Archive

Online learning promotes passivity

Up til I took Andrew Ng’s online machine learning class last semester, I had two worries about the concept of online learning. First, I worried that the inability to ask questions would be a major problem. Second, I worried about the possibility of building up material. I could imagine learning a given thing online but the ability to sustain and build material over an entire semester seemed kind of unrealistic.

On the second point, I think I’m convinced. Andrew definitely taught us a real semester’s worth of stuff, and he built up a body of knowledge very well. I now communicate with my colleagues at work using the language he taught us, which is very cool.

On the first point about asking questions, however, I am even more convinced there’s a crucial problem.

I want to differentiate between two different kinds of questions to make my point. First, there’s the “I’m confused” type of question, where someone literally doesn’t get the point of something or doesn’t understand the notation or a step in an explanation.

One can imagine tackling this kind of question in various ways. For example, one can strive to be a really good teacher, which Andrew certainly is, or to explain things at a high level but shove the details into black boxes, which Andrew did quite a bit (somewhat to my disappointment, especially when linear algebra was involved). If neither of those two things is sufficient, and the class is really important and/or really common, one can imagine teaching a computer to anticipate confusion and to ask questions along the way to make sure the students are following, and to go back and explain things in a different way if not.

In other words, the first kind of “clarifying questions” can probably be dealt with by the online learning community over time.

But there’s a second kind, namely the kind of question where someone is not confused but rather asks a question for one of the following reasons:

- they want to know how a certain idea relates to something else they know about,

- they want to generalize something the teacher said,

- they want to argue against an approach or for another approach,

- they see a mistake, or

- they see an easier way to do something.

Almost by definition, the above kinds of questions aren’t anticipated by the teacher, but the fact that they are asked almost always improves the class, certainly for the student in question but also for the other students and the teacher.

For example, one semester I taught three sections of 18.03 (exhausting! and I was pregnant!), which is a calculus class at M.I.T., and I remember thinking that in every single class one of the students made a remark or asked a question that I learned something from. It got to the point that, the third time through the same material, I’d be waiting for someone to explain how I should be teaching it. I loved that the students there are so smart but also so engaged in learning.

And that’s what I’m worried about- the engagement. When you embark on an online class, the best you can hope for is that you learn something and that you don’t get hopelessly confused. And that’s cool, that you can learn something, for free, online. But what you can’t do is what I’m worried about, and that’s to get instant feedback and discussion about some idea you had in the categories above.

I’m definitely one of those people who asks questions of the second type, and although I may sometimes annoy my fellow students, I really feel like the active engagement I pursue by coming up with all sorts of crazy comments and ideas and questions is what made me capable of doing original and creative things. For me, the most important part of my education was that training whereby I got to ask questions in class and got smart teachers who liked me to do so and would talk to me about my ideas.

How can that possibly happen with online learning? I’m afraid it can’t, and I’m afraid we will be training people to receive information rather than to engage in creation.

I imagine that in 200 years, almost everyone will be taught online, hooked into the machine and pumped up with knowledge. It will be only the elites who will have access to real live people to teach them in person, where they will be taught not only the material but also how to argue against a point of view and to propose an alternate approach.

How to teach someone how to prove something

In a couple of my posts (most recently here), I’ve talked about the need for a course early on in undergraduate math classes on proof techniques.

The goals of the class are two-fold: first, teach the students basic skills, and second demystify the concept of proof. The students should come away from the class thinking, no it’s not magic, and I’ve learned how to do this stuff, and there are a few basic techniques which seem to come in handy.

Today I want to go further into what a curriculum for such a course might look like.

And I will, in a moment, but first I want to explain something. It’s actually a really important and dangerous question, how to teach such a course, because it could go wildly wrong, and sometimes does. From my commenter Jordan:

… “Numbers, Equations, and Proofs,” which I started at Princeton in 2002 and which is still going as well. Though here’s an interview with a dude who was an ace math competition dude and found the course so hard as to drive him out of the math major! So maybe it’s no longer as “for everyone” as I designed it to be….

This struck me, how perverted Jordan’s class became. For that matter, Math 55 at Harvard could have started out as a good idea as well, but by the time I got to Harvard as a grad student it was the reason so few math majors ever stuck at Harvard and why there were especially few women.

I remember Noam Elkies taught it while I was there and was famous for asking questions in class and getting students to compete to answer them quickly. It makes sense that he’d run a class like this, because he’s so fast and clever, and he’s naturally wondering, am I the fastest and clevererest of them all? But rather than a place where proof is demystified and people feel safe asking dumb questions, he’d created the polar opposite, a live quiz show of clever competition. Ew!

In order to combat this downfall and decay, I think the class needs to have a clearly stated mission as well as built-in curriculum requirements that works against ostentatious displays of cleverness, which indeed only serve to further the “I got it but you don’t” stereotype of math skills (but which mathematicians themselves are incentivized to further since that magical aura comes in handy).

For example, when I taught it, I let the students hand in homework again and again until they got a score they liked. Of course, this depending on me having an awesome grader (and a relatively small class), which luckily I had.

Also, I asked each student to give a presentation to the class on some proof they particularly enjoyed, and I sat through a preview of their presentation and gave them extensive advice on board work and eye contact, which took a lot of work but really helped them prepare and also boosted their egos while at the same time increased their sympathy with each other and with me.

But of course the most important thing was that I clearly stated at the beginning of each class in the first two weeks that proving things in math was a skill like any other that you get good at through practice. And when I left Barnard Dusa McDuff took over the class and still teaches it, so I know it’s in good hands.

If I hadn’t had Dusa, I’d probably have written a manifesto to be given to each person who would teach the class after me. Of course anyone could have just thrown that away but it’s an idea.

As for content, I taught them really basic proof techniques, so induction, proof by contradiction, the pigeon-hole principle, and some epsilon-delta practice. We covered some basic logic, graph theory, group theory, ordinals, and basic analysis. We constructed the reals two ways and the complex numbers once and talked for a long time about whether “i” is real and what that even means. We used A Transition to Higher Mathematics, which I recommend with a few reservations (please tell me if you’ve found a better text for something like this!).

Everything was done super explicitly and carefully, no rushing. I said things three times in three different ways. I wasn’t expecting people to be fast or clever, because I know intelligence works in different ways and that this stuff was completely new to most of the students. And at least one student in the class, who had been an artist, is now a grad student in math at Berkeley.

Looking over my post I realize I spent way more time talking about the tone of the class than the content, but that’s totally appropriate, since I think of this class as an introduction to the culture of mathematics (or rather the culture I wish we had) just as much as mathematics itself.

After all, there really is no time limit on good ideas, and you do get to do it over if you make a mistake, and going over things slowly gives you more time to ask good questions and find mistakes.

On the making of a girl nerd

Today I want to discuss the process by which girls become math and cs nerds.

I could be tempted to talk primarily about my own story, since I’m a huge nerd. And I will talk about my story, but my focus is going to be on the girls of my generation who could have become nerds but didn’t. I’m hoping we can learn some lessons so that future generations will have more nerd girls.

Both my parents are nerds. My mother has a Ph.D. in applied math and my father has a Ph.D. in pure math. Moreover, I was on the math team in high school, found out about a math camp, and went to it for two summers, with the full support of my family.

I want to go over these details again, because I want to point out that they gave me an enormous advantage to becoming a successful nerd.

