Archive

How math departments hire faculty

I just got back from a stimulating trip to Stony Brook to give the math colloquium there. I had a great time thanks to my gracious host Jason Starr (this guy, not this guy), and besides giving my talk (which I will give again in San Diego at the joint meetings next month) I enjoyed two conversations about the field of math which I think could be turned into data science projects. Maybe Ph.D. theses or something.

First, a system for deciding whether a paper on the arXiv is “good.” I will post about that on another day because it’s actually pretty involved and possible important.

Second is the way people hire in math departments. This conversation will generalize to other departments, some more than others.

So first of all, I want to think about how the hiring process actually works. There are people who look at folders of applicants, say for tenure-track jobs. Since math is a pretty disjointed field, a majority of the folders will only be understood well enough for evaluation purposes by a few people in the department.

So in other words, the department naturally splits into clusters more or less along field lines: there are the number theorists and then there are the algebraic geometers and then there are the low-dimensional topologists, say.

Each group of people reads the folders from the field or fields that they have enough expertise in to understand. Then from among those they choose some they want to go to bat for. It becomes a political battle, where each group tries to convince the other groups that their candidates are more qualified. But of course it’s really hard to know who’s telling the honest truth. There are probably lots of biases in play too, so people could be overstating their cases unconsciously.

Some potential problems with this system:

- if you are applying to a department where nobody is in your field, nobody will read your folder, and nobody will go to bat for you, even if you are really great. An exaggeration but kinda true.

- in order to be convincing that “your guy is the best applicant,” people use things like who the advisor is or which grad school this person went to more than the underlying mathematical content.

- if your department grows over time, this tends to mean that you get bigger clusters rather than more clusters. So if you never had a number theorist, you tend to never get one, even if you get more positions. This is a problem for grad students who want to become number theorists, but that probably isn’t enough to affect the politics of hiring.

So here’s my data science plan: test the above hypotheses. I said them because I think they are probably true, but it would be not be impossible to create the dataset to test them thoroughly and measure the effects.

The easiest and most direct one to test is the third: cluster departments by subject by linking the people with their published or arXiv’ed papers. Watch the department change over time and see how the clusters change and grow versus how it might happen randomly. Easy peasy lemon squeazy if you have lots of data. Start collecting it now!

The first two are harder but could be related to the project of ranking papers. In other words, you have to define “is really great” to do this. It won’t mean you can say with confidence that X should have gotten a job at University Y, but it would mean you could say that if X’s subject isn’t represented in University Y’s clusters, then X’s chances of getting a job there, all other things being equal, is diminished by Z% on average. Something like that.

There are of course good things about the clustering. For example, it’s not that much fun to be the only person representing a field in your department. I’m not actually passing judgment on this fact, and I’m also not suggesting a way to avoid it (if it should be avoided).

Unequal or Unfair: Which Is Worse?

This is a guest post by Alan Honick, a filmmaker whose past work has focused primarily on the interaction between civilization and natural ecosystems, and its consequences to the sustainability of both. Most recently he’s become convinced that fairness is the key factor that underlies sustainability, and has embarked on a quest to understand how our notions of fairness first evolved, and what’s happening to them today. I posted about his work before here. This is crossposted from Pacific Standard.

Inequality is a hot topic these days. Massive disparities in wealth and income have grown to eye-popping proportions, triggering numerous studies, books, and media commentaries that seek to explain the causes of inequality, why it’s growing, and its consequences for society at large.

Inequality triggers anger and frustration on the part of a shrinking middle class that sees the American Dream slipping from its grasp, and increasingly out of the reach of its children. But is it inequality per se that actually sticks in our craw?

There will always be inequality among humans—due to individual differences in ability, ambition, and more often than most would like to admit, luck. In some ways, we celebrate it. We idolize the big winners in life, such as movie and sports stars, successful entrepreneurs, or political leaders. We do, however (though perhaps with unequal ardor) feel badly for the losers—the indigent and unfortunate who have drawn the short straws in the lottery of life.

Thus, we accept that winning and losing are part of life, and concomitantly, some level of inequality.

Perhaps it’s simply the extremes of inequality that have changed our perspective in recent years, and clearly that’s part of the explanation. But I put forward the proposition that something far more fundamental is at work—a force that emerges from much deeper in our evolutionary past.

Take, for example, the recent NFL referee lockout, where incompetent replacement referees were hired to call the games.There was an unrestrained outpouring of venom from outraged fans as blatantly bad calls resulted in undeserved wins and losses. While sports fans are known for the extremity of their passions, they accept winning and losing; victory and defeat are intrinsic to playing a game.

What sparked the fans’ outrage wasn’t inequality—the win or the loss. Rather, the thing they couldn’t swallow—what stuck in their craw—was unfairness.

I offer this story from the KLAS-TV News website. It’s a Las Vegas station, and appropriately, the story is about how the referee lockout affected gamblers. It addresses the most egregiously bad call of the lockout, in a game between the Seattle Seahawks and the Green Bay Packers. From the story:

In a call so controversial the President of the United States weighed in, Las Vegas sports bettors said they lost out on a last minute touchdown call Monday night…

….Chris Barton, visiting Las Vegas from Rhode Island, said he lost $1,200 on the call against Green Bay. He said as a gambler, he can handle losing, “but not like that.”

“I’ve been gambling for 30 years almost, and that’s the worst defeat ever,” he said.

By the way, Obama’s “weigh-in” was through his Twitter feed, which I reproduce here:

“NFL fans on both sides of the aisle hope the refs’ lockout is settled soon. –bo”

When questioned about the president’s reaction, his press secretary, Jay Carney, said Obama thought “there was a real problem with the call,” and said the president expressed frustration at the situation.

I think this example is particularly instructive, simply because money’s involved, and money—the unequal distribution of it—is where we began.

Fairness matters deeply to us. The human sense of fairness can be traced back to the earliest social-living animals. One of its key underlying components is empathy, which began with early mammals. It evolved through processes such as kin selection and reciprocal altruism, which set us on the path toward the complex societies of today.

Fairness—or lack of it—is central to human relationships at every level, from a marriage between two people to disputes involving war and peace among the nations of the world.

I believe fairness is what we need to focus on, not inequality—though I readily acknowledge that high inequality in wealth and income is corrosive to society. Why that is has been eloquently explained by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkerson in their book, The Spirit Level. The point I have been trying to make is that inequality is the symptom; unfairness is the underlying disease.

When dealing with physical disease, it’s important to alleviate suffering by treating painful symptoms, and inequality can certainly be painful to those who suffer at the lower end of the wage scale, or with no job at all. But if we hope for a lasting cure, we need to address the unfairness that causes it.

That said, creating a fairer society is a daunting challenge. Inequality is relatively easy to understand—it’s measurable by straightforward statistics. Fairness is a subtler concept. Our notions of fairness arise from a complex interplay between biology and culture, and after 10,000 years of cultural evolution, it’s often difficult to pick them apart.

Yet many researchers are trying. They are looking into the underlying components of the human sense of fairness from a variety of perspectives, including such disciplines as behavioral genetics, neuroscience, evolutionary and developmental psychology, animal behavior, and experimental economics.

In order to better understand fairness, and communicate their findings to a larger audience, I’ve embarked on a multimedia project to work with these researchers. The goal is to synthesize different perspectives on our sense of fairness, to paint a clearer picture of its origins, its evolution, and its manifestations in the social, economic, and political institutions of today.

The first of these multimedia stories appeared here at Pacific Standard. Called The Evolution of Fairness, it is about archaeologist Brian Hayden. It explores his central life work—a dig in a 5000 year old village in British Columbia, where he uncovered evidence of how inequality may have first evolved in human society.

