resulting insights in a way which advances science. (As the mathematician Richard Hamming said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers.”)

More than a decade ago the statistician William Cleveland, then at Bell Labs, coined the term “data science” for this multidisciplinary set of skills and envisioned a future in which these skills would be needed for more fields of technology. The term has had a recent explosion in usage as more and more fields — both in academia and in industry — are realizing precisely this future.

Medical research needs an independent modeling panel

I am outraged this morning.

I spent yesterday morning writing up David Madigan’s lecture to us in the Columbia Data Science class, and I can hardly handle what he explained to us: the entire field of epidemiological research is ad hoc.

This means that people are taking medication or undergoing treatments that may do they harm and probably cost too much because the researchers’ methods are careless and random.

Of course, sometimes this is intentional manipulation (see my previous post on Vioxx, also from an eye-opening lecture by Madigan). But for the most part it’s not. More likely it’s mostly caused by the human weakness for believing in something because it’s standard practice.

In some sense we knew this already. How many times have we read something about what to do for our health, and then a few years later read the opposite? That’s a bad sign.

And although the ethics are the main thing here, the money is a huge issue. It required $25 million dollars for Madigan and his colleagues to implement the study on how good our current methods are at detecting things we already know. Turns out they are not good at this – even the best methods, which we have no reason to believe are being used, are only okay.

Okay, $25 million dollars is a lot, but then again there are literally billions of dollars being put into the medical trials and research as a whole, so you might think that the “due diligence” of such a large industry would naturally get funded regularly with such sums.

But you’d be wrong. Because there’s no due diligence for this industry, not in a real sense. There’s the FDA, but they are simply not up to the task.

One article I linked to yesterday from the Stanford Alumni Magazine, which talked about the work of John Ioannidis (I blogged about his work here called “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False“), summed the situation up perfectly (emphasis mine):

When it comes to the public’s exposure to biomedical research findings, another frustration for Ioannidis is that “there is nobody whose job it is to frame this correctly.” Journalists pursue stories about cures and progress—or scandals—but they aren’t likely to diligently explain the fine points of clinical trial bias and why a first splashy result may not hold up. Ioannidis believes that mistakes and tough going are at the essence of science. “In science we always start with the possibility that we can be wrong. If we don’t start there, we are just dogmatizing.”

It’s all about conflict of interest, people. The researchers don’t want their methods examined, the pharmaceutical companies are happy to have various ways to prove a new drug “effective”, and the FDA is clueless.

Another reason for an AMS panel to investigate public math models. If this isn’t in the public’s interest I don’t know what is.

Columbia Data Science course, week 10: Observational studies, confounders, epidemiology

This week our guest lecturer in the Columbia Data Science class was David Madigan, Professor and Chair of Statistics at Columbia. He received a bachelors degree in Mathematical Sciences and a Ph.D. in Statistics, both from Trinity College Dublin. He has previously worked for AT&T Inc., Soliloquy Inc., the University of Washington, Rutgers University, and SkillSoft, Inc. He has over 100 publications in such areas as Bayesian statistics, text mining, Monte Carlo methods, pharmacovigilance and probabilistic graphical models.

So Madigan is an esteemed guest, but I like to call him an “apocalyptic leprechaun”, for reasons which you will know by the end of this post. He’s okay with that nickname, I asked his permission.

Madigan came to talk to us about observation studies, of central importance in data science. He started us out with this:

Thought Experiment

We now have detailed, longitudinal medical data on tens of millions of patients. What can we do with it?

To be more precise, we have tons of phenomenological data: this is individual, patient-level medical record data. The largest of the databases has records on 80 million people: every prescription drug, every condition ever diagnosed, every hospital or doctor’s visit, every lab result, procedures, all timestamped.

But we still do things like we did in the Middle Ages; the vast majority of diagnosis and treatment is done in a doctor’s brain. Can we do better? Can you harness these data to do a better job delivering medical care?

Students responded:

1) There was a prize offered on Kaggle, called “Improve Healthcare, Win $3,000,000.” predicting who is going to go to the hospital next year. Doesn’t that give us some idea of what we can do?

Madigan: keep in mind that they’ve coarsened the data for proprietary reasons. Hugely important clinical problem, especially as a healthcare insurer. Can you intervene to avoid hospitalizations?

2) We’ve talked a lot about the ethical uses of data science in this class. It seems to me that there are a lot of sticky ethical issues surrounding this 80 million person medical record dataset.

Madigan: Agreed! What nefarious things could we do with this data? We could gouge sick people with huge premiums, or we could drop sick people from insurance altogether. It’s a question of what, as a society, we want to do.

What is modern academic statistics?

Madigan showed us Drew Conway’s Venn Diagram that we’d seen in week 1:

Madigan positioned the modern world of the statistician in the green and purple areas.

Madigan positioned the modern world of the statistician in the green and purple areas.

It used to be the case, say 20 years ago, according to Madigan, that academic statistician would either sit in their offices proving theorems with no data in sight (they wouldn’t even know how to run a t-test) or sit around in their offices and dream up a new test, or a new way of dealing with missing data, or something like that, and then they’d look around for a dataset to whack with their new method. In either case, the work of an academic statistician required no domain expertise.

Nowadays things are different. The top stats journals are more deep in terms of application areas, the papers involve deep collaborations with people in social sciences or other applied sciences. Madigan is setting an example tonight by engaging with the medical community.

Madigan went on to make a point about the modern machine learning community, which he is or was part of: it’s a newish academic field, with conferences and journals, etc., but is characterized by what stats was 20 years ago: invent a method, try it on datasets. In terms of domain expertise engagement, it’s a step backwards instead of forwards.

Comments like the above make me love Madigan.

Very few academic statisticians have serious hacking skills, with Mark Hansen being an unusual counterexample. But if all three is what’s required to be called data science, then I’m all for data science, says Madigan.

Madigan’s timeline

Madigan went to college in 1980, specialized on day 1 on math for five years. In final year, he took a bunch of stats courses, and learned a bunch about computers: pascal, OS, compilers, AI, database theory, and rudimentary computing skills. Then came 6 years in industry, working at an insurance company and a software company where he specialized in expert systems.

It was a mainframe environment, and he wrote code to price insurance policies using what would now be described as scripting languages. He also learned about graphics by creating a graphic representation of a water treatment system. He learned about controlling graphics cards on PC’s, but he still didn’t know about data.

Then he got a Ph.D. and went into academia. That’s when machine learning and data mining started, which he fell in love with: he was Program Chair of the KDD conference, among other things, before he got disenchanted. He learned C and java, R and S+. But he still wasn’t really working with data yet.

He claims he was still a typical academic statistician: he had computing skills but no idea how to work with a large scale medical database, 50 different tables of data scattered across different databases with different formats.

In 2000 he worked for AT&T labs. It was an “extreme academic environment”, and he learned perl and did lots of stuff like web scraping. He also learned awk and basic unix skills.

It was life altering and it changed everything: having tools to deal with real data rocks! It could just as well have been python. The point is that if you don’t have the tools you’re handicapped. Armed with these tools he is afraid of nothing in terms of tackling a data problem.

In Madigan’s opinion, statisticians should not be allowed out of school unless they know these tools.

He then went to a internet startup where he and his team built a system to deliver real-time graphics on consumer activity.

Since then he’s been working in big medical data stuff. He’s testified in trials related to medical trials, which was eye-opening for him in terms of explaining what you’ve done: “If you’re gonna explain logistical regression to a jury, it’s a different kind of a challenge than me standing here tonight.” He claims that super simple graphics help.

Carrotsearch

As an aside he suggests we go to this website, called carrotsearch, because there’s a cool demo on it.

What is an observational study?

Madigan defines it for us:

An observational study is an empirical study in which the objective is to elucidate cause-and-effect relationships in which it is not feasible to use controlled experimentation.

In tonight’s context, it will involve patients as they undergo routine medical care. We contrast this with designed experiment, which is pretty rare. In fact, Madigan contends that most data science activity revolves around observational data. Exceptions are A/B tests. Most of the time, the data you have is what you get. You don’t get to replay a day on the market where Romney won the presidency, for example.

Observational studies are done in contexts in which you can’t do experiments, and they are mostly intended to elucidate cause-and-effect. Sometimes you don’t care about cause-and-effect, you just want to build predictive models. Madigan claims there are many core issues in common with the two.

Here are some examples of tests you can’t run as designed studies, for ethical reasons:

- smoking and heart disease (you can’t randomly assign someone to smoke)

- vitamin C and cancer survival

- DES and vaginal cancer

- aspirin and mortality

- cocaine and birthweight

- diet and mortality

Pitfall #1: confounders

There are all kinds of pitfalls with observational studies.

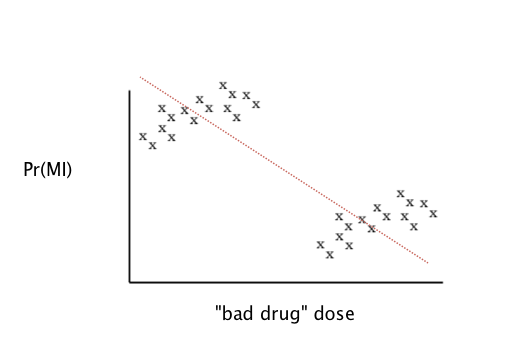

For example, look at this graph, where you’re finding a best fit line to describe whether taking higher doses of the “bad drug” is correlated to higher probability of a heart attack:

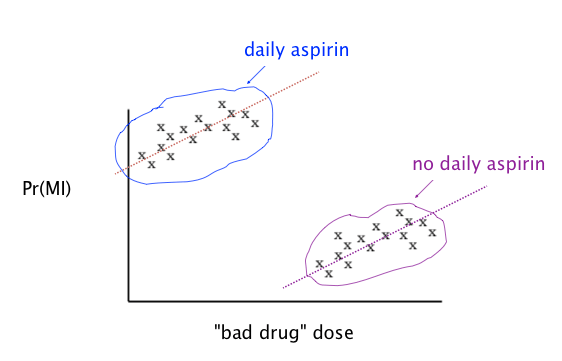

It looks like, from this vantage point, the more drug you take the fewer heart attacks you have. But there are two clusters, and if you know more about those two clusters, you find the opposite conclusion:

Note this picture was rigged it so the issue is obvious. This is an example of a “confounder.” In other words, the aspirin-taking or non-aspirin-taking of the people in the study wasn’t randomly distributed among the people, and it made a huge difference.

It’s a general problem with regression models on observational data. You have no idea what’s going on.

Madigan: “It’s the wild west out there.”

Wait, and it gets worse. It could be the case that within each group there males and females and if you partition by those you see that the more drugs they take the better again. Since a given person either is male or female, and either takes aspirin or doesn’t, this kind of thing really matters.

This illustrates the fundamental problem in observational studies, which is sometimes called Simpson’s Paradox.

[Remark from someone in the class: if you think of the original line as a predictive model, it’s actually still the best model you can obtain knowing nothing more about the aspirin-taking habits or genders of the patients involved. The issue here is really that you’re trying to assign causality.]

The medical literature and observational studies

As we may not be surprised to hear, medical journals are full of observational studies. The results of these studies have a profound effect on medical practice, on what doctors prescribe, and on what regulators do.

For example, in this paper, entitled “Oral bisphosphonates and risk of cancer of oesophagus, stomach, and colorectum: case-control analysis within a UK primary care cohort,” Madigan report that we see the very same kind of confounding problem as in the above example with aspirin. The conclusion of the paper is that the risk of cancer increased with 10 or more prescriptions of oral bisphosphonates.

It was published on the front page of new york times, the study was done by a group with no apparent conflict of interest and the drugs are taken by millions of people. But the results were wrong.

There are thousands of examples of this, it’s a major problem and people don’t even get that it’s a problem.

Randomized clinical trials

One possible way to avoid this problem is randomized studies. The good news is that randomization works really well: because you’re flipping coins, all other factors that might be confounders (current or former smoker, say) are more or less removed, because I can guarantee that smokers will be fairly evenly distributed between the two groups if there are enough people in the study.

The truly brilliant thing about randomization is that randomization matches well on the possible confounders you thought of, but will also give you balance on the 50 million things you didn’t think of.

So, although you can algorithmically find a better split for the ones you thought of, that quite possible wouldn’t do as well on the other things. That’s why we really do it randomly, because it does quite well on things you think of and things you don’t.

But there’s bad news for randomized clinical trials as well. First off, it’s only ethically feasible if there’s something called clinical equipoise, which means the medical community really doesn’t know which treatment is better. If you know have reason to think treating someone with a drug will be better for them than giving them nothing, you can’t randomly not give people the drug.

The other problem is that they are expensive and cumbersome. It takes a long time and lots of people to make a randomized clinical trial work.

In spite of the problems, randomized clinical trials are the gold standard for elucidating cause-and-effect relationships.

Rubin causal model

The Rubin causal model is a mathematical framework for understanding what information we know and don’t know in observational studies.

It’s meant to investigate the confusion when someone says something like “I got lung cancer because I smoked”. Is that true? If so, you’d have to be able to support the statement, “If I hadn’t smoked I wouldn’t have gotten lung cancer,” but nobody knows that for sure.

Define:

to be the treatment applied to unit

(0 = control, 1= treatment),

to be the response for unit

if

,

to be the response for unit

if

.

Then the unit level causal effect is , but we only see one of

and

Example: is 1 if I smoked, 0 if I didn’t (I am the unit).

is 1 or 0 if I got cancer and I smoked, and

is 1 or 0 depending on whether I got cancer while not smoking. The overall causal effect on me is the difference

This is equal to 1 if I got really got cancer because I smoked, it’s 0 if I got cancer (or didn’t) independent of smoking, and it’s -1 if I avoided cancer by smoking. But I’ll never know my actual value since I only know one term out of the two.

Of course, on a population level we do know how to infer that there are quite a few “1”‘s among the population, but we will never be able to assign a given individual that number.

This is sometimes called the fundamental problem of causal inference.

Confounding and Causality

Let’s say we have a population of 100 people that takes some drug, and we screen them for cancer. Say 30 out of them get cancer, which gives them a cancer rate of 0.30. We want to ask the question, did the drug cause the cancer?

To answer that, we’d have to know what would’ve happened if they hadn’t taken the drug. Let’s play God and stipulate that, had they not taken the drug, we would have seen 20 get cancer, so a rate of 0.20. We typically say the causal effect is the ration of these two numbers (i.e. the increased risk of cancer), so 1.5.

But we don’t have God’s knowledge, so instead we choose another population to compare this one to, and we see whether they get cancer or not, whilst not taking the drug. Say they have a natural cancer rate of 0.10. Then we would conclude, using them as a proxy, that the increased cancer rate is the ratio 0.30 to 0.10, so 3. This is of course wrong, but the problem is that the two populations have some underlying differences that we don’t account for.

If these were the “same people”, down to the chemical makeup of each other molecules, this “by proxy” calculation would work of course.

The field of epidemiology attempts to adjust for potential confounders. The bad news is that it doesn’t work very well. One reason is that they heavily rely on stratification, which means partitioning the cases into subcases and looking at those. But there’s a problem here too.

