Archive

Happy Birthday, Occupy Wall Street! #OWS

Hey, what are you doing for the 2nd anniversary of the occupation of Zuccotti Park?

I know what I’m doing, namely going down to the park and handing out hundreds of copies of my occupy group’s new book – now on scribd!!. Here’s a ridiculous gif of the pile of books that came from the printer yesterday with my kindergartner posing by it (you might need to click on it to see the animation!!):

I’m also planning a small speech at 10:15am, which I’m still writing. I’ll post it here later. here it is:

Thank you for coming

Thank you for occupying

I am here today to announce a birth

The birth of a book

It’s called “Occupy Finance”

We wrote it

we are Alternative BankingWho are we?

We are a working group of Occupy

we first met almost two years ago

we have been meeting ever since

we meet every Sunday afternoon

at Columbia University

our meetings are totally open

we want you to comeWe discuss the financial system

we discuss financial regulation

we discuss how lobbyists destroy regulation

we discuss how Obama destroys regulation

we discuss what we can do to help

how we can make our opinions known

how we can make the system work for us

the 99%Last year we had a project

The 52 Shades of Greed

we came here to Zuccotti Park

we gave out hundreds of packs of cards

they explained the financial system

they called out the criminals

they called out the toxic ideas

and the toxic instruments

and the toxic institutions

that started this messThis year we’ve come back

with another present to share

it’s a book we wrote

it’s a book for all of us

it explains how the financial system works

and how it doesn’t work

it explains how the system uses us

how the bankers scam us all

how the regulators fail to do their job

how the politicians have been boughtWhy did we write this book?

we wrote it for you

and we wrote it for us

we wrote it for anyone

who wants to know

how to argue against

the side of greed

the side of corruption

the side of entitlementlet me tell you something

some people call us radicals

but listen up

when the top 1%

capture 95% of the income gains

since the so-called end

of the recession,

when more than half the country thinks

that we didn’t do enough

to put bankers in jail,

when the median household income

has gone down 7.3% since 2007,

when the actual employment rate

is 5% below 2007,

when the jobs that do exist are crappy

when we get paid with prepaid debit cards

that nickel and dime us all

then what we demand is not radical

it is only a system that works

we are asking for a just system

we are asking for a fair system

we are asking for an end to too-big-to-fail

we demand banks take less risk

with our money

and we are asking lawmakers

to stop banks

once and for all

from scamming people because they are poorPlease join us

we want you to come

you don’t need to be an expert

we started out as strangers

who wanted to know how things work

we have become friends

we have become allies

we have made something

out of our curiousity

and out of our hard work

and we are here today

to share that with you

and to ask you to join us

please join us

happy birthday to us!

Thank you!!

Happy Larry Summers isn’t the Fed Chair Day! #OWS

So yesterday there I was with my Occupy group, we’d just gone over our plans for the second anniversary of Occupy Wall Street this coming Tuesday. We talked over releasing our book and the press conference in Zuccotti Park at 10:15am. We talked over the group’s web presence and how we had to improve it a bit before then, what flyers to hand out with the book, and how to get everyone copies of the book before then. In other words, logistics.

Then we turned to the content of the meeting, namely working on our op-ed focused on Larry Summers and why he shouldn’t be named the Fed Chair.

We’d brainstormed about it last week, and I put together a crappy first draft, and then another in our group had blown away my milquetoast logical argument with a couple of paragraphs of pure Occupy outrage. We were thinking about how to combine them, and we were also trying to decide whether to come up with a list of better candidates or just say “anyone would be better than Larry Summers.”

All of a sudden, someone in our group, who had been browsing the web in search for better candidates, suddenly interjects that “Larry Summers has withdrawn from consideration for the Fed job!”

That’s some good fucking karma.

And yes, it’s a pretty awesome moment when exactly what you’re working towards comes true like that, even if it’s only one thing on a very long list.

Here’s the next thing on the list: Too Big To Fail needs to end, people. Someone named Scott Cahoon sent me a video regarding that very topic last night which advertises his book called “Too Big Has Failed,” available on Amazon.

p.s. also, it’s been 5 years since the crisis, and not enough has changed.

Occupy Finance the book, coming out next Tuesday (#OWS)

Holy shit I’m just about bursting with pride to announce that my Occupy group’s book, Occupy Finance, is coming out Tuesday and is at the printer right now.

This is thanks in large part to all of you awesome people who sent contributions for the printing. You guys totally rock.

Our plan is to meet in Zuccotti Park Tuesday morning, September 17th, which is the 2nd anniversary of the occupation, give a wee press conference at 10am or so, and then hand out hundreds of copies of the book to whomever shows up.

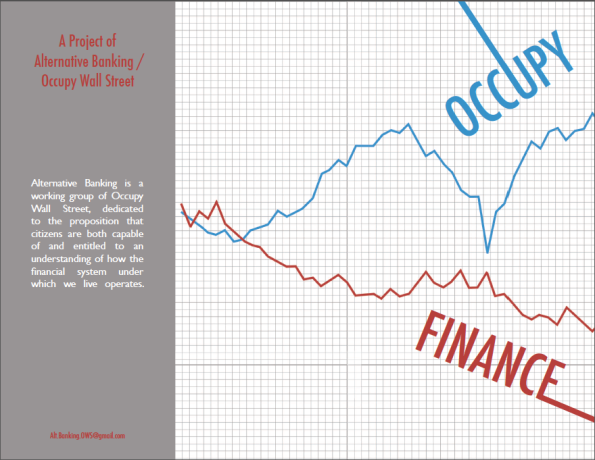

Here’s the wrap-around cover to give you just a taste:

See you guys on Tuesday! The event is also on Facebook.

HSBC protest tomorrow at noon with Alternative Banking (#OWS)

I’m helping organize a protest against HSBC with my Alternative Banking group. We’re going to be joined by Everett Stern, an HSBC whistleblower. You can learn more about that guy by reading Matt Taibbi’s Rolling Stones article on him.

Here’s the press release, I hope I see you there!

Occupy Finance, the book: announcement and fundraising (#OWS)

Members of the Alt Banking Occupy group have been hard at work recently writing a book which we call Occupy Finance. Our blog for the book is here. It’s a work in progress but we’re planning to give away 1,000 copies of the book on September 17th, the 2nd anniversary of the Occupation of Zuccotti Park.

We’re modeling it after another book which was put out last year by Strike Debt called the Debt Resistor’s Operations Manual, which I blogged about here when it came out.

Crappy Kickstarter

I want to tell you more about our book, which we’re writing by committee, but I did want to mention that in order to get the first 1,000 copies printed by September 17th, we’ll need altogether $2,500, and so far we’ve collected $2,150 from the various contributors, editors, and their friends. So we need to collect $350 at this point. If we get more then we’ll print more.

If you’d like to help us towards the last $350, we’d appreciate it – and I’ll even send you a copy of the book afterwards. But please don’t send anything you don’t want to give away, I can’t promise you some kind of formal proof of your contribution for tax purposes. This is Occupy after all, we suck at money. Consider this a crappy version of Kickstarter.

Anyway if you want to help out, send me a personal email to arrange it: cathy.oneil at gmail. I’ll basically just tell you to send me a personal check, since I’m the one fronting the money.

Audience and Mission

The mission of the book, like the mission of the Alt Banking group, is to explain the financial system and its dysfunction in plain English and to offer suggestions for how to think about it and what we can do to improve it.

The audience for this book is the 99% who are Occupy-friendly or at least Occupy-inquisitive. Specifically, we want people who know there’s something wrong, but don’t have the background to articulate what it is, to have a reference to help them define their issues. We want to give them ammunition at the water cooler.

What’s in the book?

After a stirring introduction, the book is divided into three basic parts: The Real Life Impact of Financialization, How We Got Here, and Things to do. I’ve got links below.

Keep in mind things are still in flux and will be changed, sometimes radically, before the final printing. In particular we’re actually using DropBox for most of our edits so the links below aren’t final versions (but will be eventually). Even so, the content below will give you a good idea of what we have in mind, and if you have comments or suggestions, please do tell us, thanks!

Our table of contents is as follows, and the available chapters have associated links:

Introduction: Fighting Our Way Out of the Financial Maze

The Real Life Impact of Financialization

- Heads They Win, Tails We Lose: Real Life Impact of Financialization on the 99%

- The bailout: it didn’t work, it’s still going on, and it’s making things worse

How We Got Here

- What Banks Do

- Impact of Deregulation

- The top ten financial outrages

- The muni bond industry and the 99%

Things to Do

Update: I’ve got $225 $301 pledged so far! You people rock!!

If we bailed out the banks, why not Detroit? (#OWS)

I wrote a post yesterday to discuss the fact that, as we’ve seen in Detroit and as we’ll soon see across the country, the math isn’t working out on pensions. One of my commenters responded, saying I was falling for a “very right wing attack on defined benefit pensions.”

I think it’s a mistake to think like that. If people on the left refuse to discuss reality, then who owns reality? And moreover, who will act and towards what end?

Here’s what I anticipate: just as “bankruptcy” in the realm of airlines has come to mean “a short period wherein we toss our promises to retired workers and then come back to life as a company”, I’m afraid that Detroit may signal the emergence of a new legal device for cities to do the same thing, especially the tossing out of promises to retired workers part. A kind of coordinated bankruptcy if you will.

It comes down to the following questions. For whom do laws work? Who can trust that, when they enter a legal obligation, it will be honored?

From Trayvon Martin to the people who have been illegally foreclosed on, we’ve seen the answer to that.

And then we might ask, for whom are laws written or exceptions made? And the answer to that might well be for banks, in times of crisis of their own doing, and so they can get their bonuses.

I’m not a huge fan of the original bailouts, because it ignored the social and legal contracts in the opposite way, that failures should fail and people who are criminals should go to jail. It didn’t seem fair then, and it still doesn’t now, as JP Morgan posts record $6.4 billion profits in the same quarter that it’s trying to settle a $500 million market manipulation charge.

It’s all very well to rest our arguments on the sanctity of the contract, but if you look around the edges you’ll see whose contracts get ripped up because of fraudulent accounting, and whose bonuses get bigger.

And it brings up the following question: if we bailed out the banks, why not the people of Detroit?

Payroll cards: “It costs too much to get my money” (#OWS)

If this article from yesterday’s New York Times doesn’t make you want to join Occupy, then nothing will.

It’s about how, if you work at a truly crappy job like Walmart or McDonalds, they’ll pay you with a pre-paid card that charges you for absolutely everything, including checking your balance or taking your money, and will even charge you for not using the card. Because we aren’t nickeling and diming these people enough.

The companies doing this stuff say they’re “making things convenient for the workers,” but of course they’re really paying off the employers, sometimes explicitly:

In the case of the New York City Housing Authority, it stands to receive a dollar for every employee it signs up to Citibank’s payroll cards, according to a contract reviewed by The New York Times.

Thanks for the convenience, payroll card banks!

One thing that makes me extra crazy about this article is how McDonalds uses its franchise system to keep its hands clean:

For Natalie Gunshannon, 27, another McDonald’s worker, the owners of the franchise that she worked for in Dallas, Pa., she says, refused to deposit her pay directly into her checking account at a local credit union, which lets its customers use its A.T.M.’s free. Instead, Ms. Gunshannon said, she was forced to use a payroll card issued by JPMorgan Chase. She has since quit her job at the drive-through window and is suing the franchise owners.

“I know I deserve to get fairly paid for my work,” she said.

The franchise owners, Albert and Carol Mueller, said in a statement that they comply with all employment, pay and work laws, and try to provide a positive experience for employees. McDonald’s itself, noting that it is not named in the suit, says it lets franchisees determine employment and pay policies.

I actually heard about this newish scheme against the poor when I attended the CFPB Town Hall more than a year ago and wrote about it here. Actually that’s where I heard people complain about Walmart doing this but also court-appointed child support as well.

Just to be clear, these fees are illegal in the context of credit cards, but financial regulation has not touched payroll cards yet. Yet another way that the poor are financialized, which is to say they’re physically and psychologically separated from their money. Get on this, CFPB!

Update: an excellent article about this issue was written by Sarah Jaffe a couple of weeks ago (hat tip Suresh Naidu). It ends with an awesome quote by Stephen Lerner: “No scam is too small or too big for the wizards of finance.”

Crash the pick-up party with me?

I’m not sure my friend Jason Windawi will appreciate the credit, but he pointed me to this Meetup yesterday called “MEN THAT DATE HOT WOMEN”, which I have conveniently screen-shotted for y’all:

I’m not sure where to start with deconstructing this pick-up-artist wannabe clan, but let’s just START WITH THE ALL CAPS. Who does that? Update: turns out THE NAVY DOES THAT.

I’m thinking of crashing this Meetup with a posse of sufficiently ridiculous and hilarious friends.

First the good news: I can easily imagine what kind of person I’d love to attract for this action (namely, anyone who thinks this is ludicrous, in a fun way, and wants to join me) but, and here’s the other good news, I’m having trouble figuring out the perfect thing to do once we get there. Let’s think.

First thought: line dance with boas, singing “I will survive.” Maybe not that exactly, but something to intentionally and directly contrast the oppressively normative nature of a bunch of straight guys looking for “hot” women using a formulaic approach involving magic tricks. Bonus points, obviously, for ill-fitting cocktail dresses that emphasize jiggling flesh.

In other words, let’s take a page out of this book, one of my all-time favorite Occupy actions:

Other ideas welcome!

Who speaks Hebrew?

I got covered in an Israeli newspaper talking about Occupy.

Here’s the article. If you can read Hebrew, please tell me how it reads.

Update: here’s a pdf version of it.

Left Forum panels next weekend: #OWS Alt Banking meeting and a debate with Doug Henwood

Next weekend at Pace University in New York City I’ll be taking part in two panels at the Left Forum, a yearly conference of progressives that everybody who’s anybody seems to know about, although this will be my first year there. For example Noam Chomsky is coming this year.

First, from noon til 1:40 on Saturday June 8th, I’ll be debating how to shrink the financial sector with Doug Henwood, author of Wall Street: how it works and for whom. The panel will be moderated by my buddy Suresh Naidu, an occupier profiled in the Huffington Post. The announcement for this panel is here and includes room information.

Second, from 3:40 til 5:20, also on Saturday June 8th, I’ll be facilitating a meeting of the Alternative Banking group of OWS, which will be loads of fun. The idea is to explain to the panel audience how we roll in Alt Banking, to have a discussion about breaking up the banks, and to get the audience to participate as well. We expect them to enjoy getting on stack. The announcement for this panel is here, please come!

Registration for the Left Forum is still open and is affordable. Go here to register, and see you next weekend!

SEC Roundtable on credit rating agency models today

I’ve discussed the broken business model that is the credit rating agency system in this country on a few occasions. It directly contributed to the opacity and fraud in the MBS market and to the ensuing financial crisis, for example. And in this post and then this one, I suggest that someone should start an open source version of credit rating agencies. Here’s my explanation:

The system of credit ratings undermines the trust of even the most fervently pro-business entrepreneur out there. The models are knowingly games by both sides, and it’s clearly both corrupt and important. It’s also a bipartisan issue: Republicans and Democrats alike should want transparency when it comes to modeling downgrades- at the very least so they can argue against the results in a factual way. There’s no reason I can see why there shouldn’t be broad support for a rule to force the ratings agencies to make their models publicly available. In other words, this isn’t a political game that would score points for one side or the other.

Well, it wasn’t long before Marc Joffe, who had started an open source credit rating agency, contacted me and came to my Occupy group to explain his plan, which I blogged about here. That was almost a year ago.

Today the SEC is going to have something they’re calling a Credit Ratings Roundtable. This is in response to an amendment that Senator Al Franken put on Dodd-Frank which requires the SEC to examine the credit rating industry. From their webpage description of the event:

The roundtable will consist of three panels:

- The first panel will discuss the potential creation of a credit rating assignment system for asset-backed securities.

- The second panel will discuss the effectiveness of the SEC’s current system to encourage unsolicited ratings of asset-backed securities.

- The third panel will discuss other alternatives to the current issuer-pay business model in which the issuer selects and pays the firm it wants to provide credit ratings for its securities.

Marc is going to be one of something like 9 people in the third panel. He wrote this op-ed piece about his goal for the panel, a key excerpt being the following:

Section 939A of the Dodd-Frank Act requires regulatory agencies to replace references to NRSRO ratings in their regulations with alternative standards of credit-worthiness. I suggest that the output of a certified, open source credit model be included in regulations as a standard of credit-worthiness.

Just to be clear: the current problem is that not only is there wide-spread gaming, but there’s also a near monopoly by the “big three” credit rating agencies, and for whatever reason that monopoly status has been incredibly well protected by the SEC. They don’t grant “NRSRO” status to credit rating agencies unless the given agency can produce something like 10 letters from clients who will vouch for them providing credit ratings for at least 3 years. You can see why this is a hard business to break into.

The Roundtable was covered yesterday in the Wall Street Journal as well: Ratings Firms Steer Clear of an Overhaul – an unfortunate title if you are trying to be optimistic about the event today. From the WSJ article:

Mr. Franken’s amendment requires the SEC to create a board that would assign a rating firm to evaluate structured-finance deals or come up with another option to eliminate conflicts.

While lawsuits filed against S&P in February by the U.S. government and more than a dozen states refocused unflattering attention on the bond-rating industry, efforts to upend its reliance on issuers have languished, partly because of a lack of consensus on what to do.

I’m just kind of amazed that, given how dirty and obviously broken this industry is, we can’t do better than this. SEC, please start doing your job. How could allowing an open-source credit rating agency hurt our country? How could it make things worse?

When is shaming appropriate?

As a fat person, I’ve dealt with a lot of public shaming in my life. I’ve gotten so used to it, I’m more an observer than a victim most of the time. That’s kind of cool because it allows me to think about it abstractly.

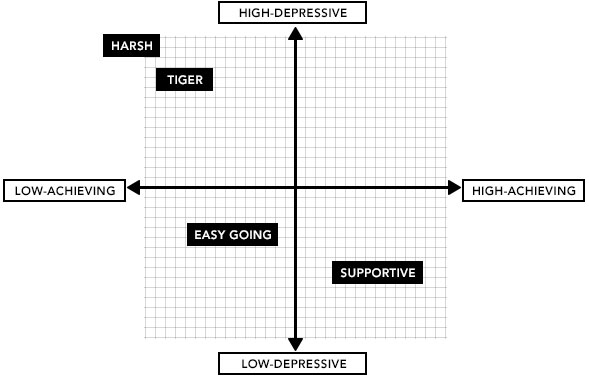

I’ve come up with three dimensions for thinking about this issue.

- When is shame useful?

- When is it appropriate?

- When does it help solve a problem?

Note it can be useful even if it doesn’t help solve a problem – one of the characteristics of shame is that the person doing the shaming has broken off all sense of responsibility for whatever the issue is, and sometimes that’s really the only goal. If the shaming campaign is effective, the shamed person or group is exhibited as solely responsible, and the shamer does not display any empathy. It hasn’t solved a problem but at least it’s clear who’s holding the bag.

The lack of empathy which characterizes shaming behavior makes it very easy to spot. And extremely nasty.

Let’s look at some examples of shaming through this lens:

Useful but not appropriate, doesn’t solve a problem

Example 1) it’s both fat kids and their parents who are to blame for childhood obesity:

Example 2) It’s poor mothers that are to blame for poverty:

These campaigns are not going to solve any problems, but they do seem politically useful – a way of doubling down on the people suffering from problems in our society. Not only will they suffer from them, but they will also be blamed for them.

Inappropriate, not useful, possibly solving a short-term discipline problem

Let’s go back to parenting, which everyone seems to love talking about, if I can go by the number of comments on my recent post in defense of neglectful parenting.

One of my later commenters, Deane, posted this article from Slate about how the Tiger Mom approach to shaming kids into perfection produces depressed, fucked-up kids:

Hey parents: shaming your kids might solve your short-term problem of having independent-minded kids, but it doesn’t lead to long-term confidence and fulfillment.

Appropriate, useful, solves a problem

Here’s when shaming is possibly appropriate and useful and solves a problem: when there have been crimes committed that affect other people needlessly or carelessly, and where we don’t want to let it happen again.

For example, the owner of the Bangladeshi factory which collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people got arrested and publicly shamed. This is appropriate, since he knowingly put people at risk in a shoddy building and added three extra floors to improve his profits.

Note shaming that guy isn’t going to bring back those dead people, but it might prevent other people from doing what he did. In that sense it solves the problem of seemingly nonexistent safety codes in Bangladesh, and to some extent the question of how much we Americans care about cheap clothes versus conditions in factories which make our clothes. Not completely, of course. Update: Major Retailers Join Plan for Greater Safety in Bangladesh

Another example of appropriate shame would be some of the villains of the financial crisis. We in Alt Banking did our best in this regard when we made the 52 Shades of Greed card deck. Here’s Robert Rubin:

Conclusion

I’m no expert on this stuff, but I do have a way of looking at it.

One thing about shame is that the people who actually deserve shame are not particularly susceptible to feeling it (I saw that first hand when I saw Ina Drew in person last month, which I wrote about here). Some people are shameless.

That means that shame, whatever its purpose, is not really about making an individual change their behavior. Shame is really more about setting the rules of society straight: notifying people in general about what’s acceptable and what’s not.

From my perspective, we’ve shown ourselves much more willing to shame poor people, fat people, and our own children than to shame the actual villains who walk among us who deserve such treatment.

Shame on us.

Why we should break up the megabanks (#OWS)

Today is May Day, and my Occupy group and I are planning to join in the actions all over the city this afternoon. At 2:00 I’m going to be at Cooper Square, where Free University is holding a bunch of teach-ins, and I’m giving one entitled “Why we should break up the megabanks.” I wanted to get my notes for the talk down in writing beforehand here.

The basic reasons to break up the megabanks are these:

- They hold too much power.

- They cost too much.

- They get away with too much.

- They make things worse.

Each requires explanation.

Megabanks hold too much power

When Paulson went to Congress to argue for the bailout in 2008, he told them that the consequences of not acting would be a total collapse of the financial system and the economy. He scared Congress and the American people to such an extent that the banks managed to receive $700 billion with no strings attached. Even though half of that enormous pile of money was supposed to go to help homeowners threatened with foreclosures, almost none of it did, because the banks found other things to do with it.

The power of megabanks doesn’t only exert itself through the threat of annihilation, though. It also flows through lobbyists who water down Dodd-Frank (or really any policy that banks don’t like) and through “the revolving door,” the men and women who work for Treasury, the White House, and regulators about half the time and sit in positions of power in the megabanks the other half of their time, gaining influence and money and retiring super rich.

It is unreasonable to expect to compete with this kind of insularity and influence of the megabanks.

They cost too much

The bailout didn’t work and it’s still going on. And we certainly didn’t “make money” on it, compared to what the government could have expected if we had invested differently.

But honestly it’s too narrow to think about money alone, because what we really need to consider is risk. And there we’ve lost a lot: when we bailed them out, we took on the risk of the megabanks, and we have simply done nothing to return it. Ultimately the only way to get rid of that costly risk is to break them up once and for all to a size that they can reasonably and obviously be expected to fail.

Make no mistake about it: risk is valuable. It may not be quantifiable at a moment of time, but over time it becomes quite valuable and quantifiable indeed, in various ways.

One way is to think about borrowing costs and long-term default probabilities, and there the estimates have varied but we’ve seen numbers such as $83 billion per year modeled. Few people dispute that it’s the right order of magnitude.

They get away with too much

There doesn’t seem to be a limit to what the megabanks can get away with, which we’ve seen with HSBC’s money laundering from terrorists and drug cartels, we’ve seen with Jamie Dimon and Ina Drew lying to Congress about fucking with their risk models, we’ve seen with countless fraudulent and racist practices with mortgages and foreclosures and foreclosure reviews, not to mention setting up customers to fail in deals made to go bad, screwing municipalities and people with outrageous fees, shaving money off of retirement savings, and manipulating any and all markets and rates that they can to increase their bonuses.

The idea of a financial sector is to grease the wheels of commerce, to create a machine that allows the economy to work. But in our case we have a machine that’s taken over the economy instead.

They make things worse

Ultimately the best reason to break them up right now, the sooner the better, is that the incentives are bad and getting worse. Now that they live in a officially protected zone, there is even less reason for them then there used to be to rein in risky practices. There is less reason for them to worry about punishments, since the SEC’s habit of letting people off without jailtime, meaningful penalties, or even admitting wrongdoing has codified the lack of repercussions for bad behavior.

If we use recent history as a guide, the best job in finance you can have right now is inside a big bank, protected from the law, rather than working at a hedge fund where you can be nabbed for insider trading and publicly displayed as an example of the SEC’s new “toughness.”

What we need to worry about now is how bad the next crash is going to be. Let’s break up the megabanks now to mitigate that coming disaster.

Alternative Banking news (#OWS): Left Forum, Citigroup coverage, Occupy Finance

The Alternative Banking group of OWS is still meeting every Sunday at Columbia from 3-5pm to discuss financial reform. We also often have pre-meeting talks open to the public. The normal meeting is open to the public as well, but it can get pretty wonky. This week’s pre-meeting talk is an update on Greece.

Please join us! Details are here, on our blog. You can also sign up for the normal meeting and pre-meeting through Meetup here.

Left Forum

We just found out our proposal for a panel at the Left Forum got accepted (here we are on their website). In case you don’t know much about the Left Forum, it’s a conference taking place on June 7-9th at Pace University in New York, which brings together a huge number of lefties and progressives and activists together to talk about their work. It used to be called the Socialist Scholars Conference. Noam Chomsky and Cornel West are scheduled to be there this year.

Our plan for the panel is to have a “regular meeting” at the conference. So anyone in our group can come (I think they have to register first), which means anyone at all, since our group is open to the public. Our probably topic will be “Breaking up the megabanks” or something along those lines.

I’ll update when we find out when we’re scheduled to go on. Here’s a full list of approved panel topics.

Citigroup coverage

While I was away in D.C. attending a congressional hearing on big data (blog post on that will come soon!) my Alt Banking peeps staged a protest outside the Citigroup annual shareholder meeting in New York. Here’s some coverage:

- Financial Times

- Dealbreaker: Spandex-clad roller-girl

- Dealbreaker: Spandex-Clad Roller Girl Was Not Only Prepared To Put Citi Execs Over Her Knee But Read Them Their Rights

- La Jornada

- Marni’s recent essay in the Huffington Post

Here’s a picture of the whole group:

And here’s a picture of Marni, who was a huge hit:

Occupy Finance

Final thing: we’re writing a book in Alt Banking, called Occupy Finance, and modeled after the Debt Resistor’s Operation Manual, which we adore. Please volunteer to be a writer or an editor if you have time!

Note: you don’t need to be a specialist in finance to be an editor, that’s the point. We’re writing it for the interested public. Email me if you want to be part of it – my email is on the “About” page.

10 reasons to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting tomorrow (#OWS)

The Alternative Banking group of #OWS is showing up bright and early tomorrow morning to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting. Details are: we meet outside the Hilton Hotel, Sixth Avenue between 53rd and 54th Streets, tomorrow, April 24th, from 8-10 am. We’ve already made some signs (see below).

Here are ten reasons for you to join us.

1) The Glass-Steagall Act, which had protected the banking system since 1933, was repealed in order to allow Citibank and Traveler’s Insurance to merge.

In fact they merged before the act was even revoked, giving us a great way to date the moment when politicians started taking orders from bankers – at the time, President Bill Clinton publicly declared that “the Glass–Steagall law is no longer appropriate.”

2) The crimes Citi has committed have not been met with reasonable punishments.

From this Bloomberg article:

In its complaint against Citigroup, the SEC said the bank misled investors in a $1 billion fund that included assets the bank had projected would lose money. At the same time it was selling the fund to investors, Citigroup took a short position in many of the underlying assets, according to the agency.

The SEC only attempted to fine Citi $285 million, even though Citi’s customers lost on the order of $600 million from their fraud. Moreover, they were not required to admit wrongdoing. Judge Rakoff refused to sign off on the deal and it’s still pending. Citi is one of those banks that is simply too big to jail.

3) We’d like our pen back, Mr. Weill. Going back to repealing Glass-Steagall. Let’s take an excerpt from this article:

…at the signing ceremony of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley, aka the Glass Steagall repeal act, Clinton presented Weill with one of the pens he used to “fine-tune” Glass-Steagall out of existence, proclaiming, “Today what we are doing is modernizing the financial services industry, tearing down those antiquated laws and granting banks significant new authority.”

Weill has since decided that repealing Glass-Steagall was a mistake.

4) Do you remember the Plutonomy Memos? I wrote about them here. Here’s a tasty excerpt which helps us remember when the class war was started and by whom:

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization… Since we think the plutonomy is here, is going to get stronger… It is a good time to switch out of stocks that sell to the masses and back to the plutonomy basket.

5) Robert Rubin – enough said. To say just a wee bit more, let’s look at the Bloomberg Businessweek article, “Rethinking Robert Rubin”:

Rubinomics—his signature economic philosophy, in which the government balances the budget with a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, driving borrowing rates down—was the blueprint for an economy that scraped the sky. When it collapsed, due in part to bank-friendly policies that Rubin advocated, he made more than $100 million while others lost everything.

That $100 million was made at Citigroup, which was later bailed out because of bets Rubin helped them make. He has thus far shown no remorse.

6) The Revolving Door problems Citigroup has. Bill Moyers has a great article on the outrageous revolving door going straight from banks to the Treasury and the White House. What with Rubin and Lew, Citigroup seems pretty much a close second behind Goldman Sachs for this sport.

7) The bailout. Citigroup took $100 billion from the Fed at the height of the bailout in January 2009.

8) The bailout was actually for Citigroup. If you’ve read Sheila Bair’s book Bull by the Horns, you’ll see the bailout from her inside perspective. And it was this: that Citigroup was really the bank that needed it worst. That in fact, the whole bailout was a cover for funneling money to Citi.

9) The ongoing Fed dole. The bailout is still going on – and Citigroup is currently benefitting from the easy money that the Fed is offering, not to mention the $83 billion taxpayer subsidy. WTF?!

10) Lobbying for yet more favors. Citi spent $62 million from 2001 to 2010 on lobbying in Washington. What’s their return on that investment, do you think?

Join us tomorrow morning! Details here.

Tax haven in comedy: the Caymans (#OWS)

This is a guest post by Justin Wedes. A graduate of the University of Michigan with degrees in Physics and Linguistics with High Honors, Justin has taught formerly truant and low-income youth in subjects ranging from science to media literacy and social justice activism. A founding member of the New York City General Assembly (NYCGA), the group that brought you Occupy Wall Street, Justin continues his education activism with the Grassroots Education Movement, Class Size Matters, and now serves as the Co-Principal of the Paul Robeson Freedom School.

