Archive

The sin of debt (part 2)

I wrote a post about a month ago about the sin of debt and how, for normal people, debt carries a moral weight that isn’t present for corporations (even though corporations are people). Since then I’ve noticed some egregious examples of this phenomenon which I want to share with you.

Warning: this post contains really sickening stuff. I usually try to think of how to solve problems (I really do!) but today I’m just in awe of the problems themselves. Maybe I’ll eventually come up with a “part 3” for this post and have some good, proactive ideas (please help!).

First, there’s this article from the Wall Street Journal which discusses the fact that people are being arrested and put in jail for their credit card, auto loan, and other debt:

More than one-third of U.S. states allow borrowers who can’t or won’t pay to be jailed. Nationwide statistics aren’t known because many courts don’t keep track of warrants by alleged offense, but a tally by The Wall Street Journal earlier this year of court filings in nine counties across the U.S. showed that judges signed off on more than 5,000 such warrants since the start of 2010.

…

Some judges have criticized the use of such warrants, comparing them to a modern-day version of debtors’ prison. Ms. Madigan said she has grown increasingly concerned that borrowers sometimes are being thrown into jail without even knowing they were sued, a problem she blames on sloppy, incomplete or false paperwork submitted to courts.

Outrageous. To contrast that, let’s take a peek at the tone of a Reuters article on AMR bankruptcy filing; AMR is the parent company of American Airlines. From the article:

American plans to operate normally while in bankruptcy, but the Chapter 11 filing could punch a hole in the pensions of roughly 130,000 workers and retirees.

AMR pension plans are $10 billion short of what the carrier owes, and any default could be the largest in U.S. history, government pension insurers estimated.

Ray Neidl, aerospace analyst at Maxim Group, said a lack of progress in contract talks with pilots tipped the carrier into Chapter 11, though it has enough cash to operate. The carrier’s passenger planes average 3,000 daily U.S. departures.

“They were proactive,” Neidl said. “They should have adequate cash reserves to get through this.”

So from where I stand, it looks like this company is being applauded for its bankruptcy filing because it’s such a great opportunity to get rid of pesky pensions from its 130,000 workers and retirees. Note there’s nothing about AMR or American Airlines executives being arrested and brought to jail here.

Finally, there’s the “debt as sin” theme amplified by mourning. This Wall Street Journal article describes the practice that debt collection agencies use to harass the living relatives of people who have passed away in debt. From the article:

Debt collectors often tell surviving family members that they aren’t personally responsible for paying the debts of the deceased. But those words barely register with grieving relatives, according to interviews with a dozen lawyers who represent about 60 families pursued for money owed by dead relatives.

“Each call brought up fresh memories of my husband’s death,” Patricia Smith, 56, says about the calls she started getting last year about $1,787.04 in credit-card debt owed by her late husband, Arthur.

The debt-collection calls and letters kept coming and wore her down, says Mrs. Smith, who lives in Jackson, Miss. She agreed to scrounge together $50 a month “just to make the calls stop.”

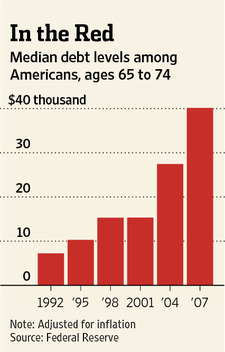

The Wall Street Journal provides a graphic to explain why this is a growing field for debt collectors:

You might ask what the relevant regulator, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), is doing about this practice. From the article:

Still, the agency determined the previous guidelines were ineffective and “too constricting,” Mr. Dolan says. So, in July, the agency issued a policy statement. Before the new guidelines, collectors were supposed to discuss a dead person’s debt only with the person’s spouse or someone chosen by the dead person’s estate. But Mr. Dolan said few debtors are formally designating someone to handle their affairs after death, leaving debt-collection firms unable to determine whom to contact for payment of any outstanding bills.

The FTC sought to improve the process and now allows debt-collection firms to contact anyone believed to be handling the estate, including parents, friends and neighbors. Agency officials wanted to resolve a “tension that was emerging” between state and U.S. laws on how collectors can go after money, Mr. Dolan adds. “While people might think it is horrible for collectors to speak with surviving spouses, we have no power to change that.”

FTC officials rejected requests by lawyers representing family members for an outright ban on calling surviving family members. The agency also declined to impose a cooling-off period during which relatives couldn’t be contacted by debt collectors.

Thanks, FTC! Thanks for representing the little guy, with the dead wife.

Conservation Law of Money

Being a mathematician, I’ve always been on the lookout for quantitative statements about the financial system as a whole that explain large economic phenomena. Just for the satisfaction of it all.

For example, I think it’s possible that many bubbles (dot com, Japanese stocks) can be explained simply by saying that, when normal people, rather than professional investors, are putting their money in the market, then the market is gonna go up. And moreover, when that happens, we can throw away any silly ideas we may have been harboring about price as indicator of true value; the prices are going up because the public is inflating the market with more cash money.

In other words, the opportunities for good investing doesn’t keep up with the cash flow in those moments. We could go further and say that there’s a kind of seasonality of money flow, which is dominating the market signal at times like these, just like you see in housing markets (when the housing market is functional) in the springtime when humans come out of their hibernation and feel like nesting and mating.

There are other ways for seasonality of money flow to affect the market without introducing newcomers to the market, such as inflation or deflation, where the value of the existing money itself changes. or when there’s an outside force either extracting or adding to the money supply, like the Saudi Arabia or China, although that’s more of a continual drag than a sudden jolt.

I think we may be encountering a very real “Conservation Law of Money” situation with the European debt crisis. Namely, there are all these banks that are on the prowl for cash, since they’re worried about being undercapitalized, with good reason: they are still hanging on to many toxic assets from the credit crisis, and in the meantime their enormous government bond holdings are going to pot. In the meantime Basel III, a new regulatory regime, will be in effect in 2015 and requires much more liquid, high quality assets than they currently own.

But here’s the thing, and it’s not a new observation but it’s an important one: not all of those banks can recover, unless something dramatic happens. From BusinessWeek:

“There aren’t enough assets in the world that are genuinely liquid and of high enough quality to allow all the banks to meet this ratio,” said Barbara Ridpath, chief executive officer of the International Centre for Financial Regulation, a London research group funded by banks and the U.K. government. “And that’s only likely to get worse because of the changing credit quality of some of the sovereigns.”

Mathematically speaking we have an impossibility: way more required stuff than existing stuff inside the current European system. What’s gonna give? Here’s a list of the things I can think of:

- Basel III will be scrapped and Europe will live with an enormous zombie system,

- the ECB will start printing money and eventually inflate the system out of insolvency,

- the banking system will fight to the death over the scarce resources and thereby be massively shrinked (but probably the few surviving banks will be politically well-places too-big-to-fail behemoths),

- European citizens will foot the bill through bailouts and then taxes, possibly leading to widespread civil unrest or even war, or

- outsiders will step in when the price is right (China and/or the Middle East) and end up owning the European banks.

There may be others options as well (please tell me). Of the above though I guess I prefer 3, where Europe ends up with a few huge banks that are highly regulated and well-capitalized. This is the Australian model and I posted about it here. Maybe then the financial system can be allowed to be utility-bank oriented and boring and smart young people will apply their energy outside of financial engineering.

Resampling

I’m enjoying reading and learning about agile software development, which is a method of creating software in teams where people focus on short and medium term “iterations”, with the end goal in sight but without attempting to map out the entire path to that end goal. It’s an excellent idea considering how much time can be wasted by businesses in long-term planning that never gets done. And the movement has its own manifesto, which is cool.

The post I read this morning is by Mike Cohn, who seems heavily involved in the agile movement. It’s a good post, with a good idea, and I have just one nerdy pet peeve concerning it.