Stratification can introduce confounding.

The following picture illustrates how stratification could make the underlying estimates of the causal effects go from good to bad:

In the top box, the values of b and c are equal, so our causal effect estimate is correct. However, when you break it down by male and female, you get worse estimates of causal effects.

The point is, stratification doesn’t just solve problems. There are no guarantees your estimates will be better if you stratify and all bets are off.

What do people do about confounding things in practice?

In spite of the above, experts in this field essentially use stratification as a major method to working through studies. They deal with confounding variables by essentially stratifying with respect to them. So if taking aspirin is believed to be a potential confounding factor, they stratify with respect to it.

For example, with this study, which studied the risk of venous thromboembolism from the use of certain kinds of oral contraceptives, the researchers chose certain confounders to worry about and concluded the following:

After adjustment for length of use, users of oral contraceptives were at least twice the risk of clotting compared with user of other kinds of oral contraceptives.

This report was featured on ABC, and it was a big hoo-ha.

Madigan asks: wouldn’t you worry about confounding issues like aspirin or something? How do you choose which confounders to worry about? Wouldn’t you worry that the physicians who are prescribing them are different in how they prescribe? For example, might they give the newer one to people at higher risk of clotting?

Another study came out about this same question and came to a different conclusion, using different confounders. They adjusted for a history of clots, which makes sense when you think about it.

This is an illustration of how you sometimes forget to adjust for things, and the outputs can then be misleading.

What’s really going on here though is that it’s totally ad hoc, hit or miss methodology.

Another example is a study on oral bisphosphonates, where they adjusted for smoking, alcohol, and BMI. But why did they choose those variables?

There are hundreds of examples where two teams made radically different choices on parallel studies. We tested this by giving a bunch of epidemiologists the job to design 5 studies at a high level. There was zero consistency. And an addition problem is that luminaries of the field hear this and say: yeah yeah yeah but I would know the right way to do it.

Is there a better way?

Madigan and his co-authors examined 50 studies, each of which corresponds to a drug and outcome pair, e.g. antibiotics with GI bleeding.

They ran about 5,000 analyses for every pair. Namely, they ran every epistudy imaginable on, and they did this all on 9 different databases.

For example, they looked at ACE inhibitors (the drug) and swelling of the heart (outcome). They ran the same analysis on the 9 different standard databases, the smallest of which has records of 4,000,000 patients, and the largest of which has records of 80,000,000 patients.

In this one case, for one database the drug triples the risk of heart swelling, but for another database it seems to have a 6-fold increase of risk. That’s one of the best examples, though, because at least it’s always bad news – it’s consistent.

On the other hand, for 20 of the 50 pairs, you can go from statistically significant in one direction (bad or good) to the other direction depending on the database you pick. In other words, you can get whatever you want. Here’s a picture, where the heart swelling example is at the top:

Note: the choice of database is never discussed in any of these published epidemiology papers.

Next they did an even more extensive test, where they essentially tried everything. In other words, every time there was a decision to be made, they did it both ways. The kinds of decisions they tweaker were of the following types: which database you tested on, the confounders you accounted for, the window of time you care about examining (spoze they have a heart attack a week after taking the drug, is it counted? 6 months?)

What they saw was that almost all the studies can get either side depending on the choices.

Final example, back to oral bisphosphonates. A certain study concluded that it causes esophageal cancer, but two weeks later JAMA published a paper on same issue which concluded it is not associated to elevated risk of esophageal cancer. And they were even using the same database. This is not so surprising now for us.

OMOP Research Experiment

Here’s the thing. Billions upon billions of dollars are spent doing these studies. We should really know if they work. People’s lives depend on it.

Madigan told us about his “OMOP 2010.2011 Research Experiment”

They took 10 large medical databases, consisting of a mixture of claims from insurance companies and EHR (electronic health records), covering records of 200 million people in all. This is big data unless you talk to an astronomer.

They mapped the data to a common data model and then they implemented every method used in observational studies in healthcare. Altogether they covered 14 commonly used epidemiology designs adapted for longitudinal data. They automated everything in sight. Moreover, there were about 5000 different “settings” on the 14 methods.

The idea was to see how well the current methods do on predicting things we actually already know.

To locate things they know, they took 10 old drug classes: ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, warfarin, etc., and 10 outcomes of interest: renal failure, hospitalization, bleeding, etc.

For some of these the results are known. So for example, warfarin is a blood thinner and definitely causes bleeding. There were 9 such known bad effects.

There were also 44 known “negative” cases, where we are super confident there’s just no harm in taking these drugs, at least for these outcomes.

The basic experiment was this: run 5000 commonly used epidemiological analyses using all 10 databases. How well do they do at discriminating between reds and blues?

This is kind of like a spam filter test. We have training emails that are known spam, and you want to know how well the model does at detecting spam when it comes through.

Each of the models output the same thing: a relative risk (causal effect estimate) and an error.

This was an attempt to empirically evaluate how well does epidemiology work, kind of the quantitative version of John Ioannidis’s work. we did the quantitative thing to show he’s right.

