Archive

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia has two wee bits of bad news.

First, nobody helped out NYC and Wondering from last week looking to get educated via internships past college age. Maybe if the question were worded differently it would have gotten more responses.

In the meantime, NYC and Wondering, I’d suggest you look into MOOCs on Coursera, Udacity, and the like. There are Meetup groups you can join once you’re in a course like this one.

Second, Aunt Pythia has been informed that some people are getting error messages when they try to submit questions. That’s no good! If that’s happening to you, please comment below using the phrase, “question for Aunt Pythia” and it will automatically go into my mailbox instead of getting posted.

On to this week’s questions:

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am suffering from severe Facebook phobia. Is the entire phenomenon as repulsive as I think it is?

Curmudgeon Lee Luddite

Dear Curmudgeon LL,

Here’s the thing. I am totally grossed out by Facebook on so many levels. As a concerned data scientist, the shit they pull with respect to personal information, letting other people post private information about you, and selling your data makes me really uneasy. Read this recent article about the Facebook Doctrine (“What’s good for Facebook is good for you”) if you want to hear more. Mind you, that Doctrine seems to be pretty clear-cut if you modify it just a bit: “What’s good for Facebook is good for the stock price of Facebook”: the market loves the trend of information selling because it’s magnificently profitable.

Another thing that pisses me off, which I learned about in the student presentations last week at the Columbia Data Science class I was blogging: people are posting various legalese-sounding letters to Facebook on their timeline which tells Facebook to keep their hands off their personal data. Guess what, kids, it’s too late, you signed away your rights when you entered, and such crap only serves as yet another illusion of control (along with the Facebook privacy settings).

Having said all that, I use Facebook myself – but of course I never post anything remotely private on it. But for that matter I also use Google+, and I’m ready and willing to use another platform when one comes along that’s less creepy.

Curmudgeon, to answer your question, yes it’s just as repulsive as you think. I fully defend your disgust, and if anyone questions it just send that person to me, I’ll set them straight.

Best,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Should I go to the Joint Math Meetings if I’m thinking of leaving academia realllly soon?

Katydid

Dear Katydid,

It depends. Is it tough for you to go? Would you miss job opportunities by doing so? I’m assuming you are planning to leave academia but you haven’t actually gotten another job.

If the answer is that it’s relatively easy to go and that you don’t have any other plans that weekend, then by all means you should go. And you should make a plan beforehand on what information you can gather about jobs that math people do.

For example, make sure you have a good idea of what kind of jobs in academia there really are, by interviewing a bunch of people about what they do on a daily basis. But keep in mind that most of them will be drunk because it’s the Joint Math Meetings and that’s kind of the point. And also keep in mind you’re hearing much more about academia than about industry since you’re at this meeting.

But that doesn’t mean you’ll be stuck only hearing about academia! Because I’ll be there, talking about the world outside academic math, and so will a few other people. I am particularly psyched that I’ll be speaking on the first day so I can meet people after my talk and hang out with them for the next few days, getting drunk and playing bridge. It’s very serious business, of course.

See you soon I hope!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Is health insurance a sound financial investment?

Uninsured

Dear Uninsured,

Great question. It’s not really an investment, and it’s only a good idea once in a while; the problem is knowing in advance when it’s a good idea.

I say it’s not an investment because usually with an investment you can expect to make money, whereas insurance is never like that. Once you pay insurance premiums that money is gone.

Insurance can, however, be seen as a financial bet: you’re betting that losing a predictable and smallish amount of money is less painful than the overall risk of losing an unpredictable and large amount of money if you get horribly sick and need major treatment.

There are plenty of problems with this explanation though, including:

- it’s not so smallish if you don’t have work or if you have crappy work through a place like Walmart,

- you personally might be very healthy and the risk of getting super sick might not be high, say if you’re 24 and fit; this means that your money may be better spent buying high quality food than paying for health insurance, and

- the large amount of money you may get billed with if you do end up horribly sick can be discharged through bankruptcy, and in fact most of the bankruptcy proceedings happen because of medical debt of uninsured people. Keep in mind you will lose your house (if you have one) if you go this route, so only consider it if you’re willing to take that risk.

In the end it depends on your situation whether it’s worth it to buy health insurance.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

Why do some foods burn when you stir them? It doesn’t make sense that my rice or pasta should burn when there is still a lot of water in the pot just because I stirred it.

Physics-Inclined Wannabe Chef

This is a great question! Is it even true? Does it also happen with orzo? People, get out your pots and do some mythbuster-type experiments! And then comment below with your ideas and results.

I’m counting on you nerdy folks to get to the bottom of this, so to speak.

——

In the meantime, if you have a moral, personal, or emotional dilemma or somesuch, please share avec moi below on my gorgeous new form:

MOOCs and calculus

I’ve really enjoyed the discussion on my post from yesterday about MOOCs and how I predict they are going to affect the education world. I could be wrong, of course, but I think this stuff is super interesting to think about.

One thing I thought about since writing the post yesterday, in terms of math departments, is that I used to urge people involved in math departments to be attentive to their calculus teaching.

The threat, as I saw it then, was this: if math departments are passive and boring and non-reactive about how they teach calculus, then other departments which need calculus for their majors would pick up the slack and we’d see calculus taught in economics, physics, and engineering departments.

The reason math departments should care about this is that calculus is the bread and butter of math departments – math departments in other countries who have lost calculus to other departments are very small. If you only need to teach math majors, it doesn’t require that many people to do that.

But now I don’t even bother saying this, because the threat from MOOCs is much bigger and is going to have a more profound effect, and moreover there’s nothing math departments can do to stop it. Well, they can bury their head in the sand but I don’t recommend it.

Once there’s a really good calculus sequence out there, why would departments continue to teach the old fashioned way? Once there’s a fantastic calculus-for-physics MOOC, or calculus-for-economics MOOC available, one would hope that math departments would admit they can’t do better.

Instead of the old-fashioned calculus approach they’d figure out a way to incorporate the MOOC and supplement it by forming study groups and leading sections on the material. This would require a totally different set-up, and probably fewer mathematicians.

Another thing. I think I’ve identified a few separate issues in the discussion that it makes sense to highlight. There are four things (at least) that are all rolled together in our current college and university experience:

- learning itself,

- credentialing,

- research, and

- socializing

So, MOOCs directly address learning but clearly want to control something about credentialing too, which I think won’t necessarily work. They also affect research because the role of professor as learning instructor will change. They give us nothing in terms of socializing.

But as commenters have pointed out, socializing students is a huge part of the college experience, and may be even more important than credentialing. Or another way of saying that is people look at your resume not so much to know what you know but to know how you’ve been socialized.

It makes me wonder how we will address the “socializing” part of education in the future. And it also makes me wonder where research will be in 100 years.

MOOC is here to stay, professors will have to find another job

I find myself every other day in a conversation with people about the massive online open course (MOOC) movement.

People often want to complain about the quality of this education substitute. They say that students won’t get the one-on-one interaction between the professor and student that is required to really learn. They complain that we won’t know if someone really knows something if they only took a MOOC or two.

First of all, this isn’t going away, nor should it: it’s many people’s only opportunity to learn this stuff. It’s not like MIT has plans to open 4,000 campuses across the world. It’s really awesome that rural villagers (with internet access) all over the world can now take MIT classes anyway through edX.

