Archive

Another death spiral of modeling: e-scores

Yesterday my friend and fellow Occupier Suresh sent me this article from the New York Times.

It’s something I knew was already happening somewhere, but I didn’t know the perpetrators would be quite so proud of themselves as they are; on the other hand I’m also not surprised, because people making good money on mathematical models rarely take the time to consider the ramifications of those models. At least that’s been my experience.

So what have these guys created? It’s basically a modern internet version of a credit score, without all the burdensome regulation that comes with it. Namely, they collect all kinds of information about people on the web, anything they can get their hands on, which includes personal information like physical and web addresses, phone number, google searches, purchases, and clicks of each person, and from that they create a so-called “e-score” which evaluates how much you are worth to a given advertiser or credit card company or mortgage company or insurance company.

Some important issues I want to bring to your attention:

- Credit scores are regulated, and in particular the disallow the use of racial information, whereas these e-scores are completely unregulated and can use whatever information they can gather (which is a lot). Not that credit score models are open source: they aren’t, so we don’t know if they are using variables correlated to race (like zip code). But still, there is some effort to protect people from outrageous and unfair profiling. I never though I’d be thinking of credit scoring companies as the good guys, but it is what it is.

- These e-scores are only going for max pay-out, not default risk. So, for the sake of a credit card company, the ideal customer is someone who pays the minimum balance month after month, never finishing off the balance. That person would have a higher e-score than someone who pays off their balance every month, although presumably that person would have a lower credit score, since they are living more on the edge of insolvency.

- Not that I need to mention this, but this is the ultimate in predatory modeling: every person is scored based on their ability to make money for the advertiser/ insurance company in question, based on any kind of ferreted-out information available. It’s really time for everyone to have two accounts, one for normal use, including filling out applications for mortgages and credit cards and buying things, and the second for sensitive google searches on medical problems and such.

- Finally, and I’m happy to see that the New York Times article noticed this and called it out, this is the perfect setup for the death spiral of modeling that I’ve mentioned before: people considered low value will be funneled away from good deals, which will give them bad deals, which will put them into an even tighter pinch with money because they’re being nickeled and timed and paying high interest rates, which will make them even lower value.

- A model like this is hugely scalable and valuable for a given advertiser.

- Therefore, this model can seriously contribute to our problem of increasing inequality.

- How can we resist this? It’s time for some rules on who owns personal information.

Looterism

My friend Nik recently sent me a PandoDaily article written by Francisco Dao entitled Looterism: The Cancerous Ethos That Is Gutting America.

He defines looterism as the “deification of pure greed” and says:

The danger of looterism, of focusing only on maximizing self interest above the importance of creating value, is that it incentivizes the extraction of wealth without regard to the creation or replenishment of the value building mechanism.

I like the term, I think I’ll use it. And it made me think of this recent Bloomberg article about private equity and hedge funds getting into the public schools space. From the article:

Indeed, investors of all stripes are beginning to sense big profit potential in public education.

The K-12 market is tantalizingly huge: The U.S. spends more than $500 billion a year to educate kids from ages five through 18. The entire education sector, including college and mid-career training, represents nearly 9 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, more than the energy or technology sectors.

Traditionally, public education has been a tough market for private firms to break into — fraught with politics, tangled in bureaucracy and fragmented into tens of thousands of individual schools and school districts from coast to coast.

Now investors are signaling optimism that a golden moment has arrived. They’re pouring private equity and venture capital into scores of companies that aim to profit by taking over broad swaths of public education.

The conference last week at the University Club, billed as a how-to on “private equity investing in for-profit education companies,” drew a full house of about 100.

[I think I know why that golden moment arrived, by the way. The obsession with test scores, a direct result of No Child Left Behind, is both pseudo-quantitative (by which I mean it is quantitative but is only measuring certain critical things and entirely misses other critical things) and has broken the backs of unions. Hedge funds and PE firms love quantitative things, and they don’t really care if they numbers are meaningful if they can meaningfully profit.]

Their immediate goal is out-sourcing: they want to create the Blackwater (now Academi) of education, but with cute names like Schoology and DreamBox.

Lest you worry that their focus will be on the wrong things, they point out that if you make kids drill math through DreamBox “heavily” for 16 weeks, they score 2.3 points higher in a standardized test, although they didn’t say if that was out of 800 or 20. Never mind that “heavily” also isn’t defined, but it seems safe to say from context that it’s at least 2 hours a day. So if you do that for 16 weeks, those 2.3 points better be pretty meaningful.

So either the private equity guys and hedge funders have the whole child in mind here, or it’s maybe looterism. I’m thinking looterism.

High frequency trading: does it hurt the little guy?

I’ve already written about high frequency trading here, and I came out in favor of a transaction tax to slow that shit down a little bit. After all, the argument that liquidity is good so more liquidity is better only holds to a point – we don’t need infinite liquidity. It makes sense to actually have a small barrier to trade – you actually have to think it’s a good idea one way or another, otherwise you have no incentive not to do something dumb.

And as we’ve seen recently with Knight Capital, dumb things definitely are likely to happen.

It’s been interesting to see the media reaction. On the one hand, the Room for Debate over at the New York Times has a bunch of people discussing high frequency trading (HFT), and the most pro-HFT guy essentially says that the SEC should keep up technology-wise with these guys, and everything will be ok. That’s called living in a fantasy world.

More interesting to me was Felix Salmon’s post yesterday, where he rightly complained that, all too often, journalists dumb down and simplify reporting on these things, and then he proceeds to dumb down and simplify reporting on this thing.

Specifically, he complains that no “little guys” were hurt in Knight’s crash, even though the press is always looking for the little guy that gets hurt. [Side note: he also complains about the LIBOR manipulation not hurting municipalities, which is false, it did hurt them. He needs to understand that better before he dismisses it.]

But, if I’m not dreaming, Fidelity was one of the large customers of Knight that’s pulled out, and if I’m not unconscious, Fidelity manages quite a few of my many 401K accounts, as well as a huge proportion of the 401K accounts in this country. So it’s quite possible that my retirement money was part of that massive screw-up which is now owned by Goldman Sachs, not that I’ve been notified by Fidelity of any harm (but that’s another post).

As for small investors vs. little guys, there’s a difference. If you have enough money that you’re investing it through brokers, I personally don’t count you as small, even if you appear small to Goldman Sachs. So I’m not interested in whether the small investor was all that harmed by Knight’s meltdown, but I’m pretty sure the small investor was scared away by it.

But looking at the larger picture, I’d definitely say this is an indication of the outrageous complexity of the financial system, which most definitely is hurting the little guy, i.e. the taxpayer. This complexity is why we have the government guarantee in place, the Too-Big-and-Too-Complex-To-Fail banks and markets, and the little guy on the hook when things melt down. Moreover, there’s a direct line from that whole mess to the destruction of unions and pension programs, even if people don’t want to draw it.

So if you want to be myopic you can say that this was one firm, making one major blunder, and it’s self-contained and that firm is failing just like it should. But if you take a step back you see they were doing this as part of a larger culture of competition for speed and technology that they are so focused on, they threw risk to the wind in order to achieve a tiny edge over NYSE.