Why hasn’t this been done before? There’s conflict of interest for epidemiology – why would they want to prove their methods don’t work? Also, it’s expensive, it cost $25 million dollars (of course that pales in comparison to the money being put into these studies). They bought all the data, made the methods work automatically, and did a bunch of calculations in the Amazon cloud. The code is open source.

In the second version, we zeroed in on 4 particular outcomes. Here’s the $25,000,000 ROC curve:

To understand this graph, we need to define a threshold, which we can start with at 2. This means that if the relative risk is estimated to be above 2, we call it a “bad effect”, otherwise call it a “good effect.” The choice of threshold will of course matter.

If it’s high, say 10, then you’ll never see a 10, so everything will be considered a good effect. Moreover these are old drugs and it wouldn’t be on the market. This means your sensitivity will be low, and you won’t find any real problem. That’s bad! You should find, for example, that warfarin causes bleeding.

There’s of course good news too, with low sensitivity, namely a zero false-positive rate.

What if you set the threshold really low, at -10? Then everything’s bad, and you have a 100% sensitivity but very high false positive rate.

As you vary the threshold from very low to very high, you sweep out a curve in terms of sensitivity and false-positive rate, and that’s the curve we see above. There is a threshold (say 1.8) for which your false positive rate is 30% and your sensitivity is 50%.

This graph is seriously problematic if you’re the FDA. A 30% false-positive rate is out of control. This curve isn’t good.

The overall “goodness” of such a curve is usually measured as the area under the curve: you want it to be one, and if your curve lies on diagonal the area is 0.5. This is tantamount to guessing randomly. So if your area under the curve is less than 0.5, it means your model is perverse.

The area above is 0.64. Moreover, of the 5000 analysis we ran, this is the single best analysis.

But note: this is the best if I can only use the same method for everything. In that case this is as good as it gets, and it’s not that much better than guessing.

But no epidemiology would do that!

So what they did next was to specialize the analysis to the database and the outcome. And they got better results: for the medicare database, and for acute kidney injury, their optimal model gives them an AUC of 0.92. They can achieve 80% sensitivity with a 10% false positive rate.

They did this using a cross-validation method. Different databases have different methods attached to them. One winning method is called “OS”, which compares within a given patient’s history (so compares times when patient was on drugs versus when they weren’t). This is not widely used now.

The epidemiologists in general don’t believe the results of this study.

If you go to http://elmo/omop.org, you can see the AUM for a given database and a given method.

Note the data we used was up to mid-2010. To update this you’d have to get latest version of database, and rerun the analysis. Things might have changed.

Moreover, an outcome for which nobody has any idea on what drugs cause what outcomes you’re in trouble. This only applies to when we have things to train on where we know the outcome pretty well.

Parting remarks

Keep in mind confidence intervals only account for sampling variability. They don’t capture bias at all. If there’s bias, the confidence interval or p-value can be meaningless.

What about models that epidemiologists don’t use? We have developed new methods as well (SCCS). we continue to do that, but it’s a hard problem.

Challenge for the students: we ran 5000 different analyses. Is there a good way of combining them to do better? weighted average? voting methods across different strategies?

Note the stuff is publicly available and might make a great Ph.D. thesis.

The zit model

When my mom turned 42, I was 12 and a total wise-ass. For her present I bought her a coffee mug that had on it the phrase “Things could be worse. You could be old and still have zits”, to tease her about her bad skin. Considering how obnoxious that was, she took it really well and drank out of the mug for years.

Well, I’m sure you can all see where this is going. I’m now 40 and I have zits. I was contemplating this in the bath yesterday, wondering if I’d ever get rid of my zits and wondering if taking long hot baths helps or not. They come and go, so it seems vaguely controllable.

Then I had a thought: well, I could collect data and see what helps. After all, I don’t always have zits. I could keep a diary of all the things that I think might affect the situation: what I eat (I read somewhere that eating cheese makes you have zits), how often I take baths vs. showers, whether I use zit cream, my hormones, etc. and certainly whether or not I have zits on a given day or not.

The first step would be to do some research on the theories people have about what causes zits, and then set up a spreadsheet where I could efficiently add my daily data. Maybe a google form! I’m wild about google forms.

After collecting this data for some time I could build a model which tries to predict zittage, to see which of those many inputs actually have signal for my personal zit model.

Of course I expect a lag between the thing I do or eat or use and the actual resulting zit, and I don’t know what that lag is (do you get zits the day after you eat cheese? or three days after eating cheese?), so I’ll expect some difficulty with this or even over fitting.

Even so, this just might work!

Then I immediately felt tired because, if you think about spending your day collecting information like that about your potential zits, then you must be totally nuts.

I mean, I can imagine doing it just for fun, or to prove a point, or on a dare (there are few things I won’t do on a dare), but when it comes down to it I really don’t care that much about my zits.

Then I started thinking about technology and how it could help me with my zit model. I mean, you know about those bracelets you can wear that count your steps and then automatically record them on your phone, right? Well, how long until those bracelets can be trained to collect any kind of information you can imagine?

- Baths? No problem. I’m sure they can detect moisture and heat.

- Cheese eating? Maybe you’d have to say out loud what you’re eating, but again not a huge problem.