First, my parents being nerds: I have found an amazing correlation between women with math Ph.D.’s and women whose fathers are mathematicians. I don’t think this is random- indeed I think it means two things. First, that girls with mathematician dads have an easy time imagining themselves as mathematicians (and an even easier time if their mom is too). Second, that girls without mathematician dads don’t. Otherwise you wouldn’t be able to explain the statistics I have.

Second, the math camp experience. I went to math camp in spite of it being an extremely uncool summer endeavor, according to my classmates at school. Yet I didn’t care, and went anyway, mostly because I was already a complete outsider, a fat girl on the math team (but a mathbabe when I got there!).

Two things about this. First, most smart girls around me in Lexington High School, and there were a lot of them, would not have been willing to go to math camp and ruin their reputations. Most of them were relatively popular, and wanted to keep it that way. I had nothing to lose in that aspect and knew it. This kind of thinking may seem silly to us as grownups but seemed like life or death choices then.

Second, the advantage having been to math camp gave me when I got to college was phenomenal. I knew how to prove things by induction, by contradiction, and using the pigeon-hole principle. I knew basic group theory, graph theory, and real analysis. This gave me a jump-start in all of my undergrad math major classes. I was an elite, and what I could do seemed like magic to the kids who were math majors who didn’t know that stuff.

The thing about math is that people get into this mindset about being good at it: they think that you either have it or you don’t (see this post for more on the mindset). So the experience for the other kids, boys and girls, going to an algebra class and sitting next to me and a few other kids from math camp backgrounds was understandably intimidating and made them think they couldn’t compete. But I believe that, considering the social constructs and the kind of confidence girls and boys are trained to have (or not have), it was particularly daunting for other girls to see their competition in a small group of elite nerds who already knew all the answers.

I’m not advocating closing math camps. In fact, I am going back to teach at my high school math camp in July for three weeks (woohoo!). What I am advocating is thinking seriously about the selection process for young nerds and how much it weeds out girls. We can do better.

For example, Harvey Mudd is doing better by careful thought and attention to the issue. Namely, they are changing the introduction to programming class to be more appealing for non-math-or-cs-camp nerds. From the New York Times article:

Known as CS 5, the course focused on hard-core programming, appealing to a particular kind of student — young men, already seasoned programmers, who dominated the class. This only reinforced the women’s sense that computer science was for geeky know-it-alls.

“Most of the female students were unwilling to go on in computer science because of the stereotypes they had grown up with,” said Zachary Dodds, a computer scientist at Mudd. “We realized we were helping perpetuate that by teaching such a standard course.”

To reduce the intimidation factor, the course was divided into two sections — “gold,” for those with no prior experience, and “black” for everyone else. Java, a notoriously opaque programming language, was replaced by a more accessible language called Python. And the focus of the course changed to computational approaches to solving problems across science.

This sounds like a brilliant idea, and one that we should all consider (and python rocks!). It is reminiscent of the “Introduction to Proofs” class which I started with Karen Edwards and Sara Robinson in 1993 at UC Berkeley as an undergrad and which is still going, as well as the class I started at in 2006 at Barnard College, which is also still going. The dual goals of such a class are to teach basic proof techniques to people interested in the major (who probably didn’t go to math camp) and to show people that being able to prove things isn’t magic, it just takes practice and knowing techniques.

Let’s get more campuses across the country to think about all the math and cs nerds they are missing out on by teaching the same old math (or cs) major classes every year. This is a curriculum change that is easy, fun to teach, and completely worthwhile.

VAM versus what?

A few astute readers pointed out to me that in the past few days I both slammed the Value-added teacher’s model (VAM) and complained about people who reject something without providing an alternative. Good point, and today I’d like to start that discussion.

What should we be doing instead of VAM?

First of all, I do think that not rating teachers at all is better than the current system. So my “compare the the status quo” argument goes through in this instance. Namely, VAM is actively discouraging teachers whereas leaving them alone entirely would neither discourage or encourage anyone. So better than this.

At the same time, I am a realist, and I think there should be, ultimately, a system of evaluating teachers, just as there is a system for evaluating me at work. The difference between my workplace, of 45 people, and the NYC public schools is scale. It makes sense to have a very large and consistent evaluation system in the NYC public schools, whereas my job can have an ad hoc inconsistent system without it being a problem.

There’s another problem which is nearly impossible to tease from this discussion. Namely, the fact that what’s going on in NYC is a disingenuous political game between Bloomberg and the teacher’s union. Just to emphasize how important that fight is, let’s keep in mind that as of now, although the union is much weaker than it historically has been, it still has the tenure system. So any model, VAM or not, of evaluation is somewhat irrelevant for “removing bad teachers” given that they have tenure and tenure still means something.

Probably the best way to decouple the “Bloomberg vs. union/tenure” issue (a massive one here in NYC) from the “VAM versus other” question is to think nationally rather than citywide.

The truth is, the VAM is being tried out all over the country (although I don’t have hard numbers on this) and the momentum is for it to be used more and more. I predict within 10 years it will be done systematically everywhere in the country.

And, sadly, that’s kind of my prediction whether or not the underlying model is any good or not! The truth is, there is a large contingent of technocrats who want control over the evaluation system and believe in the models, whether or not they are producing pure noise or not. In other words, they believe in “data driven decisioning” as a holy grail even though there’s scant evidence that this will work in schools. And they also don’t want to back down now, even though the model sucks, because they feel like they’ll be losing momentum on the overall data-driven approach.

One thing I know for sure is that we should continue to be aware of how badly the current models are, and I want to set up an open source version of the models (see this post to get an idea how it could work) to exhibit that. In other words, even if we don’t turn off the models altogether, can’t we at least minimize their importance while their quality is bad? The first step is to plainly exhibit how bad they are.

It’s hard for me to decide what to do next, though. I’m essentially a modeler who is hugely skeptical of models. In fact, I don’t think using purely quantitative models to evaluate teachers is the right thing to do, period. Yet I feel like if it’s definitely going to happen, better for people like me to be in the middle of it, pointing out how bad the proposed (or in use) models are actually performing, and improving them.

One thing I know I’d do if I were to be put in charge of creating a better model: I’d train on data where the teacher is actually rated as a good teacher or not. In other words, I wouldn’t proxy “good teacher” by “if your students scored better than expected on tests”. A good model would be trained on data where there would be an expert teacher scorer, who would go into 500 classrooms and carefully evaluate the actual teachers, based on things like whether the teacher asked questions, or got the kids engaged, or talked too much or too little, or imposed too much busy work, etc. Then the model would be trying to mimic this expert.

Of course there are lots of really complicated issues to sort out- and they are *totally unavoidable*. This is why I’m so skeptical of models, by the way: people think you can simplify stuff when you actually can’t. There’s nothing simple about teaching and whether someone’s a good teacher. It’s just plain complex. A simple model will be losing too much information.

Here’s one. Different people think good teaching is different. A possible solution: maybe we could have 5 different “expert models” based on different people’s definitions of good teaching, and every teacher could be evaluated based on every model. Still need to find those 5 experts that teachers trust.

Here’s another. The kind of teacher-specific attributes collected for this test would be different from the VAM- things that happen inside a classroom (like percentage of time teacher talks vs. student, the tone of the discussion, the number and percentage of kids involved in the discussion, etc,) and are harder to capture accurately. These are technological hurdles that are hard.

I think one of the most important questions is whether we can come up with an evaluation system that would be sufficiently reasonable and transparent that the teachers themselves would get on board.

I’d to hear more ideas.

The Value Added Teacher Model Sucks

Today I want you to read this post (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg) written by Gary Rubinstein, which is the post I would have written if I’d had time and had known that they released the actual Value-added Model scores to the public in machine readable format here.

