Yves Smith and Dean Baker discuss the Trans Pacific Partnership #OWS

Last night I watched this interview by Yves Smith and Dean Baker on billmoyers.com. I recommend it for everyone interested in learning about the secret “free trade” agreement currently under negotiation between the U.S. and a bunch of other countries which touch the Pacific Ocean.

The interview will explain why “free trade” is in quotes, because it’s really more about protecting corporate interests and extending patents than about reducing obstacles to trade:

As a member of Alt Banking, I’m particularly outraged by the financial regulation part of the treaty, which sound like a race to the bottom in terms of common laws between the countries. But probably the worst part of the treaty is related to pharmaceutical protectionism.

Near the end of the interview there’s an appeal, involving a monetary award, for people on the inside to come out and show the world exactly what the contents of the treaty contain. The award is sponsored by WikiLeaks and is crowdsourced: it currently stands at $61,252. So you can add to it if you want to sweeten the pot.

How do we fix LIBOR?

It’s kind of hard to believe, but it’s true: many of the problems that led up to the financial crisis are still with us and simply haven’t been addressed.

For example:

- There are too few banks, and they are too interconnected. This is still a huge problem, and it’s called “Too Big To Fail.”

- In fact they’re so big they can engage in criminal activity and not fear prosecution. Still true, and it’s got a name too, “Too Big To Jail.”

- Also, the credit rating agencies, who get paid by debt issuers for AAA ratings on crappy debt? They’re still alive, there are still only three of them, and they still rate debt.

- Also, remember the LIBOR rate manipulations? Still being run by asking individual traders what they’ve been paying recently, and the answers are still being taken on faith. Oh, and they’ve been asked “not be located in close proximity to traders who primarily deal in derivative products” based on Libor. That’ll work, because nobody know how to text!

I’d like to perform a thought experiment for this last one, because it seems like a solvable problem, although I will confess up front that I don’t have a solution off the top of my head. That’s where you readers come in.

Just a little background. LIBOR is (supposedly) the very short-term interest rate that banks pay each other for loans. A huge pile – hundreds of trillions of dollars worth – of derivatives in the form of futures, swaps, and loans are tied to the LIBOR, and most of them seems to reference the three-month rate. Here’s a NY Times graphic explaining how it works and explaining how the fraud played out at Barclay’s.

So what are the attributes of the benchmark that make LIBOR so important and so widely used? And how would we start using something else instead?

Let’s answer that second question first. If we could find another 3-month benchmark rate with good properties, we could start writing contracts based on the new rate from now on, while continuing to compute LIBOR until the existing contracts have played out and LIBOR would be grandfathered out of the market.

Now on to the first question, a list critical attributes of this rate.

- It’s supposed to reflect very short-term kinds of risk, which means you don’t want to base it on, say, long term treasuries.

- It should be public data, so we don’t have manipulation behind the scenes

- But it shouldn’t be based on a market that is so small that it is worth losing money on that small market to manipulate the new LIBOR rates. Remember, the derivatives market that uses that rate is enormous, so if we base the rate on a smallish if transparent market, that would just invite market manipulation for that small market.

- The point of LIBOR-based derivatives is that it’s a floating rate, which means that as credit gets tighter or looser so does the rate references in a given derivative. But of course LIBOR is a very bank-specific kind of credit. So it’s not just “as credit gets tighter or looser” but rather “as interbank credit gets tighter or looser” (and here I’m ignoring the manipulation, since when bank credit actually got tighter, it wasn’t actually reflected in LIBOR rates).

- So I guess my question is, do we actually want bank-specific credit rates? Isn’t it good enough to have a market-wide concept of credit tightness? For most people who own one side of those LIBOR-based derivatives, I’m sure their own access to credit matters more to them than some London bank’s access, although I’m also sure there’s a relationship between the two.

I’m asking you readers to put up suggestions or explain how we can do without LIBOR altogether.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia lovers! Please rest assured that Aunt Pythia took a much-needed one week rest but is now back and is bigger and better than before!

What?! YES!!!

And please, don’t forget to ask me a question at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have been dating a guy for 6 months, and realized that I have been suffering due to his “too direct” way of communicating, a.k.a. criticizing me too much.

Everything is bad, he said my skin will look better if I exfoliate more, he said the shoes I wear looked too cheap on me, or that I should use different deodorant because the one I am using right now is “failing”, and the worse, he said I have bad breath.

I understand that I should not take criticism too personal, and it reminds me that I have many things to improve, but he made me feel horrible and I’m losing confidence.

I really want to break up with him because I don’t think he loves me, but he keeps on saying that he does, and despite all those critics, he stays in this relationship with me. What should I do?

I Am Sad

Dear Sad,

A few things.

First, what you’ve described is a classic case of someone (namely, a jerk) projecting their insecurities onto someone else (namely, you). He does it through accusations, and as a good friend explained to me, people accuse you of the thing they are guilty of. So next time he accuses you of having bad breath, realize it is he who is sensitive to his breath. So your first task is to flip those statements around every time they come out of his mouth.

Next, I know it’s easier said than done, but I want you to work on flipping more than just his words. I want you to start realizing that when you say “he stays in this relationship with me” it means that it’s up to him, whereas it’s really just as much up to you. In other words, you’ve given him all the power to decide whether this relationship is going to continue. You didn’t even tell me if you love him, only that he loves you (or at least claims to), which is another indication that you feel powerless and your emotions are irrelevant. So they second task I’d like you to try is to flip that mindset around and realize that, given how insecure and mean he is, he’s lucky you haven’t broken up with him. You have the power to end this, even if you haven’t exerted it yet.

Finally, I want you to address this stuff with him (if you do indeed love him – otherwise skip to last four words of this paragraph). Once you’ve learned to recognize his projections for insecure and mean barbs, and once you realize the power you have in that relationship, I’d like you to tell him that you have standards for a high quality of life, and this treatment is not meeting those standards, so he needs to stop. And if he can’t, then break up with him.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

If I drink quickly enough and pee slowly enough simultaneously, do you think I could pee forever?

Aspiring Guinness

Dear AG,

Dunno but please do document your efforts.

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How do you find the time to work as a data scientist, be a mom, write daily blog posts, organize Occupy/hacker events and still maintain a sense of humor? I’ve got one job, one hobby, no kids and can do little more than collapse on my day off. I don’t even have a TV.

What’s your secret? Are you one of those amazing people who only needs four hours of sleep per night?

More energy hopeful

Dear More,

I’ve been asked this question before and, although I will tell you my “secrets”, I’m guessing you are underplaying all the stuff you actually do. To convince yourself of that, think about how your best friend would describe you, not how you did above. Just sayin’. OK here goes.

First of all, I’m a huge sleep hog. I think that’s one of my secrets, which is that I don’t deny myself sleep. I often fall asleep before my kids, who are themselves sleep hogs and go to bed at 9:30 [Update: after reading this my oldest son insists that he is not a sleep hog and that the 9:30 bedtime is mandated by the dictator who is his mother]. I also take naps whenever I can. Love naps.

I generally think people shortchange their own sleep thinking it will make them more efficient, when in fact it does the opposite. A great night’s sleep sees me jumping out of bed at 6am to blog some point that got me all in a huff the day before. I can’t wait! I’m excited to do it!

The second thing I want to mention is that I’m a scrupulous planner, and I have enormously high (extremely personal) standards for my activities. I say “no” almost all the time to almost everything, so I can spend more time doing stuff I love like watching Star Trek: Deep Space 9 with my kids and taking naps. That means I’m a persona non grata when it comes to, say, the PTA, where my policy is that if my husband won’t do it, neither will I (and he basically won’t do anything).

Third, what with all the reinventing I’ve done over the years, I don’t hover needlessly over my own decisions. I write a blog post, then publish it. I give myself 1.5 times as long to prepare a talk as the talk will last, a trick I learned from my teaching experience. If things suck, I take it in stride, make a mental note to myself, and move on. In other words, I’m ruthlessly efficient and my skin is thick. It means I’m not a stickler for details but I get through more stuff than otherwise.

Finally, I really like and trust the people I meet and work with. It sometimes burns me but then again almost always works out, and I’d recommend it overall, especially if paired with a natural or learned resilience to disappointments, which gets easier when you have a fantastic support system. That means I’m always psyched to work on the next project with other people and that energy feeds me and gets me going.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dearest Aunt Pythia,

I’m a young math professor, and, as you know is typical, this career entails for me a certain level of travel to conferences. Lately, I’ve realized that the colleagues that I meet regularly at conferences are a sad bunch of life cripples. Totally lacking in beneficial social graces and unable to hold even just a slightly decent conversation of non-trivial length (especially one not involving mathematics), I feel continually shocked when around them, particularly by the unsubtle, autistic fashion in which they interrogate me about my personal life, professional activities, collaborations, etc.

Could you suggest any techniques for coping with interactions with them? How can I survive, or even have a little fun in this bad party I’m stuck in? Also, does Aunt Pythia have any ideas for minimizing the anxiety that I’m struck with prior to attending a conference?

Keep up the frank work,

Pitiable In The Suburbs

Dear Pitiable,

I’m afraid I’m going to have to use my previous advice against you. You are accusing these guys of all sorts of things that you yourself are guilty of. In particular, you don’t sound like someone overbrimming with social graces when you call people “cripples”.

And when I pair your nasty and dismissive tone with the acknowledged anxiety you experience before going to a conference, I am forced to conclude that you are projecting anxiety and insecurity onto these nerds.

Look, I’ve been to a LOT of conferences, and I agree that there are lots of awkward moments. And yes, there are lots of people that are on the autism spectrum in mathematics. But those people are still really wonderful in general and I have always found a way to enjoy myself with great company. In fact I cannot remember a conference I went to that I didn’t end up enjoying once I sought out the people with whom I click. Even at Oberwolfach, the most macho of all places, I managed to find some bridge partners and beer.

My advice to you: spend a lot of time willfully separating your anxiety from other people’s flaws, and set yourself the task to find something beautiful, or at least amusing, in every person you meet at your next conference. And take it from me, there are assholes in math, but they are typically pretty minor league compared to, say, the finance assholes or the Silicon Valley assholes.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

The private-data-for-services trade fallacy

I had a great time at Harvard Wednesday giving my talk (prezi here) about modeling challenges. The audience was fantastic and truly interdisciplinary, and they pushed back and challenged me in a great way. I’m glad I went and I’m glad Tess Wise invited me.

One issue that came up is something I want to talk about today, because I hear it all the time and it’s really starting to bug me.

Namely, the fallacy that people, especially young people, are “happy to give away their private data in order to get the services they love on the internet”. The actual quote came from the IBM guy on the congressional subcommittee panel on big data, which I blogged about here (point #7), but I’ve started to hear that reasoning more and more often from people who insist on side-stepping the issue of data privacy regulation.

Here’s the thing. It’s not that people don’t click “yes” on those privacy forms. They do click yes, and I acknowledge that. The real problem is that people generally have no clue what it is they’re trading.

In other words, this idea of a omniscient market participant with perfect information making a well-informed trade, which we’ve already seen is not the case in the actual market, is doubly or triply not the case when you think about young people giving away private data for the sake of a phone app.

Just to be clear about what these market participants don’t know, I’ll make a short list:

- They probably don’t know that their data is aggregated, bought, and sold by Acxiom, which they’ve probably never heard of.

- They probably don’t know that Facebook and other social media companies sell stuff about them even if their friends don’t see it and even though it’s often “de-identified”. Think about this next time you sign up for a service like “Bang With Friends,” which works through Facebook.

- They probably don’t know how good algorithms are getting at identifying de-identified information.

- They probably don’t know how this kind of information is used by companies to profile users who ask for credit or try to get a job.

Conclusion: people are ignorant of what they’re giving away to play Candy Crush Saga[1]. And whatever it is they’re giving away, it’s something way far in the future that they’re not worried about right now. In any case it’s not a fair trade by any means, and we should stop referring to it as such.

What is it instead? I’d say it’s a trick. A trick which plays on our own impulses and short-sightedness and possibly even a kind of addiction to shiny toys in the form of candy. If you give me your future, I’ll give you a shiny toy to play with right now. People who click “yes” are not signaling that they’ve thought deeply about the consequences of giving their data away, and they are certainly not making the definitive political statement that we don’t need privacy regulation.

1. I actually don’t know the data privacy rules for Candy Crush and can’t seem to find them, for example here. Please tell me if you know what they are.

Harvard Applied Statistics workshop today

I’m on an Amtrak train to Boston today to give a talk in the Applied Statistics workshop at Harvard, which is run out of the Harvard Institute for Quantiative Social Science. I was kindly invited by Tess Wise, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Government at Harvard who is organizing this workshop.

My title is “Data Skepticism in Industry” but as I wrote the talk (link to my prezi here) it transformed a bit and now it’s more about the problems not only for data professionals inside industry but for the public as well. So I talk about creepy models and how there are multiple longterm feedback loops having a degrading effect on culture and democracy in the name of short-term profits.

Since we’re on the subject of creepy, my train reading this morning is this book entitled “Murdoch’s Politics,” which talks about how Rupert Murdoch lives by design in the center of all things creepy.