- Hormones? I have no idea but let’s stipulate plausible: they already have an ankle bracelet that monitors blood alcohol levels.

- Whether you have zits? Hmmm. Let’s say you could add any variable you want with voice command.

In other words, in 5 years this project will be a snap when I have my handy dandy techno bracelet which collects all the information I want. And maybe whatever other information as well, because information storage is cheap. I’ll have a bounty of data for my zit model.

This is exciting stuff. I’m looking forward to building the definitive model, from which I can conclude that eating my favorite kind of cheese does indeed give me zits. And I’ll say to myself, worth it!

Columbia Data Science course, week 9: Morningside Analytics, network analysis, data journalism

Our first speaker this week in Rachel Schutt‘s Columbia Data Science course was John Kelly from Morningside Analytics, who came to talk to us about network analysis.

John Kelly

Kelly has four diplomas from Columbia, starting with a BA in 1990 from Columbia College, followed by a Masters, MPhil and Ph.D. in Columbia’s school of Journalism. He explained that studying communications as a discipline can mean lots of things, but he was interested in network sociology and statistics in political science.

Kelly spent a couple of terms at Stanford learning survey design and game theory and other quanty stuff. He describes the Columbia program in communications as a pretty DIY set-up, where one could choose to focus on the role of communication in society, the impact of press, impact of information flow, or other things. Since he was interested in quantitative methods, he hunted them down, doing his master’s thesis work with Marc Smith from Microsoft. He worked on political discussions and how they evolve as networks (versus other kinds of discussions).

After college and before grad school, Kelly was an artist, using computers to do sound design. He spent 3 years as the Director of Digital Media here at Columbia School of the Arts.

Kelly taught himself perl and python when he spent a year in Viet Nam with his wife.

Kelly’s profile

Kelly spent quite a bit of time describing how he sees math, statistics, and computer science (including machine learning) as tools he needs to use and be good at in order to do what he really wants to do.

But for him the good stuff is all about domain expertise. He want to understand how people come together, and when they do, what is their impact on politics and public policy. His company Morningside Analytics has clients like think tanks and political organizations and want to know how social media affects and creates politics. In short, Kelly wants to understand society, and the math and stats allows him to do that.

Communication and presentations are how he makes money, so that’s important, and visualizations are integral to both domain expertise and communications, so he’s essentially a viz expert. As he points out, Morningside Analytics doesn’t get paid to just discover interesting stuff, but rather to help people use it.

Whereas a company such SocialFlow is venture funded, which means you can run a staff even if you don’t make money, Morningside is bootstrapped. It’s a different life, where we eat what we sow.

Case-attribute data vs. social network data

Kelly has a strong opinion about standard modeling through case-attribute data, which is what you normally see people feed to models with various “cases” (think people) who have various “attributes” (think age, or operating system, or search histories).

Maybe because it’s easy to store in databases or because it’s easy to collect this kind of data, there’s been a huge bias towards modeling with case-attribute data.

Kelly thinks it’s missing the point of the questions we are trying to answer nowadays. It started, he said, in the 1930’s with early market research, and it was soon being applied applied to marketing as well as politicals.

He named Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz as trailblazing sociologists who came here from Europe and developed the field of social network analysis. This is a theory based not only on individual people but also the relationships between them.

We could do something like this for the attributes of a data scientist, and we might have an arrow point from math to stats if we think math “underlies” statistics in some way. Note the arrows don’t always mean the same thing, though, and when you specify a network model to test a theory it’s important you make the arrows well-defined.

To get an idea of why network analysis is superior to case-attribute data analysis, think about this. The federal government spends money to poll people in Afghanistan. The idea is to see what citizens want and think to determine what’s going to happen in the future. But, Kelly argues, what’ll happen there isn’t a function of what individuals think, it’s a question of who has the power and what they think.

Similarly, imagine going back in time and conducting a scientific poll of the citizenry of Europe in 1750 to determine the future politics. If you knew what you were doing you’d be looking at who’s marrying who among the royalty.

In some sense the current focus on case-attribute data is a problem of what’s “under the streetlamp” – people are used to doing it that way.

Kelly wants us to consider what he calls the micro/macro (i.e. individual versus systemic) divide: when it comes to buying stuff, or voting for a politician in a democracy, you have a formal mechanism for bridging the micro/macro divide, namely markets for buying stuff and elections for politicians. But most of the world doesn’t have those formal mechanisms, or indeed they have a fictive shadow of those things. For the most part we need to know enough about the actual social network to know who has the power and influence to bring about change.

Kelly claims that the world is a network much more than it’s a bunch of cases with attributes. For example, if you only understand how individuals behave, how do you tie things together?

History of social network analysis

Social network analysis basically comes from two places: graph theory, where Euler solved the Seven Bridges of Konigsberg problem, and sociometry, started by Jacob Moreno in the 1970’s, just as early computers got good at making large-scale computations on large data sets.

Social network analysis was germinated by Harrison White, emeritus at Columbia (emeritus), contemporaneously with Columbia sociologist Robert Merton. Their essential idea was that people’s actions have to be related to their attributes, but to really understand them you also need to look at the networks that enable them to do something.

