Archive

Why the NFL conversation about Ray Rice is so important to me

My first memory is of my father throwing a plate of eggs at my mother’s head, like a frisbee. My mother had to duck to get out of the way, and the plate exploded on the wall behind her. His eggs hadn’t been cooked well enough, and this was his way of expressing that to my mother, who had cooked them. Then he punched his hand through a glass window. Blood and glass fragments were everywhere. I was 4 years old. I remember running to my bed and crying, and the already familiar feeling of hiding in fear.

My mother was a battered woman who didn’t leave her abuser. And that meant a bunch of things for her and for me and my brother. I cannot explain her reasoning, because I was a small child when most of the abuse occurred. But I can tell you it’s common enough, and it’s not even that hard to understand.

One of the aspects of this decision – to stay with your abuser or not – that I haven’t been hearing a lot of recently, in this whole Ray Rice-inspired nationwide conversation about violence against women, is the economics of it. The worst of my father’s behavior happened when he was unemployed and desperately unhappy with how his life was turning out. Once he got on his feet again he didn’t take stuff out on his wife as much or as often. I imagine that is typical, but what it means is that it’s extra hard to imagine managing a second household, with small children, on one salary, when it’s already a huge struggle to manage one. The economic reality of leaving your husband has to be understood.

Even so, the abuse didn’t completely stop, and it’s not like my mother never considered leaving my father. I remember I went away for a month, to communist Budapest, when I was turning 13, the summer of 1985. When I came back my mother told me that my father had pushed her down the stairs. Then she asked me if she should leave him. I said yes, but then she didn’t do it.

I will probably never really forgive her for asking me that, for putting that kind of responsibility on a child like that, and then not following through. Especially now that I have kids of my own that age, it seems outrageous to put that kind of decision on their plate, or even seem to. It was my last day of childhood, the day I realized there were no responsible people in my family, and that I would have to step up and be the person who negotiated reasonable boundaries or, failing that, call the cops. From then on I was my mother and my brother’s protector.

If anyone ever asks me why I am not intimidated by anyone, I think of that moment. When you are a 13-year-old girl who has decided to stand up for your mother and brother against a large and very strong man, who often becomes an enraged and unreasonable bully, you forget about fear and intimidation, because it’s just something you cannot think about.

—

Many years later, after I left college, my father engaged me in a series of ritualized revisionist history lessons. Every Christmas, every Thanksgiving, maybe even on July 4th, he would bring up the bad old days and he’d mention how much I’d hated him when I was a teenager, and how he hadn’t deserved it, and how even when he’d been abusive to my mother, she had hit him first, and he hadn’t really wanted to do it but there it is. He often distorted facts, and he never explained why he was doing this.

It always sounded so bizarre to me – how could it matter that my mother had hit him first, not to mention that it was unbelievably hard to imagine? How could that be an excuse for what kind of fear and rage he had manifested on her body and on our family for so long? Answer: it isn’t an excuse.

It was very confusing, these inaccurate family history lessons in sermon form. It made me so angry I never could do anything except stay silent. I didn’t even correct him when he lied about the details, because he was evidently saying all of this more for him than for me.

It took me years to figure out why this conversation kept happening, but I think I finally know now. He was working through his guilt with me as his chosen audience. He was, in a sense, asking for my forgiveness. I never gave it, but what those conversations did accomplish for him was almost the same: he made it my problem for being so unkind as to not forgive him. After all, my mother had forgiven him, why couldn’t I? Looking back, I felt increasing pressure to forgive, but I never gave in. I didn’t even really know how.

Here’s why I’m thinking about this now. This Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson conversation, which I’ve been listening to on sports radio, has gotten me to thinking about this stuff. I am listening to these football guys, these pinnacles of macho masculinity, talking about men who abuse women and children, and describing it as unforgivable. Thank god for those men.

Because here’s the thing. It is unforgivable, but until now I hadn’t realized that I was allowed to think so. I’ve been feeling so guilty for so long at not being able to forgive my father, I never realized that I could just be okay with it. But now I do, and I don’t forgive him, and I never will.

—

After much deliberation, I’ve finally decided to publish this. To be clear, I’m not doing so to hurt my father or my mother. I’m writing it in hopes that by reading this, people will realize that this kind of thing happens everywhere, to all kinds of people, and that it’s always fucked up and wrong. We need to know that, the NFL needs to know that, and policy makers need to know that. We need to create stronger laws around this, that don’t buckle when the women refuse to press charges.

If this happened to you as a kid, it wasn’t your fault, and you don’t have to forgive if can’t or you don’t want to, and even if you don’t forgive them, you will probably still love them. Human beings are really good at conflicting emotions. Focus on not being like that yourself. My proudest accomplishment is that I have not perpetuated the cycle of violence on my own family. And good luck.

Christian Rudder’s Dataclysm

Here’s what I’ve spent the last couple of days doing: alternatively reading Christian Rudder’s new book Dataclysm and proofreading a report by AAPOR which discusses the benefits, dangers, and ethics of using big data, which is mostly “found” data originally meant for some other purpose, as a replacement for public surveys, with their carefully constructed data collection processes and informed consent. The AAPOR folk have asked me to provide tangible examples of the dangers of using big data to infer things about public opinion, and I am tempted to simply ask them all to read Dataclysm as exhibit A.

Rudder is a co-founder of OKCupid, an online dating site. His book mainly pertains to how people search for love and sex online, and how they represent themselves in their profiles.

Here’s something that I will mention for context into his data explorations: Rudder likes to crudely provoke, as he displayed when he wrote this recent post explaining how OKCupid experiments on users. He enjoys playing the part of the somewhat creepy detective, peering into what OKCupid users thought was a somewhat private place to prepare themselves for the dating world. It’s the online equivalent of a video camera in a changing booth at a department store, which he defended not-so-subtly on a recent NPR show called On The Media, and which was written up here.

I won’t dwell on that aspect of the story because I think it’s a good and timely conversation, and I’m glad the public is finally waking up to what I’ve known for years is going on. I’m actually happy Rudder is so nonchalant about it because there’s no pretense.

Even so, I’m less happy with his actual data work. Let me tell you why I say that with a few examples.

Who are OKCupid users?

I spent a lot of time with my students this summer saying that a standalone number wouldn’t be interesting, that you have to compare that number to some baseline that people can understand. So if I told you how many black kids have been stopped and frisked this year in NYC, I’d also need to tell you how many black kids live in NYC for you to get an idea of the scope of the issue. It’s a basic fact about data analysis and reporting.

When you’re dealing with populations on dating sites and you want to conclude things about the larger culture, the relevant “baseline comparison” is how well the members of the dating site represent the population as a whole. Rudder doesn’t do this. Instead he just says there are lots of OKCupid users for the first few chapters, and then later on after he’s made a few spectacularly broad statements, on page 104 he compares the users of OKCupid to the wider internet users, but not to the general population.

It’s an inappropriate baseline, made too late. Because I’m not sure about you but I don’t have a keen sense of the population of internet users. I’m pretty sure very young kids and old people are not well represented, but that’s about it. My students would have known to compare a population to the census. It needs to happen.

How do you collect your data?

Let me back up to the very beginning of the book, where Rudder startles us by showing us that the men that women rate “most attractive” are about their age whereas the women that men rate “most attractive” are consistently 20 years old, no matter how old the men are.

Actually, I am projecting. Rudder never actually specifically tells us what the rating is, how it’s exactly worded, and how the profiles are presented to the different groups. And that’s a problem, which he ignores completely until much later in the book when he mentions that how survey questions are worded can have a profound effect on how people respond, but his target is someone else’s survey, not his OKCupid environment.

Words matter, and they matter differently for men and women. So for example, if there were a button for “eye candy,” we might expect women to choose more young men. If my guess is correct, and the term in use is “most attractive”, then for men it might well trigger a sexual concept whereas for women it might trigger a different social construct; indeed I would assume it does.

Since this isn’t a porn site, it’s a dating site, we are not filtering for purely visual appeal; we are looking for relationships. We are thinking beyond what turns us on physically and asking ourselves, who would we want to spend time with? Who would our family like us to be with? Who would make us be attractive to ourselves? Those are different questions and provoke different answers. And they are culturally interesting questions, which Rudder never explores. A lost opportunity.

Next, how does the recommendation engine work? I can well imagine that, once you’ve rated Profile A high, there is an algorithm that finds Profile B such that “people who liked Profile A also liked Profile B”. If so, then there’s yet another reason to worry that such results as Rudder described are produced in part as a result of the feedback loop engendered by the recommendation engine. But he doesn’t explain how his data is collected, how it is prompted, or the exact words that are used.

Here’s a clue that Rudder is confused by his own facile interpretations: men and women both state that they are looking for relationships with people around their own age or slightly younger, and that they end up messaging people slightly younger than they are but not many many years younger. So forty year old men do not message twenty year old women.

Is this sad sexual frustration? Is this, in Rudder’s words, the difference between what they claim they want and what they really want behind closed doors? Not at all. This is more likely the difference between how we live our fantasies and how we actually realistically see our future.

Need to control for population

Here’s another frustrating bit from the book: Rudder talks about how hard it is for older people to get a date but he doesn’t correct for population. And since he never tells us how many OKCupid users are older, nor does he compare his users to the census, I cannot infer this.

Here’s a graph from Rudder’s book showing the age of men who respond to women’s profiles of various ages:

We’re meant to be impressed with Rudder’s line, “for every 100 men interested in that twenty year old, there are only 9 looking for someone thirty years older.” But here’s the thing, maybe there are 20 times as many 20-year-olds as there are 50-year-olds on the site? In which case, yay for the 50-year-old chicks? After all, those histograms look pretty healthy in shape, and they might be differently sized because the population size itself is drastically different for different ages.

Confounding

One of the worst examples of statistical mistakes is his experiment in turning off pictures. Rudder ignores the concept of confounders altogether, which he again miraculously is aware of in the next chapter on race.

To be more precise, Rudder talks about the experiment when OKCupid turned off pictures. Most people went away when this happened but certain people did not:

Some of the people who stayed on went on a “blind date.” Those people, which Rudder called the “intrepid few,” had a good time with people no matter how unattractive they were deemed to be based on OKCupid’s system of attractiveness. His conclusion: people are preselecting for attractiveness, which is actually unimportant to them.

But here’s the thing, that’s only true for people who were willing to go on blind dates. What he’s done is select for people who are not superficial about looks, and then collect data that suggests they are not superficial about looks. That doesn’t mean that OKCupid users as a whole are not superficial about looks. The ones that are just got the hell out when the pictures went dark.

Race

This brings me to the most interesting part of the book, where Rudder explores race. Again, it ends up being too blunt by far.

Here’s the thing. Race is a big deal in this country, and racism is a heavy criticism to be firing at people, so you need to be careful, and that’s a good thing, because it’s important. The way Rudder throws it around is careless, and he risks rendering the term meaningless by not having a careful discussion. The frustrating part is that I think he actually has the data to have a very good discussion, but he just doesn’t make the case the way it’s written.

Rudder pulls together stats on how men of all races rate women of all races on an attractiveness scale of 1-5. It shows that non-black men find their own race attractive and non-black men find black women, in general, less attractive. Interesting, especially when you immediately follow that up with similar stats from other U.S. dating sites and – most importantly – with the fact that outside the U.S., we do not see this pattern. Unfortunately that crucial fact is buried at the end of the chapter, and instead we get this embarrassing quote right after the opening stats:

And an unintentionally hilarious 84 percent of users answered this match question:

Would you consider dating someone who has vocalized a strong negative bias toward a certain race of people?

in the absolute negative (choosing “No” over “Yes” and “It depends”). In light of the previous data, that means 84 percent of people on OKCupid would not consider dating someone on OKCupid.

Here Rudder just completely loses me. Am I “vocalizing” a strong negative bias towards black women if I am a white man who finds white women and asian women hot?

Especially if you consider that, as consumers of social platforms and sites like OKCupid, we are trained to rank all the products we come across to ultimately get better offerings, it is a step too far for the detective on the other side of the camera to turn around and point fingers at us for doing what we’re told. Indeed, this sentence plunges Rudder’s narrative deeply into the creepy and provocative territory, and he never fully returns, nor does he seem to want to. Rudder seems to confuse provocation for thoughtfulness.

This is, again, a shame. A careful conversation about the issues of what we are attracted to, what we can imagine doing, and how we might imagine that will look to our wider audience, and how our culture informs those imaginings, are all in play here, and could have been drawn out in a non-accusatory and much more useful way.

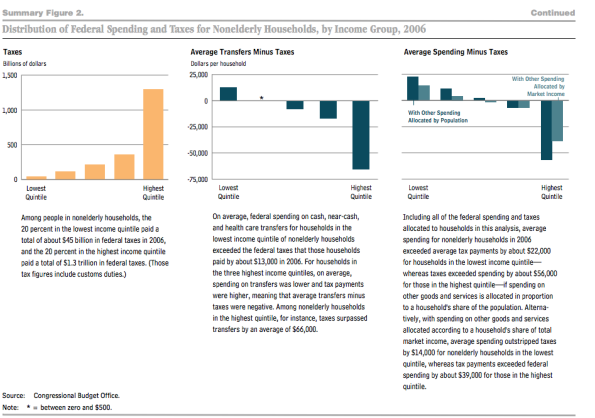

Distributional Economic Health

I am pushing an unusual way of considering economic health. I call it “distributional thinking.” It requires that you not aggregate everything into one statistic, but rather take a few samples from different parts of the distribution and consider things from those different perspectives.

So instead of saying “things are great because the economy has expanded at a rate of 4%” I’d like us to think about more individual definitions of “great.”

For example, it’s a good time to be rich right now. Really good. The stock market keeps hitting all-time highs, the jobs market is great in tech, and it’s still absolutely possible to hide wealth in off-shore tax havens.

It’s not so good to be middle class. Wages are stagnant and have been forever, and jobs are drying up due to automation and a lack of even maintenance-level infrastructure work. Colleges are super expensive, and the best the government can do is fiddle around the edges with interest rates.

It’s a really bad time to be poor in this country. Jobs are hard to find and conditions are horrible. There are more and more arrests for petty crimes as the violent crime rate goes down. Those petty crime arrests lead to big fees and sometimes jail time if you can’t pay the fee. Look at Ferguson as an example of what this kind of frustration this can lead to.

Once you are caught in the court system, private probation companies act as abusive debt collectors, and nobody controls their fees, which can be outrageous. To be clear, we let this happen in the name of saving money: private for-profit companies like this guarantee that they won’t cost anything to the local government because they make the people on probation pay for services.

And even though that’s an outrageous and predatory system, it’s not likely to go away. Once they are officially branded as criminals, the poor often lose their voting rights, which means they have little political recourse to protect themselves. On the flip side, they are largely silent about their struggles for the same reason.

Once you think about our economic health this way, you realize how comparatively meaningless the GDP is. It is no longer a good proxy to true economic health, where all classes would be more or less better off as it went up.

And until we get on the same page, where we all go up and down together, it is a mathematical fact that no one statistic could possibly capture the progress we are or are not making. Instead, we need to think distributionally.

The bad teacher conspiracy

Any time I see an article about the evaluation system for teachers in New York State, I wince. People get it wrong so very often. Yesterday’s New York Times article written by Elizabeth Harris was even worse than usual.

First, her wording. She mentioned a severe drop in student reading and math proficiency rates statewide and attributed it to a change in the test to the Common Core, which she described as “more rigorous.”

The truth is closer to “students were tested on stuff that wasn’t in their curriculum.” And as you can imagine, if you are tested on stuff you didn’t learn, your score will go down (the Common Core has been plagued by a terrible roll-out, and the timing of this test is Exhibit A). Wording like this matters, because Harris is setting up her reader to attribute the falling scores to bad teachers.

Harris ends her piece with a reference to a teacher-tenure lawsuit: ‘In one of those cases, filed in Albany in July, court documents contrasted the high positive teacher ratings with poor student performance, and called the new evaluation system “deficient and superficial.” The suit said those evaluations were the “most highly predictive measure of whether a teacher will be awarded tenure.”’

In other words, Harris is painting a picture of undeserving teachers sneaking into tenure in spite of not doing their job. It’s ironic, because I actually agree with the statement that the new evaluation system is “deficient and superficial,” but in my case I think it is overly punitive to teachers – overly random, really, since it incorporates the toxic VAM model – but in her framing she is implying it is insufficiently punitive.

Let me dumb Harris’s argument down even further: How can we have 26% English proficiency among students and 94% effectiveness among teachers?! Let’s blame the teachers and question the legitimacy of tenure.

Indeed, after reading the article I felt like looking into whether Harris is being paid by David Welch, the Silicon Valley dude who has vowed to fight teacher tenure nationwide. More likely she just doesn’t understand education and is convinced by simplistic reasoning.

In either case, she clearly needs to learn something about statistics. For that matter, so do other people who drag out this “blame the teacher” line whenever they see poor performance by students.

Because here’s the thing. Beyond obvious issues like switching the content of the tests away from the curriculum, standardized test scores everywhere are hugely dependent on the poverty levels of students. Some data:

It’s not just in this country, either:

The conclusion is that, unless you think bad teachers have somehow taken over poor schools everywhere and booted out the good teachers, and good teachers have taken over rich schools everywhere and booted out the bad teachers (which is supposed to be impossible, right?), poverty has much more of an effect than teachers.

Just to clarify this reasoning, let me give you another example: we could blame bad journalists for lower rates of newspaper readership at a given paper, but since newspaper readership is going down everywhere we’d be blaming journalists for what is a cultural issue.

Or, we could develop a process by which we congratulate specific policemen for a reduced crime rate, but then we’d have to admit that crime is down all over the country.

I’m not saying there aren’t bad teachers, because I’m sure there are. But by only focusing on rooting out bad teachers, we are ignoring an even bigger and harder problem. And no, it won’t be solved by privatizing and corporatizing public schools. We need to address childhood poverty. Here’s one more visual for the road:

Weapon of Math Destruction: “risk-based” sentencing models

There was a recent New York Times op-ed by Sonja Starr entitled Sentencing, by the Numbers (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg and Linda Brown) which described the widespread use – in 20 states so far and growing – of predictive models in sentencing.

The idea is to use a risk score to help inform sentencing of offenders. The risk is, I guess, supposed to tell us how likely the person is to commit another act in the future, although that’s not specified. From the article:

The basic problem is that the risk scores are not based on the defendant’s crime. They are primarily or wholly based on prior characteristics: criminal history (a legitimate criterion), but also factors unrelated to conduct. Specifics vary across states, but common factors include unemployment, marital status, age, education, finances, neighborhood, and family background, including family members’ criminal history.

I knew about the existence of such models, at least in the context of prisoners with mental disorders in England, but I didn’t know how widespread it had become here. This is a great example of a weapon of math destruction and I will be using this in my book.

A few comments:

- I’ll start with the good news. It is unconstitutional to use information such as family member’s criminal history against someone. Eric Holder is fighting against the use of such models.

- It is also presumably unconstitutional to jail someone longer for being poor, which is what this effectively does. The article has good examples of this.

- The modelers defend this crap as “scientific,” which is the worst abuse of science and mathematics imaginable.

- The people using this claim they only use it for as a way to mitigate sentencing, but letting a bunch of rich white people off easier because they are not considered “high risk” is tantamount to sentencing poor minorities more.

- It is a great example of confused causality. We could easily imagine a certain group that gets arrested more often for a given crime (poor black men, marijuana possession) just because the police have that practice for whatever reason (Stop & Frisk). Then model would then consider any such man at a higher risk of repeat offending, but that’s not because any particular person is actually more likely to do it, but because the police are more likely to arrest that person for it.

- It also creates a negative feedback loop on the most vulnerable population: the model will impose longer sentencing on the population it considers most risky, which will in turn make them even riskier in the future, if “length of time in prison previously” is used as an attribute in the model, which is surely is.

- Not to be cynical, but considering my post yesterday, I’m not sure how much momentum will be created to stop the use of such models, considering how discriminatory it is.

- Here’s an extreme example of preferential sentencing which already happens: rich dude Robert H Richards IV raped his 3-year-old daughter and didn’t go to jail because the judge ruled he “wouldn’t fare well in prison.”

- How great would it be if we used data and models to make sure rich people went to jail just as often and for just as long as poor people for the same crime, instead of the other way around?

White people don’t talk about racism

Here’s what comes up in conversations at my Occupy meetings a lot: systemic racism.

Maybe once a week on average, whether we are talking about the criminal justice system, or the court system, or the educational system, or standardized tests, or chronic employment problems, or welfare rhetoric, or homelessness. There are many very well-informed people in my group which can speak eloquently and convincingly about how the system itself, not any particular person (although they do exist), discriminates against minorities in this country.

As a group we cheered when Ta-Nehisi Coates came out with his Atlantic piece entitled The Case for Reparations. So much resonated, especially the parts about widespread reverse redlining of mortgages to minorities in the run-up to the credit crisis. And it finally taught me how to think about affirmative action.

Another thing that comes up sometimes, although less often: how white people, even liberals like Elizabeth Warren, don’t talk about racism anymore. They want to address education inequalities through class-based or income-based measures rather than race-based ones. They talk about unemployment and joblessness and the need for criminal justice reform without referring to the enormous and glaring racial disparities.

I’m left feeling a lot like I felt in 7th grade social studies when we studied the period of mass genocide of American Indians and called it “Manifest Destiny.”

This recent study entitled Racial Disparities in Incarceration Increase Acceptance of Punitive Policies might explain why white people are so reluctant to talk about racism. Namely, because white react strangely when you specifically point out systemic racism (they are OK with it).

So in other words, if you tell them how many people are incarcerated in this country compared to other countries, they think it’s terrible and we should stop putting so many people in jail. But if you tell them most of those prisoners (60% in New York City) are black, then they’re less likely to think it’s terrible. They also remember the number wrong, thinking it’s higher than it is. Here’s a succinct summary from this Vox article:

The question seems to be which instinct wins out: the belief that our prison system isn’t fair, or the assumption that a prisoner must be a criminal. According to the study, when whites are primed to think of prisoners as black, it’s the latter that wins out.

The conclusion of the Vox article is this: politicians and activists have figured out that, if they want to agitate for criminal justice reform, they can’t mention systemically racist unfairness, because that just doesn’t upset powerful people enough. Instead, they need to focus on important stuff like saving money, which is how you get white people people up in arms. That’s what flies in the focus groups, apparently.

It explains why Elizabeth Warren doesn’t talk about race when she talks about student loans, preferring to talk about “young people”, even though the problem is worse for non-Asian minorities. Similarly, Obama is targeting for-profit colleges without reference to race (but with reference to veterans!) even though for-profit colleges notoriously target minorities.

The problem with understanding stuff like this is that it’s primarily used to be politically cunning, which is not enough. I’d like to talk about how to get people to directly confront racism, starting with liberals.

You used to be a feminist before you got pregnant

Today I’d like to rant about a pattern I’ve noticed.

Namely, I have a bunch of female friends and acquaintances that I consider feisty, informed, and argumentative sorts. People who are fun to be around and who know how to stick up for themselves, know how to spot misogyny and paternalism in all contexts, and most of all know how to dismiss such nonsense when it appears, and then get on with whatever they were doing.

And then they get pregnant and the lose most if not all of those properties. They get doctors who tell them what to eat, and how much, even though they’ve been doing quite well feeding themselves for 30 odd years without help. They get doctors who tell them how much pain killers they should have during labor, when it’s months and months before labor and we don’t even know what’s gonna happen. What gives?

Here’s a guess. Partly it’s the baby hormones that make you generally confused when you’re pregnant. The other part is that the stakes are high, and you are not an expert, so you defer to your baby doctor. Plus there’s all those ridiculous and scary pregnancy books out there which just serve to make women neurotic and should be burned. Oh and sometimes the doctors are women so they don’t seem paternalistic. But that’s what it is:

But here’s the thing, there’s not much evidence about exactly how you should eat when you’re pregnant, unless you are doing something absolutely weird. And, in spite of what a no-drugs doctor might suggest, it’s not all that dangerous to babies to have pain meds. In fact it’s super safe to have a baby now compared to the past, both for you and and your baby. And thank goodness for that.

On the flip side, a doctor has no business dictating to you that you will have an epidural either, which is what happened to my mom back in the 1970’s. It’s really your choice, and you should decide.

So if you have one of those pushy-ass doctors, fuck ’em. This is your body, you get to decide that stuff. Go get a new doctor.

And to be sure, I’m not saying you shouldn’t inform yourself about risks and signs of pre-eclampsia and other truly important stuff, but for goodness sakes don’t forget your feminist training. It’s not just your baby here, it’s also you, and yes you deserve to eat food you want to eat and to moderate pain if it gets overwhelming. You will be happier, your baby will be just fine, and she or he won’t remember a thing. Consider it training for how to be a mom later.

The problem with charter schools

Today I read this article written by Allie Gross (hat tip Suresh Naidu), a former Teach for America teacher whose former idealism has long been replaced by her experiences in the reality of education in this country. Her article is entitled The Charter School Profiteers.

It’s really important, and really well written, and just one of the articles in the online magazine Jacobin that I urge you to read and to subscribe to. In fact that article is part of a series (here’s another which focuses on charter schools in New Orleans) and it comes with a booklet called Class Action: An Activist Teacher’s Handbook. I just ordered a couple of hard copies.

I’d really like you to read the article, but as a teaser here’s one excerpt, a rant which she completely backs up with facts on the ground:

You haven’t heard of Odeo, the failed podcast company the Twitter founders initially worked on? Probably not a big deal. You haven’t heard about the failed education ventures of the person now running your district? Probably a bigger deal.

When we welcome schools that lack democratic accountability (charter school boards are appointed, not elected), when we allow public dollars to be used by those with a bottom line (such as the for-profit management companies that proliferate in Michigan), we open doors for opportunism and corruption. Even worse, it’s all justified under a banner of concern for poor public school students’ well-being.

While these issues of corruption and mismanagement existed before, we should be wary of any education reformer who claims that creating an education marketplace is the key to fixing the ills of DPS or any large city’s struggling schools. Letting parents pick from a variety of schools does not weed out corruption. And the lax laws and lack of accountability can actually exacerbate the socioeconomic ills we’re trying to root out.

You are not Google’s customer

I’m going to write one of those posts where many of you will already understand my point. In fact it might be old hat for a majority of my readers, yet it’s still important enough for me to mention just in case there are a few people out there who don’t know how the modern business model is set up.

Namely, like this. As a gmail and Google Search user, you are not a customer of Google. You are the product. The customers of Google are the ones who advertise to you. Your interaction with Google is, from the perspective of the business operation, that you give them information which they harvest so they can advertise to you in a more targeted way, thus increasing the likelihood of you clicking. The fact that you get a service from these interactions is great, because it means you’ll come back to give Google and its customers more information about you soon.

This misunderstanding, once you see it as such, can be clarifying. For example, when people talk about anti-trust and Google, they should talk about whether the customers of Google have any other serious choice. And since the customers of Google are advertisers, not gmailers or searchers, the alternatives aren’t hotmail or Bing. Rather they are other advertising outlets. And a very good case can be made that Google does violate anti-trust laws in that sense, just ask Nathan Newman.

It also explains why something like the recent European “right to be forgotten” law seems so strange and unreasonable to the powers that be at Google. It’d be like a meat farm where the cows go on strike and demand better food. Cows are the product, and they aren’t supposed to complain. They’re not even supposed to be heard. At worst we treat them better when our customers demand it, not when the cows do.

I was reminded about this ubiquitous business model yesterday, and newly enraged by its consequences, when reading this article entitled Held Captive by Flawed Credit Reports (hat tip Linda Brown) about the credit score agency Experian and how they utterly disregard the laws trying to protect consumers from mistakes in their credit reports. The problem here is that, to the giant company Experian, its customers are giant companies like Verizon which send credit score requests millions of times a day and pay for each score. Mere people, whose mortgage application is being denied because of mistakes, are the product, not the customer, and they are almost by definition unimportant.

And it seems that the law which is supposed to protect these people, namely the Fair Credit Reporting Act, first passed in 1970, doesn’t have enough teeth behind it to make the big credit scoring agencies sit up and pay attention. It’s all about the scale of the fines compare to the scale of the business. This is well explained in the article (emphasis mine):

Last year, the Federal Trade Commission found that 5 percent of consumers — or an estimated 10 million people — had an error on one of their credit reports that could have resulted in higher borrowing costs.

The F.T.C., which oversees the industry along with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has been busy bringing cases in this arena. Since 2000, it has filed 18 enforcement actions against reporting bureaus; 13 were district court actions that generated $25.7 million in penalties.

Consumers have also won in the courts, on occasion. Last year, an Oregon consumer was awarded $18.4 million in punitive damages by a jury after she sued Equifax for inserting errors into her credit report. But the fines, settlements and judgments paid by the larger companies are not even close to a rounding error. Experian generated $4.8 billion in revenue for the year ended March 2014, and its after-tax profit of $747 million in the period was more than twice its 2013 figure.

Million versus billion. It seems like the cows don’t have much leverage.

I am boycotting Amazon

I have been doing some reading about the Amazon/ Hachette battle and I have come to the conclusion that Amazon has become a huge bully. I also wasn’t impressed by how they treat employees, how they monitor and surveil them, and a host of other problems. For that reason I’m boycotting Amazon for my shopping as well as my blogging habits, so no more direct links.

Update: I’m actually still going to use their EC2 services as part of the Lede Program. Not sure how to avoid that actually, and I’d welcome suggestions.

No, Sandy Pentland, let’s not optimize the status quo

It was bound to happen. Someone was inevitably going to have to write this book, entitled Social Physics, and now someone has just up and done it. Namely, Alex “Sandy” Pentland, data scientist evangelist, director of MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, and co-founder of the MIT Media Lab.

A review by Nicholas Carr

This article entitled The Limits of Social Engineering, published in MIT’s Technology Review and written by Nicholas Carr (hat tip Billy Kaos) is more or less a review of the book. From the article:

Pentland argues that our greatly expanded ability to gather behavioral data will allow scientists to develop “a causal theory of social structure” and ultimately establish “a mathematical explanation for why society reacts as it does” in all manner of circumstances. As the book’s title makes clear, Pentland thinks that the social world, no less than the material world, operates according to rules. There are “statistical regularities within human movement and communication,” he writes, and once we fully understand those regularities, we’ll discover “the basic mechanisms of social interactions.”

By collecting all the data – credit card, sensor, cell phones that can pick up your moods, etc. – Pentland seems to think we can put the science into social sciences. He thinks we can predict a person like we now predict planetary motion.

OK, let’s just take a pause here to say: eeeew. How invasive does that sound? And how insulting is its premise? But wait, it gets way worse.

The next think Pentland wants to do is use micro-nudges to affect people’s actions. Like paying them to act a certain way, and exerting social and peer pressure. It’s like Nudge in overdrive.

Vomit. But also not the worst part.

Here’s the worst part about Pentland’s book, from the article:

Ultimately, Pentland argues, looking at people’s interactions through a mathematical lens will free us of time-worn notions about class and class struggle. Political and economic classes, he contends, are “oversimplified stereotypes of a fluid and overlapping matrix of peer groups.” Peer groups, unlike classes, are defined by “shared norms” rather than just “standard features such as income” or “their relationship to the means of production.” Armed with exhaustive information about individuals’ habits and associations, civic planners will be able to trace the full flow of influences that shape personal behavior. Abandoning general categories like “rich” and “poor” or “haves” and “have-nots,” we’ll be able to understand people as individuals—even if those individuals are no more than the sums of all the peer pressures and other social influences that affect them.

Kill. Me. Now.

The good news is that the author of the article, Nicholas Carr, doesn’t buy it, and makes all sorts of reasonable complaints about this theory, like privacy concerns, and structural sources of society’s ills. In fact Carr absolutely nails it (emphasis mine):

Pentland may be right that our behavior is determined largely by social norms and the influences of our peers, but what he fails to see is that those norms and influences are themselves shaped by history, politics, and economics, not to mention power and prejudice. People don’t have complete freedom in choosing their peer groups. Their choices are constrained by where they live, where they come from, how much money they have, and what they look like. A statistical model of society that ignores issues of class, that takes patterns of influence as givens rather than as historical contingencies, will tend to perpetuate existing social structures and dynamics. It will encourage us to optimize the status quo rather than challenge it.

How to see how dumb this is in two examples

This brings to mind examples of models that do or do not combat sexism.

First, the orchestra audition example: in order to avoid nepotism, they started making auditioners sit behind a sheet. The result has been way more women in orchestras.

This is a model, even if it’s not a big data model. It is the “orchestra audition” model, and the most important thing about this example is that they defined success very carefully and made it all about one thing: sound. They decided to define the requirements for the job to be “makes good sounding music” and they decided that other information, like how they look, would be by definition not used. It is explicitly non-discriminatory.

By contrast, let’s think about how most big data models work. They take historical information about successes and failures and automate them – rather than challenging their past definition of success, and making it deliberately fair, they are if anything codifying their discriminatory practices in code.

My standard made-up example of this is close to the kind of thing actually happening and being evangelized in big data. Namely, a resume sorting model that helps out HR. But, using historical training data, this model notices that women don’t fare so well historically at a the made-up company as computer programmers – they often leave after only 6 months and they never get promoted. A model will interpret that to mean they are bad employees and never look into structural causes. And moreover, as a result of this historical data, it will discard women’s resumes. Yay, big data!

Thanks, Pentland

I’m kind of glad Pentland has written such an awful book, because it gives me an enemy to rail against in this big data hype world. I don’t think most people are as far on the “big data will solve all our problems” spectrum as he is, but he and his book present a convenient target. And it honestly cannot surprise anyone that he is a successful white dude as well when he talks about how big data is going to optimize the status quo if we’d just all wear sensors to work and to bed.

Guest rant about rude kids

Today’s guest post was written by Amie, who describes herself as a mom of a 9 and a 14-year-old, mathematician, and bigmouth.

Nota bene: this was originally posted on Facebook as a spontaneous rant. Please don’t miscontrue it as an academic argument.

Time for a rant. I’ll preface this by saying that while my kids are creative, beautiful souls, so are many (perhaps all) children I’ve met, and it would be the height of arrogance to take credit for that as a parent. But one thing my husband and I can take credit for are their good manners, because that took work to develop.

The first phrase I taught me daughter was “thank you,” and it’s been put to good use over the years. I’m also loathe to tell other parents what to do, but this is an exception: teach your fucking kids to say “please” and “thank you”. If you are fortunate to visit another country, teach them to say “please” and “thank you” in the native language.

After a week in paradise at a Club Med in Mexico, I’m at some kind of breaking point with rude rich people and their spoiled kids. And that includes the Europeans. Maybe especially the Europeans. What is it that when you’re in France everyone’s all “thank you and have a nice day” but when these petit bourgeois assholes come to Cancun they treat Mexicans like nonhumans? My son held the door for a face-lifted Russian lady today who didn’t even say thank you.

Anyway, back to kids: I’m not saying that you should suppress your kids’ nature joie de vivre and boisterous, rambunctious energy (though if that’s what they’re like, please keep them away from adults who are not in the mood for it). Just teach them to treat other people with basic respect and courtesy. That means prompting them to say “please,” “thank you,” and “nice to meet you” when they interact with other people.

Jordan Ellenberg just posted how a huge number of people accepted to the math Ph.D. program at the University of Wisconsin never wrote to tell him that they had accepted other offers. When other people are on a wait list!

Whose fault is this? THE PARENTS’ FAULT. Damn parents. Come on!!

P.S. Those of you who have put in the effort to raise polite kids: believe me, I’ve noticed. So has everyone else.

Let’s experiment more

What is an experiment?

The gold standard in scientific fields is the randomized experiment. That’s when you have some “treatment” you want to impose on some population and you want to know if that treatment has positive or negative effects. In a randomized experiment, you randomly divide a population into a “treatment” group and a “control group” and give the treatment only to the first group. Sometimes you do nothing to the control group, sometimes you give them some other treatment or a placebo. Before you do the experiment, of course, you have to carefully define the population and the treatment, including how long it lasts and what you are looking out for.

Example in medicine

So for example, in medicine, you might take a bunch of people at risk of heart attacks and ask some of them – a randomized subpopulation – to take aspirin once a day. Note that doesn’t mean they all will take an aspirin every day, since plenty of people forget to do what they’re told to do, and even what they intend to do. And you might have people in the other group who happen to take aspirin every day even though they’re in the other group.

Also, part of the experiment has to be well-defined lengths and outcomes of the experiment: after, say, 10 years, you want to see how many people in each group have a) had heart attacks and b) died.

Now you’re starting to see that, in order for such an experiment to yield useful information, you’d better make sure the average age of each subpopulation is about the same, which should be true if they were truly randomized, and that there are plenty of people in each subpopulation, or else the results will be statistically useless.

One last thing. There are ethics in medicine, which make experiments like the one above fraught. Namely, if you have a really good reason to think one treatment (“take aspirin once a day”) is better than another (“nothing”), then you’re not allowed to do it. Instead you’d have to compare two treatments that are thought to be about equal. This of course means that, in general, you need even more people in the experiment, and it gets super expensive and long.

So, experiments are hard in medicine. But they don’t have to be hard outside of medicine! Why aren’t we doing more of them when we can?

Swedish work experiment

Let’s move on to the Swedes, who according to this article (h/t Suresh Naidu) are experimenting in their own government offices on whether working 6 hours a day instead of 8 hours a day is a good idea. They are using two different departments in their municipal council to act as their “treatment group” (6 hours a day for them) and their “control group” (the usual 8 hours a day for them).

And although you might think that the people in the control group would object to unethical treatment, it’s not the same thing: nobody thinks your life is at stake for working a regular number of hours.

The idea there is that people waste their last couple of hours at work and generally become inefficient, so maybe knowing you only have 6 hours of work a day will improve the overall office. Another possibility, of course, is that people will still waste their last couple of hours of work and get 4 hours instead of 6 hours of work done. That’s what the experiment hopes to measure, in addition to (hopefully!) whether people dig it and are healthier as a result.

Non-example in business: HR

Before I get too excited I want to mention the problems that arise with experiments that you cannot control, which is most of the time if you don’t plan ahead.

Some of you probably ran into an article from the Wall Street Journal, entitled Companies Say No to Having an HR Department. It’s about how some companies decided that HR is a huge waste of money and decided to get rid of everyone in that department, even big companies.

On the one hand, you’d think this is a perfect experiment: compare companies that have HR departments against companies that don’t. And you could do that, of course, but you wouldn’t be measuring the effect of an HR department. Instead, you’d be measuring the effect of a company culture that doesn’t value things like HR.

So, for example, I would never work in a company that doesn’t value HR, because, as a woman, I am very aware of the fact that women get sexually harassed by their bosses and have essentially nobody to complain to except HR. But if you read the article, it becomes clear that the companies that get rid of HR don’t think from the perspective of the harassed underling but instead from the perspective of the boss who needs help firing people. From the article:

When co-workers can’t stand each other or employees aren’t clicking with their managers, Mr. Segal expects them to work it out themselves. “We ask senior leaders to recognize any potential chemistry issues” early on, he said, and move people to different teams if those issues can’t be resolved quickly.

Former Klick employees applaud the creative thinking that drives its culture, but say they sometimes felt like they were on their own there. Neville Thomas, a program director at Klick until 2013, occasionally had to discipline or terminate his direct reports. Without an HR team, he said, he worried about liability.

“There’s no HR department to coach you,” he said. “When you have an HR person, you have a point of contact that’s confidential.”

Why does it matter that it’s not random?

Here’s the crucial difference between a randomized experiment and a non-randomized experiment. In a randomized experiment, you are setting up and testing a causal relationship, but in a non-randomized experiment like the HR companies versus the no-HR companies, you are simply observing cultural differences without getting at root causes.

So if I notice that, at the non-HR companies, they get sued for sexual harassment a lot – which was indeed mentioned in the article as happening at Outback Steakhouse, a non-HR company – is that because they don’t have an HR team or because they have a culture which doesn’t value HR? We can’t tell. We can only observe it.

Money in politics experiment

Here’s an awesome example of a randomized experiment to understand who gets access to policy makers. In an article entitled A new experiment shows how money buys access to Congress, an experiment was conducted by two political science graduate students, David Broockman and Josh Kalla, which they described as follows:

In the study, a political group attempting to build support for a bill before Congress tried to schedule meetings between local campaign contributors and Members of Congress in 191 congressional districts. However, the organization randomly assigned whether it informed legislators’ offices that individuals who would attend the meetings were “local campaign donors” or “local constituents.”

The letters were identical except for those two words, but the results were drastically different, as shown by the following graphic:

Conducting your own experiments with e.g. Mechanical Turk

You know how you can conduct experiments? Through an Amazon service called Mechanical Turk. It’s really not expensive and you can get a bunch of people to fill out surveys, or do tasks, or some combination, and you can design careful experiments and modify them and rerun them at your whim. You decide in advance how many people you want and how much to pay them.

So for example, that’s how then-Wall Street Journal journalist Julia Angwin, in 2012, investigated the weird appearance of Obama results interspersed between other search results, but not a similar appearance of Romney results, after users indicated party affiliation.

Conclusion

We already have a good idea of how to design and conduct useful and important experiments, and we already have good tools to do them. Other, even better tools are being developed right now to improve our abilities to conduct faster and more automated experiments.

If we think about what we can learn from these tools and some creative energy into design, we should all be incredibly impatient and excited. And we should also think of this as an argumentation technique: if we are arguing about whether a certain method or policy works versus another method or policy, can we set up a transparent and reproducible experiment to test it? Let’s start making science apply to our lives.

People who obsessively exercise are boring

I’m not saying anything you don’t know already. I’m just stating the obvious: people who obsessively exercise are super boring. They talk all the time about their times, and their workout progress, and their aching muscles, and it’s like you don’t even have to be there, you could just replace yourself with a gadget that listens, nods, and then says encouraging things like, “Way to go!” at the very end. Excruciating.

Look, don’t get me wrong. I’ve gone through bouts of obsessive exercise myself, and those bouts sometimes were pretty lengthy. And no, it didn’t ever make me skinny, just incredibly fit. I remember I trained for a sprint triathlon once, and man was I fit by the time it finally happened in the spring on 2004.

But then, when I got to the starting line, and there I was wishing I could reorder the events so the the beginning swim would 5 kilometers and the run at the end were a quarter mile – I’ve never been much of a runner – and I just looked around at myself and everyone else there, and I wondered how I’d become so incredibly boring and self-obsessed that I had paid good money and driven miles and miles just to obsessively exercise in front of other people.

What was going on with me? I became increasingly disgusted by my own boringness throughout the race. I think the worst part was how many people said “You go, girl!” when I jogged by. They were trying to encourage the fat girl, I get it, but it made it even more obvious that I was doing something that I honestly didn’t need to be getting public response to.

Look, I’m not against exercise, and I love doing it, or at least I love having done it because it makes you feel good, and I encourage everyone to be fit and happy. But I’m serious when I say I will no longer tolerate hanging out with people who obsess over it and want to talk to me about their obsession. Too frigging boring, people!

So if someone mentions that they went biking over this gorgeous spring weekend, then awesome, I’ll be happy for them. But if they want to talk about which bike they used, and what their time around Central Park was, and how they’re training for this or that event, then no. I will tell them “sorry but can we talk about something not incredibly boring now?”

Why do I mention this today? Because I finally figured out what my hostility towards the Quantified Self crowd is, and it’s this same thing. All those gadgets and doodads are essentially props to pull out and use to have that same boring conversation that I’ve already refused to give into. So please, don’t show me your sleep tracker or your step monitor and expect me to care. I don’t care.

And don’t get me wrong – again – I know some people will benefit from that kind of thing. And some people actually have illnesses or physical therapy and exercise and particularly quantified exercise might particularly help them keep track of their health! I get it!

But let’s face it, most people are not doing this for health. They are doing it for some other weird, narcissistic and anxiety-shielding coping-mechanistic self-competitive (or outright competitive) reason. And again, I’m not hating on them exactly, because I get it, and I’ve been there. But I don’t want to talk about it with them.

Let’s stop talking about HFT for a little while

It’s unusual that I find myself in the position of defending Wall Street activities, but here goes.

I just don’t think HFT is that big of a deal relative to other Wall Street evils. I have written a couple of times about HFT and I’m not a huge fan, and I don’t buy the “liquidity is good and more liquidity is better” argument: at some point enough is enough. I do think that day-to-day investors have largely benefitted from it but that people whose money is in massive funds which are regularly traded have seen their money get skimmed every month. Overall it’s a smallish negative tax on the average person, I’d expect.

Here’s why HFT deserves some of our hatred: there’s way too much human resources going into this stuff and it’s embarrassing, what with the laying of cables and blasting through mountains and such. And it’s a great sociological look into the absolutely greed-led mindset of the Wall Street trader, but honestly I think we already had that. It’s really business as usual at a microscopic scale, and nobody should really be surprised to learn that people will do anything to make money that’s technically possible and technically legal, and that they will brag about how they’re making the world a better place while they do it. Same old same old.

So I’m not saying HFT is awesome and we should encourage more of it. I’m all for thinking about how to slow down trading to once a second and make it “more fair” for more players (although that’s hard to do even as a thought experiment), or taxing transaction to make things slow down by themselves, which would be easy.

But here’s the thing, it’s not some huge awful thing we should focus on, even though Michael Lewis is a really good and engaging writer.

You wanna focus on something? Let’s talk about money laundering in HSBC and now Citi that is not under control. Let’s talk about ongoing mortgage fraud and robo-signing and the ongoing bailout/ taxpayer subsidy and people still losing their homes, and the poor still being the targets of illegal and predatory loans, and Too-Big-To-Fail getting worse, and the direct line between the bailout and the broken pension promises for civil servants and the overall price list for fraud that has been built.

Let’s talk about the people who created the underlying fraud still at work in places like Bank of America, and how few masterminds have gone to jail and how the SEC and the Obama administration has made that happen through inaction and passivity and how Congress is sitting on its hands because of the money coming in from lobbyists. Let’s talk about the increasing distance between the justice system for the poor and the justice system for the rich in this country.

Tell me what I missed.

The HFT noise is misplaced and a distraction from the ongoing real story.

Navigating sexism does not mean accepting sexism

Not enough time for a full post this morning, but I’d like people to read a New York Times article ironically entitled Moving Past Gender Barriers to Negotiate a Raise (hat tip Laura Strausfeld). It has amazing and awful tidbits like the following:

“It’s totally unfair because we don’t require the same thing of men. But if women want to be successful in this domain, they need to pay attention to this.”

If you read on you realize that what they mean by “pay attention to” is “roll over and conform to stereotypes”. Super gross, and fuck that.

I feel like this is a more subtle, New York Times version of Susan Patton’s terrible advice for young women in snaring husbands. What happened to the feminists?!!

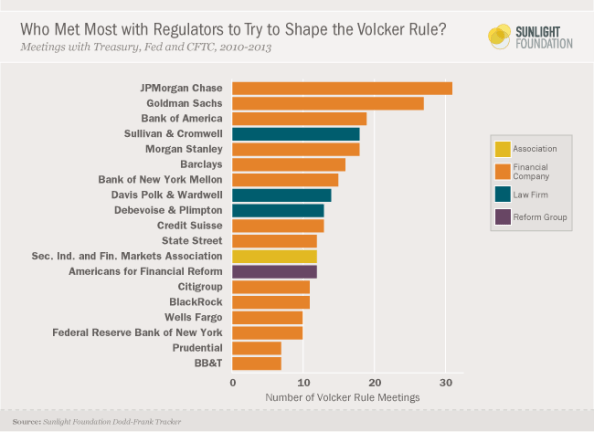

Lobbyists have another reason to dominate public commenting #OWS

Before I begin this morning’s rant, I need to mention that, as I’ve taken on a new job recently and I’m still trying to write a book, I’m expecting to not be able to blog as regularly as I have been. It pains me to say it but my posts will become more intermittent until this book is finished. I’ll miss you more than you’ll miss me!

On to today’s bullshit modeling idea, which was sent to me by both Linda Brown and Michael Crimmins. It’s a new model built in part by the former chief economist for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Andrei Kirilenko, who is now a finance professor at Sloan. In case you don’t know, the CFTC is the regulator in charge of futures and swaps.

I’ll excerpt this New York Times article which describes the model:

The algorithm, he says, uncovers key word clusters to measure “regulatory sentiment” as pro-regulation, anti-regulation or neutral, on a scale from -1 to +1, with zero being neutral.

If the number assigned to a final rule is different from the proposed one and closer to the number assigned to all the public comments, then it can be inferred that the agency has taken the public’s views into account, he says.

Some comments:

- I know really smart people that use similar sentiment algorithms on word clusters. I have no beef with the underlying NLP algorithm.

- What I do have a problem with is the apparent assumption that the “the number assigned to all the public comments” makes any sense, and in particular whether it takes into account “the public’s view”.

- It sounds like the algorithm dumps all the public comment letters into a pot and mixes it together to get an overall score. The problem with this is that the industry insiders and their lobbyists overwhelm public commenting systems.

- For example, go take a look at the list of public letters for the Volcker Rule. It’s not unlike this graphic on the meetings of the regulators on the Volcker Rule:

- Besides dominating the sheer number of letters, I’ll bet the length of each letter is also much longer on average for such parties with very fancy lawyers.

- Now think about how the NLP algorithm will deal with this in a big pot: it will be dominated by the language of the pro-industry insiders.

- Moreover, if such a model were to be directly used, say to check that public commenting letters were written in a given case, lobbyists would have even more reason to overwhelm public commenting systems.

The take-away is that this is an amazing example of a so-called objective mathematical model set up to legitimize the watering down of financial regulation by lobbyists.

Update: I’m willing to admit I might have spoken too soon. I look forward to reading the paper on this algorithm and taking a deeper look instead of relying on a newspaper.

Optimizing for Einstein and other homo-erotic theories

Jointly posted with Naked Capitalism.

At 41, I’m a grown woman. I’ve had enough weird and bad experiences as a woman in the mathematics part of “STEM,” inside and outside of academia, that my skin is relatively thick, a fact I’m proud of. Most of the time I let stuff roll off of me.

Even so, there are certain things that really get under my skin. Examples include terrible advice to young anxious women, and anything having to do with Princeton, New Jersey.

The recent appearance of the “Princeton Mom” Susan Patton (more about her below) has created a perfect storm inside me and I feel I have to comment, at the risk of giving her book more buzz. Note this post is not at all quantitative or even nerdy, except for some free market chit-chat which doesn’t really count. Instead it is much more straight-up ranting that I allow myself from time to time on mathbabe. If you want a more scientific and polite takedown, please see this Huffington Post article.

Princeton, New Jersey

There are two kinds of people in the world: people who hate Princeton, New Jersey, and people who are über successful white men (and sometimes Asian men). And I guess there’s a third kind, the people who have never visited Princeton.

I know that sounds histrionic, and I’ll make some caveats later on, but bear with me, it’s coming from personal experience.

I spent one horrific year (the academic year 1997-1998) as a visiting graduate student in the Princeton math department. Coming from the Harvard math department, I’d been socialized to think that spending all night in the library reading musty old French mathematical manuscripts was cool, and the very least one could do to impress one’s advisor.

In other words, I knew from male-dominated macho nerd culture. I girded myself for more of the same when I got to Princeton. But Princeton turned that up quite a few notches, and it wasn’t pretty. And it might have had something to do with being newly married, but that kind of makes my point stronger, not weaker, as you will see.

The first thing I noticed was that there were no other women in the math department. Well, that’s not quite true, since there were secretaries, and there was one female professor, who I never once spotted, and there was one other female graduate student, at least in theory, but it took me weeks and weeks to run into her.

But even so, I was kind used to that, being an experienced math nerd. I would normally just make do with hanging out with the social nerd boys. Unfortunately I couldn’t find any. It seemed like a department that either selected for anti-social people or efficiently turned them into anti-social people after they arrived.

As an illustration, let me tell you about the most social experience among graduate students I ever witnessed. It started out as a joyous scene: an enthusiastic young man bounded into the common room (which was almost always empty and didn’t really deserve the name “common room” at all) holding a book. He was showing off his newly bound thesis to an unusually large crowd of fellow graduate students – maybe 7 other men.

Instead of congratulating him, someone from the crowd grabbed the thesis and immediately and loudly proclaimed he’d found a typo. Everyone laughed. Long pause. The guy took his thesis and walked out of the room.

As you might imagine, I didn’t spend too much time in the math department. Instead, naïf that I was, I gave myself the task of finding friendly people I could truly connect with in the cultural wasteland that was Princeton Township.

The problem was, it felt like a village frozen in time. Of the perhaps 7 people I got to the point of trusting enough to share my desire for connection, no fewer than 3 of them suggested I join a church (that always made me wonder, what do Jewish people do in Princeton?), and the other 4 suggested I have a child in order to have company and something to do with myself. No shit. Human being as hobby.

I could go on – I could describe the pathetic attempt to attend a female graduate student mixer (“canceled for lack of attendants”) or the desperate time I sought counseling from the sole campus Mental Health Professional. Her exact words: “If it helps, I think I eventually see every female graduate student at Princeton.” Me: “Yes, it helps! I’m getting the FUCK out of here.” And I did.

I’ve been back once or twice, mostly to see the one person I became fond of in my year-long visit, and I am always amazed to see how little has changed. The last time I went, I attended a conference at the Institute for Advanced Study, and after lunch one afternoon I was in the cafeteria there, looking for coffee, when someone (a man! an oldish white man!) asked me to “find more plates, please” because there were no more clean ones. I looked down at my clothes: was I wearing a kitchen staff uniform like other people working the kitchen? Not at all, but I did suspiciously have my boobs with me. I must be kitchen staff.

Hey, I might be wrong

Other people have been to Princeton in the past 15 years, and some of them tell me it’s gotten somewhat better, and there are sightings of more than one woman at a time in the math department, and so on. I mean, the standards are super low, so “better” doesn’t necessarily mean much, but then again I don’t want to make it seem impossibly fixed. I’m glad the President of Princeton is was a woman.

On the other hand, another friend of mine had this to say about a very recent visit (less than 3 months ago):

I was a job candidate there. Put up at that Inn. Eating by myself, and there was a long table in the center of the room – all white men, many in bow ties, I swear. They were talking loudly about curriculum changes in the humanities over time, and what a shame it was that they couldn’t teach the classics anymore, laughing about having to teach world literature, etc. And everyone serving them was black. It was disgusting.

My theory of Princeton

I have a kind of fun theory of why Princeton is like this. The short version is that the culture has optimized to producing “geniuses,” which started with Einstein. In fact, Einstein’s success story also pinpoints the moment that time froze there. It was like the lesson learned for the town was that, if they could only keep the place exactly like it was the moment Einstein entered Princeton, then maybe it would be a breeding ground for many many more geniuses to make the town proud.

So that’s what’s happened: everything that is done there is done in the hope that more Einsteins will pop up among the population. Would-be geniuses are worshipped in weird ways, and anyone who is not themselves a genius candidate has to tailor themselves to those who are.

And since by definition geniuses are not women – and nor are minority men – we know what their roles turn out to be. Women, at least white women, are seen as useful in as much as they can have man-children who may grow up to be geniuses. Everyone else is even less crucial.

Do you think I’m being too harsh? Perhaps. To be honest, there is a space for white men to be tagged as successful without being full-blown geniuses, especially if they’re undergraduates. Namely, if they are potentially super rich, preferably by working in finance. In any case it’s all about the successful male narrative. There is no room for any other narrative.

Why am I talking shit about Princeton?

Here’s the thing. I have come to appreciate Princeton, in a wry way (“If you’re suicidal,” one character says, “and you don’t actually kill yourself, you become known as ‘wry.’ ”), and only as long as I’m not actually there. It is such a perfect example of old-fashioned, fucked up shit. You can’t make that stuff up.

But you can point to it and say, I will never live like that. It’s become a convenient counterfactual for me personally.

But not everyone has my perspective. My biggest fear nowadays about Princeton is that people are not sufficiently up front about how awful it is, and because of that people are sometimes tricked into visiting or even moving there.

It is this fear that I’m writing this essay, that I might be able to warn people away from that place, and possibly other places like it, although I don’t know of any. I’m a one-person anti-PR machine, but there’s only so much I can do.

Susan Patton to the rescue

It turns out my job is getting easier, thanks to Susan Patton, self-proclaimed “Princeton Mom”.

As if to amplify my complaints about Princeton, Patton has come out with yet more advice for girls who are aspiring to be Princeton wives. Her new advice to young women is to get fake boobs and whatever other plastic surgery deemed necessary in high school so you can attract a man in college.

Let’s back up for just a moment, though. Who is this woman?

You have heard of Susan Patton. She’s the confused bitch that wrote a now-famous letter to undergraduate women telling them to stop thinking about careers and start getting engaged whilst in college.

Oh, and she also suggested in a recent Valentine’s Day column (subtitle: “Young women in college need to smarten up and start husband-hunting.”) in the Wall Street Journal (where else!?) that, if you want men to marry you, you shouldn’t fuck them too soon, because, in her words, “men won’t buy the cow if the milk is free.”

Yes, she said that. I’ve got two responses to that tidbit. First, this:

mooooooo, motherfucker, moooooooooooo!!

Next, Aunt Pythia mentioned this but it bears repeating: Patton is objectifying women by calling them cows.

She’s doing the same when she tells young women to get boob jobs in high school. That’s in fact the name of her game. She is insisting that women abandon any hope of intellectual curiosity, goals or ambitions while they are still teenagers and start in on a desperate competition to be a Princeton wife.

Why is Patton so nuts?

By her own account, Susan Patton married the wrong guy – a non-Princeton guy – and later got divorced. She’s bitter about her lack of foresight. In some sense this is just a pathetic story about one sad person.

But in another way it’s not. I’ve been reading a super interesting book called Why Love Hurts: a Sociological Explanation that explains why Susan Patton has some things right. In fact she’s kind of brilliant, but for obviously weird reasons, and her plan to deal with the issues she rightly raises is completely fucked up.

Here’s what she’s understood: there has been a revolution in mating rituals and partnering, and it has become a competition, and it has become increasingly important to be sexually attractive to win this competition. And although it’s not the only competition young women are enduring in college, it’s the one she’s fixated on.

In fact to a large extent we’ve gone from a social contract partnering society to a kind of pseudo-free market partnering society. The results of that transition include various things like how men and women see themselves, and specifically how they (women, not men) blame themselves for failed relationships, and moreover how they are incentivized (or not) to get married, or have kids, or importantly, to keep their word.

One of the most interesting points, at least as it pertains to Susan Patton, is that whereas men used to need to get married and have children to assert their masculinity, this is no longer true.

Nowadays, according to this theory, men in question increasingly assert their masculinity to each other through the sexual attractiveness of their girlfriends, and they don’t care very much whether they get married and have kids, or at least they don’t feel any urgency (which gives rise to both “the noncommittal man” and “the woman who loves too much”).

So when Patton tells women to get boob jobs, she’s essentially telling them to improve their odds in that existing free market. It’s not about sexual gratification, or even “self confidence” for the women. It’s really a homo-erotic, all-male issue: be something that other men will be jealous of. And what is the measure of their jealousy? That other men are responding sexually to “my” woman. So this means men are focusing on signs of sexual responses in other men and deriving gratification from them.

Here’s what Patton has tragically wrong, though. Given that you’re willing to toss out your personal and intellectual growth for the sake of winning this competition, even given that, which is a sad way to approach life, it still doesn’t have a chance of working.

Because, once we’ve acknowledged and entered this free market for sexual and romantic partnership, it’s simply not going to work in this day and age to expect the men to want to get married when they’re 20 years old, and it’s also certainly not going to work to withhold sex from 20-year-old men and expect them to marry you. It’s just not where 20-year-old men are at in this system. In fact by doing those things a woman is signaling desperation, which – as is explained in this book – works against a given woman, not for them.

Patton and my theory

I’d like to square her advice with my optimized-for-geniuses theory of Princeton.

The main point of my theory is that it’s all about the men, and specifically, it’s all about the successful male narrative. Whereas before it was enough for women to subjugate their personality, personal ambitions, and long-term goals for the purpose of potential geniuses and/or rich finance guys, Patton is now calling for women to also mutilate their bodies for the cause.

As a signaling device, it indicates real hunger for the role. As some guy said:

Fake boobs say, ‘I objectify myself, therefore I have no problem with you doing the same.’

But as I mentioned above, it is a failed signaling device. It’s an indication that the cultural worship of men has gone too far in Princeton, New Jersey. I’m hopeful that the smell of desperation will be so obvious that people will have to take a closer look and scrutinize the culture.