I found another story on a CNN blog about the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. In it, Paul Ryan compares the unfair refereeing to President Obama’s poor handling of the economy. He says, “If you can’t get it right, it’s time to get out.” He goes on to say, “Unlike the Seattle Seahawks last night, we want to deserve this victory.”

We now know how that turned out, though we don’t know if Congressman Ryan considers his own defeat a deserved one.

I’ll close with a personal plea to President Obama. I hope—and believe—that as you are starting your second term, you are far more frustrated with the unfairness in our society than you were with the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. It’s arguable that some of the rules—such as those governing campaign finance—have themselves become unfair. In any case, if the rules that govern society are enforced by bad referees, fairness doesn’t stand much of a chance, and as we’ve seen, that can make people pretty angry.

Please, for the sake of fairness, hire some good ones.

Can we put an ass-kicking skeptic in charge of the SEC?

The SEC has proven its dysfunctionality. Instead of being on top of the banks for misconduct, it consistently sets the price for it at below cost. Instead of examining suspicious records to root out Ponzi schemes, it ignores whistleblowers.

I think it’s time to shake up management over there. We need a loudmouth skeptic who is smart enough to sort through the bullshit, brave enough to stand up to bullies, and has a strong enough ego not to get distracted by threats about their future job security.

My personal favorite choice is Neil Barofsky, author of Bailout (which I blogged about here) and former Special Inspector General of TARP. Simon Johnson, Economist at MIT, agrees with me. From Johnson’s New York Times Economix blog:

… Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector general in charge of oversight for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. A career prosecutor, Mr. Barofsky tangled with the Treasury officials in charge of handing out support for big banks while failing to hold the same banks accountable — for example, in their treatment of homeowners. He confronted these powerful interests and their political allies repeatedly and on all the relevant details – both behind closed doors and in his compelling account, published this summer: “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.”

His book describes in detail a frustration with the timidity and lack of sophistication in law enforcement’s approach to complex frauds. He could instantly remedy that if appointed — Mr. Barofsky is more than capable of standing up to Wall Street in an appropriate manner. He has enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the past and could be confirmed by the Senate (just as he was previously confirmed to his TARP position).

Barofsky isn’t the only person who would kick some ass as the head of the SEC – William Cohan thinks Eliot Spitzer would make a fine choice, and I agree. From his Bloomberg column (h/t Matt Stoller):

The idea that only one of Wall Street’s own can regulate Wall Street is deeply disturbing. If Obama keeps Walter on or appoints Khuzami or Ketchum, we would be better off blowing up the SEC and starting over.

I still believe the best person to lead the SEC at this moment remains former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer. He would fearlessly hold Wall Street accountable for its past sins, as he did when he was New York State attorney general and as he now does as a cable television host. (Disclosure: I am an occasional guest on his show.)

We need an SEC head who can inspire a new generation of investors to believe the capital markets are no longer rigged and that Wall Street cannot just capture every one of its Washington regulators.

Diophantus and the math arXiv

Last night my 7th-grade son, who is working on a school project about the mathematician Diophantus, walked into the living room with a mopey expression.

He described how Diophantus worked on a series of mathematical texts called Arithmetica, in which he described the solutions to what we now describe as diophantine equations, but which are defined as polynomial equations with strictly integer coefficients, and where the solutions we care about are also restricted to be integers. I care a lot about this stuff because it’s what I studied when I was an academic mathematician, and I still consider this field absolutely beautiful.

What my son was upset about, though, was that of the 13 original books in Arhtimetica, only 6 have survived. He described this as “a way of losing progress“. I concur: Diophantus was brilliant, and there may be things we still haven’t recovered from that text.

But it also struck me that my son would be right to worry about this idea of losing progress even today.

We now have things online and often backed up, so you’d think we might never need to worry about this happening again. Moreover, there’s something called the arXiv where mathematicians and physicists put all or mostly all their papers before they’re published in journals (and many of the papers never make it to journals, but that’s another issue).

My question is, who controls this arXiv? There’s something going on here much like Josh Wills mentioned last week in Rachel Schutt’s class (and which Forbes’s Gil Press responded to already).

Namely, it’s not all that valuable to have one unreviewed, unpublished math paper in your possession. But it’s very valuable indeed to have all the math papers written in the past 10 years.

If we lost access to that collection, as a community, we will have lost progress in a huge way.

Note: I’m not accusing the people who run arXiv of anything weird. I’m sure they’re very cool, and I appreciate their work in keeping up the arXiv. I just want to acknowledge how much power they have, and how strange it is for an entire field to entrust that power to people they don’t know and didn’t elect in a popular vote.

As I understand it (and I could be wrong, please tell me if I am), the arXiv doesn’t allow crawlers to make back-ups of the documents. I think this is a mistake, as it increases the public reliance on this one resource. It’s unrobust in the same way it would be if the U.S. depended entirely on its food supply from a country whose motives are unclear.

Let’s not lose Arithmetica again.

How do we quantitatively foster leadership?

I was really impressed with yesterday’s Tedx Women at Barnard event yesterday, organized by Nathalie Molina, who organizes the Athena Mastermind group I’m in at Barnard. I went to the morning talks to see my friend and co-author Rachel Schutt‘s presentation and then came home to spend the rest of the day with my kids, but they other three I saw were also interesting and food for thought.

Unfortunately the videos won’t be available for a month or so, and I plan to blog again when they are for content, but I wanted to discuss an issue that came up during the Q&A session, namely:

what we choose to quantify and why that matters, especially to women.

This may sound abstract but it isn’t. Here’s what I mean. The talks were centered around the following 10 themes:

- Inspiration: Motivate, and nurture talented people and build collaborative teams

- Advocacy: Speak up for yourself and on behalf of others

- Communication: Listen actively; speak persuasively and with authority

- Vision: Develop strategies, make decisions and act with purpose

- Leverage: Optimize your networks, technology, and financing to meet strategic goals; engage mentors and sponsors

- Entrepreneurial Spirit: Be innovative, imaginative, persistent, and open to change

- Ambition: Own your power, expertise and value

- Courage: Experiment and take bold, strategic risks

- Negotiation: Bridge differences and find solutions that work effectively for all parties

- Resilience: Bounce back and learn from adversity and failure

The speakers were extraordinary and embodied their themes brilliantly. So Rachel spoke about advocating for humanity through working with data, and this amazing woman named Christa Bell spoke about inspiration, and so on. Again, the actual content is for another time, but you get the point.

A high school teacher was there with five of her female students. She spoke eloquently of how important and inspiring it was that these girls saw these talk. She explained that, at their small-town school, there’s intense pressure to do well on standardized tests and other quantifiable measures of success, but that there’s essentially no time in their normal day to focus on developing the above attributes.

Ironic, considering that you don’t get to be a “success” without ambition and courage, communication and vision, or really any of the themes.

In other words, we have these latent properties that we really care about and are essential to someone’s success, but we don’t know how to measure them so we instead measure stuff that’s easy to measure, and reward people based on those scores.

By the way, I’m not saying we don’t also need to be good at content, and tasks, which are easier to measure. I’m just saying that, by focusing on content and tasks, and rewarding people good at that, we’re not developing people to be more courageous, or more resilient, or especially be better advocates of others.

And that’s where the women part comes in. Women, especially young women, are sensitive to the expectations of the culture. If they are getting scored on X, they tend to focus on getting good at X. That’s not a bad thing, because they usually get really good at X, but we have to understand the consequences of it. We have to choose our X’s well.

I’d love to see a system evolve wherein young women (and men) are trained to be resilient and are rewarded for that just as they’re trained to do well on the SAT’s and rewarded for that. How do you train people to be courageous? I’m sure it can be done. How crazy would it be to see a world where advocating for others is directly encouraged?