Core entities for network models

Kelly gave us a bit of terminology from the world of social networks:

- actors (or nodes in graph theory speak): these can be people, or websites, or what have you

- relational ties (edges in graph theory speak): for example, an instance of liking someone or being friends

- dyads: pairs of actors

- triads: triplets of actors; there are for example, measures of triadic closure in networks

- subgroups: a subset of the whole set of actors, along with their relational ties

- group: the entirety of a “network”, easy in the case of Twitter but very hard in the case of e.g. “liberals”

- relation: for example, liking another person

- social network: all of the above

Types of Networks

There are different types of social networks.

For example, in one-node networks, the simplest case, you have a bunch of actors connected by ties. This is a construct you’d use to display a Facebook graph for example.

In two-node networks, also called bipartite graphs, the connections only exist between two formally separate classes of objects. So you might have people on the one hand and companies on the other, and you might connect a person to a company if she is on the board of that company. Or you could have people and the things they’re possibly interested in, and connect them if they really are.

Finally, there are ego networks, which is typically the part of the network surrounding a single person. So for example it could be just the subnetwork of my friends on Facebook, who may also know each other in certain cases. Kelly reports that people with higher socioeconomic status have more complicated ego networks. You can see someone’s level of social status by looking at their ego network.

What people do with these networks

The central question people ask when given a social network is, who’s important here?

This leads to various centrality measures. The key ones are:

- degree – This counts how many people are connected to you.

- closeness – If you are close to everyone, you have a high closeness score.

- betweenness – People who connect people who are otherwise separate. If information goes through you, you have a high betweenness score.

- eigenvector – A person who is popular with the popular kids has high eigenvector centrality. Google’s page rank is an example.

A caveat on the above centrality measures: the measurement people form an industry that try to sell themselves as the authority. But experience tells us that each has their weaknesses and strengths. The main thing is to know you’re looking at the right network.

For example, if you’re looking for a highly influential blogger in the muslim brotherhood, and you write down the top 100 bloggers in some large graph of bloggers, and start on the top of the list, and go down the list looking for a muslim brotherhood blogger, it won’t work: you’ll find someone who is both influential in the large network and who blogs for the muslim brotherhood, but they won’t be influential with the muslim brotherhood, but rather with transnational elites in the larger network. In other words, you have to keep in mind the local neighborhood of the graph.

Another problem with measures: experience dictates that, although something might work with blogs, when you work with Twitter you’ll need to get out new tools. Different data and different ways people game centrality measures make things totally different. For example, with Twitter, people create 5000 Twitter bots that all follow each other and some strategic other people to make them look influential by some measure (probably eigenvector centrality). But of course this isn’t accurate, it’s just someone gaming the measures.

Some network packages exist already and can compute the various centrality measures mentioned above:

- NodeXL, a plugin for Excel,

- NetworkX for python,

- igraph also for python,

- statnet for R, and

- Jure Leskovec at Stanford is creating new network package for C which should be awesome.

Thought experiment

You’re part of an elite, well-funded think tank in DC. You can hire people and you have $10million to spend. Your job is to empirically predict the future political evolution of Egypt. What kinds of political parties will there be? What is the country of Egypt gonna look like in 5, 10, or 20 years? You have access to exactly two of the following datasets for all Egyptians:

- The Facebook network,

- The Twitter network,

- A complete record of who went to school with who,

- The SMS/phone records,

- The network data on members of all political organizations and private companies, and

- Where everyone lives and who they talk to.

Note things change over time- people might migrate off of Facebook, or political discussions might need to go underground if blogging is too public. Facebook alone gives a lot of information but sometimes people will try to be stealth. Phone records might be better representation for that reason.

If you think the above is ambitious, recall Siemens from Germany sold Iran software to monitor their national mobile networks. In fact, Kelly says, governments are putting more energy into loading field with allies, and less with shutting down the field. Pakistan hires Americans to do their pro-Pakistan blogging and Russians help Syrians.

In order to answer this question, Kelly suggests we change the order of our thinking. A lot of the reasoning he heard from the class was based on the question, what can we learn from this or that data source? Instead, think about it the other way around: what would it mean to predict politics in a society? what kind of data do you need to know to do that? Figure out the questions first, and then look for the data to help me answer them.

Morningside Analytics

Kelly showed us a network map of 14 of the world’s largest blogospheres. To understand the pictures, you imagine there’s a force, like a wind, which sends the nodes (blogs) out to the edge, but then there’s a counteracting force, namely the links between blogs, which attach them together.

Here’s an example of the arabic blogosphere:

The different colors represent countries and clusters of blogs. The size of each dot is centrality through degree, so the number of links to other blogs in the network. The physical structure of the blogosphere gives us insight.

If we analyze text using NLP, thinking of the blog posts as a pile of text or a river of text, then we see the micro or macro picture only – we lose the most important story. What’s missing there is social network analysis (SNA) which helps us map and analyze the patterns of interaction.

The 12 different international blogospheres, for example, look different. We infer that different societies have different interests which give rise to different patterns.

But why are they different? After all, they’re representations of some higher dimensional thing projected onto two dimensions. Couldn’t it be just that they’re drawn differently? Yes, but we do lots of text analysis that convinces us these pictures really are showing us something. We put an effort into interpreting the content qualitatively.

