Archive

Parenting through benign neglect

In 1985, when I was 12 years old, I went to communist Budapest by myself, for a month. I’d met and befriended two Hungarian families when I was 11 and they were living next door to me for a year in Lexington, Massachusetts, and when they went back to Budapest they invited me to visit.

So it wasn’t like I didn’t have a place to sleep when I got there, but even so, my parents decided that yes, a trip across the world into a country that needed a visa to enter, that didn’t have a hard currency, and that didn’t have consistent phone lines at post offices (never mind at people’s homes, that was out of the question) was a great place for their 12-year-old daughter to visit by herself.

I also almost didn’t make the correct connection in Zurich, and I am seriously wondering what would have happened if I’d missed my flight. How would I have connected with my hosts? Where would I have slept? What would I have done for money?

I did make my flight, though, and I did meet my hosts, and the worst thing that happened to me was that when the cows got sick, I got sick – very sick. And to be fair, I turned 13 when I was there.

I came home appreciating milk pasteurization, and to a lesser extent milk homogenization. I was skinnier and less spoiled, I knew what really good peaches tasted like, and I was completely sick of paprika. Overall it was a good trip, and I’m glad I went.

And if I or my parents had been more cautious, I wouldn’t have gone. Goes to show you, sometimes it’s good not to think too hard about what could go wrong.

Unfortunately, I’m older now, and my 13-year-old just got on a plane to San Francisco by himself to attend a Model UN camp at Stanford. And all I can think about it what might go wrong.

Don’t get me wrong, it didn’t stop me from putting him on the plane. I’m trying to channel my parents’ benign neglect child-raising technique from which I benefitted so tremendously. He’s got a working cell phone, plenty of cash, and my BFF Becky will be within driving distance of him over there.

Hey, it’s not like he’s going to North Korea – which is, by the way, where he requested to be sent – and I’m pretty sure the milk there is pasteurized, as long as you avoid farmer’s markets.

Aunt Pythia: alive and well!

Aunt Pythia is just bursting with love and admiration for the courageous and articulate readers that sent in their thought-provoking and/or heart-rending questions in the last week which got her off life support and back into fighting shape.

On the one hand, Aunt Pythia did’t want to be a histrionic burden to you all, but on the other hand clearly histrionics work, so there it is. Thank you thank you thank you for allowing histrionics to work.

That’s not to say you should rest on your laurels, readers! First of all, Aunt Pythia always needs new questions (you don’t want her to get sick again, right?), and secondly, I’ve heard laurels can be quite prickly.

In other words,

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Isn’t the distribution thing kind of REALLY IMPORTANT for how we think of the sexual partner thing? If fifty women are getting it on with one man, while the other 49 men are, uh, monks, or vice versa, depending on the universe you live in, that certainly influences how you think about stereotypes.

Ms. Hold On A Second

Dear HOAS,

Yes it is, but the average should take care of that as long as the sample size is large enough to have that one lucky man represented, as well as the 49 unlucky men, in the correct proportions.

Let’s go with this a bit. How fat-tailed would sexual practice have to be to make this a problem? After all, there are distributions that defy basic intuition around this – look at the Cauchy Distribution, which has no defined mean or variance, for example. Maybe that’s what’s going on?

Hold on one cotton-picking second! We have a finite number of people in the world, so obviously this is not what’s going on – the average number of sexual partners exists, even if it’s a pain in the ass to compute!

But I’m willing to believe that there’s a sampling bias at work here. Maybe female prostitutes are excluded from surveys, for example. And if men always included their visits to prostitutes, that would introduce a bias.

I’ll go on record saying I doubt that explains the discrepancy, although to be mathematical about it I’d need to have an estimate of how much prostitute sex happens and with how many men. I don’t have that data but maybe someone does.

And of course it’s probably not just one thing. Some combination of the surveys being for college students, and fewer prostitutes being at college, and some actual lying. But my money’s on the lying every time.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m not sure this is the correct forum for this question, but here it goes: I come from an economics/econometrics background, where the statistical modeling tool of choice is Stata. I now work at an organization in a capacity that is heavy on statistical modeling, in some cases (but not always) working with “Big Data”.

There is some freedom in terms of the tools we can use, but nobody uses Stata, to my knowledge. As somebody who is just starting out in this industry, I’m trying to get a pulse on which tool I should invest the time into learning, SAS or R. Do you have an opinion either way?

Lonely in Missouri

Dear Lonely,

Always go with the open source option. R, or even better, python. What with pandas and other recent packages, python is just fabulous.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a graduate student in math at a large state research school in the midwest, finishing in 2014. My question is about my advisor and my job plans.

First, here’s what I’m planning to do next year. My wife is a student in the same department as I am, and she’s also finishing next year. We both want to move to a big city. We’d settle for a Philadelphia or Seattle or really anywhere we can live without a car, but by “big city” I really mean New York. We’ve both lived there before and we like it better than anywhere else.

My wife wants a non-academic job. I’m going to apply for research postdocs. I should be a fairly strong candidate, but I’m no superstar and I definitely don’t think it’s assured that I’ll get one, especially with the limited set of places we’re willing to live. And that’s fine! I like the idea of being a professor, but there’s lots of other jobs that I think I’d like too. I know that I wouldn’t like living apart from my wife, or living somewhere that we hate.

My advisor has done a good job of making me into a researcher. The problem is that he’s just a difficult person. Less charitably, he’s an asshole (at least to me). He’s arrogant, rude, and demanding. The one time I ever told him he wasn’t treating me fairly (which I did politely, but in an email), he completely flipped out (in a series of emails) and told me that as his student, I had no right to talk to him that way.

I don’t want to make him sound like a complete monster: he’s from a culture that puts a lot of weight on respect and hierarchy, and I’ve seen him be empathetic and kind. But he absolutely cannot handle it if I disagree with him or don’t do what he says.

In all conversations we’ve had about my future, he seems to have no interest in what I actually want to do. I could have graduated last year, but my department had no problem letting me stay on so that I could finish at the same time as my wife. My advisor was really unhappy about this. His attitude was that a year wasn’t much time to spend away from a spouse (after all, he spent three!), and I should have at least applied for a few prestigious postdocs to maximize my chances of getting one.

Recently, my advisor emailed me just to tell me how disappointed he is in me: I have a bad attitude, I don’t always go to seminars even when he tells me I should, and that I make decisions about my future on my own, instead of in consultation with him. I responded politely (and distantly) to this.

So, here’s the question: should I do anything about all of this? I don’t work with my advisor mathematically anymore, and I’ve been much happier since we stopped. I have other projects to work on and other collaborators to work with, and I think other people in the department would be happy to give me problems or work with me on them. I don’t think my advisor is going to change in any way, and I’m the kind of person who can’t stand to be treated like an underling or told what to do. My advisor has said that he’s still happy to write me a recommendation. What things should I do? I’m hoping your answer is nothing, so that I can continue having as little contact as possible with my advisor.

Feeling Refreshed at the End of an Era

Dear FREE,

Here’s the thing. I have sympathy with some of your story but not with all of it. First I’ll tackle the negative stuff, then I’ll get to the sympathy.

If I understand correctly, you could have graduated last year but instead you’re graduating next year. So you’re staying an extra two years on the department’s dime. Doesn’t that seem a bit strange? How about if you finish and get a job in town as an actuary or something to see if non-academic work suits you? Are you preventing someone from entering the department by being there so long?

Also, you mention that you don’t go to seminars. I don’t think I always went to seminars as a young graduate student, but as I got more senior I appreciated how much language development there is in seminars – even when I didn’t understand the results I learned about how people think and talk about their work by going to seminars. I don’t think it was a waste of my time even though I ultimately left academics. I don’t think it would waste your time to go to seminars.

In other words, you sound like an entitled lazy graduate student, and I’m not so surprised your advisor is fed up with you. And I’m pretty sure your non-academic boss would be even less sympathetic to someone spending an extra two years doing not much.

Now here’s where I do my best to sound nice.

Sounds like your advisor doesn’t get you, possibly because he’s fed up with the above-mentioned issues. Like a lot of academics, he understands ambition in one narrow field, and doesn’t even relate to not wanting to be successful in this realm. That’s probably not going to change, and there’s no reason to take advice from him about how you want to live your life and the decisions you’re making for your family.

So yes, ignore him. But don’t ignore me, and I’m here to say: stop being an entitled lazy-ass.

Aunt Pythia

——

Ok I’ve never heard of Aunt Pythia, and I know this is too easy for her, but I can’t let her die.

Aunt Pythia,

If each woman I date is an independent trial, and the probability of marrying a woman I date is 0.1, how many women do I have to date before I can be at least 90% sure of getting married? (You can substitute “having sex” for “getting married” if you like.)

Anonymous

Dear Anonymous,

Aunt Pythia appreciates the sentiment, and the question.

Let’s sex up the question just a wee bit and change it from “getting married” to “having sex” as you suggested, and also raise your chances a bit to 17%, out of pure human compassion.

Let’s establish some notation: each time you date some woman we will record it either as a “G” for “got laid” or as a “D” for “dry.” So for example, after 4 women you might have a record like:

DDDGD,

which would mean you got laid with the fourth woman but with no other women.

Are we good on notation?

OK now let’s answer the question. How long do we wait for a G?

The trick is to turn it around and ask it another way: how likely is a reeeeeeally long string of D’s?

Chances of one D are good: (100-17)% = 83%.

Chances of two D’s in a row are less good: 0.83*0.83 = 0.67 = 67%.

Chances of three D’s in a row are even less good:

If you keep going you’ll notice that chances of 11 D’s in a row is 11% but chances of 12 D’s in a row are only 9%. that means that, by dating 12 women or more, your chances of getting laid are better than 90%. If you think it’s really a 10% chance every time, you’ll have to date 22 women for such odds. I’d suggest you invest in a membership on OK Cupid or some such.

Good luck!

Auntie P

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

You give me a capital requirement, I’ll give you a derivative to skirt it.

I’ve enjoyed reading Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig’s recent book, The Bankers’ New Clothes, which explains a ton of things extremely well, including:

- Differentiating between what’s “good for banks” (i.e. bankers) versus what’s good for the public, and how, through unnecessary complexity and shittons of lobbying money, the “good for bankers” case is made much more often and much more vehemently,

- that, when there’s a guaranteed backstop for a loan, the person taking out the loan has incentive to take on more risk, and

- that there are two different definitions of “big returns” depending on the context: one means big in absolute value (where -30% is bigger than -10%), the other mean big as in more positive (where -10% is bigger than -30%). Believe it or not, this ambiguity could be (at least metaphorically) taken as a cause of confusion when bankers talk to the public, in the following sense. Namely, when the expected return on an investment is, say, 3%, it makes sense for bankers to lever up their bets so they get “bigger returns” in the first sense, especially since there’s essentially no down side for them (a -30% return doesn’t affect them personally, a 30% return means a huge bonus). From the perspective of the public, they’d like to see the banks go for the “bigger return” in the second sense, so avoid the -30% scenario altogether, via restrained risk-taking.

Admati and Hellwig’s suggestion is to raise capital requirements to much higher levels than we currently have.

Here’s the thing though, and it’s really a question for you readers. How do derivatives show up on the balance sheet exactly, and what prevents me from building a derivative that avoids adding to my capital requirement but which adds risk to my portfolio?

I’ve been getting a lot of different information from people about whether this is possible, or will be possible once Basel III is implemented, but I haven’t reached anyone yet who is actually expert enough to make a definitive claim one way or the other.

It’s one thing if you’re talking about government interest rate swaps, but how do CDS’s, for example, get treated in terms of capital requirements? Is there an implicit probability of default used for accounting purposes? In that case, since such instruments are famously incredibly fat-tailed (i.e. the probability of default looks miniscule until it doesn’t), wouldn’t that encourage everyone to invest extremely heavily in instruments that don’t move their capital ratios much but take on outrageous risks? The devil’s in the detail here.

The regressive domestic complexity tax

I’ve been keeping tabs on hard it is to do my bills. I did my bills last night, and man, I’m telling you, I used all of my organizational abilities, all of my customer service experience, and quite a bit of my alpha femaleness just to get it done. Not to mention I needed more than 2 hours of time which I squeezed out by starting the bills while waiting for take-out.

By the way, I am not one of those sticklers for doing everything myself – I have an accountant, and I don’t read those forms, I just sign them and pray. But even so, removing tax issues from the conversation, the kind of expertise required to do my monthly bills is ridiculous and getting worse.

Take medical bills. I have three kids, so there’s always a few appointments pending, but it’s absolutely amazing to me how often I’m getting charged for appointments unfairly. I recently got charged for a physical for my 10-year-old son, even though I know that physicals are free thanks to ObamaCare.

So I call up my insurance company and complain, spend 15 minutes on the phone waiting, then it turns out he isn’t allowed to have more than one physical in a 12-month period which is why it was charged to me. But wait, he had one last April and one this April, what gives? Turns out last April it was on the 14th and this April it was on the 8th. So less than one year.

But surely, I object, you can’t ask for people to always be exactly 12 months apart or more! It turns out that, yes, they have a 30-day grace period for this exact reason, but for some reason it’s not automatic – it requires a person to call and complain to the insurance company to get their son’s physical covered.

Do you see what I mean? This is not actually a coincidence – insurance companies make big money from having non-automatic grace periods, because many people don’t have the time, the patience, and the pushiness to make them do it right, and that’s free money for insurance companies.

There are the (abstract) “rules” and then there’s what actually happens, and it’s a constant battle between what you know you’re paying for which you shouldn’t be and how much your time is worth. For example, if it’s less than $50 I just pay it even if it’s not reasonable. I’m sure other people have different limits.

I see this as a systemic problem. So this isn’t a diatribe against just insurance companies, because I have to jump through about 15 hoops a month like this just to get my paperwork sorted out, and they are mostly not medical issues. This is really a diatribe against complexity, and the regressive tax that complexity projects onto our society.

Rich people have people to work out their paperwork for them. People like me, we don’t have people to do this, but we have the time, skills, and patience to do it ourselves (and the money to buy takeout while we do it). There are plenty of people with no time, or who aren’t organized to have all the information they need at their fingertips when they make these calls, or are too intimidated by customer service phone lines to work it out.

And, as in the example above, there’s usually a perverse incentive for complexity to exist – people give up and pay extra because it’s not worth doing the paperwork. That means it’s always getting worse.

Bottomline: you shouldn’t need to have a college degree and customer service experience to do your bills. I’d love to see an estimate of how much more in unnecessary fees and accounting errors are paid by the poor in this country.

Payroll cards: “It costs too much to get my money” (#OWS)

If this article from yesterday’s New York Times doesn’t make you want to join Occupy, then nothing will.

It’s about how, if you work at a truly crappy job like Walmart or McDonalds, they’ll pay you with a pre-paid card that charges you for absolutely everything, including checking your balance or taking your money, and will even charge you for not using the card. Because we aren’t nickeling and diming these people enough.

The companies doing this stuff say they’re “making things convenient for the workers,” but of course they’re really paying off the employers, sometimes explicitly:

In the case of the New York City Housing Authority, it stands to receive a dollar for every employee it signs up to Citibank’s payroll cards, according to a contract reviewed by The New York Times.

Thanks for the convenience, payroll card banks!

One thing that makes me extra crazy about this article is how McDonalds uses its franchise system to keep its hands clean:

For Natalie Gunshannon, 27, another McDonald’s worker, the owners of the franchise that she worked for in Dallas, Pa., she says, refused to deposit her pay directly into her checking account at a local credit union, which lets its customers use its A.T.M.’s free. Instead, Ms. Gunshannon said, she was forced to use a payroll card issued by JPMorgan Chase. She has since quit her job at the drive-through window and is suing the franchise owners.

“I know I deserve to get fairly paid for my work,” she said.

The franchise owners, Albert and Carol Mueller, said in a statement that they comply with all employment, pay and work laws, and try to provide a positive experience for employees. McDonald’s itself, noting that it is not named in the suit, says it lets franchisees determine employment and pay policies.

I actually heard about this newish scheme against the poor when I attended the CFPB Town Hall more than a year ago and wrote about it here. Actually that’s where I heard people complain about Walmart doing this but also court-appointed child support as well.

Just to be clear, these fees are illegal in the context of credit cards, but financial regulation has not touched payroll cards yet. Yet another way that the poor are financialized, which is to say they’re physically and psychologically separated from their money. Get on this, CFPB!

Update: an excellent article about this issue was written by Sarah Jaffe a couple of weeks ago (hat tip Suresh Naidu). It ends with an awesome quote by Stephen Lerner: “No scam is too small or too big for the wizards of finance.”

When is smaller better?

It’s another whimsical Sunday morning, a perfect time to re-examine assumptions, and the one I’m working on this morning is when smaller business is actually better, where by “better” I might mean from the perspective of someone inside the business or from the perspective of the public.

I came to this question by way of two articles I’ve read recently.

Women CEO’s

First up we have this article from the Wall Street Journal, written by Sharon Hadary, which is entitled, “Why Are Women-Owned Firms Smaller Than Men-Owned Ones?” and basically wrings its hands about how self-defeating women are when it comes to owning businesses, how they never dream big enough.

Hey, that seems super irrational of women! They’re so self-limiting! Don’t they know that it’s not enough to own your own business, that you should really aspire to owning a business that is really huge?

But you know what? I’ve got a new way of looking at “irrational behavior.” Namely, assume it’s totally rational and figure out what assumptions you’ve got wrong. Let’s stop here and apply this approach. From the article:

Women start businesses to be personally challenged and to integrate work and family, and they want to stay at a size where they personally can oversee all aspects of the business.

Well that was kind of too easy. Turns out that right there, in the article, there’s a rational explanation for a so-called “irrational behavior.” Which is not to say that the writer respects that explanation, of course. Much of the rest of the article focuses how you can convince CEO women that they’re being idiots to think like that.

Of course, that mindset is not the entire story. And to the extent that women’s businesses are small against their will because of sexist behavior and being locked out of credit markets and/or big boy deals, that’s obviously bullshit.

[If I ever become a CEO, I can well imagine wanting to grow it way past the point of understanding or controlling it, because I’m all about being a big swinging dick (BSD), due to my highly robust natural testosterone levels. Because let’s face it, that’s what this is about.]

But if women don’t actually strive to be a BSD in a too-large-to-oversee Fortune 500 company because they’re happy running a smallish profitable business that allows them to see their kids, then why is that a sad story?

CEO pay

Now let’s move to a New York Times article, or really a series of articles, about CEO pay and how it’s big and only getting bigger. As my buddy Suresh explained to me, this is totally inevitable because, as the sizes of companies grow, the size of the CEO’s compensation grows.

Be nerdy with me for a second: if company A and company B merge, you now have a company that’s bigger than A or B, but you only have one CEO whereas you used to have two. So there’s that already, but it doesn’t completely explain it.

Think about the assets of this new company. To the extent that a CEO is supposed to be in charge of 1) not losing, and 2) actually growing these assets, they get some percentage of their “added value”, and that means they get twice as much credit for adding value in a company that’s twice as big.

Now I won’t go deeply into whether CEO’s actually add value – I think, at least in big-ass companies, and in the best-case scenario, CEO mostly they just ooze confidence and allow people to get work done. And I’m not saying this rule of thumb for a certain percentage of assets is reasonable, since it’s a cultural decision. But I do think just complaining about CEO pay being too big is missing the point.

Instead, I think we need to ask whether we think businesses are actually better off being bigger, and for whom. Economists go on and on about how you get economies of scale, but not if things are too big to understand, and not if the real economy of scale is devoted to politics and forming public policy – look at Monsanto for example.

Aunt Pythia: on her death bed

Dear Aunt Pythia Readers,

I’m afraid I have some bad news. Aunt Pythia has been suffering from a lack of (good) questions recently, and is running out of steam. She might well be dead within the week.

Although she’s been supplied with one new good question, as well as a few older questions she’s deemed somewhat lame (and quite a few that are downright obscene), it just doesn’t make sense for her to keep going without a week’s rest, and hopefully some shoring up of her “good questions” list.

Was it the fact that last week’s column was on Sunday? Was it because the questions have become less nerdy and more sex-related? Hard to say, but the truth is Aunt Pythia has been scraping by week to week since the get-go, and this was bound to happen at some point. She’s never yet made up a question, by the way, and considers it below her high-ish standards to do so (although she’s convinced she could make up some doozies if she tried).

Do you want her to die? Maybe you do. In that case: do nothing.

If you are, however, fond of Auntie P, then please take it upon yourself to ask a question below. Hopefully, with some TLC, she will be back on her feet next week. Otherwise, she will be permanently removed as a feature from mathbabe, which would be sad indeed.

Love,

Cathy

——

Here’s your chance to save Aunt Pythia!!

How to understand the career trajectory of Larry Summers

I heard from a Wall Street Journal recently that Summers is on the short list for the Fed Chair. I’m wondering, how often and in how many ways does this guy need to fail before people stop thinking this guy is the silver bullet?

Then I remember this article which talks about a study that connects overconfidence with social status. From the article:

“Our studies found that overconfidence helped people attain social status. People who believed they were better than others, even when they weren’t, were given a higher place in the social ladder. And the motive to attain higher social status thus spurred overconfidence,” says Anderson, the Lorraine Tyson Mitchell Chair in Leadership and Communication II at the Haas School.

Social status is the respect, prominence, and influence individuals enjoy in the eyes of others. Within work groups, for example, higher status individuals tend to be more admired, listened to, and have more sway over the group’s discussions and decisions. These “alphas” of the group have more clout and prestige than other members. Anderson says these research findings are important because they help shed light on a longstanding puzzle: why overconfidence is so common, in spite of its risks. His findings suggest that falsely believing one is better than others has profound social benefits for the individual.

Of course, Larry Summers isn’t the only example of this I can think of, but he’s a pretty perfect one.

How to be wrong

My friend Josh Vekhter sent me this blog post written by someone who calls herself celandine13 and tutors students with learning disabilities.

In the post, she reframes the concept of mistake or “being bad at something” as often stemming from some fundamental misunderstanding or poor procedure:

Once you move it to “you’re performing badly because you have the wrong fingerings,” or “you’re performing badly because you don’t understand what a limit is,” it’s no longer a vague personal failing but a causal necessity. Anyone who never understood limits will flunk calculus. It’s not you, it’s the bug.

This also applies to “lazy.” Lazy just means “you’re not meeting your obligations and I don’t know why.” If it turns out that you’ve been missing appointments because you don’t keep a calendar, then you’re not intrinsically “lazy,” you were just executing the wrong procedure. And suddenly you stop wanting to call the person “lazy” when it makes more sense to say they need organizational tools.

And she wants us to stop with the labeling and get on with the understanding of why the mistake was made and addressing that, like she does when she tutors students. She even singles out certain approaches she considers to be flawed from the start:

This is part of why I think tools like Knewton, while they can be more effective than typical classroom instruction, aren’t the whole story. The data they gather (at least so far) is statistical: how many questions did you get right, in which subjects, with what learning curve over time? That’s important. It allows them to do things that classroom teachers can’t always do, like estimate when it’s optimal to review old material to minimize forgetting. But it’s still designed on the error model. It’s not approaching the most important job of teachers, which is to figure out why you’re getting things wrong — what conceptual misunderstanding, or what bad study habit, is behind your problems. (Sometimes that can be a very hard and interesting problem. For example: one teacher over many years figured out that the grammar of Black English was causing her students to make conceptual errors in math.)

On the one hand I like the reframing: it’s always good to see knee-jerk reactions become more contemplative, and it’s always good to see people trying to help rather than trying to blame. In fact, one of my tenets of real life is that mistakes will be made, and it’s not the mistake that we should be anxious about but how we act to fix the mistake that exposes who we are as people.

I would, however, like to take issue with her anti-example in the case of Knewton, which is an online adaptive learning company. Full disclosure: I interviewed with Knewton before I took my current job, and I like the guys who work there. But, I’d add, I like them partly because of the healthy degree of skepticism they take with them to their jobs.

What the blogwriter celandine13 is pointing out, correctly, is that understanding causality is pretty awesome when you can do it. If you can figure out why someone is having trouble learning something, and if you can address that underlying issue, then fixing the consequences of that issue get a ton easier. Agreed, but I have three points to make:

- First, a non-causal data mining engine such as Knewton will also stumble upon a way to fix the underlying problem by dint of having a ton of data and noting that people who failed a calculus test, say, did much better after having limits explained to them in a certain way. This is much like the spellcheck engine of Google works by keeping track of previous spelling errors, and not by mind reading how people think about spelling wrong.

- Second, it’s not always easy to find the underlying cause of bad testing performance, even if you’re looking for it directly. I’m not saying it’s fruitless – tutors I know are incredibly good at that – but there’s room for both “causality detectives” and tons of smart data mining in this field.

- Third, it’s definitely not always easy to address the underlying cause of bad test performance. If you find out that the grammar of Black English affects students’ math test scores, what do you do about it?

Having said all that, I’d like to once more agree with the underlying message that a mistake is a first and foremost a signal rather than a reflection of someone’s internal thought processes. The more we think of mistakes as learning opportunities the faster we learn.

When is math like a microwave?

When I worked as a research mathematician, I was always flabbergasted by the speed at which other people would seem to absorb mathematical theory. I had then, and pretty much have now, this inability to believe anything that I can’t prove from first principles, or at least from stuff I already feel completely comfortable with. For me, it’s essentially mathematically unethical to use a result I can’t prove or at least understand locally.

I only recently realized that not everyone feels this way. Duh. People often just assemble accepted facts about a field quickly just to explore the landscape and get the feel for something – it makes complete sense to me now that one can do this and it doesn’t seem at all weird. And it explains what I saw happening in grad school really well too.

Most people just use stuff they “know to be true,” without having themselves gone through the proof. After all, things like Deligne’s work on Weil Conjectures or Gabber’s recent work on finiteness of etale cohomology for pseudo-excellent schemes are really fucking hard, and it’s much more efficient to take their results and use them than it is to go through all the details personally.

After all, I use a microwave every day without knowing how it works, right?

I’m not sure I know where I got the feeling that this was an ethical issue. Probably it happened without intentional thought, when I was learning what a proof is in math camp, and I’d perhaps state a result and someone would say, how do you know that? and I’d feel like an asshole unless I could prove it on the spot.

Anyway, enough about me and my confused definition of mathematical ethics – what I now realize is that, as mathematics is developed more and more, it will become increasingly difficult for a graduate student to learn enough and then prove an original result without taking things on faith more and more. The amount of mathematical development in the past 50 years is just frighteningly enormous, especially in certain fields, and it’s just crazy to imagine someone learning all this stuff in 2 or 3 years before working on a thesis problem.

What I’m saying, in other words, is that my ethical standards are almost provably unworkable in modern mathematical research. Which is not to say that, over time, a person in a given field shouldn’t eventually work out all the details to all the things they’re relying on, but it can’t be linear like I forced myself to work.

And there’s a risk, too: namely, that as people start getting used to assuming hard things work, fewer mistakes will be discovered. It’s a slippery slope.

Who stays off the data radar?

Last night’s Data Skeptics Meetup talk by Suresh Naidu was great, as I suspected it would be. I’m not going to be able to cover everything he talked about (a discussion is forming here as well) but I’ll touch on a few things related to my chosen topic for the day, namely who stays off the data radar.

In his talk Suresh discussed the history of governments tracking people with data, which more or less until recently was the history of the census. The issue of trust or lack thereof that people have in being classified and tracked has been central since the get-go, and with it the understanding by the data collectors that people respond differently to data collection when they anticipate it being used against them.

Among other examples he mentioned the efforts of the U.S. Census Bureau to stay independent (specifically, away from any kind of tax decisions) in order to be trusted but then turning around during war time and using census tracks to put Japanese into internment camps.

It made me wonder, who distrusts data collection so much that they manage to stay off the data radar?

Suresh gave quite a few examples of people who did this out of fear of persecution or what have you, and because, at least in the example of the Domesday Book, once land ownership was written down it was somehow “more official and objective” than anything else, which of course resulted in some people getting screwed out of their land.

It’s not just a historical problem, of course: it’s still true that certain populations, especially illegal immigrant populations, are afraid of how the census will be used and go undercounted. Who can say when the census might start being used to deport illegal immigrants?

As a kind of anti example, he mentioned that the census was essentially canceled in 1920 because the South knew that so many ex-slaves were moving north that their representation in government was growing weak. I say anti-example because in this case it wasn’t out of distrust, to avoid detection, but it was a savvy and political move, to remain looking large.

What about the modern version of government tracking? In this case, of course, it’s not just census data, but anything else the NSA happens to collect about us. I’m no expert (tell me if you know data on this) but I will hazard a guess on who avoids being tracked:

- Old people who don’t have computers and never have,

- Members of hacking group Anonymous who know how it works and how to bypass the system, and

- People who have worked or are now working at the NSA.

Of course there are a few other rare people that just happen to care enough about privacy to educate themselves on how to avoid being tracked. But it’s hard to do, obviously.

Let me soften the requirements a bit – instead of staying off the radar completely, who makes it really hard to find them?

If you’re talking about individuals, I’d start with this answer: politicians. In my work with Peter Darche and Lee Drutman from the Sunlight Foundation (blog post coming soon!) trying to follow money in politics, it’s amazed me time and time again how difficult it’s been to put together the political events for a given politician – events that are individually publicly recorded but are seemingly intentionally siloed so it will be extremely difficult to put together a narrative. Thanks to Peter’s recent efforts, and the Sunlight Foundations long-term efforts, we are getting to the point where we can do this, but it’s been a data munging problem from hell.

If you’re generalizing to entities and corporations, then the “making data collection hard” award should probably go to the corporations with hundreds of subsidiaries all over the world which now don’t even need to be reported on tax forms.

Funny how the very people who know the most about how data can be used are paranoid about being tracked.

Tonight: first Data Skeptics Meetup, Suresh Naidu

I’m psyched to see Suresh Naidu tonight in the first Data Skeptics Meetup. He’s talking about Political Uses and Abuses of Data and his abstract is this:

While a lot has been made of the use of technology for election campaigns, little discussion has focused on other political uses of data. From targeting dissidents and tax-evaders to organizing protests, the same datasets and analytics that let data scientists do prediction of consumer and voter behavior can also be used to forecast political opponents, mobilize likely leaders, solve collective problems and generally push people around. In this discussion, Suresh will put this in a 1000 year government data-collection perspective, and talk about how data science might be getting used in authoritarian countries, both by regimes and their opponents.

Given the recent articles highlighting this kind of stuff, I’m sure the topic will provoke a lively discussion – my favorite kind!

Unfortunately the Meetup is full but I’d love you guys to give suggestions for more speakers and/or more topics.

Ask Aunt Pythia and Cousin Lily: Sunday edition

Readers, Aunt Pythia’s confusion from traveling got her all mixed up and she forgot to distribute her pearls of wisdom yesterday on account of: she thought it was Friday. She is sincerely sorry, it won’t happen again.

Aunt Pythia is extremely grateful and pleased to announce that today she has help from a guest advice-giver, namely Cousin Lily, who specializes in sage advice for kinky people, or wanna-be kinky people.

We’ll start out with Cousin Lily’s advice, running the risk that nobody will bother to read anything else, since it’s much more interesting than anything Aunt Pythia knows about.

By the way, if you don’t know what you’re in for, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia. Most importantly,

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia/ Cousin Lily,

Since I promised: here’s the follow-up question(s). My partner and I have a great sex life, but perhaps you have some advice on how to make it better. Her kink is that she’s submissive. I’m pretty vanilla in this area- it’s mostly obliviousness on my part. It had never occurred to me that sex and power were anything but orthogonal, to be nerdy about it.

I have two things I’m puzzling over. First, I’m used to asking someone what they like in bed – nobody’s a mind reader, after all. However, if I ask, then I’m not really being dominant. Any way around this?

Second, I know the bedroom isn’t real life, but I have a real problem with anything that even has undertones of treating her badly (no play humiliation etc). I’ve figured out some activities that we both enjoy (e.g. telling her to make me a cake while naked, wrestling). I think she would like it if I pushed the boundaries a bit more. Any ideas on how to disassociate slightly more the bedroom from real life in my mind?

OK I’ll Bite

——

Dear OK,

Please read “The Bottoming Book” by Hardy and Easton, stat. I highly recommend reading it together and letting it start some conversations between you. This book will help you understand the things that might be motivating your submissive partner, ways to explore Dominant/submissive (D/s) play safely (both physically and emotionally), and techniques for handling the times that things don’t go perfectly.

It is really common for “vanilla” partners to feel uncomfortable about their submissive partner’s desires regarding power and potentially things like pain and/or humiliation. But once you understand what motivates your submissive’s kink and what she is hoping to get from the experience, you will feel much more at ease about providing that. Not every sub is submissive in the same way or for the same reasons — understanding your sub’s kink (and finding out whether she understands it herself) will make the whole experience much more accessible. This better understanding will also allow you to view the exchange as your providing pleasure of a specific kind, rather than pain/abuse/etc.

NO MIND READING should be expected by either party. That is a recipe for disaster on both sides. Talk through in detail what each of you expects and wants, and do it long before you get into bed (although this discussion doesn’t have to be clinical — it can totally be sexy, just do it at the bar and not in the bedroom so that each person has time to reflect and react). This can be a tool to ease anxiety, but it can also be a tool to build anticipation: in other words, a total turn-on. Asking for input doesn’t mean you’re not being dominant; ask your sub to tell you the range of things that she would find sexy, and then YOU CHOOSE which of those things happen, or in what order, or when (depending on what you negotiate together). That is totally dom.

Take baby steps. It doesn’t have to be perfect the first time, or any time. Don’t go farther than you’re comfortable with, and trade feedback after each encounter. You should also develop techniques for getting feedback during your encounters. You can do this while remaining dominant: “How does that feel?” “I don’t like it, Sir.” “I didn’t ask if you liked it.” [but then you back off anyway, maybe after just one more prolonged second]. Just communicate, communicate, communicate. And read the book.

Finally, try to stop thinking about this as “[disassociating] the bedroom from real life”. We humans are complex creatures with multiple moods and identities. You don’t share the same side of yourself with your college friends that you do with your grandparents (hopefully), but that doesn’t make one experience more a part of “real life” than the other. Similarly, power dynamics in the bedroom are simply a way of exploring different parts of ourselves, and to fully explore your partner and all the levels of complexity she has to offer as a full human being is the most intimate, wonderful thing you could do — why would you ever want to disassociate that from the rest of your lives together? Embrace that part of her, and embrace whatever part of yourself engages with her inner submissive. I promise, it will add a new and rich dimension to your “real life” relationship if you let it.

For further reading and more specific guidance about exploring dominance, check out “The Topping Book” (also by Hardy and Easton) or “The Loving Dominant” (specific to male, heterosexual doms). Have fun!

Cousin Lily

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I want to preface my question by saying that I’ve read your posts about Big Data as Big Brother and NSA Mathematicians and I definitely appreciate that there are a lot of very serious, very heavy issues involved in your discussions.

However, reading them has also made me worried about a potentially more nontrivial issue: should I be concerned that the porn I watch shows up in my browser history? The stuff I watch is all firmly mainstream, but you’ve said before that a person’s google search histories (given that they’re logged into gmail) are basically stored forever and could potentially be bought by agencies/companies looking to vet prospective employees.

And given that I’m a grad student who’s in a long distance relationship, my internet history would read to others like: math, math, math, porn, porn, math… Which is clearly not an impression I want to give of myself. Am I being needlessly paranoid?

Paranoia Generally Leads (2, Craziness)

Dear PGL(2,C),

That might be the nerdiest abbreviation I’ve ever seen. Hear hear! I would have answered your question simply based on that alone, but I actually want to address your very good question as well.

Here’s the thing: you have to understand that everyone watches porn. Or, if not everyone, than almost everyone. So yes, although your electronic footprint is going to have an enormous amount of smut attached to it, you’d only need to worry if your smut level is somehow much larger than the average guy’s smut level. And honestly, it doesn’t sound that way at all, given that 4 out of 6 example clicks above were mathy.

In other words, be nerdy with me for a moment and look at an extreme edge case where your browser history is absolutely transparent to anyone, including future employers, but so is everyone else’s. Then it’s a game of relativity: are you going to stand out as a huge perv? Not a chance. If, over time, people more and more start getting smart about hiding their smut, say by using a separate browser or going into incognito windows on Chrome, and it becomes the norm not to have a bunch of porn in your history, then not doing so will make you stand out. But honestly we’re not there yet.

And also, we’re not there yet for that edge case where your history is completely known. The truth is most employers that you’d work for as a mathematician don’t even pry into this kind of thing – it’s mostly a problem for shitty jobs at Walmart, where they’re trying to decide if you’re going to be a good robot or if you’re going to cause trouble, or if you work for the NSA or something.

So don’t fret! And good luck. What with a long distance relationship during grad school, you’re going to need it.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’d be a bit of a wet blanket to state Lybridos is ineffective, plus there’s a lot of money at stake. So I’m skeptical about the supporting research (e.g. a woman’s sex drive in a relationship plummets in a relationship, except maybe if they’re with a whaler). What are the warning signa as to whether such research is dodgy?

More Sex Research Please

Dear MSRP,

First of all, “MSRP” stands for “manufacturer’s suggested retail price” and it doesn’t do much for me. Please take copious notes from PGL(2, C) above.

Second, when I first read your question, I honestly wondered if it was written in English. I mean, there are references to all sorts of things I’ve never heard about – Lybridos? Great sex with whalers? – and then the actual question asks me to comment on research that’s unnamed. I’m sure you can do better! Just throw in a few url’s and we’d be good!

I managed to figure out what Lybridos is, since googling that isn’t so hard, but for the whaling comment I got nothing, and in the end I can’t figure out which research is or is not dodgy. So please do write back with references, especially for the sex-with-whalers comment, which especially intrigues me, thanks.

I did want to address the inherent topic here, though, namely of women’s sex drive and getting pills for it. Namely, I’m all for it. In fact I’d like to read profiles in the New York Times about a gaggle of 50-year-old women, preferably in the same knitting circle, who started taking pills to get their sex life kick-started, and it worked, and now their husbands are too exhausted to keep up so they (the husbands) hired extra men to come in and assist.

Why? Because the narrative on men and women’s sexuality is totally distorted and always paints the picture of women avoiding sex and men wanting and needing it. I honestly think this myth is perpetuated for the sake of men’s egos. Or, to be generous, it’s a survivorship bias problem, since married couples go to the doctor and complain when women lose interest but they don’t do the same thing when men do. Judging from my girlfriends, though, there’s no national crisis of women not being interested in sex. Of course there’s also a bias in the sample of women who are my girlfriends, but I must expect the truth to be somewhere in the middle.

I look forward to your more precise question next time!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

The politics of data mining

At first glance, data miners inside governments, start-ups, corporations, and political campaigns are all doing basically the same thing. They’ll all need great engineering infrastructure, good clean data, a working knowledge of statistical techniques and enough domain knowledge to get things done.

We’ve seen recent articles that are evidence for this statement: Facebook data people move to the NSA or other government agencies easily, and Obama’s political campaign data miners have launched a new data mining start-up. I am a data miner myself, and I could honestly work at any of those places – my skills would translate, if not my personality.

I do think there are differences, though, and here I’m not talking about ethics or trust issues, I’m talking about pure politics[1].

Namely, the world of data mining is divided into two broad categories: people who want to cause things to happen and people who want to prevent things from happening.

I know that sounds incredibly vague, so let me give some examples.

In start-ups, irrespective of what you’re actually doing (what you’re actually doing is probably incredibly banal, like getting people to click on ads), you feel like you’re the first person ever to do it, at least on this scale, or at least with this dataset, and that makes it technically challenging and exciting.

Or, even if you’re not the first, at least what you’re creating or building is state-of-the-art and is going to be used to “disrupt” or destroy lagging competition. You feel like a motherfucker, and it feels great[2]!

The same thing can be said for Obama’s political data miners: if you read this article, you’ll know they felt like they’d invented a new field of data mining, and a cult along with it, and it felt great! And although it’s probably not true that they did something all that impressive technically, in any case they did a great job of applying known techniques to a different data set, and they got lots of people to allow access to their private information based on their trust of Obama, and they mined the fuck out of it to persuade people to go out and vote and to go out and vote for Obama.

Now let’s talk about corporations. I’ve worked in enough companies to know that “covering your ass” is a real thing, and can overwhelm a given company’s other goals. And the larger the company, the more the fear sets in and the more time is spent covering one’s ass and less time is spent inventing and staying state-of-the-art. If you’ve ever worked in a place where it takes months just to integrate two different versions of SalesForce you know what I mean.

Those corporate people have data miners too, and in the best case they are somewhat protected from the conservative, risk averse, cover-your-ass atmosphere, but mostly they’re not. So if you work for a pharmaceutical company, you might spend your time figuring out how to draw up the numbers to make them look good for the CEO so he doesn’t get axed.

In other words, you spend your time preventing something from happening rather than causing something to happen.

Finally, let’s talk about government data miners. If there’s one thing I learned when I went to the State Department Tech@State “Moneyball Diplomacy” conference a few weeks back, it’s that they are the most conservative of all. They spend their time worrying about a terrorist attack and how to prevent it. It’s all about preventing bad things from happening, and that makes for an atmosphere where causing good things to happen takes a rear seat.

I’m not saying anything really new here; I think this stuff is pretty uncontroversial. Maybe people would quibble over when a start-up becomes a corporation (my answer: mostly they never do, but certainly by the time of an IPO they’ve already done it). Also, of course, there are ass-coverers in start-ups and there are risk-takers in corporation and maybe even in government, but they don’t dominate.

If you think through things in this light, it makes sense that Obama’s data miners didn’t want to stay in government and decided to go work on advertising stuff. And although they might have enough clout and buzz to get hired by a big corporation, I think they’ll find it pretty frustrating to be dealing with the cover-my-ass types that will hire them. It also makes sense that Facebook, which spends its time making sure no other social network grows enough to compete with it, works so well with the NSA.

1. If you want to talk ethics, though, join me on Monday at Suresh Naidu’s Data Skeptics Meetup where he’ll be talking about Political Uses and Abuses of Data.

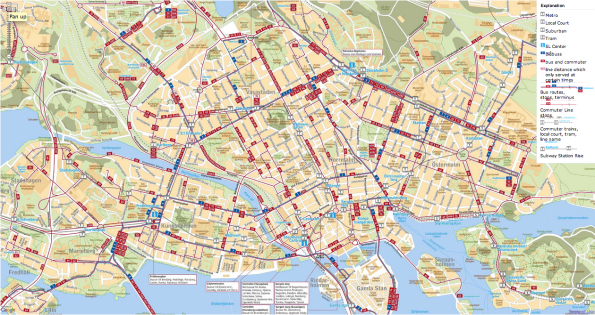

I am the bus queen of Stockholm

Do you know what I really love? Maps. All kinds of maps. If you come to my house, you won’t see standard artwork on the walls, but instead you’ll see: knitting, hanging musical instruments, and maps.

In my kitchen I have a huge map of New York City, which I purchased from Staples for $99 when I moved to the city in 2005, as well as a large subway map, and more recently a bike map. I’ve got New York covered.

And whenever I go to a new city, I enjoy staring at a good map for a few hours, figuring out how to get from place to place by walking or taking a subway or bus. I’m never interested in driving, because I don’t own a car nor do I enjoy riding cabs.

Here’s the map of Stockholm I’ve been staring at for the past few weeks:

It’s a bus map of Stockholm. We smartly bought 7-day passes our first day here, and since kids 12 and younger are free and 13-year-olds are subsidized, this has been a huge win. We’ve been whizzing around the city daily. Buses are really the way to go.

Now, if you’re from certain American cities, you might disagree. You might think buses are slow and painful. But not here! They come every few minutes, more often than subways, and they seem to magically glide from stop to stop (the stops are more infrequent here than in New York, one reason they’re much more efficient). It’s like an unguided tour every time you go anywhere, my favorite kind!

I’ve gotten so excited about (and so proficient at) getting from point A to point B on the bus system, I’ve taken to calling myself the “Bus Queen (of Stockholm),” with practically no self-consciousness whatsoever, even though everyone here speaks perfect English and can hear me brag incessantly to my kids (to their credit, the older ones roll their eyes appropriately).

My four-year-old, who thinks everything I say is true, has asked his older brother to build a Minecraft World called “Bus Queen” in honor of my title, which he has done. As I understand it, the Minecraft villagers internal to Bus Queen World are just about done erecting a Town Hall in my honor. I go!!

One of the great boons of the bus system here in Stockholm is that, unlike Citibikes in New York, you can take a sick and drugged-up 4-year-old on the bus and go places you otherwise wouldn’t be able to walk to. This has been pretty convenient for all of us, believe you me.

But here’s the sad part: there’s a bus strike today in Stockholm and a few other Swedish cities. The bus queen, sadly, may have no throne on which to sit on this, her last day of reign (because we’re coming home tomorrow).

This strike makes me realize something about workers’ conditions in the U.S. which I haven’t thought about since the 2005 New York transit workers’ strike. Namely, Americans don’t have a lot of sympathy for striking workers compared to Europeans. Partly this is because we Americans prize convenience over other people’s conditions (“Can the bus drivers please return to work until after I’ve left Stockholm? The Bus Queen beseeches you!”), and partly this is due, I’m guessing, to the fact that there’s so much income disparity in the U.S. that there’s always some other group of workers worse off than the people striking.

Why Education Isn’t Like Sports

This is a guest post by Eugene Stern.

Sometimes you learn just as much from a bad analogy as from a good one. At least you learn what people are thinking.

The other day I read this response to this NYT article. The original article asked whether the Common Core-based school reforms now being put in place in most states are really a good idea. The blog post criticized the article for failing to break out four separate elements of the reforms: standards (the Core), curriculum (what’s actually taught), assessment (testing), and accountability (evaluating how kids and educators did). If you have an issue with the reforms, you’re supposed to say exactly which aspect you have an issue with.

But then, at the end of the blog post, we get this:

A track and field metaphor might help: The standard is the bar that students must jump over to be competitive. The curriculum is the training program coaches use to help students get over the bar. The assessment is the track meet where we find out how high everyone can jump. And the accountability system is what follows after its all over and we want to figure out what went right, what went wrong, and what it will take to help kids jump higher.

Really?

In track, jumping over the bar is the entire point. You’re successful if you clear the bar, you’ve failed if you don’t. There are no other goals in play. So the standard, the curriculum, and the assessment might be nominally different, but they’re completely interdependent. The standard is defined in terms of the assessment, and the only curriculum that makes sense is training for the assessment.

Education has a lot more to it. The Common Core is a standard covering two academic dimensions: math and English/language arts/literacy. But we also want our kids learning science, and history, and music, and foreign languages, and technology, as well as developing along non-academic dimensions: physically, socially, morally, etc. (If a school graduated a bunch of high academic achievers that couldn’t function in society, or all ended up in jail for insider trading, we probably wouldn’t call that school successful.)

In Cathy’s terminology from this blog post, the Common Core is a proxy for the sum total of what we care about, or even just for the academic component of what we care about.

Then there’s a second level of proxying when we go from the standard to the assessment. The Common Core requirements are written to require general understanding (for example: kindergarteners should understand the relationship between numbers and quantities and connect counting to cardinality). A test that tries to measure that understanding can only proxy it imperfectly, in terms of a few specific questions.

Think that’s obvious? Great! But hang on just a minute.

The real trouble with the sports analogy comes when we get to the accountability step and forget all the proxying we did. “After it’s all over and we want to figure out what went right (and) what went wrong,” we measure right and wrong in terms of the assessment (the test). In sports, where the whole point is to do well on the assessment, it may make sense to change coaches if the team isn’t winning. But when we deny tenure to or fire teachers whose students didn’t do well enough on standardized tests (already in place in New York, now proposed for New Jersey as well), we’re treating the test as the whole point, rather than a proxy of a proxy. That incentivizes schools to narrow the curriculum to what’s included in the standard, and to teach to the test.

We may think it’s obvious that sports and education are different, but the decisions we’re making as a society don’t actually distinguish them.

Swedish vacation

Dear Readers,

I hope you know I miss you as much as you miss me.

For the past few days I’ve been in sunny friendly Stockholm. In my defense, I’m suffering badly from jetlag. Since I left New York last Thursday I’ve had one good night’s sleep and about 3 naps. My youngest son has an ear infection which is making him miserable, and so I’m kind of stuck at home with the kids while Johan temporarily works at the nearby KTH math department.

But honestly, traveling, even with kids, and even with jetlag, is no excuse to take off so much time from blogging. I didn’t even announce beforehand I’d be going away because I’d planned to blog every day anyway.

Here’s my confession: the real reason I haven’t blogged is because I’ve fallen into a Northern European funk.

Let me explain. Being here in gorgeous sunny Stockholm is kind of like lying back in a cloud. It’s so soft, so bereft of the natural tension and energy of New York, that you just feel like knitting all day and drinking coffee. And then, when you can’t sleep and it’s still light out at midnight, you feel like knitting some more. I’m almost done with a sweater I didn’t even have the yarn for until Saturday.

Not that I’m complaining, exactly – the Swedish people I’ve met are incredibly nice. So nice in fact that it’s almost become a personal challenge I’ve given myself to see what makes them tick.

For example, they don’t seem to value their time like we do in New York. There are lines for everything here, and although I can appreciate an organized line myself now and again, this is a different matter – it’s kind of a national pasttime.

For example, to gain entrance to an amusement park yesterday, my sons and I stood in line for 30 minutes. Then we tried to get onto some rides, but it turns out you have to stand in a second, separate line inside the park for another 30 minutes to buy tickets for the rides. Woohoo! Another line! I seemed to be the only person in line who was crazed by the system.

When I finally got to the ticket window and confronted the ticket seller in my polite-but-impatient New York way, he explained that it was the same system that the park had opened with back in 1830 or something. Naturally I felt incredibly honored to be taking part in such a hallowed ritual, as I explained to him.

Let’s talk Star Trek comparisons for a moment. There’s a spectrum of represented civilizations, from oppressed penal colonies on the one hand, where everyone’s dirty and wearing rags, but even so there’s always a shockingly articulate and thoughtful representatives, to ideal utopias on the other, where everyone’s incredibly fit and beautiful, bounding about without a care in the world (although often also hiding a dark secret – perhaps they sap the life energy from a slave race hidden underground?).

I’d have to put Stockholm and its ridiculously gorgeous citizenry firmly on the utopia end of the Star Trek spectrum, with a few inconsistent details, namely that, unlike in Star Trek, they still exchange money (although not for their high quality medical care) and that, despite their utopian existence, they don’t seem to have the requisite dirty secret. Of course I say that while temporarily residing in the Upper West Side equivalent of Stockholm, and not as an unemployed immigrant youth in the suburbs.

In any case, I’m coming back in a few days, and I’m looking forward to the friction, the hot grimy subway cars, and of course the beloved controversy over citibikes. Aunt Pythia, who missed her column this past Saturday, is also chomping at the bit (with some help from guest advice columnist Cousin Lily!), so stay tuned for that too.

XOXOX,

Cathy

Guest post, The Vortex: A Cookie Swapping Game for Anti-Surveillance

This is a guest post by Rachel Law, a conceptual artist, designer and programmer living in Brooklyn, New York. She recently graduated from Parsons MFA Design&Technology. Her practice is centered around social myths and how technology facilitates the creation of new communities. Currently she is writing a book with McKenzie Wark called W.A.N.T, about new ways of analyzing networks and debunking ‘mapping’.

Let’s start with a timely question. How would you like to be able to change how you are identified by online networks? We’ll talk more about how you’re currently identified below, but for now just imagine having control over that process for once – how would that feel? Vortex is something I’ve invented that will try to make that happen.

Namely, Vortex is a data management game that allows players to swap cookies, change IPs and disguise their locations. Through play, individuals experience how their browser changes in real time when different cookies are equipped. Vortex is a proof of concept that illustrates how network collisions in gameplay expose contours of a network determined by consumer behavior.

What happens when users are allowed to swap cookies?

These cookies, placed by marketers to track behavioral patterns, are stored on our personal devices from mobile phones to laptops to tablets, as a symbolic and data-driven signifier of who we are. In other words, to the eyes of the database, the cookies are us. They are our identities, controlling the way we use, browse and experience the web. Depending on cookie type, they might follow us across multiple websites, save entire histories about how we navigate and look at things and pass this information to companies while still living inside our devices.

If we have the ability to swap cookies, the debate on privacy shifts from relying on corporations to follow regulations to empowering users by giving them the opportunity to manage how they want to be perceived by the network.

What are cookies?

The corporate technological ability to track customers and piece together entire personal histories is a recent development. While there are several ways of doing so, the most common and prevalent method is with HTTP cookies. Invented in 1994 by a computer programmer, Lou Montulli, HTTP cookies were originally created with the shopping cart system as a way for the computer to store the current state of the session, i.e. how many items existed in the cart without overloading the company’s server. These session histories were saved inside each user’s computer or individual device, where companies accessed and updated consumer history constantly as a form of ‘internet history’. Information such as where you clicked, how to you clicked, what you clicked first, your general purchasing history and preferences were all saved in your browsing history and accessed by companies through cookies.

Cookies were originally implemented to the general public without their knowledge until the Financial Times published an article about how they were made and utilized on websites without user knowledge on February 12th, 1996 . This revelation led to a public outcry over privacy issues, especially since data was being gathered without the knowledge or consent of users. In addition, corporations had access to information stored on personal computers as the cookie sessions were stored on your computer and not their servers.

At the center of the debate was the issue on third-party cookies, also known as “persistent” or “tracking” cookies. When you are browsing a webpage, there may be components on the page that are hosted on the same server, but different domain. These external objects then pass cookies to you if you click an image, link or article. They are then used by advertising and media mining corporations to track users across multiple sites to garner more knowledge about the users browsing patterns to create more specific and targeted advertising.

In August 2013, Wall Street Journal ran an article on how Mac users were being unfairly targeted by travel site Orbitz with advertisements that were 13% more expensive than PC users. New York Times followed it up with a similar article in November 2012 about how the data collected and re-sold to advertisers. These advertisers would analyze users buying habits to create micro-categories where the personal experiences were tailored to maximize potential profits.

What does that mean for us?

The current state of today’s internet is no longer the same as the carefree 90s of ‘internet democracy’ and utopian ‘cyberspace’. Mediamining exploits invasive technologies such as IP tracking, geolocating and cookies to create specific advertisements targeted to individuals. Browsing is now determined by your consumer profile what you see, hear and the feeds you receive are tailored from your friends’ lists, emails, online purchases etc. The ‘Internet’ does not exist. Instead, it is many overlapping filter bubbles which selectively curate us into data objects to be consumed and purchased by advertisers.

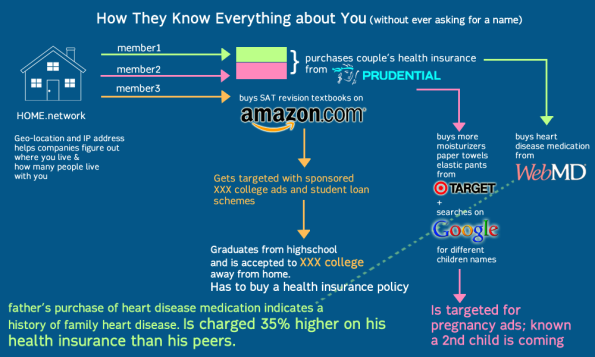

This information, though anonymous, is built up over time and used to track and trace an individual’s history – sometimes spanning an entire lifetime. Who you are, and your real name is irrelevant in the overall scale of collected data, depersonalizing and dehumanizing you into nothing but a list of numbers on a spreadsheet.

The superstore Target, provides a useful case study for data profiling in its use of statisticians on their marketing teams. In 2002, Target realized that when a couple is expecting a child, the way they shop and purchase products changes. But they needed a tool to be able to see and take advantage of the pattern. As such, they asked mathematicians to come up with algorithms to identify behavioral patterns that would indicate a newly expectant mother and push direct marketing materials their way. In a public relations fiasco, Target had sent maternity and infant care advertisements to a household, inadvertedly revealing that their teenage daughter was pregnant before she told her parents .

This build-up of information creates a ‘database of ruin’, enough information that marketers and advertisers know more about your life and predictive patterns than any single entity. Databases that can predict whether you’re expecting, or when you’ve moved, or what stage of your life or income level you’re at… information that you have no control over where it goes to, who is reading it or how it is being used. More importantly, these databases have collected enough information that they know secrets such as family history of illness, criminal or drug records or other private information that could potentially cause harm upon the individual data point if released – without ever needing to know his or her name.

What happens now is two terrifying possibilities:

- Corporate databases with information about you, your family and friends that you have zero control over, including sensitive information such as health, criminal/drug records etc. that are bought and re-sold to other companies for profit maximization.

- New forms of discrimination where your buying/consumer habits determine which level of internet you can access, or what kind of internet you can experience. This discrimination is so insidious because it happens on a user account level which you cannot see unless you have access to other people’s accounts.

Here’s a visual describing this process:

What can Vortex do, and where can I download a copy?

As Vortex lives on the browser, it can manage both pseudo-identities (invented) as well as ‘real’ identities shared with you by other users. These identity profiles are created through mining websites for cookies, swapping them with friends as well as arranging and re-arranging them to create new experiences. By swapping identities, you are essentially ‘disguised’ as someone else – the network or website will not be able to recognize you. The idea is that being completely anonymous is difficult, but being someone else and hiding with misinformation is easy.

This does not mean a death knell for online shopping or e-commerce industries. For instance, if a user decides to go shoe-shopping for summer, he/she could equip their browser with the cookies most associated and aligned with shopping, shoes and summer. Targeted advertising becomes a targeted choice for both advertisers and users. Advertisers will not have to worry about misinterpreting or mis-targeting inappropriate advertisements i.e. showing tampon advertisements to a boyfriend who happened to borrow his girlfriend’s laptop; and at the same time users can choose what kind of advertisements they want to see. (i.e. Summer is coming, maybe it’s time to load up all those cookies linked to shoes and summer and beaches and see what websites have to offer; or disable cookies it completely if you hate summer apparel.)

Currently the game is a working prototype/demo. The code is licensed under creative commons and will be available on GitHub by the end of summer. I am trying to get funding to make it free, safe & easy to use; but right now I’m broke from grad school and a proper back-end to be built for creating accounts that is safe and cannot be intercepted. If you have any questions on technical specs or interest in collaborating to make it happen – particularly looking for people versed in python/mongodb, please email me: Rachel@milkred.net.

Crash the pick-up party with me?

I’m not sure my friend Jason Windawi will appreciate the credit, but he pointed me to this Meetup yesterday called “MEN THAT DATE HOT WOMEN”, which I have conveniently screen-shotted for y’all:

I’m not sure where to start with deconstructing this pick-up-artist wannabe clan, but let’s just START WITH THE ALL CAPS. Who does that? Update: turns out THE NAVY DOES THAT.

I’m thinking of crashing this Meetup with a posse of sufficiently ridiculous and hilarious friends.

First the good news: I can easily imagine what kind of person I’d love to attract for this action (namely, anyone who thinks this is ludicrous, in a fun way, and wants to join me) but, and here’s the other good news, I’m having trouble figuring out the perfect thing to do once we get there. Let’s think.

First thought: line dance with boas, singing “I will survive.” Maybe not that exactly, but something to intentionally and directly contrast the oppressively normative nature of a bunch of straight guys looking for “hot” women using a formulaic approach involving magic tricks. Bonus points, obviously, for ill-fitting cocktail dresses that emphasize jiggling flesh.

In other words, let’s take a page out of this book, one of my all-time favorite Occupy actions:

Other ideas welcome!

Where’s the outrage over private snooping?

There’s been a tremendous amount of hubbub recently surrounding the data collection data mining that the NSA has been discovered to be doing.

For me what’s weird is that so many people are up in arms about what our government knows about us but not, seemingly, about what private companies know about us.

I’m not suggesting that we should be sanguine about the NSA program – it’s outrageous, and it’s outrageous that we didn’t know about it. I’m glad it’s come out into the open and I’m glad it’s spawned an immediate and public debate about the citizen’s rights to privacy. I just wish that debate extended to privacy in general, and not just the right to be anonymous with respect to the government.

What gets to me are the countless articles that make a big deal of Facebook or Google sharing private information directly with the government, while never mentioning that Acxiom buys and sells from Facebook on a daily basis much more specific and potentially damning information about people (most people in this country) than the metadata that the government purports to have.

Of course, we really don’t have any idea what the government has or doesn’t have. Let’s assume they are also an Acxiom customer, for that matter, which stands to reason.