Archive

Join Alt Banking #OWS

I’m really proud of my Occupy group, Alt Banking. We continue to meet every Sunday at Columbia and we welcome new members. I wanted to throw down a few reasons you might consider coming to our meetings.

If you’re interested, please email alt.banking.ows@gmail.com and ask to be added to the google group. Emails go out Saturday about details on Sunday meetings. And if you’re passing through New York on a Sunday, please consider just joining for one day!

Website

An amazing team of activists have been making the Alt Banking website better and better every week. It’s pretty much up to date and contains real resources for people who can’t come to the meetings, as well as for people who want to continue the conversation between meetings.

Please take a look and give us suggestions to make it even better.

Speakers

We’ve had some amazing speakers come to Alt Banking in the past – including Neil Barofsky, Sheila Bair, Merlyna Lim, Tom Adams, Moe Tkacik, and most recently Stanley Aronowitz – and many more coming up soon. I’d say it’s a great group to know about for the speaker list alone. The speakers come from 2-3pm before the regular 3-5 meeting on Sundays.

Projects

As I’ve mentioned before on mathbabe, we wrote a pretty cool book called Occupy Finance, and we recently got a second printing made since the first printing went so quickly. If you’d like a physical copy, please email alt.banking.ows@gmail.com with your address. A free pdf is available here.

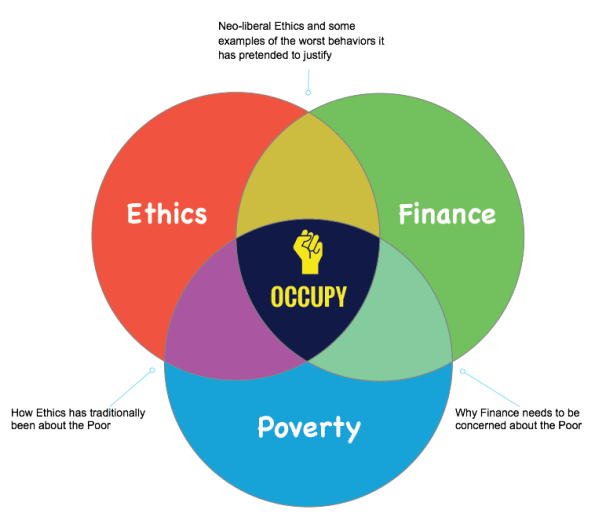

But that’s not all. Last week we decided to start our next big project, which is likely going to be some combination of a book and a movie, or a series of videos, or possibly a series of animated shorts, or something along those lines (still under consideration!). The content of the project is centered around three topics and their intersections, and we already have a cool “first iteration” visual due to Laminated Lychee (note the nerdy use of the Venn Diagram):

We’re also looking to have a cool roll-out for that project, possibly next September, possibly with a day-long conference of activists and lectures and activities. We could really use some help!

Fun

I also wanted to mention that we have a blast every week, and we often go out for dinner and/or a glass of wine or beer after the regular meeting. It’s really a great group of fun people.

Researching the Common Core

I’m in the middle of researching the Common Core standards for math. So far I’ve watched a Diane Ravitch talk, which I blogged about here, which was interesting but raised more questions than it answered, at least for me.

I’ve also interviewed Bill McCallum this week, who was a lead writer and chair of the Work Team that wrote the Common Core standards for mathematics. I’m still writing up that interview but I should have it done soon.

Next up I plan to interview a long-time teacher and current principal of a Brooklyn-based girls school for math and science, Kiri Soares, on her perspective on the Common Core standards and standardized tests in general.

One thing I can say already for sure: people who are not insiders here conflate a bunch of different issues. I’m hoping to at least separate them and understand where people stand on each issue, and if I at the very least get to the point of agreeing to disagree on well-defined points then I will have done my job.

Tell me if you think I need to go further to fully understand the issues at hand. Of course one thing I’m not doing is delving directly into the content of the standards, and that may very well be essential to understanding them. I’d love your thoughts.

Matt Stoller is tearing up Tumblr

I’ve been super impressed by Matt Stoller’s recent foray into “tumbling”, which is kind of like blogging except it’s called tumbling. Even the spam emails from tumblr are worth following him, because sometimes they contain his newest posts.

His title is Observations on Credit and Surveillance but in fact the content is all over the map, reading original source documents to describe the connections between communism and U.S. slavery or Gerald Ford and Watergate, not to mention the 1894 Post Office Bank proposal.

Most interesting to me is the information he’s uncovered about data provisions in the TPP and the history of credit cards and debt collection.

Go take a look, he’s been on fire. I hope he keeps it going.

Guest Post: Beauty, even in the teaching of mathematics

This is a guest post by Manya Raman-Sundström.

Mathematical Beauty

If you talk to a mathematician about what she or he does, pretty soon it will surface that one reason for working those long hours on those difficult problems has to do with beauty.

Whatever we mean by that term, whether it is the way things hang together, or the sheer simplicity of a result found in a jungle of complexity, beauty – or aesthetics more generally—is often cited as one of the main rewards for the work, and in some cases the main motivating factor for doing this work. Indeed, the fact that a proof of known theorem can be published just because it is more elegant is one evidence of this fact.

Mathematics is beautiful. Any mathematician will tell you that. Then why is it that when we teach mathematics we tend not to bring out the beauty? We would consider it odd to teach music via scales and theory without ever giving children a chance to listen to a symphony. So why do we teach mathematics in bits and pieces without exposing students to the real thing, the full aesthetic experience?

Of course there are marvelous teachers out there who do manage to bring out the beauty and excitement and maybe even the depth of mathematics, but aesthetics is not something we tend to value at a curricular level. The new Common Core Standards that most US states have adopted as their curricular blueprint do not mention beauty as a goal. Neither do the curriculum guidelines of most countries, western or eastern (one exception is Korea).

Mathematics teaching is about achievement, not about aesthetic appreciation, a fact that test-makers are probably grateful for – can you imagine the makeover needed for the SAT if we started to try to measure aesthetic appreciation?

Why Does Beauty Matter?

First, it should be a bit troubling that our mathematics classrooms do not mirror practice. How can young people make wise decisions about whether they should continue to study mathematics if they have never really seen mathematics?

Second, to overlook the aesthetic components of mathematical thought might be to preventing our children from developing their intellectual capacities.

In the 1970s Seymour Papert , a well-known mathematician and educator, claimed that scientific thought consisted of three components: cognitive, affective, and aesthetic (for some discussion on aesthetics, see here).

At the time, research in education was almost entirely cognitive. In the last couple decades, the role of affect in thinking has become better understood, and now appears visibly in national curriculum documents. Enjoying mathematics, it turns out, is important for learning it. However, aesthetics is still largely overlooked.

Recently Nathalie Sinclair, of Simon Frasier University, has shown that children can develop aesthetic appreciation, even at a young age, somewhat analogously to mathematicians. But this kind of research is very far, currently, from making an impact on teaching on a broad scale.

Once one starts to take seriously the aesthetic nature of mathematics, one quickly meets some very tough (but quite interesting!) questions. What do we mean by beauty? How do we characterise it? Is beauty subjective, or objective (or neither? or both?) Is beauty something that can be taught, or does it just come to be experienced over time?

These questions, despite their allure, have not been fully explored. Several mathematicians (Hardy, Poincare, Rota) have speculated, but there is no definite answer even on the question of what characterizes beauty.

