Archive

Quants, Models, and the Blame Game

This is crossposted from Naked Capitalism.

Recently a paper came out written by Donald MacKensie and Taylor Spears. It’s about the role of the Gaussian Copula model in the credit crisis, and it’s partly in reaction to Felix Salmon’s article in Wired from February 2009. Both Felix Salmon and Lisa Pollack have written responses to this paper, and they’re quite entertaining and worth a read.

Without going into too many details about the underlying models, which I might do in another post, I wanted to spend some time appreciating this paper for bringing up two issues that I believe far too few people give notice to:

- The politics of being a quant. The pressures on a quant inside an investment bank, a ratings agency, on a trading desk, or for that matter in a risk group are real and need to be understood.

- The narrative of blame. Who gets blamed when a model fails? For that matter, who is responsible for making sure it works at all?

Politics

In the paper, they discuss the concept of a “model dope,” which is a rhetorical device helping you imagine an idiot who ‘unthinkingly believes in the output of the model’. The paper explains that, as far as they could tell, there were no such actual people, that the quants they interviewed all knew the model was and is flawed and overly simplistic.

I completely believe this, and I think it wouldn’t surprise any quant who’s worked in the industry. Quants are the guys who get metaphorically paraded out in front of the bank, with their Ph.D. hanging out as a kind of badge, but when they get back to work are put back in the mines. It’s a trader’s world, or a salesman’s world, and nobody asks the quants for their nuanced opinion on the validity of basing billions of dollars in transactions on these models if the P&L looks good.

Let me say it this way: how many places employing quants to create risk or hedging models have their quants actually in charge of stuff? Very, very few is the answer. The quants are not in charge, they rarely have real power, and as soon as they produce something semi-functional and useful, they no longer own that thing – it’s been taken away from them and is owned by the real power brokers.

Which is not to say the guys in power don’t kind of understand the stuff- they do, they’re smart, but they’re not typically wedded to the idea of intellectual integrity. They typically understand it well enough to see how it can be gamed.

So I don’t think it was the quants that were promoting the wide use of the Gaussian Copula model. In the paper, they explain that it happened for essentially political reasons:

First, it was easy to talk about, since an entire correlation matrix of default was boiled down to one number, “base correlation”:

“If traders in one bank … had to ‘talk using a model’ to traders in a different bank that used a different copula, the Gaussian copula was the most convenient Esperanto: the common denominator that made communication easy.”

Next, it allowed traders to book P&L on the same day they made a trade:

“The most important role of a correlation model, another quant told the first author in January 2007, is as ‘a device for being able to book P&L’,”

Next, once it was widely used, it had staying power just because it was difficult to explain something else, not to mention difficult to admit the current model’s flaws:

“Here, the fact that the Gaussian copula base correlation model was a market standard provided a considerable incentive to keep using it, because it avoided having to persuade accountants and auditors within the bank and auditors outside it of the virtues of a different approach.”

Putting that stuff together, we can see that the mere, lowly quant’s objection, if there was one, that the model sucked was the least of the considerations of the powers-that-were:

“From the viewpoint of both communication and remuneration, therefore, the Gaussian copula was hard to discard.”

Blame

As to the question of blame, that’s also all about power. Just because the objections of quants were likely ignored doesn’t mean we can’t blame them after the fact – that’s another useful thing about quants, since they even admit the models were overly simplistic. Easy fall guys.

By the way, I’m not saying that quants rebelled against the misuse of their models, that they tried their best to warn the public of the known flaws of the Gaussian Copula or any other model for that matter. In fact I don’t know of many quants who did stand up to these assholes, partly because they were paid really well not to, and partly because they were not the alpha males in the place.

I’m just trying to point out that blame can get kind of murky. If a quant comes up with a model and says up front, hey this is just a sketch of something, it’s not totally realistic, but it’s better than nothing, and then the investment bank ignored the quant’s misgivings and bets the house on the model, who is responsible for the resulting risk?

In other words, I’d love the quants to grow some balls, but it’s going to take a major revolution in the power structure for that to be enough.

A Question

The two issues of politics and blame raise for me a larger question in reference to modeling. Namely, why and how to models develop?

[This is a cultural question, and separate from the standard (and interesting) questions you usually hear people ask of a model:

- What does the model claims to do?

- How well it works with real data?, and

- If it is widely employed, how the model affects the market itself?]

- To simplify a businessman’s day. Instead of reading out results from 5 trading desks, we want to dumb it down to one single number, so we employ a modeler to come in and do their best to summarize with one P&L number and one risk number. In other words, it’s the modeler’s job to turn a report into a sound bite. Of course the problem with that model genesis is that it doesn’t necessarily make sense to combine a bunch of numbers into one number. Sometimes the world is actually complex and needs to be understood with a nuanced view. Sometimes a sound bite isn’t enough.

- To sound incredibly smart – in other words, pure spin doctoring. I encounter this more in tech than in finance, where there are enough model-savvy people that you can’t be quite as blithe about hiding bullshit in a model. But this is real in finance too, and I think is used to confuse regulators all the time.

- To dissect, or attempt to dissect, various kinds of ‘unintentional risk’ from ‘intentional positions’. This is the single most dangerous kind of model, because on paper it can look so good, and can seem to work for so long. Credit default swaps can be thought of as manifestation of this goal – an attempt to separate default risk from holding-a-bond risk. The problem we face is that our models are never really that good, or even testable, and there are unintended consequences of these new-fangled contracts that sometimes cause catastrophic events.

- Of course, in quant shops like D.E. Shaw or RenTech or Citadel, there are also quants who try to predict the market or trade superfast on currencies, which is different from the stuff I’ve been talking about which mostly deals with hedging and risk, with different kinds of corresponding risks.

Who should be on the Fed Bank Boards? #OpenFed

Please consider this a civic duty: nominate someone for one of the Fed Bank Boards.

Why? Because:

- these guys regulate the banks,

- they also decide on and implement monetary policy (things like interest rates),

- in times of trouble they also help bail out banks (think Tim Geithner, Lehman, and Bear Stearns)

- the current process is an old boy’s network.

If you haven’t been living under a rock, you might have heard that Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase, sits on the NY Fed Board. There have been a number of calls for his resignation or removal. But as Jonathan Reiss points out in this excellent Huffington Post piece, even better than removing Jamie Dimon and leaving it at that would be to call for all of the Fed Boards to be populated with people who represent the interests of 99% rather than their own narrow business interests. From his article:

…rather than complaining about individual cases, we should fix the process that appointed Dimon and will appoint his successor and 35 other directors to 3-year terms starting January 2013. There are systemic problems with how the directors are selected. The Government Accountability Office studied the bank boards and found they were neither diverse nor representative of the public despite a mandate requiring it. If we work now, this process can be greatly improved.

Did you hear that? The rules already stipulate diverse boards! From a Time article which picked up Reiss’s:

The fact is, the 1913 law creating the central bank was structured to avoid these conflicts. The Federal Reserve System is made up of 12 regional banks, each with nine board members — three of each of three “classes,” A, B, and C. Class A directors are to be from the banking industry and represent large, medium-size, and small banks. Both Class B and Class C directors are supposed to represent non-banking interests — labor, consumers, agriculture, and the like. But bankers select the Class B directors, and the governors of the Federal Reserve select the Class C members, in theory to help ensure their complete independence from the banking industry.

How well does the theory work? Take a look at the list of people on the NY Fed Board, in class C (ignoring classes A and B for now):

|

Lee C. Bollinger (bio) Chair, 2012 |

| Kathryn S. Wylde (bio) Deputy Chair, 2013 President and Chief Executive Officer Partnership for New York City |

| Emily K. Rafferty (bio), 2014 President The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

A bit of background on Kathryn Wylde can be found here, where she was quoted defending Wall Street and trying to shame someone else into doing the same; the article calls for her resignation from the NY Fed. All three of them: Lee Bollinger, Kathy Wylde, and Emily Rafferty, are professional fundraisers. Which means they grovel at the feet of rich people (read: bankers) for a living. This is not the definition of representing “non-banking interests — labor, consumers, agriculture, and the like” I would come up with. In fact if I came up with a definition, there’d be a “no ass-kissing” stipulation.

Is this a problem just for the NY Fed? And why is it happening? According to Reiss:

Dodd-Frank commissioned a study of the bank boards of directors by the GAO. They found in 2010 of the 108 directors, only 5 represented consumers. Agriculture and food processing was better represented. Curiously, the GAO says that several reserve banks said it was “challenging” to find qualified consumer representatives who are interested in these positions. They attributed this to low pay (relative to corporate boards), restrictions on political activity and the requirement that they divest themselves of bank stock holdings. But I find it hard to believe that is the problem.

This is where you come in.

Reiss wants you to nominate qualified people for the local Fed Boards. He’ll compile the list and send them on to the reserve banks, since they seem to be having trouble finding qualified consumer advocates (for whatever reason they are only friends with rich bankers and their fans).

Some good news, the turnover is pretty high: the terms are three years, staggered, which means all 12 Fed Banks make 3 new appointments every year, and by custom nobody serves more than 2 terms. That means that within 6 years we could have a fairly representative board in each Fed if we do this right.

Tweet your nomination to the hashtag #OpenFed.

Jamie Dimon gets a happy ending massage at Banking Committee hearing

Do you guys remember how last week the #OWS Alternative Banking group, along with Occupy the SEC, wrote up some questions for Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase?

Yves Smith also posted those Alt Banking questions on Naked Capitalism, along with some commentary about the senators who were expected to be asking questions of Dimon. Among other things, she mentioned their connections to Wall Street money:

…this is likely to be at most a ritual roughing up. First, the hearing is only two hours, and that includes the usual pontificating at the start of the session. By contrast, Goldman executives were raked over the coals for 10 hours over their dubious collateralized debt obligations. The comparatively easy treatment is no doubt related to the fact that JP Morgan is a major contributor to the five most senior committee members. Per American Banker:

JPMorgan is Banking Committee Chairman Tim Johnson’s second-largest contributor over the last two-plus decades, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which analyzes campaign giving from companies’ employees and their political action committees since 1989. The same is true for the committee’s top Republican, Sen. Richard Shelby, and its second-ranking Democrat, Sen. Jack Reed.

The committee’s number-two Republican, Sen. Mike Crapo, and its third-ranking Democrat, Sen. Charles Schumer, are not far behind their colleagues, with JPMorgan ranking third and fourth, respectively, among their contributors.

Second is that the format of these hearings, with each Senator getting only five minutes each per witness, makes it difficult for a questioner to pin an evasive or clever witness. It won’t be hard for Dimon to either run out the clock or bamboozle his interrogators. But he might, as he did in his hastily-called press conference announcing the losses, make more admissions to the effect that he and senior management weren’t on top of what the group was doing. That would support the notion that JP Morgan’s risk controls were inadequate, which would mean that Dimon’s Sarbanes Oxley certification for 2011, and potentially earlier years, was false.

Who wants to know what actually happened? To find out, go read Matt Taibbi’s Rolling Stones excellent article on the hearing, which is very much in line with what Yves predicted. One of my favorite lines from the article:

This is a guy who just committed a massive blunder with federally-insured money, a guy who is here answering questions because his company, at his direction, clearly and intentionally violated the spirit of the Volcker rule, and these clowns on the Banking Committee are asking Dimon for advice on how to write the rule! It was incredible. Can you imagine senators asking the captain of the Exxon Valdez what his ideas are for new shipping safety regulations – and taking him seriously when he says he doesn’t think they’re a good idea?

Germany’s risk

My friend Nathan recently sent me this Credit Writedowns article on the markets in German risk. There’s basically a single, interesting observation in the article, namely that 5-year bond yields are going down while credit default (CDS) spreads are going up.

When I was working in risk, we’d use both the bond market prices and the CDS market prices to infer the risk of default of a debt issuer – mostly we thought about companies, but we also generalized to countries (although mostly not in Europe!).

For example with bonds, we would split up the yield (how much the bond pays) into two pieces. Namely, you’d get some money back simply because you have to wait for the money, so you’re kind of being compensated for inflation, and then the other part of the money is your compensation for taking on the risk that it might not be paid back at all. This second part is the default risk, and we’d measure default risk of a company like GM in the U.S., for example, by comparing U.S. bond yields to GM yields, the assumption being that there’s no default risk for the U.S. at all. Note this same calculation was typical in lots of countries, but especially the U.S. and Germany, which were considered the two least risky issuers in the world.

With the CDS market, it was a bit more complicated in terms of math but the same idea was underneath – CDS is kind of like an insurance on bonds, although you don’t need to buy the underlying bonds to buy the insurance (something like buying fire insurance on a house you don’t own). The amount you’d have to pay would go up if the perceived risk of default of the issuer went up, all other things being equal.

And that’s what I want to talk about now- in the case of Germany, are all other things equal? I’ve got a short list of things that might be coming into play here besides the risk of a German default.

- Counterparty risk – whereas you only have to worry about Germany defaulting on German bonds, you actually have to worry about whomever wrote the CDS when you buy a CDS. Remember AIG? They went down because they wrote lots of CDS they couldn’t possibly pay out on, and the U.S. taxpayer paid all their bills. But that may not happen again. The counterparty risk is real, especially considering the state of banks in Europe right now.

- People might be losing faith in the CDS market. There’s a group of people who call themselves ISDA and who decide when the issuer of the debt has “defaulted”, triggering the payment of the CDS. But when Greece took a haircut on their debt, it took ISDA a long time to decide it constituted a default. If I’m a would-be CDS buyer, I think hard about whether CDS is a proper hedge for my German bonds (or whatever).

- As the writer of the article mentioned, even though it looks like there’s an “arbitrage opportunity,” people aren’t piling into the trade. Part of this may be because it’s a five year trade and nobody thinks that far ahead when they’re afraid of the next 12 months, which is I think what the author was saying.

- There are rules for some funds about what they are allowed to invest in, and bonds are deemed more elemental and therefore safe than CDSs, for good reason. Another possibility for the German bond/ CDS discrepancy is that certain funds need exposure to highly rated bonds, so German bonds or U.S. bonds, and they can’t substitute writing CDSs for that long exposure.

- Finally, in the formula for how much big a CDS spread is compared to the price, there’s an assumption about how much of a “haircut” the debt owner would have to take on their bond – but this isn’t clear from the outset, it’s determined (as it was in Greece) through a long, drawn-out, political process. If the market thinks this number is changing the spreads on CDS could be moving without the perceived default risk moving.

Using retirement money now

This is a guest post by Micah Warren.

A few weeks ago the Census Bureau reported that more than half of all births in the US are non-white. The social implications are more widely discussed and reported, but the more interesting and worrisome fact is that overall births are sharply declining, especially among whites, ever since the recession hit.

My best guess is that the declines are mostly among the middle class, who are feeling squeezed by student loans, mortgage debt or inability to buy a home, stagnant incomes and employment uncertainty.

Since middle class Americans typically prefer to buy a house before popping out children, it’s fairly simple math: Years ago when the median house price to median income was a little above 2, and nobody was drowning in student loans, and you didn’t have to obtain advanced degrees to make a reasonable wage, most families could comfortably start having children by their late twenties.

Nowadays, the median house is 3 times the median income, people are finishing college/grad school later, have students loans which take a large chunk of what would otherwise be discretionary income, setting the time-line back 5-15 years. To most people, this means less kids. I took a different path, and am learning the hard way that I might have made a choice between a home and children in my (relative) youth.

I wanted to buy a house in my thirties, but savings has been hard to come by with three kids (including twins), student loans, high rent, on one income. I had planned on using retirement funds, until my benefits office, said, “sorry, you can’t touch that money.”

Why?

In their own words, “paternalistic reasons.” They don’t want me to jeopardize my retirement. My retirement has been growing at a very healthy rate, with employer contributions much higher than our discretionary income.

I griped around a bit and the common response seems to be that I would never be so foolish as to mess with the magic money in my retirement funds, to spend today. After all, if had invested $10,000 in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, my holdings would be worth more than $50 million today, right?

Now I have two points in response to this.

- Pulling money out of retirement to put on a house may actually be a good idea for an individual.

- Individuals collectively pulling money out of retirement plans to put on houses is a good idea for the economy as a whole.

The individual

- Retirement funds are in for a tough road. Firstly, the global economy has hit the skids and will take a while to rebuild. Secondly, the aging population: as these guys from the Fed pointed out, the P/E ratio appears to be linked to the ratio of retirees to people in their prime earnings years. This report seems widely ignored and/or downplayed. About $18 trillion is in retirement funds which will be coming out of the market as baby boomers retire and age. Note that those in the financial services industry have a vested interest in convincing people their retirement funds will grow at a 10.8%, which is bats. Most retirement funds are in managed funds, which means that they are being eaten away by the typical 1.5% fees that fund managers take. That takes an optimistic 6% underlying growth rate down to 4.5% which is in the range of most mortgages

- Private mortgage insurance is expensive.

- Rent money is not equity in your home: 5-10 years rent saving for a down payment is a lot of money.

- Tax is tax. Your money will be taxed. Yes, it may be at a lower marginal rate when you retire, but you don’t know that. Further, because compounding is nonlinear, a small change in returns makes a much bigger difference than a difference in tax rates.

The economy

On the other hand, if we do pull money from retirement and put in on homes,

- Home prices may find a bottom sooner. Clearly, if more people like myself have money to spend on houses, more houses will be sold at better prices.

- Finance will have less money and markets will be more stable. (OWS rant ommitted)

- More young middle class people will have more babies. Healthier, well-fed, well-educated children will support the economy in the future. This is the main point here. The greatest investment in our future economy is children today. Money in an account does nothing, unless you still believe in trickle-down theory. The middle class is being depleted, and this will be made much worse in the future due to the simple reason that there will be less middle class children to squeeze. Things could get much uglier years down the road if the population continues to age and retire and expect the money they dumped in the retirement funds to be there without the economy to support it.

Bottom line: A large chunk of younger American couples/families are not able to buy homes and participate in the real economy (rather than just as debtors) and we are in danger of losing out on a whole generation of economic output. This spells a much bigger disaster for our retirement funds than the loss of $20K to home equity.

Instead of choosing a better living standard when our children are young, we are expected to (somewhat selfishly) leave money in a fund that has no guarantee of growth rate, which we have no guarantee will be alive to use, and while optimistically may be spent on glorious retirement, it is also quite likely these funds will be depleted in a few short months by end-of-life care. In the meantime, Wall Street plays puff-puff-give with the money.

I personally would gladly accept financial comfort while my children are young in exchange for a smaller chunk of money later, which gives me little comfort at all, because there is no earthly way to discern what this money will mean to me when I am 70. On the other hand, I can tell you exactly how much a 20% down payment on a $300,000 house is, today.

Questions for Jamie Dimon

Jamie Dimon is meeting with Congress today. Occupy the SEC and the Alternative Banking Working Group jointly wrote a bunch of questions for the Senators to ask him. Please read the letter and some interesting facts about the Senators scheduled to talk to Dimon today on this Naked Capitalism post.

I don’t trust politicians more than I trust bankers

There are certain people who are obsessed with the way money is created in the U.S. – I call them “money creationists”. Some of these people are friends of mine from Occupy, and I really enjoy and like them.

But I don’t agree with them, and here’s why. Because I don’t trust politicians more than I trust bankers. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I don’t trust bankers. But I really don’t trust politicians.

The reason this comparison comes up is this. The way money is created through the Fed lending window is described here, in an article that could have been written by my friends, although I don’t think I’ve met Gar. Pay attention to the following concept which the writer is proposing:

Why, you might ask, doesn’t the Federal Reserve Board simply “create” money (as it does all the time) and lend it at 0.75 percent to the government (rather than let the banks do it) to pay for important public goods and to settle its debts? (Our bridges are falling down; not a bad thing in which to invest.)

As soon as I hear this I think, holy fuck let’s not even go there! The image of unlimited cash machines directly bankrolling the whims of Congress is just too much. But wait, here’s where the money-creationists get really confused – they give themselves away in fact:

… if a “public bank” were set up that operates just the way private banks are run today, including making profits for the owners – who in this case would obviously be the public – i.e. the government.

What? When was the last time the public is the same thing as the government? In this universe, for whatever reason, politicians have been wished away and all we have left are well-meaning would-be bridge builders facing off against evil venal bankers. But that’s not the world I live in.

To my money-creationist friends: there are stewards of the government, and they’re called politicians, and they love money. They are just as corrupt as bankers. It’s not a good idea to give them a printing press. Let’s instead think of a way to persuade them to require reasonable capital requirements of the banks so they don’t get to do crazy shit, if they can get their hands off of financial lobbyist money for more than fifteen minutes.

What if the bond markets priced in actual risk?

A friend sent me this article written by Daniel Gross, which talks about how taxpayers in Europe and in the U.S. are paying for the mistakes of bondholders. First he starts with Ireland:

When Ireland’s large private banks collapsed spectacularly a few years ago, the Irish government formally assumed the debts of the private banks. To ensure that bondholders of Irish banks would remain whole, the government undertook a massive bailout. To pay for it, it has inflicted vicious austerity on its populace.

He moves on to Greece:

As Liz Alderman and Jack Ewing reported in the New York Times this week, about two-thirds of the $177 billion in European aid to Greece given since May 2010 has been used to make payments to bondholders and other lenders. The upshot: Greece is imposing significant austerity on its citizens for the sake of preserving the value of bondholders.

And the U.S.:

Yes, it’s true that the U.S. in 2008 and 2009 acted to keep bondholders from taking big losses. The taxpayers formally assumed the debt of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac without insisting bondholders take any haircut, just as the Irish taxpayers formally assumed the debts of their large banks. That was a big and expensive mistake. In a time of austerity, the U.S. government is channeling tax payer funds to make interest payments on bonds that were first issued by for-profit entities.

He points out that Spain appears to be taking the same approach, and that the actual people of Ireland and Greece are having second thoughts about paying all these bills, expressed through who they are voting for. I believe it’s left to the reader to wonder what’s going to happen to Spain.

Gross suggests a different tact for governments to use, namely to ignore old debt and to provide insurance for new debt issued by the banks and other private companies. The U.S. did this during the crisis, it was called the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program. His point is that we’ve made money off this program and we’ve let lots of really insolvent banks fail as well.

On the other hand, I’d argue, we haven’t let the big banks fail, so there’s a limit to its effectiveness (but I won’t blame this program for that, because that’s a problem of political will). And it’s of course not altogether clear that the insurance it sold was sold at market value, since if it had been, I’m guessing it wouldn’t have been such a boon to a given company to issue debt and pay for insurance versus just issuing debt at a higher risk premium. In other words, I think the “Liquidity” in “Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program” is key.

But he’s got it basically right- taxpayers are definitely on the hook for risky bets other people took. And backups and guarantees by governments definitely skews the bond market. Specifically, big companies end up paying less than they should given their risk, and the taxpayers foot the bill in situations of default (which aren’t allowed to actually be defaults with respect to the bondholders).

So sufficiently big companies are paying too little for debt. That’s about half the story though. The other half is how normal people are paying too much for debt.

For example, with student debt, Bloomberg recently reported that private issuers of student debt are charging as much as credit card companies:

Tovar, who lives with her parents in the Chicago suburb of Blue Island, owes $55,600 to Chase Student Loans, a unit of JPMorgan, according to a May 17 statement provided by her. A loan for $24,794 carries an interest rate of 10.25 percent, as does a second loan for more than $2,619. A third for $28,187 has a rate of 8.97 percent. She has a balance of $42,326 in loans from a different lender.

Given that these loans are effectively undischargable through bankruptcy, what is the real risk for private issuers in getting their money back? What would a fair market price be for these loans? And why don’t we have a fair market?

Who will Regulate the Superheroes on Wall Street?

This is a guest post by Elizabeth Friedrich, a member of Occupy the SEC.

Wall Street has grown to celebrate superheroes like Lloyd Blankfein and Jamie Dimon for their superior management skills and keen business sense. We have come to praise and applaud reckless risk-takers on the assumption that the markets always know best.

Insider Wall Street leaders like Jamie Dimon are viewed to possess special powers. In fact, many believe that Dimon, who led JP Morgan out of the financial crisis, is a banking prodigy who could do no wrong. But even Dimon is helpless in the face of reckless risk-taking behavior by his employees, as shown by the trader Bruno Iksil who lost $3 billion dollars and counting as part of JP Morgan’s CIO office. “Star traders” like Iksil structure their trades in such a complicated way that the average person could never understand them. We have no way of knowing whether the hedges that the CIO office put on actually “hedged” the original position. Such complexity, conveniently, can also serve as a powerful tool to refute public outcry.

The question here is this: Why create such risk in the first place? Or, more importantly: Why create the type of transactions that require a superman to oversee them?

Since the Volcker Rule is still being finalized, banking institutions will continue to take on these risks as long as they are allowed or exempted to do so. However, banks should face the same consequences as the rest of society. The “London Whale” trades created massive disruptions in an already fragile market and, ironically, they have caused unrest and disgust in the hedge fund community – the very community that loves unregulated market competition. Why don’t we hold banks to their own standards and stop giving them a pass when they fail?

Occupy the SEC will be marching today calling for the S.E.C. to investigate Jamie Dimon for violation of the disclosure requirements of Sarbanes-Oxley Act. We will also recommend that the S.E.C. make a criminal referral to the Department of Justice. Many people are frustrated with the slap-on-the-wrist treatment that Wall Streeters enjoy; random petty criminals are sentenced to hard jail time but the trader who loses billions of dollars is told not to do that again. The JP Morgan Chase debacle is symptomatic of a broken regulatory system.

Even if there are no criminal charges against Jamie Dimon, the American public would have been well-served to see Wall Street have its day in court. The S.E.C. has to uphold its foundational principles: 1) public companies offering securities to investors must tell the truth about their business, the securities, and the risks involved in investing; and 2) people who sell and trade securities must treat investors fairly and honestly, putting their investors’ interests first.

It is fairly simple: if S.E.C. officials find out that a company has done wrong they have the power to investigate, issue civil penalties, and refer the case to the Department of Justice for criminal prosecution. As many financial experts and white-collar crime lawyers have said, the S.E.C. has not fully utilized its authority, as demonstrated by the treatment of Dick Fuld and Jon Corzine.

The function of a financial institution is not merely to manage risk, but to act primarily as the steward of society’s assets and smart allocation of capital. We hope that the S.E.C will help re-examine the priorities of Too Big To Fail financial institutions. Finally, the current culture corrodes and disrupts sound business practices and stunts the rehabilitation of our current financial system. The S.E.C. is an imperfect vehicle (as evidenced by its lackluster approach to its duties leading up and during the financial crisis) but it’s the only vehicle we have. If they don’t do their job – who will?

Occupy the SEC is a group of concerned citizens, activists, and financial professionals with decades of collective experience working at many of the largest financial firms in the industry. Occupy the SEC filed a 325-page comment letter on the Volcker Rule NPR, which is available at http://occupythesec.org.

Regulation is not a dirty word

Regulation has gotten a bad rap recently. It’s a combination of it being associated to finance, or big business, and it being complicated, and involving lobbyists and lawyers – it’s sleazy and collusive by proxy, and there are specific regulators that haven’t exactly been helping the cause. Most importantly, though, the concept of regulation has been slapped with a label of “bad for business = bad for the struggling economy”.

But I’d like to argue that regulation is not a dirty word – it’s vital to a functioning economy and culture.

And the truth is, we are lacking strong and enforced regulation on businesses in this country. Sometimes we don’t have the regulation, but sometimes we do and we don’t enforce it. I want to give three examples from yesterday’s news on what we’re doing wrong.

First, consider this article about data and privacy in the internet age. It starts out by scaring you to death about how all of your information, even your DNA code, is on the web, freely accessible to predatory data gatherers. All true. And then at the end it’s got this line:

“Regulation is coming,” she says. “You may not like it, you may close your eyes and hold your nose, but it is coming.”

What? How is regulation the problem here? The problem is that there’s no regulation, it’s the wild west, and a given individual has virtually no chance against enormous corporate data collectors with their very own quant teams figuring out your next move. This is a perfect moment for concerned citizens to get into the debate about who owns their data (my proposed answer: the individual owns their own data, not the corporation that has ferreted it out of an online persona) and how that data can be used (my proposed answer: never, without my explicit permission).

Next, look at this article where Bank of America knew about the massive losses on Merrill after agreeing to acquire them in September 2008 but its CEO Ken Lewis lied to shareholders to get them to vote for the acquisition in December 2008. The fact that Lewis lied about Merrill’s expected losses is not up for debate. From the article:

… Mr. Singer declined to comment on the filing. But the document submitted to the court said that Mr. Lewis’s “sworn admissions leave no genuine dispute that his statement at the December 5 shareholder meeting reiterating the bank’s prior accretion and dilution calculations was materially false when made.”

What I want to draw your attention to is the following line from the article (emphasis mine):

…the former chief executive did not disclose the losses because he had been advised by the bank’s law firm, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, and by other bank executives that it was not necessary.

Just to be clear, Lewis didn’t want to tell bad news to shareholders about the acquisition, because then he’d lost his shiny new investment bank, and he checked with his lawyers and they decided he didn’t need to admit the truth. That is a pure case of unenforced regulation. It is actually illegal to do this, but the lawyers were betting they could get away with it anyway.

Finally, consider this video describing what was happening inside MF Global in the days leading up to its collapse. Namely, the borrowing of customer money is hard to track because they did it all by hand. No, I’m sorry. Nobody does stuff with money without using a computer anymore. The only reason to do this by hand is to avoid leaving a paper trail because you know you’re about to do something illegal. I’m no accounting regulation expert but I’m sure this is illegal. Another case of unenforced regulation, or at worst, regulation that should exist.

Why do people think regulation is bad again? Does it really stifle business? Is it bad for the economy? In the above cases, consider this. The fact that we don’t have clear rules will cause plenty of people to avoid using all sorts of social media at all for fear of their data being manipulated. We have plenty of people avoiding investing in banks because they don’t trust the statements of bank CEO’s. And we have people avoiding becoming customers of futures exchanges for fear their money will be stolen. These facts are definitely bad for the economy.

The truth is, business thrives in environments of clear rules and good enforcement. That means strong, relevant, and enforced regulation.

Combining priors and downweighting in linear regression

This is a continuation of yesterday’s post about understand priors on linear regression as minimizing penalty functions.

Today I want to talk about how we can pair different kinds of priors with exponential downweighting. There are two different kinds of priors, namely persistent priors and kick-off priors (I think I’m making up these terms, so there may be other official terms for these things).

Persistent Priors

Sometimes you want a prior to exist throughout the life of the model. Most “small coefficients” or “smoothness” priors are like this. In such a situation, you will aggregate today’s data (say), which means creating an matrix and an

vector for that day, and you will add

to

every single day before downweighting your old covariance term and adding today’s covariance term.

Kick-Off Priors

Other times you just want your linear regression to start off kind of “knowing” what the expected answer is. In this case you only add the prior terms to the first day’s matrix and

vector.

Example

This is confusing so I’m going to work out an example. Let’s say we have a model where we have a prior that the 1) coefficients should look something like

and also that 2) the coefficients should be small. This latter condition is standard and the former happens sometimes when we have older proxy data we can “pretrain” our model on.

Then on the first day, we find the matrix and

vector coming from the data, but we add a prior to make it closer to

:

How should we choose ? Note that if we set

we have no prior, but on the other hand if we make

absolutely huge, then we’d get

This is perfect, since we are trying to attract the solution towards

So we need to tune

to be somewhere in between those two extremes – this will depend on how much you believe

.

On the second day, we downweight data from the first day, and thus we also downweight the prior. We probably won’t “remind” the model to be close to

anymore, since the idea is we’ve started off this model as if it had already been training on data from the past, and we don’t remind ourselves of old data except through downweighting.

However, we still want to remind the model to make the coefficients small – in other words a separate prior on the size of coefficients. So in fact, on the first day we will have two priors in effect, one as above and the other a simple prior on the covariance term, namely we add for some other tuning parameter

. So actually the first day we compute:

And just to be really precise, of we denote by the downweighting constant, on day 2 we will have:

,

, and

An easy way to think about priors on linear regression

Every time you add a prior to your multivariate linear regression it’s equivalent to changing the function you’re trying to minimize. It sometimes makes it easier to understand what’s going on when you think about it this way, and it only requires a bit of vector calculus. Of course it’s not the most sophisticated way of thinking of priors, which also have various bayesian interpretations with respect to the assumed distribution of the signals etc., but it’s handy to have more than one way to look at things.

Plain old vanilla linear regression

Let’s first start with your standard linear regression, where you don’t have a prior. Then you’re trying to find a “best-fit” vector of coefficients for the linear equation

. For linear regression, we know the solution will minimize the sum of the squares of the error terms, namely

.

Here the various ‘s refer to the different data points.

How do we find the minimum of that? First rewrite it in vector form, where we have a big column vector of all the different ‘s and we just call it

and similarly we have a matrix for the

‘s and we call it

Then we are aiming to minimize

Now we appeal to an old calculus idea, namely that we can find the minimum of an upward-sloping function by locating where its derivative is zero.

Moreover, the derivative of is just

or in other words

In our case this works out to

or, since we’re taking the derivative with respect to

and so

and

are constants, we can rewrite as

Setting that equal to zero, we can ignore the factor of 2 and we get

or in other words the familiar formula:

.

Adding a prior on the variance, or penalizing large coefficients

There are various ways people go about adding a diagonal prior – and various ways people explain why they’re doing it. For the sake of simplicity I’ll use one “tuning parameter” for this prior, called (but I could let there be a list of different

‘s if I wanted) and I’ll focus on how we’re adding a “penalty term” for large coefficients.

In other words, we can think of trying to minimize the following more complicated sum:

.

Here the ‘s refer to different data points (and

is the number of data points) but the

‘s refer to the different

coefficients, so the number of signals in the regression, which is typically way smaller.

When we minimize this, we are simultaneously trying to find a “good fit” in the sense of a linear regression, and trying to find that good fit with small coefficients, since the sum on the right grows larger as the coefficients get bigger. The extent to which we care more about the first goal or the second is just a question about how large is compared to the variances of the signals

This is why

is sometimes called a tuning parameter. We normalize the left term by

so the solution is robust to adding more data.

How do we minimize that guy? Same idea, where we rewrite it in vector form first:

Again, we set the derivative to zero and ignore the factor of 2 to get:

Since is symmetric, we can simplify to

or:

which of course can be rewritten as

If you have a prior on the actual values of the coefficents of

Next I want to talk about a slightly fancier version of the same idea, namely when you have some idea of what you think the coefficients of should actually be, maybe because you have some old data or some other study or whatever. Say your prior is that

should be something like the vector

and so you want to penalize not the distance to zero (i.e. the sheer size of the coefficients of

) but rather the distance to the vector

Then we want to minimize:

.

We vectorize as

Again, we set the derivative to zero and ignore the factor of 2 to get:

so we can conclude:

which can be rewritten as

A low Fed rate: what does it mean for the 99%?

I’m no economist, so it always takes me quite a bit of puzzling to figure out macro-economic arguments. Recently I’ve been wondering about the Fed’s promise to keep rates low for extended periods of time. Specifically, I’ve been wondering this: whom does that benefit?

[As an aside, it consistently pisses me off that the people trading in the market, who claim to be all about “free markets” and against “interference” from regulators, also are the ones who whine for a Fed intervention or quantitative easing when bad economic data comes out. So which is it, do you want freedom or do you want a babysitter?]

Here’s the argument I’ve gleaned from the St. Louis Fed’s webpage. When the Fed lowers (short-term) rates, it makes it easier to borrow money, it makes it easier for banks to profit from the difference between long-term and short-term rates, and it potentially can cause inflation (and bubbles) since, now that everyone has borrowed more, there’s more demand, which raises prices. And inflation is good for debtors, because over time their debts are worth less.

One thing about the above argument stands out as false to me, at least for the majority of the 99%. Namely, many of them are already indebted up their eyeballs, so who is going to give them more money? And what would they buy with that money?

In other words, if the assumption is that everyone is getting easy loans, I haven’t seen evidence of this. Wouldn’t we be hearing about people refinancing their homes for awesome rates and thereby avoiding foreclosure? How many stories have you heard like that?

If not everyone is getting easy loans, and if in fact only the 1% and banks are getting those gorgeously low-interest loans, then it’s not clear this will be sufficient to spur demand and cause inflation. And inflation really would help the 99%, but only of course if wages kept up with it. Instead we have not seen high inflation and wages haven’t even been keeping up with what inflation we do see.

So let’s re-examine who is benefiting from low Fed rates. I’m gonna guess it’s mostly the banks, and a few private equity firms that are borrowing tons of money to buy up great swaths of foreclosed homes so they can turn around and profit on renting them out to the people who were foreclosed on.

I’m not necessarily advocating that we raise the Fed rates. But next time I hear someone say, “low Fed rates benefit debtors” I’m going to clarify, “low Fed rates benefit banks.”

When “extend and pretend” becomes “delay and pray”

When banks have non-performing loans, they sometimes don’t want to admit it. So instead of calling it a loss, because the debtor can’t pay, they simply rewrite the contract so that it has been extended. This way the debtor is not technically behind in payments and the creditor can pretend that the corresponding debt on their books is worth something. It’s called extend and pretend, and it’s not new.

And actually, this ploy sometimes works. After all, sometimes the debtor just needs a bit more time – they could be temporarily unable to pay for whatever reason. Indeed it would be a convenient option for people who are just in need of a few more months to get back on their feet and not lose their house (typically this offer is not extended to individuals, since their loans are too small to fret over).

Make no mistake: there is a real incentive for the banks to do this. Currently the worst example of this method is in Spain, where the banks are finding it politically impossible to admit their losses. The government doesn’t want to hear it, because they will need to bail them out, and their borrowing costs are already precariously high. The Eurozone leaders don’t want to think Spain is as bad off as Greece, because they can’t handle that kind of problem. The investors don’t want to hear it because their investments will be worth less once the news comes out (an example of asymmetric information if there ever was one – shouldn’t investors already know how much extending and pretending is really going on?). And of course the lenders themselves don’t want to admit they are working at an insolvent institution, especially when they probably each know other institutions that are even more insolvent.

What are the chances that this method of delay and pray will work for Spain? With an enormous housing bubble and 24% unemployment, not good. Most of the bad loans that have been extended after non-payment are housing market related. Half of the lenders are zombie, which means insolvent but still technically open for business. Essentially the numbers are just too high and now everybody knows it (see this Bloomberg article for the low-down on Spain).

So what should Spain be doing?

I like to point to the example of Iceland, which admitted its debts early on (although it has to be admitted they didn’t have much of a choice), defaulted on a bunch of international debt, bailed out their citizens from onerous home debt, and is recovering nicely (see this Bloomberg article for more on Iceland).

Oh, and let me add that they (Iceland) are indicting and jailing the bankers who got them into the mess, to the tune of 200 indictments. Considering the U.S. has a population 981 times as large, that would be equivalent to us indicting 196,341 bankers. In fact we’ve indicted no top bank executive, although everyone will be relieved to know the SEC “sanctioned” 39 people for the housing market debacle. Phew!

Unfortunately, it would be tough for Spain to repeat that act- it depended on the fact that Iceland has control over its economic choices, but Spain is part of the Eurozone and as such is embedded in a huge network of agreements and debts and currency with the other Eurozone nations.

In some sense, Spain is being forced into the zombie bank situation by a lack of options. Unless I’m missing something – would love to be wrong!

Everybody lies (except me)

There’s an interesting article in the Wall Street Journal from yesterday about lying. In the article it explains that everybody lies a little bit and, yes, some people are serious liars, but the little lies are the more destructive because they are so pervasive.

It also explains that people only lie the amount they can get away with to themselves (besides maybe the out-and-out huge liars, but who knows what they’re thinking?).

When I read this article, of course, I thought to myself, I don’t lie even a little bit! And that kind of proved their point.

So here’s the thing. They also explained that people lie a bit more when they are in a situation where the consequences of lying are more abstract (think: finance) and that they lie more when they are around people they perceive as cheating (think: finance). So my conclusion is that finance is populated by liars, but that’s because of the culture that already exists there: most people just amble in as honest as anyone else and become that way.

Of course, every field has that problem, so it’s really not fair to single out finance. Except it is fair to single out any place where you can cheat easily, where there are ample opportunities to lie and profit off of lies.

One cool thing about the article is that they have a semi-solution, namely to remind people of moral rules right before the moment of possible lying. This can be reciting the ten commandments or swearing on a bible, which for some reason also works for atheists (but wouldn’t stop me from lying!), or could be as simple as making someone sign their name just before lying (or, even better, just before not lying) on their auto insurance forms.

Can we use this knowledge somehow in setting up the system of finance?

The result where people are more likely to lie when they know who the victim of their lie is may explain something about how, back when banks lent out money to people and held the money on their books, we had less fraud (but not zero fraud of course). The idea of personally knowing who the other person is in a transaction seems kind of important.

The idea that we make people swear they are telling the truth and sign their name seems easy enough, but obviously not infallible considering the robo-signing stuff. I wonder if we can use more tricks of the honesty trade and do things like make sure each person signing is also being videotaped or something, maybe that would also help.

Unfortunately another thing the article said was that having been taught ethics some time in the past actually doesn’t help. So it’s less to do with knowledge and more to do with habit (or opportunity), it seems. Food for thought as I’m planning the ethics course for data scientists.

An open source credit rating agency now exists!

I was very excited that Marc Joffe joined the Alternative Banking meeting on Sunday to discuss his new open source credit rating model for municipal and governmental defaults, called Public Sector Credit Framework, or PCSF. He’s gotten some great press, including this article entitled, “Are We Witnessing the Start of a Ratings Revolution?”.

Specifically, he has a model which, if you add the relevant data, can give ratings to city, state, or government bonds. I’ve been interested in this idea for a while now, although more at the level of publicly traded companies to start; see this post or this post for example.

His webpage is here, and you will note that his code is available on github, which is very cool, because it means it’s truly open source. From the webpage:

The framework allows an analyst to set up and run a budget simulation model in an Excel workbook. The analyst also specifies a default point in terms of a fiscal ratio. The framework calculates annual default probabilities as the the proportion of simulation trials that surpass the default point in a given year.

On May 2, we released the initial version of the software and two sample models – one for the US and one for the State of California – which are available on this page. For PSCF project to have an impact, we need developers to improve the software and analysts to build models. If you care about the implicatiions of growing public debt or you believe that transparent, open source technology can improve the standard of rating agency practice, please join us.

If you are a developer interested in helping him out, definitely reach out to him, his email is also available on the website.

He explained a few things on Sunday I want to share with you. They are all based on the kind of conflict of interest ratings agencies now have because they are paid by the people who they rate. I’ve discussed this conflict of interest many times, most recently in this post.

First, a story about California and state bonds. In the 2000’s, California was rated A, which is much lower than AAA, which is where lots of people want their bond ratings to be. So in order to achieve “AAA status,” California paid a bond insurer which was itself rated AAA. That is, through buying the insurance, the ratings status is transferred. In all, California paid $102 million for this benefit, which is a huge amount of money. What did this really buy though?

At some point their insurer, which was 139 times leveraged, was downgraded to below A level, and that meant that the California bonds were now essentially unbacked, so down to A level, and California had to pay higher interest payments because of this lower rating.

Considering the fact that no state has actually defaulted on their bonds in decades, but insurers have, Marc makes the following points. First, states are consistently under-rated and are paying too much for debt, either through these insurance schemes, where they pay questionable rates for questionable backing, or directly to the investors when their ratings are too low. Second, there is actually an incentive for ratings agencies to under-rate states, namely it gives them more business in rating the insurers etc. In other words they have an eco system of ratings rather than a state-by-state set of jobs.

How are taxpayers in California not aware of and incensed by the waste of $102 million? I would put this in the category of “too difficult to understand” for the average taxpayer, but that just makes me more annoyed. That money could have gone towards all sorts of public resources but instead went to insurance company executives.

Marc then went on to discuss his new model, which avoids this revenue model, and therefore conflict of interest, and takes advantage of the new format, XBRL, that is making it possible to automate ratings. It’s my personal belief that it will ultimately be the standardization of financial statements in XBRL format that will cause the revolution, more than anything we can do or say about something like the Volcker rule. Mostly this is because politicians and lobbyists don’t understand what data and models can do with raw standardized data. They aren’t nerdy enough to see it for what it is.

What about a revenue model for PCSF? Right now Marc is hoping for volunteer coders and advertising, but he did mention that there are two German initiatives that are trying to start non-profit, transparent ratings agencies essentially with large endowments. One of them is called INCRA, and you can get info here. The trick is to get $400 million and then be independent of the donors. They have a complicated governance structure in mind to insulate the ratings from the donors. But let’s face it, $400 million is a lot of money, and I don’t see Goldman Sachs in line to donate money. Indeed, they have a vested interest in having all good information kept internal anyway.

We also talked about the idea of having a government agency be in charge of ratings. But I don’t trust that model any more than a for-profit version, because we’ve seen how happy governments are at being downgraded, even when they totally deserve it. Any governmental ratings agencies couldn’t be trusted to impartially rate themselves, or systemically important companies for that matter.

I’m really excited about Marc’s model and I hope it really does start a revolution. I’ll be keeping an eye on things and writing more about it as events unfold.

Recovery begins when addiction ends: an open letter to Jamie Dimon (#OWS)

Posted here on Naked Capitalism, written by the Alternative Banking group of Occupy Wall Street.

Please spread widely!

Who wants Jamie Dimon’s job?

It’s Jamie Dimon day for me today, I’ve offered to write a first draft of a Alternative Banking piece on the JP Morgan $2,000,000,000 “hedging loss” that he announced last week and which resulted in a 12% stock price loss in the past 5 trading days. There are many sordid details to wade through to prepare, but here’s the question I’d like you to think about for a minute.

Who would want to take that job once he resigns or gets booted?

I’m thinking the world is divided into people who are realistic about how ridiculously large and unmanageable any too-big-to-fail bank actually is, and the psychopaths that think they are the guy who can tame the beast. Jamie Dimon was definitely one of the most psychopathic of the original crowd of CEO’s left over from before the credit crisis, and honestly he played his part so well it was amazing. It didn’t hurt that JP Morgan was never the worst example of any kind of underhanded and outrageous risk-taking, until now.

For example: Dimon consistently and vehemently complained about any regulation as “strangulation” for his industry, and as anti-american. He was so adamant that people (read: regulators, politicians, and the Fed) took him very very seriously and he was on the verge of fatally weakening the Volcker Rule. We’ll see how that pans out now, but I’m hopeful for something a bit less pathetic.

Is there anyone left who can take that over? Who has the required psychopathic balls?

Evil finance should contribute to open source

This is a guest post from an friend who wishes to remain anonymous.

I’ve been thinking lately that a great way for “evil finance” to partially atone for its sins is to pay a lot of money to improve open source libraries like numpy/scipy/R. They could appeal to the whole “this helps cancer research” theme, which I honestly believe is true to some extent. For example, if BigData programs ran 10% faster because of various improvements, and you think there’s any value to current medical research, and the cancer researchers use the tools, then that’s great and it’s also great PR.

To some extent I think places like Google get some good publicity here (I personally think of them as contributing to open source, not sure how true it really is), and it seems like Goldman and others could and should do this as well — some sliver of their rent collection goes into making everybody’s analysis run faster and some of that leads to really important research results.

Personally I think it’s true even now; Intel has been working for years on faster chips, partially to help price crazy derivatives but it indirectly makes everybody’s iPhone a little cheaper. Contributing directly to open source seems like a direct way to improve the world and somewhat honestly claim credit, while getting huge benefit.

And it simultaneously has nice capitalist and socialist components, so who wouldn’t be happy?

There are actual problems banks care about solving faster, a lot of which uses pretty general purpose open source libraries, and then there are the maintainers of open source libraries doing this nice altruistic thing but I’m sure could do even better if only they didn’t have a “day job” or whatever.

And if the banks don’t want to give away too much information, they can just make sure to emphasise the general nature of whatever they help fund.

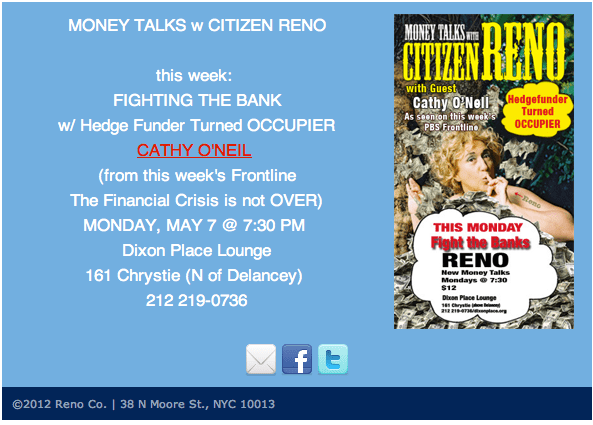

Performing tomorrow night with Reno

I’ll be in the Lower East Side tomorrow night, at the Dixon Place Lounge, talking finance with Reno, who some of you may know. Here’s more info: