Archive

Ask Aunt Pythia

Peoples!! Peoples!!

I know you came for Aunt Pythia (thank you very much!) but today I must insist that, first, you go read my new hero’s advice column, Dear Miss Disruption, who has been quite the twitter celebrity this week.

Written by a law student named Sarah Jeong from Oakland, Miss Disruption has super awesome advice for the budding entrepreneur – or, in fact, anyone at all. She even took on my favorite topic, namely how people lie when counting their previous lovers! Here’s a tasty excerpt:

I sympathize. You and I both know, learning to code is the best way to pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Hell, look at me. Other than my affluent Orange County family, my Stanford bachelor’s degree, and the $10 million that my uncle invested as seed capital for my innovative advice column start-up, I have nothing but my ability to code.

I’ll admit that Miss Disruption is a tad more sarcastic than Aunt Pythia, but she’s super funny and smart just like Aunt Pythia, so I know you guys will love her.

After you go read her stuff, please come back here, read my stuff, and, by all means,

Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am 26, and I presently work in education. I studied history as an undergrad, but I would like to pursue a master’s degree in statistics. I need to learn some lower division math and programming. There are online courses and resources out there. Would it be better to pursue the courses with instructors and peers to the extent possible, or do you think it makes little difference?

Depressed in the Burbs

Dear Depressed,

It depends. In terms of what you might learn, I could see it making very little difference. But you have another goal too, namely getting into a masters program in statistics. It might be more convincing to the admissions people to see an official set of courses in math and programming with official grades than for you to tell them you learned it on your own, although perhaps online courses do offer quasi-official grades, and also it might depend on the masters program – some of them are just cash cows.

But then there’s also the issue of sticking it out and being invested. Have you considered taking these courses at some kind of extension school or community college? The community part of it might end up helping a lot.

Good luck,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dearest Aunt Pythia,

A beloved friend of mine recently came to visit and spent two sweet days singing with me, laughing at nothing/everything, gorging ourselves on waffles, and otherwise squandering time in shared luxurious idleness. In sum, fun was had.

The day after she left, I discovered a fat wad of cash underneath my pillow, which she hid there for me to find in a characteristic act of willful generosity. The thing is, I did nothing to earn this money and in fact feel quite indebted to her for her lifelong friendship and general camaraderie. My dilemma is: should I keep the money or send it back? If the former, how can I possibly thank her for her disproportionate magnanimity? I’m verklempt over here.

Grateful Gal Pal

Dear GGP,

Money is a funny thing, especially between friends. But sometimes it actually isn’t. Here’s my wild guess as to the circumstances.

Your good friend was incredibly grateful for your sanctuary and your luxurious idleness, which is exactly what she needed at that moment and perhaps even saved her sanity and her life, and was in particular an almost offhand bounty naturally stemming from your lifestyle. She wanted to give you something in return that was her kind of offhand bounty that she thought might help you with your life – at the very least to sustain you for some time in the heaven in which you currently reside.

So ask yourself this: is this an amount of money she can afford? Can it give you pleasure in some small way? If so, then please accept it as it was meant, namely as a thank you and a gift, and go buy ingredients for some more waffles.

Love always,

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I had a very weird dream today. I dreamed that, to support Snowden, all couples in the world made a porn video and uploaded it in the Internet. Did I already surpass the limits of madness?

Crazy Lazy

Dear CL,

I for one think Chelsea Manning is hot. That’s what I got for this question.

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have recently discovered my partner of 2 years had sexual relations with his aunt not long before we began our relationship. He claimed to be a virgin when I started seeing him and now I know he lied. I love him and we have children together, I would like some advice and opinions thank you.

A

Dear A,

First of all I’m getting a bit confused thinking about how you can have multiple children together given that you have only been together 2 years. I’m guessing you got started quick and you had twins, or you got started immediately, squeezed out a pup, and then immediately got pregnant again, which is super unlikely.

Or you made up this whole thing, which is always a possibility that advice columnists need to consider. It’s probably even more likely given the incest theme. But whatever, I’m almost out of questions.

Second, I think it really depends on the circumstances. Was he a kid? Was it sexual abuse perpetrated on him by a trusted loved one? If so, by all means forgive him immediately, but also have him seek counseling if he’s willing.

The tough one is if he was an adult when he got involved with the Aunt. I’m no expert on human sexuality but I’d guess that someone who doesn’t have taboos about incest with Aunts might not have taboos with other kinds of things either. That would creep me out as the mother of this guy’s kids.

In any case, my advice to you is to go seek counseling yourself with an expert on sexual abuse.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Don’t Fly During Ramadan

Crossposted from /var/null, a blog written by Aditya Mukerjee. Aditya graduated from Columbia with a degree in CS and statistics, was a hackNY Fellow, worked in data at OkCupid, and on the server team at foursquare. He currently serves as the Hacker-in-Residence at Quotidian Ventures.

A couple of weeks ago, I was scheduled to take a trip from New York (JFK) to Los Angeles on JetBlue. Every year, my family goes on a one-week pilgrimage, where we put our work on hold and spend time visiting temples, praying, and spending time with family and friends. To my Jewish friends, I often explain this trip as vaguely similar to the Sabbath, except we take one week of rest per year, rather than one day per week.

Our family is not Muslim, but by coincidence, this year, our trip happened to be during the last week of Ramadan.

By further coincidence, this was also the same week that I was moving out of my employer-provided temporary housing (at NYU) and moving into my new apartment. The night before my trip, I enlisted the help of two friends and we took most of my belongings, in a couple of suitcases, to my new apartment. The apartment was almost completely unfurnished – I planned on getting new furniture upon my return – so I dropped my few bags (one containing an air mattress) in the corner. Even though I hadn’t decorated the apartment yet, in accordance with Hindu custom, I taped a single photograph to the wall in my bedroom — a long-haired saint with his hands outstretched in pronam (a sign of reverence and respect).

The next morning, I packed the rest of my clothes into a suitcase and took a cab to the airport. I didn’t bother to eat breakfast, figuring I would grab some yogurt in the terminal while waiting to board.

I got in line for security at the airport and handed the agent my ID. Another agent came over and handed me a paper slip, which he said was being used to track the length of the security lines. He said, “just hand this to someone when your stuff goes through the x-ray machines, and we’ll know how long you were in line.’ I looked at the timestamp on the paper: 10:40.

When going through the security line, I opted out (as I always used to) of the millimeter wave detectors. I fly often enough, and have opted out often enough, that I was prepared for what comes next: a firm pat-down by a TSA employee wearing non-latex gloves, who uses the back of his hand when patting down the inside of the thighs.

After the pat-down, the TSA agent swabbed his hands with some cotton-like material and put the swab in the machine that supposedly checks for explosive residue. The machine beeped. “We’re going to need to pat you down again, this time in private,” the agent said.

Having been selected before for so-called “random” checks, I assumed that this was another such check.

“What do you mean, ‘in private’? Can’t we just do this out here?”

“No, this is a different kind of pat-down, and we can’t do that in public.” When I asked him why this pat-down was different, he wouldn’t tell me. When I asked him specifically why he couldn’t do it in public, he said “Because it would be obscene.”

Naturally, I balked at the thought of going somewhere behind closed doors where a person I just met was going to touch me in “obscene” ways. I didn’t know at the time (and the agent never bothered to tell me) that the TSA has a policy that requires two agents to be present during every private pat-down. I’m not sure if that would make me feel more or less comfortable.

Noticing my hesitation, the agent offered to have his supervisor explain the procedure in more detail. He brought over his supervisor, a rather harried man who, instead of explaining the pat-down to me, rather rudely explained to me that I could either submit immediately to a pat-down behind closed-doors, or he could call the police.