Rubik’s cubes and Selmer groups

One of my biggest regrets when I left academic math and number theory behind in 2007 was that I never finished writing up and publishing some cool results I’d been working on with Manjul Bhargava about what we called “3x3x3 Rubik’s cubes”.

Just a teeny bit of background. Say you have a 3x3x3 matrix filled with numbers, including in the very center. So you have 27 numbers in a special 3-dimension configuration. Since there are three axis for such a cube, there are three ways of dividing such a cube into three 3×3 matrices and

Once you do that you can get a cubic form by computing

which gives you a cubic equation in three variables, or in other words a genus one curve.

Actually you get three different genus one curves, since you do it along any axis. Turns out there are crazy interesting relationships between those curves, as well as in the space of all 3x3x3 cubes.

Just talking about that stuff gets me excited, because it’s first of all a really natural construction, second of all number theoretic, and third of all it actually makes me think of solving Rubik’s cubes, which I’ve always loved.

Anyhoo, I gave my notes to a grad student Wei Ho when I left math, and she and Manjul recently came out with this preprint entitled “Coregular Spaces and genus one curves”, which is posted on the mathematical arXiv.

First, what’s freaking cool about their paper, to me personally, is that my work with Manjul has been incorporated into the paper in the form of parts of sections 3.2 and 5.1.

But what’s even more incredibly cool, to the mathematical world, is that Wei and Manjul are going to use this paper as background to understand the average size of Selmer groups of elliptic curves, a really fantastic result. Here’s the full abstract of their paper:

A coregular space is a representation of an algebraic group for which the ring of polynomial invariants is free. In this paper, we show that the orbits of many coregular irreducible representations where the number of invariants is at least two, over a (not necessarily algebraically closed) field k, correspond to genus one curves over k together with line bundles, vector bundles, and/or points on their Jacobians. In forthcoming work, we use these orbit parametrizations to determine the average sizes of Selmer groups for various families of elliptic curves.

One last thing. I am lucky enough to be a neighbor of Wei right now, as she finishes up a post-doc at Columbia, and she’s agreed to explain this stuff to me in the coming weeks. Hopefully I will remember enough number theory to understand her!

Someone explain to me how accountants think about Capital Appreciation Bonds (#OWS)

Book Club

Yesterday we had a great discussion in our Alternative Banking Book Club about municipal financing, based on the sixth chapter in our book Occupy Finance called A Civics Lesson: Wall Street Feasts on the Commons. The conversation was kindly led by Tom Sgouros, a policy analyst and author from Rhode Island, which seems to be a hotbed of super terrible muni financing.

It was explained that shady deals in muni finance is all over the map, from price fixing in municipal bond deals, which is corruption strictly on the side of the big banks who finance the town’s deals to accounting tricks, where it takes the collusion of town officials to enter into shady and inappropriate contracts.

The thing I’d never really understood until yesterday was how people used Capital Appreciation Bonds to play tricks with their accounting, and specifically with their town’s debt limits.

Context around muni financing

A little more context, although I’m no expert (experts, please add details or correct me if I’ve misrepresented anything). Please also read the chapter, which is excellent and much broader.

First of all, by “municipalities” we mean towns and cities (actually, states and counties, too, not to mention water authorities, economic development agencies, school departments, and all the rest of the “not-federal-not-corporate”). So a town needs to borrow money for something, maybe to pay its workers, maybe to build something or maintain its roads. It borrows money from investors by issuing a muni bond, and the big banks help set that up. Investors invest in these bonds because they have special tax treatment, because they rarely default, and because they want to support their local communities.

But as you can imagine, the big banks have much more expertise on what kind of prices to expect and the level of sophistication it requires to do due diligence, and then if you add into that mix the fact that local town officials are often temporary, ignorant, and desperate, we get a toxic environment. There are lots of examples of this problem, and often they are covered up by the local towns because of associated embarrassment, complicity, and shame. Seriously, it’s awful, and we only hear about some of them like in Detroit and Stockton, when things are incredibly awful. Matt Taibbi has done an amazing job chronicling this stuff.

Anyhoo, with that backdrop, you can imagine that there are bad situations handed to town officials when they enter office, and they are confronted with a major league problem: they need to come up with money now to pay something basic like school teachers or firemen, but there’s no cash. And plus there’s a debt limit which they’re already pushing up against.

Zero coupon

Enter the Capital Appreciation Bond (CAB). It’s a zero-coupon bond, which is already weird. For most muni bonds, towns regularly – quarterly or annually – pay interest or so-called amortizing sums, very much as an individual homeowner might pay monthly for their mortgages, where most of it goes to interest but every month a little bit of the principal is paid off too.

But for CABs, you get some money now and you pay nothing at all until it’s due, at which point you pay it all back at once.

Very very long term debt

You may have even forgotten about it by then, though, because the second weird thing about CABs is that the loans are often very very long term – as in 30 or 40 years. So, given the nature of the set-up and the nature of compound interest, you can end up paying something like 7 times the original amount after that much time.

For example, we see a school district like San Mateo in California borrowing $190 million recently that, when the bond comes due, will owe $1 billion. And it’s widespread in California: according to this article, 200 California school and community college districts issuing these bonds will end up paying 10 to 20 times more than they borrowed.

Accounting practices and CABs

That brings me to the third weirdest property of CABs, namely how they look on balance sheets for accounting purposes.

Namely, and here I need to confess that I’ve been a very bad accounting student, the towns only have to write the original loan down on the balance sheet as a liability, not the eventual pay-out. This is in contrast with other kinds of very similar zero-coupon bonds where you have to write down the eventual payment you will owe, not the amount you start with.

Someone please explain this discrepancy in the field of accounting!! It makes no sense to me. If the cash flows are the same for two different kinds of bonds, how do you get to account for them differently?

Conclusion

In any case, the consequences of this accounting trick are real. In particular it means that, for desperate town officials trying to pay their workers, or even shady town officials trying to get away with stuff, CABs are very attractive indeed, because it looks kind of innocuous and their overall debt limits don’t get breached even though they’ve essentially sold the future of the town to a big Wall Street bank. Plus they won’t be in office when that bill comes due, and they might well be dead.

Some California officials are trying to make CABs illegal or at least restricted, and some states like Michigan and Ohio have already passed laws against them. But given how much money they make for big banks, there are serious headwinds for reasonable rules.

It’s a good day to join a revolution #OWS

I’m too angry today to dole out advice.

Instead I think I’ll join a revolution. This one, that Russell Brand is talking about.

The multiple arms races of the college system

I’m reading a fine book called Nobody Makes You Shop at Walmart, which dispels many of the myths surrounding market populism, otherwise described in the book as “MarketThink”, namely the rhetoric which “portrays the world (governments aside) as if it works like an ideal competitive market, even when proposing actions that contradict that portrayal,” according to the author Tom Slee.

I’ve gotten a lot out of this book, and I suggest that you guys read it, especially if you are libertarians, so we can argue about it afterwards.

One thing Slee does is distinguish between different kinds of competitive and power-dynamic systems, and fingers certain situations as “arms races”, in which there are escalating costs but no long-lasting added value for the participants. They often involve relative rankings.

Slee’s example is a neighborhood block where all the men on the block compete to have the nicest cars. Each household spends a bunch of money to rise in the rankings just to have others respond by spending money too, and at the end of a year they’ve all spent money and none of the rankings have actually changed.

One of Slee’s overall points about arms races is that the way to deal with them is through armament agreements, which everyone involved needs to sign onto. Later in the book he also talks about how hard it is to get large groups of people to agree to anything at all, especially vague social contracts, when there’s an advantage to cheating, something he calls “free riding.” (as a commenter pointed out to me, free riding is more like someone who gets something for nothing, like a worker who benefits from the work of a union without being in the union and paying dues. This is just cheating.)

I’d argue, and I believe the book even uses this example, that education can be seen as an arms race as well. Take the statistics in this Opinionator blog from the New York Times, written by Jonathan Cowan and Jim Kessler, and entitled “The Middle Class Gets Wise.”

It describes how much more money the average high school graduate, versus two-year college, versus four-year college, versus professional degree graduate makes. In other words, it describes the payoffs to being higher ranked in that system. The money is real, of course, and everyone is aware of it as an issue even if they don’t know the exact numbers, so it is very analogous to the car status thing.

Cowan and Kessler describe in their article how, in the face of recession, lots more people have gone to college. That makes sense, since many of them didn’t have jobs and wanted to make themselves employable in the future, and at the same time people knew the job climate was even more rank-oriented since it has become tighter. People responded, in other words, to the incentives.

There’s a feedback loop going on in colleges as well, of course, and paired with the federal loan program and the fact that students cannot get rid of student debt in bankruptcy, we’ve seen a predictable (in direction if not size) and dramatic increase in tuition and student debt load for the younger generation.

My reaction to this is: we need an armament agreement, but it’s really not clear how that’s going to all of a sudden appear or how it would work, considering the number of entities involved, and the free rider problems due to the cash money incentives everywhere.

From the point of view of employers, rankings are great and they can be sure to pick the highest ranked individuals from that system, even if that means – as it often does – having Ph.D. graduates working in mailrooms. So don’t expect any help from them to add sanity to this system.

From the point of view of the colleges, they’re getting to hire more and more administrators, which means growth, which they love.

Finally, from the point of view of the individual student, it makes sense to go into debt, with almost no limit (to a point, but people rarely do that calculation explicitly, and if they did there’d be intense bias) to get significantly higher in the ranking.

In other words, it’s a shitshow, and possibly the only real disruption that could improve it would be widespread and universally respected basic and free-ish education. At least that would solve some of the arms race problems, for employers and for students. It would not make colleges happy.

The authors of the Opinionator piece, Cowan and Kessler, don’t agree with me. They have a goal, which is for even more people to go to school, and for tuition to be somehow magically decreased as well. In other words, up the antes for one feedback loop and hope its partner feedback loop somehow relaxes. Here’s the way they describe it:

So what can we do? Anya Kamenetz, the author of “Generation Debt,” has put together some excellent ideas for Third Way, the centrist policy organization where we both work. Let’s start by reducing the number of college administrators per 100 students, which jumped by 40 percent between 1993 and 2007. We should demand a cease-fire to the perk wars in which colleges build ever-more-luxurious living, dining and recreational facilities. Blended learning, which uses online teaching tools together with professors and teaching assistants, could also help students master coursework at less cost.

There are 37 million Americans with some college experience, but no degree. So pegging government tuition aid to college graduation rates would entice schools to find ways of keeping students in class. And eliminating some of the offerings of rarely chosen majors could bring some market efficiencies now lacking in education.

That really just doesn’t seem like a viable plan to me, and pegging government money to graduation rates is really stupid, as I described here, but maybe I’m just being negative. Cowan and Kessler, please tell me how that “demand” is going to work in practice.

Also, what’s funny about their idealistic demand is that they also think of a couple other things to do but dismiss them as unrealistic:

The most commonly discussed solutions to the problem of income inequality seem unlikely to get to the heart of the problem. Yes, we could raise additional taxes on the wealthy, but we just did that. Bumping up the minimum wage would help, but how high would lawmakers allow it to go? We should look instead at what Americans are already doing to solve this problem and help them do it far more successfully and at less cost.

Am I the only one who thinks raising the minimum wage would help more to address income inequality and is easier to imagine working?

Occupy for a Fair and Living Wage #OWS

I wanted to mention an important action that’s happening today at 5:00pm in Herald Square (34th Street and 6th Avenue) in case you are nearby and can join us.

The action is focused on raising the minimum wage. It was planned by OccuEvolve in conjunction with other Occupy groups, including Alternative Banking which made a bunch of signs this past weekend, in solidarity with the 75th Anniversary of the passing of the minimum wage law. The idea is to demand raising the minimum wage to at least 15 dollars a hour.

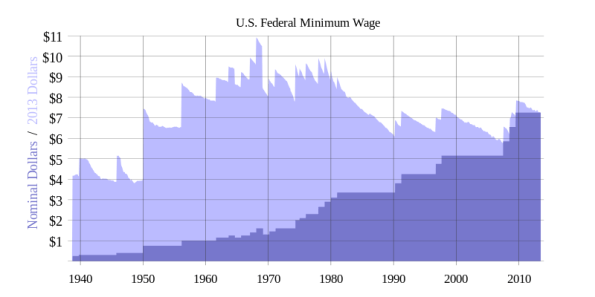

For a little context, here’s a chart showing the history of the U.S. Federal minimum wage since it began:

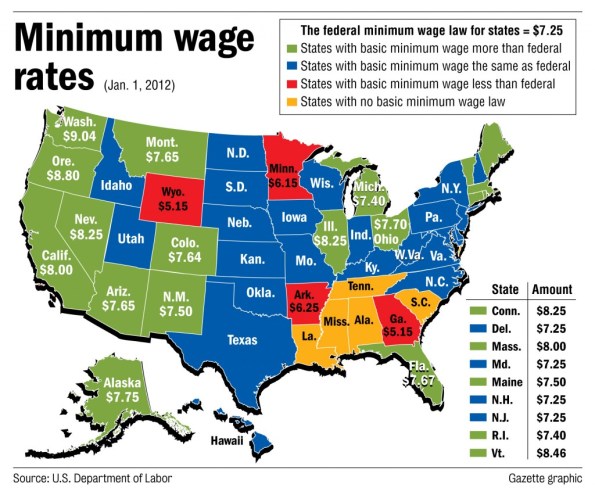

Many states have their own minimum wage laws that are either higher of lower than the federal law, and some cities have even more local minimum wages as well. Since federal law supersedes state law, I’m going to assume these guys are just behind recent increases in federal rates. Here’s a picture of the state-by-state minimum wage landscape:

I’ve never done the math on how it would be even close to possible to live on an hourly wage of $7.25 but it’s clearly not possible to, say, budget for emergencies even in the most frugal of approaches.

That general fact is embedded in this Bloomberg Businessweek article which argues that Walmart is subsidized by taxpayers and is a drag on growth. The article refers to a report put out by the Democratic staff of the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce entitled The Low-Wage Drag on Our Economy: Wal-Mart’s low wages and their effect on taxpayers and economic growth. It contains this excerpt:

While employers like Wal-Mart seek to reap significant profits through the depression of labor costs, the social costs of this low-wage strategy are externalized. Low wages not only harm workers and their families—they cost taxpayers.

Here’s a graphic showing which big employers are the worst culprits:

Let’s demand better tonight at 5:00pm in Herald Square.

The scienciness of economics

A few of you may have read this recent New York TImes op-ed (hat tip Suresh Naidu) by economist Raj Chetty entitled “Yes, Economics is a Science.” In it he defends the scienciness of economics by comparing it to the field of epidemiology. Let’s focus on these three sentences in his essay, which for me are his key points:

I’m troubled by the sense among skeptics that disagreements about the answers to certain questions suggest that economics is a confused discipline, a fake science whose findings cannot be a useful basis for making policy decisions.

That view is unfair and uninformed. It makes demands on economics that are not made of other empirical disciplines, like medicine, and it ignores an emerging body of work, building on the scientific approach of last week’s winners, that is transforming economics into a field firmly grounded in fact.

Chetty is conflating two issues in his first sentence. The first is whether economics can be approached as a science, and the second is whether, if you are an honest scientist, you push as hard as you can to implement your “results” as public policy. Because that second issue is politics, not science, and that’s where people like myself get really pissed at economists, when they treat their estimates as facts with no uncertainty.

In other words, I’d have no problem with economists if they behaved like the people in the following completely made-up story based on the infamous Reinhart-Rogoff paper with the infamous excel mistake.

Two guys tried to figure what public policy causes GDP growth by using historical data. They collected their data and did some analysis, and they later released both the spreadsheet and the data by posting them on their Harvard webpages. They also ran the numbers a few times with slightly different countries and slightly different weighting schemes and explained in their write-up that got different answers depending on the initial conditions, so therefore they couldn’t conclude much at all, because the error bars are just so big. Oh well.

You see how that works? It’s called science, and it’s not what economists are known to do. It’s what we all wish they’d do though. Instead we have economists who basically get paid to write papers pushing for certain policies.

Next, let’s talk about Chetty’s comparison of economics with medicine. It’s kind of amazing that he’d do this considering how discredited epidemiology is at this point, and how truly unscientific it’s been found to be, for essentially exactly the same reasons as above – initial conditions, even just changing which standard database you use for your tests, switch the sign of most of the results in medicine. I wrote this up here based on a lecture by David Madigan, but there’s also a chapter in my new book with Rachel Schutt based on this issue.

To briefly summarize, Madigan and his colleagues reproduce a bunch of epidemiological studies and come out with incredible depressing “sensitivity” results. Namely, that the majority of “statistically significant findings” change sign depending on seemingly trivial initial condition changes that the authors of the original studies often didn’t even explain.

So in other words, Chetty defends economics as “just as much science” as epidemiology, which I would claim is in the category “not at all a science.” In the end I guess I’d have to agree with him, but not in a good way.

Finally, let’s be clear: it’s a good thing that economists are striving to be scientists, when they are. And it’s of course a lot easier to do science in microeconomic settings where the data is plentiful than it is to answer big, macro-economic questions where we only have a few examples.

Even so, it’s still a good thing that economists are asking the hard questions, even when they can’t answer them, like what causes recessions and what determines growth. It’s just crucial to remember that actual scientists are skeptical, even of their own work, and don’t pretend to have error bars small enough to make high-impact policy decisions based on their fragile results.

Disorderly Conduct with Alexis and Jesse #OWS

Podcast

So there’s a new podcast called Disorderly Conduct which “explores finance without a permit” and is hosted by Alexis Goldstein, whom I met through her work on Occupy the SEC, and Jesse Myerson, and activist and a writer.

I was recently a very brief guest on their “In the Weeds” feature, where I was asked to answer the question, “What is the single best way to rein in the power of Wall Street?” in three minutes. The answers given by:

- me,

- The Other 98% organizer Nicole Carty (@nacarty),

- Salon.com contributing writer David Dayen (@ddayen),

- Americans for Financial Reform Policy Director Marcus Stanley (@MarcusMStanley), and

- Marxist militant José Martín (@sabokitty)

can be found here or you can download the episode here.

Occupy Finance video series

We’ve been having our Occupy Finance book club meetings every Sunday, and although our group has decided not to record them, a friend of our group and a videographer in her own right, Donatella Barbarella, has started to interview the authors and post them on YouTube. The first few interviews have made their way to the interwebs:

- Linda talking about Chapter 1: Financialization and the 99%.

- Me talking about Chapter 2: the Bailout

- Tamir talking about Chapter 3: How banks work

Doing Data Science now out!

O’Reilly is releasing the book today. I can’t wait to see a hard copy!! And when I say “hard copy,” keep in mind that all of O’Reilly’s books are soft cover.

Occupy the SEC, Dodd-Frank, and who has standing in financial regulation #OWS

A bit more than a week ago Akshat Tewery came to my Occupy group to discuss his chapter in the book we wrote called Occupy Finance [1].

Akshat is a member of Occupy the SEC [2] and came to talk to us about a short history of financial regulation, and how impressively well things worked in the middle of the last century, when Glass-Steagall was in effect and before it was gamed.

One thing he mentioned in his fascinating hour-long lecture was this lawsuit which I hadn’t heard about. Namely, Occupy the SEC sued the Federal Reserve, SEC, CFTC, OCC, FDIC and U.S. Treasury over not doing their jobs, specifically for the delay in finishing and implementing the Volcker Rule.

You see, Dodd-Frank is a law, and the Volcker Rule, which is supposed to be something like a modern Glass-Steagall act, is part of it. But the law just outlines the rules, and the regulators are supposed to actually turn that law into regulations which they then implement.

There was a deadline for that, and it has passed. So Occupy the SEC sued to make those guys get the job done.

And guess what? The judge found that they didn’t have standing to sue. I’m no lawyer but from what I can understand this means they were deemed not sufficiently relevant to the implementation of Dodd-Frank. They didn’t have enough skin in the game, in other words. Because they’re just, you know, citizens who care about having a functional regulatory environment. Not to mention taxpayers who have bailed out the banks and want to avoid continuing doing that.

That begs the question, who has skin in the regulation game? Answer: banks being regulated. So only those guys can complain to the courts about the regulation. And obviously their complaints will be different from Occupy the SEC’s complaints.

It seems like whenever I look around I see examples like this, where there are people getting away with crappy policies or even crappier deeds because it has a negative effect, but that negative effect is so dispersed that most people don’t have enough “standing” to sue or to even effectively quantify how they’ve been affected.

And I guess this is the land of class-action lawsuits, but that doesn’t seem sufficient. It really seems like there needs to be legal representation for taxpayers somehow. Who is looking out for the average non-insider? Who is keeping tabs on overall systemic risk? In an ideal world that would exist inside the regulators themselves, but we all know it’s not that ideal.

1. We’re out of copies, but if you don’t have a copy of Occupy Finance but you want one, go to our IndieGogo campaign and donate $10 and you’ll get a copy of the book as a thank you.

2. Which, if you don’t know, consists of an amazing and wonky group of occupiers who write public commenting letters on financial regulation. Their Volcker Rule comments have made quite an impression on regulators, but they’ve also written numerous amicus briefs on various issues as well. Keep an eye on their work on their webpage.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia has a 5-year-old’s birthday party to manage this morning, so she’s going to be more to the point, less philosophical, and overall slightly less fun and sexy than usual, for which she apologizes.

On second thought, they say less is more, so let’s assume it’s just as sexy if not more sexy.

Apology rescinded.

And, please, Aunt Pythia readers: I’ve been plowing through questions faster than I’ve been receiving them, so please

ask me a question at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Seeing as Halloween is coming up soon, I was just thinking about what to dress up as (well, looking online at pictures of other people’s ridonculous costumes). In the middle of my search, my brother walked into the room. Thinking that he may be of some help, I asked him what I should dress up as. He answered that I should just go as myself; it’ll be the scariest costume guaranteed.

How should I respond?

Sad Face Pumpkin

Dear SFP,

I think your brother is right, and you should acknowledge that.

Let’s face it, our society is filled with phonies getting up every morning and putting on costumes for work to hide their true inner selves. Being an authentic human being is incredibly intimidating to such people, and they might be terrified when they see you.

Partly this is because it’s just so incredibly rare to see someone be an unqualified human being that the “unknown” aspect is scary, and partly because they’re worried that, if you’re doing it, then they might be expected to do it too. Persevere though, and be brave. It’s worthwhile in spite of such reactions.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Since I had my first baby (a four month old little boy), my mother has starting buying him gifts frequently. Most of these are completely unnecessary, or superfluous, or more expensive than what we need or I would consider affordable.

I don’t want them and it stresses me out because I don’t think my mother can afford them either. She is completely innumerate. In fact, she doesn’t even seem to comprehend large numbers at all. 100 and 1000 and 10000 all mean the same thing to her.

Instead of budgeting with numbers, she tries to balance out a sense of deprivation (so she’ll try to balance out spending $100 on luxuries by buying cheap bread that tastes bad for a month, even though that doesn’t work at all).

Even though she is in her sixties, she constantly has a credit card debt, has kept the same mortgage for the last twenty years, and has minimal retirement savings. I wish she would stop buying us baby clothes from expensive department stores and save it instead. I’ve tried returning them and giving her the money back, and asking her not to buy any more, but often I can only get store credit. In any case she won’t take the money back, and then a few weeks later she’ll come over with a new set of clothes that are already almost too small for him.

Sometimes I lie awake at night stressing about it. I feel powerless to stop her but when she gets too old to work I think it will become my problem as well and I unfortunately don’t earn very much money. What should I do?

Anxious

Dear Anxious,

It’s a huge problem, and your mom is obviously not the only person in that situation. In fact I expect to hear more and more about retirees in huge debt problems in the next few years. Of course some retirees have saved a bunch of money, but not all of them to be sure.

My advice, and this is just on first reflection and I’d invite other readers to give their input, is to stay far away from your mom’s money, legally speaking. She is likely not going to accept your advice, and although it’s probably worth suggesting she go to talk to a non-profit community finance class on budgeting like at a local credit union, I don’t expect this will actually make her instantaneously frugal.

Here’s what I wouldn’t do if I were you: pay off her debts. There would just be more where those came from. When she is unable to pay her debts, by all means help her connect with a lawyer to declare bankruptcy, and help her cope with debt collectors (read the Debt Resistors Operations Manual to learn more about her rights and theirs).

Here’s another thing I wouldn’t do: in any way shape or form become a co-signatory on anything with her. Then you will be liable for her debts.

In the best of worlds, your mom will run up pretty big debts, the credit card companies will figure out she’s never going to pay back those debts, she will declare bankruptcy, and then nobody will give her any more credit. To be sure you will want to make sure she always has food and a place to live and medicine, but think of that as a separate issue from her piling-up debts, which is in the end the problem of the banks that gave her credit cards she couldn’t be trusted with.

Good luck, and enjoy motherhood!

Aunt Pythia

——

Hi Auntie P,

Thank you for answering my “sock” question, but my apologies for not phrasing it properly, and so misleading you as to my intention. Perhaps you will permit me to resubmit it, and – having seen your “not enough sex” comment on 21st – I will try to put some of that into it, instead of boring old socks.

Let’s imagine that 44 men and 116 women sign up for a dating evening. Each is given a number, and they are drawn at random – the organizer forgetting to ask any basic questions like “sexual orientation?” or to put the men’s numbers in one pot and the women’s in another. As the numbers are drawn out, the first person is paired with the second, the third with the fourth, etc.

So my question is this: how many M/M pairings will there be? Alternatively, what are the chances of getting exactly n such couples?

Socks Maniac

Dear Socks Maniac,

I don’t usually do this, but I’m gonna steal a commenter’s answer whole hog from that post, which I guess you didn’t see. This is from Michael Kleber, whom I’ve know approximately 20 years, and I’ve adjusted it to be sexy like I know we want it:

I think Socks Maniac’s drawer contains lots of individual

sockspeople which get paired up blindfolded. That gives you Xall-blackmale pairs, Yall-whitefemale pairs, and Z mixedblack-whitemale-female ones, and the question is the probability that X is exactly 10.This can also be answered by counting, but it’s a little uglier. There are 160-choose-44 orders in which you can pull the

socks out of the drawerblindfolded people out of the dungeon, of course. To count the number of ways to get exactly X/Y/Zblack/white/male/female/mixed pairs, you can think of lining up 80slotsdungeon lairs and picking X of them to get twoblack socksblindfolded men, Y of the remaining 80-X to get twowhite onesblindfolded women — and then for the remaining Zslotsdungeon lairs you need to pick whether ablack or a white sockman or woman was pulled out first, so that’s another 2^Z choices to worry about. So 80-choose-X * (80-X)-choose-Y * 2^Z.Since Socks Maniac told us X=10, that accounts for 20 of the 44

black socksblindfolded men, leaving 24black socksblindfolded men paired with 24white onesblindfolded women (so Z=24), and the other 92white socksblindfolded women paired up into Y=46all-whitewomen-on-women pairs. So the number of ways to get exactly 10 all-blackmale pairs is (80 choose 10) * (70 choose 46) * 2^24. Dividing by the 160-choose-44 to pull socks out of the drawer in the first place, and Wolfram Alpha says you get around 0.01854, or a little under a 2% chance.Hmm, I see I can’t post links, or even mention the Wolfram Alpha web site by name, without sounding like spam. But anyway, it will happily evaluate

((80 choose 10) * (70 choose 46) * 2^24) / (160 choose 44).

Thanks, Michael!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

From reading your blog/column, you sound like an outgoing, extroverted type. So maybe you can give a few pointers to we introverts: what are some good ways to start conversations with strangers? I tend to do OK once I’m actually talking to somebody, but I always feel awkward when trying to initiate contact with other people.

I’m single and I don’t have a ton of friends, so this seems like a useful skill to develop.

I’m Nervous To Join

Dear INTJ,

I think the key is to project a friendliness and openness to the stranger you are talking to, and if it turns out you’re wrong and the person is unfriendly or closed off, then not taking it personally.

So for example, when I see people knitting awesome stuff on the subway, I am pretty much always going to pipe up and tell them how beautiful that piece is. About 65% of the time this leads to an excited conversation about how awesome and useless knitting skills are, and sometimes even leads to the discovery of a new yarn shop or sale or website for one of us. But the rest of the time the person has no interest in talking, and I just walk away. I don’t feel bad for being friendly and wanting to connect with someone, because that is frankly what humans do and it’s not something to be ashamed of.

Note one thing: there was a “reason” for me to talk in the above scenario, and that’s key. It doesn’t make sense to walk up to someone with absolutely no cause and strike up a conversation. Having said that, the reason doesn’t have to be all that good, especially if there’s alcohol involved. It could be as simple as, “I love your shirt!!”, although that’s an opener for truly extroverted people.

One last thing. The more confident you are that most people are friendly and open, the higher your chances are of making a connection, so that leaves you with a bit of a tough feedback loop to get into. I suggest having an extroverted wingwoman or wingman the first few times to show you some ropes and to demonstrate how fun it is to be friendly. And good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

*Doing Data Science* now available on Kindle!

My book with Rachel Schutt is now available on Kindle. I’ve tested this by buying it myself from amazon.com and looking at it on my computer’s so-called cloud reader.

Here’s the good news. It is actually possible to do this, and it’s satisfying to see!

Here’s the bad news. The kindle reader doesn’t render latex well, or for that matter many of the various fonts we use for various reasons. The result is a pretty comical display of formatting inconsistency. In particular, whenever a formula comes up it might seem like we’re

screaming about it

and often the quoted passages come in

very very tiny indeed.

I hope it’s readable. If you prefer less comical formatting, the hard copy edition is coming out on October 22nd, next Tuesday.

Next, a word about the book’s ranking. Amazon has this very generous way of funneling down into categories sufficiently so that the ranking of a given book looks really high. So right now I can see this on the book’s page:

- #1 in Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Computers & Technology > Software

but for a while, before yesterday, it took a few more iterations of digging to get to single digits, so it was more like:

- #1 in Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Computers & Technology > Software > New Yorkers > Women nerd authors > one of whom is an occupier > & the other one grew up in New Jersey

But you, know, I’ll take what I can get to be #1! It’s all about metrics!!!

One last thing, which is that the full title is now “Doing Data Science: Straight Talk from the Frontline” and for the record, I wanted the full title to be something more like “Doing Data Science: the no bullshit approach” but for some reason I was overruled. Whatevs.

The case against algebra II

There’s an interesting debate described in this essay, Wrong Answer: the case against Algebra II, by Nicholson Baker (hat tip Nicholas Evangelos) around the requirement of algebra II to go to college. I’ll do my best to summarize the positions briefly. I’m making some of the pro-side up since it wasn’t well-articulated in the article.

On the pro-algebra side, we have the argument that learning algebra II promotes abstract thinking. It’s the first time you go from thinking about ratios of integers to ratios of polynomial functions, and where you consider the geometric properties of these generalized fractions. It is a convenient litmus test for even more abstraction: sure, it’s kind of abstract, but on the other hand you can also for the most part draw pictures of what’s going on, to keep things concrete. In that sense you might see it as a launching pad for the world of truly abstract geometric concepts.

Plus, doing well in algebra II is a signal for doing well in college and in later life. Plus, if we remove it as a requirement we might as well admit we’re dumbing down college: we’re giving the message that you can be a college graduate even if you can’t do math beyond adding fractions. And if that’s what college means, why have college? What happened to standards? And how is this preparing our young people to be competitive on a national or international scale?

On the anti-algebra side, we see a lot of empathy for struggling and suffering students. We see that raising so-called standards only gives them more suffering but no more understanding or clarity. And although we’re not sure if that’s because the subject is taught badly or because the subject is inherently unappealing or unattainable, it’s clear that wishful thinking won’t close this gap.

Plus, of course doing well in algebra II is a signal for doing well in college, it’s a freaking prerequisite for going to college. We might as well have embroidery as a prerequisite and then be impressed by all the beautiful piano stool covers that result. Finally, the standards aren’t going up just because we’re training a new generation in how to game a standardized test in an abstract rote-memorization skill of formulas and rules. It’s more like learning student’s capacity for drudgery.

OK, so now I’m going to make comments.

While it’s certainly true that, in the best of situations, the content of algebra II promotes abstract and logical thinking, it’s easy for me to believe, based on my very small experience in the matter that, it’s much more often taught poorly, and the students are expected to memorize formulas and rules. This makes it easier to test but doesn’t add to anyone’s love for math, including people who actually love math.

Speaking of my experience, it’s an important issue. Keep in mind that asking the population of mathematicians what they think of removing a high school class is asking for trouble. This is a group of people who pretty much across the board didn’t have any problems whatsoever with the class in question and sailed through it, possibly with a teacher dedicated to teaching honors students. They likely can’t remember much about their experience, and if they can it probably wasn’t bad.

Plus, removing a math requirement, any math requirement, will seem to a mathematician like an indictment of their field as not as important as it used to be to the world, which is always a bad thing. In other words, even if someone’s job isn’t directly on the line with this issue of algebra II, which it undoubtedly is for thousands of math teachers and college teachers, then even so it’s got a slippery slope feel, and pretty soon we’re going to have math departments shrinking over this.

In other words, it shouldn’t surprised anyone that we have defensive and unsympathetic mathematicians on one side who cannot understand the arguments of the empathizers on the other hand.

Of course, it’s always a difficult decision to remove a requirement. It’s much easier to make the case for a new one than to take one away, except of course for the students who have to work for the ensuing credentials.

And another thing, not so long ago we’d hear people say that women don’t need education at all, or that peasants don’t need to know how to read. Saying that a basic math course should become and elective kind of smells like that too if you want to get histrionic about things.

For myself, I’m willing to get rid of all of it, all the math classes ever taught, at least as a thought experiment, and then put shit back that we think actually adds value. So I still think we all need to know our multiplication tables and basic arithmetic, and even basic algebra so we can deal with an unknown or two. But from then on it’s all up in the air. Abstract reasoning is great, but it can be done in context just as well as in geometry class.

And, coming as I now do from data science, I don’t see why statistics is never taught in high school (at least in mine it wasn’t, please correct me if I’m wrong). It seems pretty clear we can chuck trigonometry out the window, and focus on getting the average high school student up to the point of scientific literacy that she can read a paper in a medical journal and understand what the experiment was and what the results mean. Or at the very least be able to read media reports of the studies and have some sense of statistical significance. That’d be a pretty cool goal, to get people to be able to read the newspaper.

So sure, get rid of algebra II, but don’t stop there. Think about what is actually useful and interesting and mathematical and see if we can’t improve things beyond just removing one crappy class.

MAA Distinguished Lecture Series: Start Your Own Netflix

I’m on my way to D.C. today to give an alleged “distinguished lecture” to a group of mathematics enthusiasts. I misspoke in a previous post where I characterized the audience to consist of math teachers. In fact, I’ve been told it will consist primarily of people with some mathematical background, with typically a handful of high school teachers, a few interested members of the public, and a number of high school and college students included in the group.

So I’m going to try my best to explain three different ways of approaching recommendation engine building for services such as Netflix. I’ll be giving high-level descriptions of a latent factor model (this movie is violent and we’ve noticed you like violent movies), of the co-visitation model (lots of people who’ve seen stuff you’ve seen also saw this movie) and the latent topic model (we’ve noticed you like movies about the Hungarian 1956 Revolution). Then I’m going to give some indication of the issues in doing these massive-scale calculation and how it can be worked out.

And yes, I double-checked with those guys over at Netflix, I am allowed to use their name as long as I make sure people know there’s no affiliation.

In addition to the actual lecture, the MAA is having me give a 10-minute TED-like talk for their website as well as an interview. I am psyched by how easy it is to prepare my slides for that short version using prezi, since I just removed a bunch of nodes on the path of the material without removing the material itself. I will make that short version available when it comes online, and I also plan to share the longer prezi publicly.

[As an aside, and not to sound like an advertiser for prezi (no affiliation with them either!), but they have a free version and the resulting slides are pretty cool. If you want to be able to keep your prezis private you have to pay, but not as much as you’d need to pay for powerpoint. Of course there’s always Open Office.]

Train reading: Wrong Answer: the case against Algebra II, by Nicholson Baker, which was handed to me emphatically by my friend Nick. Apparently I need to read this and have an opinion.

Are PayDay lenders better than banks? #OWS

Sometimes my plan of getting up super early to write on my blog fails, and this is one of those days. But I’m still going to ask you to read this article from the New Yorker written by Lisa Servon and entitled, “The High Cost, For The Poor, Of Using A Bank.” Here’s a key passage, but the whole thing is amazing, and yes, I’ve invited her to my Occupy group already:

To understand why, consider loans of small amounts. People criticize payday loans for their high annual percentage rates (APR), which range from three hundred per cent to six hundred per cent. Payday lenders argue that APR is the wrong measure: the loans, they say, are designed to be repaid in as little as two weeks. Consumer advocates counter that borrowers typically take out nine of these loans each year, and end up indebted for more than half of each year.

But what alternative do low-income borrowers have? Banks have retreated from small-dollar credit, and many payday borrowers do not qualify anyway. It happens that banks offer a de-facto short-term, high-interest loan. It’s called an overdraft fee. An overdraft is essentially a short-term loan, and if it had a repayment period of seven days, the APR for a typical incident would be over five thousand per cent.

It makes me wonder whether, if someone did a careful analysis with all-in costs including time and travel, whether PayDay Lenders are not actually a totally rational choice for the poor.

Indiegogo campaign for 2nd edition of Occupy Finance is up! (#OWS)

Many of you have probably already received copies of Occupy Finance. Here’s my personal evidence, for which I was nearly arrested in the post office (who knew you’re not allowed to take pictures in the post office? not me.):

We’re hoping you loved your book, or if you haven’t gotten a copy yet, that you’d like to get one soon.

The thing is, we’re very nearly out of copies, and plus there was a missing page and a few other typos for which we have forgiven ourselves, since we got it out in time for September 17th, but which we were happy to fix.

Our plan, if we manage to raise enough money (hopefully $3500), is to print a few thousand more copies (hopefully 5,000) and distribute them to places like libraries and bookstores, not to mention to any people we hear of who want to read the book. We’d prefer to raise money for the printing and then give them away over selling them, since we’d like anyone who wants one to have one regardless of their financial situation.

So here’s the Indiegogo page, and I hope you’ll go take a look and send it to your friends who might be interested in contributing. It features our favorite street performer and Action Committee Head Marni, which for this campaign we refer to as our “Indie GoGo Girl”. She does a really fantastic job explaining our goals in the campaign video, located here. You may also know her as the money bunny, she’s kinda famous. She also has a law degree.

The starting donation is $10, and if you’ve already given money to our group, don’t feel like I’m asking you a second time (I don’t wanna be like that!) but just go ahead and tell your friends about us. Thanks!

Also feel free to share the shortlink on twitter or what have you: http://tinyurl.com/occfinindie