That laser focus on having a tiny edge really is the underlying story, and will continue to be, at the expense of risk, at the expense of our retirement funds trading for us, without regard to unnecessary complexity or, yes, the little guy, until our politicians and regulators grow some balls and put an end to it.

I love whistleblowers

There’s something people don’t like about whistleblowers. I really don’t get it, but I know it’s true (I’m looking at you, Obama).

In particular, I hear all the time that you’re giving up on your career if you’re a whistleblower, that nobody would ever want to hire you again. But if I’m running a company, which I presumably want have run well, without corruption, and be successful, then I’m totally fine with whistleblowers! They will tell me truth and expose fraud. To say out loud that I don’t want to hire someone like that is basically admitting I’m okay with fraud, no?

I’m really missing something, and if you have an explanation I’d love to hear it.

In the meantime, though, I’ll say this: the web is great for anonymous whistleblowing (if anyone pays attention and follows up). Science Fraud is a great one that tells about scientific publishing fraud in the life sciences – see the “About” page of Science Fraud for more color. See also Retraction Watch for a broader look.

But then there’s another issue, which is that some people won’t seriously consider whistleblowers unless they identify themselves! What up? Facts are facts – if someone has given good evidence that can be checked independently, why should also submit themselves to being blacklisted for their efforts?

Here’s a good response to this crappy line of reasoning against anonymous whistleblowing by the Retraction Watch guys Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus.

What is a proof?

I recently described (here) a proof to be a convincing argument of why you think something is true. I’ll stick to that definition in spite of a few commenters who want there to be axioms or postulates, because I really don’t think that’s what happens in real life (which is a good thing! It would be an incredibly boring life!). Since I’m a utilitarian, I only care about and only want to discuss what actually happens.

The above definition immediately begs the question, convincing to whom? Can a proof to someone be a non-proof to someone else? Absolutely, proofs are entirely context-driven. If I’m trying to prove something to you and you remain unconvinced, then it is no proof, even if I’ve used the same argument before successfully.

This brings me to my first main point, which is that it the responsibility of the person proving something to convince his or her audience that it’s true. Likewise, it is the responsibility of the audience to remain skeptical (but attentive) and be open to being convinced or to finding a flaw in the argument.

Things get trickier when it’s not a live interaction, but when things are written down, like in published articles. On the one hand, written proofs give the audience more time to understand the reasoning and to come up with problems, but on the other hand there’s no opportunity to say “I just don’t get what you’re talking about,” which is the feeling one typically has at least 85% of the time.

In an ideal world, those who write proofs understand the goal to be that the reader should be able to understand the argument, and thus make the arguments coherent and understandable to their “typical reader.” Who is this typical reader? Someone who is probably relatively fluent in the basic objects of the field, say, but hasn’t recently thought about this problem.

Now that I’ve described the ideal situation, I’ll rant for a bit about how people game this system. There are two things that creep into the system that give rise to its gaming, and those two things are status and credit. People like to be high status (and like to signal high status even more), and of course people like to take credit.

First, status. It turns out that people often really want to explain their reasoning no to the typical audience, but to the expert audience. So they don’t give sufficient context, and they are lazy reasoners, because the experts can be expected to understand how to fill in the details.

It’s not only insecure young mathematicians that are guilty of this – there are plenty of experts who themselves fall prey to this habit (thus the signaling). I think it’s driven by a combination of feeling kind of smug and smart when people who are trying to follow your conversation leave because they’re exhausted and confused (and possibly ashamed), and the echo chamber that remains after people who don’t get it (or who admit to not getting it) leave. Whatever the reason, there are plenty of experts who get less and less understandable over time, in person and in print.

The other side of this status play is those experts get away with it. The papers written by these people are often accepted in spite of the fact that they are nearly unreadable to all but the 5 people in their field for whom they have been written, since after all, these guys are experts.

But does this approach constitute a proof? I claim it doesn’t, not if I have to be one of 5 people to read and understand it. The writer has choked, bigtime, on his or her responsibility to convince the reader.

Second, the credit thing. People want to get credit for proving things, because that’s how they get high status. But they don’t always want to prove everything they claim, because it’s hard work. So sometimes you see people proving something and then claiming an even more general thing is true, and giving a “sketch of a proof” for that more general thing (this is one example where “sketches” come up, but actually there are plenty of them).

Let’s examine that concept for a moment, the “sketch of a proof.” Usually this implies that the basic outline is there, but many details of how to rely on so-and-so’s theorem or what’s-his-name’s method are left out. It’s a proof lying in the shadows, and we’ve only seen it highlighted every few feet or so to wend our way through it.

Is a sketch a proof? No, it’s not. Best case scenario, it would take a typical reader a few minutes, maybe up to two hours, say, to turn that sketch into a proof.

But what if the typical reader can’t do it in two hours?

The problem with the concept of a sketch of a proof is that it’s too difficult to refute. If I am a reader and I say, “this is a false sketch” then I could just be opening myself up to people who tell me I didn’t spend my two hours wisely, or that I’m not good enough to complain about it. They may even expect me to prove that that method cannot be used to prove that result.

But that’s bullshit! As far as I’m concerned, if you claim to have sketched a proof, and if I’ve tried to prove it using your notes and I’ve failed, then that’s your fault, not mine. It’s your responsibility to prove it to me, and you haven’t.

Conclusion: let’s all remember when you claim a result, you are claiming credit, and it’s your responsibility to convince the audience it’s true – not just 5 experts. And second, if you aren’t willing to actually prove something, don’t claim it as a result. Instead, say something like, “this may generalize using so-and-so’s theorem or what’s-his-name’s method….”. Consider it a gift to the next person who reads your paper and wants to prove something new.

Why the internet is creepy

Recently I’ve been seeing various articles and opinion pieces that say that Facebook should pay its users to use it, or give a cut of the proceeds when they sell personal data, or something along those lines.

This strikes me a naive to a surprising degree; it means people really don’t understand how web businesses work. How can people simultaneously complain that Facebook isn’t a viable business and that they don’t pay their users for their data?

People have gotten used to getting free services, and they assume that infrastructure somehow just exists, and they want to have that infrastructure, and use it, and never see ads and never have their data used, or get paid whenever someone uses their data.

But you can’t have all of that at the same time!

These companies need to monetize somehow, and instead of asking users for money directly, which isn’t the current culture, they get creepy with data. The fact that there are basically no rules about personal information (aside from some medical information) means that the creepiness limit is extreme, and possibly hasn’t been reached yet.

What are the alternatives? I can think of a few, none of them particularly wonderful:

- Legislate privacy laws to make personal data sharing or storing illegal without explicit consent for each use (right now you just sign away all your rights at once when you sign up for the service, but that could and probably should change). This would kill the internet as we know it. In the short term the consequences would be extreme. Besides the fact that some people would save and use data illegally, which would be very hard to track and to stop, places like Twitter, Facebook, and Google would have no revenue model. An interesting thought experiment on what would happen after this.

- Make people pay for services, either through micro-payments or subscription services like Netflix. This would maybe work, but only for people with credit cards and money to spare. So it would also change access to the internet, and not in a good way.

- Wikipedia-style donation-based services. This is clearly a tough model, and they always seem to be on the edge of solvency.

- Get the government to provide these services as meaningful infrastructure for society, like highways. Imagine what Google Government would be like.

- Some combination of the above.

Am I missing something?

VAM shouldn’t be used for tenure

I recently read a New York Times “Room for Debate” discussion on the teacher Value-added model (VAM) and whether it’s fair.

I’ve blogged a few times about this model and I think it’s crap (see this prior post which is entitled “The Value Added Model Sucks” for example).

One thing I noticed about the room for debate is that the two most pro-VAM talking heads (this guy and this guy) both quoted the same paper, written by Dan Goldhaber and Michael Hansen, called “Assessing the Potential of Using Value-Added Estimates of Teacher Job Performance for Making Tenure Decisions,” which you can download here.

Looking at the paper, I don’t really think it’s a very good resource if you want to argue for tenure-decisions based on VAM, but I guess it’s one of those things, where they don’t expect you actually do the homework.

For example, they admit that year-to-year scores are only correlated between 20% and 50% for the same teacher (page 4). But then they go on to say that, if you average two or more years in a row, these correlations go up (page 4). I’m wondering if that’s just because they calculate the correlations that come from the same underlying data, in which case of course the correlations go up. They aren’t precise enough at that point to make me convinced they did this carefully.

But it doesn’t matter, because when teachers are up for tenure, they have one or two scores, that’s it. So the fact that 17 years of scores, on average, has actual information, even if true, is irrelevant. The point is that we are asking whether one or two scores, in a test that has 20-50% correlation year-to-year, is sufficiently accurate and precise to decide on someone’s job. And by the way, in my post the correlation of teachers’ scores for the same year in the same subject was 24%, so I’m guess we should lean more towards the bottom of this scale for accuracy.

This is ludicrous. Can you imagine being told you can’t keep your job because of a number that imprecise? I’m grasping for an analogy, but it’s something like getting tenure as a professor based on what an acquaintance you’ve never met head about your reputation while he was drunk at a party. Maddening. And I can’t imagine it’s attracting more good people to the trade. I’d walk the other way if I heard about this.

The reason the paper is quoted so much is that it looks at a longer-term test to see whether early-career VAM scores have predictive power for the students more than 11 years later. However, it’s for one data set in North Carolina, and the testing actually happened in 1995 (page 6), so before the testing culture really took over (an important factor), and they clearly exclude any teacher whose paperwork is unavailable or unclear, as well as small classes (page 7), which presumably means any special-ed kids. Moreover, they admit they don’t really know if the kids are actual students of the teacher who proctored the tests (page 6).

Altogether a different set-up than the idiosyncratic, real-world situation faced by actual teachers, whose tenure decision is actually being made based on one or two hugely noisy numbers.

I’m not a huge fan of tenure, and I want educators to be accountable to being good teachers just like everyone else who cares about this stuff, but this is pseudo-science.

I’m still obsessed with the idea that people would know how crappy this stuff is if we could get our hands on the VAM itself and set something up where people could test robustness directly, by putting in their information and seeing how their score would change based on how many kids they had in their class etc..

Statisticians aren’t the problem for data science. The real problem is too many posers

Crossposted on Naked Capitalism

Cosma Shalizi

I recently was hugely flattered by my friend Cosma Shalizi’s articulate argument against my position that data science distinguishes itself from statistics in various ways.

Cosma is a well-read broadly educated guy, and a role model for what a statistician can be, not that every statistician lives up to hist standard. I’ve enjoyed talking to him about data, big data, and working in industry, and I’ve blogged about his blogposts as well.

That’s not to say I agree with absolutely everything Cosma says in his post: in particular, there’s a difference between being a master at visualizations for the statistics audience and being able to put together a power point presentation for a board meeting, which some data scientists in the internet start-up scene definitely need to do (mostly this is a study in how to dumb stuff down without letting it become vapid, and in reading other people’s minds in advance to see what they find sexy).

And communications skills are a funny thing; my experience is communicating with an academic or a quant is a different kettle of fish than communicating with the Head of Product. Each audience has its own dialect.

But I totally believe that any statistician who willingly gets a job entitled “Data Scientist” would be able to do these things, it’s a self-selection process after all.

Statistics and Data Science are on the same team

I think that casting statistics as the enemy of data science is a straw man play. The truth is, an earnest, well-trained and careful statistician in a data scientist role would adapt very quickly to it and flourish as well, if he or she could learn to stomach the business-speak and hype (which changes depending on the role, and for certain data science jobs is really not a big part of it, but for others may be).

It would be a petty argument indeed to try to make this into a real fight. As long as academic statisticians are willing to admit they don’t typically spend just as much time (which isn’t to say they never spend as much time) worrying about how long it will take to train a model as they do wondering about the exact conditions under which a paper will be published, and as long as data scientists admit that they mostly just redo linear regression in weirder and weirder ways, then there’s no need for a heated debate at all.

Let’s once and for all shake hands and agree that we’re here together, and it’s cool, and we each have something to learn from the other.

Posers

What I really want to rant about today though is something else, namely posers. There are far too many posers out there in the land of data scientists, and it’s getting to the point where I’m starting to regret throwing my hat into that ring.

Without naming names, I’d like to characterize problematic pseudo-mathematical behavior that I witness often enough that I’m consistently riled up. I’ll put aside hyped-up, bullshit publicity stunts and generalized political maneuvering because I believe that stuff speaks for itself.

My basic mathematical complaint is that it’s not enough to just know how to run a black box algorithm. You actually need to know how and why it works, so that when it doesn’t work, you can adjust. Let me explain this a bit by analogy with respect to the Rubik’s cube, which I taught my beloved math nerd high school students to solve using group theory just last week.

Rubiks

First we solved the “position problem” for the 3-by-3-by-3 cube using 3-cycles, and proved it worked, by exhibiting the group acting on the cube, understanding it as a subgroup of and thinking hard about things like the sign of basic actions to prove we’d thought of and resolved everything that could happen. We solved the “orientation problem” similarly, with 3-cycles.

I did this three times, with the three classes, and each time a student would ask me if the algorithm is efficient. No, it’s not efficient, it takes about 4 minutes, and other people can solve it way faster, I’d explain. But the great thing about this algorithm is that it seamlessly generalizes to other problems. Using similar sign arguments and basic 3-cycle moves, you can solve the 7-by-7-by-7 (or any of them actually) and many other shaped Rubik’s-like puzzles as well, which none of the “efficient” algorithms can do.

Something I could have mentioned but didn’t is that the efficient algorithms are memorized by their users, are basically black-box algorithms. I don’t think people understand to any degree why they work. And when they are confronted with a new puzzle, some of those tricks generalize but not all of them, and they need new tricks to deal with centers that get scrambled with “invisible orientations”. And it’s not at all clear they can solve a tetrahedron puzzle, for example, with any success.

Democratizing algorithms: good and bad

Back to data science. It’s a good thing that data algorithms are getting democratized, and I’m all for there being packages in R or Octave that let people run clustering algorithms or steepest descent.

But, contrary to the message sent by much of Andrew Ng’s class on machine learning, you actually do need to understand how to invert a matrix at some point in your life if you want to be a data scientist. And, I’d add, if you’re not smart enough to understand the underlying math, then you’re not smart enough to be a data scientist.

I’m not being a snob. I’m not saying this because I want people to work hard. It’s not a laziness thing, it’s a matter of knowing your shit and being for real. If your model fails, you want to be able to figure out why it failed. The only way to do that is to know how it works to begin with. Even if it worked in a given situation, when you train on slightly different data you might run into something that throws it for a loop, and you’d better be able to figure out what that is. That’s your job.

As I see it, there are three problems with the democratization of algorithms:

- As described already, it lets people who can load data and press a button describe themselves as data scientists.

- It tempts companies to never hire anyone who actually knows how these things work, because they don’t see the point. This is a mistake, and could have dire consequences, both for the company and for the world, depending on how widely their crappy models get used.

- Businesses might think they have awesome data scientists when they don’t. That’s not an easy problem to fix from the business side: posers can be fantastically successful exactly because non-data scientists who hire data scientists in business, i.e. business people, don’t know how to test for real understanding.

How do we purge the posers?

We need to come up with a plan to purge the posers, they are annoying and making a bad name for data science.

One thing that will be helpful in this direction is Rachel Schutt’s Data Science class at Columbia next semester, which is going to be a much-needed bullshit free zone. Note there’s been a time change that hasn’t been reflected on the announcement yet, namely it’s going to be once a week, Wednesdays for three hours starting at 6:15pm. I’m looking forward to blogging on the contents of these lectures.

Income distributions and misleading poll questions (#OWS)

Disingenuous, pseudo-quantitative arguments piss me off.

In this recent Bloomberg View article entitled “Making the rich poorer doesn’t enrich the middle class,” Caroline Baum argues that middle class people would rather get more money than take away money from rich people. From the article:

Polling by the Pew Research Center shows that people aren’t interested in taking money from the wealthy. They just want a chance to get rich themselves.

But that’s a misleading question. It seems like a zero sum game when you put it that way, equivalent to something like, “Would you rather gain $100 or have a rich person somewhere lose $100?”.

But if you pose the question differently, and more in line with actual numbers, not to mention contextualized to reality in other ways, then you’d probably get the opposite.

Let’s take a look at wealth distribution from 2007, which I got here:

Let’s just say we’re being extreme and we take away all the wealth of the top 1% and give it to everybody equally (say we even give back some of it to those top 1%). That would mean that 34.6% get flattened out to 100 pots instead of one, which means that each of those percentiles gets about 0.35% more than they used to have. The middle 20% would grow from 4% of the overall wealth to (4 + 20*0.35)% = 11%. That’s still a lot less than 20%, but the wealth of the middle 20% is still nearly tripled by just this one percent re-distributing.

Let’s just say we’re being extreme and we take away all the wealth of the top 1% and give it to everybody equally (say we even give back some of it to those top 1%). That would mean that 34.6% get flattened out to 100 pots instead of one, which means that each of those percentiles gets about 0.35% more than they used to have. The middle 20% would grow from 4% of the overall wealth to (4 + 20*0.35)% = 11%. That’s still a lot less than 20%, but the wealth of the middle 20% is still nearly tripled by just this one percent re-distributing.

Said another way, it’s not tit-for-tat at all.

If we asked someone in the middle class which they want more, a 1% increase in their wealth or a top 1%’er to lose 1% of their wealth, then that might be very different. Consider the political influence that 1% represents, at the very least. Consider the fact that 1% of that person in the middle 20% is 173 times smaller than for the top 1%.

It’s still not fair, though, because the middle class is so squeezed on necessities like food, housing, education, medical expenses, and child care, that they can’t afford even a 1% loss. What if you took those out?

If you go even further and ask someone in the middle class which they want more, a 1% increase in their discretionary income or a top 1%’er to lose 1% of their discretionary income, then that might be very different still. I haven’t been able to find a similar graphic to work with to see the discretionary income distribution, but rest assured it’s even more unbalanced.

Caroline Baum, would you care to cover those questions on your next poll to the middle class?

Is open data a good thing?

As much as I like the idea of data being open and free, it’s not an open and shut case. As it were.

I’m first going to argue against open data with three examples.

The first is a pretty commonly discussed concern of privacy. Simply put, there is no such thing as anonymized data, and people who say there is are either lying or being naive. The amount of information you’d need to remove to really anonymize data is not known to be different from the amount of data you have in the first place. So if you did a good job to anonymize a data set, you’d probably remove all interesting information anyway. Of course, you could think this is only important with respect to individual data.

But my next example comes from land data, specifically Tamil Nadu in Southern India. There’s an interesting Crooked Timber blogpost here (hat tip Suresh Naidu) explaining how “open data” has screwed a local population, the Dalits. Although you could (and I would) argue that the way the data is collected and disseminated, and the fact that the courts go along with this process, is itself politically motivated and disenfrachising, there are some important point made in this post:

Open data undermines the power of those who benefit from “the idiosyncracies and complexities of communities… Local residents [who] understand the complexity of their community due to prolonged exposure.” The Bhoomi land records program is an example of this: it explicitly devalues informal knowledge of particular places and histories, making it legally irrelevant; in the brave new world of open data such knowledge is trumped by the ability to make effective queries of the “open” land records.15 The valuing of technological facility over idiosyncratic and informal knowledge is baked right in to open data efforts.

The Crooked Timber blog post specifically called out Tim O’Reilly and his “Government as Platform” project as troublesome:

The faith in markets sometimes goes further among open data advocates. It’s not just that open data can create new markets, there is a substantial portion of the push for open data that is explicitly seeking to create new markets as an alternative to providing government services.

It’s interesting to see O’Reilly’s Mike Loukides’s reaction (hat tip Chris Wiggins), entitled the Dark Side of Data, here. From Loukides:

The issue is how data is used. If the wealthy can manipulate legislators to wipe out generations of records and folk knowledge as “inaccurate,” then there’s a problem. A group like DataKind could go in and figure out a way to codify that older generation of knowledge. Then at least, if that isn’t acceptable to the government, it would be clear that the problem lies in political manipulation, not in the data itself. And note that a government could wipe out generations of “inaccurate records” without any requirement that the new records be open. In years past the monied classes would have just taken what they wanted, with the government’s support. The availability of open data gives a plausible pretext, but it’s certainly not a prerequisite (nor should it be blamed) for manipulation by the 0.1%.

[Speaking of DataKind (formerly Data Without Borders), it’s also a problem, as I discovered as a data ambassador working with the NYCLU on Stop, Question and Frisk data, when the government claims to be open but withholds essential data such as crime reports.]

My final example comes from finance. On the one hand I want total transparency of the markets, because it sickens me to think about how nobody knows the actual price of bonds, or the correct interest rate, or the current default assumption of the market, how all of that stuff is being kept secret by Wall Street insiders so they can each skim off their little cut and the dumb money players get constantly screwed.

But on the other hand, if I imagine a world where everything really is transparent, then even in the best of all database situations, that’s just asstons of data which only the very very richest and most technologically savvy high finance types could ever munge through.

So who would benefit? I’d say, for some time, the average dumb money customer would benefit very slightly, by not paying extra fees, but that the edgy techno finance firms would benefit fantastically. Then, I imagine, new ways would be invented for the dumb money customers to lost that small amount of benefit altogether, probably by just inundating them with so much data they can’t absorb it.

In other words, open data is great for the people who have the tools to use it for their benefit, usually to exploit other people and opportunities. It’s not clearly great for people who don’t have those tools.

But before I conclude that data shouldn’t be open, let me strike an optimistic (for me) tone.

The tools for the rest of us are being built right now. I’m not saying that the non-exploiters will ever catch up with the Goldman Sachs and credit card companies, because probably not.

But there will be real tools (already are things like python and R, and they’re getting better every day), built out of the open software movement, that will help specific people analyze and understand specific things, and there are platforms like wordpress and twitter that will allow those things to be broadcast, which will have real impact when the truth gets out. An example is the Crooked Timber blog post above.

So yes, open data is not an unalloyed good. It needs to be a war waged by people with common sense and decency against those who would only use it for profit and exploitation. I can’t think of a better thing to do with my free time.

Today is a day for politics

President Obama made comments last Friday in Fort Myers, Florida, about the Aurora theater shooting in Colorado. Here’s an excerpt of what he had to say:

So, again, I am so grateful that all of you are here. I am so moved by your support. But there are going to be other days for politics. This, I think, is a day for prayer and reflection.

This makes no sense. Actually, it’s offensive. When is it a day for politics, President Obama? And why are we treating this tragedy like an act of nature?

When a guy gets enough ammunition shipped to him legally, through the U.S. Post Office, to perform a massacre, and he rigs his house with sophisticated booby traps over months of preparation, we can safely say two things. First, this guy was absolutely insane, and second he had all of the resources available to him to kill dozens of people.

I can understand why, for the families of the victims, their therapists or priests may ask them to accept this fatalistically – they can’t get their loved one back. But as a nation, we should not be willing to be so passive in the face of what is obviously a fucked up system. We can imagine, I hope, a culture where it’s a wee bit more difficult to massacre innocent people if and when you decide that’s a good idea.

If you’re in doubt that this system is skewed towards the madman, keep in mind that the uninsured Aurora shooting victims are at risk of debtor’s prison in this country.

It begs the question of why we’ve become so inured to bad politicians. Notice I’m not saying inured to violence and random shootings, because we’re not, actually. We are all horrified, but in the face of such tragedy we shrug our shoulders and say stuff about the fact that there’s nothing we can do. Because that’s what our politicians say.

I’ll draw an analogy between this and the financial crisis, which is ongoing and could be getting worse. We often hear passive, third person narratives coming from our politicians and central bankers, who talk about the bankrupt banks and the corruption like there’s nothing we can actually do to fix this. Again, acts of nature.

Bullshit. These guys have been paid off by bank lobbyists and told to act impotent. They are following orders. Our country deserves better than this leadership, whose politicians give money to banks, which they turn around and use to buy off politicians. As Neil Barofsky said in his new book:

“The suspicions that the system is rigged in favor of the largest banks and their elites, so they play by their own set of rules to the disfavor of the taxpayers who funded their bailout, are true,” Mr. Barofsky said in an interview last week. “It really happened. These suspicions are valid.”

I’d like to separate, for a moment, two issues. First, what we have come to expect from Obama, who gave us such hope when he was elected. Second, what we deserve – what we should expect from a politician who cares about people and doing the right thing.

There’s a huge difference, but let’s not lose sight of that second thing. That’s when I turn from pissed to bitter, and I really don’t want to be bitter.

This is a day for politics, President Obama, so step it up. I’m not giving up hope that someone, though probably not you, can deliver it to us.

A call to Occupy: we should listen.

Yesterday a Bloomberg View article was published, written by Neil Barofsky.

In case you don’t remember, Barofsky was the special inspector general of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which meant he was in charge of watching over TARP until he resigned in February 2011. And if you can judge a man by his enemies, then Barofsky is doing pretty well by being cussed out by Tim Geithner.

The Bloomberg View article was an excerpt from his new book, which comes out July 24th and which I’m going to have to find time to read, because this guy knows what’s going on and the politics behind possible change.

In the article, Barofsky tears through some of the most obvious and ridiculous shenanigans that the Obama administration and the Treasury have been up to in preserving the status quo whereby the banks get bailed out and the average person pays. In order, he obliterates:

- Obama’s HAMP project: “with fewer than 800,000 ongoing permanent modifications as of March 31, 2012, a number that is growing at the glacial pace of just 12,000 per month.”

- The recent mortgage settlement: “In return for what was touted as a $25 billion payout, the banks received broad immunity from future civil cases arising out of their widespread use of forged, fraudulent or completely fabricated documents to foreclose on homeowners.” and “As a result, the settlement will actually involve money flowing, once again, from taxpayers to the banks.”

- The recent so-called Task Force for investigating toxic mortgage practices: “it seems unlikely that an 11th-hour task force will result in a proliferation of handcuffs on culpable bankers.”

- The Dodd-Frank Bill: “…the market distortions that flow from the presumption of bailout may have gotten worse. By failing to alter this presumption, Dodd-Frank may have inadvertently sowed the seeds for the next financial crisis.”

- Specifically, the Volcker Rule, where he quotes a milquetoast Geithner: `“We’re going to look at all the concerns expressed by these rules,” he said. “It is my view that we have the capacity to address those concerns.”’ – Barofsky draws a line directly from Geithner to the conclusion of Senator Levin, `“Treasury are willing to weaken the law.”’ Barofsky here highlights out the most basic problem we face, namely that regulators are suckling from their Wall Street masters: “Indeed, words like Geithner’s, when accompanied by actions such as the Fed’s authorization of the largest banks to release capital, send what should be a clear message. We may be in danger of quickly returning to the pre-crisis status quo of inadequately capitalized banks that take outsized risks while being coddled by their over-accommodating regulators. A repeat of the financial crisis would soon be upon us.”

- Finally, he gets on my favorite riff about TARP, namely that it’s not about the money being paid back, it’s about the risk that we’ve taken on as a nation.

But what’s most interesting to me about the article is the fact that he’s not proposing a political solution to the unbelievably unbalanced distribution of resources. Probably this is because the political power is so firmly entrenched and because it is so firmly corrupt that there’s no use barking up that tree. Instead, he is asking for Occupy and other popular movements to step it up. The article ends:

The missteps by Treasury have produced a valuable byproduct: the widespread anger that may contain the only hope for meaningful reform. Americans should lose faith in their government. They should deplore the captured politicians and regulators who distributed tax dollars to the banks without insisting that they be accountable. The American people should be revolted by a financial system that rewards failure and protects those who drove it to the point of collapse and will undoubtedly do so again.

Only with this appropriate and justified rage can we hope for the type of reform that will one day break our system free from the corrupting grasp of the megabanks.

The question I have is, will we need yet another financial crisis to get this done? (Not that I think one is far off- the banning of short selling recently by Spain and Italy is a desperate move, kind of like throwing in the towel and admitting you’d rather openly manipulate markets than let people have honest opinions.)

I for one think we’ve got plenty of evidence right now, and I’m outraged. But maybe not everyone is, and I take responsibility for that.

I think my job now, as an Occupier, is to make sure people understand that these decisions and speeches made at the Treasury and the White House are directly related to people illegally losing their homes and jobs and town services and having their pensions rewritten after they’ve reached retirement age. I absolutely believe that, if people knew all of those connections, we’d have an enormous number of people ready to occupy and the political power to do something.

It rocks to be 40

So it’s my birthday today, I’m finally 40. I’m enjoying it so much I started calling myself 40 like four months ago because I couldn’t wait.

I’m not exactly sure why it is so meaningful to me, this number. You might think I’m enough of a rebel to just not care at all about a number like this, even though it is certainly culturally significant. But here’s the thing, I’m owning it.

Since I’m an alpha female, being 40 frees me up quite a bit. I don’t have to even imagine not being taken seriously or being thought of as too young or inexperienced to have an opinion. I have no urge to be cute or play dumb. Leave that to younger people, it wouldn’t work for me anymore anyhow.

My dad used to tell me to try to be “more demure” so that people wouldn’t be put off by me. Worst advice ever. I definitely have gotten more out of my life by being completely honest and upfront than by playing a synthetic role. It also wastes less time for everyone. At this point I’m able to look over my experiences and know things like that rock-solid, and not second guess myself. That’s a good feeling.

You know what rocks about being 40? It comes down to this: I am old enough to know the difference between bullshit and the good stuff and I’m still feeling healthy and fully capable of enjoying the good stuff. It is seriously freeing, and I’m looking forward to everything about it. And I say this basically unemployed and not knowing what I’m doing next, which for some reason gives rise to the most freeing moments for me.

Presents I don’t want for my 40th birthday:

- hair dye. I’m letting myself go grey, it’s gorgeous IMHO.

- anti-wrinkle cream. Screw that.

- girdles. I’ve already complained about that.

Presents I might want for my 40th birthday:

- a night out on the town ending with karaoke is always nice.

- puzzles and games. I’ve always love playing with puzzles. Crosswords too.

- time with the many people I love. That’s the best part.

Let’s do this, people! Fuck yeah!!

How to lie with statistics, Merck style

In the pharmaceutical industry, where companies are making enormous bets with huge money and people’s lives, it makes sense that there are conflicting interests. The companies, who are in charge of testing their drugs for safety and for successful treatment, tend to want to emphasize the good and ignore the bad.

That’s why they are expected to describe beforehand how they are planning to do the tests. It stands to reason that, if they did a thousand tests and then only reported on the best ones, the public would get a biased view of the safety of their products.

For some reason, though, this standard doesn’t seem to be universally followed, and lying with statistics seems to be okay.

The newest example comes from Merck (see Pharmalot article here), which changed its statistical methods on testing Vioxx for Alzheimer’s patients from an intent-to-treat analysis to an on-treatment analysis even though their stipulated plans were the former. And even though the standard in the industry is the former.

Intent-to-treat means you choose people and stick with them, even if they get off the drug for some reason. And on-treatment only counts people that stay on the drug the whole time.

The difference is one of survivorship bias; there may be a good reason someone gets off the drug, and that may be because they got sick, and maybe they got sick because they were taking the drug.

What’s the difference in this case? From the article:

A subsequent intent-to-treat analysis found that as of April 11, 2002, when the FDA approved Vioxx labeling, there were 17 confirmed cardiovascular deaths on Vioxx compared with five on placebo in the same two trials.

With their on-treatment analysis, though, they didn’t see an elevated risk. So as it turns out the actual heart attacks happened a couple of weeks after people got off the pill.

So what happened there? Why were they allowed to change their stipulated method? Why were they allowed to not report their stipulated, gold-standard method? That’s complete bullshit and it must mean that someone at the FDA is either insanely stupid or very rich. Or both.

I’ve written about this issue before, specifically here. Just let me remind you of how we might assess the damage done by Merck through their statistical shenanigans:

Also on the Congress testimony I mentioned above is Dr. David Graham, who speaks passionately from minute 41:11 to minute 53:37 about Vioxx and how it is a symptom of a broken regulatory system. Please take 10 minutes to listen if you can.

He claims a conservative estimate is that 100,000 people have had heart attacks as a result of using Vioxx, leading to between 30,000 and 40,000 deaths (again conservatively estimated). He points out that this 100,000 is 5% of Iowa, and in terms people may understand better, this is like 4 aircraft falling out of the sky every week for 5 years.

According to this blog, the noticeable downwards blip in overall death count nationwide in 2004 is probably due to the fact that Vioxx was taken off the market that year.

Finally, I’d like to reiterate my question, why are pharmaceutical companies allowed to do their own trials?

Mathematicians know how to admit they’re wrong

One thing I discussed with my students here at HCSSiM yesterday is the question of what is a proof.

They’re smart kids, but completely new to proofs, and they often have questions about whether what they’ve written down constitutes a proof. Here’s what I said to them.

A proof is a social construct – it is what we need it to be in order to be convinced something is true. If you write something down and you want it to count as a proof, the only real issue is whether you’re completely convincing.

Having said that, there are plenty of methods of proof that have been standardized and will help you in your arguments. There are things like proof by contradiction, or the pigeon hole principle, or proof by induction, or taking cases.

But in the end you still need to convince me; if you say there are three cases to consider, and I find a fourth, then I’ve blown away your proof, even if your three cases looked solid. If you try to prove something by induction, but your inductive step argument fails going from the case n=16 to n=17, then it’s not a proof.

Ultimately, then, a proof is a description of why you think something is true. The first half of your training is to problem solve (so, come up with a reason something is true) and construct a really convincing argument.

Coming at it from the other side, how can you check that what you’ve got is really a proof if you’ve written down the reason you think it’s true? That’s when the other half of your training comes in, to poke holes in arguments.

To be a really good mathematician you need to be a skeptic and to walk around with a metaphorical gun to shoot holes in other people’s arguments. Every time you hear a reasoned explanation, you look for the cases it doesn’t cover or the assumptions it’s making.

And you do the same thing with your own proofs to help yourself realize your mistakes before looking like a fool. Because putting out a proof of something is tantamount to asking for other people to shoot holes in your argument.

For that reason, every proof that one of these young kids offers up is an act of courage. They don’t know exactly how to explain their thinking, nor do they yet know exactly how to shoot holes in arguments, including their own. It’s an exercise in being wrong and admitting it. They are being trained to get shot down, to admit their mistake, and then immediately get back up again with better reasoning. The goal is to get so good at being wrong that it doesn’t hurt, that it’s not taken personally, and that it’s even fun to be wrong and to improve your argument.

Not every person gets trained in being wrong and admitting it. I’d wager that most people in the world, for most of their professional lives, are trained to do the opposite in the face of being wrong: namely, to wriggle out of it or deflect criticism. Most disciplines spend more time arguing they’re right, or at least not as wrong, or at least they have different mistakes, than other related fields. In math, you can at the most argue that what you’re doing is more interesting or somehow more important than some other field.

[I’ve never understood why people would think certain math is more important than other math. It’s almost never on the basis of having applications in the real world, or helping people in some way. It’s just some arbitrary snobbery, or at least that’s how it’s seemed. For my part I can’t explain why I love number theory more than analysis, it’s pure sense of smell.]

Most people never even say something that’s provably wrong in the first place. And that makes it harder to prove they’re wrong, of course, but it doesn’t mean they’re always right. Since they’ve not let themselves get pinned down on a provably wrong thing, they tend to stick with their wrong ideas for way too long.

I’m a huge fan of skepticism, and I think it’s generally undervalued. People who run companies, or universities, or government agencies, typically say they like healthy skepticism but actually want people to drink the kool aid. People who are skeptical are misinterpreted as being negative, but there’s a huge difference: negative means you’re not trying to solve the problem, skeptical means you care enough about the problem to want to solve it for real.

Now that I’ve thought about the training I’ve received as a mathematician, though, and that I’m now giving that training to these new students, I’ll add this to my defense of skepticism: I’m also a huge fan of people being able to admit they’re wrong. It’s the flip side of skepticism, and it’s why things get better instead of stay wrong.

By the way, one caveat: I’m not claiming that mathematicians are any better at admitting they’re wrong outside a strictly logical sphere.

Toilet paper rant

I’ve been here at HCSSiM for almost exactly a week now, and I’ve been exclusively blogging about what mathematics we’ve been teaching this year’s brilliant crop of high school kids. Considering the fact that I usually have lots of opinions on important subjects such as financial reform, data science, and the incorrigible misuse of statistics, you might think I’m dying to also post about such things now that it’s Sunday and I’ve finally had time to catch up on some sleep.

You’d be wrong.

What I really need to vent about this afternoon is toilet paper dispensers. You see, I’ve been using lots of bathrooms with stalls and with those new-fangled huge toilet paper dispensers.

Do you remember in the olden days when a toilet paper dispensing system was relatively easy to understand? There’d be room for at most two rolls, the normal smallish kind, and if that wasn’t enough there’d be extra rolls somewhere for you to use. Granted, sometimes there weren’t, and sometimes there were but they got wet or dirty rolling on the floor.

Nowadays there are they enormous plastic cases which contain about 4 huge rolls of toilet paper, and I guess it’s a good thing in terms of how often toilet paper runs out, although it’s not an excellent idea in terms of the overall cleanliness of the bathroom, since you can mostly fill those fuckers up and leave for vacation.

But I’m not here to complain about dirty bathrooms. What I’d like to complain about is that these huge toilet paper dispensers, which are now about 3 feet in diameter, are for some reason always placed at the same level, at their center, as their older counterparts which contained two small rolls and opened up in the front.

The old dispenser would allow you to get toilet paper at approximately shoulder level. It was a pretty good system.

But these new ones dispense out at the bottom, so now we’re immediately talking about having to bend down to even find a corner of paper, usually blind. God forbid if it’s a new roll.

And once you catch hold of the ephemeral toilet paper corner, you have to then pull out some paper, which sounds easy, but your natural inclination is to pull on the paper by pulling towards yourself. This causes your tiny little corner of toilet paper to be immediately cut off by the serrated edge of the dispenser mouth.

So what you need to do, unless you are satisfied with one square inch of toilet paper (which I am not, in general), is you need to devise a two-handed system of pulling where one hand acts as a soft corner, almost like a ball bearing pulley, directly below the dispenser mouth, and the other hand pulls on it, at first straight down and then around the other hand and up.

But mind you, you’re already stooping over to get the paper. So at this point you are basically on hands and knees trying to get more than one square inch of goddamned toilet paper.

People. People. People who install bathrooms, I’m talking to you right now.

Don’t you ever go to the bathroom yourself? Can’t you modify your installation procedure now that these big toilet roll dispensers have been around now for 10 years? Can we get them to dispense at shoulder level some time in the near future? Is this some way of keeping people from using too much toilet paper? If so, it’s not working. I always take too much because I always figure, “what the hell, now that I’ve constructed a pulley system I might as well see what she can do. I’ma gonna let her rip.”

Is a $100,000 pension outrageous?

There are lots of stories coming out recently about how public workers, typically police or firefighters, are retiring with “outrageous” pensions of $100,000. Here’s one from the Atlantic. From the article:

That doesn’t frustrate Maviglio, who insists that “people who put their lives on the line every day deserve a secure retirement.” But do they “deserve” more than twice the US median income? Do they “deserve” the sum the average California teacher makes, plus $32,000? Do they “deserve” pensions far higher than the highway workers whose jobs are much more dangerous? These aren’t idle questions, given the public safety worker retirements we can expect in the near future.

Okay, let’s go there. If the median income in the country is 38,000, then $100,000 is a lot. But the median income in the communities where these retired firefighters live is sometimes much higher. For example, in Orange County, where the pension system is getting lots of flak, the median incomes can be seen here. In only one community out of is it below $50,000, and in 8 it’s above $100,000. So if you look at it that way then it doesn’t seem so outrageous.

And maybe we should be paying our teachers and our highway workers more, for that matter.

Point #1: California is a rich state, and it costs a lot of money to live there.

Now let’s move on to articles like this, which frame the issue in a very specific way. The title:

Police and Firefighter Pensions Threaten Government Solvency

How about all the other things that have contributed? Why are we blaming these guys, who have worked all their lives to protect their community? Why aren’t we blaming the mafia behind the muni bond deals, or sometimes even the local politicians as well?

Point #2: This is all a political blame game, trying to manipulate you from thinking about who are the actual crooks behind the scenes here.

My momma always said double down, and this is the ultimate double-down opportunity. Instead of looking for where the money went, or why it was handled so badly, we are going to blame the guys on taking the boring public servant job, and doing it for their adult lives, and trying to retire. Basically, we are blaming them for being right, for making the better choice between public and private.

Point #3: They made the right choice and we can’t swallow it because we thought our whole lives they were suckers for working in public service instead of in finance.

And what about that? Why do we compare $100,000 pensions to median incomes but not to golden parachute retirement packages of failing CEOs? Where’s the real outrage? Here’s another list of some seriously outrageous golden parachutes.

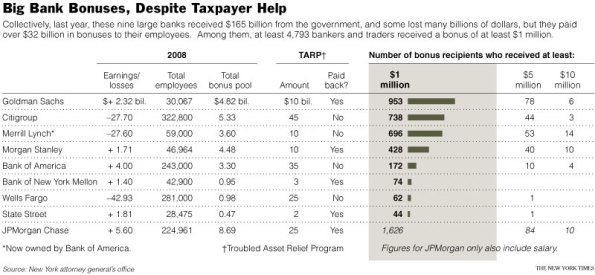

Maybe it’s because we feel like private pay is not our business, as taxpayers. It’s a different arena, and we have no right to judge. Let me remind you then that we taxpayers paid for bonuses at too-big-to-fail banks:

Point #4: These pensions don’t look very big when you compare them to what happens in the private sector.

And yes, I’m talking about the extreme cases, but so does everyone else when they talk about “outrageous pensions”, so it’s extreme-case apples to extreme-case apples.

Why are pharmaceutical companies allowed to do their own trials?

A recent New York Times article clearly addressed the problem with big pharma being in charge of its own trials. In this case it was Pfizer doing a trial for Celebrex, but I previously wrote about Merck doing corrupt trials for Vioxx (see How Big Pharma Cooks Data: The Case of Vioxx and Heart Disease). In the article, it has the following damning evidence that this practice is ludicrous:

- Research Director Dr. Samuel Zwillich, in an email after a medical conference discussing Celebrex, stated: “They swallowed our story, hook, line and sinker.”

- Executives considered attacking the trial’s design before they even knew the results. “Worse case: we have to attack the trial design if we do not see the results we want,” a memo read. It went on: “If other endpoints do not deliver, we will also need to strategize on how we provide the data.” This simply can’t happen. There should be an outside third-party firm in charge of trial design, and there needs to be sign-off on the design in advance so no monkey business like this takes place.

- Executives disregarded the advice of an employee and an outside consultant who had argued the companies should disclose the fact that they were using incomplete data – they were using only half. This kind of statistical dishonesty is the easiest way to get numbers you want.

- In another email, associate medical director Dr. Emilio Arbe from Pharmacia (which was later bought by Pfizer) disparaged the way the study was being presented as “data massage,” for “no other reason than it happens to look better.” Mind you, this statement was made in September 2000, so in other words the side effects of Celebrex have been known for over a decade.

- Medical Director Dr. Mona Wahba described it as “cherry-picking” the data. In May 2001.

Why is this happening? It’s all about money:

It is one of the company’s best-selling drugs, racking up more than $2.5 billion in sales, and was prescribed to 2.4 million patients in the United States last year alone.

How much are you in doubt that the people in charge are being pressured not to be honest? Dr. Samuel Zwillich claims the hook, line and sinker statement was probably about something else. The cherry-picking Dr. Mona Wahba now can’t remember what she meant.

This is bullshit, people. Statistics is getting a bad name, and people are suffering and dying from bad medicine, not to mention paying way too much for fancy meds that don’t actually help them more than aspirin.

What we need here is some basic integrity. And it’s not just a few bad eggs either – stay tuned for a post on Prof. David Madigan’s recent research on the robustness of medical trials and research in general.

Is science a girl thing?

One of the reasons I chose to call this blog “mathbabe” is that when I searched that term, I found a website, now defunct (woohoo!), where semi-naked women were adorning math.

This pissed me off, because I want math babes to be doing math.

If you get that (what’s not to get?) then you might see why the European Commission’s latest effort to inspire girls to do science is truly repugnant (hat tip Debbie Berebichez, a.k.a. Science Babe).

It’s a commercial where you see a standard male scientist (in a white lab coat no less) being surprised, and, we assume, aroused, when three girly models come in, giggle, dance, and generally adorn the commercial.

At the end they put on lab goggles in the style of an ironic accessory. They’re all wearing high heels and there’s even lipstick in a few shots for some unexplained reason (are we supposed to infer that wearing lipstick makes you more scientific-alicious?).

And although there are a couple of shots of an actual female writing what could be actual formulas on a hyped-up whiteboard, that’s more than balanced by some other shots of the models with unmistakable come-hither looks, gestures and blown kisses.

People. At the European Commission. Do you have no advisors!? Do you have no common sense? Who vetted this garbage video?!?

I’d like to see us get to the point where our slogan is more along the lines of:

Science, it’s for really smart women

And our video consists of cool, funky women giving actual talks and lectures or actually working on experiments. Maybe they’re wearing heels, but for sure they’re not acting like complete fucking idiots. How’s that?

I personally could suggest about 40 people for such a video. Not hard to do.

Please don’t have any kids

I recently read this New York Times article about choosing to have kids, called “Think Before You Breed”.

It describes the pressure childless people have from breeders to have kids. I believe they feel that pressure, and I want to explain it a bit, from the point of view of a person with three kids.

First of all, if you feel pressure coming from me, it’s entirely unintentional. In fact, I consider having children a deeply irrational thing to do – any kind of cost/benefit analysis focusing on material costs and such would steer me very wide of the practice of sacrificing my health, my time, and enormous amounts of resources to these little economic leeches that likely won’t even talk to me after they leave for college, which I will be paying for if I can afford it.

And not only is having kids a stupid idea in terms of economics – it’s also a hugely dangerous proposition, because it’s so much easier to screw up your kids than it is to raise healthy, well-adjusted people. There are pitfalls in every direction, and when it comes to it I think there should be a 4-year college, with forced enrollment of people who are embarking on the parenting thing, before it happens. That nothing like this happens, that kids themselves can have kids without any planning or training, is actually crazy considering how much maturity is required to do a half-decent job of it.

The only defense I really have of bearing three children is that my instincts told me to do it, and they, my instincts, didn’t play fair. In fact until I turned 23 I didn’t want kids, and I had a completely rational view of how much of a pain they’d be, and how much they’d take over my life, etc.. But somehow when I turned 23, there was something deep in my gut that kicked in and made me start missing my as-yet-unborn kids, as if I’d forgotten to kiss them goodnight and they were whimpering upstairs in their rooms. I know, I know, it’s over the top, but there you have it, instincts take no prisoners.

In summation: I don’t want you to have kids unless you absolutely have to. It’s bad for the planet, it’s bad for you, and it’s likely bad for your kids. The only thing I’d be checking if I ask you whether you plan to have kids is whether you have caught the same disease I did when I turned 23 – it’s not a request! It’s a sanity check!

Now I don’t think I’m completely normal in my view. I do think that lots of people get so intoxicated with the breeding thing that they literally think other people are insane if they don’t want to join the club. That’s super annoying and I don’t think there’s much you can actually do about these people. If it helps, when I’m listening in on that conversation I’ll be happy to interject and suggest that nobody in their right mind would ever breed. But rational arguments such as lack of resources, time, and attention would probably not sway these people, because they are true believers and need to think that it’s the only reasonable thing to do. They are married to convention.

They are also usually convinced their kids will never hate them, never move across the country for college and refuse to write, so the argument that they’ll be lonely when they’re old also doesn’t seem to help – they will tell you that, as a non-breeder, it will be you who is lonely when you’re old. It’s ironic, this line of argument, especially because you’re often talking to someone who hasn’t invested themselves in hobbies; they’re obsessed with the progress of their kids’ violin lessons and robotics teams but don’t have a true independent interest outside their children. Do they really think their kids will still let them into their lives 24 hours a day when they’re 25?

I firmly believe that, without kids, I could be establishing a far richer network of (probably childless) friends that will still be around to hang out with and talk politics when I get old. I’m still trying to do this now, by the way, but most nights I need to get home by 5:45 to make plain pasta and steamed broccoli, the only two things I’ve eaten in the past 12 years.

Look, everyone tries to convince themselves and people around them that the life choices they’ve made are the right ones. It’s uncomfortable to constantly feel like an idiot about this kind of thing, believe me. For myself, in spite of how irrational I have been, I can truly say I’ve managed to convince myself on a daily basis that I don’t mind the sacrifice because at least I get to hear my kids say insulting, sarcastic things that seem new to me (“ooh, I hadn’t heard that one! It’s goooood!”). It all makes it worth it. Plus I love them to bits, and they happen to be really cool people that might just contribute positively to the world whilst having a raucous amount of mischievous fun. At least that’s what I’ll imagine is happening when I’m old and lonely.