Second, if we’re going to put this new kind of education under the microscope, let’s put the current system under the microscope too. Many of the people fretting about the quality of MOOC education are themselves products of super elite universities, and probably don’t know what the average student’s experience actually is. Turns out not everyone gets a whole lot of attention from their professors.

Even at elite institutions, there are plenty of masters programs which are treated as money machines for the university and where the quality and attention of the teaching is a secondary concern. If certain students decide to forgo the thousands of dollars and learn the stuff just as well online, then that would be a good thing (for them at least).

Some things I think are inevitable:

- Educational institutions will increasingly need to show they add value beyond free MOOC experiences. This will be an enormous market force for all but the most elite universities.

- Instead of seeing where you went to school, potential employers will directly test knowledge of candidates. This will mean weird things like you never actually have to learn a foreign language or study Shakespeare to get a job, but it will be good for the democratization of education in general.

- Professors will become increasingly scarce as the role of the professor is decreased.

- One-on-one time with masters of a subject will become increasingly rare and expensive. Only truly elite students will have the mythological education experience.

When accurate modeling is not good

I liked Andrew Gelman’s recent post (hat tip Suresh Naidu) about predatory modeling going on in casinos, specifically Caesars in Iowa. The title of the post is already good, and is a riff on Caesars Entertainment CEO Gary Loveman said:

There are four ways to get fired from Caesars: (1) theft, (2) sexual harassment, (3) running an experiment without a control group, and (4) keeping a gambling addict away from the casino

He tells a story about a woman who loses lots of money at the casino, but who moreover gets manipulated to come back and lose more and more based on the data the people collected at Caesars and based on the models built by the quants there. You should read the whole thing, which as usual with Gelman is quirky and fun. His main point comes here (emphasis mine):

The Caesars case (I keep wanting to write Caesar’s but apparently no, it’s Caesars, just like Starbucks) interested me because of the role of statistics. I’m used to thinking of probability and statistics as a positive social force (helping medical research or, in earlier days, helping the allies in World War 2), or mildly positive (for example, helping design measures to better evaluate employees), or maybe neutral (exotic financial instruments which serve no redeeming social value but presumably don’t do much harm) or moderately negative (“Moneyball”-style strategies such as going for slow sluggers who foul off endless pitches and walk a lot; it may win games but it makes for boring baseball). And then there are statisticians who do fishy analyses, for example trying to hide that some drug causes damage so it can stay on the market. But that’s a bit different because such a statistical analysis, no matter how crafty, is inherently a bad analysis, trying to obscure rather than learn.

The Caesars case seems different, in that there is a very direct tradeoff: the better the statistics and the better the science, the worse the human outcomes. These guys are directly optimizing their ability to ruin some people’s lives.

It’s not the only one, but they are not usually this clear-cut.

It’s time we started scoring models on various dimensions. Accuracy is one, predatoriness is another. They’re distinct.

Fighting the information war (but only on behalf of rich people)

There’s an information war out there which we have to be prepared for. Actually there a few of them.

And according to this New York Times piece, there’s now a way to fight against the machine, for a fee. Companies like Reputation.com will try to scour the web and remove data you don’t want floating around about you, and when that’s impossible they’ll flood the web with other good data to balance out the bad stuff.

At least that’s what I’m assuming they do, because they of course don’t really explain their techniques. And that’s the other information war, where they scare rich people with technical sounding jargon and tell them unlikely stories to get their money.

I’m not claiming predatory information-gatherers aren’t out there. But this is the wrong way to deal with it.

First of all, most of the data out there systematically being used for nefarious purposes, at least in this country, is used against the poor, denying them reasonable terms on their loans and other services. So the idea that people will need to pay for a service to protect their information is weird. It’s like saying the air quality is bad for poor people, so let’s charge rich people for better air.

So what kind of help is Reputation.com actually providing? Here’s my best guess.

First it targets people to get overly scared in the spirit of this recent BusinessWeek article, which explains that cosmetic companies have gone to China and started a campaign to convince Chinese women they are too hairy so they’ll start buying products to remove hair. From that article, which is guaranteed to make you understand something about American beauty culture too:

Despite such plays on women’s fears of embarrassment, Reckitt Benckiser’s Sehgal says that Chinese women are too “independent-minded” to be coaxed into using a product they don’t really need. Others aren’t so sure. Veet’s Chinese marketing “plays a role that is very similar to that of the apple in the Bible,” says Benjamin Voyer, a social psychologist and assistant professor of marketing at ESCP Europe business school. “It creates an awareness, which subsequently creates a feeling of shame and need.”

Second, Reputation.com gets their clients off nuisance lists, like the modern version of a do-not-call program (which, importantly, is run by the government). This is probably equivalent to setting up a bunch of email filters and clearing their cookies every now and then, but they can’t tell their clients that.

Finally, for those rich people who are also super vain, they will try to do things like replace the unflattering photos of them that come up in a google image search with better-looking ones they choose. Things like that, image issues.

I just want to point out one more salient fact about Reputation.com. It’s not just in their interest to scare-monger, it’s actually in their interest to make the data warehouses more complete (they have themselves amassed an enormous database on people), and to have people who don’t pay for their services actually need their services more. They could well create a problem to produce a market for their product.

What drives me nuts about this is how elitist it is.

There are very real problems in the information-gathering space, and we need to address them, but one of the most important issues is that the very people who can’t afford to pay for their reputation to be kept clean are the real victims of the system.

There is literally nobody who will make good money off of actually solving this problem: I challenge any libertarian to explain how the free market will address this. It has to be addressed through policy, and specifically through legislating what can and cannot be done with personal data.

Probably the worst part is that, through using the services from companies Reputation.com and because of the nature of the personalization of internet usage, the very legislators who need to act on behalf of their most vulnerable citizens won’t even see the problem since they don’t share it.

Columbia Data Science course, week 14: Presentations

In the final week of Rachel Schutt’s Columbia Data Science course we heard from two groups of students as well as from Rachel herself.

Data Science; class consciousness

The first team of presenters consisted of Yegor, Eurry, and Adam. Many others whose names I didn’t write down contributed to the research, visualization, and writing.

First they showed us the very cool graphic explaining how self-reported skills vary by discipline. The data they used came from the class itself, which did this exercise on the first day:

so the star in the middle is the average for the whole class, and each star along the side corresponds to the average (self-reported) skills of people within a specific discipline. The dotted lines on the outside stars shows the “average” star, so it’s easier to see how things vary per discipline compared to the average.

Surprises: Business people seem to think they’re really great at everything except communication. Journalists are better at data wrangling than engineers.

We will get back to the accuracy of self-reported skills later.

We were asked, do you see your reflection in your star?

Also, take a look at the different stars. How would you use them to build a data science team? Would you want people who are good at different skills? Is it enough to have all the skills covered? Are there complementary skills? Are the skills additive, or do you need overlapping skills among team members?

Thought Experiment

If all data which had ever been collected were freely available to everyone, would we be better off?

Some ideas were offered:

- all nude photos are included. [Mathbabe interjects: it’s possible to not let people take nude pics of you. Just sayin’.]

- so are passwords, credit scores, etc.

- how do we make secure transactions between a person and her bank considering this?

- what does it mean to be “freely available” anyway?

The data of power; the power of data

You see a lot of people posting crap like this on Facebook:

But here’s the thing: the Berner Convention doesn’t exist. People are posting this to their walls because they care about their privacy. People think they can exercise control over their data but they can’t. Stuff like this give one a false sense of security.

In Europe the privacy laws are stricter, and you can request data from Irish Facebook and they’re supposed to do it, but it’s still not easy to successfully do.

And it’s not just data that’s being collected about you – it’s data you’re collecting. As scientists we have to be careful about what we create, and take responsibility for our creations.

As Francois Rabelais said,

Wisdom entereth not into a malicious mind, and science without conscience is but the ruin of the soul.

Or as Emily Bell from Columbia said,

Every algorithm is editorial.

We can’t be evil during the day and take it back at hackathons at night. Just as journalists need to be aware that the way they report stories has consequences, so do data scientists. As a data scientist one has impact on people’s lives and how they think.

Here are some takeaways from the course:

- We’ve gained significant powers in this course.

- In the future we may have the opportunity to do more.

- With data power comes data responsibility.

Who does data science empower?

The second presentation was given by Jed and Mike. Again, they had a bunch of people on their team helping out.

Thought experiment

Let’s start with a quote:

“Anything which uses science as part of its name isn’t political science, creation science, computer science.”

– Hal Abelson, MIT CS prof

Keeping this in mind, if you could re-label data science, would you? What would you call it?

Some comments from the audience:

- Let’s call it “modellurgy,” the craft of beating mathematical models into shape instead of metal

- Let’s call it “statistics”

Does it really matter what data science is? What should it end up being?

Chris Wiggins from Columbia contends there are two main views of what data science should end up being. The first stems from John Tukey, inventor of the fast fourier transform and the box plot, and father of exploratory data analysis. Tukey advocated for a style of research he called “data analysis”, emphasizing the primacy of data and therefore computation, which he saw as part of statistics. His descriptions of data analysis, which he saw as part of doing statistics, are very similar to what people call data science today.

The other prespective comes from Jim Gray, Computer Scientist from Microsoft. He saw the scientific ideals of the enlightenment age as expanding and evolving. We’ve gone from the theories of Darwin and Newton to experimental and computational approaches of Turing. Now we have a new science, a data-driven paradigm. It’s actually the fourth paradigm of all the sciences, the first three being experimental, theoretical, and computational. See more about this here.

Wait, can data science be both?

Note it’s difficult to stick Computer Science and Data Science on this line.

Statistics is a tool that everyone uses. Data science also could be seen that way, as a tool rather than a science.

Who does data science?

Here’s a graphic showing the make-up of Kaggle competitors. Teams of students collaborated to collect, wrangle, analyze and visualize this data:

The size of the blocks correspond to how many people in active competitions have an education background in a given field. We see that almost a quarter of competitors are computer scientists. The shading corresponds to how often they compete. So we see the business finance people do more competitions on average than the computer science people.

Consider this: the only people doing math competitions are math people. If you think about it, it’s kind of amazing how many different backgrounds are represented above.

We got some cool graphics created by the students who collaborated to get the data, process it, visualize it and so on.

Which universities offer courses on Data Science?

There will be 26 universities in total by 2013 that offer data science courses. The balls are centered at the center of gravity of a given state, and the balls are bigger if there are more in that state.

Where are data science jobs available?

Observations:

- We see more professional schools offering data science courses on the west coast.

- It would also would be interesting to see this corrected for population size.

- Only two states had no jobs.

- Massachusetts #1 per capita, then Maryland

Crossroads

McKinsey says there will be hundreds of thousands of data science jobs in the next few years. There’s a massive demand in any case. Some of us will be part of that. It’s up to us to make sure what we’re doing is really data science, rather than validating previously held beliefs.

We need to advance human knowledge if we want to take the word “scientist” seriously.

How did this class empower you?

You are one of the first people to take a data science class. There’s something powerful there.

Thank you Rachel!

Last Day of Columbia Data Science Class, What just happened? from Rachel’s perspective

Recall the stated goals of this class were:

- learn about what it’s like to be a data scientists

- be able to do some of what a data scientist does

Hey we did this! Think of all the guest lectures; they taught you a lot of what it’s like to be a data scientist, which was goal 1. Here’s what I wanted you guys to learn before the class started based on what a data scientist does, and you’ve learned a lot of that, which was goal 2:

Mission accomplished! Mission accomplished?

Thought experiment that I gave to myself last Spring

How would you design a data science class?

Comments I made to myself:

- It’s not a well-defined body of knowledge, subject, no textbook!

- It’s popularized and celebrated in the press and media, but there’s no “authority” to push back

- I’m intellectually disturbed by idea of teaching a course when the body of knowledge is ill-defined

- I didn’t know who would show up, and what their backgrounds and motivations would be

- Could it become redundant with a machine learning class?

My process

I asked questions of myself and from other people. I gathered information, and endured existential angst about data science not being a “real thing.” I needed to give it structure.

Then I started to think about it this way: while I recognize that data science has the potential to be a deep research area, it’s not there yet, and in order to actually design a class, let’s take a pragmatic approach: Recognize that data science exists. After all, there are jobs out there. I want to help students to be qualified for them. So let me teach them what it takes to get those jobs. That’s how I decided to approach it.

In other words, from this perspective, data science is what data scientists do. So it’s back to the list of what data scientists do. I needed to find structure on top of that, so the structure I used as a starting point were the data scientist profiles.

Data scientist profiles

This was a way to think about your strengths and weaknesses, as well as a link between speakers. Note it’s easy to focus on “technical skills,” but it can also be problematic in being too skills-based, as well as being problematic because it has no scale, and no notion of expertise. On the other hand it’s good in that it allows for and captures variability among data scientists.

I assigned weekly guest speakers topics related to their strengths. We held lectures, labs, and (optional) problem sessions. From this you got mad skillz:

- programming in R

- some python

- you learned some best practices about coding

From the perspective of machine learning,

- you know a bunch of algorithms like linear regression, logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors, k-mean, naive Bayes, random forests,

- you know what they are, what they’re used for, and how to implement them

- you learned machine learning concepts like training sets, test sets, over-fitting, bias-variance tradeoff, evaluation metrics, feature selection, supervised vs. unsupervised learning

- you learned about recommendation systems

- you’ve entered a Kaggle competition

Importantly, you now know that if there is an algorithm and model that you don’t know, you can (and will) look it up and figure it out. I’m pretty sure you’ve all improved relative to how you started.

You’ve learned some data viz by taking flowing data tutorials.

You’ve learned statistical inference, because we discussed

- observational studies,

- causal inference, and

- experimental design.

- We also learned some maximum likelihood topics, but I’d urge you to take more stats classes.

In the realm of data engineering,

- we showed you map reduce and hadoop

- we worked with 30 separate shards

- we used an api to get data

- we spent time cleaning data

- we’ve processed different kinds of data

As for communication,

- you wrote thoughts in response to blog posts

- you observed how different data scientists communicate or present themselves, and have different styles

- your final project required communicating among each other

As for domain knowledge,

- lots of examples were shown to you: social networks, advertising, finance, pharma, recommender systems, dallas art museum

I heard people have been asking the following: why didn’t we see more data science coming from non-profits, governments, and universities? Note that data science, the term, was born in for-profits. But the truth is I’d also like to see more of that. It’s up to you guys to go get that done!

How do I measure the impact of this class I’ve created? Is it possible to incubate awesome data science teams in the classroom? I might have taken you from point A to point B but you might have gone there anyway without me. There’s no counterfactual!

Can we set this up as a data science problem? Can we use a causal modeling approach? This would require finding students who were more or less like you but didn’t take this class and use propensity score matching. It’s not a very well-defined experiment.

But the goal is important: in industry they say you can’t learn data science in a university, that it has to be on the job. But maybe that’s wrong, and maybe this class has proved that.

What has been the impact on you or to the outside world? I feel we have been contributing to the broader discourse.

Does it matter if there was impact? and does it matter if it can be measured or not? Let me switch gears.

What is data science again?

Data science could be defined as:

- A set of best practices used in tech companies, which is how I chose to design the course

- A space of problems that could be solved with data

- A science of data where you can think of the data itself as units

The bottom two have the potential to be the basis of a rich and deep research discipline, but in many cases, the way the term is currently used is:

- Pure hype

But it doesn’t matter how we define it, as much as that I want for you:

- to be problem solvers

- to be question askers

- to think about your process

- to use data responsibly and make the world better, not worse.

More on being problem solvers: cultivate certain habits of mind

Here’s a possible list of things to strive for, taken from here:

Here’s the thing. Tons of people can implement k-nearest neighbors, and many do it badly. What matters is that you cultivate the above habits, remain open to continuous learning.

In education in traditional settings, we focus on answers. But what we probably should focus on is how a student behaves when they don’t know the answer. We need to have qualities that help us find the answer.

Thought experiment

How would you design a data science class around habits of mind rather than technical skills? How would you quantify it? How would you evaluate? What would students be able to write on their resumes?

Comments from the students:

- You’d need to keep making people doing stuff they don’t know how to do while keeping them excited about it.

- have people do stuff in their own domains so we keep up wonderment and awe.

- You’d use case studies across industries to see how things work in different contexts

More on being question-askers

Some suggestions on asking questions of others:

- start with assumption that you’re smart

- don’t assume the person you’re talking to knows more or less. You’re not trying to prove anything.

- be curious like a child, not worried about appearing stupid

- ask for clarification around notation or terminology

- ask for clarification around process: where did this data come from? how will it be used? why is this the right data to use? who is going to do what? how will we work together?

Some questions to ask yourself

- does it have to be this way?

- what is the problem?

- how can I measure this?

- what is the appropriate algorithm?

- how will I evaluate this?

- do I have the skills to do this?

- how can I learn to do this?

- who can I work with? Who can I ask?

- how will it impact the real world?

Data Science Processes

In addition to being problem-solvers and question-askers, I mentioned that I want you to think about process. Here are a couple processes we discussed in this course:

(1) Real World –> Generates Data –>

–> Collect Data –> Clean, Munge (90% of your time)

–> Exploratory Data Analysis –>

–> Feature Selection –>

–> Build Model, Build Algorithm, Visualize

–> Evaluate –>Iterate–>

–> Impact Real World

(2) Asking questions of yourselves and others –>

Identifying problems that need to be solved –>

Gathering information, Measuring –>

Learning to find structure in unstructured situations–>

Framing Problem –>

Creating Solutions –> Evaluating

Thought experiment

Come up with a business that improves the world and makes money and uses data

Comments from the students:

- autonomous self-driving cars you order with a smart phone

- find all the info on people and then show them how to make it private

- social network with no logs and no data retention

10 Important Data Science Ideas

Of all the blog posts I wrote this semester, here’s one I think is important:

10 Important Data Science Ideas

Confidence and Uncertainty

Let’s talk about confidence and uncertainty from a couple perspectives.

First, remember that statistical inference is extracting information from data, estimating, modeling, explaining but also quantifying uncertainty. Data Scientists could benefit from understanding this more. Learn more statistics and read Ben’s blog post on the subject.

Second, we have the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Have you ever wondered why don’t people say “I don’t know” when they don’t know something? This is partly explained through an unconscious bias called the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Basically, people who are bad at something have no idea that they are bad at it and overestimate their confidence. People who are super good at something underestimate their mastery of it. Actual competence may weaken self-confidence.

Thought experiment

Design an app to combat the dunning-kruger effect.

Optimizing your life, Career Advice

What are you optimizing for? What do you value?

- money, need some minimum to live at the standard of living you want to, might even want a lot.

- time with loved ones and friends

- doing good in the world

- personal fulfillment, intellectual fulfillment

- goals you want to reach or achieve

- being famous, respected, acknowledged

- ?

- some weighted function of all of the above. what are the weights?

What constraints are you under?

- external factors (factors outside of your control)

- your resources: money, time, obligations

- who you are, your education, strengths & weaknesses

- things you can or cannot change about yourself

There are many possible solutions that optimize what you value and take into account the constraints you’re under.

So what should you do with your life?

Remember that whatever you decide to do is not permanent so don’t feel too anxious about it, you can always do something else later –people change jobs all the time

But on the other hand, life is short, so always try to be moving in the right direction (optimizing for what you care about).

If you feel your way of thinking or perspective is somehow different than what those around you are thinking, then embrace and explore that, you might be onto something.

I’m always happy to talk to you about your individual case.

Next Gen Data Scientists

The second blog post I think is important is this “manifesto” that I wrote:

Next-Gen Data Scientists. That’s you! Go out and do awesome things, use data to solve problems, have integrity and humility.

Here’s our class photo!

Costco visit

Yesterday I was in a bit of a funk.

I decided to try to get out and do something new, and since my neighbors were going to Costco, which I’d never been to (or maybe I had once but I couldn’t remember and it would have been at least 13 years ago), I invited myself to go with them. The change would do me good, I thought.

Here’s the thing about Costco which you probably already know if you shop there: it’s a rush, like taking a narcotic. I am sure that their data scientists have spent many computing hours munging through many terabytes of shopping behavior to perfect this effect [Update: an article has just appeared in the New York Times explaining this very thing].

For example, I’m on a budget, and I was planning to go for the sociological experience of it, not to buy anything. After all, I’ve already gotten my groceries for the week, and bought reasonable presents for the kids for Christmas. Nothing outrageous. So I was feeling pretty safe.

But then I got there, and I immediately came across things I didn’t know I needed until I saw them. The most ridiculous and startling version of this was my tupperware experience.

Tupperware is an essential tool in a house with three kids, because if you do the math you’ve got 15 school lunches to make per week. That’s not something you can scrounge up carelessly. So what you do is save plastic Chinese takeout containers and fill them up after dinners with things like pasta and chicken bits. Ready to go in the morning.

But when I came across the gorgeous 30-, no 42-, no 75-piece rainbow-colored tupperware kits that actually stack together beautifully, I instantaneously realized my hitherto scheme was laughably ridiculous and that I must own gorgeous tupperware right now.

This happened to me with a rainbow-colored knife set too, but I managed to hold myself back because, I argued, I already owned knives. I am not sure why that reasoning failed with the tupperware.

In fact I immediately filled up a cart with various (rainbow-colored) things I had no idea I needed until I got there ($50 for a cashmere sweater!?), and then I started wandering around the food area.

This is when my narcotic experience started to wear off. I think it was around the 6-pound block of mozzarella that I started to say to myself, wait, do I really want 6 pounds of mozzarella? I mean, it’s a great price, but won’t that take up half my fridge?

Then I started putting stuff back. It was amazingly easy to part with that stuff once the narcotic wore off. I was in deep withdrawal by the time we left the store. Paying in cash for the few items I did buy also helped.

My conclusions:

- I totally get why people own lots of stuff they don’t need.

- I’m sure people can get addicted to that narcotic shopping rush.

- We should consider treating Costco as a dealer in controlled substances.

- I have ugly tupperware and that’s okay.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Last week I asked you guys to answer this question for me:

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How should I organize my bookshelf? I have 1000+ books.

Booknerd

As usual, you guys impressed me with your various uber-nerdy answers, some by email. Here are some excellent book-organizing suggestions:

- By color

- By publisher

- Via the tool librarything.com

- By your personal history reading the book – how old were you? This might be hard for me and Little House on the Prairie, which I read numerous times as a kid, then in Dutch to learn the language when I got married to a Dutch man, and now again because I just want to

- My personal favorite:

Sort books by copyright date of first editions. This would give an insight into the development of ideas. One problem with this is that it would make locating a book more difficult so an electronic index would be a valuable supplement. My initial thought was to do this only within categories, but as I think of it, it would be interesting to see fiction interspersed with history, philosophy or science.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My kid went to California last year to study number theory, computer science and physics at a highly regarded university. After getting his dream summer job with a fast growing startup known for hiring only the brightest and spoiling them with great food, good money and lots of benefits he’s starting to adopt some of the libertarian founders viewpoints on life. For next summer, he’s interviewing with some hedge funds known to recruit and “develop” talented math kids. It is looking like he’s going to the Dark Side. What can be done to turn this around and avoid the pain Mathbabe’s father must have gone through?

Failed Parent

Dear Failed Parent,

First of all, my dad was disappointed when I went into math instead of economics, psyched when I left academics for a hedge fund, and disappointed when I quit finance. So much for role modeling.

Second of all, I find your story consistent with my experience of super smart people finding it shockingly fun to be super smart and developing a viewpoint which allows them (or even encourages them) to take advantage of less smart people because they can and because it’s legal, independent of whether it’s moral.

There’s this whole machine, of which hedge funds are a large part, and some math and science camps too, which feed into this rhetoric and profit from it. I call it the fetishization of intelligence. People get so in love with their talent they think it transcends them above mere morality.

So the story isn’t good, and your son is another cog in the intelligence-as-fetish machine. And moreover, you’re not going to be able to talk him out of it, not now when most of the world is telling him he’s kind of an outsider and weak and unattractive (if he’s like most young men this is how they feel they’re treated, even if they aren’t actually unattractive or weak or outsiderish) whereas there’s this tiny contingent telling him he has super powers. Why would he listen to you?

My advice: wait it out. He’ll probably at some point realize he could be getting more out of life if he had stuff he’d done that he could be proud of. Then it’s time for you to have a list of things he might want to do that don’t involve taking advantage of “dumb money” and do involve applying his brains to discovery and solving important problems. Or at least have a pen and paper ready to help him make such a list.

One more piece of advice: if he claims that what he does is morally neutral because if he didn’t do it someone else would, please don’t pass up that opportunity to point out all the evil that has been done by otherwise decent people with that very line. I can’t tell you how many times I hear that. I refuse to help people feel comfortable with their uncomfortable choices.

Good luck, and please get back to me in 10 years to tell me how things are.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m a PhD candidate in Math and I’m going to get into quantitative finance. I’m wondering how hard it is these days for a quant to maintain his integrity without undermining success? Any tips in doing so? Have you seen many happy yet righteous quant?

Fish in the Forest

Dear FitF,

After having a few jobs outside academia, I’m pretty sure that you get paid extra in finance partly because you’re smart and the skills you have are rare, but partly because you’re doing something pretty iffy on the righteous scale.

I’m not saying that there are no righteous quants, but I’m saying that if everyone had a righteous score and a salary score, then there would be a negative correlation between those two lists.

So I’m on the job market, and I am not totally against working in finance, because there are all kinds of jobs, but the ones I’m interested in are doing things like making accounting reports machine-readable and consistently formatted, to promote transparency. This doesn’t pay the big bucks as you might imagine.

Here are some snarky tips for you to continue to feel righteous if you work in finance:

- Figure out what the information is that you know but other people don’t. See if that matters to you. Example: insider trading, does it make you feel dirty? Maybe not, in which case you’re good.

- Start reading Ayn Rand and develop a sense that you are entitled to be rich because you’re so smart, and that anyone who doesn’t agree must be super dumb (see previous post for how to go about this, although you may be too old to go to summer camps).

- Do you mind lying? How about omitting the truth? How about pretending to regulators that you have a firm grasp on the underlying risk of a instrument class because there’s a magical mathematical formula someone with a Ph.D. came up with who can’t explain it to anyone? Good?

Good luck, and tell me how it goes!

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers, it’s time for you to answer a question! This one is particularly outside my realm, but I have faith in you good people to help:

Aunt Pythia,

I’ve been finding it really hard as an adult who has stepped out of the higher education track because of a lack of funding to find resources for adults in the same vein as what i found as a young adult. Are there any resources out there that you would recommend for a minority woman aged 29+ looking for training opportunities that are more experiential than internship based?

NYC and Wondering

——

Please ask Aunt Pythia a question! She loves her job and can’t wait to give you unreasonable, useless, and possibly damaging counsel!

How math departments hire faculty

I just got back from a stimulating trip to Stony Brook to give the math colloquium there. I had a great time thanks to my gracious host Jason Starr (this guy, not this guy), and besides giving my talk (which I will give again in San Diego at the joint meetings next month) I enjoyed two conversations about the field of math which I think could be turned into data science projects. Maybe Ph.D. theses or something.

First, a system for deciding whether a paper on the arXiv is “good.” I will post about that on another day because it’s actually pretty involved and possible important.

Second is the way people hire in math departments. This conversation will generalize to other departments, some more than others.

So first of all, I want to think about how the hiring process actually works. There are people who look at folders of applicants, say for tenure-track jobs. Since math is a pretty disjointed field, a majority of the folders will only be understood well enough for evaluation purposes by a few people in the department.

So in other words, the department naturally splits into clusters more or less along field lines: there are the number theorists and then there are the algebraic geometers and then there are the low-dimensional topologists, say.

Each group of people reads the folders from the field or fields that they have enough expertise in to understand. Then from among those they choose some they want to go to bat for. It becomes a political battle, where each group tries to convince the other groups that their candidates are more qualified. But of course it’s really hard to know who’s telling the honest truth. There are probably lots of biases in play too, so people could be overstating their cases unconsciously.

Some potential problems with this system:

- if you are applying to a department where nobody is in your field, nobody will read your folder, and nobody will go to bat for you, even if you are really great. An exaggeration but kinda true.

- in order to be convincing that “your guy is the best applicant,” people use things like who the advisor is or which grad school this person went to more than the underlying mathematical content.

- if your department grows over time, this tends to mean that you get bigger clusters rather than more clusters. So if you never had a number theorist, you tend to never get one, even if you get more positions. This is a problem for grad students who want to become number theorists, but that probably isn’t enough to affect the politics of hiring.

So here’s my data science plan: test the above hypotheses. I said them because I think they are probably true, but it would be not be impossible to create the dataset to test them thoroughly and measure the effects.

The easiest and most direct one to test is the third: cluster departments by subject by linking the people with their published or arXiv’ed papers. Watch the department change over time and see how the clusters change and grow versus how it might happen randomly. Easy peasy lemon squeazy if you have lots of data. Start collecting it now!

The first two are harder but could be related to the project of ranking papers. In other words, you have to define “is really great” to do this. It won’t mean you can say with confidence that X should have gotten a job at University Y, but it would mean you could say that if X’s subject isn’t represented in University Y’s clusters, then X’s chances of getting a job there, all other things being equal, is diminished by Z% on average. Something like that.

There are of course good things about the clustering. For example, it’s not that much fun to be the only person representing a field in your department. I’m not actually passing judgment on this fact, and I’m also not suggesting a way to avoid it (if it should be avoided).

Unequal or Unfair: Which Is Worse?

This is a guest post by Alan Honick, a filmmaker whose past work has focused primarily on the interaction between civilization and natural ecosystems, and its consequences to the sustainability of both. Most recently he’s become convinced that fairness is the key factor that underlies sustainability, and has embarked on a quest to understand how our notions of fairness first evolved, and what’s happening to them today. I posted about his work before here. This is crossposted from Pacific Standard.

Inequality is a hot topic these days. Massive disparities in wealth and income have grown to eye-popping proportions, triggering numerous studies, books, and media commentaries that seek to explain the causes of inequality, why it’s growing, and its consequences for society at large.

Inequality triggers anger and frustration on the part of a shrinking middle class that sees the American Dream slipping from its grasp, and increasingly out of the reach of its children. But is it inequality per se that actually sticks in our craw?

There will always be inequality among humans—due to individual differences in ability, ambition, and more often than most would like to admit, luck. In some ways, we celebrate it. We idolize the big winners in life, such as movie and sports stars, successful entrepreneurs, or political leaders. We do, however (though perhaps with unequal ardor) feel badly for the losers—the indigent and unfortunate who have drawn the short straws in the lottery of life.

Thus, we accept that winning and losing are part of life, and concomitantly, some level of inequality.

Perhaps it’s simply the extremes of inequality that have changed our perspective in recent years, and clearly that’s part of the explanation. But I put forward the proposition that something far more fundamental is at work—a force that emerges from much deeper in our evolutionary past.

Take, for example, the recent NFL referee lockout, where incompetent replacement referees were hired to call the games.There was an unrestrained outpouring of venom from outraged fans as blatantly bad calls resulted in undeserved wins and losses. While sports fans are known for the extremity of their passions, they accept winning and losing; victory and defeat are intrinsic to playing a game.

What sparked the fans’ outrage wasn’t inequality—the win or the loss. Rather, the thing they couldn’t swallow—what stuck in their craw—was unfairness.

I offer this story from the KLAS-TV News website. It’s a Las Vegas station, and appropriately, the story is about how the referee lockout affected gamblers. It addresses the most egregiously bad call of the lockout, in a game between the Seattle Seahawks and the Green Bay Packers. From the story:

In a call so controversial the President of the United States weighed in, Las Vegas sports bettors said they lost out on a last minute touchdown call Monday night…

….Chris Barton, visiting Las Vegas from Rhode Island, said he lost $1,200 on the call against Green Bay. He said as a gambler, he can handle losing, “but not like that.”

“I’ve been gambling for 30 years almost, and that’s the worst defeat ever,” he said.

By the way, Obama’s “weigh-in” was through his Twitter feed, which I reproduce here:

“NFL fans on both sides of the aisle hope the refs’ lockout is settled soon. –bo”

When questioned about the president’s reaction, his press secretary, Jay Carney, said Obama thought “there was a real problem with the call,” and said the president expressed frustration at the situation.

I think this example is particularly instructive, simply because money’s involved, and money—the unequal distribution of it—is where we began.

Fairness matters deeply to us. The human sense of fairness can be traced back to the earliest social-living animals. One of its key underlying components is empathy, which began with early mammals. It evolved through processes such as kin selection and reciprocal altruism, which set us on the path toward the complex societies of today.

Fairness—or lack of it—is central to human relationships at every level, from a marriage between two people to disputes involving war and peace among the nations of the world.

I believe fairness is what we need to focus on, not inequality—though I readily acknowledge that high inequality in wealth and income is corrosive to society. Why that is has been eloquently explained by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkerson in their book, The Spirit Level. The point I have been trying to make is that inequality is the symptom; unfairness is the underlying disease.

When dealing with physical disease, it’s important to alleviate suffering by treating painful symptoms, and inequality can certainly be painful to those who suffer at the lower end of the wage scale, or with no job at all. But if we hope for a lasting cure, we need to address the unfairness that causes it.

That said, creating a fairer society is a daunting challenge. Inequality is relatively easy to understand—it’s measurable by straightforward statistics. Fairness is a subtler concept. Our notions of fairness arise from a complex interplay between biology and culture, and after 10,000 years of cultural evolution, it’s often difficult to pick them apart.

Yet many researchers are trying. They are looking into the underlying components of the human sense of fairness from a variety of perspectives, including such disciplines as behavioral genetics, neuroscience, evolutionary and developmental psychology, animal behavior, and experimental economics.

In order to better understand fairness, and communicate their findings to a larger audience, I’ve embarked on a multimedia project to work with these researchers. The goal is to synthesize different perspectives on our sense of fairness, to paint a clearer picture of its origins, its evolution, and its manifestations in the social, economic, and political institutions of today.

The first of these multimedia stories appeared here at Pacific Standard. Called The Evolution of Fairness, it is about archaeologist Brian Hayden. It explores his central life work—a dig in a 5000 year old village in British Columbia, where he uncovered evidence of how inequality may have first evolved in human society.

I found another story on a CNN blog about the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. In it, Paul Ryan compares the unfair refereeing to President Obama’s poor handling of the economy. He says, “If you can’t get it right, it’s time to get out.” He goes on to say, “Unlike the Seattle Seahawks last night, we want to deserve this victory.”

We now know how that turned out, though we don’t know if Congressman Ryan considers his own defeat a deserved one.

I’ll close with a personal plea to President Obama. I hope—and believe—that as you are starting your second term, you are far more frustrated with the unfairness in our society than you were with the bad call in the Seahawks/Packers game. It’s arguable that some of the rules—such as those governing campaign finance—have themselves become unfair. In any case, if the rules that govern society are enforced by bad referees, fairness doesn’t stand much of a chance, and as we’ve seen, that can make people pretty angry.

Please, for the sake of fairness, hire some good ones.

Can we put an ass-kicking skeptic in charge of the SEC?

The SEC has proven its dysfunctionality. Instead of being on top of the banks for misconduct, it consistently sets the price for it at below cost. Instead of examining suspicious records to root out Ponzi schemes, it ignores whistleblowers.

I think it’s time to shake up management over there. We need a loudmouth skeptic who is smart enough to sort through the bullshit, brave enough to stand up to bullies, and has a strong enough ego not to get distracted by threats about their future job security.

My personal favorite choice is Neil Barofsky, author of Bailout (which I blogged about here) and former Special Inspector General of TARP. Simon Johnson, Economist at MIT, agrees with me. From Johnson’s New York Times Economix blog:

… Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector general in charge of oversight for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. A career prosecutor, Mr. Barofsky tangled with the Treasury officials in charge of handing out support for big banks while failing to hold the same banks accountable — for example, in their treatment of homeowners. He confronted these powerful interests and their political allies repeatedly and on all the relevant details – both behind closed doors and in his compelling account, published this summer: “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.”

His book describes in detail a frustration with the timidity and lack of sophistication in law enforcement’s approach to complex frauds. He could instantly remedy that if appointed — Mr. Barofsky is more than capable of standing up to Wall Street in an appropriate manner. He has enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the past and could be confirmed by the Senate (just as he was previously confirmed to his TARP position).

Barofsky isn’t the only person who would kick some ass as the head of the SEC – William Cohan thinks Eliot Spitzer would make a fine choice, and I agree. From his Bloomberg column (h/t Matt Stoller):

The idea that only one of Wall Street’s own can regulate Wall Street is deeply disturbing. If Obama keeps Walter on or appoints Khuzami or Ketchum, we would be better off blowing up the SEC and starting over.

I still believe the best person to lead the SEC at this moment remains former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer. He would fearlessly hold Wall Street accountable for its past sins, as he did when he was New York State attorney general and as he now does as a cable television host. (Disclosure: I am an occasional guest on his show.)

We need an SEC head who can inspire a new generation of investors to believe the capital markets are no longer rigged and that Wall Street cannot just capture every one of its Washington regulators.

Diophantus and the math arXiv

Last night my 7th-grade son, who is working on a school project about the mathematician Diophantus, walked into the living room with a mopey expression.

He described how Diophantus worked on a series of mathematical texts called Arithmetica, in which he described the solutions to what we now describe as diophantine equations, but which are defined as polynomial equations with strictly integer coefficients, and where the solutions we care about are also restricted to be integers. I care a lot about this stuff because it’s what I studied when I was an academic mathematician, and I still consider this field absolutely beautiful.

What my son was upset about, though, was that of the 13 original books in Arhtimetica, only 6 have survived. He described this as “a way of losing progress“. I concur: Diophantus was brilliant, and there may be things we still haven’t recovered from that text.

But it also struck me that my son would be right to worry about this idea of losing progress even today.

We now have things online and often backed up, so you’d think we might never need to worry about this happening again. Moreover, there’s something called the arXiv where mathematicians and physicists put all or mostly all their papers before they’re published in journals (and many of the papers never make it to journals, but that’s another issue).

My question is, who controls this arXiv? There’s something going on here much like Josh Wills mentioned last week in Rachel Schutt’s class (and which Forbes’s Gil Press responded to already).

Namely, it’s not all that valuable to have one unreviewed, unpublished math paper in your possession. But it’s very valuable indeed to have all the math papers written in the past 10 years.

If we lost access to that collection, as a community, we will have lost progress in a huge way.

Note: I’m not accusing the people who run arXiv of anything weird. I’m sure they’re very cool, and I appreciate their work in keeping up the arXiv. I just want to acknowledge how much power they have, and how strange it is for an entire field to entrust that power to people they don’t know and didn’t elect in a popular vote.

As I understand it (and I could be wrong, please tell me if I am), the arXiv doesn’t allow crawlers to make back-ups of the documents. I think this is a mistake, as it increases the public reliance on this one resource. It’s unrobust in the same way it would be if the U.S. depended entirely on its food supply from a country whose motives are unclear.

Let’s not lose Arithmetica again.

How do we quantitatively foster leadership?

I was really impressed with yesterday’s Tedx Women at Barnard event yesterday, organized by Nathalie Molina, who organizes the Athena Mastermind group I’m in at Barnard. I went to the morning talks to see my friend and co-author Rachel Schutt‘s presentation and then came home to spend the rest of the day with my kids, but they other three I saw were also interesting and food for thought.

Unfortunately the videos won’t be available for a month or so, and I plan to blog again when they are for content, but I wanted to discuss an issue that came up during the Q&A session, namely:

what we choose to quantify and why that matters, especially to women.

This may sound abstract but it isn’t. Here’s what I mean. The talks were centered around the following 10 themes:

- Inspiration: Motivate, and nurture talented people and build collaborative teams

- Advocacy: Speak up for yourself and on behalf of others

- Communication: Listen actively; speak persuasively and with authority

- Vision: Develop strategies, make decisions and act with purpose

- Leverage: Optimize your networks, technology, and financing to meet strategic goals; engage mentors and sponsors

- Entrepreneurial Spirit: Be innovative, imaginative, persistent, and open to change

- Ambition: Own your power, expertise and value

- Courage: Experiment and take bold, strategic risks

- Negotiation: Bridge differences and find solutions that work effectively for all parties

- Resilience: Bounce back and learn from adversity and failure

The speakers were extraordinary and embodied their themes brilliantly. So Rachel spoke about advocating for humanity through working with data, and this amazing woman named Christa Bell spoke about inspiration, and so on. Again, the actual content is for another time, but you get the point.

A high school teacher was there with five of her female students. She spoke eloquently of how important and inspiring it was that these girls saw these talk. She explained that, at their small-town school, there’s intense pressure to do well on standardized tests and other quantifiable measures of success, but that there’s essentially no time in their normal day to focus on developing the above attributes.

Ironic, considering that you don’t get to be a “success” without ambition and courage, communication and vision, or really any of the themes.

In other words, we have these latent properties that we really care about and are essential to someone’s success, but we don’t know how to measure them so we instead measure stuff that’s easy to measure, and reward people based on those scores.

By the way, I’m not saying we don’t also need to be good at content, and tasks, which are easier to measure. I’m just saying that, by focusing on content and tasks, and rewarding people good at that, we’re not developing people to be more courageous, or more resilient, or especially be better advocates of others.

And that’s where the women part comes in. Women, especially young women, are sensitive to the expectations of the culture. If they are getting scored on X, they tend to focus on getting good at X. That’s not a bad thing, because they usually get really good at X, but we have to understand the consequences of it. We have to choose our X’s well.

I’d love to see a system evolve wherein young women (and men) are trained to be resilient and are rewarded for that just as they’re trained to do well on the SAT’s and rewarded for that. How do you train people to be courageous? I’m sure it can be done. How crazy would it be to see a world where advocating for others is directly encouraged?

Let’s try to do this, and hell let’s quantify it too, since that desire, to quantify everything, is not going away. Instead of giving up because important things are hard to quantify, let’s just figure out a way to quantify them. After all, people didn’t think their musical tastes could be quantified 15 years ago but now there’s Pandora.

Update: Ok to quantify this, but the resulting data should not be sold or publicly available. I don’t want our sons’ and daughters’ “resilience scores” to be part of their online personas for everyone to see.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is overwhelmed with joy today, readers, and not only because she gets to refer to herself in the third person.

The number and quality of math book suggestions from last week have impressed Auntie dearly, and with the permission of mathbabe, which wasn’t hard to get, she established a new page with the list of books, just in time for the holiday season. I welcome more suggestions as well as reviews.

On to some questions. As usual, I’ll have the question submission form at the end. Please put your questions to Aunt Pythia, that’s what she’s here for!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I was one of those kids who when asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” said “Errrghm …” or maybe just ignored the question. Today I am still that confused toddler. I have changed fields a few times (going through a major makeover right now), never knew what I want to dive into, found too many things too interesting. I worry that half a life from now, I will have done lots and nothing. I crave having a passion, one goal – something to keep trying to get better at. What advice do you have for the likes of me?

Forever Yawning or Wandering Globetrotter

Dear FYoWG,

I can relate. I am constantly yearning to have enough time to master all sorts of skills that I just know would make me feel fulfilled and satisfied, only to turn around and discover yet more things I’d love to devote myself to. What ever happened to me learning to flatpick the guitar? Why haven’t I become a production Scala programmer?

It’s enough to get you down, all these unrealized hopes and visions. But don’t let it! Remember that the people who only ever want one thing in life are generally pretty bored and pretty boring. And also remember that it’s better to find too many things too interesting than it is to find nothing interesting.

And also, I advise you to look back on the stuff you have gotten done, and first of all give yourself credit for those things, and second of all think about what made them succeed: probably something like the fact that you did it gradually but consistently, you genuinely liked doing it and learning from it, and you had the resources and environment for it to work.

Next time you want to take on a new project, ask yourself if all of those elements are there, and then ask yourself what you’d be dropping if you took it on. You don’t have to have definitive answers to these questions, but even having some idea will help you decide how realistic it is, and will also make you feel more like it’s a decision rather than just another thing you won’t feel successful at.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

My boss lacks leadership qualities and is untrustworthy, and I will resign soon. Should I tell his boss what I think of this boss?

Novembertwentyeleven

Dear November,

In Aunt Pythia’s humble opinion, one of the great joys of life is the exit interview. Why go out with a whimper when you have the opportunity to go out with a big-ass ball of flame?

Let’s face it, it’s a blast to vent honestly and thoroughly on your way out the door, and moreover it’s expected. Why else would you be leaving? Because of some goddamn idiot, that’s why! Why not say who?

You’ll hear people say not to “burn bridges”. That’s boooooooring. I say, burn those motherfuckers to the ground!

Especially when you’re talking about people with whom you’d never ever work again, ever ever. Sometimes you just know it’ll never happen. And it feels great, trust me. I’m a pro.

That said, don’t expect anyone to listen to you, cuz that aint gonna happen. Nobody listens to people when they leave. Sadly, most people also don’t listen to people when they stay, either, so you’re shit out of luck in any case. But as long as you know that you’re good.

I hope that helped!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How should I organize my bookshelf? I have 1000+ books.

Booknerd

Readers! I want some suggestions, and please make them nerdy and/or funny! I know I can count on you.

——

Please ask Aunt Pythia a question! She loves her job and can’t wait to give you unreasonable, useless, and possibly damaging counsel!

How to build a model that will be gamed

I can’t help but think that the new Medicare readmissions penalty, as described by the New York Times, is going to lead to wide-spread gaming. It has all the elements of a perfect gaming storm. First of all, a clear economic incentive:

Medicare last month began levying financial penalties against 2,217 hospitals it says have had too many readmissions. Of those hospitals, 307 will receive the maximum punishment, a 1 percent reduction in Medicare’s regular payments for every patient over the next year, federal records show.

It also has the element of unfairness:

“Many of us have been working on this for other reasons than a penalty for many years, and we’ve found it’s very hard to move,” Dr. Lynch said. He said the penalties were unfair to hospitals with the double burden of caring for very sick and very poor patients.

“For us, it’s not a readmissions penalty,” he said. “It’s a mission penalty.”

And the smell of politics:

In some ways, the debate parallels the one on education — specifically, whether educators should be held accountable for lower rates of progress among children from poor families.

“Just blaming the patients or saying ‘it’s destiny’ or ‘we can’t do any better’ is a premature conclusion and is likely to be wrong,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, director of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at Yale-New Haven Hospital, which prepared the study for Medicare. “I’ve got to believe we can do much, much better.”

Oh wait, we already have weird side effects of the new rule:

With pressure to avert readmissions rising, some hospitals have been suspected of sending patients home within 24 hours, so they can bill for the services but not have the stay counted as an admission. But most hospitals are scrambling to reduce the number of repeat patients, with mixed success.

Note, the new policy is already a kind of reaction to gaming that’s already there, namely because of the stupid way Medicare decides how much to pay for treatment (emphasis mine):

Hospitals’ traditional reluctance to tackle readmissions is rooted in Medicare’s payment system. Medicare generally pays hospitals a set fee for a patient’s stay, so the shorter the visit, the more revenue a hospital can keep. Hospitals also get paid when patients return. Until the new penalties kicked in, hospitals had no incentive to make sure patients didn’t wind up coming back.

How about, instead of adding a weird rule that compromises people’s health and especially punishes poor sick people and the hospitals that treat them, we instead improve the original billing system? Otherwise we are certain to see all sorts of weird effects in the coming years with people being stealth readmitted under different names or something, or having to travel to different hospitals to be seen for their congestive heart failure.

Columbia Data Science course, week 13: MapReduce

The week in Rachel Schutt’s Data Science course at Columbia we had two speakers.

The first was David Crawshaw, a Software Engineer at Google who was trained as a mathematician, worked on Google+ in California with Rachel, and now works in NY on search.

David came to talk to us about MapReduce and how to deal with too much data.

Thought Experiment

Let’s think about information permissions and flow when it comes to medical records. David related a story wherein doctors estimated that 1 or 2 patients died per week in a certain smallish town because of the lack of information flow between the ER and the nearby mental health clinic. In other words, if the records had been easier to match, they’d have been able to save more lives. On the other hand, if it had been easy to match records, other breaches of confidence might also have occurred.

What is the appropriate amount of privacy in health? Who should have access to your medical records?

Comments from David and the students:

- We can assume we think privacy is a generally good thing.

- Example: to be an atheist is punishable by death in some places. It’s better to be private about stuff in those conditions.

- But it takes lives too, as we see from this story.

- Many egregious violations happen in law enforcement, where you have large databases of license plates etc., and people who have access abuse it. In this case it’s a human problem, not a technical problem.

- It’s also a philosophical problem: to what extent are we allowed to make decisions on behalf of other people?

- It’s also a question of incentives. I might cure cancer faster with more medical data, but I can’t withhold the cure from people who didn’t share their data with me.

- To a given person it’s a security issue. People generally don’t mind if someone has their data, they mind if the data can be used against them and/or linked to them personally.

- It’s super hard to make data truly anonymous.

MapReduce

What is big data? It’s a buzzword mostly, but it can be useful. Let’s start with this:

You’re dealing with big data when you’re working with data that doesn’t fit into your compute unit. Note that’s an evolving definition: big data has been around for a long time. The IRS had taxes before computers.

Today, big data means working with data that doesn’t fit in one computer. Even so, the size of big data changes rapidly. Computers have experienced exponential growth for the past 40 years. We have at least 10 years of exponential growth left (and I said the same thing 10 years ago).

Given this, is big data going to go away? Can we ignore it?

No, because although the capacity of a given computer is growing exponentially, those same computers also make the data. The rate of new data is also growing exponentially. So there are actually two exponential curves, and they won’t intersect any time soon.

Let’s work through an example to show how hard this gets.

Word frequency problem

Say you’re told to find the most frequent words in the following list: red, green, bird, blue, green, red, red.

The easiest approach for this problem is inspection, of course. But now consider the problem for lists containing 10,000, or 100,000, or words.

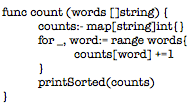

The simplest approach is to list the words and then count their prevalence. Here’s an example code snippet from the language Go:

Since counting and sorting are fast, this scales to ~100 million words. The limit is now computer memory – if you think about it, you need to get all the words into memory twice.