Archive

Bayesian regressions (part 2)

In my first post about Bayesian regressions, I mentioned that you can enforce a prior about the size of the coefficients by fiddling with the diagonal elements of the prior covariance matrix. I want to go back to that since it’s a key point.

Recall the covariance matrix represents the covariance of the coefficients, so those diagonal elements correspond to the variance of the coefficients themselves, which is a natural proxy for their size.

For example, you may just want to make sure the coefficients don’t get too big, or in other words there’s a penalty for large coefficients. Actually there’s a name for just having this prior, and it’s called L2 regularization. You just set the prior to be , where

is the identity matrix, and

is a tuning parameter- you can set the strength of the prior by turning

“up to eleven“.

You’re going to end up adding this prior to the actual sample covariance matrix as measured by the data, so don’t worry about the prior matrix being invertible (but definitely do make sure it’s symmetrical).

Moreover, you can have many different priors, corresponding to different parts of the covariance matrix, and you can add them all up together to get a final prior.

From my first post, I had two priors, both on the coefficients of lagged values of some time series. First, I expect the signal to die out logarithmically or something as we go back in time, so I expect the size of the coefficients to die down as a power of some parameter. In other words, I’ll actually have two parameters: one for the decrease on each lag and one overall tuning parameter. My prior matrix will be diagonal and the th entry will be of the form

for some

and for a tuning parameter

My second prior was that the entries should vary smoothly, which I claimed was enforceable by fiddling with the super and sub diagonals of the covariance matrix. This is because those entries describe the covariance between adjacent coefficients (and all of my coefficients in this simple example correspond to lagged values of some time series).

In other words, ignoring the variances of each variable (since we already have a handle on the variance from our first prior), we are setting a prior on the correlation between adjacent terms. We expect the correlation to be pretty high (and we can estimate it with historical data). I’ll work out exactly what that second prior is in a later post, but in the end we have two priors, both with tuning parameters, which we may be able to combine into one tuning parameter, which again determines the strength of the overall prior after adding the two up.

Because we are tamping down the size of the coefficients, as well as linking them through a high correlation assumption, the net effect is that we are decreasing the number of effective coefficients, and the regression has less work to do. Of course this all depends on how strong the prior is too; we could make the prior so weak that it has no effect, or we could make it so strong that the data doesn’t effect the result at all!

In my next post I will talk about combining priors with exponential downweighting.

Koo: don’t be surprised by the crappy economy

First I wanted to thank you for the wonderful comments I’ve been enjoying and compiling from my last post about what’s corrupt about the financial system and what should be done about it. Even if I don’t end up doing the teach-in (hopefully I will! In any case I’ll go down there, even if it’s just to try to set up the teach-in for a later date) I think this is a really fantastic and important discussion. I’m putting together a final list of issues tonight and I think I’ll make a flyer to bring tomorrow, so if I don’t actually conduct the teach-in (yet) I’ll at least be able to give the info booth the flyers.

And it’s not too late! Please keep the comments coming.

Today I want to start a discussion on Richard Koo’s book, which is about Japan’s so-called “lost decade” (a reader suggested this book to me, and it’s fascinating, so thanks! And please feel free to make more suggestions for my reading list).

You can actually get a pretty good overview of his book by watching this excellent interview by Koo. For those of you, like me, whose sound doesn’t work on their computers, here’s his basic thesis:

- After the housing bubble in Japan burst, a bunch of firms, banks and otherwise, became technically insolvent. This meant that, although they had cash flow, they owed more than their assets.

- Because they were insolvent, they didn’t maximize profits like in normal times; instead they minimized debts.

- In other words, they didn’t borrow money to grow their businesses, like you’d expect in normal circumstances, which is proved by looking at data showing that corporate borrowing went down even as interest rates lowered to zero.

- The CEO’s didn’t talk about this because they don’t want anyone to know they’re insolvent!

- Investors are also somewhat blind to this, because they typically look at growth and cash flow issues.

- Japan’s government made massive investments in order to cover the lack of private investments.

- Rather than this being a mistake, this was absolutely essential to the Japanese economy and prevented a massive depression.

- Moreover, the idea that Japan had a lost decade is false: actually, there was a lot going on in that decade (actually, 15 years) but people didn’t see it. Namely, the balance sheets were slowly improved over the entire economy.

- This is a lesson for us all: any time there’s a massive credit bubble which breaks, we can expect a balance sheet recession where behavior like this is the rule. The U.S. economy right now is an example of this.

I have a few comments about this. I wanted to mention that I’m only about halfway through the book so it’s possible that Koo addresses some of these issues but on the other hand the book was published in 2009 but was clearly written before the U.S. credit crisis was really full-blown:

- A friend of mine who recently traveled to Japan noted that the people there live extremely well. In fact, if he hadn’t been told that their country has been in recession for nearly twenty years then he’d have never guessed it. This supports Koo’s claim that the Japanese government absolutely did the right thing by bankrolling the economy when it did. It also brings up a very basic question: how do we measure success? And why do we listen to economists when they tell us how to define success?

- Not every country can do what Japan did in terms of investing in its economy, although the U.S. probably can. In other words, it depends on how other countries see your credit risk whether you can go ahead and bail out an entire economy.

- Some of the businesses in the U.S. are clearly not technically insolvent; we’ve already seen ample evidence of cash hoarding. On the other hand, I guess if sufficiently many are, then the overall environment can be affected like Koo describes.

- In general it makes me wonder, how many of the firms out there today are technically insolvent? How insolvent? How long will it take for those that are to either fail outright or pay back their loans? If we go by this article, then the answer is pretty alarming, at least for the banks.

In general I like Koo’s book in that it introduces a new paradigm which explains something as totally self-evident that had been mysterious. It’s pretty bad news for us, though, for two reasons. First, it means we could be in this (by which I mean stagnant growth) for a long, long time, and second, considering the hyperbolic political situation, it’s not clear that the government will end up responding appropriately, which means we may be in it for even longer.

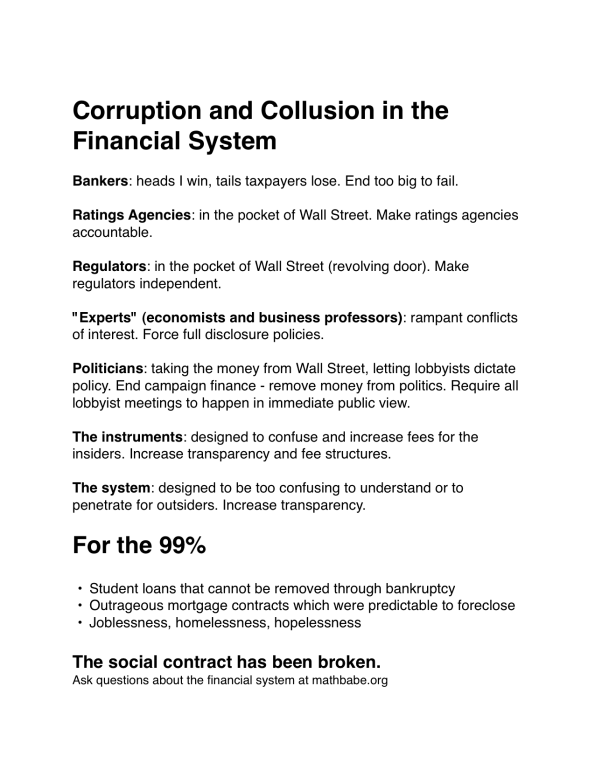

What’s wrong with Wall Street and what should be done about it?

I am trying to figure out the top five (or so) most important corrupt and actionable issues related to the financial system. I’m going to compile this list in order to conduct a “teach-in” at the Occupy Wall Street protest next week. The tentative date is Wednesday, October 12, at 5:30pm.

I’d love to hear your thoughts: please tell me if I’m missing something or got something wrong or left something out.

The list I have so far:

- Investment bankers trading their books and taking outrageous risks which lead to government-backed bailouts because they are “too big to fail”. The related action in the U.S. might be the “Volcker rule” (i.e. reinstating something like Glass-Steagall); unfortunately it’s being watered down as you read this.

- Ratings agencies in collusion with their clients. The actions here would be changing the pay structure of the ratings agencies and opening up the methods, as well as having better regulatory oversight. We also need to change the structure of ratings agencies, and either make it easier to form an agency or make the agencies that already exist and have government protection actually accountable for their “opinions”.

- SEC and other regulators in collusion with the industry. The action here would be to nurture and maintain an adversarial relationship between regulators and bankers. We’ve seen too many people skip from the SEC to the banks they were regulating and then back. There should be rules against this (how about a minimum time requirement of 5 years between jobs on the opposite sides?). There should also be much better funding for the SEC and the other regulators, so they can actually meet their expanded mandate.

- Conflict of interest issues from economists and business school professors. If you’ve seen “Inside Job” then you’ll know all about how professors at various universities use their credentials to back up questionable practices. Moreover, they are often not even required to expose their industry connections when they do expert witnessing or write “academic” papers. The action here would be, at the very least, to force full disclosure for all such appearances and all publications. I’ve heard some good news in this direction but there obviously should be a standard.

- Rampant buying of politicians and influence of lobbyists from the financial industry. This is maybe more of a political problem than a financial one so I’m willing to chuck this off the list. Please tell me if you have something else in mind. Someone has suggested the opaque and elevated pension fund management system. Although I consider that pretty corrupt, I’m not sure it’s as important as other issues to the average person. I’m on the fence.

Saturday afternoon quickie

Two things.

- If I see another fucking article about how the world is going to miss Steve Jobs I’m going to puke. He made and sold overpriced gadgets for fucks sake! It’s hero worship plain and simple, maybe even a sick cult.

- I am happy that I’ve been invited to give a “teach-in” at Occupy Wall Street next Wednesday at 5:30 (tentative date and time). I’ve promised an overview of the 5 top corrupt things in the financial system. I’d really appreciate your thoughts: what is your top 5 list? I want them to be both important and relatively actionable. So far I’ve got:

- Volcker rule (i.e. reinstating something like Glass-Steagall); it’s being watered down as you read this.

- Ratings agencies in collusion with their clients

- SEC and other regulators in collusion with the industry

- Rampant buying of politicians and influence of lobbyists from the financial industry

- Incredibly poor incentives for the individuals in the industry, both in terms of salary and whistleblowing

Bayesian regressions (part 1)

I’ve decided to talk about how to set up a linear regression with Bayesian priors because it’s super effective and not as hard as it sounds. Since I’m not a trained statistician, and certainly not a trained Bayesian, I’ll be coming at it from a completely unorthodox point of view. For a more typical “correct” way to look at it see for example this book (which has its own webpage).

The goal of today’s post is to abstractly discuss “bayesian priors” and illustrate their use with an example. In later posts, though, I promise to actually write and share python code illustrating bayesian regression.

The way I plan to be unorthodox is that I’m completely ignoring distributional discussions. My perspective is, I have some time series (the ‘s) and I want to predict some other time series (the

) with them, and let’s see if using a regression will help me- if it doesn’t then I’ll look for some other tool. But what I don’t want to do is spend all day deciding whether things are in fact student-t distributed or normal or something else. I’d like to just think of this as a machine that will be judged on its outputs. Feel free to comment if this is palpably the wrong approach or dangerous in any way.

A “bayesian prior” can be thought of as equivalent to data you’ve already seen before starting on your dataset. Since we think of the signals (the ‘s) and response (

) as already known, we are looking for the most likely coefficients

that would explain it all. So the form a bayesian prior takes is: some information on what those

‘s look like.

The information you need to know about the ‘s is two-fold. First you need to know their values and second you need to have a covariance matrix to describe their statistical relationship to each other. When I was working as a quant, we almost always had strong convictions about the latter but not the former, although in the literature I’ve been reading lately I see more examples where the values (really the mean values) for the

‘s are chosen but with an “uninformative covariance assumption”.

Let me illustrate with an example. Suppose you are working on the simplest possible model: you are taking a single time series and seeing how earlier values of predict the next value of

. So in a given update of your regression,

and each

is of the form

for some

What is your prior for this? Turns out you already have one (two actually) if you work in finance. Namely, you expect the signal of the most recent data to be stronger than whatever signal is coming from older data (after you decide how many past signals to use by first looking at a lagged correlation plot). This is just a way of saying that the sizes of the coefficients should go down as you go further back in time. You can make a prior for that by working on the diagonal of the covariance matrix.

Moreover, you expect the signals to vary continuously- you (probably) don’t expect the third-from recent variable to have a positive signal but the second-from recent variable

to have a negative signal (especially if your lagged autocorrelation plot looks like this). This prior is expressed as a dampening of the (symmetrical) covariance matrix along the subdiagonal and superdiagonal.

In my next post I’ll talk about how to combine exponential down-weighting of old data, which is sacrosanct in finance, with bayesian priors. Turns out it’s pretty interesting and you do it differently depending on circumstances. By the way, I haven’t found any references for this particular topic so please comment if you know of any.

Occupy Wall Street: Day 13

So I went to see the Occupy Wall Street protests this morning before work and this evening after work again. Here are some of my comments and observations.

First, if you are interested in checking it out, know that there are small marches at opening and closing bell for the market.

However, the police have made it basically impossible to walk on Wall Street, due to some incredibly annoying barricades.

So for our march this morning we seemed to just circle the city block where the protest is based, although I didn’t stay til the end so it’s possible they decided to very very slowly march on Wall Street proper.

So for our march this morning we seemed to just circle the city block where the protest is based, although I didn’t stay til the end so it’s possible they decided to very very slowly march on Wall Street proper.

Second, they have “assemblies” twice a day, with guest speakers sometimes (Michael Moore, Susan Sarandon and Cornel West have visited), and this is where general announcements are made. The crowd was quite large tonight and it was difficult to hear what the speaker and the repeaters were saying, which is frustrating. But maybe it’s easier at the 1pm assembly. Also, it seems to be easier to actually discuss issues in the morning- at night it gets loud and kind of crazy and hard to focus in my opinion.