Example

To see why these questions might be of interest to anyone but hard-core philosophers, let’s look at an example. Consider the famous question, answered supposedly by Gauss, of the sum of the first n integers. Think about your favorite proof of this. Probably the proof that did NOT come to your mind first was a proof by induction:

Prove that S(n) = 1 + 2 + 3 … + n = n (n+1) /2

S(k + 1) = S(k) + (k + 1)

= k(k + 1)/2 + 2(k + 1)/2

= k(k + 1)/2 + 2(k + 1)/2

= (k + 1)(k + 2)/2.

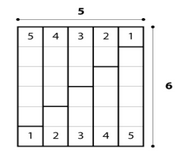

Now compare this proof to another well known one. I will give the picture and leave the details to you:

Does one of these strike you as nicer, or more explanatory, or perhaps even more beautiful than the other? My guess is that you will find the second one more appealing once you see that it is two sequences put together, giving an area of n (n+1), so S(n) = n (n+1)/2.

Note: another nice proof of this theorem, of course, is the one where S(n) is written both forwards and backwards and added. That proof also involves a visual component, as well as an algebraic one. See here for this and a few other proofs.

Beauty vs. Explanation

How often do we, as teachers, stop and think about the aesthetic merits of a proof? What is it, exactly, that makes the explanatory proof more attractive? In what way does the presentation of the proof make the key ideas accessible, and does this accessibility affect our sense of understanding, and what underpins the feeling that one has found exactly the right proof or exactly the right picture or exactly the right argument?

Beauty and explanation, while not obvious related (see here), might at least be bed-fellows. It may be the case that what lies at the bottom of explanation — a feeling of understanding, or a sense that one can ”see” what is going on — is also related to the aesthetic rewards we get when we find a particularly good solution.

Perhaps our minds are drawn to what is easiest to grasp, which brings us back to central questions of teaching and learning: how do we best present mathematics in a way that makes it understandable, clear, and perhaps even beautiful? These questions might all be related.

Workshop on Math Beauty

This March 10-12, 2014 in Umeå, Sweden, a group will gather to discuss this topic. Specifically, we will look at the question of whether mathematical beauty has anything to do with mathematical explanation. And if so, whether the two might have anything to do with visualization.

If this discussion peaks your interest at all, you are welcome to check out my blog on math beauty. There you will find a link to the workshop, with a fantastic lineup of philosophers, mathematicians, and mathematics educators who will come together to try to make some progress on these hard questions.

Thanks to Cathy, the always fabulous mathbabe, for letting me take up her space to share the news of this workshop (and perhaps get someone out there excited about this research area). Perhaps she, or you if you have read this far, would be willing to share your own favorite examples of beautiful mathematics. Some examples have already been collected here, please add yours.

How to Lie With Statistics (in the Age of Big Data)

When I emailed my mom last month to tell her the awesome news about the book I’m writing she emailed me back the following:

i.e, A modern-day How to Lie with Statistics (1954), avail on Amazon

for $9.10. Love, Mom

That was her whole email. She’s never been very verbose, in person or electronically. Too busy hacking.

Even so, she gave me enough to go on, and I bought the book and recently read it. It was awesome and I recommend it to anyone who hasn’t read it – or read it recently. It’s a quick read and available as a free pdf download here.

The goal of the book is to demonstrate all the ways marketers, journalists, accountants, and sometimes even statisticians can bias your interpretation of statistical facts or even just confuse you into thinking something is true when it’s not. It’s illustrated as well, which is fun and often funny.

The author does things like talk about how you can present graphs to be very misleading – my favorite, because it happens to be my pet peeve, is the “growth chart” where the y-axis goes from 1400 to 1402 so things look like they’ve grown a huge amount because “0” isn’t represented anywhere. Or of course the chart that has no numbers at all so you don’t know what you’re looking at.

There are a few things that don’t translate: so for example, he has a big thing about how people say “average” but they don’t specify whether they mean “arithmetic mean” or “median.” Nowadays this is taken to mean the former (am I wrong?).

And also, it’s fascinating to see how culture has changed – many of his examples that involve race would be very different nowadays, and issues around women, and the idea that you could run a randomized experiment to give half the people polio vaccines and withhold them from the other half, when polio is a real threat that leaves children paralyzed, is really strange.

Also, many of the examples – there are hundreds – refer to the Great Depression and the recovery since then, and the assumptions are bizarrely different in 1954 than you see in 2014 (and I’d guess different than how it will be in 2024 but I hope I’m wrong). Specifically, it seems that many of the lies that people are propagating with statistics are to downplay their profits so as to not seem excessive. Can you imagine?!

One of the reasons I read this book, of course, was to see if my book really is a modern version of that one. And I have to say that many of the issues do not translate, but some of them do, in interesting ways.

Even the reason that many of them don’t is kind of interesting: in the age of big data, we often don’t even see charts of data so how can we be misled by them? In other words, the presumption is that the data is so big as to be inaccessible. Google doesn’t bother showing us the numbers. Plus they don’t have to since we use their services anyway.

The most transferrable tips on how to lie with statistics probably stem from discussions on the following topics:

- Selection bias (things like, of the people who responded to our poll, they are all happy with our service)

- Survivorship bias (things like, companies that have been in the S&P for 30 years have great stock performance)

- Confusing people about topic A by discussing a related but not directly relevant topic B. This is described in the book as a “semi-attached figure”

The last one is the most relevant, I believe. In the age of big data, and partly because the data is “too big” to take a real look at, we spend an amazing amount of time talking about how a model is measuring something we care about (teachers’ value, or how good a candidate is for a job) when in fact the model is doing something quite different (test scores, demographic data).

If we were aware of those discrepancies we’d have way more skepticism, but we’re intimidated by the size of the data and the complexity of the models.

A final point. For the most part that crucial big data issue of complexity isn’t addressed in the book. It kind of makes me pine for the olden days, except not really if I’m black, a woman, or at risk of being exposed to polio.

UPDATES: First, my bad for not understanding that, at the time, the polio vaccine wasn’t known to work, or even be harmful, so of course there were trials. I was speaking from the perspective of the present day when it seems obvious that it works. For that matter I’m not even sure it was the particular vaccine that ended up working that was being tested.

Second, I showed my mom this post and her response was perfect:

Glad you liked it! Love, Mom

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia missed you guys last week, she was sadly without wifi.

Or was she? Another possibility you might want to consider is that she was reading the entire history of the newly discovered NSFW critique my dick pic tumblr (not me! but kind of wish it were!), or possibly that she had finally discovered the way to bypass running out of lives on Candy Crush.

We will perhaps never know. But in the meantime, please

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Your letter from Sex Life: Unending Training brought to mind a reciprocal question from this straight male. Please posit, for purposes of discussion, that I’m not only experienced in bed but expert. And not one of your “80% good and who thinks they don’t need any tutoring” — I’m always eager to improve! A woman once told me in surprise, “I never thought you’d be subtle as a lover.” Others have said that had they known, they’d have jumped my bones sooner.

My question is this: how do I convey this to women like SLUT who would be interested in this fact, short of direct demonstration?

Don’t overlook My expertise

Dear DoMe,

First of all, I’m happy for you, kind of. I mean, what you’ve explained is that you exceed expectations, but then again that means you set them low to begin with.

My suggestion is to take a page from the Latin Lovers’ Handbook and sweet talk women with promises of amazing, mind-blowing experiences if they agree to go to bed with you. Turns out women love being flattered, and they also like signaling that emphasizes their pleasure as a priority.

