Global move to austerity based on mistake in Excel

As Rortybomb reported yesterday on the Roosevelt Institute blog (hat tip Adam Obeng), a recent paper written by Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin looked into replicating the results of a economics paper originally written by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff entitled Growth in a Time of Debt.

The original Reinhart and Rogoff paper had concluded that public debt loads greater than 90 percent of GDP consistently reduce GDP growth, a “fact” which has been widely used. However, the more recent paper finds problems. Here’s the abstract:

Herndon, Ash and Pollin replicate Reinhart and Rogoff and find that coding errors, selective exclusion of available data, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics lead to serious errors that inaccurately represent the relationship between public debt and GDP growth among 20 advanced economies in the post-war period. They find that when properly calculated, the average real GDP growth rate for countries carrying a public-debt-to-GDP ratio of over 90 percent is actually 2.2 percent, not -0:1 percent as published in Reinhart and Rogo ff. That is, contrary to RR, average GDP growth at public debt/GDP ratios over 90 percent is not dramatically different than when debt/GDP ratios are lower.

The authors also show how the relationship between public debt and GDP growth varies significantly by time period and country. Overall, the evidence we review contradicts Reinhart and Rogoff ’s claim to have identified an important stylized fact, that public debt loads greater than 90 percent of GDP consistently reduce GDP growth.

A few comments.

1) We should always have the data and code for published results.

The way the authors Herndon, Ash and Pollin managed to replicate the results was that they personally requested the excel spreadsheets from Reinhart and Rogoff. Given how politically useful and important this result has been (see Rortybomb’s explanation of this), it’s kind of a miracle that they released the spreadsheet. Indeed that’s the best part of this story from a scientific viewpoint.

2) The data and code should be open source.

One cool thing is that now you can actually download the data – there’s a link at the bottom of this page. I did this and was happy to have a bunch of csv files and some (open source) R code which presumably recovers the excel spreadsheet mistakes. I also found some .dta files, which seems like Stata proprietary file types, which is annoying, but then I googled and it seems like you can use R to turn .dta files into csv files. It’s still weird that they wrote code in R but saved files in Stata.

3) These mistakes are easy to make and they’re mostly not considered mistakes.

Let’s talk about the “mistakes” the authors found. First, they’re excluding certain time periods for certain countries, specifically right after World War II. Second, they chose certain “non-standard” weightings for the various countries they considered. Finally, they accidentally excluded certain rows from their calculation.

Only that last one is considered a mistake by modelers. The others are modeling choices, and they happen all the time. Indeed it’s impossible not to make such choices. Who’s to say that you have to use standard country weightings? Why? How much data do you actually need to consider? Why?

[Aside: I’m sure there are proprietary trading models running right now in hedge funds that anticipate how other people weight countries in standard ways and betting accordingly. In that sense, using standard weightings might be a stupid thing to do. But in any case validating a weighting scheme is extremely difficult. In the end you’re trying to decide how much various countries matter in a certain light, and the answer is often that your country matters the most to you.]

4) We need to actually consider other modeling possibilities.

It’s not a surprise, to economists anyway, that after you include more post-WWII years of data, which we all know to be high debt and high growth years worldwide, you get a substantively different answer. Excluding these data points is just as much a political decision as a modeling decision.

In the end the only reasonable way to proceed is to describe your choices, and your reasoning, and the result, but also consider other “reasonable” choices and report the results there too. And if you don’t like the answer, or don’t want to do the work, at the very least you need to provide your code and data and let other people check how your result changes with different “reasonable” choices.

Once the community of economists (and other data-centric fields) starts doing this, we will all realize that our so-called “objective results” utterly depend on such modeling decisions, and are about as variable as our own opinions.

5) And this is an easy model.

Think about how many modeling decisions and errors are in more complicated models!

Tax haven in comedy: the Caymans (#OWS)

This is a guest post by Justin Wedes. A graduate of the University of Michigan with degrees in Physics and Linguistics with High Honors, Justin has taught formerly truant and low-income youth in subjects ranging from science to media literacy and social justice activism. A founding member of the New York City General Assembly (NYCGA), the group that brought you Occupy Wall Street, Justin continues his education activism with the Grassroots Education Movement, Class Size Matters, and now serves as the Co-Principal of the Paul Robeson Freedom School.

Yesterday was tax day, when millions of Americans fulfilled that annual patriotic ritual that funds roads, schools, libraries, hospitals, and all those pesky social services that regular people rely upon each day to make our country liveable.

Millions of Americans, yes, but not ALL Americans.

Some choose to help fund roads, schools, libraries, hospitals in other places instead. Like the Cayman Islands.

Don’t get me wrong – I love Caymanians. Beautifully hospitable people they are, and they enjoy arguably the most progressive taxes in the world: zero income tax and only the rich pay when they come to work – read “cook the books” – on their island for a few days a year. School is free, health care guaranteed to all who work. It’s a beautiful place to live, wholly subsidized by the 99% in developed countries like yours and mine.

When they stash their money abroad and don’t pay taxes while doing business on our land, using our workforce and electrical grids and roads and getting our tax incentives to (not) create jobs, WE pay.

We small businesses.

We students.

We nurses.

We taxpayers.

I went down to the Caymans myself to figure out just how easy it is to open an offshore tax haven and start helping Caymanians – and myself – rather than Americans.

Here’s what happened:

Interview with Chris Wiggins: don’t send me another $^%& shortcut alias!

When I first met Chris Wiggins of Columbia and hackNY back in 2011, he immediately introduced me to about a hundred other people, which made it obvious that his introductions were highly stereotyped. I thought he was some kind of robot, especially when I started getting emails from his phone which all had the same (long) phrases in them, like “I’m away from my keyboard right now, but when I get back to my desk I’ll calendar prune and send you some free times.”

Finally I was like “what the hell, are you sending me whole auto-generated emails”? To which he replied “of course.”

Chris posted the code to his introduction script last week so now I have proof that some of my favorite emails I thought were from him back in 2011 were actually from tcsh.

Feeling cheated, I called him to tell him he has an addiction to shell scripting. Here’s a brief interview, rewritten to make me sound smarter and cooler than I am.

——

CO: Ok, let’s start with these iphone shortcuts. Sometimes the whole email from you reads like a bunch of shortcuts.

CW: Yup, lots of times.

CO: What the hell? Don’t you want to personalize things for me at least a little?

CW: I do! But I also want to catch the subway.

CO: Ugh. How many shortcuts do you have on that thing?

CW: Well.. (pause)..38.

CO: Ok now I’m officially worried about you. What’s the longest one?

CW: Probably this one I wrote for Sandy: If I write “sandy” it unpacks to

“Sorry for delay and brevity in reply. Sandy knocked out my phone, power, water, and internet so I won’t be replying as quickly as usual. Please do not hesitate to email me again if I don’t reply soon.”

CO: You officially have a problem. What’s the shortest one?

CW: Well, when I type “plu” it becomes “+1”

CO: Ok, let me apply the math for you: your shortcut is longer than your longcut.

CW: I know but not if you include switching from letters to numbers on the iphone, which is annoying.

CO: How did you first become addicted to shortcuts?

CW: I got introduced to UNIX in the 80s and, in my frame of reference at the time, the closest I had come to meeting a wizard was the university’s sysadmin. I was constantly breaking things by chomping cpu with undead processes or removing my $HOME or something, and he had to come in and fix things. I learned a lot over his shoulder. In the summer before I started college, my dream was to be a university sysadmin. He had to explain to me patiently that I shouldn’t spend college in a computercave.

CO: Good advice, but now that you’re a grownup you can do that.

CW: Exactly. Anyway, everytime he would fix whatever incredible mess I had made he would sign off with some different flair and walk out, like he was dropping the mic and walking off stage. He never signed out “logout” it was always “die” or “leave” or “ciao” (I didn’t know that word at the time). So of course by the time he got back to his desk one day there was an email from me asking how to do this and he replied:

“RTFM. alias”

CO: That seems like kind of a mean thing to do to you at such a young age.

CW: It’s true. UNIX alias was clearly the gateway drug that led me to writing shell scripts for everything.

CO: How many aliases do you have now?

CW: According to “alias | wc -l “, I have 1137. So far.

CO: So you’ve spent countless hours making aliases to save time.

CW: Yes! And shell scripts!

CO: Ok let’s talk about this script for introducing me to people. As you know I don’t like getting treated like a small cog. I’m kind of a big deal.

CW: Yes, you’ve mentioned that.

CO: So how does it work?

CW: I have separate biography files for everyone, and a file called nfile.asc that has first name, lastname@tag, and email address. Then I can introduce people via

% ii oneil@mathbabe schutt

It strips out the @mathbabe part (so I can keep track of multiple people named oneil) from the actual email, reads in and reformats the biographies, grepping out the commented lines, and writes an email I can pipe to mutt. The whole thing can be done in a few seconds.

CO: Ok that does sound pretty good. How many shell scripts do you have?

CW: Hundreds. A few of them are in my public mise-en-place repository, which I should update more. I’m not sure which of them I really use all the time, but it’s pretty rare I type an actual legal UNIX command at the command line. That said I try never to leave the command line. Students are always teaching me fancypants tricks for their browsers or some new app, but I spend a lot of time at the command line getting and munging data, and for that, sed, awk, and grep are here to stay.

CO: That’s kinda sad and yet… so true. Ok here’s the only question I really wanted to ask though: will you promise me you’ll never send me any more auto-generated emails?

CW: no.

War of the machines, college edition

A couple of people have sent me this recent essay (hat tip Leon Kautsky) written by Elijah Mayfield on the education technology blog e-Literate, described on their About page as “a hobby weblog about educational technology and related topics that is maintained by Michael Feldstein and written by Michael and some of his trusted colleagues in the field of educational technology.”

Mayfield’s essay is entitled “Six Ways the edX Announcement Gets Automated Essay Grading Wrong”. He’s referring to the recent announcement, which was written about in the New York Times last week, about how professors will soon be replaced by computers in grading essays. He claims they got it all wrong and there’s nothing to worry about.

I wrote about this idea too, in this post, and he hasn’t addressed my complaints at all.

First, Mayfield’s points:

- Journalists sensationalize things.

- The machine is identifying things in the essays that are associated with good writing vs. bad writing, much like it might learn to distinguish pictures of ducks from pictures of houses.

- It’s actually not that hard to find the duck and has nothing to do with “creativity” (look for webbed feet).

- If the machine isn’t sure it can spit back the essay to the professor to read (if the professor is still employed).

- The machine doesn’t necessarily reward big vocabulary words, except when it does.

- You’d need thousands of training examples (essays on a given subject) to make this actually work.

- What’s so really wonderful is that a student can get all his or her many drafts graded instantaneously, which no professor would be willing to do.

Here’s where I’ll start, with this excerpt from near the end:

“Can machine learning grade essays?” is a bad question. We know, statistically, that the algorithms we’ve trained work just as well as teachers for churning out a score on a 5-point scale. We know that occasionally it’ll make mistakes; however, more often than not, what the algorithms learn to do are reproduce the already questionable behavior of humans. If we’re relying on machine learning solely to automate the process of grading, to make it faster and cheaper and enable access, then sure. We can do that.

OK, so we know that the machine can grade essays written for human consumption pretty accurately. But it hasn’t had to deal with essays written for machine consumption yet. There’s major room for gaming here, and only a matter of time before there’s a competing algorithm to build a great essay. I even know how to train that algorithm. Email me privately and we can make a deal on profit-sharing.

And considering that students will be able to get their drafts graded as many times as they want, as Mayfield advertised, this will only be easier. If I build an essay that I think should game the machine, by putting in lots of (relevant) long vocabulary words and erudite phrases, then I can always double check by having the system give me a grade. If it doesn’t work, I’ll try again.

And the essays built this way won’t get caught via the fraud detection software that finds plagiarism, because any good essay-builder will only steal smallish phrases.

One final point. The fact that the machine-learning grading algorithm only works when it’s been trained on thousands of essays points to yet another depressing trend: large-scale classes with the same exact assignments every semester so last year’s algorithm can be used, in the name of efficiency.

But that means last year’s essay-building algorithm can be used as well. Pretty soon it will just be a war of the machines.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

A couple of sad updates on Aunt Pythia.

First, someone hacked my Aunt Pythia spreadsheet and added hundreds of bizarre and offensive questions (at least they seemed intended to offend, but luckily Aunt Pythia doesn’t offend easily), which I then erased in huge blocks. This means if you actually had a valid question in the last week it has been, sadly, removed.

Second, possibly because of all the removed stuff, Aunt Pythia has no smutty sex questions to answer and has resorted to answering sober and serious leftover questions. But don’t fear! Aunt Pythia will do her best to sex up the answers anyway.

If you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Please submit your smutty sex (or otherwise) questions at the bottom of this column!

——

Aunt Pythia,

What do you think of Sheryl Sandberg and Malissa Mayer as role models/advice givers to young women? I ask you because I am confident you will give a measured response, not the reflexively pro or reflexively con reactions they seem to get.

Female enduring mostly masculine explanations

Dear Femme,

I’m going to preface my remarks by admitting I still haven’t read Sandberg’s book. But I have read enough reviews to get a feeling for what she’s going for. I have a bunch of comments:

- Do women sometimes undermine themselves by not going for things whole-heartedly and holding back? Yes, yes they do. So do men, of course. There are lots of people in this world who have missed opportunities by not giving things a real chance. Maybe this happens more often for women – I’d not be too surprised to hear that (but I also think I have an explanation, see below).

- On the other hand, I fundamentally question how bad we should feel when highly educated women choose not to try for a promotion that will require them to travel half the time and work 80 hours a week. Why would someone want that lifestyle? Why would that be their route to happiness? This is a death bed consideration, and if you ask me I’d rather not have death bed regrets about missing out on all of my personal interests, hobbies, adventures, friends, and family because I was so sure that promotion was important.

- In fact, I think highly educated women like Mayer and Sandberg, and myself for that matter, are luckier than the men they compete with. The truth is women actually have more options than men because society’s expectations are so much narrower for men. Want to leave the corporate scene after your second kid and start writing children’s books? Ok fine. That would be really weird for a man to do.

- In fact, where are the academic papers which assume that women leave the rat race by choice, to maximize their utility functions? Why don’t we assume that women have different options than men and that the fact that only 15% of women run large companies is a result of most qualified women deciding “I’d rather not, thank you”? I’m not saying that’s the only underlying effect but I honestly think it’s part of it. Plus, if we looked at it that way then the culture inside the corporation could be analysed a bit more, and we might start to understand what’s so unappealing about it. If we made it more appealing to women, they might decide to stay longer.

- Or for that matter, that women have different utility functions altogether, and that they leave the rat-race or stay in a job which doesn’t require 80 hours a week because they are (locally) maximizing their utility?

- It wouldn’t surprise me, if such a study were done, to figure out that (highly educated) women are actually happier than (highly educated) men in general, at least the women who have quality daycare.

In other words, I get some of their advice but I question their narrow perspective and narrow definition of success.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m almost finished with my masters in pure math. But now I’m doubting about becoming a high school teacher or do something in companies. I like children and I dislike most aspects of corporate culture, but the burn out rate for teachers is very high. Can you give me pros and cons about either career path?

Doubting

Dear D,

It’s a tough time for teachers out there. Read this resignation letter (h/t Chris Wiggins) if you haven’t already. An excerpt:

With regard to my profession, I have truly attempted to live John Dewey’s famous quotation (now likely cliché with me, I’ve used it so very often) that “Education is not preparation for life, education is life itself.” This type of total immersion is what I have always referred to as teaching “heavy,” working hard, spending time, researching, attending to details and never feeling satisfied that I knew enough on any topic. I now find that this approach to my profession is not only devalued, but denigrated and perhaps, in some quarters despised. STEM rules the day and “data driven” education seeks only conformity, standardization, testing and a zombie-like adherence to the shallow and generic Common Core, along with a lockstep of oversimplified so-called Essential Learnings. Creativity, academic freedom, teacher autonomy, experimentation and innovation are being stifled in a misguided effort to fix what is not broken in our system of public education and particularly not at Westhill.

On the other hand, there’s definitely a severe need for good math teachers. So I don’t want to utterly discourage you. One possibility is to try out teaching for a couple of years and then decide whether to stick with it or not (although the learning curve for teaching is steep, so keep in mind it gets easier over time). Have you talked to people at Math for America?

Also, do some research about where you want to teach, and make sure you land in a school which values their teachers and gives lots of clear feedback and doesn’t just submit blindly to the testing borg. Talk to the principal about that stuff beforehand.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt P,

My wife and I have been enjoying a politico/sci-fi drama called Continuum, which features model and actress Rachel Nichols, a Columbia University grad with a double major in math and economics. What’s more, the show has serious undertones implying the Occupy movement is spot-on. Now I have this fantasy of a series of action movies centered around a demure blogger by day and a sexy fighter for the people by night who uses her succubi powers to enervate and destroy evil banksters. Isn’t this something we should get on Kickstarter right away?

Distinguished Opinion Maker

Dear DOM,

I haven’t seen the show, but I dig the idea of a superhero blogger, bien sûr!

Just one quibble about the use of “succubi” though:

succubi plural of suc·cu·bus

|

Noun

|

Are you suggesting that the main character flies around at night sleeping with banksters for the good of society (note I threw in the ability to fly because that’s what awesome superheroes do)? I’m a bit confused on that point, because I don’t think it makes for good TV. Not to mention I’m not sure how that shows the banksters the error of their ways. Here’s the image I found when I google image searched “banksters”:

I mean they’re healthy enough but I’m not sure they’re porn star material. It’s all about taste though. Whatever floats your boat.

Tell me if and when you’ve started the Kickstarter campaign, please! I want to keep tabs on how much money people will contribute towards this fetching concept.

Auntie P

——

Aunt Pythia,

I’m defending my dissertation soon! Woohoo! I’m curious to know what Aunt Pythia thinks about the following things: (a) board vs. slide talk, (b) how to pitch a talk about your research to mathematicians who aren’t specialists in your field, and (c) what to wear. It seems to me like (c) can’t possibly be separated from the issue of gender, so let’s pretend I’m female. (The underlying question is: how do I impress a room full of people in 40 minutes without spewing jargon or dressing like PhD Barbie?)

Nervous in Nebraska

Dear NiN,

This one’s easy. The answer is that it doesn’t matter one bit because we all know this is a formality and you’re all done! You’re getting your degree! YEAH!! Congratulations.

If I were you I’d wear something bright and celebratory, like the peacock you must feel yourself to be. And I’d say slide so you don’t get your bright clothes chalky.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please please please submit questions!

A public-facing math panel

I’m returning from two full days of talking to mathematicians and applied mathematicians at Cornell. I was really impressed with the people I met there – thoughtful, informed, and inquisitive – and with the kind reception they gave me.

I gave an “Oliver Talk” which was joint with the applied math colloquium on Thursday afternoon. The goal of my talk was to convince mathematicians that there’s a very bad movement underway whereby models are being used against people, in predatory ways, and in the name of mathematics. I turned some people off, I think, by my vehemence, but then again it’s hard not get riled up about this stuff, because it’s creepy and I actually think there’s a huge amount at stake.

One thing I did near the end of my talk was bring up (and recruit for) the idea of a panel of mathematicians which defines standards for public-facing models and vets the current crop.

The first goal of such a panel would be to define mathematical models, with a description of “best practices” when modeling people, including things like anticipating impact, gaming, and feedback loops of models, and asking for transparent and ongoing evaluation methods, as well as having minimum standards for accuracy.

The second goal of the panel would be to choose specific models that are in use and measure the extent to which they pass the standards of the above best practices rubric.

So the teacher value-added model, I’d expect, would fail in that it doesn’t have an evaluation method, at least that is made public, nor does it seem to have any accuracy standards, even though it’s widely used and is high impact.

I’ve had some pretty amazing mathematicians already volunteer to be on such a panel, which is encouraging. What’s cool is that I think mathematicians, as a group, are really quite ethical and can probably make their voices heard and trusted if they set their minds to it.

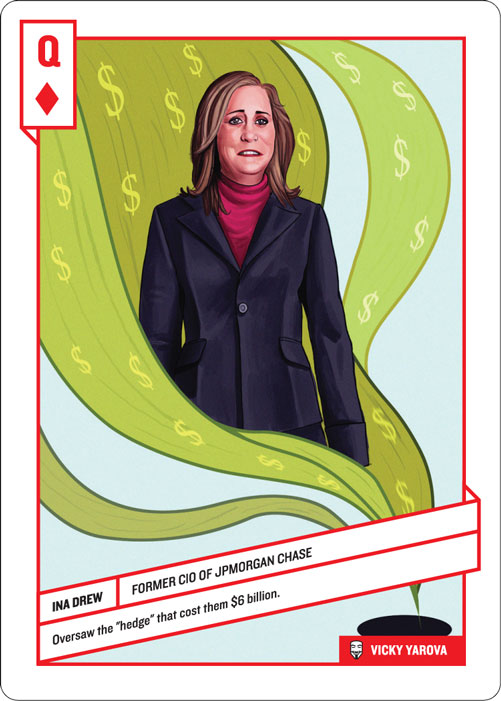

Ina Drew: heinously greedy or heinously incompetent?

Last night I went to an event at Barnard where Ina Drew, ex-CIO head of JP Morgan Chase, who oversaw the London Whale fiasco, was warmly hosted and interviewed by Barnard president Debora Spar.

[Aside: I was going to link to Ina Drew’s wikipedia entry in the above paragraph, but it was so sanitized that I couldn’t get myself to do it. She must have paid off lots of wiki editors to keep herself this clean. WTF, wikipedia??]

A little background in case you don’t know who this Drew woman is. She was in charge of balance-sheet risk management and somehow managed to not notice losing $6.2 billion dollars in the group she was in charge of, which was meant to hedge risk, at least according to CEO Jamie Dimon. She made $15 million per year for her efforts and recently retired.

In her recent Congressional testimony (see Example 3 in this recent post), she threw the quants with their Ph.D.’s under the bus even though the Senate report of the incident noted multiple risk limits being exceeded and ignored, and then risk models themselves changed to look better, as well as the “whale” trader Bruno Iksil‘s desire to get out of his losing position being resisted by upper management (i.e. Ina Drew).

I’m not going to defend Iksil for that long, but let’s be clear: he fucked up, and then was kept in his ridiculous position by Ina Drew because she didn’t want to look bad. His angst is well-documented in the Senate report, which you should read.

Actually, the whole story is somewhat more complicated but still totally stupid: instead of backing out of certain credit positions the old-fashioned and somewhat expensive way, the CIO office decided to try to reduce its capital requirements via reducing (manipulated) VaR, but ended up increasing their capital requirements in other, non-VaR ways (specifically, the “comprehensive risk measure”, which isn’t as manipulable as VaR). Read more here.

Maybe Ina is going to claim innocence, that she had no idea what was going on. In that case, she had no control over her group and its huge losses. So either she’s heinously greedy or heinously incompetent. My money’s on “incompetent” after seeing and listening to her last night. My live Twitter feed from the event is available here.

We featured Ina Drew on our “52 Shades of Greed” card deck as the Queen of diamonds:

Back to the event.

Why did we cart out Ina Drew in front of an audience of young Barnard women last night? Were we advertising a career in finance to them? Is Drew a role model for these young people?

The best answers I can come up with are terrible:

- She’s a Barnard mom (her daughter was in the audience). Not a trivial consideration, especially considering the potential donor angle.

- President Spar is on the board of Goldman Sachs and there’s a certain loyalty among elites, which includes publicly celebrating colossal failures. Possible, but why now? Is there some kind of perverted female solidarity among women that should be in jail but insist on considering themselves role models? Please count me out of that flavor of feminism.

- President Spar and Ina Drew actually don’t think Drew did anything wrong. This last theory is the weirdest but is the best supported by the tone of the conversation last night. It gives me the creeps. In any case I can no longer imagine supporting Barnard’s mission with that woman as president. It’s sad considering my fond feelings for the place where I was an assistant professor for two years in the math department and which treated me well.

Please suggest other ideas I’ve failed to mention.

New creepy model: job hiring software

Warmup: Automatic Grading Models

Before I get to my main take-down of the morning, let me warm up with an appetizer of sorts: have you been hearing a lot about new models that automatically grade essays?

Does it strike you that’s there’s something wrong with that idea but you don’t know what it is?

Here’s my take. While it’s true that it’s possible to train a model to grade essays similarly to what a professor now does, that doesn’t mean we can introduce automatic grading – at least not if the students in question know that’s what we’re doing.

There’s a feedback loop, whereby if the students know their essays will be automatically graded, then they will change what they’re doing to optimize for good automatic grades rather than, say, a cogent argument.

For example, a student might download a grading app themselves (wouldn’t you?) and run their essay through the machine until it gets a great grade. Not enough long words? Put them in! No need to make sure the sentences make sense, because the machine doesn’t understand grammar!

This is, in fact, a great example where people need to take into account the (obvious when you think about them) feedback loops that their models will enter in actual use.

Job Hiring Models

Now on to the main course.

In this week’s Economist there is an essay about the new widely-used job hiring software and how awesome it is. It’s so efficient! It removes the biases of of those pesky recruiters! Here’s an excerpt from the article:

The problem with human-resource managers is that they are human. They have biases; they make mistakes. But with better tools, they can make better hiring decisions, say advocates of “big data”.

So far “the machine” has made observations such as:

- Good if candidate uses browser you need to download like Chrome.

- Not as bad as one might expect to have a criminal record.

- Neutral on job hopping.

- Great if you live nearby.

- Good if you are on Facebook.

- Bad if you’re on Facebook and every other social networking site as well.

Now, I’m all for learning to fight against our biases and hire people that might not otherwise be given a chance. But I’m not convinced that this will happen that often – the people using the software can always train the model to include their biases and then point to the machine and say “The machine told me to do it”. True.

What I really object to, however, is the accumulating amount of data that is being collected about everyone by models like this.

It’s one thing for an algorithm to take my CV in and note that I misspelled my alma mater, but it’s a different thing altogether to scour the web for my online profile trail (via Acxiom, for example), to look up my credit score, and maybe even to see my persistence score as measured by my past online education activities (soon available for your 7-year-old as well!).

As a modeler, I know how hungry the model can be. It will ask for all of this data and more. And it will mean that nothing you’ve ever done wrong, no fuck-up that you wish to forget, will ever be forgotten. You can no longer reinvent yourself.

Forget mobility, forget the American Dream, you and everyone else will be funneled into whatever job and whatever life the machine has deemed you worthy of. WTF.

Hey WSJ, don’t blame unemployed disabled people for the crap economy

This morning I’m being driven crazy by this article in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal entitled “Workers Stuck in Disability Stunt Economic Recovery.”

Even the title makes the underlying goal of the article crystal clear: the lazy disabled workers are to blame for the crap economy. Lest you are unconvinced that anyone could make such an unreasonable claim of causation, here’s a tasty excerpt from the article that spells it out:

Economic growth is driven by the number of workers in an economy and by their productivity. Put simply, fewer workers usually means less growth.

Since the recession, more people have gone on disability, on net, than new workers have joined the labor force. Mr. Feroli estimated the exodus to disability costs 0.6% of national output, equal to about $95 billion a year.

“The greater cost is their long-term dependency on transfers from the federal government,” Mr. Autor said, “placing strain on the soon-to-be exhausted Social Security Disability trust fund.”

The underlying model here, then, is that there’s a bunch of people who have the choice between going on disability or “joining the labor force” and they’ve all chosen to go on disability. I wonder where their evidence is that people really have that choice, considering the unemployment numbers and participation rate numbers we see nowadays.

For example, the unemployment rate for youths is now 22.9%, and the participation rate for them has gone from 59.2% in December 2007, to 54.5% today. This is probably not because so many kids under the age of 25 are disabled, I suspect. If you look at the overall labor participation rate, it’s dropped from 66.0 in December 2007 to 63.3 in March 2013. Most of the people who have left the work force are also not disabled. They’ve been discouraged for some other mysterious reason. I’m gonna go ahead and guess it’s because they can’t find a job.

This leads me to ask the following question from the journalists LESLIE SCISM and JON HILSENRATH who wrote the article: Where is your evidence of causation??

Here’s another example from the article of a seriously fucked-up understanding of cause and effect:

With overall participation down, the labor force—a measure of people working and people looking for work—is barely growing.

They consistently paint the picture whereby people decide to stop working, and then yucky things happen, in this case the labor force stops growing. Damn those lazy people.

They even bring in a fancy word from physics to describe the problem, namely hysteresis. Now, they didn’t understand or correctly define the term, but it doesn’t really matter, because the point of using a fancy term from physics was not to add to the clarity of the argument but rather to impress.

The goal here is, in fact, that if enough economists use sophisticated language to describe the various effects, we will all be able to blame people with bad backs, making $13.6K per year, on why our economy sucks, rather than the rich assholes in finance who got us into this mess and are currently buying $2 million dollar personal offices instead of going to jail.

Just to be clear, that’s $1,130 a month, which I guess represents so enticing a lifestyle that the people currently enjoying it ‘are “pretty unlikely to want to forfeit economic security for a precarious job market”‘ according to M.I.T. economist David Autor. I’d love to have David Autor spell out, for us, exactly what’s economically secure about that kind of monthly check.

The rest of the article is in large part a description of how people get onto SSDI, insinuating that the people currently on it are not really all that disabled or worthy of living high on the hog, and are in any case never ever leaving.

How’s this for a slightly different take on the situation: there are of course some people who are faking something, that’s always the case. But in general, the people on SSDI need to be there, and before the recession might have had the kind of employers who kept them on even though they often called in sick, out of loyalty and kindness, because they didn’t want to fire them. But when the recession struck those employers had to cut them off, or they went out of business completely. Now those people can’t find work and don’t have many options. In other words, the recession caused the SSDI program to grow. That doesn’t mean it caused a bunch of people to get sick, but it does mean that sick people are more dependent on SSDI because there are fewer options.

By the way, read the comments of this article, there are some really good ones (“What were people with injuries and no high-value job skills to do? Is the number of people in the social security disability program the problem or the symptom?”) as well as some really outrageous ones (‘The current situation makes the picture of the “Welfare Queen” of the 1980s look like an honest citizen’).

Tweenage angst, RSS feeds, and upcoming talks

Tweenage angst

Do you remember when you were just entering puberty, and absolutely everything was embarrassing? Even your mere existence twisted you in agony?

Well, I just brought my nearly-11-year-old and just-barely-13-year-old sons to their yearly checkups, and let me tell you, it’s painful to be within 10 feet of such exquisite awkwardness: how can you poke and prod this body to some universal understanding of science if I don’t even know its functions or potential grace? If I can’t even imagine it ever being graceful??

RSS feeds

I deleted a post (“Papers I’ve been reading lately”) which had some offending unknown characters that WordPress couldn’t handle, and most people can now read mathbabe again on their readers, except for some reason for people who read mathbabe via WordPress itself. My advice to those people: start using some other reader. Maybe feedly?

Upcoming talks

I’m giving three talks in the next two weeks.

- The first one is this Thursday at the Cornell math department, where I’m once again talking about Weapons of Math Destruction.

- The second one is in Emanuel Derman’s Financial Engineering Practitioner’s Seminar next Monday at Columbia, where I’ll talk about recommendation systems and MapReduce, taking material from Doing Data Science, specifically the chapters contributed by Matt Gattis and David Crawshaw.

- Finally, I’ll be giving the NYC Machine Learning Meetup next Thursday. The announcement of this

is going to be posted some time later this morningis now up, and the content will be similar to the Columbia talk.

Elizabeth Fischer talks about climate modeling at Occupy today

I’m really excited to be going to the pre-meeting talk of my Occupy group today. We’re having a talk by Elizabeth Fischer, who is a post-doc at NASA GISS, a laboratory focused largely on climate change up here in the Columbia neighborhood.

She is coming to talk with us about her work investigating the long-term behavior of ice sheets in a changing climate. Before joining GISS, Dr. Fischer was a quant on Wall Street, working on statistical arbitrage, trade execution, simulation/modeling platforms, signal development, and options trading. I met her when we were both students at math camp in 1988, but we reconnected this past summer at the reunion.

The actual title of her talk is “The History of CO2: Past, Present and Future” and it’s open to the public, so please come if you can (it’s at 2:00 pm in room 409 here but more details are here).

After Elizabeth, we’ll be having our usual Occupy meeting. Topics this week include our plans for a Citigroup and HSBC picket later this month, our panel submissions to the Left Forum in June, our plans for May Day, and continued work on writing a book modeled after the Debt Resistor’s Operations Manual.

Housekeeping – RSS feed for mathbabe broken, possibly fixed

I’ve been trying to address the problem people have been having with their RSS feed for mathbabe. Thanks to my nerd-girl friend Jennifer Rubinovitz, I’ve changed some settings in my WordPress settings and now I can view all of my posts when I open up RSSOwl. But in order for your reader to get caught up I have a feeling you’ll need to somehow refresh it or maybe get rid of mathbabe and then re-subscribe. I’ll update as I learn more (please tell me what’s working for you!).

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is excited to discuss the following topics today: sex with students, how to get men to stop trivializing women near you, and how to feel attractive.

Did you expect and hope for something less titillating? Then please unsubscribe from my RSS feed immediately (speaking of which, can someone help me give advice to people getting bumped off of Google Reader? How do you get your daily dose of mathbabe? Please comment below).

If you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Please submit your smutty sex questions at the bottom of this column!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I teach online using a chat-based tutoring system, which creates some interesting situations. I get a lot of comments from students like, “hey, you’re hot, let’s hookup tonite.” I don’t take them up on those requests for many reasons, including

- I don’t want to get fired,

- I don’t want to go to jail,

- I’m in a happily committed relationship,

- I don’t get paid enough to make last minute cross-country flights,

- I already have enough people and activities vying for my spare time.

I usually just write boring stuff like “please focus on your lesson” or “sorry, I’m not allowed to do that.” But, just for fun, and assuming the students were of legal age, etc, what does a math-babe say when a student asks to hook up or hang out, whether virtually or face-to-face?

Might Actually Teach Humans

Dear MATH,

From your concerns about going to jail, which seem to be alleviated in the scenario where the student is old enough, I’m going to assume you tutor high school students as well as older students. If this is the case, then let me congratulate you on making the wise decision to avoid such opportunities. High school students are best left to each other, with a bunch of well-meaning advice, a few copies of “Our Bodies, Ourselves,” and boxes and boxes of condoms.

For that matter, the same could be said about college-age students. Leave those guys alone too, they’re still developing.

With that, I’ll assume that you and the student in question are both grownups, i.e. about 23 or older. And for the sake of this question I’ll assume that you’re not a college professor teaching grad students, since I don’t want to become an expert on the nationwide norms of professorial conduct this morning.

Even so, if you are formally teaching a student in any capacity, and thus responsible for their grade and/or feedback, then I’d certainly expect you to avoid expressing romantic or sexual interest in your student until after the grades are turned in, lest it be construed as creepy pressure for a good grade. But even then it might not be ok – what if you might someday write them a letter of recommendation? In that case a romantic relationship would make that extremely difficult. I’d say that the formal relationship of teacher-student pretty much rules out sex for quite a while. I’m not saying it never happens, obviously, but it’s best to avoid.

Now, to your situation: you’re a tutor. You’re a grownup. The students you teach are grownups. There’s presumably no grade given by a tutor, and considering it’s chat-based and online, there might be an army of tutors that the student can turn to if they decide you’re bad in bad (true? about the army, not about you being bad in bed). I really don’t see a problem here.

That’s not a green flag to start flirting with all of your students, that would be creepy and weird and could easily get you fired. Don’t be creepy.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have a history of my male friends talking to me about women they are dating in a way that makes me feel unattractive. I can think of (at least) two things that contribute to my feeling unattractive:

- I assume if they thought I was attractive, they wouldn’t talk to me about other women.

- They talk about other women in simplifying terms that seems to reduce women down to a few dimensions of attractiveness (skinny, high heels, dumb, girly and deferential), and I don’t fit into the space they’ve defined.

What do I do to make this stop?

Feeling Unattractive, Chasing Knowledge

Dear FUCK,

Sounds like you hang out with a bunch of dudes who have forgotten the golden rule of PUA’s (Pick-Up Artists), namely don’t share the secrets!!

Just kidding – PUA’s love sharing their secrets, because it gives them yet another chance to brag about their conquests.

I’m really glad you wrote. It pisses me off when the nasty way a given man thinks about women and sex leaks onto other people. Especially because this trivializing posture towards women is actually an silly act of self-defense and insecurity on the part of the man you’re hanging out with. It’s not enough that they feel insecure, they’ve got to make everyone around them that way too. Lame.

By the way, I’m not at all sure that, if a man starts talking about sex with other women around you, that’s he’s not also interested in you. It might be his awkward, awful way of expressing interest. But that doesn’t mean it’s meant to make you feel attractive. It sounds like one of his ways of getting laid is by making women feel unattractive and trivial. It might even be a script he wishes you to follow. Not cool.

Here are some options you have:

- Next time you’re in the conversation with him, you might anticipate his modus operandi and start talking about sexual attraction before he does. You could, for example, talk about attributes you honestly like in men like, say, the strength of ego not to trivialize women.

- Another possibility is you could talk to him directly about this issue (assuming he’s an important enough friend of yours that you’re willing to go there). Tell him that, when he trivializes women around you, it makes you feel unattractive, and you’re pretty sure that it’s unintentional but in any case you’re wondering why he does it. You might want to ask him how he’d feel if you did the same thing in terms of men.

- Another possibility is you could just up and tell him you don’t want to hear about his conquests.

- Finally, you could just find other men to hang out with who have figured out honest and direct ways to deal with women. Maybe because they’re not from an English-speaking country.

Good luck!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I walk around society feeling unattractive and I don’t know what signals to look for in my interactions with other people that they think I am attractive. I’m not looking for Glamour Magazine kind of advice. But Aunt Pythia kind of advice. How do I know if other people find me attractive? I assume for the most part they don’t.

Feeling Unattractive, Chasing Knowledge, I Need Guidance

Dear FUCKING,

Good questions this week! I’ve come up with an idea which I hope will help.

Namely, I think one of the main ways women get feedback about their attractiveness is through other women. For whatever reasons (some of them no doubt reasonable, some of them not), our culture deems it inappropriate for men to go up to women with direct feedback on their attractiveness. But girlfriends can play this role, especially if you ask them to.

So my first piece of advice is, if you’re looking for feedback and advice on your attractiveness, go ask your girlfriends.

That’s not to say all girlfriends are created equal. There are some girlfriends that are competitive and jealous of their friends, and will give you weird advice that makes you think you need to be skinny, high heeled, dumb, girly and deferential to be attractive, kinda like the douchey man you talked to above. These bad girlfriends, by the way, are also the women who write the advice tips for Glamour Magazine. It’s a bad sign if they tell you about a great diet they heard of.

The kind of girlfriend you’re looking for is the kind that, when you express ambivalence about your attractiveness, instantly proclaims you hot as hell and offers to take you out shopping for clothes that show off your boobs (or some other body part of which you’re particularly proud). Or better yet, whips out the nearest catalog and goes through it page-by-page with you, showing you what to look for that will flatter your incredible body.

Good luck finding yourself some awesome girlfriends!

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please please please submit questions!

Guest post by Julia Evans: How I got a data science job

This is a guest post by Julia Evans. Julia is a data scientist & programmer who lives in Montréal. She spends her free time these days playing with data and running events for women who program or want to — she just started a Montréal chapter of pyladies to teach programming, and co-organize a monthly meetup called Montréal All-Girl Hack Night for women who are developers.

I asked mathbabe a question a few weeks ago saying that I’d recently started a data science job without having too much experience with statistics, and she asked me to write something about how I got the job. Needless to say I’m pretty honoured to be a guest blogger here 🙂 Hopefully this will help someone!

Last March I decided that I wanted a job playing with data, since I’d been playing with datasets in my spare time for a while and I really liked it. I had a BSc in pure math, a MSc in theoretical computer science and about 6 months of work experience as a programmer developing websites. I’d taken one machine learning class and zero statistics classes.

In October, I left my web development job with some savings and no immediate plans to find a new job. I was thinking about doing freelance web development. Two weeks later, someone posted a job posting to my department mailing list looking for a “Junior Data Scientist”. I wrote back and said basically “I have a really strong math background and am a pretty good programmer”. This email included, embarrassingly, the sentence “I am amazing at math”. They said they’d like to interview me.

The interview was a lunch meeting. I found out that the company (Via Science) was opening a new office in my city, and was looking for people to be the first employees at the new office. They work with clients to make predictions based on their data.

My interviewer (now my manager) asked me about my role at my previous job (a little bit of everything — programming, system administration, etc.), my math background (lots of pure math, but no stats), and my experience with machine learning (one class, and drawing some graphs for fun). I was asked how I’d approach a digit recognition problem and I said “well, I’d see what people do to solve problems like that, and I’d try that”.

I also talked about some data visualizations I’d worked on for fun. They were looking for someone who could take on new datasets and be independent and proactive about creating model, figuring out what is the most useful thing to model, and getting more information from clients.

I got a call back about a week after the lunch interview saying that they’d like to hire me. We talked a bit more about the work culture, starting dates, and salary, and then I accepted the offer.

So far I’ve been working here for about four months. I work with a machine learning system developed inside the company (there’s a paper about it here). I’ve spent most of my time working on code to interface with this system and make it easier for us to get results out of it quickly. I alternate between working on this system (using Java) and using Python (with the fabulous IPython Notebook) to quickly draw graphs and make models with scikit-learn to compare our results.

I like that I have real-world data (sometimes, lots of it!) where there’s not always a clear question or direction to go in. I get to spend time figuring out the relevant features of the data or what kinds of things we should be trying to model. I’m beginning to understand what people say about data-wrangling taking up most of their time. I’m learning some statistics, and we have a weekly Friday seminar series where we take turns talking about something we’ve learned in the last few weeks or introducing a piece of math that we want to use.

Overall I’m really happy to have a job where I get data and have to figure out what direction to take it in, and I’m learning a lot.

K-Nearest Neighbors: dangerously simple

I spend my time at work nowadays thinking about how to start a company in data science. Since there are tons of companies now collecting tons of data, and they don’t know what do to do with it, nor who to ask, part of me wants to design (yet another) dumbed-down “analytics platform” so that business people can import their data onto the platform, and then perform simple algorithms themselves, without even having a data scientist to supervise.

After all, a good data scientist is hard to find. Sometimes you don’t even know if you want to invest in this whole big data thing, you’re not sure the data you’re collecting is all that great or whether the whole thing is just a bunch of hype. It’s tempting to bypass professional data scientists altogether and try to replace them with software.

I’m here to say, it’s not clear that’s possible. Even the simplest algorithm, like k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN), can be naively misused by someone who doesn’t understand it well. Let me explain.

Say you have a bunch of data points, maybe corresponding to users on your website. They have a bunch of attributes, and you want to categorize them based on their attributes. For example, they might be customers that have spent various amounts of money on your product, and you can put them into “big spender”, “medium spender”, “small spender”, and “will never buy anything” categories.

What you really want, of course, is a way of anticipating the category of a new user before they’ve bought anything, based on what you know about them when they arrive, namely their attributes. So the problem is, given a user’s attributes, what’s your best guess for that user’s category?

Let’s use k-Nearest Neighbors. Let k be 5 and say there’s a new customer named Monica. Then the algorithm searches for the 5 customers closest to Monica, i.e. most similar to Monica in terms of attributes, and sees what categories those 5 customers were in. If 4 of them were “medium spenders” and 1 was “small spender”, then your best guess for Monica is “medium spender”.

Holy shit, that was simple! Mathbabe, what’s your problem?

The devil is all in the detail of what you mean by close. And to make things trickier, as in easier to be deceptively easy, there are default choices you could make (and which you would make) which would probably be totally stupid. Namely, the raw numbers, and Euclidean distance.

So, for example, say your customer attributes were: age, salary, and number of previous visits to your website. Don’t ask me how you know your customer’s salary, maybe you bought info from Acxiom.

So in terms of attribute vectors, Monica’s might look like:

And the nearest neighbor to Monica might look like:

In other words, because you’re including the raw salary numbers, you are thinking of Monica, who is 22 and new to the site, as close to a 75-year old who comes to the site a lot. The salary, being of a much larger scale, is totally dominating the distance calculation. You might as well have only that one attribute and scrap the others.

Note: you would not necessarily think about this problem if you were just pressing a big button on a dashboard called “k-NN me!”

Of course, it gets trickier. Even if you measured salary in thousands (so Monica would now be given the attribution vector ) you still don’t know if that’s the right scaling. In fact, if you think about it, the algorithm’s results completely depends on how you scale these numbers, and there’s almost no way to reasonably visualize it even, to do it by hand, if you have more than 4 attributes.

Another problem is redundancy – if you have a bunch of attributes that are essentially redundant, i.e. that are highly correlated to each other, then including them all is tantamount to multiplying the scale of that factor.

Another problem is not all your attributes are even numbers, so you have string attributes. You might think you can solve this by using 0’s and 1’s, but in the case of k-NN, that becomes just another scaling problem.

One way around this might be to first use some kind of dimension-reducing algorithm, like PCA, to figure out what attribute combinations to actually use from the get-go. That’s probably what I’d do.

But that means you’re using a fancy algorithm in order to use a completely stupid algorithm. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it indicates the basic problem, which is that doing data analysis carefully is actually pretty hard and maybe should be done by professionals, or at least under the supervision of a one.

We don’t need more complicated models, we need to stop lying with our models

The financial crisis has given rise to a series of catastrophes related to mathematical modeling.

Time after time you hear people speaking in baffled terms about mathematical models that somehow didn’t warn us in time, that were too complicated to understand, and so on. If you have somehow missed such public displays of throwing the model (and quants) under the bus, stay tuned below for examples.

A common response to these problems is to call for those models to be revamped, to add features that will cover previously unforeseen issues, and generally speaking, to make them more complex.

For a person like myself, who gets paid to “fix the model,” it’s tempting to do just that, to assume the role of the hero who is going to set everything right with a few brilliant ideas and some excellent training data.

Unfortunately, reality is staring me in the face, and it’s telling me that we don’t need more complicated models.

If I go to the trouble of fixing up a model, say by adding counterparty risk considerations, then I’m implicitly assuming the problem with the existing models is that they’re being used honestly but aren’t mathematically up to the task.

But this is far from the case – most of the really enormous failures of models are explained by people lying. Before I give three examples of “big models failing because someone is lying” phenomenon, let me add one more important thing.

Namely, if we replace okay models with more complicated models, as many people are suggesting we do, without first addressing the lying problem, it will only allow people to lie even more. This is because the complexity of a model itself is an obstacle to understanding its results, and more complex models allow more manipulation.

Example 1: Municipal Debt Models

Many municipalities are in shit tons of problems with their muni debt. This is in part because of the big banks taking advantage of them, but it’s also in part because they often lie with models.

Specifically, they know what their obligations for pensions and school systems will be in the next few years, and in order to pay for all that, they use a model which estimates how well their savings will pay off in the market, or however they’ve invested their money. But they use vastly over-exaggerated numbers in these models, because that way they can minimize the amount of money to put into the pool each year. The result is that pension pools are being systematically and vastly under-funded.

Example 2: Wealth Management

I used to work at Riskmetrics, where I saw first-hand how people lie with risk models. But that’s not the only thing I worked on. I also helped out building an analytical wealth management product. This software was sold to banks, and was used by professional “wealth managers” to help people (usually rich people, but not mega-rich people) plan for retirement.

We had a bunch of bells and whistles in the software to impress the clients – Monte Carlo simulations, fancy optimization tools, and more. But in the end, the banks and their wealth managers put in their own market assumptions when they used it. Specifically, they put in the forecast market growth for stocks, bonds, alternative investing, etc., as well as the assumed volatility of those categories and indeed the entire covariance matrix representing how correlated the market constituents are to each other.

The result is this: no matter how honest I would try to be with my modeling, I had no way of preventing the model from being misused and misleading to the clients. And it was indeed misused: wealth managers put in absolutely ridiculous assumptions of fantastic returns with vanishingly small risk.

Example 3: JP Morgan’s Whale Trade

I saved the best for last. JP Morgan’s actions around their $6.2 billion trading loss, the so-called “Whale Loss” was investigated recently by a Senate Subcommittee. This is an excerpt (page 14) from the resulting report, which is well worth reading in full:

While the bank claimed that the whale trade losses were due, in part, to a failure to have the right risk limits in place, the Subcommittee investigation showed that the five risk limits already in effect were all breached for sustained periods of time during the first quarter of 2012. Bank managers knew about the breaches, but allowed them to continue, lifted the limits, or altered the risk measures after being told that the risk results were “too conservative,” not “sensible,” or “garbage.” Previously undisclosed evidence also showed that CIO personnel deliberately tried to lower the CIO’s risk results and, as a result, lower its capital requirements, not by reducing its risky assets, but by manipulating the mathematical models used to calculate its VaR, CRM, and RWA results. Equally disturbing is evidence that the OCC was regularly informed of the risk limit breaches and was notified in advance of the CIO VaR model change projected to drop the CIO’s VaR results by 44%, yet raised no concerns at the time.

I don’t think there could be a better argument explaining why new risk limits and better VaR models won’t help JPM or any other large bank. The manipulation of existing models is what’s really going on.

Just to be clear on the models and modelers as scapegoats, even in the face of the above report, please take a look at minute 1:35:00 of the C-SPAN coverage of former CIO head Ina Drew’s testimony when she’s being grilled by Senator Carl Levin (hat tip Alan Lawhon, who also wrote about this issue here).

Ina Drew firmly shoves the quants under the bus, pretending to be surprised by the failures of the models even though, considering she’d been at JP Morgan for 30 years, she might know just a thing or two about how VaR can be manipulated. Why hasn’t Sarbanes-Oxley been used to put that woman in jail? She’s not even at JP Morgan anymore.

Stick around for a few minutes in the testimony after Levin’s done with Drew, because he’s on a roll and it’s awesome to watch.

Guest post: Divest from climate change

This is a guest post by Akhil Mathew, a junior studying mathematics at Harvard. He is also a blogger at Climbing Mount Bourbaki.

Climate change is one of those issues that I heard about as a kid, and I assumed naturally that scientists, political leaders, and the rest of the world would work together to solve it. Then I grew up and realized that never happened.

Carbon dioxide emissions are continuing to rise and extreme weather is becoming normal. Meanwhile, nobody in politics seems to want to act, even when major scientific organizations — and now the World Bank — have warned us in the strongest possible terms that the current path towards or more warming is an absolutely terrible idea (the World Bank called it “devastating”).

A little frustrated, I decided to show up last fall at my school’s umbrella environmental group to hear about the various programs. Intrigued by a curious-sounding divestment campaign, I went to the first meeting. I had zero knowledge of or experience with the climate movement, and did not realize what it was going to become.

Divestment from fossil fuel companies is a simple and brilliant idea, popularized by Bill McKibben’s article “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” As McKibben observes, there are numerous reasons to divest, both ethical and economic. The fossil fuel reserves of these companies — a determinant of their market value — are five(!) times what scientists estimate can be burned to stay within 2 degree warming.

Investing in fossil fuels is therefore a way of betting on climate change. It’s especially absurd for universities to invest in them, when much of the research on climate change took place there. The other side of divestment is symbolic. It’s not likely that Congress will be able to pass a cap-and-trade or carbon tax system anytime soon, especially when fossil fuel companies are among the biggest contributors to political campaigns.

A series of university divestments would draw attention to the problem. It would send a message to the world: that fossil fuel companies should be shunned, for basing their business model on climate change and then for lying about its dangers. This reason echoes the apartheid divestment campaigns of the 1980s. With support from McKibben’s organization 350.org, divestment took off last fall to become a real student movement, and today, over 300 American universities have active divestment campaigns from their students. Four universities — Unity College, Hampshire College, Sterling College, and College of the Atlantic — have already divested. Divestment is spreading both to Canadian universities and to other non-profit organizations. We’ve been covered in the New York Times, endorsed by Al Gore, and, on the other hand, recently featured in a couple of rants by Fox News.

Divest Harvard

At Harvard, we began our fall semester with a small group of us quietly collecting student petition signatures, mostly by waiting outside the dining halls, but occasionally by going door-to-door among dorms. It wasn’t really clear how many people supported us: we received a mix of enthusiasm, indifference, and occasional amusement from other students.

But after enough time, we made it to 1,000 petition signatures. That was enough to allow us to get a referendum on the student government ballot. The ballot is primarily used to elect student government leaders, but it was our campaign that rediscovered the use of referenda as a tool of student activism. (Following us, two other worthy campaigns — one on responsible investment more generally and one about sexual assault — also created their own referenda.)

After a week of postering and reaching out to student groups, our proposition—that Harvard should divest—won with 72% of the undergraduate student vote. That was a real turning point for us. On the one hand, having people vote on a referendum isn’t the same as engaging in the one-on-one conversations that we did when convincing people to sign our petition. On the other hand, the 72% showed that we had a real majority in support.

The statistic was quickly picked up by the media, since we were the first school to win a referendum on divestment (UNC has since had a winning referendum with 77% support). That was when the campaign took off. People began to take us seriously.

The Harvard administration, which had previously said that they had no intention of considering divestment, promised a serious, forty-five minute meeting with us. We didn’t get what we had aimed for — a private meeting with President Drew Faust — but we had acquired legitimacy from the administration. We were hopeful that we might be able to negotiate a compromise, and ended our campaign last fall satisfied, plotting the trajectory of our campaign at our final meeting.

The spring semester started with a flurry of additional activity and new challenges. On the one hand, we had to plan for the meeting with the administration—more precisely, the Corporation Committee on Social Responsibility. (The CCSR is the subgroup of the Harvard Corporation that decides on issues such as divestment.)

But we also knew that the fight couldn’t be won solely within the system. We had to work on building support on campus, from students and faculty, with rallies and speakers; we also had to reach out to alumni and let them know about our campaign. Fortunately, the publicity generated last semester had brought in a larger group of committed students, and we were able to split our organization into working groups to handle the greater responsibilities.

In Februrary, we got our promised meeting with three members the administration. With three representatives from our group meeting with the CCSR, we had a rally with about 40 people outside to show support:

In the meeting, the administration representatives reiterated their concern about climate change, but questioned divestment as a tool.

Unfortunately, since the meeting, they have continued to reiterate their “presumption against divestment” (a phrase they have used with previous movements). This is the debate we—and students across the nation—are going to have to win.

Divestment alone isn’t going to slow the melting of the Arctic, but it’s a powerful tool to draw attention to climate change and force action from our political system—as it did against apartheid in the 1980s.

And there isn’t much time left. One of the most inspirational things I’ve heard this semester was at the Forward on Climate rally in Washington, D.C. last month, which most of our group attended. Addressing a crowd of 40,000 people, Bill McKibben said “All I ever wanted to see was a movement of people to stop climate change, and now I’ve seen it.”

To me, that’s one of the exciting and hopeful aspects about divestment—that it’s a movement of the people. It’s fundamentally an issue of social justice that we’re facing, and our group’s challenge is to convince Harvard to take it seriously enough to stand up against the fossil fuel industry.

In the meantime, our campaign has been trying to build support from student groups, alumni, and faculty. In a surprise turnaround, one of our members convinced alumnus Al Gore to declare his support for the divestment movement at a recent event on campus. We organized a teach-in the Tuesday before last featuring writer and sociologist Juliet Schor.

On April 11, we will be holding a large rally outside Massachusetts Hall to close out the year and to show support for divestment; we’ll be presenting our petition signatures to the administration. Here’s our most recent picture, taken for the National Day of Action, with some supportive friends from the chess club:

Thanks to Joseph Lanzillo for proofreading a draft of this post.

Giving isn’t the secret

I don’t know if you read this article (h/t Radhika Sainath) on a hyperactive professor and Organizational Psychology researcher, Adam Grant, who always helps people when they ask and has a theory about giving. He claims that generous giving is the answer to getting ahead and feeling and being successful.

Well, as a “strategic giver” myself, let me tell you that giving isn’t the way to get ahead. Not as expressed by Grant, anyway*.

If you look carefully at the story, it reveals a bunch of things. Here are a few of them:

- Grant has a stay-at-home wife who deals with the kids all the time. Even so, she doesn’t seem all that psyched about how much time he devotes to helping other people (“Sometimes I tell him, ‘Adam — just say no,’ ”).

- He works all the time and misses sleep to get stuff done.

- He engages in high-profile strategic helping – he helps colleagues and students.

- Moreover, he does it in exaggerated and dramatic ways, leading to people talking about him and thanking him profusely, generally giving him attention.

- Considering that his area of research is how to get people to work hard and be more efficient through helping each other, this attention directly in line with his goal of gaining status.

- Just to be clear, he isn’t researching how to get other people to have high status like him, but rather how to get people to work harder in boring-ass jobs.

Put it all together, and you’ve got this disconnect between the way he applies “helping” to himself and to the subjects in his research.

He researches people in call centers, for example, and figures out how to get them to really believe in their work by seeing someone who benefitted from the associated scholarship program. But working harder doesn’t get them more status, it just makes them tired. The other examples in the article are similar. Actually some of them get grosser. Here’s a tasty excerpt from the article:

Jerry Davis, a management professor who taught Grant at the University of Michigan and is generally a fan of [Adam Grant]’s work, couldn’t help making a pointed critique about its inherent limits when they were on a panel together: “So you think those workers at the Apple factory in China would stop committing suicide if only we showed them someone who was incredibly happy with their iPhone?”

So what does he means by “giving” when he’s considering other people? Working really hard in a dead-end job? Kinda reminds me of this review of Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In” book, written by ex-Facebook disgruntled speech writer Kate Losse. Here’s my favorite line from that bitter essay:

For Sandberg, pregnancy must be converted into a corporate opportunity: a moment to convince a woman to commit further to her job. Human life as a competitor to work is the threat here, and it must be captured for corporate use, much in the way that Facebook treats users’ personal activities as a series of opportunities to fill out the Facebook-owned social graph.

In other words, Grant, like Sandberg, is selling us a message of working really hard with the underlying promise that it will make us successful, especially if we do it because we just love working really hard.

What?

First, it really matters what you work on and who you are helping. If you are not a strategic helper, you end up wasting your time for no good reason. How many times have we seen people who end up doing their job plus someone else’s job, without any thanks or extra money?

If you work really hard on a project which nobody cares about, nobody appreciates it. True.

And if you aren’t a political animal, able to smell out the projects and people that are worth working on extra hard and helping, then you’re pretty much out of luck.

But let’s take one step back from the terrible advice being given by Grant and Sandberg. What are their actual goals? Is it possible that they really think just by working extra hard at whatever shit corporate job we have will leave us successful and fulfilled? Are they that blind to other people’s options? Do they really know nobody in their private lives who found fulfillment by quitting their dead-end corporate job and became a poor but happy poet?

Here’s what Kate Losse says, and I think she hit the nail on the head:

Sandberg is betting that for some women, as for herself, the pursuit of corporate power is desirable, and that many women will ramp up their labor ever further in hopes that one day they, too, will be “in.” And whether or not those women make it, the companies they work for will profit by their unceasing labor.

Similarly, Grant’s personal academic success comes from getting people to work harder. His incentive is to get you to work harder, not be fulfilled. Just to be clear.

* I actually do think giving is a wonderful thing, but certainly not exclusively at work, and it’s not a secret.

Value-added model doesn’t find bad teachers, causes administrators to cheat

There’ve been a couple of articles in the past few days about teacher Value-Added Testing that have enraged me.

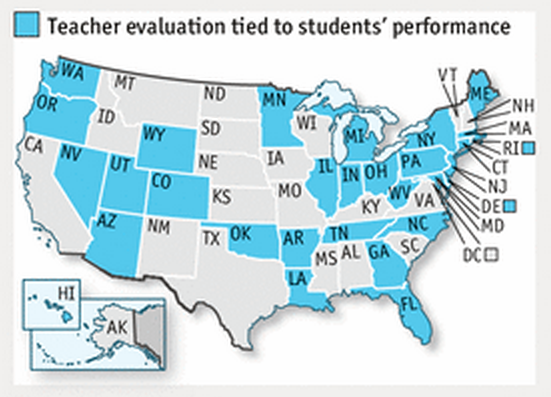

If you haven’t been paying attention, the Value-Added Model (VAM) is now being used in a majority of the states (source: the Economist):

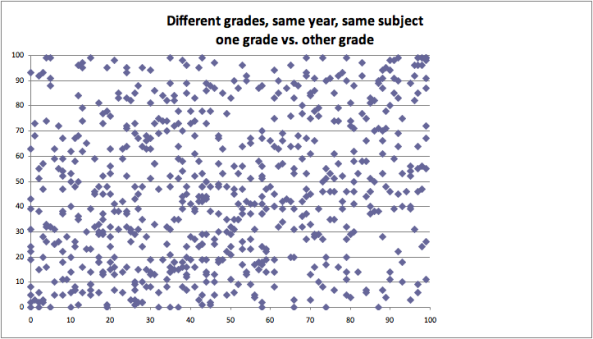

But it gives out nearly random numbers, as gleaned from looking at the same teachers with two scores (see this previous post). There’s a 24% correlation between the two numbers. Note that some people are awesome with respect to one score and complete shit on the other score:

Final thing you need to know about the model: nobody really understands how it works. It relies on error terms of an error-riddled model. It’s opaque, and no teacher can have their score explained to them in Plain English.

Now, with that background, let’s look into these articles.

First, there’s this New York Times article from yesterday, entitled “Curious Grade for Teachers: Nearly All Pass”. In this article, it describes how teachers are nowadays being judged using a (usually) 50/50 combination of classroom observations and VAM scores. This is different from the past, which was only based on classroom observations.