Archive

Mortar Hawk: hadoop made easy

Yesterday a couple of guys from Mortar came to explain their hadoop platform. You can see a short demo here. I wanted to explain it at a really high level because it’s cool and a big deal for someone like me. I’m not a computer scientist by training, and Mortar allows me to work with huge amounts of data relatively easily. In other words, I’m not sure what ultimately will be the interface for analytics people like me to get access to massive data, but it will be something like this, if not this.

To back up one second, for people who are nodding off, here’s the thing. If you have terabytes of data to crunch, you can’t put it on your computer to take a look at it, and then crunch, because your computer is too small. So you need to pre-crunch. That’s pretty much the problem we need to solve, and people have solved it either one of two ways.

The first is to put your data onto a big relational database, on the cloud or something, and use SQL or some such language to do the crunching (and aggregating and what have you) until it’s small enough to deal with, and then download it and finish it off on your computer. The second solution, called MapReduce (the idea started at Google), or hadoop (the open-source implementation started at Yahoo) allows you to work on the raw data directly where it lies (e.g. on the Amazon cloud (where it’s actually Elastic MapReduce, which I believe is a fork of hadoop)), in iterative steps called mappings and reduction steps.

Actually there’s an argument to be made, apparently, because I heard it at the Strata conference, that data scientists should never use hadoop at all, that we should always just use relational databases. However, that doesn’t seem economical, the way it’s set up at my work anyway. Please comment if you have an opinion about this because it’s interesting to me how split the data science community seems to be about this issue.

On the other hand, if you can make using hadoop as easy as using SQL, then who cares? That’s kind of what’s happened with Mortar. Let me explain.

Mortar has a web-based interface with two windows. On top we have the pig window and on the bottom a python editor. The pig window is in charge and you can call python functions in the pig script if you have defined them below. Pig is something like SQL but is procedural, so you tell it when to join and when to aggregate and what functions to use in what order. Then pig figures out how to turn your code into map-reduce steps, including how many iterations. They say pig is good at this but my guess is that if you really don’t know anything about how map-reduce works then it’s possible to write pig code that’s super inefficient.

One cool feature, which I think comes from pig itself but in any case is nicely viewable through the Mortar interface, is that you can ask it to “illustrate” the resulting map-reduce code and it takes a small sample of your data and shows example data (of “every type” in a certain sense) at every step of the process. This is super useful as a bug-watching feature to see that it’s looking good with small data sets.

The interface is well designed and easy to use. Overall it reduces a pretty scary and giant data job to something that would probably take me about a week to feel comfortable. And new hires who know python can get up to speed really quickly.

There are some issues right now, but the Mortar guys seem eager to improve the product quickly. To name a few:

- it’s not yet connected to git (although you can save pig and python code you’ve already run),

- you can’t import most python modules except super basic ones like math (including ones you’ve written; right now you have to copy and paste into their editor),

- they won’t be able to ever let you import numpy because they are actually using jython and numpy is c-based,

- it doesn’t automatically shut down the cluster after your job is finished, and

- it doesn’t yet allow people to share a cluster

These last two mean that you have to be pretty on top of your stuff, which is too bad if you want to leave for the night and start a job and then bike home and feed your kids and put them to bed. Which is kind of my style.

Please tell me if any of you know other approaches that allow python-savvy (but not java savvy) analytics nerds access to hadoop in an easy way!

Why and how to hire a data scientist for your business

Here are the annotated slides from my Strata talk. The audience consisted of business people interested in big data. Many of them were coming from startups that are newly formed or are currently being formed, and are wondering who to hire.

When do you need a data scientist?

When you have too much data for Excel to handle: data scientists know how to deal with large data sets.

When your data visualization skills are being stretched: as we will see, data scientists are skilled (or should be) at data visualization and should be able to figure out a way to visualize most quantitative things that you can describe with words.

When you aren’t sure if something is noise or information: this is a big one, and we will come back to it.

When you don’t know what a confidence interval is: this is related to the above; it refers to the fact that almost every number you see coming out of your business is actually an estimate of something, and the question you constantly face is, how trustworthy is that estimate?

Let’s take a step back: Should you need a data scientist?

Are you asking the right questions? Is there a business that you’re not in that you could be in if you were thinking more quantitatively? Big data is making things possible that weren’t just a few years ago.

Are you getting the most out of your data? In other words, are you sitting on a bunch of delicious data and not even trying to mine it for your business?

Are you anticipating shocks to your business? As we will see, data scientists can help you do this in ways you may be surprised at.

Are you running your business sufficiently quantitatively? Are you not collecting the data (or not collecting it in a centralized way) that would lead to opportunities for data mining?

So, you’ve decided to hire a Data Scientist (nice move!)

What do you need to get started?

Data storage. You gotta keep all your data in one place and in some unified format.

Data access — usually through a database (payoffs for different types). Specifically, you can pay for someone else to run a convenient SQL database that people know how to use walking in the door without much training, or you could set something up that’s open source and “free” but then it will probably take more time to set up and make take the data scientists longer to figure out how to use. The investment here is to create tools to make it convenient to use.

Larger-scale or less uniform data may require Hadoop access (and someone with real tech expertise to set it up). The larger your data is the more complicated and developed your skills need to be to access it. But it’s getting easier (and other people here at the conference can tell you all you need to know about services like this).

Who and how should you hire? It’s not obvious how to hire a data scientist, especially if your business so far consists of less mathematical people.

A math major? Perhaps a Masters in statistics? Or a Ph.D. in machine learning? If you’re looking for someone to implement a specific thing, then you just need proof that they’re smart and know some relevant stuff. But typically you’re asking more than that: you’re asking for them to design models to answer hard questions and even to figure out what the right questions are. For that reason you need to see that the candidate has the ability to think independently and creatively. A Ph.D. is evidence of this but not the only evidence- some people could get into grad school or even go for a while but decide they are not academically-minded, and that’s okay (but you should be looking for someone who could have gotten a Ph.D. if they’d wanted to). As long as they went somewhere and challenged themselves and did new stuff and created something, that’s what you want to see. I’ll talk about specific skills you’d like in a later section, but keep in mind that these are people who are freaking smart and can learn new skills, so you shouldn’t obsess over something small like whether they already know SQL.

What should the job description include? Things like, super quantitative, can work independently, know machine learning or time series analysis, data visualization, statistics, knows how to program, loves data.

Who even interviews someone like this? Consider getting a data scientist as a consultant just to interview a candidate to see if they are as smart as they claim to be. But at the same time you want to make sure they are good communicators, so ask them to explain their stuff to you (and ask them to explain stuff that has been on your mind lately too) and make sure they can.

Also: don’t confuse a data scientist with a software engineer! Just as software engineers focus on their craft and aren’t expected to be experts at the craft of modeling, data scientists know how to program in the sense that they typically know how to use a scripting language like python to manipulate the data into a form where they can do analytics on it. They sometimes even know a bit of java or C, but they aren’t software engineers, and asking them to be is missing the point of their value to your business.

What do you want from them?

Here are some basic skills you should be looking for when you’re hiring a data scientist. They are general enough that they should have some form of all of them (but again don’t be too choosy about exactly how they can address the below needs, because if they’re super smart they can learn more):

- Data grappling skills: they should know how to move data around and manipulate data with some programming language or languages.

