Archive

Evil finance should contribute to open source

This is a guest post from an friend who wishes to remain anonymous.

I’ve been thinking lately that a great way for “evil finance” to partially atone for its sins is to pay a lot of money to improve open source libraries like numpy/scipy/R. They could appeal to the whole “this helps cancer research” theme, which I honestly believe is true to some extent. For example, if BigData programs ran 10% faster because of various improvements, and you think there’s any value to current medical research, and the cancer researchers use the tools, then that’s great and it’s also great PR.

To some extent I think places like Google get some good publicity here (I personally think of them as contributing to open source, not sure how true it really is), and it seems like Goldman and others could and should do this as well — some sliver of their rent collection goes into making everybody’s analysis run faster and some of that leads to really important research results.

Personally I think it’s true even now; Intel has been working for years on faster chips, partially to help price crazy derivatives but it indirectly makes everybody’s iPhone a little cheaper. Contributing directly to open source seems like a direct way to improve the world and somewhat honestly claim credit, while getting huge benefit.

And it simultaneously has nice capitalist and socialist components, so who wouldn’t be happy?

There are actual problems banks care about solving faster, a lot of which uses pretty general purpose open source libraries, and then there are the maintainers of open source libraries doing this nice altruistic thing but I’m sure could do even better if only they didn’t have a “day job” or whatever.

And if the banks don’t want to give away too much information, they can just make sure to emphasise the general nature of whatever they help fund.

Privacy concerns

The theme of the day yesterday here at the IMA in Minnesota was privacy. There was a talk on privacy and information as well as a discussion later in the afternoon with the participants.

The talk, given by Vitaly Shmatikov, was pretty bad news for anyone who is still hoping to keep private info out of the hands of random internet trolls. Vitaly explained how de-identifying data is a relatively hopeless task, at least if you want to retain useful information in the data, because of the sparseness of most human data.

An example he gave was that the average Netflix user rates 200 films but can be identified on just 4 ratings, at least if you include timestamps. He also pointed out that, even though Netflix doesn’t directly expose its users’ movie preferences, you can infer quite a bit just by looking at how recommendations by Netflix (of the form “people who like House also like Friends”) evolve over time.

And never mind Facebook or other social media, which he explained people can crawl directly and infer the graph structure of; even without any labels for the nodes, which refer to people, one can infer an outrageous amount if you have a separate, labeled graph with overlap on the first.

Conclusion: when people think they’ve de-identified data they haven’t, because other people can collect lots of such data sets, and on top of that some small amount of partial private, identified information about individual users, and piece it together to get creep amounts of stuff.

An example I heard later that day is that someone has figured out how to take pictures of people and give them a large part of their social security number.

The conversation later that day focused more on how companies should protect their client data (through a de-indentifying algorithm), and how for the most part they do absolutely nothing right now. This is perhaps because the problem “isn’t solved” so people don’t see the reason to do something that’s not a perfect solution even though some basic procedures would make it a lot harder. My suspicion is that if they do nothing they are betting they’re more protected from litigation than if they do something that turns out to be too weak. Call me a skeptic but it’s always about litigation.

My contribution to both the talk and the conversation was this: why don’t we stop worrying about data getting out, since it’s kind of a done deal (no data ever disappears and our algorithms are only getting better). Why don’t we assume that all historical information about everyone is out there.

So, besides how to get into my bank account (I haven’t sorted that one out yet, maybe I’ll just have to carry all my money in physical form) I’ll assume everyone knows everything about me, including my DNA.

Then the question becomes, how can we live in a reasonable world given that? How can we, for example, prevent private insurance companies from looking up someone’s DNA or HIV status in order to deny coverage?

This is not an idle concern. As someone pointed out yesterday, 15 years ago nobody would have believed someone who described how much information about the average Facebook user is available now. We have no idea what it will look like in another 15 years.

Great news for NYC dataphiles: Microsoft Research is coming to NYC

This is a guest post by Chris Wiggins.

I was happy to see the news this morning that Microsoft is opening a new research lab in NYC, with 15 of the former members of the Yahoo R+D NYC lab as its founding members.

The Yahoo group is one of the most multidisciplinary research teams I’ve ever seen, with great research collaborations among physicists, machine learning experts, applied mathematicians, and social science, all learning about human behavior by analyzing web-scale datasets.

They have also managed to show how a research lab can make great contribution both to the local and international research communities in their field. For example, Jake Hofman at Yahoo has been teaching a great ‘Data Driven Modeling’ class at Columbia for years; John Langford has been a co-organizer of the New York Academy of Sciences’ one-day Machine Learning Symposium since it was founded (while also organizing international machine learning conferences, running a great machine learning blog, etc…)

Some particularly exciting aspects from the announcement include:

- Mathematical physicist Jennifer Chayes seems to be implying she’ll be spending at least part of her time here in NYC rather than her current home of MSR-Cambridge

- Multiple people in the story said they’re interested in ties with startups and universities, which should be good for the intellectual landscape of NYC dataphiles.

Congrats to all and to NYC!

Occupy Data!

My friend Suresh and I are thinking of starting a new working group for Occupy Wall Street, a kind of data science quant group.

One of his ideas: creating a value-added model for police in New York, just to demonstrate how dumb whole idea is. How many arrests above expected did each cop perform? [Related: you will be arrested if you bring a sharpie to the Bank of America Shareholder’s meeting in Charlotte!]