In other words, the way to “convey” your mad skillz to women such as SLUT is to brag at length about them, in a raspy and whispery voice, directly into her ear. The more people around the better, this is no time to be shy. Commit to raising expectations, not lowering them, and be explicitly sexual. Women like sexy promises, especially if you can follow through, which you’re claiming you’ve got covered. I hope you’ve got that covered.

Oh and this all has to be done at the appropriate moment, of course, or else you’ll be super creepy.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How do partners of professors thrive professionally? From what I can see, most professors are employed in small/medium towns where employment opportunities are already limited. How do they make it work?

I’m currently employed in a job I love and can work remotely, but I’m worried about 3-7 years down the line when I’ll be looking for another job. What if my best options are the next big city 250-1000 miles away? Is there a way to support one another’s career with the combination of shorter job stints in the private sector, tenure requirements and a glacial job market in academia?

Professional

Dear Professional,

Great question. Lots of examples come to mind of partners who are also professors, or who work in the college/university in question in an administrative capacity, or who have super portable jobs such as high school teachers or doctors or lawyers (although the different state bars make that less than ideal).

I suggest that, when you and your partner are negotiating with a given school, after your partner has her or his offer, you mention this as an issue. It’s a super common problem of course, and I’m sure the institution has come up with ideas in the past.

However, the truth is that this system was set up in a different age, where women and families were expected to follow husbands around. So sometimes it just sucks. My overall advice for you is to consider all your options as a family, including having your partner leave academics and work in industry or such.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This will sound made-up but it’s not.

After accumulating a small but modestly comfortable stash, mostly for objectionable work in finance, I found a few years ago that I couldn’t find anything rewarding. This depressed me, setting me on a desultory search. Then a friend with 30 years’ experience managing grassroots developing-country projects told me he’d gotten into exporting non-conflict gold from small mines in darkest Africa and needed funds and a partner. He’d already raised a substantial amount from investors including a smart friend of ours. His bizarre adventures fascinated me, so I put a little into it but as urgency and promised payoffs grew I thought “what the hell” and invested the whole damn stash.

It turned out the friend, an intelligent, accomplished man, had a tragic weakness. He was a lover who sees no flaw even when his loved one is using the hell out of him – except his love object was Africans in general. I lost all my money.

My question: Five years after, possibly as a providential result of that act of personal creative destruction, I’ve found what I was looking for and am creeping back toward solvency. When I meet a woman and it may be getting serious, when do I tell her that her assumption that I’m well-heeled is wrong? This happened recently; after I told her things kind of came apart. It was relevant because she wanted children and it would be hard with little money. I think I’ll claw my way back to my previous wealth but can’t be sure. When and what should I have told her?

Decidedly uncertain of proper events to divulge

Dear Duopetd,

First of all, work on your acronyms – little words count, you know! You can’t assume “of” and “to” will be ignored!

Second of all, you’re right that the whole thing sounds completely made up, but mostly by you, in your weird little brain, because you don’t want to see the truth.

Here’s how I read your story. You made a bunch of money for the sole reason that you sold your soul at the right time. Then you got out and gave all your money to a swindler. Even so, you still like to think of yourself as a successful guy, so you maintain that facade to women when you date. When it gets serious, you either find out that those women are shallow and only wanted you for your money or that they can’t believe how dumb you were to give all your money to a swindler, or how sadly obsessed you are about money altogether. In any case the women leave, and I don’t blame them.

My advice to you is to get over yourself, and especially the idea that you need to be rich. Just get a job like everyone else and make sure you live within your means, and don’t take on airs, and please support your local public schools.

UPDATE: I’ve been told I’m being overly harsh here. It’s quite possible that people are misled by your nice clothes and resume. My advice is to nip the misimpressions in the bud on the first date. Figure out how to explain your true situation quickly and avoid longterm misunderstandings.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

The bro formula establishes a lower bound for the acceptable age of the woman in a romantic human male-female pair bond as 7 years + male age/2.

Is there a similar formula that gives a strict upper bound for the acceptable age of a pop music fan based on the age of the performer? Does it vary by gender of the performer and the fan? And, is there special treatment available for someone overage watching Girls Generation (ick) particularly?

Pop Music Makes Papa Leer

Dear PMMPL,

First of all, why is that the “bro” formula? Why does it have to always be about men and younger women? Why can’t women be interested in younger men? And how about older men and younger men, and older women and younger women? Sheesh. I hate that name.

But I don’t hate the formula itself. My theory is that this formula, correctly named and applied, is a nod to the fact that it is difficult to maintain an equitable relationship with someone with a vastly different amount of life experience. Of course there are exceptions (Harold and Maude) but in general we wish to maintain this kind of equity, and in general it makes more sense to do so – it’s easier to do so – with people of similar ages.

Having said that, when you check out the hip maneuvering on a music video such as this (terrible) Girls Generation offering, you are probably not expecting a long-term relationship with the doll-like characters. Putting aside how deeply fetishistic, stylized, and hypersexualized that overly produced crap is, I think the whole point of it is for everyone to leer. So you’re really just doing your job in some sense.

Having said that, if I had a young daughter I’d probably want to keep that stuff away from her, it looks like a breeding ground for eating disorders.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I saw an ad looking for a typist to generate a word doc from a typewritten manuscript. Is it unethical to scan the original document and use Optical Character Recognition software, and charge the same amount as a typist would?

Thanks!

Against Carpal Tunnel

Dear ACT,

I’m with you – if someone is dumb enough to not use technology, no reason you shouldn’t. However, there may be details about the requirements that don’t allow for your plan. Look carefully at the contract you sign.

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Journalism after Snowden

Last night I was lucky enough to grab a seat across Broadway at an event put on by Columbia Journalism School’s Tow Center called “Journalism after Snowden.”

It featured four distinguished panelists:

- Jill Abramson Executive Editor, The New York Times

- Janine Gibson Editor-in-Chief, Guardian U.S.

- David Schulz Outside Counsel to The Guardian and Partner, Levine, Sullivan Koch & Schulz LLP

- Cass Sunstein Member, President Obama’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies and Robert Walmsley University Professor, Harvard University

First Janine talked about receiving the documents from Snowden, or “the source” as he was called, and spending a bunch of time with her team in verifying the documents as well as focusing on exactly two questions:

- Is this story true?

- Is this story in the public’s interest?

She and her team decided it passed both those tests and they published it. Then Jill Abramson chimed in to talk about how the New York Times got in on the story as well.

David Schulz, and also Lee Bollinger who started out the evening, framed the legal issues around newspapers publishing things in the context of national security here in the U.S., and although much of it was over my head I came away with the distinct impression that in this country, journalisms have historically had a protected space.

However, there have been exceptions recently, and very recently Director of National Intelligence James Clapper insinuated that dozens of journalists reporting on documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden were “accomplices” to a crime.

Those recent events, and Obama’s general campaign against whistleblowers, which are in direct contradiction to his campaign promises, have had a chilling effect on reporting and on reporters who work on national security issues, according to NY Times Executive Editor Jill Abramson.

There was some discussion about how difficult it was to have secure communication between Snowden and journalists, given the situation, and how crucial it is to be able to do so for journalists in order to protect their sources. The question came up of whether it even makes sense for a journalist to suggest to a source that they’d be protected, given how much surveillance now exists.

My favorite line of the night came when David Schulz pointed out that we normal citizens might not think we care about having secure communications, since we don’t intend to do top secret messaging, but even so the lack of secure messaging systems for other people effects what we learn about the world.

Finally, there was a poll taken by the moderator Emily Bell: are we better off because of Snowden? Not all of the panelists agreed, or rather Jill, Janine, and David seemed to think it was obvious but Cass demurred, which I guess was consistent with his being on a Review Group for Obama.

Personally, I don’t think it’s super cut and dry, but I do think we need to have people like Snowden, and whistleblowers more generally, and that in any case journalists absolutely need legal protection to do their jobs.

One last personal comment: I find it absolutely amazing that an entire profession like journalism would actually consider the public good as a major question they put before them before they choose what to work on. I’m coming from inside the tech industry and finance, where the only question that is ever asked is whether an idea is profitable and, secondarily, legal. It’s a refreshing perspective, although I’m guessing somewhat misleading.

Friday protest in Queens against Fast Track TPP #OWS

This coming Friday will be a coordinated day of action against the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP). Actions will take place all over the world with the New York version taking place at noon in Queens (details below).

Why anti-TPP? Isn’t “free trade” a good thing? The word “free” is in it!

Language is a tricky thing, and people choose the names of their initiatives to make them sound good. We know that from the “pro life” and “pro choice” debate.

Turns out that, in this case, “free trade” is a weird phrase to describe a campaign that increases the legal power of corporations (ex: tobacco companies) against governments (ex: Namibia).

I’ve written about it here, but if you haven’t seen this Huffington Post video (h/t Matt Stoller) then please take the time. It’s funny and it’s an amazingly clear and beautiful explanation of the dangers of TPP, and especially the so-called “Fast Tracking” of that international agreement.

Details for the Queens anti-TPP rally on Friday

- TUG O’ JOE- a street theater performance where Crowley will be pulled by characters on both sides of the issues – corporate monsters on the one and the defenders of our jobs, health and environment on the other!

- CROWLEY – STOP BEING SPEECHLESS! – another street theater bit, satirizing Crowley’s “Speechless” presentation on the floor of Congress!

- NEW TPP SONGS by the NYC Raging Grannies!

- ROUSING SPEECHES by Mimi Rosenberg (WBAI’S Building Bridges: Your Community and Labor Report), Malú Huacuja del Toro (anti-NAFTA and Zapatista solidarity activist, acclaimed author), Corrine Rosen (Food and Water Watch), Freddy Castiblano (Latin America solidarity activist and small business owner), and others!

- Time: 10am – noon

- Location: Rep. Crowley’s Queens Office, 82-11 37th Ave between 82th and 83rd Streets, Jackson Heights, Queens. Please arrive on time as we may march! If you’re late and can’t find us, call Wendy at (347) 881-5635 or Carlos at (646) 416-3440.

- Directions: Take the 7 train to 82nd Street-Jackson Heights

- Additional Info: Phone: (718) 218-4523 Email: info@tradejustice.net Web: http://tradejustice.net/tpp

Diane Ravitch speaks in Westchester

One thing I learned on the “Public Facing Math” panel at the JMM was that I needed to know more about the Common Core, since so much of the audience was very interested in discussing it and since it was actually a huge factor in the public’s perception of math, both in the sense of high school math curriculum and in the context of the associated mathematical models related to assessments. In fact at that panel I promised to learned more about the Common Core and I urged other mathematicians in the room to do the same.

As part of my research I listened to a recent lecture that Diane Ravitch gave in Westchester which centered on the Common Core. The video of the lecture is available here.

Diane Ravitch

If you don’t know anything about Diane Ravitch, you should. She’s got a super interesting history in education – she’s an education historian – and in particular has worked high up, as the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education and on the National Assessment Governing Board, which supervises the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

What’s most interesting about her is that, as a high ranking person in education, she originally supported the Bush “No Child Left Behind” policy but now is an outspoken opponent of it as well as Obama’s “Race to the Top“, which she claims in an extension of the same bad idea.

Ravitch writes an incredibly interesting blog on education issues and, what’s most interesting to me, assessment issues.

Ravitch in Westchester

Let me summarize her remarks in a free-form and incomplete way. If you want to know exactly what she said and how she said it, watch the video, and feel free to skip the first 16 minutes of introductions.

She doesn’t like the Common Core initiative and mentions that Gates Foundation people, mostly not experienced educators, and many of them associated to the testing industry, developed the Common Core standards. So there’s a suspicion right off the bat that the material is overly academic and unrealistic for actual teachers in actual classrooms.

She also objects to the idea of any fixed and untested set of standards. No standard is perfect, and this one is rigid. At the very least, if we need a “one solution for all” kind of standard, it needs to be under constant review and testing and open to revisions – a living document to change with the times and with the needs and limits of classrooms.

So now we have an unrealistic and rigid set of standards, written by outsiders with vested interests, and it’s all for the sake of being able to test everyone to death. She also made some remarks about the crappiness of the Value-Added Model similar to stuff I’ve mentioned in the past.

The Common Core initiative, she explains, exposes an underlying and incorrect mindset, which is that testing makes kids learn, and more testing makes kids learn faster. That setting a high bar makes kids suddenly be able to jump higher. The Common Core, she says, is that higher bar. But just because you raise standards doesn’t mean people suddenly know more.

In fact, she got a leaked copy of last year’s Common Core test and saw that it’s 5th grade version is similar to a current 8th grade standardized test. So it’s very much this “raise the bar” setup. And it points to the fact that standardized testing is used as punishment rather than diagnostic.

In other words, if we were interested in finding out who needs help and giving them help, we wouldn’t need harder and harder tests, we’d just look at who is struggling with the current tests and go help them. But because it’s all about punishment, we need to add causality and blame to the environment.

She claims that poverty causes kids to underperform in schools, and blaming the teachers on poverty is a huge distraction and meaningless for those kids. In fact, she asks, what are going to happen to all of those kids who fail the Common Core standards? What is going to become of them if we don’t allow them to graduate? And how do we think we are helping them? Why do we spend so much time with developing these fancy tests and on assessments instead of figuring out how to help them graduate?

She also points out that the blame game going on in this country is fueled by bad facts.

For example, there is no actual educational emergency in this country. In fact, test scores and graduation rates have never been higher for each racial group. And, although we are alway made to be afraid vis a vis our “international competition” (great recent example of this here) we actually historically never scored at the top of international rankings. But we didn’t think that meant we weren’t competitive 50 years ago, so why do we suddenly care now?

She provides the answer. Namely, if people are convinced there is an emergency in education, then the private companies – test prep and testing companies as well as companies that run charter school – stand to make big money from our response and from straight up privatization.

The statistical argument that poverty causes educational delays is ready to be made. If we want to “fix our educational system” then we need to address poverty, not scapegoat teachers.

Jamie Dimon’s bonus too low – shoulda been $100 million at least

Crossposted on the Alt Banking blog, the below reflects a discussion at Alt Banking from last Sunday’s meeting.

People have been making a big fuss about JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon’s recent raise. They seem to think that, what with all the lawsuits that JP Morgan Chase has been involved in this past year, exposing so much fraudulent behavior which directly contributed to so much human suffering, the guy should be somewhat humbled and punished. They even wanna question his right to stock options he shoulda had way back in 2008, when the world was on fire. The nerve!

I mean, maybe by some definition of “earned” he doesn’t deserve those 20 sticks. Maybe they think they have better plans for the bonus money. But from where I sit, the guy should have gotten way more, considering he set the price of fraud by big banks so low and in so many different ways.

I estimate that he should have gotten at least $100 million, using a very basic fact that the regulatory arbitrage which he displayed, and which now exists as a precedent for all bankers for the rest of eternity, benefitted not just him, not just JP Morgan Chase, but all the Too-Big-To-Fail banks. For that reason, every TBTF bank should give him at least $20 million as a reward for their future profitable fraudulent earnings. Since there are at least 5 TBTF banks, I’m just scaling up in a super reasonable way.

