Archive

The complexity feedback loop of modeling

Yesterday I was interviewed by a tech journalist about the concept of feedback loops in consumer-facing modeling. We ended up talking for a while about the death spiral of modeling, a term I coined for the tendency of certain public-facing models, like credit scoring models, to have such strong effects on people that they arguable create the future rather than forecast it. Of course this is generally presented from the perspective of the winners of this effect, but I care more about who is being forecast to fail.

Another feedback loop that we talked about was one that consumers have basically inheriting from the financial system, namely the “complexity feedback loop”.

In the example she and I discussed, which had to do with consumer-facing financial planning software, the complexity feedback loop refers to the fact that we are urged, as consumers, to keep track of our finances one way or another, including our cash flows, which leads to us worrying that we won’t be able to meet our obligations, which leads to us getting convinced we need to buy some kind of insurance (like overdraft insurance), which in turn has a bunch of complicated conditions on it.

The end result is increased complexity along with an increasing need for a complicated model to keep track of finances – in other words, a feedback loop.

Of course this sounds a lot like what happened in finance, where derivatives were invented to help disperse unwanted risk, but in turn complicated the portfolios so much that nobody understand them anymore, so we have endless discussions about how to measure the risk of the instruments that were created to remove risk.

The complexity feedback loop is generalizable outside of the realm of money as well.

In general models take certain things into account and ignore others, by their nature; models are simplified versions of the world, especially when they involve human behavior. So certain risks, or effects, are sufficiently small that the original model simply doesn’t see them – it may not even collect the data to measure it at all. Sometimes this omission is intentional, sometimes it isn’t.

But once the model is widely used, then the underlying approximation to the world is in some sense assumed, and then the remaining discrepancy is what we need to start modeling: the previously invisible becomes visible, and important. This leads to a second model tacked onto the first, or a modified version of the first. In either case it’s more complicated as it becomes more widely used.

This is not unlike saying that we’ve seen more vegetarian options on menus as restauranteurs realize they are losing out on a subpopulation of diners by ignoring their needs. From this example we can see that the complexity feedback loop can be good or bad, depending on your perspective. I think it’s something we should at least be aware of, as we increasingly interact with and depend on models.

I don’t have to prove theorems to be a mathematician

I’m giving a talk at the Joint Mathematics Meeting on Thursday (it’s a 30 minute talk that starts at 11:20am, in Room 2 of the Upper Level of the San Diego Conference Center, I hope you come!).

I have to distill the talk from an hour-long talk I gave recently in the Stony Brook math department, which was stimulating.

Thinking about that talk brought something up for me that I think I want to address before the next talk. Namely, at the beginning of the talk I was explaining the title, “How Mathematics is Used Outside of Academia,” and I mentioned that most mathematicians that leave academia end up doing modeling.

I can’t remember the exact exchange, but I referred to myself at some point in this discussion as a mathematician outside of academia, at which point someone in the audience expressed incredulity:

him: Really? Are you still a mathematician? Do you prove theorems?

me: No, I don’t prove theorems any longer, now that I am a modeler… (confused look)

At the moment I didn’t have a good response to this, because he was using a different definition of “mathematician” than I was. For some reason he thought a mathematician must prove theorems.

I don’t think so. I had a conversation about this after my talk with Bob Beals, who was in the audience and who taught many years ago at the math summer program I did last summer. After getting his Ph.D. in math, Bob worked for the spooks, and now he works for RenTech. So he knows a lot about doing math outside academia too, and I liked his perspective on this question.

Namely, he wanted to look at the question through the lens of “grunt work”, which is to say all of the actual work that goes into a “result.”

As a mathematician, of course, you don’t simply sit around all day proving theorems. Actually you spend most of your time working through examples to get a feel for the terrain, and thinking up simple ways to do what seems like hard things, and trying out ideas that fail, and going down paths that are dry. If you’re lucky, then at the end of a long journey like this, you will have a theorem.

The same basic thing happens in modeling. You spend lots of time with the data, getting to know it, and then trying out certain approaches, which sometimes, or often, end up giving you nothing interesting, and half the time you realize you were expecting the wrong thing so you have to change it entirely. In the end you may end up with a model which is useful. If you’re lucky.

There’s a lot of grunt work in both endeavors, and there’s a lot of hard thinking along the way, lots of ways for you to fool yourself that you’ve got something when you haven’t. Perhaps in modeling it’s easier to lie, which is a big difference indeed. But if you’re an honest modeler then I claim the difference in the process of getting an interesting and important result is not that different.

And, I claim, I am still being a mathematician while I’m doing it.

Sunday (late) morning reading list

I wanted to share with you some things I read this week which I really enjoyed and which made me think.

- Jordan over at Quomodocumque has written the post I wish I wrote on the recent “end of history illusion” introduced in this New York Times article. Here’s the post I did write, which isn’t nearly as nerdy, annoyed, and well thought-out.

- How to halt the terrorist money train from the New York Times.

- Point: Our absurd Fear of Fat from the New York Times. I love the attention to the weight-loss industry here.

- Counterpoint: The problem with all this ‘Overweight people live longer’ news, from the Atlantic.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

After a short vacation Aunt Pythia is back to give out free advice that’s worth every penny. Go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Please submit your question at the bottom of this column (pretty please!).

Let’s first go over last time’s question for the readers:

Aunt Pythia,

Why do some foods burn when you stir them? It doesn’t make sense that my rice or pasta should burn when there is still a lot of water in the pot just because I stirred it.

Physics-Inclined Wannabe Chef

The answer to the Chef were interesting and thoughtful, although I’m not sure anyone actually whipped out the pots and ran experiments (including me!).

Leila says it’s not because you stirred it, and moreover the lesson learned is to stir more often, but JSK disagrees and thinks you can burn your rice by stirring. From JSK’s comment:

…the remaining water settles to the bottom of the pan, gradually boiling away and preventing burning at the bottom. If you stir, you distribute the water throughout the “sponge” of cooled rice above. The bottom layer of rice then burns if the heat is hot enough and the water can’t percolate back down in time to prevent the burning.

I’m gonna have to say the jury’s out. We got direct disagreement. Anyone want to produce a Mythbusters-style rice cooking show?

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m going on the academic job market for the first time. I’ve heard a lot of advice, but I’d really like Aunt Pythia’s advice: what three adjectives should I try to embody during my Joint Math Meeting (JMM) interviews?

Nervous in Nebraska

Dear Nervous,

These are going to sound pretty typical but here goes: try to appear confident, interested, and likable.

To explain why I chose those three adjectives, keep in mind that interviewing for a job is a lot like dating. You need to figure out if you like your date while, at the same time, convince your date to like you. Those are two tasks and they are both up to you, they’re your responsibility, and it’s not enough to just do one of them.

So, although you’re nervous, you need to give off “I am not depending on this to work out because I have other interviews” vibes, because first of all it’s the truth, and second of all you need to make sure your interviewer feels obligated to sell the job to you. Otherwise the entire process is all about whether you’re good enough, which is imbalanced. It should be more a discussion of whether it’s a good fit overall. Watch this video to see how that negotiation can look if it’s an incredibly funny, inappropriate, and drunk interview.

At the same time, you need to seem interested. You can’t be indifferent to the job, because that’s the kiss of death from the perspective of an interviewer. Why would I offer a job to this jerk who doesn’t even seem to want it?

Finally, keep in mind that the real question on the interviewer’s mind is whether they’d actually want to be your colleague. You need to seem like someone who would fit in to the department, both mathematically and socially. Now’s not the time to mention weird hobbies, but it is the time to mention caring about how real analysis gets taught (although don’t be too radical). You want to give the impression that you’re fun, professional, and thoughtful about being a math nerd.

I hope that helps! See you in San Diego!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

Do you think stricter gun control laws would really prevent mass shootings?

Only in Oakland

Dear OiO,

Why, yes, I do, and even more importantly I think they’d massively cut down on all shootings. Mass shootings get lots of attention but let’s fact it, they are statistical anomalies compared to the very predictable country-wide individual shootings that we see every day. The overall death toll by shooting in countries is highly correlated to the gun ownership rate:

For me, that is super convincing. However, I’m pretty sure we will need a bit more than true facts to deal effectively with what has become a religion in this country. I’d love advice on strategies to this effect.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

Do you have any advice about how to tell your boss that you’re pregnant if you didn’t start the job very long before you got pregnant?

Shy pregnant woman

Dear Shy,

One of the great things about being pregnant is that it announces itself. My advice it to say nothing unless it just spontaneously feels right to do so. Just please don’t feel guilty or awkward towards your employer about being pregnant – it’s normal, natural, and protected by the law.

And please write back with questions about babies when the time comes!

Auntie Pythia

——

Finally, a question for the readers – I’m interested in what you’ll say:

Aunt Pythia,

If an editor of an Elsevier journal asks you to referee a paper, wouldn’t it be the norm to decline the request instead of leaving it unanswered, or does Gowers’s revolution includes that anyone who has not joined for one reason or another should be shunned and considered a pariah?

Trapped Editor

Please submit your questions here! I’m getting wonderful, high quality questions, but not enough of them, and I’m almost out. Please save Aunt Pythia by asking her something super ridiculous!

I wish I knew now what I’ll know then

Yesterday I read this New York Times article which explains the so-called “end of history illusion,” a fancy way of saying that as we acknowledge having changed a lot in the past, we project more of the same into the future.

I guess this is supposed to mean we always see the present moment as the end of history. From the article:

“Middle-aged people — like me — often look back on our teenage selves with some mixture of amusement and chagrin,” said one of the authors, Daniel T. Gilbert, a psychologist at Harvard. “What we never seem to realize is that our future selves will look back and think the very same thing about us. At every age we think we’re having the last laugh, and at every age we’re wrong.”

For the record I thought my teenage self was pretty awesome, and it was the moment in my life where I actually lived as best I could avoiding hypocrisy. I never laugh at my teenage self, and I’m always baffled that other people do – think of everything we had to understand and deal with all at once! But back to the end of history.

Scientists explain the phenomenon by suggesting it’s good for our egos to think we are currently perfectly evolved and won’t need to modify anything in our beliefs. Another possibility they come up with: we are too lazy to do better than this, and it’s easier to remember the past than it is to think hard about the future.

Here’s another explanation that I came up with: we have no idea what the future holds, nor whether we will become more or less conservative, more or less healthy, or more or less irritable, etc., so in expectation we will be exactly the same as we are now. Note that’s not the same as saying we actually will be the same, it’s just that we don’t know which direction we’ll move.

In other words, we are doing something different when we look into the future than when we look into the past, and the honest best guess of our future selves may well be our current selves.

After all, we don’t know what random events will occur in the future (like getting hit by a car and breaking our leg, say) that will effect us, and the best we can go is our current plans for ourselves.

Even so, it’s interesting to think about how I’ve changed over my lifetime and continue the trend into the future. If I do that, I evoke something that is clearly not an extrapolation of my current self.

In particular, I can project that I will be very different in 10 years, more patient, more joyful, doing god knows what for a living (if I’m not totally broke), even more opinionated than I am now, and much much wiser about how to raise teenage sons. Come to think of it, I can’t wait!

Planning for the robot revolution

Yesterday I read this Wired magazine article about the robot revolution by Kevin Kelly called “Better than Human”. The idea of the article is to make peace with the inevitable robot revolution, and to realize that it’s already happened and that it’s good.

I like this line:

We have preconceptions about how an intelligent robot should look and act, and these can blind us to what is already happening around us. To demand that artificial intelligence be humanlike is the same flawed logic as demanding that artificial flying be birdlike, with flapping wings. Robots will think different. To see how far artificial intelligence has penetrated our lives, we need to shed the idea that they will be humanlike.

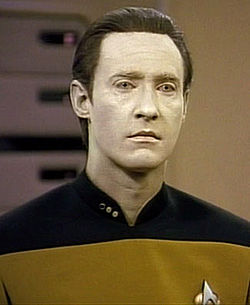

True! Let’s stop looking for a Star Trek Data-esque android (although he is very cool according to my 10-year-old during our most recent Star Trek marathon).

Instead, let’s realize that the typical artificial intelligence we can expect to experience in our lives is the web itself, inasmuch as it is a problem-solving, decision-making system, and our interactions with it through browsing and searching is both how we benefit from artificial intelligence and how it takes us over.

What I can’t accept about the Wired article, though, is the last part, where we should consider it good. But maybe it is only supposed to be good for the Wired audience and I’m asking for too much. My concerns are touched on briefly here:

When robots and automation do our most basic work, making it relatively easy for us to be fed, clothed, and sheltered, then we are free to ask, “What are humans for?”

Here’s the thing: it’s already relatively easy for us to be fed, clothed, and sheltered, but we aren’t doing it. That doesn’t seem to be our goal. So why would it suddenly become our goal because there is increasing automation? Robots won’t change our moral values, as far as I know.

Also, the article obscures economic political reality. First imagines the audience as a land- and robot-owning master:

Imagine you run a small organic farm. Your fleet of worker bots do all the weeding, pest control, and harvesting of produce, as directed by an overseer bot, embodied by a mesh of probes in the soil. One day your task might be to research which variety of heirloom tomato to plant; the next day it might be to update your custom labels. The bots perform everything else that can be measured.

Great, so the landowners will not need any workers at all. But then what about the people who don’t have a job? Oh wait, something magical happens:

Everyone will have access to a personal robot, but simply owning one will not guarantee success. Rather, success will go to those who innovate in the organization, optimization, and customization of the process of getting work done with bots and machines.

Really? Everyone will own a robot? How is that going to work? It doesn’t seem to be a natural progression from our current system. Or maybe they mean like the way people own phones now. But owning a phone doesn’t help you get work done if there’s no work for you to do.

But maybe I’m being too cynical. I’m sure there’s deep thought being put to this question. Oh here, in this part:

I ask Brooks to walk with me through a local McDonald’s and point out the jobs that his kind of robots can replace. He demurs and suggests it might be 30 years before robots will cook for us.

I guess this means we don’t have to worry at all, since 30 years is such a long, long time.

Open data and the emergence of data philanthropy

This is a guest post. Crossposted at aluation.

I’m a bit late to this conversation, but I was reminded by Cathy’s post over the weekend on open data – which most certainly is not a panacea – of my own experience a couple of years ago with a group that is trying hard to do the right thing with open data.

The UN funded a new initiative in 2009 called Global Pulse, with a mandate to explore ways of using Big Data for the rapid identification of emerging crises as well as for crafting more effective development policy in general. Their working hypothesis at its most simple is that the digital traces individuals leave in their electronic life – whether through purchases, mobile phone activity, social media or other sources – can reveal emergent patterns that can help target policy responses. The group’s website is worth a visit for anyone interested in non-commercial applications of data science – they are absolutely the good guys here, doing the kind of work that embodies the social welfare promise of Big Data.

With that said, I think some observations about their experience in developing their research projects may shed some light on one of Cathy’s two main points from her post:

- How “open” is open data when there are significant differences in both the ability to access the data, and more important, in the ability to analyze it?

- How can we build in appropriate safeguards rather than just focusing on the benefits and doing general hand-waving about the risks?

I’ll focus on Cathy’s first question here since the second gets into areas beyond my pay grade.

The Global Pulse approach to both sourcing and data analytics has been to rely heavily on partnerships with academia and the private sector. To Cathy’s point above, this is true of both closed data projects (such as those that rely on mobile phone data) as well as open data projects (those that rely on blog posts, news sites and other sources). To take one example, the group partnered with two firms in Cambridge to build a real-time indicator of bread prices in Latin America in order. The data in this case was open, while the web-scraping analytics (generally using grocery-story website prices) were developed and controlled by the vendors. As someone who is very interested in food prices, I found their work fascinating. But I also found it unsettling that the only way to make sense of this open data – to turn it into information, in other words – was through the good will of a private company.

The same pattern of open data and closed analytics characterized another project, which tracked Twitter in Indonesia for signals of social distress around food, fuel prices, health and other issues. The project used publicly available Twitter data, so it was open to that extent, though the sheer volume of data and the analytical challenges of teasing meaningful patterns out of it called for a powerful engine. As we all know, web-based consumer analytics are far ahead of the rest of the world in terms of this kind of work. And that was precisely where Global Pulse rationally turned – to a company that has generally focused on analyzing social media on behalf of advertisers.

Does this make them evil? Of course not – as I said above, Global Pulse are the good guys here. My point is not about the nature of their work but about its fragility.

The group’s Director framed their approach this way in a recent blog post:

We are asking companies to consider a new kind of CSR – call it “data philanthropy.” Join us in our efforts by making anonymized data sets available for analysis, by underwriting technology and research projects, or by funding our ongoing efforts in Pulse Labs. The same technologies, tools and analysis that power companies’ efforts to refine the products they sell, could also help make sure their customers are continuing to improve their social and economic wellbeing. We are asking governments to support our efforts because data analytics can help the United Nations become more agile in understanding the needs of and supporting the most vulnerable populations around the globe, which in terms boosts the global economy, benefiting people everywhere.

What happens when corporate donors are no longer willing to be data philanthropists? And a question for Cathy – how can we ensure that these new Data Science programs like the one at Columbia don’t end up just feeding people into consumer analytics firms, in the same way that math and econ programs ended up feeding people into Wall Street jobs?

I don’t have any answers here, and would be skeptical of anyone who claimed to. But the answers to these questions will likely define a lot of the gap between the promise of open data and whatever it ends up becoming.

Is mathbabe a terrorist or a lazy hippy? (#OWS)

The Occupy narrative, put forth by mainstream media such as the New York Times and led by friends of Wall Street such as Andrew Ross Sorkin, is sad and pathetic. A bunch of lazy hippies, with nothing much in the way of organized demands, and, by the way, nothing much in the way of reasonable grievances either. And moreover, according to Sorkin, Occupy had fizzled as of its first anniversary.

To an earnest reader of the New York Times, in other words, there’s no there there, and we can move on. Nothing to see.

From my perspective as an active occupier, this approach of casual indifference has seemed oddly inconsistent with the interest in the #OWS Alternative Banking group from other nations. I’ve been interviewed by mainstream reporters from the UK, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, and Japan, and none of them seemed as willing to dismiss the movement or our group quite as actively as the New York Times has.

And then there was the country-wide clearing of the parks, which seemed mysteriously coordinated, and the press (yes, the New York Times again) knowing when and where it would happen somehow, and taking pictures of the police gathering beforehand.

Really it was enough to make one consider a conspiracy theory between the authorities and mainstream media.

I’m not one for conspiracy theories, though, so I let it pass. But other people were more vigilant than myself after the coordinated clearings, and, as I learned from this Naked Capitalism post, first Truthout attempted a FOIA request to the FBI, and was told that “no documents related to its infiltration of Occupy Wall Street existed at all”, and then the Partnership for Civil Justice filed a FOIA request which was served.

Turns out there was quite a bit of worry about Occupy among the FBI, and Homeland Security, even before Zuccotti was occupied. Occupy was dubbed a terrorist organization, for example. See the heavily redacted details here.

I guess to some extent this makes sense, as the roots of Occupy are outwardly anarchist, and there is a history of anarchist bombings of the New York Stock Exchange. I guess this could also explain the meetings the FBI and Homeland Security had with the banks and the stock exchange. They wanted to cover their asses in case the anarchists were violent.

On the other hand, by the time they cleared the park the movement was openly peaceful. You don’t get called lazy dirty hippies because you’re throwing bombs into buildings, after all. And the coordination of the clearing of the parks is no longer a conspiracy, it’s verified. They were clearly afraid of us.

So which is it, lazy hippy or scary terrorist? There’s a baffling disconnect.

The truth, in this case, is not in between. Instead, Occupy lives in a different plane altogether, as I’ll explain, and this in turn explains both the “lazy” and the “scary” narrative.

The “lazy” can be put to rest here and now, it’s just wrong. The response and relief efforts of Occupy Sandy has convincingly shown that laziness is not an underlying principle of Occupy.

But Occupy Sandy did expose some principles that we occupiers have known to be true since the beginning:

- that we must overcome or even ignore structured and rigid rules to help one another at a human level,

- that we must connect directly with suffering and organically respond to it as we each know how to, depending on circumstances, and

- that moral and ethical responsibilities are just plain more important than rules.

Such a nuanced concept might seem, from the outside, to be a bunch of meditating hippies, although you’d have to kind of want to see that to think that’s all it is. So that explains the “lazy” narrative to me: if you don’t understand it, and if you don’t want to bother to look carefully, then just describe the surface characteristics.

Second, the “scary” part is right, but it’s not scary in the sense of guns and bombs – but since the cops, the FBI, and Homeland Security speak in that language, the actual threat of Occupy is again lost in translation.

It’s our ideas that threaten, not our violence. We ignore the rules, when they oppress and when they make no sense and when they serve to entrench an already entrenched elite. And ignoring rules is sometimes more threatening than breaking them.

Is mathbabe a terrorist? Is the Alternative Banking group a threat to national security because we discuss breaking up the big banks without worrying about pissing off major campaign contributors?

I hope we are a threat, but not to national security, and not by bombs or guns, but by making logical and moral sense and consistently challenging a rigged system.

I’m planning to file a FOIA request on myself and on the Alt Banking group to see what’s up.

I totally trust experts, actually

I lied yesterday, as a friend at my Occupy meeting pointed out to me last night.

I made it seem like I look into every model before trusting it, and of course that’s not true. I eat food grown and prepared by other people daily. I go on airplanes and buses all the time, trusting that they will work and that they will be driven safely. I still have my money in a bank, and I also hire an accountant and sign my tax forms without reading them. So I’m a hypocrite, big-time.

There’s another thing I should clear up: I’m not claiming I understand everything about climate research just because I talked to an expert for 2 or 3 hours. I am certainly not an expert, nor am I planning to become one. Even so, I did learn a lot, and the research I undertook was incredibly useful to me.

So, for example, my father is a climate change denier, and I have heard him give a list of scientific facts to argue against climate change. I asked my expert to counter-argue these points, and he did so. I also asked him to explain the underlying model at a high level, which he did.

My conclusion wasn’t that I’ve looked carefully into the model and it’s right, because that’s not possible in such a short time. My conclusion was that this guy is trustworthy and uses logical argument, which he’s happy to share with interested people, and moreover he manages to defend against deniers without being intellectually defensive. In the end, I’m trusting him, an expert.

On the other hand, if I met another person with a totally different conclusion, who also impressed me as intellectually honest and curious, then I’d definitely listen to that guy too, and I’d be willing to change my mind.

So I do imbue models and theories with a limited amount of trust depending on how much sense they makes to me. I think that’s reasonable, and it’s in line with my advocacy of scientific interpreters. Obviously not all scientific interpreters would be telling the same story, but that’s not important – in fact it’s vital that they don’t, because it is a privilege to be allowed to listen to the different sides and be engaged in the debate.

If I sat down with an expert for a whole day, like my friend Jordan suggests, to determine if they were “right” on an issue where there’s argument among experts, then I’d fail, but even understanding what they were arguing about would be worthwhile and educational.

Let me say this another way: experts argue about what they don’t agree on, of course, since it would be silly for them to talk about what they do agree on. But it’s their commonality that we, the laypeople, are missing. And that commonality is often so well understood that we could understand it rather quickly if it was willingly explained to us. That would be a huge step.

So I wasn’t lying after all, if I am allowed to define the “it” that I did get at in the two hours with an expert. When I say I understood it, I didn’t mean everything, I meant a much larger chunk of the approach and method than I’d had before, and enough to evoke (limited) trust.

Something I haven’t addressed, which I need to think about more (please help!), is the question of what subjects require active skepticism. On of my commenters, Paul Stevens, brought this up:

… For me, lay people means John Q Public – public opinion because public opinion can shape policy. In practice, this only matters for a select few issues, such as climate change or science education. There is no impact to a lay person not understanding / believing in the Higgs particle for example.

On trusting experts, climate change research, and scientific translators

Stephanie Tai has written a thoughtful response on Jordan Ellenberg’s blog to my discussion with Jordan regarding trusting experts (see my Nate Silver post and the follow-up post for more context).

Trusting experts

Stephanie asks three important questions about trusting experts, which I paraphrase here:

- What does it take to look into a model yourself? How deeply must you probe?

- How do you avoid being manipulated when you do so?

- Why should we bother since stuff is so hard and we each have a limited amount of time?

I must confess I find the first two questions really interesting and I want to think about them, but I have a very little patience with the last question.

Here’s why:

- I’ve seen too many people (individual modelers) intentionally deflect investigations into models by setting them up as so hard that it’s not worth it (or at least it seems not worth it). They use buzz words and make it seem like there’s a magical layer of their model which makes it too difficult for mere mortals. But my experience (as an arrogant, provocative, and relentless questioner) is that I can always understand a given model if I’m talking to someone who really understands it and actually wants to communicate it.

- It smacks of an excuse rather than a reason. If it’s our responsibility to understand something, then by golly we should do it, even if it’s hard.

- Too many things are left up to people whose intentions are not reasonable using this “too hard” argument, and it gives those people reason to make entire systems seem too difficult to penetrate. For a great example, see the financial system, which is consistently too complicated for regulators to properly regulate.

I’m sure I seem unbelievably cynical here, but that’s where I got by working in finance, where I saw first-hand how manipulative and manipulated mathematical modeling can become. And there’s no reason at all such machinations wouldn’t translate to the world of big data or climate modeling.

Climate research

Speaking of climate modeling: first, it annoys me that people are using my “distrust the experts” line to be cast doubt on climate modelers.

People: I’m not asking you to simply be skeptical, I’m saying you should look into the models yourself! It’s the difference between sitting on a couch and pointing at a football game on TV and complaining about a missed play and getting on the football field yourself and trying to figure out how to throw the ball. The first is entertainment but not valuable to anyone but yourself. You are only adding to the discussion if you invest actual thoughtful work into the matter.

To that end, I invited an expert climate researcher to my house and asked him to explain the climate models to me and my husband, and although I’m not particularly skeptical of climate change research (more on that below when I compare incentives of the two sides), I asked obnoxious, relentless questions about the model until I was satisfied. And now I am satisfied. I am considering writing it up as a post.

As an aside, if climate researchers are annoyed by the skepticism, I can understand that, since football fans are an obnoxious group, but they should not get annoyed by people who want to actually do the work to understand the underlying models.

Another thing about climate research. People keep talking about incentives, and yes I agree wholeheartedly that we should follow the incentives to understand where manipulation might be taking place. But when I followed the incentives with respect to climate modeling, they bring me straight to climate change deniers, not to researchers.

Do we really think these scientists working with their research grants have more at stake than multi-billion dollar international companies who are trying to ignore the effect of their polluting factories on the environment? People, please. The bulk of the incentives are definitely with the business owners. Which is not to say there are no incentives on the other side, since everyone always wants to feel like their research is meaningful, but let’s get real.

Scientific translators

I like this idea Stephanie comes up with:

Some sociologists of science suggest that translational “experts”–that is, “experts” who aren’t necessarily producing new information and research, but instead are “expert” enough to communicate stuff to those not trained in the area–can help bridge this divide without requiring everyone to become “experts” themselves. But that can also raise the question of whether these translational experts have hidden agendas in some way. Moreover, one can also raise questions of whether a partial understanding of the model might in some instances be more misleading than not looking into the model at all–examples of that could be the various challenges to evolution based on fairly minor examples that when fully contextualized seem minor but may pop out to someone who is doing a less systematic inquiry.

First, I attempt to make my blog something like a platform for this, and I also do my best to make my agenda not at all hidden so people don’t have to worry about that.

This raises a few issues for me:

- Right now we depend mostly on press to do our translations, but they aren’t typically trained as scientists. Does that make them more prone to being manipulated? I think it does.

- How do we encourage more translational expertise to emerge from actual experts? Currently, in academia, the translation to the general public of one’s research is not at all encouraged or rewarded, and outside academia even less so.

- Like Stephanie, I worry about hidden agendas and partial understandings, but I honestly think they are secondary to getting a robust system of translation started to begin with, which would hopefully in turn engage the general public with the scientific method and current scientific knowledge. In other words, the good outweighs the bad here.

Open data is not a panacea

I’ve talked a lot recently about how there’s an information war currently being waged on consumers by companies that troll the internet and collect personal data, search histories, and other “attributes” in data warehouses which then gets sold to the highest bidders.

It’s natural to want to balance out this information asymmetry somehow. One such approach is open data, defined in Wikipedia as the idea that certain data should be freely available to everyone to use and republish as they wish, without restrictions from copyright, patents or other mechanisms of control.

I’m going to need more than one blog post to think this through, but I wanted to make two points this morning.

The first is my issue with the phrase “freely available to everyone to use”. What does that mean? Having worked in futures trading, where we put trading machines and algorithms in close proximity with exchanges for large fees so we can get to the market data a few nanoseconds before anyone else, it’s clear to me that availability and access to data is an incredibly complicated issue.

And it’s not just about speed. You can have hugely important, rich, and large data sets sitting in a lump on a publicly available website like wikipedia, and if you don’t have fancy parsing tools and algorithms you’re not going to be able to make use of it.

When important data goes public, the edge goes to the most sophisticated data engineer, not the general public. The Goldman Sachs’s of the world will always know how to make use of “freely available to everyone” data before the average guy.

Which brings me to my second point about open data. It’s general wisdom that we should hope for the best but prepare for the worst. My feeling is that as we move towards open data we are doing plenty of the hoping part but not enough of the preparing part.

If there’s one thing I learned working in finance, it’s not to be naive about how information will be used. You’ve got to learn to think like an asshole to really see what to worry about. It’s a skill which I don’t regret having.

So, if you’re giving me information on where public schools need help, I’m going to imagine using that information to cut off credit for people who live nearby. If you tell me where environmental complaints are being served, I’m going to draw a map and see where they aren’t being served so I can take my questionable business practices there.

I’m not saying proponents of open data aren’t well-meaning, they often seem to be. And I’m not saying that the bad outweighs the good, because I’m not sure. But it’s something we should figure out how to measure, and in this information war it’s something we should keep a careful eye on.

Suggested New Year’s resolution: start a blog

I was thinking the other day how much I’ve gotten out of writing this blog. I’m incredibly grateful for it, and I want you to consider starting a blog too. Let’s go through the pros and cons:

Pros

- A blog forces you to articulate your thoughts rather than having vague feelings about issues.

- This means you get past things that are bothering you.

- You also get much more comfortable with writing, because you’re doing it rather than thinking about doing it.

- If your friends read your blog you get to hear what they think.

- If other people read your blog you get to hear what they think too. You learn a lot that way.

- Your previously vague feelings and half-baked ideas are not only formulated, but much better thought out than before, what with all the feedback. You’ll find yourself changing your mind or at least updating and modifying lots of opinions.

- You also get to make new friends through people who read your blog (this is my favorite part).

- Over time, instead of having random vague thoughts about things that bug you, you almost feel like you have a theory about the things that bug you (this could be a “con” if you start feeling all bent out of shape because the world is going to hell).

Cons

- People often think what you’re saying is dumb and they don’t resist telling you (you could think of this as a “pro” if you enjoy growing a thicker skin, which I do).

- Once you say something dumb, it’s there for all time, in your handwriting, and you’ve gone on record saying dumb things (that’s okay too if you don’t mind being dumb).

- It takes a pretty serious commitment to write a blog, since you have to think of things to say that might interest people (thing you should never say on a blog: “Sorry it’s been so long since I wrote a post!”).

- Even when you’re right, and you’ve articulated something well, people can always dismiss what you’ve said by claiming it can’t be important since it’s just a blog.

Advice if you’ve decided to go ahead and start a blog

- Set aside time for your blog every day. My time is usually 6-7am, before the kids wake up.

- Keep notes for yourself on bloggy subjects. I write a one-line gmail to myself with the subject “blog ideas” and in the morning I search for that phrase and I’m presented with a bunch of cool ideas.

- For example I might write something like, “Can I pay people to not wear moustaches?” and I leave a link if appropriate.

- I try to switch up the subject of the blog so I don’t get bored. This may keep my readers from getting bored but don’t get too worried about them because it’s distracting.

- My imagined audience is almost always a friend who would forgive me if I messed something up. It’s a friendly conversation.

- Often I write about something I’ve found myself explaining or complaining about a bunch of times in the past few days.

- Anonymous negative comments happen, and are often written by jerks. Try to not take them personally.

- Try to accept criticism if it’s helpful and ignore it if it’s hurtful. And don’t hesitate to delete hurtful comments. If that jerk wants a platform, he or she can start his or her own goddamn blog.

- Never feel guilty towards your blog. It’s inanimate. If you start feeling guilty then think about how to make it more playful. Take a few days off and wait until you start missing your blog, which will happen, if you’re anything like me.

Corporations don’t act like people

Corporations may be legally protected like people, but they don’t act selfishly like people do.

I’ve written about this before here, when I was excitedly reading Liquidated by Karen Ho, but recent overheard conversations have made me realize that there’s still a feeling out there that “the banks” must not have understood how flawed the models were because otherwise they would have avoided them out of a sense of self-preservation.

Important: “the banks” don’t think or do things, people inside the banks think and do things. In fact, the people inside the banks think about themselves and their own chances of getting big bonuses/ getting fired, and they don’t think about the bank’s future at all. The exception may be the very tip top brass of management, who may or may not care about the future of their institutions just as a legacy reputation issue. But in any case their nascent reputation fears, if they existed at all, did not seem to overwhelm their near-term desire for lots of money.

Example: I saw Robert Rubin on stage well before the major problems at Citi in a discussion about how badly the mortgage-backed securities market was apt to perform in the very near future. He did not seem to be too stupid to understand what the conversation was about, but that didn’t stop him from ignoring the problem at Citigroup whilst taking in $126 million dollars. The U.S. government, in the meantime, bailed out Citigroup to the tune of $45 billion with another guarantee of $300 billion.

Here’s a Bloomberg BusinessWeek article excerpt about how he saw his role:

Rubin has said that Citigroup’s losses were the result of a financial force majeure. “I don’t feel responsible, in light of the facts as I knew them in my role,” he told the New York Times in April 2008. “Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.”

In March 2010, Rubin elaborated in testimony before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. “In the world of trading, the world I have lived in my whole adult life, there is always a very important distinction between what you could have reasonably known in light of the facts at the time and what you know with the benefit of hindsight,” he said. Pressed by FCIC Executive Director Thomas Greene about warnings he had received regarding the risk in Citigroup’s mortgage portfolio, Rubin was opaque: “There is always a tendency to overstate—or over-extrapolate—what you should have extrapolated from or inferred from various events that have yielded warnings.”

Bottomline: there’s no such thing as a bank’s desire for self-preservation. Let’s stop thinking about things that way.

Consumer segmentation taken to the extreme

I’m up in Western Massachusetts with the family, hidden off in a hotel with a pool and a nearby yarn superstore. My blogging may be spotty for the next few days but rest assured I haven’t forgotten about mathbabe (or Aunt Pythia).

I have just enough time this morning to pose a thought experiment. It’s in three steps. First, read this Reuters article which ends with:

Imagine if Starbucks knew my order as I was pulling into the parking lot, and it was ready the second I walked in. Or better yet, if a barista could automatically run it out to my car the exact second I pulled up. I may not pay more for that everyday, but I sure as hell would if I were late to a meeting with a screaming baby in the car. A lot more. Imagine if my neighborhood restaurants knew my local, big-tipping self was the one who wanted a reservation at 8 pm, not just an anonymous user on OpenTable. They might find some room. And odds are, I’d tip much bigger to make sure I got the preferential treatment the next time. This is why Uber’s surge pricing is genius when it’s not gouging victims of a natural disaster. There are select times when I’ll pay double for a cab. Simply allowing me to do so makes everyone happy.

In a world where the computer knows where we are and who we are and can seamlessly charge us, the world might get more expensive. But it could also get a whole lot less annoying. ”This is what big data means to me,” Rosensweig says.

Second, think about just how not “everyone” is happy. It’s a pet peeve of mine that people who like their personal business plan consistently insist that everybody wins, when clearly there are often people (usually invisible) who are definitely losing. In this case the losers are people whose online personas don’t correlate (in a given model) with big tips. Should those people not be able to reserve a table at a restaurant now? How is that model going to work?

And now I’ve gotten into the third step. It used to be true that if you went to a restaurant enough, the chef and the waitstaff would get to know you and might even keep a table open for you. It was old-school personalization.

What if that really did start to happen at every restaurant and store automatically, based on your online persona? On the one hand, how weird would that be, and on the other hand how quickly would we all get used to it? And what would that mean for understanding each other’s perspectives?

Whom can you trust?

My friend Jordan has written a response to yesterday’s post about Nate Silver. He is a major fan of Silver and contends that I’m not fair to him:

I think Cathy’s distrust is warranted, but I think Silver shares it. The central concern of his chapter on weather prediction is the vast difference in accuracy between federal hurricane forecasters, whose only job is to get the hurricane track right, and TV meteorologists, whose very different incentive structure leads them to get the weather wrong on purpose. He’s just as hard on political pundits and their terrible, terrible predictions, which are designed to be interesting, not correct.

To this I’d say, Silver mocks TV meteorologists and political pundits in a dismissive way, as not being scientific enough. That’s not the same as taking them seriously and understanding their incentives, and it doesn’t translate to the much more complicated world of finance.

In any case, he could have understood incentives in every field except finance and I’d still be mad, because my direct experience with finance made me understand it, and the outsized effect it has on our economy makes it hugely important.

But Jordan brings up an important question about trust:

But what do you do with cases like finance, where the only people with deep domain knowledge are the ones whose incentive structure is socially suboptimal? (Cathy would use saltier language here.) I guess you have to count on mavericks like Cathy, who’ve developed the domain knowledge by working in the financial industry, but who are now separated from the incentives that bind the insiders.

But why do I trust what Cathy says about finance?

Because she’s an expert.

Is Cathy OK with this?

No, Cathy isn’t okay with this. The trust problem is huge, and I address it directly in my post:

This raises a larger question: how can the public possibly sort through all the noise that celebrity-minded data people like Nate Silver hand to them on a silver platter? Whose job is it to push back against rubbish disguised as authoritative scientific theory?

It’s not a new question, since PR men disguising themselves as scientists have been around for decades. But I’d argue it’s a question that is increasingly urgent considering how much of our lives are becoming modeled. It would be great if substantive data scientists had a way of getting together to defend the subject against sensationalist celebrity-fueled noise.

One hope I nurture is that, with the opening of the various data science institutes such as the one at Columbia which was a announced a few months ago, there will be a way to form exactly such a committee. Can we get a little peer review here, people?

I do think domain-expertise-based peer review will help, but not when the entire field is captured, like in some subfields of medical research and in some subfields of economics and finance (for a great example see Glen Hubbard get destroyed in Matt Taibbi’s recent blogpost for selling his economic research).

The truth is, some fields are so yucky that people who want to do serious research just leave because they are disgusted. Then the people who remain are the “experts”, and you can’t trust them.

The toughest part is that you don’t know which fields are like this until you try to work inside them.

Bottomline: I’m telling you not to trust Nate Silver, and I would also urge you not to trust any one person, including me. For that matter don’t necessarily trust crowds of people either. Instead, carry a healthy dose of skepticism and ask hard questions.

This is asking a lot, and will get harder as time goes on and as the world becomes more complicated. On the one hand, we need increased transparency for scientific claims like projects such as runmycode provide. On the other, we need to understand the incentive structure inside a field like finance to make sure it is aligned with its stated mission.

Nate Silver confuses cause and effect, ends up defending corruption

Crossposted on Naked Capitalism

I just finished reading Nate Silver’s newish book, The Signal and the Noise: Why so many predictions fail – but some don’t.

The good news

First off, let me say this: I’m very happy that people are reading a book on modeling in such huge numbers – it’s currently eighth on the New York Times best seller list and it’s been on the list for nine weeks. This means people are starting to really care about modeling, both how it can help us remove biases to clarify reality and how it can institutionalize those same biases and go bad.

As a modeler myself, I am extremely concerned about how models affect the public, so the book’s success is wonderful news. The first step to get people to think critically about something is to get them to think about it at all.

Moreover, the book serves as a soft introduction to some of the issues surrounding modeling. Silver has a knack for explaining things in plain English. While he only goes so far, this is reasonable considering his audience. And he doesn’t dumb the math down.

In particular, Silver does a nice job of explaining Bayes’ Theorem. (If you don’t know what Bayes’ Theorem is, just focus on how Silver uses it in his version of Bayesian modeling: namely, as a way of adjusting your estimate of the probability of an event as you collect more information. You might think infidelity is rare, for example, but after a quick poll of your friends and a quick Google search you might have collected enough information to reexamine and revise your estimates.)

The bad news

Having said all that, I have major problems with this book and what it claims to explain. In fact, I’m angry.

It would be reasonable for Silver to tell us about his baseball models, which he does. It would be reasonable for him to tell us about political polling and how he uses weights on different polls to combine them to get a better overall poll. He does this as well. He also interviews a bunch of people who model in other fields, like meteorology and earthquake prediction, which is fine, albeit superficial.

What is not reasonable, however, is for Silver to claim to understand how the financial crisis was a result of a few inaccurate models, and how medical research need only switch from being frequentist to being Bayesian to become more accurate.

Let me give you some concrete examples from his book.

Easy first example: credit rating agencies

The ratings agencies, which famously put AAA ratings on terrible loans, and spoke among themselves as being willing to rate things that were structured by cows, did not accidentally have bad underlying models. The bankers packaging and selling these deals, which amongst themselves they called sacks of shit, did not blithely believe in their safety because of those ratings.

Rather, the entire industry crucially depended on the false models. Indeed they changed the data to conform with the models, which is to say it was an intentional combination of using flawed models and using irrelevant historical data (see points 64-69 here for more (Update: that link is now behind the paywall)).

In baseball, a team can’t create bad or misleading data to game the models of other teams in order to get an edge. But in the financial markets, parties to a model can and do.

In fact, every failed model is actually a success

Silver gives four examples what he considers to be failed models at the end of his first chapter, all related to economics and finance. But each example is actually a success (for the insiders) if you look at a slightly larger picture and understand the incentives inside the system. Here are the models:

- The housing bubble.

- The credit rating agencies selling AAA ratings on mortgage securities.

- The financial melt-down caused by high leverage in the banking sector.

- The economists’ predictions after the financial crisis of a fast recovery.

Here’s how each of these models worked out rather well for those inside the system:

- Everyone involved in the mortgage industry made a killing. Who’s going to stop the music and tell people to worry about home values? Homeowners and taxpayers made money (on paper at least) in the short term but lost in the long term, but the bankers took home bonuses that they still have.

- As we discussed, this was a system-wide tool for building a money machine.

- The financial melt-down was incidental, but the leverage was intentional. It bumped up the risk and thus, in good times, the bonuses. This is a great example of the modeling feedback loop: nobody cares about the wider consequences if they’re getting bonuses in the meantime.

- Economists are only putatively trying to predict the recovery. Actually they’re trying to affect the recovery. They get paid the big bucks, and they are granted authority and power in part to give consumers confidence, which they presumably hope will lead to a robust economy.

Cause and effect get confused

Silver confuses cause and effect. We didn’t have a financial crisis because of a bad model or a few bad models. We had bad models because of a corrupt and criminally fraudulent financial system.

That’s an important distinction, because we could fix a few bad models with a few good mathematicians, but we can’t fix the entire system so easily. There’s no math band-aid that will cure these boo-boos.

I can’t emphasize this too strongly: this is not just wrong, it’s maliciously wrong. If people believe in the math band-aid, then we won’t fix the problems in the system that so desperately need fixing.

Why does he make this mistake?

Silver has an unswerving assumption, which he repeats several times, that the only goal of a modeler is to produce an accurate model. (Actually, he made an exception for stock analysts.)

This assumption generally holds in his experience: poker, baseball, and polling are all arenas in which one’s incentive is to be as accurate as possible. But he falls prey to some of the very mistakes he warns about in his book, namely over-confidence and over-generalization. He assumes that, since he’s an expert in those arenas, he can generalize to the field of finance, where he is not an expert.

The logical result of this assumption is his definition of failure as something where the underlying mathematical model is inaccurate. But that’s not how most people would define failure, and it is dangerously naive.

Medical Research

Silver discusses both in the Introduction and in Chapter 8 to John Ioannadis’s work which reveals that most medical research is wrong. Silver explains his point of view in the following way:

I’m glad he mentions incentives here, but again he confuses cause and effect.

As I learned when I attended David Madigan’s lecture on Merck’s representation of Vioxx research to the FDA as well as his recent research on the methods in epidemiology research, the flaws in these medical models will be hard to combat, because they advance the interests of the insiders: competition among academic researchers to publish and get tenure is fierce, and there are enormous financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies.

Everyone in this system benefits from methods that allow one to claim statistically significant results, whether or not that’s valid science, and even though there are lives on the line.

In other words, it’s not that there are bad statistical approaches which lead to vastly over-reported statistically significant results and published papers (which could just as easily happen if the researchers were employing Bayesian techniques, by the way). It’s that there’s massive incentive to claim statistically significant findings, and not much push-back when that’s done erroneously, so the field never self-examines and improves their methodology. The bad models are a consequence of misaligned incentives.

I’m not accusing people in these fields of intentionally putting people’s lives on the line for the sake of their publication records. Most of the people in the field are honestly trying their best. But their intentions are kind of irrelevant.

Silver ignores politics and loves experts

Silver chooses to focus on individuals working in a tight competition and their motives and individual biases, which he understands and explains well. For him, modeling is a man versus wild type thing, working with your wits in a finite universe to win the chess game.

He spends very little time on the question of how people act inside larger systems, where a given modeler might be more interested in keeping their job or getting a big bonus than in making their model as accurate as possible.

In other words, Silver crafts an argument which ignores politics. This is Silver’s blind spot: in the real world politics often trump accuracy, and accurate mathematical models don’t matter as much as he hopes they would.

As an example of politics getting in the way, let’s go back to the culture of the credit rating agency Moody’s. William Harrington, an ex-Moody’s analyst, describes the politics of his work as follows:

In 2004 you could still talk back and stop a deal. That was gone by 2006. It became: work your tail off, and at some point management would say, ‘Time’s up, let’s convene in a committee and we’ll all vote “yes”‘.

To be fair, there have been moments in his past when Silver delves into politics directly, like this post from the beginning of Obama’s first administration, where he starts with this (emphasis mine):

To suggest that Obama or Geithner are tools of Wall Street and are looking out for something other than the country’s best interest is freaking asinine.

and he ends with:

This is neither the time nor the place for mass movements — this is the time for expert opinion. Once the experts (and I’m not one of them) have reached some kind of a consensus about what the best course of action is (and they haven’t yet), then figure out who is impeding that action for political or other disingenuous reasons and tackle them — do whatever you can to remove them from the playing field. But we’re not at that stage yet.

My conclusion: Nate Silver is a man who deeply believes in experts, even when the evidence is not good that they have aligned incentives with the public.

Distrust the experts

Call me “asinine,” but I have less faith in the experts than Nate Silver: I don’t want to trust the very people who got us into this mess, while benefitting from it, to also be in charge of cleaning it up. And, being part of the Occupy movement, I obviously think that this is the time for mass movements.

From my experience working first in finance at the hedge fund D.E. Shaw during the credit crisis and afterwards at the risk firm Riskmetrics, and my subsequent experience working in the internet advertising space (a wild west of unregulated personal information warehousing and sales) my conclusion is simple: Distrust the experts.

Why? Because you don’t know their incentives, and they can make the models (including Bayesian models) say whatever is politically useful to them. This is a manipulation of the public’s trust of mathematics, but it is the norm rather than the exception. And modelers rarely if ever consider the feedback loop and the ramifications of their predatory models on our culture.

Why do people like Nate Silver so much?

To be crystal clear: my big complaint about Silver is naivete, and to a lesser extent, authority-worship.

I’m not criticizing Silver for not understanding the financial system. Indeed one of the most crucial problems with the current system is its complexity, and as I’ve said before, most people inside finance don’t really understand it. But at the very least he should know that he is not an authority and should not act like one.

I’m also not accusing him of knowingly helping cover up the financial industry. But covering for the financial industry is an unfortunate side-effect of his naivete and presumed authority, and a very unwelcome source of noise at this moment when so much needs to be done.

I’m writing a book myself on modeling. When I began reading Silver’s book I was a bit worried that he’d already said everything I’d wanted to say. Instead, I feel like he’s written a book which has the potential to dangerously mislead people – if it hasn’t already – because of its lack of consideration of the surrounding political landscape.

Silver has gone to great lengths to make his message simple, and positive, and to make people feel smart and smug, especially Obama’s supporters.

He gets well-paid for his political consulting work and speaker appearances at hedge funds like D.E. Shaw and Jane Street, and, in order to maintain this income, it’s critical that he perfects a patina of modeling genius combined with an easily digested message for his financial and political clients.

Silver is selling a story we all want to hear, and a story we all want to be true. Unfortunately for us and for the world, it’s not.

How to push back against the celebrity-ization of data science

The truth is somewhat harder to understand, a lot less palatable, and much more important than Silver’s gloss. But when independent people like myself step up to denounce a given statement or theory, it’s not clear to the public who is the expert and who isn’t. From this vantage point, the happier, shorter message will win every time.

This raises a larger question: how can the public possibly sort through all the noise that celebrity-minded data people like Nate Silver hand to them on a silver platter? Whose job is it to push back against rubbish disguised as authoritative scientific theory?

It’s not a new question, since PR men disguising themselves as scientists have been around for decades. But I’d argue it’s a question that is increasingly urgent considering how much of our lives are becoming modeled. It would be great if substantive data scientists had a way of getting together to defend the subject against sensationalist celebrity-fueled noise.

One hope I nurture is that, with the opening of the various data science institutes such as the one at Columbia which was a announced a few months ago, there will be a way to form exactly such a committee. Can we get a little peer review here, people?

Conclusion

There’s an easy test here to determine whether to be worried. If you see someone using a model to make predictions that directly benefit them or lose them money – like a day trader, or a chess player, or someone who literally places a bet on an outcome (unless they place another hidden bet on the opposite outcome) – then you can be sure they are optimizing their model for accuracy as best they can. And in this case Silver’s advice on how to avoid one’s own biases are excellent and useful.

But if you are witnessing someone creating a model which predicts outcomes that are irrelevant to their immediate bottom-line, then you might want to look into the model yourself.

Empathy, murder, and the NRA

I’ve been having lots of dinnertime discussions with my kids about the following three news stories:

- the guy who was pushed into the subway and nobody helped him

- the Sandy Hook murders

- the Syrian uprising

When my son asked why people care so much about the kids murdered in Connecticut but not nearly as much in a random day when as many rebels are murdered by their government in Syria, I talk about how for whatever reason people have more empathy for individuals closer to them, and Connecticut is closer than Syria. It doesn’t feel good but it kind of makes sense.

But of course this doesn’t apply to the guy who was pushed off the subway.

And, speaking of the subway incident, let me be the person who stands up and says that yes, if I’d been there I would have tried to help that man get out of the subway tracks. There were 22 seconds to help him after the crazy guy fled.

For me the ethical obligations are obvious and the empathy I feel for strangers in danger is visceral. I’ve been in situations not entirely unlike this in the subway, and I saw firsthand how other people ran away and start talking about themselves rather than trying to help someone suffering, and it amazes and disgusts me.

It makes me wonder how we develop what I’ll term “working empathy”, to distinguish between someone who actually tries to help in real time and in a meaningful way when someone else is in pain versus someone who is gawking at arm’s length.

This New York Times article touches on it but doesn’t go very deep; it basically suggests we model it for children and talk about how other people feel. It also talks about how monetary rewards stifle empathy (which I knew already from working in finance).

I’m not wondering this abstractly or philosophically. I’m wondering it because if I had a good theory about creating and spreading working empathy, I’d try to join the NRA and apply the technique to see if it works on tough cases. As in, they actually try to prevent unreasonable guns in unreasonable places, not that they issue press releases.

If Barofsky heads the SEC I’ll work for it

Neil Barofsky visited my Occupy group, Alternative Banking, this past Sunday. He was awesome.

We discussed the credit crisis, the recent outrageous HSBC ruling which quantified the cost banks near for money laundering for terrorists and drug lords at below cost, and the hopelessness, or on a good day the hope, of having a financial and regulatory system that will eventually work.

We discussed the incentives in the HAMP set-up, which explain why very few homeowners have actually received lasting relief from unaffordable mortgages. We discussed the incentives for fraud and other criminal behavior in the absence of real punishment, that too much money is being spent pursuing insider training because that’s what people understand how to do, and we discussed the reluctance of the regulators to litigate tough cases. We talked about how change has to come from the top, because all of these organizations are super hierarchical and require political will to get things done.

In the past year I was offered a job at the SEC, working as a quant in the enforcement division. Although I want to help sort out this mess, I haven’t felt that this job, which is relatively junior, would allow me to do that meaningfully.

But I came away from the meeting with Barofsky with this feeling: if we had someone in charge at the SEC like him who could speak truth to power and who is smart enough to see through economic jargon and bullshit well enough to understand incentives for fraud and lying, then I’d work there in a heartbeat.

Let’s just hope it doesn’t take another world-wide financial crisis before we get someone like that.

Making math beautiful with XyJax

My husband A. Johan de Jong has an open source algebraic geometry project called the stacks project. It’s hosted at Columbia, just like his blog which is aptly named the stacks project blog.

The stacks project is awesome: it explains the theory of stacks thoroughly, assuming only that you have a basic knowledge of algebra and a shitload of time to read. It’s about three thousand update: it’s exactly 3,452 pages, give or take, and it has a bunch of contributors besides Johan. I’m on the list most likely because of the fact that I helped him develop the tag system which allows permanent references to theorems and lemmas even within an evolving latex manuscript.

He even has pictures of tags, and hands out t-shirts with pictures of tags when people find mistakes in the stacks project.

Speaking of latex, that’s what I wanted to mention today.

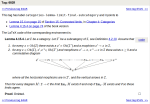

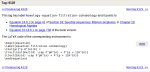

Recently a guy named Pieter Belmans has been helping Johan out with development for the site: spiffing it up and making it look more professional. The most recent thing he did was to render the latex into human readable form using XyJax package, which is an “almost xy-pic compatible package for MathJax“. I think they are understating the case; it looks great to me:

- Before

- After

- Before

- After

Silicon Valley: VC versus startup culture

This is a guest post by David Carlton, who first met Cathy at the Hampshire College Summer Studies in Mathematics when they were high school students. He was trained as a mathematician, but left academia in 2003 and has been working as a programmer and manager in the San Francisco Bay Area since then. This is crossposted from his blog malvasia bianca.

One thing I’ve been wondering recently: to what extent do I like the influence of Silicon Valley venture capital firms on the local startup culture?

There are certain ways in which their influence is good, no question: it’s great that there’s money available for people to try new things, it’s great that it means that there are exciting small companies around, and I’m fairly sure that VCs have valuable specialized knowledge that I don’t have and could benefit from. So that’s all to the good.

However, it is not the case that VCs’ interests and my interests are aligned.

Don’t get me wrong: if I’m working at a VC-funded company, then those VCs and I both want the company to succeed, and that’s great. But beyond that, our interests diverge significantly.

Their goal is to make money in a five-yearish horizon through a portfolio approach, starting from a significant pool of cash. The portfolio is a particularly important factor here: no matter what, most startups are going to fail; so, rather than try to get as many as possible to be a moderate success, it’s a perfectly reasonable thing to do to do what you can to get a few companies in your portfolio to be a major success.

And, while I’d be perfectly happy to be working at a company that’s a major success, it’s much less clear to me that I want to do that at the cost of reducing the chances that the company is a moderate success. Because while the company crashing and burning is potentially a problem at a financial level, it’s also potentially much more of a problem at a personal level.

For example, I believe in the concept of a “sustainable pace”, that on average, for most people, working too hard eventually produces less output. But if the unsustainable pace on average masks nine disasters and one remarkable success, then that may be just fine for a portfolio approach, despite what it does to the people who go through the nine disasters. (This is probably where some of the VC-funded startup youth fetishism comes in, too.)

Time horizons also play into that issue, as well: if you can keep up an unsustainable pace long enough to look good at a payoff threshold, then that could be good enough. (Possibly burning out many people along the way while hiring enough new faces to replace them and keep the company looking healthy from the outside.)

I think I saw a version of this at Playdom: the company spent the year before it got bought going on a hiring spree, buying companies that, even at the time, seemed like they made no sense. (Don’t get me wrong, some of the purchase made a lot of sense, but there were certainly many specific purchases that I raised my eyebrows at.) As far as I can tell, this was a ploy to make Playdom look good to potential purchasers by increasing our headcount, our number of games and players, and our geographic reach; but we shut down a bunch of those games soon after Disney bought us, and I didn’t see anything concrete come out of many of those studios.

The amount of money VCs are investing also plays into this. Even when funding small companies, they don’t want those companies to stay small: they want those companies to grow and grow, to justify larger and larger investments and still larger payouts.

So, if you want to work at a company that is small and focused, VC funded companies probably aren’t the best place to go (though there are exceptions: if your small and focused company is producing something that appeals to tens or hundreds of millions of people, then you can be the next Instagram).

That’s how VCs are looking for aspects of companies that I’m not; but I’m also looking for aspects of companies that VCs don’t have as strong a reason to be attracted to.

I’m always trying to learn something, and typically have specific goals along those lines that I’m looking for at companies; VCs have no reason to care about my personal development.

More broadly, I’ve been participating in industry discussions about how to develop software, and trying to figure out which of those ideas seem to work well for me; I’m sure noises about some of that filters up to the VC level, but I’m also sure that most VCs don’t have any real idea what the word ‘agile’ means. Not that they should; this is a difference, not a judgment.

I also want to work at a company that I feel is doing the right thing: e.g. on a basic level it should treat people of different genders, ethnicities, ages, class backgrounds, sexualities, relationship status, etc. fairly.

Silicon Valley actually strikes me as astonishingly open to different nationalities (most of the founders of most of the companies that I’ve worked at haven’t been American, along with a noticeable fraction of the employees); on many of the other dimensions, though, Silicon Valley isn’t nearly as open.

Here’s a nice takedown of some of the bullshit around the idea of a “meritocracy”, and VC firms themselves apparently don’t do so well themselves in this regard. I hear rumors about VC “pattern matching”; if this means that VCs are happy to insert ignorant sexist assholes into the management ranks of their portfolio companies because those execs fit some sort of pattern that the VCs have seen, that is not good.