So for example, in the French blogosphere, we see a cluster that discusses gourmet cooking. In Germany we see various blobs discussing politics and lots of weird hobbies. In English we see two big blobs [mathbabe interjects: gay porn and straight porn?] They turn out to be conservative vs. liberal blogs.

In Russian, their blogging networks tend to force people to stay within the networks, which is why we see very well defined partitioned blobs.

The proximity clustering is done using the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm, where being in the same neighborhood means your neighbors are connected to other neighbors, so really a collective phenomenon of influence.. Then we interpret the segments. Here’s an example of English language blogs:

Think about social media companies: they are each built around the fact that they either have the data or that they have a toolkit – a patented sentiment engine or something, a machine that goes ping.

But keep in mind that social media is heavily a product of organizations that pay to move the needle (i.e. game the machine that goes ping). To decipher that game you need to see how it works, you need to visualize.

So if you are wondering about elections, look at people’s blogs within “the moms” or “the sports fans”. This is more informative than looking at partisan blogs where you already know the answer.

Kelly walked us through an analysis, once he has binned the blogosphere into its segments, of various types of links to partisan videos like MLK’s “I have a dream” speech and a gotcha video from the Romney campaign. In the case of the MLK speech, you see that it gets posted in spurts around the election cycle events all over the blogosphere, but in the case of the Romney campaign video, you see a concerted effort by conservative bloggers to post the video in unison.

That is to say, if you were just looking at a histogram of links, a pure count, it might look as if it had gone viral, but if you look at it through the lens of the understood segmentation of the blogosphere, it’s clearly a planned operation to game the “virality” measures.

Kelly also works with the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard. He analyzed the Iranian blogosphere in 2008 and again in 2011 and he found much the same in terms of clustering – young anti-government democrats, poetry, conservative pro-regime clusters dominated in both years.

However, only 15% of the blogs are the same 2008 to 2011.

So, whereas people are often concerned about individuals (case-attribute model), the individual fish are less important than the schools of fish. By doing social network analysis, we are looking for the schools, because that way we learn about the salient interests of the society and how those interests are they stable over time.

The moral of this story is that we need to focus on meso-level patterns, not micro- or macro-level patterns.

John Bruner

Our second speaker of the night was John Bruner, an editor at O’Reilly who previously worked as the data editor at Forbes. He is broad in his skills: he does research and writing on anything that involved data. Among other things at Forbes, he worked on an internal database on millionaires on which he ran simple versions of social media dynamics.

Writing technical journalism

Bruner explained the term “data journalism” to the class. He started this by way of explaining his own data scientist profile.

First of all, it involved lots of data viz. A visualization is a fast way of describing the bottomline of a data set. And at a big place like the NYTimes, data viz is its own discipline and you’ll see people with expertise in parts of dataviz – one person will focus on graphics while someone else will be in charge of interactive dataviz.

CS skills are pretty important in data journalism too. There are tight deadlines, and the data journalist has to be good with their tools and with messy data (because even federal data is messy). One has to be able to handle arcane formats or whatever, and often this means parcing stuff in python or what have you. Bruner uses javascript and python and SQL and Mongo among other tools.

Bruno was a math major in college at University of Chicago, then he went into writing at Forbes, where he slowly merged back into quantitative stuff while there. He found himself using mathematics in his work in preparing good representations of the research he was uncovering about, for example, contributions of billionaires to politicians using circles and lines.

Statistics, Bruno says, informs the way you think about the world. It inspires you to write things: e.g., the “average” person is a woman with 250 followers but the median open twitter account has 0 followers. So the median and mean are impossibly different because the data is skewed. That’s an inspiration right there for a story.

Bruno admits to being a novice in machine learning.However, he claims domain expertise as quite important. With exception to people who can specialize in one subject, say at a governmental office or a huge daily, for smaller newspaper you need to be broad, and you need to acquire a baseline layer of expertise quickly.

Of course communications and presentations are absolutely huge for data journalists. Their fundamental skill is translation: taking complicated stories and deriving meaning that readers will understand. They also need to anticipate questions, turn them into quantitative experiments, and answer them persuasively.

A bit of history of data journalism

Data journalism has been around for a while, but until recently (computer-assisted reporting) was a domain of Excel power users. Still, if you know how to write an excel program, you’re an elite.

Things started to change recently: more data became available to us in the form of API’s, new tools and less expensive computing power, so we can analyze pretty large data sets on your laptop. Of course excellent viz tools make things more compelling, flash is used for interactive viz environments, and javascript is getting way better.

Programming skills are now widely enough held so that you can find people who are both good writers and good programmers. Many people are english majors and know enough about computers to make it work, for example, or CS majors who can write.

In big publications like the NYTimes, the practice of data journalism is divided into fields: graphics vs. interactives, research, database engineers, crawlers, software developers, domain expert writers. Some people are in charge of raising the right questions but hand off to others to do the analysis. Charles Duhigg at the NYTimes, for example, studied water quality in new york, and got a FOIA request to the State of New York, and knew enough to know what would be in that FOIA request and what questions to ask but someone else did the actual analysis.