- Data viz experience: they should know how to draw informative pictures of data. That should in fact be the very first thing they do when they encounter new data

- Knowledge of stats, errorbars, confidence intervals: ask them to explain this stuff to you. They should be able to.

- Experience with forecasting and prediction, both general and specific (ex): lots of variety here, and if you have more than one data scientist position open, I’d try to get people from different backgrounds (finance and machine learning for example) because you’ll get great cross-pollination that way

- Great communication skills: data scientists will be a big part of your business and will contribute to communications with big clients.

What does a Data Scientist want from you? This is an important question because data scientists are in high demand and are highly educated and can get poached easily.

Interesting, challenging work. We’re talking about nerds here, and they love puzzles, and they get bored easily. Make sure they have opportunities to work on good stuff or they’ll get other jobs. Make sure they are encouraged to think of their own projects when it’s possible.

Lots of great data (data is sexy!): data scientists love data, they play with it and become intimate with it. Make sure you have lots of data, or at least really high-quality data, or soon will, before asking a data scientist to work for you. Data science is an experimental science and cannot be done without data!

To be needed, and to have central importance to the business. Hopefully it’s obvious that you will want your data scientists to play a central role in your business.

To be part of a team that is building something: this should be true of anyone working in business, especially startups. If your candidate wants to write academic papers and sit around while they get published, then hire someone else.

A good and ethically sound work atmosphere.

Cash money. Most data scientists aren’t totally focused on money though or they would go into finance.

Further business reasons for hiring a Data Scientist

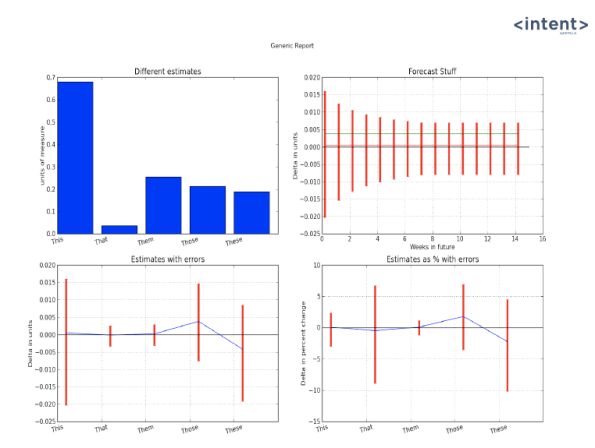

Reporting help: automatically generated daily reports can be a pain to set up and can require lots of tech work and may even require a dedicated person to generate charts. Data scientists can pull together certain kinds of reports in a matter of days or weeks and generate them every day with cronjobs. Here’s a sample picture of something I did at my job:

Having a data scientist enables you to see into data without taxing your tech team (beyond setup) via visualizations and reports like the above.

Having a data scientist enables you to see into data without taxing your tech team (beyond setup) via visualizations and reports like the above.

A/B testing: data scientists help you set up A/B testing rigorously.

Beyond A/B testing: adaptability and customization. What you really want to do is get beyond A/B testing. Instead of having the paradigm where customers come to the ad and respond in a certain way, we want to have the (right) ad come to the customer.

Knowing whether numbers are random (seasonality) or require action. If revenue goes down in a certain week, is that because of noise? Or is it because it always goes down the week after Labor Day? Data scientists can answer questions like this.

What-if analysis: you can ask data scientists to estimate what would happen to revenue (or some other stat) if a client drops you, or if you gain a new client, or if someone doubles their bid at an auction (more on this later).

Help with business planning: Will there be enough data to answer a given question? Will there be enough data to optimize on the answer? These are some of the most difficult and most important questions, and the fact that a data scientist can help you answer them means they will be central to the business.

Education for senior management: senior people who talk to and recruit new clients will need to be able to explain how to think about the data, the signals, the stats, and the errorbars in a rigorous and credible way. Data scientists can and should take on the role of an educator for situations like this.

Mathematically sound communication to clients: you may have situations where you need the data scientists to talk directly to clients or to their data scientists. This is yet another reason to make sure you hire someone with excellent communication skills, because they will be representing your business to really smart people who can see through bullshit.

Case Study: Stress Tests

We can learn from finance: the idea of a stress test is stolen directly from finance, where we look at how replays of things like the credit crisis would affect portfolios. I wanted to do something like that but for general environmental effects that a business like mine, which hosts an advertising platform, encounters.

You know how big changes will affect your business directionally and specifically. But do you know how combinations will play out? Stress tests allow you to combine changes and estimate their overall effect quantitatively. For example, say we want to know how lowering or raising their bids (by some scalar amount) will effect advertisers impression share (the number of times their ads get displayed to users). Then we can run that as a scenario (for each advertiser separately) using the last two weeks (say) of auction data with everything else kept the same, and compare it to what actually happened in the last two weeks. This gives an estimate of how such a change would affect impression change in the future. Here’s a heat map of possible results of such a “stress test”:

This shows a client-facing person that Advertiser 13 would benefit a lot from raising their bid 50% but that Advertiser 12 would suffer from lowering their bid.

This shows a client-facing person that Advertiser 13 would benefit a lot from raising their bid 50% but that Advertiser 12 would suffer from lowering their bid.

We could also:

- run scenarios which combine things like the above

- run scenarios which ask different questions: how would advertisers be affected if a new advertiser entered the auction? If we change the minimum bid? If one of the servers fails? If we grow into new markets?

- run scenarios from the perspective of the business: how would revenue change if the bids change?

In the end stress tests can benefit any client-facing person or anyone who wants to anticipate revenue, so across many of the verticals of the business.

Are SAT scores going down?

I wrote here about standardizing tests like the SAT. Today I wanted to spend a bit more time on them since they’ve been in the news and it’s pretty confusing what to think.

First, it needs to be said that, as I have learned in this book I’m reading, it’s probably a bad idea to make statements about learning when you make “cohort-to-cohort comparisons” instead of following actual students along in time. In other words, if you compare how well the 3rd grade did in a test one year to the next, then for the most part the difference could be explained by the fact that they are different populations or demographics. Indeed the College Board, which administers the SAT, explains that the scores went down this year because more and more diverse kids are taking the test. So that’s encouraging, and it makes you think that the statement “SAT scores went down” is in this case pretty meaningless.

But is it meaningless for that reason?

Keep in mind that these are small differences we’re talking about, but with a pretty huge sample size overall. Even so, it would be nice to see some errorbars and see the methodology for computing errorbars.

What I’m really worried about though is the “equating” part of the process. That’s the process by which they decide how to compare tests from year to year, mostly by having questions in common that are ungraded. At least that’s what I’m guessing, it’s actually not clear from their website.

My first question is, are they keeping in mind the errors for the equating process? (I find it annoying how often people, when they calculate errors, only calculate based on the very last step they take in a very sketchy overall process with many steps.) For example, is their equating process so good that they can really tell us with statistical significance that American Indians as a group did 2 points worse on the writing test (see this article for numbers like this)? I am pretty sure that’s a best guess with significant error bars.

Additional note: found this quote in a survey paper on equating methodologies (top of page 519):

Almost all test-equating studies ignore the issue of the standard error of the equating

function.

Second, I’m really worried about the equating process and its errorbars for the following reason: the number of repeat testers varies widely depending on the demographic, and also from year to year. How then can we assess performance on the “linking questions” (the questions that are repeated on different tests) if some kids (in fact the kids more likely to be practicing for the test) are seeing them repeatedly? Is that controlled for, and how? Are they removing repeat testers?

This brings me to my main complaint about all of this. Why is the SAT equating methodology not open source? Isn’t the proprietary “intellectual property” in the test itself? Am I missing a link? I’d really like to take a look. Even better of course if the methodology is open source (as in there’s an available script which actually computes the scores starting with raw data) and the data is also available with anonymization of course.

Back from Strata Jumpstart

So I gave my talk yesterday at the Strata Jumpstart conference, and I’ll be back on Thursday and Friday to attend the Strata Conference conference.

I was delighted to meet a huge number of fun, hopeful, and excited nerds throughout the day. Since my talk was pretty early in the morning, I was able to relax afterwards and just enjoy all the questions and remarks that people wanted to discuss with me.

Some were people with lots of data, looking for data scientists who could analyze it for them, others were working with packs of data scientists (herds? covens?) and were in search of data. It was fun to try to help them find each other, as well as to hear about all the super nerdy and data-driven businesses that are getting off the ground right now. It certainly was an optimistic tone, I didn’t feel like we were in the middle of a double-dip recession for the entire day (well, at least til I got home and looked at the Greek default news).

Conferences like these are excellent; they allow people to get together and learn each others’ languages and the existence of the new tools and techniques in use or in development. They also save people lots of time, make fast connection that would otherwise difficult or impossible, and of course sometimes inspire great new ideas. Too bad they are so expensive!

I also learned that there’s such thing as a “data scientist in residence,” held of course by very few people, which is the equivalent in academic math to having a gig at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Wow. I still haven’t decided whether I’d want such a cushy job. After all, I think I learn the most when I have reasonable pressure to get stuff done with actual data. On the other hand maybe that much freedom would allow one to do really cool stuff. Dunno.

The pandas module and the IPython notebook

Last night I attended this Meetup on a cool package that Wes McKinney has been writing (in python and in cython, which I guess is like python but is as fast as c). That guys has been ridiculously prolific in his code, and we can all thank him for it, because pandas looks really useful.

To sum up what he’s done: he’s imported the concept of the R dataframe into python, with SQL query-like capabilities as well, and potentially with some map-reduce functionality, although he hasn’t tested it on huge data. He’s also in the process of adding “statsmodel” functionality to the dataframe context (he calls a dataframe a Series), with more to come soon he’s assured us.

So for example he demonstrated how quickly one could regress various stocks against each other, and if we had a column of dates and months (so actually hierarchical labels of the data), then you could use a “groupby” statement to regress within each month and year. Very cool!

He demonstrated all of this within his IPython Notebook, which seems to demonstrate lots of what I liked when I learned about Elastic-R (though not all, like the cloud computing part of Elastic-R is just awesome), namely the ability to basically send your python session to someone like a website url and to collaborate. Note, I just saw the demo I can’t speak from personal experience, but hopefully I will be able to soon! It’s a cool way to remotely use a powerful machine and not need to worry about your local setup.

What are the chances that this will work?

One of the positive things about working at D.E. Shaw was the discipline shown in determining whether a model had a good chance of working before spending a bunch of time on it. I’ve noticed people could sometimes really use this kind of discipline, both in their data mining projects and in their normal lives (either personal lives or with their jobs).

Some of the relevant modeling questions were asked and quantified:

- How much data do you expect to be able to collect? Can you pool across countries? Is there proxy historical data?

- How much signal do you estimate could be in that data? (Do you even know what the signal is you’re looking for?)

- What is the probability that this will fail? (not good) That it will fail quickly? (good)

- How much time will it take to do the initial phase of the modeling? Subsequent phases?

- What is the scope of the model if it works? International? Daily? Monthly?

- How much money can you expect from a model like this if it works? (takes knowing how other models work)

- How much risk would a model like this impose?

- How similar is this model to other models we already have?

- What are the other models that you’re not doing if you do this one, and how do they compare in overall value?

Even if you can’t answer all of these questions, they’re certainly good to ask. Really we should be asking questions like these about lots of projects we take on in our lives, with smallish tweaks:

- What are the resources I need to do this? Am I really collecting all the resources I need? What are the resources that I can substitute for them?

- How good are my resources? Would better quality resources help this work? Do I even have a well-defined goal?

- What is the probability this will fail? That it will fail quickly?

- How long will I need to work on this before deciding whether it is working? (Here I’d say write down a date and stick to it. People tend to give themselves too much extra time doing stuff that doesn’t seem to work)

- What’s the best case scenario?

- How much am I going to learn from this?

- How much am I going to grow from doing this?

- What are the risks of doing this?

- Have I already done this?

- What am I not doing if I do this?

Meetups

I wanted to tell you guys about Meetup.com, which is a company that helps people form communities to share knowledge and techniques as well as to have pizza and beer. It’s kind of like taking the best from academics (good talks, interested and nerdy audience) and adding immediacy and relevance; I’ve been using stuff I learned at Meetups in my daily job.

I’m involved in three Meetup groups. The first is called NYC Machine Learning, and they hold talks every month or so which are technical and really excellent and help me learn this new field, and in particular the vocabulary of machine learners. For example at this recent meeting, on the cross-entropy method.

The second Meetup group I go to is called New York Open Statistical Programming Meetup, and there the focus is more on recent developments in open source programming languages. It’s where I first heard of Elastic R for example, and it’s super cool; I’m looking forward to this week’s talk entitled “Statistics and Data Analysis in Python with pandas and statsmode“. So as you can see the talks really combine technical knowledge with open source techniques. Very cool and very useful, and also a great place to meet other nerdy startuppy data scientists and engineers.

The third Meetup group I got to is called Predictive Analytics. Next month they’re having a talk to discuss Bayesians vs. frequentists, and I’m hoping for a smackdown with jello wrestling. Don’t know who I’ll root for, but it will be intense.

What is “publicly available data”?

As many of you know, I am fascinated with the idea of an open source ratings model, set up to compete with the current big three ratings agencies S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch. Please check out my previous posts here and here about this idea.

For that reason, I’ve recently embarked on the following thought experiment: what would it take to start such a thing? As is the case with most things quantitative and real-world, the answer is data. Lots of it.

There’s good news and bad news. The good news is there are perfectly reasonable credit models that use only “publicly available data”, which is to say data that can theoretically gleaned from quarterly filings that companies are required to file. The bad news is, the SEC filings, although available on the web, are completely useless unless you have a team of accounting professionals working with you to understand them.

Indeed what actually happens if you work at a financial firm and want to implement a credit model based on “publicly available information” is the following: you pay a data company like Compustat good money for a clean data feed to work with. They charge a lot for this, and for good reason: the SEC doesn’t require companies to standardize their accounting terms, even within an industry, and even over time (so the same company can change the way it does its accounting from quarter to quarter). Here‘s a link for the white paper (called The Impact of Disparate Data Standardization on Company Analysis) which explains the standardization process that they go through to “clean the data”. It’s clearly a tricky thing requiring true accounting expertise.

