Archive

The class warfare of Halloween

What’s the best thing about Halloween, the dress-up or the candy? Or is it the fact that, for that one night, you can go up to people’s houses and ring their bell and talk to them when they answer the door, and if you’re a kid you can even get demand and receive a gift? (Update: I asked my 6-year-old this question and he answered immediately: “it’s eating the candy afterwards.”)

For me it’s always been about the way social rules get thrown out the window and there’s a celebration of generosity and neighborliness. Costumes are the excuse to tell each other how amazing they look, and candy is the excuse to symbolically exchange a token of friendship.

I pretty much had kids in part so I could start going trick-or-treating again, that’s how much I love it. And yes, I went trick-or-treating well into my teens, it was embarrassing for everyone except my best friends who went with me. Near the end there we’d use the phrase “tricks or beer!” just to make fun of ourselves at being too old to do it. But it was addictive and magical nonetheless because of the human interactions and the broken rules. Thrilling.

Even when I was a grown-up and before I had kids, I was super psyched to live in Somerville, Massachusetts where the trick-or-treating was an intense activity – people would drive to my street with piles of trick-or-treaters because we had the exact right density of buildings and everyone on the block would sit outside cheering on the little groups of candy-grabbers. Later on the older kids would come, and we’d leave whatever was left of our stash in big bowls on the porch. And even when we’d bought 12 bags of candy, it was never very expensive, and money wasn’t the point anyway. The point was the freedom.

At least that was my naive opinion until a friend of mine (subject line “this question made me want to nuke connecticut from orbit”) forwarded me this recent Slate.com’s Dear Prudence advice column entitled Kids from poorer neighborhoods keep coming to trick-or-treat in mine. Do I have to give them candy?

Read the column, unless you think you might barf. It’s exactly as bad as you think it is. The good news is that Prudence’s answer is spot on and includes the phrase:

Your whine makes me kind of wish that people from the actual poor side of town come this year not with scary costumes but with real pitchforks.

To tell you the truth, I’d never seen a whiff of class warfare in Halloween until this ridiculous question. But now, having thought about what Halloween represents, as an alternative – if very brief – economic system in which we all actually share (versus the so-called “sharing economy”), I can understand why someone who intensely examines and frets about their place in the hierarchy might find some way to distort it.

Instead of reveling in the inherent rule-breaking nature of Halloween, in other words, this person is threatened by it and wants to control it and make it conform to the class-based system they are familiar with. At least that’s my interpretation, because obviously it’s not really about how much Halloween candy costs.

Or maybe that person is just a witch (or a warlock).

Links (with annotation)

I’ve been heads down writing this week but I wanted to share a bunch of great stuff coming out.

- Here’s a great interview with machine learning expert Michael Jordan on various things including the big data bubble (hat tip Alan Fekete). I had a similar opinion over a year ago on that topic. Update: here’s Michael Jordan ranting about the title for that interview (hat tip Akshay Mishra). I never read titles.

- Have you taken a look at Janet Yellen’s speech on inequality from last week? She was at a conference in Boston about inequality when she gave it. It’s a pretty amazing speech – she acknowledges the increasing inequality, for example, and points at four systems we can focus on as reasons: childhood poverty and public education, college costs, inheritances, and business creation. One thing she didn’t mention: quantitative easing, or anything else the Fed has actual control over. Plus she hid behind the language of economics in terms of how much to care about any of this or what she or anyone else could do. On the other hand, maybe it’s the most we could expect from her. The Fed has, in my opinion, already been overreaching with QE and we can’t expect it to do the job of Congress.

- There’s a cool event at the Columbia Journalism School tomorrow night called #Ferguson: Reporting a Viral News Story (hat tip Smitha Corona) which features sociologist and writer Zeynep Tufekci among others (see for example this article she wrote), with Emily Bell moderating. I’m going to try to go.

- Just in case you didn’t see this, Why Work Is More And More Debased (hat tip Ernest Davis).

- Also: Poor kids who do everything right don’t do better than rich kids who do everything wrong (hat tip Natasha Blakely).

- Jesse Eisenger visits the defense lawyers of the big banks and writes about his experience (hat tip Aryt Alasti).

After writing this list, with all the hat tips, I am once again astounded at how many awesome people send me interesting things to read. Thank you so much!!

Bad Paper by Jake Halpern

Yesterday I finished Jake Halpern’s new book, Bad Paper: Chasing Debt From Wall Street To The Underground.

It’s an interesting series of close-up descriptions of the people who have been buying and selling revolving debt since the credit crisis, as well as the actual business of debt collecting. He talks about the very real problem, for debt collectors, of having no proof of debt, of having other people who have stolen on your debt trying to collect on it at the same time, and of course the fact that some debt collectors resort to illegal threats and misleading statements to get debtors – or possibly ex-debtors, it’s never entirely clear – to pay up or suffer the consequences. An arms race of quasi-legal and illegal cultural practices.

Halpern does a good job explaining the plight of the debt collectors, including the people hired for the call centers. It’s the poor pitted against the poorer here, a dirty fight where information asymmetry is absolutely essential to the profit margin of any given tier of the system.

Halpern outlines those tiers well, as well as the interesting lingo created by this subculture centered, at least until recently, in Buffalo, New York. People at the top are credit card companies themselves or hedge fund buyers from credit card companies; in other words, people who get “fresh debt” lists in the form of excel spreadsheets, where the people listed have recently stopped paying and might have some resources to pull. Then there are people who deal in older debt, which is harder to collect on. After that are people who have yet older debt which may or may not be stolen, so other collectors might simultaneously be picking over the carcasses. At the very bottom of the pile, from Halpern’s perspective, come the lawyers. They bring debtors to court and try to garnish wages.

Somewhat buried at very end of Halpern’s book is some quite useful information for the debtors. So for example, if you ever get dragged to court by a debt collection lawyer,

- definitely show up (or else they will just garnish your wages)

- ask for proof that they own the debt and how you spent it. They will likely not have such documentation and will dismiss your case.

Overall Bad Paper is a good book, and it explains a lot of interesting and useful information, but from my perspective, being firmly on the side of (most of) the debtors, everyone who gets a copy of the book should also get a copy of Strike Debt’s Debt Resistors’ Operation Manual, which has way more useful information, and even form letters, for the debtor.

As far as real solutions, we see the usual problems: underfunded and impotent regulators in the FTC, the CFPB, and the Attorney General’s office, as well as ridiculously small fines when actually caught that amount to fractions of the profit already made by illegal tactics. Everyone is feasting, even when they don’t find much meat on the bones.

Given how big a problem this is, and how many people are being pursued by debt collectors, you’d think they might set up a system of incentives so lawyers can make money by nailing illegal actions instead of just leveraging outdated information and trying to squeeze poor people out of their paychecks.

The bigger problem, once again, is that so many people are flat broke and largely go into debt for things like emergency expenses. And yes, of course there are people who buy a bunch of things they don’t need and then refuse to pay off their debts – Halpern profiles one such person – but the vast majority of the people we’re talking about are the struggling poor. It would be nice to see our country become a place where we don’t need so much damn debt in the first place, then the scavengers wouldn’t have so many rubbish piles to live off of.

Detroit’s water problem and the Koch brothers

Yesterday at the Alt Banking group we discussed the recent Koch brothers article from Rolling Stone Magazine, written by Tim Dickinson. You should read it now if you haven’t already.

There are tons of issues that came up, but one of them in particular was the control of information that the Koch brothers maintain over their activities. If you read the article, you realize that the brothers are die-hard libertarians but at some point realized that saying out loud that they are die-hard libertarians was working against them, specifically in terms of getting into trouble for polluting the environment with their chemical factories, so instead they started talking about how much they love the environment and work to protect it.

It’s not that they stopped polluting, it’s that their rhetoric changed. In fact there’s no reason to think they stopped polluting, since they still had plenty of regulators going after them for various violations. Since their apparent change of heart they’ve also decided to be publicly philanthropic, giving money to hospitals, and Lincoln Center, and even PBS (see how that worked out on Stephen Colbert).

The problem with all this window dressing is that people are actually starting to think the Koch brothers may be good guys after all, and what with the fancy lawyers that the Koch brothers hire to control information about them, the public view is very skewed.

For example, how many economists have they bought and inserted into universities nationwide? We will never really know. There’s no way we can keep a score sheet with “good deeds” on one side and “shitty deeds” on the other. We don’t have enough information for the second side.

The exception to this information control is when they get in trouble with regulators and it becomes a matter of public record. And thank goodness those court documents exist, and thank goodness investigative journalist Tim Dickinson did all the work he did to explain it to us.

A couple of conclusions. First, we complain a lot about the bank settlements for the misdeeds of the big banks. Nobody went to jail, and the system is just as likely to repeat this kind of thing again as it was in 2005. But another problem with this out-of-court settlement process, we now realize, is that we actually don’t know what happened except in big, vague terms. There will be no Tim Dickinson reporting on big banks.

Second, the connection to Detroit. Right now there are 15,000 residents of Detroit whose water has been shut down, basically so they can privatize the water system with the best deal from Wall Street. They owe less than $10 million, on average a measly $540. The United Nations has called this water shutoff a violation of the human rights of the people of Detroit.

If you feel bad about that, you can donate to someone’s water bill directly, which is kind of neat.

Or is it? Shouldn’t Obama be declaring Detroit a state of emergency? Wouldn’t we be doing that in another city that had 15,000 residents without water? Why is this an exception to that rule? Because the victims are poor? Don’t we recognize Detroit as a place where it’s unusually difficult to find work? Are we going to allow people to shut off heat as well, once winter comes?

Once you think about it, the idea of a “private solution” to the Detroit water emergency seems wrong. In fact, you can almost imagine David Koch coming to the rescue here, as part of his “positive optics” campaign, and bailing out the Detroit citizens and then, for good measure, buying up the water system altogether. A hero!

And if you’re in that mode, you can think about the asymptotic limit of that approach, whereby a few very rich people gradually take control of resources, and then there are intermittent famines of various types in different cities, and the rich people swoop in and heroically save the day whilst scooping up even more ownership of what used to be public infrastructure. And we might thank them every time, because it was a dire situation and they didn’t really need to do that with all their money.

It’s frustrating to live in a country that has so many resources but which can’t seem to get it together to meet the basic human needs of its citizens. We need a basic income, at least for the people in Detroit, at least right now.

Chameleon models

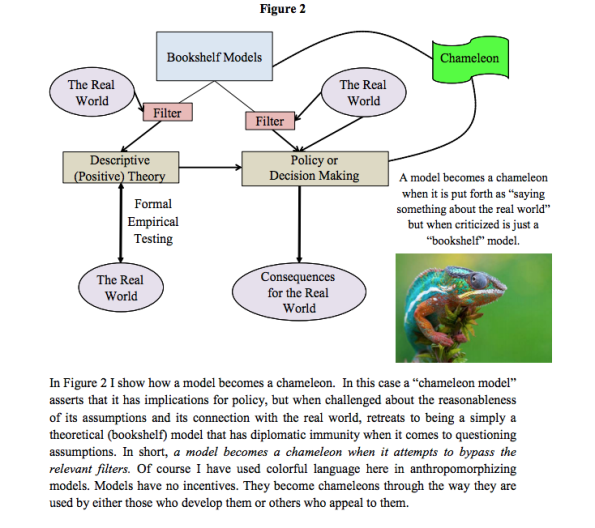

Here’s an interesting paper I’m reading this morning (hat tip Suresh Naidu) entitled Chameleons: The Misuse of Theoretical Models in Finance and Economics written by Paul Pfleiderer. The paper introduces the useful concept of chameleon models, defined in the following diagram:

Pfleiderer provides some examples of chameleon models, and also takes on the Milton Friedman argument that we shouldn’t judge a model by its assumptions but rather by its predictions (personally I think this is largely dependent on the way a model is used; the larger the stakes, the more the assumptions matter).

I like the term, and I think I might use it. I also like the point he makes that it’s really about usage. Most models are harmless until they are used as political weapons. Even the value-added teacher model could be used to identify school systems that need support, although in the current climate of distorted data due to teaching to the test and cheating, I think the signal is probably very slight.

Guest post: New Federal Banking Regulations Undermine Obama Infrastructure Stance

This is a guest post by Marc Joffe, a former Senior Director at Moody’s Analytics, who founded Public Sector Credit Solutions in 2011 to educate the public about the risk – or lack of risk – in government securities. Marc published an open source government bond rating tool in 2012 and launched a transparent credit scoring platform for California cities in 2013. Currently, Marc blogs for Bitvore, a company which sifts the internet to provide market intelligence to municipal bond investors.

Obama administration officials frequently talk about the need to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Yet new regulations published by the Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC run counter to this policy by limiting the market for municipal bonds.

On Wednesday, bank regulators published a new rule requiring large banks to hold a minimum level of high quality liquid assets (HQLAs). This requirement is intended to protect banks during a financial crisis, and thus reduce the risk of a bank failure or government bailout. Just about everyone would agree that that’s a good thing.

The problem is that regulators allow banks to use foreign government securities, corporate bonds and even stocks as HQLAs, but not US municipal bonds. Unless this changes, banks will have to unload their municipal holdings and won’t be able to purchase new state and local government bonds when they’re issued. The new regulation will thereby reduce the demand for bonds needed to finance roads, bridges, airports, schools and other infrastructure projects. Less demand for these bonds will mean higher interest rates.

Municipal bond issuance is already depressed. According to data from SIFMA, total municipal bonds outstanding are lower now than in 2009 – and this is in nominal dollar terms. Scary headlines about Detroit and Puerto Rico, rating agency downgrades and negative pronouncements from market analysts have scared off many investors. Now with banks exiting the market, the premium that local governments have to pay relative to Treasury bonds will likely increase.

If the new rule had limited HQLA’s to just Treasuries, I could have understood it. But since the regulators are letting banks hold assets that are as risky as or even riskier than municipal bonds, I am missing the logic. Consider the following:

- No state has defaulted on a general obligation bond since 1933. Defaults on bonds issued by cities are also extremely rare – affecting about one in one thousand bonds per year. Other classes of municipal bonds have higher default rates, but not radically different from those of corporate bonds.

- Bonds issued by foreign governments can and do default. For example, private investors took a 70% haircut when Greek debt was restructured in 2012.

- Regulators explained their decision to exclude municipal bonds because of thin trading volumes, but this is also the case with corporate bonds. On Tuesday, FINRA reported a total of only 6446 daily corporate bond trades across a universe of perhaps 300,000 issues. So, in other words, the average corporate bond trades less than once per day. Not very liquid.

- Stocks are more liquid, but can lose value very rapidly during a crisis as we saw in 1929, 1987 and again in 2008-2009. Trading in individual stocks can also be halted.

Perhaps the most ironic result of the regulation involves municipal bond insurance. Under the new rules, a bank can purchase bonds or stock issued by Assured Guaranty or MBIA – two major municipal bond insurers – but they can’t buy state and local government bonds insured by those companies. Since these insurance companies would have to pay interest and principal on defaulted municipal securities before they pay interest and dividends to their own investors, their securities are clearly more risky than the insured municipal bonds.

Regulators have expressed a willingness to tweak the new HQLA regulations now that they are in place. I hope this is one area they will reconsider. Mandating that banks hold safe securities is a good thing; now we need a more data-driven definition of just what safe means. By including municipal securities in HQLA, bank regulators can also get on the same page as the rest of the Obama administration.

Reverse-engineering the college admissions process

I just finished reading a fascinating article from Bloomberg BusinessWeek about a man who claims to have reverse-engineered the admission processes at Ivy League colleges (hat tip Jan Zilinsky).

His name is Steven Ma, and as befits an ex-hedge funder, he has built an algorithm of sorts to work well with both the admission algorithms at the “top 50 colleges,” and the US News & World Report model which defines which colleges are in the “to 50.” It’s a huge modeling war that you can pay to engage in.

Ma is a salesman too: he guarantees that a given high-school kid will get into a top school, your money back. In other words he has no problem working with probabilities and taking risks that he think are likely to pay off and that make the parents willing to put down huge sums. Here’s an example of a complicated contract he developed with one family:

After signing an agreement in May 2012, the family wired Ma $700,000 over the next five months—before the boy had even applied to college. The contract set out incentives that would pay Ma as much as $1.1 million if the son got into the No. 1 school in U.S. News’ 2012 rankings. (Harvard and Princeton were tied at the time.) Ma would get nothing, however, if the boy achieved a 3.0 GPA and a 1600 SAT score and still wasn’t accepted at a top-100 college. For admission to a school ranked 81 to 100, Ma would get to keep $300,000; schools ranked 51 to 80 would let Ma hang on to $400,000; and for a top-50 admission, Ma’s payoff started at $600,000, climbing $10,000 for every rung up the ladder to No. 1.

He’s also interested in reverse-engineering the “winning essay” in conjunction with after-school activities:

With more capital—ThinkTank’s current valuation to potential investors is $60 million—Ma hopes to buy hundreds of completed college applications from the students who submitted them, along with the schools’ responses, and beef up his algorithm for the top 50 U.S. colleges. With enough data, Ma plans to build an “optimizer” that will help students, perhaps via an online subscription, choose which classes and activities they should take. It might tell an aspiring Stanford applicant with several AP classes in his junior year that it’s time to focus on becoming president of the chess or technology club, for example.

This whole college coaching industry reminds me a lot of financial regulation. We complicate the rules to the point where only very well-off insiders know exactly how to bypass the rules. To the extent that getting into one of these “top schools” actually does give young people access to power, influence, and success, it’s alarming how predictable the whole process has become.

Here’s a thought: maybe we should have disclosure laws about college coaching and prep? Or would those laws be gamed too?

Distributional Economic Health

I am pushing an unusual way of considering economic health. I call it “distributional thinking.” It requires that you not aggregate everything into one statistic, but rather take a few samples from different parts of the distribution and consider things from those different perspectives.

So instead of saying “things are great because the economy has expanded at a rate of 4%” I’d like us to think about more individual definitions of “great.”

For example, it’s a good time to be rich right now. Really good. The stock market keeps hitting all-time highs, the jobs market is great in tech, and it’s still absolutely possible to hide wealth in off-shore tax havens.

It’s not so good to be middle class. Wages are stagnant and have been forever, and jobs are drying up due to automation and a lack of even maintenance-level infrastructure work. Colleges are super expensive, and the best the government can do is fiddle around the edges with interest rates.

It’s a really bad time to be poor in this country. Jobs are hard to find and conditions are horrible. There are more and more arrests for petty crimes as the violent crime rate goes down. Those petty crime arrests lead to big fees and sometimes jail time if you can’t pay the fee. Look at Ferguson as an example of what this kind of frustration this can lead to.

Once you are caught in the court system, private probation companies act as abusive debt collectors, and nobody controls their fees, which can be outrageous. To be clear, we let this happen in the name of saving money: private for-profit companies like this guarantee that they won’t cost anything to the local government because they make the people on probation pay for services.

And even though that’s an outrageous and predatory system, it’s not likely to go away. Once they are officially branded as criminals, the poor often lose their voting rights, which means they have little political recourse to protect themselves. On the flip side, they are largely silent about their struggles for the same reason.

Once you think about our economic health this way, you realize how comparatively meaningless the GDP is. It is no longer a good proxy to true economic health, where all classes would be more or less better off as it went up.

And until we get on the same page, where we all go up and down together, it is a mathematical fact that no one statistic could possibly capture the progress we are or are not making. Instead, we need to think distributionally.

The economics of a McDonalds franchise

I’ve been fascinated to learn all sorts of things about how McDonalds operates their business in the past few days, as news broke about a recent NLRB decision to allow certain people who work in McDonalds to file complaints about their workplace and name McDonalds as a joint employer.

That sounds incredibly dull, right? The idea of letting McDonalds workers name McDonalds as an employer? Let me tell you a bit more. And this is all common knowledge, but I thought I’d gather it here for those of you who haven’t been following the story.

Most of the McDonalds joints you go to are franchises – 90% in this country. That means the business is owned by a franchisee, a person who pays good money (details here) for the right to run a McDonalds and is constrained by a huge long list of rules about how they have to do it.

The franchise owner attends Hamburger University and gets trained in all sorts of things, like exactly how things should look in the store, how customers should be funneled through space (maps included), how long each thing should take, and how to treat employees. There’s a QSC Playbook they are given (Quality, Service, and Cleanliness) as well as minute descriptions of how to organize their teams and even the vocabulary words they should use to encourage workers (see page 24 of the Shift Management Guide I found online here).

McDonalds also installs a real-time surveillance system into each McDonalds, which can calculate the rate of revenue brought in at a given moment, as well as the rate of pay going out, and when the ratio of those two numbers reaches a certain lower bound threshold, they encourage franchise owners to ask people to leave or delay people from clocking in. Encourage, mind you, not require. They are not the employers or anything remotely like that, clearly.

Take a step back here. What is the business model of a franchise? And when did McDonalds stop being a burger joint?

The idea is this. When you own a restaurant you have to deal with all these people who work for you and you have to deal with their complaints, and they might not like the way you treat them and they might organize against you or sue you. In order to contain your risks, you franchise. That effectively removes all of those people except one, the franchise owner, with whom you have an air-tight contract, written by a huge team of lawyers, which basically says that you get to cancel the franchise agreement for any minor infraction (where they’d lose a bunch of investment money), but most importantly it means the people actually working in a given franchise work for that one person, not for you, so their pesky legal issues are kept away from you. It’s a way to box in the legal risk of the parent company.

Restaurants aren’t the only business to learn that it’s easier to sell and manage a brand than it is to sell and manage an actual product. Hotels have been doing this for a long time, and avoid complaints and legal issues stemming from the huge population of service workers in hotels, mostly minority women.

For a copy of the original complaint that gave the details of McDonald’s control over workers, read this. For a better feel for being a McDonalds worker, please read this recent Reuters blog post written by a McDonalds worker. And for a better feel for being a McDonald’s franchise owner, read this recent Washington Post letter from a long-time McDonalds franchise owner who thinks workers are being unfairly treated.

Does that sounds confusing, that a franchise owner would side with the employees? It shouldn’t.

By nature of the franchise contract, the money actually available to a franchise owner is whatever’s left over after they pay McDonalds for advertising, and buy all the equipment and food that McDonalds tells them to from the sources that they tell them to, and after they pay for insurance on everything and for rent on the property (which McDonalds typically owns). In other words the only variable they have to tweak is the employer pay, but if they pay a living wage then they lose money on their business. In fact when franchise owners complain about the profit stream, McDonalds tells them to pay their workers less. McDonalds essentially controls everything except one variable, but since it’s a closed system of equations, that means the franchise owners have to decide between paying their workers reasonably and going in the red.

That’s not to say, of course, that McDonalds as an enterprise is at risk of losing money. In fact the parent corporation is making good money ($1.4 billion per quarter if you include international revenue), by squeezing the franchises. If the franchise owners had more leverage to negotiate better contracts, they could siphon off more revenue and then – possibly – share it with workers.

So back to the ruling. If upheld, and there’s a good chance it won’t be but I’m feeling hopeful today, this decision will allow people to point at McDonalds the corporation when they are treated badly, and will potentially allow a workers’ union to form. Alternatively it might energize the franchise owners to negotiate more flexible contracts, which could allow them to pay their workers better directly.

How to think like a microeconomist

Yesterday we were pleased to have Suresh Naidu guest lecture in The Platform. He came in and explained, very efficiently because he was leaving at 11am for a flight at noon at LGA (which he made!!) how to think like an economist. Or at least an applied microeconomist. Here are his notes:

Applied microeconomics is basically organized a few simple metaphors.

- People respond to incentives.

- A lot of data can be understood through the lens of supply and demand.

- Causality is more important than prediction.

There was actually more on the schedule, but Suresh got into really amazing examples to explain the above points and we ran out of time. At some point, when he was describing itinerant laborers in the United Arab Emirates, and looking at pay records and even visiting a itinerant labor camp, I was thinking that Suresh is possibly an undercover hardcore data journalist as well as an amazing economist.

As far as the “big data” revolution goes, we got the impression from Suresh that microeconomists have been largely unmoved by its fervor. For one, they’ve been doing huge analyses with large data sets for quite a while. But the real reason they’re unmoved, as I infer from his talk yesterday, is that big data almost always focuses on descriptions of human behavior, and sometimes predictions, and almost never causality, which is what economists care about.

A side question: why is it that economists only care about causality? Well they do, and let’s take that as a given.

So, now that we know how to think like an economist, let’s read this “Room For Debate” about overseas child labor with our new perspective. Basically the writers, or at least three out of four of them, are economists. So that means they care about “why”. Why is there so much child labor overseas? How can the US help?

The first guy says that strong unions and clear signals from American companies works, so the US should do its best to encourage the influence of labor unions.

The lady economist says that bans on child labor are generally counterproductive, so we should give people cash money so they won’t have to send their kids to work in the first place.

The last guy says that we didn’t even stop having child labor in our country until wage workers were worried about competition from children. So he wants the U.S. to essentially ignore child labor in other countries, which he claims will set the stage for other countries to have that same worry and come to the same conclusion by themselves. Time will help, as well as good money from the US companies.

So the economists don’t agree, but they all share one goal: to figure out how to tweak a tweakable variable to improve a system. And hopefully each hypothesis can be proven with randomized experiments and with data, or at least evidence can be gathered for or against.

One more thing, which I was relieved to hear Suresh say. There’s a spectrum of how much people “believe” in economics, and for that matter believe in data that seems to support a theory or experiment, and that spectrum is something that most economists run across on a daily basis. Even so, it’s not clear there’s a better way to learn things about the world than doing your best to run randomized experiments, or find close-to-randomized experiments and see how what they tell you.

The future of work

People who celebrate the monthly jobs report getting better nowadays often forget to mention a few facts:

- the new jobs are often temporary or part-time, with low wages

- the old lost jobs, which we lose each month, were often full-time with higher wages

I could go on, and I have, and mention the usual complaints about the definition of the unemployment rate. But instead I’ll take a turn into a thought experiment I’ve been having lately.

Namely, what is the future of work?

It’s important to realize that in some sense we’ve been here before. When all the farming equipment got super efficient and we lost agricultural jobs by the thousands, people swarmed to the cities and we started building things with manufacturing. So if before we had “the age of the farm,” we then entered into “the age of stuff.” And I don’t know about you but I have LOTS of stuff.

Now that all the robots have been trained and are being trained to build our stuff for us, what’s next? What age are we entering?

I kind of want to complain at this point that economists are kind of useless when it comes to questions like this. I mean, aren’t they in charge of understanding the economy? Shouldn’t they have the answer here? I don’t think they have explained it if they do.

Instead, I’m pretty much left considering various science fiction plots I’ve heard about and read about over the years. And my conclusion is that we’re entering “the age of service.”

The age of service is a kind of pyramid scheme where rich people employ individuals to service them in various ways, and then those people are paid well so they can hire slightly less rich people to service them, and so on. But of course for this particular pyramid to work out, the rich have to be SUPER rich and they have to pay their servants very well indeed for the trickle down to work out. Either that or there has to be a wealth transfer some other way.

So, as with all theories of the future, we can talk about how this is already happening.

I noticed this recent Bloomberg View article about how rich people don’t have normal doctors like you and me. They just pay out of pocket for super expensive service outside the realm of insurance. This is not new but it’s expanding.

Here’s another example of the future of jobs, which I should applaud because at least someone has a job but instead just kind of annoys me. Namely, the increasing frequency where I try to make a coffee date with someone (outside of professional meetings) and I have to arrange it with their personal assistant. I feel like, when it comes to social meetings, if you have time to be social, you have time to arrange your social calendar. But again, it’s the future of work here and I guess it’s all good.

More generally: there will be lots of jobs helping out old people and sick people. I get that, especially as the demographics tilt towards old people. But the mathematician in me can’t help but wonder, who will take care of the old people who used to be taking care of the old people? I mean, they by definition don’t have lots of extra cash floating around because they were at the bottom of the pyramid as younger workers.

Or do we have a system where people actually change jobs and levels as they age? That’s another model, where oldish people take care of truly old people and then at some point they get taken care of.

Of course, much like the Star Trek world, none of this has strong connection to the economy as it is set up now, so it’s hard to imagine a smooth transition to a reasonable system, and I’m not even claiming my ideas are reasonable.

By the way, by my definition most people who write computer programs – especially if they’re writing video games or some such – are in a service industry as well. Pretty much anyone who isn’t farming or building stuff in manufacturing is working in service. Writers, poets, singers, and teachers included. Hell, the future could be pretty awesome if we arrange things well.

Anyhoo, a whimsical post for Thursday, and if you have other ideas for the future of work and how that will work out economically, please comment.

You are not Google’s customer

I’m going to write one of those posts where many of you will already understand my point. In fact it might be old hat for a majority of my readers, yet it’s still important enough for me to mention just in case there are a few people out there who don’t know how the modern business model is set up.

Namely, like this. As a gmail and Google Search user, you are not a customer of Google. You are the product. The customers of Google are the ones who advertise to you. Your interaction with Google is, from the perspective of the business operation, that you give them information which they harvest so they can advertise to you in a more targeted way, thus increasing the likelihood of you clicking. The fact that you get a service from these interactions is great, because it means you’ll come back to give Google and its customers more information about you soon.

This misunderstanding, once you see it as such, can be clarifying. For example, when people talk about anti-trust and Google, they should talk about whether the customers of Google have any other serious choice. And since the customers of Google are advertisers, not gmailers or searchers, the alternatives aren’t hotmail or Bing. Rather they are other advertising outlets. And a very good case can be made that Google does violate anti-trust laws in that sense, just ask Nathan Newman.

It also explains why something like the recent European “right to be forgotten” law seems so strange and unreasonable to the powers that be at Google. It’d be like a meat farm where the cows go on strike and demand better food. Cows are the product, and they aren’t supposed to complain. They’re not even supposed to be heard. At worst we treat them better when our customers demand it, not when the cows do.

I was reminded about this ubiquitous business model yesterday, and newly enraged by its consequences, when reading this article entitled Held Captive by Flawed Credit Reports (hat tip Linda Brown) about the credit score agency Experian and how they utterly disregard the laws trying to protect consumers from mistakes in their credit reports. The problem here is that, to the giant company Experian, its customers are giant companies like Verizon which send credit score requests millions of times a day and pay for each score. Mere people, whose mortgage application is being denied because of mistakes, are the product, not the customer, and they are almost by definition unimportant.

And it seems that the law which is supposed to protect these people, namely the Fair Credit Reporting Act, first passed in 1970, doesn’t have enough teeth behind it to make the big credit scoring agencies sit up and pay attention. It’s all about the scale of the fines compare to the scale of the business. This is well explained in the article (emphasis mine):

Last year, the Federal Trade Commission found that 5 percent of consumers — or an estimated 10 million people — had an error on one of their credit reports that could have resulted in higher borrowing costs.

The F.T.C., which oversees the industry along with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has been busy bringing cases in this arena. Since 2000, it has filed 18 enforcement actions against reporting bureaus; 13 were district court actions that generated $25.7 million in penalties.

Consumers have also won in the courts, on occasion. Last year, an Oregon consumer was awarded $18.4 million in punitive damages by a jury after she sued Equifax for inserting errors into her credit report. But the fines, settlements and judgments paid by the larger companies are not even close to a rounding error. Experian generated $4.8 billion in revenue for the year ended March 2014, and its after-tax profit of $747 million in the period was more than twice its 2013 figure.

Million versus billion. It seems like the cows don’t have much leverage.

Marc Andreessen and Al3x Payne

My friend Chris Wiggins just sent me this recent letter by Alex “Al3x” Payne in response to this recent post by Marc Andreessen. Andreessen’s original post is entitled This is Probably a Good Time to Say That I Don’t Believe Robots Will Eat All the Jobs… and the rebuttal is entitled simply Dear Marc Andreessen.

To get a flavor of the exchange, we’ll start with this from Andreessen:

What never gets discussed in all of this robot fear-mongering is that the current technology revolution has put the means of production within everyone’s grasp. It comes in the form of the smartphone (and tablet and PC) with a mobile broadband connection to the Internet. Practically everyone on the planet will be equipped with that minimum spec by 2020.

versus this from Payne:

If we’re gonna throw around Marxist terminology, though, can we at least keep Karl’s ideas intact? Workers prosper when they own the means of production. The factory owner gets rich. The line worker, not so much.

Owning a smartphone is not the equivalent of owning a factory. I paid for my iPhone in full, but Apple owns the software that runs on it, the patents on the hardware inside it, and the exclusive right to the marketplace of applications for it.

…

You spent a lot of paragraphs on back-of-the-napkin economics describing the coming Awesome Robot Future, addressing the hypotheticals. What you left out was the essential question: who owns the robots?

Please read both the original post and the rebuttal in their entireties. At it’s heart, their conversation strikes me as a somewhat more contentious version of the argument I’ve had with myself about the utopia envisioned in Star Trek.

Namely, at some point we’ll have all these robots doing stuff for us, but how are we going to spread that wealth around? Who owns the robots and when are they going to learn to share? In this vision of the distant future, that critical “singularity of moral enlightenment” (SME) is never explained. I wish I could ask Captain Picard how it all went down.

It’s one thing to lack an explanation for the SME, and to consider it an aspirational quasi-religious utopian goal, but it’s another thing entirely to fail to acknowledge it.

That someone as powerful and famous as Mark Andreessen, who is personally involved in the development and nurturing of so many technology platforms, has trouble seeing the logical inconsistency of his own rhetoric can only be explained by the fact that, as the controller of such platforms, it is he who reaps their benefits. It’s yet another case of someone thinking “this system works for me therefore it is super awesome for everyone and everything, amen.”

I’m hoping Al3x’s fine response will get Marc to consider how SME is gonna happen, and when.