Archive

Crappy modeling

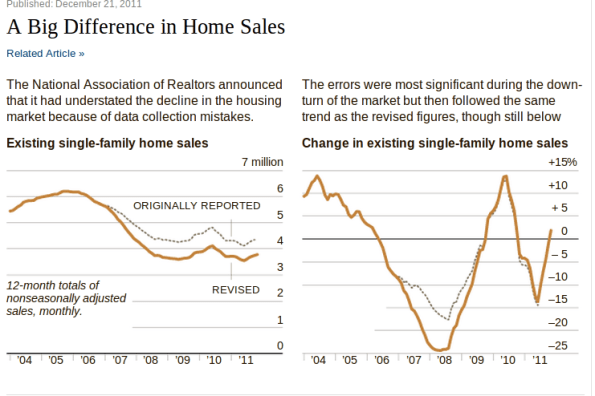

I’m here to vent today about crappy modeling I’m seeing in the world of finance. First up is the 14% corrections of home sales from 2007 to 2010 we’ve been seeing from the National Association of Realtors. From the New York Times article we see the following graph:

Supposedly the reason their models went so wrong was that they assumed a bunch of people were selling their houses without real estate agents. But isn’t this something they can check? I’m afraid it doesn’t pass the smell test, especially because it went on for so long and because it worked in their favor, in that the market didn’t seem as bad as it actually was. In other words, they had a reason not to update their model.

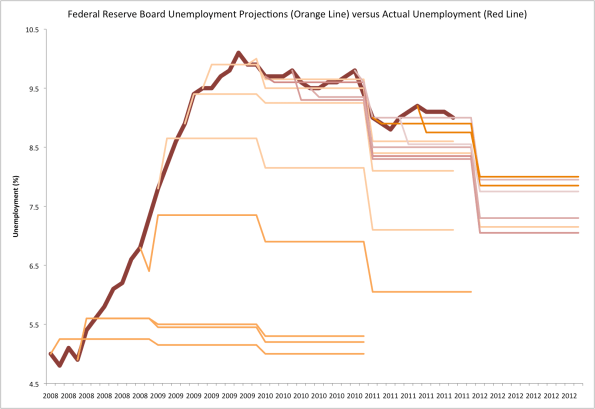

Here’s the next on our list, namely unemployment projections from the Fed versus actual unemployment figures, brought to us by Rortybomb:

Again we see outrageously bad modeling, which is always and consistently biased towards good news. Is this better than having no model at all? What kind of model is this biased? At the very least can you shorten your projection lengths to make up for how inaccurate they are, kind of like how weather forecasters don’t predict out past a week?

Finally, I’d like to throw in one last modeling complaint, namely about weekly unemployment filings. It seems to me that every December for the past few years, the projected unemployment filings have been “surprising” economists with how low they are, after seasonal adjustment.

First, seasonal adjustment is a weird thing, and was the subject of one of my earliest posts. We effectively don’t really know what the numbers mean after they are seasonally adjusted. But even so, we can imagine a bit: they look at past years and see how much the filings typically dip or surge (sadly it looks like they typically surge) at the end of the year, and assume the same kind of dip or surge should happen this year.

Here’s my thing. The fact that the filings surge less than expected the fourth or fifth year of an economic slump shouldn’t surprise anyone. These are real people, losing their real jobs with real consequences, right before Christmas. If you were a boss, wouldn’t you have made sure to have already fired someone in the early Fall or be willing to wait til after the holidays, especially when they know the chances of getting hired again quickly are very slim? Bosses are people too. I do not have statistically significant evidence for this by the way, just a theory.

How to challenge the SEC

This is a guest post by Aaron Abrams and Zeph Landau.

No, not the Securities and Exchange Commission. We are talking about the Southeastern Conference, a collection of 12 (or so) college football teams.

College football is a mess. Depending on your point of view, you can take it to task for many reasons: universities exploiting student athletes, student athletes not getting an education, student athletes getting special treatment, money corrupting everybody’s morals . . .

Putting those issues aside, however, there is virtually unanimous discontent with an aspect of the sport that is very quantitative, namely, how the season ends. Fans hate it, coaches hate it, players hate it, and there is a substantial controversy almost every single year. Only a few people who make lots of money off the current system seem to like it. (Never mind that anyone with a brain thinks there should be a playoff … perhaps that’s the subject of another post.)

Here’s how it works. There are roughly 120 major college football teams and each team plays 12 or 13 games in the fall. Almost all the teams belong to one of eleven conferences — these are like regional leagues — and most of the games they play are against other teams in their conference. (How they schedule their out-of-conference games is an interesting issue that we may write about another day.) At the end of the season, teams are invited to play in bowl games: games hosted at big stadiums with names like the Rose Bowl, the Orange Bowl, etc., that have long traditions. The problem centers around how teams are chosen to compete in these bowl games.

Basically, a cartel comprised of six of the eleven conferences (those that historically have been the strongest, including the SEC) created a system, called the BCS, that favors their own teams to get into the 5 most prestigious (and lucrative) bowl games, including the so called “national championship game” that claims to feature the top two teams in the country. The prestige gained by the 10 teams that compete in these games is matched by large amounts of money, coming mainly from television contracts and ticket sales. For each of these teams, we are talking about 10-20 million dollars that goes to a combination of the team and their conference. This is not a paltry sum for schools facing major budget cuts.

The most blatant problem with this system is that is it literally unfair: the rules of the system are written in such a way that at the beginning of the season, before any games are played and regardless of how good the teams are, the teams from the six “BCS conferences” have a better chance of getting into one of the major bowls than a team from a non-BCS conference. (You can read the rules, but notably, each of the conference champions of the six BCS conferences automatically gets to play in a BCS bowl game; whereas the other conference champions only get to play in a BCS bowl game if various other conditions are met, like they’re highly ranked in the polls).

There are lots of other problems, too, but we’re not really going to talk about those. For instance the method for choosing the top two teams (which is based on both human and computer polls) is deeply and fundamentally flawed. These are the teams that play for the “BCS championship”, so it matters who the top two are. But again, that’s the subject of a different post.

Back to the inherent unfairness. Colleges in the non-BCS conferences are well aware of this situation. Led by Tulane, they filed a lawsuit several years ago and essentially won; the rules used to be even worse before that. But in the face of the continued lack of fairness, colleges from non-BCS conferences have lately taken to responding by trying to get into the BCS conferences, jockeying for opportunity at big money. It has gotten so bad that a BCS conference called the Big East now includes teams from Idaho and California. Realignment has caused the Big 12 to have only 10 teams, while the Big 10 has 12.

But realignment takes a lot of work to pull off, and it only benefits the teams that get into the major conferences. The minor conferences themselves are still left behind. So here is a better idea. If you’re a non-BCS conference, do what any good red-blooded american corporation would do: find a loophole.

Here is one we thought of.

The current rules force the BCS to choose a team from one of the 5 non-BCS conferences if:

(a) a team has won its conference AND is ranked in the top 12, or

(b) a team has won its conference AND is ranked in the top 16 AND is ranked higher than the conference champion from one of the BCS conferences.

What they don’t say is what it means for a team to “win its conference.” Some conferences determine their champion by overall record, and others have a championship game to decide the champion. This is the chink in the armor.

This year two interesting things happened: (1) in the Western Athletic Conference (WAC), Boise State ended up ranked #7, but did not win their conference. The WAC doesn’t have its own championship game, and the conference winner was TCU by virtue of beating Boise State in a game in the middle of the season. However, TCU also lost a game to a team outside their conference, and they ended up ranked only #18. As a result, neither team satisfied condition (a) or (b) above.