To sum up the situation, in order to get “publicly available data” into usable form we need to give a middle-man company like Compustat thousands of dollars a year. Wait, WTF?!!? How is that publicly available?

And who is this benefitting? Obviously it benefits Compustat itself, in that there even is a business to be made from converting publicly available data into usable data. Next, it obviously benefits the companies to not have to conform to standards- easier for them to hide stuff they don’t like (this is discussed in the first section of Compustat’s whitepaper referred to above), and to have options each quarter on how the presentation best suits them. So… um… does it benefit anyone besides them? Certainly not any normal person who wants to understand the creditworthiness of a given company. Who is the SEC working for anyway?

I’ve got an idea. We should demand publicly available data to be usable. Standard format, standard terminology, and if there are unavoidable differences across industries (which I imagine there are, since some companies store goods and others just deal in information for example), then there should be fully open-source translation dictionaries written in some open-source language (python!) that one can use to standardize the overall data. And don’t tell me it can’t be done, since Compustat already does it.

SEC should demand the companies file in a standard way. If there really are more than a couple of standard terms, then demand the company report in each standard way. I’m sure the accountants of the company have this data, it’s just a question of requiring them to report it.

Back!

I’m back from vacation, and the sweet smell of blog has been calling to me. Big time. I’m too tired from Long Island Expressway driving to make a real post now, but I have a few things to throw your way tonight:

First, I’m completely loving all of the wonderful comments I continue to receive from you, my wonderful readers. I’m particularly impressed with the accounting explanation on my recent post about the IASP and what “level 3” assets are. Here is a link to the awesome comments, which has really turned into a conversation between sometimes guest blogger FogOfWar and real-life accountant GMHurley who knows his shit. Very cool and educational.

Second, my friend and R programmer Daniel Krasner has finally buckled and started a blog of his very own, here. It’s a resource for data miners, R or python programmers, people working or wanting to work at start-ups, and thoughtful entrepreneurs. In his most recent post he considers how smart people have crappy ideas and how to focus on developing good ones.

Finally, over vacation I’ve been reading anarchist David Graeber‘s new book about debt, and readers, I think I’m in love. In a purely intellectual and/or spiritual way, of course, but man. That guy can really rile me up. I’ll write more about his book soon.

Strata data conference

So I’m giving a talk at this conference. I’m talking on Monday, September 19th, to business people, about how they should want to hire a data scientist (or even better, a team of data scientists) and how to go about hiring someone awesome.

Any suggestions?

And should I wear my new t-shirt when I’m giving my talk? Part of the proceeds of these sexy and funny data t-shirts goes to Data Without Borders! A great cause!

Why log returns?

There’s a nice blog post here by Quantivity which explains why we choose to define market returns using the log function:

where denotes price on day

.

I mentioned this question briefly in this post, when I was explaining how people compute market volatility. I encourage anyone who is interested in this technical question to read that post, it really explains the reasoning well.

I wanted to add two remarks to the discussion, however, which actually argue for not using log returns, but instead using percentage returns in some situations.

The first is that the assumption of a log-normal distribution of returns, especially over a longer term than daily (say weekly or monthly) is unsatisfactory, because the skew of log-normal distribution is positive, whereas actual market returns for, say, S&P is negatively skewed (because we see bigger jumps down in times of panic). You can get lots of free market data here and try this out yourself empirically, but it also makes sense. Therefore when you approximate returns as log normal, you should probably stick to daily returns.

Second, it’s difficult to logically combine log returns with fat-tailed distributional assumptions, even for daily returns, although it’s very tempting to do so because assuming “fat tails” sometimes gives you more reasonable estimates of risk because of the added kurtosis. (I know some of you will ask why not just use no parametric family at all and just bootstrap or something from the empirical data you have- the answer is that you don’t ever have enough to feel like that will be representative of rough market conditions, even when you pool your data with other similar instruments. So instead you try different parametric families and compare.)

Mathematically there’s a problem: when you assume a student-t distribution (a standard choice) of log returns, then you are automatically assuming that the expected value of any such stock in one day is infinity! This is usually not what people expect about the market, especially considering that there does not exist an infinite amount of money (yet!). I guess it’s technically up for debate whether this is an okay assumption but let me stipulate that it’s not what people usually intend.

This happens even at small scale, so for daily returns, and it’s because the moment generating function is undefined for student-t distributions (the moment generating function’s value at 1 is the expected return, in terms of money, when you use log returns). We actually saw this problem occur at Riskmetrics, where of course we didn’t see “infinity” show up as a risk number but we saw, every now and then, ridiculously large numbers when we let people combine “log returns” with “student-t distributions.” A solution to this is to use percentage returns when you want to assume fat tails.

What is the mission statement of the mathematician?

In the past five years, I’ve been learning a lot about how mathematics is used in the “real world”. It’s fascinating, thought provoking, exciting, and truly scary. Moreover, it’s something I rarely thought about when I was in academics, and, I’d venture to say, something that most mathematicians don’t think about enough.

It’s weird to say that, because I don’t want to paint academic mathematicians as cold, uncaring or stupid. Indeed the average mathematician is quite nice, wants to make the world a better place (at least abstractly), and is quite educated and knowledgeable compared to the average person.

But there are some underlying assumptions that mathematicians make, without even noticing, that are pretty much wrong. Here’s one: mathematicians assume that people in general understand the assumptions that go into an argument (and in particular understand that there always are assumptions). Indeed many people go into math because of the very satisfying way in which mathematical statements are either true or false- this is one of the beautiful things about mathematical argument, and its consistency can give rise to great things: hopefulness about the possibility of people being able to sort out their differences if they would only engage in rational debate.

For a mathematician, nothing is more elevating and beautiful than the idea of a colleague laying out a palette of well-defined assumptions, and building a careful theory on top of that foundation, leading to some new-found clarity. It’s not too crazy, and it’s utterly attractive, to imagine that we could apply this kind of logical process to situations that are not completely axiomatic, that are real-world, and that, as long as people understand the simplifying assumptions that are made, and as long as they understand the estimation error, we could really improve understanding or even prediction of things like the stock market, the education of our children, global warming, or the jobless rate.

Unfortunately, the way mathematical models actually function in the real world is almost the opposite of this. Models are really thought of as nearly magical boxes that are so complicated as to render the results inarguable and incorruptible. Average people are completely intimidated by models, and don’t go anywhere near the assumptions nor do they question the inner workings of the model, the question of robustness, or the question of how many other models could have been made with similar assumptions but vastly different results. Typically people don’t even really understand the idea of errors.

Why? Why are people so trusting of these things that can be responsible for so many important (and sometimes even critical) issues in our lives? I think there are (at least) two major reasons. One touches on things brought up in this article, when it talks about information replacing thought and ideas. People don’t know about how the mortgage models work. So what? They also don’t know how cell phones work or how airplanes really stay up in the air. In some way we are all living in a huge network of trust, where we leave technical issues up to the experts, because after all we can’t be experts in everything.

But there’s another issue altogether, which is why I’m writing this post to mathematicians. Namely, there is a kind of scam going on in the name of mathematics, and I think it’s the responsibility of mathematicians to call it out and refuse to let it continue. Namely, people use the trust that people have of mathematics to endow their models with trust in an artificial and unworthy way. Much in the way that cops flashing their badges can abuse their authority, people flash the mathematics badge to synthesize mathematical virtue.

I think it’s time for mathematicians to start calling on people to stop abusing people’s trust in this way. One goal of this blog is to educate mathematicians about how modeling is used, so they can have a halfway decent understanding of how models are created and used in the name of mathematics, and so mathematicians can start talking about where mathematics actually plays a part and where politics, or greed, or just plain ignorance sometimes takes over.

By the way, I think mathematicians also have another responsibility which they are shirking, or said another way they should be taking on another project, which is to educate people about how mathematics is used. This is very close to the concept of “quantitative literacy” which is explained in this recent article by Sol Garfunkel and David Mumford. I will talk in another post about what mathematicians should be doing to promote quantitative literacy.

Lagged autocorrelation plots

I wanted to share with you guys a plot I drew with python the other night (the code is at the end of the post) using blood glucose data that I’ve talked about previously in this post and I originally took a look at in this post.

First I want to motivate lagged autocorrelation plots. The idea is, given that you want to forecast something, say in the form of a time series (so a value every day or every ten minutes or whatever), the very first thing you can do is try to use past values to forecast the next value. In other words, you want to squeeze as much juice out of that orange as you can before you start using outside variable to predict future values.

Of course this won’t always work- it will only work, in fact, if there’s some correlation between past values and future values. To estimate how much “signal” there is in such an approach, we draw the correlation between values of the time series for various lags. At no (=0) lag, we are comparing a time series to itself so the correlation is perfect (=1). Typically there are a few lags after 0 which show some positive amount of correlation, then it quickly dies out.

We could also look at correlations between returns of the values, or differences of the values, in various situations. It depends on what you’re really trying to predict: if you’re trying to predict the change in value (which is usually what quants in finance do, since they want to bet on stock market changes for example), probably the latter will make more sense, but if you actually care about the value itself, then it makes sense to compute the raw correlations. In my case, since I’m interested in forecasting the blood glucose levels, which essentially have maxima and minima, I do care about the actual number instead of just the relative change in value.

Depending on what kind of data it is, and how scrutinized it is, and how much money can be made by betting on the next value, the correlations will die out more quickly. Note that, for example, if you did this with daily S&P returns and saw a nontrivial positive correlation after 1 lag, so the next day, then you could have a super simple model, namely bet that whatever happened yesterday will happen again today, and you would statistically make money on that model. At the same time, it’s a general fact that as “the market” recognizes and bets on trends, they tend to disappear. This means that such a simple, positive one-day correlation of returns would be “priced in” very quickly and would therefore disappear with new data. This tends to happen a lot with quant models- as the market learns the model, the predictability of things decreases.

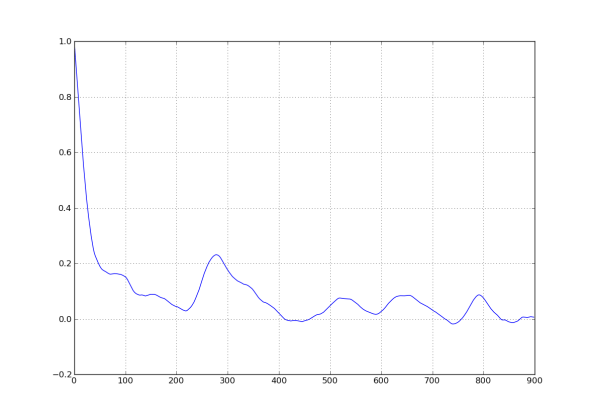

However, in cases where there’s less money riding on the patterns, we can generally expect to see more linkage between lagged values. Since nobody is making money betting on blood glucose levels inside someone’s body, I had pretty high hopes for this analysis. Here’s the picture I drew:

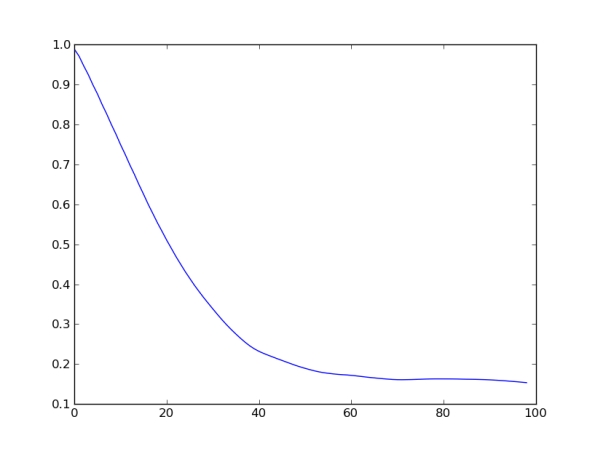

What do you see? Basically I want you to see that the correlation is quite high for small lags, then dies down with a small resuscitation near 300 (hey, it turns out that 288 lags equals one day! So this autocorrelation lift is probably indicating a daily cyclicality of blood glucose levels). Here’s a close-up for the first 100 lags:

We can conclude that the correlation seems significant to about 30 lags, and is decaying pretty linearly.

This means that we can use the previous 30 lags to predict the next level. Of course we don’t want to let 30 parameters vary independently- that would be crazy and would totally overfit the model to the data. Instead, I’ll talk soon about how to place a prior on those 30 parameters which essentially uses them all but doesn’t let them vary freely- so the overall number of independent variables is closer to 4 or 5 (although it’s hard to be precise).

On last thing: the data I have used for this analysis is still pretty dirty, as I described here. I will do this analysis again once I decide how to try to remove crazy or unreliable readings that tend to happen before the blood glucose monitor dies.

Here’s the python code I used to generate these plots:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import csv

from matplotlib.pylab import *

import os

from datetime import datetime

os.chdir('/Users/cathyoneil/python/diabetes/')

gap_threshold = 12

dataReader = csv.DictReader(open('Jason_large_dataset.csv', 'rb'), delimiter=',', quotechar='|')

i=0

datelist = []

datalist = []

firstdate = 4

skip_gaps_datalist = []

for row in dataReader:

#print i, row["Sensor Glucose (mg/dL)"]

if not row["Raw-Type"] == "GlucoseSensorData":continue

if firstdate ==4:

print i

firstdate = \

datetime.strptime(row["Timestamp"], '%m/%d/%y %H:%M:%S')

if row["Sensor Glucose (mg/dL)"] == "":

datalist.append(-1)

else:

thisdate = datetime.strptime(row["Timestamp"], '%m/%d/%y %H:%M:%S')

diffdate = thisdate-firstdate

datelist.append(diffdate.seconds + 60*60*24*diffdate.days)

datalist.append(float(row["Sensor Glucose (mg/dL)"]))

skip_gaps_datalist.append(log(float(row["Sensor Glucose (mg/dL)"])))

i+=1

continue

print min(datalist), max(datalist)

##figure()

##scatter(arange(len(datalist)), datalist)

##

##figure()

##hist(skip_gaps_datalist, bins = 100)

##show()

def lagged_correlation(g):

d = dict(zip(datelist, datalist))

s1 = []

s2 = []

for date in datelist:

if date + 60*5 in datelist:

s1.append(d[date])

s2.append(d[date + 60*5])

return corrcoef(s1, s2)[1, 0]

figure()

plot([lagged_correlation(f) for f in range(1,900)])

Demographics: sexier than you think

It has been my unspoken goal of this blog to sex up math (okay, now it’s a spoken goal). There are just too many ways math, and mathematical things, are portrayed and conventionally accepted as boring and dry, and I’ve taken on the task of making them titillating to the extent possible. Anybody who has ever personally met me will not be surprised by this.

The reason I mention this is that today I’ve decided to talk about demographics, which may be the toughest topic yet to rebrand in a sexy light – even the word ‘demographics’ is bone dry (although there have been lots of nice colorful pictures coming out from the census). So here goes, my best effort:

Demographics

Is it just me, or have there been a weird number of articles lately claiming that demographic information explain large-scale economic phenomena? Just yesterday there was this article, which claims that, as the baby boomers retire they will take money out of the stock market at a sufficient rate to depress the market for years to come. There have been quite a few articles lately explaining the entire housing boom of the 90’s was caused by the boomers growing their families, redefining the amount of space we need (turns out we each need a bunch of rooms to ourselves) and growing the suburbs. They are also expected to cause another problem with housing as they retire.

Of course, it’s not just the boomers doing these things. It’s more like, they have a critical mass of people to influence the culture so that they eventually define the cultural trends of sprawling suburbs and megamansions and redecorating kitchens, which in turn give rise to bizarre stores like ‘Home Depot Expo‘. Thanks for that, baby boomers. Or maybe it’s that the marketers figure out how boomers can be manipulated and the marketers define the trends. But wait, aren’t the marketers all baby boomers anyway?

I haven’t read an article about it, but I’m ready to learn that the dot com boom was all about all of the baby boomers having a simultaneous midlife crisis and wanting to get in on the young person’s game, the economic trend equivalent of buying a sports car and dating a 25-year-old.

Then there are countless articles in the Economist lately explaining even larger scale economic trends through demographics. Japan is old: no wonder their economy isn’t growing. Europe is almost as old, no duh, they are screwed. America is getting old but not as fast as Europe, so it’s a battle for growth versus age, depending on how much political power the boomers wield as they retire (they could suck us into Japan type growth).

And here’s my favorite set of demographic forecasts: China is growing fast, but because of the one child policy, they won’t be growing fast for long because they will be too old. And that leaves India as the only superpower in the world in about 40 years, because they have lots of kids.

So there you have it, demographics is sexy. Just in case you missed it, let me go over it once again with the logical steps revealed:

Demographics – baby boomers – Bill Clinton – Monica Lewinsky – blow job under the desk. Got it?

Machine learners are spoiled for data

I’ve been reading lots of machine learning books lately, and let me say, as a relative outsider coming from finance: machine learners sure are spoiled for data.

It’s like, they’ve built these fancy techniques and machines that take a huge amount of data and try to predict an outcome, and they always seem to start with about 50 possible signals and “learn” the right combination of a bunch of them to be better at predicting. It’s like that saying, “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

In finance, a quant gets maybe one or two or three time series, hopefully that haven’t been widely distributed so they may still have signal. The effect that this new data on a quant is key: it’s exciting almost to the point of sexually arousing to get new data. That’s right, I said it, data is sexy! We caress the data, we kiss it and go to bed with it every night (well, the in-sample part of it anyway). In the end we have an intimate relationship with each and every time series in our model. In terms of quantity, however, maybe it’s daily (so business days, 262 days per year about), for maybe 15 years, so altogether 4000 data points. Not a lot to work with but we make do.

In particular, given 50 possible signals in a pile of new data, we would first look at each time series by plotting, to be sure it’s not dirty, we’d plot the (in-sample) returns as a histogram to see what we’re dealing with, we’d regress each against the outcome, to see if anything contained signal. We’d draw lagged correlation graphs of each against the outcome. We’d draw cumulative pnl graphs over time with that univariate regression for that one potential signal at a time.

In other words, we’d explore the data in a careful, loving manner, signal by signal, without taking the data for granted, instead of stuffing the kit and kaboodle into a lawnmower. It’s more work but it means we have a sense of what’s going into the model.

I’m wondering how powerful it would be to combine the two approaches.

How the Value-Added Model sucks

One way people’s trust of mathematics is being abused by crappy models is through the Value-Added Model, or VAM, which is actually a congregation of models introduced nationally to attempt to assess teachers and schools and their influence on the students.

I have a lot to say about the context in which we decide to apply a mathematical model to something like this, but today I’m planning to restrict myself to complaints about the actual model. Some of these complaints are general but some of them are specific to the way the one in New York is set up (still a very large example).

The general idea of a VAM is that teachers are rewarded for bringing up their students’ test scores more than expected, given a bunch of context variables (like their poverty and last year’s test scores).

The very first question one should ask is, how good is the underlying test the kids are taking? This is famously a noisy answer, depending on how much sleep and food the kids got that day, and, with respect to the content, depends more on memory than on deep knowledge. Another way of saying this is that, if a student does a mediocre job on the test, it could be because they are learning badly at their school, or that they didn’t eat breakfast, or it could be that the teachers they have are focusing more on other things like understanding the reasons for the scientific method and creating college-prepared students by focusing on skills of inquiry rather than memorization.

This brings us to the next problem with VAM, which is a general problem with test-score cultures, namely that it is possible to teach to the test, which is to say it’s possible for teachers to chuck out their curriculums and focus their efforts on the students doing well on the test (which in middle school would mean teaching only math and English). This may be an improvement for some classrooms but in general is not.

People’s misunderstanding of this point gets to the underlying problem of skepticism of our teachers’ abilities and goals- can you imagine if, at your job, you were mistrusted so much that everyone thought it would be better if you were just given a series of purely rote tasks to do instead of using your knowledge of how things should be explained or introduced or how people learn? It’s a fact that teachers and schools that don’t teach to the test are being punished for this under the VAM system. And it’s also a fact that really good, smart teachers who would rather be able to use their pedagogical chops in an environment where they are being respected leave public schools to get away from this culture.

Another problem with the New York VAM is the way tenure is set up. The system of tenure is complex in its own right, and I personally have issues with it (and with the system of tenure in general), but in any case here’s the way it works now. New teachers are technically given three years to create a portfolio for tenure- but the VAM results of the third year don’t come back in time, which means the superintendent looking at a given person’s tenure folder only sees two years of scores, and one of them is the first year, where the person was completely inexperienced.

The reason this matters is that, depending on the population of kids that new teacher was dealing with, more or less of the year could have been spent learning how to manage a classroom. This is an effect that overall could be corrected for by a model but there’s no reason to believe was. In other words, the overall effect of teaching to kids who are difficult to manage in a classroom could be incorporated into a model but the steep learning curve of someone’s first year would be much harder to incorporate. Indeed I looked at the VAM technical white paper and didn’t see anything like that (although since the paper was written for the goal of obfuscation that doesn’t prove anything).

For a middle school teacher, the fact that they have only two years of test scores (and one year of experienced scores) going into a tenure decision really matters. Technically the breakdown of weights for their overall performance is supposed to be 20% VAM, 20% school-wide assessment, and 60% “subjective” performance evaluation, as in people coming to their classroom and taking notes. However, the superintendent in charge of looking at the folders has about 300 folders to look at in 2 weeks (an estimate), and it’s much easier to look at test scores than to read pages upon pages of written assessment. So the effective weighting scheme is measurably different, although hard to quantify.

One other unwritten rule: if the school the teacher is at gets a bad grade, then that teacher’s chances of tenure can be zero, even if their assessment is otherwise good. This is more of a political thing than anything else, in that Bloomberg doesn’t want to say that a “bad” school had a bunch of tenures go through. But it means that the 20/20/60 breakdown is false in a second way, and it also means that the “school grade” isn’t an independent assessment of the teachers’ grades- and the teachers get double punished for teaching at a school that has a bad grade.

That brings me to the way schools are graded. Believe it or not the VAM employs a binning system when they correct for poverty, which is measured in terms of the percentage of the student population that gets free school lunches. The bins are typically small ranges of percentages, say 20-25%, but the highest bin is something like 45% and higher. This means that a school with 90% of kids getting free school lunch is expected to perform on tests similarly to a school with half that many kids with unstable and distracting home lives. This penalizes the schools with the poorest populations, and as we saw above penalized the teachers at those schools, by punishing them for when the school gets a bad grade. It’s my opinion that there should never be binning in a serious model, for reasons just like this. There should always be a continuous function that is fit to the data for the sake of “correcting” for a given issue.

Moreover, as a philosophical issue, these are the very schools that the whole testing system was created to help (does anyone remember that testing was originally set up to help identify kids who struggle in order to help them?), but instead we see constant stress on their teachers, failed tenure bids, and the resulting turnover in staff is exactly the opposite of helping.

This brings me to a crucial complaint about VAM and the testing culture, namely that the emphasis put on these tests, which we’ve seen is noisy at best, reduces the quality of life for the teachers and the schools and the students to such an extent that there is no value added by the value added model!

If you need more evidence of this please read this article, which describes the rampant cheating on test in Atlanta, Georgia and which is in my opinion a natural consequence of the stress that tests and VAM put on school systems.

One last thing- a political one. There is idiosyncratic evidence that near elections, students magically do better on tests so that candidates can talk about how great their schools are. With that kind of extra variance added to the system, how can teachers and school be expected to reasonably prepare their curriculums?

Next steps: on top of the above complaints, I’d say the worst part of the VAM is actually that nobody really understands it. It’s not open source so nobody can see how the scores are created, and the training data is also not available, so nobody can argue with the robustness of the model either. It’s not even clear what a measurement of success is, and whether anyone is testing the model for success. And yet the scores are given out each year, with politicians adding their final bias, and teachers and schools are expected to live under this nearly random system that nobody comprehends. Things can and should be better than this. I will talk in another blog post about how they should be improved.

What’s with errorbars?

As an applied mathematician, I am often asked to provide errorbars with values. The idea is to give the person reading a statistic or a plot some idea of how much the value or values could be expected to vary or be wrongly estimated, or to indicate how much confidence one has in the statistic. It’s a great idea, and it’s always a good exercise to try to provide the level of uncertainty that one is aware of when quoting numbers. The problem is, it’s actually very tricky to get them right or to even know what “right” means.

A really easy way to screw this up is to give the impression that your data is flawless. Here’s a prime example of this.

More recently we’ve seen how much the government growth rate figures can really suffer from lack of error bars- the market reacts to the first estimate but the data can be revised dramatically later on. This is a case where very simple errorbars (say, showing the average size of the difference between first and final estimates of the data) should be provided and could really help us gauge confidence. [By the way, it also brings up another issue which most people think about as a data issue but really is just as much a modeling issue: when you have data that gets revised, it is crucial to save the first estimates, with a date on that datapoint to indicate when it was first known. If we instead just erase the old estimate and pencil in the new, without changing the date (usually leaving the first date), then it gives us a false sense that we knew the “corrected” data way earlier than we did.]

However, even if you don’t make stupid mistakes, you can still be incredibly misleading, or misled, by errorbars. For example, say we are trying to estimate risk on a stock or a portfolio of stocks. Then people typically use “volatility error bars” to estimate the expected range of values of the stock tomorrow, given how it’s been changing in the past. As I explained in this post, the concept of historical volatility depends crucially on your choice of how far back you look, which is given by a kind of half-life, or equivalently the decay constant. Anything that is so not robust should surely be taken with a grain of salt.

But in any case, volatility error bars, which are usually designed to be either one or two lengths of the measured historical volatility, contain only as much information as the data in the lookback window. In particular, you can get extremely confused if you assume that the underlying distribution of returns is normal, which is exactly what most people do in fact assume, even when they don’t realize they do.

To demonstrate this phenomenon of human nature, recall that during the credit crisis you’d hear things like “We were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row,” from Goldman Sachs; the implication was that this was an incredibly unlikely event, near probability zero in fact, that nobody could have foreseen. Considering what we’ve been seeing in the market in the past couple of weeks, it would be nice to understand this statement.

There were actually two flawed assumptions exposed here. First, if we have a fat-tailed distribution, then things can seem “quiet” for long stretches of time (longer than any lookback window), during which the sample volatility is a possibly severe underestimate of the standard of deviation. Then when a fat-tailed event occurs, the sample volatility spikes to being an overestimate of the standard of deviation for that distribution.

Second, in the markets, there is clustering of volatility- another way of saying this is that volatility itself is rather auto-correlated, so even if we can’t predict the direction of the return, we can still estimate the size of the return. So once the market dives 5% in one day, you can expect many more days of large moves.

In other words, the speaker was measuring the probability that we’d see several returns, 25 standard deviations away from the mean, if the distribution is normal, with a fixed standard deviation, and the returns are independent. This is indeed a very unlikely event. But in fact we aren’t dealing with normal distributions nor independent draws.

Another way to work with errorbars is to have confidence errorbars, which relies (explicitly or implicitly) on an actual distributional assumption of your underlying data, and which tells the reader how much you could expect the answer to range given the amount of data you have, with a certain confidence. Unfortunately, there are problems here too- the biggest one being that there’s really never any reason to believe your distributional assumptions beyond the fact that it’s probably convenient, and that so far the data looks good. But if it’s coming from real world stuff, a good level of skepticism is healthy.

In another post I’ll talk a bit more about confidence errorbars, otherwise known as confidence intervals, and I’ll compare them to hypothesis testing.

Open Source Ratings Model (Part 2)

I’ve thought more about the concept of an open source ratings model, and I’m getting more and more sure it’s a good idea- maybe an important one too. Please indulge me while I passionately explain.

