New schwag for the Stacks Project

This just in from zazzle.com: Stacks Project cups and shirts, to celebrate the recent upgrade on Stacks Project viz.

An unflattering yet adorable picture of both me and Johan in Stacks Project t-shirts, new and old. Unfortunately the colors came out too light. You can see we’re both instructing our 11-year-old on how to take a picture and our 4-year-old is squeezing in too. He’s not shy.

Survivorship bias for women in men’s fields

I like this essay written by Annie Gosfield, a self-described “composeress”, which is her word to mean a female composer. She finds it slightly absurd to be singled out for her femaleness. Her overall take on being a woman in a man’s world is refreshing, and resonates with me as a woman in math and technology.

From her essay:

I’ve never considered myself a “woman composer,” but I suspect that over the years being female has helped more than it’s hurt. Being a woman (and having high hair) has made me easier to recognize, easier to remember and has spared me from fitting into the generic description of a composer: “medium build, dark hair, glasses, beard.” I will admit to liking the invented honorific term “composeress.” (It sounds archaic, grand, and slightly ridiculous, just as a gender-specific title for a composer should.)

So, great for her, and wonderful that from her perspective she feels propelled rather than suffocated by her otherness status. To some extent I agree from my own experience.

But having said that, it doesn’t mean that other women, possibly many other women, haven’t been squeezed out, or have selected out, because of their female status. After all, we hear way more from the people who stay and “succeed”, which tends to give us massive survivorship bias.

Indeed, and to be nerdy and true to form, we can almost think about measuring the extent to which there is a weeding-out effect of women by asking the survivors the extent to which they identify as “women” versus the population at large. I think we’d find that the women who survive in nearly all-male environments have developed, or were born with, coping mechanisms which allow them to ignore their own otherness.

I know that was true of me – when I was in grad school at Harvard, I went through a distinct phase of wanting to wear men’s clothing, or at least gender neutral clothing – so jeans, t-shirts, leather shoes, never dresses – to be externally more consistent with how I felt inside. Not that I was sexually identified with men, but that I didn’t want to be seen as primarily feminine. Instead I wanted to be seen as primarily a mathematician.

Does it make me a freak, to wear men’s clothing and (sometimes) wish I could grow a beard? Possibly, although over time it’s changed, and nowadays I take pride in my femininity, and in fact I think much of my power emanates from it.

But it does give me pause when I hear successful women in men’s fields talking about how great it is to be a woman and how surprising all the attention is. We still seem to be contorting ourselves in an effort to not seem too womanly, and this makes me think it’s entirely un-coincidental, and possibly a crucial part of what allows us to succeed. Besides talent and hard work, of course. And I don’t think it’s undue attention at all – I think it’s just something we train ourselves not to consider because focusing on it too much could be paralyzing.

By the way, I’m not doing justice to Annie Gosfield’s essay, which you should read in its entirety and has nuanced things to say about otherness in the field of composing.

Minorities possible unfairly disqualified from opening bank accounts

My friend Frank Pasquale sent me this article over twitter, about New York State attorney general Eric T. Schneiderman’s investigation into possibly unfair practices by big banks using opaque and sometimes erroneous databases to disqualify people from opening accounts.

Not much hard information is given in the article but we know that negative reports stemming from the databases have effectively banished more than a million lower-income Americans from the financial system, and we know that the number of “underbanked” people in this country has grown by 10% since 2009. Underbanked people are people who are shut out of the normal banking system and have to rely on the underbelly system including check cashing stores and payday lenders.

I can already hear the argument of my libertarian friends: if I’m a bank, and I have reason to suspect you have messed up with your finances in the past, I don’t offer you services. Done and done. Oh, and if I’m a smart bank that figures out some of these so-called “past mistakes” are actually erroneously reported, then I make extra money by serving those customers that are actually good when they look bad. And the free market works.

Two responses to this. First, at this point big banks are really not private companies, being on the taxpayer dole. In response they should reasonably be expected to provide banking services to all of not most people as part of a service. Of course this is a temporary argument, since nobody actually likes the fact that the banks aren’t truly private companies.

The second, more interesting point – at least to me – is this. We care about and defend ourselves from our constitutional rights being taken away but we have much less energy to defend ourselves against good things not happening to us.

In other words, it’s not written into the constitution that we all deserve a good checking account, nor a good college education, nor good terms on a mortgage, and so on. Even so, in a large society such as ours, such things are basic ingredients for a comfortable existence. Yet these services are rare if not nonexistent for a huge and swelling part of our society, resulting in a degradation of opportunity for the poor.

The overall effect is heinous, and at some point does seem to rise to the level of a constitutional right to opportunity, but I’m no lawyer.

In other words, instead of only worrying about the truly bad things that might happen to our vulnerable citizens, I personally spend just as much time worrying about the good things that might not happen to our vulnerable citizens, because from my perspective lots of good things not happening add up to bad things happening: they all narrow future options.

Should lawmakers use algorithms?

Here is an idea I’ve been hearing floating around the big data/ tech community: the idea of having algorithms embedded into law.

The argument for is pretty convincing on its face: Google has gotten its algorithms to work better and better over time by optimizing correctly and using tons of data. To some extent we can think of their business strategies and rules as a kind of “internal regulation”. So why don’t we take a page out of that book and improve our laws and specifically our regulations with constant feedback loops and big data?

No algos in law

There are some concerns I have right off the bat about this concept, putting aside the hugely self-serving dimension of it.

First of all, we would be adding opacity – of the mathematical modeling kind – to an already opaque system of law. It’s hard enough to read the legalese in a credit card contract without there also being a black box algorithm to make it impossible.

Second of all, whereas the incentives in Google are often aligned with the algorithm “working better”, whatever that means in any given case, the incentives of the people who write laws often aren’t.

So, for example, financial regulation is largely written by lobbyists. If you gave them a new tool, that of adding black box algorithms, then you could be sure they would use it to further obfuscate what is already a hopelessly complicated set of rules, and on top of it they’d be sure to measure the wrong thing and optimize to something random that would not interfere with their main goal of making big bets.

Right now lobbyists are used so heavily in part because they understand the complexity of their industries more than the lawmakers themselves. In other words, they actually add value in a certain way (besides in the monetary way). Adding black boxes would emphasize this asymmetric information problem, which is a terrible idea.

Third, I’m worried about the “black box” part of algorithms. There’s a strange assumption among modelers that you have to make algorithms secret or else people will game them. But as I’ve said before, if people can game your model, that just means your model sucks, and specifically that your proxies are not truly behavior-based.

So if it pertains to a law against shoplifting, say, you can’t have an embedded model which uses the proxy of “looking furtive and having bulges in your clothes.” You actually need to have proof that someone stole something.

If you think about that example for a moment, it’s absolutely not appropriate to use poor proxies in law, nor is it appropriate to have black boxes at all – we should all know what our laws are. This is true for regulation as well, since it’s after all still law which affects how people are expected to behave.

And by the way, what counts as a black box is to some extent in the eye of the beholder. It wouldn’t be enough to have the source code available, since that’s only accessible to a very small subset of the population.

Instead, anyone who is under the expectation of following a law should also be able to read and understand the law. That’s why the CFPB is trying to make credit card contracts be written in Plain English. Similarly, regulation law should be written in a way so that the employees of the regulator in question can understand it, and that means you shouldn’t have to have a Ph.D. in a quantitative field and know python.

Algos as tools

Here’s where algorithms may help, although it is still tricky: not in the law itself but in the implementation of the law. So it makes sense that the SEC has algorithms trying to catch insider trading – in fact it’s probably the only way for them to attempt to catch the bad guys. For that matter they should have many more algorithms to catch other kinds of bad guys, for example to catch people with suspicious accounting or consistently optimistic ratings.

