Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is super excited to have you on her nerd advice bus this morning.

And readers, you knew the time would come that Aunt Pythia would be saying this, but the time is now, peoples: we’re talking about female penes. I’m saving it for the end, but for those of you who are too impatient, you can go ahead and jump to the bottom of the page.

That is, as long as you remember to:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

De Blasio recently released his tax return, he had over 200K in income but paid only 8.3% in taxes. How does that work?

Guy who actually pays taxes in NYC

Dear Guy,

I’m no accountant but I suspect is has to do with “taking a loss” on the value of their home – which is pretty much a one-time accounting trick – as the article you provided described. Also, mortgage payments are tax deductible, which is a regressive tax and should be slowly phased out starting immediately.

By the way, if you’re getting all huffy about de Blasio, pardon me if I get much huffier about Bloomberg.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a female physics PhD student. A colleague once said to me that “If women want to be respected, they should not show cleavage.” What do you think?

Breasts of Oppression

Dear Breasts,

I’ve always thought quite the reverse. Namely, if men had boobs, they’d be showing them off all the time.

Different people can disagree about this, but my feeling is that cleavage is a kind of power, and some men and women find that threatening and/or distracting, and they don’t like feeling threatened or distracted so they make up nonsense about respectability (people in general don’t like to acknowledge threats).

That doesn’t mean women shouldn’t do use that power, it just means they should be aware of it and make sure they are in control of their power. I think it’s like men and muscles or height. You see tall men standing up to make a point and to use their height to their advantage. And you never hear a woman tell a man not to show off their height if they want to be respected. In fact, that sounds ridiculous.

My response to someone who said that would be to laugh in their face, honestly.

That’s not to say one can’t go too far. It’s not a linear, “cleavage is good so more cleavage is better” situation. At a certain point it can go too far, just as a man who wears muscle shirts and is constantly flexing his biceps in meetings – yes I’ve seen that happen – would be ridiculous.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Why can’t their be a different “shadow” banking system that’s only casting shadows because it’s out in broad day light and is transparent? Why can’t groups of ordinary people pool their money and lend it to each other at market rates via a community oriented savings bank? Did these types of banks ever exist? If not, shouldn’t we be able to create them today with all of our cleverness and technology?

RobFromAvon

Dear RobFromAvon,

First, it’s a great thought experiment. What are the obstacles to having a bunch of people create a network of loans? Mostly it’s trust: if someone doesn’t pay back their loan, or someone in charge of holding money just goes missing or spends it, the community needs a recourse. That’s where the government comes in with its legal and justice system. Not to mention FDIC insurance in case the banking entity somehow can’t give you back your deposits.

In other words, banks really do something, at least in conjunction with the threat of jailtime, and you might not want to depend on your neighbor for that function.

That said, there is a growing movement afoot to simplify banking down to very basic functions as you describe, namely through Public Banks, although sometimes the customers are businesses and municipalities rather than individual consumers. Also don’t forget credit unions.

Aunt Pythia

——

Hi Aunt Pythia,

My husband (a mathematician) and I (a stay-at-home-mom once employed in **cough** finance) love reading your blog.

My husband is a manic-depressive. When we got married 8 years ago, we didn’t know that. And believe me, it sucked.

We made it for 3 years but that’s probably because my job had me away from home 14 hours a day. When I took him to the doctor, the diagnosis became life-changing. Now when he has a relapse, we usually see it coming and I am rooting for him instead of wondering who I’m married to.

That is, up until we had a baby last year. Our doctor is worried that emotional changes and the disruption to our schedule increases the risk of a relapse. He started a higher dosage combined with an additional daily pill.

This new level of prophylactic medication is impacting his work.

If it were just me and him, I would say, bring it, relapse! Now that we understand the relapses, they aren’t confusing or hurtful, at least not to _me_. But we are both worried about how it might affect our new family.

There must be lots of people doing research math with a variety of mental illnesses and different family arrangements, but it hasn’t been easy talking about it in his department. It doesn’t help that the relationship between mental illness and math is sometimes made out to be somewhat glamorous. What is your take on the relationship between mental illness and math research? Our other question is: what can we do so that he can work? I personally am in the locking the werewolf in his office on full moons camp, but we will run any thing that could help by our psychiatrist. A big thanks from both of us!

Hoping it’s a nonexclusive decision, life or work

Dear Hoping,

Sometimes I worry that I am unqualified to give advice in certain situations. In this case I’m not worried because I am absolutely sure that I’m unqualified to give you advice. So instead of advice, I’ll make some observations and leave it at that.

First observation: kids are resilient. They don’t need their families to be happy and perfect all the time. In fact some strife and tension is good for kids, especially when that strife is resolved and the love is there. So I’d make sure that you two explain to your child or children, even before you are sure they can understand it, that things will be all right and that you love each other and that you’re rooting for daddy to get through this tough time and that you’re sure he will. Give kids the message not that disturbances will never occur, but that they will blow over. The fact that you’ve figured out why this stuff happens is critical and revelatory, and I’m sure that as much as it helps you it will also help your family.

Second observation: math communities are not much more likely than other communities to understand or accept people with mental health problems. Math people have their quirks, and it’s possible that they are somewhat more likely to have mental health problems – and if you believe Hollywood depictions of us, we are much more likely – but when it comes to compassion and empathy I don’t think we’re there. In fact I might argue that we are a bit more on the Aspy spectrum than your usual crowd, and that makes us less empathetic in general about other kinds of mental health issues. I guess what I’m saying is that I’m not surprised your husband is having trouble talking about this at work.

My final, very very practical observation is that if you keep close track of the dosage, and the environment, and various life events, then you might be able to track the illness and find patterns that will help you balance the symptoms with the ability to do research. Another approach might be to research ways to help him realize his research potential while fully dosed – after all, his intelligence is still there. Maybe it would help to go for a brisk walk first thing in the morning and then spend 3 hours alone with a notepad? You probably already tried that, but I’m just saying you can optimize within any given set of constraints.

Again, I have no qualifications for this advice, so talk to professionals. I’m just a practical-minded person.

Finally, good luck! I’m really proud of you guys, and you in particular for leaving finance.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I just read this article about a group of insects with “female penes.” This question is two-fold: First, how would human sexuality be different if women penetrated men and forcibly extracted their sperm to impregnate themselves? Secondly, what sort of ramifications will this have on porn? (Is there already female + penis, male + vagina porn out there?)

Also, please feel free to give a scathing remark to the researcher who comments that females with penes are more “macho” than other females. Ugh.

Person Of Random News

Dear PORN,

I deeply love this article, and your sign-off, and you as a person. You have made me happy, PORN.

Readers! You now have a standard to live up to! Please take note of the perfect Aunt Pythia question.

My favorite line in the article is where a researcher describes the findings as “really, really exciting.” Also, this on the side of the article:

Pretty much everything about this article is a hoot.

And look, I realize that human females typically don’t have penises – at least until they buy them (update! by this I meant strap-ons! I had no intention of being cissexist and apologies if that’s how it came off) – but in terms of sucking sperm out of the men in order to get pregnant, that’s pretty much what all my girlfriends do once they want kids. Tell me if I’m wrong, ladies. It’s a matter of perspective of course, but there you have it. There are really more commonalities than differences here.

As for the macho comment, I think that’s kind of dumb and/or tautological. Macho just means manly, and for most people, manliness is at least confounded with, if not defined by, the presence of a penis. So if a woman has a penis, people are going to say she’s macho, especially if said penis has been built to last 70 hours and has spikes. HOLY SHIT! Tell me that’s not “really, really exciting.”

Bring it on, PORN! More articles, please!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

On Slate Money Podcast starting Saturday

There has been very little press that I can find but if you look reeeeally closely you’ll see this recent article from the New York Times, with the following line:

The digital magazine Slate will start two new podcasts in the next week: The Gist, with the former NPR reporter Mike Pesca, its first daily podcast intended to deliver news and opinion to afternoon drive-time listeners, and Money, hosted by the financial writer Felix Salmon.

And moreover, here’s a suggestion, if you squint your eyes a wee bit, you might notice that I’m actually working with Felix Salmon and Jordan Weissman on the Money podcast, starting this Saturday.

And look, I don’t listen to podcasts – yet – but maybe you do, so I thought you might like to know. I’m looking forward to doing this because it’s fun and forces me to think about various interesting topics.

Inside the Podesta Report: Civil Rights Principles of Big Data

I finished reading Podesta’s Big Data Report to Obama yesterday, and I have to say I was pretty impressed. I credit some special people that got involved with the research of the report like Danah Boyd, Kate Crawford, and Frank Pasquale for supplying thoughtful examples and research that the authors were unable to ignore. I also want to thank whoever got the authors together with the civil rights groups that created the Civil Rights Principles for the Era of Big Data:

- Stop High-Tech Profiling. New surveillance tools and data gathering techniques that can assemble detailed information about any person or group create a heightened risk of profiling and discrimination. Clear limitations and robust audit mechanisms are necessary to make sure that if these tools are used it is in a responsible and equitable way.

- Ensure Fairness in Automated Decisions. Computerized decisionmaking in areas such as employment, health, education, and lending must be judged by its impact on real people, must operate fairly for all communities, and in particular must protect the interests of those that are disadvantaged or that have historically been the subject of discrimination. Systems that are blind to the preexisting disparities faced by such communities can easily reach decisions that reinforce existing inequities. Independent review and other remedies may be necessary to assure that a system works fairly.

- Preserve Constitutional Principles. Search warrants and other independent oversight of law enforcement are particularly important for communities of color and for religious and ethnic minorities, who often face disproportionate scrutiny. Government databases must not be allowed to undermine core legal protections, including those of privacy and freedom of association.

- Enhance Individual Control of Personal Information. Personal information that is known to a corporation — such as the moment-to-moment record of a person’s movements or communications — can easily be used by companies and the government against vulnerable populations, including women, the formerly incarcerated, immigrants, religious minorities, the LGBT community, and young people. Individuals should have meaningful, flexible control over how a corporation gathers data from them, and how it uses and shares that data. Non-public information should not be disclosed to the government without judicial process.

- Protect People from Inaccurate Data. Government and corporate databases must allow everyone — including the urban and rural poor, people with disabilities, seniors, and people who lack access to the Internet — to appropriately ensure the accuracy of personal information that is used to make important decisions about them. This requires disclosure of the underlying data, and the right to correct it when inaccurate.

This was signed off on by multiple civil rights groups listed here, and it’s a great start.

One thing I was not impressed by: the only time the report mentioned finance was to say that, in finance, they are using big data to combat fraud. In other words, finance was kind of seen as an industry standing apart from big data, and using big data frugally. This is not my interpretation.

In fact, I see finance as having given birth to big data. Many of the mistakes we are making as modelers in the big data era, which require the Civil Rights Principles as above, were made first in finance. Those modeling errors – and when not errors, politically intentional odious models – were created first in finance, and were a huge reason we first had the mortgage-backed-securities rated with AAA ratings and then the ensuing financial crisis.

In fact finance should have been in the report standing as a worst case scenario.

One last thing. The recommendations coming out of the Podesta report are lukewarm and are even contradicted by the contents of the report, as I complained about here. That’s interesting, and it shows that politics played a large part of what the authors could include as acceptable recommendations to the Obama administration.

Podesta’s Big Data report to Obama: good but not great

This week I’m planning to read Obama’s new big data report written by John Podesta. So far I’ve only scanned it and read the associated recommendations.

Here’s one recommendation related to discrimination:

Expand Technical Expertise to Stop Discrimination. The detailed personal profiles held about many consumers, combined with automated, algorithm-driven decision-making, could lead—intentionally or inadvertently—to discriminatory outcomes, or what some are already calling “digital redlining.” The federal government’s lead civil rights and consumer protection agencies should expand their technical expertise to be able to identify practices and outcomes facilitated by big data analytics that have a discriminatory impact on protected classes, and develop a plan for investigating and resolving violations of law.

First, I’m very glad this has been acknowledged as an issue; it’s a big step forward from the big data congressional subcommittee meeting I attended last year for example, where the private-data-for-services fallacy was leaned on heavily.

So yes, a great first step. However, the above recommendation is clearly insufficient to the task at hand.

It’s one thing to expand one’s expertise – and I’d be more than happy to be a consultant for any of the above civil rights and consumer protection agencies, by the way – but it’s quite another to expect those groups to be able to effectively measure discrimination, never mind combat it.

Why? It’s just too easy to hide discrimination: the models are proprietary, and some of them are not even apparent; we often don’t even know we’re being modeled. And although the report brings up discriminatory pricing practices, it ignores redlining and reverse-redlining issues, which are even harder to track. How do you know if you haven’t been made an offer?

Once they have the required expertise, we will need laws that allow institutions like the CFPB to deeply investigate these secret models, which means forcing companies like Larry Summer’s Lending Club to give access to them, where the definition of “access” is tricky. That’s not going to happen just because the CFPB asks nicely.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

You know how sometimes when you wake up, your back hurts and you’re still pissed at the guy who shoved you on the subway when it rained and service was slow, but then other days you wake up and you just want to hug everyone you see and make the world some chocolate chip cookies? Well Aunt Pythia is in the chocolate chip cookie kind of a place today, so welcome in, and tell me if you’d prefer gluten free.

Aunt Pythia is here for you, my friends, and she’s listening to your complaints and questions with a sympathetic ear and an empathetic heart. She wants to help and to nurture, and she hopes she does both.

Please, after enjoying today’s Aunt Pythia post and cookies and advice:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt-Mama-Dr.-Professor-Occupier-Quant Pythia,

My question is: how do you do it? Are there more hours in your day than there are in my day? More days in your week? Do you have extra fingers? Seriously; do you have a schedule you keep? Wing it? What’s the deal?

Awed Observer

Dear AO,

Awww.

First of all, some of it is illusory. I am no longer a quant, nor a professor. Although I work at Columbia again, I am now officially part of the administrative bloat, as a Program Director: staff, not faculty. So the first trick is to switch jobs a lot. That makes you seem really diverse.

Next, here are my tricks for avoiding ever wasting time. First of all, I am creative and I squeeze stuff into corners and spaces in time. I blog before anyone else wakes up, for example. I absolutely have a calendar, and the best part about it is saving space for my own thoughts and writing on it.

In other words, I use my calendar as a device to avoid scheduling stuff. Actually putting stuff on my calendar is a regrettable and final option. And that means I say no to almost everything that I can. I have not once gone to an event at my kids’ school that I didn’t have to, and I’ve also skipped the majority of required events, which makes me a huge asshole but also saves an asston of time. Plus my kids don’t like organized sports, bless their hearts, so I never go to soccer games and such. Huge time sink. I don’t even have a car, so I never get stuck in traffic.

I also rarely exercise or shower. My biggest luxury is sleep, which I do whenever I can. I am, in short, a disgusting human being.

Finally, a few odds and ends: it helps that I am a neglectful parent, and that I have a great coffee machine. The former allows me to ignore my kids whenever they want to ignore me, which is to say blissfully often, and the latter allows me to start writing almost immediately after waking up.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

You have provided advice to a reader about the custom of giving tips to service sector workers. I confess that I sometimes inadvertently forget this, usually when patronising a restaurant or salon staffed by migrants from my homeland, because we are all in there speaking our own language and I forget that I am in a different country.

Can you think of any other unusual/unique customs calling for special vigilance on the part of newcomers?

Thank you!

Always be Courteous

Dear AbC,

Thanks for giving me an excuse to get people to see these NYC Subway Etiquette cartoons, they are a hoot! And so wise and true. Here’s an important one:

And here’s a funny one:

There are more here.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I came across this description of Barnard here, and it contained the following:

Because of its relationship with Columbia, Barnard has in effect no ability to govern itself. It cannot and/or will not support its own faculty. Its faculty go through two tenure processes, the first at Barnard, the second at Columbia. Columbia gets the final say. This means that even if Barnard votes to grant a beloved faculty member tenure, Columbia can still turn the person down, and the person will be fired. There have been a number of shocking well-publicized cases of this kind, and also of the type where the Barnard tenure committee will deny a faculty member tenure in anticipation or fear of a rejection by Columbia. This points to the pervasive, utterly depressing inferiority complex and Columbia-loathing (which has nothing to do with Columbia and everything to do with Barnard) which characterizes the Barnard faculty and administration as a whole. Barnard faculty have to meet Columbia’s standards for tenure, yet Barnard faculty are paid less, teach more, and do not have access to benefits including housing and access to the school for faculty children. Finally, the crowning insult: Barnard tenures fewer women than Columbia–more evidence of the institution’s crippling self-loathing complex. It doesn’t help that the place is stacked with “spousal hires,” the less-qualified wives of Columbia profs. A nice place to teach for a few years, but don’t go anywhere near the tenure process, and don’t expect any kind of collegiality.

I can’t remember, but weren’t you at Barnard for a while? Any comments on the above description?

Milly

Dear Milly,

I really liked Barnard personally. I did notice people assuming that I was only hired because they wanted my husband at the Columbia math department, but I don’t blame Barnard for that, I blame those people. And wait, I didn’t assume it exactly, they told me that with their own mouths. Assholes.

I’ll speak for myself when I say that there is a weird relationship between the two schools, and probably weirder still in the math department because it’s a combined Barnard/ Columbia department, housed at Columbia. But I never felt self-loathing personally. Even so, it’s a personality thing: if someone treats you bad, do you blame them or do you blame yourself? I blame them.

This is honestly a much bigger conversation, but the whole thing about access to Columbia resources can be traced to the relative sizes of Columbia’s endowment versus Barnard’s, which itself can be traced to the sexist practices of alums back in the day, where Columbia was male-only and a Columbia man would marry a Barnard girl, they’d get rich, and then they’d give money to Columbia. The end result is that Barnard is relatively poor.

There are various ways to address this, but sadly Barnard’s current approach is horrible and includes taking Ina Drew as a trustee in order to whore themselves for more endowment. Ew.

Auntie P

——

Aunt Pythia,

The BK from this Aunt Pythia column is almost surely not the real BK. The story sounds too close to the Belle Knox story that made CNN several weeks ago. A student at Duke who didn’t want to go into debt and feels that this society is too prudish and went into porn. Outed by classmates Duke thankfully said it has no rules about outside employment. Good for them. But I doubt she is writing mathbabe because she is going into law.

It’s a wonderful story and I do believe our views are changing about sex and porn in the USA. Albeit slowly. Yes it’s objectifying, that’s the point. Like the point of finance is to make money. But there can be morals in both industries there is just too little of them now.

You may have been punked

Dear Ymhbp,

Yes I was totally fooled, although I don’t care at all, and I stand by my advice. As for the true BK, I still worry about her, especially now that I’ve googled her name and seen how much shit she’s had to go through. I gotta say, I’m not very impressed with our views here in the USA.

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

No, Sandy Pentland, let’s not optimize the status quo

It was bound to happen. Someone was inevitably going to have to write this book, entitled Social Physics, and now someone has just up and done it. Namely, Alex “Sandy” Pentland, data scientist evangelist, director of MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, and co-founder of the MIT Media Lab.

A review by Nicholas Carr

This article entitled The Limits of Social Engineering, published in MIT’s Technology Review and written by Nicholas Carr (hat tip Billy Kaos) is more or less a review of the book. From the article:

Pentland argues that our greatly expanded ability to gather behavioral data will allow scientists to develop “a causal theory of social structure” and ultimately establish “a mathematical explanation for why society reacts as it does” in all manner of circumstances. As the book’s title makes clear, Pentland thinks that the social world, no less than the material world, operates according to rules. There are “statistical regularities within human movement and communication,” he writes, and once we fully understand those regularities, we’ll discover “the basic mechanisms of social interactions.”

By collecting all the data – credit card, sensor, cell phones that can pick up your moods, etc. – Pentland seems to think we can put the science into social sciences. He thinks we can predict a person like we now predict planetary motion.

OK, let’s just take a pause here to say: eeeew. How invasive does that sound? And how insulting is its premise? But wait, it gets way worse.

The next think Pentland wants to do is use micro-nudges to affect people’s actions. Like paying them to act a certain way, and exerting social and peer pressure. It’s like Nudge in overdrive.

Vomit. But also not the worst part.

Here’s the worst part about Pentland’s book, from the article:

Ultimately, Pentland argues, looking at people’s interactions through a mathematical lens will free us of time-worn notions about class and class struggle. Political and economic classes, he contends, are “oversimplified stereotypes of a fluid and overlapping matrix of peer groups.” Peer groups, unlike classes, are defined by “shared norms” rather than just “standard features such as income” or “their relationship to the means of production.” Armed with exhaustive information about individuals’ habits and associations, civic planners will be able to trace the full flow of influences that shape personal behavior. Abandoning general categories like “rich” and “poor” or “haves” and “have-nots,” we’ll be able to understand people as individuals—even if those individuals are no more than the sums of all the peer pressures and other social influences that affect them.

Kill. Me. Now.

The good news is that the author of the article, Nicholas Carr, doesn’t buy it, and makes all sorts of reasonable complaints about this theory, like privacy concerns, and structural sources of society’s ills. In fact Carr absolutely nails it (emphasis mine):

Pentland may be right that our behavior is determined largely by social norms and the influences of our peers, but what he fails to see is that those norms and influences are themselves shaped by history, politics, and economics, not to mention power and prejudice. People don’t have complete freedom in choosing their peer groups. Their choices are constrained by where they live, where they come from, how much money they have, and what they look like. A statistical model of society that ignores issues of class, that takes patterns of influence as givens rather than as historical contingencies, will tend to perpetuate existing social structures and dynamics. It will encourage us to optimize the status quo rather than challenge it.

How to see how dumb this is in two examples

This brings to mind examples of models that do or do not combat sexism.

First, the orchestra audition example: in order to avoid nepotism, they started making auditioners sit behind a sheet. The result has been way more women in orchestras.

This is a model, even if it’s not a big data model. It is the “orchestra audition” model, and the most important thing about this example is that they defined success very carefully and made it all about one thing: sound. They decided to define the requirements for the job to be “makes good sounding music” and they decided that other information, like how they look, would be by definition not used. It is explicitly non-discriminatory.

By contrast, let’s think about how most big data models work. They take historical information about successes and failures and automate them – rather than challenging their past definition of success, and making it deliberately fair, they are if anything codifying their discriminatory practices in code.

My standard made-up example of this is close to the kind of thing actually happening and being evangelized in big data. Namely, a resume sorting model that helps out HR. But, using historical training data, this model notices that women don’t fare so well historically at a the made-up company as computer programmers – they often leave after only 6 months and they never get promoted. A model will interpret that to mean they are bad employees and never look into structural causes. And moreover, as a result of this historical data, it will discard women’s resumes. Yay, big data!

Thanks, Pentland

I’m kind of glad Pentland has written such an awful book, because it gives me an enemy to rail against in this big data hype world. I don’t think most people are as far on the “big data will solve all our problems” spectrum as he is, but he and his book present a convenient target. And it honestly cannot surprise anyone that he is a successful white dude as well when he talks about how big data is going to optimize the status quo if we’d just all wear sensors to work and to bed.

Great news: InBloom is shutting down

I’m trying my hardest to resist talking about Piketty’s Capital because I haven’t read it yet, even though I’ve read a million reviews and discussions about it, and I saw him a couple of weeks ago on a panel with my buddy Suresh Naidu. Suresh, who was great on the panel, wrote up his notes here.

So I’ll hold back from talking directly about Piketty, but let me talk about one of Suresh’s big points that was inspired in part by Piketty. Namely, the fact that it’s a great time to be rich. It’s even greater now to be rich than it was in the past, even when there were similar rates of inequality. Why? Because so many things have become commodified. Here’s how Suresh puts it:

We live in a world where much more of everyday life occurs on markets, large swaths of extended family and government services have disintegrated, and we are procuring much more of everything on markets. And this is particularly bad in the US. From health care to schooling to philanthropy to politicians, we have put up everything for sale. Inequality in this world is potentially much more menacing than inequality in a less commodified world, simply because money buys so much more. This nasty complementarity of market society and income inequality maybe means that the social power of rich people is higher today than in the 1920s, and one response to increasing inequality of market income is to take more things off the market and allocate them by other means.

I think about this sometimes in the field of education in particular, and to that point I’ve got a tiny bit of good news today.

Namely, InBloom is shutting down (hat tip Linda Brown). You might not remember what InBloom is, but I blogged about this company a while back in my post Big Data and Surveillance, as well as the ongoing fight against InBloom in New York state by parents here.

The basic idea is that InBloom, which was started in cooperation with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Rupert Murdoch’s Amplify, would collect huge piles of data on students and their learning and allow third party companies to mine that data to improve learning. From this New York Times article:

InBloom aimed to streamline personalized learning — analyzing information about individual students to customize lessons to them — in public schools. It planned to collect and integrate student attendance, assessment, disciplinary and other records from disparate school-district databases, put the information in cloud storage and release it to authorized web services and apps that could help teachers track each student’s progress.

It’s not unlike the idea that Uber has, of connecting drivers with people needing rides, or that AirBNB has, of connecting people needing a room with people with rooms: they are platforms, not cab companies or hoteliers, and they can use that matchmaking status as a way to duck regulations.

The problem here is that the relevant child data protection regulation, called FERPA, is actually pretty strong, and InBloom and companies like it were largely bypassing that law, as was discovered by a Fordham Law study led by Joel Reidenberg. In particular, the study found that InBloom and other companies were offering what seemed like “free” educational services, but of course the deal really was in exchange for the children’s data, and the school officials who were agreeing to the deals had no clue as to what they were signing. The parents were bypassed completely. Much of the time the contracts were in direct violation of FERPA, but often the school officials didn’t even have copies of the contracts and hadn’t heard of FERPA.

Because of that report and other bad publicity, we saw growing resistance in New York State by parents, school board members and privacy lawyers. And thanks to that resistance, New York State Legislature recently passed a budget that prohibited state education officials from releasing student data to amalgamators like inBloom. InBloom has subsequently decided to close down.

I’m not saying that the urge to privatize education – and profit off of it – isn’t going to continue after a short pause. For that matter look at the college system. Even so, let’s take a moment to appreciate the death of one of the more egregious ideas out there.

Warning: extremely nerdy content, harmful if taken seriously

Today I’d like to share a nerd thought experiment with you people, and since many of you are already deeply nerdy, pardon me if you’ve already thought about it. Feel free – no really, I encourage you – to argue strenuously with me if I’ve misrepresented the current thinking on this. That’s why I have comments!!

It’s called the Fermi Paradox, and it’s loosely speaking a formula that relates the probability of intelligent life somewhere besides here on earth, the probability of other earth-like planets, and the fact that we haven’t been contacted by our alien neighbors.

It starts with that last thing. We haven’t been contacted by aliens, so what gives? Is it because life-sustaining planets are super rare? Or is it because they are plentiful and life, or at least intelligent life, or at least intelligent life with advanced technology, just doesn’t happen on them? Or does life happen on them but once they get intelligent they immediately kill each other with atomic weapons?

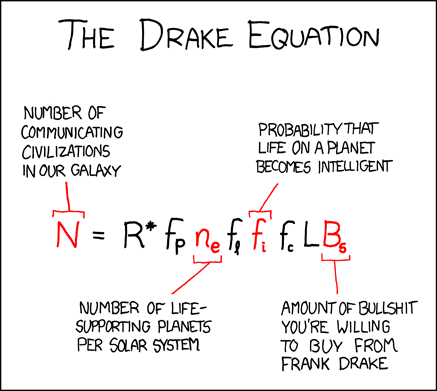

There is a supremely nerdy underlying formula to this thought experiment, which has a name – the Drake Equation. I imagine it comes in various forms but here’s one:

where:

- N = the number of civilizations in our galaxy with which radio-communication might be possible (i.e. which are on our current past light cone)

- R* = the average rate of star formation in our galaxy

- fp = the fraction of those stars that have planets

- ne = the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star that has planets

- fl = the fraction of planets that could support life that actually develop life at some point

- fi = the fraction of planets with life that actually go on to develop intelligent life (civilizations)

- fc = the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence into space

- L = the length of time for which such civilizations release detectable signals into space[8]

So the bad news (hat tip Suresh Naidu) is that, due to scientists discovering more earth-like planets recently, we’re probably all going to die soon.

Here’s the reasoning. Notice in the above equation that N is the product of a bunch of things. If N doesn’t change but our estimate of one of those terms goes up or down, then the other terms have to go down or up to compensate. And since finding a bunch of earth-like planets increases some combination of R*, fp, and ne, we need to compensate with some combination of the other terms. But if you look at them the most obvious choice is L, the length of time civilizations release detectable signals into space.

And I say “most obvious” because it makes the thought experiment more fun that way. Also we exist as proof that some planets do develop intelligent life with the technology to send out signals into space but we have no idea how long we’ll last.

Anyhoo, not sure if there are actionable items here except for maybe deciding to stop looking for earth-like planets, or deciding to stop emitting signals to other planets so we can claim other aliens didn’t obliterate themselves, they were simply “too busy” to call us (we need another term which represents the probability of the invention of Candy Crush Saga!!!). Or maybe they took a look from afar and saw reality TV and decided we weren’t ready, a kind of updated Star Trek first contact kind of theory.

Update: I can’t believe I didn’t add an xkcd comic to this, my bad. Here’s one (hat tip Suresh Naidu):

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Beep, beep! The nerd advice column bus is here, and impatient to start. Aunt Pythia is driving that nerd advice column bus. Cool? Are we getting the imagery? Also, the bus is painted in bright colors and has plastic flowers glued on to it in all sizes and fashions. It’s kind of a psychedelic hippy nerd advice column bus. And it’s rarin’ to go. There might be tinted windows too, not sure. Wait, yes there are, a few, in the back. Who knows what’s going on in there. I hear there’s a mini fridge and a couch back there too, but that was just a rumor.

After riding in – and exploring – Aunt Pythia’s spacious bus, please:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Aunt Pythia,

How do I deal with the possibility that my skills as a scientist will become less hot?

I just defended and got an awesome technical staff gig. There is some grinding, and some research. I’m trying to stay published although I don’t want to ever be a professor. But there were hot spots of research I could see coming up as I was writing my dissertation, and neat projects underway with the new grad students using techniques I never practiced. We could hire some of them soon.

I’m afraid of being pigeon-holed to do exactly what I did in grad school, but I also don’t know how wide to spread myself; especially since I am now working with other professionals who (although not in my field) have spent years doing what I would be learning, and might more reasonably be assigned much of the task.

If I am a smart, capable researcher with good connections now, will I always be? Will I be discarded in 5y for some young, hot thang? Will my salary always beat inflation?

Crisis Of Narcissism

Dear CON,

Stay connected, go to interesting talks, don’t be an asshole, ask good questions, be generous to others, prevent yourself from stewing in jealousy, and you’ll be fine. Or else you won’t be fine because the whole economy blows up, but then it’s a crisis for everyone. I’m not worried about you in particular.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Please excuse my bad manners when I addressed you by your first name sans the kinship relation. I vow to be a better nephew in the future! 🙂

Glad my reply to your reply about fairness rankings provided a good rant opening for you (on America’s outrageous prison system). Yes, I think the relative chance of not being incarcerated for an action that under law can bring incarceration, and other probabilities like it, would make a great start towards an overall fairness measure. If possible I’d also like to measure how fair the laws and legal system are to begin with. The sheer number of laws on the books would probably play a role in this, but since this number is partly just a reflection of societal complexity, there would need to be more.

Yours,

Elvis Von Essende Nicholas Friedrich Lester Otto Widener IV

Dear EVENFLOW IV,

Do you know what you (and everyone else on the bus) need(s) to do? Read The New Jim Crow. I just finished it. Devastating.

One of her major points is that the rules and laws are often colorblind or otherwise written to be fair, but they are not deployed in a fair manner. Specifically low-level drug charges are hugely discriminatory and largely responsible for the mass incarceration of so many black men that we’ve grown accustomed to during the last 25 year of the so-called War on Drugs.

In other words, the official rulebooks are rarely on their face unfair. The system has grown smarter than that. It’s an argument for understanding effective racism rather than deliberate racism, for example, by measuring outcomes.

Of course there are other ways to be unfair as well besides race, but I’m fairly convinced this is the biggie.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a undergrad in mathematics and want want to pursue research in pure mathematics. I claim no evidence for any exceptional ability in math and I wanna do it because I like it.

First of all the choice of Math as a major was rather criticized from where I come from (they are more into engineering). So I looked up for the opportunities for a math grad and realized that they are immense. But rather alarmingly I came to know that the recent opportunities in math are almost exclusively in Applied Math.

I would like to know if indeed there exist a place for someone average (in contrast to the math geniuses out there) to do pure math research and get a well-to-do job?

I never wanted a very high paying and demanding job. Just a simple one where I could be happy and free and won’t have to worry about my employment in near future.

Hoping that you would understand,

Thanking you,

A math undergrad

Dear math undergrad,

Very few people get paid to simply think about pure math. It’s a fact. Even professors are expected to teach. The exceptions are the faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study. There aren’t very many of those.

So, I’m glad you like math, but the chances that you’re going to get a well-to-do job thinking about pure math when you’re not particularly talented at math are slim. Of course, you might be wrong, and you might be super talented at math. People are notoriously bad at knowing that kind of thing because they get distracted with things like social expectations and shitty timed math tests.

But let me take your word for it for the sake of the argument, that you’re into math but not very good at it. Actually I’ll assume you’re pretty good at it but not super top-notch. In that case I suggest you think about getting a job that allows you to pair your love for pure math research with something else, like teaching (of course you have to be quite good at math to teach it but there are different levels), or doing basic analysis in industry (i.e. applied math). There are lots of jobs that fall into this category, so don’t despair. Check them out with an open mind, many of them are very interesting. And good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What is this preoccupation with size? There’s any number of baseless articles, in silly magazines, implying (or worse, stating) some link between hand – genital – finger – brain – height – etc, with some aspect of sexual prowess – desirability – ability – intention – inclination.

And now the silliness has spread, zombie-like, to your readers!

So, how would one go about showing a correlation between gullibility and inconsequential ideas?

Satisfied in Melbourne

Dear SiM,

I think of this stuff as pure entertainment. People just want to talk about sex because they like sex and, although they can’t just have sex with random people (or so they think), they can strike up a ridiculous conversation about the relationship between hands and genitals. I’ll speak for myself when I say that I do that because I actually just want to talk about genitals. There, I said it, my secret’s out. Everybody knew that already. That’s why I blog.

It reminds me of the debate on pubic hair and shaving (or not shaving: Bush is Back, Baby). At the worst moment this seems like yet another oppressive patriarchal scheme to infantilize women. On the other hand, I’ve never heard of a man who, when actually confronted with copious hair, has refused to go along with it. So I’m tempted to think that for most men, and most of the time, it’s just an excuse to think about genitals rather than an oppressive scheme.

I mean, it’s both, but this morning I’m feeling generous.

In terms of the relationship between gullibility and inconsequential ideas, I think that’s the wrong question. We should really be thinking about the relationship between insecurity and inconsequential ideas, and we should use as the prime example the beauty industry. First they make us insecure, then we obsess over trivial and inconsequential things. But it’s insecurity that makes us gullible.

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Is math an art or a science?

I left academic math in 2007, but I still identify as a mathematician. That’s just how I think about the world, through a mathematician’s mindset, whatever that means.

Wait what does that mean? How do I characterize the mathematician’s mindset? I’ve struggled in the past to try, but a few days ago, a part of it got a little bit easier.

I was talking to my friend Matt Jones – an historian of science, actually – about the turf wars inside computer science surrounding functional versus object oriented programming. It seems like questions about which one is better or when is one more appropriate than the other have become so political that they are no longer inside the scientifically acceptable realm.

But that kind of reminded me of the turf war of the bayesian versus frequentist statisticians. Or the fresh water versus salt water economists. Or possibly the string theorists versus the non-string theorists in physics.

What’s going on in all of those fields, as best I can understand, is that different groups within the field have different assumptions about what the field may assume and what it’s trying to accomplish, and they fight over the validity of those sets of assumptions. The fights themselves, which are often emotional and brutal, expose the underlying assumptions in certain ways. Matt told me that historians often get at a fields assumptions through these wars.

Here’s the thing, though, math doesn’t have that. I’m not saying there are no turf wars at all in math, there certainly are, but they aren’t political in nature exactly. They are aesthetic.

In the context of mathematics, where nothing can be considered truly inappropriate as long as the assumptions are clear, it’s all about whether something is beautiful or important, not whether it is valid. Validity has no place in mathematics per se, which plays games with logical rules and constructs. I could go off an build a weird but internally logical universe on my own, and no mathematician would complain it’s invalid, they’d only complain it’s unimportant if it doesn’t tie back to their field and help them prove a theorem.

I claim that this turf war issue is a characterizing issue of the field of mathematics versus the other sciences, and makes it more of an art than a science.

To finish my argument I’d need to understand more about how artistic fields fight, and in particular that their internally hurled insults focus more on aesthetics than on validity, say in composition or painting. I can’t imagine it otherwise, but who knows. Readers, please chime in with evidence in either direction.

I burned my eyes reading the Wall Street Journal this morning

If you want to do yourself a favor, don’t read this editorial from the Wall Street Journal like I did. It’s an unsigned “Review & Outlook” piece which I’m guessing was written by Rupert Murdoch himself.

Entitled Telling Students to Earn Less: Obama now calls for reforming his bleeding college loan program, it’s a rant against Obama’s Pay As You Earn plan, and it’s vitriolic, illogical, and mean. It makes me honestly embarrassed for the remaining high-quality journalists working at the WSJ who have to put up with this. An excerpt:

Pay As You Earn allows students under certain circumstances to borrow an unlimited amount and then cap monthly payments at 10% of their discretionary income. If they choose productive work in the private economy, the loans are forgiven after 20 years. But if they choose to work in government or for a nonprofit, Uncle Sugar forgives their loans after 10 years.

Uncle Sugar? Is this intended to make us think about the Huckabee birth control debate?

Here’s the thing. I’m not someone who always wants people to talk about the President in hushed and solemn terms or anything. The president is fair game, as are his policies. And in Obama’s case, I am not a big fan. For that matter, I don’t think his education policy has any hope, even if it’s well-intentioned. But I just don’t understand how an article like this can be published in a respectable newspaper. It does not advance the debate.

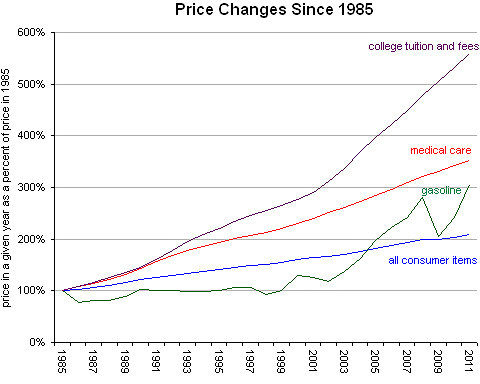

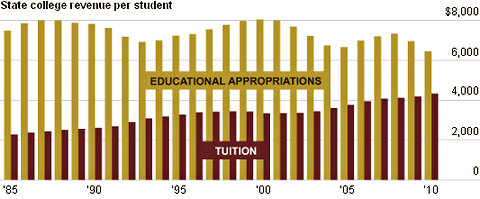

For the record, college tuition has been going up for a while, way before Obama:

And it’s not just that tuition has been going up, at least at state school. It’s that state funding has been going down:

Next, it’s true that just supplying more loans to federal students doesn’t cut it: tuition rises to meet that ability to pay. In fact that’s part of what’s going on in the above picture.

What we have here is a feedback loop, and it’s hard to break. My personal approach would be to make state schools free to make the overall field competitive for college costs. And yes, that would mean the state pays the schools directly instead of handing out money to students in the form of loans. It’s called an investment in our future, and it also would help with the mobility problems we have. At some point I’m sure it seemed like a terrible idea to form a public elementary school system for free, but we don’t think so now (or do we, Rupert?).

The biggest gripe, if you can get through the article, is that Obama’s plan will allow students to pay off their loans with at most 10% of their salaries after college, and that certain people can stop paying after 10 years instead of 20. If you read from the excerpt above, this is an outrage and those unfairly entitled people are characterized as government and nonprofit workers, but the truth is the exemptions include people who work as police officers, as healthcare workers, in law, or in the military as well.

The ending of the article, which again I suggest you don’t read, is this:

The consequences for our economy are no less tragic than for the individual borrowers. They are being driven away from the path down which their natural ambition and talent might have taken them. President Obama keeps talking about reducing income equality. So why does he keep paying young people not to pursue higher incomes?

All I can say is, what? I get that Rupert or whoever wrote this likes private industry, but the claim that by encouraging a bunch of people to go into super high paying private jobs we will reduce income inequality is just weird. Has that person not understood the relationship between inequality and CEO pay?

I say if you are so gung-ho about private high-paying jobs, then you also need to embrace rising inequality. Do it in the name of free-market capitalism or something, but please stay logical.

Interview with a middle school math teacher on the Common Core

Today’s post is an email interview with Fawn Nguyen, who teaches math at Mesa Union Junior High in southern California. Fawn is on the leadership team for UCSB Mathematics Project that provides professional development for teachers in the Tri-County area. She is a co-founder of the Thousand Oaks Math Teachers’ Circle. In an effort to share and learn from other math teachers, Fawn blogs at Finding Ways to Nguyen Students Over. She also started VisualPatterns.org to help students develop algebraic thinking, and more recently, she shares her students’ daily math talks to promote number sense. When Fawn is not teaching or writing, she is reading posts on mathblogging.org as one of the editors. She sleeps occasionally and dreams of becoming an architect when all this is done.

Importantly for the below interview, Fawn is not being measured via a value-added model. My questions are italicized.

——

I’ve been studying the rhetoric around the mathematics Common Core State Standard (CCSS). So far I’ve listened to Diane Ravitch stuff, I’ve interviewed Bill McCallum, the lead writer of the math CCSS, and I’ve also interviewed Kiri Soares, a New York City high school principal. They have very different views. Interestingly, McCallum distinguished three things: standards, curriculum, and testing.

What do you think? Do teachers see those as three different things? Or is it a package deal, where all three things rolled into one in terms of how they’re presented?

I can’t speak for other teachers. I understand that the standards are not meant to be the curriculum, but the two are not mutually exclusive either. They can’t be. Standards inform the curriculum. This might be a terrible analogy, but I love food and cooking, so maybe the standards are the major ingredients, and the curriculum is the entrée that contains those ingredients. In the show Chopped on Food Network, the competing chefs must use all 4 ingredients to make a dish – and the prepared foods that end up on the plates differ widely in taste and presentation. We can’t blame the ingredients when the dish is blandly prepared any more than we can blame the standards when the curriculum is poorly written.

Similary, the standards inform testing. Test items for a certain grade level cover the standards of that grade level. I’m not against testing. I’m against bad tests and a lot of it. By bad, I mean multiple-choice items that require more memorization than actual problem solving. But I’m confident we can create good multiple-choice tests because realistically a portion of the test needs to be of this type due to costs.

The three – standards, curriculum, and testing – are not a “package deal” in the sense that the same people are not delivering them to us. But they go together, otherwise what is school mathematics? Funny thing is we have always had the three operating in schools, but somehow the Common Core State Standands (CCSS) seem to get the all the blame for the anxieties and costs connected to testing and curriculum development.

As a teacher, what’s good and bad about the CCSS?

I see a lot of good in the CCSS. This set of standards is not perfect, but it’s much better than our state standards. We can examine the standards and see for ourselves that the integrity of the standards holds up to their claims of being embedded with mathematical focus, rigor, and coherence.

Implementation of CCSS means that students and teachers can expect consistency in what is being in taught at each grade level across state boundaries. This is a nontrivial effort in addressing equity. This consistency also helps teachers collaborate nationwide, and professional development for teachers will improve and be more relevant and effective.

I can only hope that textbooks will be much better because of the inherent focus and coherence in CCSS. A kid can move from Maine to California and not have to see different state outlines on their textbooks as if he’d taken on a new kind of mathematics in his new school. I went to a textbook publishers fair recently at our district, and I remain optimistic that better products are already on their way.

We had every state create its own assessment, now we have two consortia, PARCC and Smarter Balanced. I’ve gone through the sample assessments from the latter, and they are far better than the old multiple-choice items of the CST. Kids will have to process the question at a deeper level to show understanding. This is a good thing.

What is potentially bad about the CCSS is the improper or lack of implementation. So, this boils down to the most important element of the Common Core equation – the teacher. There is no doubt that many teachers, myself included, need sustained professional development to do the job right. And I don’t mean just PD in making math more relevant and engaging, and in how many ways we can use technology, I mean more importantly, we need PD in content knowledge.

It is a perverse notion to think that anyone with a college education can teach elementary mathematics. Teaching mathematics requires knowing mathematics. To know a concept is to understand it backward and forward, inside and outside, to recognize it in different forms and structures, to put it into context, to ask questions about it that leads to more questions, to know the mathematics beyond this concept. That reminds me just recently a 6th grader said to me as we were working on our unit of dividing by a fraction. She said, “My elementary teacher lied to me! She said we always get a smaller number when we divide two numbers.”

Just because one can make tuna casserole does not make one a chef. (Sorry, I’m hungry.)

What are the good and bad things for kids about testing?

Testing is only good for kids when it helps them learn and become more successful – that the feedback from testing should inform the teacher of next moves. Testing has become such a dirty word because we over test our kids. I’m still in the classroom after 23 years, yet I don’t have the answers. I struggle with telling my kids that I value them and their learning, yet at the end of each quarter, the narrative sum of their learning is a letter grade.

Then, in the absence of helping kids learn, testing is bad.

What are the good/bad things for the teachers with all these tests?

Ideally, a good test that measures what it’s supposed to measure should help the teacher and his students. Testing must be done in moderation. Do we really need to test kids at the start of the school year? Don’t we have the results from a few months ago, right before they left for summer vacation? Every test takes time away from learning.

I’m not sure I understand why testing is bad for teachers aside from lost instructional minutes. Again, I can’t speak for other teachers. But I do sense heightened anxiety among some teachers because CCSS is new – and newness causes us to squirm in our seats and doubt our abilities. I don’t necessarily see this as a bad thing. I see it as an opportunity to learn content at a deeper conceptual level and to implement better teaching strategies.

If we look at anything long and hard enough, we are bound to find the good and the bad. I choose to focus on the positives because I can’t make the day any longer and I can’t have fewer than 4 hours of sleep a night. I want to spend my energies working with my administrators, my colleagues, my parents to bring the best I can bring into my classroom.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

The best things about CCSS for me are not even the standards – they are the 8 Mathematical Practices. These are life-long habits that will serve students well, in all disciplines. They’re equivalent to the essential cooking techniques, like making roux and roasting garlic and braising kale and shucking oysters. Okay, maybe not that last one, but I just got back from New Orleans, and raw oysters are awesome.

I’m excited to continue to share and collaborate with my colleagues locally and online because we now have a common language! We teachers do this very hard work – day in and day out, late into the nights and into the weekends – because we love our kids and we love teaching. But we need to be mathematically competent first and foremost to teach mathematics. I want the focus to always be about the kids and their learning. We start with them; we end with them.

A simple mathematical model of congressional geriatric penis pumps

This is a guest post written by Stephanie Yang and reposted from her blog. Stephanie and I went to graduate school at Harvard together. She is now a quantitative analyst living in New York City, and will be joining the data science team at Foursquare next month.

Last week’s hysterical report by the Daily Show’s Samantha Bee on federally funded penis pumps contained a quote which piqued our quantitative interest. Listen carefully at the 4:00 mark, when Ilyse Hogue proclaims authoritatively:

Last week’s hysterical report by the Daily Show’s Samantha Bee on federally funded penis pumps contained a quote which piqued our quantitative interest. Listen carefully at the 4:00 mark, when Ilyse Hogue proclaims authoritatively:

“Statistics show that probably some our members of congress have a vested interested in having penis pumps covered by Medicare!”

Ilya’s wording is vague, and intentionally so. Statistically, a lot of things are “probably” true, and many details are contained in the word “probably”. In this post we present a simple statistical model to clarify what Ilya means.

First we state our assumptions. We assume that penis pumps are uniformly distributed among male Medicare recipients and that no man has received two pumps. These are relatively mild assumptions. We also assume that what Ilya refers to as “members of Congress [with] a vested interested in having penis pumps covered by Medicare,” specifically means male member of congress who received a penis pump covered by federal funds. Of course, one could argue that female members congress could also have a vested interested in penis pumps as well, but we do not want to go there.

Now the number crunching. According to the report, Medicare has spent a total of $172 million supplying penis pumps to recipients, at “360 bucks a pop.” This means a total of 478,000 penis pumps bought from 2006 to 2011.

45% of the current 49,435,610 Medicare recipients are male. In other words, Medicare bought one penis pump for every 46.5 eligible men. Inverting this, we can say that 2.15% of male Medicare recipients received a penis pump.

There are currently 128 members of congress (32 senators plus 96 representatives) who are males over the age of 65 and therefore Medicare-eligible. The probability that none of them received a federally funded penis pump is:

In other words, the chances of at least one member of congress having said penis pumps is 93.8%, which is just shy of the 95% confidence that most statisticians agree on as significant. In order to get to 95% confidence, we need a total of 138 male members of congress who are over the age of 65, and this has not happened yet as of 2014. Nevertheless, the estimate is close enough for us to agree with Ilya that there is probably someone member of congress who has one.

Is it possible that there two or more penis pump recipients in congress? We did notice that Ilya’s quote refers to plural members of congress. Under the assumptions laid out above, the probability of having at least two federally funded penis pumps in congress is:

Again, we would say this is probably true, though not nearly with the same amount of confidence as before. In order to reach 95% confidence that there are two or moreq congressional federally funded penis pump, we would need 200 or more Medicare-eligible males in congress, which is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Note: As a corollary to these calculations, I became the first developer in the history of mankind to type the following command: git merge --squash penispump.

Guest rant about rude kids

Today’s guest post was written by Amie, who describes herself as a mom of a 9 and a 14-year-old, mathematician, and bigmouth.

Nota bene: this was originally posted on Facebook as a spontaneous rant. Please don’t miscontrue it as an academic argument.

Time for a rant. I’ll preface this by saying that while my kids are creative, beautiful souls, so are many (perhaps all) children I’ve met, and it would be the height of arrogance to take credit for that as a parent. But one thing my husband and I can take credit for are their good manners, because that took work to develop.

The first phrase I taught me daughter was “thank you,” and it’s been put to good use over the years. I’m also loathe to tell other parents what to do, but this is an exception: teach your fucking kids to say “please” and “thank you”. If you are fortunate to visit another country, teach them to say “please” and “thank you” in the native language.

After a week in paradise at a Club Med in Mexico, I’m at some kind of breaking point with rude rich people and their spoiled kids. And that includes the Europeans. Maybe especially the Europeans. What is it that when you’re in France everyone’s all “thank you and have a nice day” but when these petit bourgeois assholes come to Cancun they treat Mexicans like nonhumans? My son held the door for a face-lifted Russian lady today who didn’t even say thank you.

Anyway, back to kids: I’m not saying that you should suppress your kids’ nature joie de vivre and boisterous, rambunctious energy (though if that’s what they’re like, please keep them away from adults who are not in the mood for it). Just teach them to treat other people with basic respect and courtesy. That means prompting them to say “please,” “thank you,” and “nice to meet you” when they interact with other people.

Jordan Ellenberg just posted how a huge number of people accepted to the math Ph.D. program at the University of Wisconsin never wrote to tell him that they had accepted other offers. When other people are on a wait list!

Whose fault is this? THE PARENTS’ FAULT. Damn parents. Come on!!

P.S. Those of you who have put in the effort to raise polite kids: believe me, I’ve noticed. So has everyone else.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Great to be here, and glad you came.

Please hop on the nerd advice column bus for another week of ridiculous if not damaging guidance from yours truly, Aunt Pythia.

And please, after enjoying today’s counsel to other poor, unsuspecting fools:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Aunt Pythia,

I’m so SORRY. When I asked your opinion about conference sex the other week I thought I had pasted the link to the article: Will you still medal in the morning? It’s all about the behind the scenes sex at the Olympics.

ORR

Dear ORR,

Let me remind readers of your original question (after giving them a chance to read the article). You (thought you) gave me the link and then made the comment:

If conferences like JMM were to have bowls of condoms at the end of the tables where you pick up your badge do you think people would get the idea and pocket a hand full, then use them?

Answer: no. And that’s a good thing. As much as I’m sex positive, and I truly am, I don’t think what’s going on there in the Olympic Village is really about sex. I mean, that’s super dumb for me to say, because obviously tons of sex is happening, but it’s really about freedom and control and conquests.

So, for example, when you go to college, you notice that the kids who had controlling parents and no freedom in high school are particularly prone to spending too much money, drinking too hard, and fucking anything that moves, even relative to the kids whose upbringing was more relaxed and free. It’s about asserting control over their destiny and their freedom, and it lasts a couple of months and then calms down, hopefully in time for them to pass their classes. I’m absolutely sure of this phenomenon but come to think of it I’ve never seen statistics, which is probably a good thing.

Now think about Olympic athletes. They have lives utterly controlled by their coaches and parents and practices, and between you and me it’s often a neglectful if not abusive situation for those kids. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying they hate every minute of it, especially the ones we hear from who win the medals, but if you account for the selection bias for a minute and just think about the childhoods these kids have, your heart breaks for them.

So when they finally get to be somewhere away from their coaches, and this ridiculous pressure is off after their events, they need to somehow assert their freedom to themselves, and the most obvious way to do that is to party hard and fuck anything that moves. Plus it’s even better if they have a long list of conquests, because they’ve been trained to be super competitive.

Now think about math people to contrast this. I’m not saying no condoms are used at a math conference, but generally speaking math people have agency over their own lives, time to have sex when they want and so on, so when they get to a math conference, they just have more of the same. There’s some tension built up before one’s talk, and so in that sense there’s some blowing off of steam, but it’s not Olympic level.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I wrote to you a while ago ranting about how my boss sold me a middle-office IT job as a front-office quant role. Anyways, just wanted to let you know that I did manage to land a quant research role at another buy-side firm, and even though you can’t tell if it’s a scam without being there, it seems promising (I’ll start in about a month). I asked smarter questions this time and the pieces seem to be lining up. I want to thank you for providing a voice of sanity, which is always welcome but especially crucial in trying times where one needs to cut through cognitive dissonance.

Perennial Employee

Dear PE,

Awesome!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Reading about people who are trying to find love or a companion at various places (via online dating or in physical environments) at Aunt Pythia’s Saturday column, why do not you consider creating an online dating site for these high-profile intellectuals?

I considered doing this myself during graduate school when I had many smart and single people around who wanted to have a girl or boy friend but for some reason could not, I did not have the courage or time to invest in this.

How about Aunt Pythia, who has so many followers? I personally checked out some online dating environments, but it was so hard to find really sophisticated people and I did not feel like talking to all those people with the hope that one of them was the good looking nerd I was after.

Idea

Dear Idea,

I like your idea (har har!), but here’s the thing. If I started an online matchmaking thing, I’d first of all not restrict to “high-profile intellectuals,” and second of all it would be very very different from the stuff that already exists.

So for example I’m definitely of the opinion that knowing someone’s age, race, height, and weight and seeing a picture of them makes 99% of all people unfairly unattractive.

It’s a case of knowing the wrong thing about someone. I mean, I’m not saying that you don’t eventually know those things about someone you’re into, but you don’t focus on them if it’s an organic meeting. It’s just the wrong information to provide and makes things less sexy and painfully judgmental.

Let me say it this way. Some woman going online for a date might think she needs the man to be taller than she is, and filter stuff out that way, but in real life she’ll meet someone at a party and be really into him and later realize he’s probably a couple inches shorter than she is and she won’t care at all.

So what information would I ask people to provide instead? That’s a toughie, and I’d love your help, readers, but here’s a start:

- How sexual are you? (super important question)

- How much fun are you? (people are surprisingly honest when asked this)

- How awesome do you smell? (might need to invent technology for this one)

- What bothers you more: the big bank bailout or the idea of increasing the minimum wage?

- Do you like strong personalities or would you rather things stay polite?

- What do you love arguing about more: politics or aesthetics?

- Where would you love to visit if you could go anywhere?

- Do you want kids?

- Dog person or cat person?

- Do you sometimes wish the girl could be the hero, and not always fall for the hapless dude at the end?

That’s a start. Again, looking for more. I think there should be about 20. Also people should answer in sentences.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a graduate student in a STEM field who happens to also be of the male inclination….oh, and I’m gay.

Now, this normally isn’t so much of an issue (though it has been!) with my social circle/friends outside of the academia, but I’m a bit concerned about disclosing this sort of information to the department, my advisor, and other STEM graduate peers, because, well

- in my humble opinion, STEM departments are not the most gay friendly. I mean, if you’re a gay male, surely you should be studying creative writing or writing your thesis about continental philosophy’s role in post-WWII imperialism (honestly, the former has been said to me….though the latter sounds like an interesting blog post or two), and

- my main concern is the future of my academic career. Who are we kidding here, people making hiring decisions in the future may not be that cool with the whole “I’m here and queer!” thing. It could affect my career, negatively. (Ever been to Princeton btw?)

Please feel free to straightsplain to me that I’m being paranoid (though I won’t think I was being paranoid, would I?)

Best,

Sardonic Albeit Distinctly Fearful About Gay-friendliness

Dear SADFAG,

First of all, I have been to Princeton, thanks for asking.

Second of all, I don’t think you’re being at all paranoid. In fact it warms the cockles of my heart that you might even feel like you’re being paranoid asking about this, and it’s a testament to how far this country has come since I was a graduate student. Progress!

But only partial progress, to be sure. One of the weirdest things about the academic math market is how you’re expected to up and move to just about anywhere for a one year post-doc or what have you. And many people, especially outside of math, don’t actually want to do that, even if those places are nice places. When you add to that the fact that many of those places aren’t particularly nice, and are still crazy backwards when it comes to accepting gay people, then your job search is getting narrower.

Even so, you might want to take that job in that no-so-nice place, especially if it’s only for one year. I get that.

My short-term advice to you is to do what you need to do to keep your options wide, and if that includes coming out because you’re fed up with this bullshit, then definitely keep that in mind. My long-term advice is to end up eventually in a nice place where you can be accepted. Such places exist and the great news is they are increasing in number.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

The Lede Program has awesome faculty

A few weeks ago I mentioned that I’m the Program Director for the new Lede Program at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. I’m super excited to announce that I’ve found amazing faculty for the summer part of the program, including:

- Jonathan Soma, who will be the primary instructor for Basic Computing and for Algorithms

- Dennis Tenen, who will be helping Soma in the first half of the summer with Basic Computing

- Chris Wiggins, who will be helping Soma in the second half of the summer with Algorithms

- An amazing primary instructor for Databases who I will announce soon,

- Matthew Jones, who will help that amazing yet-to-be-announced instructor in Data and Databases

- Three amazing TA’s: Charles Berret, Sophie Chou, and Josh Vekhter (who doesn’t have a website!).