I’m a huge fan of stealing good ideas from financial modeling and importing them into other realms. For example, I stole the idea of stress testing of portfolios and use them in stress testing the business itself where I work, replacing scenarios like “the Dow drops 9% in a day” with things like, “one of our clients drops out of the auction.”

I’ve also stolen the idea of “resampling” in order to forecast possible future events based on past data. This is particularly useful when the data you’re handling is not normally distributed, and when you have quite a few data points.

To be more precise, say you want to anticipate what will happen over the next week (5 days) with something. You have 100 days of daily results in the past, and you think the daily results are more or less independent of each other. Then you can take 5 random days in the past and see how that “artificial week” would look if it happened again. Of course, that’s only one artificial week, and you should do that a bunch of times to get an idea of the kind of weeks you may have coming up.

If you do this 10,000 times and then draw a histogram, you have a pretty good sense of what might happen, assuming of course that the 100 days of historical data is a good representation of what can happen on a daily basis.

Here comes my pet peeve. In Mike Cohn’s blog post, he goes to the trouble of resampling to get a histogram, so a distribution of fake scenarios, but instead of really using that as a distribution, for the sake of computing a confidence interval, he only computes the average and standard deviation and then replaces the artificial distribution with a normal distribution with those parameters. From his blog:

Armed with 200 simulations of the ten sprints of the project (or ideally even more), we can now answer the question we started with, which is, How much can this team finish in ten sprints? Cells E17 and E18 of the spreadsheet show the average total work finished from the 200 simulations and the standard deviation around that work.

In this case the resampled average is 240 points (in ten sprints) with a standard deviation of 12. This means our single best guess (50/50) of how much the team can complete is 240 points. Knowing that 95% of the time the value will be within two standard deviations we know that there is a 95% chance of finishing between 240 +/- (2*12), which is 216 to 264 points.

What? This is kind of the whole point of resampling, that you could actually get a handle on non-normal distributions!

For example, let’s say in the above example, your daily numbers are skewed and fat-tailed, like a lognormal distribution or something, and say the weekly numbers are just the sum of 5 daily numbers. Then the weekly numbers will also be skewed and fat-tailed, although less so, and the best estimate of a 95% confidence interval would be to sort the scenarios and look at the 2.5th percentile scenario, the 97.5th percentile scenario and use those as endpoints of your interval.

The weakness of resampling is the possibility that the data you have isn’t representative of the future. But the strength is that you get to work with a honest-to-goodness distribution and don’t need to revert to assuming things are normally distributed.

Thank you, Inside Job

The documentary Inside Job put a spotlight on conflict of interest for “experts,” specifically business school and economic professors at well-known universities. The conflict was that they’d be consulting for some firm or government, getting paid tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, and would then write academic papers investigating the methods of that firm or government, without disclosing the payments.

Since it’s human nature to do so, these academic papers would end up supporting those methods, more often than not, even when the methods weren’t sound. I’m being intentionally generous, because the alternative is to think that they actually sell their endorsements; I’m sure that happens, but I’m guessing it isn’t always a conscious, deliberate decision.

Last Spring, the Columbia Business School changed its conflict of interest policy to address this exact problem. From the Columbia Spectator Article:

Under the new policy, Business School professors will be required to publicly disclose all outside activities—including consulting—that create or appear to create conflicts of interest.

“If there is even a potential for a conflict of interest, it should be disclosed,” Business School professor Michael Johannes said in an email. “To me, that is what the policy prescribes. That part is easy.”

The policy passed with “overwhelming” faculty support at a Tuesday faculty meeting, according to Business School Vice Dean Christopher Mayer, who chaired the committee that crafted the policy.

The new policy mandates that faculty members publish up-to-date curricula vitae, including a section on outside activities, on their Columbia webpages. In this section, they will be required to list outside organizations to which they have provided paid or unpaid services during the past five years, and which they think creates the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Good for them!

Next up: the Harvard Business School. I don’t think they yet have a comparable policy. When you google for “Harvard Business School conflict of interest” you get lots of links to HBS papers written about conflict of interest, for other people. Interesting.

I don’t understand what the reasoning could be that they are stalling. Is there some reason Harvard Business School professors wouldn’t want to disclose their outside consulting gigs? I mean, we already know about them advising Gaddafi back in 2006, so that can’t be it. Just in case you missed that, here’s an excerpt from the Harvard Crimson article from last Spring:

But Harvard professors have focused on the political conclusions of the report, which, among a set of recommendations, indicated that Libya was a functioning democracy and heralded the country’s system of local political gatherings as “a meaningful forum for Libyan citizens to participate directly in law-making.”

The report was a product of Monitor’s work consulting for Gaddafi from 2006 to 2008. The Libyan government—headed by Gaddafi, who has ruled since a 1969 military coup—hired consultants from Monitor Group to provide policy recommendations, economic advice, and several other services.

The consulting group carries a distinct Harvard flavor. On its website, the company touts the Harvard ties of several of its founders and current leaders.

I’m wondering if this would have happened if there already was a conflict of interest policy, like Columbia’s, in place. And I’m focusing on Harvard because if both Harvard and Columbia set such policies, I think other places will follow. As far as I can see, this is just as important as conflict of interest policies for doctors with respect to drug companies.

ISDA has a blog!

ISDA, or International Swaps and Derivatives Organization, is an organization which sets the market standards in a bunch of ways for credit default swap (CDS) and other over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, in particular they legally define CDS and other swaps and have standard forms for other people to use to enter into such contracts. They also have a committee which decides when a CDS has been triggered, which is a big deal with all the Euro debt restructuring that’s happened and will probably continue to happen.

Anyhoo, what I wanted to mention today is their blog. Actually they have two, one for internal blogging about what they’re up to, and the other for responding to media comments about them.

What’s crazy about these blogs is that they’re well written and… funny. Yeah. You wouldn’t expect that from a legal organization which oversees OTC derivatives, but there you have it. Or else, maybe that just means I’m a complete and utter finance nerd.

And they’re also informative. This post talks about their decision to sue the CFTC for some position limits rule they don’t like. One of their arguments is that the CFTC ignored public comments and cost-benefit analysis which would have loosened the rule or argued against them, and they’re hoping that by suing they can at least force the CFTC to explain how they took into account the public comments.

This argument matters to me because I am involved with the Occupy the SEC folk (OMG those guys are relentless) in preparing public comments for the Volcker Rule, and until now I didn’t know what it meant that there will be public comments and someone has to read them. I mean, I still don’t, really, but it is certainly exciting to see if the CFTC’s hand will be forced in this matter.

Their media blog is informative too. This post talks about how misleading some of the media reports were about why MF Global tanked- it was through repos, not OTC derivatives. True! And by the way, also relevant to the Volcker Rule people, since repos are not considered risky trading in the Volcker Rule. Big huge hole! Doesn’t anybody remember the stuff that Lehman was doing near then end with repos? At the very least they are tools of deception, and need to be taken into account.

Obviously everything they say about CDS and the OTC market is pro-them, but that’s okay. They’re at least saying stuff. I’m impressed!

Good bank/ bad bank – why we didn’t do it

Today’s guest post is written by my aunt, the economist Susan Woodward. I recently found a paper she had written which proposed to split up banks into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ banks. This is an idea I’ve heard bandied about, and it always sounded like a good one and moreover one that’s seemingly worked in other countries. “Why hasn’t this happened?” I asked. This is her response:

—————————————————-

The good bank/bad bank idea is kaput. “We” (the US) did not do it because

1) it would have re-written the contract between the bank bondholders and equity holders. If the govt forced this, it would have given the bondholders the right to sue for damages for the losses imposed on them, and likely they would have won, as many thrifts did when FIRREA (1989) changed the deal ex post.

2) the only point of it would be to leave the “good” bank with plenty of equity so that it could fund its commercial paper smoothly and cheaply. Any other workout or guarantee would do the same thing, and the other loans (now we know, $7.8 trillion dollars worth) and guarantees did do the same thing. The big US banks are still undercapitalized, but forcing them to raise equity right now is sort of impossible politically. So instead we just don’t let them do anything exciting and avert our gaze from the non-performing mortgages they have not yet written-down. I know that BofA is selling its above-water mortgages in order to book gains.

But I confess I am baffled by bank accounting now — it is a mix of assets (and liabilities!) marked-to-market and others not, by logic that eludes me. In Citi’s last earnings report, a large fraction of “earnings” was a decline in the value of its bonds (if a rise in the value of an asset is income, so is a decline in the value of a liability, it is not entirely crazy, just not done much before) because markets assigned a lower likelihood to them paying the bondholders. What a reporting convention. oh dear.

Citi and BofA are maybe broke anyway. Their market caps are both below $80 billion (depending on the temperature of the Euro mess) on assets of about $2 trillion each. I imagine that various parts of the govt are working on contingency plans for orderly dismantling of them. Just in case.

As for European banks, they may need lots and lots of help, depending on what Europe does about the ECB and its ability to issue bonds, buy bank assets, and, ulp, collect TAXES. All of the pundits are right that if the ECB could buy sovereign bonds and bank bonds, it could fend off a meltdown at least for now. The US Fed has bought 11% of GDP’s worth of US bonds, and the UK has done 13%. So it is not a new or unknown strategy. But in the US and the UK, the power to tax as well as the power to print money lies behind the institution.

The situation is somewhat like the original States after 1779, when the new constitution reserved the right to print money to the federal government, and took it away from the States. The first federal power to tax was not direct, but worked through telling each state what share it owed, then counting on the States to raise the money, sort of like the ECB now. When the Federal govt finally got the power to tax directly, the value of its bonds, 23 cents on the dollar in the early chaotic years, rose to par, then above par. The federal assumption of the States’ expenses for the revolutionary war resulted in a deal — Virginia, which was very prosperous and had paid off some of its war debt, agreed for the deal to assume the burden of Massachusetts, which had not paid off so much and in any case also had a heavier burden in the revolutionary war, in exchange for moving the capital from New York to Philly (temporarily), then on to Washington. The deal was cut at a dinner party in New York attended by Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton. I wonder what wine was poured.

In those early years, States funded their state-level budgets with earnings from owning shares in banks they chartered! And the previous colonies funded their budgets from mortgage lending! So much for the separation of finance and government.

Were Massachusetts and Virginia then more similar to each other then than Germany and Italy are now? Not so clear.

Writing clear and helpful things about the financial crisis is not easy and takes heaps of time, which is why we quit doing it. But hey, if you have it, go for it.

love, Aunt Susie

Hank Paulson

A few days ago it came out that former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson is a complete asshole. Some people knew this already, but Felix Salmon kind of nailed it permanently to the wall with this Reuters column where he describes how Paulson told his buddies all about what was going on in the credit crisis a few weeks or days before the public was informed. Just in case descriptions of his behavior aren’t clear enough, Salmon ends his column with this delicious swipe:

Paulson, says Teitelbaum, “is now a distinguished senior fellow at the University of Chicago, where he’s starting the Paulson Institute, a think tank focused on U.S.-Chinese relations”. I’d take issue with the “distinguished” bit. Unless it means “distinguished by an astonishing black hole where his ethics ought to be”.

Here’s another thing that people may want to know about Paulson, and which some people know already but should be more loudly broadcast: he dodged tens of millions of dollars in taxes by becoming the Treasure Secretary. This article from the Daily Reckoning explains the conditions:

Under the guise of not wanting to “discourage able citizens from entering public service,” Section 1043 is an alteration of the government’s conflict of interest rules. Before 1043, executive appointees (mostly high-up cabinet members and judges) had to sell positions in certain companies to combat conflict of interest – like say, a former Goldman Sachs CEO-turned Treasury Secretary with millions of GS shares. After Sec. 1043, the appointee gets a one-time rollover. Upon their appointment, he or she can transfer their shares to a blind trust, a broad market fund or into treasury bonds. They’ll have to pay taxes on the position one day, but not immediately after the sale… like the rest of us.

I’m a big believer in incentives. And from where I sit, when you piece together Hank Paulson’s incentives, you get his actions. In some sense we shouldn’t even complain that he’s such an asshole, because we invented this system to let people like him act in these asshole ways.

[It brings up another related topic, namely that the level of corruption and misaligned incentives actually drives ethical people out of finance altogether. I want to devote more time to think about this, but as partial evidence, consider how few “leaders” from the financial world have stepped up and supported Occupy Wall Street, or for that matter any real challenge to business as usual. At the same time there are plenty of people in finance who are part of the movement, but they tend to be the foot soldiers, or young, or both. Maybe I’m wrong- maybe there are plenty of senior people who just are remaining anonymous, doing their thing to undermine the status quo, and I just haven’t met them. According to this article which I linked to already for a different reason, and which corroborates my experience, there are lots of people who see the rot but not too many doing anything about it.]

Here’s what we do. We ask people who want to be public servants to sacrifice something (besides their ethics) to actually serve the public. I’m convinced that there really are people who would do this, especially if the system were set up more decently. We don’t need to offer huge cash incentives to attract people like Paulson to be Treasury Secretary.

update: I’m not the only person who thinks like this.

Various #OWS links

Here’s an internal Fed blog describing an internal Fed report which proposes that we tie banker bonuses to the CDS spread of the bank. The crux of the idea:

Under our scheme, a high or increasing CDS spread would translate into a lower cash bonus, and vice versa. For banks that do not have a liquid CDS market, the bonus could be tied to the institution’s borrowing cost as proxied by the debt spread. However, the CDS spread has the benefit of being market based, and can be chosen optimally. It is the closest analogue a bank has to a stock price—it is the market price of credit risk. If CEO deferred compensation were tied directly to the bank’s own CDS spread, bank executives would have a direct financial exposure to the bank’s underlying risk and would have an incentive to reduce risk that does not enhance the value of the enterprise.

It’s an interesting idea and I’ll think about it more. I have two concerns off the bat though. First, the blog (I didn’t read the paper) acts like CDS can be honestly taken as a proxy for likeliness to default. However in the real world everything is juiceable. So this scheme will give people more incentives to push for, among other things, fraudulent accounting to avoid looking risky. My second concern is an add-on to the first: the insiders, who benefit directly from low CDS spread, will have very direct reasons to perpetuate such accounting fraud. Somehow I’d love to see (if possible) a scheme put forth where insiders have incentives to ferret out and expose fraud.

———

A beautiful post about the metamovement of which OWS is a part, by Umair Haque. A piece:

In a sense, that sentiment is the common thread behind each and every movement in the Metamovement — a sense of grievous injustice, not merely at the rich getting richer, but at the loss of human agency and sovereignty over one’s own fate that is the deeper human price of it.

He links to We Are the 99 Percent. Check it out if you haven’t already seen it.

———

Interfluidity blogs about how yes, the bankers really were bailed out. Big time. Great points, here is my favorite part:

Cash is not king in financial markets. Risk is. The government bailed out major banks by assuming the downside risk of major banks when those risks were very large, for minimal compensation. In particular, the government 1) offered regulatory forbearance and tolerated generous valuations; 2) lent to financial institutions at or near risk-free interest rates against sketchy collateral (directly or via guarantee); 3) purchased preferred shares at modest dividend rates under TARP; 4) publicly certified the banks with stress tests and stated “no new Lehmans”. By these actions, the state assumed substantially all of the downside risk of the banking system. The market value of this risk-assumption by the government was more than the entire value of the major banks to their “private shareholders”. On commercial terms, the government paid for and ought to have owned several large banks lock, stock, and barrel. Instead, officials carefully engineered deals to avoid ownership and control.

———

Next, read this Newsweek article if you’re still wondering what Mayor Bloomberg’s personal incentives are for letting OWS complain about crony capitalism and the power of lobbyists. The scariest part:

Let’s say a lobbyist for a coal company wants to squash any legislation that affects his employer’s mining operations. He logs onto BGov.com (the cost is $5,700 per year) and is automatically alerted to breaking news of a just-introduced energy bill. The data drill-down begins. BGov shows the lobbyist how similar legislation has fared, what subcommittee the new bill will face and when, who the key congressmen are, and how they have voted in the past. The lobbyist calls up information on the swing vote’s upcoming election contest: it’s competitive, and the congressman is behind in fundraising. Lists of major donors—who might be induced to contribute or, better yet, place a call to the officeholder himself—are a click away. These political pressure points and a thousand more are how lobbyists make their mark, and Bloomberg thinks BGov can deliver them faster than the competition.

———

Finally, a very nice blog about the Alternative Banking group and David Graeber by Joe Sucher. Here’s an excerpt:

I know the usual naysayers will nay say until they are blue in the face about changing the so-called system. “It will never happen, never will, so let’s wait for things to settle down and go back to business as usual.” These folks, I’d venture to say, may be exhibiting a fundamental crisis of imagination.

I remember an elderly immigrant anarchist reminded me (when I was naysaying) that if you were to tell a 14th century European serf, that some time in the next few hundred years, they’d actually have the ability to cast a vote that mattered, no doubt you’d be met with a blank stare. The thought just wouldn’t compute.

——–

updated: Jesse Eisenger of Propublica wrote this interesting article in DealBook, where he talks about the insiders on the Street who are frustrated by the rampant corruption. I agree with a lot he says but he clearly needs to join us at an Alternative Banking group meeting:

It’s progress that these sentiments now come regularly from people who work in finance. This is an unheralded triumph of the Occupy Wall Street movement. It’s also an opportunity to reach out to make common cause with native informants.

It’s also a failure. One notable absence in this crisis and its aftermath was a great statesman from the financial industry who would publicly embrace reform that mattered. Instead, mere months after the trillions had flowed from taxpayers and the Federal Reserve, they were back defending their prerogatives and fighting any regulations or changes to their business.

Perhaps a major reason so few in this secret confederacy speak out is that they are as flummoxed about practical solutions as the rest of us. They don’t know where to begin.

Um, there are plenty of very good places to begin. It’s a question of politics, not of solutions. Start with the very basics: enforce the rules that already exist. Give the SEC some balls. We’ll go from there. Sheesh!

Correlated trades

One major weakness of quantitative trading is that it’s based on the concept of how correlated various instruments and instrument classes are. Today I’m planning to rant about this, thanks to a reader who suggested I should. By the way, I do not suggest that anything in today’s post is new- I’m just providing a public service by explaining this stuff to people who may not know about it.

Correlation between two things indicates how related they are. The maximum is 1 and the minimum is -1; in other words, correlation ignores the scale of the two things and concentrates only on the de-scaled relationship. Uncorrelated things have correlation 0.

All of the major financial models (for example Modern Portfolio Theory) depend crucially on the concept of correlation, and although it’s known that, at a point in time, correlation can be measured in many different ways, and even given a choice, the statistic itself is noisy, most of the the models assume it’s an exact answer and never bother to compute the sensitivity to error. Similar complaints can just as well be made to the statistic “beta”, for example in the CAPM model.

To compute the correlation between two instruments X and Y, we list their returns, defined in a certain way, for a certain amount of time for a given horizon, and then throw those two series into the sample correlation formula. For example we could choose log or percent returns, or even difference returns, and we could look back at 3 months or 30 years, or have an exponential downweighting scheme with a choice of decay (explained in this post), and we could be talking about hourly, daily, or weekly return horizons (or “secondly” if you are a high frequency trader).

All of those choices matter, and you’ll end up with a different answer depending on what you decide. This is essentially never mentioned in basic quantitative modeling texts but (obviously) does matter when you put cash money on the line.

But in some sense the biggest problem is the opposite one. Namely, that people in finance all make the same choices when they compute correlation, which leads to crowded trades.

Think about it. Everyone shares the same information about what the daily closes are on the various things they trade on. Correlation is often computed using log returns, at a daily return horizon, with an exponential decay weighting typically 0.94 or 0.97. People in the industry thus usually agree more or less on the correlation of, say, the S&P and crude.

[I’m going to put aside the issue that, in fact, most people don’t go to the trouble of figuring out time zone problems, which is to say that even though the Asian markets close earlier in the day than the European or U.S. markets, that fact is ignored in computing correlations, say between country indices, and this leads to a systematic miscalculation of that correlation, which I’m sure sufficiently many quantitative traders are busy arbing.]

Why is this general agreement a problem? Because the models, which are widely used, tell you how to diversify, or what have you, based on their presumably perfect correlations. In fact they are especially widely used by money managers, so those guys who move around pension funds (so have $6 trillion to play with in this country and $20 trillion worldwide), with enough money involved that bad assumptions really matter.

It comes down to a herd mentality thing, as well as cascading consequences. This system breaks down at exactly the wrong time, because after everyone has piled into essentially the same trades in the name of diversification, if there is a jolt on the market, those guys will pull back at the same time, liquidating their portfolios, and cause other managers to lose money, which results in that second tier of managers to pull back and liquidate, and it keeps going. In other words, the movements among various instruments become perfectly aligned in these moments of panic, which means their correlation approaches 1 (or perfectly unaligned, so their correlations approach -1).

The same is true of hedge funds. They don’t rely on the CAPM models, because they are by mandate trying to be market neutral, but they certainly rely on a factor-model based risk model, in equities but also in other instrument classes, and that translates into the fact that they tend to think certain trades will offset others because the correlation matrix tells them so.

These hedge fund quants move around from firm to firm, sharing their correlation matrix expertise, which means they all have basically the same model, and since it’s considered to be in the realm of risk management rather than prop trading, and thus unsexy, nobody really spends too much time trying to make it better.

But the end result is the same: just when there’s a huge market jolt, the correlations, which everyone happily computed to be protecting their trades, turn out to be unreliable.

One especially tricky thing about this is that, since correlations are long-term statistics, and can’t be estimated in short order (unless you look at very very small horizons but then you can’t assume those correlations generalize to daily returns), even if “the market is completely correlated” on one day doesn’t mean people abandon their models. Everyone has been trained to believe that correlations need time to bear themselves out.

In this time of enormous political risk, with the Eurozone at risk of toppling daily, I am not sure how anyone can be using the old models which depend on correlations and sleep well at night. I’m pretty sure they still are though.

I think the best argument I’ve heard for why we saw crude futures prices go so extremely high in the summer of 2008 is that, at the time, crude was believed to be uncorrelated to the market, and since the market was going to hell, everyone wanted “exposure” to crude as a hedge against market losses.

What’s a solution to this correlation problem?

One step towards a solution would be to stop trusting models that use greek letters to denote correlation. Seriously, I know that sounds ridiculous, but I’ve noticed a correlation between such models and blind faith (I haven’t computed the error on my internal estimate though).

Another step: anticipate how much overcrowding there is in the system. Assume everyone is relying on the same exact estimates of correlations and betas, take away 3% for good measure, and then anticipate how much reaction there will be the next time the Euroleaders announce a new economic solution and then promptly fail to deliver, causing correlations to spike.

I’m sure there are quants out there who have mastered this model, by the way. That’s what quants do.

At a higher perspective, I’m saying that we need to stop relying on correlations as fixed over time, and start treating them as volatile as prices. We already have markets in volatility; maybe we need markets in correlations. Or maybe they already exist formally and I just don’t know about them.

At an even higher perspective, we should just figure out a better system altogether which doesn’t put people’s pensions at risk.

Two pieces of good news

I love this New York Times article, first because it shows how much the Occupy Wall Street movement has resonated with young people, and second because my friend Chris Wiggins is featured in it making witty remarks. It’s about the investment bank recruiting machine on college campuses (Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Dartmouth, etc.) being met with resistance from protesters. My favorite lines:

Ms. Brodsky added that she had recently begun openly questioning the career choices of her finance-minded friends, because “these are people who could be doing better things with their energy.”

Kate Orazem, a senior in the student group, added that Yale students often go into finance expecting to leave after several years, but end up staying for their entire careers.

“People are naïve about how addictive the money is going to be,” she said.

Amen to that, and wise for you to know that! There are still plenty of my grown-up friends in finance who won’t admit that it’s a plain old addiction to money keeping them in a crappy job where they are unhappy, and where they end up buying themselves expensive trips and toys to try to combat their unhappiness.

And here’s my friend Chris:

“Zero percent of people show up at the Ivy League saying they want to be an I-banker, but 25 and 30 percent leave thinking that it’s their calling,” he said. “The banks have really perfected, over the last three decades, these large recruitment machines.”

Another piece of really excellent new: Judge Rakoff has come through big time, and rejected the settlement between the SEC and Citigroup. Woohoo!! From this Bloomberg article:

In its complaint against Citigroup, the SEC said the bank misled investors in a $1 billion fund that included assets the bank had projected would lose money. At the same time it was selling the fund to investors, Citigroup took a short position in many of the underlying assets, according to the agency.

“If the allegations of the complaint are true, this is a very good deal for Citigroup,” Rakoff wrote in today’s opinion. “Even if they are untrue, it is a mild and modest cost of doing business.”

A revised settlement would probably have to include “an agreement as to what the actual facts were,” said Darrin Robbins, who represents investors in securities fraud suits. Robbins’s firm, San Diego-based Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP, was lead counsel in more settled securities class actions than any other firm in the past two years, according to Cornerstone Research, which tracks securities suits.

Investors could use any admissions by Citigroup against the bank in private litigation, he said.

This raises a few questions in my mind. First, do we really have to depend on a randomly chosen judge having balls to see any kind of justice around this kind of thing? Or am I allowed to be hopeful that Judge Rakoff has now set a precedent for other judges to follow, and will they?

Second, something that came up on Sunday’s Alt Banking group meeting. Namely, how many more cases are there that the SEC hasn’t even bothered with, even just with Citigroup? I’ve heard the SEC was only scratching the surface on this, since that’s their method.

Even if they only end up getting $285m, plus the admission that they did wrong by their clients, could the SEC go back and prosecute them for 30 other deals for 30x$285m = $8.55b? Would that give us enough leverage to break up Citigroup and start working on our “Too Big to Fail” problems? And how about the other banks? What would this litigation look like if the SEC were really trying to kick some ass?

Regulation arbitrage, the Volcker Rule, and TBTF (#OWS)

Regulation arbitrage

We had a interesting, lively #OWS Alternative Banking group meeting yesterday, where we split into three groups: the Volcker Rule commenting group, the shadow banking system, and Too Big to Fail (TBTF). I was impressed by the number of people who could come even on Thanksgiving weekend.

These topics have lots of overlap, a fact which came through at the end when we got back together and disseminated our thoughts. Specifically, the question of “regulation arbitrage” came up repeatedly. This is the idea that, no matter what laws you pass on how the banks can behave, they will get around the spirit of the law with some clever sleight of hand. In other words, it’s really hard to avoid a bad outcome if you have to list all of the things that someone isn’t allowed to do- they can avoid a rule governing having repos of no longer than 7 days by inventing a new instrument, which they may call a “nepo,” which has an 8 day lifespan.

It’s frustrating, since real regulation is clearly needed right now, and it makes you want to depend more on standards than specific rules. However, the problem with standards is that they can be avoided as well, by the sheer fact that they are always open to interpretation. Moreover, both of these approaches run the risk of being essentially too complicated for regulators to understand, but the standards one is particularly open to that.

If anyone has a third option that I haven’t thought of, please tell. Oh wait, someone suggested one to me: jailtime. This is actually a good point, and also possibly the best idea I’ve heard of to give some balls back to the SEC and other regulators: give them handcuffs and the authority to use them.

It occurs to me that the software testing community may have an answer, or at least an approach. It may make sense to set up a series of exhaustive tests which evaluates the resulting portfolio of the bank for certain characteristics which would indicate whether the bank has been following the standards appropriately.

To some extent this is being done, using various risk measures, for example looking at the volatility of the PnL to determine if someone is really market making or not. But I’m not sure the super nerds have thought about this onetoo much. I’d be interested to talk to anyone who knows.

Volcker Rule

There are two articles I wanted to bring up today. First, we have this Huffington Post article about the Volcker Rule commenting group Occupy the SEC, which has been meeting with us on Sundays and whom I’ve blogged about here and here. Some key quotes:

A handful of protesters at Occupy Wall Street are doing what the authors of a complex piece of financial legislation may have hoped no one would do. They are reading it.

…

The Occupy Wall Street movement, now in its third month, has drawn fire from people who say its members are too vague in their criticism of the financial system. Occupy the SEC, which consists of between four and eight New York protesters, would seem immune to such charges. Its members are compiling a list of highly specific points, and their ultimate goal is to submit a letter to regulators detailing their concerns before the Jan. 13 deadline.

Anyone can send in comments on the draft of the Volcker rule — and regulators will review those submissions before producing a final version of the measure — but, as in most cases where draft rules are made available for public scrutiny, not everyone has the time or inclination to parse hundreds of pages of regulatory jargon. Goldstein noted that most of the comments on financial rules end up coming from the banks themselves, arguing for greater leniency.

…

Paul Volcker himself has expressed displeasure with the current proposal, which is 30 times as long as the version originally included in Dodd-Frank.

Go team!

TBTF

Next, during the meeting yesterday where we were discussing Too Big to Fail (TBTF) and what can be done about it, Bloomberg published this article, which ranks among the best I’ve seen from them (up there with the Koch brothers article from a few weeks ago which I blogged about here).

The article describes the extent and amount of the secret Fed loans given to each bank for “liquidity” purposes during the credit crisis. Here’s a good quote:

While Fed officials say that almost all of the loans were repaid and there have been no losses, details suggest taxpayers paid a price beyond dollars as the secret funding helped preserve a broken status quo and enabled the biggest banks to grow even bigger.

Thank you! Why doesn’t everyone see that it makes no sense to say “we were paid back” when the underlying problem is still there (in fact worse) and we have given up our standards? On a related note:

The Fed didn’t tell anyone which banks were in trouble so deep they required a combined $1.2 trillion on Dec. 5, 2008, their single neediest day. Bankers didn’t mention that they took tens of billions of dollars in emergency loans at the same time they were assuring investors their firms were healthy. And no one calculated until now that banks reaped an estimated $13 billion of income by taking advantage of the Fed’s below-market rates, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its January issue.

Even if the $13 billion is arguable (I don’t have an opinion about that), I know it’s an underestimate because the alternative to this secret unlimited liquidity was bankruptcy, not less revenue.

The article brings up lots of interesting issues, beyond the asstons of cash money that were thrown at the banks during that time. Among them:

- To what extent would Congress have blocked TARP if they had know the size of the Fed program? Remember they actually voted TARP down before coming back and changing their mind after the stock market dropped by 10%. My favorite quote for this question comes from Sherrod Brown, a Democratic Senator from Ohio: “This is an issue that can unite the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street. There are lawmakers in both parties who would change their votes now.” I agree- this is a non-partisan issue.

- How much freaking power does the Fed have to do stuff behind closed doors? To what extent was this motivated by their feelings of shame that they’d let the housing bubble inflate for so long? Related quote from the article: “I believe that the Fed should have independence in conducting highly technical monetary policy, but when they are putting taxpayer resources at risk, we need transparency and accountability,” says Alabama Senator Richard Shelby, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee.

- Geithner seems to be against the idea of ending TBTF: “Geithner argued that the issue of limiting bank size was too complex for Congress and that people who know the markets should handle these decisions.” The article then goes on to say that Geithner suggested we just let the international economic community decide the new rules, i.e. Basel III. But as we know, that treaty has zero chance of being adopted by the U.S. at this point, so the end result is that Geithner put off the discussion by arguing that it would be dealt with internationally, but then it hasn’t been, at all. Moreover, the article mentions that the Dodd-Frank bill has a mechanism for closing down too-big-to-fail banks, decided by a committee of which Geithner is chair. I’m not holding my breath.

The most embarrassing part of the article is next, and deals again with the TBTF issue.

Lobbyists argued the virtues of bigger banks. They’re more stable, better able to serve large companies and more competitive internationally, and breaking them up would cost jobs and cause “long-term damage to the U.S. economy,” according to a Nov. 13, 2009, letter to members of Congress from the FSF. The group’s website cites Nobel Prize-winning economist Oliver E. Williamson, a professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, for demonstrating the greater efficiency of large companies.

In an interview, Williamson says that the organization took his research out of context and that efficiency is only one factor in deciding whether to preserve too-big-to-fail banks. “The banks that were too big got even bigger, and the problems that we had to begin with are magnified in the process,” Williamson says. “The big banks have incentives to take risks they wouldn’t take if they didn’t have government support. It’s a serious burden on the rest of the economy.”

Nice! Hey FSF, you may want to find a new quote! Oh wait, that link no longer works, interestingly…

I’m planning a follow-up blog post to discuss what our group decided to do with respect to TBTF. Hint: it has something to do with a Republican presidential candidate.

‘Move Your Money’ app (#OWS)

One of the most aggravating things about the credit crisis, and the (lack of) response to the credit crisis, is that the banks were found to be gambling with the money of normal people. They took outrageous risks, relying on the F.D.I.C. insurance of deposits. It is clearly not a good system and shouldn’t be allowed.

In fact, the Volcker Rule, part of the Dodd-Frank bill which is supposed to set in place new regulations and rules for the financial industry, is supposed to address this very issue, or risky trading on deposits. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the Volcker Rule itself goes far enough – or its implementation, which is another question altogether. I’ve posted about this recently, and I have serious concerns about whether the gambling will stop. I’m not holding my breath.

Instead of waiting around for the regulators to wade through the ridiculously complicated mess which is the financial system, there’s another approach that’s gaining traction, namely draining the resources of the big banks themselves by moving our money from big banks to credit unions.

I’ve got a few posts about credit unions from my guest poster FogOfWar. The basic selling points are as follows: credit unions are non-profit, they are owned by the depositors (and each person has an equal vote- it doesn’t depend on the size of your deposits), and their missions are to serve the communities in which they operate.

There are two pieces of bad news about credit unions. The first is that, because they don’t spend money on advertising and branches (which is a good thing- it means they aren’t slapping on fees to do so), they are sometimes less convenient in the sense of having a nearby ATM or doing online banking. However, this is somewhat alleviated by the fact that there are networks of credit union ATM’s (if you know where to look).

The second piece of bad news is that you can’t just walk into a credit union and sign up. You need to be eligible for that credit union, which is technically defined as being in its field of membership.

There are various ways to be eligible. The most common ones are:

- where you live (for example, the Lower East Side People’s Federal Credit Union allows people from the Lower East Side and Harlem into the field of membership)

- where you work

- where you worship or volunteer

- if you are a member of a union or various kinds of affiliated groups (like for example if you’re Polish)

This “field of membership” issue can be really confusing. The rules vary enormously by credit union, and since there are almost 100 credit unions in New York City alone, that’s a huge obstacle for someone to move their money. There’s no place where the rules are laid out efficiently right now (there are some websites where you can search for credit unions by your zipcode but they seem to just list nearby credit union regardless of whether you qualify for them; this doesn’t really solve the problem).

To address this, a few of us in the #OWS Alternative Banking group are getting together a team to form an app which will allow people to enter their information (address, workplace, etc.) and some filtering criteria (want an ATM within 5 blocks of home, for example) and get back:

- a list of credit unions for which the user is eligible and which fit the filtering criteria

- for each credit union, a map of its location as well as the associated ATM’s

- link to the website of the credit union

- information about the credit union: its history, its charter and mission, the products it offers, the fee structure, and its investing philosophy

It’s a really exciting project and we’ve got wonderful people working on it. Specifically, Elizabeth Friedrich, who has amazing knowledge about credit unions inside New York City (our plan is to start withing NYC but then scale up once we’ve got a good interface to add new credit unions), Robyn Caplan, who is a database expert and has worked on similar kinds of matching problems before, and Dahlia Bock, a developer from ThoughtWorks, a development consulting company which regularly sponsors social justice projects.

The end goal is to have an app, which is usable on any phone or any browser (this is an idea modeled after thebostonglobe.com’s new look- it automatically adjusts the view depending on the size of your browser’s window) and which someone can use while they watch the Daily Show with Jon Stewart. In fact I’m hoping that once the app is ready to go, we go on the Daily Show and get Jon Stewart to sign up for a credit union on the show just to show people how easy it is.

We’re looking to recruit more developers to this project, which will probably be built in Ruby on Rails. It’s not an easy task: for example, the eligibility by location logic, for which we will probably use google maps, isn’t as easy as zipcodes. We will need to implement some more complicated logic, perhaps with an interface which allows people to choose specific streets and addresses. We are planning to keep this open source.

If you’re a Rails developer interested in helping, please send me your information by commenting below (I get to review comments before letting them be viewed publicly, so if you want to help, tell me and won’t ever make it a publicly viewable comment, I’ll just write back to your directly). And please tell your socially conscious nerd friends!

What’s the Volcker Rule?

I wrote recently about the #OWS Alternative Banking working group preparing public comments on the Volcker Rule. I wanted to give a little bit more context. This is especially important right now because the watering-down period by financial lobbyists is getting intense.

The original Volcker Rule essentially states that banks shouldn’t do proprietary trading at all and they should also not invest in hedge funds or provate equity funds or in any way be liable for losses on such funds.

The idea is that the government and thus the taxpayer is backing (through the FDIC) the money inside banks and those banks shouldn’t use that insurance while at the same time risking the deposits themselves just to make a quick buck. To actually see this law, see Section 619 in the Dodd-Frank act. The law itself is only 11 pages, and some of that is around timing of implementation, so it’s a quick read.

Again, this 11-page document states what the Volcker Rule is supposed to implement. It summarizes the high-level thinking behind the rule. More importantly, the regulators’ mandate is to write a detailed rule that complies with what’s written in the law. When they ask for comments on the rule, they’re asking how well the rule implements the law.

This sounds pretty clean cut, but of course there are grey areas: for example, the law states that if banks fail to comply with the no-prop trading or hedge fund investing rules, then they’ll get punished by having higher capital requirements as well as fines. But it fails to say how stringent those punishments will be. So one way to technically implement the law is to make the punishment trivial.

The law also claims that the banks should be allowed to trade outside their clients’ direct interests in the name of hedging risks. The granularity of that allowed “hedging” is critical, since if they are hedging at the trade level, that’s very different from hedging at the macro level. The best example I’ve heard of this is that the bank may decide there’s “inflation risk” in their portfolio and start investing in long-term inflation hedges; then this really becomes more of a bet than a hedge but it depends on how you look at it and more importantly how one defines the word hedge.

To a large extent I feel like this could be resolved if we force a short-term horizon on the hedging basis. In other words, it’s a hedge if you can argue that you bought a bunch of 1-month puts so you need to hedge your risk on that one month period. However, a 5-year inflation outlook is clearly more of an opinion. On the other hand, forcing banks, as a group, to think in short horizons has its own dangers.

The law also states that banks are allowed to invest in certain U.S.-backed agencies:

PERMITTED ACTIVITIES… The purchase, sale, acquisition, or disposition of obligations of the United States or any agency thereof, obligations, participations, or other instruments of or issued by the Government National Mortgage Association, the Federal National Mortgage Association, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, a Federal Home Loan Bank, the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation, or a Farm Credit System institution chartered under and subject to the provisions of the Farm Credit Act of 1971 (12 U.S.C. 2001 et seq.), and obligations of any State or of any political subdivision thereof.

There are those who claim that we need to expand the above rule for the sake of national security and to prevent a deep, world-wide depression. Specifically, in this article in the Financial Times, the lobbyists are working hard to allow prop trading in European bonds, a huge market which is currently stipulated to be out of bounds:

They point out that Dodd-Frank exempts US sovereign bonds from the general prop trading ban for fear of disruptions. “What happens if you remove the US banks from Europe and they dump the stuff? Prices could collapse,” said Doug Landy, a regulatory lawyer at Allen & Overy.

There are lots of other permitted activities that don’t necessarily make sense to the historian of how other firms have gotten themselves into trouble: interest rate swaps (which are surely necessary tools for hedging basic bank hedging but it doesn’t seem to be restricted to hedging), spot commodities, foreign currency, and all kinds of loans (including repos). There are plenty of ways for banks to put deposits at risk within these instrument classes.

My conclusion is that, when the Alternative Banking group sends feedback to the regulators, we should separate comments on the implementation of the rule (e.g., what risk measures should be used and in how much detail they should be specified) from comments on the underlying law (e.g., whether this is actually preventing conflicts of interest).

The regulators are supposed to fix problems with the rule, but they can’t fix problems with the law (it takes an act of Congress to fix those). To the extent that we have problems with what’s in the law itself, it is worth a separate discussion about what the best way is to get those addressed.

What does “too big to fail” mean?

The Alternative Banking meeting yesterday was really good, and interesting. During the discussion someone raised the point that when we describe a bank as “too big to fail,” we almost always measure that in terms of their assets under management, or the percent of deposits they have, or their net or gross exposures. In other words, we measure the size of the individual institution.

However, what’s just as important in terms of being “too big” is the extent to which a given bank is too interconnected, meaning they are in deals with so many other counterparties that if they go under, they would set off a cascade of contractual defaults which would cause chaos in the entire system. In fact Lehman was like this, too interconnected to fail. It’s funny but I’m pretty sure Lehman wasn’t too big to fail under many of the current definitions.

Although this question of counterparty risk is brought up consistently, it’s never adequately addressed in terms of risk; we are still more or less asking people to measure the volatility of their PnL, and we typically don’t force them to expose their counterparty exposure in stress tests and whatnot.

What if we addressed this directly? How could we regulate the interconnectedness of a given institution? What would be the metric in the first place and what limits could we set? How could we set up a regulator to convincingly check that institutions are sticking to their interconnectedness quotas?

I’ll keep thinking about this, they are not easy questions. But I think they are important ones, because they get to the heart of the current problems more than most.

A further question brought up yesterday was, how do we know when the entire financial system is too big? I guess we don’t need any fancy metrics to say that for now we just know.

Occupy the SEC: commenting on the Volcker Rule

One of the subgroups of the Alternative Banking group is an #OWS group called Occupy the SEC. Their goal is to make comments on the Volcker Rule before the public commenting period ends on January 13th, 2012.

At our last meeting we distributed a sheet where people put their email addresses and listed fields of expertise so that the people in Occupy the SEC could ask us specific clarifying questions about what the current version of the Volcker Rule says.

If you think you could have time to help them, please email them at occupythesec@gmail.com and tell them what your fields of expertise are. They are mostly looking for financial expertise and people who speak legalese, but anyone who is a good and careful reader will be super useful too.

My experience at Riskmetrics working with Value-at-Risk (VaR), where I was actually working on methodology questions of VaR usage for credit instruments like CDS, makes me pretty useful to these guys.

This morning I’ve been reading about the proposed risk reporting requirements for the “covered bank entity”. Basically they are required to report daily 99th percentile VaR. But left out are all other details, including:

- whether they should use parametric, historical, or MonteCarlo VaR methods,

- what their lookback period is (if historical)

- what their decay length is (if MonteCarlo)

- what exactly they need to admit as risk factors

- why they would ever use parametric VaR outside of stocks, since parametric VaR sucks outside of stocks.

They are also asked to report the skew and kurtosis of their daily PnL, but I believe are only required to report this for daily numbers on a quarterly basis, which means there’s no chance in hell those will be meaningful numbers.

How about this instead: report all three kinds of VaR, with a year lookback for historical VaR, and with various decay lengths for MonteCarlo VaR. Specify the risk factors and ask for each risk factor’s sensitivity (which is like a partial derivative if we are using parametric VaR) as well as min and max returns (if we are using historical VaR). Report skew and kurtosis using daily numbers with 2 years of data.

Even better if they abandon this altogether and go for something benchmarked as I discussed in this post.

There seems to be no stipulated need to report counter-party exposure or risk, at least in this section (Appendix A). This seems particularly egregious considering the current situation, namely that we are waiting for European sovereign debt defaults to cause broken CDS hedges through collapsing counterparties. We know this would happen, but we somehow don’t want to know more details.

This is only a few pages of the Volcker Rule, though, out of I think something like 550. We need your help for sure!

Postage paid protest

I’m glad I got a new laptop with sound, because now I can listen to and watch this awesome YouTube video with suggestions to keep Wall Street occupied.

The sin of debt

It’s fascinated me for a while how people use language to indicated the relationship between money and morality. David Graeber’s book about debt took this issue on directly, but even before reading it I had noticed the disconnect between individual debt and corporate debt.

It was clear from my experience in finance that debt is something that, at the corporate level, is considered important – you are foolish not to be in debt, because it means you’re not taking advantage of the growth opportunities that the business climate affords you. In fact you should maximize your debt within “reasonable” estimates of its risk. Notable this is called leveraging your equity, a term which if anything sounds like a power move.

That just describes the taking on of debt, which for an individual is something they are likely not going to describe with such bravado, since they’d be forced to use measly terms such as “I got a loan”. What about when you’re in trouble with too much debt?

My favorite term is debt restructuring, used exclusively at the corporate (or governmental) level. It makes defaulting on ones debt a business decision by a struggling airline or what have you, and the underlying tone is sympathy, because don’t we want our airlines (or other american companies) to succeed?

When you compare this language and its implied morality (neutral) to the moralistic preaching of late-night talk radio, it’s quite stark. It’s made clear on such shows that debt is a sin, that the reason the show is a success is that it’s entertainment to hear how messed up the callers’ finances are, and to hear the radio host drill into their most private details in the name of ferreting out that sin.

The Suzy Ormon show is another example of this, and this blog entry is a great description of the emotional and spiritual repentance required in our culture when one is in debt, bizarrely combined with her urging you to go out and consume some more.

For the individual there is no debt restructuring available – at best you can get your debt consolidated, but the people who do that are themselves considered icky. There’s no clean way to deal with out-of-control debt as an individual.

Until now! I found an interesting article the other day which somehow excludes certain people from the moral failing of being in debt – namely, if they have the help of another powerful buzzword – a moral reclamation if you will – namely, “entrepreneur.” Because we all want our entrepreneurs to succeed!

The fact that the program doesn’t apply to most of a typical person’s student debt load is only partly relevant – for me, the fascinating part is the way that, when you stick in the word “entrepreneur,” you suddenly have the vision of someone who shouldn’t be saddled with debt, who is immediately forgiven for their sins. It brings up the question, can we perform this moral cleansing for other groups of people who are currently in debt?

What if we coopted the language of the corporations for the individual? I’d love to hear people talking about large-scale restructuring of their debt. Just the phrase makes me realize its possibilities. One of the main tools of leverage for such talks is the amount of money on the table. If sufficiently many people got together to formally restructure their credit card debts, what would the banks do? What could they do except negotiate?

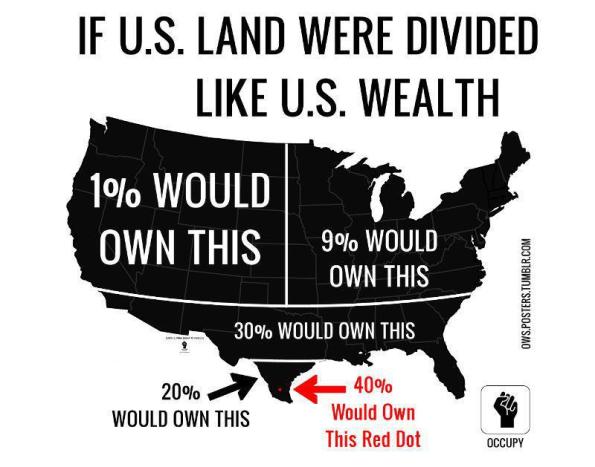

Here’s a graphic I like just in case you haven’t seen it yet:

Gaming the system

It’s not easy being a European bank right now. Everyone is telling them to boost capital, otherwise known as raise money, exactly at the time that much of their investments are losing value on the market because of the European debt crisis.

If I were the person running such a bank, I’d be looking at fewer and fewer options. Among them:

- Ask China for some of their money

- Ask investors for some of their money

- Ask a middle eastern country for some of their money

- Cut bonuses or dividends

- Change the way I measure my money

Of the above possibilities, 5) is kind of attractive in a weird way.

And guess what? That’s exactly the option that the banks are choosing. According to this article from Bloomberg, the banks have suddenly noticed they have way more assets than they previously realized:

Spanish banks aren’t alone in using the practice. Unione di Banche Italiane SCPA (UBI), Italy’s fourth-biggest bank, said it will change its risk-weighting model instead of turning to investors for the 1.5 billion euros regulators say it needs. Commerzbank AG (CBK), Germany’s second-biggest lender, said it will do the same. Lloyds Banking Group Plc (LLOY), Britain’s biggest mortgage lender, and HSBC Holdings Plc (HSBA), Europe’s largest bank, both said they cut risk-weighted assets by changing the model.

“It’s probably not the highest-quality way to move to the 9 percent ratio,” said Neil Smith, a bank analyst at West LB in Dusseldorf, Germany. “Maybe a more convincing way would be to use the same models and reduce the risk of your assets.”

Ya THINK?!

European firms, governed by Basel II rules, use their own models to decide how much capital to hold based on an assessment of how likely assets are to default and the riskiness of counterparties. The riskier the asset, the heavier weighting it is assigned and the more capital a bank is required to allocate. The weighting affects the profitability of trading and investing in those assets for the bank.

One reason I couldn’t stomach any more time at the risk company I worked at is things like this. We would spend week after week setting up risk models for our clients, accepting whatever they wanted to do, because they were the client and we were working for them. Our application was flexible enough to allow them to try out lots of different things, too, so they could game the system pretty efficiently. Moreover, this idea of the “riskiness of counterparties” is misleading- I don’t think there is an actual model out there that is in use and is useful to broadly understand and incorporate counterparty risk (setting aside the question for now of gaming such a model).

For example, the amount of risk taken on by CDS contracts in a portfolio was essentially assumed to be zero, since, as long as they hadn’t written such contracts, they were only on the hook for the quarterly payments. However, as we know from the AIG experience, the real risk for such contracts is that they won’t pay out because the writers will have gone bankrupt. This is never taken into account as far as I know- the CDS contracts are allowed for hedging and never impose risk on the overall portfolio otherwise. If the entity in question is the writer of the CDS, the risk is also viciously underestimated, but for a slightly more subtle reason, which is that defaults are generally hard to predict.

Here’s not such a crappy idea coming from Vikram Pandit (it’s in fact a pretty good idea but doesn’t go far enough). Namely, standardize the risk models among banks by forcing them to assess risk on some benchmark portfolio that nobody owns, that’s an ideal portfolio, but that thereby exposes the banks’ risk models:

Pandit is championing an idea to make it easier to compare the way banks assess risk. To accomplish this, he wants to start with a standard, hypothetical portfolio of assets agreed by regulators the world over. Each financial institution would run this benchmark collection through its risk models and spit out four numbers: loan loss reserve requirements, value-at-risk, stress test results and the tally of risk-weighted assets. The findings would be made public.

Then, Pandit wants the same financial firms to run the same measures against their own balance sheets – and to publish those results, too. That way, not only can investors and regulators compare similar risk outputs across institutions for their actual portfolios, but the numbers for the benchmark portfolio would allow them to see how aggressively different firms test for risks.

I think we should do this, because it separates two issues which banks love to conflate: the issue of exposing their risk methodology (which they claim they are okay with) and the idea of exposing their portfolios (which they avoid because they don’t want people to read into their brilliant trading strategies). I don’t see this happening, although it should- in fact we should be able to see this on a series of “hypothetical” portfolios, and the updates should be daily.

As a consumer learning about yet more bank shenanigans, I am inspired to listen to George Washington:

Why I’m involved with #Occupy Wall Street

I get a lot of different responses when I tell people I’m heavily involved with the Alternative Banking group at #OWS. I find myself explaining, time after time, why it is I am doing this, even though I have a full-time job and three children (let’s just say that my once active knitting circle hasn’t met in a while).

I was not particularly activist before this. In fact I went to UC Berkeley for college and managed to never become politically involved, except for two anti-Gulf war protests in San Francisco which were practically required. While my best friend Becky was painting banners in protest of the U.S. involvement in El Salvador, I was studying tensor products and class field theory.

It’s true that I’ve been much more involved in food-based charities like Fair Foods since high school. One of the most attractive things about Fair Foods was that it acts as an outsider to the system, creating a network of gifts (of primarily food and lumber) which was on the one hand refreshingly generous, based on trust, and the other hand small enough to understand and affect personally.

I, like many people, figured that the political system was too big to affect. After all, it was enormous, did lots of very reasonable things and some unreasonable things; it didn’t solve every problem like hunger and crime, but the people running it were presumably doing their best with incomplete information. Even if those people didn’t know what they were doing, I didn’t know how to change the system. In short, I wasn’t an expert myself, so I deferred to the experts.

Same goes with the economic system. I assumed that the people in charge knew what they were doing when they set it up. I was so trusting, in fact, that I left my academic job and went to work at a hedge fund to “be in business”. I had essentially no moral judgement one way or the other about the financial system.