In this case proxies are reasonable, but on the other hand it doesn’t translate into law but rather into a ranking of workflow for the people at the regulatory agency. In other words the SEC should use algorithms to decide which cases to pursue and on what timeframe.

Even so, there are plenty of reasons to worry. One could view the “Stop & Frisk” strategy in New York as following an algorithm as well, namely to stop young men in high-crime areas that have “furtive motions”. This algorithm happens to single out many innocent black and latino men.

Similarly, some of the highly touted New York City open data projects amount to figuring out that if you focus on looking for building code violations in high-crime areas, then you get a better hit rate. Again, the consequence of using the algorithm is that poor people are targeted at a higher rate for all sorts of crimes (key quote from the article: “causation is for other people”).

Think about this asymptotically: if you live in a nice neighborhood, the limited police force and inspection agencies never check you out since their algorithms have decided the probability of bad stuff happening is too low to bother. If, on the other hand, you are poor and live in a high-crime area, you get checked out daily by various inspectors, who bust you for whatever.

Said this way, it kind of makes sense that white kids smoke pot at the same rate as black kids but are almost never busted for it.

There are ways to partly combat this problem, as I’ve described before, by using randomization.

Conclusion

It seems to me that we can’t have algorithms directly embedded in laws, because of the highly opaque nature of them together with commonly misaligned incentives. They might be useful as tools for regulators, but the regulators who choose to use internal algorithms need to carefully check that their algorithms don’t have unreasonable and biased consequences, which is really hard.

Ask Aunt Pythia – special Sunday edition

Guys, I messed up. I have been traveling two weeks in a row and I plumb forgot what day it was yesterday and thus, sadly, ignored my inner Aunt Pythia and her advice. I’m making up for it now, and I’m sending out major league apologies to people who were disappointed by the bullshit complaint about Indiana school politics yesterday instead of the sass you’ve grown to love from Auntie P.

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I completed a BA in economics a number of years ago (well before the economy went to heck-in-a-handbasket), but didn’t immediately pursue a graduate degree. Instead of focusing on my career, I dedicated myself to a charity project–building a community school in a very poor country–which took a lot of my time and financial resources. Now, the project is up and running on its own and I’m thinking again about career paths (in order to be able to fund bigger and better philanthropic works, if nothing else).

I’ve had the obvious thought of continuing my education with a MA or PhD program, but I’m not entirely convinced that doing so will actually improve my prospects for landing a plumb job. It will, on the other hand, be sure to cost me plenty of moola. What do you think: is going into debt in order to obtain an advanced degree a wise financial decision in this economic climate? If not, what other steps do you think would be helpful for an underemployed intellectual looking to move out of manual labor and into something more “white collar,” ideally without having to sell his/her soul?

Or maybe it’s just that are some of us just stuck down here on the lower rungs of the income distribution and had better just get used to it. That is what I tend to think, but I’ve been accused of pessimism before and thought maybe you might have something less depressing to suggest.

Feeling Out Obvious Limits

Dear FOOL,

I gotta say, I’m not sure. I’m not an expert on jobs in Econ. But I’ll tell you what, if it’s like math, it’s not kind to people who take time off. I think this is a huge mistake, and obviously one that affects women more than men. If math, as a community, were serious about attracting good women, they’d change this bias. But I don’t see that happening soon. Ditto with probability 90% for Econ.

Having said that, it sounds like what you’ve accomplished is real, and although it’s possibly invisible to certain academic communities, I’d bet it isn’t to others, like the business community. If you’re a quantitative person who’s build a working charity (amazing!), then you could probably convince someone to give you a good job.

How about you look into getting a masters degree in something you’re interested in that’s also quantitative, and then rebuild yourself as an experienced team-builder?

Good luck!

Aunt P

——

Dear Pythia,

A Platonic friend from undergrad analysis class and I were walking on the beach together one sunny day, several years ago. She suggested we take our shoes and socks off and wade in the water, which we did. When it came time to put our shoes back on, while deftly balancing on one foot like a flamingo, I dried off my free foot with a sock, put the sock on, then the shoe, then repeated the process for the other foot, all without a hitch. Whether real, or possibly feigned premeditatedly, my companion was exhibiting quite the struggle a few feet away. Perhaps because I am more attracted to skill and independence than incompetence and dependence, I just stood by and watched. Would you agree that this was the right thing to do, or am I in for a scolding instead?

Free Bird

Dear Free,

This is a great example of a question that says more about the questioner than anything about the question.

Putting that aside, and to answer your putative question: you have no obligation to help a grownup put on their socks. But you do have an obligation to forget about how a friend puts on their socks within at most 2 days, and you have a definite obligation to not judge them for their sock-putting-on-technique on a sandy beach. Plus, it wasn’t a way to get into your pants, if that’s what you mean.

Good luck,

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have a question about a question you actually answered (see last question answered here) for your revival.

If ‘D’ stands for ‘Dry’ and ‘G’ stands for ‘Got laid’, don’t you actually think that there would be some sort of stickiness (or state-dependence) coming in? I mean, I have the impression – maybe fallacious – that there is some sort of cold feet effect with getting laid: once you’ve entered the ‘dry’ state, your probability to remain in that state is actually increasing.

In other words, don’t you think that is actually increasing with

? How would you test for that?

There are several mechanisms behind that I think (and I will speak for myself here): it’s becoming more and more obvious that you’re sex-starved, and this is a big put-off, because that may be interpreted as being a lousy lover. You may also have less and less patience for the required chitchat before the physical fun etc.

The above may hold for males but not for females.

I’m not so sure about the other conditional probability mainly because I’ve little experience in staying very long in the ‘G’ state; but would be curious to know more about it.

Cheers,

Canada Dry

Dear Canada,

Great points! And eminently modelable, which I appreciate, although the data collection would be a bitch, especially considering how much people lie about getting laid (see first answer here).

I don’t agree that the underlying effect doesn’t effect women though. The concept that “if I haven’t gotten laid in a long time my chances are actively going down” definitely seems true for many of my friends, male and female, and I don’t think it’s because they are perceived as lousy lovers.

After all, it’s not like there’s a ticker tape on their foreheads counting up the second since their last sexual encounter. Instead, I think it’s part pheromones and part self-regard. If you feel unattractive, you don’t act like a sexy thang and people are less likely to approach you.

Similarly, if you’ve gotten laid recently, you feel sexy, which makes you act like a sexy person, which is hot in itself, and also you have sex pheromones dripping off of you, which attracts the opposite sex like flies to a lightbulb.

By the way, if you’re a woman and you want a leg up on the process, may I suggest you buy synthetic female pheromones from the Athena Institute. Some of my friends swear by this, and claim it makes men desire them and/or be nice to them. Let’s say it this way: it either works or it works as a placebo.

One last thing: I think the community you live in makes a big difference for these dependent probabilities. If you have been dry for a long time but you have a good set of wingwomen or wingmen, then you’re way better off than if you’re isolated socially.

Good luck, Canada Dry! Go hang with your buddies and get them on board for your worthy cause!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I spent my childhood as a lonely nerd with no friends. Over college and beyond I made friends and learned to have deep, meaningful relationships with people. Then I spent a few years working at a nonprofit, making the world a better place. I made a lot of money while helping to ease the pain associated with a number of types of cancer. And now I’m in my late 30s and rich.

I want to experience the shallow life that I see so many people around me enjoying but I have no idea how to do it. I’d try to buy my way in, but I don’t know where to begin. I’ve heard that girls go for guys with money, but don’t know where to find these girls.

Seriously, I need help being superficial for a while.

Want to be shallow

Dear WtbS,

Please let me be the first person to tell you that you’re already quite superficial. Congratulations!

Just the way you’re talking about “girls” makes me kind of gag, as if they’re lego parts that can be bought, traded, and sold. Plus you also sound crazy smug about your accomplishments, another strong signal for superficiality. So I honestly don’t think I need to give you any more advice on that front.

What I think you actually are wondering is how to be happy, or possibly happy in a hedonistic way. But the sneaky little thing about really enjoying a hedonistic lifestyle is, in my opinion, that you have real connections with the other people in your company. Otherwise you might just wake up feeling empty and crappy. It’s fun to do stupid sexy things with your friends if everyone’s into it, it’s not fun to do stupid sexy things with strangers whose motivations you don’t know, especially if you’re young and rich, because even if you don’t know, I will.

So my advice: go back to your college-aged talents and make deep connections with people who are also fun-loving and slightly crazy. It will take a few months but you might just be able to live like a fucking rock star.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Educational accountability scores get politically manipulated again

My buddy Jordan Ellenberg just came out with a fantastic piece in Slate entitled “The Case of the Missing Zeroes: An astonishing act of statistical chutzpah in the Indiana schools’ grade-changing scandal.”

Here are the leading sentences of the piece:

Florida Education Commissioner Tony Bennett resigned Thursday amid claims that, in his former position as superintendent of public instruction in Indiana, he manipulated the state’s system for evaluating school performance. Bennett, a Republican who created an A-to-F grading protocol for Indiana schools as a way to promote educational accountability, is accused of raising the mark for a school operated by a major GOP donor.

Jordan goes on to explain exactly what happened and how that manipulation took place. Turns out it was a pretty outrageous and easy-to-understand lie about missing zeroes which didn’t make any sense. You should read the whole thing, Jordan is a great writer and his fantasy about how he would deal with a student trying the same scam in his calculus class is perfect.

A few comments to make about this story overall.

- First of all, it’s another case of a mathematical model being manipulated for political reasons. It just happens to be a really simple mathematical model in this case, namely a weighted average of scores.

- In other words, the lesson learned for corrupt politicians in the future may well to be sure the formulae are more complicated and thus easier to game.

- Or in other words, let’s think about other examples of this kind of manipulation, where people in power manipulate scores after the fact for their buddies. Where might it be happening now? Look no further than the Value-Added Model for teachers and schools, which literally nobody understands or could prove is being manipulated in any given instance.

- Taking a step further back, let’s remind ourselves that educational accountability models in general are extremely ripe for gaming and manipulation due to their high stakes nature. And the question of who gets the best opportunity to manipulate their scores is, as shown in this example of the GOP-donor-connected school, often a question of who has the best connections.

- In other words, I wonder how much the system can be trusted to give us a good signal on how well schools actually teach (at least how well they teach to the test).

- And if we want that signal to be clear, maybe we should take away the high stakes and literally measure it, with no consequences. Then, instead of punishing schools with bad scores, we could see how they need help.

- The conversation doesn’t profit from our continued crazy high expectations and fundamental belief in the existence of a silver bullet, the latest one being the Kipp Charter Schools – read this reality check if you’re wondering what I’m talking about (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg).

- As any statistician could tell you, any time you have an “educational experiment” involving highly motivated students, parents, and teachers, it will seem like a success. That’s called selection bias. The proof of the pudding lies in the scaling up of the method.

- We need to think longer term and consider how we’re treating good teachers and school administration who have to live under arbitrary and unfair systems. They might just leave.

How much is the Stacks Project graph like a random graph?

This is a guest post from Jordan Ellenberg, a professor of mathematics at the University of Wisconsin. Jordan’s book, How Not To Be Wrong, comes out in May 2014. It is crossposted from his blog, Quomodocumque, and tweeted about at @JSEllenberg.

Cathy posted some cool data yesterday coming from the new visualization features of the magnificent Stacks Project. Summary: you can make a directed graph whose vertices are the 10,445 tagged assertions in the Stacks Project, and whose edges are logical dependency. So this graph (hopefully!) doesn’t have any directed cycles. (Actually, Cathy tells me that the Stacks Project autovomits out any contribution that would create a logical cycle! I wish LaTeX could do that.)

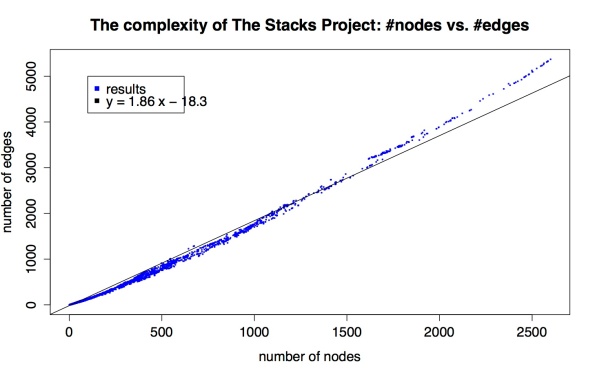

Given any assertion v, you can construct the subgraph G_v of vertices which are the terminus of a directed path starting at v. And Cathy finds that if you plot the number of vertices and number of edges of each of these graphs, you get something that looks really, really close to a line.

Why is this so? Does it suggest some underlying structure? I tend to say no, or at least not much — my guess is that in some sense it is “expected” for graphs like this to have this sort of property.

Because I am trying to get strong at sage I coded some of this up this morning. One way to make a random directed graph with no cycles is as follows: start with N edges, and a function f on natural numbers k that decays with k, and then connect vertex N to vertex N-k (if there is such a vertex) with probability f(k). The decaying function f is supposed to mimic the fact that an assertion is presumably more likely to refer to something just before it than something “far away” (though of course the stack project is not a strictly linear thing like a book.)

Here’s how Cathy’s plot looks for a graph generated by N= 1000 and f(k) = (2/3)^k, which makes the mean out-degree 2 as suggested in Cathy’s post.

Pretty linear — though if you look closely you can see that there are really (at least) a couple of close-to-linear “strands” superimposed! At first I thought this was because I forgot to clear the plot before running the program, but no, this is the kind of thing that happens.

Is this because the distribution decays so fast, so that there are very few long-range edges? Here’s how the plot looks with f(k) = 1/k^2, a nice fat tail yielding many more long edges:

My guess: a random graph aficionado could prove that the plot stays very close to a line with high probability under a broad range of random graph models. But I don’t really know!

Update: Although you know what must be happening here? It’s not hard to check that in the models I’ve presented here, there’s a huge amount of overlap between the descendant graphs; in fact, a vertex is very likely to be connected all but c of the vertices below it for a suitable constant c.

I would guess the Stacks Project graph doesn’t have this property (though it would be interesting to hear from Cathy to what extent this is the case) and that in her scatterplot we are not measuring the same graph again and again.

It might be fun to consider a model where vertices are pairs of natural numbers and (m,n) is connected to (m-k,n-l) with probability f(k,l) for some suitable decay. Under those circumstances, you’d have substantially less overlap between the descendant trees; do you still get the approximately linear relationship between edges and nodes?

Analyzing the complexity of the Stacks Project graphs

So yesterday I told you about the cool new visualizations now available on Johan’s Stack Project.

But how do we use these visualizations to infer something about either mathematics or, at the very least, the way we think about mathematics? Here’s one way we thought of with Pieter.

So, there’s a bunch of results, and each of them has its own subgraph of the entire graph which positions that result as the “base node” and shows all the other results which it logically depends on.

And each of those graphs has structure and attributes, the stupidest two of which are the just counts of the nodes and edges. So for each result, we have an ordered pair (#nodes, #edges). What can we infer about mathematics from these pairs?

Here’s a scatter plot of the nodes-vs-edges for each of the 10,445 results (email me if you want to play with this data yourself):

I also put a best-fit line in, just to illustrate that the scatter plot is super linear but not perfectly linear.

So there are a bunch of comments I can make about this, but I’ll limit myself to the following:

- There are a lot of points at (1,0), corresponding to remarks, axioms, beginning lemmas, definitions, and tags for sections.

- As a data person, let me just say that data is never this clean. There’s something going on, some internal structure to these graphs that we should try to understand.

- By “clean” I’m not exactly referring to the fact that things look pretty linear, although that’s weird and we should think about that. What I really mean is that things are so close to the curve that is being approximated. They’re all within a very tight border of this imaginary line. It’s super amazing.

- Let’s pretend it’s just plain straight. Does that make sense, that as graphs get more complex the edges don’t get more dense than some multiple (1.86) of of the number of nodes?

- Kind of: remember, we don’t depict all logical dependency edges, just the ones that are directly referred to in the proof of a result. So right off the bat you are less surprised that the edges aren’t growing quadratically in the number of nodes, even though the number of possible edges is of course quadratic in the number of nodes.

- Think about it this way: assume that every result that requires proof (so, that’s not a (1,0) result) refers to exactly 2 other results in its proof. Then those two child results each correspond to some subgraph of the entire graph, and say their subgraphs each have something like twice as many edges as nodes. Then, ignoring overlap, we’d see two graphs with a 2:1 ratio, then we’d see that parent node, plus two edges leading to each result, which is also a 2:1 ratio, and the disjoint union of all those graphs gives us a large graph with a 2:1 ratio.

- Then if you imagine now allowing the overlap, the ratio goes down a bit on average. In this toy model, the discrepancy between 2.0 and the slope we actually see, 1.86, is a measurement of the collapse of the two child graphs, which can be taken as a proxy for how much the two supporting results overlap as notions.

- Of course, not every result has exactly two children.

- Plus it doesn’t really explain how ridiculously consistent the plot above is. What would?

- If you think about it, the only real explanation of the consistency above is my husband brain.

- In other words, he’s humming along, thinking about stacks, and at some point, when he thinks things have gotten complicated enough, he says to himself “It’s time to wrap this stuff up and call it a result!” and then he does so. That moment, when he’s decided things are getting complicated enough, is very consistent internally to his brain.

- In other words, if someone else created the stacks project, I’d expect to see another kind of plot, possibly also very consistent, but possibly with a different slope.

- Also it’d be interesting to compare this plot to another kind of citation network graph, like the papers in the arXiv. Has anyone made that?

The Stacks Project gets ever awesomer with new viz

Crossposted on Not Even Wrong.

Here’s a completely biased interview I did with my husband A. Johan de Jong, who has been working with Pieter Belmans on a very cool online math project using d3js. I even made up some of his answers (with his approval).

Q: What is the Stacks Project?

A: It’s an open source textbook and reference for my field, which is algebraic geometry. It builds foundations starting from elementary college algebra and going up to algebraic stacks. It’s a self-contained exposition of all the material there, which makes it different from a research textbook or the experience you’d have reading a bunch of papers.

We were quite neurotic setting it up – everything has a proof, other results are referenced explicitly, and it’s strictly linear, which is to say there’s a strict ordering of the text so that all references are always to earlier results.

Of course the field itself has different directions, some of which are represented in the stacks project, but we had to choose a way of presenting it which allowed for this idea of linearity (of course, any mathematician thinks we can do that for all of mathematics).

Q: How has the Stacks Project website changed?

A: It started out as just a place you could download the pdf and tex files, but then Pieter Belmans came on board and he added features such as full text search, tag look-up, and a commenting system. In this latest version, we’ve added a whole bunch of features, but the most interesting one is the dynamic generation of dependency graphs.

We’ve had some crude visualizations for a while, and we made t-shirts from those pictures. I even had this deal where, if people found mathematical mistakes in the Stacks Project, they’d get a free t-shirt, and I’m happy to report that I just last week gave away my last t-shirt. Here’s an old picture of me with my adorable son (who’s now huge).

Q: Talk a little bit about the new viz.

A: First a word about the tags, which we need to understand the viz.

Every mathematical result in the Stacks Project has a “tag”, which is a four letter code, and which is a permanent reference for that result, even as other results are added before or after that one (by the way, Cathy O’Neil figured this system out).

The graphs show the logical dependencies between these tags, represented by arrows between nodes. You can see this structure in the above picture already.

So for example, if tag ABCD refers to Zariski’s Main Theorem, and tag ADFG refers to Nakayama’s Lemma, then since Zariski depends on Nakayama, there’s a logical dependency, which means the node labeled ABCD points to the node labeled ADFG in the entire graph.

Of course, we don’t really look at the entire graph, we look at the subgraph of results which a given result depends on. And we don’t draw all the arrows either, we only draw the arrows corresponding to direct references in the proofs. Which is to say, in the subgraph for Zariski, there will be a path from node ABCD to node ADFG, but not necessarily a direct link.

Q: Can we see an example?

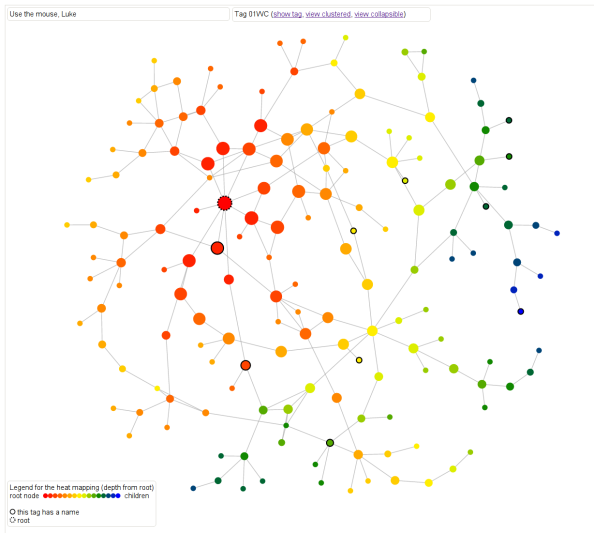

Let’s move to an example for result 01WC, which refers to the proof that “a locally projective morphism is proper”.

First, there are two kinds of heat maps. Here’s one that defines distance as the maximum (directed) distance from the root node. In other words, how far down in the proof is this result needed? In this case the main result 01WC is bright red with a black dotted border, and any result that 01WC depends on is represented as a node. The edges are directed, although the arrows aren’t drawn, but you can figure out the direction by how the color changes. The dark blue colors are the leaf nodes that are farthest away from the root.

Another way of saying this is that the redder results are the results that are closer to it in meaning and sophistication level.

Note if we had defined the distance as the minimum distance from the root node (to come soon hopefully), then we’d have a slightly different and also meaningful way of thinking about “redness” as “relevance” to the root node.

This is a screenshot but feel free to play with it directly here. For all of the graphs, hovering over a result will cause the statement of the result to appear, which is awesome.

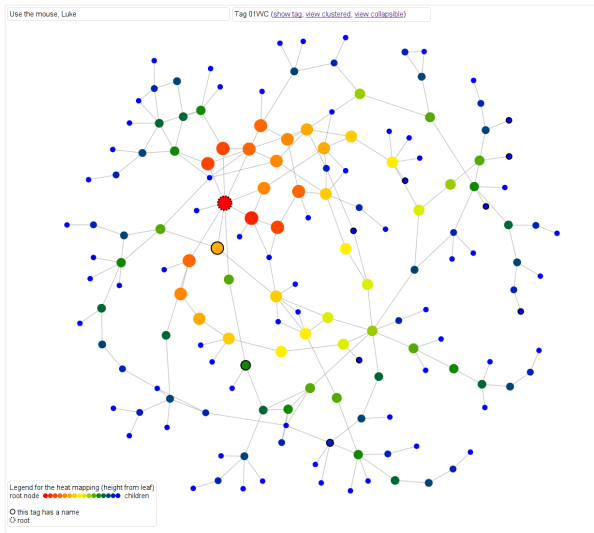

Next, let’s look at another kind of heat map where the color is defined as maximum distance from some leaf note in the overall graph. So dark blue nodes are basic results in algebra, sheaves, sites, cohomology, simplicial methods, and other chapters. The link is the same, you can just toggle between the different metric.

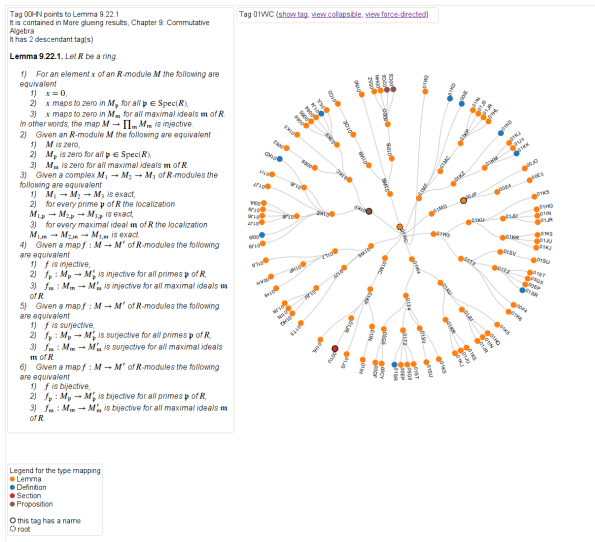

Next we delved further into how results depend on those different topics. Here, again for the same result, we can see the extent to which that result depends on the different on results from the various chapters. If you scroll over the nodes you can see more details. This is just a screenshot but you can play with it yourself here and you can collapse it in various ways corresponding to the internal hierarchy of the project.

Finally, we have a way of looking at the logical dependency graph directly, where result node is labeled with a tag and colored by “type”: whether it’s a lemma, proposition, theorem, or something else, and it also annotates the results which have separate names. Again a screenshot but play with it here, it rotates!

Check out the whole project here, and feel free to leave comments using the comment feature!

Larry Summers being set up to fail?

I’m back from PyData, which was a lot of fun and filled with super nice nerdy people. My prezi slides are now available here.

I have time for one thought: a bunch of people have chatted me up recently with the theory that Larry Summers is being put in the running for the Fed Chair alongside Janet Yellen just so that, when Yellen gets the call, we can all breathe a sigh of relief it didn’t go to Summers.

In other words, it’s a wholly political ploy so the Obama can look like a hero for women everywhere when he chooses Yellen, and so that we can all conclude that at least Obama’s learned this one lesson with regards to dealing with the ongoing financial crisis: Summers isn’t the solution.

Depending on my mood I sometimes buy into this theory, but obviously I’m still worried.

PyData talk today

Not much time because I’m giving a keynote talk at the PyData 2013 conference in Cambridge today, which is being held at the Microsoft NERD conference center.

It’s gonna be videotaped so I’ll link to that when it’s ready.

My title is “Storytelling With Data” but for whatever reason on the schedule handed out yesterday the name had been changed to “Scalable Storytelling With Data”. I’m thinking of addressing this name change in my talk – one of the points of the talk, in fact, is that with great tools, we don’t need to worry too much about the scale.

Plus since it’s Sunday morning I’m going to make an effort to tie my talk into an old testament story, which is totally bizarre since I’m not at all religious but for some reason it feels right. Please wish me luck.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

It’s a speed advice column today, folks, because I’m blogging whilst sitting at the PyData 2013 conference [Aside: I believe in Travis Oliphant, the nerd Santa Claus, do you?]. I’ll try to keep it to the point yet amusing slash provocative.

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m having a baby soon, and I’m planning to be the primary caregiver for a few months (from 3 months onward). I’m hoping that I’ll be able to get some research done at the same time, but I’m not sure how practical that is. What should I expect? Do you have any tips for juggling baby care and math research? (assuming no teaching and minimal responsibilities around the department.)

Baffled About Birth Year

Dear BABY,

Other people are gonna tell you encouraging things like, “oh you can do it!” or “If anybody can do it, it’s you!” but not me.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not telling you you can’t do it, but by acting like it’s just a matter of proper planning, I’d be underselling how much work you’re signing up for, and how fucking hard it really is going to be.

So here’s the real deal: it’s the hardest thing you’ll ever do (hopefully). You know how grad school was hard? This is like having to write a thesis once a year while living 24/7 with someone who’s only goal is for you to not get that done.

Which is to say: be incredibly proud of yourself every day you survive this period, and don’t add an ounce of guilt to yourself that you can avoid. Guilt doesn’t help. And also, the system is set up badly for you, to be sure, but don’t dwell on it too much, that also doesn’t help while you’re in it.

In terms of very practical advice: pay through the nose for good babysitting and daycare, it’s worth the investment so that you don’t have to worry your kid is getting love and attention. Go into debt, borrow money, or whatever, but get it set up so that you actually feel jealous of your kid, and specifically so you know your kid is better off with that situation for the next few hours than being with you.

Finally, when you feel crazy and insane and underproductive, know that it’ll get better, for sure, by the time the kids can wipe their own asses, and that you won’t regret having those beautiful children nor trying to get something else done too. Never apologize for needing to cry and vent about how hard this period is, and if you’re around people who don’t get it, find new people.

Good luck!

Cathy

——

Aunt Pythia,

How do I dress to make people think I am an adult? I’m a 25-year-old woman, and I’m getting a bit tired of people asking me if I’m a student.

I think they ask me this because I only wear jeans and nerdy t-shirts. I basically only own jeans and nerdy t-shirts, plus some cardigans. I am not at all interested in skirts or girly things, but I’m open to wearing slightly nicer clothes. Like more cardigans? Messenger bags that aren’t falling apart? Urk.

People on the internet claim that I need to pluck my eyebrows to be taken seriously, but fuck that shit.

Shopping Is Hard! Let’s Do Math

Dear Sihldm,

First, I gotta say I was expecting a bit more from that sign-off. I really don’t see what “Sihldm” is supposed to mean, but maybe I’m just out of the loop.

Second, I’m gonna say something kind of controversial. Namely, I think the single attribute that makes people take me seriously is the fact that I’m overweight (and that, nowadays, I have grey hair, which also helps).

I think people just stop thinking “girl” and start thinking “woman” when confronted with me, and that totally works to my advantage. Controversial because, according to the social contract, I’m supposed to feel consistently bad about my weight, but here’s an example where I’m like, wow I’ve never been underestimated as a “girl”.

So, my advice to you is: pack on like 100 pounds.

Just kidding, probably not a great plan, nor possible.

Here’s another try: whenever you’re giving a talk or starting a class, wear wool slacks and a sweater. For whatever reason people take you super seriously when you do, even if you’re not fat, and even if you’re short. If it’s summer, go for summer slacks and silk shirts, although not the kind of silk that shows sweat stains easily, those are embarrassing.

And if it’s not a special event like a talk or the first day of class, then fuck it, be yourself.

Good luck!

Cathy

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My husband stays home with the children, but in spite of a graduate degree in engineering and graduate work in mathematics, seems incapable of maintaining a clean house.

My question is, if 95% of the time he doesn’t sort the mail, 75% of the time he doesn’t vacuum, 50% of the time he doesn’t wash the dishes, and 80% of the time he doesn’t wipe the kitchen counters, what is the probability that he doesn’t actually see dirt? (He is color blind.)

Buried in junk mail

Dear Bijm,

Bijm? Really?

Are the kids healthy? Happy? Do they get fed non-dorito-like food? I’d say be grateful. If and when you can afford it get housekeeping, but don’t make the mistake I see so much of allowing resentment to build up over chores.

Also, keep in mind that the kids will be able to help with the chores soon. And by “soon” I mean “probably already”. Buy cute toy-like vacuum cleaners and make up a game about getting all the dirt. Make it part of the dessert ritual that the counters need to be clean first. Move your bills to online payments.

And enjoy your sexy househusband!! [Important aside: is he willing to wear an apron and nothing else when he cooks? Please answer privately, preferably with jpeg-formatted evidence.]

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated ethical quandary to Aunt Pythia!

Huma’s Little Weiner Problem

This is a guest post by my friend Laura Strausfeld.

As an unlicensed psychotherapist, here’s my take on why Huma Abedin is supporting her husband Anthony Weiner’s campaign for mayor:

It’s all about the kid.

Jordan Weiner is 19 months old. When he’s 8 or 9—or 5, and wearing google glasses—maybe he’ll google his name and read about his father’s penis. Either that, or one of his buddies at school may ask him about his father’s penis. Jordan might then ask his mommy and daddy about his father’s penis and they’ll tell him either 1) your daddy was a great politician, but had to resign from Congress because he admitted to showing people his penis, which we recommend you don’t do, especially when you’re a grownup and on twitter; or 2) your daddy was a great politician and ran a very close race for mayor—that’s right, your daddy was almost mayor of New York City!—but he lost because people said he showed people his penis and that’s none of anybody’s business.

Let’s look at this from Huma’s perspective. She’s got a child for a husband, with a weird sexual addiction that on the positive side, doesn’t appear to carry the threat of STDs. But her dilemma is not about her marriage. The marriage is over. What she cares about is Jordan. And this is where she’s really fucked. Whatever happens, Anthony will always be her child’s father.

That bears repeating. You’ve got a child you love more than anything in the world, will sacrifice anything for, and will always now be stigmatized as the son of a celebrity-sized asshole. What are your choices?

The best scenario for Huma is if Anthony becomes mayor. Then she can divorce his ass, get primary custody and protect her child from growing up listening to penis jokes about his loser father. There will be jokes, but at least they’ll be about the mayor’s penis. And with a whole lot of luck, they might even be about how his father’s penis was a lot smaller in the mind of the public than his policies.

Weiner won’t get my vote, however. And for that, I apologize to you, Jordan. You have my sympathy, Huma.

Radhika Nagpal is a role model for fun people everywhere

Can I hear an amen for Radhika Nagpal, the brave woman who explained to the world recently how she lived through being a tenure-track professor at Harvard without losing her soul?

You should really read Nagpal’s guest blogpost from Scientific American (hat tip Ken Ribet) yourself, but here’s just a sneak preview, namely her check list of survival tactics that she describes in more detail later in the piece:

- I decided that this is a 7-year postdoc.

- I stopped taking advice.

- I created a “feelgood” email folder.

- I work fixed hours and in fixed amounts.

- I try to be the best “whole” person I can.

- I found real friends.

- I have fun “now”.

I really love this list, especially the “stop taking advice” part. I can’t tell you how much crap advice you get when you’re a tenure-track woman in a technical field. Nagpal was totally right to decide to ignore it, and I wish I’d taken her advice to ignore people’s advice, even though that sounds like a logical contradiction.

What I like the most about her list was her insistence on being a whole person and having fun – I have definitely had those rules since forever, and I didn’t have to make them explicit, I just thought of them as obvious, although maybe it was for me because my alternative was truly dark.

It’s just amazing how often people are willing to make themselves miserable and delay their lives when they’re going for something ambitious. For some reason, they argue, they’ll get there faster if they’re utterly submissive to the perceived expectations.

What bullshit! Why would anyone be more efficient at learning, at producing, or at creating when they’re sleep-deprived and oppressed? I don’t get it. I know this sounds like a matter of opinion but I’m super sure there’ll be some study coming out describing the cognitive bias which makes people believe this particular piece of baloney.

Here’s some advice: go get laid, people, or whatever it is that you really enjoy, and then have a really good night’s sleep, and you’ll feel much more creative in the morning. Hell, you might even think of something during the night – all my good ideas come to me when I’m asleep.

Even though her description of tenure-track life resonates with me, this problem, of individuals needlessly sacrificing their quality of life, isn’t confined to academia by any means. For example I certainly saw a lot of it at D.E. Shaw as well.

In fact I think it happens anywhere where there’s an intense environment of expectation, with some kind of incredibly slow-moving weeding process – academia has tenure, D.E. Shaw has “who gets to be a Managing Director”. People spend months or even years in near-paralysis wondering if their superiors think they’re measuring up. Gross!

Ultimately it happens to someone when they start believing in the system. Conversely the only way to avoid that kind of oppression is to live your life in denial of the system, which is what Nagpal achieved by insisting on thinking of her tenure-track job as having no particular goal.

Which didn’t mean she didn’t work hard and get her personal goals done, and I have tremendous respect for her work ethic and drive. I’m not suggesting that we all get high-powered positions and then start slacking. But we have to retain our humanity above all.

Bottomline, let’s perfect the art of ignoring the system when it’s oppressive, since it’s a useful survival tactic, and also intrinsically changes the system in a positive way by undermining it. Plus it’s way more fun.

MOOCs, their failure, and what is college for anyway?

Have you read this recent article in Slate about they canceled online courses at San Jose State University after more than half the students failed? The failure rate ranged from 56 to 76 percent for five basic undergrad classes with a student enrollment limit of 100 people.

Personally, I’m impressed that so many people passed them considering how light-weight the connection is in such course experiences. Maybe it’s because they weren’t free – they cost $150.

It all depends on what you were expecting, I guess. It begs the question of what college is for anyway.

I was talking to a business guy about the MOOC potential for disruption, and he mentioned that, as a Yale undergrad himself, he never learned a thing in classes, that in fact he skipped most of his classes to hang out with his buddies. He somehow thought MOOCs would be a fine replacement for that experience. However, when I asked him whether he still knew any of his buddies from college, he acknowledged that he does business with them all the time.

Personally, this confirms my theory that education is more about making connection than education per se, and although I learned a lot of math in college, I also made a friend who helped me get into grad school and even introduced me to my thesis advisor.

Proprietary credit score model now embedded in law

I’ve blogged before about how I find it outrageous that the credit scoring models are proprietary, considering the impact they have on so many lives.

The argument given for keeping them secret is that otherwise people would game the models, but that really doesn’t make sense.

After all, the models that the big banks have to deal with through regulation aren’t secret, and they game those models all the time. It’s one of the main functions of the banks, in fact, to figure out how to game the models. So either we don’t mind gaming or we don’t hold up our banks to the same standards as our citizens.

Plus, let’s say the models were open and people started gaming the credit score models – what would that look like? A bunch of people paying their electricity bill on time?

Let’s face it: the real reason the models are secret is that the companies who set them up make more money that way, pretending to have some kind of secret sauce. What they really have, of course, is a pretty simple model and access to an amazing network of up-to-date personal financial data, as well as lots of clients.

Their fear is that, if their model gets out, anyone could start a credit scoring agency, but actually it wouldn’t be so easy – if I wanted to do it, I’d have to get all that personal data on everyone. In fact, if I could get all that personal data on everyone, including the historical data, I could easily build a credit scoring model.

So anyhoo, it’s all about money, that and the fact that we’re living under the assumption that it’s appropriate for credit scoring companies to wield all this power over people’s lives, including their love lives.

It’s like we have a secondary system of secret laws where we don’t actually get to see the rules, nor do we get to point out mistakes or reasonably refute them. And if you’re thinking “free credit report,” let’s be clear that that only tells you what data goes in to the model, it doesn’t tell you how it’s used.

As it turns out, though, it’s now more than like a secondary system of laws – it’s become embedded in our actual laws. Somehow the proprietary credit scoring company Equifax is now explicitly part of our healthcare laws. From this New York Times article (hat tip Matt Stoller):

Federal officials said they would rely on Equifax — a company widely used by mortgage lenders, social service agencies and others — to verify income and employment and could extend the initial 12-month contract, bringing its potential value to $329.4 million over five years.

Contract documents show that Equifax must provide income information “in real time,” usually within a second of receiving a query from the federal government. Equifax says much of its information comes from data that is provided by employers and updated each payroll period.

Under the contract, Equifax can use sources like credit card applications but must develop a plan to indicate the accuracy of data and to reduce the risk of fraud.

Thanks Equifax, I guess we’ll just trust you on all of this.

If we bailed out the banks, why not Detroit? (#OWS)

I wrote a post yesterday to discuss the fact that, as we’ve seen in Detroit and as we’ll soon see across the country, the math isn’t working out on pensions. One of my commenters responded, saying I was falling for a “very right wing attack on defined benefit pensions.”

I think it’s a mistake to think like that. If people on the left refuse to discuss reality, then who owns reality? And moreover, who will act and towards what end?

Here’s what I anticipate: just as “bankruptcy” in the realm of airlines has come to mean “a short period wherein we toss our promises to retired workers and then come back to life as a company”, I’m afraid that Detroit may signal the emergence of a new legal device for cities to do the same thing, especially the tossing out of promises to retired workers part. A kind of coordinated bankruptcy if you will.

It comes down to the following questions. For whom do laws work? Who can trust that, when they enter a legal obligation, it will be honored?

From Trayvon Martin to the people who have been illegally foreclosed on, we’ve seen the answer to that.

And then we might ask, for whom are laws written or exceptions made? And the answer to that might well be for banks, in times of crisis of their own doing, and so they can get their bonuses.

I’m not a huge fan of the original bailouts, because it ignored the social and legal contracts in the opposite way, that failures should fail and people who are criminals should go to jail. It didn’t seem fair then, and it still doesn’t now, as JP Morgan posts record $6.4 billion profits in the same quarter that it’s trying to settle a $500 million market manipulation charge.

It’s all very well to rest our arguments on the sanctity of the contract, but if you look around the edges you’ll see whose contracts get ripped up because of fraudulent accounting, and whose bonuses get bigger.

And it brings up the following question: if we bailed out the banks, why not the people of Detroit?

Math fraud in pensions

I wrote a post three months ago talking about how we don’t need better models but we need to stop lying with our models. My first example was municipal debt and how various towns and cities are in deep debt partly because their accounting for future pension obligations allows them to be overly optimistic about their investments and underfund their pension pots.

This has never been more true than it is right now, and as this New York Times Dealbook article explains, was a major factor in Detroit’s bankruptcy filing this past week. But don’t make any mistake: even in places where they don’t end up declaring bankruptcy, something is going to shake out because of these broken models, and it isn’t going to be extra money for retired civil servants.

It all comes down to wanting to avoid putting required money away and hiring quants (in this case actuaries) to make that seem like it’s mathematically acceptable. It’s a form of mathematical control fraud. From the article:

When a lender calculates the value of a mortgage, or a trader sets the price of a bond, each looks at the payments scheduled in the future and translates them into today’s dollars, using a commonplace calculation called discounting. By extension, it might seem that an actuary calculating a city’s pension obligations would look at the scheduled future payments to retirees and discount them to today’s dollars.

But that is not what happens. To calculate a city’s pension liabilities, an actuary instead projects all the contributions the city will probably have to make to the pension fund over time. Many assumptions go into this projection, including an assumption that returns on the investments made by the pension fund will cover most of the plan’s costs. The greater the average annual investment returns, the less the city will presumably have to contribute. Pension plan trustees set the rate of return, usually between 7 percent and 8 percent.

In addition, actuaries “smooth” the numbers, to keep big swings in the financial markets from making the pension contributions gyrate year to year. These methods, actuarial watchdogs say, build a strong bias into the numbers. Not only can they make unsustainable pension plans look fine, they say, but they distort the all-important instructions actuaries give their clients every year on how much money to set aside to pay all benefits in the future.

One caveat: if the pensions have actually been making between 7 percent and 8 percent on their investments every year then all is perhaps well. But considering that they typically invest in bonds, not stocks – which is a good thing – we’re likely seeing much smaller returns than that, which means their yearly contributions to the local pension plans are in dire straits.

What’s super interesting about this article is that it goes into the action on the ground inside the Actuary community, since their reputations are at stake in this battle:

A few years ago, with the debate still raging and cities staggering through the recession, one top professional body, the Society of Actuaries, gathered expert opinion and realized that public pension plans had come to pose the single largest reputational risk to the profession. A Public Plans Reputational Risk Task Force was convened. It held some meetings, but last year, the matter was shifted to a new body, something called the Blue Ribbon Panel, which was composed not of actuaries but public policy figures from a number of disciplines. Panelists include Richard Ravitch, a former lieutenant governor of New York; Bradley Belt, a former executive director of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation; and Robert North, the actuary who shepherds New York City’s five big public pension plans.

I’m not sure what happened here, but it seems like a bunch of people in a profession, the actuaries, got worried that they were being used by politicians, and decided to investigate, but then that initiative got somehow replaced by a bunch of politicians. I’d love to talk to someone on the inside about this.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is back and, since her family has finally been reunited, sleeping well. Thank goodness! Hallelujah!

I’m psyched to be getting some great questions from the math community. If you’re a math nerd, and even if you’re not, please:

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’ve been thinking a lot about your remark from this previous post:

Like a lot of academics, he understands ambition in one narrow field, and doesn’t even relate to not wanting to be successful in this realm

That has really resonated with me. I am trying to make it as an academic, and I admit I am super boring because all I really care about is math and exercise, and I’m not really smart enough or care enough to have an informed opinion of much else.

Unfortunately this makes it hard to attract women, and the ones I have gone out on dates with said that I am not very engaging. On top of that most women want children, and I have read (and agree with) your post on why wanting children is ridiculous. I am also not located in a region where I have any colleagues or even graduate students working in my area of math to talk math with and so I feel pretty isolated in so many levels.

What does it take to become a math professor at an ivy league caliber institution (e.g. Harvard, MIT Columbia, Princeton)? Does one have to be working/thinking about math for much of one’s day? I presume you have an inside view.

Math is Titillating

Dear MiT,

First of all thanks for bringing up that previous answer. I have gotten a lot of people writing in saying I misinterpreted his description of taking extra time to finish his Ph.D.; most people generally think he only took one extra year whereas I read it as two extra years, which makes a big difference. Given this, I was probably too harsh on the guy, although I still think grad students should go to seminars.

As an aside, when did we start using “last year” to mean “this year” and “next year” to mean “next year” but stopped using “this year” to mean anything?

Now on to your question. Do you have to be thinking about math all the time to get a great job? Probably. There are exceptions but they’re rare, as you know.

Let’s face it, this wasn’t really a question for Aunt Pythia. I think you just identified with the description of being boring and only caring about getting a fancy math job, since that’s all you actually care about, as evidenced by your question.

But hey, I’m Aunt Pythia, so I’ve got advice for you anyway.

Don’t feel bad about it! It’s just how you’re programmed, it’s fine. You love math and not much else! Shout it loud from the rooftops and you might just find a girl nerd who’s psyched with your boring self. Just please don’t expect everyone else to be like you, especially your graduate students.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a math professor in a bit of an ethical quandary.

There is a researcher in my field who is widely known (by those in the field) to be a Certified Asshole (CA). He cuts down other people and their work, often in underhanded and awful ways. The people in question are often women (but not always) and often young (grad students or postdocs). He is a tenured full prof at a Very Good School, though, so those who don’t know him respect the position and his publication record. They consider him to be a Serious Person instead of the CA that he is.

In our recent round of hiring, I read the packet of a very talented graduating student who is applying for postdocs. This student has a few publications already including one very, very nice result. He is also a current collaborator of mine, and I know him a bit personally.

The letter in the student’s application from CA (another collaborator of the student) is underhanded and sabotaging. It says nothing outright negative, of course, but has key phrases like “promising teaching career at a liberal arts school” or somesuch. It also manages to be self-aggrandizing about CA himself rather than praising the grad student and his work.

This student did not get any offers this year, and I know he will be on the market again this year. I can’t help thinking that this letter is hurting his chances for a research postdoc. CA is not his advisor. While it would help to have a good letter from a person in a position such as CA’s, I don’t think this particular letter is helping him.

I can’t figure out an ethical way to help the student. I can’t come out and tell him what’s in the letter. I can’t really say anything even alluding to that. Is there anything I can do to help him?

Better yet, is there anything I can do to hurt CA even though I am in a more junior position at a less well-respected school?

Math is Awesome, People Suck

Dear MAPS,

What a rich question! There are so many issues here, I do believe we could start an entire blog addressing just this ethical quandary, worked out in its entirety.

First of all, I agree that there is an ethical quandary, mostly because you read the CA letter.

If you’d told your friend not to get a letter from the CA beforehand, because he’s a known shitty letter writer, I think that would have been fine and not unethical. But given that you didn’t, and that your friend got that letter, and that you read the letter, it would now seem like spying to go back and tell your friend to get a new letter in the next round. After all, if you’d read the letter and it was great, then you wouldn’t be telling your friend to go get a new letter writer.

As an aside, it doesn’t make sense to me that, during the hiring process, people read the folders of their current collaborators – doesn’t that seem ripe for this kind of conflict of interest?

Now just a few words on “shitty letter writers” before we go on to actual advice. There are different kinds of shitty letter writers, which I’ll split into two broad categories: the tough letter writer, who has consistently high standards and doesn’t wax poetic about anyone ever, and the narcissistic letter writer, who is inconsistent with their praise, sometimes cold sometimes hot, depending on idiosyncratic things like whether they like the young person’s personality and whether they’ve seen enough citations to the narcissist’s own work.

In the large and relatively functional system that is recommendation letters for math jobs, the tough letter writer is a pretty familiar concept, and the system has adapted more or less to its existence. In other words, people who read a lot of letters in a lot of folders get to know the letter writers and they say stuff to themselves along the lines of, oh this guy never writes good letters, so given that, this letter is actually pretty good!

Of course that’s not to say that it’s a perfect system of adaptation to such tough letter writing biases: for sure there are hiring committees unfamiliar with those letter writers, and for those students who have those tough letters, they inevitably suffer in such situations.

On the other hand, if you tried to explicitly adjust this problem, you could be inviting other, even bigger problems. For example, if you had a public yet anonymous webpage which scored every letter writer on a scale of toughness, then the young people looking for jobs might feel like to compete, they’d need to only get letters from people who always write good letters (they exist), and then the entire system would fail because the letters would contain less and less information. That would be a problem.

OK, what about the narcissist letter writer? That’s harder, since they’re not consistently tough, but rather they’re tough on people they just don’t like for whatever reason. It’s much much harder for people on hiring committees to spot the narcissists, and thus those narcissists probably do lots of damage. Luckily they’re also less common then the tough letter writers, but of course they exist.

I’d like to respond to your last question, about wanting to hurt CA, who I’m guessing is a narcissist letter writer, and even though the question is posed strangely.

I don’t think it’s unethical, when you’re counseling any person in your field from now on, to explicitly suggest not using that guy, or for that matter any narcissist letter writer. Of course, this is before you’ve read the putative letter, and of course the person might think you’re wrong and might ignore your advice (and of course, you might be wrong).

My advice to you about the person who didn’t get a job this year (note usage of “this year”): make sure they’re aware of how much letters count, and how different writers are known for different styles, and tell them to consider getting new letters. Ask them to explicitly ask their letter writers whether their letters are good, and define “good”, something I always counsel people to do when they ask for letters. I don’t think you can do much more than this.

But I’m eager to hear what Jason Starr thinks, he’s always very thoughtful!

Best,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

You write an amazing blog that

- lets your readership get to know you as a person and

- showcases your interests and expertise without

- too much compartmentalizing.

Help a sister out with some advice for how to achieve similar results?

Bridging Lives Online Gets Gnarly Yo

Dear BLOGGY,

My advice is to

- Set aside time every day to write. Consistency is your friend.

- Choose a (possibly imaginary) friend of yours each day to write to – your audience – that is on your side but will also ask clarifying questions, and explain something to them that you find interesting. That’s a blog post!

- Also, explain one idea well, then stop. People can barely stand one idea before losing interest.

Good luck, I know you’re gonna rock it!!!

Love,

Auntie P

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated ethical quandary to Aunt Pythia!

The Stop and Frisk sleight of hand

I’m finishing up an essay called “On Being a Data Skeptic” in which I catalog different standard mistakes people make with data – sometimes unintentionally, sometimes intentionally.

It occurred to me, as I wrote it, and as I read the various press conferences with departing mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly when they addressed the Stop and Frisk policy, that they are guilty of making one of these standard mistakes. Namely, they use a sleight of hand with respect to the evaluation metric of the policy.

Recall that an evaluation metric for a model is the way you decide whether the model works. So if you’re predicting whether someone would like a movie, you should go back and check whether your recommendations were good, and revise your model if not. It’s a crucial part of the model, and a poor choice for it can have dire consequences – you could end up optimizing to the wrong thing.

[Aside: as I’ve complained about before, the Value Added Model for teachers doesn’t have an evaluation method of record, which is a very bad sign indeed about the model. And that’s a Bloomberg brainchild as well.]

So what am I talking about?

Here’s the model: stopping and frisking suspicious-looking people in high-crime areas will improve the safety and well-being of the city as a whole.

Here’s Bloomberg/Kelly’s evaluation method: the death rate by murder has gone down in New York during the policy. However, that rate is highly variable and depends just as much on whether there’s a crack epidemic going on as anything else. Or maybe it’s improved medical care. Truth is people don’t really know. In any case ascribing credit for the plunging death rate to Stop and Frisk is a tenuous causal argument. Plus since Stop and Frisk events have decreased drastically recently, we haven’t seen the murder rate shoot up.

Here’s another possible evaluation method: trust in the police. And considering that 400,000 innocent black and Latino New Yorkers were stopped last year under this policy (here are more stats), versus less than 50,000 whites, and most of them were young men, it stands to reason that the average young minority male feels less trust towards police than the average young white male. In fact, this is an amazing statistic put together by the NYCLU from 2011:

The number of stops of young black men exceeded the entire city population of young black men (168,126 as compared to 158,406).

If I’m a black guy I have an expectation of getting stopped and frisked at least once per year. How does that make me trust cops?

Let’s choose an evaluation method closer to what we can actually control, and let’s optimize to it.

Update: a guest columnist fills in for David Brooks, hopefully not for the last time, and gives us his take on Kelly, Obama, and racial profiling.