And (2) in Conference USA, Houston was undefeated and ranked #6 in the country before the final game of the season, when it lost its conference championship game to USM. The loss dropped Houston to #19 in the rankings, whereas USM, the conference champion, finished with a final ranking of #21. Thus neither of these teams met (a) or (b), either.

Here is what we noticed: if the Western Athletic Conference had a conference championship game, then either Boise St would have won it, been declared the champion, and qualified for a BCS bowl, or else TCU would have won it and would almost surely have ended up with a high enough rank to qualify for a BCS bowl. (As it was, TCU finished the season at #18, but one more victory against a top ten team would very likely have gained them at least two spots. This would have been good enough for (b) to apply, since the champion of the Big East (a BCS conference) was West Virginia, who finished ranked #23.)

On the other hand, if Conference USA hadn’t had a championship game, Houston would have been declared the conference champion (by virtue of being undefeated before the championship game) and they would easily have been ranked highly enough to get into a BCS bowl. Indeed, it has been estimated that their loss to USM cost Conference USA $17 million.

So, what should these non-BCS conferences do? Hold a conference championship game . . . if, and only if, it benefits them. They can decide this during the last week of the season. This year, with nothing to lose and plenty to gain, the WAC would clearly have chosen to have a championship game. With nothing to gain and plenty to lose, Conference USA would have chosen not to.

Bingo. Loophole. 17 million big ones. Cha ching.

Bloomberg engineering competition goes to Cornell

This just in. Pretty surprising considering we were supposed to hear the results January 15th. I wrote about this here and here.

I wonder what Columbia is going to do with their plans?? I guess there may be two winners, so still exciting.

Bloomberg engineering competition gets exciting

Stanford has bowed out of the Bloomberg administration’s competition for an engineering center in New York City. From the New York Times article:

Stanford University abruptly dropped out of the intense international competition to build an innovative science graduate school in New York City, releasing its decision on Friday afternoon. A short time later, its main rival in the contest, Cornell, announced a $350 million gift — the largest in its history — to underwrite its bid.

From what I’d heard, Stanford was the expected winner, with Cornell being a second place. This changes things, and potentially means that Columbia’s plan for a Data Science and Engineering Institute is still a possibility.

Cool and exciting, because I want that place to be really really good.

It also seems like the open data situation in New York is good and getting better. From the NYC Open Data website:

This catalog supplies hundreds of sets of public data produced by City agencies and other City organizations. The data sets are now available as APIs and in a variety of machine-readable formats, making it easier than ever to consume City data and better serve New York City’s residents, visitors, developer community and all!

Maybe New York will be a role model for good, balancing its reputation as the center of financial shenanigans.

Privacy vs. openness

I believe in privacy rights when it comes to modern technology and data science models, especially when the models are dealing with things like email or health records. It makes sense, for example, that the data itself is not made public when researchers study diseases and treatments.

Andrew Gelman’s blog post recently brought this up, and clued me into the rules of sharing data coming from the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The IRB rules deal with questions like whether the study participants have agreed to let their data be shared if the data is first anonymized. But the crucial question is whether it’s really possible to anonymize data at all.

It turns out it’s not that easy, especially if the database is large. There have been famous cases (Netflix prize) where people have been identified even though the data was “anonymized.”

On the other hand, we don’t want people creating and running with secret models with the excuse that they are protecting people’s privacy. First, because the models may not work: we want scientific claims to be substantiated by retesting, for example (this was the point of Gelman’s post). But also we generally want a view into how people are using personal information about people.

Most modeling going on nowadays involving personal information is probably not fueled by academic interest in curing diseases, but rather how to sell stuff and how to monitor people.

As two examples, this Bloomberg article describes how annoyed people get when they are being tracked while they’re shopping in malls, even though the actual intrusiveness of the tracking is arguably much worse when people shop online, and this Wall Street Journal article describes the usage of French surveillance systems in the Gadhafi regime.

I think we should separate two issues here, namely the model versus the data. In the cases of public surveillance, like at the mall or online, or something involving public employees, I think people should be able to see how their data is being used even if the entire database is being kept out of their view. This way nobody can say their privacy is being invaded.

For example, if the public school system uses data from students and teachers to score the value added of teaching, then the teachers should have access to the model being used to score them. In particular this would mean they’d be able to see how their score would have changed if certain of their attributes changed, like which school they teach at or how many kids are in their class.

It is unlikely that private companies would be happy to expose the models they use to sell merchandise or clicks. If private companies don’t want to reveal their secret sauce, then one possibility is to make their modeling opt-in (rather than opt-out). By the way, right now you can opt out of most things online by consistently clearing your cookies.

I am being pretty extreme here in my suggestions, but even if we don’t go this far, I think it’s clear that we will have to consider these questions and many more questions like this soon. The idea that the online data modeling can be self-regulating is pretty laughable to me, especially when you consider how well that worked in finance. The kind of “stalker apps” that are popping up everywhere are very scary and very creepy to people who like the idea of privacy.

In the meantime we need some nerds to figure out a better way to anonymize data. Please tell me if you know of progress in that field.

Resampling

I’m enjoying reading and learning about agile software development, which is a method of creating software in teams where people focus on short and medium term “iterations”, with the end goal in sight but without attempting to map out the entire path to that end goal. It’s an excellent idea considering how much time can be wasted by businesses in long-term planning that never gets done. And the movement has its own manifesto, which is cool.

The post I read this morning is by Mike Cohn, who seems heavily involved in the agile movement. It’s a good post, with a good idea, and I have just one nerdy pet peeve concerning it.

I’m a huge fan of stealing good ideas from financial modeling and importing them into other realms. For example, I stole the idea of stress testing of portfolios and use them in stress testing the business itself where I work, replacing scenarios like “the Dow drops 9% in a day” with things like, “one of our clients drops out of the auction.”

I’ve also stolen the idea of “resampling” in order to forecast possible future events based on past data. This is particularly useful when the data you’re handling is not normally distributed, and when you have quite a few data points.

To be more precise, say you want to anticipate what will happen over the next week (5 days) with something. You have 100 days of daily results in the past, and you think the daily results are more or less independent of each other. Then you can take 5 random days in the past and see how that “artificial week” would look if it happened again. Of course, that’s only one artificial week, and you should do that a bunch of times to get an idea of the kind of weeks you may have coming up.

If you do this 10,000 times and then draw a histogram, you have a pretty good sense of what might happen, assuming of course that the 100 days of historical data is a good representation of what can happen on a daily basis.

Here comes my pet peeve. In Mike Cohn’s blog post, he goes to the trouble of resampling to get a histogram, so a distribution of fake scenarios, but instead of really using that as a distribution, for the sake of computing a confidence interval, he only computes the average and standard deviation and then replaces the artificial distribution with a normal distribution with those parameters. From his blog:

Armed with 200 simulations of the ten sprints of the project (or ideally even more), we can now answer the question we started with, which is, How much can this team finish in ten sprints? Cells E17 and E18 of the spreadsheet show the average total work finished from the 200 simulations and the standard deviation around that work.

In this case the resampled average is 240 points (in ten sprints) with a standard deviation of 12. This means our single best guess (50/50) of how much the team can complete is 240 points. Knowing that 95% of the time the value will be within two standard deviations we know that there is a 95% chance of finishing between 240 +/- (2*12), which is 216 to 264 points.

