Archive

How to be a pickup artist, Silicon Valley style

You know that feeling you get when you’re reading an disembodied article on the web and it’s just so ridiculous, you get the creeping sensation that it’s either from The Onion or the Borowitz Report?

That is, I would suggest, how you’re going to feel when you read this article about a school for Silicon Valley style entrepreneurship (hat tip Peter Woit). Even just the name of the school – the Draper University of Heroes – feels like an Onion article, never mind the visuals:

So, what do these young people learn do to become douchebag heros? Here’s what:

- They pledge allegiance every morning to their personal brands,

- They submit to a full two days of coding and excel lessons,

- Then they get down to the real work of sun tanning by the pool and go-kart racing,

- They hang out with VC Tim Draper, an investor in Tesla (the new conspicuous consumption choice among pseudo-progressive capitalists, as I learned at FOO),

- They read books, or at least they own books, including Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, The Wall Street MBA, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead,

- and all this for just $9,500 for an eight week program!

How does it end? From the article:

In lieu of diplomas, Draper U. students receive masks and capes printed with their superhero nicknames and are instructed to jump on each of a series of three small trampolines placed in a line in front of them. While bouncing from trampoline to trampoline, they’re told to shout, “Up, up, and away!” Then they assemble for a group photo.

“The world needs more heroes,” Draper says. “And it just got 40 more of them!”

Here’s the thing. It’s no accident that there are way more men than women here. This school is very similar in design and intent to the society built by Neil Strauss, who wrote The Game and taught a bunch of guys how to pick up “hot” women for sex – Aunt Pythia discussed it here.

Why do I say that? Because it’s fundamentally a confidence-boosting ritual, where a bunch of guys convince themselves that their prospects are good, their goals are attainable, their narcissistic world view is honorable, and it’s just a question of acquiring the right magic tricks to entrap their prey. It just happens to be about money instead of sex in this case.

There is a difference, of course. Whereas the pick up artists only needed to trick drunk women for a few hours in order to sleep with them, these “Silicon Valley Heroes” have to trick way more people for way longer that they should get investment. That doesn’t make it impossible for something like this to work, though, just harder.

New schwag for the Stacks Project

This just in from zazzle.com: Stacks Project cups and shirts, to celebrate the recent upgrade on Stacks Project viz.

An unflattering yet adorable picture of both me and Johan in Stacks Project t-shirts, new and old. Unfortunately the colors came out too light. You can see we’re both instructing our 11-year-old on how to take a picture and our 4-year-old is squeezing in too. He’s not shy.

Radhika Nagpal is a role model for fun people everywhere

Can I hear an amen for Radhika Nagpal, the brave woman who explained to the world recently how she lived through being a tenure-track professor at Harvard without losing her soul?

You should really read Nagpal’s guest blogpost from Scientific American (hat tip Ken Ribet) yourself, but here’s just a sneak preview, namely her check list of survival tactics that she describes in more detail later in the piece:

- I decided that this is a 7-year postdoc.

- I stopped taking advice.

- I created a “feelgood” email folder.

- I work fixed hours and in fixed amounts.

- I try to be the best “whole” person I can.

- I found real friends.

- I have fun “now”.

I really love this list, especially the “stop taking advice” part. I can’t tell you how much crap advice you get when you’re a tenure-track woman in a technical field. Nagpal was totally right to decide to ignore it, and I wish I’d taken her advice to ignore people’s advice, even though that sounds like a logical contradiction.

What I like the most about her list was her insistence on being a whole person and having fun – I have definitely had those rules since forever, and I didn’t have to make them explicit, I just thought of them as obvious, although maybe it was for me because my alternative was truly dark.

It’s just amazing how often people are willing to make themselves miserable and delay their lives when they’re going for something ambitious. For some reason, they argue, they’ll get there faster if they’re utterly submissive to the perceived expectations.

What bullshit! Why would anyone be more efficient at learning, at producing, or at creating when they’re sleep-deprived and oppressed? I don’t get it. I know this sounds like a matter of opinion but I’m super sure there’ll be some study coming out describing the cognitive bias which makes people believe this particular piece of baloney.

Here’s some advice: go get laid, people, or whatever it is that you really enjoy, and then have a really good night’s sleep, and you’ll feel much more creative in the morning. Hell, you might even think of something during the night – all my good ideas come to me when I’m asleep.

Even though her description of tenure-track life resonates with me, this problem, of individuals needlessly sacrificing their quality of life, isn’t confined to academia by any means. For example I certainly saw a lot of it at D.E. Shaw as well.

In fact I think it happens anywhere where there’s an intense environment of expectation, with some kind of incredibly slow-moving weeding process – academia has tenure, D.E. Shaw has “who gets to be a Managing Director”. People spend months or even years in near-paralysis wondering if their superiors think they’re measuring up. Gross!

Ultimately it happens to someone when they start believing in the system. Conversely the only way to avoid that kind of oppression is to live your life in denial of the system, which is what Nagpal achieved by insisting on thinking of her tenure-track job as having no particular goal.

Which didn’t mean she didn’t work hard and get her personal goals done, and I have tremendous respect for her work ethic and drive. I’m not suggesting that we all get high-powered positions and then start slacking. But we have to retain our humanity above all.

Bottomline, let’s perfect the art of ignoring the system when it’s oppressive, since it’s a useful survival tactic, and also intrinsically changes the system in a positive way by undermining it. Plus it’s way more fun.

THIS REQUIRES YOUR MOCKERY

My title today is the subject line of a message I received from my buddy Jordan Ellenberg. Thanks for making things so easy for me to blog this morning, Jordan!

So here’s the subject: a Silicon Valley entrepreneur’s self-help book, including advice on how to quantify and measure your sex life, among other things – every other thing, in fact.

Just in case you’ve missed it, there’s a movement afoot among certain people to collect data about themselves on the level of heart rate, daily exercise and eating patterns, and the like, with the goal of self-improvement.

It’s got a name – the Quantified Self movement – and if I haven’t mentioned it before, it’s because honestly, it’s too easy, and I generally speaking like a challenge.

I saw a bunch of these guys at the health analytics conference I went to a couple of months ago, and let me tell you, they’re weird, and they know it, and they don’t care.

They honestly feel sorry for people who don’t have a Ironman Triathlon (or four) to train for via wireless excel spreadsheets. I mean, how do those people know whether they’ve actually improved? How do they know if they’ve eaten enough carbs? How do they know if they’ve slept??

As far as these Quantified Selfers (QSers) are concerned, it’s only a matter of time before everyone is, like them, making themselves perfect, and they’re the vanguard with nothing to be defensive about.

So anyhoo, those QS guys are convinced that they’re accomplishing something with all of their number collecting and crunching, like maybe they’ll live forever or something (after curing cancer), and they’re just so douchey I feel sorry for them. Blogging about them and trashing them would be like a mean older kid in the playground telling a bunch of little kids that there’s no Santa Claus.

Why do that? Why pop their bubble?

Here’s why: it’s just plain fun, especially now that they’ve ventured into sexy territory with their spreadsheets.

Here are a couple of questions for the Quantified Sexual Selfers (QSSers) in the audience, please get back to me.

- Yes or no: nothing says “hot ‘n’ steamy” like a fitbit readout of historical orgasms.

- Where does the sensor band get attached, and does it come with a vibrating option?

- Are your orgasms more satisfying before or after syncing your daily data with Stephen Wolfram’s?

- What’s your metric of success, and how do you know your girlfriend ain’t gaming the system?

Parenting through benign neglect

In 1985, when I was 12 years old, I went to communist Budapest by myself, for a month. I’d met and befriended two Hungarian families when I was 11 and they were living next door to me for a year in Lexington, Massachusetts, and when they went back to Budapest they invited me to visit.

So it wasn’t like I didn’t have a place to sleep when I got there, but even so, my parents decided that yes, a trip across the world into a country that needed a visa to enter, that didn’t have a hard currency, and that didn’t have consistent phone lines at post offices (never mind at people’s homes, that was out of the question) was a great place for their 12-year-old daughter to visit by herself.

I also almost didn’t make the correct connection in Zurich, and I am seriously wondering what would have happened if I’d missed my flight. How would I have connected with my hosts? Where would I have slept? What would I have done for money?

I did make my flight, though, and I did meet my hosts, and the worst thing that happened to me was that when the cows got sick, I got sick – very sick. And to be fair, I turned 13 when I was there.

I came home appreciating milk pasteurization, and to a lesser extent milk homogenization. I was skinnier and less spoiled, I knew what really good peaches tasted like, and I was completely sick of paprika. Overall it was a good trip, and I’m glad I went.

And if I or my parents had been more cautious, I wouldn’t have gone. Goes to show you, sometimes it’s good not to think too hard about what could go wrong.

Unfortunately, I’m older now, and my 13-year-old just got on a plane to San Francisco by himself to attend a Model UN camp at Stanford. And all I can think about it what might go wrong.

Don’t get me wrong, it didn’t stop me from putting him on the plane. I’m trying to channel my parents’ benign neglect child-raising technique from which I benefitted so tremendously. He’s got a working cell phone, plenty of cash, and my BFF Becky will be within driving distance of him over there.

Hey, it’s not like he’s going to North Korea – which is, by the way, where he requested to be sent – and I’m pretty sure the milk there is pasteurized, as long as you avoid farmer’s markets.

When is smaller better?

It’s another whimsical Sunday morning, a perfect time to re-examine assumptions, and the one I’m working on this morning is when smaller business is actually better, where by “better” I might mean from the perspective of someone inside the business or from the perspective of the public.

I came to this question by way of two articles I’ve read recently.

Women CEO’s

First up we have this article from the Wall Street Journal, written by Sharon Hadary, which is entitled, “Why Are Women-Owned Firms Smaller Than Men-Owned Ones?” and basically wrings its hands about how self-defeating women are when it comes to owning businesses, how they never dream big enough.

Hey, that seems super irrational of women! They’re so self-limiting! Don’t they know that it’s not enough to own your own business, that you should really aspire to owning a business that is really huge?

But you know what? I’ve got a new way of looking at “irrational behavior.” Namely, assume it’s totally rational and figure out what assumptions you’ve got wrong. Let’s stop here and apply this approach. From the article:

Women start businesses to be personally challenged and to integrate work and family, and they want to stay at a size where they personally can oversee all aspects of the business.

Well that was kind of too easy. Turns out that right there, in the article, there’s a rational explanation for a so-called “irrational behavior.” Which is not to say that the writer respects that explanation, of course. Much of the rest of the article focuses how you can convince CEO women that they’re being idiots to think like that.

Of course, that mindset is not the entire story. And to the extent that women’s businesses are small against their will because of sexist behavior and being locked out of credit markets and/or big boy deals, that’s obviously bullshit.

[If I ever become a CEO, I can well imagine wanting to grow it way past the point of understanding or controlling it, because I’m all about being a big swinging dick (BSD), due to my highly robust natural testosterone levels. Because let’s face it, that’s what this is about.]

But if women don’t actually strive to be a BSD in a too-large-to-oversee Fortune 500 company because they’re happy running a smallish profitable business that allows them to see their kids, then why is that a sad story?

CEO pay

Now let’s move to a New York Times article, or really a series of articles, about CEO pay and how it’s big and only getting bigger. As my buddy Suresh explained to me, this is totally inevitable because, as the sizes of companies grow, the size of the CEO’s compensation grows.

Be nerdy with me for a second: if company A and company B merge, you now have a company that’s bigger than A or B, but you only have one CEO whereas you used to have two. So there’s that already, but it doesn’t completely explain it.

Think about the assets of this new company. To the extent that a CEO is supposed to be in charge of 1) not losing, and 2) actually growing these assets, they get some percentage of their “added value”, and that means they get twice as much credit for adding value in a company that’s twice as big.

Now I won’t go deeply into whether CEO’s actually add value – I think, at least in big-ass companies, and in the best-case scenario, CEO mostly they just ooze confidence and allow people to get work done. And I’m not saying this rule of thumb for a certain percentage of assets is reasonable, since it’s a cultural decision. But I do think just complaining about CEO pay being too big is missing the point.

Instead, I think we need to ask whether we think businesses are actually better off being bigger, and for whom. Economists go on and on about how you get economies of scale, but not if things are too big to understand, and not if the real economy of scale is devoted to politics and forming public policy – look at Monsanto for example.

I am the bus queen of Stockholm

Do you know what I really love? Maps. All kinds of maps. If you come to my house, you won’t see standard artwork on the walls, but instead you’ll see: knitting, hanging musical instruments, and maps.

In my kitchen I have a huge map of New York City, which I purchased from Staples for $99 when I moved to the city in 2005, as well as a large subway map, and more recently a bike map. I’ve got New York covered.

And whenever I go to a new city, I enjoy staring at a good map for a few hours, figuring out how to get from place to place by walking or taking a subway or bus. I’m never interested in driving, because I don’t own a car nor do I enjoy riding cabs.

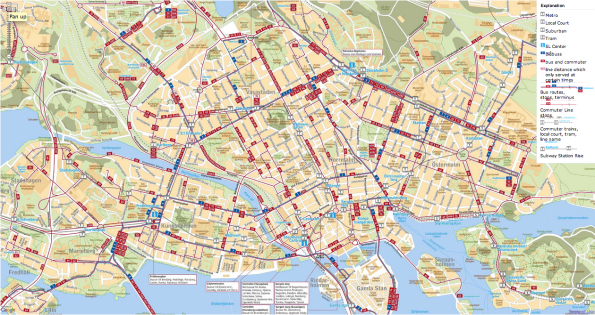

Here’s the map of Stockholm I’ve been staring at for the past few weeks:

It’s a bus map of Stockholm. We smartly bought 7-day passes our first day here, and since kids 12 and younger are free and 13-year-olds are subsidized, this has been a huge win. We’ve been whizzing around the city daily. Buses are really the way to go.

Now, if you’re from certain American cities, you might disagree. You might think buses are slow and painful. But not here! They come every few minutes, more often than subways, and they seem to magically glide from stop to stop (the stops are more infrequent here than in New York, one reason they’re much more efficient). It’s like an unguided tour every time you go anywhere, my favorite kind!

I’ve gotten so excited about (and so proficient at) getting from point A to point B on the bus system, I’ve taken to calling myself the “Bus Queen (of Stockholm),” with practically no self-consciousness whatsoever, even though everyone here speaks perfect English and can hear me brag incessantly to my kids (to their credit, the older ones roll their eyes appropriately).

My four-year-old, who thinks everything I say is true, has asked his older brother to build a Minecraft World called “Bus Queen” in honor of my title, which he has done. As I understand it, the Minecraft villagers internal to Bus Queen World are just about done erecting a Town Hall in my honor. I go!!

One of the great boons of the bus system here in Stockholm is that, unlike Citibikes in New York, you can take a sick and drugged-up 4-year-old on the bus and go places you otherwise wouldn’t be able to walk to. This has been pretty convenient for all of us, believe you me.

But here’s the sad part: there’s a bus strike today in Stockholm and a few other Swedish cities. The bus queen, sadly, may have no throne on which to sit on this, her last day of reign (because we’re coming home tomorrow).

This strike makes me realize something about workers’ conditions in the U.S. which I haven’t thought about since the 2005 New York transit workers’ strike. Namely, Americans don’t have a lot of sympathy for striking workers compared to Europeans. Partly this is because we Americans prize convenience over other people’s conditions (“Can the bus drivers please return to work until after I’ve left Stockholm? The Bus Queen beseeches you!”), and partly this is due, I’m guessing, to the fact that there’s so much income disparity in the U.S. that there’s always some other group of workers worse off than the people striking.

Crash the pick-up party with me?

I’m not sure my friend Jason Windawi will appreciate the credit, but he pointed me to this Meetup yesterday called “MEN THAT DATE HOT WOMEN”, which I have conveniently screen-shotted for y’all:

I’m not sure where to start with deconstructing this pick-up-artist wannabe clan, but let’s just START WITH THE ALL CAPS. Who does that? Update: turns out THE NAVY DOES THAT.

I’m thinking of crashing this Meetup with a posse of sufficiently ridiculous and hilarious friends.

First the good news: I can easily imagine what kind of person I’d love to attract for this action (namely, anyone who thinks this is ludicrous, in a fun way, and wants to join me) but, and here’s the other good news, I’m having trouble figuring out the perfect thing to do once we get there. Let’s think.

First thought: line dance with boas, singing “I will survive.” Maybe not that exactly, but something to intentionally and directly contrast the oppressively normative nature of a bunch of straight guys looking for “hot” women using a formulaic approach involving magic tricks. Bonus points, obviously, for ill-fitting cocktail dresses that emphasize jiggling flesh.

In other words, let’s take a page out of this book, one of my all-time favorite Occupy actions:

Other ideas welcome!

Profit as proxy for value

I enjoyed my discussion with Doug Henwood yesterday at the Left Forum moderated by Suresh Naidu.

At the very end Doug defined capitalism pretty much like this wikipedia article:

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production, with the goal of making a profit.

Doug went on to make the point that, as a society, we might decide to replace our general pursuit of profit by a pursuit of improving our collective quality of life.

It occurred to me that Doug had identified a proxy problem much like I talked about in a recent post called How Proxies Fail. The general history of failed proxies I outlined goes like this:

- We’d like to measure something

- We can’t measure it directly so let’s come up with a proxy

- We’re aware of the problems at first

- We start to use it and it works pretty well

- We slowly forget the problems we had understood, and at the same time

- People start gaming the proxy in various ways and it loses its connection with the original object of interest.

In this example, the thing we’re trying to measure is something along the lines of “human value,” although we’d probably also want to consider value to the rest of mother nature as well. For context, we were discussing the financial system – what the purported function of the financial system is and what monstrous proportions it has taken on due to the brutal pursuit of profits over goals we might consider reasonable and useful to society.

So the proxy for value is profit. And of course we measure profit in money.

Going back to my history of proxies, it’s been a long time ago since the discussion of “whether money is a good proxy for value” was started, and a large part of economic theory, I guess, is devoted to considering the extent to which this proxy fails. I say “I guess” because I’m no economist, but I am aware of the economic concept of externality, which grapples with this discrepancy between money paid or earned, and to whom, versus actual harm or benefit, and to whom.

It could be argued that the concept and industry of regulation has been erected to deal with externalities of our profit proxy: when a chemical company pollutes the water, causing harm to nearby nature and people, regulators step in, sometimes (and sometimes people sue, of course, but most of the time they’re not even aware of the value being extracted from them, or are helpless to confront it adequately).

This is obviously more than an academic or regulatory topic: it pervades our collective lives. When an individual loses sight of the failures of the profit proxy, they value themselves or others in terms of how much money they have or the rate at which they get paid. They infer that if someone is highly paid or rich, they must be valuable. If someone’s poor, they must hold no value. There are a lot of people like this, I’m sure you’ve met them.

And that brings us to the part of the history of a failed proxy, which is that people game the proxy. We’ve seen this happen a lot lately, especially in finance and technology. And if you think about it, it’s no surprise since so much money goes through the financial system, and the financial system is now entirely technologically driven, and the systems are so complex that the regulators can’t keep up with the manufactured externalities. Someone could probably write a book reframing large parts of the financial system as purely devoted to exploiting the difference between value and money.

I don’t think I’ll start coming to different conclusions now that I have this framework to think through, but I do think it will be easier for me to spot instances of the “profit proxy failure” when I come across them. It’s especially timely for me to be thoughtful about this kind of thing, since I’m hoping to create something valuable, rather than merely profitable. I don’t want to avoid profit, obviously, but I don’t want to measure my progress with the wrong stick.

Let’s enjoy the backlash against hackathons

As much as I have loved my DataKind hackathons, where I get to meet a bunch of friendly nerds who are spend their weekend trying to solve problems using technology, I also have my reservations about the whole weekend hackathon culture, especially when:

- It’s a competition, so really you’re not solving problems as much as boasting, and/or

- you’re trying to solve a problem that nobody really cares about but which might make someone money, so you’re essentially working for free for a future VC asshole, and/or

- you kind of solve a problem that matters, but only for people like you (example below).

As Jake Porway mentions in this fine piece, having data and good intentions do not mean you can get serious results over a weekend. From his essay:

Without subject matter experts available to articulate problems in advance, you get results like those from the Reinvent Green Hackathon. Reinvent Green was a city initiative in NYC aimed at having technologists improve sustainability in New York. Winners of this hackathon included an app to help cyclists “bikepool” together and a farmer’s market inventory app. These apps are great on their own, but they don’t solve the city’s sustainability problems. They solve the participants’ problems because as a young affluent hacker, my problem isn’t improving the city’s recycling programs, it’s finding kale on Saturdays.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve made some good friends and created some great collaborations via hackathons (and especially via Jake). But it only gets good when there’s major planning beforehand, a real goal, and serious follow-up. Actually a weekend hackathon is, at best, a platform from which to launch something more serious and sustained.

People who don’t get that are there for something other than that. What is it? Maybe this parody hackathon announcement can tell us.

It’s called National Day of Hacking Your Own Assumptions and Entitlement, and it has a bunch of hilarious and spot-on satirical commentary, including this definition of a hackathon:

Basically, a bunch of pallid millenials cram in a room and do computer junk. Harmless, but very exciting to the people who make money off the results.

This question from a putative participant of an “entrepreneur”-style hackathon:

“Why do we insist on applying a moral or altruistic gloss to our moneymaking ventures?”

And the internal thought process of a participant in a White House-sponsored hackathon:

I realized, especially in the wake of the White House murdering Aaron Swartz, persecuting/torturing Bradley Manning and threatening Jeremy Hammond with decades behind bars for pursuit of open information and government/corporate accountability that really, no-one who calls her or himself a “hacker” has any business partnering with an entity as authoritarian, secretive and tyrannical as the White House– unless of course you’re just a piece-of-shit money-grubbing disingenuous bootlicker who uses the mantle of “hackerdom” to add a thrilling and unjustified outlaw sheen to your dull life of careerist keyboard-poking for the status quo.

Housing bubble or predictable consequence of income inequality?

It’s Sunday, which for me is a day of whimsical smoke-blowing. To mark the day, I think I’ll assume a position about something I know very little about, namely real estate. Feel free to educate me if I’m saying something inaccurate!

There has been a flurry of recent articles warning us that we might be entering a new housing bubble, for example this Bloomberg article. But if you look closely, the examples they describe seem cherry picked:

An open house for a five-bedroom brownstone in Brooklyn, New York, priced at $949,000 drew 300 visitors and brought in 50 offers. Three thousand miles away in Menlo Park, California, a one-story home listed for $2 million got six offers last month, including four from builders planning to tear it down to construct a bigger house. In south Florida, ground zero for the last building boom and bust, 3,300 new condominium units are under way, the most since 2007.

They mention later that Boston hasn’t risen so high as the others hot cities recently, but if you compare Boston to, say, Detroit on this useful Case-Schiller city graph, you’ll note that Boston never really went that far down in the first place.

When I read this kind of article, I can’t help but wonder how much of the signal they are seeing is explained by income inequality, combined with the increasing segregation of rich people in certain cities. New York City and Menlo Park are great examples of places where super rich people live, or want to live, and it’s well known that those buyers have totally recovered from the recession (see for example this article).

And it’s not even just American rich people investing in these cities. Judging from articles like this one in the New York Times, we’re now building luxury sky-scrapers just to attract rich Russians. The fatness of this real estate tail is extraordinary, and it makes me think that when we talk about real estate recoveries we should have different metrics than simply “average sell price”. We need to adjust our metrics to reflect the nature of the bifurcated market.

Now it’s also true that other cities, like Phoenix and Las Vegas are also gaining in the market. Many of the houses in these unsexier areas are being gobbled up by private equity firms investing in rental property. This is a huge part of the market right now in those places, and they buy whole swaths of houses at once. Note we’re not hearing about open houses with 300 buyers there.

Besides considering the scary consequences of a bunch of enormous profit-seeking management companies controlling our nation’s housing, and changing the terms of the rental agreements, I’ll just point out that these guys probably aren’t going to build too large a bubble, since their end-feeder is the renter, the average person who has a very limited income and ability to pay, unlike the Russians. On the other hand, they probably don’t know what they’re doing, so my error bars are large.

I’m not saying we don’t have a bubble, because I’d have to do a bunch of reckoning with actual numbers to understand stuff more. I’m just saying articles like the Bloomberg one don’t convince me of anything besides the fact that very rich people all want to live in the same place.

Star Trek is my religion

I was surprised and somewhat disappointed yesterday when I found this article about Star Trek in Slate, written by Matt Yglesias. He, like me, has recently been binging on Star Trek and has decided to explain “why Star Trek is great” – also my long-term plan. He stole my idea!

My disappointment turned to amazement and glee, however, when I realized that the episode he began his column with was the exact episode I’d just finished watching about 5 minutes before I’d found his article. What are the chances??

It must be fate. Me and Matt are forever linked, even if he doesn’t care (I’m pretty sure he cares though, Trekkies are bonded like that). Plus, I figured, now that he’s written a Star Trek post, I’ll do so as well and we can act like it’s totally normal. Where’s your Star Trek post?

Here’s his opening paragraph:

In the second episode of the seventh season of the fourth Star Trek television series, Icheb, an alien teenage civilian who’s been living aboard a Federation vessel for several months after having been rescued from both the Borg and abusive parents, issues a plaintive cry: “Isn’t that what people on this ship do? They help each other?”

That’s the thing about Star Trek. It’s utopian. There’s no money, partly because they have ways to make food and objects materialize on a whim. There’s no financial system of any kind that I’ve noticed, although there’s plenty of barter, mostly dealing in natural resources. And the crucial resource that characters are constantly seeking, that somehow make the ships fly through space, are called dilithium crystals. They’re rare but they also seem to be lying around on uninhabited planets, at least for now.

But it’s not my religion just because they’ve somehow evolved past too-big-to-fail banks. It’s that they have ethics, and those ethics are collaborative, and moreover are more basic and more important than the power of technology: the moral decisions that they are confronted with and that they make are, in fact, what Star Trek is about.

Each episode can be seen as a story from a nerd bible. Can machines have a soul? Do we care less about those souls than human (or Vulcan) souls? If we come across a civilization that seems to vitally need our wisdom or technology, when do we share it? And what are the consequences for them when we do or don’t?

In Star Trek, technology is not an unalloyed good: it’s morally neutral, and it could do evil or good, depending on the context. Or rather, people could do evil or good with it. This responsibility is not lost in some obfuscated surreality.

My sons and I have a game we play when we watch Star Trek, which we do pretty much any night we can, after all the homework is done and before bed-time. It’s kind of a “spot that issue” riddle, where we decide which progressive message is being sent to us through the lens of an alien civilization’s struggles and interactions with Captain Picard or Janeway.

Gay marriage!

Confronting sexism!

Overcoming our natural tendencies to hoard resources!

Some kids go to church, my kids watch Star Trek with me. I’m planning to do a second round when my 4-year-old turns 10. Maybe Deep Space 9. And yes, I know that “true scifi fans” don’t like Star Trek. My father, brother, and husband are all scifi fans, and none of them like Star Trek. I kind of know why, and it’s why I’m making my kids watch it with me before they get all judgy.

One complaint I’ve considered having about Star Trek is that there’s no road map to get there. After all, how are people convinced to go from a system in which we don’t share resources to one where we do? How do we get to the point where everyone’s fed and clothed and can concentrate on their natural curiosity and desire to explore? Where everyone gets a good education? How can we expect alien races to collaborate with us when we can’t even get along with people who disagree about taxation and the purpose of government?

I’ve gotten over it though, by thinking about it as an aspirational exercise. Not everything has to be pragmatic. And it probably helps to have goals that we can’t quite imagine reaching.

For those of you who are with me, and love everything about the Star Trek franchise, please consider joining me soon for the new Star Trek movie that’s coming out today. Showtimes in NYC are here. See you soon!

In defense of neglectful parenting

As I promised yesterday, I want to respond to this New Yorker article “The Child Trap: the rise of overparenting,” which my friend Chris Wiggins forwarded to me.

The premise of the article is that nowadays we spoil our kids, force them to do a bunch of adult-supervised after-school activities, and generally speaking hover over them, even once they’re adults, and it’s all the fault of technology and (who else?) guilty working mothers. In particular, it makes kids, especially college-age kids, incredibly selfish and emotionally weak.

They interview overparenting skeptics as well, who seem to be focused on the spoiling and indulgent side of overparenting:

As for the steamy devotion shown by later generations of parents, what it has produced are snotty little brats filled with “anger at such abstract enemies as The System,” and intellectual lightweights, certain (because their parents told them so) that their every thought is of great consequence. Epstein says that, when he was teaching, he was often tempted to write on his students’ papers: “D-. Too much love in the home.”

I’m basically in agreement with the article, although I’d go further at some moments and not as far at others.

For example, with spoiling: in my experience, “spoiled kids” is just a phrase people use to describe kids that have acclimated perfectly to their imperfect environments.

So if you train your kids to whine, by saying “no” but then giving in if they whine, then it’s on you, as a parent, to realize you’ve created a perverted environment. Your kid is essentially doing what they’re told. If a 15-year-old kid sitting next to the refrigerator yells for his mom across the living room to get him a glass of juice (I’ve seen this happen) and the mom in question does what she’s been told, then guess what? That kid has learned how to make juice appear.

When you eventually release a spoiled kid in the real world, where there’s nobody to get him juice when he demands it, and when things don’t magically happen because they whine, then all you’ve done is made their entry into that real world harder for them. And in that sense you’ve fucked up.

Because isn’t our main job as parents to make sure they can survive on their own as productive, kind, happy individuals?

On the separate subject of getting your kid to be super gifted through Baby Mozart CD’s and after-school activities (from the article: “You can’t smoke pot or lose your virginity at lacrosse practice.”), it’s an approach to parenting I find toxic, and here’s why.

I think the attention you give to your kids when you force them to practice violin or study for standardized tests is an anxious attention. And just as marriages break down when the majority of interactions between spouses consist of negotiating child pick-ups rather than exchanging ideas and affection, the relationship between parents and kids can similarly suck if you spend more time nagging and worrying about their externally perceived status than enjoying them as people.

And that’s just the day-to-day complaint I have. The larger complaint I have about all this overparenting is that the anxiety we have for our kids’ futures is being projected onto them, and it often translates as a lack of faith in their ability to make it on their own. So rather than preparing them to live independent lives, we’re undermining them from the get-go.

Actually, I’d go one step further. One thing I enjoyed as a latch-key kid of a working mother (who carried no guilt at all) was that, for most things, I was never under scrutiny. What I did with my time after school was up to me, although I wasn’t supposed to watch TV all the time (and I sometimes did anyway, of course – we should all be able to experiment with breaking rules). What I thought about and who I hung out with with were completely up to me – and by the time I was 17 and had my license and a crappy old car, I did some admittedly pretty outrageous things. My parents were so busy they often didn’t even look at my report card in a given year.

In other words, I had a kind of privacy and freedom that I don’t think many kids today can even imagine, although I do my best to provide my kids with a similar environment.

That’s not to say my childhood was perfect, nor were my parents totally neglectful – we had dinner together every night, they gave me a safe environment to roam around in, and I had a bedtime which was enforced. If I hadn’t been doing my homework, I’m pretty sure they would have been on top of me to do it, but I did it on my own. And I was under scrutiny for one thing, namely being mildly overweight, which caused me enough pain then that I understood scrutiny itself to be the source of insecurity.

I can’t help thinking that my childhood would have been a lot worse if my parents had fretted over how I spend my afternoons, even though it’s hard to imagine. It makes me wonder where I’d be now if I hadn’t had those afternoons to spend making unlikely friends, taking on jobs cleaning houses for cash, buying books to read, and generally speaking deciding who I was going to grow up to be.

Do what I want or do what I really want

I’m on my way out to a picnic in Central Park on this glorious Sunday morning, and I plan to write a much more thorough post in response to this New Yorker article on overparenting that my friend Chris Wiggins sent me, but today I just wanted to impart one idea I’ve developed as a mother of three boys.

Namely, kids don’t ever want to do what you want them to do, especially when they’re tired, and it’s awful to feel helpless to get them to something without ridiculous, possibly empty threats, or something worse.

What to do?

My solution is pretty simple, and it works great, at least in my experience. Namely, if I’m getting no response from a reasonable request from my, say, 4-year-old, then I form a separate request which is easier for me and less good for them. And then I offer him a choice between doing what I want or doing what I really want.

Example: it’s bedtime (i.e. 7pm, which we will come back to in further post, which I’m considering calling “In defense of neglectful parenting”) and my kid doesn’t want to stop watching Star Wars Lego movies on Youtube. I’ve asked repeatedly for him to pause the movie so he can brush his teeth, get into his pajamas, and have me read his favorite bedtime story (currently: “Peter and the Shadow Thieves”).

Instead of screaming, picking him up and dragging him to the bathroom, which is increasingly difficult since he’s the size of a 6-year-old, I simply make him an offer:

Either you come brush your teeth right now and I read to you, or you come brush your teeth now and I don’t read to you, and you’ll have to go to bed without a bedtime story. I’m going to count to five and if you don’t come to the bathroom to brush your teeth when I get to “5” then no story.

Here’s the thing. It’s important that he knows I’m serious. I will actually not read to him if he doesn’t hurry up. To be fair, I only had to follow through with this exactly once for him to understand the seriousness of this kind of offer.

What I like about this is the avoidance of drama, empty threats, and physical coercion, or what’s just as annoying, a wasted evening of arguing with an exhausted child about “why there are bedtimes”, which happens so easily without a strategy in place.

What does it mean that our public square is a private place?

I just read this opinion piece written by Jillian York and published by Aljazeera.com. York discusses “How social network policies are changing speech and privacy norms” and she makes the point that there’s a big difference between our legal rights as citizens and the way Facebook has defined its policies, and by extension our “rights” inside Facebook.

So, for example, there’s the question of whether we can show pictures of breastfeeding our children on Facebook. The policy on this has changed – nowadays they say yes, but they used to remove such pictures.

Another example might be more important: whether you can be anonymous. As York points out, Facebook might have an opinion about this, and Zuckerberg seems to – she quotes him as having said “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity” – and yet their vested interest in this question is related to making sure they’ve accurately targeted you for advertisements.

I want to make the case that the “real-life” version of anonymity in Facebook is really just privacy in the simplest sense.

If I am even half-aware of the extent of the surveillance and tracking that goes on when I log into Facebook under my real name, which I don’t even think I am, then I’d tend to use a separate browser, with cleared cookies, and an anonymous Facebook account in order to do absolutely anything without it being tracked. In other words, anonymity is what it takes to do anything privately on Facebook.

Now, you might argue that I can just not go to Facebook at all if I want to do private things, and I’m sure that’s Facebook position as well. But the truth is, Facebook is the world’s public square. Some enormous fraction of the world visits Facebook at least once a week. Exclusion from this would be a big deal.

In any case, it’s weird that decisions like this, that affect our notions of privacy, are being decided by some dude who’s probably thinking more about ad revenue than anything else, under pressure from shareholders.

Not that it’s a new problem. When I was growing up in Lexington, MA, over the cold winters we’d hang out in the Burlington Mall. It was the public square of its time, and yes it was utterly commercial and private, and of course they excluded anyone who they didn’t like the looks of, with security guards. Even so, they didn’t check ID’s at the door.

Mathbabe, the book

Thanks to a certain friendly neighborhood mathbabe reader, I’ve created this mathbabe book, which is essentially all of my posts that I ever wrote (I think. Note sure about that.) bundled together mostly by date and stuck in a huge pdf. It comes to 1,243 pages.

I did it using leanpub.com, which charges $0.99 per person who downloads the pdf. I’m not charging anything over that, because the way I look at it, it’s already free.

Speaking of that, I can see why I’d want a copy of this stuff, since it’s the best way I can think of to have a local version of a bunch of writing I’ve done over the past couple of years, but I don’t actually see why anyone else would. So please don’t think I’m expecting you to go buy this book! Even so, more than one reader has requested this, so here it is.

And one strange thing: I don’t think it required my password on WordPress.com to do it, I just needed the url for the RSS feed. So if you want to avoid paying 99 cents, I’m pretty sure you can go to leanpub or one of its competitors and create another, identical book using that same feed.

And for that matter you can also go build your own book about anything using these tools, which is pretty cool when you think about it. Readers, please tell me if there’s a way to do this that’s open source and free.

Good news Sunday

Sunday mornings tend to provoke me to write the most whimsical posts of the week. I’ve usually gotten enough sleep for the first time in seven days, unless I’m hung over from Saturday late-night karaoke (but I usually like to do that on Fridays), and I can actually remember some of my dreams.

Especially on a glorious sunny Spring morning like today, I can’t abide any bad news or ranting. So today it’s only gonna be good news. Here goes.

1) Chocolate Fondue

Did you know that you can buy chocolate fondue machines for like $9.00? I found this out because at some point I realized my kids hadn’t had chocolate fondue in ages (trust me, it was all about the kids), and I wanted to find a place in New York City where we could go eat fondue, but the only places offering it were like $300 meals for a family of five. So I went on Amazon instead, and paid for the whole shebang for under $30, including the little sticks, and that silly little machine still works. It’s like a happiness machine.

2) Star Trek

There’s a new Star Trek movie, Into Darkness, coming out starting on May 15th. Do not beware the ides of May.

3) TBTF

Sherrod Brown and David Vitter introduced an “end too-big-to-fail” bill this week and they wrote about it in an Op-Ed for the New York Times. It doesn’t mean it’ll be passed, or that it’s perfect, but the momentum is gaining, which is good.

4) Knitting

This is in the category of “good news for me” and you might not care, but after years of worrying that it would be too twine-y, I’ve taken the plunge into knitting with linen and I love it. I’m making this sweater in black linen, and I’ve already finished the back panel:

How to reinvent yourself, nerd version

I wanted to give this advice today just in case it’s useful to someone. It’s basically the way I went about reinventing myself from being a quant in finance to being a data scientist in the tech scene.

In other words, many of the same skills but not all, and many of the same job description elements but not all.

The truth is, I didn’t even know the term “data scientist” when I started my job hunt, so for that reason I think it’s possibly good and useful advice: if you follow it, you may end up getting a great job you don’t even know exists right now.

Also, I used this advice yesterday on my friend who is trying to reinvent himself, and he seemed to find it useful, although time will tell how much – let’s see if he gets a new job soon!

Here goes.

- Write a list of things you like about jobs: learning technical stuff, managing people, whatever floats your boat.

- Next, write a list of things you don’t like: being secretive, no vacation, office politics, whatever. Some people hate working with “dumb people” but some people can’t stand “arrogant people”. It makes a huge difference actually.

- Next, write a list of skills you have: python, basic statistics, math, managing teams, smelling a bad deal, stuff like that. This is probably the most important list, so spend some serious time on it.

- Finally, write a list of skills you don’t have that you wish you did: hadoop, knowing when to stop talking, stuff like that.

Once you have your lists, start going through LinkedIn by cross-searching for your preferred city and a keyword from one of your lists (probably the “skills you have” list).

Every time you find a job that you think you’d like to have, take note of what skills it lists that you don’t have, the name of the company, and your guess on a scale of 1-10 of how much you’d like the job into a spreadsheet or at least a file. This last part is where you use the “stuff I like” and “stuff I don’t like” lists.

And when you’ve done this for a long time, like you made it your job for a few hours a day for at least a few weeks, then do some wordcounts on this file, preferably using a command line script to add to the nerdiness, to see which skills you’d need to get which jobs you’d really like.

Note LinkedIn is not an oracle: it doesn’t have every job in the world (although it might have most jobs you could ever get), and the descriptions aren’t always accurate.

For example, I think companies often need managers of software engineers, but they never advertise for managers of software engineers. They advertise for software engineers, and then let them manage if they have the ability to, and sometimes even if they don’t. But even in that case I think it makes sense: engineers don’t want to be managed by someone they think isn’t technical, and the best way to get someone who is definitely technical is just to get another engineer.

In other words, sometimes the “job requirements” data on LInkedIn dirty, but it’s still useful. And thank god for LinkedIn.

Next, make sure your LinkedIn profile is up-to-date and accurate, and that your ex-coworkers have written letters for you and endorsed you for your skills.

Finally, buy a book or two to learn the new skills you’ve decided to acquire based on your research. I remember bringing a book on Bayesian statistics to my interview for a data scientist. I wasn’t all the way through the book, and my boss didn’t even know enough to interview me on that subject, but it didn’t hurt him to see that I was independently learning stuff because I thought it would be useful, and it didn’t hurt to be on top of that stuff when I started my new job.

What I like about this is that it looks for jobs based on what you want rather than what you already know you can do. It’s in some sense the dual method to what people usually do.

On being an alpha female, part 2

Almost a year ago now I wrote this post on being an alpha female. I had only recently understood that I was an alpha female, when I wrote it, and it was still kind of new and weird.

For whatever reason it’s been coming up a lot recently and I wanted to update that post with my observations.

Who’s burning which bridges?

Last week I wrote an outraged post about seeing Ina Drew at Barnard.

Mind you, I had anticipated I’d find the event objectionable. I had even polled my Occupy friends for prepared questions for her. But when I got there I realized pretty quickly that I wouldn’t be able to ask her anything. I was just too disgusted with the tone and conceit of the event to participate in it reasonably. Instead I live tweeted the event and seethed.

I lost sleep that night fuming about Drew-as-role-model, and I was grateful to be able to get some of my frustration out on my blog.

One of the first comments I received was this one, which said:

Boy Cathy, you sure do know how to burn bridges.

This was, for me, kind of a perfect alpha female moment. My immediate reaction was to think to myself,

They burned bridges with me, you mean.

Since that sounded too arrogant, at the moment anyway, I said something else just slightly less obnoxious. Three points to make here:

- Anyone who doesn’t agree with me about whether Ina Drew should be celebrated can go suck it.

- That post got linked to from Reuters, FT.com, and Naked Capitalism. Which doesn’t happen when you’re worrying about burning bridges.

- When I’m in a certain kind of mood, I’m simply not concerned with other people’s judgments. I think that’s just part of being an alpha female, and I’m grateful for it.

Why grateful? Because lots of shitty things happen when people go around worrying about “burning their bridges” instead of speaking up about bullshit or evil-doing. Or, as Felix Salmon tweeted recently:

Best point made on this #waronwhistleblowers panel: failure to leak has cost many more lives than leaking ever has.

— felix salmon (@felixsalmon) April 17, 2013

Taking notes from an uber alpha female

A few months ago I got an email inviting me to speak in a Python in Finance conference. The email was somewhat weird and kind of just came out and said they need women speakers. I was put in a position of being asked to be a token woman, which is a mindset I don’t enjoy.

I thought about it though, and although I use python, and I used to work in finance, I don’t work in finance any more, and I don’t really think about python too much, I just use it. So I said to the organizer, no thanks, I don’t have anything to say at that conference.

Fast forward to the week before the conference, when I got wind of the agenda. It turned out my friend Claudia Perlich, Chief Data Scientist at m6d and one of the contributors to my upcoming book with Rachel Schutt, was the keynote speaker. I decided to go to the conference essentially because I wanted to see her.

Well, it turned out Claudia had gotten a similar email, and she had accepted the invitation, even though she doesn’t work in finance and doesn’t even use python (she uses perl).

She gave a great talk about modeling blind spots, which everyone enjoyed. It was quite possibly the best talk of the day, in fact. Plus, she wasn’t at all token – having her on the schedule was what made me come to the conference, and I probably wasn’t the only one. And judging by the crowd at the Meetup I gave last night, I would have drawn my own crowd too, if I had been speaking.

I made an alpha female note to myself that day to accept any invitation to a conference that I’d enjoy, even if my expertise isn’t completely within the realm of the conference. I’m learning from Claudia, a master alpha female. Or is it mistress?

Alpha females and self-image

Chris Wiggins recently sent me this essay entitled “A Rant on Women” by Clay Shirky, a writer and professor who studies the social and economic effects of Internet technologies. Here’s the first paragraph:

So I get email from a good former student, applying for a job and asking for a recommendation. “Sure”, I say, “Tell me what you think I should say.” I then get a draft letter back in which the student has described their work and fitness for the job in terms so superlative it would make an Assistant Brand Manager blush.

Guess what? That student is male.

Shirky goes on to vent about how women don’t oversell themselves enough compared to men and how it’s a problem. An excerpt:

There is no upper limit to the risks men are willing to take in order to succeed, and if there is an upper limit for women, they will succeed less. They will also end up in jail less, but I don’t think we get the rewards without the risks.

This made me think about my experience. First, as a Barnard professor, I certainly saw this effect. I’d have men and women come talk to me about letters of recommendations, and not only would I prepare myself for the difference in posture, I’d try to address it directly, by encouraging women to learn how to brag about their accomplishments. I might have tried to convince men a couple of times to stop bragging quite so much, but quickly found that to be a huge waste of time.

But beyond corroborating that this is typical behavior, the essay made me remember myself as a college student.

When I met my thesis advisor, Barry Mazur, who was on sabbatical at UC Berkeley, I remember telling him a math problem I had worked on and solved. He expressed something about liking the problem and being impressed that I’d explained it so well, and I said back,

“Yeah, I’m awesome”

I remember this because of his reaction. At the time, the word “awesome” was widely used among teenagers, but evidently he hadn’t gotten the teenager memo, and he was taken aback by the way I used it. At least that’s what he said. But now that I think about it, maybe he was taken aback that I’d said it at all.

Alpha females and body image

My friend and guest poster Becky recently sent me this video:

It’s about how women have a biased view on their looks, or at least describe their looks to other people in a consistently negatively biased way.

There’s a great critique of this video here (hat tip Avani Patel), wherein fashion and style guru Jennifer Choy complains that the underlying message to the above video is that, in any case, beauty is about all women have going for them, so they should not underestimate their beauty. Plus that all the women in the video were skinny, young, and white.

Great points, but my take was somewhat different.

My immediate reaction to the video was to say, these women need to spend less time thinking about being fat or ugly, and more time thinking about what they think is sexy and attractive. Why is it always about finding flaws in ourselves? Why don’t we spend more time thinking about what turns us on or what we think is beautiful?

I’ll be honest: I think if I had been interviewed in that setting, I would have said something like, “Gorgeous and sexy as hell” and gone on to list my best features. I am not sure I’d have even been able to describe what I look like in any detail, with any accuracy. Most likely I would have just started bragging about my sexy grey streaks. Even more likely: I wouldn’t have had the time to sit down for this interview at all.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve dabbled in being insecure in my looks: puberty sucked, as did all three post-natal periods until the baby was weaned*, in addition to any time I was ever on the pill**. I’ve concluded that my inherent arrogance is directly related to my hormones, which in turn makes it undeniably tied to my alpha femaleness.

Suffice it to say, when my hormones are not messed up I have “body eumorphia,” where I ignore or downplay any non-perfect parts of my body. It’s a nice feeling.

It kind of makes me want to develop an alpha female hormone treatment. Business model?

UPDATE: Please watch this new spoof video, it’s perfect (except it should be alpha females and men, not just men):

* It gets better when you know it’s going to go away. By the third kid I was like, “gonna cry every day at 3:00pm for the next six weeks. Must schedule that into my calendar.”

** Note to doctors: you need to tell women that the real reason birth control pills work so well is that you lose interest in sex when you’re on them!

War of the machines, college edition

A couple of people have sent me this recent essay (hat tip Leon Kautsky) written by Elijah Mayfield on the education technology blog e-Literate, described on their About page as “a hobby weblog about educational technology and related topics that is maintained by Michael Feldstein and written by Michael and some of his trusted colleagues in the field of educational technology.”

Mayfield’s essay is entitled “Six Ways the edX Announcement Gets Automated Essay Grading Wrong”. He’s referring to the recent announcement, which was written about in the New York Times last week, about how professors will soon be replaced by computers in grading essays. He claims they got it all wrong and there’s nothing to worry about.

I wrote about this idea too, in this post, and he hasn’t addressed my complaints at all.

First, Mayfield’s points:

- Journalists sensationalize things.

- The machine is identifying things in the essays that are associated with good writing vs. bad writing, much like it might learn to distinguish pictures of ducks from pictures of houses.

- It’s actually not that hard to find the duck and has nothing to do with “creativity” (look for webbed feet).

- If the machine isn’t sure it can spit back the essay to the professor to read (if the professor is still employed).

- The machine doesn’t necessarily reward big vocabulary words, except when it does.

- You’d need thousands of training examples (essays on a given subject) to make this actually work.

- What’s so really wonderful is that a student can get all his or her many drafts graded instantaneously, which no professor would be willing to do.

Here’s where I’ll start, with this excerpt from near the end:

“Can machine learning grade essays?” is a bad question. We know, statistically, that the algorithms we’ve trained work just as well as teachers for churning out a score on a 5-point scale. We know that occasionally it’ll make mistakes; however, more often than not, what the algorithms learn to do are reproduce the already questionable behavior of humans. If we’re relying on machine learning solely to automate the process of grading, to make it faster and cheaper and enable access, then sure. We can do that.

OK, so we know that the machine can grade essays written for human consumption pretty accurately. But it hasn’t had to deal with essays written for machine consumption yet. There’s major room for gaming here, and only a matter of time before there’s a competing algorithm to build a great essay. I even know how to train that algorithm. Email me privately and we can make a deal on profit-sharing.

And considering that students will be able to get their drafts graded as many times as they want, as Mayfield advertised, this will only be easier. If I build an essay that I think should game the machine, by putting in lots of (relevant) long vocabulary words and erudite phrases, then I can always double check by having the system give me a grade. If it doesn’t work, I’ll try again.

And the essays built this way won’t get caught via the fraud detection software that finds plagiarism, because any good essay-builder will only steal smallish phrases.

One final point. The fact that the machine-learning grading algorithm only works when it’s been trained on thousands of essays points to yet another depressing trend: large-scale classes with the same exact assignments every semester so last year’s algorithm can be used, in the name of efficiency.

But that means last year’s essay-building algorithm can be used as well. Pretty soon it will just be a war of the machines.