At this point, I didn’t mind having to leave the secure area and go back through security again (this time not opting out of the machines), but I didn’t particularly want to get the cops involved. I told him, “Okay, fine, I’ll leave”.

“You can’t leave here.”

“Are you detaining me, then?” I’ve been through enough “know your rights” training to know how to handle police searches; however, TSA agents are not law enforcement officials. Technically, they don’t even have the right to detain you against your will.

“We’re not detaining you. You just can’t leave.” My jaw dropped.

“Either you’re detaining me, or I’m free to go. Which one is it?” I asked.

He glanced for a moment at my backpack, then snatched it out of the conveyor belt. “Okay,” he said. “You can leave, but I’m keeping your bag.”

I was speechless. My bag had both my work computer and my personal computer in it. The only way for me to get it back from him would be to snatch it back, at which point he could simply claim that I had assaulted him. I was trapped.

While we waited for the police to arrive, I took my phone and quickly tried to call my parents to let them know what was happening. Unfortunately, my mom’s voicemail was full, and my dad had never even set his up.

“Hey, what’s he doing?” One of the TSA agents had noticed I was touching my phone. “It’s probably fine; he’s leaving anyway,” another said.

The cops arrived a few minutes later, spoke with the TSA agents for a moment, and then came over and gave me one last chance to submit to the private examination. “Otherwise, we have to escort you out of the building.” I asked him if he could be present while the TSA agent was patting me down.

“No,” he explained, “because when we pat people down, it’s to lock them up.”

I only realized the significance of that explanation later. At this point, I didn’t particularly want to miss my flight. Foolishly, I said, “Fine, I’ll do it.”

The TSA agents and police escorted me to a holding room, where they patted me down again – this time using the front of their hands as they passed down the front of my pants. While they patted me down, they asked me some basic questions.

“What’s the purpose of your travel?”

“Personal,” I responded, (as opposed to business).

“Are you traveling with anybody?”

“My parents are on their way to LA right now; I’m meeting them there.”

“How long is your trip?”

“Ten days.”

“What will you be doing?”

Mentally, I sighed. There wasn’t any other way I could answer this next question.

“We’ll be visiting some temples.” He raised his eyebrow, and I explained that the next week was a religious holiday, and that I was traveling to LA to observe it with my family.

After patting me down, they swabbed not only their hands, but also my backpack, shoes, wallet, and belongings, and then walked out of the room to put it through the machine again. After more than five minutes, I started to wonder why they hadn’t said anything, so I asked the police officer who was guarding the door. He called over the TSA agent, who told me,

“You’re still setting off the alarm. We need to call the explosives specialist”.

I waited for about ten minutes before the specialist showed up. He walked in without a word, grabbed the bins with my possessions, and started to leave. Unlike the other agents I’d seen, he wasn’t wearing a uniform, so I was a bit taken aback.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“I’m running it through the x-ray again,” he snapped. “Because I can. And I’m going to do it again, and again, until I decide I’m done”. He then asked the TSA agents whether they had patted me down. They said they had, and he just said, “Well, try again”, and left the room. Again I was told to stand with my legs apart and my hands extended horizontally while they patted me down all over before stepping outside.

The explosives specialist walked back into the room and asked me why my clothes were testing positive for explosives. I told him, quite truthfully, “I don’t know.” He asked me what I had done earlier in the day.

“Well, I had to pack my suitcase, and also clean my apartment.”

“And yesterday?”

“I moved my stuff from my old apartment to my new one”.

“What did you eat this morning?”

“Nothing,” I said. Only later did I realize that this made it sound like I was fasting, when in reality, I just hadn’t had breakfast yet.

“Are you taking any medications?”

The other TSA agents stood and listened while the explosives specialist and asked every medication I had taken “recently”, both prescription and over-the-counter, and asked me to explain any medical conditions for which any prescription medicine had been prescribed. Even though I wasn’t carrying any medication on me, he still asked for my complete “recent” medical history.

“What have you touched that would cause you to test positive for certain explosives?”

“I can’t think of anything. What does it say is triggering the alarm?” I asked.

“I’m not going to tell you! It’s right here on my sheet, but I don’t have to tell you what it is!” he exclaimed, pointing at his clipboard.

I was at a loss for words. The first thing that came to my mind was, “Well, I haven’t touched any explosives, but if I don’t even know what chemical we’re talking about, I don’t know how to figure out why the tests are picking it up.”

He didn’t like this answer, so he told them to run my belongings through the x-ray machine and pat me down again, then left the room.

I glanced at my watch. Boarding would start in fifteen minutes, and I hadn’t even had anything to eat. A TSA officer in the room noticed me craning my neck to look at my watch on the table, and he said, “Don’t worry, they’ll hold the flight.”

As they patted me down for the fourth time, a female TSA agent asked me for my baggage claim ticket. I handed it to her, and she told me that a woman from JetBlue corporate security needed to ask me some questions as well. I was a bit surprised, but agreed. After the pat-down, the JetBlue representative walked in and cooly introduced herself by name.

She explained, “We have some questions for you to determine whether or not you’re permitted to fly today. Have you flown on JetBlue before?”

“Yes”

“How often?”

“Maybe about ten times,” I guessed.

“Ten what? Per month?”

“No, ten times total.”

She paused, then asked,

“Will you have any trouble following the instructions of the crew and flight attendants on board the flight?”

“No.” I had no idea why this would even be in doubt.

“We have some female flight attendants. Would you be able to follow their instructions?”

I was almost insulted by the question, but I answered calmly, “Yes, I can do that.”

“Okay,” she continued, “and will you need any special treatment during your flight? Do you need a special place to pray on board the aircraft?”

Only here did it hit me.

“No,” I said with a light-hearted chuckle, trying to conceal any sign of how offensive her questions were. “Thank you for asking, but I don’t need any special treatment.”

She left the room, again, leaving me alone for another ten minutes or so. When she finally returned, she told me that I had passed the TSA’s inspection. “However, based on the responses you’ve given to questions, we’re not going to permit you to fly today.”

I was shocked. “What do you mean?” were the only words I could get out.

“If you’d like, we’ll rebook you for the flight tomorrow, but you can’t take the flight this afternoon, and we’re not permitting you to rebook for any flight today.”

I barely noticed the irony of the situation – that the TSA and NYPD were clearing me for takeoff, but JetBlue had decided to ground me. At this point, I could think of nothing else but how to inform my family, who were expecting me to be on the other side of the country, that I wouldn’t be meeting them for dinner after all. In the meantime, an officer entered the room and told me to continue waiting there. “We just have one more person who needs to speak with you before you go.” By then, I had already been “cleared” by the TSA and NYPD, so I couldn’t figure out why I still needed to be questioned. I asked them if I could use my phone and call my family.

“No, this will just take a couple of minutes and you’ll be on your way.” The time was 12.35.

He stepped out of the room – for the first time since I had been brought into the cell, there was no NYPD officer guarding the door. Recognizing my short window of opportunity, I grabbed my phone from the table and quickly texted three of my local friends – two who live in Brooklyn, and one who lives in Nassau County – telling them that I had been detained by the TSA and that I couldn’t board my flight. I wasn’t sure what was going to happen next, but since nobody had any intention of reading me my Miranda rights, I wanted to make sure people knew where I was.

After fifteen minutes, one of the police officers marched into the room and scolded, “You didn’t tell us you have a checked bag!” I explained that I had already handed my baggage claim ticket to a TSA agent, so I had in fact informed someone that I had a checked bag. Looking frustrated, he turned and walked out of the room, without saying anything more.

After about twenty minutes, another man walked in and introduced himself as representing the FBI. He asked me many of the same questions I had already answered multiple times – my name, my address, what I had done so far that day. etc.

He then asked, “What is your religion?”

“I’m Hindu.”

“How religious are you? Would you describe yourself as ‘somewhat religious’ or ‘very religious’?”

I was speechless from the idea of being forced to talk about my the extent of religious beliefs to a complete stranger. “Somewhat religious”, I responded.

“How many times a day do you pray?” he asked. This time, my surprise must have registered on my face, because he quickly added, “I’m not trying to offend you; I just don’t know anything about Hinduism. For example, I know that people are fasting for Ramadan right now, but I don’t have any idea what Hindus actually do on a daily basis.”

I nearly laughed at the idea of being questioned by a man who was able to admit his own ignorance on the subject matter, but I knew enough to restrain myself. The questioning continued for another few minutes. At one point, he asked me what cleaning supplies I had used that morning.

“Well, some window cleaner, disinfectant -” I started, before he cut me off.

“This is important,” he said, sternly. “Be specific.” I listed the specific brands that I had used.

Suddenly I remembered something: the very last thing I had done before leaving was to take the bed sheets off of my bed, as I was moving out. Since this was a dorm room, to guard against bedbugs, my dad (a physician) had given me an over-the-counter spray to spray on the mattress when I moved in, over two months previously. Was it possible that that was still active and triggering their machines?

“I also have a bedbug spray,” I said. “I don’t know the name of it, but I knew it was over-the-counter, so I figured it probably contained permethrin.” Permethrin is an insecticide, sold over-the-counter to kill bed bugs and lice.

“Perm-what?” He asked me to spell it.

After he wrote it down, I asked him if I could have something to drink. “I’ve been here talking for three hours at this point,” I explained. “My mouth is like sandpaper”. He refused, saying

“We’ll just be a few minutes, and then you’ll be able to go.”

“Do you have any identification?” I showed him my drivers license, which still listed my old address. “You have nothing that shows your new address?” he exclaimed.

“Well, no, I only moved there on Thursday.”

“What about the address before that?”

“I was only there for two months – it was temporary housing for work”. I pulled my NYU ID out of my wallet. He looked at it, then a police officer in the room took it from him and walked out.

“What about any business cards that show your work address?” I mentally replayed my steps from the morning, and remembered that I had left behind my business card holder, thinking I wouldn’t need it on my trip.

“No, I left those at home.”

“You have none?”

“Well, no, I’m going on vacation, so I didn’t refill them last night.” He scoffed. “I always carry my cards on me, even when I’m on vacation.” I had no response to that – what could I say?

“What about a direct line at work? Is there a phone number I can call where it’ll patch me straight through to your voicemail?”

“No,” I tried in vain to explain. “We’re a tech company; everyone just uses their cell phones”. To this day, I don’t think my company has a working landline phone in the entire office – our “main line” is a virtual assistant that just forwards calls to our cell phones. I offered to give him the name and phone number of one of our venture partners instead, which he reluctantly accepted.

Around this point, the officer who had taken my NYU ID stormed into the room.

“They put an expiration sticker on your ID, right?” I nodded. “Well then why did this ID expire in 2010?!” he accused.

I took a look at the ID and calmly pointed out that it said “August 2013” in big letters on the ID, and that the numbers “8/10” meant “August 10th, 2013”, not “August, 2010”. I added, “See, even the expiration sticker says 2013 on it above the date”. He studied the ID again for a moment, then walked out of the room again, looking a little embarrassed.

The FBI agent resumed speaking with me. “Do you have any credit cards with your name on them?” I was hesitant to hand them a credit card, but I didn’t have much of a choice. Reluctantly, I pulled out a credit card and handed it to him. “What’s the limit on it?” he said, and then, noticing that I didn’t laugh, quickly added, “That was a joke.”

He left the room, and then a series of other NYPD and TSA agents came in and started questioning me, one after the other, with the same questions that I’d already answered previously. In between, I was left alone, except for the officer guarding the door.

At one point, when I went to the door and asked the officer when I could finally get something to drink, he told me, “Just a couple more minutes. You’ll be out of here soon.”

“That’s what they said an hour ago,” I complained.

“You also said a lot of things, kid,” he said with a wink. “Now sit back down”.

I sat back down and waited some more. Another time, I looked up and noticed that a different officer was guarding the door. By this time, I hadn’t had any food or water in almost eighteen hours. I could feel the energy draining from me, both physically and mentally, and my head was starting to spin. I went to the door and explained the situation the officer. “At the very least, I really need something to drink.”

“Is this a medical emergency? Are you going to pass out? Do we need to call an ambulance?” he asked, skeptically. His tone was almost mocking, conveying more scorn than actual concern or interest.

“No,” I responded. I’m not sure why I said that. I was lightheaded enough that I certainly felt like I was going to pass out.

“Are you diabetic?”

“No,” I responded.

Again he repeated the familiar refrain. “We’ll get you out of here in a few minutes.” I sat back down. I was starting to feel cold, even though I was sweating – the same way I often feel when a fever is coming on. But when I put my hand to my forehead, I felt fine.

One of the police officers who questioned me about my job was less-than-familiar with the technology field.

“What type of work do you do?”

“I work in venture capital.”

“Venture Capital – is that the thing I see ads for on TV all the time?” For a moment, I was dumbfounded – what venture capital firm advertises on TV? Suddenly, it hit me.

“Oh! You’re probably thinking of Capital One Venture credit cards.” I said this politely and with a straight face, but unfortunately, the other cop standing in the room burst out laughing immediately. Silently, I was shocked – somehow, this was the interrogation procedure for confirming that I actually had the job I claimed to have.

Another pair of NYPD officers walked in, and one asked me to identify some landmarks around my new apartment. One was, “When you’re facing the apartment, is the parking on the left or on the right?” I thought this was an odd question, but I answered it correctly. He whispered something in the ear of the other officer, and they both walked out.

The onslaught of NYPD agents was broken when a South Asian man with a Homeland Security badge walked in and said something that sounded unintelligible. After a second, I realized he was speaking Hindi.

“Sorry, I don’t speak Hindi.”

“Oh!” he said, noticeably surprised at how “Americanized” this suspect was. We chatted for a few moments, during which time I learned that his family was Pakistani, and that he was Muslim, though he was not fasting for Ramadan. He asked me the standard repertoire of questions that I had been answering for other agents all day.

Finally, the FBI agent returned.

“How are you feeling right now?” he asked. I wasn’t sure if he was expressing genuine concern or interrogating me further, but by this point, I had very little energy left.

“A bit nauseous, and very thirsty.”

“You’ll have to understand, when a person of your… background walks into here, travelling alone, and sets off our alarms, people start to get a bit nervous. I’m sure you’ve been following what’s been going on in the news recently. You’ve got people from five different branches of government all in here – we don’t do this just for fun.”

He asked me to repeat some answers to questions that he’d asked me previously, looking down at his notes the whole time, then he left. Finally, two TSA agents entered the room and told me that my checked bag was outside, and that I would be escorted out to the ticketing desks, where I could see if JetBlue would refund my flight.

It was 2:20PM by the time I was finally released from custody. My entire body was shaking uncontrollably, as if I were extremely cold, even though I wasn’t. I couldn’t identify the emotion I was feeling. Surprisingly, as far as I could tell, I was shaking out of neither fear nor anger – I felt neither of those emotions at the time. The shaking motion was entirely involuntary, and I couldn’t force my limbs to be still, no matter how hard I concentrated.

In the end, JetBlue did refund my flight, but they cancelled my entire round-trip ticket. Because I had to rebook on another airline that same day, it ended up costing me about $700 more for the entire trip. Ironically, when I went to the other terminal, I was able to get through security (by walking through the millimeter wave machines) with no problem.