Yesterday was tax day, when millions of Americans fulfilled that annual patriotic ritual that funds roads, schools, libraries, hospitals, and all those pesky social services that regular people rely upon each day to make our country liveable.

Millions of Americans, yes, but not ALL Americans.

Some choose to help fund roads, schools, libraries, hospitals in other places instead. Like the Cayman Islands.

Don’t get me wrong – I love Caymanians. Beautifully hospitable people they are, and they enjoy arguably the most progressive taxes in the world: zero income tax and only the rich pay when they come to work – read “cook the books” – on their island for a few days a year. School is free, health care guaranteed to all who work. It’s a beautiful place to live, wholly subsidized by the 99% in developed countries like yours and mine.

When they stash their money abroad and don’t pay taxes while doing business on our land, using our workforce and electrical grids and roads and getting our tax incentives to (not) create jobs, WE pay.

We small businesses.

We students.

We nurses.

We taxpayers.

I went down to the Caymans myself to figure out just how easy it is to open an offshore tax haven and start helping Caymanians – and myself – rather than Americans.

Here’s what happened:

Elizabeth Fischer talks about climate modeling at Occupy today

I’m really excited to be going to the pre-meeting talk of my Occupy group today. We’re having a talk by Elizabeth Fischer, who is a post-doc at NASA GISS, a laboratory focused largely on climate change up here in the Columbia neighborhood.

She is coming to talk with us about her work investigating the long-term behavior of ice sheets in a changing climate. Before joining GISS, Dr. Fischer was a quant on Wall Street, working on statistical arbitrage, trade execution, simulation/modeling platforms, signal development, and options trading. I met her when we were both students at math camp in 1988, but we reconnected this past summer at the reunion.

The actual title of her talk is “The History of CO2: Past, Present and Future” and it’s open to the public, so please come if you can (it’s at 2:00 pm in room 409 here but more details are here).

After Elizabeth, we’ll be having our usual Occupy meeting. Topics this week include our plans for a Citigroup and HSBC picket later this month, our panel submissions to the Left Forum in June, our plans for May Day, and continued work on writing a book modeled after the Debt Resistor’s Operations Manual.

Housekeeping – RSS feed for mathbabe broken, possibly fixed

I’ve been trying to address the problem people have been having with their RSS feed for mathbabe. Thanks to my nerd-girl friend Jennifer Rubinovitz, I’ve changed some settings in my WordPress settings and now I can view all of my posts when I open up RSSOwl. But in order for your reader to get caught up I have a feeling you’ll need to somehow refresh it or maybe get rid of mathbabe and then re-subscribe. I’ll update as I learn more (please tell me what’s working for you!).

Guest Post SuperReview Part III of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I and a little Part II: Where We Are Now

Whattup.

Moving on from Lewis’ cute Bloomberg column reprint, we come to the next essay in the series:

The Widening Gyre: Inequality, Polarization, and the Crisis by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells

Indefatigable pair Paul Krugman and Robin Wells (KW hereafter) contribute one of the several original essays in the book, but the content ought to be familiar if you read the New York Times, know something about economics or practice finance. Paul Krugman is prolific, and it isn’t hard to be prolific when you have to rewrite essentially the same column every week; question, are there other columnists who have been so consistently right yet have failed to propose anything that the polity would adopt? Political failure notwithstanding, Krugman leaves gems in every paragraph for the reader new to all this. The title “The Widening Gyre” comes from an apocalyptic William Yeats Butler poem. In this case, Krugman and Wells tackle the problem of why the government responded so poorly to the crisis. In their words:

By 2007, America was about as unequal as it had been on the eve of the Great Depression – and sure enough, just after hitting this milestone, we lunged into the worst slump since the Depression. This probably wasn’t a coincidence, although economists are still working on trying to understand the linkages between inequality and vulnerability to economic crisis.

Here, however, we want to focus on a different question: why has the response to crisis been so inadequate? Before financial crisis struck, we think it’s fair to say that most economists imagined that even if such a crisis were to happen, there would be a quick and effective policy response [editor’s note: see Kautsky et al 2016 for a partial explanation]. In 2003 Robert Lucas, the Nobel laureate and then president of the American Economic Association, urged the profession to turn its attention away from recessions to issues of longer-term growth. Why? Because he declared, the “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Famous last words from Professor Lucas. Nevertheless, the curious failure to apply what was once the conventional wisdom on a useful scale intrigues me for two reasons. First, most political scientists suggest that democracy, versus authoritarian system X, leads to better outcomes for two reasons.

1. Distributional – you get a nicer distribution of wealth (possibly more productivity for complicated macro reasons); economics suggests that since people are mostly envious and poor people have rapidly increasing utility in wealth, democracy’s tendency to share the wealth better maximizes some stupid social welfare criterion (typically, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency).

2. Information – democracy is a better information aggregation system than dictatorship and an expanded polity makes better decisions beyond allocation of produced resources. The polity must be capable of learning and intelligent OR vote randomly if uninformed for this to work. While this is the original rigorous justification for democracy (first formalized in the 1800s by French rationalists), almost no one who studies these issues today believes one-person one-vote democracy better aggregates information than all other systems at a national level. “Well Leon,” some knave comments, “we don’t live in a democracy, we live in a Republic with a president…so shouldn’t a small group of representatives better be able to make social-welfare maximizing decisions?” Short answer: strong no, and US Constitutionalism has some particularly nasty features when it comes to political decision-making.

Second, KW suggest that the presence of extreme wealth inequalities act like a democracy disabling virus at the national level. According to KW extreme wealth inequalities perpetuate themselves in a way that undermines both “nice” features of a democracy when it comes to making regulatory and budget decisions.* Thus, to get better economic decision-making from our elected officials, a good intermediate step would be to make our tax system more progressive or expand Medicare or Social Security or…Well, we have a lot of good options here. Of course, for mathematically minded thinkers, this begs the following question: if we could enact so-called progressive economic policies to cure our political crisis, why haven’t we done so already? What can/must change for us to do so in the future? While I believe that the answer to this question is provided by another essay in the book, let’s take a closer look at KW’s explanation at how wealth inequality throws sand into the gears of our polity. They propose four and the following number scheme is mine:

1. The most likely explanation of the relationship between inequality and polarization is that the increased income and wealth of a small minority has, in effect bought the allegiance of a major political party…Needless to say, this is not an environment conducive to political action.

2. It seems likely that this persistence [of financial deregulation] despite repeated disasters had a lot do with rising inequality, with the causation running in both directions. On the one side the explosive growth of the financial sector was a major source of soaring incomes at the very top of the income distribution. On the other side, the fact that the very rich were the prime beneficiaries of deregulation meant that as this group gained power- simply because of its rising wealth- the push for deregulation intensified. These impacts of inequality on ideology did not in 2008…[they] left us incapacitated in the face of crisis.

3. Conservatives have always seen seen [Keynesian economics] as the thin edge of the wedge: concede that the government can play a useful role in fighting slumps, and the next thing you know we’ll be living under socialism.

4. [Krugman paraphrasing Kalecki] Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment to a great extend on the so-called state of confidence….This gives capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.

All of these are true to an extent. Two are related to the features of a particular policy position that conservatives don’t like (countercyclical spending) and their cost will dissipate if the economy improves. Isn’t it the case that most proponents and beneficiaries of financial liberalization are Democrats? (Wall Street mostly supported Obama in 08 and barely supported Romney in 12 despite Romney giving the house away). In any case, while KW aren’t big on solutions they certainly have a strong grasp of the problem.

Take a Stand: Sit In by Phillip Dray

As the railroad strike of 1877 had led eventually to expanded workers’ rights, so the Greensboro sit-in of February 1, 1960, helped pave the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both movements remind us that not all successful protests are explicit in their message and purpose; they rely instead on the participants’ intuitive sense of justice. [28]

I’m not the only author to have taken note of this passage as particularly important, but I am the only author who found the passage significant and did not start ranting about so-called “natural law.” Chronicling the (hitherto unknown-to-me) history of the Great Upheaval, Dray does a great job relating some important moments in left protest history to the OWS history. This is actually an extremely important essay and I haven’t given it the time it deserves. If you read three essays in this book, include this in your list.

Inequality and Intemperate Policy by Raghuram Rajan (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

Rajan’s basic ideas are the following: inequality has gotten out of control:

Deepening income inequality has been brought to the forefront of discussion in the United States. The discussion tends to center on the Croesus-like income of John Paulson, the hedge fund manager who made a killing in 2008 betting on a financial collapse and netted over $3 billion, about seventy-five-thousand times the average household income. Yet a more worrying, everyday phenomenon that confronts most Americans is the disparity in income growth rates between a manager at the local supermarket and the factory worker or office assistant. Since the 1970s, the wages of the former, typically workers at the ninetieth percentile of the wage distribution in the United States, have grown much faster than the wages of the latter, the typical median worker.

But American political ideologies typically rule out the most direct responses to inequality (i.e. redistribution). The result is a series of stop-gap measures that do long-run damage to the economy (as defined by sustainable and rising income levels and full employment), but temporarily boost the consumption level of lower classes:

It is not surprising then, that a policy response to rising inequality in the United States in the 1990s and 200s – whether carefully planned or chosen as the path of least resistance – was to encourage lending to households, especially but not exclusively low-income ones, with the government push given to housing credit just the most egregious example. The benefit – higher consumption – was immediate, whereas paying the inevitable bill could be postponed into the future. Indeed, consumption inequality did not grow nearly as much as income inequality before the crisis. The difference was bridged by debt. Cynical as it may seem, easy credit has been used as a palliative success administrations that been unable to address the deeper anxieties of the middle class directly. As I argue in my book Fault Lines, “Let them eat credit” could well summarize the mantra of the political establishment in the go-go years before the crisis.

Why should you believe Raghuram Rajan? Because he’s one of the few guys who called the first crisis and tried to warn the Fed.

A solid essay providing a more direct link between income inequality and bad policy than KW do.

The 5 Percent by Michael Hiltzik

The 5 percent’s [consisting of the seven million Americans who, in 1934, were sixty-five and older] protests coalesced as the Townsend movement, launched by a sinewy midwestern farmer’s son and farm laborer turned California physician. Francis Townsend was a World War I veteran who had served in the Army Medical Corps. He had an ambitious, and impractical plan for a federal pension program. Although during its heyday in the 1930s the movement failed to win enactment of its [editor’s note: insane] program, it did play a critical role in contemporary politics. Before Townsend, America understood the destitution of its older generations only in abstract terms; Townsend’s movement made it tangible. “It is no small achievment to have opened the eyes of even a few million Americans to these facts,” Bruce Bliven, editor of the New Republic observed. “If the Townsend Plan were to die tomorrow and be completely forgotten as miniature golf, mah-jongg, or flinch [editor’s note: everything old is new again], it would still have left some sedimented flood marks on the national consciousness.” Indeed, the Townsend movement became the catalyst for the New Deal’s signal achievement, the old-age program of Social Security. The history of its rise offers a lesson for the Occupy movement in how to convert grassroots enthusiasm into a potent political force – and a warning about the limitations of even a nationwide movement.

Does the author live up to the promises of this paragraph? Is the whole essay worth reading? Does FDR give in to the people’s demands and pass Social Security?!

Yes to all. Read it.

Hidden in Plain Sight by Gillian Tett (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

This is a great essay. I’m going to outsource the review and analysis to:

http://beyoubesure.com/2012/10/13/generation-lost-lazy-afraid/

because it basically sums up my thoughts. You all, go read it.

What Good is Wall Street? by John Cassidy

If you know nothing about Wall Street, then the essay is worth reading, otherwise skip it. There are two common ways to write a bad article in financial journalism. First, you can try to explain tiny index price movements via news articles from that day/week/month. “Shares in the S&P moved up on good news in Taiwan today,” that kind of nonsense. While the news and price movements might be worth knowing for their own sake, these articles are usually worthless because no journalist really knows who traded and why (theorists might point out even if the journalists did know who traded to generate the movement and why, it’s not clear these articles would add value – theorists are correct).

The other way, the Cassidy! way is to ask some subgroup of American finance what they think about other subgroups in finance. High frequency traders think iBankers are dumb and overpaid, but HFT on the other hand, provides an extremely valuable service – keeping ETFs cheap, providing liquidity and keeping shares the right level. iBankers think prop-traders add no value, but that without iBanking M&A services, American manufacturing/farmers/whatever would cease functioning. Low speed prop-traders think that HFT just extracts cash from dumb money, but prop-traders are reddest blooded American capitalists, taking the right risks and bringing knowledge into the markets. Insurance hates hedge funds, hedge funds hate the bulge bracket, the bulge bracket hates the ratings agencies, who hate insurance and on and on.

You can spit out dozens of articles about these catty and tedious rivalries (invariably claiming that financial sector X, rivals for institutional cash with Y, “adds no value”) and learn nothing about finance. Cassidy writes the article taking the iBankers side and surprises no one (this was originally published as an article in The New Yorker).

Your House as an ATM by Bethany McLean

Ms. McLean holds immense talent. It was always pretty obvious that the bottom twenty-percent, i.e. the vast majority of subprime loan recipients, who are generally poor at planning, were using mortgages to get quick cash rather than buy houses. Regulators and high finance, after resisting for a good twenty years, gave in for reasons explained in Rajan’s essay.

Against Political Capture by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (sorry I couldn’t find a URL, for this original essay you’ll have to buy the book).

A legit essay by a future Nobelist in Econ. Read it.

A Nation of Business Junkies by Arjun Appadurai

Anthro-hack Appadurai writes:

I first came to this country in 1967. I have been either a crypto-anthropologist or professional anthropologist for most of the intervening years. Still, because I came here with an interest in India and took the path of least resistance in choosing to retain India as my principal ethnographic referent, I have always been reluctant to offer opinions about life in these United States.

His instincts were correct. The essay reads like an old man complaining about how bad the weather is these days. Skip it.

Causes of Financial Crises Past and Present: The Role of This-Time-Is-Different Syndrome by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff

Editor Byrne has amazing powers of persuasion or, a lot of authors have had some essays in the desk-drawer they were waiting for an opportunity to publish. In any case, Rogoff and Reinhart (RR hereafter) have summed up a couple hundred studies and two of their books in a single executive summary and given it to whoever buys The Occupy Handbook. Value. RR are Republicans and the essay appears to be written in good faith (unlike some people *cough* Tyler Cowen and Veronique de Rugy *cough*). RR do a great job discovering and presenting stylized facts about financial crises past and present. What to expect next? A couple national defaults and maybe a hyperinflation or two.

Government As Tough Love by Robert Shiller as interviewed by Brandon Adams (buy the book)!

Shiller has always been ahead of the curve. In 1981, he wrote a cornerstone paper in behavioral finance at a time when the field was in its embryonic stages. In the early 1990s, he noticed insufficient attention was paid to real estate values, despite their overwhelming importance to personal wealth levels; this led him to create, along with Karl E. Case, the Case-Shiller index – now the Case-Shiller Home Prices Indices. In March 2000**, Shiller published Irrational Exuberance, arguing that U.S. stocks were substantially overvalued and due for a tumble. [Editor’s note: what Brandon Adams fails to mention, but what’s surely relevant is that Shiller also called the subprime bubble and re-released Irrational Exuberance in 2005 to sound the alarms a full three years before The Subprime Solution]. In 2008, he published The Subprime Solution, which detailed the origins of the housing crisis and suggested innovative policy responses for dealing with the fallout. These days, one of his primary interests is neuroeconomics, a field that relates economic decision-making to brain function as measured by fMRIs.

Shiller is basically a champ and you should listen to him.

