Archive

An AMS panel to examine public math models?

On Saturday I gave a talk at the AGNES conference to a room full of algebraic geometers. After introducing myself and putting some context around my talk, I focused on a few models:

- VaR,

- VAM,

- Credit scoring,

- E-scores (online version of credit scores), and

- The h-score model (I threw this in for the math people and because it’s an egregious example of a gameable model).

I wanted to formalize the important and salient properties of a model, and I came up with this list:

- Name – note the name often gives off a whiff of political manipulation by itself

- Underlying model – regression? decision tree?

- Underlying assumptions – normal distribution of market returns?

- Input/output – dirty data?

- Purported/political goal – how is it actually used vs. how its advocates claim they’ll use it?

- Evaluation method – every model should come with one. Not every model does. A red flag.

- Gaming potential – how does being modeled cause people to act differently?

- Reach – how universal and impactful is the model and its gaming?

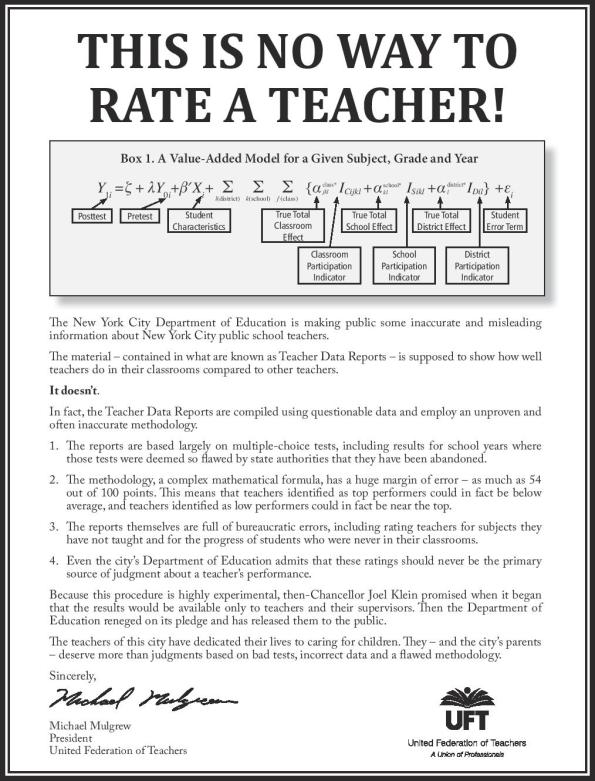

In the case of VAM, it doesn’t have an evaluation method. There’s been no way for teachers to know if the model that they get scored on every year is doing a good job, even as it’s become more and more important in tenure decisions (the Chicago strike was largely related to this issue, as I posted here).

Here was my plea to the mathematical audience: this is being done in the name of mathematics. The authority that math is given by our culture, which is enormous and possibly not deserved, is being manipulated by people with vested interests.

So when the objects of modeling, the people and the teachers who get these scores, ask how those scores were derived, they’re often told “it’s math and you wouldn’t understand it.”

That’s outrageous, and mathematicians shouldn’t stand for it. We have to get more involved, as a community, with how mathematics is wielded on the population.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t want mathematicians as a group to get co-opted by these special interest groups either and become shills for the industry. We don’t want to become economists, paid by this campaign or that to write papers in favor of their political goals.

To this end, someone in the audience suggested the AMS might want to publish a book of ethics for mathematicians akin to the ethical guidelines that are published for the society of pyschologists and lawyers. His idea is that it would be case-study based, which seems pretty standard. I want to give this some more thought.

We want to make ourselves available to understand high impact, public facing models to ensure they are sound mathematically, have reasonable and transparent evaluation methods, and are very high quality in terms of proven accuracy and understandability if they are used on people in high stakes situations like tenure.

One suggestion someone in the audience came up with is to have a mathematician “mechanical turk” service where people could send questions to a group of faceless mathematicians. Although I think it’s an intriguing idea, I’m not sure it would work here. The point is to investigate so-called math models that people would rather no mathematician laid their eyes on, whereas mechanical turks only answer questions someone else comes up with.

In other words, there’s a reason nobody has asked the opinion of the mathematical community on VAM. They are using the authority of mathematics without permission.

Instead, I think the math community should form something like a panel, maybe housed inside the American Mathematical Society (AMS), that trolls for models with the following characteristics:

- high impact – people care about these scores for whatever reason

- large reach – city-wide or national

- claiming to be mathematical – so the opinion of the mathematical community matters, or should,

After finding such a model, the panel should publish a thoughtful, third-party analysis of its underlying mathematical soundness. Even just one per year would have a meaningful effect if the models were chosen well.

As I said to someone in the audience (which was amazingly receptive and open to my message), it really wouldn’t take very long for a mathematician to understand these models well enough to have an opinion on them, especially if you compare it to how long it would take a policy maker to understand the math. Maybe a week, with the guidance of someone who is an expert in modeling.

So in other words, being a member of such a “public math models” panel could be seen as a community service job akin to being an editor for a journal: real work but not something that takes over your life.

Now’s the time to do this, considering the explosion of models on everything in sight, and I believe mathematicians are the right people to take it on, considering they know how to admit they’re wrong.

Tell me what you think.

On my way to AGNES

I’m putting the finishing touches on my third talk of the week, which is called “How math is used outside academia” and is intended for a math audience at the AGNES conference.

I’m taking Amtrak up to Providence to deliver the talk at Brown this afternoon. After the talk there’s a break, another talk, and then we all go to the conference dinner and I get to hang with my math nerd peeps. I’m talking about you, Ben Bakker.

Since I’m going straight from a data conference to a math conference, I’ll just make a few sociological observations about the differences I expect to see.

- No name tags at AGNES. Everyone knows each other already from undergrad, grad school, or summer programs. Or all three. It’s a small world.

- Probably nobody standing in line to get anyone’s autograph at AGNES. To be fair, that likely only happens at Strata because along with the autograph you get a free O’Reilly book, and the autographer is the author. Still, I think we should figure out a way to add this to math conferences somehow, because it’s fun to feel like you’re among celebrities.

- No theme music at AGNES when I start my talk, unlike my keynote discussion with Julie Steele on Thursday at Strata. Which is too bad, because I was gonna request “Eye of the Tiger”.

The investigative mathematical journalist

I’ve been out of academic math a few years now, but I still really enjoy talking to mathematicians. They are generally nice and nerdy and utterly earnest about their field and the questions in their field and why they’re interesting.

In fact, I enjoy these conversations more now than when I was an academic mathematician myself. Partly this is because, as a professional, I was embarrassed to ask people stupid questions, because I thought I should already know the answers. I wouldn’t have asked someone to explain motives and the Hodge Conjecture in simple language because honestly, I’m pretty sure I’d gone to about 4 lectures as a graduate student explaining all of this and if I could just remember the answer I would feel smarter.

But nowadays, having left and nearly forgotten that kind of exquisite anxiety that comes out of trying to appear superhuman, I have no problem at all asking someone to clarify something. And if they give me an answer that refers to yet more words I don’t know, I’ll ask them to either rephrase or explain those words.

In other words, I’m becoming something of an investigative mathematical journalist. And I really enjoy it. I think I could do this for a living, or at least as a large project.

What I have in mind is the following: I go around the country (I’ll start here in New York) and interview people about their field. I ask them to explain the “big questions” and what awesomeness would come from actually having answers. Why is their field interesting? How does it connect to other fields? What is the end goal? How would achieving it inform other fields?

Then I’d write them up like columns. So one column might be “Hodge Theory” and it would explain the main problem, the partial results, and the connections to other theories and fields, or another column might be “motives” and it would explain the underlying reason for inventing yet another technology and how it makes things easier to think about.

Obviously I could write a whole book on a given subject, but I wouldn’t. My audience would be, primarily, other mathematicians, but I’d write it to be readable by people who have degrees in other quantitative fields like physics or statistics.

Even more obviously, every time I chose a field and a representative to interview and every time I chose to stop there, I’d be making in some sense a political choice, which would inevitably piss someone off, because I realize people are very sensitive to this. This is presuming anybody every read my surveys in the first place, which is a big if.

Even so, I think it would be a contribution to mathematics. I actually think a pretty serious problem with academic math is that people from disparate fields really have no idea what each other is doing. I’m generalizing, of course, and colloquiums do tend to address this, when they are well done and available. But for the most part, let’s face it, people are essentially only rewarded for writing stuff that is incredibly “insider” for their field. that only a few other experts can understand. Survey of topics, when they’re written, are generally not considered “research” but more like a public service.

And by the way, this is really different from the history of mathematics, in that I have never really cared about who did what, and I still don’t (although I’m not against name a few people in my columns). The real goal here is to end up with a more or less accurate map of the active research areas in mathematics and how they are related. So an enormous network, with various directed edges of different types. In fact, writing this down makes me want to build my map as I go, an annotated visualization to pair with the columns.

Also, it obviously doesn’t have to be me doing all this: I’m happy to make it an open-source project with a few guidelines and version control. But I do want to kick it off because I think it’s a neat idea.

A few questions about my mathematical journalism plan.

- Who’s going to pay me to do this?

- Where should I publish it?

If the answers are “nobody” and “on mathbabe.org” then I’m afraid it won’t happen, at least by me. Any ideas?

One more thing. This idea could just as well be done for another field altogether, like physics or biology. Are there models of people doing something like that in those fields that you know about? Or is there someone actually already doing this in math?

Evaluating professor evaluations

I recently read this New York Times “Room for Debate” on professor evaluations. There were some reasonably good points made, with people talking about the trend that students generally give better grades to attractive professors and easy grading professors, and that they were generally more interested in the short-term than in the long-term in this sense.

For these reasons, it was stipulated, it would be better and more informative to have anonymous evaluations, or have students come back after some time to give evaluations, or interesting ideas like that.

Then there was a crazy crazy man named Jeff Sandefer, co-founder and master teacher at the Acton School of Business in Austin, Texas. He likes to call his students “customers” and here’s how he deals with evaluations:

Acton, the business school that I co-founded, is designed and is led exclusively by successful chief executives. We focus intently on customer feedback. Every week our students rank each course and professor, and the results are made public for all to see. We separate the emotional venting from constructive criticism in the evaluations, and make frequent changes in the program in real time.

We also tie teacher bonuses to the student evaluations and each professor signs an individual learning covenant with each student. We have eliminated grade inflation by using a forced curve for student grades, and students receive their grades before evaluating professors. Not only do we not offer tenure, but our lowest rated teachers are not invited to return.

First of all, I’m not crazy about the idea of weekly rankings and public shaming going on here. And how do you separate emotional venting from constructive criticism anyway? Isn’t the customer always right? Overall the experience of the teachers doesn’t sound good – if I have a choice as a teacher, I teach elsewhere, unless the pay and the students are stellar.

On the other hand, I think it’s interesting that they have a curve for student grades. This does prevent the extra good evaluations coming straight from grade inflation (I’ve seen it, it does happen).

Here’s one think I didn’t see discussed, which is students themselves and how much they want to be in the class. When I taught first semester calculus at Barnard twice in consecutive semesters, my experience was vastly different in the two classes.

The first time I taught, in the Fall, my students were mostly straight out of high school, bright eyed and bushy tailed, and were happy to be there, and I still keep in touch with some of them. It was a great class, and we all loved each other by the end of it. I got crazy good reviews.

By contrast, the second time I taught the class, which was the next semester, my students were annoyed, bored, and whiny. I had too many students in the class, partly because my reviews were so good. So the class was different on that score, but I don’t think that mattered so much to my teaching.

My theory, which was backed up by all the experienced Profs in the math department, was that I had the students who were avoiding calculus for some reason. And when I thought about it, they weren’t straight out of high school, they were all over the map. They generally were there only because they needed some kind of calculus to fulfill a requirement for their major.

Unsurprisingly, I got mediocre reviews, with some really pretty nasty ones. The nastiest ones, I noticed, all had some giveaway that they had a bad attitude- something like, “Cathy never explains anything clearly, and I hate calculus.” My conclusion is that I get great evaluations from students who want to learn calculus and nasty evaluations from students who resent me asking them to really learn calculus.

What should we do about prof evaluations?

The problem with using evaluations to measure professor effectiveness is that you might be a prof that only has ever taught calculus in the Spring, and then you’d be wrongfully punished. That’s where we are now, and people know it, so instead of using them they just mostly ignore them. Of course, the problem with not ever using these evaluations is that they might actually contain good information that you could use to get better at teaching.

We have a lot of data collected on teacher evaluations, so I figure we should be analyzing it to see if there really is a useful signal or not. And we should use domain expertise from experienced professors to see if there are any other effects besides the “Fall/Spring attitude towards math” effect to keep in mind.

It’s obviously idiosyncratic depending on field and even which class it is, i.e. Calc II versus Calc III. If there even is a signal after you extract the various effects and the “attractiveness” effect, I expect it to be very noisy and so I’d hate to see someone’s entire career depend on evaluations, unless there was something really outrageous going on.

In any case it would be fun to do that analysis.

How is math used outside academia?

Help me out, beloved readers. Brainstorm with me.

I’m giving two talks this semester on how math is used outside academia, for math audiences. One is going to be at the AGNES conference and another will be a math colloquium at Stonybrook.

I want to give actual examples, with fully defined models, where I can explain the data, the purported goal, the underlying assumptions, the actual outputs, the political context, and the reach of each model.

The cool thing about these talks is I don’t need to dumb down the math at all, obviously, so I can be quite detailed in certain respects, but I don’t want to assume my audience knows the context at all, especially the politics of the situation.

So far I have examples from finance, internet advertising, and educational testing. Please tell me if you have some more great examples, I want this talk to be awesome.

The ultimate goal of this project is probably an up-to-date essay, modeled after this one, which you should read. Published in the Notices of the AMS in January 2003, author Mary Poovey explains how mathematical models are used and abused in finance and accounting, how Enron booked future profits as current earnings and how they manipulated the energy market. From the essay:

Thus far the role that mathematics has played in these financial instruments has been as much inspirational as practical: people tend to believe that numbers embody objectivity even when they do not see (or understand) the calculations by which particular numbers are generated. In my final example, mathematical principles are still invisible to the vast majority of investors, but mathematical equations become the prime movers of value. The belief that makes it possible for mathematics to generate value is not simply that numbers are objective but that the market actually obeys mathematical rules. The instruments that embody this belief are futures options or, in their most arcane form, derivatives.

Slightly further on she explains:

In 1973 two economists produced a set of equations, the Black-Scholes equations, that provided the first strictly quantitative instrument for calculating the prices of options in which the determining variable is the volatility of the underlying asset. These equations enabled analysts to standardize the pricing of derivatives in exclusively quantitative terms. From this point it was no longer necessary for traders to evaluate individual stocks by predicting the probable rates of profit, estimating public demand for a particular commodity, or subjectively getting a feel for the market. Instead, a futures trader could engage in trades driven purely by mathematical equations and selected by a software program.

She ends with a bunch of great questions. Mind you, this was in 2003, before the credit crisis:

But what if markets are too complex for mathematical models? What if irrational and completely unprecedented events do occur, and when they do—as we know they do—what if they affect markets in ways that no mathematical model can predict? What if the regularity that all mathematical models assume effaces social and cultural variables that are not subject to mathematical analysis? Or what if the mathematical models traders use to price futures actually influence the future in ways the models cannot predict and the analysts cannot govern? Perhaps these are the only questions that can challenge the financial axis of power, which otherwise threatens to remake everything, including value, over in the image of its own abstractions. Perhaps these are the kinds of questions that mathematicians and humanists, working together, should ask and try to answer.

NSA mathematicians

When I was a promising young mathematician in college, I met someone from the NSA who tried to recruit me to work for the spooks in the summer. Actually, “met someone” is misleading- he located me after I had won a prize.

I didn’t know what to think, so I accepted his invitation to visit the institute, which was in La Jolla, in Southern California (I went to UC Berkeley so it wasn’t a big trip).

When I got to the building, since I didn’t have clearance, everybody had to stop working the whole time I was there. It wasn’t enough to clean their whiteboards, one of them explained, they had to wash them down with that whiteboard spray stuff, because if you look at a just-erased whiteboard in a certain way you can decipher what had been written on it.

I met a bunch of people, maybe 6 or 7. They all told me how nice it was to work there, how the weather was beautiful, how the math problems were interesting. It was strangely consistent, but who knows, perhaps also true.

One thing I’d already learned before coming is that there are many layers of work that happen before the math people in La Jolla are given problems to do. First, the actual problem is chosen, then the “math” of the problem is extracted from the problem, and third it’s cleansed so that nobody can tell what the original application is.

Knowing this (and I was never contradicted when I explained that process), I asked each of them the same question: how do you feel about the fact that you don’t know what problem you’re actually solving?

Out of the 6 or 7 people I met, everyone but one person responded along the lines, “I believe everything the United States Government does is good.” The last guy said, “yeah, that bothers me. I am honestly seriously considering leaving.”

Needless to say, I didn’t take the job. I wasn’t yet a major league skeptic, but I was skeptical enough to realize I could not survive in such an environment, with colleagues that oblivious. They also mentioned that I’d have to stop dating my Czech boyfriend and that I’d need to submit information about all my roommates for the past 10 years, which was uber creepy.

Nowadays I hear estimates that 600 mathematicians work at the NSA, and of course many more stream through during the summer when school’s not in session, both at La Jolla and Princeton. Somehow they don’t mind not knowing how their work actually gets used. I’m not sure how that’s possible but it clearly is.

This mindset came back to me, and not in a good way, when I read this opinion piece and watched this video in the New York Times a couple of days ago.

William Binney, a mathematician, was working on Soviet Union spying software that got converted to domestic spying after 9/11. In other words, they used his foreign spying algorithm on a new data source, namely American citizen’s raw data. He objected to that, so strongly that he’s come out against it publicly.

The big surprise is how come they let him know what they were actually up to. My guess is he was high enough up the chain that they thought he’d be okay with it – he’d been there 32 years, and I guess he was considered an insider.

In any case, watch the video: this is a courageous man. The FBI came into his house with guns drawn to intimidate him against his whistleblowing activities and yet he hasn’t been cowed. Indeed, after getting dressed (he was coming out of the shower when they exploded into his house), he explained to them the crimes of George Bush and Dick Cheney on his back porch.

As he explains, “the purpose is to monitor what people are doing”. He explains how people’s social media data and other kinds of data are linked over domains and over time to build profiles of Americans over time: “you have 10 years of their life that you can lay out in a timeline, that involves anybody in the country”.

Describing the dangers of this program, Binney was extremely articulate:

- “The danger here is that we could fall into a totalitarian state like East Germany”

- “We can’t have secret interpretations of laws and run them in secret and not tell anybody. We can’t make up kill lists and not tell anybody what the criterion is for being on the kill list”

- “Just because we call ourselves a democracy doesn’t mean we will stay that way.”

There you have it. The good news is that that guy is no longer helping the NSA do their thing.

But the bad news is, plenty of mathematicians still are. And if you want to find a community more trusting and loyal than mathematicians, I think you’d have to go to a kindergarten somewhere. Not to mention the fact that, as I described above, the problems are intentionally cleaned to look innocuous.

Another example, possibly the most important one of all, of mathematics being manipulated to potentially evil ends. We will have trouble proving actual evil consequences, of course, since there’s no transparency. The only update we will get is via the next whistleblower who can handle guns pointed at him as he leaves his shower.

What is a proof?

I recently described (here) a proof to be a convincing argument of why you think something is true. I’ll stick to that definition in spite of a few commenters who want there to be axioms or postulates, because I really don’t think that’s what happens in real life (which is a good thing! It would be an incredibly boring life!). Since I’m a utilitarian, I only care about and only want to discuss what actually happens.

The above definition immediately begs the question, convincing to whom? Can a proof to someone be a non-proof to someone else? Absolutely, proofs are entirely context-driven. If I’m trying to prove something to you and you remain unconvinced, then it is no proof, even if I’ve used the same argument before successfully.

This brings me to my first main point, which is that it the responsibility of the person proving something to convince his or her audience that it’s true. Likewise, it is the responsibility of the audience to remain skeptical (but attentive) and be open to being convinced or to finding a flaw in the argument.

Things get trickier when it’s not a live interaction, but when things are written down, like in published articles. On the one hand, written proofs give the audience more time to understand the reasoning and to come up with problems, but on the other hand there’s no opportunity to say “I just don’t get what you’re talking about,” which is the feeling one typically has at least 85% of the time.

In an ideal world, those who write proofs understand the goal to be that the reader should be able to understand the argument, and thus make the arguments coherent and understandable to their “typical reader.” Who is this typical reader? Someone who is probably relatively fluent in the basic objects of the field, say, but hasn’t recently thought about this problem.

Now that I’ve described the ideal situation, I’ll rant for a bit about how people game this system. There are two things that creep into the system that give rise to its gaming, and those two things are status and credit. People like to be high status (and like to signal high status even more), and of course people like to take credit.

First, status. It turns out that people often really want to explain their reasoning no to the typical audience, but to the expert audience. So they don’t give sufficient context, and they are lazy reasoners, because the experts can be expected to understand how to fill in the details.

It’s not only insecure young mathematicians that are guilty of this – there are plenty of experts who themselves fall prey to this habit (thus the signaling). I think it’s driven by a combination of feeling kind of smug and smart when people who are trying to follow your conversation leave because they’re exhausted and confused (and possibly ashamed), and the echo chamber that remains after people who don’t get it (or who admit to not getting it) leave. Whatever the reason, there are plenty of experts who get less and less understandable over time, in person and in print.

The other side of this status play is those experts get away with it. The papers written by these people are often accepted in spite of the fact that they are nearly unreadable to all but the 5 people in their field for whom they have been written, since after all, these guys are experts.

But does this approach constitute a proof? I claim it doesn’t, not if I have to be one of 5 people to read and understand it. The writer has choked, bigtime, on his or her responsibility to convince the reader.

Second, the credit thing. People want to get credit for proving things, because that’s how they get high status. But they don’t always want to prove everything they claim, because it’s hard work. So sometimes you see people proving something and then claiming an even more general thing is true, and giving a “sketch of a proof” for that more general thing (this is one example where “sketches” come up, but actually there are plenty of them).

Let’s examine that concept for a moment, the “sketch of a proof.” Usually this implies that the basic outline is there, but many details of how to rely on so-and-so’s theorem or what’s-his-name’s method are left out. It’s a proof lying in the shadows, and we’ve only seen it highlighted every few feet or so to wend our way through it.

Is a sketch a proof? No, it’s not. Best case scenario, it would take a typical reader a few minutes, maybe up to two hours, say, to turn that sketch into a proof.

But what if the typical reader can’t do it in two hours?

The problem with the concept of a sketch of a proof is that it’s too difficult to refute. If I am a reader and I say, “this is a false sketch” then I could just be opening myself up to people who tell me I didn’t spend my two hours wisely, or that I’m not good enough to complain about it. They may even expect me to prove that that method cannot be used to prove that result.

But that’s bullshit! As far as I’m concerned, if you claim to have sketched a proof, and if I’ve tried to prove it using your notes and I’ve failed, then that’s your fault, not mine. It’s your responsibility to prove it to me, and you haven’t.

Conclusion: let’s all remember when you claim a result, you are claiming credit, and it’s your responsibility to convince the audience it’s true – not just 5 experts. And second, if you aren’t willing to actually prove something, don’t claim it as a result. Instead, say something like, “this may generalize using so-and-so’s theorem or what’s-his-name’s method….”. Consider it a gift to the next person who reads your paper and wants to prove something new.

Does mathematics have a place in higher education?

A recent New York Times Opinion piece (hat tip Wei Ho), Is Algebra Necessary?, argues for the abolishment of algebra as a requirement for college. It was written by Andrew Hacker, an emeritus professor of political science at Queens College, City University of New York. His concluding argument:

I’ve observed a host of high school and college classes, from Michigan to Mississippi, and have been impressed by conscientious teaching and dutiful students. I’ll grant that with an outpouring of resources, we could reclaim many dropouts and help them get through quadratic equations. But that would misuse teaching talent and student effort. It would be far better to reduce, not expand, the mathematics we ask young people to imbibe. (That said, I do not advocate vocational tracks for students considered, almost always unfairly, as less studious.)

Yes, young people should learn to read and write and do long division, whether they want to or not. But there is no reason to force them to grasp vectorial angles and discontinuous functions. Think of math as a huge boulder we make everyone pull, without assessing what all this pain achieves. So why require it, without alternatives or exceptions? Thus far I haven’t found a compelling answer.

For an interesting contrast, there’s a recent Bloomberg View Piece, How Recession Will Change University Financing, by Gary Shilling (not to be confused with Robert Shiller). From Shilling’s piece:

Most thought that a bachelor’s degree was the ticket to a well-paid job, and that the heavy student loans were worth it and manageable. And many thought that majors such as social science, education, criminal justice or humanities would still get them jobs. They didn’t realize that the jobs that could be obtained with such credentials were the nice-to-have but nonessential positions of the boom years that would disappear when times got tough and businesses slashed costs.

Some of those recent graduates probably didn’t want to do, or were intellectually incapable of doing, the hard work required to major in science and engineering. After all, afternoon labs cut into athletic pursuits and social time. Yet that’s where the jobs are now. Many U.S.-based companies are moving their research-and-development operations offshore because of the lack of scientists and engineers in this country, either native or foreign-born.

For 34- to 49-year-olds, student debt has leaped 40 percent in the past three years, more than for any other age group. Many of those debtors were unemployed and succumbed to for-profit school ads that promised high-paying jobs for graduates. But those jobs seldom materialized, while the student debt remained.

Moreover, many college graduates are ill-prepared for almost any job. A study by the Pew Charitable Trusts examined the abilities of U.S. college graduates in three areas: analyzing news stories, understanding documents and possessing the math proficiency to handle tasks such as balancing a checkbook or tipping in a restaurant.

The first article is written by a professor, so it might not be surprising that, as he sees more and more students coming through, he feels their pain and wants their experience to not be excruciating. The easiest way to do that is to remove the stumbling block requirement of math. He also seems to think of higher education as something everyone is entitled to, which I infer based on how he dismisses vocational training.

The second article is written by a financial analyst, an economist, so we might not be surprised that he strictly sees college as a purely commoditized investment in future income, and wants it to be a good one. The easiest way to do that is to have way fewer students go through college to begin with, since having dumb or bad students get into debt but not learn anything and then not get a job afterwards doesn’t actually make sense.

And where the first author acts like math is only needed for a tiny minority of college students, the second author basically dismisses non-math oriented subjects as frivolous and leading to a life of joblessness and debt. These are vastly different viewpoints. I’m thinking of inviting them both to dinner to discuss.

By the way, I think that last line, where Hacker wonders what the pain of math-as-huge-boulder achieves, is more or less answered by Shilling. The goal of having math requirements is to have students be mathematically literate, which is to say know how to do everyday things like balancing checkbooks and reading credit card interest rate agreements. The fact that we aren’t achieving this goal is important, but the goal is pretty clear. In other words, I think my dinner party would be fruitful as well as entertaining.

If there’s one thing these two agree on, it’s that students are having an awful lot of trouble doing basic math. This makes me wonder a few things.

First, why is algebra such a stumbling block? Is it that the students are really that bad, or is the approach to teaching it bad? I suspect what’s really going on is that the students taking it have mostly not been adequately taught the pre-requisites. That means we need more remedial college math.

I honestly feel like this is the perfect place for online learning. Instead of charging students enormous fees while they get taught high-school courses they should already know, and instead of removing basic literacy requirements altogether, ask them to complete some free online math courses at home or in their public library, to get them ready for college. The great thing about computers is that they can figure out the level of the user, and they never get impatient.

Next, should algebra be replaced by a Reckoning 101 course? Where, instead of manipulating formulas, we teach students to figure out tips and analyze news stories and understand basic statistical statements? I’m sure this has been tried, and I’m sure it’s easy to do badly or to water down entirely. Please tell me what you know. Specifically, are students better at snarky polling questions if they’ve taken these classes than if they’ve taken algebra?

Finally, I’d say this (and I’m stealing this from my friend Kiri, a principal of a high school for girls in math and science): nobody ever brags about not knowing how to read, but people brag all the time about not knowing how to do math. There’s nothing to be proud of in that, and it’s happening to a large degree because of our culture, not intelligence.

So no, let’s not remove mathematical literacy as a requirement for college graduates, but let’s think about what we can do to make the path reasonable and relevant while staying rigorous. And yes, there are probably too many students going to college because it’s now a cultural assumption rather than a thought-out decision, and this lands young people in debt up to their eyeballs and jobless, which sucks (here’s something that may help: forcing for-profit institutions to be honest in advertising future jobs promises and high interest debt).

Something just occurred to me. Namely, it’s especially ironic that the most mathematically illiterate and vulnerable students are being asked to sign loan contracts that they, almost by construction, don’t understand. How do we address this? Food for thought and for another post.

The fake problem of fake geek girls, and how to be a sexy man nerd

My friend Rachel Schutt recently sent me this Forbes article by Tara Tiger Brown on the so-called problem of too many fake geek girls stealing the thunder and limelight from us true geek girls.

The working definition of geek seems to be someone who is obsessively interested in something (I would argue that you don’t get to be a geek if your obsession is art, for example, I’d like to define it to be an obsession with something technical). She also claims that “true geeks” don’t do something for airtime. From the article:

Girls who genuinely like their hobby or interest and document what they are doing to help others, not garner attention, are true geeks. The ones who think about how to get attention and then work on a project in order to maximize their klout, are exhibitionists.

I kind of like this but I kind of don’t too. I like this because, like you, I have run into many many people (men and women) who loudly claim technical knowledge that they don’t seem to actually have, which is annoying and exhibitionistic. And yes, it’s annoying to see people like that doing things like giving things like Ted talks on “big data” when you seriously doubt they know how to program a linear regression. But again, men and women.

At the same time, there’s no reason someone can’t be both a true geek and an exhibitionist, and it seems kind of funny for a Forbes magazine writer to be claiming the authentic rights to the former but not the latter.

If there’s one thing I’d like to avoid, it’s peer pressure that, as a girl geek, I have to have a certain personality. I like the fact that girl geeks are sometimes shy and sometimes outspoken, sometimes humble and sometimes arrogant, sometimes demure and sometimes slutty. It makes it way more interesting during technical chats.

What’s the asymmetry between men and women here? According to Tara Tiger Brown, women think they’ll get attention from men by acting like a geek but my experience is that men don’t think they’ll get attention from women by acting like a geek.

I think this is a mistake that man geeks are making. For me, and for essentially all my female friends, being really fucking good at some thing is extremely sexy. Man geeks are, therefore, very sexy, if they are in fact really fucking good at something and not just posing. Maybe they just need to realize that and own it a bit more.

Next time, instead of apologizing for doing something nerdy, I suggest you (a man geek I’m imagining talking to right now) figure out how to describe what skill you mastered and talk about it as an accomplishment.

No: I’m kind of tired today, sorry. I stayed up all night playing with my computer. Should we reschedule?

Yes: Last night I implemented dynamic logistic regression and managed to get it to converge on 30 terabytes of streaming data in under 3 hours. And it’s all open source, I just checked in into github. That was awesome! But now I need to sleep. Wanna take a nap with me?

Ideas for two thesis problems in data science

Natural Language Processing on math overflow

You know about math overflow? It’s a site where grad students in math (or anyone) go and pose questions, and other people can answer them. There are lots of uninteresting, unanswered questions (like questions that are too easy and the person should be able to look up) and there are some really popular ones and some really dumb ones. Sometimes there are interesting ones.

Here’s a thesis idea, come up with a metric for “interestingness” and try to forecast the interestingness of a question from its language. Might as well also try to forecast its popularity while you’re at it. That way, if you make a good model, some of the more interesting questions will get higher in the queue and people will have a better time at the site.

Genealogy graphs in different fields

You know about the mathematics genealogy project? It shows everyone with a Ph.D. in math and considers them to be “descended” from their advisor in a family-tree like structure. For example, I’m here, and if I got up through my ancestors in 7 steps I get to Jacobi. Actually there are lots of ways to go up since a bunch of people have more than one advisor – I’m also 7 steps away from Poisson, 8 from Lagrange and Laplace, and 9 from Euler. This is probably not because I’m so cool but because there just weren’t many mathematicians back then- probably most people descended from Euler. And because we have this cool data set we can see if that’s true!

Here’s what I think someone should do, besides visualizing this graph in an awesome way (which by itself would be really cool, has anyone done that?). They should draw the graph for other fields as well and try to see if there are graph properties that characterize mathematics as distinct from other disciplines like Physics or Law or History.

The meritocracy myth

Jack and Larry

Recently a Wall Street Journal article described what I’ll call a “Larry Summers” moment for women in business. Namely, Jack Welch, the former CEO of General Electric, spoke to a bunch of women about how if they work hard enough they’ll be appreciated and get ahead. From the article:

He had this advice for women who want to get ahead: Grab tough assignments to prove yourself, get line experience, and embrace serious performance reviews and the coaching inherent in them.

“Without a rigorous appraisal system, without you knowing where you stand…and how you can improve, none of these ‘help’ programs that were up there are going to be worth much to you,” he said. Mr. Welch said later that the appraisal “is the best way to attack bias” because the facts go into the document, which both parties have to sign.

Just as in the case of Larry Summer’s now-famous 2005 speech about women in science and math, a bunch of women left Welch’s talk in frustration.

There is no such thing as a meritocracy

Having been in academic mathematics and a quant in a hedge fund, I’d guess I’ve experienced what comes closest in many people’s minds as the closest to a meritocratic system. But my experience is that it’s anything but, even in these highly quantitative settings.

Instead, as it probably is everywhere, the job environment is a huge social game where it matters, a lot, what kind of priorities you demonstrate and what kind of other signals you give off or respond to. We don’t expect people to play golf and smoke cigars in academia but caring about teaching, or worse, getting a teaching award, can be the kiss of death.

I’m not saying that your personal efforts don’t matter at all, because they do, and you do need to produce stuff, and at a certain rate, but even “personal efforts” are first of all received in the context of a social order (i.e. the perceived importance of your efforts at the very least is a social invention), and second of all they’re are not really personal – one frames the questions one answers with the help of the community, so it’s important you have a good connection and social acceptance in that community (i.e. access to the experts).

Business in more generality is even less meritocratic- there’s a specific requirement that you must “play well with others,” which is absent from academics (mercifully). This means that instead of being an implicit social game, it’s been made very explicit. This is where people promote their work, take credit for others’ work, learn to say what people want to hear, etc. The performance review is a circle-jerk event for such empty-headed manipulations, which makes it particularly ironic that Welch suggested women take the criticism in an appraisal so seriously.

In my experience, it is unbelievably useful for these social games to have an alpha personality, which just kind of means you assume you’re in charge even when it’s not explicitly a situation where someone’s in charge. People respond to such personalities on a chemical level and there’s really nothing a so-called meritocratic system can do about that.

In other words, I’m not holding my breath for a truly meritocratic system. It’s just not what humans evolved for. Let’s acknowledge that and work on how to make the system responsive to good ideas anyway (whatever the system is).

Successful people want to believe that there is such a thing as meritocracy

This begs the question, why do people like Jack Welch and Larry Summers hold on so tight to the myth of meritocracy? My theory is that it serves a two-fold goal: as advertisement for new people and as a validation of the winners in the system.

People want to feel like they are entering a level playing field then the best thing you can do is advertise it as a meritocracy, because it’s human nature to think that you’re better than average. So everyone wants to enter such a field, assuming they will rise to the top.

At the same time, the `winners’ of the social game want desperately to think they did amazing stuff in order to be so successful. They hold on to the myth of meritocracy as a religious belief, and it is pure dogma by the time they reach upper management. This plays into another part of human nature where we discount luck and the infrastructure that led to our success and take it as a sign of our personal choices. Lots of people in finance in general suffer from this diseased mindset but actually anyone who is high enough up in their respective `meritocratic system’ does too.

That’s my simple explanation for why these guys can go in front of a bunch of women and be so unbelievably tone-deaf. They are true believers, because their entire egos are built on this belief, and it doesn’t matter how much counter-evidence is presented to them, even in the form of humans in the room with them.

One last thought. If I saw people leaving a room in disgust when I was giving a talk, I imagine I’d be slightly aghast- I might even pause and ask them what’s wrong. But I guess that’s because I’m not alpha enough.

Declaration of Linear Independence: the nerdiest thing you’ve ever seen

My friend Michael Thaddeus recently informed me of the existence of the Declaration of Linear Independence, written by mathematician David Grabiner. I will describe the document as a “re-imagining” of the original Declaration of Independence from the point of view of a set of vectors in some vector space which feel, for whatever reason, that their independence has been under attack (I’m considering inviting them to join Occupy).

I’m not really sure I can ethically ask you to read the entire document, due to the intense nerdiness of it which may cause the weaker among you to lose consciousness, but let me give you the flavor. Here’s the most famous sentence translated into vector-angst:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all nonzero vectors are created equal; that they are endowed by their definer with certain unalienable rights; that among these are the laws of logic and the pursuit of valid proofs; that to secure these rights, logical arguments are created, deriving their just powers from axioms; that whenever any argument becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the vectors to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new argument, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to reach the correct conclusion.

Whereas the original document listed grievances against King George III, this new one complains about Professor Eigen, who is a made-up guy personifying everything which is overbearing and repressive about eigenvectors, eigenspaces and eigenvalues. Here’s my favorite complaint:

He has restricted our freedom of movement by requiring us all to live in the same hyperplane, even though we cannot all fit in one.

Finally, the ending is really quite good for those of us who on the one hand remember our linear algebra and on the other hand sympathize with these vectors being denied their (linear) independence rights:

Should we have a ratings agency for scientific theories?

Recently in my friend Peter Woit’s blog, he discussed the idea of establishing a ratings agency for physics. From his blog:

In this week’s Nature, Abraham Loeb, the chair of the Harvard astronomy department, has a column proposing the creation of a web-site that would act as a sort of “ratings agency”, implementing some mathematical model that would measure the health of various subfields of physics. This would provide young scientists with more objective information about what subfields are doing well and worth getting involved with, as opposed to those which are lingering on despite a lack of progress.

Abraham Loeb was proposing to describe the field of String Theory as a perfect example of a bubble. And it’s absolutely true that String Theory has provided finance with tons of brilliant young orphans who either got disillusioned with the field or simply couldn’t get a job after writing a Ph.D. or after a post-doc. It provides an extreme example of a mismatch between supply and demand.

Would a ratings agency for scientific theories help? I don’t think so.

The very basic reason, as Peter points out, is that it’s hard to evaluate scientific theories while they are unfolding. There are two underlying causes: first, people in a field are too invested to admit things aren’t working out, and second, by the nature of scientific research, things could not work out for some time but then eventually still work out. It’s not clear when to give up on a theory!

Ignoring those problems, imagine a “mathematical model” which tries to gauge the success of a field. What would the elemental quantities be that would signify success? Would it count the number of proven theorems? Crappy theorems are easy to prove. Would it count the the number of successful experiments? We could always take a successful experiment and change it ever so slightly to get another success. I can’t think of a quantitative way to measure a field that isn’t open for enormous manipulation (which would only happen if people actually cared about the ratings agency’s rating).

Of course the same might be said about financial ratings. It begs the question, why are ratings agencies useful at all?

In finance we have lots of people buying very similar products with very similar contracts. Sometimes these are even sold on exchanges and carry with them the exact same risk profiles. In such a situation it makes sense to assign someone to look into the underlying risks and report back to the community on how risky a product is.

I would claim that the situation is very different in science or math. People enter a field for all sorts of reasons, with all sorts of goals and situations. String Theory is an extreme case where it could be argued that it got such spin that a whole generation of physics students got sucked into the field by sheer momentum. Perhaps it would have been nice to have a trusted institution whose job it was to calm people down and point out the reality, but I’m not sure it would have helped that much with all the excitement, especially if there had been a model which counted theorems and such. People would just have said the model had never seen something this exciting.

Then there’s the issue of trusting the modeler. Right now ratings agencies have a terrible reputation because they are paid by the people they rate products for, and have been known to sell good ratings. I’m hoping we can do better in the future, but it’s hard (but not impossible!) to imagine gathering enough experts in finance to do it well and to have the product be trusted by the community.

What is the analogy for scientific theories? The problem with rating science is that, because of the depth of most fields, only the experts in the field themselves understand it well enough to even talk about it. So that problem of getting an informed and impartial view on the worthiness of a theory is super super hard, assuming it’s possible.

Finally, I’m not sure what the ratings agency would be in charge of warning people about. Even the financial ratings agencies don’t agree- some of them measure default risk and others measure expected loss through default, which can be two really different things (for example if you think the U.S. will technically default but will end up paying their debts).

In science, I guess you could try to measure the risk that “the theory won’t end up being useful” but it’s not even clear how you’d decide that even after the fact. Maybe you could forecast the number of jobs in the field for graduating Ph.D. students, and that would be helpful to grad students but would also not be the best metric of success for the field.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t have people talk about fields and whether fields are failing, because that’s hugely important. But I don’t think there’s a quantitative model there to be created that would help the conversation. Let’s start an open forum, or a wiki, with the goal of talking about the health of various fields of scientific endeavor and have a bunch of good questions about the field and people can each add their two cents.

How to teach someone how to prove something

In a couple of my posts (most recently here), I’ve talked about the need for a course early on in undergraduate math classes on proof techniques.

The goals of the class are two-fold: first, teach the students basic skills, and second demystify the concept of proof. The students should come away from the class thinking, no it’s not magic, and I’ve learned how to do this stuff, and there are a few basic techniques which seem to come in handy.

Today I want to go further into what a curriculum for such a course might look like.

And I will, in a moment, but first I want to explain something. It’s actually a really important and dangerous question, how to teach such a course, because it could go wildly wrong, and sometimes does. From my commenter Jordan:

… “Numbers, Equations, and Proofs,” which I started at Princeton in 2002 and which is still going as well. Though here’s an interview with a dude who was an ace math competition dude and found the course so hard as to drive him out of the math major! So maybe it’s no longer as “for everyone” as I designed it to be….

This struck me, how perverted Jordan’s class became. For that matter, Math 55 at Harvard could have started out as a good idea as well, but by the time I got to Harvard as a grad student it was the reason so few math majors ever stuck at Harvard and why there were especially few women.

I remember Noam Elkies taught it while I was there and was famous for asking questions in class and getting students to compete to answer them quickly. It makes sense that he’d run a class like this, because he’s so fast and clever, and he’s naturally wondering, am I the fastest and clevererest of them all? But rather than a place where proof is demystified and people feel safe asking dumb questions, he’d created the polar opposite, a live quiz show of clever competition. Ew!

In order to combat this downfall and decay, I think the class needs to have a clearly stated mission as well as built-in curriculum requirements that works against ostentatious displays of cleverness, which indeed only serve to further the “I got it but you don’t” stereotype of math skills (but which mathematicians themselves are incentivized to further since that magical aura comes in handy).

For example, when I taught it, I let the students hand in homework again and again until they got a score they liked. Of course, this depending on me having an awesome grader (and a relatively small class), which luckily I had.

Also, I asked each student to give a presentation to the class on some proof they particularly enjoyed, and I sat through a preview of their presentation and gave them extensive advice on board work and eye contact, which took a lot of work but really helped them prepare and also boosted their egos while at the same time increased their sympathy with each other and with me.

But of course the most important thing was that I clearly stated at the beginning of each class in the first two weeks that proving things in math was a skill like any other that you get good at through practice. And when I left Barnard Dusa McDuff took over the class and still teaches it, so I know it’s in good hands.

If I hadn’t had Dusa, I’d probably have written a manifesto to be given to each person who would teach the class after me. Of course anyone could have just thrown that away but it’s an idea.

As for content, I taught them really basic proof techniques, so induction, proof by contradiction, the pigeon-hole principle, and some epsilon-delta practice. We covered some basic logic, graph theory, group theory, ordinals, and basic analysis. We constructed the reals two ways and the complex numbers once and talked for a long time about whether “i” is real and what that even means. We used A Transition to Higher Mathematics, which I recommend with a few reservations (please tell me if you’ve found a better text for something like this!).

Everything was done super explicitly and carefully, no rushing. I said things three times in three different ways. I wasn’t expecting people to be fast or clever, because I know intelligence works in different ways and that this stuff was completely new to most of the students. And at least one student in the class, who had been an artist, is now a grad student in math at Berkeley.

Looking over my post I realize I spent way more time talking about the tone of the class than the content, but that’s totally appropriate, since I think of this class as an introduction to the culture of mathematics (or rather the culture I wish we had) just as much as mathematics itself.

After all, there really is no time limit on good ideas, and you do get to do it over if you make a mistake, and going over things slowly gives you more time to ask good questions and find mistakes.

Today is Sonia Kovalevsky Day

Sometimes I imagine what my life would have been life if I’d been born way earlier, like in 1850. Knowing how difficult it was back then to be a female mathematician, and not wanting to assume some special property like I was born royalty or otherwise incredibly rich, I usually settle on something like a farmer’s life, with 7 kids and a butter churn, Little-House-on-the-Prairie style. To satisfy my nerdy urges I imagine myself knitting difficult patterns and formally organizing the community’s crop rotations.

I really don’t have much insight into what it must have been like back then, but even a short thought experiment like this helps me appreciate the story of Sofia Kovalevskaya, who was indeed born in Moscow in 1850 and unbelievably contributed majorly to mathematics, even though (hat tip Robert Lipshitz):

- it was illegal to go to university in Russia at the time so she had a faux marriage in order to get permission from her husband to go abroad to study,

- got a Ph.D. in Berlin studying under some famous men (Helmholtz, Kirchhoff and Bunsen in Heidelberg, Weirstrass), becoming the first woman in Europe to ever get hold the degree,

- after which time nobody in Germany would let her work so she did various jobs including installing streetlamps,

- and finally managed to get some kind of weird position in Sweden (here‘s a more complete bio).

Did I mention that she eventually had a kid with her husband and then died at the age of 41 from the flu?

I’d really love to go back in time for a day, find Sweden, and buy that amazing woman a drink (and I’d try to arrange to slip some antibiotics into said drink).

Today we are celebrating Sonia at Barnard College (here’s the schedule), where for the nth time (where n is at least 5) we’re having a Sonia Kovalevsky Day with a crowd of young women mathematicians, 9th graders from the Urban Assembly Institute of Math & Science for Young Women, will come and enjoy math talks from Barnard and Columbia professors and then engage in a team competition (with their teachers, which is my favorite part) to see who will win incredibly small prizes but for which they will all scream their heads off for 2 hours. It’s fun!

I started this tradition when I was a Barnard math professor back in 2006 with my friend Kiri Soares who runs the UA Institute, and that fact that it’s still going makes me very happy. Every time I go I try to teach the students how to solve the Rubiks cube using a few tricks which stem from group theory. It’s fun to do and they all get to take home their cubes, along with other math toys and goodies. Mmmm… math toys.

Open Models (part 2)

In my first post about open models, I argued that something needs to be done but I didn’t really say what.

This morning I want to outline how I see an open model platform working, although I won’t be able to resist mentioning a few more reasons we urgently need this kind of thing to happen.

The idea is for the platform to have easy interfaces both for modelers and for users. I’ll tackle these one at a time.

Modeler

Say I’m a modeler. I just wrote a paper on something that used a model, and I want to open source my model so that people can see how it works. I go to this open source platform and I click on “new model”. It asks for source code, as well as which version of which open source language (and exactly which packages) it’s written in. I feed it the code.

It then asks for the data and I either upload the data or I give it a url which tells the platform the location of the data. I also need to explain to the platform exactly how to transform the data, if at all, to prepare it for feeding to the model. This may require code as well.

Next, I specify the extent to which the data needs to stay anonymous (hopefully not at all, but sometimes in the case of medical data or something, I need to place security around the data). These anonymity limits will translate into the kinds of visualizations and results that can be requested by users but not the overall model’s aggregated results.

Finally, I specify which parameters in my model were obvious “choices” (like tuning parameters, or prior strengths, or thresholds I chose for cleaning data). This is helpful but not necessary, since other people will be able to come along later and add things. Specifically, they might try out new things like how many signals to use, which ones to use, and how to normalize various signals.

That’s it, I’m done, and just to be sure I “play” the model and make sure that the results jive with my published paper. There’s a suite of visualization tools and metrics of success built into the model platform for me to choose from which emphasize the good news for my model. I’ve created an instance of my model which is available for anyone to take a look at. This alone would be major progress, and the technology already exists for some languages.

User

Now say I’m a user. First of all, I want to be able to retrain the model and confirm the results, or see a record that this has already been done.

Next, I want to be able to see how the model predicts a given set of input data (that I supply). Specifically, if I’m a teacher and this is the open-sourced value added teacher model, I’d like to see how my score would have varied if I’d had 3 fewer students or they had had free school lunches or if I’d been teaching in a different district. If there were a bunch of different models, I could see what scores my data would have produced in different cities or different years in my city. This is a good start for a robustness test for such models.

If I’m also a modeler, I’d like to be able to play with the model itself. For example, I’d like to tweak the choices that have been made by the original modeler and retrain the model, seeing how different the results are. I’d like to be able to provide new data, or a new url for data, along with instructions for using the data, to see how this model would fare on new training data. Or I’d like to think of this new data as updating the model.

This way I get to confirm the results of the model, but also see how robust the model is under various conditions. If the overall result holds only when you exclude certain outliers and have a specific prior strength, that’s not good news.

I can also change the model more fundamentally. I can make a copy of the model, and add another predictor from the data or from new data, and retrain the model and see how this new model performs. I can change the way the data is normalized. I can visualize the results in an entirely different way. Or whatever.

Depending on the anonymity constraints of the original data, there are things I may not be able to ask as a user. However, most aggregated results should be allowed. Specifically, the final model with its coefficients.

Records

As a user, when I play with a model, there is an anonymous record kept of what I’ve done, which I can choose to put my name on. On the one hand this is useful for users because if I’m a teacher, I can fiddle with my data and see how my score changes under various conditions, and if it changes radically, I have a way of referencing this when I write my op-ed in the New York Times. If I’m a scientist trying to make a specific point about some published result, there’s a way for me to reference my work.

On the other hand this is useful for the original modelers, because if someone comes along and improves my model, then I have a way of seeing how they did it. This is a way to crowdsource modeling.

Note that this is possible even if the data itself is anonymous, because everyone in sight could just be playing with the model itself and only have metadata information.

More on why we need this

First, I really think we need a better credit rating system, and so do some guys in Europe. From the New York Times article (emphasis mine):

Last November, the European Commission proposed laws to regulate the ratings agencies, outlining measures to increase transparency, to reduce the bloc’s dependence on ratings and to tackle conflicts of interest in the sector.

But it’s not just finance that needs this. The entirety of science publishing is in need of more transparent models. From the nature article’s abstract:

Scientific communication relies on evidence that cannot be entirely included in publications, but the rise of computational science has added a new layer of inaccessibility. Although it is now accepted that data should be made available on request, the current regulations regarding the availability of software are inconsistent. We argue that, with some exceptions, anything less than the release of source programs is intolerable for results that depend on computation. The vagaries of hardware, software and natural language will always ensure that exact reproducibility remains uncertain, but withholding code increases the chances that efforts to reproduce results will fail.

Finally, the field of education is going through a revolution, and it’s not all good. Teachers are being humiliated and shamed by weak models, which very few people actually understand. Here’s what the teacher’s union has just put out to prove this point:

Math-Startup Collaborative at Columbia tomorrow

The Columbia Chapter of SIAM (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics) invites YOU to:

Spring 2012 Math-Startup Collaborative Wednesday, February 29 | 6:00 – 8:00 PM | Davis Auditorium, Schapiro Center

Meet Columbia alumni from NYC startups, including Bitly, Foursquare, and Codecademy, and learn about the role of math and engineering in their companies. Students interested in startup careers and internships, or those simply curious to see how math is applied in the wild, are especially welcome. The event, which consists of a series of presentations from our startup members, will be followed by a reception (with free food!). This is sure to be the largest applied math event of the semester!

Startup presenters include:

- Bitly –> http://blog.bitly.com/

- Foursquare –> https://foursquare.com/about/

- Codecademy –> http://blog.codecademy.com/

- BuzzFeed –> http://www.buzzfeed.com/about

- Sailthru –> http://blog.sailthru.com/

Space is limited! Contact Ilana Lefkovitz (itl2103@columbia.edu) for more information.

Please RSVP at bit.ly/Math–Startup-RSVP-2012

Co-sponsored by the Application Development Initiative (ADI). Reception sponsored by AOL Ventures.

Why I love nerds

What is it that grad students do all day? Well if you’re Zachary Abel in the M.I.T. math department, then the answer may be that you fiddle with paperclips and make awesome nerdy and beautiful sculpture (I found his page through the God Plays Dice blog). Here’s my favorite sculpture from his site:

Be sure to read the explanations he gives of the things he’s made, they are very cool and sometimes comes with animation.

Mathematics has an Occupy moment

The Occupy Wall Street movement means a lot of things to a lot of people, but one of the things it pretty much universally represents is the concept of agency.

Instead of sitting passively by and allowing a dysfunctional system to detract from a culture, the participants in Occupy want to object, to reform the system, and if that doesn’t work, to build a new system. And the crucial point is that they feel that they have the right (if not obligation) to do so. Moreover, they wish to construct a new paradigm built on democratic understanding of the shared goals of the system itself, rather than letting whomever is in power decide how things work and who benefits.

I feel like there’s an analogy to be drawn between this process and what’s happening now in the fight between mathematicians and Elsevier, and for that matter the publishing world (as has been pointed out, Springer has the same issues as Elsevier, even though people like Springer a lot more).

It may seem like the fight against Elsevier is only a small part of the mathematics system, in that it’s really only one publisher of many, and some people (like the journal of Topology) have already gone ahead and started new journals that don’t share the more toxic properties that the Elsevier journals have. I don’t think that narrow view is justified.

In fact, part of tearing down Elsevier has to include a broader understanding of how antiquated the entire academic publishing world is, which immediately begs the question of what we need to build to replace it. This is not unlike the Occupy movement’s goal to replace the current financial system with another which would primarily serve the needs of the citizens and only secondarily the desires of bankers. A tall order to be sure, but luckily for mathematicians their system is less complicated, and moreover the community is much more empowered.

Why am I waxing so poetic over this struggle? Because, at the heart of the question of “what is the new system” is the even more fundamental question, “what do we, as a community, wish to treasure and what do we wish to discard?”. After all, we already have arXiv, or in other words a repository of everything, and the question then becomes, how do we sort out the good stuff from the crap?

I want to stop right there and examine that question, because it’s already quite loaded. Let’s face it, people don’t always agree on what it means for something to be good versus crap, and if there was ever a time to examine that question it’s now.

Here’s a thought experiment I’d like you to do with me. Since leaving academic mathematics, I’ve realized the enormous value of being able to explain mathematical concepts to broader audiences, and I’ve been left with the distinct impression that such a skill is underappreciated inside academic mathematics. In the past 8 months, since writing this blog, I’ve become sort of a hybrid mathematician and journalist, and it’s kind of cool, if unfocused. But what if I decided to really focus on the journalism side of mathematics inside mathematics, would that be appreciated?

So the thought experiment is this. Imagine if, every 6 months, I moved to a new field of mathematics and acted as a mathematical journalist, interviewing the people in math about their work, their field, where it’s going, what the important questions are, etc., and at the end of the 6 month gig I wrote an expository article that explained that field to the rest of the mathematicians. I’d do that every 6 months for 20 years, and I’ve covered 40 fields. Assuming I’m as good at explaining things as I say I am, I’ve really opened up these fields to a larger audience (albeit still math folks), which may allow for better communication between fields, or may avoid redundant work between fields, or may simply enrich the understanding of what’s going on. From my perspective, the work I’d be doing would really be mathematics, and would further the overall creation of mathematics.

However, think about those expository articles I’d be writing. They wouldn’t be original, nor would they be particularly hard- if anything the goal would be for people to understand them. Would they ever get published in a top journal (as of now)? I don’t think so. And please don’t suggest that papers like this, written by famous people in their fields, have been well-received. This is true but I claim more a result of the reputation of the writers than because of the content.

Let’s go back to the question of how we sort papers on arXiv. For some people, this question is really confusing and even scary. They fear that any system besides the one now in place would devalue contributions that are more technical, harder, and less accessible over results that are easy, flashy, and amenable to pop culture sound bytes. I exaggerate for effect, but this is the gist of worries I’ve been hearing. For these people, which I will call “the traditionalists”, the most they want to do is to circumvent the publishers’ fees but otherwise keep intact the referee system, whereby there are gatekeepers who choose experts to anonymously review papers. The publishers are the organizers of this system, and by inviting people to be editors for their journals essentially anoint the gatekeepers.

I actually think those traditionalists should be afraid, but not exactly for the reasons that they think. Instead of worrying that their hard, technical papers won’t be appreciated, they should worry that other, totally different kinds of skills will be appreciated. Of course in the end it’s the same result, namely that the top universities may not forever be populated exclusively by people who prove wonderfully difficult, original and ground-breaking results. They could also include people who are the great story-tellers of mathematics and are appreciated for their gifts of understanding and disseminating mathematics, as well as their broad understanding of the field.

In other words, a democratic system actually looks different from a oligarchy, and that’s not necessarily bad, although the oligarchs may think it is.

I’m going to make a prediction, namely that there will be two different systems in place in 15 years. Neither will involve traditional publishers, but one of them will keep that refereeing system intact whereas the other will be more of a crowd-sourced referee system. Maybe it will be something like this idea of Yann LeCun, for example. Maybe it will be better for women. That would be cool.

By the way, I want to be clear that I’m not suggesting all papers are written equally. There really are people who make huge contributions to their fields through proving hard, creative theorems. I just think there are also people who contribute to mathematics in other ways, that also require hard work and excellent skills. And there aren’t just two skills, of course; I just simplified matters for this discussion.

The discussion of the future of academic publishing is raging, as I posted about here. And that discussion is really important in itself, and the fact that so many people are participating in it, and figuring out the shared values of the mathematics community, is democracy in action. I fully believe we are witnessing a historic moment, and it’s weirdly, and happily, happening without police intervention, pepper spray, or drum circles.