I spent the week in LA, where I was able to tell my family and friends about the entire ordeal. They were appalled by the treatment I had received, but happy to see me safely with them, even if several hours later.

I wish I could say that the story ended there. It almost did. I had no trouble flying back to NYC on a red-eye the next week, in the wee hours of August 12th. But when I returned home the next week, opened the door to my new apartment, and looked around the room, I couldn’t help but notice that one of the suitcases sat several inches away from the wall. I could have sworn I pushed everything to the side of the room when I left, but I told myself that I may have just forgotten, since I was in a hurry when I dropped my bags off.

When I entered my bedroom, a chill went down my spine: the photograph on my wall had vanished. I looked around the room, but in vain. My apartment was almost completely empty; there was no wardrobe it could have slipped under, even on the off-chance it had fallen.

To this day, that photograph has not turned up. I can’t think of any “rational” explanation for it. Maybe there is one. Maybe a burglar broke into my apartment by picking the front door lock and, finding nothing of monetary value, took only my picture. In order to preserve my peace-of-mind, I’ve tried to convince myself that that’s what happened, so I can sleep comfortably at night.

But no matter how I’ve tried to rationalize this in the last week and a half, nothing can block out the memory of the chilling sensation I felt that first morning, lying on my air mattress, trying to forget the image of large, uniformed men invading the sanctuary of my home in my absence, wondering when they had done it, wondering why they had done it.

In all my life, I have only felt that same chilling terror once before – on one cold night in September twelve years ago, when I huddled in bed and tried to forget the terrible events in the news that day, wondering why they they had happened, wondering whether everything would be okay ever again.

Update: this has been picked up by Village Voice and Gawker and JetBlue has apologized over twitter.

Staples.com rips off poor people; let’s take control of our online personas

You’ve probably heard rumors about this here and there, but the Wall Street Journal convincingly reported yesterday that websites charge certain people more for the exact thing.

Specifically, poor people were more likely to pay more for, say, a stapler from Staples.com than richer people. Home Depot and Lowes does the same for their online customers, and Discover and Capitol One make different credit card offers to people depending on where they live (“hey, do you live in a PayDay lender neighborhood? We got the card for you!”).

They got pretty quantitative for Staples.com, and did tests to determine the cost. From the article:

It is possible that Staples’ online-pricing formula uses other factors that the Journal didn’t identify. The Journal tested to see whether price was tied to different characteristics including population, local income, proximity to a Staples store, race and other demographic factors. Statistically speaking, by far the strongest correlation involved the distance to a rival’s store from the center of a ZIP Code. That single factor appeared to explain upward of 90% of the pricing pattern.

If anyone’s ever seen a census map, race is highly segregated by ZIP code, and my guess is we’d see pretty high correlations along racial lines as well, although they didn’t mention it in the article except to say that explicit race-related pricing is illegal. The article does mentions that things get more expensive in rural areas, which are also poorer, so there’s that acknowledged correlation.

But wait, how much of a price difference are we talking about? From the article:

Prices varied for about a third of the more than 1,000 randomly selected Staples.com products tested. The discounted and higher prices differed by about 8% on average.

In other words, a really non-trivial amount.

The messed up thing about this, or at least one of them, is that we could actually have way more control over our online personas than we think. It’s invisible to us, typically, so we don’t think about our cookies and our displayed IP addresses. But we could totally manipulate these signatures to our advantage if we set our minds to it.

Hackers, get thyselves to work making this technology easily available.

For that matter, given the 8% difference, there’s money on the line so some straight-up capitalist somewhere should be meeting that need. I for one would be willing to give someone a sliver of the amount saved every time they manipulated my online persona to save me money. You save me $1.00, I’ll give you a dime.

Here’s my favorite part of this plan: it would be easy for Staples to keep track of how much people are manipulating their ZIP codes. So if Staples.com infers a certain ZIP code for me to display a certain price, but then in check-out I ask them to send the package to a different ZIP code, Staples will know after-the-fact that I fooled them. But whatever, last time I looked it didn’t cost more or less to send mail to California or wherever than to Manhattan [Update: they do charge differently for packages, though. That’s the only differential in cost I think is reasonable to pay].

I’d love to see them make a case for how this isn’t fair to them.

You people freaking rock: Occupy Finance officially funded

Yesterday I told people about the book my Occupy group is coming out with. I said I needed $350 to cover the printing costs, and I asked for small donations. Anything beyond that means more books get printed (still true!).

Today I’m super happy to say I’ve collected pledges summing to $596, which means we’ll be able to make many more copies of the book than expected, and distribute them to many more people. And it’s really been a group effort: 15 different people pitched in with amounts between $20 and $100. It means they’re all part of the project.

What was particularly awesome for me about the “Crappy Kickstarter” was the personal emails I got with words of encouragement for the blog and the book.

You guys seriously rock, and I feel very lucky to be your friend. Thanks!

Occupy Finance, the book: announcement and fundraising (#OWS)

Members of the Alt Banking Occupy group have been hard at work recently writing a book which we call Occupy Finance. Our blog for the book is here. It’s a work in progress but we’re planning to give away 1,000 copies of the book on September 17th, the 2nd anniversary of the Occupation of Zuccotti Park.

We’re modeling it after another book which was put out last year by Strike Debt called the Debt Resistor’s Operations Manual, which I blogged about here when it came out.

Crappy Kickstarter

I want to tell you more about our book, which we’re writing by committee, but I did want to mention that in order to get the first 1,000 copies printed by September 17th, we’ll need altogether $2,500, and so far we’ve collected $2,150 from the various contributors, editors, and their friends. So we need to collect $350 at this point. If we get more then we’ll print more.

If you’d like to help us towards the last $350, we’d appreciate it – and I’ll even send you a copy of the book afterwards. But please don’t send anything you don’t want to give away, I can’t promise you some kind of formal proof of your contribution for tax purposes. This is Occupy after all, we suck at money. Consider this a crappy version of Kickstarter.

Anyway if you want to help out, send me a personal email to arrange it: cathy.oneil at gmail. I’ll basically just tell you to send me a personal check, since I’m the one fronting the money.

Audience and Mission

The mission of the book, like the mission of the Alt Banking group, is to explain the financial system and its dysfunction in plain English and to offer suggestions for how to think about it and what we can do to improve it.

The audience for this book is the 99% who are Occupy-friendly or at least Occupy-inquisitive. Specifically, we want people who know there’s something wrong, but don’t have the background to articulate what it is, to have a reference to help them define their issues. We want to give them ammunition at the water cooler.

What’s in the book?

After a stirring introduction, the book is divided into three basic parts: The Real Life Impact of Financialization, How We Got Here, and Things to do. I’ve got links below.

Keep in mind things are still in flux and will be changed, sometimes radically, before the final printing. In particular we’re actually using DropBox for most of our edits so the links below aren’t final versions (but will be eventually). Even so, the content below will give you a good idea of what we have in mind, and if you have comments or suggestions, please do tell us, thanks!

Our table of contents is as follows, and the available chapters have associated links:

Introduction: Fighting Our Way Out of the Financial Maze

The Real Life Impact of Financialization

- Heads They Win, Tails We Lose: Real Life Impact of Financialization on the 99%

- The bailout: it didn’t work, it’s still going on, and it’s making things worse

How We Got Here

- What Banks Do

- Impact of Deregulation

- The top ten financial outrages

- The muni bond industry and the 99%

Things to Do

Update: I’ve got $225 $301 pledged so far! You people rock!!

When big data goes bad in a totally predictable way

Three quick examples this morning in the I-told-you-so category. I’d love to hear Kenneth Neil Cukier explain how “objective” data science is when confronted with this stuff.