Shiller was disappointed but not surprised when governments bailed out banks in extreme fashion while leaving the contracts between banks and homeowners unchanged. He said, of Hank Paulson, “As Treasury secretary, he presented himself in a very sober and collected way…he did some bailouts that benefited Goldman Sachs, among others. And I can imagine that they were well-meaning, but I don’t know that they were totally well-meaning, because the sense of self-interest is hard to clean out of your mind.”

Shiller understates everything.

Verdict: Read it.

And so, we close our discussion of part I. Moving on to part II:

In Ms. Byrne’s own words:

Part 2, “Where We Are Now,” which covers the present, both in the United States and abroad, opens with a piece by the anthropologist David Graeber. The world of Madison Avenue is far from the beliefs of Graeber, an anarchist, but it’s Graeber who arguably (he says he didn’t do it alone) came up with the phrase “We Are the 99 percent.” As Bloomberg Businessweek pointed out in October 2011, during month two of the Occupy encampments that Graeber helped initiate and three moths after the publication of his Debt: The First 5,000 Years, “David Graeber likes to say that he had three goals for the year: promote his book, learn to drive, and launch a worldwide revolution. The first is going well, the second has proven challenging and the third is looking up.” Graeber’s counterpart in Chile can loosely be said to be Camila Vallejo, the college undergraduate, pictured on page 219, who, at twenty-three, brought the country to a standstill. The novelist and playwright Ariel Dorfman writes about her and about his own self-imposed exile from Chile, and his piece is followed by an entirely different, more quantitative treatment of the subject. This part of the book also covers the indignados in Spain, who before Occupy began, “occupied” the public squares of Madrid and other cities – using, as the basis for their claim on the parks could be legally be slept in, a thirteenth-century right granted to shepherds who moved, and still move, their flocks annually.

In other words, we’re in occupy is the hero we deserve, but not the hero we need territory here.

*Addendum 1: Some have suggested that it’s not the wealth inequality that ought to be reduced, but the democratic elements of our system. California’s terrible decision–making resulting from its experiments with direct democracy notwithstanding, I would like to stay in the realm of the sane.

**Addendum 2: Yes, Shiller managed to get the book published the week before the crash. Talk about market timing.

Guest Post SuperReview Part II of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I: How We Got Here

Whatsup.

This is a review of Part I of The Occupy Handbook. Part I consists of twelve pieces ranging in quality from excellent to awful. But enough from me, in Janet Byrne’s own words:

Part 1, “How We Got Here,” takes a look at events that may be considered precursors of OWS: the stories of a brakeman in 1877 who went up against the railroads; of the four men from an all-black college in North Carolina who staged the first lunch counter sit-in of the 1960s; of the out-of-work doctor whose nationwide, bizarrely personal Townsend Club movement led to the passage of Social Security. We go back to the 1930s and the New Deal and, in Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff‘s “nutshell” version of their book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, even further.

Ms. Byrne did a bang-up job getting one Nobel Prize Winner in economics (Paul Krugman), two future Economics Nobel Prize winners (Robert Shiller, Daron Acemoglu) and two maybes (sorry Raghuram Rajan and Kenneth Rogoff) to contribute excellent essays to this section alone. Powerhouse financial journalists Gillian Tett, Michael Hilztik, John Cassidy, Bethany McLean and the prolific Michael Lewis all drop important and poignant pieces into this section. Arrogant yet angry anthropologist Arjun Appadurai writes one of the worst essays I’ve ever had the misfortune of reading and the ubiquitous Brandon Adams make his first of many mediocre appearances interviewing Robert Shiller. Clocking in at 135 pages, this is the shortest section of the book yet varies the most in quality. You can skip Professor Appadurai and Cassidy’s essays, but the rest are worth reading.

Advice from the 1 Percent: Lever Up, Drop Out by Michael Lewis

Framed as a strategy memo circulated among one-percenters, Lewis’ satirical piece written after the clearing of Zucotti Park begins with a bang.

The rabble has been driven from the public parks. Our adversaries, now defined by the freaks and criminals among them, have demonstrated only that they have no idea what they are doing. They have failed to identify a single achievable goal.

Indeed, the absurd fixation on holding Zuccotti Park and refusal to issue demands because doing so “would validate the system” crippled Occupy Wall Street (OWS). So far OWS has had a single, but massive success: it shifted the conversation back to the United States’ out of control wealth inequality managed to do so in time for the election, sealing the deal on Romney. In this manner, OWS functioned as a holding action by the 99% in the interests of the 99%.

We have identified two looming threats: the first is the shifting relationship between ambitious young people and money. There’s a reason the Lower 99 currently lack leadership: anyone with the ability to organize large numbers of unsuccessful people has been diverted into Wall Street jobs, mainly in the analyst programs at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Those jobs no longer exist, at least not in the quantities sufficient to distract an entire generation from examining the meaning of their lives. Our Wall Street friends, wounded and weakened, can no longer pick up the tab for sucking the idealism out of America’s youth.We on the committee are resigned to all elite universities becoming breeding grounds for insurrection, with the possible exception of Princeton.

Michael Lewis speaks from experience; he is a Princeton alum and a 1 percenter himself. More than that however, he is also a Wall Street alum from Salomon Brothers during the 1980s snafu and wrote about it in the original guide to Wall Street, Liar’s Poker. Perhaps because of his atypicality (and dash of solipsism), he does not have a strong handle on human(s) nature(s). By the time of his next column in Bloomberg, protests had broken out at Princeton.

Ultimately ineffectual, but still better than…

Lewis was right in the end, but more than anyone sympathetic to the movement might like. OccupyPrinceton now consists of only two bloggers, one of which has graduated and deleted all his work from an already quiet site and another who is a senior this year. OccupyHarvard contains a single poorly written essay on the front page. Although OccupyNewHaven outlasted the original Occupation, Occupy Yale no longer exists. Occupy Dartmouth hasn’t been active for over a year, although it has a rather pathetic Twitter feed here. Occupy Cornell, Brown, Caltech, MIT and Columbia don’t exist, but some have active facebook pages. Occupy Michigan State, Rutgers and NYU appear to have had active branches as recently as eight months ago, but have gone silent since. Functionally, Occupy Berkeley and its equivalents at UCBerkeley predate the Occupy movement and continue but Occupy Stanford hasn’t been active for over a year. Anecdotally, I recall my friends expressing some skepticism that any cells of the Occupy movement still existed.

As for Lewis’ other points, I’m extremely skeptical about “examined lives” being undermined by Wall Street. As someone who started in math and slowly worked his way into finance, I can safely say that I’ve been excited by many of the computing, economic, and theoretical problems quants face in their day-to-day work and I’m typical. I, and everyone who has lived long-enough, knows a handful of geniuses who have thought long and hard about the kinds of lives they want to lead and realized that A. there is no point to life unless you make one and B. making money is as good a point as any. I know one individual, after working as a professional chemist prior to college,who decided to in his words, “fuck it and be an iBanker.” He’s an associate at DB. At elite schools, my friend’s decision is the rule rather than the exception, roughly half of Harvard will take jobs in finance and consulting (for finance) this year. Another friend, an exception, quit a promising career in operations research to travel the world as a pick-up artist. Could one really say that either the operations researcher or the chemist failed to examine their lives or that with further examinations they would have come up with something more “meaningful”?

One of the social hacks to give lie to Lewis-style idealism-emerging-from-an attempt-to-examine-ones-life is to ask freshpeople at Ivy League schools what they’d like to do when they graduate and observe their choices four years later. The optimal solution for a sociopath just admitted to a top school might be to claim they’d like to do something in the peace corp, science or volunteering for the social status. Then go on to work in academia, finance, law or tech or marriage and household formation with someone who works in the former. This path is functionally similar to what many “average” elite college students will do, sociopathic or not. Lewis appears to be sincere in his misunderstanding of human(s) nature(s). In another book he reveals that he was surprised at the reaction to Liar’s Poker – most students who had read the book “treated it as a how-to manual” and cynically asked him for tips on how to land analyst jobs in the bulge bracket. It’s true that there might be some things money can’t buy, but an immensely pleasurable, meaningful life do not seem to be one of them. Today for the vast majority of humans in the Western world, expectations of sufficient levels of cold hard cash are necessary conditions for happiness.

In short and contra Lewis, little has changed. As of this moment, Occupy has proven so harmless to existing institutions that during her opening address Princeton University’s president Shirley Tilghman called on the freshmen in the class of 2016 to “Occupy” Princeton. No freshpeople have taken up her injunction. (Most?) parts of Occupy’s failure to make a lasting impact on college campuses appear to be structural; Occupy might not have succeeded even with better strategy. As the Ivy League became more and more meritocratic and better at discovering talent, many of the brilliant minds that would have fallen into the 99% and become its most effective advocates have been extracted and reached their so-called career potential, typically defined by income or status level. More meritocratic systems undermine instability by making the most talented individuals part of the class-to-be-overthrown, rather than the over throwers of that system. In an even somewhat meritocratic system, minor injustices can be tolerated: Asians and poor rural whites are classes where there is obvious evidence of discrimination relative to “merit and the decision to apply” in elite gatekeeper college admissions (and thus, life outcomes generally) and neither group expresses revolutionary sentiment on a system-threatening scale, even as the latter group’s life expectancy has begun to decline from its already low levels. In the contemporary United States it appears that even as people’s expectations of material security evaporate, the mere possibility of wealth bolsters and helps to secure inequities in existing institutions.

Lewis continues:

Hence our committee’s conclusion: we must be able to quit American society altogether, and they must know it.The modern Greeks offer the example in the world today that is, the committee has determined, best in class. Ordinary Greeks seldom harass their rich, for the simple reason that they have no idea where to find them. To a member of the Greek Lower 99 a Greek Upper One is as good as invisible.

He pays no taxes, lives no place and bears no relationship to his fellow citizens. As the public expects nothing of him, he always meets, and sometimes even exceeds, their expectations. As a result, the chief concern of the ordinary Greek about the rich Greek is that he will cease to pay the occasional visit.

Michael Lewis is a wise man.

I can recall a conversation with one of my Professors; an expert on Democratic Kampuchea (American: Khmer Rouge), she explained that for a long time the identity of the oligarchy ruling the country was kept secret from its citizens. She identified this obvious subversion of republican principles (how can you have control over your future when you don’t even know who runs your region?) as a weakness of the regime. Au contraire, I suggested, once you realize your masters are not gods, but merely humans with human characteristics, that they: eat, sleep, think, dream, have sex, recreate, poop and die – all their mystique, their claims to superior knowledge divine or earthly are instantly undermined. De facto segregation has made upper classes in the nation more secure by allowing them to hide their day-to-day opulence from people who have lost their homes, job and medical care because of that opulence. Neuroscience will eventually reveal that being mysterious makes you appear more sexy, socially dominant, and powerful, thus making your claims to power and dominance more secure (Kautsky et. al. 2018).*

If the majority of Americans manage to recognize that our two tiered legal system has created a class whose actual claim to the US immense wealth stems from, for the most part, a toxic combination of Congressional pork, regulatory and enforcement agency capture and inheritance rather than merit, there will be hell to pay. Meanwhile, resentment continues to grow. Even on the extreme right one can now regularly read things like:

Now, I think I’d be downright happy to vote for the first politician to run on a policy of sending killer drones after every single banker who has received a post-2007 bonus from a bank that received bailout money. And I’m a freaking libertarian; imagine how those who support bombing Iraqi children because they hate us for our freedoms are going to react once they finally begin to grasp how badly they’ve been screwed over by the bankers. The irony is that a banker-assassination policy would be entirely constitutional according to the current administration; it is very easy to prove that the bankers are much more serious enemies of the state than al Qaeda. They’ve certainly done considerably more damage.

Wise financiers know when it’s time to cash in their chips and disappear. Rarely, they can even pull it off with class.

The rest of part I reviewed tomorrow. Hang in there people.

Addendum 1: If your comment amounts to something like “the Nobel Prize in Economics is actually called the The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel” and thus “not a real Nobel Prize” you are correct, yet I will still delete your comment and ban your IP.

*Addendum 2: More on this will come when we talk about the Saez-Delong discussion in part III.

A blogging parliament

Last night I found myself watching Steve Waldman’s talk at the 2011 Economic Bloggers Forum at the Kaufman Foundation. I’m a big fan of Waldman’s blog Interfluidity. His talk was interesting and thought-provoking, like his writing. I suggest you watch it.

After expressing outrage at the failure of control systems and the political system after the financial crisis, Waldman asks the question, why are we where we are? His answer: there’s a monopoly of power in this country even as information itself is increasingly available. The monopoly of power is extremely correlated, of course, to the rising wealth inequality, beautifully visualized in this recent video (h/t Leon Kautsky, Debika Shome) by Politizane.

The solution, he hopes, may include the blogosphere (although it’s not a perfect place either, with its own revolving doors, weird incentives and possibly conflicts of interest). The work of bloggers is valuable social capital, Steve argues, so how do we deploy it?

Steve introduced the concept of policy entrepreneurs, which have three characteristics:

- They are sources of information in the form policy ideas. They possible even write laws.

- They have some kind of certification in order to cover the policy maker’s ass.

- They exert some kind of influence on policy makers, to create incentives for their policy goals.

In other words, a policy entrepreneur is someone in the business of shaping policy makers’ agendas.

If you stop there, you might think “lobbyist,” and you’d be right. But the problem with our current lobbyist system is not the above three characteristics, but rather that it’s a such a closed system. In other words, you essentially need to be rich to be an influential lobbyist (or at least, as an influential lobbyist, you are backed by enormous wealth), but then that increases the monopolistic nature of political power. It doesn’t solve our “monopoly of power” problem.

The question becomes, is there a way for normal people, or groups of people, to be policy entrepreneurs?

One possible solution, Waldman suggests, is to from a parliament of bloggers. Since groups are taken seriously, can bloggers form official groups in which they gain consensus around a topic and issue policy?

An intriguing idea, and I like it because it’s not really abstract: if bloggers decided to try this, they could literally just form a group, call ourselves a name, and start issuing policy proposals. Of course they’d probably not get anywhere unless we had influence or leverage.

Does something like this already exist? The closest thing I can think of is the hacker group Anonymous – although they might not be bloggers, they might be. They’re anonymous. I’m going to guess they are active on the web even if they don’t specifically blog. In any case, let’s see if they qualify as policy entrepreneurs in the above sense.

- They don’t issue specific policy proposals, but they certainly object clearly to policies they don’t like.

- Their credentials lie in their unparalleled ability to take control of information systems.

- Likewise, their leverage is fierce in this domain.

In all, I don’t think Anonymous fits the bill – they’re too devoted to anarchy to deliver policy in the sense that Waldman suggests, and their tools are too crude to make fine points. This might have to do with the nature of hackers in general (keeping in mind that Anonymous stand for something far more extreme than the average hacker), which I read about in an essay by Paul Graham yesterday (h/t Chris Wiggins):

Here’s another problem: aren’t bloggers in general kind of their own 1%? Is policy via a “parliament of bloggers” not enough of an improvement to the current system of insiders?

What about if Occupy got into the idea of being a vehicle of policy entrepreneurship? Even though we tend not to support specific political candidates in Occupy, we do consistently think about policy and decide whether to endorse a given bill or policy proposal. Could we, instead of commenting on existing policy, start thinking about proposing new policy, even to the point of writing new laws?

On the one hand such work requires enormously long discussions and difficult-to-obtain consensus, but on the other hand we have the knowledge, the abilities, and the moral persuasion. Do we have the influence? And would Occupiers think exerting influence on policy in the current corrupt system tantamount to selling out?