Archive

The problem with charter schools

Today I read this article written by Allie Gross (hat tip Suresh Naidu), a former Teach for America teacher whose former idealism has long been replaced by her experiences in the reality of education in this country. Her article is entitled The Charter School Profiteers.

It’s really important, and really well written, and just one of the articles in the online magazine Jacobin that I urge you to read and to subscribe to. In fact that article is part of a series (here’s another which focuses on charter schools in New Orleans) and it comes with a booklet called Class Action: An Activist Teacher’s Handbook. I just ordered a couple of hard copies.

I’d really like you to read the article, but as a teaser here’s one excerpt, a rant which she completely backs up with facts on the ground:

You haven’t heard of Odeo, the failed podcast company the Twitter founders initially worked on? Probably not a big deal. You haven’t heard about the failed education ventures of the person now running your district? Probably a bigger deal.

When we welcome schools that lack democratic accountability (charter school boards are appointed, not elected), when we allow public dollars to be used by those with a bottom line (such as the for-profit management companies that proliferate in Michigan), we open doors for opportunism and corruption. Even worse, it’s all justified under a banner of concern for poor public school students’ well-being.

While these issues of corruption and mismanagement existed before, we should be wary of any education reformer who claims that creating an education marketplace is the key to fixing the ills of DPS or any large city’s struggling schools. Letting parents pick from a variety of schools does not weed out corruption. And the lax laws and lack of accountability can actually exacerbate the socioeconomic ills we’re trying to root out.

Nerding out: RSA on an iPython Notebook

Yesterday was a day filled with secrets and codes. In the morning, at The Platform, we had guest speaker Columbia history professor Matthew Connelly, who came and talked to us about his work with declassified documents. Two big and slightly depressing take-aways for me were the following:

- As records have become digitized, it has gotten easy for people to get rid of archival records in large quantities. Just press delete.

- As records have become digitized, it has become easy to trace the access of records, and in particular the leaks. Connelly explained that, to some extent, Obama’s harsh approach to leakers and whistleblowers might be explained as simply “letting the system work.” Yet another way that technology informs the way we approach human interactions.

After class we had section, in which we discussed the Computer Science classes some of the students are taking next semester (there’s a list here) and then I talked to them about prime numbers and the RSA crypto system.

I got really into it and wrote up an iPython Notebook which could be better but is pretty good, I think, and works out one example completely, encoding and decoding the message “hello”.

The underlying file is here but if you want to view it on the web just go here.

How to think like a microeconomist

Yesterday we were pleased to have Suresh Naidu guest lecture in The Platform. He came in and explained, very efficiently because he was leaving at 11am for a flight at noon at LGA (which he made!!) how to think like an economist. Or at least an applied microeconomist. Here are his notes:

Applied microeconomics is basically organized a few simple metaphors.

- People respond to incentives.

- A lot of data can be understood through the lens of supply and demand.

- Causality is more important than prediction.

There was actually more on the schedule, but Suresh got into really amazing examples to explain the above points and we ran out of time. At some point, when he was describing itinerant laborers in the United Arab Emirates, and looking at pay records and even visiting a itinerant labor camp, I was thinking that Suresh is possibly an undercover hardcore data journalist as well as an amazing economist.

As far as the “big data” revolution goes, we got the impression from Suresh that microeconomists have been largely unmoved by its fervor. For one, they’ve been doing huge analyses with large data sets for quite a while. But the real reason they’re unmoved, as I infer from his talk yesterday, is that big data almost always focuses on descriptions of human behavior, and sometimes predictions, and almost never causality, which is what economists care about.

A side question: why is it that economists only care about causality? Well they do, and let’s take that as a given.

So, now that we know how to think like an economist, let’s read this “Room For Debate” about overseas child labor with our new perspective. Basically the writers, or at least three out of four of them, are economists. So that means they care about “why”. Why is there so much child labor overseas? How can the US help?

The first guy says that strong unions and clear signals from American companies works, so the US should do its best to encourage the influence of labor unions.

The lady economist says that bans on child labor are generally counterproductive, so we should give people cash money so they won’t have to send their kids to work in the first place.

The last guy says that we didn’t even stop having child labor in our country until wage workers were worried about competition from children. So he wants the U.S. to essentially ignore child labor in other countries, which he claims will set the stage for other countries to have that same worry and come to the same conclusion by themselves. Time will help, as well as good money from the US companies.

So the economists don’t agree, but they all share one goal: to figure out how to tweak a tweakable variable to improve a system. And hopefully each hypothesis can be proven with randomized experiments and with data, or at least evidence can be gathered for or against.

One more thing, which I was relieved to hear Suresh say. There’s a spectrum of how much people “believe” in economics, and for that matter believe in data that seems to support a theory or experiment, and that spectrum is something that most economists run across on a daily basis. Even so, it’s not clear there’s a better way to learn things about the world than doing your best to run randomized experiments, or find close-to-randomized experiments and see how what they tell you.

Two great articles about standardized tests

In the past 12 hours I’ve read two fascinating articles about the crazy world of standardized testing. They’re both illuminating and well-written and you should take a look.

First, my data journalist friend Meredith Broussard has an Atlantic piece called Why Poor Schools Can’t Win At Standardized Testing wherein she tracks down the money and the books in the Philadelphia public school system (spoiler: there’s not enough of either), and she makes the connection between expensive books and high test scores.

Here’s a key phrase from her article:

Pearson came under fire last year for using a passage on a standardized test that was taken verbatim from a Pearson textbook.

The second article, in the New Yorker, is written by Rachel Aviv and is entitled Wrong Answer. It’s a close look, with interviews, of the cheating scandal from Atlanta, which I have been studying recently. The article makes the point that cheating is a predictable consequence of the high-stakes “data-driven” approach.

Here’s a key phrase from the Aviv article:

After more than two thousand interviews, the investigators concluded that forty-four schools had cheated and that a “culture of fear, intimidation and retaliation has infested the district, allowing cheating—at all levels—to go unchecked for years.” They wrote that data had been “used as an abusive and cruel weapon to embarrass and punish.”

Putting the two together, it’s pretty clear that there’s an acceptable way to cheat, which is by stocking up on expensive test prep materials in the form of testing company-sponsored textbooks, and then there’s the unacceptable way to cheat, which is where teachers change the answers. Either way the standardized test scoring regime comes out looking like a penal system rather than a helpful teaching aid.

Before I leave, some recent goodish news on the standardized testing front (hat tip Eugene Stern): Chris Christie just reduced the importance of value-added modeling for teacher evaluation down to 10% in New Jersey.

The Lede Program students are rocking it

Yesterday was the end of the first half of the Lede Program, and the students presented their projects, which were really impressive. I am hoping some of them will be willing to put them up on a WordPress site or something like that in order to showcase them and so I can brag about them more explicitly. Since I didn’t get anyone’s permission yet, let me just say: wow.

During the second half of the program the students will do another project (or continue their first) as homework for my class. We’re going to start planning for that on the first day, so the fact that they’ve all dipped their toes into data projects is great. For example, during presentations yesterday I heard the following a number of times: “I spent most of my time cleaning my data” or “next time I will spend more time thinking about how to drill down in my data to find an interesting story”. These are key phrases for people learning lessons with data.

Since they are journalists (I’ve learned a thing or two about journalists and their mindset in the past few months) they love projects because they love deadlines and they want something they can add to their portfolio. Recently they’ve been learning lots of geocoding stuff, and coming up they’ll be learning lots of algorithms as well. So they’ll be well equipped to do some seriously cool shit for their final project. Yeah!

In addition to the guest lectures I’m having in The Platform, I’ll also be reviewing prerequisites for the classes many of them will be taking in the Computer Science department in the fall, so for example linear algebra, calculus, and basic statistics. I just bought them all a copy of How to Lie with Statistics as well as The Cartoon Guide to Statistics, both of which I adore. I’m also making them aware of Statistics Done Wrong, which is online. I am also considering The Cartoon Guide to Calculus, which I have but I haven’t read yet.

Keep an eye out for some of their amazing projects! I’ll definitely blog about them once they’re up.

What constitutes evidence?

My most recent Slate Money podcast with Felix Salmon and Jordan Weissmann was more than usually combative. I mean, we pretty much always have disagreements, but Friday it went beyond the usual political angles.

Specifically, Felix thought I was jumping too quickly towards a dystopian future with regards to medical data. My claim was that, now that the ACA has motivated hospitals and hospital systems to keep populations healthy – a good thing in itself – we’re seeing dangerous side-effects involving the proliferation of health profiling and things like “health scores” attached to people much like we now have credit scores. I’m worried that such scores, which are created using data not covered under HIPAA, will be used against people when they try to get a job.

Felix asked me to point to evidence of such usage.

Of course, it’s hard to do that, partly because it’s just the beginning of such data collection – although the FTC’s recent report pointed to data warehouses that already puts people into categories such as “diabetes interest” – and also because it’s proprietary all the way down. In other words, web searches and the like are being legally collected and legally sold and then it’s legal to use risk scores or categories to filter job applications. What’s illegal is to use HIPAA-protected data such as disability status to remove someone from consideration for a job, but that’s not what’s happening.

Anyhoo, it’s made me think. Am I a conspiracy theorist for worrying about this? Or is Felix lacking imagination if he requires evidence to believe it? Or some combination? This is super important to me because if I can’t get Felix, or someone like Felix, to care about this issue, I’m afraid it will be ignored.

This kind of thing came up a second time on that same show, when Felix complained that the series of articles (for example this one from NY Magazine) talking about money laundering in New York real estate also lacked evidence. But that’s also tricky since the disclosure requirements on real estate are not tight. In other words, they are avoiding collecting evidence of money laundering, so it’s hard to complain there’s a lack of data. From my perspective the journalists investigating this article did a good job finding examples of laundering and showing it was easy to set up (especially in Delaware). But Felix wasn’t convinced.

It’s a general question I have, actually, and I’m glad to be involved with the Lede Program because it’s actually my job to think about this kind of thing, especially in the context of journalism. Namely, when do we require data – versus anecdotal evidence – to believe in something? And especially when the data is being intentionally obscured?

Guest post: What is the goal of a college calculus course?

This is a guest post by Nathan, who recently finished graduate school in math, and will begin a post-doc in the fall. He loves teaching young kids, but is still figuring out how to motivate undergraduates.

The question

Like most mathematicians in academia, I’m teaching calculus in the fall. I taught in grad school, but the syllabus and assignments were already set. This time I’ll be in charge, so I need to make some design decisions, like the following:

- Are calculators/computers/notes allowed on the exams?

- Which purely technical skills must students master (by a technical skill I mean something like expanding rational functions into partial fractions: a task which is deterministic but possibly intricate)?

- Will students need to write explanations and/or proofs?

I have some angst about decisions like these, because it seems like each one can go in very different directions depending on what I hope the students are supposed to get from the course. If I’m listing the pros and cons of permitting calculators, I need some yardstick to measure these pros and cons.

My question is: what is the goal of a college calculus course?

I’d love to have an answer that is specific enough that I can use it to make concrete decisions like the ones above. Part of my angst is that I’ve asked many people this question, including people I respect enormously for their teaching, but often end up with a muddled answer. And there are a couple stock answers that come to mind, but each one doesn’t satisfy me for one reason or another. Here’s what I have so far.

The contenders.

To teach specific tasks that are necessary for other subjects.

These tasks would include computing integrals and derivatives, converting functions to power series or Fourier series, and so forth.

Intuitive understanding of functions and their behavior.

This is vague, so here’s an example: a couple years ago, a friend in medical school showed me a page from his textbook. The page concerned whether a certain drug would affect heart function in one way or in the opposite way (it caused two opposite effects), and it showed a curve relating two involved parameters. It turned out that the essential feature was that this curve was concave down. The book did not use the phrase “concave down,” though, and had a rather wordy explanation of the behavior. In this situation, a student who has a good grasp of what concavity is and what its implications are is better equipped to understand the effect described in the book. So if a student has really learned how to think about concavity of functions and its implications, then she can more quickly grasp the essential parts of this medical situation.

To practice communicating with precision.

I’m taking “communication” in a very wide sense here: carefully showing the steps in an integral calculation would count.

Not Satisfied

I have issues with each of these as written. I don’t buy number 1, because the bread and butter of calculus class, like computing integrals, isn’t something most doctors or scientists will ever do again. Number 2 is a noble goal, but it’s overly idealistic; if this is the goal, then our success rate is less than 10%. Number 3 also seems like a great goal, relevant for most of the students, but I think we’d have to write very different sorts of assignments than we currently do if we really want to aim for it.

I would love to have a clear and realistic answer to this question. What do you think?

Correlation does not imply equality

One of the reasons I enjoy my blog is that I get to try out an argument and then see if readers can 1) poke holes in my arguement, or 2) if they misunderstand my argument, or 3) if they misunderstand something tangential to my argument.

Today I’m going to write about an issue of the third kind. Yesterday I talked about how I’d like to see the VAM scores for teachers directly compared to other qualitative scores or other VAM scores so we could see how reliably they regenerate various definitions of “good teaching.”

The idea is this. Many mathematical models are meant to replace a human-made model that is deemed too expensive to work out at scale. Credit scores were like that; take the work out of the individual bankers’ hands and create a mathematical model that does the job consistently well. The VAM was originally intended as such – in-depth qualitative assessments of teachers is expensive, so let’s replace them with a much cheaper option.

So all I’m asking is, how good a replacement is the VAM? Does it generate the same scores as a trusted, in-depth qualitative assessment?

When I made the point yesterday that I haven’t seen anything like that, a few people mentioned studies that show positive correlations between the VAM scores and principal scores.

But here’s the key point: positive correlation does not imply equality.

Of course sometimes positive correlation is good enough, but sometimes it isn’t. It depends on the context. If you’re a trader that makes thousands of bets a day and your bets are positively correlated with the truth, you make good money.

But on the other side, if I told you that there’s a ride at a carnival that has a positive correlation with not killing children, that wouldn’t be good enough. You’d want the ride to be safe. It’s a higher standard.

I’m asking that we make sure we are using that second, higher standard when we score teachers, because their jobs are increasingly on the line, so it matters that we get things right. Instead we have a machine that nobody understand that is positively correlated with things we do understand. I claim that’s not sufficient.

Let me put it this way. Say your “true value” as a teacher is a number between 1 and 100, and the VAM gives you a noisy approximation of your value, which is 24% correlated with your true value. And say I plot your value against the approximation according to VAM, and I do that for a bunch of teachers, and it looks like this:

So maybe your “true value” as a teacher is 58 but the VAM gave you a zero. That would not just be frustrating to you, since it’s taken as an important part of your assessment. You might even lose your job. And you might get a score of zero many years in a row, even if your true score stays at 58. It’s increasingly unlikely, to be sure, but given enough teachers it is bound to happen to a handful of people, just by statistical reasoning, and if it happens to you, you will not think it’s unlikely at all.

So maybe your “true value” as a teacher is 58 but the VAM gave you a zero. That would not just be frustrating to you, since it’s taken as an important part of your assessment. You might even lose your job. And you might get a score of zero many years in a row, even if your true score stays at 58. It’s increasingly unlikely, to be sure, but given enough teachers it is bound to happen to a handful of people, just by statistical reasoning, and if it happens to you, you will not think it’s unlikely at all.

In fact, if you’re a teacher, you should demand a scoring system that is consistently the same as a system you understand rather than positively correlated with one. If you’re working for a teachers’ union, feel free to contact me about this.

One last thing. I took the above graph from this post. These are actual VAM scores for the same teacher in the same year but for two different class in the same subject – think 7th grade math and 8th grade math. So neither score represented above is “ground truth” like I mentioned in my thought experiment. But that makes it even more clear that the VAM is an insufficient tool, because it is only 24% correlated with itself.

Why Chetty’s Value-Added Model studies leave me unconvinced

Every now and then when I complain about the Value-Added Model (VAM), people send me links to recent papers written Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff like this one entitled Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II: Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood or its predecessor Measuring the Impacts of Teachers I: Evaluating Bias in Teacher Value-Added Estimates.

I think I’m supposed to come away impressed, but that’s not what happens. Let me explain.

Their data set for students scores start in 1989, well before the current value-added teaching climate began. That means teachers weren’t teaching to the test like they are now. Therefore saying that the current VAM works because an retrograded VAM worked in 1989 and the 1990’s is like saying I must like blueberry pie now because I used to like pumpkin pie. It’s comparing apples to oranges, or blueberries to pumpkins.

I’m surprised by the fact that the authors don’t seem to make any note of the difference in data quality between pre-VAM and current conditions. They should know all about feedback loops; any modeler should. And there’s nothing like telling teachers they might lose their job to create a mighty strong feedback loop. For that matter, just consider all the cheating scandals in the D.C. area where the stakes were the highest. Now that’s a feedback loop. And by the way, I’ve never said the VAM scores are totally meaningless, but just that they are not precise enough to hold individual teachers accountable. I don’t think Chetty et al address that question.

So we can’t trust old VAM data. But what about recent VAM data? Where’s the evidence that, in this climate of high-stakes testing, this model is anything but random?

If it were a good model, we’d presumably be seeing a comparison of current VAM scores and current other measures of teacher success and how they agree. But we aren’t seeing anything like that. Tell me if I’m wrong, I’ve been looking around and I haven’t seen such comparisons. And I’m sure they’ve been tried, it’s not rocket science to compare VAM scores with other scores.

The lack of such studies reminds me of how we never hear about scientific studies on the results of Weight Watchers. There’s a reason such studies never see the light of day, namely because whenever they do those studies, they decide they’re better off not revealing the results.

And if you’re thinking that it would be hard to know exactly how to rate a teacher’s teaching in a qualitative, trustworthy way, then yes, that’s the point! It’s actually not obvious how to do this, which is the real reason we should never trust a so-called “objective mathematical model” when we can’t even decide on a definition of success. We should have the conversation of what comprises good teaching, and we should involve the teachers in that, and stop relying on old data and mysterious college graduation results 10 years hence. What are current 6th grade teachers even supposed to do about studies like that?

Note I do think educators and education researchers should be talking about these questions. I just don’t think we should punish teachers arbitrarily to have that conversation. We should have a notion of best practices that slowly evolve as we figure out what works in the long-term.

So here’s what I’d love to see, and what would be convincing to me as a statistician. If we see all sorts of qualitative ways of measuring teachers, and see their VAM scores as well, and we could compare them, and make sure they agree with each other and themselves over time. In other words, at the very least we should demand an explanation of how some teachers get totally ridiculous and inconsistent scores from one year to the next and from one VAM to the next, even in the same year.

The way things are now, the scores aren’t sufficiently sound be used for tenure decisions. They are too noisy. And if you don’t believe me, consider that statisticians and some mathematicians agree.

We need some ground truth, people, and some common sense as well. Instead we’re seeing retired education professors pull statistics out of thin air, and it’s an all-out war of supposed mathematical objectivity against the civil servant.

Getting rid of teacher tenure does not solve the problem

There’s been a movement to make primary and secondary education run more like a business. Just this week in California, a lawsuit funded by Silicon Valley entrepreneur David Welch led to a judge finding that student’s constitutional rights were being compromised by the tenure system for teachers in California.

The thinking is that tenure removes the possibility of getting rid of bad teachers, and that bad teachers are what is causing the achievement gap between poor kids and well-off kids. So if we get rid of bad teachers, which is easier after removing tenure, then no child will be “left behind.”

The problem is, there’s little evidence for this very real achievement gap problem as being caused by tenure, or even by teachers. So this is a huge waste of time.

As a thought experiment, let’s say we did away with tenure. This basically means that teachers could be fired at will, say through a bad teacher evaluation score.

An immediate consequence of this would be that many of the best teachers would get other jobs. You see, one of the appeals of teaching is getting a comfortable pension at retirement, but if you have no idea when you’re being dismissed, then it makes no sense to put in the 25 or 30 years to get that pension. Plus, what with all the crazy and random value-added teacher models out there, there’s no telling when your score will look accidentally bad one year and you’ll be summarily dismissed.

People with options and skills will seek other opportunities. After all, we wanted to make it more like a business, and that’s what happens when you remove incentives in business!

The problem is you’d still need teachers. So one possibility is to have teachers with middling salaries and no job security. That means lots of turnover among the better teachers as they get better offers. Another option is to pay teachers way more to offset the lack of security. Remember, the only reason teacher salaries have been low historically is that uber competent women like Laura Ingalls Wilder had no other options than being a teacher. I’m pretty sure I’d have been a teacher if I’d been born 150 years ago.

So we either have worse teachers or education doubles in price, both bad options. And, sadly, either way we aren’t actually addressing the underlying issue, which is that pesky achievement gap.

People who want to make schools more like businesses also enjoy measuring things, and one way they like measuring things is through standardized tests like achievement scores. They blame teachers for bad scores and they claim they’re being data-driven.

Here’s the thing though, if we want to be data-driven, let’s start to maybe blame poverty for bad scores instead:

I’m tempted to conclude that we should just go ahead and get rid of teacher tenure so we can wait a few years and still see no movement in the achievement gap. The problem with that approach is that we’ll see great teachers leave the profession and no progress on the actual root cause, which is very likely to be poverty and inequality, hopelessness and despair. Not sure we want to sacrifice a generation of students just to prove a point about causation.

On the other hand, given that David Welch has a lot of money and seems to be really excited by this fight, it looks like we might have no choice but to blame the teachers, get rid of their tenure, see a bunch of them leave, have a surprise teacher shortage, respond either by paying way more or reinstating tenure, and then only then finally gather the data that none of this has helped and very possibly made things worse.

Me & My Administrative Bloat

I am now part of the administrative bloat over at Columbia. I am non-faculty administration, tasked with directing a data journalism program. The program is great, and I’m not complaining about my job. But I will be honest, it makes me uneasy.

Although I’m in the Journalism School, which is in many ways separated from the larger university, I now have a view into how things got so bloated. And how they might stay that way, as well: it’s not clear that, at the end of my 6-month gig, on September 16th, I could hand my job over to any existing person at the J-School. They might have to replace me, or keep me on, with a real live full-time person in charge of this program.

There are good and less good reasons for that, but overall I think there exists a pretty sound argument for such a person to run such a program and to keep it good and intellectually vibrant. That’s another thing that makes me uneasy, although many administrative positions have less of an easy sell attached to them.

I was reminded of this fact of my current existence when I read this recent New York Times article about the administrative bloat in hospitals. From the article:

And studies suggest that administrative costs make up 20 to 30 percent of the United States health care bill, far higher than in any other country. American insurers, meanwhile, spent $606 per person on administrative costs, more than twice as much as in any other developed country and more than three times as much as many, according to a study by the Commonwealth Fund.

Compare that to this article entitled Administrators Ate My Tuition:

A comprehensive study published by the Delta Cost Project in 2010 reported that between 1998 and 2008, America’s private colleges increased spending on instruction by 22 percent while increasing spending on administration and staff support by 36 percent. Parents who wonder why college tuition is so high and why it increases so much each year may be less than pleased to learn that their sons and daughters will have an opportunity to interact with more administrators and staffers— but not more professors.

There are similarities and there are differences between the university and the medical situations.

A similarity is that people really want to be educated, and people really need to be cared for, and administrations have grown up around these basic facts, and at each stage they seem to be adding something either seemingly productive or vitally needed to contain the complexity of the existing machine, but in the end you have enormous behemoths of organizations that are much too complex and much too expensive. And as a reality check on whether that’s necessary, take a look at hospitals in Europe, or take a look at our own university system a few decades ago.

And that also points out a critical difference: the health care system is ridiculously complicated in this country, and in some sense you need all these people just to navigate it for a hospital. And ObamaCare made that worse, not better, even though it also has good aspects in terms of coverage.

Whereas the university system made itself complicated, it wasn’t externally forced into complexity, except if you count the US News & World Reports gaming that seems inescapable.

Obama has the wrong answer to student loan crisis

Have you seen Obama’s latest response to the student debt crisis (hat tip Ernest Davis)? He’s going to rank colleges based on some criteria to be named later to decide whether a school deserves federal loans and grants. It’s a great example of a mathematical model solving the wrong problem.

Now, I’m not saying there aren’t nasty leeches who are currently gaming the federal loan system. For example, take the University of Phoenix. It’s not a college system, it’s a business which extracts federal and private loan money from unsuspecting people who want desperately to get a good job some day. And I get why Obama might want to put an end to that gaming, and declare the University of Phoenix and its scummy competitors unfit for federal loans. I get it.

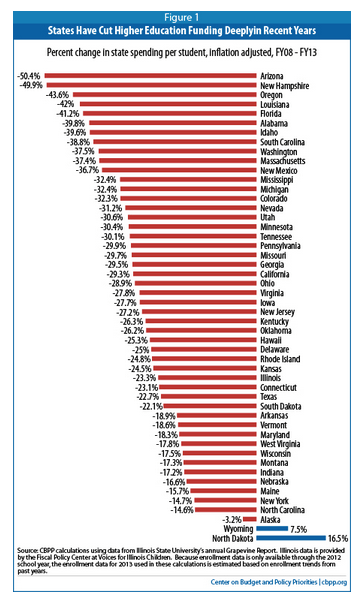

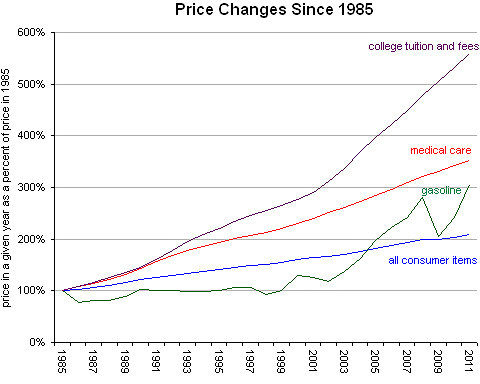

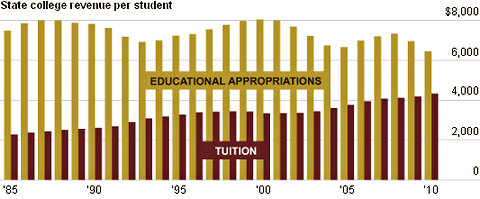

But unfortunately it won’t fix the problem. Because the real problem is the federal loan system in the first place, which has grown a shitton since I was in school:

and in the meantime, our state and private schools are getting more and more expensive relative to the available grants:

And state funding for public schools has decreased while tuition has increased especially since the financial crisis:

The bottomline is that we – and especially our children – need more state school funding much more than we need a ranking algorithm. The best way to bring down tuition rates at private schools is to give them competition at good state schools.

Great news: InBloom is shutting down

I’m trying my hardest to resist talking about Piketty’s Capital because I haven’t read it yet, even though I’ve read a million reviews and discussions about it, and I saw him a couple of weeks ago on a panel with my buddy Suresh Naidu. Suresh, who was great on the panel, wrote up his notes here.

So I’ll hold back from talking directly about Piketty, but let me talk about one of Suresh’s big points that was inspired in part by Piketty. Namely, the fact that it’s a great time to be rich. It’s even greater now to be rich than it was in the past, even when there were similar rates of inequality. Why? Because so many things have become commodified. Here’s how Suresh puts it:

We live in a world where much more of everyday life occurs on markets, large swaths of extended family and government services have disintegrated, and we are procuring much more of everything on markets. And this is particularly bad in the US. From health care to schooling to philanthropy to politicians, we have put up everything for sale. Inequality in this world is potentially much more menacing than inequality in a less commodified world, simply because money buys so much more. This nasty complementarity of market society and income inequality maybe means that the social power of rich people is higher today than in the 1920s, and one response to increasing inequality of market income is to take more things off the market and allocate them by other means.

I think about this sometimes in the field of education in particular, and to that point I’ve got a tiny bit of good news today.

Namely, InBloom is shutting down (hat tip Linda Brown). You might not remember what InBloom is, but I blogged about this company a while back in my post Big Data and Surveillance, as well as the ongoing fight against InBloom in New York state by parents here.

The basic idea is that InBloom, which was started in cooperation with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Rupert Murdoch’s Amplify, would collect huge piles of data on students and their learning and allow third party companies to mine that data to improve learning. From this New York Times article:

InBloom aimed to streamline personalized learning — analyzing information about individual students to customize lessons to them — in public schools. It planned to collect and integrate student attendance, assessment, disciplinary and other records from disparate school-district databases, put the information in cloud storage and release it to authorized web services and apps that could help teachers track each student’s progress.

It’s not unlike the idea that Uber has, of connecting drivers with people needing rides, or that AirBNB has, of connecting people needing a room with people with rooms: they are platforms, not cab companies or hoteliers, and they can use that matchmaking status as a way to duck regulations.

The problem here is that the relevant child data protection regulation, called FERPA, is actually pretty strong, and InBloom and companies like it were largely bypassing that law, as was discovered by a Fordham Law study led by Joel Reidenberg. In particular, the study found that InBloom and other companies were offering what seemed like “free” educational services, but of course the deal really was in exchange for the children’s data, and the school officials who were agreeing to the deals had no clue as to what they were signing. The parents were bypassed completely. Much of the time the contracts were in direct violation of FERPA, but often the school officials didn’t even have copies of the contracts and hadn’t heard of FERPA.

Because of that report and other bad publicity, we saw growing resistance in New York State by parents, school board members and privacy lawyers. And thanks to that resistance, New York State Legislature recently passed a budget that prohibited state education officials from releasing student data to amalgamators like inBloom. InBloom has subsequently decided to close down.

I’m not saying that the urge to privatize education – and profit off of it – isn’t going to continue after a short pause. For that matter look at the college system. Even so, let’s take a moment to appreciate the death of one of the more egregious ideas out there.

I burned my eyes reading the Wall Street Journal this morning

If you want to do yourself a favor, don’t read this editorial from the Wall Street Journal like I did. It’s an unsigned “Review & Outlook” piece which I’m guessing was written by Rupert Murdoch himself.

Entitled Telling Students to Earn Less: Obama now calls for reforming his bleeding college loan program, it’s a rant against Obama’s Pay As You Earn plan, and it’s vitriolic, illogical, and mean. It makes me honestly embarrassed for the remaining high-quality journalists working at the WSJ who have to put up with this. An excerpt:

Pay As You Earn allows students under certain circumstances to borrow an unlimited amount and then cap monthly payments at 10% of their discretionary income. If they choose productive work in the private economy, the loans are forgiven after 20 years. But if they choose to work in government or for a nonprofit, Uncle Sugar forgives their loans after 10 years.

Uncle Sugar? Is this intended to make us think about the Huckabee birth control debate?

Here’s the thing. I’m not someone who always wants people to talk about the President in hushed and solemn terms or anything. The president is fair game, as are his policies. And in Obama’s case, I am not a big fan. For that matter, I don’t think his education policy has any hope, even if it’s well-intentioned. But I just don’t understand how an article like this can be published in a respectable newspaper. It does not advance the debate.

For the record, college tuition has been going up for a while, way before Obama:

And it’s not just that tuition has been going up, at least at state school. It’s that state funding has been going down:

Next, it’s true that just supplying more loans to federal students doesn’t cut it: tuition rises to meet that ability to pay. In fact that’s part of what’s going on in the above picture.

What we have here is a feedback loop, and it’s hard to break. My personal approach would be to make state schools free to make the overall field competitive for college costs. And yes, that would mean the state pays the schools directly instead of handing out money to students in the form of loans. It’s called an investment in our future, and it also would help with the mobility problems we have. At some point I’m sure it seemed like a terrible idea to form a public elementary school system for free, but we don’t think so now (or do we, Rupert?).

The biggest gripe, if you can get through the article, is that Obama’s plan will allow students to pay off their loans with at most 10% of their salaries after college, and that certain people can stop paying after 10 years instead of 20. If you read from the excerpt above, this is an outrage and those unfairly entitled people are characterized as government and nonprofit workers, but the truth is the exemptions include people who work as police officers, as healthcare workers, in law, or in the military as well.

The ending of the article, which again I suggest you don’t read, is this:

The consequences for our economy are no less tragic than for the individual borrowers. They are being driven away from the path down which their natural ambition and talent might have taken them. President Obama keeps talking about reducing income equality. So why does he keep paying young people not to pursue higher incomes?

All I can say is, what? I get that Rupert or whoever wrote this likes private industry, but the claim that by encouraging a bunch of people to go into super high paying private jobs we will reduce income inequality is just weird. Has that person not understood the relationship between inequality and CEO pay?

I say if you are so gung-ho about private high-paying jobs, then you also need to embrace rising inequality. Do it in the name of free-market capitalism or something, but please stay logical.

Interview with a high school principal on the math Common Core

In my third effort to understand the Common Core State Standards (CC) for math, I interviewed an old college friend Kiri Soares, who is the principal and co-founder of the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women. Here’s a transcript of the interview which took place earlier this month. My words are in italics below.

——

How are high school math teachers in New York City currently evaluated?

Teachers are now evaluated on 2 things:

- First, measures of teacher practice, which are based on observations, in turn based on some rubric. Right now it’s the Danielson Rubric. This is a qualitative measure. In fact it is essentially an old method with a new name.

- Second, measures of student learning, that is supposed to be “objective”. Overall it is worth 40% of the teacher’s score but it is separated into two 20% parts, where teachers choose the methodology of one part and principals choose the other. Some stuff is chosen for principals by the city. Any time there is a state test we have to choose it. In terms of the teachers’ choices, there are two ways to get evaluated: goals or growth. Goals are based on a given kid, and the teachers can guess they will get a certain slightly lower score or higher score for whatever reason. Otherwise, it’s a growth-based score. Teachers can also choose from an array of assessments (state tests, performance tests, and third party exams). They can also choose the cohort (their own kids/ the grade/the school). The city also chose performance tasks in some instances.

Can you give me a concrete example of what a teacher would choose as a goal?

At the beginning of year you give diagnostic tests to students in your subject. Based on what a given kid scored in September, you extrapolate a guess for their performance in the June test. So if a kid has a disrupted homelife you might guess lower. Teacher’s goal setting is based on these teachers’ guesses.

So in other words, this is really just a measurement of how well teachers guess?

Well they are given a baseline and teachers set goals relative to that, but yes. And they are expected to make those guesses in November, possibly well before homelife is disrupted. It definitely makes things more complicated. And things are pretty complicated. Let me say a bit more.

The first three weeks of school are all testing. We test math, social studies, science, and English in every grade, and overall it depending on teacher/principal selections it can take up to 6 weeks, although not in a given subject. Foreign language and gym teachers also getting measured, by the way, based on those other tests. These early tests are diagnostic tests.

Moreover, they are new types of tests, which are called performance-based assessments, and they are based on writing samples with prompts. They are theoretically better quality because they go deeper, the aren’t just bubble standardized tests, but of course they had no pre-existing baseline (like the state tests) and thus had to be administered as diagnostic. Even so, we are still trying to predict growth based on them, which is confusing since we don’t know how to predict performance on new tests. Also don’t even know how we can consistently grade such essay-based tests- despite “norming protocols”, which is yet another source of uncertainty.

How many weeks per year is there testing of students?

The last half of June is gone, a week in January, and 2-3 weeks in the high school in the beginning per subject. That’s a minimum of 5 weeks per subject per year, out of a total of 40 weeks. So one eighth of teacher time is spent administering tests. But if you think about it, for the teachers, it’s even more. They have to grade these tests too.

I’ve been studying the rhetoric around the CC. So far I’ve listened to Diane Ravitch stuff, and to Bill McCallum, the lead writer of the math CC. They have very different views. McCallum distinguished three things, which when they are separated like that, Ravitch doesn’t make sense.

Namely, he separates standards, curriculum, and testing. People complain about testing and say that CC standards make testing easier, and we already have too much testing, so CC is a bad thing. But McCallum makes this point: good standards also make good testing easier.

What do you think? Do teachers see those as three different things? Or is it a package deal, where all three things rolled into one in terms of how they’re presented?

It’s much easier to think of those three things as vertices of a triangle. We cannot make them completely isolated, because they are interrelated.

So, we cannot make the CC good without curriculum and assessment, since there’s a feedback loop. Similarly, we cannot have aligned curriculum without good standards and assessment, and we cannot have good tests without good standards and curriculum. The standards have existed forever. The common core is an attempt to create a set of nationwide standards. For example, without a coherent national curriculum it might seem OK to teach creationism in place of evolution in some states. Should that be OK?

CC is attempting to address this, in our global economy, but it hasn’t even approached science for clear political reasons. Math and English are the least political subjects so they started with those. This is a long time coming, and people often think CC refers to everything but so far it’s really only 40% of a kid’s day. Social studies CC standards are actually out right now, but they are very new.

Next, the massive machine of curriculum starts getting into play, as does the testing. I have CC standards and the CC-aligned test, but not curriculum.

Next, you’re throwing into the picture teacher evaluation aligned to CC tests. Teachers are freaking out now – they’re thinking, my curriculum hasn’t been CC-aligned for many years, what do I do now? By the way, importantly, none of the high school curriculum in NY State is actually CC-aligned now. DOE recommendations for the middle school happened last year, and DOE people will probably recommend this year for high school, since they went into talks with publication houses last year to negotiate CC curriculum materials.

The real problem is this: we’ve created these new standards to make things more difficult and more challenging without recognizing where kids are in the present moment. If I’m a former 5th grader, and the old standards were expecting something from me that I got used to, and it wasn’t very much, and now I’m in 6th grade, and there are all these raised expectations, and there’s no gap attention.

Bottomline, everybody is freaking out – teachers, students, and parents.

Last year was the first CC-aligned ELA and math tests. Everybody failed. They rolled out the test before any CC curriculum.

From the point of view of NYC teachers, this seems like a terrorizing regime, doesn’t it?

Yes, because the CC roll-out is rigidly tied to the tests, which are in turn rigidly tied to evaluations of teachers. So the teachers are worried they are automatically going to get a “failure” on that vector.

Another way of saying this is that, if teacher evaluations were taken out of the mix, we’d have a very different roll-out environment. But as it is, teachers are hugely anxious about the possibility that their kids might fail both the city and state tests, and that would give the teacher an automatic “failure” no matter how good their teacher observations are.

So if I’m a special ed teacher of a bunch of kids reading at 4th and 5th grade level even through they’re in 7th grade, I’m particularly worried with the introduction of the new and unknown CC-aligned tests.

So is that really what will happen? Will all these teachers get failing evaluation scores?

That’s the big question mark. I doubt it there will be massive failure though. I think given that the scores were so clustered in the middle/low muddle last year, they are going to add a curve and not allow so many students to fail.

So what you’re pointing out is that they can just redefine failure?

Exactly. It doesn’t actually make sense to fail everyone. Probably 75% of the kids got 2’s or 1’s out of a 4 point scale. What does failure mean when everyone fails? It just means the test was too hard, or that what the kids were being taught was not relevant to the test.

Let’s dig down to the the three topics. As far as you’ve heard from the teachers, what’s good and bad about CC?

My teachers are used to the CC. We’ve rolled out standards-based grading three years ago, so our math and ELA teachers were well adjusted, and our other subject teachers were familiar. The biggest change is what used to be 9th grade math is now expected of the 8th grade. And the biggest complaint I’ve heard is that it’s too much stuff – nobody can teach all that. But that’s always been true about every set of standards.

Did they get rid of anything?

Not sure, because I don’t know what the elementary level CC standards did. There was lots of shuffling in the middle school, and lots of emphasis on algebra and algebraic thinking. Maybe they moved data and stats to earlier grades.

So I believe that my teachers in particular were more prepared. In other schools, where teachers weren’t explicitly being asked to align themselves to standards, it was a huge shock. For them, it used to be solely about Regents, and also Regents exams are very predictable and consistent, so it was pretty smooth sailing.

Let’s move on to curriculum. You mentioned there is no CC-aligned curriculum in NY. I also heard NY state has recently come out against the CC, did you hear that?

Well what I heard is that they previously said they this year’s 9th graders (class of 2017) would be held accountable but now the class of 2022 will be. So they’ve shifted accountability to the future.

What does accountability mean in this context?

It means graduation requirements. You need to pass 5 Regents exams to graduate, and right now there are two versions of some of those exams: one CC-aligned, one old-school. The question is who has to pass the CC-aligned versions to graduate. Now the current 9th grade could take either the CC-aligned or “regular” Regents in math.

I’m going to ask my 9th grade students to take both so we can gather information, even though it means giving them 3 extra hours of tests. Most of my kids pass 2 Regents in 9th grade, 2 in 10th, and 3 in 11th, and then they’re supposed to be done. They only take those Regents tests in senior year that they didn’t pass earlier.

What are the good and bad things about testing?

What’s bad is how much time is lost, as we’ve already said. And also, it’s incredibly stressful. You and I went to school and we had one big college test that was stressful, namely the SAT. In terms of us finishing high school, that was it. For these kids it’s test, test, test, test. I don’t think it’s actually improved the quality of college students across the country. 20 years ago NY was the only one that had extra tests except California achievement tests, which I guess we sometimes took as well.

Another way to say it is that we did take some tests but it didn’t take 5 weeks.

And it wasn’t high stakes for the teacher!

Let’s go straight there: what are the good/bad things for the teachers with all these tests?

Well it definitely makes the teachers more accountable. Even teachers think this: there is a cadre of protected teachers in the city, and the principals didn’t want to take the time to get rid of them, so they’d excess them out of the schools, and they would stay in the system.

Now with testing it has become much more the principal’s responsibility to get rid of bad teachers. The number of floating teachers is going down.

How did they get rid of the floaters?

A lot of different ways. They made them go into the schools, take interviews, they made their quality of life not great, and a lot if them left or retired or found jobs. Principals took up the mantle as well, and they started to do due diligence.

Sounds like the incentive system for over-worked principals was wrong.

Yes, although the reason it became easier for the principals is because now we have data. So if you’re coming in as ineffective and I also have attendance data and observation data, I can add my observational data (subjective albeit rubric based) and do something.

If I may be more skeptical, it sounds like this data gathering was used as a weapon against teachers. There were probably lots of good teachers that have bad numbers attached to them that could get fired if someone wanted them to be fired.

Correct, except those good teachers generally have principals who protect them.

You could give everyone a bad number and then fire the people you want, right?

Correct.

Is that the goal?

Under Bloomberg it was.

Is there anything else you want to mention?

I think testing needs to be dialed down but not disappear. Education is a bi-polar pendulum and it never stops in the middle. We’re on an extreme but let’s not get rid of everything. There is a place for testing.

Let’s get our CC standards, curriculum, and testing reasonable and college-aligned and let’s keep it reasonable. Let’s do it with standards across states and let’s make sure it makes sense.

Also, there are some new tests coming out, called PARCC assessments, that are adaptive tests aligned to the CC. They are supposed to replace Regents down the line and be national.

Here’s what bothers me about that. It’s even harder to investigate the experience of the student with adaptive tests.

I’m not sure there’s enough technology to actually do this anyway very soon. For example, we were given $10,000 for 500 student. That’s not going to go far unless it takes 2 weeks to administer the test. But we are investing in our technology this year. For example, I’m looking forward to buying textbooks and get my updates pushed instead of having to buy new books every year.

Last question. They are redoing the SAT because rich kids are doing so much better. Are they just trying to get in on the test prep game? Because, here’s the thing, there’s no test that can’t be gamed that’s also easy to grade. It’s gotta depend on the letters and grades. We keep trying to shortcut that.

Listen, this is what I tell the kids. What’s going to matter to you is the letter of recommendation, so don’t be an jerk to your fellow students or to the teachers. Next, are you going to be able to meet the minimum requirements? That’s what the SAT is good for. It defines a lower bound.

Is it a good lower bound though?

Well, I define the lower bound as 1000 in total. My kids can target that. It’s a reasonable low bar.

To what extent do your students – mostly inner-city, black girls interested in math and science – suffer under the wholly gamed SAT system?

It serves to give them a point of self-reference with the rest of the country. You have to understand, they, like most kids in the nation, don’t have a conception of themselves outside of their own experience. The SAT serves that purpose. My kids, like many others, have the dream of Ivy League minus the understanding of where they actually stand.

So you’re saying their estimates of their chances are too high?

Yes, oftentimes. They are the big fish in a well-defined pond. At the very least, The SAT helps give them perspective.

Thanks so much for your time Kiri.

The Lede Program: An Introduction to Data Practices

It’s been tough to blog what with jetlag and a new job, and continuing digestive issues stemming from my recent trip, which has prevented me from drinking coffee. It really isn’t until something like this happens that I realize how very much I depend on caffeine for my early morning blogging. I really cherish that addiction like a child. Don’t tell my other kids.

Speaking of my new job, the website for the Lede Program: An Introduction to Data Practices is now live, as is the application. Very cool.

We’re holding information sessions about the program next Monday and Thursday at 1:00pm at the Stabile Center, on the first floor of the Journalism School which is in Pulitzer Hall. Please join us and please spread the news.

We are also still looking for teachers for the program, and we’ve fixed the summer classes, which will be:

- Basic computing,

- Data and databases,

- Algorithms, and

- The platform

I’m really excited about all of these but probably most about the last one, where we will investigate biases inherent in data, systems, and platforms and how they affect our understanding of objective truth. Please tell me if you know someone who might be great for teaching any of these, they are intense, seven week classes (either from end of may to mid-July or from mid-July to the end of August) which will meet 3 hours twice a week each.

Billionaire money and academic freedom

If you haven’t seen this recent New York Times article by William Broad, entitled Billionaires With Big Ideas Are Privatizing American Science, then go take a look. It generalizes to all of scientific research my recent post entitled Billionaire Money in Mathematics.

My favorite part of Broad’s article is the caption of the video at the top, which sums it up nicely:

Funding the Future: As government financing of basic science research has plunged, private donors have filled the void, raising questions about the future of research for the public good.

In his article Broad makes a bunch of great points.

First, the fact that rich people generally ask for research into topics they care about (“personal setting of priorities”) to the detriment of basic research. They want flashy stuff, bang for their buck.

Second, academics interested in getting funding from these rich people have to learn to market themselves. From the article:

The availability of so much well-financed ambition has created a new kind of dating game. In what is becoming a common narrative, researchers like to describe how they begged the federal science establishment for funds, were brushed aside and turned instead to the welcoming arms of philanthropists. To help scientists bond quickly with potential benefactors, a cottage industry has emerged, offering workshops, personal coaching, role-playing exercises and the production of video appeals.

If you think about it, the two issues above are kind of wrapped up together. Flashy academic content goes hand in hand with flashy marketing. Let’s say goodbye to the true nerd who doesn’t button up their cardigan correctly. And I don’t know about you but I like those nerds. My mom is one of them.

This morning I thought of another way to express this issue, from the point of view of the individual scientist or mathematician, that might have profound resonance where the above just sounds annoying.

Namely, I believe that academic freedom itself is at stake. Let me explain.

I’m the last person who would defend our current tenure system. It’s awful for women, especially those who want kids, and it often breeds a kind of arrogant laziness post-tenure. Even so, there are good things about it, and one of them is academic freedom.

And although theoretically you can have academic freedom without tenure, it is certainly easier with it (example from this piece: “In Oklahoma, a number of state legislators attempted to have Anita Hill fired from her university position because of her testimony before the U.S. Senate. If not for tenure, professors could be attacked every time there’s a change in the wind.”).

But as we’ve seen recently, tenure-track positions are quickly declining in number, even as the number of teaching positions is growing. This is the academic analog of how we’ve seen job growth in the US but it’s majority shitty jobs. And as I’ve predicted already, this trend is surely going to continue as we scale education through MOOCs.

The dwindling tenured positions means there are increasing number of people trying to do research dependent upon outside grants and funding, and without the safety net of tenure. These people often lose their jobs when their funding flags, as we’ve recently seen at Columbia.

Now let’s put these two trends together. We’ve got fewer and fewer tenure jobs, which are precariously dependent on outside funding, and we’ve got rich people funding their own tastes and proclivities.

Where does academic freedom shake out in that picture? I’m going to say nowhere.

Let’s not replace the SAT with a big data approach

The big news about the SAT is that the College Boards, which makes the SAT, has admitted there is a problem, which is widespread test-prep and gaming. As I talked about in this post, the SAT mainly serves to sort people by income.

It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone when a weak proxy gets gamed. Yesterday I discussed this very thing in the context of Google’s PageRank algorithm, and today it’s student learning aptitude. The question is, what do we do next?

Rick Bookstaber wrote an interesting post yesterday (hat tip Marcos Carreira) with an idea to address the SAT problem with the same approach that I’m guessing Google is addressing the PageRank problem, namely by abandoning the poor proxy and getting a deeper, more involved one. Here’s Bookstaber’s suggestion:

You would think that in the emerging world of big data, where Amazon has gone from recommending books to predicting what your next purchase will be, we should be able to find ways to predict how well a student will do in college, and more than that, predict the colleges where he will thrive and reach his potential. Colleges have a rich database at their disposal: high school transcripts, socio-economic data such as household income and family educational background, recommendations and the extra-curricular activities of every applicant, and data on performance ex post for those who have attended. For many universities, this is a database that encompasses hundreds of thousands of students.

There are differences from one high school to the next, and the sample a college has from any one high school might be sparse, but high schools and school districts can augment the data with further detail, so that the database can extend beyond those who have applied. And the data available to the colleges can be expanded by orders of magnitude if students agree to share their admission data and their college performance on an anonymized basis. There already are common applications forms used by many schools, so as far as admission data goes, this requires little more than adding an agreement in the college applications to share data; the sort of agreement we already make with Facebook or Google.

The end result, achievable in a few years, is a vast database of high school performance, drilling down to the specific high school, coupled with the colleges where each student applied, was accepted and attended, along with subsequent college performance. Of course, the nature of big data is that it is data, so students are still converted into numerical representations. But these will cover many dimensions, and those dimensions will better reflect what the students actually do. Each college can approach and analyze the data differently to focus on what they care about. It is the end of the SAT version of standardization. Colleges can still follow up with interviews, campus tours, and reviews of musical performances, articles, videos of sports, and the like. But they will have a much better filter in place as they do so.

Two things about this. First, I believe this is largely already happening. I’m not an expert on the usage of student data at colleges and universities, but the peek I’ve had into this industry tells me that the analytics are highly advanced (please add related comments and links if you have them!). And they have more to do with admissions and college aid – and possibly future alumni giving – than any definition of academic success. So I think Bookstaber is being a bit naive and idealistic if he thinks colleges will use this information for good. They already have it and they’re not.

Secondly, I want to think a little bit harder about when the “big, deeper data” approach makes sense. I think it does for teachers to some extent, as I talked about yesterday, because after all it’s part of a job to get evaluated. For that matter I expect this kind of thing to be part of most jobs soon (but it will be interesting to see when and where it stops – I’m pretty sure Bloomberg will never evaluate himself quantitatively).

I don’t think it makes sense to evaluate children in the same way, though. After all, we’re basically talking about pre-consensual surveillance, not to mention the collection and mining of information far beyond the control of the individual child. And we’re proposing to mine demographic and behavioral data to predict future success. This is potentially much more invasive than just one crappy SAT test. Childhood is a time which we should try to do our best to protect, not quantify.

Also, the suggestion that this is less threatening because “the data is anonymized” is misleading. Stripping out names in historical data doesn’t change or obscure the difference between coming from a rich high school or a poor one. In the end you will be judged by how “others like you” performed, and in this regime the system gets off the hook but individuals are held accountable. If you think about it, it’s exactly the opposite of the American dream.

I don’t want to be naive. I know colleges will do what they can to learn about their students and to choose students to make themselves look good, at least as long as the US News & World Reports exists. I’d like to make it a bit harder for them to do so.