Archive

10 reasons to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting tomorrow (#OWS)

The Alternative Banking group of #OWS is showing up bright and early tomorrow morning to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting. Details are: we meet outside the Hilton Hotel, Sixth Avenue between 53rd and 54th Streets, tomorrow, April 24th, from 8-10 am. We’ve already made some signs (see below).

Here are ten reasons for you to join us.

1) The Glass-Steagall Act, which had protected the banking system since 1933, was repealed in order to allow Citibank and Traveler’s Insurance to merge.

In fact they merged before the act was even revoked, giving us a great way to date the moment when politicians started taking orders from bankers – at the time, President Bill Clinton publicly declared that “the Glass–Steagall law is no longer appropriate.”

2) The crimes Citi has committed have not been met with reasonable punishments.

From this Bloomberg article:

In its complaint against Citigroup, the SEC said the bank misled investors in a $1 billion fund that included assets the bank had projected would lose money. At the same time it was selling the fund to investors, Citigroup took a short position in many of the underlying assets, according to the agency.

The SEC only attempted to fine Citi $285 million, even though Citi’s customers lost on the order of $600 million from their fraud. Moreover, they were not required to admit wrongdoing. Judge Rakoff refused to sign off on the deal and it’s still pending. Citi is one of those banks that is simply too big to jail.

3) We’d like our pen back, Mr. Weill. Going back to repealing Glass-Steagall. Let’s take an excerpt from this article:

…at the signing ceremony of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley, aka the Glass Steagall repeal act, Clinton presented Weill with one of the pens he used to “fine-tune” Glass-Steagall out of existence, proclaiming, “Today what we are doing is modernizing the financial services industry, tearing down those antiquated laws and granting banks significant new authority.”

Weill has since decided that repealing Glass-Steagall was a mistake.

4) Do you remember the Plutonomy Memos? I wrote about them here. Here’s a tasty excerpt which helps us remember when the class war was started and by whom:

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization… Since we think the plutonomy is here, is going to get stronger… It is a good time to switch out of stocks that sell to the masses and back to the plutonomy basket.

5) Robert Rubin – enough said. To say just a wee bit more, let’s look at the Bloomberg Businessweek article, “Rethinking Robert Rubin”:

Rubinomics—his signature economic philosophy, in which the government balances the budget with a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, driving borrowing rates down—was the blueprint for an economy that scraped the sky. When it collapsed, due in part to bank-friendly policies that Rubin advocated, he made more than $100 million while others lost everything.

That $100 million was made at Citigroup, which was later bailed out because of bets Rubin helped them make. He has thus far shown no remorse.

6) The Revolving Door problems Citigroup has. Bill Moyers has a great article on the outrageous revolving door going straight from banks to the Treasury and the White House. What with Rubin and Lew, Citigroup seems pretty much a close second behind Goldman Sachs for this sport.

7) The bailout. Citigroup took $100 billion from the Fed at the height of the bailout in January 2009.

8) The bailout was actually for Citigroup. If you’ve read Sheila Bair’s book Bull by the Horns, you’ll see the bailout from her inside perspective. And it was this: that Citigroup was really the bank that needed it worst. That in fact, the whole bailout was a cover for funneling money to Citi.

9) The ongoing Fed dole. The bailout is still going on – and Citigroup is currently benefitting from the easy money that the Fed is offering, not to mention the $83 billion taxpayer subsidy. WTF?!

10) Lobbying for yet more favors. Citi spent $62 million from 2001 to 2010 on lobbying in Washington. What’s their return on that investment, do you think?

Join us tomorrow morning! Details here.

How to reinvent yourself, nerd version

I wanted to give this advice today just in case it’s useful to someone. It’s basically the way I went about reinventing myself from being a quant in finance to being a data scientist in the tech scene.

In other words, many of the same skills but not all, and many of the same job description elements but not all.

The truth is, I didn’t even know the term “data scientist” when I started my job hunt, so for that reason I think it’s possibly good and useful advice: if you follow it, you may end up getting a great job you don’t even know exists right now.

Also, I used this advice yesterday on my friend who is trying to reinvent himself, and he seemed to find it useful, although time will tell how much – let’s see if he gets a new job soon!

Here goes.

- Write a list of things you like about jobs: learning technical stuff, managing people, whatever floats your boat.

- Next, write a list of things you don’t like: being secretive, no vacation, office politics, whatever. Some people hate working with “dumb people” but some people can’t stand “arrogant people”. It makes a huge difference actually.

- Next, write a list of skills you have: python, basic statistics, math, managing teams, smelling a bad deal, stuff like that. This is probably the most important list, so spend some serious time on it.

- Finally, write a list of skills you don’t have that you wish you did: hadoop, knowing when to stop talking, stuff like that.

Once you have your lists, start going through LinkedIn by cross-searching for your preferred city and a keyword from one of your lists (probably the “skills you have” list).

Every time you find a job that you think you’d like to have, take note of what skills it lists that you don’t have, the name of the company, and your guess on a scale of 1-10 of how much you’d like the job into a spreadsheet or at least a file. This last part is where you use the “stuff I like” and “stuff I don’t like” lists.

And when you’ve done this for a long time, like you made it your job for a few hours a day for at least a few weeks, then do some wordcounts on this file, preferably using a command line script to add to the nerdiness, to see which skills you’d need to get which jobs you’d really like.

Note LinkedIn is not an oracle: it doesn’t have every job in the world (although it might have most jobs you could ever get), and the descriptions aren’t always accurate.

For example, I think companies often need managers of software engineers, but they never advertise for managers of software engineers. They advertise for software engineers, and then let them manage if they have the ability to, and sometimes even if they don’t. But even in that case I think it makes sense: engineers don’t want to be managed by someone they think isn’t technical, and the best way to get someone who is definitely technical is just to get another engineer.

In other words, sometimes the “job requirements” data on LInkedIn dirty, but it’s still useful. And thank god for LinkedIn.

Next, make sure your LinkedIn profile is up-to-date and accurate, and that your ex-coworkers have written letters for you and endorsed you for your skills.

Finally, buy a book or two to learn the new skills you’ve decided to acquire based on your research. I remember bringing a book on Bayesian statistics to my interview for a data scientist. I wasn’t all the way through the book, and my boss didn’t even know enough to interview me on that subject, but it didn’t hurt him to see that I was independently learning stuff because I thought it would be useful, and it didn’t hurt to be on top of that stuff when I started my new job.

What I like about this is that it looks for jobs based on what you want rather than what you already know you can do. It’s in some sense the dual method to what people usually do.

Tax haven in comedy: the Caymans (#OWS)

This is a guest post by Justin Wedes. A graduate of the University of Michigan with degrees in Physics and Linguistics with High Honors, Justin has taught formerly truant and low-income youth in subjects ranging from science to media literacy and social justice activism. A founding member of the New York City General Assembly (NYCGA), the group that brought you Occupy Wall Street, Justin continues his education activism with the Grassroots Education Movement, Class Size Matters, and now serves as the Co-Principal of the Paul Robeson Freedom School.

Yesterday was tax day, when millions of Americans fulfilled that annual patriotic ritual that funds roads, schools, libraries, hospitals, and all those pesky social services that regular people rely upon each day to make our country liveable.

Millions of Americans, yes, but not ALL Americans.

Some choose to help fund roads, schools, libraries, hospitals in other places instead. Like the Cayman Islands.

Don’t get me wrong – I love Caymanians. Beautifully hospitable people they are, and they enjoy arguably the most progressive taxes in the world: zero income tax and only the rich pay when they come to work – read “cook the books” – on their island for a few days a year. School is free, health care guaranteed to all who work. It’s a beautiful place to live, wholly subsidized by the 99% in developed countries like yours and mine.

