Archive

Who will Regulate the Superheroes on Wall Street?

This is a guest post by Elizabeth Friedrich, a member of Occupy the SEC.

Wall Street has grown to celebrate superheroes like Lloyd Blankfein and Jamie Dimon for their superior management skills and keen business sense. We have come to praise and applaud reckless risk-takers on the assumption that the markets always know best.

Insider Wall Street leaders like Jamie Dimon are viewed to possess special powers. In fact, many believe that Dimon, who led JP Morgan out of the financial crisis, is a banking prodigy who could do no wrong. But even Dimon is helpless in the face of reckless risk-taking behavior by his employees, as shown by the trader Bruno Iksil who lost $3 billion dollars and counting as part of JP Morgan’s CIO office. “Star traders” like Iksil structure their trades in such a complicated way that the average person could never understand them. We have no way of knowing whether the hedges that the CIO office put on actually “hedged” the original position. Such complexity, conveniently, can also serve as a powerful tool to refute public outcry.

The question here is this: Why create such risk in the first place? Or, more importantly: Why create the type of transactions that require a superman to oversee them?

Since the Volcker Rule is still being finalized, banking institutions will continue to take on these risks as long as they are allowed or exempted to do so. However, banks should face the same consequences as the rest of society. The “London Whale” trades created massive disruptions in an already fragile market and, ironically, they have caused unrest and disgust in the hedge fund community – the very community that loves unregulated market competition. Why don’t we hold banks to their own standards and stop giving them a pass when they fail?

Occupy the SEC will be marching today calling for the S.E.C. to investigate Jamie Dimon for violation of the disclosure requirements of Sarbanes-Oxley Act. We will also recommend that the S.E.C. make a criminal referral to the Department of Justice. Many people are frustrated with the slap-on-the-wrist treatment that Wall Streeters enjoy; random petty criminals are sentenced to hard jail time but the trader who loses billions of dollars is told not to do that again. The JP Morgan Chase debacle is symptomatic of a broken regulatory system.

Even if there are no criminal charges against Jamie Dimon, the American public would have been well-served to see Wall Street have its day in court. The S.E.C. has to uphold its foundational principles: 1) public companies offering securities to investors must tell the truth about their business, the securities, and the risks involved in investing; and 2) people who sell and trade securities must treat investors fairly and honestly, putting their investors’ interests first.

It is fairly simple: if S.E.C. officials find out that a company has done wrong they have the power to investigate, issue civil penalties, and refer the case to the Department of Justice for criminal prosecution. As many financial experts and white-collar crime lawyers have said, the S.E.C. has not fully utilized its authority, as demonstrated by the treatment of Dick Fuld and Jon Corzine.

The function of a financial institution is not merely to manage risk, but to act primarily as the steward of society’s assets and smart allocation of capital. We hope that the S.E.C will help re-examine the priorities of Too Big To Fail financial institutions. Finally, the current culture corrodes and disrupts sound business practices and stunts the rehabilitation of our current financial system. The S.E.C. is an imperfect vehicle (as evidenced by its lackluster approach to its duties leading up and during the financial crisis) but it’s the only vehicle we have. If they don’t do their job – who will?

Occupy the SEC is a group of concerned citizens, activists, and financial professionals with decades of collective experience working at many of the largest financial firms in the industry. Occupy the SEC filed a 325-page comment letter on the Volcker Rule NPR, which is available at http://occupythesec.org.

Recovery begins when addiction ends: an open letter to Jamie Dimon (#OWS)

Posted here on Naked Capitalism, written by the Alternative Banking group of Occupy Wall Street.

Please spread widely!

Who wants Jamie Dimon’s job?

It’s Jamie Dimon day for me today, I’ve offered to write a first draft of a Alternative Banking piece on the JP Morgan $2,000,000,000 “hedging loss” that he announced last week and which resulted in a 12% stock price loss in the past 5 trading days. There are many sordid details to wade through to prepare, but here’s the question I’d like you to think about for a minute.

Who would want to take that job once he resigns or gets booted?

I’m thinking the world is divided into people who are realistic about how ridiculously large and unmanageable any too-big-to-fail bank actually is, and the psychopaths that think they are the guy who can tame the beast. Jamie Dimon was definitely one of the most psychopathic of the original crowd of CEO’s left over from before the credit crisis, and honestly he played his part so well it was amazing. It didn’t hurt that JP Morgan was never the worst example of any kind of underhanded and outrageous risk-taking, until now.

For example: Dimon consistently and vehemently complained about any regulation as “strangulation” for his industry, and as anti-american. He was so adamant that people (read: regulators, politicians, and the Fed) took him very very seriously and he was on the verge of fatally weakening the Volcker Rule. We’ll see how that pans out now, but I’m hopeful for something a bit less pathetic.

Is there anyone left who can take that over? Who has the required psychopathic balls?

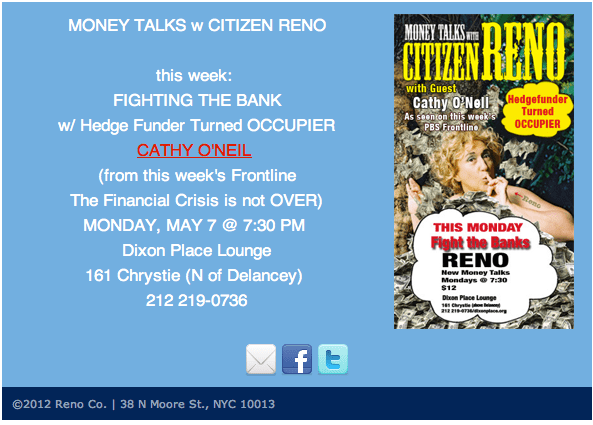

Performing tomorrow night with Reno

I’ll be in the Lower East Side tomorrow night, at the Dixon Place Lounge, talking finance with Reno, who some of you may know. Here’s more info:

Occupy Data!

My friend Suresh and I are thinking of starting a new working group for Occupy Wall Street, a kind of data science quant group.

One of his ideas: creating a value-added model for police in New York, just to demonstrate how dumb whole idea is. How many arrests above expected did each cop perform? [Related: you will be arrested if you bring a sharpie to the Bank of America Shareholder’s meeting in Charlotte!]

It’s going to be tough considering the fact that the crime reports are not publicly available. I guess we’d have to do it using Question, Stop, and Frisk data somehow. Maybe it could actually be useful and could highlight the most dangerous places to walk in the city.

Or I was thinking we could create a value-added model for campaign contributions, something like trying to measure how much influence you actually buy with your money (beyond the expected). It answers the age-old question, which super-PACs give you the best bang for your buck?

Please tell me if you can think of other good modeling ideas! Feel free to include non-ironic modeling ideas.

The student debt crisis

A few weeks ago I wrote about the higher education bubble that I saw at the individual level. This is the idea that, for a given student trying to decide whether or not to take on more loans to go to school, it’s essentially a no-brainer; it’s a cultural given that a college education pays off, statistically speaking, even if in a specific case it doesn’t.

As always, however, the situation at the individual level (a student going into debt) is informed by the overall system. Today I want to write a bit more about how this system got so out of whack.

I’ll actually write about a series of theories of mine, so please tell me if you think I’ve got the facts wrong. I don’t want to claim these are new ideas, but rather a storytelling version of a common understanding of how this all went down. In this case, it’s a story about money and perceived risk, no too dissimilar from the housing crisis.

Before I get into the details of the theory, let me throw in that the Ivy Leagues like Harvard and Princeton have always been super expensive, but that’s part and parcel of their brand. It’s actually intentional, they wouldn’t have it any other way, because part of being elite is being out of control expensive (although it needs to be said that their financial aid to poor kids is exemplary). In other words, I don’t think my theory is going to work on super elite colleges, but that’s fine because most people don’t attend those colleges.

And college always cost some money, although some state schools were really quite reasonable back in the day. It’s just a question of how long after college someone would have to wait or work before their student debts would be gone so they could move on with their lives and think about buying a house (more on that connection below).

Okay, with those disclaimers, let me get started. Namely, it’s all about bankruptcy laws. I know that sounds unbelievable, but it’s really true. From Justin Pope:

Until 1976, all education loans were dischargeable in bankruptcy. That year Congress began requiring borrowers to wait at least five years before they could discharge federal student loans. Since 1998, borrowers have been unable ever to discharge federal student loans, and in 2005 the then-Republican-controlled Congress made private loans almost impossible to discharge.

Why does this matter?

Because it meant that people lending to students wouldn’t need to worry about getting their money back. That sets up a perverse system where young people who are not creditworthy can take on piles of debt.

On the one hand, it’s good for students to be able to finance their education- you wouldn’t want young poor kids to not attend colleges at all for want of enough funding.

On the other hand, it meant that the tuition and fees could essentially rise without pause, since there was nothing to force them back- no supply vs. demand situation.

This is especially true because students aren’t told and do not generally “shop around” for a good deal in college, and moreover colleges are incredibly underhanded about making their tuition and fees clear (I am giving the CFPB about 3 more months to force them to present packages in a standard form before I really start complaining).

Another example: Pell Grants. These are grants given to poor kids to go to college, and they aren’t loans – the government pays them straight to the college. But the colleges have not really made it easier for kids to go to college because of this free money, but rather have raised their tuitions by the amount of the expected Pell Grant. Some colleges are better at getting Pell Grant money than others, and in particular for-profit colleges get 7 out of 10 such grants.

[Speaking of for-profit colleges, how are they allowed to exist? They are the worst of the worst and in particular have outrageous practices in terms of disclosing fees and tuitions, giving commissions to financial aid officers who then urge students to lie on their financial aid forms. Not to mention providing questionable educations.]

I hope it’s not too hard now to understand why student debt has just surpassed $1,000,000,000,000 in this country, ahead of credit cards. On the banker side of the room, these student debts are being bundled up and securitized and sold to investors just like old mortgage-backed securities (which, as you recall, couldn’t fail because the housing market always goes up) who are being told there’s very little risk since students can’t discharge student debt through bankruptcy. There’s a strong analogy with the previous housing bubble and the current education bubble: even ignoring the individual’s goal of becoming an educated citizen and qualified worker, there’s the demand side from the banking system itself which feeds on the fees of securitized products that seem riskless.

But the cost to those individual borrowers is heavy; we have a system whereby young people are being saddled with enormous and unreasonable debt in order to even qualify as a worker, and they are carrying it around like a noose. It is, for example, one thing preventing the housing market from recovering, because the generation of young people who should be buying a house right now is instead still trying to pay off student loans.

What should we do about this?

First of all, let’s focus on the culture of education and how we think about it. Is it a certification process that people should pay for? Or is it a part of what we offer our citizens as their right?

If the latter, it’s time we rethink why state schools should exist, and fund them accordingly, rather than removing more and more funding while expecting them to uphold their state-school mandates. I went to UC Berkeley in the early 1990’s and it was completely awesome, but it’s getting more and more squeezed by the state of California, which is forcing it to choose between becoming a bad school and becoming a private institution. And yes, that means taxpayer money going towards the investment of broad education rather than to banker bailouts.

Second of all, let’s rethink the bankruptcy laws. At the very least for private student debt. For public student debt it also needs to be negotiable in certain circumstances. We need to get the colleges themselves to lower their fees enough that the debt loads are tolerable.

Finally, let’s rethink how much to expect someone to pay down their debt depending on their salary. From Bloomberg:

The second crucial step is to mitigate the burdens of already distressed borrowers. The Obama administration has made progress, for instance by proposing an initiative that would let some students limit their loan repayments to 10 percent of their discretionary incomes next year and would forgive balances after two decades. Private lenders should be given incentives to offer more modifications and flexible payment options.

Yes, this means that some of those securitized student debt loans will default, just like mortgages. And that will mean that already undercapitalized banks will be even more so, because they’ve been taking risky bets yet again, and Sallie Mae will be up Shit’s Creek. But the alternative, of a continuing debt trap for young people, is an even worse alternative.

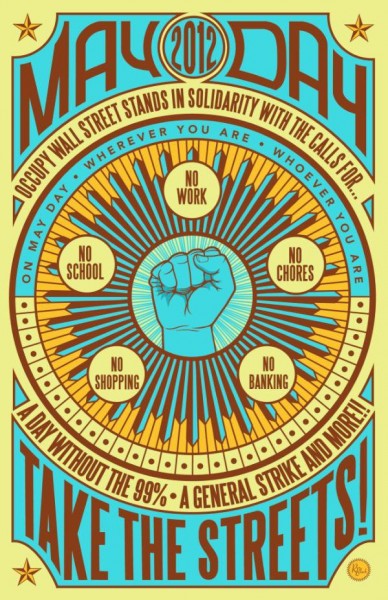

It’s May Day!

I’m leaving work early today to join the May Day Celebration with Occupy (May Day playlist here).

Bloomberg knows about it, and so does the Wall Street Journal, and if you do a search on the New York Times you can even find something there.

I’ll be participating in the Free University today, talking about “Weapons of Math Destruction” from 2-3 in Madison Square Park, and then meeting my kids there after school for a march down to Union Square with the signs we made in Alt Banking on Sunday. Woohoo!

Oh, and the PBS Frontline special on politics, banks, and Occupy that I’m in (Episodes 3 and 4) airs on PBS tonight at 10pm. Please watch it and tell me what you think, or watch it online here tomorrow, because I made a deal with myself that I’d do it as honestly as I could but never watch it myself. There are outtakes here from my interview that I consider unwatchable as well but people seem to like.

Conclusion (#OWS)

This is the final part of a four-part essay that was proposed by Cathy O’Neil, a facilitator of the Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking Working Group, and written by Morgan Sandquist, a participant in the Working Group. The first three parts are here, here, and here. Crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

Still sitting in our breakfast nook, with the banking industry squinting grumpily back at us through the glare of the morning sun on the perfectly polished granite table top, we can sit back, rest our hands on the table, and rather than shouting what it expects to hear, playing our part in the script of codependency, we can speak, without pleading or rancor, the truths that are beyond the script.

Rather than repeating once again our expectations and the banking industry’s failure to meet them, rather than pleading with it to live up to its obligations and do what’s fair, we can speak of the mundane practical details of our life and our children’s lives after its eventual demise, of the specific process by which everything around us will be sold to pay the ruinous debts for which its insurance will prove woefully inadequate.

We can make of the inevitability something tangible, rather than a vague, abstract threat. We can catalog the likely disposition of all of the banking industry’s prized possessions and family heirlooms, the eventual owners of everything it values. We won’t engage in a debate over whether the inevitable will occur, nor will we revel in the justice of it, because we’ll all suffer.

The banking industry must take responsibility for the laws it has broken and make appropriate restitution, not because we’re vengeful, but because the connection between choices and consequences so necessary to any successful relationship must be restored. And as long as the banking industry is adamant that it can’t or won’t change, and given the suffering that will follow from that refusal, we have no choice but to regretfully plan for our own and our children’s well-being to the extent we can. Should it accuse us of betrayal, our response is that the first step toward an alternative is one the banking industry must take.

I would have liked to title this section of this essay “Recovery,” but I’m not in the position to do that. I can’t speak to outcomes, only to process. I’m neither imaginative nor prescient enough to suggest what the successful results of our efforts might look like, but I have some idea of how those efforts should be undertaken.

I could use the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous (“We admitted we were powerless over debt–that our industry had become unmanageable,” and so on) to describe what might follow from the banking industry taking that first step, but that would be a too literal extension of the metaphor.

The truth is that history offers no examples of the sort of transformation that’s now needed. Though addiction and recovery may offer greater insight into our predicament than yet another political or economic analysis, there’s no reason to believe that the situation will stick to that metaphor as it evolves, even as we proceed with what is essentially an intervention.

Gil Scott-Heron famously said, “the revolution will not be televised.” I take this to mean that any real, fundamental change to the workings of our society, won’t be an entertainment offered by revolutionaries to the rest of us. It won’t be achieved if we sit home waiting for someone on television, or now the Internet, to present us with a number we can call or text, a petition we can sign, or a ballot we can fill out. Our opinions will effect nothing, and our agreement is neither solicited nor required.

I offer this essay not to start another in the endless string of conversations about what is to be done, but to prompt you to do it, whatever it will be, even if what you will do proves that everything I’ve written here it categorically incorrect. I also offer this as an explanation of why I’m doing what I’m doing.

Among other things, I’m working with several participants in the Alternative Banking Working Group on a Web application that will allow people in New York City (and, later, the rest of the country) to find credit unions for which they’re eligible (something that turns out to be far more complicated than you might expect). This will facilitate the return of money from banks, where it functions as an addictive substance, to community ownership, where it functions as a tool in the business of that community.

I do this on your behalf as well as my own, but not in your place. What else will be done and what will come of it will be the result of what you do. The Occupy Wall Street movement is entirely open and will become no more or less than what we make of it. Tomorrow’s May Day events will provide people with the chance to find out for themselves what that movement is, how they can become involved, and what it will become.

With events in more than 115 American cities and many more around the world, you should be able to find an event near you (if you’re in New York City, you can even hear more about the prank played on MF Global by the banks).

Take the day off and meet the people with whom you share this struggle, whether you’ve agreed to it or not. If the movement isn’t what you want it to be, it’s incumbent upon you to transform it as necessary. You can sit home waiting for a movement that checks all your boxes to somehow arise and solicit your participation, but so passive an approach is unlikely to accomplish much.

Let’s all get together on May 1st and see how much we can accomplish in this American Spring.

An Intervention (#OWS)

This is the third part of a four-part essay that was proposed by Cathy O’Neil, a facilitator of the Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking Working Group, and written by Morgan Sandquist, a participant in the Working Group. The first part is here and the second part is here. Crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

What are we to do with our banking industry, sitting there at the kitchen table in its underwear, drumming on the table with one hand and scratching its increasingly coarse chin with the other in an impossibly syncopated rhythm, letting fly a dizzying stream of assurances, justifications, and accusations, and generally spoiling for a fight that can only be avoided by complete and enthusiastic agreement with a narrative that can be very difficult to follow, let alone make sense of?

Because this is our kitchen too, we have our legal and moral rights. We would be well within those rights to respond to its nonsense with far more coherent and sweeping condemnations of our own. Throwing the bum out in its underwear without so much as a cup of coffee, taking the children, and keeping our share of whatever might be left could certainly be justified.

Though the sense of release offered by those responses is tempting, they’re not likely to be of any practical use. We can’t win an argument with an irrational person, and our share of an insolvent industry is likely to be very little–certainly not enough to feed the children. We have to recognize the hard truth of our implication in the banking industry and its addiction.

This doesn’t mean that we’re responsible for the addiction and its consequences, or that we can make the choice not to continue that addiction on our own, but it does mean that the problem won’t be constructively resolved without our efforts. To the extent that denial is about obscuring the connection between decisions and results, the most effective means of undermining denial is to clarify that connection, and the process of doing that is intervention.

Whether or not its participants are thinking in these terms, Occupy Wall Street, to the extent that it can coherently be referred to as an entity, is in many respects functioning as an intervention into the banking industry’s increasingly untenable addiction to money and debt.

The movement’s core values of transparency, sustainability, and nonviolence reflect the clarity, patience, and compassion needed for an effective intervention.

This is not to say that all of the efforts directed at banks by the movement have been magnanimous or constructive. We have to remember the terrible suffering that has been inflicted upon so many and offer that clarity, patience, and compassion not just to the addict, but also to ourselves as intervenors and to everyone who has been affected by the banking industry.

On the whole, I have been deeply heartened by how this movement has evolved over the last seven months, and though intervention isn’t the easiest or most promising process, it’s one I recognize and know can work (in stark contrast to political revolution). From the beginning, the Occupiers have shown a fearless, poignant spontaneity that’s available only beyond the addiction-centered dynamic of denial, and the banking industry, its enablers, and others still within that dynamic of denial (which, to be fair, has included most of us at one point or another) have responded as would be expected.

The determination and wisdom granted to those who see more clearly is profoundly threatening to those seeking to maintain denial, though of course they wouldn’t be able to say quite why.

The initial objections from the press that Occupy Wall Street was making no demands could be seen as an enabler’s yearning for symptoms that can be isolated and addressed, without admitting to or addressing the addiction from which they arise. To keep calmly and patiently pointing to that underlying cause is simultaneously incomprehensible and maddening to those trapped within denial, and their responses have run the gamut from smug certainty that nothing could possibly be wrong to whistling past the graveyard to ill-conceived and unjustified violence. And the Occupiers’ patience, diligence, and good nature in the face of that decidedly ill will is as textbook an illustration of the process of intervention as we’re likely to see.

It would be all too easy to remain passive in the face of our increasingly delusional, erratic, and combative banking industry. Surely there must be a more palatable alternative to undermining the continued functioning of the complex and highly evolved process that is the core of our economy.

If we force it to rehabilitate, what will happen during that process? Will our economy collapse? When its rehabilitation is complete, will the banking industry be able to function as well as it once did? Or as the banking industry’s enablers would have it: Any attempts to regulate the banking industry will only harm it, making it less effective to all of our detriment; these banks are too important a part of our economy to be allowed to fail; and bankers must continue to receive bonuses for banks to remain competitive.

It’s true that the banking industry has seized upon the process that’s the basis of our economic survival, and that attempts to address the problems of the banking industry cannot be undertaken lightly. But it’s also true that the banking industry has perverted that process, and that attempts to address that won’t prevent our return to some fantasy of efficiency and plenty, though they might prevent the otherwise inevitable, tragic end of the current trajectory left unchecked.

Whatever happens while the banking industry is rehabilitated is unlikely to be worse than what will happen as it continues to indulge in its addiction unaddressed, and it’s unlikely to function any worse upon the completion of its rehabilitation than it is now. As Charles Eisenstein puts it, “any efforts we make today to ‘raise bottom’ for our collectively addicted civilization–any efforts we make to protect or reclaim social, natural, or spiritual capital–will both hasten and ameliorate the crisis.”

Once an addict has reached the point in his or her descent where an intervention is necessary, there’s no realistic possibility of a return to some pre-addiction Golden Age. The apparent paradox that an addict’s life must be destroyed to save it is, stated in those terms, false. The addict’s life only appears to be as yet undestroyed through the lens of denial, and a future life without substance abuse or consequences is an illusion.

But the more gently stated paradox that intervention will cause the addict suffering in the short term to help him or her in the long term is accurate. There are, however, deeper, more intractable paradoxes, and they are those of the psychology of addiction. The process of intervention is often crucial to an addict’s entering rehab and beginning recovery, yet only the addict can decide to enter rehab.

The addict must understand the damage he or she has done in order to stop using but mustn’t succumb to shame, which would simply cause a retreat to the substance. The addict must admit that he or she is powerless over the substance and that life has become unmanageable, but mustn’t surrender to hopelessness and despair, which would sap the considerable motivation needed in the process of recovery. An intervenor must do something, but there’s nothing that can be done. There is no single act, no grand gesture or magic bullet, that can accomplish anything meaningful or lasting. Intervention is a long, unpredictable process requiring superhuman compassion and patience of everyone involved. Prior training or practice in commitment to a process without regard to the outcome of that process is invaluable.

Yes, we can answer the banking industry’s petulant invective in kind, but that won’t fix the problem; the industry will become more defensive and reckless, and we probably wouldn’t end up feeling any better anyway. Our encyclopedic harangue would be cogent, compelling, and convince our friends in the retelling, but no matter how loud we shout it over the banking industry’s coffee cup into that sullen, bloodshot face, it will simply be brushed aside with the wave of a shaky hand and a hoarse grumble, or, worse, it will hit home, and rattled, the banking industry will glare at us and we’ll know that tonight will bring another nihilistic binge of leverage and derivatives, and maybe this time there will be no tomorrow morning. The industry will tell us that we don’t understand, that the pressure it’s under is unimaginable, that life is grim, and that even though it can’t fix that, it should be thanked for what it has accomplished, and that that’s the best it can do. What more could we want? What more could it do? And we can only sigh and shake our head, because we know the simple, honest answer would just fall on deaf ears, and even if it were understood and accepted, the broken soul sitting across the table is in no shape to do anything constructive.

The confrontations shown on television or in the movies, or that you have perhaps participated in yourself, are just part of the larger process of intervention, but they illustrate the themes that inform that larger process. Those themes can best be summarized as connection: the connection between the addict’s choices and the suffering of the addict and those who are around him or her; the connection between addiction and the addict’s choices; and the unbreakable, always available connection between the addict and the intervenors.

Where denial seeks to divide and conquer, intervention seeks to unify and transcend. Intervention doesn’t respond to denial on denial’s terms, but rather reflects reality as it is. It doesn’t engage in the petty distractions of accusations and recriminations, nor does it seek escape from the addict and his or her problems. Intervention shows the addict his or her choices as they’re made, how those choices are determined by addiction, and the consequences that follow from those choices, but it also shows the redemption that’s always available despite those choices and their consequences.

Where denial is deceptive, impulsive, and selfish, intervention is clear, patient, and compassionate. Intervention finally presents the addict with an unavoidable choice between continued deluded suffering and real, sustainable sanity. The addict may or may not respond positively to that choice, but it must continually be presented on the same terms until the addict surrenders his or her denial.

And to induce that surrender, it’s crucial that the addict be offered an alternative to his or her addiction, whether it’s formal rehab, a twelve-step program, methadone, or a recovery dog. It’s important to recognize that even before the addict became physically or emotionally dependent on the substance, that substance met an otherwise unmet need, and leaving it unmet will lead only to relapse.

Tomorrow: Conclusion

The Addiction (#OWS)

This is the second part of a four-part essay that was proposed by Cathy O’Neil, a facilitator of the Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking Working Group, and written by Morgan Sandquist, a participant in the Working Group. The first part is here. Crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

Is it fair to say that because the quality of the denial surrounding the banking industry’s problems is so similar to that of the denial surrounding addiction, that addiction is therefore the root of those problems and our ongoing failure to adequately address them? Perhaps not, but others have come to describe money, debt, and banking as something very much like addiction for entirely different, and far better argued, reasons.

In Debt: The First Five Thousand Years, David Graeber looks deeply into the anthropological record and finds that money and debt, and, by extension, banking, are all essentially the same thing, and they’re not what most of us understand them to be. Money is certainly not simply the objective store of value and medium of exchange that economists would have us believe it is. Because money is created as debt, its use to finance productive activity means that that activity, whatever it is, must then generate interest to be returned to money’s creators in addition to the money lent.

This has given rise to an industry, even a class of people, that derives its livelihood not from any productive activity of its own, but merely from having money. In Sacred Economics, Charles Eisenstein takes this a step further to show that this overhead cost inherent in all monetarily denominated activities means that the value represented by money must always grow. There is no logical end to what must be monetized–natural resources, ideas, time. Nothing can remain unowned and clear of liens, and that will eventually consume any finite realm:

The dynamics of usury-money are addiction dynamics, requiring an ever-greater dose (of the commons) to maintain normality, converting more and more of the basis of well-being into money for a fix. If you have an addict friend, it won’t do any good to give her “help” of the usual kind, such as money, a car to replace the one she crashed, or a job to replace the one she lost. All of those resources will just go down the black hole of addiction. So too it is with our politicians’ efforts to prolong the age of growth.

I don’t hope to make in a couple of paragraphs the full case that those two authors have made over hundreds of pages, so I’ll just assert it to have been compellingly made: namely, that money, debt, and banking have gone from being a tool that we might use to ease social activities to being the purpose of those activities. They have become an addiction, and because they’re an addiction, all of us who are touched by them have developed a rich and pervasive denial of this fact, its history, and its consequences.

In practical terms, what do we gain by perceiving money, debt, and banking as an addiction and the discourse around them as denial? Speaking for myself, it helps me understand the otherwise inexplicable irrationality behind our ongoing financial decline. I can imagine no other explanation for so much of what we’ve seen in the last few years: the failures to properly address the mortgage and subsequent foreclosure crises; the criminal activities of banks, hedge funds, and ratings agencies, and the spiral of consumer indebtedness; the deeply emotional and often militarized response to people sleeping in an otherwise unused square of concrete in a nocturnally unpopulated commercial district; and, most of all, the general populace’s willing acquiescence to all of this.

It appears only that banking must continue as it is, undisturbed, and nothing must disrupt the use and abuse of debt and money. Though an explanation for the full range of symptoms of the banking crisis, or for the full range of symptoms of any addiction, risks being reductive, without some causal dynamic behind these symptoms, there can be no effective response to them. To prevent something from happening, a cause must be identified and addressed.

Understanding money, debt, and banking as addiction also helps me trust myself and seek a constructive approach to the daunting task of resolving this crisis. As anyone who has ever had to face the full force of shared social and familial evasion can attest, the temptation to surrender to that alternate reality despite his or her better judgment, if only for the sake of civil relations, can be overwhelming.

In the case of the banking industry, that evasion often comes in the form of expert opinion that seeks to persuade not through the substance of the discussion, but through a dependence on credentials and ad hominem dismissal. It’s invaluable to be reminded that such a surrender, regardless of expert arguments, will at best only defer the consequences that we fear. Asking ourselves if, at the addict’s eventual funeral, we’ll be comfortable that we did everything we could is a remarkable inducement to focus. It can also be a powerful inducement to anger, so the understanding that it’s really addiction and denial, not friends and family, that we’re fighting can provide a basis for the compassion we would need to constructively approach such an emotionally volatile undertaking.

Finally, this understanding helps me focus on the ultimate goal of any such effort, rather than becoming sidetracked by pointless diversions.

As I mentioned above, one strategy of denial is to hide the connection between the symptoms of addiction and their real cause. It allows the alcoholic to believe that his or her diabetes and other health issues are the result of poor diet and that his or her depression is genetic or the result of poor parenting. It’s not that an alcoholic necessarily consumes a model diet or was well reared, but addressing just those symptoms allows the alcoholic to keep drinking, and other symptoms will follow from that drinking.

Similarly, it’s not that banks don’t need to be better capitalized, but providing them with capital and liquidity alone allows banks to continue pursuing courses of action that are neither financially nor economically viable.

To effectively address addiction is to prevent further addictive use of the substance. Any effort directed at symptoms will, to the extent they’re effective, simply enable continued substance abuse. It’s only by understanding the nature and extent of denial, navigating its maze, and intervening directly in the use of the substance that one can hope to effectively address addiction, and even then, the odds aren’t in the addict’s favor. And only with a thorough understanding of this dynamic and all of its implications can we hope to intervene effectively in the banking crisis that as of now continues unabated.

Tomorrow: An Intervention

In Denial (#OWS)

This is the first part of a four-part essay that was proposed by Cathy O’Neil, a facilitator of the Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking Working Group, and written by Morgan Sandquist, a participant in the Working Group. Crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

The largest banks in America–Citibank, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and others–are probably insolvent. I learned of this from my companions in Occupy Wall Street’s Alternative Banking Working Group. It seems that, based on a host of legal and accounting irregularities, the banks have been able to conceal real and potential losses far larger than their capital reserves. But this has been difficult to confirm.

Isn’t that strange? Wouldn’t the possible insolvency of the core of our banking industry be a matter of nearly universal importance? Shouldn’t we be trying to figure out if this is in fact so, how it came to be, what we’re going to do about it, and how we can prevent its happening again?

Anyone investigating the true health of the banking industry, apparently including regulators, is faced with opacity, complexity, and even outright hostility that stymies all but the most savvy and persistent. Fortunately, people within OWS, including the Occupy the SEC Working Group, are that savvy and persistent. But the reaction of the industry and its partisans to such efforts has included the not-so-subtle suggestion that inquiring into the well-being of the banking industry will somehow cause problems to arise that wouldn’t otherwise exist if we would all just mind our own business.

This seems odd in an ostensibly objective and quantitative context like banking. Shouldn’t the truth be clearly visible in the accounting? Shouldn’t we all–borrowers, investors, depositors, and regulators–want to know exactly what’s going on?

As unexpected as such a visceral and irrational reaction to genuine, well-founded concern is from the supposedly rational realm of finance, that telltale blend of evasion, grandiosity, and superstition will be familiar to anyone who has ever confronted an addict about his or her addiction.

Denial is far more than an addict’s dismissal of the truth of his or her addiction; it’s collectively developed by the addict’s entire social sphere, and it takes many forms.

It might be helpful to imagine addiction and denial as intangible agents acting in a social context. Addiction’s agency is directed solely toward uninterrupted use of the addictive substance, and denial’s agency is directed solely toward ensuring that no one sees, understands, or limits addiction’s agency. Denial denies not just claims and assertions, it also denies access and insight into the reality of addiction. It denies that behavior is driven by addiction and that behavior’s consequences are the results of addiction. It denies the story of addiction and proposes an endless collection of counter-conspiracies.

It appears as those around the addict ignoring the addict’s use and the consequences of that use; as the narratives, tics, and habits through which the addict understands and acts out his or her use; and as the alternate version of reality that the addict and everyone around him or her shares in lieu of the reality of addiction. To paraphrase Baudelaire on the devil, denial’s best trick is to persuade us that addiction doesn’t exist.

No addiction could develop a more effective narrative of denial than the trade in exotic financial instruments that’s evolved over the last decade or so; no addiction could hope for more willing abettors than the financial press, regulators, and ratings agencies; and no addiction could depend on a more permissive enabler than the Federal Reserve Bank.

It’s difficult not to imagine the banking industry as jittery and unshaven, embarking on yet another unregulated derivative binge, telling us, its concerned partner, that we just wouldn’t understand what it’s like, how high the return can get, while its friends in the financial press and ratings agencies encourage it, scoffing at the very idea of risk.

And later that night, as it’s coming down, it’ll shout something at us about not really needing the $1.2 trillion in liquidity, but if the Fed’s offering, why not?, it’ll make the night that much better, only to face us the next morning, hungover and distractedly claiming none of it ever happened.

We’ll confront it with seemingly undeniable evidence of MERS, TARP, executive bonuses, and a ruined housing sector, and it’ll look betrayed, ask us how we could even say such a thing, and tell us that it’s none of our concern and that we just have to trust it, because the bills are paid, right? It’s not like it’s as bad as AIG or MF Global, it’ll say, which will lead to an impossible-to-follow tale of the prank it played on MF Global last night, and how that was like something that happened to Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers once, and ending with the declaration that the Fed and the SEC would never let anything bad happen to the Banking Industry.

And what choice do we have? Maybe it’s not that bad. After all, if the banks really were insolvent, there would’ve been something on the evening news.

Tomorrow: The Addiction

Occupy Wall Street isn’t dead

I went to New Jersey a couple of nights ago to talk about Occupy Wall Street and the Alternative Banking group to NJPPN, a network of politically aware and active citizens. They self-describe as non-partisan but there were quite a few NPR listeners in the audience, and in general they came across to me as very skeptical of the financial system. Or possibly they were just being polite.

One of the audience members expressed frustration that the Occupy movement has fizzled out. I guess I can understand why he may think so, because after Bloomberg cleared the Occupiers from Zuccotti Park it was obviously more difficult for people to know what the movement is up to. And what with the cold weather, many of the working groups, like Alternative Banking, were incubating ideas rather than staging street protests. Plus the movement is still less than a year old, and these things take some time to set up.

For him and for others like him, I’d like to point you to a few resources to which explain what Occupy has been up to and what it has in store:

- occupydidwhat.tumblr.com – a recently begun list of stuff that Occupy has accomplished. Cool idea.

- Occupy.com – a gorgeous new website of news for Occupy.

- The Center for Popular Economics is having a Summer Institute here at Columbia called Economics for the 99%.

- Lots of plans for May Day described here. See you there.

- As I’m sure you know, people are sleeping on Wall Street.

- Alt Banking’s blog is fairly regularly updated as well.

More to come. The hoodies are being shipped as I type.

#OWS update: looking for UX help

I’ve got three updates on Occupy, besides reminding people that the Alternative Banking Working Group meets every Sunday from 3-5pm at Columbia (room 1401 in the International Affairs Building at 118th and Amsterdam).

- Occupy.com has launched! This is a website set up by my friend David Sauvage, and it’s looking awesome and informative.

- The “find a Credit Union webapp” is looking for UX Designer help. I’ve written about this project before, but in a word we’re helping people figure out which credit unions they are eligible for, if any; the rules can get kind of tricky. We’ve got the basic ideas down but we’d love a thoughtful designer to come in, improve the user experience, and help create a appropriate Occupy look which also doesn’t scare away non-Occupy people. We also have a development team from ThoughtWorks helping us out, but it would be very helpful to have a New York- based developer to maintain the knowledge. The eligibility rules based on address (but not necessarily on zipcode or borough) are particularly hard (or interesting, depending on how nerdy you are).

- Not a strictly Occupy issue but did you hear the Vermont Senate has voted to end Corporate Personhood (hat tip reader G. Jones)? Move to Amend has spearheaded this effort. I love their motto: End Corporate Rule, Legalize Democracy. Read about the Vermont vote here.

Who is the market?

Oftentimes you’ll read an article in the middle of a market day about how “the market is responding” to the jobs report, or the manufacturing index, or sentiment reports. That kind of makes sense – it is shorthand for the fact that the people betting on the market are, as a group, reacting and changing their bets based on new news. If the expectation was for 200,000 jobs to be added but only 120,000 jobs were added, you’d expect disappointment and a drop in the S&P index.

Even so, this language is pretty confusing, since it’s certainly not true that everyone who invests in the market is doing this – most people with money in the market don’t do anything at all on a given day. Okay then, let’s interpret it as meaning something kind of reasonable like, “of those people who respond to this news by changing their bets, a majority of them are betting in one way which is moving the market.”

It still may not be true, since people who are seriously involved with the market typically don’t have the same expectations as what the official expectation report says – that report may have contained no surprising news at all, but one hedge fund liquidating their portfolio may be dominating the market. So even if there is a reasonable interpretation, the chances are it’s vapid.

Other times you’ll read an article, probably put out by Bloomberg, about how the market is “recalibrating,” or “taking stock” after a rise. This is where I get confused. It’s like I’m expected to imagine a huge man, hunched over thinking about what to do next.

But what does that really mean? As far as I can tell, nothing at all. There’s no man, there are no little men behind the wall representing this man, and everyone betting on the market is just doing their thing. It’s maybe just a way of writing a story because the journalist was told to write a story and the market wasn’t doing anything.

But lately I’m wondering if there’s something more to it. Why are journalists covering the market allowed, day after day, to write vapid articles about the market? What is it about using language like this that makes us comforted?

My guess is that people want there to be such a man, and moreover want him to be understandable and reasonable.

It’s primarily a question of control – control over our lives, as if we can say, as long as we kind of get his (the market’s) sentiments, we can avoid catastrophic risks. Like in those human nature tests where 85% of people consider themselves better than average drivers, we feel that we understand the market and so we’re covered and safe. Even when there’s plenty of evidence that we don’t actually understand the risks, we continue the market myth out of this need to feel in control.

I also think there’s another, secondary effect of this personification. Namely, we feel like the system is massive and powerful and there’s nothing we can do to affect it. It makes us passive.

My friend Hannah, who’s an anthropologist and whom I met through Occupy, likes to say to people, “that good idea you’ve had that someone should do? It’s your idea, and you should do it! There’s no Occupy elf that will go do it for you just because it’s a good idea.” I love that sentiment, and the idea of Occupy elves (why aren’t there Occupy elves?).

It makes me realize how much we expect other people to do stuff just because it’s a good idea, when in fact from experience we should have learned by now that the stuff that gets done by other people is usually because it’s a good idea for them. Stuff that’s a good idea for us, or for everyone, we should consider our personal responsibility. The market is certainly not looking out for us.

Who here reads Dutch? (#OWS)

Hey I was interviewed last week by the Belgian newspaper De Tijd about Occupy Wall Street and the Alternative Banking group. Here are pdf versions of the first page and the second page, but I wanted to show the picture too, event though this jpeg version isn’t good enough to read:

Vote with your wallet

Today we have a guest post from Elizabeth Friedrich, with whom I work on the Credit Union Findr webapp I blogged about here. Cross posted from Beyond the Bailout.

In 2008, America was in shock seeing the stock market crash, the housing market collapse, and a $12.8 trillion-dollar bailout of financial institutions many felt were responsible for the economic crash. We were paralyzed, unable to see past the madness and despair. At first, our national response was minimal. Americans had lost their homes, jobs, everything, and the anger was evident in the national mood. However, from that desperation and pain-came action and movement! People began to organize in order to decide their own fate, not leave it up to the 1% and/or a complacent government. Action came in many forms, marches in streets, letter-writing and media campaigns, peaceful occupation of public spaces, and of course “Move Your Money.”

The Move Your Money Project actually started several years ago, but had not gained significant momentum until last year, when consumers began to voice their anger and outrage at the very largest for-profit financial institutions, who had been bailed-out with billions in tax-payer dollars, and rather than using those funds to expand credit to communities in need, instead sat on this cheap money and tightened their lending standards. With historic low interest rates set and held by the Federal Reserve system, profit margins became slimmer and many banks responded by increasing their fees across the board, much to the ire of many fed-up consumers. This action was a catalyst to finally moved people to question the role of their so-called trusted financial institutions and on November 5 2011, over 600,000 people moved their money totaling $80 million dollars out of traditional banking institutions into credit unions and community banks across the country. In addition to that single day of action, over the last few years, over 4 million accounts have moved from the nation’s largest Wall Street banks according to Moebs Services, an economic research firm in Lake Bluff, IL. They also project an additional 12 million people will do the same in the next two years.

This mass-exodus from the big banks is by no means accidental and shows the overwhelming, yet untapped energy of the American people who have grown discouraged with a government that was unwilling or unable to enact true, meaningful financial reform. Many of their reasons for this are clear: consumers are looking for ethical practices, re-investment in local communities, fewer fees and more service, and the end of “Too Big to Fail” financial oligopolies. Naturally, people began focusing on credit unions and community development banks, institutions that have the public interest in mind and seek to strengthen local communities. At these community-focused institutions you actually know where you money goes and what is used for.

Convenience over accountability…

Our culture has taught us that convenience is primary tool when making decisions as opposed to accountability and fairness. Just as we make other choices; purchasing food, clothing, and transportation. Convenience is often the factor that carries the most weight in our decisions rather than ethics. This comes with many consequences – often at the expense of the environment and disadvantaged communities. Hopefully, in the future accountability and transparency will be a primary motivation for consumers when making financial decisions.

What to do?

Today we have a choice whether we know it or not. There is a parallel financial industry functioning on the fringe: Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), a national network community development banks, loan funds, and community development credit unions (CDCUs). These are institutions with a primary mission to strengthen vulnerable communities and invest locally. Banks and credit unions are regulated depository institutions; banks by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and credit unions by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA). Credit unions offer many of the same services as banks: mortgages, car loans, personal loans, small dollar loans, credit cards, savings/checking accounts, international money transfers, Individual Development Accounts (matched-savings accounts), retirement planning, financial literacy education and budgeting, affordable savings and checking accounts, and credit and debit cards with low minimum balances and flexible terms. They are not-for-profit financial institutions created to serve their local communities and members first. Unlike banks, which can serve any customer that walks in the door, credit unions are restricted to specific fields of membership.

This means that consumers have more options than ever with respect to their primary financial institutions, and a major selling-point for many is that the money they deposit in their credit union stays local within the specific field of membership. Rather than profiting shareholders, income earned at a credit union, dividends are returned in different forms from free services to better interest rates or to expand services in the community.

Making the choice to bank at a credit union or a community development bank creates a multiplier effect for the local communities being served, and ultimately in the entire the financial system. When you invest in a community development financial institution you are investing in job creation, building schools, developing housing and financing small businesses.

Some banks may be “too big to fail,” but consumers are waking up and realizing they have a choice where they put their money, and the impact that choice can have in their own communities. Rather than letting too big to fail institutions gamble away their hard-earned cash, people are choosing to exercise their power as consumers and speak with their wallet. In banking this means find the smart, responsible alternative for you, your family and your community, and community development banks and community development credit unions are a logical choice.

How informed does an opinion have to be before it’s taken seriously?

How informed should an opinion have to be before it’s taken seriously?

I’m kind of on one end of the spectrum here. I would argue that you only need to know enough to get it right.

The original power of Occupy for me is in the following sentiment: you don’t need to understand the system’s insides and outs in order to know the system is screwing you. Of course it’s a different thing to fix something, but let’s leave that aside for the moment.

So, if you are a student with $80,000 in loans, a degree, and no job prospects, and all your friends are in the same or similar situations, then you can fairly say that the system is broken. And you’d have a powerful argument. The beauty of this argument, in fact, is that you and your friends provides living examples of how the system is broken, and defies all expert opinion to the contrary.

And one thing that we have had enough of lately is expert opinion.

This question came up at a recent Occupy Wall Street Alternative Banking group meeting, and not for the first time. The context was the collapse of MF Global, and we were talking about tri-party repos, which have intermediaries, and (maybe) fiduciary duties, and various questions arose over the legal issues as well as the question of whether Corzine et al had yet been asked these questions by Congress.

The details don’t matter. The point is, it’s complicated, and the question came up whether we had to know absolutely everything in order to be seen as asking an informed opinion and in order to be taken seriously.

Now, it’s a good idea for us to know the basics: the parties involved, their relationship to each other, and especially their individual incentives. But on the question of knowing if a specific question has been asked before, I think that doesn’t really matter. The truth is, we are some of the wonkier people in financial matters, and if we don’t know about it, then probably most people don’t.

And moreover, since we are trying to figure out how to represent the average person in such situations, that’s a good enough test. In fact, even if a question has been asked, if it hasn’t been adequately answered for the sake of the 99%, it’s still fine to ask and ask again until we have a satisfactory answer.

I’m all for being informed myself, and I like informed debates, but I don’t want to get stuck in some “cult of expertise”, where I think nobody is allowed to have an opinion unless they are incredibly well versed in something, especially when the underlying issue is actually one of ethics and justice.

Think about it: such thinking gives experts an incentive to make things more complicated in order to exclude non-experts. In fact I’d argue that such a “cult of expertise” incentive does in fact exist, has existed for some time, and the result is our financial system, tax system, and legal system.

It’s bullshit. We need to allow people who know enough to get it right, and have skin in the game, to enter the debate, and be heard, even if they don’t know the intricacies of the legal issues etc.. Those intricacies, likelier than not, have been partially put in there to confuse the very people the system was putatively set up to serve.

On NPR’s Morning Edition (#OWS)

The Alternative Banking group was on NPR’s Morning Edition with Margot Adler today.

Here’s a recording of the piece.

Bloomberg joins Occupy Wall Street

Yesterday I was astounded to read this article in Bloomberg, explaining how the debt collectors hired by the Department of Education have been illegally screwing people to the ground on their debt. This could have come straight out of an #OWS Alternative Banking meeting. From the article:

Under Education Department contracts, collection companies “rehabilitate” a defaulted loan by getting a borrower to make nine payments in 10 months. If they succeed, they reap a jackpot: a commission equal to as much as 16 percent of the entire loan amount, or $3,200 on a $20,000 loan.

Incentive Pressure

These companies receive that fee only if borrowers make a minimum payment of 0.75 percent to 1.25 percent of the loan each month, depending on its size. For example, a $20,000 loan would require payments of about $200 a month. If the payment falls below that figure, the collector receives an administrative fee of $150.

That differential provides an incentive for collectors to insist on the minimum payment and fail to reveal when borrowers are eligible for a more affordable schedule, according to Loonin, the attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, which is representing borrowers in the Washington talks with the Education Department

Here’s a closeup of Pioneer Credit Recovery, one of the debt collection agencies in contract with the U.S. Education Department. From the Bloomberg article:

Pioneer maintained a “boiler room” environment, with high turnover among those who didn’t perform, said Joshua Kehoe, a former collector. Kehoe worked in Batavia, New York, from July 2006 through October 2008 after managing a pizza stand at a theme park.

Pioneer rewarded collectors with $100 restaurant gift cards, a $500 mahogany jewelry box, televisions and a trip to the Dominican Republic, according to Kehoe, who said he earned $9.60 an hour before the incentives.

It would be “a cold day in Hades” before collectors would tell borrowers about options with lower payments, according to Kehoe, who said “rehab cash was king.” The company pushed collectors to sign borrowers up for the rehabilitation plans, which often required payments equal to 1.25 percent of their loan amount monthly, he said.

Just in case you think student debt is someone else’s problem, read this post from ZeroHedge from a couple of days ago. In it, Tyler Durden throws down two statistics we might want to keep in mind:

- … of the $1 trillion + in student debt outstanding, “as many as 27% of all student loan borrowers are more than 30 days past due.” In other words at least $270 billion in student loans are no longer current, and

- … the unemployment for 18-24 year olds is 46%. Yup: 46%.

When you throw in that student debt cannot be expelled through bankruptcy, you have a major problem for young people. And that means a major problem for all of us.

Random stuff, some good some bad

- In case you didn’t hear, Obama didn’t nominate Larry Summers to head the World Bank. This goes in the category of good news in the sense that expectations were so low that this seems like a close call. But I guess it’s bad news that expectations have gotten so low.

- Am I the only person who always thinks of tapioca when I hear the word “mediocre”?

- There are lots of actions going on in Occupy Wall Street, part of the Spring Resistance. It’s going to be an exciting May Day, what are you plans?

- Did you hear that New Jersey was somehow calculated to be the country’s least corrupt state? This Bloomberg article convincingly blows away the methodology that came to that conclusion. In particular, as part of the methodology they asked questions about levels of transparency and other things to people working in New Jersey League of Municipalities (NJLM). A bit of googling brings up this article from nj.com, exposing that NJLM clearly have incentives to want the state government to look good: it consists of “… more than 13,000 elected and appointed municipal officials — including 560 mayors — as members… its 17 employees are members of the Public Employees’ Retirement System, and 16 percent of its budget comes from taxpayer funds in the form of dues from each municipality.” Guess what NJLM said? That New Jersey is wonderfully transparent. And guess what else? The resulting report is front and center on their webpage. By the way, NJLM was sued by Fair Share Housing to open up their documents to the public, and they lost. So they have a thing about transparency. And just to be clear, the questions for deciding whether a given state is corrupt could have been along the lines whether the accounting methods for the state pension funds are available on the web and searchable on the state government’s website.

- If you know of examples of so-called quantitative models that are fundamentally flawed and/or politically motivated like this, please tell me about them! I enjoy tearing apart such models.

- The Dallas Fed has called for an end to too-big-to-fail banks. Mmmhmmm. I love it when someone uses the phrase, “Aspiring politicians in this audience do not have to be part of the Occupy Wall Street movement, or be advocates for the Tea Party, to recognize that government-assisted bailouts of reckless financial institutions are sociologically and politically offensive”.

- Volcker says more reforms are needed in finance and government. Can we start listening to this guy now that we broke up with Summers? Please?