It’s going to be tough considering the fact that the crime reports are not publicly available. I guess we’d have to do it using Question, Stop, and Frisk data somehow. Maybe it could actually be useful and could highlight the most dangerous places to walk in the city.

Or I was thinking we could create a value-added model for campaign contributions, something like trying to measure how much influence you actually buy with your money (beyond the expected). It answers the age-old question, which super-PACs give you the best bang for your buck?

Please tell me if you can think of other good modeling ideas! Feel free to include non-ironic modeling ideas.

NYC Data Hackathon

This is a guest post by Chris Wiggins.

Last night I was a judge for the Data Viz Competition at the NYC Data Hackathon, part of the world’s first global data hackathon. Along with my fellow judges Cathy O’Neil and Jake Porway, we gave an award to the team that best found a nontrivial insight from the data provided for the competition and managed to render that insight visually.

Unlike a hackNY hackathon, where the energy is pretty high and the crowd much younger (hackNY hackathons are for full time students only; this crowd all were out of school — in fact at least one person was a professor), here everyone was really heads down. There was plenty of conversation and smiles but people were working quite hard, even 12 hours into the hackathon.

I noticed two things that were unusual about the participants, both of which I think speak well of the state of `data science’ in NYC:

* I’ve never been in a room with such a health mix of Wall Street quants and startup data scientists. Many of the teams included a mix of people from different sectors working together. The winning team was typical in this way: 1 person from Wall Street; 1 freelancer; and 1 data scientist from an established NYC startup.

* I met multiple people visiting from the Bay Area contemplating moving to NYC. In 2004-2007 many of my students from Columbia moved out to SF under the historical notion that that was `the place’ where they could work at a small company that would demand their technical mastery and give them sufficient autonomy to see their work come to light under their own direction. I was glad to meet people from the Bay Area who were sufficiently impressed with NYC’s data scene to consider moving here. Of course I told them it was exactly the right thing to do

and I looked forward to seeing them again soon once they’d become naturalized citizens of NYC.

Huge thanks to Shivon Zils and Matt Truck for hosting us in such a nice location, to Jeremy Howard for his suggestion a few weeks ago to throw the event, and to Max Shron for encouraging everyone to include a visualization prize as part of this event.

Online learning promotes passivity

Up til I took Andrew Ng’s online machine learning class last semester, I had two worries about the concept of online learning. First, I worried that the inability to ask questions would be a major problem. Second, I worried about the possibility of building up material. I could imagine learning a given thing online but the ability to sustain and build material over an entire semester seemed kind of unrealistic.

On the second point, I think I’m convinced. Andrew definitely taught us a real semester’s worth of stuff, and he built up a body of knowledge very well. I now communicate with my colleagues at work using the language he taught us, which is very cool.

On the first point about asking questions, however, I am even more convinced there’s a crucial problem.

I want to differentiate between two different kinds of questions to make my point. First, there’s the “I’m confused” type of question, where someone literally doesn’t get the point of something or doesn’t understand the notation or a step in an explanation.

One can imagine tackling this kind of question in various ways. For example, one can strive to be a really good teacher, which Andrew certainly is, or to explain things at a high level but shove the details into black boxes, which Andrew did quite a bit (somewhat to my disappointment, especially when linear algebra was involved). If neither of those two things is sufficient, and the class is really important and/or really common, one can imagine teaching a computer to anticipate confusion and to ask questions along the way to make sure the students are following, and to go back and explain things in a different way if not.

In other words, the first kind of “clarifying questions” can probably be dealt with by the online learning community over time.

But there’s a second kind, namely the kind of question where someone is not confused but rather asks a question for one of the following reasons:

- they want to know how a certain idea relates to something else they know about,

- they want to generalize something the teacher said,

- they want to argue against an approach or for another approach,

- they see a mistake, or

- they see an easier way to do something.

Almost by definition, the above kinds of questions aren’t anticipated by the teacher, but the fact that they are asked almost always improves the class, certainly for the student in question but also for the other students and the teacher.

For example, one semester I taught three sections of 18.03 (exhausting! and I was pregnant!), which is a calculus class at M.I.T., and I remember thinking that in every single class one of the students made a remark or asked a question that I learned something from. It got to the point that, the third time through the same material, I’d be waiting for someone to explain how I should be teaching it. I loved that the students there are so smart but also so engaged in learning.

And that’s what I’m worried about- the engagement. When you embark on an online class, the best you can hope for is that you learn something and that you don’t get hopelessly confused. And that’s cool, that you can learn something, for free, online. But what you can’t do is what I’m worried about, and that’s to get instant feedback and discussion about some idea you had in the categories above.

I’m definitely one of those people who asks questions of the second type, and although I may sometimes annoy my fellow students, I really feel like the active engagement I pursue by coming up with all sorts of crazy comments and ideas and questions is what made me capable of doing original and creative things. For me, the most important part of my education was that training whereby I got to ask questions in class and got smart teachers who liked me to do so and would talk to me about my ideas.

How can that possibly happen with online learning? I’m afraid it can’t, and I’m afraid we will be training people to receive information rather than to engage in creation.

I imagine that in 200 years, almost everyone will be taught online, hooked into the machine and pumped up with knowledge. It will be only the elites who will have access to real live people to teach them in person, where they will be taught not only the material but also how to argue against a point of view and to propose an alternate approach.

Calling all data scientists! The first ever global data science hackathon

Hey I’m helping organize a NYC data hackathon at Bloomberg Ventures to take place April 28th – 29th, from 8am Saturday to 8am Sunday. I’m looking for outrageously nerdy people to come help. There will be some prizes.