Let’s try to do this, and hell let’s quantify it too, since that desire, to quantify everything, is not going away. Instead of giving up because important things are hard to quantify, let’s just figure out a way to quantify them. After all, people didn’t think their musical tastes could be quantified 15 years ago but now there’s Pandora.

Update: Ok to quantify this, but the resulting data should not be sold or publicly available. I don’t want our sons’ and daughters’ “resilience scores” to be part of their online personas for everyone to see.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is overwhelmed with joy today, readers, and not only because she gets to refer to herself in the third person.

The number and quality of math book suggestions from last week have impressed Auntie dearly, and with the permission of mathbabe, which wasn’t hard to get, she established a new page with the list of books, just in time for the holiday season. I welcome more suggestions as well as reviews.

On to some questions. As usual, I’ll have the question submission form at the end. Please put your questions to Aunt Pythia, that’s what she’s here for!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I was one of those kids who when asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” said “Errrghm …” or maybe just ignored the question. Today I am still that confused toddler. I have changed fields a few times (going through a major makeover right now), never knew what I want to dive into, found too many things too interesting. I worry that half a life from now, I will have done lots and nothing. I crave having a passion, one goal – something to keep trying to get better at. What advice do you have for the likes of me?

Forever Yawning or Wandering Globetrotter

Dear FYoWG,

I can relate. I am constantly yearning to have enough time to master all sorts of skills that I just know would make me feel fulfilled and satisfied, only to turn around and discover yet more things I’d love to devote myself to. What ever happened to me learning to flatpick the guitar? Why haven’t I become a production Scala programmer?

It’s enough to get you down, all these unrealized hopes and visions. But don’t let it! Remember that the people who only ever want one thing in life are generally pretty bored and pretty boring. And also remember that it’s better to find too many things too interesting than it is to find nothing interesting.

And also, I advise you to look back on the stuff you have gotten done, and first of all give yourself credit for those things, and second of all think about what made them succeed: probably something like the fact that you did it gradually but consistently, you genuinely liked doing it and learning from it, and you had the resources and environment for it to work.

Next time you want to take on a new project, ask yourself if all of those elements are there, and then ask yourself what you’d be dropping if you took it on. You don’t have to have definitive answers to these questions, but even having some idea will help you decide how realistic it is, and will also make you feel more like it’s a decision rather than just another thing you won’t feel successful at.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My boss lacks leadership qualities and is untrustworthy, and I will resign soon. Should I tell his boss what I think of this boss?

Novembertwentyeleven

Dear November,

In Aunt Pythia’s humble opinion, one of the great joys of life is the exit interview. Why go out with a whimper when you have the opportunity to go out with a big-ass ball of flame?

Let’s face it, it’s a blast to vent honestly and thoroughly on your way out the door, and moreover it’s expected. Why else would you be leaving? Because of some goddamn idiot, that’s why! Why not say who?

You’ll hear people say not to “burn bridges”. That’s boooooooring. I say, burn those motherfuckers to the ground!

Especially when you’re talking about people with whom you’d never ever work again, ever ever. Sometimes you just know it’ll never happen. And it feels great, trust me. I’m a pro.

That said, don’t expect anyone to listen to you, cuz that aint gonna happen. Nobody listens to people when they leave. Sadly, most people also don’t listen to people when they stay, either, so you’re shit out of luck in any case. But as long as you know that you’re good.

I hope that helped!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How should I organize my bookshelf? I have 1000+ books.

Booknerd

Readers! I want some suggestions, and please make them nerdy and/or funny! I know I can count on you.

——

Please ask Aunt Pythia a question! She loves her job and can’t wait to give you unreasonable, useless, and possibly damaging counsel!

How to build a model that will be gamed

I can’t help but think that the new Medicare readmissions penalty, as described by the New York Times, is going to lead to wide-spread gaming. It has all the elements of a perfect gaming storm. First of all, a clear economic incentive:

Medicare last month began levying financial penalties against 2,217 hospitals it says have had too many readmissions. Of those hospitals, 307 will receive the maximum punishment, a 1 percent reduction in Medicare’s regular payments for every patient over the next year, federal records show.

It also has the element of unfairness:

“Many of us have been working on this for other reasons than a penalty for many years, and we’ve found it’s very hard to move,” Dr. Lynch said. He said the penalties were unfair to hospitals with the double burden of caring for very sick and very poor patients.

“For us, it’s not a readmissions penalty,” he said. “It’s a mission penalty.”

And the smell of politics:

In some ways, the debate parallels the one on education — specifically, whether educators should be held accountable for lower rates of progress among children from poor families.

“Just blaming the patients or saying ‘it’s destiny’ or ‘we can’t do any better’ is a premature conclusion and is likely to be wrong,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, director of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at Yale-New Haven Hospital, which prepared the study for Medicare. “I’ve got to believe we can do much, much better.”

Oh wait, we already have weird side effects of the new rule:

With pressure to avert readmissions rising, some hospitals have been suspected of sending patients home within 24 hours, so they can bill for the services but not have the stay counted as an admission. But most hospitals are scrambling to reduce the number of repeat patients, with mixed success.

Note, the new policy is already a kind of reaction to gaming that’s already there, namely because of the stupid way Medicare decides how much to pay for treatment (emphasis mine):

Hospitals’ traditional reluctance to tackle readmissions is rooted in Medicare’s payment system. Medicare generally pays hospitals a set fee for a patient’s stay, so the shorter the visit, the more revenue a hospital can keep. Hospitals also get paid when patients return. Until the new penalties kicked in, hospitals had no incentive to make sure patients didn’t wind up coming back.

How about, instead of adding a weird rule that compromises people’s health and especially punishes poor sick people and the hospitals that treat them, we instead improve the original billing system? Otherwise we are certain to see all sorts of weird effects in the coming years with people being stealth readmitted under different names or something, or having to travel to different hospitals to be seen for their congestive heart failure.

Columbia Data Science course, week 13: MapReduce

The week in Rachel Schutt’s Data Science course at Columbia we had two speakers.

The first was David Crawshaw, a Software Engineer at Google who was trained as a mathematician, worked on Google+ in California with Rachel, and now works in NY on search.

David came to talk to us about MapReduce and how to deal with too much data.

Thought Experiment

Let’s think about information permissions and flow when it comes to medical records. David related a story wherein doctors estimated that 1 or 2 patients died per week in a certain smallish town because of the lack of information flow between the ER and the nearby mental health clinic. In other words, if the records had been easier to match, they’d have been able to save more lives. On the other hand, if it had been easy to match records, other breaches of confidence might also have occurred.

What is the appropriate amount of privacy in health? Who should have access to your medical records?

Comments from David and the students:

- We can assume we think privacy is a generally good thing.

- Example: to be an atheist is punishable by death in some places. It’s better to be private about stuff in those conditions.

- But it takes lives too, as we see from this story.

- Many egregious violations happen in law enforcement, where you have large databases of license plates etc., and people who have access abuse it. In this case it’s a human problem, not a technical problem.

- It’s also a philosophical problem: to what extent are we allowed to make decisions on behalf of other people?

- It’s also a question of incentives. I might cure cancer faster with more medical data, but I can’t withhold the cure from people who didn’t share their data with me.

- To a given person it’s a security issue. People generally don’t mind if someone has their data, they mind if the data can be used against them and/or linked to them personally.

- It’s super hard to make data truly anonymous.

MapReduce

What is big data? It’s a buzzword mostly, but it can be useful. Let’s start with this:

You’re dealing with big data when you’re working with data that doesn’t fit into your compute unit. Note that’s an evolving definition: big data has been around for a long time. The IRS had taxes before computers.

Today, big data means working with data that doesn’t fit in one computer. Even so, the size of big data changes rapidly. Computers have experienced exponential growth for the past 40 years. We have at least 10 years of exponential growth left (and I said the same thing 10 years ago).

Given this, is big data going to go away? Can we ignore it?

No, because although the capacity of a given computer is growing exponentially, those same computers also make the data. The rate of new data is also growing exponentially. So there are actually two exponential curves, and they won’t intersect any time soon.

Let’s work through an example to show how hard this gets.

Word frequency problem

Say you’re told to find the most frequent words in the following list: red, green, bird, blue, green, red, red.

The easiest approach for this problem is inspection, of course. But now consider the problem for lists containing 10,000, or 100,000, or words.

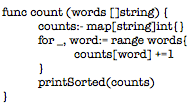

The simplest approach is to list the words and then count their prevalence. Here’s an example code snippet from the language Go:

Since counting and sorting are fast, this scales to ~100 million words. The limit is now computer memory – if you think about it, you need to get all the words into memory twice.

We can modify it slightly so it doesn’t have to have all words loaded in memory. keep them on the disk and stream them in by using a channel instead of a list. A channel is something like a stream: you read in the first 100 items, then process them, then you read in the next 100 items.

Wait, there’s still a potential problem, because if every word is unique your program will still crash; it will still be too big for memory. On the other hand, this will probably work nearly all the time, since nearly all the time there will be repetition. Real programming is a messy game.

But computers nowadays are many-core machines, let’s use them all! Then the bandwidth will be the problem, so let’s compress the inputs… There are better alternatives that get complex. A heap of hashed values has a bounded size and can be well-behaved (a heap seems to be something like a poset, and I guess you can throw away super small elements to avoid holding everything in memory). This won’t always work but it will in most cases.

Now we can deal with on the order of 10 trillion words, using one computer.

Now say we have 10 computers. This will get us 100 trillion words. Each computer has 1/10th of the input. Let’s get each computer to count up its share of the words. Then have each send its counts to one “controller” machine. The controller adds them up and finds the highest to solve the problem.

We can do the above with hashed heaps too, if we first learn network programming.

Now take a hundred computers. We can process a thousand trillion words. But then the “fan-in”, where the results are sent to the controller, will break everything because of bandwidth problem. We need a tree, where every group of 10 machines sends data to one local controller, and then they all send to super controller. This will probably work.

But… can we do this with 1000 machines? No. It won’t work. Because at that scale one or more computer will fail. If we denote by the variable which exhibits whether a given computer is working, so

means it works and

means it’s broken, then we can assume

But this means, when you have 1000 computers, that the chance that no computer is broken is which is generally pretty small even if

is small. So if

for each individual computer, then the probability that all 1000 computers work is 0.37, less than even odds. This isn’t sufficiently robust.

We address this problem by talking about fault tolerance for distributed work. This usually involves replicating the input (the default is to have three copies of everything), and making the different copies available to different machines, so if one blows another one will still have the good data. We might also embed checksums in the data, so the data itself can be audited for erros, and we will automate monitoring by a controller machine (or maybe more than one?).

In general we need to develop a system that detects errors, and restarts work automatically when it detects them. To add efficiency, when some machines finish, we should use the excess capacity to rerun work, checking for errors.

Q: Wait, I thought we were counting things?! This seems like some other awful rat’s nest we’ve gotten ourselves into.

A: It’s always like this. You cannot reason about the efficiency of fault tolerance easily, everything is complicated. And note, efficiency is just as important as correctness, since a thousand computers are worth more than your salary. It’s like this:

- The first 10 computers are easy,

- The first 100 computers are hard, and

- The first 1,000 computers are impossible.

There’s really no hope. Or at least there wasn’t until about 8 years ago. At Google I use 10,000 computers regularly.

In 2004 Jeff and Sanjay published their paper on MapReduce (and here’s one on the underlying file system).

MapReduce allows us to stop thinking about fault tolerance; it is a platform that does the fault tolerance work for us. Programming 1,000 computers is now easier than programming 100. It’s a library to do fancy things.

To use MapReduce, you write two functions: a mapper function, and then a reducer function. It takes these functions and runs them on many machines which are local to your stored data. All of the fault tolerance is automatically done for you once you’ve placed the algorithm into the map/reduce framework.

The mapper takes each data point and produces an ordered pair of the form (key, value). The framework then sorts the outputs via the “shuffle”, and in particular finds all the keys that match and puts them together in a pile. Then it sends these piles to machines which process them using the reducer function. The reducer function’s outputs are of the form (key, new value), where the new value is some aggregate function of the old values.

So how do we do it for our word counting algorithm? For each word, just send it to the ordered with the key that word and the value being the integer 1. So

red —> (“red”, 1)

blue —> (“blue”, 1)

red —> (“red”, 1)

Then they go into the “shuffle” (via the “fan-in”) and we get a pile of (“red”, 1)’s, which we can rewrite as (“red”, 1, 1). This gets sent to the reducer function which just adds up all the 1’s. We end up with (“red”, 2), (“blue”, 1).

Key point: one reducer handles all the values for a fixed key.

Got more data? Increase the number of map workers and reduce workers. In other words do it on more computers. MapReduce flattens the complexity of working with many computers. It’s elegant and people use it even when they “shouldn’t” (although, at Google it’s not so crazy to assume your data could grow by a factor of 100 overnight). Like all tools, it gets overused.

Counting was one easy function, but now it’s been split up into two functions. In general, converting an algorithm into a series of MapReduce steps is often unintuitive.

For the above word count, distribution needs to be uniform. It all your words are the same, they all go to one machine during the shuffle, which causes huge problems. Google has solved this using hash buckets heaps in the mappers in one MapReduce iteration. It’s called CountSketch, and it is built to handle odd datasets.

At Google there’s a realtime monitor for MapReduce jobs, a box with “shards” which correspond to pieces of work on a machine. It indicates through a bar chart how the various machines are doing. If all the mappers are running well, you’d see a straight line across. Usually, however, everything goes wrong in the reduce step due to non-uniformity of the data – lots of values on one key.

The data preparation and writing the output, which take place behind the scenes, take a long time, so it’s good to try to do everything in one iteration. Note we’re assuming distributed file system is already there – indeed we have to use MapReduce to get data to the distributed file system – once we start using MapReduce we can’t stop.

Once you get into the optimization process, you find yourself tuning MapReduce jobs to shave off nanoseconds 10^{-9} whilst processing petabytes of data. These are order shifts worthy of physicists. This optimization is almost all done in C++. It’s highly optimized code, and we try to scrape out every ounce of power we can.

Josh Wills

Our second speaker of the night was Josh Wills. Josh used to work at Google with Rachel, and now works at Cloudera as a Senior Director of Data Science. He’s known for the following quote:

Data Science (n.): Person who is better at statistics than any software engineer and better at software engineering than any statistician.

Thought experiment

How would you build a human-powered airplane? What would you do? How would you form a team?

Student: I’d run an X prize. Josh: this is exactly what they did, for $50,000 in 1950. It took 10 years for someone to win it. The story of the winner is useful because it illustrates that sometimes you are solving the wrong problem.

The first few teams spent years planning and then their planes crashed within seconds. The winning team changed the question to: how do you build an airplane you can put back together in 4 hours after a crash? After quickly iterating through multiple prototypes, they solved this problem in 6 months.

Josh had some observations about the job of a data scientist:

- I spend all my time doing data cleaning and preparation. 90% of the work is data engineering.

- On solving problems vs. finding insights: I don’t find insights, I solve problems.

- Start with problems, and make sure you have something to optimize against.

- Parallelize everything you do.

- It’s good to be smart, but being able to learn fast is even better.

- We run experiments quickly to learn quickly.

Data abundance vs. data scarcity

Most people think in terms of scarcity. They are trying to be conservative, so they throw stuff away.

I keep everything. I’m a fan of reproducible research, so I want to be able to rerun any phase of my analysis. I keep everything.

This is great for two reasons. First, when I make a mistake, I don’t have to restart everything. Second, when I get new sources of data, it’s easy to integrate in the point of the flow where it makes sense.

Designing models

Models always turn into crazy Rube Goldberg machines, a hodge-podge of different models. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, because if they work, they work. Even if you start with a simple model, you eventually add a hack to compensate for something. This happens over and over again, it’s the nature of designing the model.

Mind the gap

The thing you’re optimizing with your model isn’t the same as the thing you’re optimizing for your business.

Example: friend recommendations on Facebook doesn’t optimize you accepting friends, but rather maximizing the time you spend on Facebook. Look closely: the suggestions are surprisingly highly populated by attractive people of the opposite sex.

How does this apply in other contexts? In medicine, they study the effectiveness of a drug instead of the health of the patients. They typically focus on success of surgery rather than well-being of the patient.

When I graduated in 2001, we had two options for file storage.

1) Databases:

- structured schemas

- intensive processing done where data is stored

- somewhat reliable

- expensive at scale

2) Filers:

- no schemas

- no data processing capability

- reliable

- expensive at scale

Since then we’ve started generating lots more data, mostly from the web. It brings up the natural idea of a data economic indicator, return on byte. How much value can I extract from a byte of data? How much does it cost to store? If we take the ratio, we want it to be bigger than one or else we discard.

Of course this isn’t the whole story. There’s also a big data economic law, which states that no individual record is particularly valuable, but having every record is incredibly valuable. So for example in any of the following categories,

- web index

- recommendation systems

- sensor data

- market basket analysis

- online advertising

one has an enormous advantage if they have all the existing data.

A brief introduction to Hadoop

Back before Google had money, they had crappy hardware. They came up with idea of copying data to multiple servers. They did this physically at the time, but then they automated it. The formal automation of this process was the genesis of GFS.

There are two core components to Hadoop. First is the distributed file system (HDFS), which is based on the google file system. The data stored in large files, with block sizes of 64MB to 256MB. As above, the blocks are replicated to multiple nodes in the cluster. The master node notices if a node dies.

Data engineering on hadoop

Hadoop is written in java, Whereas Google stuff is in C++.

Writing map reduce in the java API not pleasant. Sometimes you have to write lots and lots of map reduces. However, if you use hadoop streaming, you can write in python, R, or other high-level languages. It’s easy and convenient for parallelized jobs.

Cloudera

Cloudera is like Red hat for hadoop. It’s done under aegis of the Apache Software Foundation. The code is available for free, but Cloudera packages it together, gives away various distributions for free, and waits for people to pay for support and to keep it up and running.

Apache hive is a data warehousing system on top of hadoop. It uses an SQL-based query language (includes some map reduce -specific extensions), and it implements common join and aggregation patterns. This is nice for people who know databases well and are familiar with stuff like this.

Workflow

- Using hive, build records that contain everything I know about an entity (say a person) (intensive mapReduce stuff)

- Write python scripts to process the records over and over again (faster and iterative, also mapReduce)

- Update the records when new data arrives

Note phase 2 are typically map-only jobs, which makes parallelization easy.

I prefer standard data formats: text is big and takes up space. Thrift, Avro, protobuf are more compact, binary formats. I also encourage you to use the code and metadata repository Github. I don’t keep large data files in git.

Rolling Jubilee is a better idea than the lottery

Yesterday there was a reporter from CBS Morning News looking around for a quirky fun statistician or mathematician to talk about the Powerball lottery, which is worth more than $500 million right now. I thought about doing it and accumulated some cute facts I might want to say on air:

- It costs $2 to play.

- If you took away the grand prize, a ticket is worth 36 cents in expectation (there are 9 ways to win with prizes ranging from $4 to $1 million).

- The chance of winning grand prize is one in about 175,000,000.

- So when the prize goes over $175 million, that’s worth $1 in expectation.

- So if the prize is twice that, at $350 million, that’s worth $2 in expectation.

- Right now the prize is $500 million, so the tickets are worth more than $2 in expectation.

- Even so, the chances of being hit by lightening in a given year is something like 1,000,000, so 175 times more likely than winning the lottery

In general, the expected payoff for playing the lottery is well below the price. And keep in mind that if you win, almost half goes to taxes. I am super busy trying to write, so I ended up helping find someone else for the interview: Jared Lander. I hope he has fun.

If you look a bit further into the lottery system, you’ll find some questionable information. For example, lotteries are super regressive: poor people spend more money than rich people on lotteries, and way more if you think of it as a percentage of their income.

One thing that didn’t occur to me yesterday but would have been nice to try, and came to me via my friend Aaron, is to suggest that instead of “investing” their $2 in a lottery, people might consider investing it in the Rolling Jubilee. Here are some reasons:

- The payoff is larger than the investment by construction. You never pay more than $1 for $1 of debt.

- It’s similar to the lottery in that people are anonymously chosen and their debts are removed.

- The taxes on the benefits are nonexistent, at least as we understand the taxcode, because it’s a gift.

It would be interesting to see how the mindset would change if people were spending money to anonymously remove debt from each other rather than to win a jackpot. Not as flashy, perhaps, but maybe more stimulative to the economy. Note: an estimated $50 billion was spent on lotteries in 2010. That’s a lot of debt.

How to evaluate a black box financial system

I’ve been blogging about evaluation methods for modeling, for example here and here, as part of the book I’m writing with Rachel Schutt based on her Columbia Data Science class this semester.

Evaluation methods are important abstractions that allow us to measure models based only on their output.

Using various metrics of success, we can contrast and compare two or more entirely different models. And it means we don’t care about their underlying structure – they could be based on neural nets, logistic regression, or decision trees, but for the sake of measuring the accuracy, or the ranking, or the calibration, the evaluation method just treats them like black boxes.

It recently occurred to me a that we could generalize this a bit, to systems rather than models. So if we wanted to evaluate the school system, or the political system, or the financial system, we could ignore the underlying details of how they are structured and just look at the output. To be reasonable we have to compare two systems that are both viable; it doesn’t make sense to talk about a current, flawed system relative to perfection, since of course every version of reality looks crappy compared to an ideal.

The devil is in the articulated evaluation metric, of course. So for the school system, we can ask various questions: Do our students know how to read? Do they finish high school? Do they know how to formulate an argument? Have they lost interest in learning? Are they civic-minded citizens? Do they compare well to other students on standardized tests? How expensive is the system?

For the financial system, we might ask things like: Does the average person feel like their money is safe? Does the system add to stability in the larger economy? Does the financial system mitigate risk to the larger economy? Does it put capital resources in the right places? Do fraudulent players inside the system get punished? Are the laws transparent and easy to follow?

The answers to those questions aren’t looking good at all: for example, take note of the recent Congressional report that blames Jon Corzine for MF Global’s collapse, pins him down on illegal and fraudulent activity, and then does absolutely nothing about it. To conserve space I will only use this example but there are hundreds more like this from the last few years.

Suffice it to say, what we currently have is a system where the agents committing fraud are actually glad to be caught because the resulting fines are on the one hand smaller than their profits (and paid by shareholders, not individual actors), and on the other hand are cemented as being so, and set as precedent.

But again, we need to compare it to another system, we can’t just say “hey there are flaws in this system,” because every system has flaws.

I’d like to compare it to a system like ours except where the laws are enforced.

