People hate me, I must be doing something right

Not sure if you’ve seen this recent New York Times article entitled Learning to Love Criticism, but go ahead and read it if you haven’t. The key figures:

…76 percent of the negative feedback given to women included some kind of personality criticism, such as comments that the woman was “abrasive,” “judgmental” or “strident.” Only 2 percent of men’s critical reviews included negative personality comments.

This is so true! I re-re-learned this recently (again) when I started podcasting on Slate and the iTunes reviews of the show included attacks on me personally. For example: “Felix is great but Cathy is just annoying… and is not very interesting on anything” as well as “The only problem seems to be Cathy O’Neill who doesn’t have anything to contribute to the conversation…”

By contrast the men on the show, Jordan and Felix, are never personally attacked, although Felix is sometimes criticized for interrupting people, mostly me. In other words, I have some fans too. I am divisive.

So, what’s going on here?

Well, I have a thick skin already, partly from blogging and partly from being in men’s fields all my life, and partly just because I’m an alpha female. So what that means is that I know that it’s not really about me when people anonymously complain that I’m annoying or dumb. To be honest, when I see something like that, which isn’t a specific criticism that might help me get better but is rather a vague attack on my character, I immediately discount it as sexism if not misogyny, and I feel pity for the women in that guy’s life. Sometimes I also feel pity for the guy too, because he’s stunted and that’s sad.

But there’s one other thing I conclude when I piss people off: that I’m getting under their skin, which means what I’m saying is getting out there, to a wider audience than just people who already agree with me, and if that guy hates me then maybe 100 other people are listening and not quite hating me. They might even be agreeing with me. They might even be changing their minds about some things because of my arguments.

So, I realize this sounds twisted, but when people hate me, I feel like I must be doing something right.

One other thing I’ll say, which the article brings up. It is a luxury indeed to be a woman who can afford to be hated. I am not at risk, or at least I don’t feel at all at risk, when other people hate me. They are entitled to hate me, and I don’t need to bother myself about getting them to like me. It’s a deep and wonderful fact about our civilization that I can say that, and I am very glad to be living here and now, where I can be a provocative and opinionated intellectual woman.

Fuck yes! Let’s do this, people! Let’s have ideas and argue about them and disagree! It’s what freedom is all about.

Chameleon models

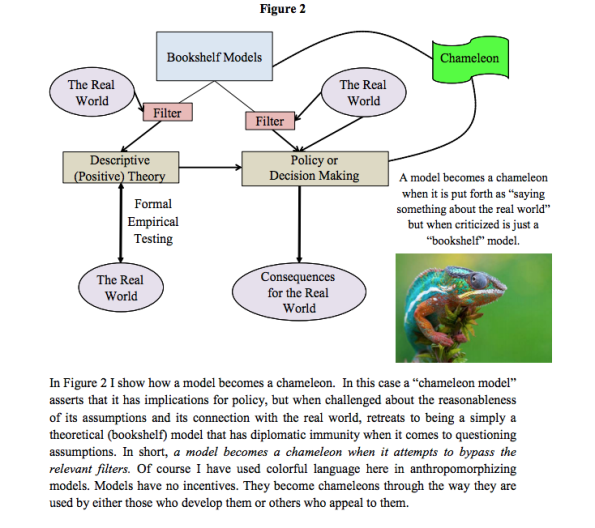

Here’s an interesting paper I’m reading this morning (hat tip Suresh Naidu) entitled Chameleons: The Misuse of Theoretical Models in Finance and Economics written by Paul Pfleiderer. The paper introduces the useful concept of chameleon models, defined in the following diagram:

Pfleiderer provides some examples of chameleon models, and also takes on the Milton Friedman argument that we shouldn’t judge a model by its assumptions but rather by its predictions (personally I think this is largely dependent on the way a model is used; the larger the stakes, the more the assumptions matter).

I like the term, and I think I might use it. I also like the point he makes that it’s really about usage. Most models are harmless until they are used as political weapons. Even the value-added teacher model could be used to identify school systems that need support, although in the current climate of distorted data due to teaching to the test and cheating, I think the signal is probably very slight.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Holy crap, peoples!

Aunt Pythia just counted up her readers’ questions and found super high quality (yay!) combined with super small quantity (boo!), a non-ideal situation. Do you know that there are currently fewer than two weeks’ worth of questions in the bin?! That means that next week might be extra short if nobody comes up with (sexual, optionally true) dilemmas between now and next Saturday.

It’s a situation!! If things don’t change Aunt Pythia will be forced to:

- Make up questions. Aunt Pythia has never done this but desperate times call for desperate measures.

- Force good friends to submit questions. Aunt Pythia has totally done this but it aint pretty.

- Answer questions that have been submitted to other advice columns. Aunt Pythia is actually kind of into this idea. Like, there are plenty of Dan Savage answers she disagrees with, although she loves the guy, obv.

So seriously consider mixing that shit up and:

Don’t forget to submit stolen question from old Dan Savage columns,

especially if you are one of Aunt Pythia’s good friends.

Got it? Good! Love ya!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have a question on your recent post entitled Gillian Tett gets it very wrong on racial profiling, when you say:

Specifically, this means that the fact that black Americans are nearly four times as likely as whites to be arrested on charges of marijuana possession even though the two groups use the drug at similar rates would be seen by such a model (or rather, by the people who deploy the model) as a fact of nature that is neutral and true. But it is in fact a direct consequence of systemic racism.”

Racism is not the only interpretation of data. Another possible explanation is that black Americans are less educated and cannot hide marijuana from the cops as well as whites. So it is a correlate, not a cause. Had president Obama done something about education in the US I don’t think we’d see such terrible racial disparity.

NYC_NUMBERS

Dear NYCN,

Not sure why this is an Aunt Pythia question instead of a comment on that post, but let me respond by, a “WHAA?”. Clearly black kids are much more educated about cops than the average white kids. Are you kidding?

But you do bring up a great point: white kids smoke pot in their own rooms in suburbia, and it’s harder for them to get caught. Black kids maybe don’t have privacy, so they end up doing more pot smoking in public, which means they get caught more. But obviously both whites and blacks walk around with pot in their pockets, so at the end of the day there’s serious racial bias.

This reminds me that I heard a group of Stuyvesant parents met with cops in the Stuy neighborhood and tried to make a deal that, when their kids were caught smoking pot in the nearby park, the cops would just bring them back to school rather than arresting them. Imagine that deal being made in Harlem.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I saw you asked some good questions at David Madigan’s IDSE Colloquium event this week. I thought it was a really compelling talk (and that Madigan is dreamy…). What were you reactions?

Anyways, when thinking about colloquium in the shower, I started to think about the word. It’s interesting that it’s essentially the same word as colloquial, yet to me they have opposite meanings. Do you think there’s truth to a colloquium really being colloquial?

Curious At the Colloquium

Dear Curious,

First of all, Madigan is awesome and I saw an earlier version of that talk before, in fact I wrote it up in Doing Data Science (Chapter 12). And yes, he’s indeed dreamy, a rare man of integrity. I am a groupie of his, and I don’t mind admitting it. After the talk I gave him a hug and felt a tingle.

Great question about the word colloquium. According to this online Oxford Dictionary, it basically just means “talk together”. Similarly, colloquial just means “conversational”. It makes sense. I wish more things were that informal combined with great.

I just got back from a Day of Data at Yale and I met a guy from the NIH, a really cool motorcycle-driving scientist in fact, and I told him all about Madigan. So I hope that helps the word get out too.

One question, what exactly were you doing in the shower whilst thinking about the talk? Just curious.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m returning back to teaching math after a long illness. I’m starting slow with a modest calculus course at a modest university, somewhere along the north atlantic coast. The budget crisis has taken its toll on the department. The students are barely prepared (serious gaps in algebra and trig.) I have 3 contact hours per week, no discussion sections, no graders.

I’m finding myself with a strange dilemma: should I cut lecturing down to a minimum and rely heavily on the book and youTube videos, while using most of class time for problem-solving and giving insightful examples, or should I go the other way: lecture and relegate homework and quizzes to the online platform that comes with the book.

Please help! I feel like I’m trying to tutor in the midst of lecture and run out of time every time.

Shy and Confounded

——

Dear Shy,

Given that there are serious gaps in their knowledge, I’d probably try to do at least a few worked-out examples with the students during class to make sure they can handle the mechanics of the solutions in addition to the conceptual ideas you’re presenting.

So maybe that means a 20 minute “review” of the new idea of the day, and then 40 minutes devoted to working out examples, with lots of interaction from the students so you can see what their gaps are and then make announcements about “things to remember”, basically showing them how to do stuff from algebra or trig.

Also consider asking them what is most useful for them to learn the stuff most efficiently in the three hours you have together. And finally, keep in mind that the quiet ones will probably be the ones that feel most behind, so make sure you don’t just listen to the loud people! Maybe a survey monkey?

But I definitely like your idea of offering them lots of online resources to get practice with this stuff if they are having trouble. I definitely think they should be encouraged to do that as well. Keep track of what works so next semester you have something to build on.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m just starting a tenure track job at a well-known place. Another more prestigious university is currently considering giving me a tenured full professorship. At what point do I mention this? I don’t want to mention it too early, because of course it might turn out nothing happens. But it does also seems like an opportunity for a market correction. Variation: How would a tall handsome man handle this?

Wanting Info on Negotiating Contract Extension

Dear WINCE,

I don’t think you can mention it until the offer is firm. I don’t think a tall man would either, however handsome.

The real question is, how do you handle the negotiation between the two places once they are both actively recruiting you? Some people would try to start a bidding war, some wouldn’t. But since I’m one of those people who wouldn’t, I’m not the right person to ask about how to do that. If you want advice about that, write back and I’ll get my good friend who is the king of bidding wars to weigh in.

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Women not represented in clinical trials

This recent NYTimes article entitled Health Researchers Will Get $10.1 Million to Counter Gender Bias in Studies spelled out a huge problem that kind of blows me away as a statistician (and as a woman!).

Namely, they have recently decided over at the NIH, which funds medical research in this country, that we should probably check to see how women’s health are affected by drugs, and not just men’s. They’ve decided to give “extra money” to study this special group, namely females.

Here’s the bizarre and telling explanation for why most studies have focused on men and excluded women:

Traditionally many investigators have worked only with male lab animals, concerned that the hormonal cycles of female animals would add variability and skew study results.

Let’s break down that explanation, which I’ve confirmed with a medical researcher is consistent with the culture.

If you are afraid that women’s data would “skew study results,” that means you think the “true result” is the result that works for men. Because adding women’s data would add noise to the true signal, that of the men’s data. What?! It’s an outrageous perspective. Let’s take another look at this reasoning, from the article:

Scientists often prefer single-sex studies because “it reduces variability, and makes it easier to detect the effect that you’re studying,” said Abraham A. Palmer, an associate professor of human genetics at the University of Chicago. “The downside is that if there is a difference between male and female, they’re not going to know about it.”

Ummm… yeah. So instead of testing the effect on women, we just go ahead and optimize stuff for men and let women just go ahead and suffer the side effects of the treatment we didn’t bother to study. After all, women only comprise 50.8% of the population, they won’t mind.

This is even true for migraines, where 2/3rds of migraine sufferers are women.

One reason they like to exclude women: they have periods, and they even sometimes get pregnant, which is confusing for people who like to have clean statistics (on men’s health). In fact my research contact says that traditionally, this bias towards men in clinical trials was said to protect women because they “could get pregnant” and then they’d be in a clinical trial while pregnant. OK.

I’d like to hear more about who is and who isn’t in clinical trials, and why.

The business of public education

I’ve been writing my book, and I’m on chapter 4 right now, which is tentatively entitled Feedback Loops In Education. I’m studying the enormous changes in primary and secondary education that have occurred since the “data-driven” educational reform movement started with No Child Left Behind in 2001.

Here’s the issue I’m having writing this chapter. Things have really changed in the last 13 years, it’s really incredible how much money and politics – and not education – are involved. In fact I’m finding it difficult to write the chapter without sounding like a wingnut conspiracy theorist. Because that’s how freaking nuts things are right now.

On the one hand you have the people who believe in the promise of educational data. They are often pro-charter schools, anti-tenure, anti-union, pro-testing, and are possibly personally benefitting from collecting data about children and then sold to commercial interests. Privacy laws are things to bypass for these people, and the way they think about it is that they are going to improve education with all this amazing data they’re collecting. Because, you know, it’s big data, so it has to be awesome. They see No Child Left Behind and Race To The Top as business opportunities.

On the other hand you have people who do not believe in the promise of educational data. They believe in public education, and are maybe even teachers themselves. They see no proven benefits of testing, or data collection and privacy issues for students, and they often worry about job security, and public shaming and finger-pointing, and the long term consequences on children and teachers of this circus of profit-seeking “educational” reformers. Not to mention that none of this recent stuff is addressing the very real problems we have.

As it currently stands, I’m pretty much part of the second group. There just aren’t enough data skeptics in the first group to warrant my respect, and there’s way too much money and secrecy around testing and “value-added models.” And the politics of the anti-tenure case are ugly and I say that even though I don’t think teacher union leaders are doing themselves many favors.

But here’s the thing, it’s not like there could never be well-considered educational experiments that use data and have strict privacy measures in place, the results of which are not saved to individual records but are lessons learned for educators, and, it goes without saying, are strictly non-commercial. There is a place for testing, but not as a punitive measure but rather as a way of finding where there are problems and devoting resources to it. The current landscape, however, is so split and so acrimonious, it’s kind of impossible to imagine something reasonable happening.

It’s too bad, this stuff is important.

When your genetic information is held against you

My friend Jan Zilinsky recently sent me this blogpost from the NeuroCritic which investigates the repercussions of having biomarkers held against individuals.

In this case, the biomarker was in the brain and indicated a propensity for taking financial risks. Or maybe it didn’t really – the case wasn’t closed – but that was the idea, and the people behind the research mentioned three times in 8 pages that policy makers might want to use already available brain scans to figure out which populations or individuals would be at risk. Here’s an excerpt from their paper:

Our finding suggests the existence of a simple biomarker for risk attitude, at least in the midlife [sic] population we examined in the northeastern United States. … If generalized to other groups, this finding will also imply that individual risk attitudes could, at least to some extent, be measured in many existing medical brain scans, potentially offering a tool for policy makers seeking to characterize the risk attitudes of populations.

The way the researchers did their tests was, as usual, to have them play artificial games of chance and see how different people strategized, and how their brains were different.

Here’s another article I found on biomarkers and risk for psychosis, here’s one on biomarkers and risk for PTSD.

Studies like this are common and I don’t see a reason they won’t become even more common. The question is how we’re going to use them. Here’s a nasty way I could imagine they get used: when you apply for a job, you fill in a questionnaire that puts you into a category, and then people can see what biomarkers are typical for that category, and what the related health risks look like, and then they can decide whether to hire you. Not getting hired doesn’t say anything about your behaviors, just what happens with “people like you”.

I’m largely sidestepping the issue of accuracy. It’s quite likely that, at an individual level, many such predictions will be inaccurate but could still be used by commercial interests – and even be profitable – even so.

In the best case scenario, we would use such knowledge strictly to help people stay healthy. In the worst case, we have a system whereby people are judged by their biomarkers and not their behavior. If there were ever a case for regulation, I think this is it.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

It was a long week! Very emotional!

And to top it all off, last night Aunt Pythia and her sweetie and some besties went to see – what else? – Ivo Van Hove’s adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From A Marriage. Aunt Pythia’s review of this deeply felt, Swedish introspection and investigation into the darkest corners of marital communication, and lack thereof, can be summarized in three words:

more sex, please.

Sadly, that may be the exact review you will give Aunt Pythia’s column today, although keep in mind she’s done her best to foster sex-related questions, and moreover she generously doles out sex-related advice, even when it isn’t called for.

So please have pity on her, and of course don’t forget to:

please think of something (sexual) to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m applying to some math PhD programs this fall. Some of the applications ask me to specify faculty members at that university whom I would like to work with, and I’ve also been given the general advice to reach out to professors at various schools in order to get my name out there and increase my chances of admission. I have a couple of questions about this:

1) I feel like professors must be inundated with these emails from applicants, and that this would be a really annoying aspect of being a professor. How can I be minimally annoying?

2) I feel like professors must know that students (including myself) are angling for admission offers and not necessarily driven by the pure motive of academic interest. I’m not suggesting that I would lie to or try to manipulate someone whose work I wasn’t interested in, but the truth is I have never before gone around contacting mathematicians who have published interesting papers, so it feels disingenuous to do so only now that I hope to gain something. Is there any way to do this without feeling dishonest? Also, should I be explicit about my intention to name-drop them on the application, or should I pretend my motives are less self-serving?

3) Although I have some general ideas about areas of math that interest me (e.g. Representation Theory), I don’t have a really specific idea about the kind of research or thesis I will do– and because I’m just starting out, I don’t have the background to understand the papers and research on these professors’ CV’s. Should I just contact people in Algebra or whatever field I’m thinking about, or do I need to decide that “I want to contribute to your research on specific esoteric topic X” or whatever?

Although I think I have a reasonably solid application in terms of GPA, test scores, and letters of recommendation, I have essentially no research background or professional networking. So I really would like to do whatever I can to bolster my chances of getting into a program. Any advice you can give would be much appreciated. Even if that advice is simply to forget about sending annoying requests to strangers and just apply with what I have.

Getting Responses About Doctorate

Dear GRAD,

Here’s the thing, people like to take students. So if you express interest in working with them, they will like it, while they will of course also know it’s partly because you want to get into grad school, but that’s okay and normal. Of course there are some people that already have too many students, or actually don’t like taking students, so if you are ignored don’t take it personally. But in general it’s a flattering introduction, and people like to be flattered.

Plus, at the end of the day math is a community of people, and the sooner you start getting to know the people the better. So I’d suggest you really do reach out to people and take a look around at their papers and do your best to understand the gist of them. Ideally you would be able to meet them in person, say at a visit to the department or something, but barring that introducing yourself over email is fine, as long as it’s not a form letter.

Tell them about what you’ve read of their work, what interests you, and mention that you’re graduating now and applying to grad schools. Not offensive. And good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m currently a math postdoc planning to transition to data science/something similar. The decision to leave academia hasn’t been easy, and one thing making it hard is that I really enjoy teaching. I particularly like teaching probability/stats/data analysis and I think the data journalism program you’re running is really cool! I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on (i) is it possible to stay involved in education in some form as a non-academic mathematician and (ii) if so, what to do to create these opportunities? I don’t plan to spend time on this early in my industry career as I need to establish myself professionally, but I hope to have opportunities to share what I love with others at some point down the line.

Pursuing A New Direction Actually

Dear PANDA,

The sign-offs are killing it today.

OK so I agree, the worst part about leaving academic math for industry is that you don’t get to teach, and teaching is super fun. I’ve made do with going to math camp every now and then to get a dose of teaching, and more recently I worked at the Lede Program in data journalism, which allowed me to teach as well.

Suggestion: tutoring? Taking a few weeks to work at summer programs? Signing up to teach night classes? Becoming an adjunct at a local university and teaching whatever? All these things are possible.

There are also quite a few data science training programs springing up around the country that you might be able to work at, so take a look at that as well. Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Aunt Pythia starts this recent column by saying “Aunt Pythia kind of blew her load, so to speak, on the sex questions last week”.

But on MY PC, there is no update between 9th and 30th August, so my question is “Where is the 23rd August sexfest?”

Seeks Titillating Internet Material

Dear STIM,

Here it is. I got there by going to the mathbabe.org front page and searching for “Aunt Pythia sex”. It’s really not that difficult, but I can understand why you might have been distracted. Plus, thank you for letting me link to that, it’s saving an otherwise sexless column.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a particle physics grad student who knows embarrassingly little about statistical analysis. For me, a significance of 5 sigma means a discovery, and 3 sigma stuff is ‘interesting’ (but almost always goes away with more data).

A while ago, I came upon this article. I am sure you heard/read about it. It basically says elite male-run labs hire female postdocs at 36%, while elite female-run labs hire female postdocs at 47% while the female postdocs are 39% of the pool. This is presented as “Male PIs don’t usually hire female postdocs”.

I was very confused when I read this, because to me male PIs were hiring at a level close to the average number of female postdocs available. As you can imagine, the female-run lab number is higher because there are ~20% female PIs in their data. So, that skews the numbers. They also give some significance (p-value) for their results, but how robust is the p-value? Or, what is the significant result here? Please give me a lecture on this!

Significance Is Greatly Mind Abusing

Dear SIGMA,

Physicists are kind of spoiled for data. They often just collect way more data than other people can, and their experiments don’t typically affect the results nearly as much, nor are they as messy, as you see in human experiments.

Anyway, a few points.

- I don’t understand your argument for why the female numbers are naturally skewed, unless you’re saying that there are so few data points that the averages tend to be far away from the expected average, which is true, but it could have just as well been below average, at least theoretically. Correct me if I’m mistaken.

- Not knowing more about this field, I don’t know the answer to a bunch of important questions I would ask. For example, do some fields expect you to work very long hours which would be tough for young mothers? Or are some fields for other reasons more friendly to women, for example if the hours were flexible, or if the wages were more transparent, or if the leaders of the field were more welcoming? All sorts of reasons that women might bunch together in certain fields and thus in certain labs.

- Most importantly, this paper seems to think there’s a natural experiment going on, but there almost never is. There are almost always confounding factors such as the above.

- So, if we really wanted to say men are less willing to hire women, we’d need to set up a randomized experiment and send a bunch of resumes that differ only in the gender of the applicant, and see what happens next.

- Having said all that, I didn’t actually read the paper, so I might be overly skeptical of the results. I have pancakes to make pretty quick so there’s a constraint in place here.

- In any case every time a randomized experiment has been performed, to my knowledge, there has been systemic sexism in place. So I wouldn’t be surprised if there is actual sexism at work here, even if I’m not convinced this is proof of it.

- Finally, you should take a look at t-tests, which you probably already know about, but here’s the reason: you can never get a 5-sigma results when your n is small. In other words, your test result, no matter what you do, is a function both of the amount of sexism that exists in a given lab and the number of labs you are evaluating, and you can’t do much about the latter even if the former is substantial.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Climate Convergence march on Sunday

This Sunday there’ll be a huge march to raise awareness about climate change. It’s called the Climate Convergence, and the Alternative Banking group is going to be there.

If you want to join us, come to 79th and Central Park West at 11am, in front of the Natural History Museum. We will have signs and a banner. See you there, I hope!

Why the NFL conversation about Ray Rice is so important to me

My first memory is of my father throwing a plate of eggs at my mother’s head, like a frisbee. My mother had to duck to get out of the way, and the plate exploded on the wall behind her. His eggs hadn’t been cooked well enough, and this was his way of expressing that to my mother, who had cooked them. Then he punched his hand through a glass window. Blood and glass fragments were everywhere. I was 4 years old. I remember running to my bed and crying, and the already familiar feeling of hiding in fear.

My mother was a battered woman who didn’t leave her abuser. And that meant a bunch of things for her and for me and my brother. I cannot explain her reasoning, because I was a small child when most of the abuse occurred. But I can tell you it’s common enough, and it’s not even that hard to understand.

One of the aspects of this decision – to stay with your abuser or not – that I haven’t been hearing a lot of recently, in this whole Ray Rice-inspired nationwide conversation about violence against women, is the economics of it. The worst of my father’s behavior happened when he was unemployed and desperately unhappy with how his life was turning out. Once he got on his feet again he didn’t take stuff out on his wife as much or as often. I imagine that is typical, but what it means is that it’s extra hard to imagine managing a second household, with small children, on one salary, when it’s already a huge struggle to manage one. The economic reality of leaving your husband has to be understood.

Even so, the abuse didn’t completely stop, and it’s not like my mother never considered leaving my father. I remember I went away for a month, to communist Budapest, when I was turning 13, the summer of 1985. When I came back my mother told me that my father had pushed her down the stairs. Then she asked me if she should leave him. I said yes, but then she didn’t do it.

I will probably never really forgive her for asking me that, for putting that kind of responsibility on a child like that, and then not following through. Especially now that I have kids of my own that age, it seems outrageous to put that kind of decision on their plate, or even seem to. It was my last day of childhood, the day I realized there were no responsible people in my family, and that I would have to step up and be the person who negotiated reasonable boundaries or, failing that, call the cops. From then on I was my mother and my brother’s protector.

If anyone ever asks me why I am not intimidated by anyone, I think of that moment. When you are a 13-year-old girl who has decided to stand up for your mother and brother against a large and very strong man, who often becomes an enraged and unreasonable bully, you forget about fear and intimidation, because it’s just something you cannot think about.

—

Many years later, after I left college, my father engaged me in a series of ritualized revisionist history lessons. Every Christmas, every Thanksgiving, maybe even on July 4th, he would bring up the bad old days and he’d mention how much I’d hated him when I was a teenager, and how he hadn’t deserved it, and how even when he’d been abusive to my mother, she had hit him first, and he hadn’t really wanted to do it but there it is. He often distorted facts, and he never explained why he was doing this.

It always sounded so bizarre to me – how could it matter that my mother had hit him first, not to mention that it was unbelievably hard to imagine? How could that be an excuse for what kind of fear and rage he had manifested on her body and on our family for so long? Answer: it isn’t an excuse.

It was very confusing, these inaccurate family history lessons in sermon form. It made me so angry I never could do anything except stay silent. I didn’t even correct him when he lied about the details, because he was evidently saying all of this more for him than for me.

It took me years to figure out why this conversation kept happening, but I think I finally know now. He was working through his guilt with me as his chosen audience. He was, in a sense, asking for my forgiveness. I never gave it, but what those conversations did accomplish for him was almost the same: he made it my problem for being so unkind as to not forgive him. After all, my mother had forgiven him, why couldn’t I? Looking back, I felt increasing pressure to forgive, but I never gave in. I didn’t even really know how.

Here’s why I’m thinking about this now. This Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson conversation, which I’ve been listening to on sports radio, has gotten me to thinking about this stuff. I am listening to these football guys, these pinnacles of macho masculinity, talking about men who abuse women and children, and describing it as unforgivable. Thank god for those men.

Because here’s the thing. It is unforgivable, but until now I hadn’t realized that I was allowed to think so. I’ve been feeling so guilty for so long at not being able to forgive my father, I never realized that I could just be okay with it. But now I do, and I don’t forgive him, and I never will.

—

After much deliberation, I’ve finally decided to publish this. To be clear, I’m not doing so to hurt my father or my mother. I’m writing it in hopes that by reading this, people will realize that this kind of thing happens everywhere, to all kinds of people, and that it’s always fucked up and wrong. We need to know that, the NFL needs to know that, and policy makers need to know that. We need to create stronger laws around this, that don’t buckle when the women refuse to press charges.

If this happened to you as a kid, it wasn’t your fault, and you don’t have to forgive if can’t or you don’t want to, and even if you don’t forgive them, you will probably still love them. Human beings are really good at conflicting emotions. Focus on not being like that yourself. My proudest accomplishment is that I have not perpetuated the cycle of violence on my own family. And good luck.

The green-eyed/ blue-eyed puzzle/ conundrum

Today I want to share a puzzle that my friend Aaron Abrams told me a few days ago. I’m sure some of you have heard it before, but it’s confusing me, so I’m asking for your help.

Set-up

Here’s the setup. There’s an island of people, all of whom have either blue eyes or green eyes. By social convention they never discuss eye color, because there’s a tragic rule that states that, if you ever figure out your eye color, you have to leave the island within 24 hours. Oh, and there are no mirrors.

OK, get it? So think of the island as pretty small, maybe 100 people, so you know everyone else’s eye color but not your own.

Here’s what happens next. Some castaway arrives by swimming onto the island, stays for a few days and hangs out with the folks there eating island food and having island parties, and then after building himself a boat he prepares to leave. Not being trained in the social customs of the island, on the day he leaves he says, “hey, it’s good to see some people with green eyes here!”.

Puzzle

So the puzzle is, what happens next?

Here’s what’s obvious. If you are a person who only sees blue eyes, you know by his statement that you must have green eyes. So you have to leave the next day.

But actually he said “some people.” So even if you only see one other person with green eyes, then you have to leave, with that other green-eyed person, after one day.

With me so far?

But hey, what if you see two other people with green eyes? Well, you might think you’re safe, and you’d wait to see them leave together the next day. But what if they don’t leave after one day? That must mean that you also have green eyes. Then all three of you have to leave, after two days. Get it?

Then you work by induction. If you see N other people with green eyes, they should all leave after N-1 days, or else you have green eyes too and all (N+1) of you leave after N days.

Conundrum

OK, so here’s the conundrum. The guy who started this whole mess really didn’t do much. He just stated what was obvious to everyone already on the island, namely that some people had green eyes. I mean, yes, if there were really only 2 people with green eyes, then he clearly added real information, because both those people had thought only 1 person had green eyes.

But just for the fun of it, let’s assume there were 17 people with green eyes. Then they guy really didn’t add information. And yet, 16 days after the guy left, so do all the green-eyed islanders. So really the guy just started a count-down more than anything.

So, is that it? Is that what happened? Or was the original set-up inconsistent? Is it not an equilibrium at all? Or is it an unstable equilibrium?

Saying

In any case, Aaron and his friend Jamie have developed a saying, it’s a green-eyed/ blue-eyed thing, which means it’s an apparently information-free fact which changes everything. I think I’ll use that.

Christian Rudder’s Dataclysm

Here’s what I’ve spent the last couple of days doing: alternatively reading Christian Rudder’s new book Dataclysm and proofreading a report by AAPOR which discusses the benefits, dangers, and ethics of using big data, which is mostly “found” data originally meant for some other purpose, as a replacement for public surveys, with their carefully constructed data collection processes and informed consent. The AAPOR folk have asked me to provide tangible examples of the dangers of using big data to infer things about public opinion, and I am tempted to simply ask them all to read Dataclysm as exhibit A.

Rudder is a co-founder of OKCupid, an online dating site. His book mainly pertains to how people search for love and sex online, and how they represent themselves in their profiles.

Here’s something that I will mention for context into his data explorations: Rudder likes to crudely provoke, as he displayed when he wrote this recent post explaining how OKCupid experiments on users. He enjoys playing the part of the somewhat creepy detective, peering into what OKCupid users thought was a somewhat private place to prepare themselves for the dating world. It’s the online equivalent of a video camera in a changing booth at a department store, which he defended not-so-subtly on a recent NPR show called On The Media, and which was written up here.

I won’t dwell on that aspect of the story because I think it’s a good and timely conversation, and I’m glad the public is finally waking up to what I’ve known for years is going on. I’m actually happy Rudder is so nonchalant about it because there’s no pretense.

Even so, I’m less happy with his actual data work. Let me tell you why I say that with a few examples.

Who are OKCupid users?

I spent a lot of time with my students this summer saying that a standalone number wouldn’t be interesting, that you have to compare that number to some baseline that people can understand. So if I told you how many black kids have been stopped and frisked this year in NYC, I’d also need to tell you how many black kids live in NYC for you to get an idea of the scope of the issue. It’s a basic fact about data analysis and reporting.

When you’re dealing with populations on dating sites and you want to conclude things about the larger culture, the relevant “baseline comparison” is how well the members of the dating site represent the population as a whole. Rudder doesn’t do this. Instead he just says there are lots of OKCupid users for the first few chapters, and then later on after he’s made a few spectacularly broad statements, on page 104 he compares the users of OKCupid to the wider internet users, but not to the general population.

It’s an inappropriate baseline, made too late. Because I’m not sure about you but I don’t have a keen sense of the population of internet users. I’m pretty sure very young kids and old people are not well represented, but that’s about it. My students would have known to compare a population to the census. It needs to happen.

How do you collect your data?

Let me back up to the very beginning of the book, where Rudder startles us by showing us that the men that women rate “most attractive” are about their age whereas the women that men rate “most attractive” are consistently 20 years old, no matter how old the men are.

Actually, I am projecting. Rudder never actually specifically tells us what the rating is, how it’s exactly worded, and how the profiles are presented to the different groups. And that’s a problem, which he ignores completely until much later in the book when he mentions that how survey questions are worded can have a profound effect on how people respond, but his target is someone else’s survey, not his OKCupid environment.

Words matter, and they matter differently for men and women. So for example, if there were a button for “eye candy,” we might expect women to choose more young men. If my guess is correct, and the term in use is “most attractive”, then for men it might well trigger a sexual concept whereas for women it might trigger a different social construct; indeed I would assume it does.

Since this isn’t a porn site, it’s a dating site, we are not filtering for purely visual appeal; we are looking for relationships. We are thinking beyond what turns us on physically and asking ourselves, who would we want to spend time with? Who would our family like us to be with? Who would make us be attractive to ourselves? Those are different questions and provoke different answers. And they are culturally interesting questions, which Rudder never explores. A lost opportunity.

Next, how does the recommendation engine work? I can well imagine that, once you’ve rated Profile A high, there is an algorithm that finds Profile B such that “people who liked Profile A also liked Profile B”. If so, then there’s yet another reason to worry that such results as Rudder described are produced in part as a result of the feedback loop engendered by the recommendation engine. But he doesn’t explain how his data is collected, how it is prompted, or the exact words that are used.

Here’s a clue that Rudder is confused by his own facile interpretations: men and women both state that they are looking for relationships with people around their own age or slightly younger, and that they end up messaging people slightly younger than they are but not many many years younger. So forty year old men do not message twenty year old women.

Is this sad sexual frustration? Is this, in Rudder’s words, the difference between what they claim they want and what they really want behind closed doors? Not at all. This is more likely the difference between how we live our fantasies and how we actually realistically see our future.

Need to control for population

Here’s another frustrating bit from the book: Rudder talks about how hard it is for older people to get a date but he doesn’t correct for population. And since he never tells us how many OKCupid users are older, nor does he compare his users to the census, I cannot infer this.

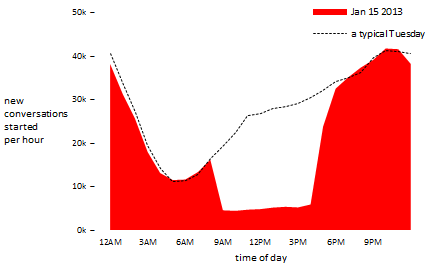

Here’s a graph from Rudder’s book showing the age of men who respond to women’s profiles of various ages:

We’re meant to be impressed with Rudder’s line, “for every 100 men interested in that twenty year old, there are only 9 looking for someone thirty years older.” But here’s the thing, maybe there are 20 times as many 20-year-olds as there are 50-year-olds on the site? In which case, yay for the 50-year-old chicks? After all, those histograms look pretty healthy in shape, and they might be differently sized because the population size itself is drastically different for different ages.

Confounding

One of the worst examples of statistical mistakes is his experiment in turning off pictures. Rudder ignores the concept of confounders altogether, which he again miraculously is aware of in the next chapter on race.

To be more precise, Rudder talks about the experiment when OKCupid turned off pictures. Most people went away when this happened but certain people did not:

Some of the people who stayed on went on a “blind date.” Those people, which Rudder called the “intrepid few,” had a good time with people no matter how unattractive they were deemed to be based on OKCupid’s system of attractiveness. His conclusion: people are preselecting for attractiveness, which is actually unimportant to them.

But here’s the thing, that’s only true for people who were willing to go on blind dates. What he’s done is select for people who are not superficial about looks, and then collect data that suggests they are not superficial about looks. That doesn’t mean that OKCupid users as a whole are not superficial about looks. The ones that are just got the hell out when the pictures went dark.

Race

This brings me to the most interesting part of the book, where Rudder explores race. Again, it ends up being too blunt by far.

Here’s the thing. Race is a big deal in this country, and racism is a heavy criticism to be firing at people, so you need to be careful, and that’s a good thing, because it’s important. The way Rudder throws it around is careless, and he risks rendering the term meaningless by not having a careful discussion. The frustrating part is that I think he actually has the data to have a very good discussion, but he just doesn’t make the case the way it’s written.

Rudder pulls together stats on how men of all races rate women of all races on an attractiveness scale of 1-5. It shows that non-black men find their own race attractive and non-black men find black women, in general, less attractive. Interesting, especially when you immediately follow that up with similar stats from other U.S. dating sites and – most importantly – with the fact that outside the U.S., we do not see this pattern. Unfortunately that crucial fact is buried at the end of the chapter, and instead we get this embarrassing quote right after the opening stats:

And an unintentionally hilarious 84 percent of users answered this match question:

Would you consider dating someone who has vocalized a strong negative bias toward a certain race of people?

in the absolute negative (choosing “No” over “Yes” and “It depends”). In light of the previous data, that means 84 percent of people on OKCupid would not consider dating someone on OKCupid.

Here Rudder just completely loses me. Am I “vocalizing” a strong negative bias towards black women if I am a white man who finds white women and asian women hot?

Especially if you consider that, as consumers of social platforms and sites like OKCupid, we are trained to rank all the products we come across to ultimately get better offerings, it is a step too far for the detective on the other side of the camera to turn around and point fingers at us for doing what we’re told. Indeed, this sentence plunges Rudder’s narrative deeply into the creepy and provocative territory, and he never fully returns, nor does he seem to want to. Rudder seems to confuse provocation for thoughtfulness.

This is, again, a shame. A careful conversation about the issues of what we are attracted to, what we can imagine doing, and how we might imagine that will look to our wider audience, and how our culture informs those imaginings, are all in play here, and could have been drawn out in a non-accusatory and much more useful way.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Do you know what Aunt Pythia has been occupied with recently? Yes, you guessed it, she has a fantabulous new knitting pattern and she just can’t get enough of it. Here’s a recent work-in-progress pic:

I hope you know how much Aunt Pythia must love you considering how hard it was to tear herself away from such a beautiful project. So please, love her back, and after loving her madly, don’t forget to:

please think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

My dear Aunt Pythia propagating loving introspective nerdy girls,

This morning, I am going to imagine sitting in between your lovely kids to enjoy crepes and vent with you. Today’s vent is that I have been highly disturbed by this week’s coverage of the Fields medal (putting aside for the moment the question of whether the Fields medal should exist in the first place). One article I read compared being female in math with being a handicapped competitive athlete.

WTF? This is the news that is being reported and the way people are reacting? What is the most healthy way I can respond to this and still enjoy my Saturday morning crepes?

Love,

SINGing Introspective Nerdy Girl

P.S. I also read the following social media post of a male scientist: “I know I’ll get shit for this, but doesn’t it seem a bit weird that the first woman to win this is butch and wears men’s clothing? Is this because she has a man’s brain, or because she got chosen because she’s man-like?”

I’m not sure it would be a good idea to publicize this, but I would like to ask how I should respond in this situation (feel free to paraphrase the quote if you see fit). I would personally love to publicly shame the male scientist, but I also wanted to make sure I am responding in a way that is helpful and positive to anybody who is reading my message.

In case you are able to see his Facebook posts, the male scientist is “Brian Raney” at USC.

Dear SINGING,

Hmmm… not sure what I can add to this post about the topic, but here goes.

I guess the best way to think about this is as a totally non-mathematical PR thing, which is heavily steeped in weird and fucked up expectations due to historical sexism. As for the USC guy, it would obviously have been infinitely better for him to say something like, “Maryam was awarded the Fields Medal because she did some incredible stellar mathematics.” But there you go, some people miss opportunities to say the right thing. Or maybe he first said the right thing and then he added a bunch of other things after that, who knows. I don’t even care enough to check on his Facebook page. Who cares about what one random guys says?

As for overall butchiness and wearing men’s clothes, lots of female mathematicians do that (including myself many days!), and it’s actually not an uninteresting observation about women in math and other STEM fields, but the phenomenon is certainly not limited to Fields Medal winners.

If you don’t mind me going off into a slight tangent (thanks!), let me also mention that men’s clothes are, generally speaking, great for looking totally unobjectionable, not getting harassed or hit on, and not evoking catcalls (a big deal here in NYC!) compared to short skirts and high heels, and if men could wear them they totally would. Oh wait, they already do.

My point being, there are lots of reasonable reasons to wear men’s clothes besides being a lesbian (although being a lesbian is of course a great reason! And please include suspenders when possible! Fetching!). Being taken seriously as a scholar comes to mind. I defend everyone’s rights to trousers and a boring button-down shirt.

Or, you know, a short skirt and heels if you wanna sex it up and get some attention. Or for the more full-figured gal, a bodycon dress:

The key is to get what you want, when you want it.

Keep singing!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a 24-year-old young woman in New York and I consider myself pretty lucky to absolutely LOVE my job as a “data analyst”. I make great money, my boss trusts me in a sort of crazy way, I can work remotely whenever I want to, and after 6 months, I’ve come to truly believe that my company is an awesome place to work and a pretty great group of people (I guess you could say I’ve been drinking the free chai tea + almond milk). Though I did balk for a second and wonder if I’m just a SQL database monkey, I’m proud to say that if I have to spend 1/7 of my day in SQL but get to spend the rest of it messing around with Python pandas and learning to be a command line ninja, give me a banana and call me Koko.

Now, I won’t have this autonomy forever. This is only my first job, and we’re rapidly expanding, which includes building out an ACTUAL data science department. Without going into too much detail, our platform currently delivers some basic analytics to our customers, and we want to beef up these metrics into something they value us for and, ideally, become dependent on.

We are hiring a director (read: a new boss for me) and we’ve interviewed a ton of people. As you’ve mentioned, a good data scientist is hard to find! I’m pretty outspoken and have spoken up about presenting our clients our with not-quite-as-accurate-as-I-myself-would-like metrics (and I drink chai tea here, not the kool aid). I think I could be a GOOD data scientist someday, but I need the right person to guide me. Most of these candidates are Google Analytics or Tableau jockeys who don’t have any interest in my sweet matplotlib graphs with opacity depending on client billing amount! circumference depending on length of time with us! and so forth.

Last week, I met a candidate that I KNOW will never be topped. She (SHE!!) is also outspoken, knows her shit, cares about data AND ALSO cares about stuff besides data (!) and just is certainly my perfect Yoda. Unfortunately, because the job market is a real thing and a good data scientist is hard to find, I fear that she will not take this job in favor of a better offer elsewhere, financially or otherwise (probably just a bigger company with more data than mine).

Aunt Pythia, HOW do I get her to choose my small company?? This feels to me like the kind of career-changing, perhaps even LIFE changing moment that you have to do EVERYTHING you can to make happen. What would you advise a young woman to do? I have scruples in life, but am not above planting bed bugs at the offices of her competing offer.

Most Enthusiastic Neophyte To Ever Enquire

Dear MENTEE,

You are seriously awesome and you don’t need a Yoda to tell you that, although we’d all love a Yoda.

Here’s the thing. I sense in you the power to be a great data scientist someday, not because your fave boss will or will not take that job, but because you have the obvious urge to do something cool and fun with your life, and because you have integrity, and because you are too smart to trick yourself into thinking what you’re doing is great when it isn’t. Trust in yourself. And if your company doesn’t hire someone awesome, go find yourself another job. Keep learning, keep striving.

Love always,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a junior mathematician just starting to navigate the depth of academia. I am so disillusioned by what I see. I thought being a mathematician was supposed to be this wonderful thing, wherein I exchange ideas with people of similar interests, make friends, and not working but playing.

Instead, I have met so many mean people, who hide what they are doing from me, some who ignore me because they don’t think that I’m good enough, and some who try to intimidate me. When I was a grad student, I even had a student by the same advisor, who never spoke to me once while we were students together, except to try to embarrass me during my talks.

While there are nice people in academia, and I still love being a mathematician, I sometimes become really sad about the mean people in academia. Sometimes, I feel so disillusioned and burned out, then I am too upset to be thinking about math. I feel that I would be so much more productive if only I could deal with these feelings, and I am often frustrated by the fact. Is leaving academia my only solution?

Disillusioned

Dear Disillusioned,

You are right on all accounts! You would be more productive if you could deal with these feelings, and people are mean, and leaving academia would help, although not in the way you think.

Here’s the thing. I left academic math in part because people were so mean. They were really mean to me, and especially because I was a woman, and especially because I was married to a man who was highly respected. It was a situation.

But after leaving academics, mostly what I’ve realized is how most places contain mean people, and academics are really not all that good at being mean. No offense to mean mathematicians! But really they are like, small-fry mean. If you want to see hugely assholic behavior, work in finance for a few years.

So I’m wondering if this might help – and it might not, of course – but if you can, engage in the following thought experiment: you have left academics, and you go into some other field, and people are mean there too, except for a few nice people with whom you can bitch about the meanies. Then you leave that job and go in search of another job, where maybe there are fewer assholes but also you don’t get paid as well and there are other problems that come up because of that, or because the job stability is rough, or etc. etc.

Then after that long thought experiment, you might realize that as long as there are resources to be fought over, there will be fights, and the question is how to ignore all the stupid bickering and get some math done, because after all math is beautiful and awesome and it’s not math’s fault that all these people are mean.

Good luck!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My colleagues and I at the Militant Grammarians of Massachusetts would like to know why the word “data” is plural while the phrase “big data” is singular.

Your singular,

Big Datum

Dear Big Datum,

OK here’s where I am on this issue. It’s always singular. Always. Look at the data! All the data points to the same conclusion! There might be several data points that offer alternative preferences, but those are outliers. Every time I hear someone say something incredibly awkward like, “Are your organization’s data as clear as they can be?” I just wanna retch. Don’t do it. You just sound like a grammar nazi, and nobody likes those people.

You asked!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

What’s next for mathbabe?

The Columbia J-School program that I have been directing, The Lede Program in Data Journalism, has wound down this past week and in four days my 6-month contract with Columbia will end. I’ve had a fantastic time and I am super proud of what we accomplished this past summer. The students from the program are awesome and many of them are now my friends. About half of them are still engaged in classes and will continue to work this semester with Jonathan Soma, who absolutely rocks, and of course my fabulous colleague Theresa Bradley, who will step in as Director now that I’m leaving.

So, what’s next? I am happy to say that as of today (or at least as of next Monday when my kids are really in school full-time) I’m writing my book Weapons of Math Destruction on a full-time basis. This comes as a huge relief, since the internal pressure I have to finish this book is reminiscent of how I felt when I needed to write my thesis: enormous, but maybe even worse than then since the timeliness of the book could not be overstated, and I want to get this book out before the moment passes.

In the meantime I have some cool talks I’m planning to go to (like this one I went to already!) and some I’m planning to give. So for example, I’m giving a keynote at The Yale Day of Data later this month, which is going to be fun and interesting.

My Yale talk is basically a meditation on what can be achieved by academic data science institutions, what presents cultural and technical obstacles to collaboration, and why we need to do it anyway. It’s no less than a plea for Yale to create a data science institute with a broad definition of data science – so including scholars from law and from journalism as well as the fields you think of already when you think of data science – and a broad mandate to have urgent conversations across disciplines about the “big data revolution.” That conversation has already begun at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School, which makes me optimistic.

I also plan to continue my weekly Slate Money podcasts with Felix Salmon and Jordan Weissmann. Today we’re discussing the economic implications of Scottish independence, Felix’s lifetime earnings calculator, and the Fed’s new liquidity rules and how they affect municipalities, which my friend Marc Joffe guest blogged about yesterday.

Guest post: New Federal Banking Regulations Undermine Obama Infrastructure Stance

This is a guest post by Marc Joffe, a former Senior Director at Moody’s Analytics, who founded Public Sector Credit Solutions in 2011 to educate the public about the risk – or lack of risk – in government securities. Marc published an open source government bond rating tool in 2012 and launched a transparent credit scoring platform for California cities in 2013. Currently, Marc blogs for Bitvore, a company which sifts the internet to provide market intelligence to municipal bond investors.

Obama administration officials frequently talk about the need to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Yet new regulations published by the Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC run counter to this policy by limiting the market for municipal bonds.

On Wednesday, bank regulators published a new rule requiring large banks to hold a minimum level of high quality liquid assets (HQLAs). This requirement is intended to protect banks during a financial crisis, and thus reduce the risk of a bank failure or government bailout. Just about everyone would agree that that’s a good thing.

The problem is that regulators allow banks to use foreign government securities, corporate bonds and even stocks as HQLAs, but not US municipal bonds. Unless this changes, banks will have to unload their municipal holdings and won’t be able to purchase new state and local government bonds when they’re issued. The new regulation will thereby reduce the demand for bonds needed to finance roads, bridges, airports, schools and other infrastructure projects. Less demand for these bonds will mean higher interest rates.

Municipal bond issuance is already depressed. According to data from SIFMA, total municipal bonds outstanding are lower now than in 2009 – and this is in nominal dollar terms. Scary headlines about Detroit and Puerto Rico, rating agency downgrades and negative pronouncements from market analysts have scared off many investors. Now with banks exiting the market, the premium that local governments have to pay relative to Treasury bonds will likely increase.

If the new rule had limited HQLA’s to just Treasuries, I could have understood it. But since the regulators are letting banks hold assets that are as risky as or even riskier than municipal bonds, I am missing the logic. Consider the following:

- No state has defaulted on a general obligation bond since 1933. Defaults on bonds issued by cities are also extremely rare – affecting about one in one thousand bonds per year. Other classes of municipal bonds have higher default rates, but not radically different from those of corporate bonds.

- Bonds issued by foreign governments can and do default. For example, private investors took a 70% haircut when Greek debt was restructured in 2012.

- Regulators explained their decision to exclude municipal bonds because of thin trading volumes, but this is also the case with corporate bonds. On Tuesday, FINRA reported a total of only 6446 daily corporate bond trades across a universe of perhaps 300,000 issues. So, in other words, the average corporate bond trades less than once per day. Not very liquid.

- Stocks are more liquid, but can lose value very rapidly during a crisis as we saw in 1929, 1987 and again in 2008-2009. Trading in individual stocks can also be halted.

Perhaps the most ironic result of the regulation involves municipal bond insurance. Under the new rules, a bank can purchase bonds or stock issued by Assured Guaranty or MBIA – two major municipal bond insurers – but they can’t buy state and local government bonds insured by those companies. Since these insurance companies would have to pay interest and principal on defaulted municipal securities before they pay interest and dividends to their own investors, their securities are clearly more risky than the insured municipal bonds.

Regulators have expressed a willingness to tweak the new HQLA regulations now that they are in place. I hope this is one area they will reconsider. Mandating that banks hold safe securities is a good thing; now we need a more data-driven definition of just what safe means. By including municipal securities in HQLA, bank regulators can also get on the same page as the rest of the Obama administration.

Wife beating education for sports fan and everyone else

Do you know what I am doing this morning? I’m glued to ESPN talk radio, which is 98.7FM in the NYC area, although it is a national station and can be streamed online as well.

Here’s a statement you might be surprised to hear from me. In the past decade, sports talk radio has become the best, rawest, and most honest source of information about how our culture condones and ignores violence against women, not to mention issues of race and homophobia. True fact. You are not going to hear this stuff from politicians or academics.

Right now I’m listening to the Mike & Mike program, which has guest Jemele Hill, who is killing it. I’m a huge fan of hers.

The specific trigger for the conversation today is the fact that NFL football player Ray Rice has been indefinitely suspended from playing now that a video has emerged of him beating his wife in the elevator. Previously we had only gotten to seen the video of her slumped body after he came out of the elevator with her. The police didn’t do much about it, and then the NFL responded with a paltry 2-game suspension, after which there was such a backlash (partly through sports radio!) that the commissioner promised to enact a stronger policy.

Questions being addressed right now as I type:

- Why didn’t the police give Rice a bigger penalty for beating his wife unconscious?

- Why didn’t the NFL ask for that video before now? Or did they, and now they’re lying?

- What does it say about the NFL that they had the wife, Janay Rice, apologize for her role in the incident?

- What did people think it would look like when a professional football player knocks out a woman?

- Did people really think she did something to deserve it, and now they are shocked to see that she didn’t?

Reverse-engineering the college admissions process

I just finished reading a fascinating article from Bloomberg BusinessWeek about a man who claims to have reverse-engineered the admission processes at Ivy League colleges (hat tip Jan Zilinsky).

His name is Steven Ma, and as befits an ex-hedge funder, he has built an algorithm of sorts to work well with both the admission algorithms at the “top 50 colleges,” and the US News & World Report model which defines which colleges are in the “to 50.” It’s a huge modeling war that you can pay to engage in.

Ma is a salesman too: he guarantees that a given high-school kid will get into a top school, your money back. In other words he has no problem working with probabilities and taking risks that he think are likely to pay off and that make the parents willing to put down huge sums. Here’s an example of a complicated contract he developed with one family:

After signing an agreement in May 2012, the family wired Ma $700,000 over the next five months—before the boy had even applied to college. The contract set out incentives that would pay Ma as much as $1.1 million if the son got into the No. 1 school in U.S. News’ 2012 rankings. (Harvard and Princeton were tied at the time.) Ma would get nothing, however, if the boy achieved a 3.0 GPA and a 1600 SAT score and still wasn’t accepted at a top-100 college. For admission to a school ranked 81 to 100, Ma would get to keep $300,000; schools ranked 51 to 80 would let Ma hang on to $400,000; and for a top-50 admission, Ma’s payoff started at $600,000, climbing $10,000 for every rung up the ladder to No. 1.

He’s also interested in reverse-engineering the “winning essay” in conjunction with after-school activities:

With more capital—ThinkTank’s current valuation to potential investors is $60 million—Ma hopes to buy hundreds of completed college applications from the students who submitted them, along with the schools’ responses, and beef up his algorithm for the top 50 U.S. colleges. With enough data, Ma plans to build an “optimizer” that will help students, perhaps via an online subscription, choose which classes and activities they should take. It might tell an aspiring Stanford applicant with several AP classes in his junior year that it’s time to focus on becoming president of the chess or technology club, for example.

This whole college coaching industry reminds me a lot of financial regulation. We complicate the rules to the point where only very well-off insiders know exactly how to bypass the rules. To the extent that getting into one of these “top schools” actually does give young people access to power, influence, and success, it’s alarming how predictable the whole process has become.

Here’s a thought: maybe we should have disclosure laws about college coaching and prep? Or would those laws be gamed too?

Aunt Pythia gives it up for Polly

Dearest readers. Dearest, dearest readers. Aunt Pythia was just about to crack open her dog-eared google doc of questions when she happened across this Ask Polly column which blew her away (hat tip Julie Steele).

It’s entitled Ask Polly: Why Don’t the Men I Date Ever Truly Love Me? and it’s just about the best advice Aunt Pythia has ever seen for a whole lot of people, men and women. In fact she’s seriously considering stealing certain phrases out of this one column for future use, including the following:

- Is it time to stop being so good and start discovering what’s going to transform your life into something big and vibrant and shocking?

- Block the “other” from this picture. No more audience. You are the cherished and the cherisher.

- Fuck wondering if you’re lovable. Fuck asking someone else, “Am I there yet?” Fuck listening for the answer.

Bravo, Polly! And readers, please go read it.

Friday morning reading

I’m very gratified to say that my Lede Program for data journalism at Columbia is over, or at least the summer program is (some students go on to take Computer Science classes in the Fall).

My adorable and brilliant students gave final presentations on Tuesday and then we had a celebration Tuesday night at my house, and my bluegrass band played (didn’t know I have a bluegrass band? I play the fiddle! You can follow us on twitter!). It was awesome! I’m hoping to get some of their projects online soon, and I’ll definitely link to it when that happens.

It’s been an exciting week, and needless to say I’m exhausted. So instead of a frothy rant I’ll just share some reading with y’all:

- Andrew Gelman has a guest post by Phil Price on the worst infographic ever, which sadly comes from Vox. My students all know better than this. Hat tip Lambert Strether.

- Private equity firms are buying stuff all over the country, including Ferguson. I’m actually not sure this is a bad thing, though, if nobody else is willing to do it. Please discuss.

- Bloomberg has an interesting story about online PayDay loans and the world of investing. I am still on the search for someone who knows exactly how those guys target their ads online. Hat tip Aryt Alasti.

- Felix Salmon, now at Fusion, has set up a nifty interactive to help you figure out your lifetime earnings.

- Felix also set up this cool online game where you can play as a debt collector or a debtor.

- Is it time to end letter grades? Hat tip Rebecca Murphy.

- There’s a reason fast food workers are striking nationwide. The ratio of average CEO pay to average full-time worker pay is around 1252.

- People lie to women in negotiations. I need to remember this.

Have a great weekend!

Student evaluations: very noisy data

I’ve been sent this recent New York Times article by a few people (thanks!). It’s called Grading Teachers, With Data From Class, and it’s about how standardized tests are showing themselves to be inadequate to evaluate teachers, so a Silicon Valley-backed education startup called Panorama is stepping into the mix with a data collection process focused on student evaluations.

Putting aside for now how much this is a play for collecting information about the students themselves, I have a few words to say about the signal which one gets from student evaluations. It’s noisy.

So, for example, I was a calculus teacher at Barnard, teaching students from all over the Columbia University community (so, not just women). I taught the same class two semesters in a row: first in Fall, then in Spring.

Here’s something I noticed. The students in the Fall were young (mostly first semester frosh), eager, smart, and hard-working. They loved me and gave me high marks on all categories, except of course for the few students who just hated math, who would typically give themselves away by saying “I hate math and this class is no different.”

The students in the Spring were older, less eager, probably just as smart, but less hard-working. They didn’t like me or the class. In particular, they didn’t like how I expected them to work hard and challenge themselves. The evaluations came back consistently less excited, with many more people who hated math.

I figured out that many of the students had avoided this class and were taking it for a requirement, didn’t want to be there, and it showed. And the result was that, although my teaching didn’t change remarkably between the two semesters, my evaluations changed considerably.

Was there some way I could have gotten better evaluations from that second group? Absolutely. I could have made the class easier. That class wanted calculus to be cookie-cutter, and didn’t particularly care about the underlying concepts and didn’t want to challenge themselves. The first class, by contrast, had loved those things.

My conclusion is that, once we add “get good student evaluations” to the mix of requirements for our country’s teachers, we are asking for them to conform to their students’ wishes, which aren’t always good. Many of the students in this country don’t like doing homework (in fact most!). Only some of them like to be challenged to think outside their comfort zone. We think teachers should do those things, but by asking them to get good student evaluations we might be preventing them from doing those things. A bad feedback loop would result.

I’m not saying teachers shouldn’t look at student evaluations; far from it, I always did and I found them useful and illuminating, but the data was very noisy. I’d love to see teachers be allowed to see these evaluations without there being punitive consequences.

Guest Post: Bring Back The Slide Rule!

This is a guest post by Gary Cornell, a mathematician, writer, publisher, and recent founder of StemForums.

I was was having a wonderful ramen lunch with the mathbabe and, as is all too common when two broad minded Ph.D.’s in math get together, we started talking about the horrible state math education is in for both advanced high school students and undergraduates.

One amusing thing we discovered pretty quickly is that we had independently come up with the same (radical) solution to at least part of the problem: throw out the traditional sequence which goes through first and second year calculus and replace it with a unified probability, statistics, calculus course where the calculus component was only for the smoothest of functions and moreover the applications of calculus are only to statistics and probability. Not only is everything much more practical and easier to motivate in such a course, students would hopefully learn a skill that is essential nowadays: how to separate out statistically good information from the large amount of statistical crap that is out there.

Of course, the downside is that the (interesting) subtleties that come from the proofs, the study of non-smooth functions and for that matter all the other stuff interesting to prospective physicists like DiffEQ’s would have to be reserved for different courses. (We also were in agreement that Gonick’s beyond wonderful“Cartoon Guide To Statistics” should be required reading for all the students in these courses, but I digress…)