When they stash their money abroad and don’t pay taxes while doing business on our land, using our workforce and electrical grids and roads and getting our tax incentives to (not) create jobs, WE pay.

We small businesses.

We students.

We nurses.

We taxpayers.

I went down to the Caymans myself to figure out just how easy it is to open an offshore tax haven and start helping Caymanians – and myself – rather than Americans.

Here’s what happened:

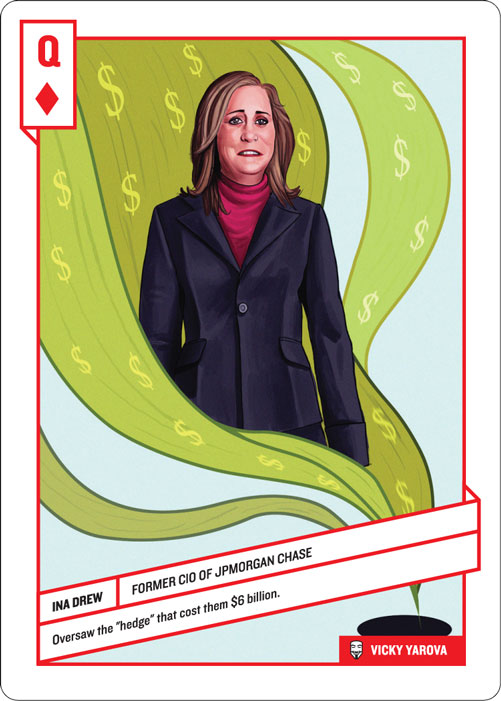

Ina Drew: heinously greedy or heinously incompetent?

Last night I went to an event at Barnard where Ina Drew, ex-CIO head of JP Morgan Chase, who oversaw the London Whale fiasco, was warmly hosted and interviewed by Barnard president Debora Spar.

[Aside: I was going to link to Ina Drew’s wikipedia entry in the above paragraph, but it was so sanitized that I couldn’t get myself to do it. She must have paid off lots of wiki editors to keep herself this clean. WTF, wikipedia??]

A little background in case you don’t know who this Drew woman is. She was in charge of balance-sheet risk management and somehow managed to not notice losing $6.2 billion dollars in the group she was in charge of, which was meant to hedge risk, at least according to CEO Jamie Dimon. She made $15 million per year for her efforts and recently retired.

In her recent Congressional testimony (see Example 3 in this recent post), she threw the quants with their Ph.D.’s under the bus even though the Senate report of the incident noted multiple risk limits being exceeded and ignored, and then risk models themselves changed to look better, as well as the “whale” trader Bruno Iksil‘s desire to get out of his losing position being resisted by upper management (i.e. Ina Drew).

I’m not going to defend Iksil for that long, but let’s be clear: he fucked up, and then was kept in his ridiculous position by Ina Drew because she didn’t want to look bad. His angst is well-documented in the Senate report, which you should read.

Actually, the whole story is somewhat more complicated but still totally stupid: instead of backing out of certain credit positions the old-fashioned and somewhat expensive way, the CIO office decided to try to reduce its capital requirements via reducing (manipulated) VaR, but ended up increasing their capital requirements in other, non-VaR ways (specifically, the “comprehensive risk measure”, which isn’t as manipulable as VaR). Read more here.

Maybe Ina is going to claim innocence, that she had no idea what was going on. In that case, she had no control over her group and its huge losses. So either she’s heinously greedy or heinously incompetent. My money’s on “incompetent” after seeing and listening to her last night. My live Twitter feed from the event is available here.

We featured Ina Drew on our “52 Shades of Greed” card deck as the Queen of diamonds:

Back to the event.

Why did we cart out Ina Drew in front of an audience of young Barnard women last night? Were we advertising a career in finance to them? Is Drew a role model for these young people?

The best answers I can come up with are terrible:

- She’s a Barnard mom (her daughter was in the audience). Not a trivial consideration, especially considering the potential donor angle.

- President Spar is on the board of Goldman Sachs and there’s a certain loyalty among elites, which includes publicly celebrating colossal failures. Possible, but why now? Is there some kind of perverted female solidarity among women that should be in jail but insist on considering themselves role models? Please count me out of that flavor of feminism.

- President Spar and Ina Drew actually don’t think Drew did anything wrong. This last theory is the weirdest but is the best supported by the tone of the conversation last night. It gives me the creeps. In any case I can no longer imagine supporting Barnard’s mission with that woman as president. It’s sad considering my fond feelings for the place where I was an assistant professor for two years in the math department and which treated me well.

Please suggest other ideas I’ve failed to mention.

We don’t need more complicated models, we need to stop lying with our models

The financial crisis has given rise to a series of catastrophes related to mathematical modeling.

Time after time you hear people speaking in baffled terms about mathematical models that somehow didn’t warn us in time, that were too complicated to understand, and so on. If you have somehow missed such public displays of throwing the model (and quants) under the bus, stay tuned below for examples.

A common response to these problems is to call for those models to be revamped, to add features that will cover previously unforeseen issues, and generally speaking, to make them more complex.

For a person like myself, who gets paid to “fix the model,” it’s tempting to do just that, to assume the role of the hero who is going to set everything right with a few brilliant ideas and some excellent training data.

Unfortunately, reality is staring me in the face, and it’s telling me that we don’t need more complicated models.

If I go to the trouble of fixing up a model, say by adding counterparty risk considerations, then I’m implicitly assuming the problem with the existing models is that they’re being used honestly but aren’t mathematically up to the task.

But this is far from the case – most of the really enormous failures of models are explained by people lying. Before I give three examples of “big models failing because someone is lying” phenomenon, let me add one more important thing.

Namely, if we replace okay models with more complicated models, as many people are suggesting we do, without first addressing the lying problem, it will only allow people to lie even more. This is because the complexity of a model itself is an obstacle to understanding its results, and more complex models allow more manipulation.

Example 1: Municipal Debt Models

Many municipalities are in shit tons of problems with their muni debt. This is in part because of the big banks taking advantage of them, but it’s also in part because they often lie with models.

Specifically, they know what their obligations for pensions and school systems will be in the next few years, and in order to pay for all that, they use a model which estimates how well their savings will pay off in the market, or however they’ve invested their money. But they use vastly over-exaggerated numbers in these models, because that way they can minimize the amount of money to put into the pool each year. The result is that pension pools are being systematically and vastly under-funded.

Example 2: Wealth Management

I used to work at Riskmetrics, where I saw first-hand how people lie with risk models. But that’s not the only thing I worked on. I also helped out building an analytical wealth management product. This software was sold to banks, and was used by professional “wealth managers” to help people (usually rich people, but not mega-rich people) plan for retirement.

We had a bunch of bells and whistles in the software to impress the clients – Monte Carlo simulations, fancy optimization tools, and more. But in the end, the banks and their wealth managers put in their own market assumptions when they used it. Specifically, they put in the forecast market growth for stocks, bonds, alternative investing, etc., as well as the assumed volatility of those categories and indeed the entire covariance matrix representing how correlated the market constituents are to each other.

The result is this: no matter how honest I would try to be with my modeling, I had no way of preventing the model from being misused and misleading to the clients. And it was indeed misused: wealth managers put in absolutely ridiculous assumptions of fantastic returns with vanishingly small risk.

Example 3: JP Morgan’s Whale Trade

I saved the best for last. JP Morgan’s actions around their $6.2 billion trading loss, the so-called “Whale Loss” was investigated recently by a Senate Subcommittee. This is an excerpt (page 14) from the resulting report, which is well worth reading in full:

While the bank claimed that the whale trade losses were due, in part, to a failure to have the right risk limits in place, the Subcommittee investigation showed that the five risk limits already in effect were all breached for sustained periods of time during the first quarter of 2012. Bank managers knew about the breaches, but allowed them to continue, lifted the limits, or altered the risk measures after being told that the risk results were “too conservative,” not “sensible,” or “garbage.” Previously undisclosed evidence also showed that CIO personnel deliberately tried to lower the CIO’s risk results and, as a result, lower its capital requirements, not by reducing its risky assets, but by manipulating the mathematical models used to calculate its VaR, CRM, and RWA results. Equally disturbing is evidence that the OCC was regularly informed of the risk limit breaches and was notified in advance of the CIO VaR model change projected to drop the CIO’s VaR results by 44%, yet raised no concerns at the time.

I don’t think there could be a better argument explaining why new risk limits and better VaR models won’t help JPM or any other large bank. The manipulation of existing models is what’s really going on.

Just to be clear on the models and modelers as scapegoats, even in the face of the above report, please take a look at minute 1:35:00 of the C-SPAN coverage of former CIO head Ina Drew’s testimony when she’s being grilled by Senator Carl Levin (hat tip Alan Lawhon, who also wrote about this issue here).

Ina Drew firmly shoves the quants under the bus, pretending to be surprised by the failures of the models even though, considering she’d been at JP Morgan for 30 years, she might know just a thing or two about how VaR can be manipulated. Why hasn’t Sarbanes-Oxley been used to put that woman in jail? She’s not even at JP Morgan anymore.

Stick around for a few minutes in the testimony after Levin’s done with Drew, because he’s on a roll and it’s awesome to watch.

WTF is happening in Cyprus?

One thing I kept track of while I was away was the ongoing, intensely interesting situation in Cyprus. For those of you who have been following it just as closely, this will not be new, and please correct me if you think I’ve gotten something wrong.

Background

Cyprus banks have recently gotten deeply in trouble, partly because of their heavy investment in Greek government bonds which as you remember were semi-defaulted on in spite of them being “risk-weighted” at zero, and partly because of an enormous amount of Russian money they hold (Russian businessmen enjoy lowering their taxes by funneling their money to Cyprus), which created a severely bloated financial sector.

To be fair, just having deposits of rich Russian businessmen doesn’t make you fragile. But it’s just not done in banking, I guess, to simply hold on to money – you have to invest it somewhere, and they invested poorly.

To get an idea of how bloated the finance sector is and how badly the banks were hurting, if the Cyprus government was to give them the money they need, it would be 70% of GDP, and they’re already about 90% of GDP in debt. Even so, that’s only 17.2 billion Euros, or a bit more than twice Steven Cohen’s personal fortune ($10 billion) even after his firm, SAC Capital Advisors, settled with the SEC for insider trading “without admitting nor denying wrongdoing”.

What are the options?

- Do we ask the government of Cyprus to prop up the failing banks? Then it (the government) would be underwater and people would stop investing in its bonds and we’d need a bailout of the government. In other words, we’d just be handing the hot potato to the people.

- Does the EU or IMF loan money to government to give to the banks?

- Or to banks directly? Either way this would feel wrong to the northern European taxpayers, who would be essentially bailing out a bunch of Russian businessmen. Europeans are suffering from bailout fatigue, and German elections are coming up, making this even stronger.

- Or do we make the banks deal with their solvency issues themselves? After all, their shareholders, bond holders, and depositors all represent money they have which they can theoretically keep.

- Or some combination? Actually, all plans below are combo plans, whereby the banks make themselves solvent and then, after that, the EU/IMF team kicks in a few billion euros. Whether it will be enough money after the ricochet effects of the plan is not at all clear.

Plan #1: anti-FDIC insurance.

The plan as of more than a week ago was to take money from all the accounts as well as bond holders and shareholders. This included even the so-called insured deposits of accounts below 100,000 Euros.

So normal people, who thought their money was insured, would be paying 6.7% of their savings into a so-called “bail-in” fund, and people with more money in their accounts would be paying 9.9%.

This was across-the-board, by the way, for all Cyprus banks, independent of how much trouble a given bank was in. The banks closed down before this was announced so people couldn’t grab their money.

Compare that to the US version of a bailout from 2008, when shareholders got partially screwed, bondholders were left whole, deposits were untouched, but taxpayers were on the hook (and still are).

Plan #1 was baldfaced: it was saying to the average person in Cyprus, “Hey we fucked up the banks, can we take your money to fix it?”. It was incredible that anyone thought it would work. The ramifications of such an anti-FDIC insurance would be immediate and contagious, namely everyone in any related country would immediately start pulling their money out of banks. Why keep your money in an institution where you’re surely losing 7% when you can hide your money in a suitcase with only a small chance of it getting stolen?

Reaction by public: Hell No

Needless to say, the people in Cyprus didn’t like the plan. In fact, they strongly objected to directly paying for the mistakes of rich bankers and to protect Russians. They protested loudly and the Cypriotic politicians heard them, and voted down plan #1.

Plan #2

Since plan #1 failed, how about we just take money from uninsured depositors? Oh, and also make it bank-specific. So the banks that are in bigger poo-poo would seize more of their deposits than the banks that were in less poo-poo. That makes sense, and seems to be the current plan.

Problems with the current plan

There are a few problems with the new plan. But mostly they are what I’d call transition costs versus long-term problems. Easy for me to say, since I don’t live in Cyprus.

Rich people moving their money

First, rich people everywhere will no longer park lots of money in uninsured accounts in weak banks. Rich people have lots of options, though, so don’t feel too bad for them. They will instead put their money into lots of little accounts in lots of places, each of which will be insured. If this means they distribute their money over more banks, this is good for the banking system because it diversifies the capital and we’d end up with lots of biggish banks instead of a few enormous banks.

I’m not sure what the technical rules are, though. Say I’m stinking rich. Can I open 15 Bank of America accounts, each with $250K and so FDIC-insured? If I can’t do that for my local Bank of America branch, can I use Bank of America subsidiaries? Are the rules the same in the US and Europe? These rules are all of a sudden more important.

This is a transition cost, and within a few months all of the rich people will have their accounts insured or hidden.

Job losses

Second, there will be severe job losses in the bloated finance sector in Cyprus. Right now there are protests by workers from Laiki Bank, which is the worst off Cyprus bank, because they’re poised to lose their jobs. Again, it’s easy for me to say since I don’t live in Cyprus, but that’s what happens when you have an industry that’s too big – at some point it gets smaller and people lose jobs. I was around when the same thing happened to fisherman off the coast of New England, and it wasn’t pretty.

Again, though, it’s transitional. At some point the number of people working in banks in Cyprus will be reasonable. The question is whether they will have found another industry to replace finance.

Capital controls

The banks re-opened today, and of course people are standing in line to get cash, but things generally seem calm.

The big problem for businesses in Cyprus is that various “temporary” capital controls (which just means limits on taking money out of the country and on taking money from your bank) have been put into place that may lead to long-term problems.

Update (hat tip commenter badmax): many Russians already took their money out before the capital controls were imposed.

Euros don’t flow into and out of Cyprus effortlessly anymore, so the so-called monetary union has been broken. Depending on how quickly those rules are removed, and how quickly Cyprus comes up with other things to do, this could be a huge problem for the country.

Take-aways

- What’s become blatantly clear by following this process is that there is no actual process. Things are being made up as they go along by a bunch of economists and finance ministers. A lot of faith in their abilities was lost permanently when they hatched plan #1 which was so obviously stupid.

- Going back to that stupid plan, whereby normal depositors were supposed to pay for the mistakes of banks at the expense of their insured deposits. It was so bald-faced that the citizens rebelled, and politicians listened. So just to be clear, there has been actual input by average people in this process. The economists and finance ministers have lost face and the people have found a voice.

- This is not to say that the Cyprus people are sitting pretty. They are not, and by some estimates the economy of Cyprus is poised to contract by 20%. This may lead to more bailouts or Cyprus leaving the Eurozone for good.

Guest Post SuperReview Part III of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I and a little Part II: Where We Are Now

Whattup.

Moving on from Lewis’ cute Bloomberg column reprint, we come to the next essay in the series:

The Widening Gyre: Inequality, Polarization, and the Crisis by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells

Indefatigable pair Paul Krugman and Robin Wells (KW hereafter) contribute one of the several original essays in the book, but the content ought to be familiar if you read the New York Times, know something about economics or practice finance. Paul Krugman is prolific, and it isn’t hard to be prolific when you have to rewrite essentially the same column every week; question, are there other columnists who have been so consistently right yet have failed to propose anything that the polity would adopt? Political failure notwithstanding, Krugman leaves gems in every paragraph for the reader new to all this. The title “The Widening Gyre” comes from an apocalyptic William Yeats Butler poem. In this case, Krugman and Wells tackle the problem of why the government responded so poorly to the crisis. In their words:

By 2007, America was about as unequal as it had been on the eve of the Great Depression – and sure enough, just after hitting this milestone, we lunged into the worst slump since the Depression. This probably wasn’t a coincidence, although economists are still working on trying to understand the linkages between inequality and vulnerability to economic crisis.

Here, however, we want to focus on a different question: why has the response to crisis been so inadequate? Before financial crisis struck, we think it’s fair to say that most economists imagined that even if such a crisis were to happen, there would be a quick and effective policy response [editor’s note: see Kautsky et al 2016 for a partial explanation]. In 2003 Robert Lucas, the Nobel laureate and then president of the American Economic Association, urged the profession to turn its attention away from recessions to issues of longer-term growth. Why? Because he declared, the “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Famous last words from Professor Lucas. Nevertheless, the curious failure to apply what was once the conventional wisdom on a useful scale intrigues me for two reasons. First, most political scientists suggest that democracy, versus authoritarian system X, leads to better outcomes for two reasons.

1. Distributional – you get a nicer distribution of wealth (possibly more productivity for complicated macro reasons); economics suggests that since people are mostly envious and poor people have rapidly increasing utility in wealth, democracy’s tendency to share the wealth better maximizes some stupid social welfare criterion (typically, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency).

2. Information – democracy is a better information aggregation system than dictatorship and an expanded polity makes better decisions beyond allocation of produced resources. The polity must be capable of learning and intelligent OR vote randomly if uninformed for this to work. While this is the original rigorous justification for democracy (first formalized in the 1800s by French rationalists), almost no one who studies these issues today believes one-person one-vote democracy better aggregates information than all other systems at a national level. “Well Leon,” some knave comments, “we don’t live in a democracy, we live in a Republic with a president…so shouldn’t a small group of representatives better be able to make social-welfare maximizing decisions?” Short answer: strong no, and US Constitutionalism has some particularly nasty features when it comes to political decision-making.

Second, KW suggest that the presence of extreme wealth inequalities act like a democracy disabling virus at the national level. According to KW extreme wealth inequalities perpetuate themselves in a way that undermines both “nice” features of a democracy when it comes to making regulatory and budget decisions.* Thus, to get better economic decision-making from our elected officials, a good intermediate step would be to make our tax system more progressive or expand Medicare or Social Security or…Well, we have a lot of good options here. Of course, for mathematically minded thinkers, this begs the following question: if we could enact so-called progressive economic policies to cure our political crisis, why haven’t we done so already? What can/must change for us to do so in the future? While I believe that the answer to this question is provided by another essay in the book, let’s take a closer look at KW’s explanation at how wealth inequality throws sand into the gears of our polity. They propose four and the following number scheme is mine:

1. The most likely explanation of the relationship between inequality and polarization is that the increased income and wealth of a small minority has, in effect bought the allegiance of a major political party…Needless to say, this is not an environment conducive to political action.

2. It seems likely that this persistence [of financial deregulation] despite repeated disasters had a lot do with rising inequality, with the causation running in both directions. On the one side the explosive growth of the financial sector was a major source of soaring incomes at the very top of the income distribution. On the other side, the fact that the very rich were the prime beneficiaries of deregulation meant that as this group gained power- simply because of its rising wealth- the push for deregulation intensified. These impacts of inequality on ideology did not in 2008…[they] left us incapacitated in the face of crisis.

3. Conservatives have always seen seen [Keynesian economics] as the thin edge of the wedge: concede that the government can play a useful role in fighting slumps, and the next thing you know we’ll be living under socialism.

4. [Krugman paraphrasing Kalecki] Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment to a great extend on the so-called state of confidence….This gives capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.

All of these are true to an extent. Two are related to the features of a particular policy position that conservatives don’t like (countercyclical spending) and their cost will dissipate if the economy improves. Isn’t it the case that most proponents and beneficiaries of financial liberalization are Democrats? (Wall Street mostly supported Obama in 08 and barely supported Romney in 12 despite Romney giving the house away). In any case, while KW aren’t big on solutions they certainly have a strong grasp of the problem.

Take a Stand: Sit In by Phillip Dray

As the railroad strike of 1877 had led eventually to expanded workers’ rights, so the Greensboro sit-in of February 1, 1960, helped pave the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both movements remind us that not all successful protests are explicit in their message and purpose; they rely instead on the participants’ intuitive sense of justice. [28]

I’m not the only author to have taken note of this passage as particularly important, but I am the only author who found the passage significant and did not start ranting about so-called “natural law.” Chronicling the (hitherto unknown-to-me) history of the Great Upheaval, Dray does a great job relating some important moments in left protest history to the OWS history. This is actually an extremely important essay and I haven’t given it the time it deserves. If you read three essays in this book, include this in your list.

Inequality and Intemperate Policy by Raghuram Rajan (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

Rajan’s basic ideas are the following: inequality has gotten out of control:

Deepening income inequality has been brought to the forefront of discussion in the United States. The discussion tends to center on the Croesus-like income of John Paulson, the hedge fund manager who made a killing in 2008 betting on a financial collapse and netted over $3 billion, about seventy-five-thousand times the average household income. Yet a more worrying, everyday phenomenon that confronts most Americans is the disparity in income growth rates between a manager at the local supermarket and the factory worker or office assistant. Since the 1970s, the wages of the former, typically workers at the ninetieth percentile of the wage distribution in the United States, have grown much faster than the wages of the latter, the typical median worker.

But American political ideologies typically rule out the most direct responses to inequality (i.e. redistribution). The result is a series of stop-gap measures that do long-run damage to the economy (as defined by sustainable and rising income levels and full employment), but temporarily boost the consumption level of lower classes:

It is not surprising then, that a policy response to rising inequality in the United States in the 1990s and 200s – whether carefully planned or chosen as the path of least resistance – was to encourage lending to households, especially but not exclusively low-income ones, with the government push given to housing credit just the most egregious example. The benefit – higher consumption – was immediate, whereas paying the inevitable bill could be postponed into the future. Indeed, consumption inequality did not grow nearly as much as income inequality before the crisis. The difference was bridged by debt. Cynical as it may seem, easy credit has been used as a palliative success administrations that been unable to address the deeper anxieties of the middle class directly. As I argue in my book Fault Lines, “Let them eat credit” could well summarize the mantra of the political establishment in the go-go years before the crisis.

Why should you believe Raghuram Rajan? Because he’s one of the few guys who called the first crisis and tried to warn the Fed.

A solid essay providing a more direct link between income inequality and bad policy than KW do.

The 5 Percent by Michael Hiltzik

The 5 percent’s [consisting of the seven million Americans who, in 1934, were sixty-five and older] protests coalesced as the Townsend movement, launched by a sinewy midwestern farmer’s son and farm laborer turned California physician. Francis Townsend was a World War I veteran who had served in the Army Medical Corps. He had an ambitious, and impractical plan for a federal pension program. Although during its heyday in the 1930s the movement failed to win enactment of its [editor’s note: insane] program, it did play a critical role in contemporary politics. Before Townsend, America understood the destitution of its older generations only in abstract terms; Townsend’s movement made it tangible. “It is no small achievment to have opened the eyes of even a few million Americans to these facts,” Bruce Bliven, editor of the New Republic observed. “If the Townsend Plan were to die tomorrow and be completely forgotten as miniature golf, mah-jongg, or flinch [editor’s note: everything old is new again], it would still have left some sedimented flood marks on the national consciousness.” Indeed, the Townsend movement became the catalyst for the New Deal’s signal achievement, the old-age program of Social Security. The history of its rise offers a lesson for the Occupy movement in how to convert grassroots enthusiasm into a potent political force – and a warning about the limitations of even a nationwide movement.

Does the author live up to the promises of this paragraph? Is the whole essay worth reading? Does FDR give in to the people’s demands and pass Social Security?!

Yes to all. Read it.

Hidden in Plain Sight by Gillian Tett (no URL, you’ll have to buy the book)

This is a great essay. I’m going to outsource the review and analysis to:

http://beyoubesure.com/2012/10/13/generation-lost-lazy-afraid/

because it basically sums up my thoughts. You all, go read it.

What Good is Wall Street? by John Cassidy

If you know nothing about Wall Street, then the essay is worth reading, otherwise skip it. There are two common ways to write a bad article in financial journalism. First, you can try to explain tiny index price movements via news articles from that day/week/month. “Shares in the S&P moved up on good news in Taiwan today,” that kind of nonsense. While the news and price movements might be worth knowing for their own sake, these articles are usually worthless because no journalist really knows who traded and why (theorists might point out even if the journalists did know who traded to generate the movement and why, it’s not clear these articles would add value – theorists are correct).

The other way, the Cassidy! way is to ask some subgroup of American finance what they think about other subgroups in finance. High frequency traders think iBankers are dumb and overpaid, but HFT on the other hand, provides an extremely valuable service – keeping ETFs cheap, providing liquidity and keeping shares the right level. iBankers think prop-traders add no value, but that without iBanking M&A services, American manufacturing/farmers/whatever would cease functioning. Low speed prop-traders think that HFT just extracts cash from dumb money, but prop-traders are reddest blooded American capitalists, taking the right risks and bringing knowledge into the markets. Insurance hates hedge funds, hedge funds hate the bulge bracket, the bulge bracket hates the ratings agencies, who hate insurance and on and on.

You can spit out dozens of articles about these catty and tedious rivalries (invariably claiming that financial sector X, rivals for institutional cash with Y, “adds no value”) and learn nothing about finance. Cassidy writes the article taking the iBankers side and surprises no one (this was originally published as an article in The New Yorker).

Your House as an ATM by Bethany McLean

Ms. McLean holds immense talent. It was always pretty obvious that the bottom twenty-percent, i.e. the vast majority of subprime loan recipients, who are generally poor at planning, were using mortgages to get quick cash rather than buy houses. Regulators and high finance, after resisting for a good twenty years, gave in for reasons explained in Rajan’s essay.

Against Political Capture by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (sorry I couldn’t find a URL, for this original essay you’ll have to buy the book).

A legit essay by a future Nobelist in Econ. Read it.

A Nation of Business Junkies by Arjun Appadurai

Anthro-hack Appadurai writes:

I first came to this country in 1967. I have been either a crypto-anthropologist or professional anthropologist for most of the intervening years. Still, because I came here with an interest in India and took the path of least resistance in choosing to retain India as my principal ethnographic referent, I have always been reluctant to offer opinions about life in these United States.

His instincts were correct. The essay reads like an old man complaining about how bad the weather is these days. Skip it.

Causes of Financial Crises Past and Present: The Role of This-Time-Is-Different Syndrome by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff

Editor Byrne has amazing powers of persuasion or, a lot of authors have had some essays in the desk-drawer they were waiting for an opportunity to publish. In any case, Rogoff and Reinhart (RR hereafter) have summed up a couple hundred studies and two of their books in a single executive summary and given it to whoever buys The Occupy Handbook. Value. RR are Republicans and the essay appears to be written in good faith (unlike some people *cough* Tyler Cowen and Veronique de Rugy *cough*). RR do a great job discovering and presenting stylized facts about financial crises past and present. What to expect next? A couple national defaults and maybe a hyperinflation or two.

Government As Tough Love by Robert Shiller as interviewed by Brandon Adams (buy the book)!

Shiller has always been ahead of the curve. In 1981, he wrote a cornerstone paper in behavioral finance at a time when the field was in its embryonic stages. In the early 1990s, he noticed insufficient attention was paid to real estate values, despite their overwhelming importance to personal wealth levels; this led him to create, along with Karl E. Case, the Case-Shiller index – now the Case-Shiller Home Prices Indices. In March 2000**, Shiller published Irrational Exuberance, arguing that U.S. stocks were substantially overvalued and due for a tumble. [Editor’s note: what Brandon Adams fails to mention, but what’s surely relevant is that Shiller also called the subprime bubble and re-released Irrational Exuberance in 2005 to sound the alarms a full three years before The Subprime Solution]. In 2008, he published The Subprime Solution, which detailed the origins of the housing crisis and suggested innovative policy responses for dealing with the fallout. These days, one of his primary interests is neuroeconomics, a field that relates economic decision-making to brain function as measured by fMRIs.

Shiller is basically a champ and you should listen to him.

Shiller was disappointed but not surprised when governments bailed out banks in extreme fashion while leaving the contracts between banks and homeowners unchanged. He said, of Hank Paulson, “As Treasury secretary, he presented himself in a very sober and collected way…he did some bailouts that benefited Goldman Sachs, among others. And I can imagine that they were well-meaning, but I don’t know that they were totally well-meaning, because the sense of self-interest is hard to clean out of your mind.”

Shiller understates everything.

Verdict: Read it.

And so, we close our discussion of part I. Moving on to part II:

In Ms. Byrne’s own words:

Part 2, “Where We Are Now,” which covers the present, both in the United States and abroad, opens with a piece by the anthropologist David Graeber. The world of Madison Avenue is far from the beliefs of Graeber, an anarchist, but it’s Graeber who arguably (he says he didn’t do it alone) came up with the phrase “We Are the 99 percent.” As Bloomberg Businessweek pointed out in October 2011, during month two of the Occupy encampments that Graeber helped initiate and three moths after the publication of his Debt: The First 5,000 Years, “David Graeber likes to say that he had three goals for the year: promote his book, learn to drive, and launch a worldwide revolution. The first is going well, the second has proven challenging and the third is looking up.” Graeber’s counterpart in Chile can loosely be said to be Camila Vallejo, the college undergraduate, pictured on page 219, who, at twenty-three, brought the country to a standstill. The novelist and playwright Ariel Dorfman writes about her and about his own self-imposed exile from Chile, and his piece is followed by an entirely different, more quantitative treatment of the subject. This part of the book also covers the indignados in Spain, who before Occupy began, “occupied” the public squares of Madrid and other cities – using, as the basis for their claim on the parks could be legally be slept in, a thirteenth-century right granted to shepherds who moved, and still move, their flocks annually.

In other words, we’re in occupy is the hero we deserve, but not the hero we need territory here.

*Addendum 1: Some have suggested that it’s not the wealth inequality that ought to be reduced, but the democratic elements of our system. California’s terrible decision–making resulting from its experiments with direct democracy notwithstanding, I would like to stay in the realm of the sane.

**Addendum 2: Yes, Shiller managed to get the book published the week before the crash. Talk about market timing.

Guest Post SuperReview Part II of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I: How We Got Here

Whatsup.

This is a review of Part I of The Occupy Handbook. Part I consists of twelve pieces ranging in quality from excellent to awful. But enough from me, in Janet Byrne’s own words:

Part 1, “How We Got Here,” takes a look at events that may be considered precursors of OWS: the stories of a brakeman in 1877 who went up against the railroads; of the four men from an all-black college in North Carolina who staged the first lunch counter sit-in of the 1960s; of the out-of-work doctor whose nationwide, bizarrely personal Townsend Club movement led to the passage of Social Security. We go back to the 1930s and the New Deal and, in Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff‘s “nutshell” version of their book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, even further.

Ms. Byrne did a bang-up job getting one Nobel Prize Winner in economics (Paul Krugman), two future Economics Nobel Prize winners (Robert Shiller, Daron Acemoglu) and two maybes (sorry Raghuram Rajan and Kenneth Rogoff) to contribute excellent essays to this section alone. Powerhouse financial journalists Gillian Tett, Michael Hilztik, John Cassidy, Bethany McLean and the prolific Michael Lewis all drop important and poignant pieces into this section. Arrogant yet angry anthropologist Arjun Appadurai writes one of the worst essays I’ve ever had the misfortune of reading and the ubiquitous Brandon Adams make his first of many mediocre appearances interviewing Robert Shiller. Clocking in at 135 pages, this is the shortest section of the book yet varies the most in quality. You can skip Professor Appadurai and Cassidy’s essays, but the rest are worth reading.

Advice from the 1 Percent: Lever Up, Drop Out by Michael Lewis

Framed as a strategy memo circulated among one-percenters, Lewis’ satirical piece written after the clearing of Zucotti Park begins with a bang.

The rabble has been driven from the public parks. Our adversaries, now defined by the freaks and criminals among them, have demonstrated only that they have no idea what they are doing. They have failed to identify a single achievable goal.

Indeed, the absurd fixation on holding Zuccotti Park and refusal to issue demands because doing so “would validate the system” crippled Occupy Wall Street (OWS). So far OWS has had a single, but massive success: it shifted the conversation back to the United States’ out of control wealth inequality managed to do so in time for the election, sealing the deal on Romney. In this manner, OWS functioned as a holding action by the 99% in the interests of the 99%.

We have identified two looming threats: the first is the shifting relationship between ambitious young people and money. There’s a reason the Lower 99 currently lack leadership: anyone with the ability to organize large numbers of unsuccessful people has been diverted into Wall Street jobs, mainly in the analyst programs at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Those jobs no longer exist, at least not in the quantities sufficient to distract an entire generation from examining the meaning of their lives. Our Wall Street friends, wounded and weakened, can no longer pick up the tab for sucking the idealism out of America’s youth.We on the committee are resigned to all elite universities becoming breeding grounds for insurrection, with the possible exception of Princeton.

Michael Lewis speaks from experience; he is a Princeton alum and a 1 percenter himself. More than that however, he is also a Wall Street alum from Salomon Brothers during the 1980s snafu and wrote about it in the original guide to Wall Street, Liar’s Poker. Perhaps because of his atypicality (and dash of solipsism), he does not have a strong handle on human(s) nature(s). By the time of his next column in Bloomberg, protests had broken out at Princeton.

Ultimately ineffectual, but still better than…

Lewis was right in the end, but more than anyone sympathetic to the movement might like. OccupyPrinceton now consists of only two bloggers, one of which has graduated and deleted all his work from an already quiet site and another who is a senior this year. OccupyHarvard contains a single poorly written essay on the front page. Although OccupyNewHaven outlasted the original Occupation, Occupy Yale no longer exists. Occupy Dartmouth hasn’t been active for over a year, although it has a rather pathetic Twitter feed here. Occupy Cornell, Brown, Caltech, MIT and Columbia don’t exist, but some have active facebook pages. Occupy Michigan State, Rutgers and NYU appear to have had active branches as recently as eight months ago, but have gone silent since. Functionally, Occupy Berkeley and its equivalents at UCBerkeley predate the Occupy movement and continue but Occupy Stanford hasn’t been active for over a year. Anecdotally, I recall my friends expressing some skepticism that any cells of the Occupy movement still existed.

As for Lewis’ other points, I’m extremely skeptical about “examined lives” being undermined by Wall Street. As someone who started in math and slowly worked his way into finance, I can safely say that I’ve been excited by many of the computing, economic, and theoretical problems quants face in their day-to-day work and I’m typical. I, and everyone who has lived long-enough, knows a handful of geniuses who have thought long and hard about the kinds of lives they want to lead and realized that A. there is no point to life unless you make one and B. making money is as good a point as any. I know one individual, after working as a professional chemist prior to college,who decided to in his words, “fuck it and be an iBanker.” He’s an associate at DB. At elite schools, my friend’s decision is the rule rather than the exception, roughly half of Harvard will take jobs in finance and consulting (for finance) this year. Another friend, an exception, quit a promising career in operations research to travel the world as a pick-up artist. Could one really say that either the operations researcher or the chemist failed to examine their lives or that with further examinations they would have come up with something more “meaningful”?

One of the social hacks to give lie to Lewis-style idealism-emerging-from-an attempt-to-examine-ones-life is to ask freshpeople at Ivy League schools what they’d like to do when they graduate and observe their choices four years later. The optimal solution for a sociopath just admitted to a top school might be to claim they’d like to do something in the peace corp, science or volunteering for the social status. Then go on to work in academia, finance, law or tech or marriage and household formation with someone who works in the former. This path is functionally similar to what many “average” elite college students will do, sociopathic or not. Lewis appears to be sincere in his misunderstanding of human(s) nature(s). In another book he reveals that he was surprised at the reaction to Liar’s Poker – most students who had read the book “treated it as a how-to manual” and cynically asked him for tips on how to land analyst jobs in the bulge bracket. It’s true that there might be some things money can’t buy, but an immensely pleasurable, meaningful life do not seem to be one of them. Today for the vast majority of humans in the Western world, expectations of sufficient levels of cold hard cash are necessary conditions for happiness.

In short and contra Lewis, little has changed. As of this moment, Occupy has proven so harmless to existing institutions that during her opening address Princeton University’s president Shirley Tilghman called on the freshmen in the class of 2016 to “Occupy” Princeton. No freshpeople have taken up her injunction. (Most?) parts of Occupy’s failure to make a lasting impact on college campuses appear to be structural; Occupy might not have succeeded even with better strategy. As the Ivy League became more and more meritocratic and better at discovering talent, many of the brilliant minds that would have fallen into the 99% and become its most effective advocates have been extracted and reached their so-called career potential, typically defined by income or status level. More meritocratic systems undermine instability by making the most talented individuals part of the class-to-be-overthrown, rather than the over throwers of that system. In an even somewhat meritocratic system, minor injustices can be tolerated: Asians and poor rural whites are classes where there is obvious evidence of discrimination relative to “merit and the decision to apply” in elite gatekeeper college admissions (and thus, life outcomes generally) and neither group expresses revolutionary sentiment on a system-threatening scale, even as the latter group’s life expectancy has begun to decline from its already low levels. In the contemporary United States it appears that even as people’s expectations of material security evaporate, the mere possibility of wealth bolsters and helps to secure inequities in existing institutions.

Lewis continues:

Hence our committee’s conclusion: we must be able to quit American society altogether, and they must know it.The modern Greeks offer the example in the world today that is, the committee has determined, best in class. Ordinary Greeks seldom harass their rich, for the simple reason that they have no idea where to find them. To a member of the Greek Lower 99 a Greek Upper One is as good as invisible.

He pays no taxes, lives no place and bears no relationship to his fellow citizens. As the public expects nothing of him, he always meets, and sometimes even exceeds, their expectations. As a result, the chief concern of the ordinary Greek about the rich Greek is that he will cease to pay the occasional visit.

Michael Lewis is a wise man.

I can recall a conversation with one of my Professors; an expert on Democratic Kampuchea (American: Khmer Rouge), she explained that for a long time the identity of the oligarchy ruling the country was kept secret from its citizens. She identified this obvious subversion of republican principles (how can you have control over your future when you don’t even know who runs your region?) as a weakness of the regime. Au contraire, I suggested, once you realize your masters are not gods, but merely humans with human characteristics, that they: eat, sleep, think, dream, have sex, recreate, poop and die – all their mystique, their claims to superior knowledge divine or earthly are instantly undermined. De facto segregation has made upper classes in the nation more secure by allowing them to hide their day-to-day opulence from people who have lost their homes, job and medical care because of that opulence. Neuroscience will eventually reveal that being mysterious makes you appear more sexy, socially dominant, and powerful, thus making your claims to power and dominance more secure (Kautsky et. al. 2018).*

If the majority of Americans manage to recognize that our two tiered legal system has created a class whose actual claim to the US immense wealth stems from, for the most part, a toxic combination of Congressional pork, regulatory and enforcement agency capture and inheritance rather than merit, there will be hell to pay. Meanwhile, resentment continues to grow. Even on the extreme right one can now regularly read things like:

Now, I think I’d be downright happy to vote for the first politician to run on a policy of sending killer drones after every single banker who has received a post-2007 bonus from a bank that received bailout money. And I’m a freaking libertarian; imagine how those who support bombing Iraqi children because they hate us for our freedoms are going to react once they finally begin to grasp how badly they’ve been screwed over by the bankers. The irony is that a banker-assassination policy would be entirely constitutional according to the current administration; it is very easy to prove that the bankers are much more serious enemies of the state than al Qaeda. They’ve certainly done considerably more damage.

Wise financiers know when it’s time to cash in their chips and disappear. Rarely, they can even pull it off with class.

The rest of part I reviewed tomorrow. Hang in there people.

Addendum 1: If your comment amounts to something like “the Nobel Prize in Economics is actually called the The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel” and thus “not a real Nobel Prize” you are correct, yet I will still delete your comment and ban your IP.

*Addendum 2: More on this will come when we talk about the Saez-Delong discussion in part III.

Guest Post SuperReview Part I of VI: The Occupy Handbook

Whassup.

It has become a truism that as the amount of news and information generated per moment continues to grow, so too does the value of aggregation, curation and editing. A point less commonly made is that these aggregators are often limited by time in the sense, whatever the topic, the value of news for the median reader decays extremely rapidly. Some extremists even claim that it’s useless to read the newspaper, so rapidly do things change. The forty eight hours news cycle, in addition to destroying context, has made it impossible for both reporters and viewers to learn from history. See “Is News Memoryless?” (Kautsky et. al. 2014).

A more promising approach to news aggregation (for those who read the news with purpose) is to organize pieces by subject and publish those articles in a book. Paul Krugman did this for himself in The Great Unraveling, bundling selected columns from 1999 to 2003 into a single book, with chapters organized by subject and proceeding chronologically. While the rise and rise of Krumgan’s real-time blogging virtually guarantees he’ll never make such an effort again, a more recent try came from uber-journalist Michael Lewis in Panic!: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity. Financial journalists’ myopic perspective at any given point in time make financial column compilations of years past particularly fun(ny) to read.

Nothing is staler than yesterday’s Wall Street journal (financial news spoils quickly) and reading WSJ or Barron’s pieces from 10 to 20 years ago is just painful.

The title PANIC: The story of modern financial insanity led me to believe the book was about the current crises. The book does say, in very, very fine print “Edited by” Michael Lewis.

-Fritz Krieger, Amazon Reviewer and chief scientist at ISIS

Unfortunately, some philistines became angry in 2008 when they insta-purchased a book called Panic! by Michael Lewis and to their horror, discovered that it contained information about prior financial crises, the nerve of the author to bring us historical perspective, even worse…some of that perspective relating to nations other than the ole’ US of A.

As the more alert readers have noted, almost nothing in the book concerns the 2008 Credit Meltdown, but instead this is merely a collection of news clippings and old magazine articles about past financial crises. You might as well visit a chiropodist’s office and offer them a couple of bucks for their old magazines.

Granted, the articles are by some of today’s finest and most celebrated journalists (although some of the news clippings are unsigned), but do you really want to read more about the 1987 crash or the 1997 collapse of the Thai Baht?

Perhaps you do, but whoever threw this book together wasn’t very particular about the articles chosen. Page 193 reprints an article from “Barron’s” of March, 2000 in which Jack Willoughby presents a long list of Internet companies that he considered likely to run out of cash by 2001. “Some can raise more funds through stock and bond offerings,” he warns. “Others will be forced to go out of business. It’s Darwinian capitalism at work.” True, many of the companies he listed did go belly-up, but on his list of the doomed are

[..]Amazon.com– Someone named Keith Otis Edwards

Perhaps because I was abroad for both the initial disaster and the entire Occupation of Zucotti Park, both events have held my attention. So it is with a mixture of hope and apprehension that I picked up Princeton alum Janet Byrne’s The Occupy Handbook from the public library. The Occupy Handbook is a collection of essays written from 2010 to 2011 by an assortment of first and second-rate authors that attempt to: show what Wall Street does and what it did that led to the most recent crash, explain why our policy apparatus was paralyzed in response to the crash, describe how OWS arose and how it compared with concurrent international movements and prior social movements in the US, and perhaps most importantly, provide policy solutions for the 99% in finance and economics. Janet Byrne begins with a heartfelt introduction:

One fall morning I stood outside the Princeton Club, on West 43rd Street in Manhattan. Occupy Wall Street, which I had visited several times as a sympathetic outsider, has passed its one month anniversary, and I thought the movement might be usefully analyzed by economists and financial writers whose pieces I would commission and assemble into a book that was analytical and- this was what really interested me – prescriptive. I’d been invited to breakfast to talk about the idea with a Princeton Club member and had arrived early out of nervousness.

It seemed a strange place to be discussing the book. I tried the idea out on a young bellhop…

And so it continues. The book is divided into three parts. Part I, broadly speaking, tries to give some economic background on the crash and the ensuing political instability that the crash engendered, up to the first occupation of Zuccotti Park. Part II, broadly speaking, describes the events in Zuccotti Park and around the world as they were in those critical months of fall 2011. Part III, broadly speaking, prescribes solutions to current depression. I say broadly speaking because, as you will see, several essays appear to be in the wrong part and in the worst cases, in the wrong book.

Black Scholes and the normal distribution

There have been lots of comments and confusion, especially in this post, over what people in finance do or do not assume about how the markets work. I wanted to dispel some myths (at the risk of creating more).

First, there’s a big difference between quantitative trading and quantitative risk. And there may be a bunch of other categories that also exist, but I’ve only worked in those two arenas.

Markets are not efficient

In quantitative trading, nobody really thinks that “markets are efficient.” That’s kind of ridiculous, since then what would be the point of trying to make money through trading? We essentially make money because they aren’t. But of course that’s not to say they are entirely inefficient. Some approaches to removing inefficiency, and some markets, are easier than others. There can be entire markets that are so old and well-combed-over that the inefficiencies (that people have thought of) have been more or less removed and so, to make money, you have to be more thoughtful. A better way to say this is that the inefficiencies that are left are smaller than the transaction costs that would be required to remove them.

It’s not clear where “removing inefficiency” ends and where a different kind of trading begins, by the way. In some sense all algorithmic trades that work for any amount of time can be thought of as removing inefficiency, but then it becomes a useless concept.

Also, you can see from the above that traders have a vested interest to introduce new kinds of markets to the system, because new markets have new inefficiencies that can be picked off.

This kind of trading is very specific to a certain kind of time horizon as well. Traders and their algorithms typically want to make money in the average year. If there’s an inefficiency with a time horizon of 30 years it may still exist but few people are patient enough for it (I should add that we also probably don’t have good enough evidence that they’d work, considering how quickly the markets change). Indeed the average quant shop is going in the opposite direction, of high speed trading, for that very reason, to find the time horizon at which there are still obvious inefficiencies.

Black-Scholes

A long long time ago, before Black Monday in 1987, people didn’t know how to price options. Then Black-Scholes came out and traders started using the Black-Scholes (BS) formula and it worked pretty well, until Black Monday came along and people suddenly realized the assumptions in BS were ridiculous. Ever since then people have adjusted the BS formula. Everyone.

There are lots of ways to think about how to adjust the formula, but a very common one is through the volatility smile. This allows us to remove the BS assumption of constant volatility (of the underlying stock) and replace it with whatever inferred volatility is actually traded on in the market for that strike price and that maturity. As this commenter mentioned, the BS formula is still used here as a convenient reference to do this calculation. If you extend your consideration to any maturity and any strike price (for the same underlying stock or thingy) then you get a volatility surface by the same reasoning.

Two things to mention. First, you can think of the volatility smile/ surface as adjusting the assumption of constant volatility, but you can also ascribe to it an adjustment of the assumption of a normal distribution of the underlying stock. There’s really no way to extricate those two assumptions, but you can convince yourself of this by a thought experiment: if the volatility stays fixed but the presumed shape of the distribution of the stocks gets fatter-tailed, for example, then option prices (for options that are far from the current price) will change, which will in turn change the implied volatility according to the market (i.e. the smile will deepen). In other words, the smile adjusts for more than one assumption.

The other thing to mention: although we’ve done a relatively good job adjusting to market reality when pricing an option, when we apply our current risk measures like Value-at-Risk (VaR) to options, we still assume a normal distribution of risk factors (one of the risk factors, if we were pricing options, would be the implied volatility). So in other words, we might have a pretty good view of current prices, but it’s not at all clear we know how to make reasonable scenarios of future pricing shifts.

Ultimately, this assumption of normal distributions of risk factors in calculating VaR is actually pretty important in terms of our view of systemic risks. We do it out of computational convenience, by the way. That and because when we use fatter-tailed assumptions, people don’t like the answer.

Modeling fraud in the financial system

Today we have a guest post by Dan Tedder. Actually it’s a letter he sent me after listening to my EconTalk podcast with Russ Roberts which he kindly agreed to let me post. Dan’s bio is below the letter.

I think this letter is profound (although I don’t completely agree about the Markov stuff), because it points out something that I see as a commonly held blindspot by people who think about regulation and modeling. Namely, that any systemic risk model of the financial system that doesn’t take account of lying isn’t worth the memory it takes up on a computer.

That brings us to the following question: can we incorporate lies into models? Can we anticipate and model fraud itself, in addition to the underlying system? Or do we give up on models and rely on skeptical people to ferret out lies? Or possibly some hybrid?

——

Hi Cathy,

I really liked your interview, and I think you are right on in pointing to a lack of ethics. I would say further that what we need is rigorous honesty in all aspects of the financial system. I agree with your objections to conflicts of interest. Allowing such conflicts to exist demonstrates a lack of rigorous honesty on the part of the participants. In my opinion a lot of bankers and folks on Wall Street should be headed to jail. The inability of the SEC to file charges and prosecute them further demonstrates the lack of honesty and character in the financial system and the government. So why am I telling you things you already know?

My father was a successful businessman. Years ago I was invited to invest in an ice cream franchise by another faculty member. I spent several days developing models using Excel. Finally, I decided to talk to my father. I called him and he immediately asked me to tell him about the present owners and their accounting. I told him the husband was in jail and accounting was five years behind. Further, his wife was probably taking money out of the till.

He stopped me right there, and pointed out that I needed to look no further. The present owners were not honest and therefore the opportunity was too risky. No telling what liabilities they had incurred and passed on to the franchise. I felt like an idiot. My modeling was a total waste of time because it assumed the present owners were honest. In fact, they were dishonest and no defensible model could be constructed based upon their accounting or lack thereof.

I think the complexity of our present financial problems will largely disappear if we try to focus more on the obvious. First, it is obvious that bankers, accountants, modelers, and other participants must be rigorously honest. Second, George Box, a statistician at the University of Wisconsin, studied the stock market and found through time series analysis that stock market prices are Markov processes. So in modeling stock prices we need only worry about today and tomorrow. The best indicator of tomorrow’s price is today’s price. The best indicator of what will happen tomorrow is where we are today, and probably our models of the larger process should also be Markovian. Third, apply the KISS method, “Keep it simple, stupid.” Instead of worrying about the mathematical model, worry about the honesty of the participants. The financial system cannot tolerate dishonesty. Making sure the bankers are honest will go a long way toward balancing the books.

Regards, Dan

——

Daniel William Tedder is Associate Professor Emeritus, School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Adjunct Professor, School of Mechanical Engineering, both at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He attended Kenyon College and received a Bachelor’s in Chemical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He obtained MS and PhD degrees in Chemical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He was a staff engineer in the Chemical Technology Division of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory before joining the faculty at Georgia Tech. He served as an independent technical reviewer at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission after retiring from Georgia Tech. He has numerous publications, has edited 11 books, and has authored one book, Preliminary Chemical Process Design and Economics, which is available from Amazon. He is an expert in chemical separations and in actinide partitioning, an advanced method for radioactive waste management.

Prices in the junk bond market

There are various ways of deciding how valuable something is. People spend some amount of time talking about “the current value of future earnings til the end of time” as a rule-of-thumb measurement. That sometimes works (i.e. jives with what the selling price is), but it’s certainly not robust – in a given case, plenty of people think there’s a good reason a stock should be worth more than that, if their personal growth projections are rosy (you could argue that they are still valuing future earnings, but they’ve got a different projection than, say, the current dividends continued as is. Another possibility is that they’re simply valuing future values coming from other people). Similarly, some stocks are underpriced with respect to this baseline. Could it be that they’re cooking their books? If they don’t last til the end of time then they could hardly be making earnings til then (Groupon).

Of course when you go down that road, nothing lasts til the end of time. Never mind companies, the industry in which the company sits will be dead before too long unless it’s food or cosmetics.

Anyway, throw out the future earnings price for a moment, and replace it by something else entirely: there’s a certain amount of money invested in the (international) market at a given moment, and it has to go somewhere. I think of it as a big pot that sloshes around and achieves equilibrium depending on various things like relative interest rates in different countries, and to a lesser extent, regulation in different countries and access to markets. Like, the carry trade is kind of a big deal, and depends almost entirely on the Japanese interest rate being tiny.

Of course it’s not really that simple, since people can and do remove money from the market at certain times – it’s not a closed system. But not as much money is removed as you might think, because if you think about it, lots of people have set up their livelihoods to be investing large pots of money, so they need to appear busy.

Articles like this one from Bloomberg make me think about the “where should we put our money that we need to invest somewhere?” effect is particularly strong right now. We see people “chasing yield” in the junk bond market, buying junk bonds that have positive yields because their options are limited while the Fed keeps the rates really low (this is not a side-effect of the Fed’s keeping the rates low, it’s their goal. They want people to invest in financing businesses, which is what buying junk bonds is).

But they (the investors) all want the same stuff, so the prices are too low high, which is another way of saying the yields are a lot lower than they’d otherwise be if there were other things to buy. This might be a good example of where the price of junk debt is not particularly good at exposing the actual risk of default. Well, it might be an ok indicator of the very short-term default rate, but that’s just because money is so cheap right now, businesses in trouble can just borrow more. It’s kind of a set-up for a bubble.