Archive

Housing bubble or predictable consequence of income inequality?

It’s Sunday, which for me is a day of whimsical smoke-blowing. To mark the day, I think I’ll assume a position about something I know very little about, namely real estate. Feel free to educate me if I’m saying something inaccurate!

There has been a flurry of recent articles warning us that we might be entering a new housing bubble, for example this Bloomberg article. But if you look closely, the examples they describe seem cherry picked:

An open house for a five-bedroom brownstone in Brooklyn, New York, priced at $949,000 drew 300 visitors and brought in 50 offers. Three thousand miles away in Menlo Park, California, a one-story home listed for $2 million got six offers last month, including four from builders planning to tear it down to construct a bigger house. In south Florida, ground zero for the last building boom and bust, 3,300 new condominium units are under way, the most since 2007.

They mention later that Boston hasn’t risen so high as the others hot cities recently, but if you compare Boston to, say, Detroit on this useful Case-Schiller city graph, you’ll note that Boston never really went that far down in the first place.

When I read this kind of article, I can’t help but wonder how much of the signal they are seeing is explained by income inequality, combined with the increasing segregation of rich people in certain cities. New York City and Menlo Park are great examples of places where super rich people live, or want to live, and it’s well known that those buyers have totally recovered from the recession (see for example this article).

And it’s not even just American rich people investing in these cities. Judging from articles like this one in the New York Times, we’re now building luxury sky-scrapers just to attract rich Russians. The fatness of this real estate tail is extraordinary, and it makes me think that when we talk about real estate recoveries we should have different metrics than simply “average sell price”. We need to adjust our metrics to reflect the nature of the bifurcated market.

Now it’s also true that other cities, like Phoenix and Las Vegas are also gaining in the market. Many of the houses in these unsexier areas are being gobbled up by private equity firms investing in rental property. This is a huge part of the market right now in those places, and they buy whole swaths of houses at once. Note we’re not hearing about open houses with 300 buyers there.

Besides considering the scary consequences of a bunch of enormous profit-seeking management companies controlling our nation’s housing, and changing the terms of the rental agreements, I’ll just point out that these guys probably aren’t going to build too large a bubble, since their end-feeder is the renter, the average person who has a very limited income and ability to pay, unlike the Russians. On the other hand, they probably don’t know what they’re doing, so my error bars are large.

I’m not saying we don’t have a bubble, because I’d have to do a bunch of reckoning with actual numbers to understand stuff more. I’m just saying articles like the Bloomberg one don’t convince me of anything besides the fact that very rich people all want to live in the same place.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: not at all about sex

Aunt Pythia is yet again gratified to find a few new questions in her inbox this morning. Sad to say, today’s column really has nothing to do with sex, but I hope you’ll enjoy it anyway. And don’t forget:

——

Aunt Pythia,

I’m an academic in a pickle. How do I deal with papers that are years old, that I’m sick of, but that I need to get off my slate and how do I prevent this from happening again? I always want to do the work for the first 75% of the paper and then I get bored. But then I’m left with a pile of papers which, with a biiiit more work, they could be done.

Not Yet Tenured

Dear NYT,

One thing they never teach you in grad school is how to manage projects, mostly because you only have one project in grad school, which is to learn everything the first two years then do something magical and new the second two years. Even though that plan isn’t what ends up happening, it’s always in the back of your mind. In particular you only really need to focus on one thing, your thesis.

But when you get out into the real world, things change. You have options, and these option make a difference to your career and your happiness (actually your thesis work makes a difference to those things too but again, in grad school you don’t have many options).

You need a process, my friend! You need a way of managing your options. Think about this from the end backwards: after you’re done you want a prioritized list of your projects, which is a way more positive way to deal with things than letting them make you feel guilty or thinking about which ones you can drop without deeper analysis.

Here’s my suggestion, which I’ve done and it honestly helps. Namely, start a spreadsheet of your projects, with a bunch of tailored-to-you columns. Note to non-academics: this works equally well with non-academic projects.

So the first column will be the name of the project, then the year you started it, and then maybe the amount of work til completion, and then maybe the probability of success, and then how much you will like it when it’s done, and then how good it will be for your career, and then how good it will be for other non-career reasons. You can add other columns that are pertinent to your decision. Be sure to include a column that measures how much you actually feel like working on it, which is distinct from how much you’ll like it when it’s done.

All your columns entries should be numbers so we can later make weighted averages. And they should all go up when they get “better”, except time til completion, which goes down when it gets better. And if you have a way to measure one project, be sure to measure all the projects by that metric, even if they mostly score a neutral. So if one project is good for the environment, every project gets an “environment” score.

Next, decide which columns need the most attention – prioritize or weight the attributes instead of the projects for now. This probably means you put lots of weight on the “time til completion” combined with “value towards tenure” for now, especially if you’re running out of time for tenure. How you do this will depend on what resources you have in abundance and what you’re running low on. You might have tenure, and time, and you might be sick of only doing things that are good for your career but that don’t save the environment, in which case your weights on the columns will be totally different.

Finally, take some kind of weighted average of each project’s non-time attributes to get that project’s abstract attractiveness score, and then do something like divide that score by the amount of time til completion or the square root of the time to completion to get an overall “I should really do this” score. If you have two really attractive projects, each scoring 8 on the abstract attractiveness score, and one of them will take 2 weeks to do and the other 4 weeks, then the 2-week guy gets an “I should really do this” of 4, which wins over the other project with an “I should really do this” score of 2.

Actually you probably don’t have to do the math perfectly, or even explicitly. The point is you develop in your head ways by which to measure your own desire to do your projects, as well as how important those projects are to you in external ways. By the end of your exercise you’ll know a bunch more about your projects. You also might do this and disagree with the results. That usually means there’s an attribute you ignored, which you should now add. It’s probably the “how much I feel like doing this” column.

You might not have a perfect system, but you’ll be able to triage into “put onto my calendar now”, “hope to get to”, and “I’ll never finish this, and now I know why”.

Final step: put some stuff onto your calendar in the first category, along with a note to yourself to redo the analysis in a month or two when new projects have come along and you’ve gotten some of this stuff knocked off.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a freshly minted data scientist working in the banking industry. My company doesn’t seem they know what to do with me. Although they are a ginormous company, I am currently their sole “official” data scientist. They are just now developing their ability to work with Big Data, and are far from the capability to work with unstructured, nontraditional data sources. There are, apparently, grand (but vague) plans in the future for me and a future DS team. So far, however, they’ve put me in a predictive analytics group. and have me developing fairly mundane marketing models. They are excited about faster, in-database processes and working with larger (but still structured) data sets, but their philosophy seems to still be very traditional. They want more of the same, but faster. It doesn’t seem like they have a good idea of what data science can bring to the table. And with few resources, fellow data scientists, or much experience in the field (I came from academia), I’m having a hard time distinguishing myself and my work from what their analytics group has been doing for years. How can I make this distinction? And with few resources, what general things can I be doing now to shape the future of data science at my company?

Thanks,

Newly Entrenched With Bankers

Dear NEWB,

First, I appreciate your fake name.

Second, there’s no way you can do your job right now short of becoming a data engineer yourself and starting to hit the unstructured data with mapreduce jobs. That would be hardcore, by the way.

Third, my guess is they hired you either so they could say they had a data scientist, so pure marketing spin, which is 90% likely, or because they really plan on getting a whole team to do data science right, which I put at 1%. The remaining 9% is that they had no idea why they hired you, someone just told them to do it or something.

My advice is to put together a document for them explaining the resources you’d need to actually do something beyond the standard analytics team. Be sure to explain what and why you need those things, including other team members. Be sure and include some promises of what you’d be able to accomplish if you had those things.

Then, before handing over that document, decide whether to deliver it with a threat that you’ll leave the job unless they give you the resources in a reasonable amount of time or not. Chances are you’d have to leave, because chances are they don’t do it.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your question to Aunt Pythia!

Dow at an all-time high, who cares?

The Dow is at an all-time high. Here’s the past 12 months:

Once upon a time it might have meant something good, in a kind of “rising tide lifts all boats” sort of way. Nowadays not so much.

Of course, if you have a 401K you’ll probably be a bit happier than you were 4 years ago. Or if you’re an investor with money in the game.

On the other hand, not many people have 401K plans, and not many who do don’t have a lot of money in them, partly because one in four people have needed to dip into their savings lately in spite of the huge fees they were slapped with for doing so. Go watch the recent Frontline episode about 401Ks to learn more about this scammy industry.

Let’s face it, the Dow is so high not because the economy is great, or even because it is projected to be great soon. It’s mostly inflated out of a combination of easy Fed money for banks, which translates to easy money for people who are already rich, and the fact that world-wide investors are afraid of Europe and are parking their money in the U.S. until the Euro problem gets solved.

In other words, that money is going to go away if people decide Europe looks stable, or if the Fed decides to raise interest rates. The latter might happen when the economy (or rather, if the economy) looks better, so putting that together we’re talking about a possible negative stock market response to a positive economic outlook.

The stock market has officially become decoupled from our nation’s future.

Star Trek is my religion

I was surprised and somewhat disappointed yesterday when I found this article about Star Trek in Slate, written by Matt Yglesias. He, like me, has recently been binging on Star Trek and has decided to explain “why Star Trek is great” – also my long-term plan. He stole my idea!

My disappointment turned to amazement and glee, however, when I realized that the episode he began his column with was the exact episode I’d just finished watching about 5 minutes before I’d found his article. What are the chances??

It must be fate. Me and Matt are forever linked, even if he doesn’t care (I’m pretty sure he cares though, Trekkies are bonded like that). Plus, I figured, now that he’s written a Star Trek post, I’ll do so as well and we can act like it’s totally normal. Where’s your Star Trek post?

Here’s his opening paragraph:

In the second episode of the seventh season of the fourth Star Trek television series, Icheb, an alien teenage civilian who’s been living aboard a Federation vessel for several months after having been rescued from both the Borg and abusive parents, issues a plaintive cry: “Isn’t that what people on this ship do? They help each other?”

That’s the thing about Star Trek. It’s utopian. There’s no money, partly because they have ways to make food and objects materialize on a whim. There’s no financial system of any kind that I’ve noticed, although there’s plenty of barter, mostly dealing in natural resources. And the crucial resource that characters are constantly seeking, that somehow make the ships fly through space, are called dilithium crystals. They’re rare but they also seem to be lying around on uninhabited planets, at least for now.

But it’s not my religion just because they’ve somehow evolved past too-big-to-fail banks. It’s that they have ethics, and those ethics are collaborative, and moreover are more basic and more important than the power of technology: the moral decisions that they are confronted with and that they make are, in fact, what Star Trek is about.

Each episode can be seen as a story from a nerd bible. Can machines have a soul? Do we care less about those souls than human (or Vulcan) souls? If we come across a civilization that seems to vitally need our wisdom or technology, when do we share it? And what are the consequences for them when we do or don’t?

In Star Trek, technology is not an unalloyed good: it’s morally neutral, and it could do evil or good, depending on the context. Or rather, people could do evil or good with it. This responsibility is not lost in some obfuscated surreality.

My sons and I have a game we play when we watch Star Trek, which we do pretty much any night we can, after all the homework is done and before bed-time. It’s kind of a “spot that issue” riddle, where we decide which progressive message is being sent to us through the lens of an alien civilization’s struggles and interactions with Captain Picard or Janeway.

Gay marriage!

Confronting sexism!

Overcoming our natural tendencies to hoard resources!

Some kids go to church, my kids watch Star Trek with me. I’m planning to do a second round when my 4-year-old turns 10. Maybe Deep Space 9. And yes, I know that “true scifi fans” don’t like Star Trek. My father, brother, and husband are all scifi fans, and none of them like Star Trek. I kind of know why, and it’s why I’m making my kids watch it with me before they get all judgy.

One complaint I’ve considered having about Star Trek is that there’s no road map to get there. After all, how are people convinced to go from a system in which we don’t share resources to one where we do? How do we get to the point where everyone’s fed and clothed and can concentrate on their natural curiosity and desire to explore? Where everyone gets a good education? How can we expect alien races to collaborate with us when we can’t even get along with people who disagree about taxation and the purpose of government?

I’ve gotten over it though, by thinking about it as an aspirational exercise. Not everything has to be pragmatic. And it probably helps to have goals that we can’t quite imagine reaching.

For those of you who are with me, and love everything about the Star Trek franchise, please consider joining me soon for the new Star Trek movie that’s coming out today. Showtimes in NYC are here. See you soon!

Salt it up, baby!

An article in yesterday’s Science Times explained that limiting the salt in your diet doesn’t actually improve health, and could in fact be bad for you. That’s a huge turn-around for a public health rule that has run very deep.

How can this kind of thing happen?

Well, first of all epidemiologists use crazy models to make predictions on things, and in this case what happened was they saw a correlation between high blood pressure and high salt intake, and they saw a separate correlation between high blood pressure and death, and so they linked the two.

Trouble is, while very low salt intake might lower blood pressure a little bit, it also for what ever reason makes people die a wee bit more often.

As this Scientific American article explains, that “little bit” is actually really small:

Over the long-term, low-salt diets, compared to normal diets, decreased systolic blood pressure (the top number in the blood pressure ratio) in healthy people by 1.1 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) by 0.6 mmHg. That is like going from 120/80 to 119/79. The review concluded that “intensive interventions, unsuited to primary care or population prevention programs, provide only minimal reductions in blood pressure during long-term trials.” A 2003 Cochrane review of 57 shorter-term trials similarly concluded that “there is little evidence for long-term benefit from reducing salt intake.”

Moreover, some people react to changing their salt intake with higher, and some with lower blood pressure. Turns out it’s complicated.

I’m a skeptic, especially when it comes to epidemiology. None of this surprises me, and I don’t think it’s the last bombshell we’ll be hearing. But this meta-analysis also might have flaws, so hold your breath for the next pronouncement.

One last thing – they keep saying that it’s too expensive to do this kind of study right, but I’m thinking that by now they might realize the real cost of not doing it right is a loss of the public’s trust in medical research.

SEC Roundtable on credit rating agency models today

I’ve discussed the broken business model that is the credit rating agency system in this country on a few occasions. It directly contributed to the opacity and fraud in the MBS market and to the ensuing financial crisis, for example. And in this post and then this one, I suggest that someone should start an open source version of credit rating agencies. Here’s my explanation:

The system of credit ratings undermines the trust of even the most fervently pro-business entrepreneur out there. The models are knowingly games by both sides, and it’s clearly both corrupt and important. It’s also a bipartisan issue: Republicans and Democrats alike should want transparency when it comes to modeling downgrades- at the very least so they can argue against the results in a factual way. There’s no reason I can see why there shouldn’t be broad support for a rule to force the ratings agencies to make their models publicly available. In other words, this isn’t a political game that would score points for one side or the other.

Well, it wasn’t long before Marc Joffe, who had started an open source credit rating agency, contacted me and came to my Occupy group to explain his plan, which I blogged about here. That was almost a year ago.

Today the SEC is going to have something they’re calling a Credit Ratings Roundtable. This is in response to an amendment that Senator Al Franken put on Dodd-Frank which requires the SEC to examine the credit rating industry. From their webpage description of the event:

The roundtable will consist of three panels:

- The first panel will discuss the potential creation of a credit rating assignment system for asset-backed securities.

- The second panel will discuss the effectiveness of the SEC’s current system to encourage unsolicited ratings of asset-backed securities.

- The third panel will discuss other alternatives to the current issuer-pay business model in which the issuer selects and pays the firm it wants to provide credit ratings for its securities.

Marc is going to be one of something like 9 people in the third panel. He wrote this op-ed piece about his goal for the panel, a key excerpt being the following:

Section 939A of the Dodd-Frank Act requires regulatory agencies to replace references to NRSRO ratings in their regulations with alternative standards of credit-worthiness. I suggest that the output of a certified, open source credit model be included in regulations as a standard of credit-worthiness.

Just to be clear: the current problem is that not only is there wide-spread gaming, but there’s also a near monopoly by the “big three” credit rating agencies, and for whatever reason that monopoly status has been incredibly well protected by the SEC. They don’t grant “NRSRO” status to credit rating agencies unless the given agency can produce something like 10 letters from clients who will vouch for them providing credit ratings for at least 3 years. You can see why this is a hard business to break into.

The Roundtable was covered yesterday in the Wall Street Journal as well: Ratings Firms Steer Clear of an Overhaul – an unfortunate title if you are trying to be optimistic about the event today. From the WSJ article:

Mr. Franken’s amendment requires the SEC to create a board that would assign a rating firm to evaluate structured-finance deals or come up with another option to eliminate conflicts.

While lawsuits filed against S&P in February by the U.S. government and more than a dozen states refocused unflattering attention on the bond-rating industry, efforts to upend its reliance on issuers have languished, partly because of a lack of consensus on what to do.

I’m just kind of amazed that, given how dirty and obviously broken this industry is, we can’t do better than this. SEC, please start doing your job. How could allowing an open-source credit rating agency hurt our country? How could it make things worse?

WSJ: “When Your Boss Makes You Pay for Being Fat”

Going along with the theme of shaming which I took up yesterday, there was a recent Wall Street Journal article called “When Your Boss Makes You Pay for Being Fat” about new ways employers are trying to “encourage healthy living”, or otherwise described, “save money on benefits”. From the article:

Until recently, Michelin awarded workers automatic $600 credits toward deductibles, along with extra money for completing health-assessment surveys or participating in a nonbinding “action plan” for wellness. It adopted its stricter policy after its health costs spiked in 2012.

Now, the company will reward only those workers who meet healthy standards for blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides and waist size—under 35 inches for women and 40 inches for men. Employees who hit baseline requirements in three or more categories will receive up to $1,000 to reduce their annual deductibles. Those who don’t qualify must sign up for a health-coaching program in order to earn a smaller credit.

A few comments:

- This policy combines the critical characteristics of shaming, namely 1) a complete lack of empathy and 2) the shifting of blame for a problem entirely onto one segment of the population even though the “obesity epidemic” is a poorly understood cultural phenomenon.

- To the extent that there may be push-back against this or similar policies inside the workplace, there will be very little to stop employers from not hiring fat people in the first place.

- Or for that matter, what’s going to stop employers from using people’s full medical profiles (note: by this I mean the unregulated online profile that Acxiom and other companies collect about you and then sell to employers or advertisers for medical stuff – not the official medical records which are regulated) against them in the hiring process? Who owns the new-fangled health analytics models anyway?

- We do that already to poor people by basing their acceptance on credit scores.

When is shaming appropriate?

As a fat person, I’ve dealt with a lot of public shaming in my life. I’ve gotten so used to it, I’m more an observer than a victim most of the time. That’s kind of cool because it allows me to think about it abstractly.

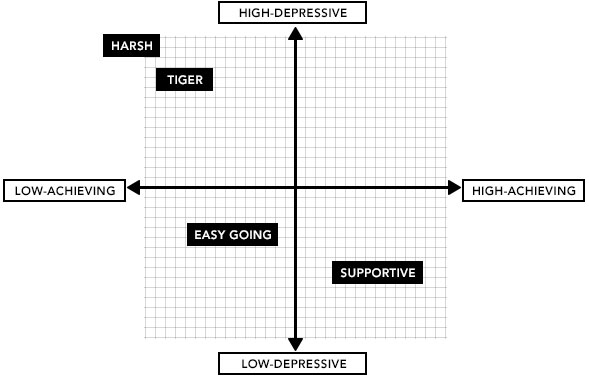

I’ve come up with three dimensions for thinking about this issue.

- When is shame useful?

- When is it appropriate?

- When does it help solve a problem?

Note it can be useful even if it doesn’t help solve a problem – one of the characteristics of shame is that the person doing the shaming has broken off all sense of responsibility for whatever the issue is, and sometimes that’s really the only goal. If the shaming campaign is effective, the shamed person or group is exhibited as solely responsible, and the shamer does not display any empathy. It hasn’t solved a problem but at least it’s clear who’s holding the bag.

The lack of empathy which characterizes shaming behavior makes it very easy to spot. And extremely nasty.

Let’s look at some examples of shaming through this lens:

Useful but not appropriate, doesn’t solve a problem

Example 1) it’s both fat kids and their parents who are to blame for childhood obesity:

Example 2) It’s poor mothers that are to blame for poverty:

These campaigns are not going to solve any problems, but they do seem politically useful – a way of doubling down on the people suffering from problems in our society. Not only will they suffer from them, but they will also be blamed for them.

Inappropriate, not useful, possibly solving a short-term discipline problem

Let’s go back to parenting, which everyone seems to love talking about, if I can go by the number of comments on my recent post in defense of neglectful parenting.

One of my later commenters, Deane, posted this article from Slate about how the Tiger Mom approach to shaming kids into perfection produces depressed, fucked-up kids:

Hey parents: shaming your kids might solve your short-term problem of having independent-minded kids, but it doesn’t lead to long-term confidence and fulfillment.

Appropriate, useful, solves a problem

Here’s when shaming is possibly appropriate and useful and solves a problem: when there have been crimes committed that affect other people needlessly or carelessly, and where we don’t want to let it happen again.

For example, the owner of the Bangladeshi factory which collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people got arrested and publicly shamed. This is appropriate, since he knowingly put people at risk in a shoddy building and added three extra floors to improve his profits.

Note shaming that guy isn’t going to bring back those dead people, but it might prevent other people from doing what he did. In that sense it solves the problem of seemingly nonexistent safety codes in Bangladesh, and to some extent the question of how much we Americans care about cheap clothes versus conditions in factories which make our clothes. Not completely, of course. Update: Major Retailers Join Plan for Greater Safety in Bangladesh

Another example of appropriate shame would be some of the villains of the financial crisis. We in Alt Banking did our best in this regard when we made the 52 Shades of Greed card deck. Here’s Robert Rubin:

Conclusion

I’m no expert on this stuff, but I do have a way of looking at it.

One thing about shame is that the people who actually deserve shame are not particularly susceptible to feeling it (I saw that first hand when I saw Ina Drew in person last month, which I wrote about here). Some people are shameless.

That means that shame, whatever its purpose, is not really about making an individual change their behavior. Shame is really more about setting the rules of society straight: notifying people in general about what’s acceptable and what’s not.

From my perspective, we’ve shown ourselves much more willing to shame poor people, fat people, and our own children than to shame the actual villains who walk among us who deserve such treatment.

Shame on us.

Aunt Pythia’s advice: online dating, probabilistic programming, children, and sex in the teacher’s lounge

Aunt Pythia is yet again gratified to find a few new questions in her inbox this morning, but as usual, she’s running quite low. After reading and enjoying the column below, please consider making some fabricated, melodramatic dilemma up out of whole cloth, preferably combining sex with something nerdy (see below for example) and, more importantly:

Please submit your fake sex question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I met this guy online and we met for three dates. I pinged him to meet up again, but he pleads busyness (he’s an academic, he has grading to do). Thing is, when I go on the dating website, I see that he’s been active–NOT communicating with me. I haven’t heard from him for a week. I sent him a quick, friendly email yesterday in which I did, yes, indicate that I was on the dating site and saw that he was active there. Is this guy a player, blowing me off, or genuinely busy with grading at the end of the semester?

Bewildered in Boston

Dear Bewildered,

I’m afraid that the evidence is pretty good that he’s blowing you off. To prevent this from happening in the future, I have a few suggestions.

Namely, you can’t prevent this kind of thing from happening in the future – not the part where some guy who seems nice blows you off. But you can prevent yourself from caring quite so much and stalking him online (honestly I don’t know why those dating sites allow you to check on other people’s activities. It seems like a recipe for disaster to me).

And the best way to do that is to have a rotation of at least 3 guys that you’re dating at a time, which means being in communication with even more than 3, until one gets serious and sticks. That way you won’t care if one of them is lying to you, and you probably won’t even notice, and it will be more about what you have time to deal with and less about fretting.

By the way, this guy could be genuinely busy and just using a few minutes online to procrastinate between grading papers. But you’ll never find that out if you stress out and send him accusing emails.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m an algebraic topologist trying to learn a bit of data science on the side. Around MIT I’ve heard a tremendous amount of buzz about “probabilistic programming,” mostly focused around its abilities to abstract away fancy mathematics and lower the barrier to entry faced by modelers. I am wondering if you, as a person who often gets her hands dirty with real data, have opinions on the QUERY formalism as espoused here? Are probabilistic programming languages the future of applied machine learning?

Curious Mathematician

Dear Curious,

I’ve never heard of this stuff before you just sent me the link. And I think I probably know why.

You see, the authors have a goal in mind, which is to claim that their work simulates human intelligence. For that they need some kind of sense of randomness, in order to claim they’re simulating creativity or at least some kind of prerequisite for creativity – something in the world of the unexpected.

But in my world, where we use algorithms to help see patterns and make business decisions, it’s kind of the opposite. If anything we want to interpretable algorithms, which we can explain in words. It wouldn’t make sense for us to explain what we’ve implemented and at some point in our explanation say, “… and then we added an element of randomness to the whole thing!”

Actually, that’s not quite true – I can think of one example. Namely, I’ve often thought that as a way of pushing back against the “filter bubble” effect, which I wrote about here, one should get a tailored list of search items plus something totally random. Of course there are plenty of ways to accomplish a random pick. I can only imagine using this for marketing purposes.

Thanks for the link!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I heard that some of the “real” reasons couples choose to have children are peer pressure and boredom. Is that true? I never understood the appeal of children, since they seem to suck the life (and money) out of people for one reason or another.

Tony’s Tentatively-tied Tubes

Dear TT-tT,

I give the same piece of advice to everyone I meet, namely: don’t have children!

I think there should be a test you have to take, where it’s really hard but it’s not graded, and also really expensive, and then the test itself shits all over your shirt, and then afterwards the test proctor tells you in no uncertain terms that you’ve failed the test, and that means you shouldn’t have children. And if you still want children after all of that, then maybe you should go ahead and have them, but only after talking to me or someone else with lots of kids about how much work they are.

Don’t get me wrong, I freaking LOVE my kids. But I’m basically insane. In any case I definitely don’t feel the right kind of insanity emanating from you, so please don’t have any kids.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I feel like a math fraud. I teach algebra and geometry but don’t have a math degree, (I just took the math exam for the single subject credential). I love math but fear I do every problem by brute force, taking twice as long as my fellow faculty members who show wicked fast cleverness in our meetings. Should i just sleep with everyone in the department to feel more like part of the gang? I am not finicky when it comes to orientation.

Faking under circumstances, keen math enthusiast

Dear Fuckme,

I really appreciate how you mixed the math question with the sex question. Right on right on!

I infer from documents like this that you are a high school math teacher. If you don’t mind I’ll address the sex question first, then the math question.

Honestly, and it may just be me, but I’m pretty sure it’s not, I’m hoping that all high school teachers have sex with each other at all times in the teachers’ lounge. Isn’t that what it’s for? Besides smoking up and complaining about annoying kids, of course. So yes, I totally approve of the plan to sleep with everyone in the department. Please report back.

Now on to the math: one thing that’s awesome about having a teacher who both loves math and is slow is that it’s incredibly relatable for the students. In other words, if you’re a student, what would you rather have for a teacher, someone who loves math and works through each problem diligently, or someone who is neutral or bored with math, and speeds through everything like a hot knife through warm butter?

Considering this, I’d say your best bet is to project your love for math to your students, by explaining your thinking at all times, and never forgetting how you thought about stuff when you were just learning it, and always telling them how cool math is. If you do all this you could easily be the best math teacher in that school.

Good luck with both projects!

Auntie P

——

Please submit your question to Aunt Pythia!

Caroline Chen on the ABC Conjecture

I was recently interviewed by Caroline Chen, a graduate student at Columbia’s Journalism School, about the status of Mochizuki’s proof the the ABC Conjecture. I think she found me through my previous post on the subject.

Anyway, her article just came out, and I like it and wanted to share it, even though I don’t like the title (“The Paradox of the Proof”) because I don’t like the word paradox (when someone calls something a paradox, it means they are making an assumption that they don’t want to examine). But that’s just a pet peeve – the article is nice, and it features my buddies Moon and Jordan and my husband Johan.

Read the article here.

E-discovery and the public interest (part 2)

Yesterday I wrote this short post about my concerns about the emerging field of e-discovery. As usual the comments were amazing and informative. By the end of the day yesterday I realized I needed to make a much more nuanced point here.

Namely, I see a tacit choice being made, probably by judges or court-appointed “experts”, on how machine learning is used in discovery, and I think that the field could get better or worse. I think we need to urgently discuss this matter, before we wander into a crazy place.

And to be sure, the current discovery process is fraught with opacity and human judgment, so complaining about those features being present in a machine learning version of discovery is unreasonable – the question is whether it’s better or worse than the current system.

Making it worse: private code, opacity

The way I see it, if we allow private companies to build black box machines that we can’t peer into, nor keep track of as they change versions, then we’ll never know why a given set of documents was deemed “relevant” in a given case. We can’t, for example, check to see if the code was modified to be more friendly to a given side.

Besides the healthy response to this new revenue source of competition for clients, the resulting feedback loop will likely be a negative one, whereby private companies use the cheapest version they can get away with to achieve the best results (for their clients) that they can argue for.

Making it better: open source code, reproducibility

What we should be striving for is to use only open source software, saved in a repository so we can document exactly what happened with a given corpus and a given version of the tools. It will still be an industry to clean the data and feed in the documents, train the algorithm (whilst documenting how that works), and interpreting the results. Data scientists will still get paid.

In other words, instead of asking for interpretability, which is a huge ask considering the massive scale of the work being done, we should, at the very least, be able to ask for reproducibility of the e-discovery, as well as transparency in the code itself.

Why reproducibility? Then we can go back in time, or rather scholars can, and test how things might have changed if a different version of the code were used, for example. This could create a feedback loop crucial to improve the code itself over time, and to improve best practices for using that code.

E-discovery and the public interest

Today I want to bring up a few observations and concerns I have about the emergence of a new field in machine learning called e-discovery. It’s the algorithmic version of discovery, so I’ll start there.

Discovery is part of the process in a lawsuit where relevant documents are selected, pored over, and then handed to the other side. Nowadays, of course, there are more and more documents, almost all electronic, typically including lots of e-mails.

If you’re talking about a big lawsuit, there could be literally millions of documents to wade through, and that takes a lot of time for humans to do, and it can be incredibly expensive and time-consuming. Enter the algorithm.

With advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP), a machine algorithm can sort emails or documents by topic (after getting the documents into machine-readable form, cleaning, and deduping) and can in general do a pretty good job of figuring out whether a given email is “relevant” to the case.

And this is already happening – the Wall Street Journal recently reported that the Justice Department allowed e-discovery for a case involving the merger of two beer companies. From the article:

With the blessing of the Justice Department’s antitrust division, the lawyers loaded the documents into a program and manually reviewed a batch to train the software to recognize relevant documents. The manual review was repeated until the Justice Department and Constellation were satisfied that the program could accurately predict relevance in the rest of the documents. Lawyers for Constellation and Crown Imports used software developed by kCura Corp., which lists the Justice Department as a client.

In the end, Constellation and Crown Imports turned over hundreds of thousands of documents to antitrust investigators.

Here are some of my questions/ concerns:

- These algorithms are typically not open source – companies like kCura make good money doing these jobs.

- That means that they could be wrong, possibly in subtle ways.

- Or maybe not so subtle ways: maybe they’ve been trained to find documents that are both “relevant” and “positive” for a given side.

- In any case, the laws of this country will increasingly depend on a black box algorithm that is no accessible to the average citizen.

- Is that in the public’s interest?

- Is that even constitutional?

The NYC Data Skeptics Meetup

One thing I’m super excited about at work is the new NYC Data Skeptics Meetup we’re organizing. Here’s the description of our mission:

The hype surrounding Big Data and Data Science is at a fever pitch with promises to solve the world’s business and social problems, large and small. How accurate or misleading is this message? How is it helping or damaging people, and which people? What opportunities exist for data nerds and entrepreneurs that examine the larger issues with a skeptical view?

This Meetup focuses on mathematical, ethical, and business aspects of data from a skeptical perspective. Guest speakers will discuss the misuse of and best practices with data, common mistakes people make with data and ways to avoid them, how to deal with intentional gaming and politics surrounding mathematical modeling, and taking into account the feedback loops and wider consequences of modeling. We will take deep dives into models in the fields of Data Science, statistics, finance, economics, healthcare, and public policy.

This is an independent forum and open to anyone sharing an interest in the larger use of data. Technical aspects will be discussed, but attendees do not need to have a technical background.

A few things:

- Please join us!

- I wouldn’t blame you for not joining until we have a confirmed speaker, so please suggest speakers for us! I have a bunch of people in mind I’d absolutely love to see but I’d love more ideas. And I’m thinking broadly here – of course data scientists and statisticians and economists, but also lawyers, sociologists, or anyone who works with data or the effects of data.

- If you are skeptical of the need for yet another data-oriented Meetup (or other regular meeting), please think about it this way: there are not that many currently active groups which aren’t afraid to go into the technical weeds and also not obsesses with a simplistic, sound bite business take-away. But please tell me if I’m wrong, I’d love to reach out to people doing similar things.

- Suggest a better graphic for our Meetup than our current portrait of Isaac Asimov.

In defense of neglectful parenting

As I promised yesterday, I want to respond to this New Yorker article “The Child Trap: the rise of overparenting,” which my friend Chris Wiggins forwarded to me.

The premise of the article is that nowadays we spoil our kids, force them to do a bunch of adult-supervised after-school activities, and generally speaking hover over them, even once they’re adults, and it’s all the fault of technology and (who else?) guilty working mothers. In particular, it makes kids, especially college-age kids, incredibly selfish and emotionally weak.

They interview overparenting skeptics as well, who seem to be focused on the spoiling and indulgent side of overparenting:

As for the steamy devotion shown by later generations of parents, what it has produced are snotty little brats filled with “anger at such abstract enemies as The System,” and intellectual lightweights, certain (because their parents told them so) that their every thought is of great consequence. Epstein says that, when he was teaching, he was often tempted to write on his students’ papers: “D-. Too much love in the home.”

I’m basically in agreement with the article, although I’d go further at some moments and not as far at others.

For example, with spoiling: in my experience, “spoiled kids” is just a phrase people use to describe kids that have acclimated perfectly to their imperfect environments.

So if you train your kids to whine, by saying “no” but then giving in if they whine, then it’s on you, as a parent, to realize you’ve created a perverted environment. Your kid is essentially doing what they’re told. If a 15-year-old kid sitting next to the refrigerator yells for his mom across the living room to get him a glass of juice (I’ve seen this happen) and the mom in question does what she’s been told, then guess what? That kid has learned how to make juice appear.

When you eventually release a spoiled kid in the real world, where there’s nobody to get him juice when he demands it, and when things don’t magically happen because they whine, then all you’ve done is made their entry into that real world harder for them. And in that sense you’ve fucked up.

Because isn’t our main job as parents to make sure they can survive on their own as productive, kind, happy individuals?

On the separate subject of getting your kid to be super gifted through Baby Mozart CD’s and after-school activities (from the article: “You can’t smoke pot or lose your virginity at lacrosse practice.”), it’s an approach to parenting I find toxic, and here’s why.

I think the attention you give to your kids when you force them to practice violin or study for standardized tests is an anxious attention. And just as marriages break down when the majority of interactions between spouses consist of negotiating child pick-ups rather than exchanging ideas and affection, the relationship between parents and kids can similarly suck if you spend more time nagging and worrying about their externally perceived status than enjoying them as people.

And that’s just the day-to-day complaint I have. The larger complaint I have about all this overparenting is that the anxiety we have for our kids’ futures is being projected onto them, and it often translates as a lack of faith in their ability to make it on their own. So rather than preparing them to live independent lives, we’re undermining them from the get-go.

Actually, I’d go one step further. One thing I enjoyed as a latch-key kid of a working mother (who carried no guilt at all) was that, for most things, I was never under scrutiny. What I did with my time after school was up to me, although I wasn’t supposed to watch TV all the time (and I sometimes did anyway, of course – we should all be able to experiment with breaking rules). What I thought about and who I hung out with with were completely up to me – and by the time I was 17 and had my license and a crappy old car, I did some admittedly pretty outrageous things. My parents were so busy they often didn’t even look at my report card in a given year.

In other words, I had a kind of privacy and freedom that I don’t think many kids today can even imagine, although I do my best to provide my kids with a similar environment.

That’s not to say my childhood was perfect, nor were my parents totally neglectful – we had dinner together every night, they gave me a safe environment to roam around in, and I had a bedtime which was enforced. If I hadn’t been doing my homework, I’m pretty sure they would have been on top of me to do it, but I did it on my own. And I was under scrutiny for one thing, namely being mildly overweight, which caused me enough pain then that I understood scrutiny itself to be the source of insecurity.

I can’t help thinking that my childhood would have been a lot worse if my parents had fretted over how I spend my afternoons, even though it’s hard to imagine. It makes me wonder where I’d be now if I hadn’t had those afternoons to spend making unlikely friends, taking on jobs cleaning houses for cash, buying books to read, and generally speaking deciding who I was going to grow up to be.

Do what I want or do what I really want

I’m on my way out to a picnic in Central Park on this glorious Sunday morning, and I plan to write a much more thorough post in response to this New Yorker article on overparenting that my friend Chris Wiggins sent me, but today I just wanted to impart one idea I’ve developed as a mother of three boys.

Namely, kids don’t ever want to do what you want them to do, especially when they’re tired, and it’s awful to feel helpless to get them to something without ridiculous, possibly empty threats, or something worse.

What to do?

My solution is pretty simple, and it works great, at least in my experience. Namely, if I’m getting no response from a reasonable request from my, say, 4-year-old, then I form a separate request which is easier for me and less good for them. And then I offer him a choice between doing what I want or doing what I really want.

Example: it’s bedtime (i.e. 7pm, which we will come back to in further post, which I’m considering calling “In defense of neglectful parenting”) and my kid doesn’t want to stop watching Star Wars Lego movies on Youtube. I’ve asked repeatedly for him to pause the movie so he can brush his teeth, get into his pajamas, and have me read his favorite bedtime story (currently: “Peter and the Shadow Thieves”).

Instead of screaming, picking him up and dragging him to the bathroom, which is increasingly difficult since he’s the size of a 6-year-old, I simply make him an offer:

Either you come brush your teeth right now and I read to you, or you come brush your teeth now and I don’t read to you, and you’ll have to go to bed without a bedtime story. I’m going to count to five and if you don’t come to the bathroom to brush your teeth when I get to “5” then no story.

Here’s the thing. It’s important that he knows I’m serious. I will actually not read to him if he doesn’t hurry up. To be fair, I only had to follow through with this exactly once for him to understand the seriousness of this kind of offer.

What I like about this is the avoidance of drama, empty threats, and physical coercion, or what’s just as annoying, a wasted evening of arguing with an exhausted child about “why there are bedtimes”, which happens so easily without a strategy in place.

Aunt Pythia’s advice – nose rings, breakups, itchy fingers, and data science

Aunt Pythia is yet again gratified to find a few new questions in her inbox this morning, but as usual, she’s running quite low. After reading and enjoying the column below, please consider making some fabricated, melodramatic dilemma up out of whole cloth and, more importantly:

Please submit your fake question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Can I have a nose piercing and still be taken seriously as an academic in Mathematics?

Math Dyke

Dear Math Dyke,

Actually, I think you can. Mathematicians may be elitist snobs about some things, but it’s not about the way they’re dressed. They tend to be pretty open-minded about physically presented strangeness. Plus they’ll probably just think it’s some kind of cultural signifier that they don’t understand.

Don’t let this fear hold you back from getting your nose pierced if that’s what you wanna do! It’ll look fabulous!

Auntie P

——

Hi Aunt Pythia,

I was recently dating this girl, and thought I had no feelings towards her other than enjoying her company and being attracted to her. Recently, after dating for a month or so, she wanted to have a “talk” and make things serious. I confessed that I did not love her, but told her that I did not expect these feeings at this point. She dumped me. What could I have done? Should I lie? Thanks 😦

Adones

Dear Adones,

First of all, I’m sympathetic to your viewpoint. But I’m also sympathetic to hers – and I’m much more like her myself.

People just move at different paces, and yours was too slow for her. I think the conversation you two had was probably the best thing, and I’m glad you didn’t lie.

My guess is that, from her perspective, you guys had been dating for a full six weeks (I’m interpreting your “or so” broadly), that you were pleasant yet tepid, and that she just wanted more from her love life than that. She didn’t get the impression, based on your conversation, that passion was around the corner, so why bother? From her vantage point, she deserves an interesting and exciting love life.

But don’t despair: there are other women who want to move slowly, especially if they’re not interested in having kids any time soon. My advice is to go find someone with a slower pace that matches yours!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I love to twiddle my fingers . . . but I never took up knitting, for example, because I figured you have to have the mind of an accountant to keep track of the pattern. I supposed I could crank out a scarf or two …. Plus, wool is so itchy. (I note that linen is an option?). Should I be discouraged?

ItchyFingers

Dear Itchy,

One possibility is to have the “mind of an accountant” (I put this in quotes because I know a few accountants that may be offended by the assumptions) and count out each stitch as you go. Or you could instead have the mind of an artist, and not worry about imperfections in stitch count, since they add texture and individuality to your project. Or, you could do what I do, and have the mind of a mathematician, and choose or design patterns that allow you every now and then think, but mostly just happily knit whilst watching Star Trek or something.

The real reason I love knitting is that I love color and I love the touch of yarn. I just can’t get enough of touching it. And most luxury wool yarn is not itchy at all. My suggestion is to go to a yarn store and touch everything in sight. It’s what people do, don’t worry, nobody will be surprised.

Aunt P

p.s. if you live in New York, try Knitty City on 79th near Broadway.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I don’t have a math background. I studied Political Science in college. But I’m fascinated by data science and want to learn more. If I keep chugging along, teaching myself things, do you think this is a viable career? I’m teaching myself programming right now (JavaScript, Ruby), a bit of R, a bit of SAS.

Don’t Always Take Advice

Dear DATA,

I do think you need to understand the math behind the algorithms in order to really be a good data science (as I explained in this post). But that doesn’t mean you have to have a math background – you can give yourself a math foreground right now. So yes, if you are willing to really go deep and understand these algorithms from top to bottom, of course you can become a data scientist. There’s no secret property of college learning that makes it somehow better, after all. And there are tons of online resources that you can use for this stuff, as well as the book I’m writing which will be out soon.

One more piece of advice: get yourself a github account and store your code for projects in that, as well as written descriptions of what problems you’ve solved with your code. Since you don’t have a standard background in math and stats and CS, you’ll have to have evidence that you really can do this stuff.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your question to Aunt Pythia!

What does it mean that our public square is a private place?

I just read this opinion piece written by Jillian York and published by Aljazeera.com. York discusses “How social network policies are changing speech and privacy norms” and she makes the point that there’s a big difference between our legal rights as citizens and the way Facebook has defined its policies, and by extension our “rights” inside Facebook.

So, for example, there’s the question of whether we can show pictures of breastfeeding our children on Facebook. The policy on this has changed – nowadays they say yes, but they used to remove such pictures.

Another example might be more important: whether you can be anonymous. As York points out, Facebook might have an opinion about this, and Zuckerberg seems to – she quotes him as having said “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity” – and yet their vested interest in this question is related to making sure they’ve accurately targeted you for advertisements.

I want to make the case that the “real-life” version of anonymity in Facebook is really just privacy in the simplest sense.

If I am even half-aware of the extent of the surveillance and tracking that goes on when I log into Facebook under my real name, which I don’t even think I am, then I’d tend to use a separate browser, with cleared cookies, and an anonymous Facebook account in order to do absolutely anything without it being tracked. In other words, anonymity is what it takes to do anything privately on Facebook.

Now, you might argue that I can just not go to Facebook at all if I want to do private things, and I’m sure that’s Facebook position as well. But the truth is, Facebook is the world’s public square. Some enormous fraction of the world visits Facebook at least once a week. Exclusion from this would be a big deal.

In any case, it’s weird that decisions like this, that affect our notions of privacy, are being decided by some dude who’s probably thinking more about ad revenue than anything else, under pressure from shareholders.

Not that it’s a new problem. When I was growing up in Lexington, MA, over the cold winters we’d hang out in the Burlington Mall. It was the public square of its time, and yes it was utterly commercial and private, and of course they excluded anyone who they didn’t like the looks of, with security guards. Even so, they didn’t check ID’s at the door.

The rise of big data, big brother

I recently read an article off the newsstand called The Rise of Big Data.

It was written by Kenneth Neil Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger and it was published in the May/June 2013 edition of Foreign Affairs, which is published by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). I mention this because CFR is an influential think tank, filled with powerful insiders, including people like Robert Rubin himself, and for that reason I want to take this view on big data very seriously: it might reflect the policy view before long.

And if I think about it, compared to the uber naive view I came across last week when I went to the congressional hearing about big data and analytics, that would be good news. I’ll write more about it soon, but let’s just say it wasn’t everything I was hoping for.

At least Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger discuss their reservations regarding “big data” in this article. To contrast this with last week, it seemed like the only background material for the hearing, at least for the congressmen, was the McKinsey report talking about how sexy data science is and how we’ll need to train an army of them to stay competitive.

So I’m glad it’s not all rainbows and sunshine when it comes to big data in this article. Unfortunately, whether because they’re tied to successful business interests, or because they just haven’t thought too deeply about the dark side, their concerns seem almost token, and their examples bizarre.

The article is unfortunately behind the pay wall, but I’ll do my best to explain what they’ve said.

Datafication

First they discuss the concept of datafication, and their example is how we quantify friendships with “likes”: it’s the way everything we do, online or otherwise, ends up recorded for later examination in someone’s data storage units. Or maybe multiple storage units, and maybe for sale.

They formally define later in the article as a process:

… taking all aspect of life and turning them into data. Google’s augmented-reality glasses datafy the gaze. Twitter datafies stray thoughts. LinkedIn datafies professional networks.

Datafication is an interesting concept, although as far as I can tell they did not coin the word, and it has led me to consider its importance with respect to intentionality of the individual.

Here’s what I mean. We are being datafied, or rather our actions are, and when we “like” someone or something online, we are intending to be datafied, or at least we should expect to be. But when we merely browse the web, we are unintentionally, or at least passively, being datafied through cookies that we might or might not be aware of. And when we walk around in a store, or even on the street, we are being datafied in an completely unintentional way, via sensors or Google glasses.

This spectrum of intentionality ranges from us gleefully taking part in a social media experiment we are proud of to all-out surveillance and stalking. But it’s all datafication. Our intentions may run the gambit but the results don’t.

They follow up their definition in the article, once they get to it, with a line that speaks volumes about their perspective:

Once we datafy things, we can transform their purpose and turn the information into new forms of value

But who is “we” when they write it? What kinds of value do they refer to? As you will see from the examples below, mostly that translates into increased efficiency through automation.

So if at first you assumed they mean we, the American people, you might be forgiven for re-thinking the “we” in that sentence to be the owners of the companies which become more efficient once big data has been introduced, especially if you’ve recently read this article from Jacobin by Gavin Mueller, entitled “The Rise of the Machines” and subtitled “Automation isn’t freeing us from work — it’s keeping us under capitalist control.” From the article (which you should read in its entirety):

In the short term, the new machines benefit capitalists, who can lay off their expensive, unnecessary workers to fend for themselves in the labor market. But, in the longer view, automation also raises the specter of a world without work, or one with a lot less of it, where there isn’t much for human workers to do. If we didn’t have capitalists sucking up surplus value as profit, we could use that surplus on social welfare to meet people’s needs.

The big data revolution and the assumption that N=ALL

According to Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger, the Big Data revolution consists of three things:

- Collecting and using a lot of data rather than small samples.

- Accepting messiness in your data.

- Giving up on knowing the causes.

They describe these steps in rather grand fashion, by claiming that big data doesn’t need to understand cause because the data is so enormous. It doesn’t need to worry about sampling error because it is literally keeping track of the truth. The way the article frames this is by claiming that the new approach of big data is letting “N = ALL”.

But here’s the thing, it’s never all. And we are almost always missing the very things we should care about most.

So for example, as this InfoWorld post explains, internet surveillance will never really work, because the very clever and tech-savvy criminals that we most want to catch are the very ones we will never be able to catch, since they’re always a step ahead.

Even the example from their own article, election night polls, is itself a great non-example: even if we poll absolutely everyone who leaves the polling stations, we still don’t count people who decided not to vote in the first place. And those might be the very people we’d need to talk to to understand our country’s problems.

Indeed, I’d argue that the assumption we make that N=ALL is one of the biggest problems we face in the age of Big Data. It is, above all, a way of excluding the voices of people who don’t have the time or don’t have the energy or don’t have the access to cast their vote in all sorts of informal, possibly unannounced, elections.

Those people, busy working two jobs and spending time waiting for buses, become invisible when we tally up the votes without them. To you this might just mean that the recommendations you receive on Netflix don’t seem very good because most of the people who bother to rate things are Netflix are young and have different tastes than you, which skews the recommendation engine towards them. But there are plenty of much more insidious consequences stemming from this basic idea.

Another way in which the assumption that N=ALL can matter is that it often gets translated into the idea that data is objective. Indeed the article warns us against not assuming that:

… we need to be particularly on guard to prevent our cognitive biases from deluding us; sometimes, we just need to let the data speak.

And later in the article,

In a world where data shape decisions more and more, what purpose will remain for people, or for intuition, or for going against the facts?

This is a bitch of a problem for people like me who work with models, know exactly how they work, and know exactly how wrong it is to believe that “data speaks”.

I wrote about this misunderstanding here, in the context of Bill Gates, but I was recently reminded of it in a terrifying way by this New York Times article on big data and recruiter hiring practices. From the article:

“Let’s put everything in and let the data speak for itself,” Dr. Ming said of the algorithms she is now building for Gild.

If you read the whole article, you’ll learn that this algorithm tries to find “diamond in the rough” types to hire. A worthy effort, but one that you have to think through.

Why? If you, say, decided to compare women and men with the exact same qualifications that have been hired in the past, but then, looking into what happened next you learn that those women have tended to leave more often, get promoted less often, and give more negative feedback on their environments, compared to the men, your model might be tempted to hire the man over the woman next time the two showed up, rather than looking into the possibility that the company doesn’t treat female employees well.

In other words, ignoring causation can be a flaw, rather than a feature. Models that ignore causation can add to historical problems instead of addressing them. And data doesn’t speak for itself, data is just a quantitative, pale echo of the events of our society.

Some cherry-picked examples

One of the most puzzling things about the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article is how they chose their “big data” examples.

One of them, the ability for big data to spot infection in premature babies, I recognized from the congressional hearing last week. Who doesn’t want to save premature babies? Heartwarming! Big data is da bomb!

But if you’re going to talk about medicalized big data, let’s go there for reals. Specifically, take a look at this New York Times article from last week where a woman traces the big data footprints, such as they are, back in time after receiving a pamphlet on living with Multiple Sclerosis. From the article:

Now she wondered whether one of those companies had erroneously profiled her as an M.S. patient and shared that profile with drug-company marketers. She worried about the potential ramifications: Could she, for instance, someday be denied life insurance on the basis of that profile? She wanted to track down the source of the data, correct her profile and, if possible, prevent further dissemination of the information. But she didn’t know which company had collected and shared the data in the first place, so she didn’t know how to have her entry removed from the original marketing list.

Two things about this. First, it happens all the time, to everyone, but especially to people who don’t know better than to search online for diseases they actually have. Second, the article seems particularly spooked by the idea that a woman who does not have a disease might be targeted as being sick and have crazy consequences down the road. But what about a woman is actually is sick? Does that person somehow deserve to have their life insurance denied?

The real worries about the intersection of big data and medical records, at least the ones I have, are completely missing from the article. Although they did mention that “improving and lowering the cost of health care for the world’s poor” inevitable will lead to “necessary to automate some tasks that currently require human judgment.” Increased efficiency once again.

To be fair, they also talked about how Google tried to predict the flu in February 2009 but got it wrong. I’m not sure what they were trying to say except that it’s cool what we can try to do with big data.

Also, they discussed a Tokyo research team that collects data on 360 pressure points with sensors in a car seat, “each on a scale of 0 to 256.” I think that last part about the scale was added just so they’d have more numbers in the sentence – so mathematical!

And what do we get in exchange for all these sensor readings? The ability to distinguish drivers, so I guess you’ll never have to share your car, and the ability to sense if a driver slumps, to either “send an alert or atomatically apply brakes.” I’d call that a questionable return for my investment of total body surveillance.

Big data, business, and the government

Make no mistake: this article is about how to use big data for your business. It goes ahead and suggests that whoever has the biggest big data has the biggest edge in business.

Of course, if you’re interested in treating your government office like a business, that’s gonna give you an edge too. The example of Bloomberg’s big data initiative led to efficiency gain (read: we can do more with less, i.e. we can start firing government workers, or at least never hire more).

As for regulation, it is pseudo-dealt with via the discussion of market dominance. We are meant to understand that the only role government can or should have with respect to data is how to make sure the market is working efficiently. The darkest projected future is that of market domination by Google or Facebook:

But how should governments apply antitrust rules to big data, a market that is hard to define and is constantly changing form?

In particular, no discussion of how we might want to protect privacy.

Big data, big brother

I want to be fair to Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger, because they do at least bring up the idea of big data as big brother. Their topic is serious. But their examples, once again, are incredibly weak.

Should we find likely-to-drop-out boys or likely-to-get-pregnant girls using big data? Should we intervene? Note the intention of this model would be the welfare of poor children. But how many models currently in production are targeting that demographic with that goal? Is this in any way at all a reasonable example?

Here’s another weird one: they talked about the bad metric used by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in the Viet Nam War, namely the number of casualties. By defining this with the current language of statistics, though, it gives us the impression that we could just be super careful about our metrics in the future and: problem solved. As we experts in data know, however, it’s a political decision, not a statistical one, to choose a metric of success. And it’s the guy in charge who makes that decision, not some quant.

Innovation

If you end up reading the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article, please also read Julie Cohen’s draft of a soon-to-be published Harvard Law Review article called “What Privacy is For” where she takes on big data in a much more convincing and skeptical light than Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger were capable of summoning up for their big data business audience.

I’m actually planning a post soon on Cohen’s article, which contains many nuggets of thoughtfulness, but for now I’ll simply juxtapose two ideas surrounding big data and innovation, giving Cohen the last word. First from the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article:

Big data enables us to experiment faster and explore more leads. These advantages should produce more innovation

Second from Cohen, where she uses the term “modulation” to describe, more or less, the effect of datafication on society:

When the predicate conditions for innovation are described in this way, the problem with characterizing privacy as anti-innovation becomes clear: it is modulation, not privacy, that poses the greater threat to innovative practice. Regimes of pervasively distributed surveillance and modulation seek to mold individual preferences and behavior in ways that reduce the serendipity and the freedom to tinker on which innovation thrives. The suggestion that innovative activity will persist unchilled under conditions of pervasively distributed surveillance is simply silly; it derives rhetorical force from the cultural construct of the liberal subject, who can separate the act of creation from the fact of surveillance. As we have seen, though, that is an unsustainable fiction. The real, socially-constructed subject responds to surveillance quite differently—which is, of course, exactly why government and commercial entities engage in it. Clearing the way for innovation requires clearing the way for innovative practice by real people, by preserving spaces within which critical self-determination and self-differentiation can occur and by opening physical spaces within which the everyday practice of tinkering can thrive.

Why we should break up the megabanks (#OWS)

Today is May Day, and my Occupy group and I are planning to join in the actions all over the city this afternoon. At 2:00 I’m going to be at Cooper Square, where Free University is holding a bunch of teach-ins, and I’m giving one entitled “Why we should break up the megabanks.” I wanted to get my notes for the talk down in writing beforehand here.

The basic reasons to break up the megabanks are these:

- They hold too much power.

- They cost too much.

- They get away with too much.

- They make things worse.

Each requires explanation.

Megabanks hold too much power

When Paulson went to Congress to argue for the bailout in 2008, he told them that the consequences of not acting would be a total collapse of the financial system and the economy. He scared Congress and the American people to such an extent that the banks managed to receive $700 billion with no strings attached. Even though half of that enormous pile of money was supposed to go to help homeowners threatened with foreclosures, almost none of it did, because the banks found other things to do with it.

The power of megabanks doesn’t only exert itself through the threat of annihilation, though. It also flows through lobbyists who water down Dodd-Frank (or really any policy that banks don’t like) and through “the revolving door,” the men and women who work for Treasury, the White House, and regulators about half the time and sit in positions of power in the megabanks the other half of their time, gaining influence and money and retiring super rich.

It is unreasonable to expect to compete with this kind of insularity and influence of the megabanks.

They cost too much

The bailout didn’t work and it’s still going on. And we certainly didn’t “make money” on it, compared to what the government could have expected if we had invested differently.

But honestly it’s too narrow to think about money alone, because what we really need to consider is risk. And there we’ve lost a lot: when we bailed them out, we took on the risk of the megabanks, and we have simply done nothing to return it. Ultimately the only way to get rid of that costly risk is to break them up once and for all to a size that they can reasonably and obviously be expected to fail.

Make no mistake about it: risk is valuable. It may not be quantifiable at a moment of time, but over time it becomes quite valuable and quantifiable indeed, in various ways.

One way is to think about borrowing costs and long-term default probabilities, and there the estimates have varied but we’ve seen numbers such as $83 billion per year modeled. Few people dispute that it’s the right order of magnitude.

They get away with too much

There doesn’t seem to be a limit to what the megabanks can get away with, which we’ve seen with HSBC’s money laundering from terrorists and drug cartels, we’ve seen with Jamie Dimon and Ina Drew lying to Congress about fucking with their risk models, we’ve seen with countless fraudulent and racist practices with mortgages and foreclosures and foreclosure reviews, not to mention setting up customers to fail in deals made to go bad, screwing municipalities and people with outrageous fees, shaving money off of retirement savings, and manipulating any and all markets and rates that they can to increase their bonuses.

The idea of a financial sector is to grease the wheels of commerce, to create a machine that allows the economy to work. But in our case we have a machine that’s taken over the economy instead.

They make things worse

Ultimately the best reason to break them up right now, the sooner the better, is that the incentives are bad and getting worse. Now that they live in a officially protected zone, there is even less reason for them then there used to be to rein in risky practices. There is less reason for them to worry about punishments, since the SEC’s habit of letting people off without jailtime, meaningful penalties, or even admitting wrongdoing has codified the lack of repercussions for bad behavior.