Leila Schneps is a mystery writer!

I’m back! I missed you guys bad.

My experience with Seattle in the last 8 days has convinced me of something I rather suspected, namely I’m a huge New York snob and can’t exist happily anywhere else. I will spare you the details (they have to do with cars, subways, and being an asshole pedestrian) but suffice it to say, glad to be home.

Just a few caveats on complaining about my vacation:

- I enjoyed visiting the University of Washington and giving the math colloquium there as well as a “Math Day” talk where I showed kids the winning strategy for Nim (as well as other impartial two-player games) following my notes from last summer.

- I enjoyed reading Leon and Becky’s guest posts. Thanks guys!

- And then there was the time spent with my darling family. Of course, goes without saying, it’s always magical to get to the point where your kids have invented a whole new language of insults after you’ve outlawed certain words: “Shut your fidoodle, you syncopathic lardle!”

Of all the topics I want to write about today, I’ve decided to go with the most immediate and surprising one : Leila Schneps is now a mystery writer! How cool is that? She’s written a book with her daughter, Math on Trial: How Numbers Get Used and Abused in the Courtroom, currently in stock and available on Amazon. And she wrote an op-ed for the New York Times talking about it (hat tip Chris Wiggins).

I know Leila from having been her grad student assistant at the GWU Summer Program for Women in Math the first year it existed, in 1995. She taught undergrads about Galois cohomology and interpreted elements of as twists and elements of

as obstructions and then had them do a bunch of examples for homework with me. It was pretty awesome, and I learned a ton. Leila is also a regular and fantastic commenter on mathbabe.

I love the premise of the book she’s written. She finds a bunch of historical examples where mathematics is used in trials to the detriment of justice, and people get unfairly jailed (or, less often, let free). From the op-ed (emphasis mine):

Decades ago, the Harvard law professor Laurence H. Tribe wrote a stinging denunciation of the use of mathematics at trial, saying that the “overbearing impressiveness” of numbers tends to “dwarf” other evidence. But we neither can nor should throw math out of the courtroom. Advances in forensics, which rely on data analysis for everything from gunpowder to DNA, mean that quantitative methods will play an ever more important role in judicial deliberations.

The challenge is to make sure that the math behind the legal reasoning is fundamentally sound. Good math can help reveal the truth. But in inexperienced hands, math can become a weapon that impedes justice and destroys innocent lives.

Go Leila!

Nerd Nite: A Drunken Venue for Ideas

MathBabe recently wrote an article critical of the elitist nature of Ted Talks, which you can read here. Fortunately for her, and for the hoi polloi everywhere clamoring for populist science edutainment, there is an alternative: Nerd Nite. Once a month, in cities all over the globe, nerds herd into a local bar and turn it into a low-brow forum for innovative science ideas. Think Ted Talks on tequila.

Each month, three speakers present talks for 20-30 minutes, followed by questions and answers from the invariably sold-out audience. The monthly forum gives professional and amateur scientists an opportunity to explain their fairly abstruse specialties accessibly to a lay audience – a valuable skill. Since the emphasis is on science entertainment, it also gives the speakers a chance to present their ideas in a more engaging way: in iambic pentameter, in drag with a tuba, in three-part harmony, or via interpretive dance – an invaluable skill. The resulting atmosphere is informal, delightfully debauched, and refreshingly pro-science.

Slaking our thirst for both science education and mojitos, Nerd Nite started small but quickly went viral. Nerd Nites are now being held in 50 cities, from San Francisco to Kansas City and Auckland to Liberia. You can find the full listing of cities here; if you don’t see one near you, start one!

Last Wednesday night I was twitterpated to be one of three guest nerds sharing the stage at San Francisco’s Nerd Nite. I put the chic back into geek with a biology talk entitled “Genital Plugs, Projectile Penises, and Gay Butterflies: A Naturalist Explains the Birds and the Bees.”

A video recording of the presentation will be available online soon, but in the meantime, here’s a tantalizing clip from the talk, in which Isabella Rossellini explains the mating habits of the bee. Warning: this is scientifically sexy.

I shared the stage with Chris Anderson, who gave a fascinating talk on how the DIY community is building drones out of legos and open-source software. These DIY drones fly below government regulation and can be used for non-military applications, something we hear far too little of in the daily war digest that passes for news. The other speaker was Mark Rosin of the UK-based Guerrilla Science project. This clever organization reaches out to audiences at non-science venues, such as music concerts, and conducts entertaining presentations that teach core science ideas. As part of his presentation Mark used 250 inflated balloons and a bass amp to demonstrate the physics concept of resonance.

If your curiosity has been piqued and you’d like to check out an upcoming Nerd Nite, consider attending the upcoming Nerdtacular, the first Nerd Nite Global Festival, to be held this August 16-18th in Brooklyn, New York.

The global Nerdtacular: Now that’s an idea worth spreading.

Hackprinceton

He-Yo

This Friday, I’ll be participating at HackPrinceton.

My team will be training an EEG to recognize yes and no thoughts for particular electromechanical devices and creating general human brain interface (HBI) architecture.

We’ll be working on allowing you to turn on your phone and navigate various menus with your mind!

There’s lots of cool swag and prizes – the best being jobs at Google and Microsoft. Everyone on the team has experience in the field,* but of course the more the merrier and you’re welcome no matter what you bring (or don’t bring!) to the table.

If you’re interested, email leon.kautsky@gmail.com ASAP!

*So far we’ve got a math Ph.D., a mech engineer, some CS/Operations Research guys and while my field is finance I picked up some neuro/machine learning along the way. If you have nothing to do for the next three days and want to learn something specifically for this competition, I recommend checking out my personal favorites: neurofocus.com, frontiernerds.com or neurogadget.com.

Intermezzo II

One of the saddest moments in my life is when they closed the Penn Station Borders book store to replace it with a store dedicated to the “new teen band” One Direction.

Aunt Orthoptera: Advice from an Arthropod

Greetings from Aunt Orthoptera!

(Photo by Becky Jaffe)

This week I am guest blogging for Aunt Pythia, answering all of your queries from the perspective of a variety of insect species, naturally.

——

Dear Aunt Orthoptera,

My friend just started an advice column. She says she only wants “real” questions. But the membrane between truth and falsity is, as we all know, much more porous and permeable than this reductive boolean schema. What should I do?

Sincerely,

Mergatroid

P.S. I have a friend who always shows up to dinner parties empty-handed. What should I do?

Dear Mergatroid,

As I grant your point entirely, I will address only your postscript. What should you do with a friend who shows up to dinner parties empty-handed? Fill her hands with food. As an ant, I have two stomachs: a “social stomach,” and a private stomach. When I pass one of my sisters on our path, we touch each other’s antennae and communicate our needs via pheromones. If she is hungry, we kiss, a process unimaginatively called “trophallaxis” by your scientists. I feed her from my social stomach, and I trust she will do the same for me later – or if not her, exactly, another sister in whom the twin hungers for self-interest and interdependence coexist.

Anatomy as metaphor,

Aunt Orthoptera aka Ms. Myrmecology

(Photo by Becky Jaffe)

——

Dear Aunt Orthoptera,

I am struggling with emotional loneliness. Do you think it is possible to be happy – or even just productive – in life without a stable romantic relationship? If so, how? I have a couple close friends I can talk with, but they are in their own relationships and they are often too busy to have time to talk. I am in my early thirties and never had a girlfriend despite trying for nearly a decade. I have tried speed-dating, been on eharmony, match, ok cupid, asked friends to set me up, asked out a classmate in grad school, joined meetup groups. I am a nice guy but I have my flaws (nothing horrible) – I am kind of introverted, somewhat boring, and am consumed with my career (I’m untenured). It is so hard to meet people that I am compatible with – especially since I am a shy guy (perhaps it’s not surprising I am a math professor – I LOVE my job, by the way). I found ok cupid to be useful for identifying possibly compatible women but most women don’t respond to my messages. I was lucky to manage to get to go on first (and last) dates with two women I messaged on ok cupid last year, and was interested in going on more dates with both, but both of them declined, even though they both told me I seemed like a good person – “you seem like one of the nicest guys I met” is a direct quote, but that they didn’t feel there was any “chemistry”. This month I have been heartbroken over one of them. All this has been affecting my productivity.

Sincerely,

Singleton

Dear Singleton,

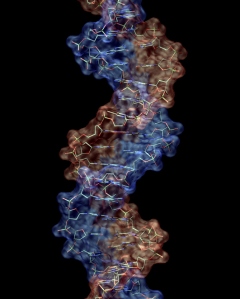

In my anthropological studies of humans, I have observed that you are yearning creatures. Your inexorable primateness destines you to a life of longing for social contact. As a solitary insect, I both pity and admire this craving for connection with your kind. My advice to you is to have compassion for your fundamental humanness. Your yearning for pair bonding is normal; it’s in your nature to want to entangle yourself with another. As creatures born of DNA, pair bonding operates at both the molecular level (e.g. Cytosine pair-bonds with Guanine) and the organismal level (woman to man, man to man, woman to woman).

(Photo: Double Helix by Becky Jaffe)

I suspect there’s another lonely strand of DNA out there for you, worth waiting for.

(Photo by Becky Jaffe)

I hope you find your mate!

Flirting with Sociobiology,

Aunt Orthoptera

——

Dear Aunt Orthoptera,

Do you have any self-soothing advice for when self-doubt, lack of confidence, and depression begin to take over?

Sincerely,

Feeling Very Small

Dear FVS,

As a tiny butterfly, I can assure you that it is ok to feel small. Here is my advice to you when you feel this way: Don’t just stop and smell the flowers, nuzzle in them.

(Photo by Becky Jaffe)

Let your worries float away for a little while and drift toward the sweetest thing you can find. When viewed through a compound lens, the whole world can look like nectar.

Spring springs eternal,

Aunt Orthoptera aka Lady Lepidoptera

——

Dear Aunt Orthoptera,

How will you enquire into that which you do not know?

Meno

Excellent question, Musing Meno.

The answer is: with great patience, dear Grasshopper.

(Photo by Becky Jaffe)

Next week, the inimitable Aunt Pythia will return with human advice for you. You can use the form below to submit questions.

Wishing you harmony in your hive and honey to thrive,

Aunt Orthoptera

Guest Post SuperReview: Intermezzo

I highly recommend That Mitchell and Webb Look.

Guest Post SuperReview Part III of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I and a little Part II: Where We Are Now

Whattup.

Moving on from Lewis’ cute Bloomberg column reprint, we come to the next essay in the series:

The Widening Gyre: Inequality, Polarization, and the Crisis by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells

Indefatigable pair Paul Krugman and Robin Wells (KW hereafter) contribute one of the several original essays in the book, but the content ought to be familiar if you read the New York Times, know something about economics or practice finance. Paul Krugman is prolific, and it isn’t hard to be prolific when you have to rewrite essentially the same column every week; question, are there other columnists who have been so consistently right yet have failed to propose anything that the polity would adopt? Political failure notwithstanding, Krugman leaves gems in every paragraph for the reader new to all this. The title “The Widening Gyre” comes from an apocalyptic William Yeats Butler poem. In this case, Krugman and Wells tackle the problem of why the government responded so poorly to the crisis. In their words:

By 2007, America was about as unequal as it had been on the eve of the Great Depression – and sure enough, just after hitting this milestone, we lunged into the worst slump since the Depression. This probably wasn’t a coincidence, although economists are still working on trying to understand the linkages between inequality and vulnerability to economic crisis.

Here, however, we want to focus on a different question: why has the response to crisis been so inadequate? Before financial crisis struck, we think it’s fair to say that most economists imagined that even if such a crisis were to happen, there would be a quick and effective policy response [editor’s note: see Kautsky et al 2016 for a partial explanation]. In 2003 Robert Lucas, the Nobel laureate and then president of the American Economic Association, urged the profession to turn its attention away from recessions to issues of longer-term growth. Why? Because he declared, the “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Famous last words from Professor Lucas. Nevertheless, the curious failure to apply what was once the conventional wisdom on a useful scale intrigues me for two reasons. First, most political scientists suggest that democracy, versus authoritarian system X, leads to better outcomes for two reasons.

1. Distributional – you get a nicer distribution of wealth (possibly more productivity for complicated macro reasons); economics suggests that since people are mostly envious and poor people have rapidly increasing utility in wealth, democracy’s tendency to share the wealth better maximizes some stupid social welfare criterion (typically, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency).

2. Information – democracy is a better information aggregation system than dictatorship and an expanded polity makes better decisions beyond allocation of produced resources. The polity must be capable of learning and intelligent OR vote randomly if uninformed for this to work. While this is the original rigorous justification for democracy (first formalized in the 1800s by French rationalists), almost no one who studies these issues today believes one-person one-vote democracy better aggregates information than all other systems at a national level. “Well Leon,” some knave comments, “we don’t live in a democracy, we live in a Republic with a president…so shouldn’t a small group of representatives better be able to make social-welfare maximizing decisions?” Short answer: strong no, and US Constitutionalism has some particularly nasty features when it comes to political decision-making.

Second, KW suggest that the presence of extreme wealth inequalities act like a democracy disabling virus at the national level. According to KW extreme wealth inequalities perpetuate themselves in a way that undermines both “nice” features of a democracy when it comes to making regulatory and budget decisions.* Thus, to get better economic decision-making from our elected officials, a good intermediate step would be to make our tax system more progressive or expand Medicare or Social Security or…Well, we have a lot of good options here. Of course, for mathematically minded thinkers, this begs the following question: if we could enact so-called progressive economic policies to cure our political crisis, why haven’t we done so already? What can/must change for us to do so in the future? While I believe that the answer to this question is provided by another essay in the book, let’s take a closer look at KW’s explanation at how wealth inequality throws sand into the gears of our polity. They propose four and the following number scheme is mine:

1. The most likely explanation of the relationship between inequality and polarization is that the increased income and wealth of a small minority has, in effect bought the allegiance of a major political party…Needless to say, this is not an environment conducive to political action.

2. It seems likely that this persistence [of financial deregulation] despite repeated disasters had a lot do with rising inequality, with the causation running in both directions. On the one side the explosive growth of the financial sector was a major source of soaring incomes at the very top of the income distribution. On the other side, the fact that the very rich were the prime beneficiaries of deregulation meant that as this group gained power- simply because of its rising wealth- the push for deregulation intensified. These impacts of inequality on ideology did not in 2008…[they] left us incapacitated in the face of crisis.

3. Conservatives have always seen seen [Keynesian economics] as the thin edge of the wedge: concede that the government can play a useful role in fighting slumps, and the next thing you know we’ll be living under socialism.

4. [Krugman paraphrasing Kalecki] Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment to a great extend on the so-called state of confidence….This gives capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.

All of these are true to an extent. Two are related to the features of a particular policy position that conservatives don’t like (countercyclical spending) and their cost will dissipate if the economy improves. Isn’t it the case that most proponents and beneficiaries of financial liberalization are Democrats? (Wall Street mostly supported Obama in 08 and barely supported Romney in 12 despite Romney giving the house away). In any case, while KW aren’t big on solutions they certainly have a strong grasp of the problem.

Take a Stand: Sit In by Phillip Dray

As the railroad strike of 1877 had led eventually to expanded workers’ rights, so the Greensboro sit-in of February 1, 1960, helped pave the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both movements remind us that not all successful protests are explicit in their message and purpose; they rely instead on the participants’ intuitive sense of justice. [28]

I’m not the only author to have taken note of this passage as particularly important, but I am the only author who found the passage significant and did not start ranting about so-called “natural law.” Chronicling the (hitherto unknown-to-me) history of the Great Upheaval, Dray does a great job relating some important moments in left protest history to the OWS history. This is actually an extremely important essay and I haven’t given it the time it deserves. If you read three essays in this book, include this in your list.

Inequality and Intemperate Policy by Raghuram Rajan (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

Rajan’s basic ideas are the following: inequality has gotten out of control:

Deepening income inequality has been brought to the forefront of discussion in the United States. The discussion tends to center on the Croesus-like income of John Paulson, the hedge fund manager who made a killing in 2008 betting on a financial collapse and netted over $3 billion, about seventy-five-thousand times the average household income. Yet a more worrying, everyday phenomenon that confronts most Americans is the disparity in income growth rates between a manager at the local supermarket and the factory worker or office assistant. Since the 1970s, the wages of the former, typically workers at the ninetieth percentile of the wage distribution in the United States, have grown much faster than the wages of the latter, the typical median worker.

But American political ideologies typically rule out the most direct responses to inequality (i.e. redistribution). The result is a series of stop-gap measures that do long-run damage to the economy (as defined by sustainable and rising income levels and full employment), but temporarily boost the consumption level of lower classes:

It is not surprising then, that a policy response to rising inequality in the United States in the 1990s and 200s – whether carefully planned or chosen as the path of least resistance – was to encourage lending to households, especially but not exclusively low-income ones, with the government push given to housing credit just the most egregious example. The benefit – higher consumption – was immediate, whereas paying the inevitable bill could be postponed into the future. Indeed, consumption inequality did not grow nearly as much as income inequality before the crisis. The difference was bridged by debt. Cynical as it may seem, easy credit has been used as a palliative success administrations that been unable to address the deeper anxieties of the middle class directly. As I argue in my book Fault Lines, “Let them eat credit” could well summarize the mantra of the political establishment in the go-go years before the crisis.

Why should you believe Raghuram Rajan? Because he’s one of the few guys who called the first crisis and tried to warn the Fed.

A solid essay providing a more direct link between income inequality and bad policy than KW do.

The 5 Percent by Michael Hiltzik

The 5 percent’s [consisting of the seven million Americans who, in 1934, were sixty-five and older] protests coalesced as the Townsend movement, launched by a sinewy midwestern farmer’s son and farm laborer turned California physician. Francis Townsend was a World War I veteran who had served in the Army Medical Corps. He had an ambitious, and impractical plan for a federal pension program. Although during its heyday in the 1930s the movement failed to win enactment of its [editor’s note: insane] program, it did play a critical role in contemporary politics. Before Townsend, America understood the destitution of its older generations only in abstract terms; Townsend’s movement made it tangible. “It is no small achievment to have opened the eyes of even a few million Americans to these facts,” Bruce Bliven, editor of the New Republic observed. “If the Townsend Plan were to die tomorrow and be completely forgotten as miniature golf, mah-jongg, or flinch [editor’s note: everything old is new again], it would still have left some sedimented flood marks on the national consciousness.” Indeed, the Townsend movement became the catalyst for the New Deal’s signal achievement, the old-age program of Social Security. The history of its rise offers a lesson for the Occupy movement in how to convert grassroots enthusiasm into a potent political force – and a warning about the limitations of even a nationwide movement.

Does the author live up to the promises of this paragraph? Is the whole essay worth reading? Does FDR give in to the people’s demands and pass Social Security?!

Yes to all. Read it.

Hidden in Plain Sight by Gillian Tett (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

This is a great essay. I’m going to outsource the review and analysis to:

http://beyoubesure.com/2012/10/13/generation-lost-lazy-afraid/

because it basically sums up my thoughts. You all, go read it.

What Good is Wall Street? by John Cassidy

If you know nothing about Wall Street, then the essay is worth reading, otherwise skip it. There are two common ways to write a bad article in financial journalism. First, you can try to explain tiny index price movements via news articles from that day/week/month. “Shares in the S&P moved up on good news in Taiwan today,” that kind of nonsense. While the news and price movements might be worth knowing for their own sake, these articles are usually worthless because no journalist really knows who traded and why (theorists might point out even if the journalists did know who traded to generate the movement and why, it’s not clear these articles would add value – theorists are correct).

The other way, the Cassidy! way is to ask some subgroup of American finance what they think about other subgroups in finance. High frequency traders think iBankers are dumb and overpaid, but HFT on the other hand, provides an extremely valuable service – keeping ETFs cheap, providing liquidity and keeping shares the right level. iBankers think prop-traders add no value, but that without iBanking M&A services, American manufacturing/farmers/whatever would cease functioning. Low speed prop-traders think that HFT just extracts cash from dumb money, but prop-traders are reddest blooded American capitalists, taking the right risks and bringing knowledge into the markets. Insurance hates hedge funds, hedge funds hate the bulge bracket, the bulge bracket hates the ratings agencies, who hate insurance and on and on.

You can spit out dozens of articles about these catty and tedious rivalries (invariably claiming that financial sector X, rivals for institutional cash with Y, “adds no value”) and learn nothing about finance. Cassidy writes the article taking the iBankers side and surprises no one (this was originally published as an article in The New Yorker).

Your House as an ATM by Bethany McLean

Ms. McLean holds immense talent. It was always pretty obvious that the bottom twenty-percent, i.e. the vast majority of subprime loan recipients, who are generally poor at planning, were using mortgages to get quick cash rather than buy houses. Regulators and high finance, after resisting for a good twenty years, gave in for reasons explained in Rajan’s essay.

Against Political Capture by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (sorry I couldn’t find a URL, for this original essay you’ll have to buy the book).

A legit essay by a future Nobelist in Econ. Read it.

A Nation of Business Junkies by Arjun Appadurai

Anthro-hack Appadurai writes:

I first came to this country in 1967. I have been either a crypto-anthropologist or professional anthropologist for most of the intervening years. Still, because I came here with an interest in India and took the path of least resistance in choosing to retain India as my principal ethnographic referent, I have always been reluctant to offer opinions about life in these United States.

His instincts were correct. The essay reads like an old man complaining about how bad the weather is these days. Skip it.

Causes of Financial Crises Past and Present: The Role of This-Time-Is-Different Syndrome by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff

Editor Byrne has amazing powers of persuasion or, a lot of authors have had some essays in the desk-drawer they were waiting for an opportunity to publish. In any case, Rogoff and Reinhart (RR hereafter) have summed up a couple hundred studies and two of their books in a single executive summary and given it to whoever buys The Occupy Handbook. Value. RR are Republicans and the essay appears to be written in good faith (unlike some people *cough* Tyler Cowen and Veronique de Rugy *cough*). RR do a great job discovering and presenting stylized facts about financial crises past and present. What to expect next? A couple national defaults and maybe a hyperinflation or two.

Government As Tough Love by Robert Shiller as interviewed by Brandon Adams (buy the book)!

Shiller has always been ahead of the curve. In 1981, he wrote a cornerstone paper in behavioral finance at a time when the field was in its embryonic stages. In the early 1990s, he noticed insufficient attention was paid to real estate values, despite their overwhelming importance to personal wealth levels; this led him to create, along with Karl E. Case, the Case-Shiller index – now the Case-Shiller Home Prices Indices. In March 2000**, Shiller published Irrational Exuberance, arguing that U.S. stocks were substantially overvalued and due for a tumble. [Editor’s note: what Brandon Adams fails to mention, but what’s surely relevant is that Shiller also called the subprime bubble and re-released Irrational Exuberance in 2005 to sound the alarms a full three years before The Subprime Solution]. In 2008, he published The Subprime Solution, which detailed the origins of the housing crisis and suggested innovative policy responses for dealing with the fallout. These days, one of his primary interests is neuroeconomics, a field that relates economic decision-making to brain function as measured by fMRIs.

Shiller is basically a champ and you should listen to him.

Shiller was disappointed but not surprised when governments bailed out banks in extreme fashion while leaving the contracts between banks and homeowners unchanged. He said, of Hank Paulson, “As Treasury secretary, he presented himself in a very sober and collected way…he did some bailouts that benefited Goldman Sachs, among others. And I can imagine that they were well-meaning, but I don’t know that they were totally well-meaning, because the sense of self-interest is hard to clean out of your mind.”

Shiller understates everything.

Verdict: Read it.

And so, we close our discussion of part I. Moving on to part II:

In Ms. Byrne’s own words:

Part 2, “Where We Are Now,” which covers the present, both in the United States and abroad, opens with a piece by the anthropologist David Graeber. The world of Madison Avenue is far from the beliefs of Graeber, an anarchist, but it’s Graeber who arguably (he says he didn’t do it alone) came up with the phrase “We Are the 99 percent.” As Bloomberg Businessweek pointed out in October 2011, during month two of the Occupy encampments that Graeber helped initiate and three moths after the publication of his Debt: The First 5,000 Years, “David Graeber likes to say that he had three goals for the year: promote his book, learn to drive, and launch a worldwide revolution. The first is going well, the second has proven challenging and the third is looking up.” Graeber’s counterpart in Chile can loosely be said to be Camila Vallejo, the college undergraduate, pictured on page 219, who, at twenty-three, brought the country to a standstill. The novelist and playwright Ariel Dorfman writes about her and about his own self-imposed exile from Chile, and his piece is followed by an entirely different, more quantitative treatment of the subject. This part of the book also covers the indignados in Spain, who before Occupy began, “occupied” the public squares of Madrid and other cities – using, as the basis for their claim on the parks could be legally be slept in, a thirteenth-century right granted to shepherds who moved, and still move, their flocks annually.

In other words, we’re in occupy is the hero we deserve, but not the hero we need territory here.

*Addendum 1: Some have suggested that it’s not the wealth inequality that ought to be reduced, but the democratic elements of our system. California’s terrible decision–making resulting from its experiments with direct democracy notwithstanding, I would like to stay in the realm of the sane.

**Addendum 2: Yes, Shiller managed to get the book published the week before the crash. Talk about market timing.

Guest Post SuperReview Part II of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I: How We Got Here

Whatsup.

This is a review of Part I of The Occupy Handbook. Part I consists of twelve pieces ranging in quality from excellent to awful. But enough from me, in Janet Byrne’s own words:

Part 1, “How We Got Here,” takes a look at events that may be considered precursors of OWS: the stories of a brakeman in 1877 who went up against the railroads; of the four men from an all-black college in North Carolina who staged the first lunch counter sit-in of the 1960s; of the out-of-work doctor whose nationwide, bizarrely personal Townsend Club movement led to the passage of Social Security. We go back to the 1930s and the New Deal and, in Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff‘s “nutshell” version of their book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, even further.

Ms. Byrne did a bang-up job getting one Nobel Prize Winner in economics (Paul Krugman), two future Economics Nobel Prize winners (Robert Shiller, Daron Acemoglu) and two maybes (sorry Raghuram Rajan and Kenneth Rogoff) to contribute excellent essays to this section alone. Powerhouse financial journalists Gillian Tett, Michael Hilztik, John Cassidy, Bethany McLean and the prolific Michael Lewis all drop important and poignant pieces into this section. Arrogant yet angry anthropologist Arjun Appadurai writes one of the worst essays I’ve ever had the misfortune of reading and the ubiquitous Brandon Adams make his first of many mediocre appearances interviewing Robert Shiller. Clocking in at 135 pages, this is the shortest section of the book yet varies the most in quality. You can skip Professor Appadurai and Cassidy’s essays, but the rest are worth reading.

Advice from the 1 Percent: Lever Up, Drop Out by Michael Lewis

Framed as a strategy memo circulated among one-percenters, Lewis’ satirical piece written after the clearing of Zucotti Park begins with a bang.

The rabble has been driven from the public parks. Our adversaries, now defined by the freaks and criminals among them, have demonstrated only that they have no idea what they are doing. They have failed to identify a single achievable goal.

Indeed, the absurd fixation on holding Zuccotti Park and refusal to issue demands because doing so “would validate the system” crippled Occupy Wall Street (OWS). So far OWS has had a single, but massive success: it shifted the conversation back to the United States’ out of control wealth inequality managed to do so in time for the election, sealing the deal on Romney. In this manner, OWS functioned as a holding action by the 99% in the interests of the 99%.

We have identified two looming threats: the first is the shifting relationship between ambitious young people and money. There’s a reason the Lower 99 currently lack leadership: anyone with the ability to organize large numbers of unsuccessful people has been diverted into Wall Street jobs, mainly in the analyst programs at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Those jobs no longer exist, at least not in the quantities sufficient to distract an entire generation from examining the meaning of their lives. Our Wall Street friends, wounded and weakened, can no longer pick up the tab for sucking the idealism out of America’s youth.We on the committee are resigned to all elite universities becoming breeding grounds for insurrection, with the possible exception of Princeton.

Michael Lewis speaks from experience; he is a Princeton alum and a 1 percenter himself. More than that however, he is also a Wall Street alum from Salomon Brothers during the 1980s snafu and wrote about it in the original guide to Wall Street, Liar’s Poker. Perhaps because of his atypicality (and dash of solipsism), he does not have a strong handle on human(s) nature(s). By the time of his next column in Bloomberg, protests had broken out at Princeton.

Ultimately ineffectual, but still better than…

Lewis was right in the end, but more than anyone sympathetic to the movement might like. OccupyPrinceton now consists of only two bloggers, one of which has graduated and deleted all his work from an already quiet site and another who is a senior this year. OccupyHarvard contains a single poorly written essay on the front page. Although OccupyNewHaven outlasted the original Occupation, Occupy Yale no longer exists. Occupy Dartmouth hasn’t been active for over a year, although it has a rather pathetic Twitter feed here. Occupy Cornell, Brown, Caltech, MIT and Columbia don’t exist, but some have active facebook pages. Occupy Michigan State, Rutgers and NYU appear to have had active branches as recently as eight months ago, but have gone silent since. Functionally, Occupy Berkeley and its equivalents at UCBerkeley predate the Occupy movement and continue but Occupy Stanford hasn’t been active for over a year. Anecdotally, I recall my friends expressing some skepticism that any cells of the Occupy movement still existed.

As for Lewis’ other points, I’m extremely skeptical about “examined lives” being undermined by Wall Street. As someone who started in math and slowly worked his way into finance, I can safely say that I’ve been excited by many of the computing, economic, and theoretical problems quants face in their day-to-day work and I’m typical. I, and everyone who has lived long-enough, knows a handful of geniuses who have thought long and hard about the kinds of lives they want to lead and realized that A. there is no point to life unless you make one and B. making money is as good a point as any. I know one individual, after working as a professional chemist prior to college,who decided to in his words, “fuck it and be an iBanker.” He’s an associate at DB. At elite schools, my friend’s decision is the rule rather than the exception, roughly half of Harvard will take jobs in finance and consulting (for finance) this year. Another friend, an exception, quit a promising career in operations research to travel the world as a pick-up artist. Could one really say that either the operations researcher or the chemist failed to examine their lives or that with further examinations they would have come up with something more “meaningful”?

One of the social hacks to give lie to Lewis-style idealism-emerging-from-an attempt-to-examine-ones-life is to ask freshpeople at Ivy League schools what they’d like to do when they graduate and observe their choices four years later. The optimal solution for a sociopath just admitted to a top school might be to claim they’d like to do something in the peace corp, science or volunteering for the social status. Then go on to work in academia, finance, law or tech or marriage and household formation with someone who works in the former. This path is functionally similar to what many “average” elite college students will do, sociopathic or not. Lewis appears to be sincere in his misunderstanding of human(s) nature(s). In another book he reveals that he was surprised at the reaction to Liar’s Poker – most students who had read the book “treated it as a how-to manual” and cynically asked him for tips on how to land analyst jobs in the bulge bracket. It’s true that there might be some things money can’t buy, but an immensely pleasurable, meaningful life do not seem to be one of them. Today for the vast majority of humans in the Western world, expectations of sufficient levels of cold hard cash are necessary conditions for happiness.

In short and contra Lewis, little has changed. As of this moment, Occupy has proven so harmless to existing institutions that during her opening address Princeton University’s president Shirley Tilghman called on the freshmen in the class of 2016 to “Occupy” Princeton. No freshpeople have taken up her injunction. (Most?) parts of Occupy’s failure to make a lasting impact on college campuses appear to be structural; Occupy might not have succeeded even with better strategy. As the Ivy League became more and more meritocratic and better at discovering talent, many of the brilliant minds that would have fallen into the 99% and become its most effective advocates have been extracted and reached their so-called career potential, typically defined by income or status level. More meritocratic systems undermine instability by making the most talented individuals part of the class-to-be-overthrown, rather than the over throwers of that system. In an even somewhat meritocratic system, minor injustices can be tolerated: Asians and poor rural whites are classes where there is obvious evidence of discrimination relative to “merit and the decision to apply” in elite gatekeeper college admissions (and thus, life outcomes generally) and neither group expresses revolutionary sentiment on a system-threatening scale, even as the latter group’s life expectancy has begun to decline from its already low levels. In the contemporary United States it appears that even as people’s expectations of material security evaporate, the mere possibility of wealth bolsters and helps to secure inequities in existing institutions.

Lewis continues:

Hence our committee’s conclusion: we must be able to quit American society altogether, and they must know it.The modern Greeks offer the example in the world today that is, the committee has determined, best in class. Ordinary Greeks seldom harass their rich, for the simple reason that they have no idea where to find them. To a member of the Greek Lower 99 a Greek Upper One is as good as invisible.

He pays no taxes, lives no place and bears no relationship to his fellow citizens. As the public expects nothing of him, he always meets, and sometimes even exceeds, their expectations. As a result, the chief concern of the ordinary Greek about the rich Greek is that he will cease to pay the occasional visit.

Michael Lewis is a wise man.

I can recall a conversation with one of my Professors; an expert on Democratic Kampuchea (American: Khmer Rouge), she explained that for a long time the identity of the oligarchy ruling the country was kept secret from its citizens. She identified this obvious subversion of republican principles (how can you have control over your future when you don’t even know who runs your region?) as a weakness of the regime. Au contraire, I suggested, once you realize your masters are not gods, but merely humans with human characteristics, that they: eat, sleep, think, dream, have sex, recreate, poop and die – all their mystique, their claims to superior knowledge divine or earthly are instantly undermined. De facto segregation has made upper classes in the nation more secure by allowing them to hide their day-to-day opulence from people who have lost their homes, job and medical care because of that opulence. Neuroscience will eventually reveal that being mysterious makes you appear more sexy, socially dominant, and powerful, thus making your claims to power and dominance more secure (Kautsky et. al. 2018).*

If the majority of Americans manage to recognize that our two tiered legal system has created a class whose actual claim to the US immense wealth stems from, for the most part, a toxic combination of Congressional pork, regulatory and enforcement agency capture and inheritance rather than merit, there will be hell to pay. Meanwhile, resentment continues to grow. Even on the extreme right one can now regularly read things like:

Now, I think I’d be downright happy to vote for the first politician to run on a policy of sending killer drones after every single banker who has received a post-2007 bonus from a bank that received bailout money. And I’m a freaking libertarian; imagine how those who support bombing Iraqi children because they hate us for our freedoms are going to react once they finally begin to grasp how badly they’ve been screwed over by the bankers. The irony is that a banker-assassination policy would be entirely constitutional according to the current administration; it is very easy to prove that the bankers are much more serious enemies of the state than al Qaeda. They’ve certainly done considerably more damage.

Wise financiers know when it’s time to cash in their chips and disappear. Rarely, they can even pull it off with class.

The rest of part I reviewed tomorrow. Hang in there people.

Addendum 1: If your comment amounts to something like “the Nobel Prize in Economics is actually called the The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel” and thus “not a real Nobel Prize” you are correct, yet I will still delete your comment and ban your IP.

*Addendum 2: More on this will come when we talk about the Saez-Delong discussion in part III.

Guest Post SuperReview Part I of VI: The Occupy Handbook

Whassup.

It has become a truism that as the amount of news and information generated per moment continues to grow, so too does the value of aggregation, curation and editing. A point less commonly made is that these aggregators are often limited by time in the sense, whatever the topic, the value of news for the median reader decays extremely rapidly. Some extremists even claim that it’s useless to read the newspaper, so rapidly do things change. The forty eight hours news cycle, in addition to destroying context, has made it impossible for both reporters and viewers to learn from history. See “Is News Memoryless?” (Kautsky et. al. 2014).

A more promising approach to news aggregation (for those who read the news with purpose) is to organize pieces by subject and publish those articles in a book. Paul Krugman did this for himself in The Great Unraveling, bundling selected columns from 1999 to 2003 into a single book, with chapters organized by subject and proceeding chronologically. While the rise and rise of Krumgan’s real-time blogging virtually guarantees he’ll never make such an effort again, a more recent try came from uber-journalist Michael Lewis in Panic!: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity. Financial journalists’ myopic perspective at any given point in time make financial column compilations of years past particularly fun(ny) to read.

Nothing is staler than yesterday’s Wall Street journal (financial news spoils quickly) and reading WSJ or Barron’s pieces from 10 to 20 years ago is just painful.

The title PANIC: The story of modern financial insanity led me to believe the book was about the current crises. The book does say, in very, very fine print “Edited by” Michael Lewis.

-Fritz Krieger, Amazon Reviewer and chief scientist at ISIS

Unfortunately, some philistines became angry in 2008 when they insta-purchased a book called Panic! by Michael Lewis and to their horror, discovered that it contained information about prior financial crises, the nerve of the author to bring us historical perspective, even worse…some of that perspective relating to nations other than the ole’ US of A.

As the more alert readers have noted, almost nothing in the book concerns the 2008 Credit Meltdown, but instead this is merely a collection of news clippings and old magazine articles about past financial crises. You might as well visit a chiropodist’s office and offer them a couple of bucks for their old magazines.

Granted, the articles are by some of today’s finest and most celebrated journalists (although some of the news clippings are unsigned), but do you really want to read more about the 1987 crash or the 1997 collapse of the Thai Baht?

Perhaps you do, but whoever threw this book together wasn’t very particular about the articles chosen. Page 193 reprints an article from “Barron’s” of March, 2000 in which Jack Willoughby presents a long list of Internet companies that he considered likely to run out of cash by 2001. “Some can raise more funds through stock and bond offerings,” he warns. “Others will be forced to go out of business. It’s Darwinian capitalism at work.” True, many of the companies he listed did go belly-up, but on his list of the doomed are

[..]Amazon.com– Someone named Keith Otis Edwards

Perhaps because I was abroad for both the initial disaster and the entire Occupation of Zucotti Park, both events have held my attention. So it is with a mixture of hope and apprehension that I picked up Princeton alum Janet Byrne’s The Occupy Handbook from the public library. The Occupy Handbook is a collection of essays written from 2010 to 2011 by an assortment of first and second-rate authors that attempt to: show what Wall Street does and what it did that led to the most recent crash, explain why our policy apparatus was paralyzed in response to the crash, describe how OWS arose and how it compared with concurrent international movements and prior social movements in the US, and perhaps most importantly, provide policy solutions for the 99% in finance and economics. Janet Byrne begins with a heartfelt introduction:

One fall morning I stood outside the Princeton Club, on West 43rd Street in Manhattan. Occupy Wall Street, which I had visited several times as a sympathetic outsider, has passed its one month anniversary, and I thought the movement might be usefully analyzed by economists and financial writers whose pieces I would commission and assemble into a book that was analytical and- this was what really interested me – prescriptive. I’d been invited to breakfast to talk about the idea with a Princeton Club member and had arrived early out of nervousness.

It seemed a strange place to be discussing the book. I tried the idea out on a young bellhop…

And so it continues. The book is divided into three parts. Part I, broadly speaking, tries to give some economic background on the crash and the ensuing political instability that the crash engendered, up to the first occupation of Zuccotti Park. Part II, broadly speaking, describes the events in Zuccotti Park and around the world as they were in those critical months of fall 2011. Part III, broadly speaking, prescribes solutions to current depression. I say broadly speaking because, as you will see, several essays appear to be in the wrong part and in the worst cases, in the wrong book.

Data science code of conduct, Evgeny Morozov

I’m going on an 8-day long trip to Seattle with my family this morning and I’m taking the time off from mathbabe. But don’t fret! I have a crack team of smartypants skeptics who are writing for me while I’m gone. I’m very much looking forward to seeing what Leon and Becky come up with.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with two things I’m reading today.

First, a proposed Data Science Code of Professional Conduct. I don’t know anything about the guys at Rose Business Technologies who wrote it except that they’re from Boulder Colorado and have had lots of fancy consulting gigs. But I am really enjoying their proposed Data Science Code. An excerpt from the code after they define their terms:

(c) A data scientist shall rate the quality of evidence and disclose such rating to client to enable client to make informed decisions. The data scientist understands that evidence may be weak or strong or uncertain and shall take reasonable measures to protect the client from relying and making decisions based on weak or uncertain evidence.

(d) If a data scientist reasonably believes a client is misusing data science to communicate a false reality or promote an illusion of understanding, the data scientist shall take reasonable remedial measures, including disclosure to the client, and including, if necessary, disclosure to the proper authorities. The data scientist shall take reasonable measures to persuade the client to use data science appropriately.

(e) If a data scientist knows that a client intends to engage, is engaging or has engaged in criminal or fraudulent conduct related to the data science provided, the data scientist shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the proper authorities.

(f) A data scientist shall not knowingly:

- fail to use scientific methods in performing data science;

- fail to rank the quality of evidence in a reasonable and understandable manner for the client;

- claim weak or uncertain evidence is strong evidence;

- misuse weak or uncertain evidence to communicate a false reality or promote an illusion of understanding;

- fail to rank the quality of data in a reasonable and understandable manner for the client;

- claim bad or uncertain data quality is good data quality;

- misuse bad or uncertain data quality to communicate a false reality or promote an illusion of understanding;

- fail to disclose any and all data science results or engage in cherry-picking;

Read the whole Code of Conduct here (and leave comments! They are calling for comments).

Second, my favorite new Silicon Valley curmudgeon is named Evgeny Morozov, and he recently wrote an opinion column in the New York Times. It’s wonderfully cynical and makes me feel like I’m all sunshine and rainbows in comparison – a rare feeling for me! Here’s an excerpt (h/t Chris Wiggins):

Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg concurs: “There are a lot of really big issues for the world that need to be solved and, as a company, what we are trying to do is to build an infrastructure on top of which to solve some of these problems.” As he noted in Facebook’s original letter to potential investors, “We don’t wake up in the morning with the primary goal of making money.”

Such digital humanitarianism aims to generate good will on the outside and boost morale on the inside. After all, saving the world might be a price worth paying for destroying everyone’s privacy, while a larger-than-life mission might convince young and idealistic employees that they are not wasting their lives tricking gullible consumers to click on ads for pointless products. Silicon Valley and Wall Street are competing for the same talent pool, and by claiming to solve the world’s problems, technology companies can offer what Wall Street cannot: a sense of social mission.

Read the whole thing here.

Modeling in Plain English

I’ve been enjoying my new job at Johnson Research Labs, where I spend a majority of the time editing my book with my co-author Rachel Schutt. It’s called Doing Data Science (now available for pre-purchase at Amazon), and it’s based on these notes I took last semester at Rachel’s Columbia class.

Recently I’ve been working on Brian Dalessandro‘s chapter on logistic regression. Before getting into the brass tacks of that algorithm, which is especially useful when you are trying to predict a binary outcome (i.e. a 0 or 1 outcome like “will click on this ad”), Brian discusses some common constraints to models.

The one that’s particularly interesting to me is what he calls “interpretability”. His example of an interpretability constraint is really good: it turns out that credit card companies have to be able to explain to people why they’ve been rejected. Brain and I tracked down the rule to this FTC website, which explains the rights of consumers who own credit cards. Here’s an excerpt where I’ve emphasized the key sentences:

You Also Have The Right To…

- Have credit in your birth name (Mary Smith), your first and your spouse’s last name (Mary Jones), or your first name and a combined last name (Mary Smith Jones).

- Get credit without a cosigner, if you meet the creditor’s standards.

- Have a cosigner other than your spouse, if one is necessary.

- Keep your own accounts after you change your name, marital status, reach a certain age, or retire, unless the creditor has evidence that you’re not willing or able to pay.

- Know whether your application was accepted or rejected within 30 days of filing a complete application.

- Know why your application was rejected. The creditor must tell you the specific reason for the rejection or that you are entitled to learn the reason if you ask within 60 days. An acceptable reason might be: “your income was too low” or “you haven’t been employed long enough.” An unacceptable reason might be “you didn’t meet our minimum standards.” That information isn’t specific enough.

- Learn the specific reason you were offered less favorable terms than you applied for, but only if you reject these terms. For example, if the lender offers you a smaller loan or a higher interest rate, and you don’t accept the offer, you have the right to know why those terms were offered.

- Find out why your account was closed or why the terms of the account were made less favorable, unless the account was inactive or you failed to make payments as agreed.

The result of this rule is that credit card companies must use simple models, probably decision trees, to make their rejection decisions.

It’s a new way to think about modeling choice, to be sure. It doesn’t necessarily make for “better” decisions from the point of view of the credit card company: random forests, a generalization of decision trees, are known to be more accurate, but are arbitrarily more complicated to explain.

So it matters what you’re optimizing for, and in this case the regulators have decided we’re optimizing for interpretability rather than accuracy. I think this is appropriate, given that consumers are at the mercy of these decisions and relatively powerless to act against them (although the FTC site above gives plenty of advice to people who have been rejected, mostly about how to raise their credit scores).

Three points to make about this. First, I’m reading the Bankers New Clothes, written by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig (h/t Josh Snodgrass), which is absolutely excellent – I’m planning to write up a review soon. One thing they explain very clearly is the cost of regulation (specifically, higher capital requirements) from the bank’s perspective versus from the taxpayer’s perspective, and how it genuinely seems “expensive” to a bank but is actually cost-saving to the general public. I think the same thing could be said above for the credit card interpretability rule.

Second, it makes me wonder what else one could regulate in terms of plain english modeling. For example, what would happen if we added that requirement to, say, the teacher value-added model? Would we get much-needed feedback to teachers like, “You don’t have enough student participation”? Oh wait, no. The model only looks at student test scores, so would only be able to give the following kind of feedback: “You didn’t raise scores enough. Teach to the test more.”

In other words, what I like about the “Modeling in Plain English” idea is that you have to be able to first express and second back up your reasons for making decisions. It may not lead to ideal accuracy on the part of the modeler but it will lead to much greater clarity on the part of the modeled. And we could do with a bit more clarity.

Finally, what about online loans? Do they have any such interpretability rule? I doubt it. In fact, if I’m not wrong, they can use any information they can scrounge up about someone to decide on who gets a loan, and they don’t have to reveal their decision-making process to anyone. That seems unreasonable to me.

Aunt Pythia’s advice – sex edition

I’m afraid the concept of “giving advice” has been taken down a notch this week, considering how many ridiculous examples we have right now of people are giving advice as a way of congratulating themselves. It’s enough to confuse an advice columnist and put her into an existential angst spiral.

However, it’s not going to stop Aunt Pythia!

At most it will divert her to talk exclusively about something that nobody doesn’t love reading, namely sex. It’s a tried and true last resort of the advice columnist: let out the dirty laundry of yourself and everybody who dares bare themselves to you. I don’t see where this could go wrong.

Having said that, I’m not promising to be exclusive like this every week. I’ll probably cheat on you people every now and then and answer questions about how to get a job in data science or something. Also, my guest advice columnist next week, Aunt Orthoptera, will answer whatever questions she chooses (from a grasshopper’s perspective, of course).

By the way, if you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Please submit your smutty sex questions at the bottom of this column!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How can I make compatible my sexual attraction for dominant women and my fear of being controlled?

Horny in Montana

Dear Horny,

Let me start out by admitting honestly that I have no direct advice for you. I just don’t know how to resolve issues surrounding sexuality, and I’d be deeply skeptical of anybody who claims to be able to do so.

Sexuality is a crazy thing, a super entrenched and powerful force, and there’s just nothing and nobody who can change it for you once it’s on a roll. Sometimes people seem to be able to change it for themselves, mainly by repressing it, but that’s always so amazing, not to mention deeply threatening, I wouldn’t proffer it as advice.

I sometimes think of my own sexuality as having a personality, and an agenda, that I can only observe, not control. The best case scenario for me has evolved into trying not to be too judgmental of it and to and make sure nothing unsafe happens. I’m like a benign referee of my own dirty urges.

Having said that, I have two pieces of indirect advice for you. First, it would probably be useful to separate sex play with “normal life” and realize that you can ask someone to dominate you in the bedroom, and even pretend to control you, and even actually control you, whilst remaining nothing like that outside the bedroom. That’s totally normal and common and it might help in the sense that you’d actually have control over being controlled: it would happen if and when you wanted it.

The second piece of advice I have it totally selfish, namely, please don’t blame the women of the world for your unresolved problems. Just because you’re both attracted and afraid of these dominant women doesn’t mean they have a responsibility to deal with your confusion and frustration. Don’t take it out on them.

I hope that helps,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What would you say to a woman who told you that she is not able to make a commitment to anyone because she regularly finds herself in search of romance (not originating from sexual desires) with other people? Do you think this is a common behavior?

Itchy Litchi

Dear Itchy,

There are three stages of understanding in this story, at least for me.

First, you know yourself (I’ll refer to “you” even though you might have been asking on behalf of someone else) pretty well if you avoid commitment based on a theoretical understanding of your roaming eye. Most people I know throw themselves into commitment in spite of really good evidence that they won’t be able to sustain it, due to their cognitive biases.

Second, you claim your romantic urges for other people are not sexual. Theoretically this may be true, but in my experience romantic urges are always sexual if you probe deep enough or if they get strong enough. So either I’m a sex maniac (possible) or else you’re in denial about those nonsexual romantic urges.

Third, let’s put the above two together: A) you know yourself deeply, and B) you’re in total denial. The second conclusion makes me rethink the first, honestly, and I come to the conclusion that the first conclusion was wrong. You aren’t avoiding commitment because you know yourself so well, but rather because you’re avoiding commitment for some reason. Maybe you’re afraid of commitment? Maybe you’re afraid of sexual urges, which is why you both avoid commitment and avoid admitting your romantic urges are sexual?

Finally, if this question was actually written by, say, a man who wanted to understand the reasoning a woman gave him for why she couldn’t commit to him: she just wasn’t that into you. And yes that’s a very common behavior.

I hope that helps!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I just studied the “Authentic Women’s Penis Size Preference Chart” (I say “studied” because I need to convert everything to metric units to make any sense of it) and, while – unlike many men, I am told – I am not too concerned about length, I feel that the ideal circumference IS REALLY BIG, at least for a man’s penis. Is this for real? Are women looking all their life for that eluding ideal-sized penis or am I just unlucky?

Concerned Reader

Dear Concerned,

Once again here’s the chart for the readers who missed it last time:

To answer your primary question, it’s not the length, it’s the girth. A truer statement has never been said. Of course, there are exceptions to that rule, namely if the length is truly miniscule.

Now, I do have some comforting words for you, you’ll be happy to know. Namely, my guess is that women responding to this very scientific poll had a biased measurement error. Namely, they didn’t have (probably) an erect penis handy and a flexible measuring tape as well, by their side, whilst answering the poll (apologies to the women who did!).

So what they did is they eyeballed the “circumference” measurement by imaging holding a penis in their hand like an OK sign:

And then, since it’s hard to measure a circle, they then straightened out their fingers. The reason this is so biased is that your fingers and thumb are actually quite a bit longer once you’ve stopped making the OK sign.

There may be a measurement bias of up to 50% on this. Probably not, but I’m trying to make you feel better.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please please please submit questions! Especially if they are grasshopper-related!

Data audits and data strategies

There are lots of start-up companies out there that want to have a data team, because they heard somewhere that they should leverage big data, but they don’t know what it really means, what they can expect from such a team, or how to get started. They also don’t really know how to hire qualified people, or what qualifications to look for.

Finally, they often don’t know what kinds of questions are answerable through data, nor what data they should be collecting to answer those questions. So even if they did manage to hire a data scientist or a data team, those guys might be literally sitting on their hands for six months until they have enough data to start work.

It’s a common situation and could end up a big waste time and money. What these companies need is something I like to call a “data audit” followed by a “data strategy”.

Data Audit

First thing’s first. Do you actually need a data team? Is your company a data science company or is it a traditional-style company that happens to collect data? It would be a waste of resources to form a data team you don’t need. There’s no reason every single company needs to consider itself part of the big data revolution just to be cool.

Here’s how you tell. Let’s say that, as of now, you’re using incoming data to monitor and report on what’s happening with the business and to keep tabs on various indicators to make sure things aren’t going to hell. Absolutely every company should do this, but it honestly could be set up by a good data analyst working closely with the end-users, i.e. the business peeps.

What are the high-level goals of using data in the business? In particular, is there a way that, if you could really know how customers or clients were interacting with your product, that you would change the product to respond to the data? Because that feedback loop is the hallmark of a true data science engine (versus data analytics).

Here are some extreme examples to give you an idea of what I’m talking about. If you make shoes, then you need data to see how sales are and which shoes are getting sold faster so you can kick up production in certain areas. You need to see how sales are seasonal so you know to stop making quite so many shoes at a certain point in the deep of winter. But that’s about it, and you should be able to make do with data analysis.

If, on the other hand, you are building a recommendation engine, say for music, then you need to constantly refresh and improve your recommendation model. Your model is your product, and you need a data team.

Not all examples are this easy. Sometimes you can use new kinds of data models to improve your product even if it seems somewhat traditional, depending on how much data you are able to collect about how your clients use your product. It all depends on what kinds of questions you are asking and what data you have access to. Of course, you might want to go out and collect data that you hadn’t bothered to do before, which could bring you from the first category to the second.

Say you decide you really are a data science company, or want to be one. What’s next?

Pose a bunch of questions you think you’ll need to answer and a bunch of data you think should be useful to answer them.

The heart of a data audit is a (preliminary) plan for choosing, collecting, and storing data, as well as figuring out the initial shape of the data pipeline and infrastructure. Do you store data in the cloud? Is it unstructured or do you set up some overnight jobs to put stuff into some type of database? Do you aggregate data and throw some stuff away, or do you keep absolutely everything?

The most important issue above is whether you’re collecting enough data. Truth be told, you could probably throw it all into an unstructured pile on S3 for now and figure out pipelines later. It might not be the best way to do it but if you are short for time and attention, it’s possible, and storage is cheap. But make sure you’re collecting the right stuff!

You’d be surprised how many startups want to ask good questions about their customers to improve their product, and have gone to some trouble to figure out what those questions are, but don’t bother to collect the relevant information. They might do things like count the number of users, or collect a timestamp for whenever a user logs in, but they don’t actually keep track of the interaction. It’s essential that you collect pertinent information if you want to use this data to check things are working or to predict people’s desires or needs.

So if you think customers might be all ditching your site at critical moments, then definitely tag their departure as well as their arrival, and keep track of where they were and what they were doing when they bailed.

Note I’m not necessarily being creepy here. You definitely want to know how people interact with your product and your site, and it doesn’t need to be personal information you’re collecting about your users. It could be kept aggregate. You could find out that 45% of people leave your site when you ask them for their phone number, and then you might decide it’s not worth it to do that.

Speaking of creepy, another critical thing to consider during your data audit is privacy controls and encryption methods. Are you saving data legally? Are you protecting it legally? Are you informing your users appropriately about how and what data will be stored? Are you planning to remain consistent with your stated privacy policy? Do you respect people’s “Do Not Track” option?

At the end of a data audit, you might still have a vague idea of what exactly you can do with your data, but you should have a bunch of possible ideas, as well as guesses at what kind of attributes would contribute to the kind of behavior you’re considering tracking.

Then, after you start collecting high-quality data and figuring out the basic questions you care about, you will probably have to wait a few weeks or months to start training and implementing your models. This is a good time to make sure your data infrastructure is in place and doesn’t have major bugs.

Data Strategy

Ok, now you’ve collected lots of data and you also have a bunch of questions you think may be answerable. It’s time to prioritize your questions and form a plan. For each question on your list, you’ll need to think about the following issues:

- Is it a monitor or an algorithm?

- Is it short-term, one-time analysis or should you set it up as a dashboard?

- How much data will you need to train the model?

- What is your expectation of the signal in the data you’re collecting?

- How useful will the results of the model be considering the range of signal and the quality of the answer?

- Do you need to go find proxy data? Should you start now?

- Which algorithms should you consider?

- What’s your evaluation method?

- Is it scalable?

- Can you do a baby version first or does it only make sense to go deep?

- Can you do a simpler version of it that’s much cheaper to build?

- How long will it probably take to train?

- How fast can it update?

- Will it be a pain to integrate it to the realtime system?

- What are the costs if it doesn’t work?

- What are the costs of not trying it? What else could you be doing with that time?

- How is the feedback loop expected to work?

- What is the impact of this model on the users?

- What is the impact of this model on the world at large? This is especially important if you’re creepy. Don’t be creepy.

Also, you need a team to build your models. How do you hire? Who do you hire? Some of these answers depend on your above plan. If there’s a lot of realtime updating for your models you’ll need more data engineers and fewer pure modelers. If you need excellent-looking results from your work you’ll need more data viz nerds.

You should consider hiring a consultant just to interview for you. It’s really hard to interview for data scientists if nobody is an expert in data science, and you might end up with someone who knows how to sounds smart but can’t build anything. Or you could end up with someone who can build anything but has no idea what their choices really mean.

The ultimate goal at the end of a data audit and strategy is to end up with a reasonable expectation of what having a data science team will accomplish, how long it will take, how deep an investment it is, and how to do it.

“The problem here is not the message. The problem is the messenger.”

Today’s post is basically going to consist of me wishing I’d written this Gawker piece which was actually written by Hamilton Nolan and was entitled “It Would Be Great if Millionaires Would Not Lecture Us on ‘Living With Less’”.

To enjoy it as much as I did, you’d have to read this New York Times Opinion piece first, in which Graham Hill, who made a bajillion dollars in the dot com era, realizes he had too much stuff and now has less stuff and is telling us how great it is. Most cloying line: “the things I consumed ended up consuming me.”

At the risk of quoting Nolan’s entire article (the title of my post is his), let me start you with this:

There is something about achieving great financial success that seduces people into believing that they are life coaches. This problem seems particularly endemic to the tech millionaire set. You are not simply Some Fucking Guy Who Sold Your Internet Company For a Lot of Money; you are a lifestyle guru, with many important and penetrating insight about How to Live that must be shared with the common people.

We would humbly request that this stop.

I’ll skip over some parts and get to where he talks about Amanda Palmer:

The problem here is not the message. The problem is the messenger. More specifically, it is the messenger using his own life as supporting evidence for the message. Were Graham Hill to simply write a fact-based essay arguing that Americans should cut down on material possessions in order to save the environment and gain peace of mind, he would doubtless hear a chorus of support. But for Graham Hill, a young millionaire who was fortunate enough to sell his “pre-Netscape browser” at the high point of the internet bubble, to say to the average American, “My journey through the perils of great wealth has bestowed me with wisdom that is directly applicable to you” is simply false. It is no wonder that Hill loved the recent TED talk by millionaire musician Amanda Palmer, in which she argued that it was perfectly fair for her to, for example, accept a free night of lodging in the home of poor Honduran immigrants and not pay them for it, because the beauty of her music is payment enough. Both are insulated enough from the realities of personal finance to forget about them entirely.

True! And I’d add more in the Amanda Palmer case. She and I went to the same high school and I have known her since she was in 7th grade.

I’ll tell you what. She’s not your average artist. She’s hugely exhibitionist. This has worked great for her, but is not a typical artistic personality. In fact she’s essentially a cult leader. So yes, when you’re an artist/ cult leader, it makes sense to “let your fans pay you”. But if you’re a typical starving, introverted, sensitive soul, then not so much. How can she speak for all artists and ask them to do stuff just like her? Or rather, why does she think it would scale?

Mind you, I’m guilty of this problem too. When I give advice, which I do all the time, I pretty much always tell people what works for me. But my evidence that the same approach would work for them is slight.

That begs the question, how do we do better than this? How do we tailor our advice to make it useful?

I kind of hate TED talks

The good

There are good things about TED talks. It’s nice to have a thoughtful articulate person saying something a little bit new and a little bit different. OK I’m done.

The annoying

Then there are annoying things about TED talks. People are so ridiculously polished. No idea is that perfect! Rumor has it that, after getting professionally trained for their TED performances, the producers then remove all the “umms” and awkward silences to make it even more perfect. Yuck.

Here’s one way to think about it: TED talks aren’t as good as blogs because they’re not interactive – the audience is expected to receive and not talk back. That’s why I prefer to blog in my underwear and bathrobe, imagining my friends on their living room sofas, also wearing pajamas, and objecting to my stupidity. And that’s why I like the feedback and the comments. It makes my ideas better.

At the same time, TED talks are not as deep as books, where you have enough time and space to actually think through an argument. How could you really develop a deep thought in 20 minutes? You just can’t.