I know that might sound weird, for Bank of America and Goldman Sachs, which are generally speaking competitors to JP Morgan, to give Jamie Dimon cash money. And they might want to keep it on the DL for that matter, for the sake of appearances.

But after all, this is the guy who called Attorney General Eric Holder on the phone and negotiated a settlement, for christ’s sake! Who DOES that? That’s really above and beyond the chutzpah of even the most criminal of masterminds. Only the creamiest of the crop, only the most devoted of banker psychopaths can get away with that shit. That is to say, Jamie Dimon, and maybe Lloyd Blankfein (Dear Lloyd: I don’t doubt for a minute that you will have your day too, very soon, and then all the big boys will pitch in for your supersized bonus).

So what are you waiting for, Citigroup? Wells? When are you guys ponying up what we all know Dimon deserves from all of the elite institutions protected from prosecution? I say you guys perform the equivalent of a kowtow in Wall Street terms, which is of course monetized, in the form of a check. Send it on over.

Come to think of it we should also offer extra cash to HSBC’s legal team, and for that matter Eric Holder himself. If it hasn’t already been done.

A visit to Fair Foods in winter

It’s been a few days since I last posted. The reason was my trip to WPI for my talk (slides from my talk available here), and then on to Boston, where I stayed with my good friends over at Fair Foods in Dorchester, near Fields Corner.

I mentioned Fair Foods before, for example in this post from two and a half years ago. I worked with the director Nancy in high school back in 1988 and 1989, when me and my sometimes guest blogger Becky would go work a couple of days a week. Here’s a picture I stole from the site with Becky in overalls:

We’d drive at 6am with Nancy and her beat up old box truck to the Chelsea Produce Market and ask for donations of pallets of vegetables that were too old to be sold to supermarkets but still fresh enough to be eaten that same day. We’d also grab similarly oldish bread from an Arnold’s Bread bakery in Cambridge and then we’d distribute the food at “dollar bag” sites, raking in less than the amount of money we’d spent on gas and insurance for the truck.

The program is still going, scraping by with sometime grants and contributions, many from ex-volunteers like me (feel free to send a contribution yourself – a check made out to “Fair Foods” and mailed to PO Box 220168, Dorchester, MA 02122 would be very welcome). And the hard working people there have my undying love and admiration for their incredible commitment and work ethic. To give you some idea, they live in an old drafty Victorian and heat their house with woodstoves. All I can say about this past weekend is thank god for union suits and wool socks.

But here’s the thing, you get a pretty ground-level view of hardship and poverty working in a program like that, especially when you’ve done it for more than 25 years, and especially when you see increasingly long lines of people willing to wait for vegetables and bread in bitterly cold weather. Business is booming this winter.

Many of the customers of Fair Foods are old friends by now, they’ve been coming weekly to various sites for many years to feed their children and their grandchildren. Many of them are immigrants with very little money, and the $2 it now costs for a big bag of vegetables and fruit is a great deal.

I guess my point is this. I worked for Fair Foods back in the crack epidemic of the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s, which was a hellish time for Dorchester and of course other parts of the country. But nowadays, when the crime rate is so much lower, we’re seeing another kind of hell. It’s a lot quieter.

It’s incredibly sad to see how much more demand there is for salvaged food now than there was 25 years ago, and how many of those old beautiful Victorian family houses are abandoned or at risk of foreclosure, and how few cars there are on the street compared to then. And most especially, how many of the kids I used to play with on the street are now in prison.

Before I left Saturday I made a delicious soup out of the vegetables that Jason and Liz had collected from the Chelsea Market, and I made banana bread that the banana guy had given them. A little boy from the neighborhood who came to talk to Nancy about his report card ate about half of that banana bread in one sitting. A small attempt to try to feed the people who work so hard to feed other people.

It makes me wonder what kind of country we’ve created where people are so hungry, we’re reducing food stamps, and Jamie Dimon is getting an extra big bonus. Where is the justice in that?

How do you define success for a calculus MOOC?

I’m going to strike now, while the conversational iron is hot, and ask people to define success for a calculus MOOC.

Why?

I’ve already mostly explained why in this recent post, but just in case you missed it, I think mathematics is being threatened by calculus MOOCs, and although maybe in some possibly futures this wouldn’t be a bad thing, in others it definitely would.

One way it could be a really truly bad thing is if the metric of success were as perverted as we’ve seen happen in high school teaching, where Value-Added Models have no defined metric of success and are tearing up a generation of students and teachers, creating the kind of opaque, confusing, and threatening environment where code errors lead to people getting fired.

And yes, it’s kind of weird to define success in a systematic way given that calculus has been taught in a lot of places for a long time without such a rigid concept. And it’s quite possible that flexibility should be built in to the definition, so as to acknowledge that different contexts need different outcomes.

Let’s keep things as complicated as they need to be to get things right!

The problem with large-scale models is that they are easier to build if you have some fixed definition of success against which to optimize. And if we mathematicians don’t get busy thinking this through, my fear is that administrations will do it for us, and will come up with things based strictly on money and not so much on pedagogy.

So what should we try?

Here’s what I consider to be a critical idea to get started:

- Calculus teachers should start experimenting with teaching calculus in different ways. Do randomized experiments with different calculus sections that meet at comparable times (I say comparable because I’ve noticed that people who show up for 8am sections are typically more motivated students, so don’t pit them against 4pm sections).

- Try out a bunch of different possible definitions of success, including the experience and attitude of the students and the teacher.

- So for example, it could be how students perform on the final, which should be consistent for both sections (although to do that fairly you need to make sure the MOOC you’re using covers the critical material to do the final).

- Or it could be partly an oral exam or long-form written exam, whether students have learned to discuss the concepts (keeping in mind that we have to compare the “MOOC” students to the standardly taught students).

- Design the questions you will ask your students and yourself before the semester begins so as to practice good model design – we don’t want to decide on our metric after the fact. A great way to do this is to keep a blog with your plan carefully described – that will timestamp the plan and allow others to comment.

- Of course there’s more than one way to incorporate MOOCs in the curriculum, so I’d suggest more than one experiment.

- And of course the success of the experiment will also depend on the teaching style of the calc prof.

- Finally, share your results with the world so we can all start thinking in terms of what works and for whom.

One last comment. One might complain that, if we do this, we’re actually speeding on our own deaths by accelerating the MOOCs in the classroom. But I think it’s important we take control before someone else does.

Upcoming talks

A few months ago I gave a talk entitled “Start Your Own Netflix” talk that was part of the MAA Distinguished Lecture Series, the slides for which are available here and a short video version here.

Today I’m planning to modify that talk so I can give a longer and more technical version of it on Friday morning at the Department of Mathematical Science of Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where I’ve been invited to speak by Suzy Weekes.

In about a month I’m going to Berkeley for a week to give a so-called MSRI-Evans talk on Monday, February 24th, at 4pm, thanks to the kind invitation of Lauren Williams. I still haven’t decided whether to give a “The World Is Going To Hell” talk, which would be kind of the technical version of my book (and which I gave at Harvard’s IQSS recently), or whether I should give yet another version of the Netflix talk, which is cool and technical but not as doomsday. If you’re planning to attend please voice your opinion!

Finally, I’m hoping to join in a meeting of some manifestation of the Noetherian Ring while I’m at Berkeley. This is a women in math group that was started when I was an undergrad there, back in the middle ages, in something like 1992. It’s where I gave my first and second math talks and there was always free pizza. It really was a great example of how to create a supportive environment for collaborative math.

If it’s hocus pocus then it’s not math

A few days ago there was a kerfuffle over this “numberphile” video, which was blogged about in Slate here by Phil Plait in his “Bad Astronomy” column, with a followup post here with an apology and a great quote from my friend Jordan Ellenberg.

The original video is hideous and should never have gotten attention in the first place. I say that not because the subject couldn’t have been done well – it could have, for sure – but because it was done so poorly that it ends up being destructive to the public’s most basic understanding of math and in particular positive versus negative numbers. My least favorite line from the crappy video:

I was trying to come up with an intuitive reason for this I and I just couldn’t. You have to do the mathematical hocus pocus to see it.

What??

Anything that is hocus pocus isn’t actually math. And people who don’t understand that shouldn’t be making math videos for public consumption, especially ones that have MSRI’s logo on them and get written up in Slate. Yuck!

I’m not going to just vent about the cultural context, though, I’m going to mention what the actual mathematical object of study was in this video. Namely, it’s an argument that “prove” that we have the following identity:

Wait, how can that be? Isn’t the left hand side positive and the right hand side negative?!

This mathematical argument is familiar to me – in fact it is very much along the lines of stuff we sometimes cover at the math summer program HCSSiM I teach at sometimes (see my notes from 2012 here). But in the case of HCSSiM, we do it quite differently. Specifically, we use it as a demonstration of flawed mathematical thinking. Then we take note and make sure we’re more careful in the future.

If you watch the video, you will see the flaw almost immediately. Namely, it starts with the question of what the value is of the infinite sum

But here’s the thing, that doesn’t actually have a value. That is, it doesn’t have a value until you assign it a value, which you can do but then you might want to absolutely positively must explain how you’ve done so. Instead of that explanation, the guy in the video just acts like it’s obvious and uses that “fact,” along with a bunch of super careless moving around of terms in infinite sums, to infer the above outrageous identity.

To be clear, sometimes infinite sums do have pretty intuitive and reasonable values (even though you should be careful to acknowledge that they too are assigned rather than “true”). For example, any geometric series where each successive term gets smaller has an actual “converging sum”. The most canonical example of this is the following:

What’s nice about this sum is that it is naively plausible. Our intuition from elementary school is corroborated when we think about eating half a cake, then another quarter, and then half of what’s left, and so on, and it makes sense to us that, if we did that forever (or if we did that increasingly quickly) we’d end up eating the whole cake.

This concept has a name, and it’s convergence, and it jibes with our sense of what would happen “if we kept doing stuff forever (again at possibly increasing speed).” The amounts we’ve measured on the way to forever are called partial sums, and we make sure they converge to the answer. In the example above the partial sums are and so on, and they definitely converge to 1.

There’s a mathematical way of defining convergence of series like this that the geometric series follows but that the series does not. Namely, you guess the answer, and to make sure you’ve got the right one, you make sure that all of the partial sums are very very close to that answer if you go far enough, for any definition of “very very close.”

So if you want it to get within 0.00001, there’s a number N so that, after the Nth partial sum, all partial sums are within 0.00001 of the answer. And so on.

Notice that if you take the partial sums of the series you get the sequence

which doesn’t get closer and closer to anything. That’s another way of saying that there is no naively plausible value for this infinite sum.

As for the first infinite sum we came across, the that does have a naively plausible value, which we call “infinity.” Totally cool and satisfying to your intuition that you worked so hard to achieve in high school.

But here’s the thing. Mathematicians are pretty clever, so they haven’t stopped there, and they’ve assigned a value to the infinite sum in spite of these pesky intuition issues, namely

, and in a weird mathematical universe of their construction, which is wildly useful in some contexts, that value is internally consistent with other crazy-ass things. One of those other crazy-ass things is the original identity

[Note: what would be really cool is if a mathematician made a video explaining the crazy-ass universe and why it’s useful and in what contexts. This might be hard and it’s not my expertise but I for one would love to watch that video.]

That doesn’t mean the identity is “true” in any intuitively plausible sense of the word. It means that mathematicians are scrappy.

Now here’s my last point, and it’s the only place I disagree somewhat (I think) with Jordan in his tweets. Namely, I really do think that the intuitive definition is qualitatively different from what I’ve termed the “crazy-ass” definition. Maybe not in a context where you’re talking to other mathematicians, and everyone is sufficiently sophisticated to know what’s going on, but definitely in the context of explaining math to the public where you can rely on number sense and (hopefully!) a strong intuition that positive numbers can’t suddenly become negative numbers.

Specifically, if you can’t make any sense of it, intuitive or otherwise, and if you have to ascribe it to “mathematical hocus pocus,” then you’re definitely doing something wrong. Please stop.

The coming Calculus MOOC Revolution and the end of math research

I don’t usually like to sound like a doomsayer but today I’m going to make an exception. I’m going to describe an effect that I believe will be present, even if it’s not as strong as I am suggesting it might be. There are three points to my post today.

1) Math research is a byproduct of calculus teaching

I’ve said it before, calculus (and pre-calculus, and linear algebra) might be a thorn in many math teachers’ side, and boring to teach over and over again, but it’s the bread and butter of math departments. I’ve heard statistics that 85% of students who take any class in math at a given college take only calculus.

Math research is essentially funded through these teaching jobs. This is less true for the super elite institutions which might have their own army of calculus adjuncts and have separate sources of funding both from NSF-like entities and private entities, but if you take the group of people I just saw at JMM you have a bunch of people who essentially depend on their take-home salary to do research, and their take-home salary depends on lots of students at their school taking service courses.

I wish I had a graph comparing the number of student enrolled in calculus each year versus the number of papers published in math journals each year. That would be a great graphic to have, and I think it would make my point.

2) Calculus MOOCs and other web tools are going to start replacing calculus teaching very soon and at a large scale

It’s already happening at Penn through Coursera. Word on the street is it is about to happen at MIT through EdX.

If this isn’t feasible right now it will be soon. Right now the average calculus class might be better than the best MOOC, especially if you consider asking questions and getting a human response. But as the calculus version of math overflow springs into existence with a record of every question and every answer provided, it will become less and less important to have a Ph.D. mathematician present.

Which isn’t to say we won’t need a person at all – we might well need someone. But chances are they won’t be tenured, and chances are they could be overseas in a call center.

This is not really a bad thing in theory, at least for the students, as long as they actually learn the stuff (as compared to now). Once the appropriate tools have been written and deployed and populated, the students may be better off and happier. They will very likely be more adept at finding correct answers for their calculus questions online, which may be a way of evaluating success (although not mine).

It’s called progress, and machines have been doing it for more than a hundred years, replacing skilled craftspeople. It hurts at first but then the world adjusts. And after all, lots of people complain now about teaching boring classes, and they will get relief. But then again many of them will have to find other jobs.

Colleges might take a hit from parents about how expensive they are and how they’re just getting the kids to learn via computer. And maybe they will actually lower tuition, but my guess is they’ll come up with something else they are offering that makes up for it which will have nothing to do with the math department.

3) Math researchers will be severely reduced if nothing is done

Let’s put those two things together, and what we see is that math research, which we’ve basically been getting for free all this time, as a byproduct of calculus, will be severely curtailed. Not at the small elite institutions that don’t mind paying for it, but at the rest of the country. That’s a lot of research. In terms of scale, my guess is that the average faculty will be reduced by more than 50%, and some faculties will be closed altogether.

Why isn’t anything being done? Why do mathematicians seem so asleep at this wheel? Why aren’t they making the case that math research is vital to a long-term functioning society?

My theory is that mathematicians haven’t been promoting their work for the simple reason that they haven’t had to, because they had this cash cow called calculus which many of them aren’t even aware of as a great thing (because close up it’s often a pain).

It’s possible that mathematicians don’t even know how to promote math to the general public, at least right now. But I’m thinking that’s going to change. We’re going to think about it pretty hard and learn how to promote math research very soon, or else we’re going back to 1850 levels of math research, where everyone knew each other and stuff was done by letter.

How worried am I about this?

For my friends with tenure, not so worried, except if their entire department is at risk. But for my younger friends who are interested in going to grad school now, I’m not writing them letters of recommendation before having this talk, because they’ll be looking around for tenured positions in about 10 years, and that’s the time scale at which I think math departments will be shrinking instead of expanding.

In terms of math PR, I’m also pretty worried, but not hopeless. I think one can really make the case that basic math research should be supported and expanded, but it’s going to take a lot of things going right and a lot of people willing to put time and organizing skills into the effort for it to work. And hopefully it will be a community effort and not controlled by a few billionaires.

Billionaire money in mathematics

During the recent JMM AMS panel I was on, where the topic was the Public Face of Math, the issue came up repeatedly that we mathematicians might want to find a billionaire who could solve all our PR problems (although we didn’t quite seem to agree on what these PR problems are).

Indeed billionaire money seemed to represent a panacea even though it originated with a slightly facetious suggestion of a super PAC for mathematics from Congressman Jerry McNerney. The idea was taken quite seriously and repeated by at least 3 audience members.

I think this happened for a few reasons. First, mathematicians are mostly apolitical and don’t think of politics or PR as part of their job. They also don’t think they’re good at that stuff, and they are happy for someone else to do it. Who else but a rich guy interested in that stuff and who “has people” who are good at it.

Second, Jim Simons has been doing good stuff for math lately and people trust him. I totally get that, and I don’t entirely disagree, although invitation-only conferences in the Virgin Islands is not my idea of easy and transparent access to ideas that many mathematicians strive for. I hear his Quanta Magazine is awesome.

Here’s the thing. We lose something when we consistently take money from rich people, which has nothing to with any specific rich person who might have great ideas and great intentions.

The first thing we lose is power, and specifically control over our own image. That might seem like a fair deal now, since at least someone is working on it, but it’s not obvious that it would always be.

It means, for example, that one person has a huge amount of influence about, say, how the math community deals with the NSA. As we know this is an recent and ongoing discussion, but it came up pretty suddenly, as issues do, and it might be weird to all of a sudden need to know what some rich guy thinks of a specific issue.

Another example of why taking money from a few super rich people might not be a great idea requires the idea of a funding feedback loop, which well articulated by Benjamin Soskis and Felix Salmon with respect to the public parks in New York City.

The basic idea is that, as public funding dries up for something like public parks (or from the NSF) and as a community gets desperate for basic operating funds, money from rich individuals seems like a godsend. But over time two things happen.

First, the public funding never ever comes back. Because, after all, why should it? It looks like everything is well-funded. And the individuals who are part of that community are not agitating for the return of that funding since they have jobs.

Second, it’s not clear that the new money will be distributed in a good governance type of way. It might be distributed based on where rich people live, in the case of parks, or what their preferred mathematical subjects are, in the case of math. And the community has no recourse on those decisions, because the entire system depends on the generosity of someone who could change his mind at any moment.

And I’m not saying NSF doesn’t have weird rubriks for which fields (and which people!) get funded as well, but at least we can have a public discussion about that and make noise. And the decisions are made by different groups of mathematicians every year.

My suggestion is that we should think about representing ourselves in this PR campaign, if we have one to wage, and we should focus efforts on things that would improve NSF funding instead of getting us addicted to private funding. And it should be a community conversation where everyone participates who cares enough.

What are the chances that will ever happen? In terms of whether typical mathematicians will ever be willing to become politically active, my vote is on “yes” and “very soon,” and the reason I say this is that I believe mathematics research is being hugely (if quietly) threatened by the oncoming Calculus MOOC Revolution, which I plan to write about very soon.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is getting some help this morning from a fellow math nerd whom she loves dearly. Feel free to try to spot the advice that comes from yours truly versus from this adorable snoring freak. And please,

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

How unprofessional is it, in academia, for the spouse of an applicant to contact the department with questions about the search process? My husband isn’t really comfortable making any contact besides submitting the applications through mathjobs.org. I’ve been told by his colleagues that personal communication with the places one would really, really like to be is actually welcomed – but I’d better not try to do it instead of him. Any thoughts?

Desperate To Move To Washington State

Dear Desperate,

First, I’d like to corroborate your suspicion: if it’s really a job your husband wants, then it’s a very good idea for him to contact the schools directly, even if it makes him uncomfortable. Second, let me corroborate your guess that it’s not okay for you to do this. If I’m a professor on a search committee and someone’s spouse contacts me to ask how the process is moving along, I’m wondering why I’m not talking to the applicant instead.

Feel free to show this to your husband if it helps! He’s gotta take one for the team here!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunty Pythia,

I read this heartwarming article this morning. However I disagree that androgyny is not helpful at the office. I am a female geophysicist working in corporate Canada (the oil industry even) and I feel like both the male and female aspects of my personality are engaged and developed daily, for which I am thankful. The male aspects are obvious but I find so-called female aspects such as empathy, compassion and communication skills are golden. Success in an office depends on relationships and the female aspects of personality are strong in that. Please share your opinion on the article. How does being an alpha female (which is androgynous by definition) help you achieve awesome results? What male traits do you cultivate? What female traits do you prize?

Pat from Canada

Dear Pat,

As for the article, this is an example where less research might be good. And I don’t think Madonna is androgynous, by the way, she is and always was very female. If people interpret her power as male then they are just being narrow.

As for being an alpha female, I’m doing it without conscious effort, and as you might remember just recently realized I do it at all. I think that’s part of what makes it work. If I got anything out of the article at all it’s that people get considered “creative” if they successfully ignore stereotypes.

And in that vein, I don’t categorize my many traits as male or female. Why should I? They’re all mine.

Before I leave it there, let me mention that, when I’m around men I notice I think differently from most men, and when I’m with women I notice that I think differently from most women. And I guess if I had to define my own psychological gender I’d be confused and somewhere in the middle (although I definitely strongly identify physically as female). But it’s not clear that most people don’t feel exactly the same way as I do.

In other words, don’t most people feel like freaks on the inside? I think so. The trick is to own the inner freak, and freaks transcend categories, including gender categories.

Love,

Aunty Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I appreciate and respect that there are many advantages to people having different values and points of view, like innovation and entrepreneurial spirit. But, I find that it’s just so much more cheerful when everyone around mostly wants to be like everyone else.

How can a person who comes from a place that strives for a harmonious society live contentedly in a Western country?

Kind regards,

Alien

Dear Alien,

How would I know?

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dearest Aunt P,

I was wondering if you’ve seen the game Clusterfuck developed by the Cards Against Humanity Team (introductory video here).

What do you think?

With love,

A Curious Thing…

Dear Curious,

I love the idea, but it’s not clear from the provocative video that anyone ever actually gets laid. Please confirm I am wrong by re-sending question with a new homemade video.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I recently started a new relationship with a woman who is into some dominant/submissive stuff in the bedroom. It’s all new to me, and I’ve been pretty careful to discuss anything I’m leery about, get consent, have safe words, and that kind of thing. It turns out that it’s something we’re both *really* into, and that’s interesting in itself. (I’m 37 and just discovering this about myself.)

Here’s my question, though. After 3 months of dating, I’ve become concerned for my partner’s emotional health, based on an on-going medical issue which has, in the past, caused severe depression. She also has some slow-motion family tragedies that would really do a number on someone’s self-esteem. She’s a strong, accomplished woman, but over the past week she’s been nearly bed-ridden with anxiety, missing work and occasionally meals.

It’s a scary situation, and I’m trying to give her as much support as I can until her new job’s health insurance kicks in. But she still wants sex, occasionally the submissive kind (rape fantasy, etc.).

How on God’s green Earth do I (consensually, with safe words) sexually “mis”-treat somebody who’s going through a crisis like that? I can’t figure out if going through with it would be a comfort for her, or make things worse; neither can I figure out whether saying no would be seen as a painful rejection. In the meantime, I’ve been trying to keep things vanilla with a bit of aggressive talk, until we can stabilize the situation.

Any advice would be appreciated.

Bernoulli honored Descartes eventually, Steltjes learned Minkowskian parabolas

Dear BhDeSlMp,

First, nice acronym.

Second, I think you are super thoughtful and nice to be worried about this, and I would encourage you to bring these things up with her very directly and double-check that kinky sex isn’t a threat to her emotional well-being. But my guess is that it’s a release and an escape from her problems rather than an addition to her problems, especially when she’s engaging in it with someone who is looking out for her and keeping her safe as you are doing.

In other words, the quotes around “mis” are there for a reason, and I don’t think you should feel abusive if she’s asking for this and you guys are both consenting and into it. That said, there are certainly ways to be unhealthy about this stuff, like any stuff, so keep your eyes peeled for danger signs. In the meantime snuggling up afterwards and engaging in thoughtful pillow talk might be just what she needs.

And have fun!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

JMM

It occurs to me, as I prepare to join my panel this afternoon on Public Facing Math, that I’ve been to more Joint Math Meetings in the 7 years since I left academic math (3) than I did in the 17 years I was actually in math (2). I include my undergraduate years in that count because when I was a junior in college I went to Vancouver for the JMM and I met Cora Sadosky, which was probably my favorite conference ever.

Anyhoo I’m on my way to one of the highlights of any JMM, the HCSSiM breakfast, where we hang out with students and teachers from summers long ago and where I do my best to convince the director Kelly and myself that I should come back next summer to teach again. Then after that I spend 4 months at home convincing my family that it’s a great plan. Woohoo!

Besides the above plan, I plan to meet people in the hallways and gossip. That’s all I have ever accomplished here. I hope it is the official mission of the conference, but I’m not sure.

What is regulation for?

A couple of days ago I was listening to a recorded webinar on K-12 student data privacy. I found out about it through an education blog I sometimes read called deutsch29, where the blog writer was complaining about “data chearleaders” on a panel and how important issues are sure to be ignored if everyone on a panel is on the same, pro-data and pro-privatization side.

Well as it turns out deutsch29 was almost correct. Most of the panelists were super bland and pro-data collection by private companies. But the first panelist named Joel Reidenberg, from Fordham Law School, reported on the state of data sharing in this country, the state of the law, and the gulf between the two.

I will come back to his report in another post, because it’s super fascinating, and in fact I’d love to interview that guy for my book.

One thing I wanted to mention was the high-level discussion that took place in the webinar on what regulation is for. Specifically, the following important question was asked:

Does every parent have to become a data expert in order to protect their children’s data?

The answer was different depending on who answered it, of course, but one answer that resonated with me was that that’s what regulation is for, it exists so that parents can rely on regulation to protect their children’s privacy, just as we expect HIPAA to protect the integrity of our medical data.

I started to like this definition – or attribute, if you will – of regulation, and I wondered how it relates to other kinds of regulation, like in finance, as well as how it would work if you’re arguing with people who hate all regulation.

First of all, I think that the financial industry has figured out how to make things so goddamn complicated that nobody can figure out how to regulate anything well. Moreover, they’ve somehow, at least so far, also been able to insist things need to be this complicated. So even if regulation were meant to allow people to interact with the financial system and at the same time “not be experts,” it’s clearly not wholly working. But what I like about it anyway is the emphasis on this issue of complexity and expertise. It took me a long time to figure out how big a problem that is in finance, but with this definition it goes right to the heart of the issue.

Second, as for the people who argue for de-regulation, I think it helps there too. Most of the time they act like everyone is a omniscient free agent who spends all their time becoming expert on everything. And if that were true, then it’s possible that regulation wouldn’t be needed (although transparency is key too). The point is that we live in a world where most people have no clue about the issues of data privacy, never mind when it’s being shielded by ridiculous and possibly illegal contracts behind their kids’ public school system.

Finally, in terms of the potential for protecting kids’ data: here the private companies like InBloom and others are way ahead of regulators, but it’s not because of complexity on the issues so much as the fact that regulators haven’t caught up with technology. At least that’s my optimistic feeling about it. I really think this stuff is solvable in the short term, and considering it involves kids, I think it will have bipartisan support. Plus the education benefits of collecting all this data have not been proven at all, nor do they really require such shitty privacy standards even if they do work.

Two thoughts on math research papers

Today I’d like to mention two ideas I’ve been having recently on how to make being a research mathematician (even) more fun.

1) Mathematicians should consider holding public discussions about papers

First, math nerds, did you know that in statistics they have formal discussions about papers? It’s been a long-standing tradition by the Royal Statistical Society, whose motto is “Advancing the science and application of statistics, and promoting use and awareness for public benefit,” to choose papers by some criterion and then hold regular public discussions about those papers by a few experts who are not the author, about the paper. Then the author responds to their points and the whole conversation is published for posterity.

I think this is a cool idea for math papers too. One thing that kind of depressed me about math is how rarely you’d find people reading the same papers unless you specifically got a group of people together to do so, which was a lot of work. This way the work is done mostly by other people and more importantly the payoff is much better for them since everyone gets a view into the discussion.

Note I’m sidestepping who would organize this whole thing, and how the papers would be chosen exactly, but I’d expect it would improve the overall feeling that I had of being isolated in a tiny math community, especially if the conversations were meant to be penetrable.

2) There should be a good clustering method for papers around topics

This second idea may already be happening, but I’m going to say it anyway, and it could easily be a thesis for someone in CS.

Namely, the idea of using NLP and other such techniques to cluster math papers by topic. Right now the most obvious way to find a “nearby” paper is to look at the graph of papers by direct reference, but you’re probably missing out on lots of stuff that way. I think a different and possibly more interesting way would be to use the text in the title, abstract, and introduction to find papers with similar subjects.

This might be especially useful when you want to know the answer to a question like, “has anyone proved that such-and-such?” and you can do a text search for the statement of that theorem.

The good news here is that mathematicians are in love with terminology, and give weird names to things that make NLP techniques very happy. My favorite recent example which I hear Johan muttering under his breath from time to time is Flabby Sheaves. There’s no way that’s not a distinctive phrase.

The bad news is that such techniques won’t help at all in finding different fields who have come across the same idea but have different names for the relevant objects. But that’s OK, because it means there’s still lots of work for mathematicians.

By the way, back to the question of whether this has already been done. My buddy Max Lieblich has a website called MarXiv which is a wrapper over the math ArXiv and has a “similar” button. I have no idea what that button actually does though. In any case I totally dig the design of the similar button, and what I propose is just to have something like that work with NLP.