First, this article does a good job explaining the rot that currently exists at S&P. The system of credit ratings undermines the trust of even the most fervently pro-business entrepreneur out there. The models are knowingly games by both sides, and it’s clearly both corrupt and important. It’s also a bipartisan issue: Republicans and Democrats alike should want transparency when it comes to modeling downgrades- at the very least so they can argue against the results in a factual way. There’s no reason I can see why there shouldn’t be broad support for a rule to force the ratings agencies to make their models publicly available. In other words, this isn’t a political game that would score points for one side or the other.

Second, this article discusses why downgrades, interpreted as “default risk increases” on sovereign debt doesn’t really make sense- and uses as example Japan, which was downgraded in 2002 but still continues to have ridiculously low market-determined interest rates. In other words, ratings on governments, at least the ones that can print their own money (so not Greece), should be taken as a metaphor of their fiscal problems, or perhaps as a measurement of the risk that they will have potentially spiraling inflation when they do print their way out of a mess. An open source quantitative model would not directly try to model the failure of politicians to agree (although there are certainly market data proxies for that kind of indecision), and that’s ok: probably the quantitative model’s grade on sovereign default risk trained on corporate bonds would still give real information, even if it’s not default likelihood information. And, being open-source, it would at least be clear what it’s measuring and how.

I’ve also gotten a couple excellent comments already on my first post about this idea which I’d like to quickly address.

There’s a comment pointing out that it would take real resources to do this and to do it well: that’s for sure, but on the other hand it’s a hot topic right now and people may really want to sponsor it if they think it would be done well and widely adopted.

Another commenter had concerns of the potential for vandals to influence and game the model. But here’s the thing, the point of open source is that, although it’s impossible to avoid letting some people have more influence than others on the model (especially the maintainer), this risk is mitigated in two important ways. First of all it’s at least clear what is going on, which is way more than you can say for S&P, where there was outrageous gaming going on and nobody knew (or more correctly nobody did anything about it). Secondly, and more importantly, it’s always possible for someone to fork the open source model and start their own version if they think it’s become corrupt or too heavily influenced by certain methodologies or modeling choices. As they say, if you don’t like it, fork it.

Update! There’s a great article here about how the SEC is protecting the virtual ratings monopoly of S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch.

Open Source Ratings Model?

A couple of days ago I got this comment from a reader, which got me super excited.

His proposal is that we could start an open source ratings model to compete with S&P and Moody’s and Fitch ratings. I have made a few relevant lists which I want to share with you to address this idea.

Reasons to have an open source ratings model:

- The current rating agencies have a reputation for bad modeling; in particular, their models, upon examination, often have extremely unrealistic underlying assumptions. This could be rooted out and modified if a community of modelers and traders did their honest best to realistically model default.

- The current ratings agencies also have enormous power, as exemplified in the past few days of crazy volatile trading after S&P downgraded the debt of the U.S. (although the European debt problems are just as much to blame for that I believe). An alternative credit model, if it was well-known and trusted, would dilute their power.

- Although the rating agency shared descriptions of their models with their clients, they weren’t in fact open-source, and indeed the level of exchange probably served only to allow the clients to game the models. One of the goals of an open-source ratings model would be to avoid easy gaming.

- Just to show you how not open source S&P is currently, check out this article where they argue that they shouldn’t have to admit their mistakes. When you combine the power they wield, their reputation for sloppy reasoning, and their insistence on being protected from their mistakes, it is a pretty idiotic system.

- The ratings agencies also have a virtual lock on their industry- it is in fact incredibly difficult to open a new ratings agency, as I know from my experience at Riskmetrics, where we looked into doing so. By starting an open source ratings model, we can (hopefully) avoid issues like permits or whatever the problem was by not charging money and just listing free opinions.

Obstructions to starting an open source ratings model:

- It’s a lot of work, and we would need to set it up in some kind of wiki way so people could contribute to it. In fact it would have to me more Linux style, where some person or people maintain the model and the suggestions. Again, lots of work.

- Data! A good model requires lots of good data. Altman’s Z-score default model, which friends of mine worked on with him at Riskmetrics and then MSCI, could be the basis of an open source model, since it is being published. But the data that trains the model isn’t altogether publicly available. I’m working on this, would love to hear readers’ comments.

What is an open source model?

- The model itself is written in an open source language such as python or R and is publicly available for download.

- The data is also publicly available, and together with the above, this means people can download the data and model and change the parameters of the model to test for robustness- they can also change or tweak the model themselves.

- There is good documentation of the model describing how it was created.

- There is an account kept of how often different models are tried on the in-sample data. This prevents a kind of data fitting that people generally don’t think about enough, namely trying so many different models on one data set that eventually some model will look really good.

Data Viz

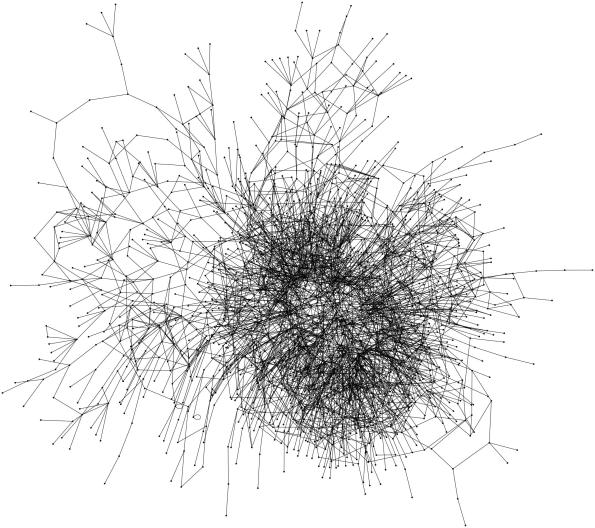

The picture below is a visualization of the complexity of algebra. The vertices are theorems and the edges between theorems are dependencies. Technically the edges should be directed, since if Theorem A depends on Theorem B, we shouldn’t have it the other way around too!

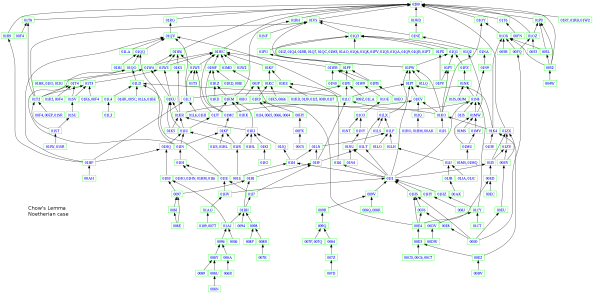

This comes from data mining my husband’s open source Stacks Project; I should admit that, even though I suggested the design of the picture, I didn’t implement it! My husband used graphviz to generate this picture – it puts heavily connected things in the middle and less connected things on the outside. I’ve also used graphviz to visualize the connections in databases (MySQL automatically generates the graph).

Here’s another picture which labels each vertex with a tag. I designed the tag system, which gives each theorem a unique identifier; the hope is that people will be willing to refer to the theorems in the project even though their names and theorem numbers may change (i.e. Theorem 1.3.3 may become Theorem 1.3.4 if someone adds a new result in that section). It’s also directed, showing you dependency (Theorem A points to Theorem B if you need Theorem A to prove Theorem B). This visualizes the results needed to prove Chow’s Lemma: