Zephyr Teachout to visit Alt Banking this Sunday

I’m excited to announce that Zephyr Teachout, a Fordham Law School professor who is running against Andrew Cuomo for Governor of New York, will be coming to speak to the Alternative Banking group next Sunday, July 13th, from 3pm-5pm in the usual place, Room 409 of the International Affairs Building at 118th and Amsterdam. More about Alt Banking on our website.

Title: Teachout-Wu vs. Cuomo-Hochul in the Democratic Primary in New York!

Description: Come hear candidate Teachout talk about her anti-corruption trust-busting campaign against Governor Cuomo.

Background: Teachout is an antitrust and media expert who served as the Director of Internet organizing for the 2004 Howard Dean Presidential Campaign. She co-founded A New Way Forward, an organization built to break up the power of big banks. Teachout was the first national director of the Sunlight Foundation. More here.

If we have time after talking to Zephyr we will discuss Stiglitz’s article, The Myth Of America’s Golden Age.

Please make time to come hear Zephyr, and please spread the word.

What constitutes evidence?

My most recent Slate Money podcast with Felix Salmon and Jordan Weissmann was more than usually combative. I mean, we pretty much always have disagreements, but Friday it went beyond the usual political angles.

Specifically, Felix thought I was jumping too quickly towards a dystopian future with regards to medical data. My claim was that, now that the ACA has motivated hospitals and hospital systems to keep populations healthy – a good thing in itself – we’re seeing dangerous side-effects involving the proliferation of health profiling and things like “health scores” attached to people much like we now have credit scores. I’m worried that such scores, which are created using data not covered under HIPAA, will be used against people when they try to get a job.

Felix asked me to point to evidence of such usage.

Of course, it’s hard to do that, partly because it’s just the beginning of such data collection – although the FTC’s recent report pointed to data warehouses that already puts people into categories such as “diabetes interest” – and also because it’s proprietary all the way down. In other words, web searches and the like are being legally collected and legally sold and then it’s legal to use risk scores or categories to filter job applications. What’s illegal is to use HIPAA-protected data such as disability status to remove someone from consideration for a job, but that’s not what’s happening.

Anyhoo, it’s made me think. Am I a conspiracy theorist for worrying about this? Or is Felix lacking imagination if he requires evidence to believe it? Or some combination? This is super important to me because if I can’t get Felix, or someone like Felix, to care about this issue, I’m afraid it will be ignored.

This kind of thing came up a second time on that same show, when Felix complained that the series of articles (for example this one from NY Magazine) talking about money laundering in New York real estate also lacked evidence. But that’s also tricky since the disclosure requirements on real estate are not tight. In other words, they are avoiding collecting evidence of money laundering, so it’s hard to complain there’s a lack of data. From my perspective the journalists investigating this article did a good job finding examples of laundering and showing it was easy to set up (especially in Delaware). But Felix wasn’t convinced.

It’s a general question I have, actually, and I’m glad to be involved with the Lede Program because it’s actually my job to think about this kind of thing, especially in the context of journalism. Namely, when do we require data – versus anecdotal evidence – to believe in something? And especially when the data is being intentionally obscured?

Critical Questions for Big Data by danah boyd & Kate Crawford

I’m teaching a class this summer in the Lede Program, starting in mid-July, which is called The Platform. Here’s the course description:

This course begins with the idea that computing tools are the products of human ingenuity and effort. They are never neutral and carry with them the biases of their designers and their design process. “Platform studies” is a new term used to describe investigations into these relationships between computing technologies and the creative or research products that they help to generate. How you understand how data, code, and algorithms affect creative practices can be an effective first step toward critical thinking about technology. This will not be purely theoretical, however, and specific case studies, technologies, and project work will make the ideas concrete.

Since my first class is coming soon, I’m actively thinking about what to talk about and which readings to assign. I’ve got wonderful guest lecturers coming, and for the most part the class will focus on those guest lecturers and their topics, but for the first class I want to give them an overview of a very large subject.

I’ve decided that danah boyd and Kate Crawford’s recent article, Critical Questions for Big Data, is pretty much perfect for this goal. I’ve read and written a lot about big data but even so I’m impressed by how clearly and comprehensively they have laid out their provocations. And although I’ve heard many of the ideas and examples before, some of them are new to me, and are directly related to the theme of the class, for example:

Twitter and Facebook are examples of Big Data sources that offer very poor archiving and search functions. Consequently, researchers are much more likely to focus on something in the present or immediate past – tracking reactions to an election, TV finale, or natural disaster – because of the sheer difficulty or impossibility of accessing older data.

Of course the students in the Lede are journalists, not academic researchers, which the article mostly addresses, and moreover they are not necessarily working with big data per se, but even so they are increasingly working with social media data, and moreover they are probably covering big data even if they don’t directly analyze it. So I think it’s still relevant to them. Or another way to express this is that one thing we will attempt to do in class is examine the extent to which their provocations are relevant.

Here’s another gem, directly related to the Facebook experiment I discussed yesterday:

As computational scientists have started engaging in acts of social science, there is a tendency to claim their work as the business of facts and not interpretation. A model may be mathematically sound, an experiment may seem valid, but as soon as a researcher seeks to understand what it means, the process of interpretation has begun. This is not to say that all interpretations are created equal, but rather that not all numbers are neutral.

In fact, what with this article and that case study, I’m pretty much set for my first day, after combining them with a discussion of the students’ projects and some related statistical experiments.

I also hope to invite at least one of the authors to come talk to the class, although I know they are both incredibly busy. Danah boyd, who recently came out with a book called It’s Complicated: the social lives of networked teens, also runs the Data & Society Research Institute, a NYC-based think/do tank focused on social, cultural, and ethical issues arising from data-centric technological development. I’m hoping she comes and talks about the work she’s starting up there.

Thanks for a great case study, Facebook!

I’m super excited about the recent “mood study” that was done on Facebook. It constitutes a great case study on data experimentation that I’ll use for my Lede Program class when it starts mid-July. It was first brought to my attention by one of my Lede Program students, Timothy Sandoval.

My friend Ernest Davis at NYU has a page of handy links to big data articles, and at the bottom (for now) there are a bunch of links about this experiment. For example, this one by Zeynep Tufekci does a great job outlining the issues, and this one by John Grohol burrows into the research methods. Oh, and here’s the original research article that’s upset everyone.

It’s got everything a case study should have: ethical dilemmas, questionable methodology, sociological implications, and questionable claims, not to mention a whole bunch of media attention and dissection.

By the way, if I sound gleeful, it’s partly because I know this kind of experiment happens on a daily basis at a place like Facebook or Google. What’s special about this experiment isn’t that it happened, but that we get to see the data. And the response to the critiques might be, sadly, that we never get another chance like this, so we have to grab the opportunity while we can.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia has missed you guys, and apologizes for the last two weeks of lost advice-giving opportunities. Her metaphorical advice bus broke down, but it’s back on the road again, it’s got a full tank of gas, and we’re ready to drive anywhere. It’s kind of a luxury winnebego advice bus today, I’m thinking. Here’s the exterior:

And here’s the interior, before the Aunt Pythia advice seekers get there:

Aunt Pythia is either up in front, driving, or she’s reading her new and already beloved copy of The Cartoon Guide to Statistics by Larry Gonick and Wollcott Smith.

Without further ado, let’s begin. And please, after enjoying the on-board cheese and cracker snacks, do your best to

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Thank you for publishing my responses to your Alternative Dating Questions a while back: that was fun! As for getting the “dog or cat” question wrong, it was probably the easiest of the ten for me to answer, on the grounds that when I was young, most of the local canine population decided to redress the “humans eat hotdogs” balance on me, even though I never liked the damned things myself. So I am prejudiced – but with good reason.

I’ve now tried out your questions on my friend Female And Remote And Well As Yummy, and these are her answers (and mine):

- 1.How sexual are you? (super important question) This morning – not very; Approx 8/10 (but sometimes only 2/10, and occasionally 11/10)

- How much fun are you? (people are surprisingly honest when asked this) 7/10; In the right company, this can reach 4/10

- How awesome do you smell? (might need to invent technology for this one) I smell fantastic; Only about 3/10, I’m afraid, but I could scrub up a bit

- What bothers you more: the big bank bailout or the idea of increasing the minimum wage? The big bank bailout; Neither – both bore me

- Do you like strong personalities or would you rather things stay polite? Strong personalities; I’d rather things stay polite?

- What do you love arguing about more: politics or aesthetics? Æsthetics [she didn’t actually answer with the ligatured a and e, but it’s a cultural difference we’ve discussed many times, so I felt justified in correcting her]; Politics, just

- Where would you love to visit if you could go anywhere? England; The Antarctic

- Do you want kids? Yes (I’m happy with those I’ve got); No

- Dog person or cat person? A cat person; A cat person

- Do you sometimes wish the girl could be the hero, and not always fall for the hapless dude at the end? Absolutely; Yes

So my question for you this week (if it’s not greedy to have another one so soon) is: Does Aunt Pythia think there is chemistry here? And if not, what does she think to the chances of at least a little physics?

Kind regards

Male And Deluded

Dear Male and Deluded,

A match made in heaven! First because you’re both cat people, and second because she agreed to fill out this ridiculous questionnaire, which she’d only do if she was interested, and which you’d only ask her to do if you were interested, the vital ingredient. I’d go easy on the spelling corrections though.

Just to be clear, though, the original point of the questionnaire was that normal dating site questions don’t actually supply you with useful information, and I thought we could improve them. So the real question is, after seeing her answers, are you more interested in her? I thought so.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m very sorry about the length of the last letter. I wasn’t in a very good way at the time of writing, and I understand if it wasn’t very comprehensible. I also managed to figure out the answer to my other question (I’m sticking with just doing as much physics as possible and hoping that my record in grad courses makes up for my previous idiocy. Hope you aren’t offended). I’ll keep this as concise as I’m capable of being.

The impossible happened. I have a girlfriend. Combined with my research starting to pick up, a possible end to my financial troubles, a grad school opportunity just peaking up on the horizon, and a good, if not perfect GPA this year (we’ll see), things are looking up. I’ve never felt this positive about my prospects in a while, in spite of the challenges I’m still facing. So, my frame of mind isn’t like it was last time, to be clear. I have two questions about my relationship:

1) I’m going to be in Germany for the summer doing research and we really haven’t been in a relationship for long. We are both a little worried about this and hope to keep going over the summer. Any suggestions for keeping the “flame” alive? She was coming off a pretty rough period when she met me, and was distraught when I was leaving, and I’ve never handled this before.

2) It all feels a little anticlimactic. Is that normal? Part of this might be my insights about life (I finally agreed to get therapy shortly after my first run in here, and it’s helped), about the fact that there is nothing wrong with being a loner and that I shouldn’t try to force myself to be otherwise. But part of it is I don’t feel as *crazy* about the person as I feel I would be about a girlfriend. It could be that what I feel should be isn’t realistic. Though I strongly enjoy her company (we’re both a little weird), I don’t even desire the sex like I thought I would. Is that normal for early relationships in life, when you are figuring everything out, or is there something else going on? I mean, I don’t plan on marrying her or anything, so isn’t that OK? I also occasionally worry about her stability and her place in life, than feel like a hypocrite because I just got some of those issues fixed.

Don’t take any of this to mean that I regret getting into the relationship, it has been a plus so far in my life.

PS: (you can cut this out if you want)

To clarify what I meant, Isaac Newton spent his entire life celibate and isolated. Sheen more than hasn’t and has probably had a lot more fun. Yet, I know who I’d rather be, and in my more misanthropic moments, I think Isaac Newton knew what he was doing. Sex is fun and should be encouraged. But ultimately, it pales in importance to other things. It’s so funny, it seems to be the worst of both worlds in America, with the sex-obsession and the puritanism simultaneously occurring.

I have a LOT of opinions and ideas for the world. Funny you mention the Ukraine, I’m ridiculously interested particularly about foreign policy/politics-I sometimes catch myself thinking about that when I need to do physics. I occasionally bore my girlfriend to tears. I had (have) a lot of problems socially, but believe me, that’s not one of them. Back when I was searching for a girlfriend, I tried to use these interests (foreign policy, literature, history, other cultures, supercomputers-the title I mentioned comes from a play) to meet people and became frustrated when it didn’t work out like I planned. I met the good lady on a dating website that I had long since given up on. The trouble is talking about mundane, day to day things or subjects that I have no interest in. When she wishes to talk about her field of interest, I try my best to hang on, but it can be tough.

Draußen vor der Tür

Dear Draußen,

Here’s the thing. Last time I cut out a bunch of your letter, but this time I left it all, except I did edit a bit (there are spaces before parentheses as well as after) to make things readable. I’m not sure why I’ve decided to do this except that I like to share my pain with my readers. I hope you appreciate this, readers!

A few things. First, congratulations on finding a girlfriend. As to whether the feeling of anti-climax is normal, I guess it depends on what exactly you expected but I’m afraid it isn’t very normal, at least not in my experience. I mean, falling in love is a rush, with dopamine and all that good stuff, so I’m going to guess you aren’t actually falling in love. Maybe your positive feelings are just relief that you’re no longer alone? That’s not the same thing.

Next, the thing about “I don’t plan on marrying her or anything, so …” makes me feel weird. Note I’m not suggesting that you should marry her, but even so it seems like you’re prematurely categorizing her as someone you won’t take seriously, which I think is strange and self-defeating. I might be wrong, and it’s quite possible I’m just responding to cultural norm which I don’t like, namely that men avoid commitment like it’s a punishment, but it just seems like, with that attitude you might not let the relationship succeed.

Finally, the last line of the letter: When she wishes to talk about her field of interest, I try my best to hang on, but it can be tough. This makes me think that either you are seriously one of the most single-minded people in the world, only interested in your immediate field, or you have very little respect for or common interest with your girlfriend, or some combination of those things. This is another red flag, but I’m not sure how you can address is besides looking for a girlfriend who works in the same field as you.

One last meta thing, and I hope I’m not being too tough on you, because you’ve obviously made progress.

I sense that you are someone who consistently sees things in terms of how they affect you. So, for example, you mention that the relationship “has been a plus so far in my life“. But if you are too self-absorbed, you will miss the two most crucial elements of successful relationships: first, enjoying making the other person happy and, what is the flip side of the same coin, feeling grateful that the other person will put up with you. I spend about half of my time being grateful that my partner puts up with me, which is probably not enough, and that gratitude makes my marriage work better.

Does that make sense? Can you be grateful for her patience with you, and can you take pleasure in making her feel secure and loved? If you can, and if you can do that consistently, then I don’t think your Germany trip will be too tough.

Good luck,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’ve passed my stats PhD qualifying exams and have been meeting with an adviser for several months, but want to leave my PhD and become a Data Scientist (or something like that). The problem is I haven’t interned since acquiring my stats skills.

Should I apply for semester internships (these can be completed while taking a course or two and doing research at my program) and a summer 2015 internship and then leave my program (hopefully with a job secured)? Should I also be applying for jobs this coming school year? I’m hesitant to apply for jobs right now as I’d like to improve my computation skills and will be taking a Machine Learning course in the fall. Should I tell my adviser? I don’t want to have to leave the program yet as many internships require you to be in a grad program, and many jobs require past internship experience.

Thank you so much your time!

— Slightly Hyperventilating

Dear Slightly,

If I’m a company looking for a data scientist I’m super happy to hire you after you’ve passed your quals, taken Machine Learning, and acquired keen computational skills. So yes, it’s a great plan.

As for telling your advisor, I think it depends on what they are like and whether they think everyone should be an academic or at least strive to be. Maybe ask other students of this advisor who have left or stayed and see what advice they give?

Good luck, and tell me how it goes!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

Final exams (3rd year university) are around the corner and though I have studied throughout the year I feel I’m still falling short of knowing enough to pass these exams. I keep saying if I don’t pass my finals at least I can retake them but this doesn’t seem to calm my nerves.

Are there any suggestions you can offer to chill (please spare me the British prewar ‘keep calm…’ quotes)?

Thanks,

Anxious about failing

Dear Anxious,

My guess is this advice is coming a little late, but here it is anyway: get together with other students – more than one other, and on separate days – who are also studying for this test and ask them questions and have them ask you stuff. It will surprise you how much you already know and it will solidify your learning to explain stuff to other people.

Good luck!

Auntie P

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

We are not ready for health data mining

There have been two articles very recently about how great health data mining could be if we could only link up all the data sets. Larry Page from Google thinks so, which doesn’t surprise anyone, and separately we are seeing that the consequence of the new medical payment system through the ACA is giving medical systems incentives to keep tabs on you through data providers and find out if you’re smoking or if you need to fill up on asthma medication.

And although many would consider this creepy stalking, that’s not actually my problem with it. I think Larry Page is right – we might be able to save lots of lives if we could mine this data which is currently siloed through various privacy laws. On the other hand, there are reasons those privacy laws exist. Let’s think about that for a second.

Now that we have the ACA, insurers are not allowed to deny Americans medical insurance coverage because of a pre-existing condition, nor are they allowed to charge more, as of 2014. That’s good news on the health insurance front. But what about other aspects of our lives?

For example, it does not generalize to employers. In other words, a large employer like Walmart might take into account your current health and your current behaviors and possibly even your DNA to predict future behaviors, and they might decide not to give jobs to anyone at risk of diabetes, say. Even if medical insurance casts were taken out of the picture, which they haven’t been, they’d have incentives not to hire unhealthy people.

Mind you, there are laws that prevent employers from looking into HIPAA-protected health data, but not Acxiom data, which is entirely unregulated. And if we “opened up all the data” then the laws would be entirely moot. It would be a world where, to get a job, the employer got to see everything about you, including your future health profile. To some extent this is already happening.

Perhaps not everyone thinks of this as bad. After all, many people think smokers should pay more for insurance, why not also work harder to get a job? However, lots of the information gleaned from this data – even behaviors – have much more to do with poverty levels than circumstance than with conscious choice. In other words, it’s another stratification of society along the lucky/unlucky birth lottery spectrum. And if we aren’t careful, we will make it even harder for poor people to eke out a living.

I’m all for saving lives but let’s wait for the laws to catch up with the good intentions. Although to be honest, it’s not even clear how the law should be written, since it’s not clear what “medical” data is nowadays nor how we could gather evidence that a private employer is using it against someone improperly.

Unsolicited advice about having kids

You know how it’s better to have a discussion with someone when you’re calm and they haven’t just done something that drives you absolutely nuts? Well I’m going to generalize to the parenting advice realm: best time to give parenting advice is not when you’ve just seen a kid get poorly parented or a parent stress out about stupid stuff. Best time is when you’re alone in your pajamas, nowhere near other people’s kids. That way those of you who have kids won’t feel defensive.

Also, here’s another rule about parenting advice: never take parenting advice from anyone, because the people who are actually eager to give it are usually super weird. Look at Tiger Mom as Exhibit A.

In spite of that very wise second rule, I’ma go ahead and give some advice that’s pretty good, if I do say so myself in my own weird way.

- Before having kids, think of all the reasons not to. They’re loud, expensive, and they weigh you down immensely. You will never be able to stay up with friends after 10pm again if you do it. So don’t do it.

- Unless… unless you just absolutely cannot help it because of all those freaking hormones and how cute they look in summer dresses (boys included, yes, they don’t care, they’re babies). Then do it, but think hard and plan well for the noise, the expense, and the inconvenience.

- In terms of how you parent a baby: think long-term about stuff. Are you gonna want to get up a million times every night for the rest of your life? No, you’re not. So figure out how to get the damn baby to sleep through the night. This cannot be forced until the kid is 6 months or so, and the moment you can manipulate their sleep is characterized by the moment they can try to manipulate their sleep and stay awake to hang out with you. That’s when you start the 6pm bedtime ritual, including songs and books and 6:30 lights out. They will cry for like 10 minutes three nights in a row and after that you will be golden. Long term thinking, remember. Even if they cry for an hour, it’s an investment for a lifetime, namely yours.

- In terms of how you parent a little kid: think super long-term about stuff. Don’t raise your voice unless they are doing something actually dangerous, like walking into traffic or sticking a fork into an outlet. Make sure you let them get really dirty and try to eat weird things, too – their tongues are like extra hands at this age, it helps them explore the world. The only thing a little kid really needs is regular meals and a 6 or maybe 7pm bedtime ritual. They can spend 2 hours ripping up a newspaper for entertainment. Once a week baths would be good.

- In terms of how you parent a school age kid: think super duper long-term about stuff. If you do their homework for them, they will never do it themselves. So let them figure that out, but do remind them to do it if they’re forgetful. If you structure all their time, they will never figure out what they love to do, so make sure they get bored sometimes. Keep lots of good books and nerdy puzzles and interesting people around the house but don’t make them “do math” with you unless they ask for it. Don’t make them take music lessons. Instead, wait for them to beg for music lessons, and then say no for a while until you’re really sure they want them. Don’t just tell them to be nice, exhibit nice behavior to them and to others in front of them. Reward them for pointing out your hypocrisies, and make them watch Star Trek: The Next Generation (or equivalent) with you for its moral education and for the popcorn, and have fun listening to them pointing out the bad physics. And the most important of all: enjoy them and have fun with them, because that’s the best kind of way to role model for your kids, plus it’s fun, and they’re people who will move away pretty soon and you’ll miss them.

- In terms of how you parent an older kid, I have no idea because my oldest kid is 14. But so far we’re having a blast. I’m pretty sure they’re already mostly raised in terms of my role anyway by the time they’re 12.

One last, general thing for today’s anxious parents: don’t feel guilty, you’re doing your best. Guilt is a waste of time and gets in the way of enjoying the popcorn.

The dark matter of big data

A tiny article in The Cap Times was recently published (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg) which describes the existence of a big data model which claims to help filter and rank school teachers based on their ability to raise student test scores. I guess it’s a kind of pre-VAM filtering system, and if it was hard to imagine a more vile model than the VAM, here you go. The article mentioned that the Madison School Board was deliberating on whether to spend $273K on this model.

One of the teachers in the district wrote her concerns about this model in her blog and then there was a debate at the school board meeting, and a journalist covered the meeting, so we know about it. But it was a close call, and this one could have easily slipped under the radar, or at least my radar.

Even so, now I know about it, and once I looked at the website of the company promoting this model, I found links to an article where they name a customer, for example in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District of North Carolina. They claim they only filter applications using their tool, they don’t make hiring decisions. Cold comfort for people who got removed by some random black box algorithm.

I wonder how many of the teachers applying to that district knew their application was being filtered through such a model? I’m going to guess none. For that matter, there are all sorts of application screening algorithms being regularly used of which applicants are generally unaware.

It’s just one example of the dark matter of big data. And by that I mean the enormous and growing clusters of big data models that are only inadvertently detectable by random small-town or small-city budget meeting journalism, or word-of-mouth reports coming out of conferences or late-night drinking parties with VC’s.

The vast majority of big data dark matter is still there in the shadows. You can only guess at its existence and its usage. Since the models themselves are proprietary, and are generally deployed secretly, there’s no reason for the public to be informed.

Let me give you another example, this time speculative, but not at all unlikely.

Namely, big data health models arising from the quantified self movement data. This recent Wall Street Journal article entitled Can Data From Your Fitbit Transform Medicine? articulated the issue nicely:

A recent review of 43 health- and fitness-tracking apps by the advocacy group Privacy Rights Clearinghouse found that roughly one-third of apps tested sent data to a third party not disclosed by the developer. One-third of the apps had no privacy policy. “For us, this is a big trust issue,” said Kaiser’s Dr. Young.

Consumer wearables fall into a regulatory gray area. Health-privacy laws that prevent the commercial use of patient data without consent don’t apply to the makers of consumer devices. “There are no specific rules about how those vendors can use and share data,” said Deven McGraw, a partner in the health-care practice at Manatt, Phelps, and Phillips LLP.

The key is that phrase “regulatory gray area”; it should make you think “big data dark matter lives here”.

When you have unprotected data that can be used as a proxy of HIPAA-protected medical data, there’s no reason it won’t be. So anyone who wants stands to benefit from knowing health-related information about you – think future employers who might help pay for future insurance claims – will be interested in using big data dark matter models gleaned from this kind of unregulated data.

To be sure, most people nowadays who wear fitbits are athletic, trying to improve their 5K run times. But the article explained that the medical profession is on the verge of suggesting a much larger population of patients use such devices. So it could get ugly real fast.

Secret big data models aren’t new, of course. I remember a friend of mine working for a credit card company a few decades ago. Her job was to model which customers to offer subprime credit cards to, and she was specifically told to target those customers who would end up paying the most in fees. But it’s become much much easier to do this kind of thing with the proliferation of so much personal data, including social media data.

I’m interested in the dark matter, partly as research for my book, and I’d appreciate help from my readers in trying to spot it when it pops up. For example, I remember begin told that a certain kind of online credit score is used to keep people on hold for customer service longer, but now I can’t find a reference to it anywhere. We should really compile a list at the boundaries of this dark matter. Please help! And if you don’t feel comfortable commenting, my email address is on the About page.

You are not Google’s customer

I’m going to write one of those posts where many of you will already understand my point. In fact it might be old hat for a majority of my readers, yet it’s still important enough for me to mention just in case there are a few people out there who don’t know how the modern business model is set up.

Namely, like this. As a gmail and Google Search user, you are not a customer of Google. You are the product. The customers of Google are the ones who advertise to you. Your interaction with Google is, from the perspective of the business operation, that you give them information which they harvest so they can advertise to you in a more targeted way, thus increasing the likelihood of you clicking. The fact that you get a service from these interactions is great, because it means you’ll come back to give Google and its customers more information about you soon.

This misunderstanding, once you see it as such, can be clarifying. For example, when people talk about anti-trust and Google, they should talk about whether the customers of Google have any other serious choice. And since the customers of Google are advertisers, not gmailers or searchers, the alternatives aren’t hotmail or Bing. Rather they are other advertising outlets. And a very good case can be made that Google does violate anti-trust laws in that sense, just ask Nathan Newman.

It also explains why something like the recent European “right to be forgotten” law seems so strange and unreasonable to the powers that be at Google. It’d be like a meat farm where the cows go on strike and demand better food. Cows are the product, and they aren’t supposed to complain. They’re not even supposed to be heard. At worst we treat them better when our customers demand it, not when the cows do.

I was reminded about this ubiquitous business model yesterday, and newly enraged by its consequences, when reading this article entitled Held Captive by Flawed Credit Reports (hat tip Linda Brown) about the credit score agency Experian and how they utterly disregard the laws trying to protect consumers from mistakes in their credit reports. The problem here is that, to the giant company Experian, its customers are giant companies like Verizon which send credit score requests millions of times a day and pay for each score. Mere people, whose mortgage application is being denied because of mistakes, are the product, not the customer, and they are almost by definition unimportant.

And it seems that the law which is supposed to protect these people, namely the Fair Credit Reporting Act, first passed in 1970, doesn’t have enough teeth behind it to make the big credit scoring agencies sit up and pay attention. It’s all about the scale of the fines compare to the scale of the business. This is well explained in the article (emphasis mine):

Last year, the Federal Trade Commission found that 5 percent of consumers — or an estimated 10 million people — had an error on one of their credit reports that could have resulted in higher borrowing costs.

The F.T.C., which oversees the industry along with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has been busy bringing cases in this arena. Since 2000, it has filed 18 enforcement actions against reporting bureaus; 13 were district court actions that generated $25.7 million in penalties.

Consumers have also won in the courts, on occasion. Last year, an Oregon consumer was awarded $18.4 million in punitive damages by a jury after she sued Equifax for inserting errors into her credit report. But the fines, settlements and judgments paid by the larger companies are not even close to a rounding error. Experian generated $4.8 billion in revenue for the year ended March 2014, and its after-tax profit of $747 million in the period was more than twice its 2013 figure.

Million versus billion. It seems like the cows don’t have much leverage.

Guest post: What is the goal of a college calculus course?

This is a guest post by Nathan, who recently finished graduate school in math, and will begin a post-doc in the fall. He loves teaching young kids, but is still figuring out how to motivate undergraduates.

The question

Like most mathematicians in academia, I’m teaching calculus in the fall. I taught in grad school, but the syllabus and assignments were already set. This time I’ll be in charge, so I need to make some design decisions, like the following:

- Are calculators/computers/notes allowed on the exams?

- Which purely technical skills must students master (by a technical skill I mean something like expanding rational functions into partial fractions: a task which is deterministic but possibly intricate)?

- Will students need to write explanations and/or proofs?

I have some angst about decisions like these, because it seems like each one can go in very different directions depending on what I hope the students are supposed to get from the course. If I’m listing the pros and cons of permitting calculators, I need some yardstick to measure these pros and cons.

My question is: what is the goal of a college calculus course?

I’d love to have an answer that is specific enough that I can use it to make concrete decisions like the ones above. Part of my angst is that I’ve asked many people this question, including people I respect enormously for their teaching, but often end up with a muddled answer. And there are a couple stock answers that come to mind, but each one doesn’t satisfy me for one reason or another. Here’s what I have so far.

The contenders.

To teach specific tasks that are necessary for other subjects.

These tasks would include computing integrals and derivatives, converting functions to power series or Fourier series, and so forth.

Intuitive understanding of functions and their behavior.

This is vague, so here’s an example: a couple years ago, a friend in medical school showed me a page from his textbook. The page concerned whether a certain drug would affect heart function in one way or in the opposite way (it caused two opposite effects), and it showed a curve relating two involved parameters. It turned out that the essential feature was that this curve was concave down. The book did not use the phrase “concave down,” though, and had a rather wordy explanation of the behavior. In this situation, a student who has a good grasp of what concavity is and what its implications are is better equipped to understand the effect described in the book. So if a student has really learned how to think about concavity of functions and its implications, then she can more quickly grasp the essential parts of this medical situation.

To practice communicating with precision.

I’m taking “communication” in a very wide sense here: carefully showing the steps in an integral calculation would count.

Not Satisfied

I have issues with each of these as written. I don’t buy number 1, because the bread and butter of calculus class, like computing integrals, isn’t something most doctors or scientists will ever do again. Number 2 is a noble goal, but it’s overly idealistic; if this is the goal, then our success rate is less than 10%. Number 3 also seems like a great goal, relevant for most of the students, but I think we’d have to write very different sorts of assignments than we currently do if we really want to aim for it.

I would love to have a clear and realistic answer to this question. What do you think?

Clearwater Festival and Pete Seeger

After recording my weekly Slate Money podcast this morning I will be off to the Clearwater Festival in Croton-on-Hudson. The weather’s supposed to be gorgeous all weekend, which is good because I’m camping in a tent, and the last few times I went to bluegrass or folk festivals and camped in a tent it rained and I ended up sleeping in puddles. If you’ve never done that, let me tell you that there’s something gross and creepy about wet pillows.

My bandmate Jamie, who plays the mandolin and washboard, convinced me not only to go but to be a volunteer at this festival, which as it turns out means I’ll be preparing food in the kitchen. There are 1,000 volunteers at this festival, so who knows how many people go; I’m preparing for a lot of diced carrots and onions no matter what. Or maybe I’ll be doing dishes. I love doing dishes for some reason.

So this Clearwater Festival was Pete Seeger’s baby, he came every year, and since he passed away this past winter, the entire weekend will be a tribute to his life and his work. Some incredible musicians are going to be there to honor Pete, and I am hoping my kitchen duties don’t conflict with my old favorite, Marty Sexton (Sunday at 4pm), as well as my new favorite, John Fullbright (Saturday at 2:30).

Stuff I’ve packed for the trip: tent, sleeping bag, pillow (dry so far), bluegrass juice (of the Jack Daniels variety), my fiddle, my banjo, a wooden bowl and utensils, and some metal coffee cups and shot glasses. Oh, and some clothes.

You should totally come by for either day or for the whole weekend if you’re nearby and in the mood for some really old hippy reminiscences! And really, who isn’t.

Circular arguments, eigenjesus, and climate change

No time for a post this morning but go read this post by Scott Aaronson on using a PageRank-like algorithm to understand human morality and decision making. The post is funny, clever, very thoughtful, and pretty long.

Marc Andreessen and Al3x Payne

My friend Chris Wiggins just sent me this recent letter by Alex “Al3x” Payne in response to this recent post by Marc Andreessen. Andreessen’s original post is entitled This is Probably a Good Time to Say That I Don’t Believe Robots Will Eat All the Jobs… and the rebuttal is entitled simply Dear Marc Andreessen.

To get a flavor of the exchange, we’ll start with this from Andreessen:

What never gets discussed in all of this robot fear-mongering is that the current technology revolution has put the means of production within everyone’s grasp. It comes in the form of the smartphone (and tablet and PC) with a mobile broadband connection to the Internet. Practically everyone on the planet will be equipped with that minimum spec by 2020.

versus this from Payne:

If we’re gonna throw around Marxist terminology, though, can we at least keep Karl’s ideas intact? Workers prosper when they own the means of production. The factory owner gets rich. The line worker, not so much.

Owning a smartphone is not the equivalent of owning a factory. I paid for my iPhone in full, but Apple owns the software that runs on it, the patents on the hardware inside it, and the exclusive right to the marketplace of applications for it.

…

You spent a lot of paragraphs on back-of-the-napkin economics describing the coming Awesome Robot Future, addressing the hypotheticals. What you left out was the essential question: who owns the robots?

Please read both the original post and the rebuttal in their entireties. At it’s heart, their conversation strikes me as a somewhat more contentious version of the argument I’ve had with myself about the utopia envisioned in Star Trek.

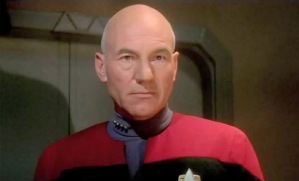

Namely, at some point we’ll have all these robots doing stuff for us, but how are we going to spread that wealth around? Who owns the robots and when are they going to learn to share? In this vision of the distant future, that critical “singularity of moral enlightenment” (SME) is never explained. I wish I could ask Captain Picard how it all went down.

It’s one thing to lack an explanation for the SME, and to consider it an aspirational quasi-religious utopian goal, but it’s another thing entirely to fail to acknowledge it.

That someone as powerful and famous as Mark Andreessen, who is personally involved in the development and nurturing of so many technology platforms, has trouble seeing the logical inconsistency of his own rhetoric can only be explained by the fact that, as the controller of such platforms, it is he who reaps their benefits. It’s yet another case of someone thinking “this system works for me therefore it is super awesome for everyone and everything, amen.”

I’m hoping Al3x’s fine response will get Marc to consider how SME is gonna happen, and when.

Correlation does not imply equality

One of the reasons I enjoy my blog is that I get to try out an argument and then see if readers can 1) poke holes in my arguement, or 2) if they misunderstand my argument, or 3) if they misunderstand something tangential to my argument.

Today I’m going to write about an issue of the third kind. Yesterday I talked about how I’d like to see the VAM scores for teachers directly compared to other qualitative scores or other VAM scores so we could see how reliably they regenerate various definitions of “good teaching.”

The idea is this. Many mathematical models are meant to replace a human-made model that is deemed too expensive to work out at scale. Credit scores were like that; take the work out of the individual bankers’ hands and create a mathematical model that does the job consistently well. The VAM was originally intended as such – in-depth qualitative assessments of teachers is expensive, so let’s replace them with a much cheaper option.

So all I’m asking is, how good a replacement is the VAM? Does it generate the same scores as a trusted, in-depth qualitative assessment?

When I made the point yesterday that I haven’t seen anything like that, a few people mentioned studies that show positive correlations between the VAM scores and principal scores.

But here’s the key point: positive correlation does not imply equality.

Of course sometimes positive correlation is good enough, but sometimes it isn’t. It depends on the context. If you’re a trader that makes thousands of bets a day and your bets are positively correlated with the truth, you make good money.

But on the other side, if I told you that there’s a ride at a carnival that has a positive correlation with not killing children, that wouldn’t be good enough. You’d want the ride to be safe. It’s a higher standard.

I’m asking that we make sure we are using that second, higher standard when we score teachers, because their jobs are increasingly on the line, so it matters that we get things right. Instead we have a machine that nobody understand that is positively correlated with things we do understand. I claim that’s not sufficient.

Let me put it this way. Say your “true value” as a teacher is a number between 1 and 100, and the VAM gives you a noisy approximation of your value, which is 24% correlated with your true value. And say I plot your value against the approximation according to VAM, and I do that for a bunch of teachers, and it looks like this:

So maybe your “true value” as a teacher is 58 but the VAM gave you a zero. That would not just be frustrating to you, since it’s taken as an important part of your assessment. You might even lose your job. And you might get a score of zero many years in a row, even if your true score stays at 58. It’s increasingly unlikely, to be sure, but given enough teachers it is bound to happen to a handful of people, just by statistical reasoning, and if it happens to you, you will not think it’s unlikely at all.

So maybe your “true value” as a teacher is 58 but the VAM gave you a zero. That would not just be frustrating to you, since it’s taken as an important part of your assessment. You might even lose your job. And you might get a score of zero many years in a row, even if your true score stays at 58. It’s increasingly unlikely, to be sure, but given enough teachers it is bound to happen to a handful of people, just by statistical reasoning, and if it happens to you, you will not think it’s unlikely at all.

In fact, if you’re a teacher, you should demand a scoring system that is consistently the same as a system you understand rather than positively correlated with one. If you’re working for a teachers’ union, feel free to contact me about this.

One last thing. I took the above graph from this post. These are actual VAM scores for the same teacher in the same year but for two different class in the same subject – think 7th grade math and 8th grade math. So neither score represented above is “ground truth” like I mentioned in my thought experiment. But that makes it even more clear that the VAM is an insufficient tool, because it is only 24% correlated with itself.

Why Chetty’s Value-Added Model studies leave me unconvinced

Every now and then when I complain about the Value-Added Model (VAM), people send me links to recent papers written Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff like this one entitled Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II: Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood or its predecessor Measuring the Impacts of Teachers I: Evaluating Bias in Teacher Value-Added Estimates.

I think I’m supposed to come away impressed, but that’s not what happens. Let me explain.

Their data set for students scores start in 1989, well before the current value-added teaching climate began. That means teachers weren’t teaching to the test like they are now. Therefore saying that the current VAM works because an retrograded VAM worked in 1989 and the 1990’s is like saying I must like blueberry pie now because I used to like pumpkin pie. It’s comparing apples to oranges, or blueberries to pumpkins.

I’m surprised by the fact that the authors don’t seem to make any note of the difference in data quality between pre-VAM and current conditions. They should know all about feedback loops; any modeler should. And there’s nothing like telling teachers they might lose their job to create a mighty strong feedback loop. For that matter, just consider all the cheating scandals in the D.C. area where the stakes were the highest. Now that’s a feedback loop. And by the way, I’ve never said the VAM scores are totally meaningless, but just that they are not precise enough to hold individual teachers accountable. I don’t think Chetty et al address that question.

So we can’t trust old VAM data. But what about recent VAM data? Where’s the evidence that, in this climate of high-stakes testing, this model is anything but random?

If it were a good model, we’d presumably be seeing a comparison of current VAM scores and current other measures of teacher success and how they agree. But we aren’t seeing anything like that. Tell me if I’m wrong, I’ve been looking around and I haven’t seen such comparisons. And I’m sure they’ve been tried, it’s not rocket science to compare VAM scores with other scores.

The lack of such studies reminds me of how we never hear about scientific studies on the results of Weight Watchers. There’s a reason such studies never see the light of day, namely because whenever they do those studies, they decide they’re better off not revealing the results.

And if you’re thinking that it would be hard to know exactly how to rate a teacher’s teaching in a qualitative, trustworthy way, then yes, that’s the point! It’s actually not obvious how to do this, which is the real reason we should never trust a so-called “objective mathematical model” when we can’t even decide on a definition of success. We should have the conversation of what comprises good teaching, and we should involve the teachers in that, and stop relying on old data and mysterious college graduation results 10 years hence. What are current 6th grade teachers even supposed to do about studies like that?

Note I do think educators and education researchers should be talking about these questions. I just don’t think we should punish teachers arbitrarily to have that conversation. We should have a notion of best practices that slowly evolve as we figure out what works in the long-term.

So here’s what I’d love to see, and what would be convincing to me as a statistician. If we see all sorts of qualitative ways of measuring teachers, and see their VAM scores as well, and we could compare them, and make sure they agree with each other and themselves over time. In other words, at the very least we should demand an explanation of how some teachers get totally ridiculous and inconsistent scores from one year to the next and from one VAM to the next, even in the same year.

The way things are now, the scores aren’t sufficiently sound be used for tenure decisions. They are too noisy. And if you don’t believe me, consider that statisticians and some mathematicians agree.

We need some ground truth, people, and some common sense as well. Instead we’re seeing retired education professors pull statistics out of thin air, and it’s an all-out war of supposed mathematical objectivity against the civil servant.

Getting rid of teacher tenure does not solve the problem

There’s been a movement to make primary and secondary education run more like a business. Just this week in California, a lawsuit funded by Silicon Valley entrepreneur David Welch led to a judge finding that student’s constitutional rights were being compromised by the tenure system for teachers in California.

The thinking is that tenure removes the possibility of getting rid of bad teachers, and that bad teachers are what is causing the achievement gap between poor kids and well-off kids. So if we get rid of bad teachers, which is easier after removing tenure, then no child will be “left behind.”

The problem is, there’s little evidence for this very real achievement gap problem as being caused by tenure, or even by teachers. So this is a huge waste of time.

As a thought experiment, let’s say we did away with tenure. This basically means that teachers could be fired at will, say through a bad teacher evaluation score.

An immediate consequence of this would be that many of the best teachers would get other jobs. You see, one of the appeals of teaching is getting a comfortable pension at retirement, but if you have no idea when you’re being dismissed, then it makes no sense to put in the 25 or 30 years to get that pension. Plus, what with all the crazy and random value-added teacher models out there, there’s no telling when your score will look accidentally bad one year and you’ll be summarily dismissed.

People with options and skills will seek other opportunities. After all, we wanted to make it more like a business, and that’s what happens when you remove incentives in business!

The problem is you’d still need teachers. So one possibility is to have teachers with middling salaries and no job security. That means lots of turnover among the better teachers as they get better offers. Another option is to pay teachers way more to offset the lack of security. Remember, the only reason teacher salaries have been low historically is that uber competent women like Laura Ingalls Wilder had no other options than being a teacher. I’m pretty sure I’d have been a teacher if I’d been born 150 years ago.

So we either have worse teachers or education doubles in price, both bad options. And, sadly, either way we aren’t actually addressing the underlying issue, which is that pesky achievement gap.

People who want to make schools more like businesses also enjoy measuring things, and one way they like measuring things is through standardized tests like achievement scores. They blame teachers for bad scores and they claim they’re being data-driven.

Here’s the thing though, if we want to be data-driven, let’s start to maybe blame poverty for bad scores instead:

I’m tempted to conclude that we should just go ahead and get rid of teacher tenure so we can wait a few years and still see no movement in the achievement gap. The problem with that approach is that we’ll see great teachers leave the profession and no progress on the actual root cause, which is very likely to be poverty and inequality, hopelessness and despair. Not sure we want to sacrifice a generation of students just to prove a point about causation.

On the other hand, given that David Welch has a lot of money and seems to be really excited by this fight, it looks like we might have no choice but to blame the teachers, get rid of their tenure, see a bunch of them leave, have a surprise teacher shortage, respond either by paying way more or reinstating tenure, and then only then finally gather the data that none of this has helped and very possibly made things worse.

Review: House of Debt by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi

I just finished House of Debt by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, which I bought as a pdf directly from the publisher.

This is a great book. It’s well written, clear, and it focuses on important issues. I did not check all of the claims made by the data but, assuming they hold up, the book makes two hugely important points which hopefully everyone can understand and debate, even if we don’t all agree on what to do about them.

First, the authors explain the insufficiency of monetary policy to get the country out of recession. Second, they suggest a new way to structure debt.

To explain these points, the authors do something familiar to statisticians: they think about distributions rather than averages. So rather than talking about how much debt there was, or how much the average price of houses fell, they talked about who was in debt, and where they lived, and which houses lost value. And they make each point carefully, with the natural experiments inherent in our cities due to things like available land and income, to try to tease out causation.

Their first main point is this: the financial system works against poor people (“borrowers”) much more than rich people (“lenders”) in times of crisis, and the response to the financial crisis exacerbated this discrepancy.

The crisis fell on poor people much more heavily: they were wiped out by the plummeting housing prices, whereas rich people just lost a bit of their wealth. Then the government stepped in and protected creditors and shareholders but didn’t renegotiate debt, which protected lenders but not borrowers. This is a large reason we are seeing so much increasing inequality and why our economy is stagnant. They make the case that we should have bailed out homeowners not only because it would have been fair but because it would have been helpful economically.

The authors looked into what actually caused the Great Recession, and they come to a startling conclusion: that the banking crisis was an effect, rather than a cause, of enormous household debt and consumer pull-back. Their narrative goes like this: people ran up debt, then started to pull back, and and as a result the banking system collapsed, as it was utterly dependent on ever-increasing debt. Moreover, the financial system did a very poor job of figuring out how to allocate capital and the people who made those loans were not adequately punished, whereas the people who got those loans were more than reasonably punished.

About half of the run-up of household debt was explained by home equity extraction, where people took out money from their home to spend on stuff. This is partly due to the fact that, in the meantime, wages were stagnant and home equity was a big thing and was hugely available.

But the authors also made the case that, even so, the bubble wasn’t directly caused by rising home valuations but rather to securitization and the creation of “financial innovation” which made investors believe they were buying safe products which were in fact toxic. In their words, securities are invented to exploit “neglected risks” (my experience working in a financial risk firm absolutely agrees to this; whenever you hear the phrase “financial innovation,” please interpret it to mean “an instrument whose risk hides somewhere in the creases that investors are not yet aware of”).

They make the case that debt access by itself elevates prices and build bubbles. In other words, it was the sausage factory itself, producing AAA-rated ABS CDO’s that grew the bubble.

Next, they talked about what works and what doesn’t, given this distributional way of looking at the household debt crisis. Specifically, monetary policy is insufficient, since it works through the banks, who are unwilling to lend to the poor who are already underwater, and only rich people benefit from cheap money and inflated markets. Even at its most extreme, the Fed can at most avoid deflation but it not really help create inflation, which is what debtors need.

Fiscal policy, which is to say things like helicopter money drops or added government jobs, paid by taxpayers, is better but it makes the wrong people pay – high income earners vs. high wealth owners – and isn’t as directly useful as debt restructuring, where poor people get a break and it comes directly from rich people who own the debt.

There are obstacles to debt restructuring, which are mostly political. Politicians are impotent in times of crisis, as we’ve seen, so instead of waiting forever for that to happen, we need a new kind of debt contract that automatically gets restructured in times of crisis. Such a new-fangled contract would make the financial system actually spread out risk better. What would that look like?

The authors give two examples, for mortgages and student debt. The student debt example is pretty simple: how quickly you need to pay back your loans depends in part on how many jobs there are when you graduate. The idea is to cushion the borrower somewhat from macro-economic factors beyond their control.

Next, for mortgages, they propose something the called the shared-responsibility mortgage. The idea here is to have, say, a 30-year mortgage as usual, but if houses in your area lost value, your principal and monthly payments would go down in a commensurate way. So if there’s a 30% drop, your payments go down 30%. To compensate the lenders for this loss-share, the borrowers also share the upside: 5% of capital gains are given to the lenders in the case of a refinancing.

In the case of a recession, the creditors take losses but the overall losses are smaller because we avoid the foreclosure feedback loops. It also acts as a form of stimulus to the borrowers, who are more likely to spend money anyway.

If we had had such mortgage contracts in the Great Recession, the authors estimate that it would have been worth a stimulus of $200 billion, which would have in turn meant fewer jobs lost and many fewer foreclosures and a smaller decline of housing prices. They also claim that shared-responsibility mortgages would prevent bubbles from forming in the first place, because of the fear of creditors that they would be sharing in the losses.

A few comments. First, as a modeler, I am absolutely sure that once my monthly mortgage payment is directly dependent on a price index, that index is going to be manipulated. Similarly as a college graduate trying to figure out how quickly I need to pay back my loans. And depending on how well that manipulation works, it could be a disaster.

Second, it is interesting to me that the authors make no mention of the fact that, for many forms of debt, restructuring is already a typical response. Certainly for commercial mortgages, people renegotiate their principal all the time. We can address the issue of how easy it is to negotiate principal directly by talking about standards in contracts.

Having said that I like the idea of having a contract that makes restructuring automatic and doesn’t rely on bypassing the very real organizational and political frictions that we see today.

Let me put it this way. If we saw debt contracts being written like this, where borrowers really did have down-side protection, then the people of our country might start actually feeling like the financial system was working for them rather than against them. I’m not holding my breath for this to actually happen.

Update on the Lede Program

My schedule nowadays is to go to the Lede Program classes every morning from 10am until 1pm, then office hours, when I can, from 2-4pm. The students are awesome and are learning a huge amount in a super short time.

So for instance, last time I mentioned we set up iPython notebooks on the cloud, on Amazon EC2 servers. After getting used to the various kinds of data structures in python like integers and strings and lists and dictionaries, and some simple for loops and list comprehensions, we started examining regular expressions and we played around with the old enron emails for things like social security numbers and words that had four or more vowels in a row (turns out that always means you’re really happy as in “woooooohooooooo!!!” or really sad as in “aaaaaaarghghgh”).

Then this week we installed git and started working in an editor and using the command line, which is exciting, and then we imported pandas and started to understand dataframes and series and boolean indexes. At some point we also plotted something in matplotlib. We had a nice discussion about unsupervised learning and how such techniques relate to surveillance.

My overall conclusion so far is that when you have a class of 20 people installing git, everything that can go wrong does (versus if you do it yourself, then just anything that could go wrong might), and also that there really should be a better viz tool than matplotlib. Plus my Lede students are awesome.

String Telephone

We moved to our apartment in New York almost exactly 9 years ago. I know that in part because I remember the date we moved in – June 4th, 2005 – but also because that first weekend we lived here, when we decided to try to buy some furniture for our nearly empty living room, we had to cross the Puerto Rican parade to get to Crate & Barrel on the east side of 5th Avenue. It was one of the most characteristic New York moments of my existence, and it made me feel like a real New Yorker.

About two days after moving in I figured out with my friend Michael Thaddeus (who has guest blogged hugely successfuly before) that his apartment was within direct sight of mine. We could wave to each other from our windows across both 116th and Claremont! For a suburban girl like me this was a hoot. We decided to build a string telephone at some point.

Well, we finally got around to doing it yesterday.

I live on the 9th floor, and Thads lives on the 5th floor of his apartment, so there was no chance we could throw anything up to the window on the outside. Instead Thads came over with two balls of string and two cans. For each window we lowered the string to the street with the help of someone on the street who could guide the person in the window. I actually only saw the first half of this procedure because I was tasked with holding the string after the first window and waiting for the second string to be lowered. Then the idea was we’d tie the two strings together.

So here I am, outside my building, holding a string in my hand that goes all the way up to a 9th floor building across the street. I’m also wearing my cowboy hat because it’s sunny outside, but for some reason the combination made everyone walking by stop and ask me what the hell I’m doing.

You see, there aren’t many things that can make New Yorkers talk to each other on the street, but I’ve found that holding on to very very long strings whilst wearing a ridiculous hat does the trick.

My favorite was when this middle aged Greek guy comes up to me and asks me what I’m doing, but he’s clearly hoping it’s mischievous, so I asked him to guess, and he says “You’re pulling someone’s tooth!!”.

After a while my neighbors noticed the string outside their window and got involved. And I noticed the security guard on the corner paying close attention, especially when we had both strings on the street and we were trying to tie them together, which took a while because they barely reached.

There was even a cop car silently observing that part of the experiment, but it disappeared as soon as we got it connected and Johan pulled the string taut so it was above the tree line.

After poking the strings into the cans, we tried our our string telephone. It was incredibly fun.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Peoples! Peoples!!

Aunt Pythia is super glad to be here. It’s a gorgeous day, Aunt Pythia has super fun plans that involve this place in Morristown, New Jersey, and the world is looking bright and colorful and happy. Aunt Pythia’s usual skeptical gloom has given way to rainbows and puppies (Aunt Pythia is a dog person).

Are you with me peoples?! Give it up for life! Give it up for humanity!!

Having said that, Aunt Pythia has more than her usual number of slapdowns to administer today, as you will soon see below.

Don’t be intimidated, though, folks! After watching the abuse, do your best to

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Have you seen this, combining two blog interests?

Huh

Dear Huh,

So yeah, shortest Aunt Pythia question ever. Turns out “this” is an article about yet another person who “hacked” OKCupid to find the love of their life. A male mathematician who dove headlong into the data mining of love. Ho hum.

Please also see [another earlier article], where it was a woman instead of a man. I can’t find it now because this article became so popular that it’s cockblocking my google searches. Wait, I think she gave a TED talk as well. Oh yeah here she is! And she reverse-engineered the algorithm, too. And honestly she’s telling her own story which is way more engaging than that article.

Anyhoo, here’s the thing. First of all, ew. He went on way too many dates too quickly. I’m glad he found love eventually, but let’s face it, he was making himself less receptive, not more receptive, by going on all those dates. Plus he was posing artificially based on his “mathematical research,” which came down to a clustering algorithm. Plus the woman he eventually proposed to FOUND HIM. Plus ew.

I think this reaction post said it best:

“…the idea that math (or, more broadly, “formulas”) can be used as a dating tactic is a surprisingly popular belief based on a number of very flawed premises, many of which reveal pickup artist-flavor misogynist attitudes among the nerdy white guys who champion them.”

Now given that I also have an example of a woman doing this, I’m not gonna claim it’s all about sexism (although there’s more than a veneer of nerdiness!). Rather, it’s all about the weird non-human mindset. Here’s another stab at what I’m talking about:

“But much of the language used in the story reflects a weird mathematician-pickup artist-hybrid view of women as mere data points anyway, often quite literally: McKinlay refers to identity markers like ethnicity and religious beliefs as “all that crap”; his “survey data” is organized into a “single, solid gob”; unforeseen traits like tattoos and dog ownership are called “latent variables.” By viewing himself as a developer, and the women on OkCupid as subjects to be organized and “mined,” McKinlay places himself in a perceived greater place of power. Women are accessories he’s entitled to. Pickup artists do this too, calling women “targets” and places where they live and hang out “marketplaces.” It’s a spectrum, to be sure, but McKinlay’s worldview and the PUA worldview are two stops along it. Both seem to regard women as abstract prizes for clever wordplay or, as it may be, skilled coding. Neither seems particularly aware of, or concerned with, what happens after simply getting a woman to say yes.”

So, again, it’s not just men who do this. Women who are ABSOLUTELY OBSESSED WITH FINDING MR. RIGHT also do this. They stop thinking about men as people and start thinking of them as bundles of attributes. You have to be tall! And weigh more than me! And culturally Jewish!

If you want to think about this more, and how deeply damaging it is to society and our concepts of ourselves and our expectations of the future, not to mention how we perceive children, then take a look at the book Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation. It’s super fascinating.

So there you go, a long answer to a short question.

One last thing: I’m not saying that you should give up on your own algorithms and trust OKCupid’s algorithms. Far from it! I just think that the key thing is to stay human. Plus all online dating sites are asking the wrong questions, as I mentioned here.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m about to start a PhD in Math at a top-ranked place. I’m pretty sure I won’t end up in academia for a variety of personal reasons (mostly that my partner is a non-academic with a job that needs to be in New York, SF, or DC). What should I be doing my first year/summer to make sure I’m in a reasonably good place for a non-academic job hunt 5 or 6 years from now?

(And to make matters more complicated, both finance and government creep me out morally, but I really want to end up somewhere with some fun, interesting mathematics.)

Higher Education, Less Professionalism

Dear HELP,

Nice sign-off!

Make sure you know how to code, make sure you know how it feels to work in a company, make sure you keep your eye on what makes you feel moral and useful and interested. Oh, and read my book! I wrote it for people like you.

By the way, I’m hoping that, by the time you finish your Ph.D., there are better non-academic jobs out there for morally centered people with math skills. I’m just feeling optimistic today, I can’t explain it.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

With data science hype at an all-time high (and rising), I’ve been hearing of more and more people who are deciding to make a career change to data science. These acquaintances are smart, science-minded people, but without any background in advanced math, statistics, or computer science. An example background would be a bachelors degree in Chemistry. They are planning to take a few online courses, or a semester-long course or two, and then enter the job market.

My question is, do you think there’s a place for “data scientists” like these? Who’ve learned all the programming/machine learning/statistics they can in 3 months part-time but nothing beyond that? As someone with a strong technical background, I am skeptical that data scientists can be successfully churned out so quickly. Then again, if the hype is all it’s hyped up to be, maybe they’ll all get great jobs. Wondering what your take is.

Sincerely,

Some Kooky Elitist Person Trying to Intuit Climate

Dear SKEPTIC,

Niiiiice sign-off! I am super proud.

Two things. First, I certainly believe that anyone who has a high general level of intelligence and works hard can learn a new field diligently. So I don’t doubt the intentions or efforts of our chemist friends.

On the other hand, do data science jobs allow for follow-up training and – even more importantly – thinking? I’m guessing some do but most don’t. So yes, I agree that for many of these people, it’s a disappointment waiting to happen. And yes, certainly 3 months training does very little. At best you can start thinking a new way, but it’s up to you to actually make things happen with that new mindset.

They might find out their job is really nothing like the job they thought they had. They might end up being excel or SQL database monkeys, or they might find out their job is a front so that the company can claim to be doing “data science.” Worst case they’re asked to audit and approve models they don’t understand which are being used in a predatory manner so they’re on the hook when shit gets real.

On the other hand, what are the options really? It’s a new field and there’s no major for it (UPDATE: there are post-bacc programs popping up everywhere, for example here and here). This is what new fields look like, a bunch of amateurs coming together trying to figure out what they’re doing. Sometimes it works brilliantly and sometimes it produces frauds who ride the hype wave because they’re good at that.

In short, stay skeptical but don’t presume that your friends and acquaintances have bad intent. Ask them probing questions, when you see them, about which above scenario they’re in, it might help them figure it out for themselves. Unless that’s creepy and/or obnoxious.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How useful do you think “generate-and-test” results are? I am searching for good parameter settings using recent history from the last twelve days. For example, I just checked the report that is being generated and saw successful results eight times out of twelve. I actually could run a check against history, not including the last result and see how often the next result is good. Is this crazy or what?

Sleepless in Mesquite

Dear Sleepless,

I have never heard of “generate and test” so I googled it and found this, which honestly seems ridiculous for the following reason: how will you ever know your “solution” works?

So there is an example where it will work that illustrates my overall point. If you know that you have a line (“the solution”) and you know two (different) points that are on that line, then once you find a line with those points you know you’ve found the solution, because it’s unique.