Next, I’d like to address the issue of the message of the protesters being dismissed as incoherent. For the record, I went to a conference at the end of 2009 at Columbia Business School on the financial crisis and what we should do about it, where the speakers were fancy economists from central banks and CEOs of international banks, and they were about as incoherent as these protesters. There was absolutely no getting them to say anything that was an actual plan or even an attempt at a plan for changing the system so this mess wouldn’t happen again. I should know, because there was a question and answer period and I asked.

Having said that, there have been some pretty unconvincing statements reported from some of the protesters in terms of what they would like to see. For example, some of them seem to think that short selling should be banned. As some of you know, I disagree. In fact there are lots of seriously corrupt and ridiculous things going on in the financial system which they should know about and they should protest, and I’d like to invite them to educate themselves.

In particular, if you are someone interested in knowing stuff about how the financial system works, then please ask! A major part of why I blog is to try to inform people about these things who are interested. Please comment below and ask whatever you want, and if I don’t know the answer I will find someone who does, or I will blog about the question.

Having said that, I’d like to add that it’s on the one hand perfectly reasonable that people don’t understand the financial system, because it has essentially been set up to be too complicated to understand, and on the other hand it’s also reasonable to think of the entire financial system as a black box which can be judged by its outputs.

Finally, if we are going to judge the system by looking at its outputs, then these protesters, who are in general young, with educations, huge students debts, and hopeless outlooks, have a pretty dismal view. In other words they have every right to complain that the system is fucking them, even though they don’t know how the system works. I for one am super proud that they’re out there doing something, even if it’s not obviously organized and polished, rather than passively sitting by.

Occupy Wall Street—Report

This is a guest post by FogOfWar.

I was originally going to lead with a tongue-in-cheek comment (later in the post now), but then the NYPD did something colossally stupid. If you haven’t seen it, here’s the video from this last weekend. It pretty much speaks for itself.

There’s a lot to be said about freedom of expression and police overreaction. I’ve been to see the protests a number of times, and they’ve never been violent and in fact seem pretty well trained in the confines of freedom of assembly in the US legal system. Using mace against an imminent threat of violence is OK for the police, but the video seems to show no threatening moves made at all (and it runs for a good period before the police attack so it wasn’t edited out).

I’d suggest the NYPD be shown the following video (taken from the protests in Greece) to demonstrate when things reach a level where force might be an appropriate response. Note that the crowd is attacking with sticks, Molotov cocktails and a fucking bowling ball. In contrast, the NYPD appears to be pepper spraying people for just holding signs and walking down the street. What the fuck?

There are maybe a few hundred people consistently protesting at “Occupy Wall Street” for about 10 days now. It’s got a definite crunchy vibe to the center. Drumming and Mohawks are mandatory:

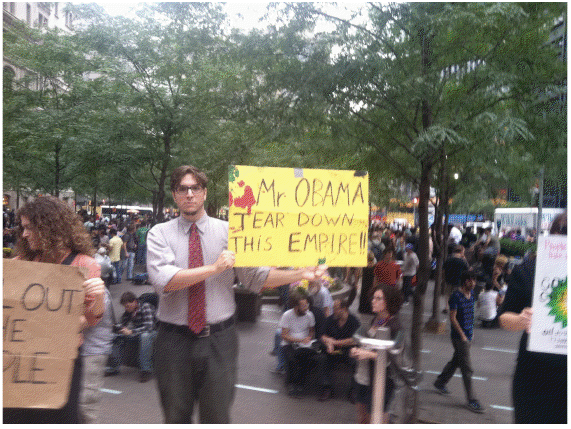

But also a (growing?) contingent of more mainstream participants like this one:

Here’s a crowd shot for scale:

And some people painting signs:

And then of course, there’s the dreaded “consensus circle”:

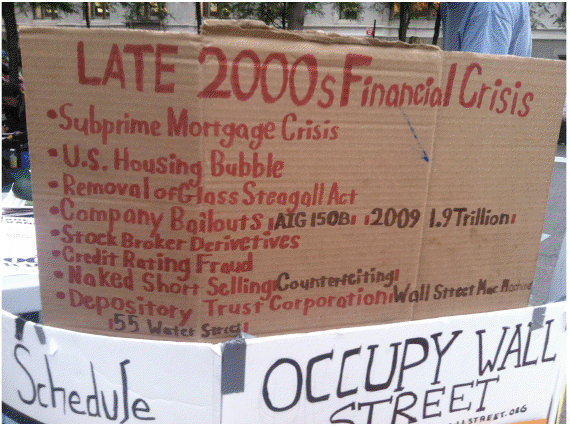

It’s hard to tell what they really want to happen—this was up at one of the information booths (but then down the next time I went):

Misspelled “derivatives”, and there are some things on that list that are spot on and then others that are just weird and irrelevant (DTC? Really?). I don’t think you can hold that against them though. I work in the industry, and I’ve been spending the last three years thinking about this stuff and I still find it confusing and hard to come up with a cohesive plan of what I think should be done. At least these people are doing something, even if it’s a bit incoherent at times.

I have to end with my all time favorite sign from the protest. Someone was looking for good cardboard and inadvertently came up with the following:

“Delicious pizza to pay off the taxpayers”. Now that’s a slogan I think we can all rally behind!

-FoW

The flat screen TV phenomenon

Do you remember, back in 2005 or 2006 or even up to early 2008, how absolutely everyone seemed to be buying flat screen TVs? And not only one, they’d actually buy new ones when new models came out, or ones with different high definition properties. And not just people who could afford it, either. The marketers did an excellent job in somehow convincing people that they needed these flat screen TVs so bad that they should just put it on their credit cards, all 3 thousand dollars of it, or whatever those things cost.

I don’t know exactly how much they cost because I never bought one. The last TV we bought was in 1997 and it still works, for the most part, although it’s really hard to turn it on and off. When it finally kicks the bucket I’m thinking we go without a TV, since TV pretty much sucks anyway. When we do watch it, it’s for live sports (local, or nationally televised, since we don’t pay for cable). Baseball we watch or listen to on the computer.

I was reminded of the the “flat screen TV era” by my friend Ian Langmore the other day when we were discussing household debt amnesty. His argument against debt amnesty for consumers was that they might spend it on crappy things. His example was luxury dog poo, but I’ve been obsessed with the flat screen TV phenomenon ever since a friend of mine, who was $120,000 in debt and didn’t have a salary, somehow managed to buy a flat screen TV in 2007. It blew me away in terms of wasteful consumerism. Ian found this unbelievable blog which kind of sums up my concerns.

In Ian’s opinion, the danger of amnesty, or any system where money is put willy-nilly into the hands of consumers, is twofold:

1) We waste time on unproductive activities. E.g. people spent time buying/building cars that are unneeded.

2) If a miscalculation is made, then the over-leveraged money-go-round stops with a huge mis-balance. E.g. home mortgage crisis.

These are very good points, and put together form a lesson we somehow can’t learn, although perhaps that can be partially explained by this article.

I have two thoughts. First, I’m also uncomfortable putting money in the hands of irresponsible consumers. But the truth is, the way I see it is currently working, we are already putting money in the hands of irresponsible bankers (that’s what the term “injection of liquidity” really means), and they are not doing anything with it, so let’s try something else. In other words, an alternative unpleasant idea.

Second, I don’t think we are going to see a new wave of flat screen TV buying any time soon. If we put money into the hands of consumers right now, I think we’d see them pay down their debts, go to the doctor, and buy jeans for their kids. Of course, there is always someone whose pockets burn with cash, and they would waste money in any situation. Let’s face it, though, credit is tight right now compared to the mid-2000’s. In fact, since economists seem to have a tough time spotting bubbles until afterwards, maybe we can take “a huge part of the population starts buying useless gadgets on credit” as almost a definition, or at least a leading indicator. Then at least there would be some point to all of that wasteful spending.

Do higher taxes kill jobs?

Being a mathematician, I find myself forced to consider statements like “higher taxes kill jobs” as statements of theorems with missing stated assumptions. How could you fill in the assumptions and prove this theorem?

First I think about extreme cases- sometimes extreme situations need fewer assumptions, they kind of spill out as obvious. So here’s one, the tax rate is at 80%, what would happen if we raised taxes? My first reaction is, 80%!? That must mean you have way too much government and regulation and for those reasons businesses are probably already quite pinned down and don’t have lots of freedom- don’t tax them more, that will make their good ideas (if they have them) all the more suffocated. Just think of the paperwork you’d need to go through in a society that government-heavy, to hire someone.

What’s another extreme case? How about taxes are super low, more like fees for doing business. Then no, I don’t think raising them a moderate amount would kill jobs at all, in fact it may introduce enough government to make things less wild west and safer for businesses to operate.

So in other words at some level I buy the anti-regulation anti-government angle. I don’t want super duper high taxes because I think it encourages too much bureaucracy and that stuff is boring (but some amount of it is necessary to make things safe).

Moreover I’m assuming that governments generally use taxes to protect people from food poisoning and the like, regulate to force companies to play fair, and as social safety nets when things go bad, and that they’re not particularly efficient. Those of course are my assumptions, which anyone can disagree with.

But in terms of proving my theorem, I’m stuck thinking it’s more like, there’s some point in between very low and very high taxes where it gradually becomes true that raising taxes more will indeed start to kill jobs.

How about our situation now? Right now we have pretty low taxes by historical measures, and moreover the known loopholes mean that businesses (especially big ones with fancy lawyers) pay much less than their stated tax rate.

Why, in this case, would a moderate bump in their tax rates kill jobs?

Here’s a possible argument: if higher taxes actually encourage more regulation, then that could be a major problem for smaller businesses, who don’t have the margin for dealing with hiring that many lawyers for compliance issues. Although this article argues that “regulation kills jobs” is an invalid statement in general.

Pet peeve of mine: when you hear conservatives talk about killing jobs, they often frame it in terms of struggling small businesses, often run by a woman. But it’s easy enough to imagine that we introduce taxes and regulation that are easier for small businesses to avoid smothering them. It’s really the huge businesses that we want to see start hiring, and it’s the huge businesses that pay so little taxes.

Here’s another one: if you raise taxes people will spend their cash on taxes instead of hiring people. But wait, that doesn’t apply right now when we have so much frigging cash on hand (and hidden in other countries). In other words, companies are not not hiring people for cash flow reasons, it’s because they don’t see the demand.

In the end I can’t see how to prove or even argue that theorem, assuming today’s conditions. Would love to hear the argument I’m missing.

What the hell is going on in Europe?

This week has been particularly confusing when it comes to the European debt crisis. It’s complicated enough to think about the various countries, with their various current debt problems, future debt problems, and austerity plans, not to mention how they typically interact at the political level versus how the average citizen is affected by it all. But this week we’ve seen weird and coordinated intervention by a bunch of central banks to address a so-called “liquidity crisis”.

What is this all about? Is it actually a credit crisis disguised as a liquidity crisis? Is it just another stealth way to bail out huge banks?

I’m going to take a stab at answering these questions, at the risk of talking out of my ass (and when has that ever stopped me?).

Finance is a big messy system, and it’s hard to know where to begin on the merry-go-round of confusion, but let’s start with European banks since they are the ones in need of funding.

European banks have lots of euros on hand, just as American banks have lots of dollars, because of the actual deposits they hold. However, European banks invest in American things (like businesses) that need them to come up with short term funding denominated in dollars. Similarly American banks invest in Europe, but that’s not really relevant to the discussion yet.

How do European banks get these short term (3 month) loans? Historically they do a large majority of it through money-markets: much of the money people have in banks is funneled to huge vats called money markets, and the fund managers of those vats are very very conservatively trying to make a bit of interest on them. In fact they were burned in the credit crisis, when they famously “broke the buck” on Lehman short-term loans.

Well, guess what, those same American money managers are avoiding European short-term loans right now, because they are super afraid of losing money on them. So that source of funding has dried up. Note that this is a credit problem: the money market managers do not trust the banks to be around in 3 months.

Another source of funding for the European banks’ American investments has been just to use their euros, exchange them to dollars (the currency market is very very large and liquid, especially on this particular exchange), then wait until the term of the short-term financing is over, and then convert the dollars back to euros. What actually happens, in fact, is that they borrow euros (at the going rate of 1%), do the exchange, then financing, and then get their money back in the future.

The guys who work at the European banks and who do this short-term financing aren’t allowed to take on the risk that the exchange rate is going to violently change between now and when the short-term term is over. Therefore they need to hedge the risk, which means they have to have a guarantee that the dollars they get out at the end of the term will be turned into a reasonable number of euros.

This kind of guarantee is called a currency swap, and the market for those is also very large and liquid, but has been less liquid recently because of the one-sidedness of this problem: European banks need short-term dollars but American banks don’t need euros at the same rate at the same maturity. So the end result is that the swaps are very very expensive for European banks.

Let’s put this another way, the way that seems strangest and most confusing: right now the European banks can borrow at 1% in euros but at 4% in dollars (for three month maturity), and more generally the demand for USD seems to be skyrocketing recently from all over the place. Does this mean there’s an arbitrage opportunity somewhere? The swaps market is at 3% so no obvious arbitrage. More likely it means that the markets are expecting the exchange rate to drastically change, or at least they are pricing in the risk of it changing violently in the very near future. (The strangest thing to me is why it hasn’t just changed the spot exchange rate as well.)

By the way, a pet peeve or two I have with people talking about arbitrage: firstly, many people use the term so loosely it means nothing at all, as when they take risk over time (exposing themselves to the possibility of an exchange rate change for example). But even here, I’m misusing the term, since in an arbitrage it’s literally supposed to be a way to make money risk-free, but the whole point of my post is that this is really all about counter-party risk! In other words, there’s no arbitrage opportunity to get into contracts with people where you’d make money except if they go bankrupt tomorrow, when there’s a good chance that will happen.

The bottomline is that although the ECB and the Fed and the other central banks have spun this as a coordinated effort to help out a liquidity squeezed but functional market, it doesn’t pass the smell test. What’s actually happening is that the shoddy accounting and investments of French banks and others is not being trusted by American money market managers who are wise to them.

One more thing: the collateral being asked of the European banks is purportedly of low standard, which is to say the ECB is allowing thing like Greek debt as collateral, which wouldn’t past muster with other institutions (or with U.S. money markets!). In that sense this can be seen as a stealth bailout, although I think not the first one in Europe under that definition. This isn’t going away until they figure out how to deal with the Greek debt problem.

Household debt amnesty?

It’s Saturday morning, which means it’s time to conduct a thoroughly absurd thought experiment just for the sake of argument. Today I want to consider the idea of a widespread household debt amnesty: everyone who owes money on their credit cards and payday loans and also perhaps mortgage will be forgiven their debt (although mortgages would have to be rewritten rather than forgiven). What would happen next?

I was discussing this very question, and David Graeber’s book (still not finished- it’s long!) with a friend of mine, specifically how Graeber cites ancient Sumerian civilization as having periodically enacted household debt amnesties to avoid the collapse of their cities (specifically to avoid the debtors from fleeing the cities to avoid their debt problems).

One thing that I realized in that conversation is that, whereas Graeber mentions that it was historically an amnesty for household debt only, so didn’t involve commercial debt between companies and merchants, what we’ve seen in this country in the past 3 years is something like the opposite of that concept. Our (large financial) companies have been granted special considerations while the people who had made the mistake of entering contracts with them have not. And the so-called mortgage modification process has not been sufficiently widespread yet to really consider it an example of this. There is an excellent article here which makes this point, although not in this context.

The objection my friend had to the idea of enacting such an amnesty was that it would be pouring good money after bad; he’s European so he cited the example of Greece, and how the more money Greece gets the more money they spend, so it’s an impossible situation.

Actually I think this is an appealing analogy to make, but it’s a false one. Greece has a large-scale system in place, and giving them money without changing that system clearly isn’t going to solve any long term problems- it just kicks the can down the road.

However, it’s really different with consumer debt (credit cards etc.). Namely, the “system” that a given consumer enters into is a simple relationship (contract) with the credit card company in question. If the debt is forgiven, then the credit card company doesn’t have any obligation to extend more credit to that person. And in many cases, it wouldn’t.

I think the consequences of a household debt amnesty would be something along these lines:

- People who were previously in debt would have some cash on hand and would be able to spend it on consumer stuff (that they can actually afford with no credit) instead of spending it all on minimum payments to old credit card debt

- Credit card companies, burned from their losses, wouldn’t give them new credit cards, or would change the payment arrangements to make sure they got their money back faster

- Since they have no credit, those people who essentially be living in a cash-dominated society. This may actually be a good thing, because it would force people to budget in real time.

- Eventually people could rebuild a credit score over time if they decided to try credit again

In other words, that’s really not so bad and would get money flowing through the system again, which might help with our current recession.

Of course not everyone would be happy about a household debt amnesty. In particular the people who aren’t debtors would feel pretty burned that they’ve been careful (or lucky) with their money and aren’t getting a free ride. And the credit card companies would have to eat a lot of loss. On the other hand they’re going to eat (and have eaten) a lot of loss already, and the slowness of this process is killing the economy.

Is there a way we could set it up to make this work? Even if we ignore the political obstacles?

What are the chances that this will work?

One of the positive things about working at D.E. Shaw was the discipline shown in determining whether a model had a good chance of working before spending a bunch of time on it. I’ve noticed people could sometimes really use this kind of discipline, both in their data mining projects and in their normal lives (either personal lives or with their jobs).

Some of the relevant modeling questions were asked and quantified:

- How much data do you expect to be able to collect? Can you pool across countries? Is there proxy historical data?

- How much signal do you estimate could be in that data? (Do you even know what the signal is you’re looking for?)

- What is the probability that this will fail? (not good) That it will fail quickly? (good)

- How much time will it take to do the initial phase of the modeling? Subsequent phases?

- What is the scope of the model if it works? International? Daily? Monthly?

- How much money can you expect from a model like this if it works? (takes knowing how other models work)

- How much risk would a model like this impose?

- How similar is this model to other models we already have?

- What are the other models that you’re not doing if you do this one, and how do they compare in overall value?

Even if you can’t answer all of these questions, they’re certainly good to ask. Really we should be asking questions like these about lots of projects we take on in our lives, with smallish tweaks:

- What are the resources I need to do this? Am I really collecting all the resources I need? What are the resources that I can substitute for them?

- How good are my resources? Would better quality resources help this work? Do I even have a well-defined goal?

- What is the probability this will fail? That it will fail quickly?

- How long will I need to work on this before deciding whether it is working? (Here I’d say write down a date and stick to it. People tend to give themselves too much extra time doing stuff that doesn’t seem to work)

- What’s the best case scenario?

- How much am I going to learn from this?

- How much am I going to grow from doing this?

- What are the risks of doing this?

- Have I already done this?

- What am I not doing if I do this?

Working with Larry Summers (part 3)

Previously I’ve talked about the quant culture of D.E. Shaw as well as the tendencies of people working there. Today I wanted to add a third part about the experience of being “on the inside looking out” during the credit crisis.

I started my quant job in June 2007, which was perfect timing to never actually experience unbridled profit and success; within two months of starting, there was a major disruption in the market which caused enough momentary panic and uncertainty that the Equities group decided to liquidate their holdings. This was a big deal and meant they lost quite a bit of money on transaction costs as well as losing money because other investors were pulling out of similar trades at the same time.

The August 2007 market disruption was referred to internally as “the kerfuffle”. I’ve grown to think that this slightly dismissive term, which connotates more of an awkward misunderstanding than any real underlying problem, was indicative of a larger phenomenon. Namely, there was a sense that nothing really bad was afoot, that the system couldn’t be at risk, and that as long as we kept our trades on balance market neutral, we would be fine, except for possibly bizarre moments of exception. The tone would be something like, if an upper class man went to a restaurant and his credit card was denied- the waiter would return the credit card with almost an apology, assuming that it must have expired or something, that surely it is a mistake more than an exposure of underlying bankruptcy.

This framing of the world around us, as individual exceptional moments, as mysterious, almost amusing singularities in an otherwise smooth manifold, continued throughout the credit crisis (I left in May 2009), with the exception of the days after Lehman collapsed (Lehman was a 20% owner of D.E. Shaw at the time of its collapse, as well as a one of our major brokers).

But Lehman fell kind of late in the game, actually, for those in the industry. In other words there were months and months of disturbing signs, especially in the overnight lending market (where banks lend to each other for just the night or over the weekend) leading up to the Lehman moment. I remember one experience during those times that still baffles me.

It was a company-wide event, an invitation to see Larry Summers, Robert Rubin, and Alan Greenspan chat with each other and with us at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center. It started with a lavish spread, fit for the dignitaries that were visiting, as well as introductory remarks wherein David Shaw described Larry Summer’s appointment as managing director at D.E. Shaw a “promotion” from being President at Harvard (just to be clear, this was a joke – even David Shaw isn’t that arrogant). In incredibly collegial terms, each of the three spoke for some time and reminisced about working together in the Clinton administration. Whatever, that’s not the important part, although it is kind of strange to think about now.

The important part, in retrospect, was later, near the end, when Alan Greenspan started talking about CMO‘s and how worried he was that anybody investing in them was in for a world of hurt. When I had gotten to D.E. Shaw, one of the first presentations I’d ever gone to was by a guy describing how he thought the same thing, and how we had divested ourselves of any such holdings, at least for the high-risk kind. So when Greenspan asserted these warnings, I sensed quite a bit of smugness in the crowd around me. It made me imagine us investors as a bunch of people playing illegal poker in the back of a club, where the smartest ones in the game get told a few minutes before the cops come and they leave out the back (except in this case it wasn’t actually illegal, and it was retired cops- Greenspan left the Fed at the end of 2006).

I wish I could remember when exactly that Rainbow Room event was, because I specifically remember Rubin saying absolutely nothing and looking uncomfortable when Greenspan was going on about CMOs and the danger in their future. Way later, it was revealed that Rubin, who was being paid obscene amounts by Citigroup at the time, claimed not to know about how toxic those mortgage-backed securities were (nor did he claim to know how much Citibank had invested in them- which begs the question of what he actually did for Citigroup) back when he could do something about it. He was booted in January 2009.

I wanted to mention one other specific thing I remember about this attitude of bemused nonchalance in the face of the world crumbling. When Lehman fell, and the overnight lending market froze for some weeks leading to government intervention, there was a term for this at D.E. Shaw, attributed (perhaps wrongly) to Larry Summers. Namely, the term was “magic liquidity dust”, implying that all we needed, to solve the problems around us and the apparent irrational panic of the markets, was for a fairy to come down to us and shake her wand, spreading this liquidity dust generously in our otherwise functional and robust system.

The saddest part of all of this is that, in a very real sense, these guys were essentially right not to worry. There has been no real restructuring of the system that led to this, just its continuation and backing.

In my next installation I’ll talk about why I think people in finance were, and to some extent still are, so insulated from reality.

Debt

So I’ve been reading David Graeber’s book about debt. He really has quite a few interesting and, I would say, wonderful points in his book, among them:

1) Debt came before money, often in the form of gift giving (you can read about this in his interview with Naked Capitalism)

2) In ancient cultures, and even in more recent cultures before the introduction of money, there were typically two separate spheres of accounting: the first was for daily goods like food and goats, which worked on the credit system, and the second for rearranging human relationships. Here there were things like dowries and symbolic exchanges of gold, meant to acknowledge the changing human relationship, but not as a “price” per se – because it was understood that you couldn’t put a price on a human.

3) Money as we know it is intricately tied in with slavery because it was when a person became a thing that could be sold for profit that we had a sense of price and when these two separate spheres were united. In particular the existence of money also implies the existence of a threat of violence. Moreover, it is this “decontextualizing” of people from their homes, their communities, and families who are forced into slavery that allows us to measure them with a dollar value, and in general it is only through pure decontextualizing that we can have a money system. It is this paradigm, where everyone and everything has no context, that economists rely on to describe the standard game theory of economics.

4) There are three social structures that people come into contact with in their daily lives and in which they give each other things: communistic, reciprocal, and hierarchical. For example, among parents and children, it is communistic; among a CEO and his workers it is often hierarchical, and among two strangers at a market it is reciprocal.

Even though I could (and might) write a post on any of the above points, because I find them each rich with stimulating and challenging concepts (and I haven’t even finished the book yet!), I want to first describe something Graeber mentions about the last one. Also, if someone is reading this that thinks I’ve misrepresented Graeber’s points then please comment.

Namely, Graeber mentions that, although we each have experience, and maybe lots of experience, in the three different social structures, when we tell the story of economics and exchange we invariably talk about reciprocal exchange. So, for example, I have three sons and I spend way more time hanging out with my sons, attending to their needs and making sure their infected toes are treated and helping them find their raincoats, then I spend at any market. In other words, if I were tallying up my contributions to things, my kids would be a far greater drain on my resources than groceries. But our “story” of how we give things and take things is inevitably about buying stocks or negotiating for a house price. In other words, we have been trained (by economists?) or we have trained ourselves to define exchange as a reciprocal, Austrian schoolish, “be selfish and take advantage whenever possible” endeavor, even when in the face of it we can’t claim to be like that.

Since I’m unwaveringly interested in how one tells the story of oneself, this fascinates me. It’s a really excellent example of how we are blind to the most obvious things. It also makes me think that economic theory has a loooong way to go before it can really explain meaningful things about “how things work”. After all, when you allow yourself to include “personal feelings” in your definition of giving and receiving, you realize that the reciprocal exchange part of your life is actually pretty insignificant, and in fact if that’s all that economists can even hope to explain (and it’s not clear they can), then there is more left unexplained than explained.

Moreover, the fact that we don’t see this as a failing (or at least a major hole) in the economic theory, because we are blind to it in ourselves, also immediately points to the possibility that we have overemphasized this aspect, the reciprocal exchange sphere, in our current economic system. In other words, if we had a healthy understanding of how the other two systems work (communistic and hierarchical) we may have developed them in parallel with the reciprocal system, and we may well be better off for it. We may even have an economics system that doesn’t reward rich people and punish poor people, who knows.

By the way, ridiculous and ignorant critique of Graeber’s book here (as in he didn’t read the book) with rebuff in comments by Graeber himself. Thanks to a commenter for that link!

Guest post: The gold standard

FogOfWar kindly wrote a guest post for me while I was on vacation:

First off, for anyone who hasn’t seen the first or second round of “Keynes vs. Hayek” in hip-hop style, please check them out, they’re hilarious.

There’s an economic crisis going on around us, and periodically one hears people suggesting that we go back to the gold standard. It’s a pretty complicated issue, and I don’t really have an answer to the “gold standard debate”–just probing questions and a lingering feeling that the chattering class has been dismissive when they should be seriously inquisitive. I think this dismissiveness is driven by the fact that Ron Paul is the leading political proponent of the gold standard and competing currencies, and he’s (1) a traditional conservative libertarian (a bit in the Goldwater vein); and (2) a bit of a wingnut.

Aristotle would be ashamed— the validity of an argument does not depend upon the person making the argument, but upon whether the ideas contained are valid or invalid. Andrew Sullivan recently linked to this article by Barry Eichengreen, claiming that it’s “a lucid explanation of why calls to go back to the gold standard are so misguided.” In fact, it’s a fairly serious examination of the gold standard (ultimately coming down “nay”), which is a welcome relief from the flippant and arrogant dismissiveness one usually sees from economic pundits.

As with many edited articles, I recommend skipping the first page and a half (begin from the paragraph starting “For this libertarian infatuation with the gold standard…”). Here’s how I think the article should have begun:

[T]he period leading up to the 2008 crisis displayed a number of specific characteristics associated with the Austrian theory of the business cycle. The engine of instability, according to members of the Austrian School, is the procyclical behavior of the banking system. In boom times, exuberant bankers aggressively expand their balance sheets, more so when an accommodating central bank, unrestrained by the disciplines of the gold standard, funds their investments at low cost. Their excessive credit creation encourages reckless consumption and investment, fueling inflation and asset-price bubbles. It distorts the makeup of spending toward interest-rate-sensitive items like housing.

But the longer the asset-price inflation in question is allowed to run, the more likely it becomes that the stock of sound investment projects is depleted and that significant amounts of finance come to be allocated in unsound ways. At some point, inevitably, those unsound investments are revealed as such. Euphoria then gives way to panic. Leveraging gives way to deleveraging. The entire financial edifice comes crashing down.

This schema bears more than a passing to the events of the last two decades.

First, I would reword that last sentence as follows: This schema bear a striking resemblance to the events of the last two decades. Moreover, I would add, in light of this data, one might ask not why fringe candidate Ron Paul is calling for examination of a return to the gold standard, but rather why this view is considered to be on the fringe rather than at the center of debate. There are a number of reasons to believe that a return to the gold standard might not have the desired effect, although that certainly begs the question of what can be done to prevent future crisis on the order of 2008.

I’d place myself in the camp of “not convinced that the gold standard is the answer, but think it would be really hard to fuck up the economy as bad as the Fed did over the last 20 years even if you were trying, so maybe it’s an idea that deserves some real thought.”

Here’s another key paragraph:

Society, in its wisdom, has concluded that inflicting intense pain upon innocent bystanders through a long period of high unemployment [by allowing bubbles to work themselves out as Austrians advocate] is not the best way of discouraging irrational exuberance in financial markets. Nor is precipitating a depression the most expeditious way of cleansing bank and corporate balance sheets. Better is to stabilize the level of economic activity and encourage the strong expansion of the economy. This enables banks and firms to grow out from under their bad debts. In this way, the mistaken investments of the past eventually become inconsequential. While there may indeed be a problem of moral hazard, it is best left for the future, when it can be addressed by imposing more rigorous regulatory restraints on the banking and financial systems.

This gets to the crux of Eichengreen’s argument, but consider the following points:

- The “help” proposed by Keynsians in fact might make things worse in the long term (not out of malice, but the road to hell is paved with good intentions) by dragging out the inevitable consequences of misallocation during the bubble. In essence, this is a ‘rip the band-aid’ off argument. I think I’ve seen some historical analysis that the total damage done from a bank-solvency driven recession is, in fact, worse over time if extended rather than allowing banks to fail and recapitalize (Sweden vs. Japan).

- “… nor is precipitating a depression…” It’s taken as an article of faith that we would have been in a depression if not for the stimulus package, but I’m skeptical. This is and will always be a theoretical “what if” analysis, conducted by economists who have a cognitive bias in favor of a certain answer (and, for those working in government, a President who needs to juke the stats to get reelected).

- “While there may indeed be a problem of moral hazard it is best left for the future, when it can be addressed by imposing more rigorous regulatory restraints on the banking and financial system.” Whaaaaaaaaat? This is where Keynesians lose me. The sentence is so hopelessly naïve that it undermines the entire argument. Take your nose out of your input-driven models for a minute and take a look around and ask yourself how good a track record bank regulators have at imposing “more rigorous regulatory restraints” during boom times; major new regulatory changes only have political will during a crisis (Securities Act of ’33, Exchange Act of ’34, Glass-Steagall in ’34). I’m not going to argue the relative benefits of economic models when the theory is premised on a factual event that’s very likely not going to happen.

Here’s a paragraph I liked:

Bank lending was strongly procyclical in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gold convertibility or not. There were repeated booms and busts, not infrequently culminating in financial crises. Indeed, such crises were especially prevalent in the United States, which was not only on the gold standard but didn’t yet have a central bank to organize bailouts.

The problem, then as now, was the intrinsic instability of fractional-reserve banking.

This is a really good point; I don’t have an answer and it ties in to a lot of deep questions about the structure of the banking system and “what is money”. I do like that it’s being discussed, and I’d love to hear views (educated and layman alike) on “so if the gold standard won’t work and the Fed fucked things up so bad, what do you suggest?”

Lastly, here’s the end of the piece:

For a solution to this instability, Hayek himself ultimately looked not to the gold standard but to the rise of private monies that might compete with the government’s own. Private issuers, he argued, would have an interest in keeping the purchasing power of their monies stable, for otherwise there would be no market for them. The central bank would then have no option but to do likewise, since private parties now had alternatives guaranteed to hold their value.

Abstract and idealistic, one might say. On the other hand, maybe the Tea Party should look for monetary salvation not to the gold standard but to private monies like Bitcoin.

Um, for the record that’s long been the position of Paul. See for example this. Moreover, I think the author isn’t aware that there may be significant legal obstacles to create a competing currency.

I don’t have an answer to the many questions raised here, but they’ve been on my mind a lot. Any thoughts?

FoW

What is “publicly available data”?

As many of you know, I am fascinated with the idea of an open source ratings model, set up to compete with the current big three ratings agencies S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch. Please check out my previous posts here and here about this idea.

For that reason, I’ve recently embarked on the following thought experiment: what would it take to start such a thing? As is the case with most things quantitative and real-world, the answer is data. Lots of it.

There’s good news and bad news. The good news is there are perfectly reasonable credit models that use only “publicly available data”, which is to say data that can theoretically gleaned from quarterly filings that companies are required to file. The bad news is, the SEC filings, although available on the web, are completely useless unless you have a team of accounting professionals working with you to understand them.

Indeed what actually happens if you work at a financial firm and want to implement a credit model based on “publicly available information” is the following: you pay a data company like Compustat good money for a clean data feed to work with. They charge a lot for this, and for good reason: the SEC doesn’t require companies to standardize their accounting terms, even within an industry, and even over time (so the same company can change the way it does its accounting from quarter to quarter). Here‘s a link for the white paper (called The Impact of Disparate Data Standardization on Company Analysis) which explains the standardization process that they go through to “clean the data”. It’s clearly a tricky thing requiring true accounting expertise.

To sum up the situation, in order to get “publicly available data” into usable form we need to give a middle-man company like Compustat thousands of dollars a year. Wait, WTF?!!? How is that publicly available?

And who is this benefitting? Obviously it benefits Compustat itself, in that there even is a business to be made from converting publicly available data into usable data. Next, it obviously benefits the companies to not have to conform to standards- easier for them to hide stuff they don’t like (this is discussed in the first section of Compustat’s whitepaper referred to above), and to have options each quarter on how the presentation best suits them. So… um… does it benefit anyone besides them? Certainly not any normal person who wants to understand the creditworthiness of a given company. Who is the SEC working for anyway?

I’ve got an idea. We should demand publicly available data to be usable. Standard format, standard terminology, and if there are unavoidable differences across industries (which I imagine there are, since some companies store goods and others just deal in information for example), then there should be fully open-source translation dictionaries written in some open-source language (python!) that one can use to standardize the overall data. And don’t tell me it can’t be done, since Compustat already does it.

SEC should demand the companies file in a standard way. If there really are more than a couple of standard terms, then demand the company report in each standard way. I’m sure the accountants of the company have this data, it’s just a question of requiring them to report it.

Good for the IASB!

There’s an article here in the Financial Times which describes how the International Accounting Standards Board is complaining publicly about how certain financial institutions are lying through their teeth about how much their Greek debt is worth.

It’s a rare stand for them (in fact the article describes it as “unprecedented”), and it highlights just how much a difference in assumptions in your model can make for the end result:

Financial institutions have slashed billions of euros from the value of their Greek government bond holdings following the country’s second bail-out. The extent to which Greek sovereign debt losses were acknowledged has varied, with some banks and insurers writing down their holdings by a half and others by only a fifth.

It all comes down to whether the given institution decided to use a “mark to model” valuation for their Greek debt or a “mark to market” valuation. “Mark to model” valuations are used in accounting when the market is “sufficiently illiquid” that it’s difficult to gauge the market price of a security; however, it’s often used (as IASB is claiming here) as a ruse to be deceptive about true values when you just don’t want to admit the truth.

There’s an amusingly technical description of the mark to model valuation for Greek debt used by BNP Paribas here. I’m no accounting expert but my overall takeaway is that it’s a huge stretch to believe that something as large as a sovereign debt market is illiquid and needs mark to model valuation: true, not many people are trading Greek bonds right now, but that’s because they suck so much and nobody wants to sell them at their true price since then they’d have to mark down their holdings. It’s a cyclical and unacceptable argument.

In any case, it’s nice to see the IASB make a stand. And it’s an example where, although there are two possible assumptions one can make, there really is a better, more reasonable one that should be made.

That reminds me, here’s another example of different assumptions changing the end result by quite a lot. The “trillion dollar mistake” that S&P supposedly made was in fact caused by them making a different assumption than that which the White House was prepared to make:

As it turns out, the sharpshooters were wide of the target. S&P didn’t make an arithmetical error, as Summers would have us believe. Nor did the sovereign-debt analysts show “a stunning lack of knowledge,” as Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner claimed. Rather, they used a different assumption about the growth rate of discretionary spending, something the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office does regularly in its long-term outlook.

CBO’s “alternative fiscal scenario,” which S&P used for its initial analysis, assumes discretionary spending increases at the same rate as nominal gross domestic product, or about 5 percent a year. CBO’s baseline scenario, which is subject to current law, assumes 2.5 percent annual growth in these outlays, which means less new debt over 10 years.

Is anyone surprised about this? Not me. It also goes under the category of “modeling error”, which is super important for people to know and to internalize: different but reasonable assumptions going into a mathematical model can have absolutely huge effects on the output. Put another way, we won’t be able to infer anything from a model unless we have some estimate of the modeling error, and in this case we see the modeling error involves at least one trillion dollars.

Why log returns?

There’s a nice blog post here by Quantivity which explains why we choose to define market returns using the log function:

where denotes price on day

.

I mentioned this question briefly in this post, when I was explaining how people compute market volatility. I encourage anyone who is interested in this technical question to read that post, it really explains the reasoning well.

I wanted to add two remarks to the discussion, however, which actually argue for not using log returns, but instead using percentage returns in some situations.

The first is that the assumption of a log-normal distribution of returns, especially over a longer term than daily (say weekly or monthly) is unsatisfactory, because the skew of log-normal distribution is positive, whereas actual market returns for, say, S&P is negatively skewed (because we see bigger jumps down in times of panic). You can get lots of free market data here and try this out yourself empirically, but it also makes sense. Therefore when you approximate returns as log normal, you should probably stick to daily returns.

Second, it’s difficult to logically combine log returns with fat-tailed distributional assumptions, even for daily returns, although it’s very tempting to do so because assuming “fat tails” sometimes gives you more reasonable estimates of risk because of the added kurtosis. (I know some of you will ask why not just use no parametric family at all and just bootstrap or something from the empirical data you have- the answer is that you don’t ever have enough to feel like that will be representative of rough market conditions, even when you pool your data with other similar instruments. So instead you try different parametric families and compare.)

Mathematically there’s a problem: when you assume a student-t distribution (a standard choice) of log returns, then you are automatically assuming that the expected value of any such stock in one day is infinity! This is usually not what people expect about the market, especially considering that there does not exist an infinite amount of money (yet!). I guess it’s technically up for debate whether this is an okay assumption but let me stipulate that it’s not what people usually intend.

This happens even at small scale, so for daily returns, and it’s because the moment generating function is undefined for student-t distributions (the moment generating function’s value at 1 is the expected return, in terms of money, when you use log returns). We actually saw this problem occur at Riskmetrics, where of course we didn’t see “infinity” show up as a risk number but we saw, every now and then, ridiculously large numbers when we let people combine “log returns” with “student-t distributions.” A solution to this is to use percentage returns when you want to assume fat tails.

We didn’t make money on TARP!

There’s a pretty good article here by Gretchen Morgenson about how the banks have been treated well compared to average people- and since I went through the exercise of considering whether corporations are people, I’ve decided it’s misleading yet really useful to talk about “treating banks” well- we should keep in mind that this is shorthand for treating the people who control and profit from banks well.

On thing I really like about the article is that she questions the argument that you hear so often from the dudes like Paulson who made the decisions back then, namely that it was better to bail out the banks than to do nothing. Yes, but weren’t there alternatives? Just as the government could have demanded haircuts on the CDS’s they bailed out for AIG, they could have stipulated real conditions for the banks to receive bailout money. This is sort of like saying Obama could have demanded something in return for allowing Bush’s tax cuts for the rich to continue.

But on another issue I think she’s too soft. Namely, she says the following near the end of the article:

As for making money on the deals? Only half-true, Mr. Kane said. “Thanks to the vastly subsidized terms these programs offered, most institutions were eventually able to repay the formal obligations they incurred.” But taxpayers were inadequately compensated for the help they provided, he said. We should have received returns of 15 percent to 20 percent on our money, given the nature of these rescues.

Hold on, where did she get the 15-20%? As far as I’m concerned there’s no way that’s sufficient compensation for the future option to screw up as much as you can, knowing the government has your back. I’d love to see how she modeled the value of that. True, it’s inherently difficult to model, which is a huge problem, but I still think it has to be at least as big as the current credit card return limits! Or how about the Payday Loans interest rates?

I agree with her overall point, though, which is that this isn’t working. All of the things the Fed and the Treasury and the politicians have done since the credit crisis began has alleviated the pain of banks and, to some extent, businesses (like the auto industry). What about the people who were overly optimistic about their future earnings and the value of their house back in 2007, or who were just plain short-sighted, and who are still in debt?

It enough to turn you into an anarchist, like David Graeber, who just wrote a book about debt (here’s a fascinating interview with him) and how debt came before money. He thinks we should, as a culture, enact a massive act of debt amnesty so that the people are no longer enslaved to their creditors, in order to keep the peace.

I kind of agree- why is it so much easier for institutions to get bailed out when they’ve promised too much than it is for average people crushed under an avalanche of household debt? At the very least we should be telling people to walk away from their mortgages or credit card debts when it’s in their best interest (and we should help them understand when it is in their best interest).