What? This is kind of the whole point of resampling, that you could actually get a handle on non-normal distributions!

For example, let’s say in the above example, your daily numbers are skewed and fat-tailed, like a lognormal distribution or something, and say the weekly numbers are just the sum of 5 daily numbers. Then the weekly numbers will also be skewed and fat-tailed, although less so, and the best estimate of a 95% confidence interval would be to sort the scenarios and look at the 2.5th percentile scenario, the 97.5th percentile scenario and use those as endpoints of your interval.

The weakness of resampling is the possibility that the data you have isn’t representative of the future. But the strength is that you get to work with a honest-to-goodness distribution and don’t need to revert to assuming things are normally distributed.

Quantitative theory of blogging

Once you start blogging, it turns out you can get quite addicted to your daily hits, which is a count of how many people come to your site each day, as well as to the quantity and quality of the comments (my readers have the best comments by the way, just saying).

WordPress even lets you see which things people read, and how they searched google to find your site, and what they clicked on. It’s easy enough to get excited about such statistics, and the natural consequence is an urge to juice your numbers.

What is the equivalent of Major League Baseball steroids for bloggers? I have a few suggestions:

- Post about something super controversial, i.e. something that people care about and are totally divided about. Once I heard a sports talk radio host give away this trade secret on his show, when he said, “okay folks let’s talk about this next question, which when polled was split down the middle 50/50 among people…”. I think I hit on this once when I posted about how I think math contests suck. Lots of strong feelings both ways.

- Post about something involving people that others consider kind of crazy. Once when I posted about living forever, I was kind of responding to this idea of the Singularity Theorists and their summit. Turns out some people don’t want to live forever, like me, and some people really really want to live forever. It’s like a religion.

- Then there’s the celebrity angle. My posts about working with Larry Summers have generated lots of traffic, although I like to think it’s because of what I said in addition to the star power in the title.

- I’m convinced that adding images to your posts makes people more likely to find them. Maybe that’s because they appear bigger when they are shared on Facebook or something.

- If you are fed up with people arguing with each other on your comments pages, then another totally different way of getting lots of hits (and even more comments) is to post about something that allows people to tell a story about themselves that probably nobody else wants to hear. For example, you can write a post entitled, “did you ever have a weird experience at a doctor’s appointment?”. I haven’t done that yet but it’s tempting, just for all the awesome comments I’d get.

- Finally, you can go lowbrow and talk about sex, or even better give advice to people about their weird sexual desires, or even better, make confessions about your weird sexual experiences. Also haven’t done that yet, but also tempted.

I’m a data modeler, so of course it makes sense that I’d try to test out my theoretical signals. So if you see me writing a post in the future about the sexual adventures of me and some nutjob celebrity (update: Charlie Sheen) when we went to the doctor’s together, complete with graphic pix, then you’ll know to click like mad (and comment, please!).

Hey Google, do less evil.

I recently read this article in the New York Times about a business owner’s experiences using Google Adwords.

For those of you not familiar with the advertising business, here’s a geeky explanation. As a business owner, you choose certain key words or phrases, and if and when someone searches on Google with that word or phrase, you bid a certain amount to have your business shown at the top of the return searches or along the right margin of the page. You fix the bid (say 4 cents) beforehand, and you only pay that 4 cents when someone actually clicks. The way your position in the resulting page is determined is through an auction.

Say, for example, you and your competitors have all bid different amounts for the keyword “monodromy”. Then every time someone searches for “monodromy”, all the bids are sorted after being weighted by a quality score, which is a secret sauce created by Google but can be thought of as the probability that some random person will click on your ad.

This weighting makes sense, since Google is essentially determining the expected value of showing your ad: the product of the amount of money they will get paid if someone clicks on it (again, because they only get paid when the click occurs) and the probability of that event actually happening. Quality scores are actually slightly more than this, and we will get back to this issue below.

Moreover, once the sorting by expected value is done, your actual payment is determined not precisely by your bid but by the minimum bid you’d need to still maintain your position in the auction. This is a clever idea that gets people to raise their bids in order to win first place in the auction but not need to pay too much… unless there’s another guy who is determined to win first place.

Of course, it’s not always necessary to pay Google to get clicks. Sometimes your business will show up in the “organic searches” anyway- say if the name of your company is well-chosen for your product. So if you’re selling oak tables and the name of your company is “Oak Tables” then you may not need to pay anything for the that key phrase (but you may be willing to pay for the phrase “tables oak cherry”).

Back to the business owner. He decided to experiment with turning off Adwords, in other words he decided to rely on the results of organic searching instead of paying for each click. It didn’t end well- he gave up after a week because business was bad. The thing that caught my eye in this article was the suggestion that, when he turned off the payment, Google also became stingy with showing his free results. In other words, Google seems to be juicing their results (which is likely done through the quality score function) to punish people for not being in the pay-for-clicks program:

What is surprising to me is the steep drop in organic visits, the clicks from free links. They have fallen 47 percent, from 328 to 173. Stopping the AdWords payments seems to have affected unpaid traffic as well. According to everything I’ve been told about search engine optimization, this shouldn’t have happened. But from a business standpoint, it makes sense to me. Google is in business to make money by selling searches. Why shouldn’t it boost the free listings of its paying customers — and degrade the results when they stop paying? It’s also possible that people are more inclined to click on free results when they see the same company has the top paid link. Maybe it’s conscious, maybe it’s not. I’d be interested to hear any theories readers may have as to why my organic traffic took such a fall.

One theory I have is that it’s unfortunately impossible to figure out, because Google doesn’t seem to think they need to explain anything to anyone, even though they have become the arbiter of information. It’s a scary prospect, that they have so much control over the way we see and understand the world, and between you and me their “do no evil” motto isn’t sufficiently reassuring to make me want to trust them on this completely.

A friend of mine recently had a terrible experience with Google which makes this lack of clarity especially frustrating. Namely, some nut job decided to post evil stuff about him and someone else through comments on other peoples’ blogs. There was no way for him to address this except by asking the individuals whose websites had been used to take down the posts. In particular, there was no way for my friend to address the resulting prominent Google search results through the people working at Google- they don’t answer the phone. It doesn’t matter to them that people’s lives could be ruined with false information; they decided many years ago that they are not in the client service industry and haven’t looked back. Their policy seems to be that, as long as there is no actual and real threat of violence, they have no obligation to do anything.

That would be okay for a small startup with little influence on the world, but that’s really not what Google is. Google wields tremendous powers, and their quality score algorithm is defining our world. At this point they have a moral responsibility to make sure their search result algorithms aren’t ruining people’s lives.

What if it were possible to mark a search results as “inappropriate”? And then, given enough votes, the quality score would be affected and the listing would go down to the bottom of page 19. I realize of course that this could be used for good as well as for bad – people could abuse such a system as well, by squelching information they don’t want to see. But the problem with that argument is that it’s already happening, just inside Google, where we have no view. So in other words yes, it’s a judgment call, but I’d rather have a person (or people) do that than an algorithm.

Overfitting

I’ve been enjoying watching Andrew Ng’s video lectures on machine learning. It requires a login to see the videos, but it’s well worth the nuisance. I’ve caught up to the current lecture (although I haven’t done the homework) and it’s been really interesting to learn about the techniques Professor Ng describes to avoid overfitting models.

In particular, he talks about iterative concepts of overfitting and how to avoid them. I will first describe the methods he uses, then I’ll try to make the case that they are insufficient, especially in the case of a weak signal. By “weak signal” I mean anything you’d come across in finance that would actually make money (technically you could define it to mean that the error has the same variance as the response); almost by definition those signals are not very strong (but maybe were in the 1980’s) or they would represent a ridiculous profit opportunity. This post can be seen as a refinement of my earlier post, “Machine Learners are spoiled for data“, which I now realize should have ended “spoiled for signal”.

First I want to define “overfitting”, because I probably mean something different than most people do when they use that term. For me, this means two things. First, that you have a model that is too complex, usually with too many parameters or the wrong kind of parameters, that has been overly trained to your data but won’t have good forecasting ability with new data. This is the standard concept of overfitting- you are modeling noise instead of signal but you don’t know it. The second concept, which is in my opinion even more dangerous, is partly a psychological one, namely that you trust your model too much. It’s not only psychological though, because it also has a quantitative result, namely that the model sucks at forecasting on new data.

How do you avoid overfitting? First, Professor Ng makes the crucial observation that you can’t possibly think that the model you are training will forecast as well on new data as on the data you have trained on. Thus you need to separate “training data” from “testing data”. So far so good.

Next, Professor Ng makes the remark that, if you then train a bunch of different models on the training data, which depend on the number of variables you use for example, then if you measure each model by looking at its performance on the testing data to decide on that parameter, you can no longer expect the resulting model (with that optimized number of parameters) to actually do so extremely well on actually new data, since you’ve now trained your model to the testing data. For that reason he ends up splitting the data into three parts, namely the training data (60%), a so-called validation data set (20%) and finally the true testing set (the last 20%).

I dig it as an idea, this idea of splitting the data into three parts, although it requires you have enough data to think that testing a model on 20% of your data will give you meaningful performance results, which is already impossible when you work in finance, where you have both weak signal and too little data.

But the real problem is that, after you’ve split your data into three parts, you can’t really feel like the third part, the “true test data”, is anything like clean data. Once you’ve started using your validation set to train your data, you may feel like you’ve donated enough to the church, so to speak, and can go out on a sin bender.

Why? Because now the methods that Professor Ng suggests, for example to see how your model is doing in terms of testing for high bias or high variance (I’ll discuss this more below), looks at how the model performs on the test set. This is just one example of a larger phenomenon: training to the test set. If you’ve looked at the results on the test set at all before fixing your model, then the test set is just another part of your training set.

It’s human nature to do it, and that’s why the test set should be taken to a storage closet and locked up, by someone else, until you’ve finished your modeling. Once you have declared yourself done, and you promise you will no longer tweak the results, you should then find the person, their key, and test your model on the test set. If it doesn’t work you give up and try something else. For real.

In terms of weak signals, this is all the more important because it’s so freaking easy to convince yourself there’s signal when there isn’t, especially if there’s cash money involved. It’s super important to have the “test data set”, otherwise known as the out-of-sample data, be kept completely clean and unviolated. In fact there should even be a stipulated statute of limitations on how often you get to go out of sample on that data for any model at all. In other words, you can’t start a new model on the same data once a month until you find something that works, because then you’re essentially training your space of models to that out-of-sample data – you are learning in your head the data and how it behaves. You can’t help it.

One method that Ng suggests is to draw so-called “learning curves” which plot the loss function of the model on the test set and the validation set as a function of the number of data points under consideration. One huge problem with this for weak signals is that the noise would absolutely overwhelm such a loss estimate, and we’d end up looking at two extremely misleading plots, or information-free plots, the only result of which would be that we’ve seen way too much of the test set for comfort.

It seems to me that the method Ng suggests is the direct result of wanting to make the craft of modeling into an algorithm. While I’m not someone who wants to keep things guild-like and closed, I just don’t think that everything is as easy as an algorithm. Sometimes you just need to get used to not knowing something. You can’t test the fuck out of your model til you optimize on every single thing in site, because you will be overfitting your model, and you will have an unrealistic level of confidence in the result. As we know from experience, this could be very bad, or it could just be a huge waste of everyone’s time.

Data Science and Engineering at Columbia?

Yesterday Columbia announced a proposal to build an Institutes for Data Sciences and Engineering a few blocks north of where I live. It’s part of the Bloomberg Administration’s call for proposals to add more engineering and entrepreneurship in New York City, and he’s said the city is willing to chip in up to 100 million dollars for a good plan. Columbia’s plan calls for having five centers within the institute:

- New Media Center (journalism, advertising, social media stuff)

- Smart Cities Center (urban green infrastructure including traffic pattern stuff)

- Health Analytics Center (mining electronic health records)

- Cybersecurity Center (keeping data secure and private)

- Financial Analytics Center (mining financial data)

A few comments. Currently the data involved in media 1) and finance 5) costs real money, although I guess Bloomerg can help Columbia get a good deal on Bloomberg data. On the other hand, urban traffic data 2) and health data 3) should be pretty accessible to academic researchers in New York.

There’s a reason that 1) and 5) cost money: they make money. The security center is kind of in the middle, since you can try to make any data secure, you don’t need to particularly pay for it, but on the other hand if you can find a good security system then people will pay for it.

On the other hand, even though it’s a great idea to understand urban infrastructure and health data, it’s not particularly profitable (not to say it doesn’t save alot of money potentially, but it’s hard to monetize the concept of saving money, especially if it’s the government’s or the city’s money).

So the overall cost structure of the proposed Institute would probably work like this: incubator companies from 1) and 5) and maybe 4) fund the research going on in (themselves and) 2) and 3). This is actually a pretty good system, because we really do need some serious health analytics research on an enormous scale, and it needs to be done ethically.

Speaking of ethics, I hope they formalize and follow The Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath. In fact, if they end up building this institute, I hope they have a required ethics course for all incoming students (and maybe professors).

Hmmm… I’d better get my “data science curriculum” plan together fast.

Is Big Data Evil?

Back when I was growing up, your S.A.T. score was a big deal, but I feel like I lived in a relatively unfettered world of anonymity compared to what we are creating now. Imagine if your SAT score decided your entire future.

Two days ago I wrote about Emanuel Derman’s excellent new book “Models. Behaving. Badly.” and mentioned his Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath, which I may have to restate on every post from now on:

- I will remember that I didn’t make the world, and it doesn’t satisfy my equations.

- Though I will use models boldly to estimate value, I will not be overly impressed by mathematics.

- I will never sacrifice reality for elegance without explaining why I have done so.

- Nor will I give the people who use my model false comfort about its accuracy. Instead, I will make explicit its assumptions and oversights.

- I understand that my work may have enormous effects on society and the economy, many of them beyond my comprehension.

I mentioned that every data scientist should sign at the bottom of this page. Since then I’ve read three disturbing articles about big data. First, this article in the New York Times, which basically says that big data is a bubble:

This is a common characteristic of technology that its champions do not like to talk about, but it is why we have so many bubbles in this industry. Technologists build or discover something great, like railroads or radio or the Internet. The change is so important, often world-changing, that it is hard to value, so people overshoot toward the infinite. When it turns out to be merely huge, there is a crash, in railroad bonds, or RCA stock, or Pets.com. Perhaps Big Data is next, on its way to changing the world.

In a way I agree, but let’s emphasize the “changing the world” part, and ignore the hype. The truth is that, beyond the hype, the depth of big data’s reach is not really understood yet by most people, especially people inside big data. I’m not talking about the technological reach, but rather the moral and philosophical reach.

Let me illustrate my point by explaining the gist of the other two articles, both from the Wall Street Journal. The second article describes a model which uses the information on peoples’ credit card purchases to direct online advertising at them:

MasterCard earlier this year proposed an idea to ad executives to link Internet users to information about actual purchase behaviors for ad targeting, according to a MasterCard document and executives at some of the world’s largest ad companies who were involved in the talks. “You are what you buy,” the MasterCard document says.

MasterCard doesn’t collect people’s names or addresses when processing credit-card transactions. That makes it tricky to directly link people’s card activity to their online profiles, ad executives said. The company’s document describes its “extensive experience” linking “anonymized purchased attributes to consumer names and addresses” with the help of third-party companies.

MasterCard has since backtracked on this plan:

The MasterCard spokeswoman also said the idea described in MasterCard’s April document has “evolved significantly” and has “changed considerably” since August. After the company’s conversations with ad agencies, MasterCard said, it found there was “no feasible way” to connect Internet users with its analysis of their purchase history. “We cannot link individual transaction data,” MasterCard said.

How loudly can you hear me say “bullshit”? Even if they decide not to do this because of bad public relations, there are always smaller third-party companies who don’t even have a PR department:

Credit-card issuers including Discover Financial Services’ Discover Card, Bank of America Corp., Capital One Financial Corp. and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. disclose in their privacy policies that they can share personal information about people with outside companies for marketing. They said they don’t make transaction data or purchase-history information available to outside companies for digital ad targeting.

The third article talks about using credit scores, among other “scoring” systems, to track and forecast peoples’ behavior. They model all sorts of things, like the likelihood you will take your pills:

Experian PLC, the credit-report giant, recently introduced an Income Insight score, designed to estimate the income of a credit-card applicant based on the applicant’s credit history. Another Experian score attempts to gauge the odds that a consumer will file for bankruptcy.

Rival credit reporter Equifax Inc. offers an Ability to Pay Index and a Discretionary Spending Index that purports to indicate whether people have extra money burning a hole in their pocket.

Understood, this is all about money. This is, in fact, all about companies ranking you in terms of your potential profitability to them. Just to make sure we’re all clear on the goal then:

The system “has been incredibly powerful for consumers,” said Mr. Wagner.

Ummm… well, at least it’s nice to see that it’s understood there is some error in the modeling:

Eric Rosenberg, director of state-government relations for credit bureau TransUnion LLC, told Oregon state lawmakers last year that his company can’t show “any statistical correlation” between the contents of a credit report and job performance.

But wait, let’s see what the CEO of Fair Isaac Co, one of the companies creating the scores, says about his new system:

“We know what you’re going to do tomorrow”

This is not well aligned with the fourth part of the Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath (MHO). The article goes on to expose some of the questionable morality that stems from such models:

Use of credit histories also raises concerns about racial discrimination, because studies show blacks and Hispanics, on average, have lower credit scores than non-Hispanic whites. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed suit last December against the Kaplan Higher Education unit of Washington Post Co., claiming it discriminated against black employees and applicants by using credit-based screens that were “not job-related.”

Let me make the argument for these models before I explain why I think they’re flawed.

First, in terms of the credit card information, you should all be glad that the ads coming to us online are so beautifully tailored to your needs and desires- it’s so convenient, almost like someone read your mind and anticipated you’d be needing more vacuum cleaner bags at just the right time! And in terms of the scoring, it’s also very convenient that people and businesses somehow know to trust you, know that you’ve been raised with good (firm) middle-class values and ethics. You don’t have to argue my way into a new credit card or a car purchase, because the model knows you’re good for it. Okay, I’m done.

The flip side of this is that, if you don’t happen to look good to the models, you are funneled into a shitty situation, where you will continue to look bad. It’s a game of chutes and ladders, played on an enormous scale.

[If there’s one thing about big data that we all need to understand, it’s the enormous scale of these models.]

Moreover, this kind of cyclical effect will actually decrease the apparent error of the models: this is because if we forecast you as being uncredit-worthy, and your life sucks from now on and you have trouble getting a job or a credit card and when you do you have to pay high fees, then you are way more likely to be a credit risk in the future.

One last word about errors: it’s always scary to see someone on the one hand admit that the forecasting abilities of a model may be weak, but on the other hand say things like “we know what you’re going to do tomorrow”. It’s a human nature thing to want something to work better than it does, and that’s why we need the IMO (especially the fifth part).

This all makes me think of the movie Blade Runner, with its oppressive sense of corporate control, where the seedy underground economy of artificial eyeballs was the last place on earth you didn’t need to show ID. There aren’t any robots to kill (yet) but I’m getting the feeling more and more that we are sorting people at birth, or soon after, to be winners or losers in this culture.

Of course, collecting information about people isn’t new. Why am I all upset about it? Here are a few reasons, which I will expand on in another post:

- There’s way more information about people nowadays than their Social Security Number; the field of consumer information gathering is huge and growing exponentially

- All of those quants who left Wall Street are now working in data science and have real skills (myself included)

- They also typically don’t have any qualms; they justify models like this by saying, hey we’re just using correlations, we’re not forcing people to behave well or badly, and anyway if I don’t make this model someone else will

- The real bubble is this: thinking these things work, and advocating their bulletproof convenience and profitability (in the name of mathematics)

- Who suffers when these models fail? Answer: not the corporations that use them, but rather the invisible people who are designated as failures.

Math in Business

Here’s an annotated version of my talk at M.I.T. a few days ago. There was a pretty good turnout, with lots of grad students, professors, and I believe some undergraduates.

What are the options?

First let’s talk about the different things you can do with a math degree.

Working as an academic mathematician

You all know about this, since you’re here. In fact most of your role models are probably professors. More on this.

Working at a government institution

I don’t have personal experience, but there are plenty of people I know who are perfectly happy working for the spooks or NASA.

Working as a quant in finance

This means trying to predict the market in one way or another, or modeling how the market works for the sake of measuring risk.

Working as a data scientist

This is my current job, and it is kind of vague, but it generally means dealing with huge data sets to locate, measure, visualize, and forecast patterns. Quants in finance are examples of data scientists, and they work in the most, or one of the most, developed subfield of data science.

Cultural Differences

I care a lot about the culture of my job, as I think women in general tend to. For that reason I’m going to try to give a quick and exaggerated description of the cultures of these various options and how they differ from each other.

Feedback is slow in academics

I’m still waiting for my last number theory paper to get published, and I left the field in 2007. That hurts. But in general it’s a place for people who have internal feedback mechanisms and don’t rely on external ones. If you’re a person who knows that you’re thinking about the most important question in the world and you don’t need anyone to confirm that, then academics may be a good cultural fit. If, on the other hand, you are wondering half the time why you’re working on this particular problem, and whether the answer really matters or ever will matter to someone, then academics will be a tough place for you to live.

Institutions are painfully bureaucratic

As I said before, I don’t have lots of personal experience here, but I’ve heard that good evidence that working at a government institution is sometimes painful in terms of waiting for things that should obviously happen actually happen. On the other hand I’ve also head lots of women say they like working for institutions and that they are encouraged to become managers and grow groups. We will talk more about this idea of being encouraged to be organized.

Finance firms are cut-throat

Again, exaggerating for effect, but there’s a side effect of being in a place whose success is determined along one metric (money), and that is that people are typically incredibly competitive with each other for their perceived value with respect to that metric. Kind of like a bunch of gerbils in a case with not quite enough food. On the other hand, if you love that food yourself, you might like that kind of struggle.

Startups are unstable

If you don’t mind wondering if your job is going to exist in 1 or 2 months, then you’ll love working at a startup. It’s an intense and exciting journey with a bunch of people you’d better trust or you’ll end up really hating them.

Outside academics, mathematicians have superpowers

One general note that you, being inside academics right now, may not be aware of: being really fucking good at math is considered a superpower by the people outside. This is because you can do stuff with your math that they actually don’t know how to do, no matter how much time they spend trying. This power is good and bad, but in any case it’s very different than you may be used to.

Going back to your role models: you see your professors, they’re obviously really smart, and you naturally may want to become just like them when you grow up. But looking around you, you notice there are lots of good math students here at M.I.T. (or wherever you are) and very few professor jobs. So there is this pyramid, where lots of people a the bottom are all trying to get these fancy jobs called math professorships.

Outside of math, though, it’s an inverted world. There are all of these huge data sets, needing analysis, and there are just very few places where people are getting trained to do stuff like that. So M.I.T. is this tiny place inside the world, which cannot possibly produce enough mathematicians to satisfy the demand.

Another way of saying this is that, as a student in math, you should absolutely be aware that it’s easier to get a really good job outside the realm of academics.

Outside academics, you get rewarded for organizational skills (punished within)

One other big cultural difference I want to mention is that inside academics, you tend to get rewarded for avoiding organizational responsibilities, with some exceptions perhaps if you organize conferences or have lots of grad students. Outside of academics, though, if you are good at organizing, you generally get rewarded and promoted and given more responsibility for managing a group of nerds. This is another personality thing- some math nerds love the escape from organizing, or just plain suck at it, and maybe love academics for that reason, whereas some math nerds are actually quite nurturing and don’t mind thinking about how systems should be set up and maintained, and if those people are in academics they tend to be given all of the “housekeeping” in the department, which is almost always bad for their career.

Mathematical Differences

Let’s discuss how the actual work you would do in these industries is different. Exaggeration for effect as usual.

Academic freedom is awesome but can come with insularity

If you really care about having the freedom to choose what math you do, then you absolutely need to stay in academics. There is simply no other place where you will have that freedom. I am someone who actually does have taste, but can get nerdy and interested in anything that is super technical and hard. My taste, in fact, is measured in part by how much I think the answer actually matters, defined in various ways: how many people care about the answer and how much of an impact would knowing the answer make? These properties are actually more likely to be present in a business setting. But some people are totally devoted to their specific field of mathematics.

The flip side of academic freedom is insularity; since each field of mathematics gets to find its way, there tend to be various people doing things that almost nobody understands and maybe nobody will ever care about. This is more or less frustrating to you depending on your personality. And it doesn’t happen in business: every question you seriously work on is important, or at least potentially important, for one reason or another to the business.

You don’t decide what to work on in business but the questions can be really interesting

Modeling with data is just plain fascinating, and moreover it’s an experimental science. Every new data set requires new approaches and techniques, and you feel like a mad scientist in a lab with various tools that you’ve developed hanging on the walls around you.

You can’t share proprietary information with the outside world when you work in business or for the government

The truth is, the actual models you create are often the crux of the profit in that business, and giving away the secrets is giving away the edge.

On the other hand, sometimes you can and it might make a difference

The techniques you develop are something you generally can share with the outside world. This emerging field of data science can potentially be put to concrete and good use (more on that later).

In business, more emphasis on shallower, short term results

It’s all about the deadlines, the clients, and what works.

On the other hand, you get much more feedback

It’s kind of nice that people care about solving urgent problems when… you’ve just solved an urgent problem.

Which jobs are good for women?

Part of what I wanted to relay today is those parts of these jobs that I think are particularly suitable for women, since I get lots of questions from young women in math wondering what to do with themselves.

Women tend to care about feedback

And they tend to be more sensitive to it. My favorite anecdote about this is that, when I taught I’d often (not always) see a huge gender difference right after the first midterm. I’d see a young woman coming to office hours fretting about an A- and I’d have to flag down a young man who got a C, and he’d say something like, “Oh, I’m not worried, I’ll just study and ace the final.” There’s a fundamental assumption going on here, and women tend to like more and more consistent feedback (especially positive feedback).

One of my most firm convictions about why there are not more women math professors out there is that there is virtually no feedback loop after graduating with a Ph.D., except for some lucky people (usually men) who have super involved and pushy advisors. Those people tend to be propelled by the will of their advisor to success, and lots of other people just stay in place in a kind of vacuum. I’ve seen lots of women lose faith in themselves and the concept of academics at this moment. I’m not sure how to solve this problem except by telling them that there’s more feedback in business. I do think that if people want to actually address the issue they need to figure this out.

Women tend to be better communicators

This is absolutely rewarded in business. The ability to hold meetings, understand people’s frustrations and confusions and explain in new terms so that they understand, and to pick up on priorities and pecking orders is absolutely essential to being successful, and women are good at these things because they require a certain amount of empathy.

In all of these fields, you need to be self-promoting

I mention this because, besides needing feedback and being good communicators, women tend to not be as self-promoting as men, and this is something that they should train themselves out of. Small things like not apologizing help, as does being very aware of taking credit for accomplishments. Where men tend to say, “then I did this…”, women tend to say, “then my group did this…”. I’m not advocating being a jerk, but I am advocating being hyper aware of language (including body language) and making sure you don’t single yourself out for not being a stand-out.

The tenure schedule sucks for women

I don’t think I need to add anything to this.

No “summers off” outside academics… but maybe that’s a good thing

Academics don’t actually take their summers off anyway. And typically the women are the ones who end up dealing more with the kids over the summer, which could be awesome if that’s what they want but also tends to add a bias in terms of who gets papers written.

How do I get a job like that?

Lots of people have written to me asking how to prepare themselves for a job in data science (I include finance in this category, but not the governmental institutions. I have no idea how to get a job at NASA or the NSA).

Get a Ph.D. (establish your ability to create)

I’m using “Ph.D.” as a placeholder here for something that proves you can do original creative building. But it’s a pretty good placeholder; if you don’t have a Ph.D. but you are a hacker and you’ve made something that works and does something new and clever, that may be sufficient too. But if you’ve just followed your nose, and done well in your courses then it will be difficult to convince someone to hire you. Doing the job well requires being able to create ad hoc methodology on the spot, because the assumptions in developed theory never actually happen with real data.

Know your way around a computer

Get to the point where you can make things work on your computer. Great if you know how unix and stuff like cronjobs (love that word) work, but at the very least know to google everything instead of bothering people.

Learn python or R, maybe java or C++

Python and R are the very basic tools of a data scientist, and they allow quick and dirty data cleaning, modeling, measuring, and forecasting. You absolutely need to know one of them, or at the very least matlab or SAS or STATA. The good news is that none of these are hard, they just take some time to get used to.

Acquire some data visualization skills

I would guess that half my time is spent visualizing my results in order to explain them to non-quants. A crucial skill (both the pictures and the explanations).

Learn basic statistics

And I mean basic. But on the other hand I mean really, really, learn it. So that when you come across something non-standard (and you will), you can rewrite the field to apply to your situation. So you need to have a strong handle on all the basic stuff.

Read up on machine learning

There are lots of machine learners out there, and they have a vocabulary all their own. Take the Stanford Machine Learning classor something to learn this language.

Emphasize your communication skills and follow-through

Most of the people you’ll be working with aren’t trained mathematicians, and they absolutely need to know that you will be able to explain your models to them. At the same time, it’s amazing how convincing it is when you tell someone, “I’m a really good communicator.” They believe you. This also goes back to my “do not be afraid to self-promote” theme.

Practice explaining what a confidence interval is

You’d be surprised how often this comes up, and you should be prepared, even in an interview. It’s a great way to prep for an interview: find someone who’s really smart, but isn’t a mathematician, and ask them to be skeptical. Then explain what a confidence interval is, while they complain that it makes no sense. Do this a bunch of times.

Other stuff

I wanted to throw in a few words about other related matters.

Data modeling is everywhere (good data modelers aren’t)

There’s an asston of data out there waiting to be analyzed. There are very few people that really know how to do this well.

The authority of the inscrutable

There’s also a lot of fraud out there, related to the fact that people generally are mathematically illiterate or are in any case afraid of or intimidated by math. When people want to sound smart they throw up an integral, and it’s a conversation stopper. It is a pretty evil manipulation, and it’s my opinion that mathematicians should be aware of this and try to stop it from happening. One thing you can do: explain that notation (like integrals) is a way of writing something in shorthand, the meaning of which you’ve already agreed on. Therefore, by definition, if someone uses notation without that prior agreement, it is utterly meaningless and adds rather than removes confusion.

Another aspect of the “authority of the inscrutable” is the overall way that people claimed to be measuring the risk of the mortgage-backed securities back before and during the credit crisis. The approach was, “hey you wouldn’t understand this, it’s math. But trust us, we have some wicked smart math Ph.D.’s back there who are thinking about this stuff.” This happens all the time in business and it’s the evil side of the superpower that is mathematics. It’s also easy to let this happen to you as a mathematician in business, because above all it’s flattering.

Open source data, open source modeling

I’m a huge proponent of having more visibility into the way that modeling affects us all in our daily lives (and if you don’t know that this is happening then I’ve got news for you). A particularly strong example is the Value-added modeling movement currently going on in this country which evaluates public teachers and schools. The models and training data (and any performance measurements) are proprietary. They should not be. If there’s an issue of anonymity, then go ahead and assign people randomly.

Not only should the data that’s being used to train the model be open source, but the model itself should be too, with the parameters and hyper-parameters in open-source code on a website that anyone can download and tweak. This would be a huge view into the robustness of the models, because almost any model has sub-modeling going on that dramatically affects the end result but that most modelers ignore completely as a source of error. Instead of asking them about that, just test it for yourself.

Meetups

The closest thing to academics lectures in data science is called “Meetups”. They are very cool. I wrote about them previously here. The point of them is to create a community where we can share our techniques (without giving away IP) and learn about new software packages. A huge plus for the mathematician in business, and also a great way to meet other nerds.

Data Without Borders

I also wanted to mention that, once you have a community of nerds such as is gathered at Meetups, it’s also nice to get them together with their diverse skills and interests and do something cool and valuable for the world, without it always being just about money. Data Without Borders is an organization I’ve become involved with that does just that, and there are many others as well.

Please feel free to comment or ask me more questions about any of this stuff. Hope it is helpful!

Alternative Banking System

I just got invited to join the Alternative Banking System working group from Occupy Wall Street. It’s run by Carne Ross, who has written a book called the Leaderless Revolution. I’m excited to meet the group this coming weekend. It looks like there will be many interesting and unconventional thinkers there.

I got back last night from my Cambridge, where I spoke to people about doing math in business. I will write up my notes from that talk soon and post them, and they will include my suggestions for how to prepare yourself to be a data scientist if you’re an academic mathematician. This is a first stab at a longer term project I have to define a possible “data science curriculum”.

Datadive update

I left my datadive team at 9:15pm last night hard at work, visualizing the data in various ways as well as finding interesting inconsistencies. I will try to post some actual results later, but I want to wait for them to be (somewhat) finalized. For now I can make some observations.

- First, I really can’t believe how cool it is to meet all of these friendly and hard-working nerds who volunteered their entire weekend to clean and dig through data. It’s a really amazing group and I’m proud of how much they’ve done.

- Second, about half of the data scientists are women. Awesome and unusual to see so many nerd women outside of academics!

- Third, data cleaning is hard work and is a huge part of the job of a data scientist. I should never forget that. Having said that, though, we might want to spend some time before the next datadive pre-cleaning and formatting the data so that people have more time to jump into the analytics. As it is we learned a lot about data cleaning as a group, but next time we could learn a lot about comparing methodology.

- Statistical software packages such as Stata have trouble with large (250MB) files compared to python, probably because of the way they put everything into memory at once. So it’s cool that everyone comes to a datadive with their own laptop and language, but some thought should be put into what project they work on depending on this information.

- We read Gelman, Fagan and Kiss’s article about using the Stop and Frisk data to understand racial profiling, with the idea that we could test it out on more data or modify their methodology to slightly change the goal. However, they used crime statistics data that we don’t have and can’t find and which are essential to a good study.

- As an example of how crucial crime data like this is, if you hear the statement, “10% of the people living in this community are black but 50% of the people stopped and frisked are black,” it sounds pretty damning, but if you add “50% of crimes are committed by blacks” then it sound less so. We need that data for the purpose of analysis.

- Why is crime statistics data so hard to find? If you go to NYPD’s site and search for crime statistics, you get really very little information, which is not broken down by area (never mind x and y coordinates) or ethnicity. That stuff should be publicly available. In any case it’s interesting that the Stop and Frisk data is but the crime stats data isn’t.

- Oh my god check out our wiki, I just looked and I’m seeing some pretty amazing graphics. I saw some prototypes last night and I happen to know that some of these visualizations are actually movies, showing trends over time. Very cool!

- One last observation: this is just the beginning. The data is out there, the wiki is set up, and lots of these guys want to continue their work after this weekend is over. That’s what I’m talking about.

NYCLU: Stop Question and Frisk data

As I mentioned yesterday, I’m the data wrangler for the Data Without Borders datadive this weekend. There are three N.G.O.’s participating: NYCLU (mine), MIX, and UN Global Pulse. The organizations all pitched their data and their questions last night to the crowd of nerds, and this morning we are meeting bright and early (8am) to start crunching.

I’m particularly psyched to be working with NYCLU on Stop and Frisk data. The women I met from NYCLU last night had spent time at Occupy Wall Street the previous day giving out water and information to the protesters. How cool!

The data is available here. It’s zipped in .por format, which is to say it was collected and used in SPSS, a language that’s not open source. I wanted to get it into csv format for the data miners this morning, but I have been having trouble. Sometimes R can handle .por files but at least my install of R is having trouble with the years 2006-2009. Then we tried installing PSPP, which is an open source version of SPSS, and it seemed to be able to import the .por files and then export as csv, in the sense that it didn’t throw any errors, but actually when we looked we saw major flaws. Finally we found a program called StatTransfer, which seems to work (you can download a trial version for free) but unless you pay $179 for the package, it actually doesn’t transfer all of the lines of the file for you.

If anyone knows how to help, please make a comment, I’ll be checking my comments. Of course there could easily be someone at the datadive with SPSS on their computer, which would solve everything, but on the other hand it could also be a major pain and we could waste lots of precious analyzing time with formatting issues. I may just buckle down and pay $179 but I’d prefer to find an open source solution.

UPDATE (9:00am): Someone has SPSS! We’re totally getting that data into csv format. Next step: set up Dropbox account to share it.

UPDATE (9:21am): Have met about 5 or 6 adorable nerds who are eager to work on this sexy data set. YES!

UPDATE (10:02am): People are starting to work in small groups. One guy is working on turning the x- and y-coordinates into latitude and longitude so we can use mapping tools easier. These guys are awesome.

UPDATE (11:37am): Now have a mapping team of 4. Really interesting conversations going on about statistically rigorous techniques for human rights abuses. Looking for publicly available data on crime rates, no luck so far… also looking for police officer id’s on data set but that seems to be missing. Looking also to extend some basic statistics to all of the data set and aggregated by months rather than years so we can plot trends. See it all take place on our wiki!

UPDATE (12:24pm): Oh my god, we have a map. We have officer ID’s (maybe). We have awesome discussions around what bayesian priors are reasonable. This is awesome! Lunch soon, where we will discuss our morning, plan for the afternoon, and regroup. Exciting!

UPDATE (2:18pm): Nice. We just had lunch, and I managed to get a sound byte about every current project, and it’s just amazing how many different things are being tried. Awesome. Will update soon.

UPDATE (7:10pm): Holy shit I’ve been inside crunching data all day while the world explodes around me.

Data Without Borders: datadive weekend!

I’m really excited to be a part of the datadive this weekend organized by Data Without Borders. From their website:

Selected NGOs will work with data enthusiasts over the weekend to better understand their data, create analyses and insights, and receive free consultations.

I’ve been asked to be a “data wrangler” at the event, which means I’m going to help project manage one of the projects of the weekend, which is super exciting. It means I get to hear about cool ideas and techniques as they happen. We’re expecting quite a few data scientists, so the amount of nerdiness should be truly impressive, as well as the range of languages and computing power. I’m borrowing a linux laptop since my laptop isn’t powerful enough for the large data and the crunching. I’ve got both python and R ready to go.

I can’t say (yet) who the N.G.O. is or what exactly the data is or what the related questions are, but let me say, very very cool. One huge reason I started this blog was to use data science techniques to answer questions that could actually really matter to people. This is my first real experience with that kind of non-commercial question and data set, and it’s really fantastic. The results of the weekend will be saved and open.

I’ll be posting over the weekend about the project as well as showing interim results, so stay tuned!

Bayesian regressions (part 2)

In my first post about Bayesian regressions, I mentioned that you can enforce a prior about the size of the coefficients by fiddling with the diagonal elements of the prior covariance matrix. I want to go back to that since it’s a key point.

Recall the covariance matrix represents the covariance of the coefficients, so those diagonal elements correspond to the variance of the coefficients themselves, which is a natural proxy for their size.

For example, you may just want to make sure the coefficients don’t get too big, or in other words there’s a penalty for large coefficients. Actually there’s a name for just having this prior, and it’s called L2 regularization. You just set the prior to be , where

is the identity matrix, and

is a tuning parameter- you can set the strength of the prior by turning

“up to eleven“.

You’re going to end up adding this prior to the actual sample covariance matrix as measured by the data, so don’t worry about the prior matrix being invertible (but definitely do make sure it’s symmetrical).

Moreover, you can have many different priors, corresponding to different parts of the covariance matrix, and you can add them all up together to get a final prior.

From my first post, I had two priors, both on the coefficients of lagged values of some time series. First, I expect the signal to die out logarithmically or something as we go back in time, so I expect the size of the coefficients to die down as a power of some parameter. In other words, I’ll actually have two parameters: one for the decrease on each lag and one overall tuning parameter. My prior matrix will be diagonal and the th entry will be of the form

for some

and for a tuning parameter

My second prior was that the entries should vary smoothly, which I claimed was enforceable by fiddling with the super and sub diagonals of the covariance matrix. This is because those entries describe the covariance between adjacent coefficients (and all of my coefficients in this simple example correspond to lagged values of some time series).

In other words, ignoring the variances of each variable (since we already have a handle on the variance from our first prior), we are setting a prior on the correlation between adjacent terms. We expect the correlation to be pretty high (and we can estimate it with historical data). I’ll work out exactly what that second prior is in a later post, but in the end we have two priors, both with tuning parameters, which we may be able to combine into one tuning parameter, which again determines the strength of the overall prior after adding the two up.

Because we are tamping down the size of the coefficients, as well as linking them through a high correlation assumption, the net effect is that we are decreasing the number of effective coefficients, and the regression has less work to do. Of course this all depends on how strong the prior is too; we could make the prior so weak that it has no effect, or we could make it so strong that the data doesn’t effect the result at all!

In my next post I will talk about combining priors with exponential downweighting.

Financial Terms Dictionary

I’ve got a bunch of things to mention today. First, I’ll be at M.I.T. in less than two weeks to give a talk to women in math about working in business. Feel free to come if you are around and interested!

Next, last night I signed up for this free online machine learning course being offered out of Stanford. I love this idea and I really think it’s going to catch on. There are groups here in New York that are getting together to talk about the class and do homework. Very cool!

Next, I’m going back to the protests after work. The media coverage has gotten better and Matt Stoller really wrote a great piece and called on people to stop criticizing and start helping, which is always my motto. For my part, I’m planning to set up some kind of Finance Q&A booth at the demonstration with some other friends of mine in finance. It’s going to be hard since I don’t have lots of time but we’ll try it and see. One of my artistic friends came up with this:

Finally, one last idea. I wanted to find a funny way to help people understand financial and economic stuff, so I thought of starting a “Financial Terms Dictionary”, which would start with an obscure phrase that economists and bankers use and translate it into plain English. For example, under “injection of liquidity” you might see “the act of printing money and giving it to the banks”.

Finally, one last idea. I wanted to find a funny way to help people understand financial and economic stuff, so I thought of starting a “Financial Terms Dictionary”, which would start with an obscure phrase that economists and bankers use and translate it into plain English. For example, under “injection of liquidity” you might see “the act of printing money and giving it to the banks”.

I’d love comments and suggestions for the Financial Terms Dictionary! I’ll start a separate page for it if it catches on.

Bayesian regressions (part 1)

I’ve decided to talk about how to set up a linear regression with Bayesian priors because it’s super effective and not as hard as it sounds. Since I’m not a trained statistician, and certainly not a trained Bayesian, I’ll be coming at it from a completely unorthodox point of view. For a more typical “correct” way to look at it see for example this book (which has its own webpage).

The goal of today’s post is to abstractly discuss “bayesian priors” and illustrate their use with an example. In later posts, though, I promise to actually write and share python code illustrating bayesian regression.

The way I plan to be unorthodox is that I’m completely ignoring distributional discussions. My perspective is, I have some time series (the ‘s) and I want to predict some other time series (the

) with them, and let’s see if using a regression will help me- if it doesn’t then I’ll look for some other tool. But what I don’t want to do is spend all day deciding whether things are in fact student-t distributed or normal or something else. I’d like to just think of this as a machine that will be judged on its outputs. Feel free to comment if this is palpably the wrong approach or dangerous in any way.

A “bayesian prior” can be thought of as equivalent to data you’ve already seen before starting on your dataset. Since we think of the signals (the ‘s) and response (

) as already known, we are looking for the most likely coefficients

that would explain it all. So the form a bayesian prior takes is: some information on what those

‘s look like.

The information you need to know about the ‘s is two-fold. First you need to know their values and second you need to have a covariance matrix to describe their statistical relationship to each other. When I was working as a quant, we almost always had strong convictions about the latter but not the former, although in the literature I’ve been reading lately I see more examples where the values (really the mean values) for the

‘s are chosen but with an “uninformative covariance assumption”.

Let me illustrate with an example. Suppose you are working on the simplest possible model: you are taking a single time series and seeing how earlier values of predict the next value of

. So in a given update of your regression,

and each

is of the form

for some