Read the official blurb below carefully and if you’re in, sign up for the event by registering here.

Update: they’ve decided on prizes.

See you there!

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Are you a smart data scientist? Participate in this hackful event. 24 hours of non-stop, fun data science competition. The first ever global, simultaneous data science hackathon!

In connection with Big Data Week, we’re helping organize a global data science hackathon that will simultaneously take place in various locations around the world (including London, Sydney, and San Francisco). We will host the NYC event at the Bloomberg Ventures office in the West Village.

The aim of the hackathon is to promote data science and show the world what is possible today combining data science with open source, Hadoop, machine learning, and data mining tools.

Data scientists, data geeks, and hackers will self organize around teams of 3-5 members. Contestants will be presented with a ‘big data’ set (hosted on the Kaggle platform). In order to win prizes, the teams will have to use data science tools and develop an analytical model that will solve a specific data science problem specified by the judging tech panel. The contestants will have to report their achievements at specific milestones, and a leader board will be published online at each milestone.

The contestants will spend 24 hours in Bloomberg Ventures’ office space where food, drinks, workspaces, and resting areas will be provided. Teams will compete for both local and global titles and prizes.

The Hackathon runs for 24 hours starting on April 28th at 8am (early start to allow for the event to happen simultaneously in multiple time zones around the world).

If you have questions, please email shivon.zilis@bloombergventures.com

PLEASE READ CAREFULLY:

1. This is a technical competition, not a networking event or an opportunity to learn more about big data techniques and technologies. We have limited space, so we unfortunately need to be strict about who gets to compete. If you’re an entrepreneur looking to recruit, we’re excited to have you as a member of this community, but this specific event is not the right venue, please come our regular Data Business meetups instead! 🙂

2. You should have Mad Skillz at at least one of the following:

- Data grappling and/or cleaning,

- Data modeling and forecasting,

- Data visualization,

- Spontaneous micro- and macro-economic theory creation

3. You should know one or more of the following languages:

- R

- python

- Matlab

- Some statistical package like SPSS or SAS

4. You should bring your hardcore laptop to the event, since we will have on the order of 10 gigs of data to play with.

Continuously forecasting

So I’ve been thinking about how to forecast a continuous event. In other words, I don’t want to forecast a “yes” or a “no”, which is something you might do in face recognition using logistic regression, and I don’t want to split the samples into multiple but finite bins, which is something you may want to do in handwriting recognition using neural networks or decision trees or recommender systems.

I want essentially a score, in fact an expected value of something, where the answers could range over the real numbers (but will probably just range over a pretty small subset but I don’t know exactly what smallish subset).

What happens when you look around is that you realize machine learning algorithms pretty much all do the former, except for various types of regression (adding weights, adding prior, nonlinear terms), which I already know about from my finance quant days. So I’m using various types of regression, but it would be fun to also use a new kind of machine learning algorithm to compare the two. But it looks like there’s nothing out there to compare with.

It’s something I hadn’t noticed til now, and I’d love to be wrong about it, so tell me if I’m wrong.

More creepy models

I’ve been having fun collecting creepy data-driven models for your enjoyment. My first installment was here, with additional models added by my dear commenters. I’ve got three doozies to add today.

- Girls Around Me. This is a way to find out if you know any girls in your immediate vicinity, which is perfect for my stalker friends, using Foursquare data. My favorite part is that the title of this article about it actually uses the word “creepy”.

- Zestcash is a cash lending, payday-like service that data mines their customers, with a stated APR of up to 350%. On of my favorite misleading quotes in this article about the model: “Better accuracy should translate into lower interest rates for consumers.” Ummmm… yeah for some of them. And I guess the idea goes, those other losers deserve what they get because they’re already poor?

- The creepiest of all by far (because it is so painfully scalable and I could imagine it being everywhere in 2 years) is this one which proposes to embody the “best practices” of medicine into a data science model. Look, we desperately need a good model in health and medicine to do some of the leg-work for us, namely come up with a list of reasonable treatments that your doctor can take a look at and discuss with you. But we definitely don’t need a model which comes up with that list and then decides for you and your doctor which one you should undergo. Decisions like that, which often come down to things like how we care about quality of life, cannot and should not be turned into an algorithm.

By the way, just to balance the creepy models a bit, I also wanted to mention a few cool ideas:

- What about having a Reckoner General, like a surgeon general? That person could answer basic questions to explain how models are being used and to head off creepy models. Proposed by my pal Jordan Ellenberg.

- What about having an F.D.A.-like regulator for financial products? They would be in charge of testing the social utility of a proposed instrument class before it went to market. Can we do the same for data-driven models? Can the regulator be kick-ass and reasonably funded?

- What about having a creep model auditing board that brings together a bunch of nerds from technology and ethics and looks through the new models and formally reprimands creepiness, using the power of social pressure to fend it off? They could publicize a list of creeps who made these models to call people out and shame them. That really doesn’t happen enough, it’s like the modelers are invisible.

- How about a law that, if you add a cookie to your digital signature that says, “don’t track me for reals”, then if you find someone tracking you, as in saving and selling your information, you can sue for $100K in damages and win?

What’s Mahout?

Mahout is an Apache project, which means it’s open source software.

Specifically, Mahout consists of machine learning algorithms that are (typically) map-reducable, and implemented in a map-reduce framework (Hadoop), which means you can either use them on the cloud or on your own personal distributed cluster of machines.

So in other words, if you have a massive amount of data up in the cloud, and you want to apply some machine-learning algorithm to your data, then you may want to consider using Mahout.

Yesterday I learned about a recommendation algorithm and how to map-reduce it (i.e. make it as fast as I want by distributing the work on many machines) by reading Mahout in Action. And the cool thing is that it’s already implemented and optimized, which is good because there’s a big difference between thinking I know how to map-reduce something and making it fast.

So if Netflix ever fails, but their data is miraculously left intact, they can send me and a few other nerds in as a kind of data scientist rescue squad and we can help figure out how to reassemble the recommendations of new movies based on what people have already watched and rated.

If that ever really happens, I hope we’d get t-shirts that say “data scientist rescue squad” on the back.

Update: a mahout is also someone who drives an elephant. And Mahout drives Hadoop, which is the name of Doug Cutting‘s son’s toy elephant. Doug is the guy who started Hadoop at Yahoo! but now he’s at Cloudera.

Random stuff, some good some bad

- In case you didn’t hear, Obama didn’t nominate Larry Summers to head the World Bank. This goes in the category of good news in the sense that expectations were so low that this seems like a close call. But I guess it’s bad news that expectations have gotten so low.

- Am I the only person who always thinks of tapioca when I hear the word “mediocre”?

- There are lots of actions going on in Occupy Wall Street, part of the Spring Resistance. It’s going to be an exciting May Day, what are you plans?

- Did you hear that New Jersey was somehow calculated to be the country’s least corrupt state? This Bloomberg article convincingly blows away the methodology that came to that conclusion. In particular, as part of the methodology they asked questions about levels of transparency and other things to people working in New Jersey League of Municipalities (NJLM). A bit of googling brings up this article from nj.com, exposing that NJLM clearly have incentives to want the state government to look good: it consists of “… more than 13,000 elected and appointed municipal officials — including 560 mayors — as members… its 17 employees are members of the Public Employees’ Retirement System, and 16 percent of its budget comes from taxpayer funds in the form of dues from each municipality.” Guess what NJLM said? That New Jersey is wonderfully transparent. And guess what else? The resulting report is front and center on their webpage. By the way, NJLM was sued by Fair Share Housing to open up their documents to the public, and they lost. So they have a thing about transparency. And just to be clear, the questions for deciding whether a given state is corrupt could have been along the lines whether the accounting methods for the state pension funds are available on the web and searchable on the state government’s website.

- If you know of examples of so-called quantitative models that are fundamentally flawed and/or politically motivated like this, please tell me about them! I enjoy tearing apart such models.

- The Dallas Fed has called for an end to too-big-to-fail banks. Mmmhmmm. I love it when someone uses the phrase, “Aspiring politicians in this audience do not have to be part of the Occupy Wall Street movement, or be advocates for the Tea Party, to recognize that government-assisted bailouts of reckless financial institutions are sociologically and politically offensive”.

- Volcker says more reforms are needed in finance and government. Can we start listening to this guy now that we broke up with Summers? Please?

The Market Price of Privacy

I recently got annoyed by this New York Times “Bitz” blog, written by Somini Sengupta, about paying for privacy. It correctly pointed out that we get services on the web that seem `free’ to us, but there is an actual price which we pay, namely we are targets of ads and are sometimes forced to hand over personal information. Moreover, when we use `free’ services such as sending invitations to a party, we are subjecting all of our friends to advertising as well. From the post:

It was a perfect microcosm of the bargain we make with the Web every day. Send me ads based on what you know about me (bachelorette party vs. child’s birthday party) or take my money to keep my screen free of ads. That bargain was the topic of a fascinating study that asked how much we are willing to pay to keep our personal data to ourselves.

The article then explained the recent study. Namely, it seems that Germans aren’t willing to pay an extra 50 Euro cents for movie tickets to avoid giving out their cells numbers, but they do claim to care about personal information gathering. If there was no price difference they wanted the less intrusive version. The author seemed to think this is a paradox.

What? That’s kind of like me saying, I like better quality chocolate, but I’m not willing to pay $400 per serving for better chocolate, and then you say I’m a hypocrite and must not like chocolate.

The fact is, it’s all about the price. It’s always all about the price. There is no way, absolutely no way, that a cell phone number, reluctantly given in a situation such as for buying movie tickets, is worth 50 Euro cents to the company collecting the number. Therefore there’s no way you should have to pay that much to avoid giving it.

Here’s another example the blog gave, when explaining sending out a dozen web-based invitations to a party:

Faced with the choice of paying an extra $10 to keep my invitation advertisement-free, I dithered. It would be easy and inexpensive, I thought, to follow Wikipedia’s lead on this (the online encyclopedia is stubbornly ad-free). But then I thought about that little risk that accompanies the ease of digital consumption: Would my credit card information be safe with this online greeting card company? The worrywart in me won out. I did not pay the extra $10. I chose to lob advertisements at my friends.

I’m in internet advertising, and I can tell you right now that a very generous estimate of how much each opportunity to advertise for your guests on an invitation, and presumably the original email and anything you’d click on in receiving the invitation, could be worth up to 10 cents, max. That is to say, the offer of keeping your invitations advertisement free for $10 is an approximately 10x markup, and you’d be a fool to pay that much for something worth so little on the open market.

So here’s what drives me crazy. It’s not that people aren’t willing to pay for privacy. They are. They’re just not willing to overpay by an outrageous amount for privacy. Far from seeming like a paradox, this seems like good intuition for a market price. If there is a web-based company that offers to send out advertisement-free invitations for a dime per guest, I think about my friends and I say, yeah they’re worth a dime each (but actually I just send them an email to come to my party).

Consumers don’t (yet) actually have access to the market price of privacy- that market is dominated for now by large-scale institutional collectors of information, which is why we’re seeing outrageous markups like these for individuals. It will be interesting to see how that changes.

Supply side economics and human nature

The original goal of my blog, or at least one of them, was to expose the inner workings of modeling, so that more people could use these powerful techniques for stuff other than trying to skim money off of pension funds.

Sometimes models are really complicated and seem almost like magic, so part of my blog is devoted to demystifying modeling, and explaining the underlying methods and reasoning. Even simple sounding models, like seasonal adjustments (see my posts here and here), can involve modeling choices that are tricky and can lead you to be mightily confused.

On the other hand, sometimes there are “models” which are actually fraudulent, in that they are not based on data or mathematics or statistics at all- they are pure politics. Supply-side economics is a good example of this.

First, the alleged model. Then, why I think it’s actually a poser model. Then, why I think it’s still alive. Finally, conclusions.

Supply-side economics

At its most basic level, supply-side economics is the theory that raising taxes will stifle growth so much that the tax hike will be counterproductive. To be fair, the underlying theory just says that, once tax rates are sufficiently high, the previous sentence is valid. But the people who actually refer to supply-side economics always assume we are already well withing this range.

To phrase it another way, the argument is that tax cuts will “pay for themselves” by freeing up money to go towards growth rather than the government. That extra growth will then result in more taxes taken in, albeit at the lower rate.

Now, as we’ve states this above, it does sound like a model. In other words, if we could model our tax system and economy well enough, and then change the tax rate by epsilon, we could see whether growth grows sufficiently that our tax revenue, i.e. the amount of money that the government takes in with the lower tax rate, is actually bigger. The problem is, both our tax system and economy are way too complicated to directly model.

Let’s talk abstractly, if it’s the best we can do. If tax rates (which are assumed flat, so not progressive) are at either 0% or at 100%, the government isn’t collecting any money: none at 0% because in that case the government isn’t even trying to collect money, and none at 100% because at that level nobody would bother to work (which is an assumption in itself).

On the other hand, at 35% we clearly do collect some money. Therefore, assuming continuity, there’s some point between 0% and 100% which maximizes revenue (note the reference to the Extreme Value Theorem from calculus). Let’s call this the critical point. This is illustrated using something called the Laffer Curve. Now assume we’re above that critical point. Then raising taxes actually decreases revenue, or conversely lowering taxes pays for itself.

Supply-side economics is not a model

Let me introduce some problems with this theory:

- We don’t have flat taxes. In fact our taxes are progressive. This is really important and the theory simply doesn’t address it.

- The idea of a 100% tax rate is mathematically flawed, because it may well be a singular point. We should instead consider how people would behave as we approach 100% taxation from below. For example, I can imagine that at 90% taxation, people would be perfectly happy to work hard, especially if their healthcare, education, housing, and food were taken care of for them. Same for 99% taxation. I do think people want some power over their money, so it makes more sense to think about taxation approaching 100% than it does to imagine it at 100%. Another way of saying this is that the critical point may be at 97%, and the just plummets after that or does something crazy.

- It of course does depend on what the government is doing with all that money. If it’s just a series of Congressional bickering sessions, then nobody wants to pay for that.

- The real problem is that we just don’t know where the critical point is, and it is essentially impossible to figure out given our progressive tax system and the enormous number of tax loopholes that exist and all the idiosyncratic economic noise going on everywhere all the time.

- The best we can do is try to figure out whether a given tax increase or decrease had a positive revenue effect or not on different subpopulations that for some reason are or are not left out, so what’s called a natural experiment. This New York Time article written by Christina Romer explains one such study and the conclusion is that raising taxes also raises revenue. From the article:

Where does this leave us? I can’t say marginal rates don’t matter at all. They have some impact on reported income, and it’s possible they have other effects through subtle channels not captured in the studies I’ve described. But the strong conclusion from available evidence is that their effects are small. This means policy makers should spend a lot less time worrying about the incentive effects of marginal rates and a lot more worrying about other tax issues.

- There are plenty of ways that natural experiments are biased (namely the subpopulations that are left out of tax hikes are always chosen very carefully by politicians), so I wouldn’t necessarily take these studies at face value either.

Supply-side economics is a political model, not a statistical model

In this recent Economix blog in the New York Times, Bruce Bartlett explains the history of supply-side economics and the real reason this flawed model is so popular. He explains an old essay of Jude Wanniski’s entitled “Taxes and a Two-Santa Theory,” which if you read it is an political, idiosyncratic argument for supply-side economics. Bartlett describes Wanniski’s essay thus:

Instead of worrying about the deficit, he (Wanniski) said, Republicans should just cut taxes and push for faster growth, which would make the debt more bearable.

Mr. Kristol, who was very well connected to Republican leaders, quickly saw the political virtue in Mr. Wanniski’s theory. In the introduction to his 1995 book, “Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea,” Mr. Kristol explained how it affected his thinking:

I was not certain of its economic merits but quickly saw its political possibilities. To refocus Republican conservative thought on the economics of growth rather than simply on the economics of stability seemed to me very promising. Republican economics was then in truth a dismal science, explaining to the populace, parent-like, why the good things in life that they wanted were all too expensive.

The Kristol quoted above is Irving Kristol, the “godfather of neoconservatism”. So he went on record saying that whatever the statistical merits of the supply-side theory were, it was awesome politics.

Conclusions

First, my conclusion is that Christina Romer should be ahead of Larry Summers on the short list to be the head of the World Bank. I mean, at least she’s trying to use actual data to figure this stuff out.

Second, I think there’s some lessons here to be learned about how people think and how they want to be convinced things work. When confronted with something they don’t like, like taxes, they are happy to believe a secondary effect, namely stifled growth, actually dominates a primary effect, namely tax revenue. It’s wishful thinking but it’s human nature.

My first question is, can Democrats come up with something along those lines too, which uses wishful thinking and fuzzy math to get what they want done? How about they come up with an economic model for how getting rid of big banker bonuses and terrible corporate governance will improve the economy, with a reference to a calculus theorem thrown in for authentification purposes?

My second question is, can we get to the point where people can figure out they are being manipulated by wishful thinking and fuzzy math with unnecessary references to calculus theorems? I know, wishful thinking.

VAM versus what?

A few astute readers pointed out to me that in the past few days I both slammed the Value-added teacher’s model (VAM) and complained about people who reject something without providing an alternative. Good point, and today I’d like to start that discussion.

What should we be doing instead of VAM?

First of all, I do think that not rating teachers at all is better than the current system. So my “compare the the status quo” argument goes through in this instance. Namely, VAM is actively discouraging teachers whereas leaving them alone entirely would neither discourage or encourage anyone. So better than this.

At the same time, I am a realist, and I think there should be, ultimately, a system of evaluating teachers, just as there is a system for evaluating me at work. The difference between my workplace, of 45 people, and the NYC public schools is scale. It makes sense to have a very large and consistent evaluation system in the NYC public schools, whereas my job can have an ad hoc inconsistent system without it being a problem.

There’s another problem which is nearly impossible to tease from this discussion. Namely, the fact that what’s going on in NYC is a disingenuous political game between Bloomberg and the teacher’s union. Just to emphasize how important that fight is, let’s keep in mind that as of now, although the union is much weaker than it historically has been, it still has the tenure system. So any model, VAM or not, of evaluation is somewhat irrelevant for “removing bad teachers” given that they have tenure and tenure still means something.

Probably the best way to decouple the “Bloomberg vs. union/tenure” issue (a massive one here in NYC) from the “VAM versus other” question is to think nationally rather than citywide.

The truth is, the VAM is being tried out all over the country (although I don’t have hard numbers on this) and the momentum is for it to be used more and more. I predict within 10 years it will be done systematically everywhere in the country.

And, sadly, that’s kind of my prediction whether or not the underlying model is any good or not! The truth is, there is a large contingent of technocrats who want control over the evaluation system and believe in the models, whether or not they are producing pure noise or not. In other words, they believe in “data driven decisioning” as a holy grail even though there’s scant evidence that this will work in schools. And they also don’t want to back down now, even though the model sucks, because they feel like they’ll be losing momentum on the overall data-driven approach.

One thing I know for sure is that we should continue to be aware of how badly the current models are, and I want to set up an open source version of the models (see this post to get an idea how it could work) to exhibit that. In other words, even if we don’t turn off the models altogether, can’t we at least minimize their importance while their quality is bad? The first step is to plainly exhibit how bad they are.

It’s hard for me to decide what to do next, though. I’m essentially a modeler who is hugely skeptical of models. In fact, I don’t think using purely quantitative models to evaluate teachers is the right thing to do, period. Yet I feel like if it’s definitely going to happen, better for people like me to be in the middle of it, pointing out how bad the proposed (or in use) models are actually performing, and improving them.

One thing I know I’d do if I were to be put in charge of creating a better model: I’d train on data where the teacher is actually rated as a good teacher or not. In other words, I wouldn’t proxy “good teacher” by “if your students scored better than expected on tests”. A good model would be trained on data where there would be an expert teacher scorer, who would go into 500 classrooms and carefully evaluate the actual teachers, based on things like whether the teacher asked questions, or got the kids engaged, or talked too much or too little, or imposed too much busy work, etc. Then the model would be trying to mimic this expert.

Of course there are lots of really complicated issues to sort out- and they are *totally unavoidable*. This is why I’m so skeptical of models, by the way: people think you can simplify stuff when you actually can’t. There’s nothing simple about teaching and whether someone’s a good teacher. It’s just plain complex. A simple model will be losing too much information.

Here’s one. Different people think good teaching is different. A possible solution: maybe we could have 5 different “expert models” based on different people’s definitions of good teaching, and every teacher could be evaluated based on every model. Still need to find those 5 experts that teachers trust.

Here’s another. The kind of teacher-specific attributes collected for this test would be different from the VAM- things that happen inside a classroom (like percentage of time teacher talks vs. student, the tone of the discussion, the number and percentage of kids involved in the discussion, etc,) and are harder to capture accurately. These are technological hurdles that are hard.

I think one of the most important questions is whether we can come up with an evaluation system that would be sufficiently reasonable and transparent that the teachers themselves would get on board.

I’d to hear more ideas.

Quants for the rest of us

A few days ago I wrote about the idea of having a quant group working for consumers rather than against them. Today I wanted to spell out a few things I think that group could do.

The way I see it, there’s this whole revolution of data and technology and modeling going on right now, but only people with enough dough to pay for the quants are actually actively benefiting from the revolution. So people in finance, obviously, but also internet advertising companies.

The problem with this, besides the lopsidedness of it all, is that the actual models being used are for the most part predatory rather than helpful to the average person.

In other words, most models are answering question of the form:

- how can we get you to spend money you don’t necessarily want to spend? or

- how good a credit risk are you? or

- how likely are you to come back and spend more money? or

- how can we anticipate the market responding to end-of-month accounting shenanigans? I just threw this one in to give people a sense of how finance models work.

It all makes sense: these are businesses that are essentially bloodthirsty, making their money off your clicks and purchases. They are not going away.

Then there are some models that are already out there trying to make the user experience more enjoyable. They answer questions of the form:

- If you like that, what else may you like? (Pandora, Netflix, Google)

- If you bought that last week, maybe you’d like to buy it again this week?

- If you bought that, maybe you’d like to buy this now?

The problem, as you can see, is that these second, helpfulish kinds of things quickly devolve into the first, predatory kinds of things. In other words, you’re being bombarded by ads and suggestions for spending more money than you actually want to spend.

What about stuff that you actually don’t want to do but that is probably not directly profitable to anyone? I’d love to see technology used to tackle some of these chores:

- Figuring out what the best deal is on loans (credit card, student loans or mortgages), without becoming a lawyer. Here I’m not just saying they should all be clear about their terms- that’s a job for the CFPB. I mean there should be a website that asks me a few questions about what I need a loan for and points me to the best deal available.

- Finding the best price for something. I discussed this briefly here.

- Warnings about weird conditions and agreements, like mandatory arbitration.

- Help finding a good doctor or a good plumber etc.

- Help knowing when to go to the DMV or other public services building so the lines are bearable, or even better a way to do stuff on your computer or phone and avoid the trip altogether.

- Getting your kids’ medical records to their schools and camps safely and efficiently.

Some of these things already exist (like the doctor thing) but aren’t well-known or well-publicized, so wouldn’t it be cool if this quant group also provided an app that would aggregate all these services into one place?

And for the things like #4, where you want to be warned before you buy, it’s too much work to go back to a webpage to check everything before buying. Instead, the app could follow you around the web when you’re shopping and overlay a “bullshit warning” icon on the potential purchase in situations where people have complained about unreasonable terms and conditions.

Let’s use technology in our favor. Instead of the companies collecting information about us, let’s collect information about them. Come to think of it, the CFPB should start this quant group today.

Versus what?

I’m going to specialize in short, curmudgeony blog posts this week.

Today’s topic: you always need something to compare a new thing with. It’s this versus what?

If it’s a model, compare it to noise. That is, go ahead and test a model by scrambling the “y”s and see how well your model predicts randomness. It’s a really good and inexpensive way of seeing whether your model is better than noise, so go ahead and do it. There’s even a name for this but I forget what it is (update from reader: permutation testing).

If it’s a plan for a system or the world, compare it to the status quo. I’m so sick of people discarding good plans because they’re not perfect. If they’re better than what’s currently going on, then let’s go with that. Which brings me to my last example.

If it’s someone’s proposal (person A), compare it to other proposals (person B). I don’t think it’s fair for people (person C) to nix an idea unless they come up with a better one. If person C is consistently doing that, it’s a good bet that they have something to protect in the status quo situation, which brings us to the previous example.

The Value Added Teacher Model Sucks

Today I want you to read this post (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg) written by Gary Rubinstein, which is the post I would have written if I’d had time and had known that they released the actual Value-added Model scores to the public in machine readable format here.

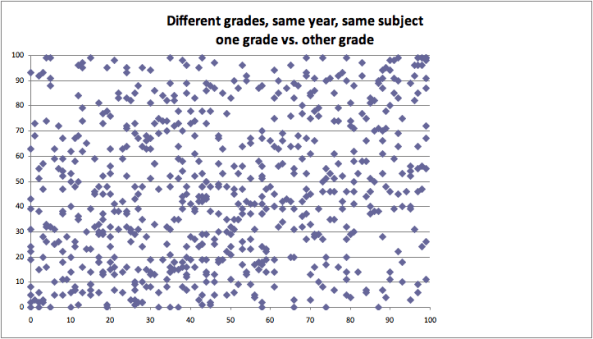

If you’re a total lazy-ass and can’t get yourself to click on that link, here’s a sound bite takeaway: a scatter plot of scores for the same teacher, in the same year, teaching the same subject to kids in different grades. So, for example, a teacher might teach math to 6th graders and to 7th graders and get two different scores; how different are those scores? Here’s how different:

Yeah, so basically random. In fact a correlation of 24%. This is an embarrassment, people, and we cannot let this be how we decide whether a teacher gets tenure or how shamed a person gets in a newspaper article.

Just imagine if you got publicly humiliated by a model with that kind of noise which was purportedly evaluating your work, which you had no view into and thus you couldn’t argue against.

I’d love to get a meeting with Bloomberg and show him this scatter plot. I might also ask him why, if his administration is indeed so excited about “transparency,” do they release the scores but not the model itself, and why they refuse to release police reports at all.

Why experts?

I recently read a Bloomberg article (via Naked Capitalism) about wine critics and how they have better powers of taste than we normal people do.

One of the things I love about this article is how it’s both completely dead obvious and at the same time totally outrageous when you think about it.

Obvious because when we see wine experts going on and on about what they can discern in their tiny sip, we know they either have magical powers or they’re lying, and since some of them can do this shit blindfolded we will assume they aren’t lying.

Outrageous because if you think about it, that means we follow the advice of people whose taste is provably different from ours. In other words, the word of experts is fundamentally irrelevant to us, and yet we care about it anyway.

My question is, why do we care?

Just to go over a couple of ground rules. First, yes, let’s assume that the wine experts really do have powers of discernment that are incredible and unusual, even though we have to trust an expert on that, which may seem contradictory. The truth is, this isn’t the first study that’s shown that, and I for one have hung out with these guys and they really do taste that minerally soil in the wine. I’m not even jealous.

Second, I’m not saying you care about wine experts’ opinions, but lets face it, lots of people do. And you could say it’s because of the performance that the experts give when they smell the wine and describe it, and I’ll agree that some of them can be poets, and that’s nice to see. But the truth is they also rate the wines with a number, and these numbers are printed in books, and lots of people carry these books around to wine shops and devote themselves to only buying wines with sufficiently high numbers, even though those people probably don’t themselves have the mouth smarts to tell the difference.

Now that we’ve framed the question, we can go ahead and make guesses as to why. Here are mine:

- People are hoping that they themselves are also supertasters. This kind of seems like the most obvious one, but I can’t help think that true supertasters would not need other people’s opinions at all.

- People think experts’ opinion of “good”, even if not completely the same as theirs, will be highly correlated, and so is better than nothing.

- People want to be seen drinking wine that supertasters would drink, as a sort of cachet thing.

I think #3 above is pretty much the definition of snob, and I think it exists but is not the major reason people do things (but I could be wrong). I’m guessing it’s more typically #2, but even so it doesn’t explain the really expensive high-end wine market’s huge appeal, unless there are way more supertasters than I thought out there.

I think this question, of why people listen to expert advice even when it’s mostly irrelevant, is an important one, because it happens so much in our culture, and clearly not just about wine.

I for one am attracted to the idea of going one step further and ignoring expert advice. I see a natural progression: first, people are ignorant, second, they learn what experts think, and third, they ignore experts and go with their gut.

But even sexier is the idea of never listening to experts at all: skip step two. Am I the only person who thinks that’s sexy? I mean, I guess it mostly means you’re wasting your time, but it also comes out in the end with less herd mentality.

I think this desire I have of skipping the expert advice is very tied into why I despise the echo chamber of the web and how we are profiled online and how our environment is constantly updated and tailored to our profile. It’s in some sense an expert opinion on what we’d like, given our behavior, and I hate the finiteness of that concept, possibly in part because I’ve designed models like that and I know how dumb they are.

Anyway, I’d love to hear your thoughts, and if I’ve missed any reasons why people like to hear partially relevant expert opinion.

Do not track vs. don’t track

There’s been some buzz about a new “do not track” button that will be installed in coming versions of browsers like google chrome. The idea is to allow people their privacy online, if they want it.

The only problem is, it doesn’t give people privacy. It only blocks some cookies (called third-party cookies) but allows others to stick.

Don’t get me wrong- without third-party cookies, the job I do and every other data scientist working in the internet space will get harder. But please don’t think you’re not being tracked simply by clicking on that.

And as I understand it, it isn’t even clear that third-party cookies won’t be added: I think it’s just an honor system thing, so third-party cookie pasters will be politely asked not to add their cookies.

But don’t believe me, visualize your own cookies as you travel the web. The guy (Atul Varma) who wrote this also open-sourced the code, which is cool. See also the interesting conversation in comments on his blog Toolness.

Let me suggest another option, which we can call “don’t track”. It’s when nothing about what you do is saved. There’s a good explanation of it here, and I suggest you take a look if you aren’t an expert on tracking. They make a great argument for this: if you’re googling “Hepatitis C treatments” you probably don’t want that information saved, packaged, and sold to all of your future employers.

They also have a search engine called “DuckDuckGo” which seems to work well and doesn’t track at all, doesn’t send info to other people, and doesn’t save searches.

I’m glad to see pushback on these privacy issues. As of now we have countless data science teams working feverishly in small companies to act as predators against consumers, profiling them, forecasting them, and manipulating their behavior. I’m composing a post about what a data science team working for consumers would have on their priority list. Suggestions welcome.

Math-Startup Collaborative at Columbia tomorrow

The Columbia Chapter of SIAM (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics) invites YOU to:

Spring 2012 Math-Startup Collaborative Wednesday, February 29 | 6:00 – 8:00 PM | Davis Auditorium, Schapiro Center

Meet Columbia alumni from NYC startups, including Bitly, Foursquare, and Codecademy, and learn about the role of math and engineering in their companies. Students interested in startup careers and internships, or those simply curious to see how math is applied in the wild, are especially welcome. The event, which consists of a series of presentations from our startup members, will be followed by a reception (with free food!). This is sure to be the largest applied math event of the semester!

Startup presenters include:

- Bitly –> http://blog.bitly.com/

- Foursquare –> https://foursquare.com/about/

- Codecademy –> http://blog.codecademy.com/

- BuzzFeed –> http://www.buzzfeed.com/about

- Sailthru –> http://blog.sailthru.com/

Space is limited! Contact Ilana Lefkovitz (itl2103@columbia.edu) for more information.

Please RSVP at bit.ly/Math–Startup-RSVP-2012

Co-sponsored by the Application Development Initiative (ADI). Reception sponsored by AOL Ventures.