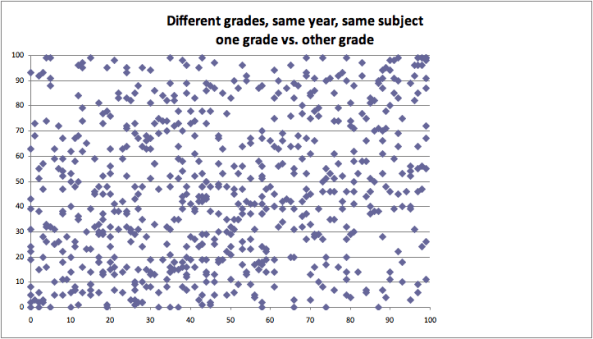

If you’re a total lazy-ass and can’t get yourself to click on that link, here’s a sound bite takeaway: a scatter plot of scores for the same teacher, in the same year, teaching the same subject to kids in different grades. So, for example, a teacher might teach math to 6th graders and to 7th graders and get two different scores; how different are those scores? Here’s how different:

Yeah, so basically random. In fact a correlation of 24%. This is an embarrassment, people, and we cannot let this be how we decide whether a teacher gets tenure or how shamed a person gets in a newspaper article.

Just imagine if you got publicly humiliated by a model with that kind of noise which was purportedly evaluating your work, which you had no view into and thus you couldn’t argue against.

I’d love to get a meeting with Bloomberg and show him this scatter plot. I might also ask him why, if his administration is indeed so excited about “transparency,” do they release the scores but not the model itself, and why they refuse to release police reports at all.

Open Models (part 2)

In my first post about open models, I argued that something needs to be done but I didn’t really say what.

This morning I want to outline how I see an open model platform working, although I won’t be able to resist mentioning a few more reasons we urgently need this kind of thing to happen.

The idea is for the platform to have easy interfaces both for modelers and for users. I’ll tackle these one at a time.

Modeler

Say I’m a modeler. I just wrote a paper on something that used a model, and I want to open source my model so that people can see how it works. I go to this open source platform and I click on “new model”. It asks for source code, as well as which version of which open source language (and exactly which packages) it’s written in. I feed it the code.

It then asks for the data and I either upload the data or I give it a url which tells the platform the location of the data. I also need to explain to the platform exactly how to transform the data, if at all, to prepare it for feeding to the model. This may require code as well.

Next, I specify the extent to which the data needs to stay anonymous (hopefully not at all, but sometimes in the case of medical data or something, I need to place security around the data). These anonymity limits will translate into the kinds of visualizations and results that can be requested by users but not the overall model’s aggregated results.

Finally, I specify which parameters in my model were obvious “choices” (like tuning parameters, or prior strengths, or thresholds I chose for cleaning data). This is helpful but not necessary, since other people will be able to come along later and add things. Specifically, they might try out new things like how many signals to use, which ones to use, and how to normalize various signals.

That’s it, I’m done, and just to be sure I “play” the model and make sure that the results jive with my published paper. There’s a suite of visualization tools and metrics of success built into the model platform for me to choose from which emphasize the good news for my model. I’ve created an instance of my model which is available for anyone to take a look at. This alone would be major progress, and the technology already exists for some languages.

User

Now say I’m a user. First of all, I want to be able to retrain the model and confirm the results, or see a record that this has already been done.

Next, I want to be able to see how the model predicts a given set of input data (that I supply). Specifically, if I’m a teacher and this is the open-sourced value added teacher model, I’d like to see how my score would have varied if I’d had 3 fewer students or they had had free school lunches or if I’d been teaching in a different district. If there were a bunch of different models, I could see what scores my data would have produced in different cities or different years in my city. This is a good start for a robustness test for such models.

If I’m also a modeler, I’d like to be able to play with the model itself. For example, I’d like to tweak the choices that have been made by the original modeler and retrain the model, seeing how different the results are. I’d like to be able to provide new data, or a new url for data, along with instructions for using the data, to see how this model would fare on new training data. Or I’d like to think of this new data as updating the model.

This way I get to confirm the results of the model, but also see how robust the model is under various conditions. If the overall result holds only when you exclude certain outliers and have a specific prior strength, that’s not good news.

I can also change the model more fundamentally. I can make a copy of the model, and add another predictor from the data or from new data, and retrain the model and see how this new model performs. I can change the way the data is normalized. I can visualize the results in an entirely different way. Or whatever.

Depending on the anonymity constraints of the original data, there are things I may not be able to ask as a user. However, most aggregated results should be allowed. Specifically, the final model with its coefficients.

Records

As a user, when I play with a model, there is an anonymous record kept of what I’ve done, which I can choose to put my name on. On the one hand this is useful for users because if I’m a teacher, I can fiddle with my data and see how my score changes under various conditions, and if it changes radically, I have a way of referencing this when I write my op-ed in the New York Times. If I’m a scientist trying to make a specific point about some published result, there’s a way for me to reference my work.

On the other hand this is useful for the original modelers, because if someone comes along and improves my model, then I have a way of seeing how they did it. This is a way to crowdsource modeling.

Note that this is possible even if the data itself is anonymous, because everyone in sight could just be playing with the model itself and only have metadata information.

More on why we need this

First, I really think we need a better credit rating system, and so do some guys in Europe. From the New York Times article (emphasis mine):

Last November, the European Commission proposed laws to regulate the ratings agencies, outlining measures to increase transparency, to reduce the bloc’s dependence on ratings and to tackle conflicts of interest in the sector.

But it’s not just finance that needs this. The entirety of science publishing is in need of more transparent models. From the nature article’s abstract:

Scientific communication relies on evidence that cannot be entirely included in publications, but the rise of computational science has added a new layer of inaccessibility. Although it is now accepted that data should be made available on request, the current regulations regarding the availability of software are inconsistent. We argue that, with some exceptions, anything less than the release of source programs is intolerable for results that depend on computation. The vagaries of hardware, software and natural language will always ensure that exact reproducibility remains uncertain, but withholding code increases the chances that efforts to reproduce results will fail.

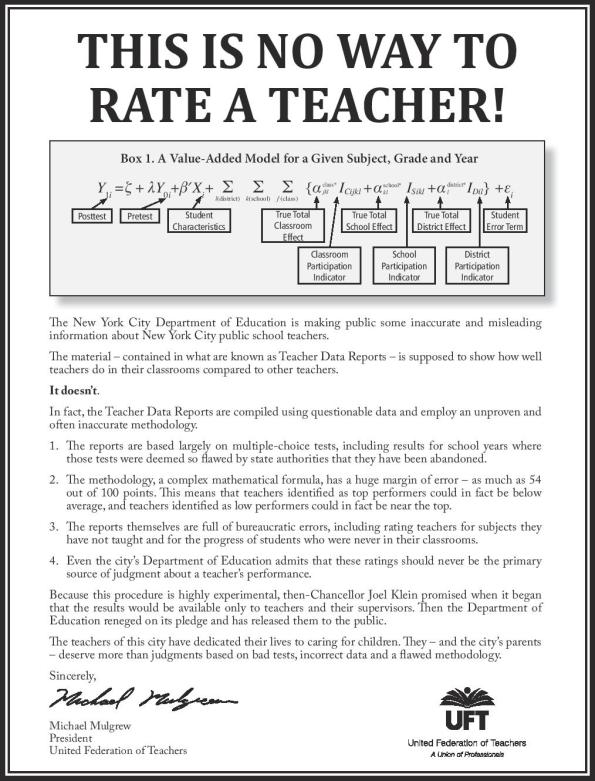

Finally, the field of education is going through a revolution, and it’s not all good. Teachers are being humiliated and shamed by weak models, which very few people actually understand. Here’s what the teacher’s union has just put out to prove this point:

Math teaching needs overhaul

My friend Tara sent me a message:

The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology submitted a report on the challenge to producing more college graduates with STEM degrees. In particular, they point out mathematics as a bottleneck, and recommend (on p. 29) that “teaching and curricula [be] developed and taught by faculty from mathematics-intensive disciplines other than mathematics, including physics, engineering, and computer science.” Of course, there are physicists, engineers, and computer scientists on the Council, whereas there is no mathematician.

On some level, they do have a point. They seem to say that we (as a nation) are not doing a good job of teaching K12 mathematics. I strongly disagree with their conclusion that we should therefore take the college-level teaching of mathematics away from the experts in mathematics.

Hmm. I don’t know. I’ve been sounding a warning for a while now that math departments are way too complacent about the way they teach undergrads. I try to make people think of a math department as, to some extent, a brand, and that we should be trying to attract good majors and we should be trying to get more people psyched about math. To that end I am constantly trying to get people to care about the calculus curriculum, which is always at risk of being taken over by the physics, engineering, and economics departments, and I’ve consistently introduced “introduction to higher math” courses which explicitly teach proof techniques.

But there’s a major problem, at least in the very top research departments. Namely, the professors actually think math should be a hard and elite major, and that gives them an excuse to not care about the quality of the undergrad classes. That’s not how they say it, of course, but my experience is that’s how it works.

The other reason I think it makes sense to be a bit concerned about the brand is that if we mathematicians don’t start doing it, then someone else will start doing it for us. This President’s Council of Advisors report is exactly saying that. On the one hand it could be the kick in the ass that math departments need, but on the other hand considering how much reporting they are asking for, it could mean a tremendous amount of paperwork as well as a loss of independence of the math community.

I say mathematicians respond to this by admitting there’s a problem and coming up with a good plan that they organize and control. Otherwise I do think something else will and should be done.

Interestingly, there also seems to be a call in this report for more good math tutors. It reminds me of a commenter from yesterday who wants to start something called “Tutor for America”, which I think is an excellent idea.

Teaching scores released

Anyone who reads this blog regularly knows how detestable I think it is that the teacher value-added model scores are being released but the underlying model is not.

We are being shown scores of teachers and we are even told the scores have a wide margin of error: someone who gets a 30 out of 100 could next year get a 70 out of 100 and nobody would be surprised (see this article).

Just to be clear, the underlying test doesn’t actually use a definition of a good teacher beyond what the score is. In other words, this model isn’t being trained by looking at examples of what is a “good teacher”. Instead, it derived from another model which predicts students’ test scores taking into account various factors. At the very most you can say the teacher model measures the ability teachers have to get their kids to score better or worse than expected on some standardized tests. Call it a “teaching to the test model”. Nothing about learning outside the test. Nothing about inspiring their students or being a role model or teaching how to think or preparing for college.

A “wide margin of error” on this value-added model then means they have trouble actually deciding if you are good at teaching to the test or not. It’s an incredibly noisy number and is affected by things like whether this year’s standardized tests were similar to last year’s.

Moreover, for an individual teacher with an actual score, being told there’s a wide margin of error is not helpful at all. On the other hand, if the model were open source (and hopefully the individual scores not public), then a given teacher could actually see their margin of error directly: it could even be spun as a way of seeing how to “improve”. Otherwise said, we’d actually be giving teachers tools to work with such a model, rather than simply making them targets.

update: Here’s an important comment from a friend of mine who works directly with New York City math teachers:

Thanks for commenting on this. I work with lots of public school math teachers around New York City, and have a sense of which of them are incredible teachers who inspire their students to learn, and which are effective at teaching to the test and managing their behavior.

Curiosity drove me to it, but I checked out their ratings. The results are disappointing and discouraging. The ones who are sending off intellectually engaged children to high schools were generally rated average or below, while the ones who are great classroom managers and prepare their lessons with priority to the tests were mostly rated as effective or above.

Besides the huge margin of uncertainty in this model, it’s clear that it misses many dimensions of great teaching. Worse, this model, now published, is an incentive for teachers to develop their style even more towards the tests.

If you don’t believe me or Japheth, listen to Bill Gates, who is against publicly shaming teachers (but loves the models). From his New York Times op-ed from last week:

Many districts and states are trying to move toward better personnel systems for evaluation and improvement. Unfortunately, some education advocates in New York, Los Angeles and other cities are claiming that a good personnel system can be based on ranking teachers according to their “value-added rating” — a measurement of their impact on students’ test scores — and publicizing the names and rankings online and in the media. But shaming poorly performing teachers doesn’t fix the problem because it doesn’t give them specific feedback.

If nothing else, the Bloomberg administration should also look into statistics regarding whether it’s become a more attractive or less attractive profession since he started publicly shaming teachers. Has introducing the models and publicly displaying the results had the intended effect of keeping good teachers and getting rid of bad ones, Mayor Bloomberg?

Why I love nerds

What is it that grad students do all day? Well if you’re Zachary Abel in the M.I.T. math department, then the answer may be that you fiddle with paperclips and make awesome nerdy and beautiful sculpture (I found his page through the God Plays Dice blog). Here’s my favorite sculpture from his site:

Be sure to read the explanations he gives of the things he’s made, they are very cool and sometimes comes with animation.

A modeled student

There’s a recent article from Inside Higher Ed (hat tip David Madigan) which focuses on a new “Predictive Analytics Reporting Framework” that tracks students’ online learning and predicts their outcomes, like whether they will finish the classes they’re taking or drop out. Who’s involved? The University of Phoenix among others:

A broad range of institutions (see factbox) are participating. Six major for-profits, research universities and community colleges — the sort of group that doesn’t always play nice — are sharing the vault of information and tips on how to put the data to work.

I don’t know about you but I’ve read the wikipedia article about for-profit universities and I don’t have a great feeling about their goals. In the “2010 Pell Grant Fraud controversy” section you can find this:

Out of the fifteen sampled, all were found to have engaged in deceptive practices, improperly promising unrealistically high pay for graduating students, and four engaged in outright fraud, per a GAO report released at a hearing of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee held on August 4, 2010.[28]

Anyhoo, back to the article. They track people online and make suggestions for what classes people may want to take:

The data set has the potential to give institutions sophisticated information about small subsets of students – such as which academic programs are best suited for a 25-year-old male Latino with strength in mathematics, for example. The tool could even become a sort of Match.com for students and online universities, Ice said.

That makes me wonder- what would I have been told to do as a white woman with strength in math, if such a program had existed when I went to college? Maybe I would have been pushed to become something that historical data said I’d be best suited for? Maybe something safe, like actuarial work? What if this had existed when my mother was at MIT in applied math in the early ’60’s? Would they have had a suggestion for her?

Aside from snide remarks, let me make two direct complaints about this idea. First, I despise the idea of funneling people into chutes and ladders-type career projections based on their external attributes rather than their internal motives and desires. This kind of model, which as all models is based on historical data, is potentially a way to formally adopt racist and sexist policies. It codifies discrimination.

The second complaint: this is really all about money. In the article they mention that the model has already helped them decide whether Pell grants are being issued to students “correctly”:

Students can only receive the maximum Pell Grant award when they take 12 credit hours, which “forces people into concurrency,” said Phil Ice, vice president of research and development for the American Public University System and the project’s lead investigator. “So the question becomes, is the current federal financial aid structure actually setting these individuals up for failure?”

In other words, it looks like they are going to try to use the results of this model to persuade the government to change the way Pell Grants are distributed. Now, I’m not saying that the Pell Grant program is perfect; maybe it should be changed. But I am saying that this model is all about money and helping these online universities figure out which students will be most profitable. I’m familiar with constructing such models, because I was a quant at a hedge fund once and I know how these guys think. You can bet this model is proprietary, too- you wouldn’t want people to see into how they are being funneled too much, it might get awkward.

The article doesn’t she away from such comparisons either. From the article:

The project appears to have built support in higher education for the broader use of Wall Street-style slicing and dicing of data. Colleges have resisted those practices in the past, perhaps because some educators have viewed “data snooping” warily. That may be changing, observers said, as the project is showing that big data isn’t just good for hedge funds.

Just to be clear, they are saying it’s also good for for-profit institutions, not necessarily the students in them.

I’d like to see a law passed that forced such models to be open-sourced at the very very least. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding this, who know how to reach those guys to make this request?

New online course: model thinking

There’s a new course starting soon, taught by Scott Page, about “model thinking” (hat tip David Laxer). The course web site is located here and some preview lectures are here. From the course description:

In this class, I present a starter kit of models: I start with models of tipping points. I move on to cover models explain the wisdom of crowds, models that show why some countries are rich and some are poor, and models that help unpack the strategic decisions of firm and politicians.

The models cover in this class provide a foundation for future social science classes, whether they be in economics, political science, business, or sociology. Mastering this material will give you a huge leg up in advanced courses. They also help you in life.

In other words, this guy is seriously ambitious. Usually around people who are this into modeling I get incredibly suspicious and skeptical, and this is no exception. I’ve watched the first two videos and I’ve come across the following phrases:

- Models make us think better

- Models are better than we are

- Models make us humble

The third one is particularly strange since his evidence that models make us humble seems to come from the Dutch tulip craze, where a linear model of price growth was proven wrong, and the recent housing boom, where people who modeled housing prices as always going up (i.e. most people) were wrong.

I think I would have replaced the above with the following:

- Models can make us come to faster conclusions, which can work as rules of thumb, but beware of when you are misapplying such shortcuts

- Models make us think we are better than we actually are: beware of overconfidence in what is probably a ridiculous oversimplification of what may be a complicated real-world situation

- Models sometimes fail spectacularly, and our overconfidence and misapplication of models helps them do so.

So in other words I’m looking forward to disagreeing with this guy a lot.

He seems really nice, by the way.

I should also mention that in spite of anticipating disagreeing fervently with this guy, I think what Coursera is doing by putting up online courses is totally cool. Check out some of their other offerings here.

Women in math

This is crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

A study recently came out which was entitled “Can stereotype threat explain the gender gap in mathematics performance and achievement?”. One of the authors created and posted a video describing the paper, which you can view here.

As a preview, there seem to be four main points of the paper and the video:

- The papers on stereotype threat normalize with respect to SAT scores which is bad.

- Evidence for stereotype threat is therefore weak.

- We should therefore stop putting all of our resources into combating stereotype threat.

- We should instead do something easy like combating stereotypes themselves.

Before we go into the details of the paper, we need a bit of context. For that reason, this post is split into three parts. The first addresses a meta-issue, namely that of the “null hypothesis” in this discussion. A frustration that I have, and that I think is shared by many of the women I know in math, is that the (often unspoken) working hypothesis is that in fact women are just not as talented, and it is somehow up to us women to prove this otherwise, presumably by convincing men that we’re geniuses.

The authors of the above paper fall prey to this disingenuous line of thought, by proclaiming stereotype threat is an insufficient explanation but not offering any alternative explanations. This sets up a kind of implied false dichotomy: if it isn’t explained by such and such, it must mean girls are dumb.

Not only does this undermine serious intellectual debate, but it often turns people off from entering the debate in the first place, because they sense the manipulative nature of the discussion. But that’s a pity, since, with the correct assumption, namely that women and men have equal talents but things are holding back women, we could probably make lots of progress on what those things are.

The second part is directly related not to the paper but to the blog post which referenced the paper, which changed the conversation from “math performance gap” to the question of “why there are no women math geniuses”. This is an interesting twist, and in my opinion warrants addressing separately.

In the third part I argue directly against the paper and its conclusions.

1. The Null Hypothesis

Needless to say, I think the onus is on the scientific community to prove that women aren’t as mathematically talented as men. In other words, I do not accept the defensive position that I need to prove we are as smart: the null hypothesis is that a series of effects, one of them stereotype threat, explains any perceived difference in talent.

In his now famous lecture at NBER in 2005, Larry Summers putatively discusses the issue of why there are fewer tenured women in science and math departments at top universities. However, if you read the transcript, you will note that, when he gets to the “different availability of aptitude at the high end” part, he does us a favor of sorts by admitting what his underlying working hypothesis is: that girls aren’t as good at math. His argument using standard deviations of test scores is ridiculous, especially if you consider 1) how differently women do versus men on the same test in different conditions, 2) how much that difference has itself changed over time, and of course 3) the question of what the tests themselves are measuring.

To test why this null hypothesis is so damaging, my friend Catherine Good suggested the following thought experiment: imagine if he’d gone up to the podium and, instead of saying that women aren’t all that good at math and it was partly explained by when he’d given boyish toys to his twin girls that they took care of them instead of constructed things, he had instead substituted gender with race. Here’s the passage:

There may also be elements, by the way, of differing, there is some, particularly in some attributes, that bear on engineering, there is reasonably strong evidence of taste differences between little girls and little boys that are not easy to attribute to socialization. I just returned from Israel, where we had the opportunity to visit a kibbutz, and to spend some time talking about the history of the kibbutz movement, and it is really very striking to hear how the movement started with an absolute commitment, of a kind one doesn’t encounter in other places, that everybody was going to do the same jobs. Sometimes the women were going to fix the tractors, and the men were going to work in the nurseries, sometimes the men were going to fix the tractors and the women were going to work in the nurseries, and just under the pressure of what everyone wanted, in a hundred different kibbutzes, each one of which evolved, it all moved in the same direction. So, I think, while I would prefer to believe otherwise, I guess my experience with my two and a half year old twin daughters who were not given dolls and who were given trucks, and found themselves saying to each other, look, daddy truck is carrying the baby truck, tells me something. And I think it’s just something that you probably have to recognize.

It begs the question, why did the women in kibbutz quit working on tractors? The way Larry tells his story, he makes it clear he thinks that it’s because the women wanted it that way (thus his story about the twins). But surely it is as plausible that: 1) Men, having a vested interest in proving their manhood (which they do and in cultures around the world leads to certain types of work being seen as “manly”) weren’t keen about day care duty and/or 2) women were hesitant to cross the lines of gender stereotype (it might lead them to be perceived as being masculine, or even worse, emasculating). And it also isn’t hard to imagine that parents ooh and ahh more when small children play with what are perceived to be gender-appropriate toys and are quietly or even vocally uncomfortable when boys play with dolls and girls play with trucks.

One last word about the null hypothesis and why I’m so devoted to this issue: when I and two other girls (and, as it happens, no boys) in the 6th grade did well enough to go into a special, advanced 7th grade algebra class, my (female) teacher brought us up to the front of the room and told the three of us “I don’t see why you would challenge yourselves like this anyway since you are girls, and you won’t be needing math when you grow up.” I was the only one of the three of us to actually choose that class, and I was the only girl in the algebra class. One of my friends was one of two women in a class of 45 students studying artificial intelligence at Yale. She was expecting praise for being one of only two students to get a program to work on a particularly tough assignment. Instead, she was accused by the professor of stealing the code from her male classmate. She left the major. Until stories like this become rare, or even uncommon, I will assume that there’s too much cultural influence to figure out the real story.

Going back to Larry Summers, his lecture did two things: 1) it breathed new life into the age-old stereotype that women aren’t as good at math as men, and 2) it attributed that difference to an underlying innate ability difference- that is, he conveyed a “fixed ability mindset” regarding math (more on mindsets below). As the leader of an educational institution he introduced the two ideas that together are like a powder keg: they can undermine women’s feelings of belonging in math, which in turn informs their mathematics achievement and intrinsic motivation to remain in math.

Now more about Catherine Good. She talked at that same conference where Larry Summers put his foot in his mouth; in fact she was the speaker after Larry at that conference, and she was talking about her paper that gives evidence that the above “powder keg” message tends to push women out of math (but Larry didn’t stick around long enough to hear her talk, unfortunately). She is also an expert on stereotype threat and helped me look at the study. More on her thoughts below, but I still want to talk about the concept of “genius.”

2. Women and the concept of genius

Let’s define, as one of the commenters does from the blog, a “genius woman in math” to be any woman who has won a Fields Medal. Since there are no women who have won Fields Medals (versus 52 men), this is a pretty tight definition. I would argue, and I might in another post, that even without the above definition, the concept of “genius” is a social construct which is rarely if ever applied to women, except perhaps after they’re dead. Please comment with counterexamples if you know of any.

So here’s what I think. There are lots of reasons that women don’t win Fields Medals. I will name a few.

- Fields Medals are awarded to mathematicians under the age of 40, for some reason, and women mathematicians typically do good work into their retirement age, whereas men usually do their best work young (this also explains why Harvard has so much trouble hiring women- by the time they are convinced the woman is a genius, she’s 55 and has grandchildren and frankly probably sees the offer as tokenism).

- The commenter who defined a “math genius” as a Fields Medalist said that it would be an objective measure. But Fields Medals are awarded by a bunch of guys who decide what’s important and who’s responsible for the important results. In other words it’s a political process.

- Women don’t care as much about winning Fields Medals. This matters, because I know of men who explicitly worked on problems in order to win the Fields Medal (you know who you are). It’s a serious and bizarre case of narrow focus.

- Why is math genius defined so narrowly? I would personally define it more broadly (a topic for another post), and there’d be plenty of women geniuses. With my definition, though, I’d guess that women who are geniuses have lots of options and they often choose something they consider more personally rewarding than an academic job.

- Women’s intelligence may also manifest in different ways: note that most of the assholes on Wall Street are men. This kind of makes sense since women are typically not as driven by testosterone and competitiveness. This doesn’t mean they aren’t geniuses or that they couldn’t have done the work the men on Wall Street did (my experience proves that).

- The Fields Medal distorts the mathematical process itself, by implying that there’s a single superstar who swoops in and solves the problem that all the other people were incapable of doing. In fact mathematics as a field is an enormous collaboration, a scientific project, where everyone depends on the community around them for coming up with questions, defining the “interestingness” of questions, and giving context to results. The idea that there’s one winner out of all of this, or even one metric by which we could measure such a winner, is silly. See this post from Quomodocumque.

- Another point about genius (in any domain): research is showing that to truly express one’s genius takes thousands of hours of practice. So genius may be a latent trait but will never be expressed without many hours of hard work. This point is very often lost and is related to women in that their apparent geniusness depends to a large extent on how supportive their environment is for all that investment of time.

3. The paper against stereotype threat

I am finally ready to address (with Catherine’s help) the issues of the paper in question, which I will repeat:

- The papers on stereotype threat normalize with respect to SAT scores which is bad

In fact the author “discards” a bunch of stereotype threat studies on these grounds. However, it is totally standard to normalize with respect to some other metric (would you rather we didn’t normalize to anything?), and in fact it essentially penalizes the studies, since it has been shown that stereotype threat is in play even for the SATs. On the other hand, the standard for normalizing (this is called “including a covariate”) is that the groups being compared should not differ significantly in the covariate, presumably because it’s harder to argue that your are in fact correcting for that aspect. Because men and women sometimes do differ significantly in SAT scores, including them as covariates could be a technical violation of the rules of conducting a so-called ANCOVA.

Is this what the author is complaining about specifically? Did he, for example, check to see if the samples in the “discarded” studies actually differ in the covariate? It seems he’s making the assumption that they did, but it’s not clearly stated that they did. It’s certainly not a given that the men and women in these studies did differ in the covariate, and he needs to make that precise. If they did not, then there’s no valid argument against using SAT scores.

- Evidence for stereotype threat is therefore weak.

There is ample evidence that stereotype threat is very real. Keep in mind that the authors of this study have not shown evidence against stereotype threat, but have simply complained that they don’t like the existing studies for it. And their standard for what “replicates” the original study is overly stringent- they only wanted to include studies that found significant interactions between gender and condition. Interactions are easiest to find when you have a “crossover effect” (e.g. males are higher in condition A but lower in condition B), but often we find “span effects” in which the males and females may be equal in condition A but differ in condition B. This can also be an example of stereotype threat. For example, in a paper written by Catherine, she didn’t find a significant interaction (males and females performed equally in condition A) but when the stereotype threat was reduced, women outperformed men. To discount this and other studies as not providing evidence of stereotype threat simply because an “interaction” wasn’t found is playing games with statistics.

- We should therefore stop putting all of our resources into combating stereotype threat.

Nobody who studies stereotype threat claims it explains everything. It is part of a larger picture. The good news is that there are interventions for it (described below).

- We should instead do something easy like combating stereotypes themselves.

The idea that it’s “easy” to combat stereotypes is completely naive. There are tons of ways that stereotyping is understood to be very difficult, if not impossible, to get rid of. Some of them have to do with an evolutionary need to simplify first impressions of people (i.e. categorize) so that we can tell if they are an immediate threat to our safety. This may be the most baffling part of the whole thing, because the authors should really know better.

I want to end on a positive note, because the news is actually pretty good. There is a way to combat stereotype threat, and I’ve tried it and it works. To understand it, it helps to think about the way people think about intelligence itself. As a simplification, people either think that intelligence is fixed and rigid (you’re either born with it or you’re not) or they think that intelligence is malleable and can be learned and practiced.

It turns out that if someone believes the latter “malleable intelligence” view, then they work hard and are hopeful and stereotype threat is to a large extent alleviated. Whereas if they’re convinced of the former mindset for intelligence, the effect of stereotype threat is more pronounced. In situations where the stereotype is salient (“girls are bad at math” is salient when taking a math test), the situation itself can convey a mindset of fixed ability and all the hallmark responses that go along with that mindset then follow. To encourage a malleable view of intelligence can help combat that fixed view and thus the threat of the stereotype.

The way I used this information was as follows. I started a class in teaching proof techniques at Barnard College (there were both Barnard students and Columbia students in the class). At the beginning of every class for the first two weeks I described how mathematicians aren’t born knowing how to prove things, but rather they learn techniques, and practice them until they are proficient. Note I wasn’t directly confronting or addressing stereotypes, but rather setting up the mindset where the studies have shown stereotypes have less negative power.

The class went great, and is still going on. I will post soon about my experiences starting that class and others like it.

Data Science needs more pedagogy

Yesterday Flowing Data posted an article about the history of data science (h/t Chris Wiggins). Turns out the field and the name were around at least as early as 2001, and statistician William Cleveland was all about planning it. He broke the field down into parts thus:

- Multidisciplinary Investigation (25%) — collaboration with subject areas

- Models and Methods for Data (20%) — more traditional applied statistics

- Computing with Data (15%) — hardware, software, and algorithms

- Pedagogy (15%) — how to teach the subject

- Tool Evaluation (5%) — keeping track of new tech

- Theory (20%) — the math behind the data

First of all this is a great list, and super prescient for the time. In fact it’s an even better description of data science than what’s actually happening.

The post mentions that we probably don’t see that much theory, but I’ve certainly seen my share of theory when I go to Meetups and such. Most of the time the theory is launched into straight away and I’m on my phone googling terms for half of the talk.

The post also mentions we don’t see much pedagogy, and here I strongly concur. By “pedagogy” I’m not talking about just teaching other people what you did or how you came up with a model, but rather how you thought about modeling and why you made the decisions you did, what the context was for those decisions and what the other options were (that you thought of). It’s more of a philosophy of modeling.

It’s not hard to pinpoint why we don’t get much in the way of philosophy. The field is teeming with super nerds who are focused on the very cool model they wrote and the very nerdy open source package they used, combined with some weird insight they gained as a physics Ph.D. student somewhere. It’s hard enough to sort out their terminology, never mind expecting a coherent explanation with broad context, explained vocabulary, and confessed pitfalls. The good news is that some of them are super smart and they share specific ideas and sometimes even code (yum).

In other words, most data scientists (who make cool models) think and talk at the level of 0.02 feet, whereas pedagogy is something you actually need to step back to see. I’m not saying that no attempt is ever made at this, but my experiences have been pretty bad. Even a simple, thoughtful comparison of how different fields (bayesian statisticians, machine learners, or finance quants) go about doing the same thing (like cleaning data, or removing outliers, or choosing a bayesian prior strength) would be useful, and would lead to insights like, why do these field do it this way whereas those fields do it that way? Is it because of the nature of the problems they are trying to solve?

A good pedagogical foundation for data science will allow us to not go down the same dead end roads as each other, not introduce the same biases in multiple models, and will make the entire field more efficient and better at communicating. If you know of a good reference for something like this, please tell me.

Politics of teacher pay disguised as data science

I am super riled up about this report coming out of the Heritage Foundation. It’s part of a general trend of disguising a political agenda as data science. For some reason, this seems especially true in education.

The report claims to prove that public school teachers are overpaid. As proof of its true political goals, let me highlight a screen shot of the “summary” page (which has no technical details of the methods in the paper):

I’m sorry, but are you pre-writing my tweets for me now? Are you seriously suggesting that you have investigated the issue of public school teacher pay in an unbiased and professional manner with those pre-written tweets, Heritage Foundation?

If you read the report, which I haven’t had time to really do yet, you will notice how few equations there are, and how many words. I’m not saying that you need equations to explain math, but it sure helps when your goal is to be precise.

And I’d also like to say, shame on you, New York Times, for your coverage of this. You allow the voices of the authors, from the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, as well as another political voice from the Reason Foundation. But you didn’t ask a data scientist to look at the underlying method.

The truth is, you can make the numbers say whatever you want, and good data scientists (or quants, or statisticians) know this. The stuff they write in their report is almost certainly not the whole story, and it’s obviously politically motivated. I’d love to be hired to research their research and see what kind of similar results they’ve left out of the final paper.

Data Science and Engineering at Columbia?

Yesterday Columbia announced a proposal to build an Institutes for Data Sciences and Engineering a few blocks north of where I live. It’s part of the Bloomberg Administration’s call for proposals to add more engineering and entrepreneurship in New York City, and he’s said the city is willing to chip in up to 100 million dollars for a good plan. Columbia’s plan calls for having five centers within the institute:

- New Media Center (journalism, advertising, social media stuff)

- Smart Cities Center (urban green infrastructure including traffic pattern stuff)

- Health Analytics Center (mining electronic health records)

- Cybersecurity Center (keeping data secure and private)

- Financial Analytics Center (mining financial data)

A few comments. Currently the data involved in media 1) and finance 5) costs real money, although I guess Bloomerg can help Columbia get a good deal on Bloomberg data. On the other hand, urban traffic data 2) and health data 3) should be pretty accessible to academic researchers in New York.

There’s a reason that 1) and 5) cost money: they make money. The security center is kind of in the middle, since you can try to make any data secure, you don’t need to particularly pay for it, but on the other hand if you can find a good security system then people will pay for it.

On the other hand, even though it’s a great idea to understand urban infrastructure and health data, it’s not particularly profitable (not to say it doesn’t save alot of money potentially, but it’s hard to monetize the concept of saving money, especially if it’s the government’s or the city’s money).

So the overall cost structure of the proposed Institute would probably work like this: incubator companies from 1) and 5) and maybe 4) fund the research going on in (themselves and) 2) and 3). This is actually a pretty good system, because we really do need some serious health analytics research on an enormous scale, and it needs to be done ethically.

Speaking of ethics, I hope they formalize and follow The Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath. In fact, if they end up building this institute, I hope they have a required ethics course for all incoming students (and maybe professors).

Hmmm… I’d better get my “data science curriculum” plan together fast.

First day of calculus class

Last night I had dinner with a friend who is a post-doc in math, and she was mentioning that her students, especially in the lower-level calculus classes, generally don’t refer to her as “professor.” This would be fine since she’s not yet a professor, but she also mentioned they do refer to graduate student men in the same department as professor. She’s a young looking woman, and my guess is they simply don’t know better. Here’s what my advice to her was (and as usual, I’d give this advice to both men and women).

On the first day of class, introduce yourself and put your name on the board, explain when and where you got a Ph.D., what your field of research is, what your current job is, as well as office hours and homework policies. In addition, wear a button-down shirt that first day of class. It’s kind of ridiculous but it works, in the sense that the students will be more impressed with you, which translates into them behaving more respectfully.

Moreover, it’s totally appropriate and not manipulative to explain your credentials. It’s probably most important for calculus, because generally those students don’t really want to be there, at least not all of them. Upper level classes contain students who are more psyched about math and eager to like their professors. I say this partly from experience, partly from talking to other people about their experiences, and partly via information I glean from the student evaluations I’ve read.

Speaking of evaluations, at some point I want to write about the noise that come from calculus evaluations, because that may as well be an entire subfield of statistics in itself. For example, I think there may be more variation depending on semester than depending on professor, due to the way kids take calculus in high school. In general it’s really hard to infer how good a job you did teaching based on calculus evaluations.

However, there is some signal. I remember reading about a study that said when some guy who was teaching two sections was introduced the first day in one of the sections by a distinguished-looking professor who went on about the instructor’s credentials, that class had much better end-of-semester evaluations, even though the content of the two sections was identical. Even more evidence that you should formally introduce yourself, if not bring in a friend for the job.

Never apologize

Last night I was talking to a friend of mine about my teaching experiences, and what’s it’s like to be a woman in math and to be taken seriously. We were going over the standard stuff, that women are too self-effacing compared to men and tend not to strut their stuff enough. But then I remembered this story from my early teaching experiences that kind of put a different spin on that.

I was in grad school, and over the summer I went to Berkeley to teach at a women in math program, which was still called the “Mill’s program” even though it was being held at Berkeley. It was a really fun experience, something like 30 days of lecture and problem session, and I led the problem sessions.

It was some time in the second week when, one day because of something or other, I hadn’t prepared completely and I apologized to the class for being slightly unprepared. I said something like, “sorry I’m not completely prepared today”. I remember thinking that, in spite of that, the class went very well and there was no “damage” from my being unprepared. Every other day I was completely, perhaps overly prepared, and that was the only day I ever mentioned something about my preparedness.

At the end of the summer we got back teaching evaluations, and I remember that a full half of the evaluations described me as unprepared.

I made a promise to myself never ever to apologize for anything again. And I never have, and I’ve never been accused like that since. Which isn’t to say I pretend to be a perfect teacher, but there are subtle ways of dealing with imperfections (my favorite: turn a self-criticism into a flattery. Instead of saying, oh how stupid I am for not thinking of that, say oh how smart you are for thinking of that. Generosity is not a negative in my experience!).

Going back to last night, though, it’ a two-way street. Women may be too self-effacing, but other people (including women!) are absolutely too dismissive. It’s a very important thing to keep in mind when you are teaching or presenting.

One other thing, in a one-on-one, professional setting, I believe you can apologize and not be executed for it (sometimes and depending on the person), but in a teacher-students setting, or when you’re presenting to clients in business, or even when you’re presenting to colleagues, you’re giving a performance and need to be flawlessly confident.

In an ideal world, we would use this information to learn to become better audiences, to not be dismissive and overly harsh of self-effacing people, and I do try to keep this in mind when I’m in the audience. But it’s going to take lots of effort for this to happen on a large scale, especially among strangers. It’s a cultural axiom in a certain sense.

My advice to young people, especially women: never apologize.

Are SAT scores going down?

I wrote here about standardizing tests like the SAT. Today I wanted to spend a bit more time on them since they’ve been in the news and it’s pretty confusing what to think.

First, it needs to be said that, as I have learned in this book I’m reading, it’s probably a bad idea to make statements about learning when you make “cohort-to-cohort comparisons” instead of following actual students along in time. In other words, if you compare how well the 3rd grade did in a test one year to the next, then for the most part the difference could be explained by the fact that they are different populations or demographics. Indeed the College Board, which administers the SAT, explains that the scores went down this year because more and more diverse kids are taking the test. So that’s encouraging, and it makes you think that the statement “SAT scores went down” is in this case pretty meaningless.

But is it meaningless for that reason?

Keep in mind that these are small differences we’re talking about, but with a pretty huge sample size overall. Even so, it would be nice to see some errorbars and see the methodology for computing errorbars.

What I’m really worried about though is the “equating” part of the process. That’s the process by which they decide how to compare tests from year to year, mostly by having questions in common that are ungraded. At least that’s what I’m guessing, it’s actually not clear from their website.

My first question is, are they keeping in mind the errors for the equating process? (I find it annoying how often people, when they calculate errors, only calculate based on the very last step they take in a very sketchy overall process with many steps.) For example, is their equating process so good that they can really tell us with statistical significance that American Indians as a group did 2 points worse on the writing test (see this article for numbers like this)? I am pretty sure that’s a best guess with significant error bars.

Additional note: found this quote in a survey paper on equating methodologies (top of page 519):

Almost all test-equating studies ignore the issue of the standard error of the equating

function.

Second, I’m really worried about the equating process and its errorbars for the following reason: the number of repeat testers varies widely depending on the demographic, and also from year to year. How then can we assess performance on the “linking questions” (the questions that are repeated on different tests) if some kids (in fact the kids more likely to be practicing for the test) are seeing them repeatedly? Is that controlled for, and how? Are they removing repeat testers?

This brings me to my main complaint about all of this. Why is the SAT equating methodology not open source? Isn’t the proprietary “intellectual property” in the test itself? Am I missing a link? I’d really like to take a look. Even better of course if the methodology is open source (as in there’s an available script which actually computes the scores starting with raw data) and the data is also available with anonymization of course.

How do you standardize tests?

I’m reading an interesting book by Douglas Harris about the value-added model movement, called Value-added Measures in Education, available here from Harvard Education Press. Harris goes into a very reasonable critique of how “snapshot” views of students, teachers, and school are a very poor assessment of teacher ability, since they are absolute measurements rather than changes in knowledge. Kind of like comparing the Dow to the S&P and concluding that you should definitely invest in Dow stocks since they are ten times better, it’s all about the return on a test score or an index, not the absolute number, when you are trying to gauge learning or profit.

His goal of the book is to explain how value-added models work, how they measure learning, how the take into account things like poverty level and other circumstances beyond the control of the school or the teachers, and other such factors. In his introduction he also promises not to be unreasonable about applying the results of these tests beyond where it makes sense. He certainly seems to be a smart guy; smart enough to know about errors and the problems with badly set up incentives – he uses the financial crisis as a model of how not to do it. I’m hopeful!

Here’s what I am interested in talking about today, which is how the “standardized” gets into standardized testing, because already at this point the mathematical modeling is pretty tricky (and involves lots of choices). There are many ways a test is ultimately standardized, assuming for simplicity that it’s a national test given at many grade levels yearly (pretend it’s an SAT that every grade takes):

- the test is normalized for being harder or easier than it was last year, for each grade’s test separately, and sometimes per question as well,

- the grading is normalized so that a student who learns exactly as much “as is expected” gets the same grade from year to year, and

- the grading is further normalized so that a student who gets 10 more points than expected in 3rd grade is doing as well as if she got 10 extra points in 4th grade.

One way of accomplishing all of the above would be to draw a histogram of raw results per year and per grade and normalize that distribution of raw scores by some standard mean and standard deviation, just as you would make a normal distribution standard, i.e. mean 0 and standard deviation 1. In fact, go ahead and demean it and divide by the standard deviation. That’s the first thing I’d do.

But if you actually do that, then you lose lots of the information you are actually trying to glean. Namely, how could you then conclude if students are doing better or worse than last year? I’m sure you’ve seen the recent news that SAT scores have fallen this year from last. I guess my question is, how can they tell? If we do something as simple as what I suggested, then the definition of doing as well “as is expected” is that you did “as well as the average person did”. But clearly this is not what the SAT people do, since they claim people aren’t doing as well as they used to. So how are they standardizing their test?

It isn’t really explained here or here, but there are clues. Namely, if you give 3rd and 4th graders some of the same questions on a given year, then you can infer how much better 4th graders do on those questions than 3rd graders do, and you can use that as a proxy for how to scale between grades (assuming that those questions represent the general questions well). Next, since you can’t repeat questions (at least questions that count towards the score) between years, because the stakes are too high and people would cheat, you can instead have ungraded sections that have repeated questions which give you a standard against which to compare between years. In fact the SAT does have ungraded sections, and so did the GREs as I recall, and my guess is this is why.

That brings up the question, do all standardized tests have ungraded sections? Is there some other clever way to get around this problem? Also in my mind, how well does standardization work, and what is a way to test it?

What is the mission statement of the mathematician?

In the past five years, I’ve been learning a lot about how mathematics is used in the “real world”. It’s fascinating, thought provoking, exciting, and truly scary. Moreover, it’s something I rarely thought about when I was in academics, and, I’d venture to say, something that most mathematicians don’t think about enough.

It’s weird to say that, because I don’t want to paint academic mathematicians as cold, uncaring or stupid. Indeed the average mathematician is quite nice, wants to make the world a better place (at least abstractly), and is quite educated and knowledgeable compared to the average person.