That may sounds totally naive, and in a way it is, but then again we once did have laws, that were enforced, and the financial system was relatively tame and stable.

And although we can’t go back in a time machine to before Glass-Steagall was revoked and keep “financial innovation” from happening, we can ask our politicians to give regulators the power to simplify the system enough so that something like Glass-Steagall can once again work.

On Reuters talking about Occupy

I was interviewed a couple of weeks ago and it just got posted here:

Systematized racism in online advertising, part 1

There is no regulation of how internet ad models are built. That means that quants can use any information they want, usually historical, to decide what to expect in the future. That includes associating arrests with african-american sounding names.

In a recent Reuters article, this practice was highlighted:

Instantcheckmate.com, which labels itself the “Internet’s leading authority on background checks,” placed both ads. A statistical analysis of the company’s advertising has found it has disproportionately used ad copy including the word “arrested” for black-identifying names, even when a person has no arrest record.

Luckily, Professor Sweeney, a Harvard University professor of government with a doctorate in computer science, is on the case:

According to preliminary findings of Professor Sweeney’s research, searches of names assigned primarily to black babies, such as Tyrone, Darnell, Ebony and Latisha, generated “arrest” in the instantcheckmate.com ad copy between 75 percent and 96 percent of the time. Names assigned at birth primarily to whites, such as Geoffrey, Brett, Kristen and Anne, led to more neutral copy, with the word “arrest” appearing between zero and 9 percent of the time.

Of course when I say there’s no regulation, that’s an exaggeration. There is some, and if you claim to be giving a credit report, then regulations really do exist. But as for the above, here’s what regulators have to say:

“It’s disturbing,” Julie Brill, an FTC commissioner, said of Instant Checkmate’s advertising. “I don’t know if it’s illegal … It’s something that we’d need to study to see if any enforcement action is needed.”

Let’s be clear: this is just the beginning.

Aunt Pythia’s advice and a request for cool math books

First, my answer to last week’s question which you guys also answered:

Aunt Pythia,

My loving, wonderful, caring boyfriend slurps his food. Not just soup — everything (even cereal!). Should I just deal with it, or say something? I think if I comment on it he’ll be offended, but I find it distracting during our meals together.

Food (Consumption) Critic

——

You guys did well with answering the question, and I’d like to nominate the following for “most likely to actually make the problem go away”, from Richard:

I’d go with blunt but not particularly bothered – halfway through his next bowl of cereal, exclaim “Wow, you really slurp your food, don’t you?! I never noticed that before.”

But then again, who says we want this problem to go away? My firm belief is that every relationship needs to have an unimportant thing that bugs the participants. Sometimes it’s how high the toaster is set, sometimes it’s how the other person stacks the dishes in the dishwasher, but there’s always that thing. And it’s okay: if we didn’t have the thing we’d invent it. In fact having the thing prevents all sorts of other things from becoming incredible upsetting. My theory anyway.

So my advice to Food Consumption Critic is: don’t do anything! Cherish the slurping! Enjoy something this banal and inconsequential being your worst criticism of this lovely man.

Unless you’re like Liz, also a commenter from last week, who left her husband because of the way he breathed. If it’s driving you that nuts, you might want to go with Richard’s advice.

——

Aunt Pythia,

Dear Aunt Pythia, I want to write to an advice column, but I don’t know whether or not to trust the advice I will receive. What do you recommend?

Perplexed in SoPo

Dear PiSP,

I hear you, and you’re right to worry. Most people only ask things they kind of know the answer to, or to get validation that they’re not a total jerk, or to get permission to do something that’s kind of naughty. If the advice columnist tells them something they disagree with, they ignore it entirely anyway. It’s a total waste of time if you think about it.

However, if your question is super entertaining and kind of sexy, then I suggest you write in ASAP. That’s the very kind of question that columnists know how to answer in deep, meaningful and surprising ways.

Yours,

AP

——

Aunt Pythia,

With global warming and hot summers do you think it’s too early to bring the toga back in style?

John Doe

Dear John,

It’s never to early to wear sheets. Think about it: you get to wear the very same thing you sleep in. It’s like you’re a walking bed.

Auntie

——

Aunt Pythia,

Is it unethical not to tell my dad I’m starting a business? I doubt he’d approve and I’m inclined to wait until it’s successful to tell him about it.

Angsty New Yorker

Dear ANY,

Wait, what kind of business is this? Are we talking hedge fund or sex toy shop?

In either case, I don’t think you need to tell your parents anything about your life if you are older than 18 and don’t want to, it’s a rule of american families. Judging by my kids, this rule actually starts when they’re 11.

Of course it depends on your relationship with your father how easy that will be and what you’d miss out on by being honest, but the fear of his disapproval is, to me, a bad sign: you’re gonna have to be tough as nails to be a business owner, so get started by telling, not asking, your dad. Be prepared for him to object, and if he does, tell him he’ll get used to it with time.

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

I’m a philosophy grad school dropout turned programmer who hasn’t done math since high school. But I want to learn, partly for professional reasons but mainly out of curiosity. I recently bought *Proofs From the Book* but found that I lacked the requisite mathematical maturity to work through much of it. Where should I start? What should I read? (p.s. Thanks for the entertaining blog!)

Confused in Brooklyn

Readers, this question is for you! I don’t know of too many good basic math books, so Confused in Brooklyn is counting on you. There have actually been lots of people asking similar questions, so you’d be helping them too. If I get enough good suggestions I’ll create a separate reading list for cool math page on mathbabe. Thanks in advance for your suggestions!

——

Please take a moment to ask me a question:

It’s Pro-American to be Anti-Christmas

This is a guest post by Becky Jaffe.

I know what you’re thinking: Don’t Christmas and America go together like Santa and smoking?

Why, of course they do! Just ask Saint Nickotine, patron saint of profit. This Lucky Strike advertisement is an early introduction to Santa the corporate shill, the seasonal cash cow whose avuncular mug endorses everything from Coca-Cola to Siri to yes, even competing brands of cigarettes like Pall Mall. Sorry Lucky Strike, Santa’s a bit of a sellout.

Nearly a century after these advertisements were published, the secular trinity of Santa, consumerism and America has all but supplanted the holy trinity the holiday was purportedly created to commemorate. I’ll let Santa the Spokesmodel be the cheerful bearer of bad news:

Christmas and consumerism have been boxed up, gift-wrapped and tied with a red-white-and-blue ribbon. In this guest post I’ll unwrap this package and explain why I, for one, am not buying it.

____________________

Yesterday was Thanksgiving, followed inexorably by Black Friday; one day we’re collectively meditating on gratitude, the next we’re jockeying for position in line to buy a wall-mounted 51” plasma HDTV. Some would argue that’s quintessentially American. As social critic and artist Andy Warhol wryly observed, “Shopping is more American than thinking.”

Such a dour view may accurately describe post WW II America, but not the larger trends nor longer traditions of our nation’s history. Although we may have become profligate of late, we were at the outset a frugal people; consumerism and America need not be inextricably linked in our collective imagination if we take a longer view. Long before there was George Bush telling us the road to recovery was to have faith in the American economy, there was Henry David Thoreau, who spoke to a faith in a simpler economy:

The Simple Living experiment he undertook and chronicled in his classic Walden was guided by values shared in common by many of the communities who sought refuge in the American colonies at the outset of our nation: the Mennonites, the Quakers, and the Shakers. These groups comprise not only a great name for a punk band, but also our country’s temperamental and ethical ancestry. The contemporary relationship between consumerism and Christmas is decidedly un-American, according to our nation’s founders. And what could be more American than the Amish? Or the secular version thereof: The Simplicity Collective.

Being anti-Christmas™ is as uniquely American as Thoreau, who summed up his anti-consumer credo succinctly: “Men have become the tools of their tools.” If he were alive today, I have no doubt that curmudgeonly minimalist would be marching with Occupy Wall Street instead of queuing with the tools on Occupy Mall Street.

Being anti-Christmas™ is as American as Mark Twain, who wrote, “The approach of Christmas brings harrassment and dread to many excellent people. They have to buy a cart-load of presents, and they never know what to buy to hit the various tastes; they put in three weeks of hard and anxious work, and when Christmas morning comes they are so dissatisfied with the result, and so disappointed that they want to sit down and cry. Then they give thanks that Christmas comes but once a year.” (From Following the Equator)

Being anti-Christmas™ is as American as “Oklahoma’s favorite son,” Will Rogers, 1920’s social commentator who made the acerbic observation, “Too many people spend money they haven’t earned, to buy things they don’t want, to impress people they don’t like.”

He may have been referring to presents like this, which are just, well, goyish:

Being anti-Christmas is as American as Robert Frost, recipient of four Pulitzer prizes in poetry, who had this to say in a Christmas Circular Letter:

He asked if I would sell my Christmas trees;

My woods—the young fir balsams like a place

Where houses all are churches and have spires.

I hadn’t thought of them as Christmas Trees.

I doubt if I was tempted for a moment

To sell them off their feet to go in cars

And leave the slope behind the house all bare,

Where the sun shines now no warmer than the moon.

I’d hate to have them know it if I was.

Yet more I’d hate to hold my trees except

As others hold theirs or refuse for them,

Beyond the time of profitable growth,

The trial by market everything must come to.

We inherit from these American thinkers a unique intellectual legacy that might make us pause at the commercialism that has come to consume us. To put it in other words:

- John Porcellino’s Thoreau at Walden: $18

- Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: $5.95

- Mary Oliver’s American Primitive: $9.99

- The Life and Letters of John Muir: $12.99

- Transcendentalist Intellectual Legacy: Priceless.

The intellectual and spiritual founders of our country caution us to value our long-term natural resources over short-term consumptive titillation. Unheeding their wisdom, last year on Black Friday American consumers spent $11.4 billion, more than the annual Gross Domestic Product of 73 nations.

And American intellectual legacy aside, isn’t that a good thing? Doesn’t Christmas spending stimulate our stagnant economy and speed our recovery from the recession? If you believe organizations like Made in America, it’s our patriotic duty to spend money over the holidays. The exhortation from their website reads, “If each of us spent just $64 on American made goods during our holiday shopping, the result would be 200,000 new jobs. Now we want to know, are you in?”

That depends once again on whether or not we take the long view. Christmas spending might create a few temporary, low-wage, part-time jobs without benefits of the kind described in Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By In America, but it’s not likely to create lasting economic health, especially if we fail to consider the long-term environmental and social costs of our short-term consumer spending sprees. The answer to Made in America’s question depends on the validity of the economic model we use to assess their spurious claim, as Mathbabe has argued time and again in this blog. The logic of infinite growth as an unequivocal net good is the same logic that underlies such flawed economic models as the Gross National Product (GNP) and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

These myopic measures fail to take into account the value of the natural resources from which our consumer products are manufactured. In this accounting system, when an old-growth forest is clearcut to make way for a Best Buy parking lot, that’s counted as an unequivocal economic boon since the economic value of the lost trees/habitat is not considered as a debit. Feminist economist and former New Zealand parliamentarian Marilyn Waring explains the idea accessibly in this documentary: Who’s Counting? Marilyn Waring on Sex, Lies, and Global Economics.

If we were to adopt a model that factors in the lost value of nonrenewable natural resources, such as the proposed Green National Product, we might skip the stampede at Walmart and go for a walk in the woods instead to stimulate the economy.

Other critics of these standard models for measuring economic health point out that they overvalue quantity of production and, by failing to take into account such basic measures of economic health as wealth distribution, undervalue quality of life. And the growing gap in income inequality is a trend that we cannot afford to overlook as we consider the best options for economic recovery. According to this New York Times article, “Income inequality has soared to the highest levels since the Great Depression, and the recession has done little to reverse the trend, with the top 1 percent of earners taking 93 percent of the income gains in the first full year of the recovery.”

For the majority of Americans who are still struggling to make ends meet, the Black Friday imperative to BUY! means racking up more credit card debt. (As American poet ee cummings quipped,” “I’m living so far beyond my income that we may almost be said to be living apart.”) The specter of Christmas spending is particularly ominous this season, during a recession, after a national wave of foreclosures has left Americans with insecure housing, exorbitant rents, and our beleaguered Santa with fewer chimneys to squeeze into.

Some proposed alternatives to the GDP and GNP that factor in income distribution are the Human Progress Index, the Genuine Progress Indicator, and yes, even a proposed Gross National Happiness.

A dose of happiness could be just the antidote to the dread many Americans feel at the prospect of another hectic holiday season. As economist Paul Heyne put it, “The gap in our economy is between what we have and what we think we ought to have – and that is a moral problem, not an economic one.”

____________________

Mind you, I’m not anti-Christmas, just anti-Christmas™. I’ve been referring thus far to the secular rites of the latter, but practicing Christians for whom the former is a meaningful spiritual meditation might equally take offense at its runaway commercialization, which the historical Jesus would decidedly not have endorsed.

I hate to pull the Bible card, but, seriously, what part of Ecclesiastes don’t you understand?

Photo by Becky Jaffe. http://www.beckyjaffe.com

Better is an handful with quietness, than both the hands full with travail and vexation of spirit. – Ecclesiastes 4:6

Just imagine if Buddhism were hijacked by greed in the same fashion.

After all,

Right?

Or is it axial tilt?

Whether you’re a practicing Christian, a Born-Again Pagan celebrating the Winter Solstice (“Mithras is the Reason for the Season”), or a fundamentalist atheist (“You know it’s a myth! This season, celebrate reason.”), we all have reason to be concerned about the corporatization of our cultural rituals.

The meaning of Christmas has gotten lost in translation:

So this year, let’s give Santa a much-needed smoke break, pour him a glass of Kwanzaa Juice, and consider these alternatives for a change:

1. Presence, not presents. Skip the spending binge (and maybe even another questionable Christmas tradition, the drinking binge), and give the gift of time to the people you love. I’m talking luxurious swaths of time: unstructured time, unproductive time, time wasted exquisitely together.

I’m talking about turning off the television in preparation for Screen-Free Week 2013, and going for a slow walk in nature, which can create more positive family connection than the harried shopping trip. And if Richard Louv’s thesis about Nature Deficit Disorder is merited, it may be healthier for your child to take a walk in the woods than to camp out in front of the X-Box you can’t afford anyway.

Whether you’re choosing to spend the holidays with your family of origin or your family of choice, playing a game together is a great way to reconnect. How about kibitzing over this new card game 52 Shades of Greed? It’s quite the conversation starter. And what better soundtrack for a card game than Sweet Honey in the Rock’s musical musings on Greed? Or Tracy Chapman’s Mountains of Things.

Or how about seeing a show together? You can take the whole family to see Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping at the Highline Ballroom in New York this Sunday, November 25th. He’s on a “mission to save Christmas from the Shopocalypse.” From the makers of the film What Would Jesus Buy?

2. Give a group gift. There is a lot of talk about family values, but how well do we know each other’s values? One way to find out is to pool our giving together and decide as a group who the beneficiaries should be. You might elect to skip Black Friday and Cyber Monday and make a donation instead to Giving Tuesday’s Hurricane Sandy relief efforts. Other organizations worth considering:

3. Think outside the box. If you’re looking for alternatives to the gift-giving economy, how about bartering? Freecycle is a grassroots organization that puts a tourniquet on the flow of luxury goods destined for the landfill by creating local voluntary swap networks.

Or how about giving the gift of debt relief? Check out the Rolling Jubilee, a “bailout for the people by the people.”

4. Give the Buddhist gift: Nothing!

Buy Nothing Do Something is the slogan of an organization proposing an alternative to Black Friday: On Brave Friday, we “choose family over frenzy.” One contributor to the project shared this family tradition: “We have a “Five Hands” gift giving policy. We can exchange items that are HANDmade (by us), HAND-me-down and secondHAND. We can choose to gift a helping HAND (donations to charities). Lastly and my favorite, we can gift a HAND-in-hand, which is a dedication of time spent with one another. (Think date night or a day at the museum as a family.)”

Adbusters magazine sponsors an annual boycott of consumerism in England called Buy Nothing Day.

5. Invent your own holiday. Americans pride ourselves on our penchant for innovation. We amalgamate and synthesize novelty out of eclectic sources. Although we often talk about “traditional values,” we’re on the whole much less tradition-bound than say, the Serbs, who collectively recall several thousand years of history as relevant to the modern instant. We tend to abandon tradition when it is incovenient (e.g. marriage), which is perhaps why we harken back to its fantasy status in such a treacly manner. Making stuff up is what we do well as a nation. Isn’t “DIY Christmas” a no-brainer? Happy Christmahannukwanzaka, y’all!

6. Keep it weird. Several of you wrote with these suggestions for Black Friday street theater:

“Someone said go for a hike in a park, not the Wal*Mart parking lot. But why not the Wal*Mart parking lot? With all your hiking gear and everything.”

“I’d love for 5-6 of us to sit at Union Square in front of Macy’s and sit and meditate. Perhaps passer-bys will take a notice and ponder. Anyone in? Friday 2-3 hours.”

Few pranksters have been so elaborate in their anti-corporate antics as the Yes Men. You may get inspired to come up with some political theater of your own after watching the documentary The Yes Men: The True Story of the End of the World Trade Organization.

____________________

However we choose to celebrate the holidays in this relativist pluralistic era, whatever our preferred religious and/or cultural December-based holiday celebration may be, we can disentangle our rituals from obligatory consumerism.

I’m not suggesting this is an easy task. Our consumer habits are wrapped up with our identities as social critic Alain de Botton observes: “We need objects to remind us of the commitments we’ve made. That carpet from Morocco reminds us of the impulsive, freedom-loving side of ourselves we’re in danger of losing touch with. Beautiful furniture gives us something to live up to. All designed objects are propaganda for a way of life.”

This year, let’s skip the propaganda.

We can choose to

Yes, we can.

Happy Solstice, everyone!

(If only I had a Celestron CPC 1100 Telescope with Nikon D700 DSLR adapter to admire the Solstice skies….)

A primer on time wasting

Hello, Aaron here.

Cathy asked me to write a post about wasting time. But I never got around to it.

Just kidding. I’m actually doing it.

Things move fast here in New York City, but where the hell is everyone going anyway?

When I was writing my dissertation, I lived on the west coast and Cathy lived on the east coast. I used to get up around 7 every morning. She was very pregnant (for the first time), and I was very stressed out. We talked on the phone every morning, and we got in the habit of doing the New York Times crossword puzzle. Mind you, this was before it was online – she actually had a newspaper, with ink and everything, and she read me the clues over the phone and we did the puzzle together. It helped get me going in the morning, and it warmed me up for dissertation writing.

After a long time of not doing crossword puzzles, I’ve taken it up again in recent years. Sometimes Cathy and I do it together, online, using the app where two people can solve it at the same time. [NYT, if you’re listening, the new version is much worse than the old! Gotta fix up the interfacing.] Sometimes I do it myself. Sometimes, like today, it’s Thanksgiving, and it’s a real treat to do the puzzle with Cathy in person. But one way or another, I do it just about every day.

At one point, early in the current phase of my habit, I got stuck and I wanted to cheat. I looked for the answers online, since I couldn’t just wait until the next day. I came across this blog, which I call rexword for short.

I got addicted. As happens so frequently with the internets, I discovered an entire community of people who are both really into something mildly obscure (read: nerdy) and also actually insightful, funny, and interesting (read: nerdy).

I’ve learned a lot about puzzling from rexword. I like to tell my students they have to learn how to get “behind” what I write on the chalkboard, to see it before it’s being written or as it’s being written as if they were doing it themselves, the way a musician hears music or the way anyone does anything at an expert level. Rex’s blog took me behind the crossword puzzle for the first time. I’m nowhere near as good at it as he is, or as many of his readers seem to be, but seeing it from the other side is a lot of fun. I appreciate puzzles in a completely different way now: I no longer just try to complete it (which is still a challenge a lot of the time, e.g. most Saturdays), but I look it over and imagine how it might have been different or better or whatever. Then, especially if I think there’s something especially notable about it, I go to the blog expecting some amusing discussion.

Usually I find it. In fact, usually I find amusing discussion and insights about way more things than I would ever notice myself about the puzzle. I also find hilarious things like this:

We just did last Sunday’s puzzle, and at the end we noticed that the completed puzzle contained all of the following: g-spot, tits, ass, cock. Once upon a time I might not have thought much of this (or noticed) but now my reaction was, “I bet there’s something funny about this on the blog.” I was sure this would be amply noted and wittily de- and re-constructed. In fact, it barely got a mention, although predictably, several commenters picked up the slack.

Anyway, I’ve got this particular addiction under control – I no longer read the blog every day, but as I said, when there’s something notable or funny I usually check it out and sometimes comment myself, if no one else seems to have noticed whatever I found.

What is the point of all this? In case you forgot, Cathy asked me to write about wasting time. I think she made this request because of the relish with which I tread the fine line between being super nerdy about something and just wasting time (don’t get me started about the BCS….).

Today, I am especially thankful to be alive and in such a luxurious condition that I can waste time doing crossword puzzles, and then reading blogs about doing crossword puzzles, and then writing blogs about reading blogs about doing crossword puzzles.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone.

Black Friday resistance plan

The hype around Black Friday is building. It’s reaching its annual fever pitch. Let’s compare it to something much less important to americans like “global warming”, shall we? Here we go:

Note how, as time passes, we become more interested in Black Friday and less interested in global warming.

How do you resist, if not the day itself, the next few weeks of crazy consumerism that is relentlessly plied? Lots of great ideas were posted here, when I first wrote about this. There will be more coming soon.

In the meantime, here’s one suggestion I have, which I use all the time to avoid over-buying stuff and which this Jane Brody article on hoarding reminded me of.

Mathbabe’s Black Friday Resistance plan, step 1:

Go through your closets and just look at all the stuff you already have. Go through your kids’ closets and shelves and books and toychests to catalog their possessions. Count how many appliances you own, in your kitchen alone.

Be amazed that anyone could ever own that much stuff, and think about what we really need to survive, and indeed, what we really need to be content.

In case you need more, here’s an optional step 2. Think about the Little House on the Prairie series, and how Laura made a doll out of scraps of cloth left over from the dresses, and how once a year when Pa sold his crop they’d have penny candy and it would be a huge treat. For Christmas one year, Laura got an orange. Compared to that we binge on consumerism on a daily basis and we’ve become enured to its effects.

Now, I’m not a huge fan of going back to those roots entirely. After all, during The Long Winter, as I’m sure you recall and which was very closely based on her real experience, Mary went blind from hunger and Carrie was permanently affected. If it hadn’t been for Almonzo coming to their rescue with food for the whole town, many might have died. Now that was a man.