1. When an unemployed black woman pretends to be white her job offers skyrocket (Urban Intellectuals, h/t Mike Loukides). Excerpt from the article: “Two years ago, I noticed that Monster.com had added a “diversity questionnaire” to the site. This gives an applicant the opportunity to identify their sex and race to potential employers. Monster.com guarantees that this “option” will not jeopardize your chances of gaining employment. You must answer this questionnaire in order to apply to a posted position—it cannot be skipped. At times, I would mark off that I was a Black female, but then I thought, this might be hurting my chances of getting employed, so I started selecting the “decline to identify” option instead. That still had no effect on my getting a job. So I decided to try an experiment: I created a fake job applicant and called her Bianca White.”

2. How big data could identify the next felon – or blame the wrong guy (Bloomberg). From the article: “The use of physical characteristics such as hair, eye and skin color to predict future crimes would raise ‘giant red privacy flags’ since they are a proxy for race and could reinforce discriminatory practices in hiring, lending or law enforcement, said Chi Chi Wu, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center.”

3. How algorithms magnify misbehavior (the Guardian, h/t Suresh Naidu). From the article: “For one British university, what began as a time-saving exercise ended in disgrace when a computer model set up to streamline its admissions process exposed – and then exacerbated – gender and racial discrimination.”

This is just the beginning, unfortunately.

Ask Aunt Pythia

You know how you sometimes wake up and just feel like the luckiest person in the world? With the awesomest friends and family? And you just wanna go hug everything and everyone?

That is where Aunt Pythia is today, psychically speaking. Aunt Pythia is feeling so good that her usual quarrelsome self is in hiding, and every single piece of her advice is therefore probably useless, but so be it, it feels damn good.

Oh, and one more thing before the worthless drivel revs up: Aunt Pythia has noticed that people close to her don’t enjoy her columns very much at all, possibly because “they get to hear Aunt Pythia’s advice all the time and are frankly sick of it.”

So if you’re someone who does like Aunt Pythia’s advice column, please sing it loud and clear! The best way to express your AP love, of course, is by posing your very own ethical dilemma at the bottom of this column, so Auntie P has something to do next Saturday (she’s running low).

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m 20 years old, very much a virgin, dating my boy for 2 and a half years and when it comes to the question of having sex, we have had oral sex but not intercourse as we decided it would be best to wait since no one knows about the future. Am i missing out on too much if i wait till i get married in seven years from now (which is a long time of course)?

Strong Headed

Dear Strong,

A few things. First of all, it disturbs me that you are planning so far ahead that you’ve already chosen 7 years as the amount of time before getting married. Where did that come from? That’s a lifetime of adulthood from the point of view of a 20-year-old. Who knows what country you’ll live in in 7 years, or what kind of job you’ll have.

Next, if you pair that with your alleged reason for not getting laid which is “since no one knows about the future”, it makes even less sense that you’re willing to wait for some arbitrary and enormous amount of time before getting down to the business of doing what you supposedly want with your life.

About that – do you actually want to get married? Well I’m not saying you should or shouldn’t, but I am saying you should figure out what you want and do it, and don’t ask other people, and don’t make plans based on random external rules.

Finally, the sex thing. I’m never going to understand why people come to me for sex advice since the one and only thing I ever ever say is “go for it!”.

Unless… unless they are somehow using me as a way of making an excuse to themselves for doing something they actually want to do already – I’m a proxy moral authority, perhaps? It’s happened.

So, if I’m playing that role, then by all means go do what you already want to do, but my real advice is to be your own moral authority next time. Your life, go live it.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

When will we see the space elevator in operation?

Carbon diox

Dear Carbon,

Seriously! I am super impatient for that myself. And I appreciate how your question somehow implies that it’s all set to go but nobody’s turned it on yet.

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This isn’t a question for AP, but instead a suggestion for a MB post: what are your thoughts on the Colin McGinn case?

Academic Philosophy

Dear Academic,

Tough shit, it came through Aunt Pythia’s feed so that’s what you get.

So actually I had to google Colin McGinn, since I hadn’t heard about it, and I supplied the link I reached above, so if that’s not representative then I apologize.

In any case I’ll comment based on that article.

First, it’s not a huge surprise to me, to hear of an academic discipline and culture filled with bullies, which sometime extends to sexual predation, and that women are excluded from that field for both the bullying reason and the sexual predation reason. This is super consistent with having a crappy and overly aggressive culture.

I’ve never entered the academic discipline of philosophy myself, but something that scares me about the field is the idea that you rely on your intelligence to make your point, rather than any outside evidence, like you might in science, or outside logical fact, like you might in mathematics.

In other words, I like math because it’s filled with people who know how to admit they’re wrong (some subfields of math are better than others at this). I like experimental science because, when they claim something will happen and it doesn’t happen, they have to revise their theory. I don’t like philosophy because arguments are slippery, like this one that Colin McGinn gave as an explanation for sending aggressive sexual requests to his first year graduate student:

Mr. McGinn said that “the ‘3 times’ e-mail,” as he referred to it, was not an actual proposal. “There was no propositioning,” he said in the interview. Properly understanding another e-mail to the student that included the crude term for masturbation, he added later via e-mail, depended on a distinction between “logical implication and conversational implicature.”

“Remember that I am a philosopher trying to teach a budding philosopher important logical distinctions,” he said.

Yuck!

I’m not saying the field can’t recover, but until they work on it, I won’t feel sorry for the fact that women are under-represented.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This question stems from your response from one of last week’s questions (the last one):

“The truth is, once you’ve been politicized and sensitized to the evil that organizations do or are involved in, you start to see it everywhere. Or if not everywhere, at least most places where you get paid.”

I have certainly found this to be true, as a physics student with a long career in retail to help support the student-ing.

Does it get better? Or easier to accept and harder to maintain some abstract idealism? Must this perspective in some way be balanced? I have dreams of grad school and research, but I wonder if even then it will be true that organizations are weird things that involve people behaving in unfortunate ways.

Reading Chomsky doesn’t seem to help.

-rage against the machine

Dear rage,

Great question! I think it does get better, and although it’s hard to maintain a long list of personal heroes when you keep looking behind the curtain and learning too much, I’ve found it’s not impossible to maintain idealism itself. It’s something you need to nurture, though, for sure, and it takes patience – you have to play the long game.

In other words, some people are aware of the hypocrisies and evils of the world and decide it’s too big to deal with so they figure they’ll just ignore it. Other people see that stuff and try to do everything, and they burn out. Other people just don’t see it at all.

I think a middle ground is good: try to do what you can, and make that a long term goal, and have standards you actually live by that help you make decisions. If, for example, you feel complicit in something you consider evil, then get the fuck out, even if it means quitting your job. You’ll get another job, I’m guessing, especially with a physics background and the ability to read Chomsky.

One thing I want to stress: don’t depend on a single person or a couple of persons to embody the ideals that you care about, because they’ll probably end up disappointing you at some point, and that’s not a great reason to throw in the towel. Instead, write up an internal list of your ideals, they’ll never let you down.

Good luck!

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

What’s the difference between big data and business analytics?

I offend people daily. People tell me they do “big data” and that they’ve been doing big data for years. Their argument is that they’re doing business analytics on a larger and larger scale, so surely by now it must be “big data”.

No.

There’s an essential difference between true big data techniques, as actually performed at surprisingly few firms but exemplified by Google, and the human-intervention data-driven techniques referred to as business analytics.

No matter how big the data you use is, at the end of the day, if you’re doing business analytics, you have a person looking at spreadsheets or charts or numbers, making a decision after possibly a discussion with 150 other people, and then tweaking something about the way the business is run.

If you’re really doing big data, then those 150 people probably get fired laid off, or even more likely are never hired in the first place, and the computer is programmed to update itself via an optimization method.

That’s not to say it doesn’t also spit out monitoring charts and numbers, and it’s not to say no person takes a look every now and then to make sure the machine is humming along, but there’s no point at which the algorithm waits for human intervention.

In other words, in a true big data setup, the human has stepped outside the machine and lets the machine do its thing. That means, of course, that it takes way more to set up that machine in the first place, and probably people make huge mistakes all the time in doing this, but sometimes they don’t. Google search got pretty good at this early on.

So with a business analytics set up we might keep track of the number of site visitors and a few sales metrics so we can later try to (and fail to) figure out whether a specific email marketing campaign had the intended effect.

But in a big data set-up it’s typically much more microscopic and detail oriented, collecting everything it can, maybe 1,000 attributed of a single customer, and figuring out what that guy is likely to do next time, how much they’ll spend, and the magic question, whether there will even be a next time.

So the first thing I offend people about is that they’re not really part of the “big data revolution”. And the second thing is that, usually, their job is potentially up for grabs by an algorithm.

Are small businesses less corrupt?

I’ve had a bit of a bee in my bonnet for a while now about how we’re expected to assume that big is better when it comes to businesses. It started when I wrote this post about how women CEO’s are considered unambitious for wanting their businesses small enough to manage.

In other words, there might be some selection bias in my next few examples, so full disclosure. And yet I’ll give them to you anyhow.

First, an example of a extra corruption in a large business. I recently met HSBC whistleblower Everett Stern, profiled by Matt Taibbi here. He told me about the stuff he’d seen going on in HSBC, whereby there was rampant money laundering for terrorists (his region of interest was the Middle East). When asked why nobody’s gotten into trouble, his answer was simple: too big to jail.

Or if you’re not convinced too-big-to-jail is a real problem, just look at the state of the London Whale case: two low-level indictments and basically nothing else for lying to regulators and changing their books to pretend they had less losses.

Next, in the category of it’s-actually-good-to-be-small, you might have seen this tiny New York Times article about two email provider companies which folded rather than giving up their customers’ data. Can anyone imagine Facebook or Google doing that? The big business version of this is “hiring really fancy lawyers” I guess, but it doesn’t seem to work as well.

I’m wondering if this generalizes: in general, can we claim that small companies have less to lose and therefore have more ethics?

It’s certainly true that, at the very least, small companies live and die based on the relationship of trust that they have with their customers, so to the extent that their customers have ethics, then the companies need to consider them. Larger firms, on the other hand, can hire PR firms to fix their image after the fact if things go wrong.

What do you think? Is there research on this?

Update: First of all, sure there’s research on this, if you think accounting fraud is a good proxy for corruption. Second, now that I think about it, small companies having less to lose can also be a super bad thing, if you want to get away with bad shit. And for that matter, if you consider little subsidiaries of big companies as “small companies”, or for that matter McDonalds’ franchises, they already are.

Also, as a friend of mine pointed out over email, small companies are often inefficient (so: no unionization) and are used as a political baby seal to justify all sorts of crappy policies, as we’ve of course seen.

How to be a pickup artist, Silicon Valley style

You know that feeling you get when you’re reading an disembodied article on the web and it’s just so ridiculous, you get the creeping sensation that it’s either from The Onion or the Borowitz Report?

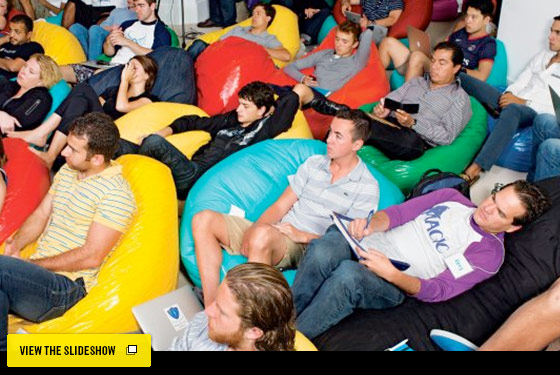

That is, I would suggest, how you’re going to feel when you read this article about a school for Silicon Valley style entrepreneurship (hat tip Peter Woit). Even just the name of the school – the Draper University of Heroes – feels like an Onion article, never mind the visuals:

So, what do these young people learn do to become douchebag heros? Here’s what:

- They pledge allegiance every morning to their personal brands,

- They submit to a full two days of coding and excel lessons,

- Then they get down to the real work of sun tanning by the pool and go-kart racing,

- They hang out with VC Tim Draper, an investor in Tesla (the new conspicuous consumption choice among pseudo-progressive capitalists, as I learned at FOO),

- They read books, or at least they own books, including Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, The Wall Street MBA, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead,

- and all this for just $9,500 for an eight week program!

How does it end? From the article:

In lieu of diplomas, Draper U. students receive masks and capes printed with their superhero nicknames and are instructed to jump on each of a series of three small trampolines placed in a line in front of them. While bouncing from trampoline to trampoline, they’re told to shout, “Up, up, and away!” Then they assemble for a group photo.

“The world needs more heroes,” Draper says. “And it just got 40 more of them!”

Here’s the thing. It’s no accident that there are way more men than women here. This school is very similar in design and intent to the society built by Neil Strauss, who wrote The Game and taught a bunch of guys how to pick up “hot” women for sex – Aunt Pythia discussed it here.

Why do I say that? Because it’s fundamentally a confidence-boosting ritual, where a bunch of guys convince themselves that their prospects are good, their goals are attainable, their narcissistic world view is honorable, and it’s just a question of acquiring the right magic tricks to entrap their prey. It just happens to be about money instead of sex in this case.

There is a difference, of course. Whereas the pick up artists only needed to trick drunk women for a few hours in order to sleep with them, these “Silicon Valley Heroes” have to trick way more people for way longer that they should get investment. That doesn’t make it impossible for something like this to work, though, just harder.

Larry Summers and the Lending Club

So here’s something potential Fed Chair Larry Summers is involved with, a company called Lending Club, which creates a money lending system that cuts out the middle man banks.

Specifically, people looking for money come to the site and tell their stories, and try to get loans. The investors invest in whichever loans look good to them, for however much money they want. For a perspective on the risks and rewards of this kind of peer-to-peer lending operation, look at this Wall Street Journal article which explains things strictly from the investor’s point of view.

A few red flags go up for me as I learn more about Lending Club.

First, from this NYTimes article, “The company [Lending Club] itself is not regulated as a bank. But it has teamed up with a bank in Utah, one of the states that allows banks to charge high interest rates, and that bank is overseen by state regulators and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.”

I’m not sure how the FDIC is involved exactly, but the Utah connection is good for something, namely allowing high interest rates. According to the same article, 37% of loans are for APR’s of between 19% and 29%.

Next, Summers is referred to in that article as being super concerned about the ability for the consumers to pay back the loans. But I wonder how someone is supposed to be both desperate enough to go for a 25% APR loan and also able to pay back the money. This sounds like loan sharking to me.

Probably what bothers me most though is that Lending Club, in addition to offering credit scores and income when they have that information, also scores people asking for loans with a proprietary model which is, as you guessed it, unregulated. Specifically, if it’s anything like ZestFinance, could use signals more correlated to being uneducated and/or poor than to the willingness or ability to pay back loans.

By the way, I’m not saying this concept is bad for everyone- there are probably winners on the side of the loanees, and it might be possible that they get a loan they otherwise couldn’t get or they get better terms than otherwise or a more bespoke contract than otherwise. I’m more worried about the idea of this becoming the new normal of how money changes hands and how that would affect people already squeezed out of the system.

I’d love your thoughts.

Finance and open source

I want to bring up two quick topics this morning I’ve been mulling over lately which are both related to this recent post by Economist Rajiv Sethi from Barnard (h/t Suresh Naidu), who happened to be my assigned faculty mentor when I was an assistant prof there. I have mostly questions and few answers right now.

In his post, Sethi talks about former computer nerd for Goldman Sachs Sergey Aleynikov and his trial, which was chronicled by Michael Lewis recently. See also this related interview with Lewis, h/t Chris Wiggins.

I haven’t read Lewis’s piece yet, only his interview and Sethi’s reaction. But I can tell it’ll be juicy and fun, as Lewis usually is. He’s got a way with words and he’s bloodthirsty, always an entertaining combination.

So, the two topics.

First off, let’s talk a bit about high frequency trading, or HFT. My first two questions are, who does HFT benefit and what does HFT cost? For both of these, there’s the easy answer and then there’s the hard answer.

Easy answer for HFT benefitting someone: primarily the people who make loads of money off of it, including the hardware industry and the people who get paid to drill through mountains with cables to make connections between Chicago and New York faster.

Secondarily, market participants whose fees have been lowered because of the tight market-making brought about by HFT, although that savings may be partially undone by the way HFT’ers operate to pick off “dumb money” participants. After all, you say market making, I say arbing. Sorting out the winners, especially when you consider times of “extreme market conditions”, is where it gets hard.

Easy answer for the costs of HFT is for the companies that invest in IT and infrastructure and people to do the work, although to be sure they wouldn’t be willing to make that investment if they didn’t expect it to pay off.

A harder and more complete answer would involve how much risk we take on as a society when we build black boxes that we don’t understand and let them collide with each other with our money, as well as possibly a guess at what those people and resources now doing HFT might be doing otherwise.

And that brings me to my second topic, namely the interaction between the open source community and the finance community, but mostly the HFTers.

Sethi said it well (Cathy: see bottom of this for an update) this way in his post:

Aleynikov relied routinely on open-source code, which he modified and improved to meet the needs of the company. It is customary, if

not mandatory(Cathy: see bottom of this for an update) for these improvements to be released back into the public domain for use by others. But his attempts to do so were blocked:

Serge quickly discovered, to his surprise, that Goldman had a one-way relationship with open source. They took huge amounts of free software off the Web, but they did not return it after he had modified it, even when his modifications were very slight and of general rather than financial use. “Once I took some open-source components, repackaged them to come up with a component that was not even used at Goldman Sachs,” he says. “It was basically a way to make two computers look like one, so if one went down the other could jump in and perform the task.” He described the pleasure of his innovation this way: “It created something out of chaos. When you create something out of chaos, essentially, you reduce the entropy in the world.” He went to his boss, a fellow named Adam Schlesinger, and asked if he could release it back into open source, as was his inclination. “He said it was now Goldman’s property,” recalls Serge. “He was quite tense. When I mentioned it, it was very close to bonus time. And he didn’t want any disturbances.”

This resonates with my experience at D.E. Shaw. We used lots of python stuff, and as a community were working at the edges of its capabilities (not me, I didn’t do fancy HFT stuff, my models worked at a much longer time frame of at least a few hours between trades).

The urge to give back to the OS community was largely thwarted, when it came up at all, because there was a fear, or at least an argument, that somehow our competition would use it against us, to eliminate our edge, even if it was an invention or tool completely sanitized from the actual financial algorithm at hand.

A few caveats: First, I do think that stuff, i.e. python technology and the like eventually gets out to the open source domain even if people are consistently thwarting it. But it’s incredibly slow compared to what you might expect.

Second, It might be the case that python developers working outside of finance are actually much better at developing good tools for python, especially if they have some interaction with finance but don’t work inside. I’m guessing this because, as a modeler, you have a very selfish outlook and only want to develop tools for your particular situation. In other words, you might have some really weird looking tools if you did see a bunch coming from finance.

Finally, I think I should mention that quite a few people I knew at D.E. Shaw have now left and are actively contributing to the open source community now. So it’s a lagged contribution but a contribution nonetheless, which is nice to see.

Update: from my Facebook page, a discussion of the “mandatoriness” of giving back to the OS community from my brother Eugene O’Neil, super nerd, and friend William Stein, other super nerd:

Eugene O’Neil: the GPL says that if you give someone a binary executable compiled with GPL source code, you also have to provide them free access to all the source code used to generate that binary, under the terms of the GPL. This makes the commercial sale of GPL binaries without source code illegal. However, if you DON’T give anyone outside your organization a binary, you are not legally required to give them the modified source code for the binary you didn’t give them. That being said, any company policy that tries to explicitly PROHIBIT employees from redistributing modified GPL code is in a legal gray area: the loophole works best if you completely trust everyone who has the modified code to simply not want to distribute it.

William Stein: Eugene — You are absolutely right. The “mandatory” part of the quote: “It is customary, if not mandatory, for these improvements to be released back into the public domain for use by others.” from Cathy’s article is misleading. I frequently get asked about this sort of thing (because of people using Sage (http://sagemath.org) for web backends, trading, etc.). I’m not aware of any popular open source license that make it mandatory to give back changes if you use a project internally in an organization (let alone the GPL, which definitely doesn’t). The closest is AGPL, which involves external use for a website. Cathy — you might consider changing “Sethi said it well…”, since I think his quote is misleading at best. I’m personally aware of quite a few people that do use Sage right now who wouldn’t otherwise if Sethi’s statement were correct.

Ask Aunt Pythia

Hey it’s Saturday and unlike last week, I know it! That means it’s time for Aunt Pythia to spew forth her ill-considered advice to thoroughly nice people such as yourself.

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

And please, Submit your question for Aunt Pythia at the bottom of this page!

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a 48-year-old newly single mother of teenagers. I finally have time to date and am seeking the statistically most successful way to meet single, available men. I do not like to hang out in bars and my “sports” interests are ballet and yoga–not anywhere any heterosexual men usually hang out. I do love wine but joining a wine “club” would be prohibitively expensive, and a book club is also not where available men can be found. Do you suggest I take up new activities in my life to meet men? And if so, which ones would maximize my chances in my age group and my proclivity to be introverted? Please do not suggest match.com–it was a disaster.

Thanks,

Statistically Seeking Mr. Right

Dear SSMR,

I suggest you take up a nerd sport, like learning a programming language – python?. Join a python meetup group in your area and go to some meetings and wait for a super nice nerd to show up. Note: super nice nerds might not talk a lot, so you might need to be patient and/or draw them out.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m an incoming senior undergrad CS student at Columbia.

This summer, I’m very fortunate to be working on some very interesting problems in data science, learning a ton, and implementing and testing a lot of models of my own. It’s more research/science type stuff, rather than software engineering, and I really want to continue to do this (while being compensated) after graduation next year.

The problem is, I’ve never once considered grad school (I’m really not an academic type and I love working with real data in real companies). Is it possible for a new graduate to get a research-type data science job, or at least mostly research-type, without a further degree? More importantly, I’d like to work on interesting problems, that hopefully will benefit the greater good, at least in some way.

If so, where do these jobs lie, and how can I get there?

Fledgling Scientist

Dear Fledgling Scientist,

It’s interesting how, at least for you, there’s a disconnect between the desire to be doing abstract research and the desire to be at grad school. What does that say about the reputation of grad school? What does it symbolize to you if not doing abstract research? Would you reconsider that?

Here’s the thing. I’ma be honest with you, most research doesn’t pay for itself. Indeed it’s pretty rare for research to pay off. So companies, especially start-ups that don’t have extra money floating around, will not pay for people to be abstract researchers, even if they’re proven professionals (i.e. they have Ph.D.’s and lots of papers).

Even in my job, where I’m an experienced researcher in math, and to some extent it’s my job to be a researcher in data science, it’s not abstract at all – I’m trying to figure out how to start a business in data science that will create a revenue stream of real cash money.

I don’t want to be completely negative, so here’s an idea for you that doesn’t require grad school. Get a job that pays pretty well but isn’t full time and do research in your spare time. It might not pay off cash-wise but it could very well make you money. And after a while you might decide that getting a Ph.D. would suit you.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

First of all: happy belated birthday!

In a couple of weeks I’m going to be taking part in a really awesome program at my university that brings low-income/first-generation college students to campus for a week to work on a research project with a lab of their choice before starting here in the fall. I get to be their Resident Assistant during this time and help them out with their lab projects/presentations. I’m feeling incredibly excited but also incredibly nervous about staring this! For example, I keep having imaginary conversations with hypothetical students in one or another life-situation with the aim of trying to figure out what’s the best possible advice/consolation I could offer them in that theoretical moment (this is just symptomatic of how math has drilled my brain to think about everything. I’m not actually crazy).

But whenever I overanalyze something to this extent I tend to become aloof and disconnected from the reality of it when it actually happens. It’s really important to me that I DO NOT DO THIS because I would love to be able to keep interacting regularly with these kids once the program finishes and I don’t want them to think of me as that weird guy who shakes his gravelly hands and mumbles whenever they bring up an academic/personal problem that I might *actually* be able to help them with (given on my own crazy and nonlinear experience). So how can I avoid doing this? How can I keep it real? Any other nuggets of wisdom you’d like to offer me going into this would also be greatly appreciated!

Derp dErp deRp derP

Dear Dddd,

Thanks for the birthday wishes! I had a great one.

Let’s see. Your job is to help kids with research projects, and you want to do a good job and keep it real, and you want to keep in touch with them. They’re also low-income/ first-generation college students.

My first piece of advice is to be nice and to articulate very loudly that you’re here to help and you want to make yourself available to them. That is always appreciated by people who don’t know what they’re doing. My next suggestion is to assume they are nerds, here to learn, and want to be challenged as well as to impress. So get ready to be impressed, and be sure to give positive feedback when it’s appropriate. People really love that stuff.

Third, you mention you have had a crazy and non-linear experience yourself. It might help them to know that, to relate to you, because chances are they might have moments of feeling out of place. But I’d wait on telling them until it’s one-on-one and you’ve already established a friendship and mutual respect. For example, it’d be a good time to mention this if they’ve come to you in a panic because they’ve been feeling over their head but know they can rely on you for advice. And also for example, it’d be a bad time to mention this on the first day when they’re all just meeting you, because it’d come across as you not expecting much from them.

Finally, it’s always fun to work with young people, so have a great time! Feed off their energy and they’ll feed off of your wisdom.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I recently finished up a masters in applied mathematics. I also recently left the Air Force to stop being a part of an organization that does awful awful things. I am now trying to find a job that hopefully uses my recent degree and avoids working for an organization that does awful things. Currently this means I am teaching small children to ice skate and play hockey which is great but doesn’t quite fill up the day or have much of any direct connection to math.

I am wondering what I could do and where I could look to avoid being chewed up by the military-industrial complex or other such entity? (see: financial sector) I’ve been looking at teaching jobs and been avoiding the thought of going for a PhD (so far, that bug will bite soon I’m sure), but I wondered if there might be other options I haven’t thought of. Any advice would be greatly appreciated.

Will Math to Feed Book Habit

Dear Will,

Yikes.

The truth is, once you’ve been politicized and sensitized to the evil that organizations do or are involved it, you start to see it everywhere. Or if not everywhere, at least most places where you get paid.

So if you’re dead-set on not being part of that stuff at all, your options are limited. For example, working at Google might not be a good idea for you since we don’t really know what they do. Facebook is pretty much a no fly zone, depending on what it is you have objections to. Start-ups often participate in weird shit in ways they don’t want to acknowledge (and sometimes don’t – you should be on the look-out for a good job at a small start-up in any case).

Here’s my suggestion: do math tutoring. I know people who get paid pretty darn well for math tutoring, especially for wealthy kids. And yes, there are issues around that too, of course, but on the other hand you know exactly what you’re getting yourself into, and you’re pretty much independent. Plus you’ve already shown you can work with kids, so it might be an easy transition. Over time you can start a math tutoring company and run it with no ties to anyone you don’t like.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I was in Penn Station today around 6pm and a guy came up to me and asked me if he could ask me a question. I said okay, and well he first asked me if I spoke English, and then he said he needed money to take the train to Patchogue (which I later looked up costs $12.75). I wasn’t sure what to do, and I just reflexively I guess asked him how much it the fare was and he said 11.75 and well, then I took out my wallet and had 12 bucks so I gave it to him and he thanked me and walked away (I had to catch my own train elsewhere and so I don’t know whether he bought a ticket to patchogue or not).

After he walked away, I felt a bit silly for giving him so much – I could have just said no, but I often have a hard time saying no – and felt like I hadn’t stood up for myself, and had given him the money so that he would go away (I felt threatened/intimated by him because of reasons that aren’t PC to mention; but there were plenty of people around so I didn’t consider myself to be in imminent danger).

At the same time, I tried to make myself feel better by reminding myself that I can’t take any money with me when I die, and that I expect to die with more than 12 bucks in my name, so in the end it doesn’t matter, and maybe he was having a rough time so I perhaps I did my good deed for the day.

On the other hand, giving money away like that just encourages people/panhandlers to ask, maybe it is a scam (btw this would be the second time within the last year I was asked in Penn Station such a question (I said no the previous time but it was a lady that was asking so I didn’t feel threatened), and I’m only in there about once a week) and so sometimes I say no to such requests.

So my question is, what would AP do? (Oh, if it matters, I make $70,000 a year, and have no dependents). And what does MB do when asked by panhandlers for spare change?

Penn $tation

Dear Penn,

First of all, I like that you gave the dude $12 – I’ve been scammed before – plus, I like your “death bed” reasoning as well, it makes sense to me. I don’t think you need to feel weird or ashamed of what you’ve done.

On the other hand, it’s not what I do. I never give scary men money because they’re threatening me, whether they’re black or white, on principle, and I’ve never had a problem with saying no. In fact I almost never give money to strangers at all, except when they’re older women who seem like they’ve been thrown out of mental institutions. Then I often give them $20 bills, and they’re often not even asking for them because they’re so confused.

Since I live and work in New York and commute to work via subway most days, giving money to everyone who asks me for it could actually be bad for my family over time. But that’s not why I don’t do it. Mostly I don’t do it because, having worked in soup kitchens and having read enough about childhood poverty and hunger, I know that the people who need petty cash the most aren’t the ones asking for it in Penn Station. It’s way bigger than that, unfortunately.

I do buy my broke friends stuff, mostly food, and I give money to causes like Fair Foods in Boston that I have a personal connection to and which I think address the immediate needs of poor immigrants and children.

Yours,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

New schwag for the Stacks Project

This just in from zazzle.com: Stacks Project cups and shirts, to celebrate the recent upgrade on Stacks Project viz.

An unflattering yet adorable picture of both me and Johan in Stacks Project t-shirts, new and old. Unfortunately the colors came out too light. You can see we’re both instructing our 11-year-old on how to take a picture and our 4-year-old is squeezing in too. He’s not shy.

Survivorship bias for women in men’s fields

I like this essay written by Annie Gosfield, a self-described “composeress”, which is her word to mean a female composer. She finds it slightly absurd to be singled out for her femaleness. Her overall take on being a woman in a man’s world is refreshing, and resonates with me as a woman in math and technology.

From her essay: