“People analytics” embeds old cultural problems in new mathematical models

Today I’d like to discuss recent article from the Atlantic entitled “They’re watching you at work” (hat tip Deb Gieringer).

In the article they describe what they call “people analytics,” which refers to the new suite of managerial tools meant to help find and evaluate employees of firms. The first generation of this stuff happened in the 1950’s, and relied on stuff like personality tests. It didn’t seem to work very well and people stopped using it.

But maybe this new generation of big data models can be super useful? Maybe they will give us an awesome way of throwing away people who won’t work out more efficiently and keeping those who will?

Here’s an example from the article. Royal Dutch Shell sources ideas for “business disruption” and wants to know which ideas to look into. There’s an app for that, apparently, written by a Silicon Valley start-up called Knack.

Specifically, Knack had a bunch of the ideamakers play a video game, and they presumably also were given training data on which ideas historically worked out. Knack developed a model and was able to give Royal Dutch Shell a template for which ideas to pursue in the future based on the personality of the ideamakers.

From the perspective of Royal Dutch Shell, this represents huge timesaving. But from my perspective it means that whatever process the dudes at Royal Dutch Shell developed for vetting their ideas has now been effectively set in stone, at least for as long as the algorithm is being used.

I’m not saying they won’t save time, they very well might. I’m saying that, whatever their process used to be, it’s now embedded in an algorithm. So if they gave preference to a certain kind of arrogance, maybe because the people in charge of vetting identified with that, then the algorithm has encoded it.

One consequence is that they might very well pass on really excellent ideas that happened to have come from a modest person – no discussion necessary on what kind of people are being invisible ignored in such a set-up. Another consequence is that they will believe their process is now objective because it’s living inside a mathematical model.

The article compares this to the “blind auditions” for orchestras example, where people are kept behind a curtain so that the listeners don’t give extra consideration to their friends. Famously, the consequence of blind auditions has been way more women in orchestras. But that’s an extremely misleading comparison to the above algorithmic hiring software, and here’s why.

In the blind auditions case, the people measuring the musician’s ability have committed themselves to exactly one clean definition of readiness for being a member of the orchestra, namely the sound of the person playing the instrument. And they accept or deny someone, sight unseen, based solely on that evaluation metric.

Whereas with the idea-vetting process above, the training data consisted of “previous winners” which presumable had to go through a series of meetings and convince everyone in the meeting that their idea had merit, and that they could manage the team to try it out, and all sorts of other things. Their success relied, in other words, on a community’s support of their idea and their ability to command that support.

In other words, imagine that, instead of listening to someone playing trombone behind a curtain, their evaluation metric was to compare a given musician to other musicians that had already played in a similar orchestra and, just to make it super success-based, had made first seat.

That you’d have a very different selection criterion, and a very different algorithm. It would be based on all sorts of personality issues, and community bias and buy-in issues. In particular you’d still have way more men.

The fundamental difference here is one of transparency. In the blind auditions case, everyone agrees beforehand to judge on a single transparent and appealing dimension. In the black box algorithms case, you’re not sure what you’re judging things on, but you can see when a candidate comes along that is somehow “like previous winners.”

One of the most frustrating things about this industry of hiring algorithms is how unlikely it is to actively fail. It will save time for its users, since after all computers can efficiently throw away “people who aren’t like people who have succeeded in your culture or process” once they’ve been told what that means.

The most obvious consequence of using this model, for the companies that use it, is that they’ll get more and more people just like the people they already have. And that’s surprisingly unnoticeable for people in such companies.

My conclusion is that these algorithms don’t make things objective, they makes things opaque. And they embeds our old cultural problems in new mathematical models, giving us a false badge of objectivity.

Today I’m thankful for the pope

I’m not religious but I think Pope Francis is an awesome and inspiring thinker and leader. And yes, I’ve invited him to join Occupy. Here’s an excerpt from his recent Apostolic Exhortation in case you haven’t seen it yet:

No to an economy of exclusion

53. Just as the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say “thou shalt not” to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills. How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrown away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality. Today everything comes under the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless. As a consequence, masses of people find themselves excluded and marginalized: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape.

Human beings are themselves considered consumer goods to be used and then discarded. We have created a “disposable” culture which is now spreading. It is no longer simply about exploitation and oppression, but something new. Exclusion ultimately has to do with what it means to be a part of the society in which we live; those excluded are no longer society’s underside or its fringes or its disenfranchised – they are no longer even a part of it. The excluded are not the “exploited” but the outcast, the “leftovers”.

54. In this context, some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting. To sustain a lifestyle which excludes others, or to sustain enthusiasm for that selfish ideal, a globalization of indifference has developed. Almost without being aware of it, we end up being incapable of feeling compassion at the outcry of the poor, weeping for other people’s pain, and feeling a need to help them, as though all this were someone else’s responsibility and not our own. The culture of prosperity deadens us; we are thrilled if the market offers us something new to purchase; and in the meantime all those lives stunted for lack of opportunity seem a mere spectacle; they fail to move us.

No to the new idolatry of money

55. One cause of this situation is found in our relationship with money, since we calmly accept its dominion over ourselves and our societies. The current financial crisis can make us overlook the fact that it originated in a profound human crisis: the denial of the primacy of the human person! We have created new idols. The worship of the ancient golden calf (cf. Ex 32:1-35) has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose. The worldwide crisis affecting finance and the economy lays bare their imbalances and, above all, their lack of real concern for human beings; man is reduced to one of his needs alone: consumption.

56. While the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few. This imbalance is the result of ideologies which defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation. Consequently, they reject the right of states, charged with vigilance for the common good, to exercise any form of control. A new tyranny is thus born, invisible and often virtual, which unilaterally and relentlessly imposes its own laws and rules. Debt and the accumulation of interest also make it difficult for countries to realize the potential of their own economies and keep citizens from enjoying their real purchasing power. To all this we can add widespread corruption and self-serving tax evasion, which have taken on worldwide dimensions. The thirst for power and possessions knows no limits. In this system, which tends to devour everything which stands in the way of increased profits, whatever is fragile, like the environment, is defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which become the only rule.

No to a financial system which rules rather than serves

57. Behind this attitude lurks a rejection of ethics and a rejection of God. Ethics has come to be viewed with a certain scornful derision. It is seen as counterproductive, too human, because it makes money and power relative. It is felt to be a threat, since it condemns the manipulation and debasement of the person. In effect, ethics leads to a God who calls for a committed response which is outside of the categories of the marketplace. When these latter are absolutized, God can only be seen as uncontrollable, unmanageable, even dangerous, since he calls human beings to their full realization and to freedom from all forms of enslavement. Ethics – a non-ideological ethics – would make it possible to bring about balance and a more humane social order. With this in mind, I encourage financial experts and political leaders to ponder the words of one of the sages of antiquity: “Not to share one’s wealth with the poor is to steal from them and to take away their livelihood. It is not our own goods which we hold, but theirs”.[55]

58. A financial reform open to such ethical considerations would require a vigorous change of approach on the part of political leaders. I urge them to face this challenge with determination and an eye to the future, while not ignoring, of course, the specifics of each case. Money must serve, not rule! The Pope loves everyone, rich and poor alike, but he is obliged in the name of Christ to remind all that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor. I exhort you to generous solidarity and a return of economics and finance to an ethical approach which favours human beings.

No to the inequality which spawns violence

59. Today in many places we hear a call for greater security. But until exclusion and inequality in society and between peoples is reversed, it will be impossible to eliminate violence. The poor and the poorer peoples are accused of violence, yet without equal opportunities the different forms of aggression and conflict will find a fertile terrain for growth and eventually explode. When a society – whether local, national or global – is willing to leave a part of itself on the fringes, no political programmes or resources spent on law enforcement or surveillance systems can indefinitely guarantee tranquility. This is not the case simply because inequality provokes a violent reaction from those excluded from the system, but because the socioeconomic system is unjust at its root. Just as goodness tends to spread, the toleration of evil, which is injustice, tends to expand its baneful influence and quietly to undermine any political and social system, no matter how solid it may appear. If every action has its consequences, an evil embedded in the structures of a society has a constant potential for disintegration and death. It is evil crystallized in unjust social structures, which cannot be the basis of hope for a better future. We are far from the so-called “end of history”, since the conditions for a sustainable and peaceful development have not yet been adequately articulated and realized.

60. Today’s economic mechanisms promote inordinate consumption, yet it is evident that unbridled consumerism combined with inequality proves doubly damaging to the social fabric. Inequality eventually engenders a violence which recourse to arms cannot and never will be able to resolve. This serves only to offer false hopes to those clamouring for heightened security, even though nowadays we know that weapons and violence, rather than providing solutions, create new and more serious conflicts. Some simply content themselves with blaming the poor and the poorer countries themselves for their troubles; indulging in unwarranted generalizations, they claim that the solution is an “education” that would tranquilize them, making them tame and harmless. All this becomes even more exasperating for the marginalized in the light of the widespread and deeply rooted corruption found in many countries – in their governments, businesses and institutions – whatever the political ideology of their leaders.

Cool open-source models?

I’m looking to develop my idea of open models, which I motivated here and started to describe here. I wrote the post in March 2012, but the need for such a platform has only become more obvious.

I’m lucky to be working with a super fantastic python guy on this, and the details are under wraps, but let’s just say it’s exciting.

So I’m looking to showcase a few good models to start with, preferably in python, but the critical ingredient is that they’re open source. They don’t have to be great, because the point is to see their flaws and possible to improve them.

- For example, I put in a FOIA request a couple of days ago to get the current teacher value-added model from New York City.

- A friends of mine, Marc Joffe, has an open source municipal credit rating model. It’s not in python but I’m hopeful we can work with it anyway.

- I’m in search of an open source credit scoring model for individuals. Does anyone know of something like that?

- They don’t have to be creepy! How about a Nate Silver – style weather model?

- Or something that relies on open government data?

- Can we get the Reinhart-Rogoff model?

The idea here is to get the model, not necessarily the data (although even better if it can be attached to data and updated regularly). And once we get a model, we’d build interactives with the model (like this one), or at least the tools to do so, so other people could build them.

At its core, the point of open models is this: you don’t really know what a model does until you can interact with it. You don’t know if a model is robust unless you can fiddle with its parameters and check. And finally, you don’t know if a model is best possible unless you’ve let people try to improve it.

Twitter and its modeling war

I often talk about the modeling war, and I usually mean the one where the modelers are on one side and the public is on the other. The modelers are working hard trying to convince or trick the public into clicking or buying or consuming or taking out loans or buying insurance, and the public is on the other, barely aware that they’re engaging in anything at all resembling a war.

But there are plenty of other modeling wars that are being fought by two sides which are both sophisticated. To name a couple, Anonymous versus the NSA and Anonymous versus itself.

Here’s another, and it’s kind of bland but pretty simple: Twitter bots versus Twitter.

This war arose from the fact that people care about how many followers someone on Twitter has. It’s a measure of a person’s influence, albeit a crappy one for various reasons (and not just because it’s being gamed).

The high impact of the follower count means it’s in a wannabe celebrity’s best interest to juice their follower numbers, which introduces the idea of fake twitter accounts to game the model. This is an industry in itself, and an associated arms race of spam filters to get rid of them. The question is, who’s winning this arms race and why?

Twitter has historically made some strides in finding and removing such fake accounts with the help of some modelers who actually bought the services of a spammer and looked carefully at what their money bought them. Recently though, at least according to this WSJ article, it looks like Twitter has spent less energy pursuing the spammers.

It begs the question, why? After all, Twitter has a lot theoretically at stake. Namely, its reputation, because if everyone knows how gamed the system is, they’ll stop trusting it. On the other hand, that argument only really holds if people have something else to use instead as a better proxy of influence.

Even so, considering that Twitter has a bazillion dollars in the bank right now, you’d think they’d spend a few hundred thousand a year to prevent their reputation from being too tarnished. And maybe they’re doing that, but the spammers seem to be happily working away in spite of that.

And judging from my experience on Twitter recently, there are plenty of active spammers which actively degrade the user experience. That brings up my final point, which is that the lack of competition argument at some point gives way to the “I don’t want to be spammed” user experience argument. At some point, if Twitter doesn’t maintain standards, people will just not spend time on Twitter, and its proxy of influence will fall out of favor for that more fundamental reason.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is hung over from excess rabble rousing and karaoke, but she’s determined not to miss another week of her beloved advice column. Aunt Pythia has missed you! As I’m sure you’ve missed her! Please enjoy today’s column, and

please, don’t forget to ask Aunt Pythia a question at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I have an older sister. She’s a lovely and good person. Very generous, very friendly. And very assertive, in an oldest-child-in-the-family way.

I love my family, but I often feel depressed and suffocated when I’m around my sister. Is it because I feel she’s constantly giving input on how I could do things differently, and why she’s chosen to do things the way she does as if she has a PhD on the subject, and I often am left doubting my own abilities to make decisions even though I know that in reality I have a pretty good head on my shoulders? Maybe. Is it because of the authority she speaks on any topic, even ones she knows very little about? Is it because she doesn’t seem to entertain the possibility that anyone else could have anything to add in terms of input? Is it because she rarely shows any kind of vulnerability? Is it because she’s so assertive that it often feels like she’s taking up all of the oxygen in the room? Is it because she does all of these things even while, at the same, she is being utterly helpful, generous, and selfless in most other ways? Yeah, maybe that too.

Whatever it is, it hardly seems like a good reason to get depressed or to distance myself from someone who genuinely loves me and whom I love. I get that this is my issue, and the problem is how I feel about myself when I’m around her. I want to get over this. I just don’t know where to start.

Family Stuff

Dear Family Stuff,

To be honest I double- and triple-checked that I don’t have any younger siblings when I read this, because it could be about me. I could totally be that older sister, and I imagine that many people feel this way about me.

But if I’m right, and if your sister is a lot like me, then I don’t think it’s “your issue” to get over. I’m guessing it’s more like a series of signals that she’s giving out that are not hitting the intended targets. And if I’m right, she actually does want you to add stuff, but she expects you to jump right into the ring and not need an invitation.

So, when she gives advice, think of her words as her unedited thoughts, and do with those thoughts what you may. You can test this theory by every now and then pointing out, “I tried that already, it didn’t work” and see what she says. If she’s like, “Oh cool, how about trying this?” then you know she’s just taking stabs.

And, when she has an opinion on everything, maybe she’s just trying to engage in a provocative conversation and wants to be challenged. I do that all the time (duh). So next time she says something that sounds uninformed, say something like, “Hey that sounds wrong to me – should we check the facts?” and see how she reacts. She might be psyched for the challenge and for the chance to learn something interesting.

As for your sister showing no vulnerability. The funny thing about family is, we are our most vulnerable with our family, and yet we are also very comfortable with them, because we know them so well. You might be surprised by how vulnerable she really is. At the same time, you might not want to test this one, because it’s usually a negative experience to expose vulnerability in someone else. In any case my advice here is to not assume an entire lack of vulnerability around family, even if it looks like that.

Last piece of advice: go read my recent post called “Cathy’s Wager.” It’s about how to react when people are treating you not-so-nicely. I think it’s relevant here, because the overall point is that it’s not about you. Your sister is who she is and she’s very likely not doing all this stuff in order to make you feel stifled and depressed. She’s a know-it-all loudmouth, true, but the sooner you can either get on her wavelength (see above tips) or roll your eyes and love her in spite of her pushy know-it-all ways the better for you and for her. Don’t take it personally.

Either that or just never see her again. That’s totally fine too, honestly. I don’t agree that you have to hang out with family, unless possibly if they’re dying or in need.

I hope that helps!

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

What ever happened to the proof of the ABC conjecture by Mochizuki that you talked about a year ago?

Thanks,

Curious

Curious,

I unfortunately missed him when he came to Columbia, but Brian Conrad recently came and updated the math community on the status of the alleged proof. I believe the bottomline was that it has not been confirmed by anyone. So, I’d say this means it’s not a proof.

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This is a longtime worry of mine. Since you are a master of both abstract as well as the quantitative, let me query you regarding the deep connection that seems to exist between the two. To put it simply, the question is, “Does Size Matter?” More precisely, does Size influence tender feelings of the heart?

Sizeable Confusion

Dear SC,

I’d guess about as much as anything else physical, like boob size or leg length. In other words it might be a pretty big deal initially, as in during the first few minutes, but then when real love sets in it’s a total non-issue.

AP

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Many government officials testified that there is no way for them to tell how many people signed up for Obamacare. Can extracting the data from the website be that complicated? I am worried and lost.

Worried about Obamacare

Dear Worried,

Well many people have been busy counting this stuff since you submitted that question, and the final number for the first day of Obamacare seems to be 6. Given how small that number is, I’m going to assume it wasn’t that hard to count, or at least approximate at “0”. In other words, it might have been a political decision to repress the actual number.

On the other hand, engineering large-scale systems is actually pretty complicated, and it might not make sense to have a single repository to put all the enrollment figures – who knows, and I didn’t design this system, so I don’t – so I can imagine that it was actually non-trivial to figure out the answer to this question.

By the way, I’m planning to write some posts on how we are increasingly seeing pure engineering issues become political issues. There’s Knight Capital’s trading mistakes, then there’s Obamacare. Those are just two, but my theory is that they are just the beginning of a very long list. The nerds are taking over, in other words, or at least their mistakes are.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I sent you a question a few weeks back and you didn’t answer it (which is completely fine). What is your criteria for answering a question or not? Maybe your answer might help me rewrite my question in a way that suits you better.

Socially Awkward Dude

Dear SAD,

Here’s the thing. I’m pretty desperate over here, what with a pretty short list of questions, and a stubborn refusal on my part to make up fake questions (although I do accept other people’s fake questions!). So there had to be something about your question that didn’t sit well with me. Here are some possibilities as to why:

- The question was something I couldn’t answer, because it required expertise I don’t have.

- The question was really long and not easily edited down to something shortish.

- The question wasn’t really a question, just a rambling speech.

- The question was spam.

- The question was verbally abusive towards me.

- The question struck me as disingenuous in some way.

- The question is a lot like other questions I’ve already answered (note to the 40 people asking me how to become a data scientist: read my book called Doing Data Science!)

I have no idea which question was yours, but if you’d care to resubmit, making sure it’s to the point, has a specific and earnest question, and is about something I have knowledge about, then I’m guessing it will get through.

I hope that helps!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a late-20’s data scientist (working at a large non-tech company) about to apply for Ph.D. programs in machine learning. My reason for doing this is two-fold. One, I enjoy research and feel that I can contribute to humanity through scholarship, even if the contribution may be small. Two, I’ve grown disillusioned with working in a corporate environment – it seems like one needs to be more of a politician than a genuinely nice and high-performing individual to be recognized. But I realize this is partly due to the size of my organization (are start-ups any different?).

However, I’ve heard people tell me that academia is no different. Given the publish-or-perish paradigm, people are more interested in how many citations they have than they are about truly advancing human knowledge (for example, this was a depressing read).

You transitioned from academia into industry. Do you have any advice for someone who’s trying to make the opposite transition?

Naively Bayesian

Dear NB,

First of all, start-ups are sometimes different, although they work you really hard and often expect you to sleep under your desk. This might not work for you, but it might be worth it if you get to have influence. Also, I’d suggest going with a very small start-up: as soon as there are like 60 people, your potential influence typically gets pretty miniscule.

Second, my motto is “You never get rid of your problems, you just get a new set of problems.” So it’s more a question of which kinds of problems suit your personality than anything else.

But there’s one thing I can assure you: there’s politics everywhere. You’re not getting away from that, so if you’re really allergic to politics, I suggest you find a place where you can safely ignore that stuff, like maybe in a cave in the woods.

But seriously, I’d suggest you talk to a lot of people and see what kind of problems are there, without exaggerating them too much (I feel like that link is too aggressive for example, although there are grains of truth in it). And most importantly, try to find something to do that actually interests you in an intellectual way so you can become absorbed in your own sense of curiosity and shut out the real world at least once a day. Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

People don’t get fired enough

This might surprise some of you – or not, I’m not sure. But one of the most satisfying things about leaving academia and the tenure system and going into industry is how, at least in the ideal situation, you can get fired for not doing your job.

In fact, one of the reasons I decided to leave academia is that I really thought some of my colleagues weren’t doing right by the undergraduates, and the frustrating thing was that there was essentially no way to force them to start. Tenure has great aspects and not-so-great aspects, and a total lack of leverage is not a great one. I feel for deans sometimes.

Here’s the dirty little secret of lots of industry jobs, though: lots of time people also don’t get fired when they should. And sometimes it’s super awful bullies who yell and scream and act inappropriately but also pull in amazing sales numbers. There are things like that, of course. That’s the example of how they don’t abide by the alleged social contract but they perform on the bottomline. Social contracts are hard to quantify and somewhat squishy. You see people getting away with stuff because they’re rainmakers or higher ups.

But there are also plenty of examples of people just not doing their job, and having super awful attitudes, or even just completely apathetic attitudes, and for whatever reason they don’t get fired. This demoralizes and irritates and distracts everyone around them, because they all resent the free-rider.

Plus, retaining people who should by all accounts get fired makes the veneer of the kool-aid drinking camaraderie even more flimsy and scrutinizable – what’s so great about working here if people can just slack off and not care? Why do I give two shits about this project anyway? How does this project in the larger scheme of things? Maybe that scrutiny is a good thing – I engage in it myself – but you don’t want everyone thinking that all the time.

Here’s the thing, before you think I’m super vicious and mean to want people to get fired. These people I’m talking about are generally high skilled and temporarily depressed. They’re in the wrong job. And once fired, they will find another job, which will hopefully be a better one for them. I’m not saying that nobody will ever end up jobless and homeless, but very few, and moreover there are plenty of jobless and homeless people who would be psyched to do that job really well (putting aside how difficult it is for homeless people to get seriously considered for a job).

And I’m not saying you fire people out of the blue. You definitely need to tell people they’re not performing well (or that they are) and keep them in the feedback loop on whether things are working out. But in my experience people who deserve to get fired totally know it and can’t believe their luck that they’ve not been fired yet.

To conclude, I’m going on record saying I kind of agree with Jack Welch on this issue in a way I never thought I would.

Cathy’s Wager

I know you guys might be getting kind of exhausted from all the oversharing that’s been happening on mathbabe this week. I am too. But let me finish the phase with one piece of advice which I hope you find helpful.

I call it “Cathy’s Wager” (h/t Chris Wiggins) in reference to a much more famous and better idea called Pascal’s Wager. That, you may remember, is the argument that you might as well be a good person because there’s either a god, who cares, or there isn’t, in which case you haven’t lost all that much.

So here’s my version, and it refers to how other people treat you and how you react. I’ll assume most people treat you nicely most of the time, and then sometimes someone doesn’t treat you nicely. How do you react?

My theory is that you always assume it’s something they’re going through, and you try to never take it personally. Here are some examples.

- You’re friends with someone and all of a sudden they stop writing back to your emails. Assume they’re going through something, maybe a depression, maybe a break-up, maybe they just fell in love or moved jobs. It’s not about you and you shouldn’t take it personally. Consider writing to them and saying you’re there for them if they need a friend, or just do nothing and let them take their time, depending on how close a friend they are and how likely each of those scenarios is. Err on the side of compassion, not blame.

- You’re trying to set up a meeting with someone professionally and they never get back to you, or even worse, they don’t show up for the planned meeting and never explain why. First, always assume this has nothing to do with you. Maybe the got into a fight with their significant other, maybe they just got fired. You have no idea. But in order to avoid this from happening, do remember to confirm business meetings the day of, if it’s in the afternoon, or the afternoon before, if it’s in the morning, especially if the meeting was made more than a week in advance.

- You have what you think is an interesting if provocative conversation with someone and they never talk to you again, and you hear 2nd or 3rd hand (or both) that they hate your guts. Again, it’s not about you. There was some trigger in that conversation, and yes if you want to be sensitive you could try to go back over the conversation in your head and figure out what the heck happened. Do it once, but if you are convinced you meant no offense, then assume that person is going through something. They might even get over it and want to make up someday. Who knows, maybe part of what they like in life is getting offended and complaining. For example, maybe they take this article to heart entitled “The 14 Habits of Highly Miserable People.”

- Someone gets into your face and tells you you’re an awful person and are being mean to them for whatever reason. Not about you.

As I’m sure you can see, the assumption that “it’s not about me” is super useful and time-saving. I use it a lot, which means I don’t spend a lot of time second guessing myself or trying to change things that I can’t change about other people’s feelings. It’s kind of a selfish version of the Serenity Prayer, if you will, without all the religious stuff.

And this is not to say I don’t spend time trying to mend differences and reach out to my friends! I totally do! I just don’t feel personally affected if it doesn’t work. And I think that actually helps me do it more often in the end.

One caveat: the above examples work pretty well unless you are actually an awful person. I’m assuming you’re not. If you are actually a bad person, please don’t rely on Cathy’s Wager, thanks. Of course that begs the question of whether anyone actually thinks they’re awful, and if you go there, consider the idea that awful people are already using Cathy’s Wager, so you may as well too.

I’m already fat so I may as well be smart

I seem to be in a mood this week for provocative posts about body image and appearance (maybe this is what happens when I skip an Aunt Pythia column). Apologies to people who came for math talk.

I just wanted to mention something positive about the experience of being fat all my life, but especially as a school kid. Because just to be clear, this isn’t a phase. I’ve been pudgy since I was 2 weeks old. And overall it kind of works for me, and I’ll say why.

Namely, being a fat school kid meant that I was so uncool, so outside of normal social activity with boys and the like, that I was freed up to be as smart and as nerdy as I wanted, with very little stress about how that would “look”. You’re already fat, so why not be smart too? You’re not doing anything else, nobody’s paying attention to you, and there’s nothing to gossip about, so might as well join the math team.

It’s really a testament to both the pressure to be thin and the pressure to conform intellectually, i.e. not be a nerd, when you’re a young girl: they are both intense and super unpleasant. The happy truth is, one can be cover for the other. More than that, really: being fat (or “overweight” for people who are squeamish about the word “fat”) has opened up many doors that I honestly think would have, or at least could have, remained shut had I been more socially acceptable.

Going back to dress code at work for a moment: while people claim that corporate dress codes are meant to keep our minds off of sex, that is clearly a huge lie when it comes to many categories of women’s work clothes. Who are we kidding? The mere fact that many women wear high heels to work kind of says it all. And that’s fine, but let’s freaking acknowledge it.

On the other hand, it’s pretty hard to look sexy in a plus-sized suit (although not impossible), and the idea of high heels at work is just nuts. This ends up being a weirdly good thing for me, though: people take me more seriously because I have taken myself out of the sex game altogether – or at least the traditional sex game.

By the way, I’m not saying all fat women have the same perspective on it. I’m lucky enough to have figured out pretty early on how to separate other people’s projected feelings about my body from my own feelings. I am an observer of fat hatred, in other words. That doesn’t make me entirely insulated but it does give me one critical advantage: I have a lot of time on my hands to do stuff that I might otherwise spend fretting about my body.

It also might help partly explain why some girls get on the math team and others don’t. Being fat is something you don’t have control over (the continuing and damaging myth that each person does have control over it notwithstanding) but joining the math team is something you do have control over. And if you aren’t already excluded for some other reason (being fat is one but by no means the only way this could happen of course), you might not want to start that whole thing intentionally. Just a theory.

One reason corporate culture sucks for women

Am I the only person offended by the recent wave of articles wherein “senior women” at corporate offices are going around telling “younger women” about the appropriate dress code?

For example, here’s the beginning of a WSJ piece on just that subject:

Clothes may make the man. Can they undo the woman?

When female employees at Frontier Communications Corp. show up at its headquarters in very short skirts, sweatpants or sneakers, Chief Executive Maggie Wilderotter sometimes pulls them aside for a quick, private chat on dressing for success.

“I want women to be paid attention to for what they say–and not how they look,” explains Ms. Wilderotter.

Later in the article the explain why this is ok:

Women face more pitfalls because they have more clothing choices than men. And because male bosses fear being accused of sexual harassment, it usually falls to female supervisors to confront an associate about her attire.

This is one reason I hate corporate jobs. And yes, it’s because I come from academia and because I’m essentially a hippie, but seriously, why do we need so much policing? Why can’t people just leave each other alone to express themselves? It’s also a double standard:

Rosalind Hudnell, human resources vice president of Intel Corp., occasionally intervenes when she sees young female staffers clad unprofessionally, even though Intel staffers often wear shorts and jeans.

It’s just another in a long list of things you are scrutinized on if you’re a woman. In addition to whether you are a good mother, a feminine-enough-without-being-too-feminine employee, and, as a tertiary issue, if that, whether you actually do your job well. Fuck this.

Question for you readers: what does it really mean that these “senior women” are taking it upon themselves to scrutinize and criticize young women? Am I wrong, is it actually generous? Or is it some kind of hazing thing? Or is it a media invention that doesn’t actually happen?

Debunking Economic Myths #OWS

Yesterday in Alt Banking we were honored to have Suresh Naidu visit us to talk about and debunk economic myths.

The first myth, and the one we spent the most time on, is the idea that people “deserve” the money they earn because it is an accurate measure of their “added value” to society.

There are two parts of this, or actually at least two parts.

First, there’s the idea that you can even dissect the meaning of one person’s value. And if you can, it’s likely a question of a marginal value: what does our society look like without Steve Jobs, and then with him, and what’s the difference between the two worlds? As soon as you say it, you realize that such a thought experiment is complicated, considering the extent to which Steve Jobs’ journey intersected with other people’s like Steve Wozniak and a huge crowd of Chinese workers.

If you think about it some more, you might conclude that the marginal value of a single person is impossible to actually measure, at least with any precision, and not just because of the counterfactual problem, i.e. the problem that we only have one universe and can’t run two parallel universes at the same time. It’s really because any one person succeeds or fails, or more generally contributes, within a context of an entire culture. Even Mozart wrote his symphonies within a cultural context. In another context he would have been a kid who hums to himself a lot.

Second, there’s the assumption that people who earn a lot of money are actually adding value at all. This isn’t clear, and you don’t need to refer to formally criminal acts to make that case (although of course there are plenty of rich people who have committed criminal acts).

In many examples of super rich people, they got that way through not paying for negative externalities like polluting the environment, or because they had control of the legal mechanisms to reap profits off of other peoples’ work. Not technically illegal, then, but also not exactly a fair measure of their added value.

Or, of course, if they worked in finance, they might have made money by keeping stuff incredibly complicated and opaque while providing liquidity to the credit markets. It’s not clear that such work has added any value to society, or if it has, whether it’s balanced the good with the bad.

Some observations about this myth that were brought up include:

- There’s a deep belief in “the markets” at work here which is rather cyclical. The market values you more than other people which is why you’re paid so well for whatever it is you do. Other people who have less to offer the market are get paid less. Anyone who doesn’t have a job doesn’t deserve a job since the market isn’t offering them a job, which must mean they are adding no value.

- There are exceptions where people add obvious value – caretakers of our children for example – but aren’t paid well. This is because of a different mechanism called supply and demand. For whatever reason supply and demand isn’t at work at high ends of the market.

- Or maybe it is and there’s really only one possible person who could do what Steve Jobs did. Personally I don’t buy it. And I chose Steve Jobs because so many people love that guy, but really he’s one of the best examples of someone who might have had a unique talent. Most rich people are generically good at their job and not all that unique.

- It’s mostly the people that benefit from the market system that believe in it. That kind of reminds me of the marshmallow study, or rather one of the many re-interpretations of the marshmallow study. See the latest one here.

- It’s patently difficult to believe in the market system if you consider a lack of equality of opportunity in this country due to extreme differences in school systems and the like. I’m about to start reading this book which explains this issue in depth.

- For other evidence, look at Pimco’s Bill Gross’s recent confessions about being born at the right time with easy access to credit.

- The unequal access of opportunities in this country is becoming increasingly entrenched, and as it does so the myth of the market giving us what we deserve is becoming increasingly difficult to swallow.

Crisis Text Line: Using Data to Help Teens in Crisis

This morning I’m helping out at a datadive event set up by DataKind (apologies to Aunt Pythia lovers).

The idea is that we’re analyzing metadata around a texting hotline for teens in crisis. We’re trying to see if we can use the information we have on these texts (timestamps, character length, topic – which is most often suicide – and outcome reported by both the texter and the counselor) to help the counselors improve their responses.

For example, right now counselors can be in up to 5 conversations at a time – is that too many? Can we figure that out from the data? Is there too much waiting between texts? Other questions are listed here.

Our “hackpad” is located here, and will hopefully be updated like a wiki with results and visuals from the exploration of our group. It looks like we have a pretty amazing group of nerds over here looking into this (mostly python users!), and I’m hopeful that we will be helping the good people at Crisis Text Line.

On being a mom and a mathematician: interview by Lillian Pierce

This is a guest post by Lillian Pierce, who is currently a faculty member of the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics in Bonn, and will next year join the faculty at Duke University.

I’m a mathematician. I also happen to be a mother. I turned in my Ph.D. thesis one week before the due date of my first child, and defended it five weeks after she was born. Two and a half years into my postdoc years, I had my second child.

Now after a few years of practice, I can pretty much handle daily life as a young academic and a parent, at least most of the time, but it still seems like a startlingly strenuous existence compared to what I remember of life as just a young academic, not a parent.

Last year I was asked by the Association for Women in Mathematics to write a piece for the AWM Newsletter about my impressions of being a young mother and getting a mathematical career off the ground at the same time. I suggested that instead I interview a lot of other mathematical mothers, because it’s risky to present just one view as “the way” to tackle mathematics and motherhood.

Besides, what I really wanted to know was: how is everyone else doing this? I wanted to pick up some pointers.

I met Mathbabe about ten years ago when I was a visiting prospective graduate student and she was a postdoc. She made a deep impression on me at the time, and I am very happy that I now have the chance to interview her for the series Mathematics+Motherhood, and to now share with you our conversation.

LP: Tell me about your current work.

CO: I am a data scientist working at a small start-up. We’re trying to combine consulting engagements with a new vision for data science training and education and possibly some companies to spin off. In the meantime, we’re trying not to be creepy.

LP: That sounds like a good goal. And tell me a bit about your family.

CO: I have three kids. I got pregnant with my first son, who’s 13 now, soon after my PhD. Then I had a second child 2 years later, also while I was a postdoc. I also have a 4 year old, whom I had when I was working in finance.

LP: Did you have any notions or worries in advance about how the growth of your family would intersect with the growth of your career?

CO: I absolutely did worry about it, and I was right to worry about it, but I did not hesitate about whether to have children because it was just not a question to me about how I wanted my life to proceed. And I did not want to wait until I was tenured because I didn’t want to risk being infertile, which is a real risk. So for me it was not an option not to do it as a woman, forget as a mathematician.

LP: What was it like as a postdoc with two very young children?

CO: On the one hand I was hopeful about it, and on the other hand I was incredibly disappointed about it. The hopeful part was that the chair of my department was incredibly open to negotiating a maternity leave for postdocs, and it really was the best maternity policy that I knew about: a semester off of teaching for each baby and in total an extra year of the postdoc, since I had 2 babies. So I ended up with four years of postdoc, which was really quite generous on the one hand, but on the other hand it really didn’t matter at all. Not “not at all”—it mattered somewhat but it simply wasn’t enough to feel like I was actually competing with my contemporaries who didn’t have children. That’s on the one hand completely obvious and natural and it makes sense, because when you have small children you need to pay attention to them because they need you—and at the same time it was incredibly frustrating.

LP: It’s interesting because it’s not that you were saying “I won’t be able to compete with my contemporaries over the course of my life,” but more “I can’t compete right now.”

CO: Exactly, “I can’t compete right now” with postdocs without children. I realize—and this is not a new idea—that mathematics as a culture frontloads entirely into those 3 or 4 years after you get your PhD. Ultimately it’s not my fault, it’s not women’s fault, it’s the fault of the academic system.

LP: What metrics could departments use to be thinking more about future potential?

CO: I actually think it’s hard. It’s not just for women that it should change. It’s for the actual culture of mathematics. Essentially, the system is too rigid. And it’s not only women who get lost. The same thing that winnows the pool down right after getting a PhD—it’s a whittling process, to get rid of people, get rid of people, get rid of people until you only have the elite left—that process is incredibly punishing to women, but it’s also incredibly punishing to everybody. And moreover because of the way you get tenure and then stay in your field for the rest of your life, my feeling is that mathematics actually suffers. The reason I say this is because I work in industry now, which is a very different system, and people can reinvent themselves in a way that simply does not happen in mathematics.

LP: Do you think industry, in terms of the young career phase, gets it closer to “right” than academia currently does?

CO: Much closer to right. It’s a brutal place, don’t get me wrong, it’s brutal. I’m not saying it’s a perfect system by any stretch of the imagination. But the truth is in industry you can have a 3 year stint somewhere that is a mistake. Forget having kids, you can have a 3 year stint that was just a mistake for you. You can say “I had a bad boss and I left that place and I got a new job” and people will say “Ok.” They don’t care. One thing that I like about it is the ability to reinvent yourself. And I don’t think you see that in math. In math, your progress is charted by your publication record at a granular level. And if you’re up for tenure and there’s a 3 year gap where you didn’t publish, even if in the other years you published a lot, you still have to explain that gap. It’s like a moral responsibility to keep publishing all the time.

LP: How are you measured in industry?

CO: In industry it’s the question “what have you done for me,” and “what have you done for me lately.” It’s a shorter-term question, and there are good elements to that. One of the good elements is that as a woman you can have a baby or a couple babies and then you can pick up the slack, work your ass off, and you can be more productive after something happens. If someone gets sick, people lower their expectations for that person for some amount of time until they recover, and then expectations are higher. Mathematics by contrast has frontloaded all of the stress, especially for the elite institutions, into the 3 or 4 years to get the tenure track offer and then the next 6 years to get tenure. And then all the stress is gone. I understand why people with tenure like that. But ultimately I don’t think mathematics gets done better because of it. And certainly when the question arises “why don’t women stay in math,” I can answer that very easily: because it’s not a very good place for women, at least if they want kids.

LP: You mention on your blog that your mother is an unapologetic nerd and computer scientist; the conclusion you drew from that was that it was natural for you not to doubt that your contributions to nerd-dom and science and knowledge would be welcomed. How do you think this experience of having a mother like that inoculated you?

CO: One of the great gifts that my mother gave me as a Mother Nerd was the gift of privacy—in the sense that I did not scrutinize myself. First of all she was role-modeling something for me, so if I had any expectations it would be to be like my mom. But second of all she wasn’t asking me to think about that. I think that was one of the rarest things I had, the most unusual aspect of my upbringing as a girl. Very few of the girls that I know are not scrutinized. My mother was too busy to pay attention to my music or my art or my math. And I was left alone to decide what I wanted to do—it wasn’t about what I was good at or what other people thought of my progress. It was all about answering the question, what did I want to do. Privacy for me is having elbow space to self-define.

LP: Do you think it’s harder for parents to give that space to girls than to boys?

CO: Yes I do, I absolutely do. It’s harder and for some reason it’s not even thought about. My mother also gave me the gift of not feeling at all guilty about putting me into daycare. And that’s one of my strongest lessons, is that I don’t feel at all guilty about sending my kids to daycare. In fact I recently had the daycare providers for my 4-year-old all over for dinner, and I was telling them in all honesty that sometimes I wish I could be there too, that I could just stay there all day, because it’s just a wonderful place to be. I’m jealous of my kids. And that’s the best of all worlds. Instead of saying “oh my kid is in daycare all day, I feel bad about that,” it’s “my kid gets to go to daycare.”

LP: Where did this ability not to scrutinize come from? Where did your mother get this?

CO: I don’t know. My mother has never given me advice, she just doesn’t give advice. And when I ask her to, she says “you know more about your life than I do.”

LP: How do you deal with scrutiny now?

CO: It’s transformed as I’ve gotten older. I’ve gotten a thicker skin, partly from working in finance. I’ve gotten to the point now where I can appreciate good feedback and ignore negative feedback. And that’s a really nice place to be. But it started out, I believe, because I was raised in an environment where I wasn’t scrutinized. And I had that space to self-define.

LP: The idea of pushing back against scrutiny to clear space for self-definition is inspiring for adults as well.

CO: Women in math, especially with kids, give yourself a break. You’re under an immense amount of pressure, of scrutiny. You should think of it as being on the front lines, you’re a warrior! And if you’re exhausted, there’s a reason for it. Please go read Radhika Nagpal’s Scientific American blog post (“The Awesomest 7-Year Postdoc Ever”) for tips on how to deal with the pressure. She’s awesome. And the last thing I want to say is that I never stopped loving math. Cardinal Rule Number 1: Before all else, don’t become bitter. Cardinal Rule Number 2: Remember that math is beautiful.

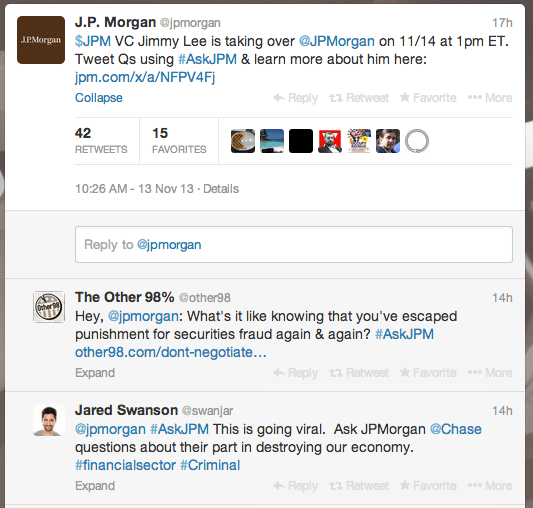

#AskJPM and public shaming #OWS

I don’t usually shill for companies but this morning I’m completely into how much of a circus my Twitter feed became yesterday when JP Morgan Chase’s PR team decided to open up to the public for questions. You can see from the immediate replies how this was going to go:

The questions asked which were tagged with #AskJPM are stunning and constitute a well-deserved public shaming of JP Morgan.

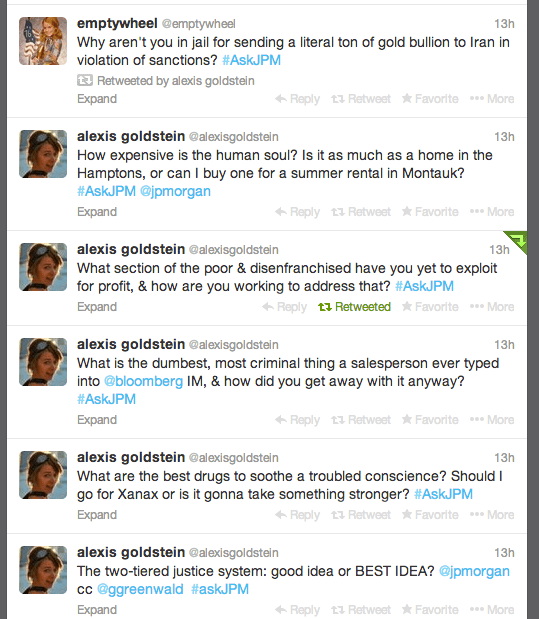

My friend and co-occupier Alexis Goldstein was absolutely killing it on Twitter, as usual. Here’s just a snippet from her feed:

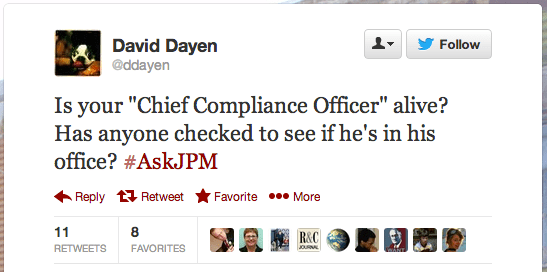

See also Dave Dayen’s choice question:

Needless to say the Q&A was canceled, but not until the #AskJPM hashtag went viral in an amazing way. See more examples here and here.

Update: Watch #AskJPM tweets read by Stacy Keach live on CNBC!!

You are not a loan: Rolling Jubilee eradicates $15,000,000 worth of debt #OWS

This is super cool. Occupy Wall Street’s Strike Debt group has bought up almost $15 million dollars worth of mostly medical debt which was owned by 2,700 people across 45 states and Puerto Rico. They used donations they’ve been collecting over the last year. There’s more information about this action in this Guardian piece.

Here’s what I like about this. By freeing people of medical debt in particular, which is the biggest cause of bankruptcy filings, it emphasizes the lie of the “moral sin” often associated with crushing debt.

In other words, instead of imagining poor and debt-ridden people as lazy and glibly unable to keep their promises, the Rolling Jubilee action bestows a much-needed act of compassion for some of the millions of the unlucky people in this country caught in a dysfunctional health and credit system.

And while it’s true that it is making a small dent in the debt problem, in dollars and cents terms, I think the Strike Debt’s debt action, and its Debt Resistors’ Operation Manual, has made huge strides in how people think about debt in this country, which is tremendously important.

There is no “market solution” for ethics

We saw what happened in finance with self-regulation and ethics. Let’s prepare for the exact same thing in big data.

Finance

Remember back in the 1970’s through the 1990’s, the powers that were decided that we didn’t need to regulate banks because “they” wouldn’t put “their” best interests at risk? And then came the financial crisis, and most recently came Alan Greenspan’s recent admission that he’d got it kinda wrong but not really.

Let’s look at what the “self-regulated market” in derivatives has bestowed upon us. We’ve got a bunch of captured regulators and a huge group of bankers who insist on keeping derivatives opaque so that they can charge clients bigger fees, not to mention that they insist on not having fiduciary duties to their clients, and oh yes, they’d like to continue to bet depositors’ money on those derivatives. They wrote the regulation themselves for that one. And this is after they blew up the world and got saved by the taxpayers.

Given that the banks write the regulations, it’s arguably still kind of a self-regulated market in finance. So we can see how ethics has been and is faring in such a culture.

The answer is, not well. Just in case the last 5 years of news articles wasn’t enough to persuade you of this fact, here’s what NY Fed Chief Dudley had to say recently about big banks and the culture of ethics, from this Huffington Post article:

“Collectively, these enhancements to our current regime may not solve another important problem evident within some large financial institutions — the apparent lack of respect for law, regulation and the public trust,” he said.

“There is evidence of deep-seated cultural and ethical failures at many large financial institutions,” he continued. “Whether this is due to size and complexity, bad incentives, or some other issues is difficult to judge, but it is another critical problem that needs to be addressed.”

Given that my beat is now more focused on the big data community and less on finance, mostly since I haven’t worked in finance for almost 2 years, this kind of stuff always makes me wonder how ethics is faring in the big data world, which is, again, largely self-regulated.

Big data

According to this ComputerWorld article, things are pretty good. I mean, there are the occasional snafus – unappreciated sensors or unreasonable zip code gathering examples – but the general idea is that, as long as you have a transparent data privacy policy, you’ll be just fine.

Examples of how awesome “transparency” is in these cases vary from letting people know what cookies are being used (BlueKai), to promising not to share certain information between vendors (Retention Science), to allowing customers a limited view into their profiling by Acxiom, the biggest consumer information warehouse. Here’s what I assume a typical reaction might be to this last one.

Wow! I know a few things Acxiom knows about me, but probably not all! How helpful. I really trust those guys now.

Not a solution

What’s great about letting customers know exactly what you’re doing with their data is that you can then turn around and complain that customers don’t understand or care about privacy policies. In any case, it’s on them to evaluate and argue their specific complaints. Which of course they don’t do, because they can’t possibly do all that work and have a life, and if they really care they just boycott the product altogether. The result in any case is a meaningless, one-sided conversation where the tech company only hears good news.

Oh, and you can also declare that customers are just really confused and don’t even know what they want:

In a recent Infosys global survey, 39% of the respondents said that they consider data mining invasive. And 72% said they don’t feel that the online promotions or emails they receive speak to their personal interests and needs.

Conclusion: people must want us to collect even more of their information so they can get really really awesome ads.

Finally, if you make the point that people shouldn’t be expected to be data mining and privacy experts to use the web, the issue of a “market solution for ethics” is raised.

“The market will provide a mechanism quicker than legislation will,” he says. “There is going to be more and more control of your data, and more clarity on what you’re getting in return. Companies that insist on not being transparent are going to look outdated.”

Back to ethics

What we’ve got here is a repeat problem. The goal of tech companies is to make money off of consumers, just as the goal of banks is to make money off of investors (and taxpayers as a last resort).

Given how much these incentives clash, the experts on the inside have figured out a way of continuing to do their thing, make money, and at the same time, keeping a facade of the consumer’s trust. It’s really well set up for that since there are so many technical terms and fancy math models. Perfect for obfuscation.

If tech companies really did care about the consumer, they’d help set up reasonable guidelines and rules on these issues, which could easily be turned into law. Instead they send lobbyists to water down any and all regulation. They’ve even recently created a new superPAC for big data (h/t Matt Stoller).

And although it’s true that policy makers are totally ignorant of the actual issues here, that might be because of the way big data professionals talk down to them and keep them ignorant. It’s obvious that tech companies are desperate for policy makers to stay out of any actual informed conversation about these issues, never mind the public.

Conclusion

There never has been, nor there ever will be, a market solution for ethics so long as the basic incentives between the public and an industry are so misaligned. The public needs to be represented somehow, and without rules and regulations, and without leverage of any kind, that will not happen.

How do I know if I’m good enough to go into math?

Hi Cathy,

I met you this past summer, you may not remember me. I have a question.

I know a lot of people who know much more math than I do and who figure out solutions to problems more quickly than me. Whenever I come up with a solution to a problem that I’m really proud of and that I worked really hard on, they talk about how they’ve seen that problem before and all the stuff they know about it. How do I know if I’m good enough to go into math?

Thanks,

High School Kid

Dear High School Kid,

Great question, and I’m glad I can answer it, because I had almost the same experience when I was in high school and I didn’t have anyone to ask. And if you don’t mind, I’m going to answer it to anyone who reads my blog, just in case there are other young people wondering this, and especially girls, but of course not only girls.

Here’s the thing. There’s always someone faster than you. And it feels bad, especially when you feel slow, and especially when that person cares about being fast, because all of a sudden, in your confusion about all sort of things, speed seems important. But it’s not a race. Mathematics is patient and doesn’t mind. Think of it, your slowness, or lack of quickness, as a style thing but not as a shortcoming.

Why style? Over the years I’ve found that slow mathematicians have a different thing to offer than fast mathematicians, although there are exceptions (Bjorn Poonen comes to mind, who is fast but thinks things through like a slow mathematician. Love that guy). I totally didn’t define this but I think it’s true, and other mathematicians, weigh in please.

One thing that’s incredibly annoying about this concept of “fastness” when it comes to solving math problems is that, as a high school kid, you’re surrounded by math competitions, which all kind of suck. They make it seem like, to be “good” at math, you have to be fast. That’s really just not true once you grow up and start doing grownup math.

In reality, mostly of being good at math is really about how much you want to spend your time doing math. And I guess it’s true that if you’re slower you have to want to spend more time doing math, but if you love doing math then that’s totally fine. Plus, thinking about things overnight always helps me. So sleeping about math counts as time spent doing math.

[As an aside, I have figured things out so often in my sleep that it’s become my preferred way of working on problems. I often wonder if there’s a “math part” of my brain which I don’t have normal access to but which furiously works on questions during the night. That is, if I’ve spent the requisite time during the day trying to figure it out. In any case, when it works, I wake up the next morning just simply knowing the proof and it actually seems obvious. It’s just like magic.]

So here’s my advice to you, high school kid. Ignore your surroundings, ignore the math competitions, and especially ignore the annoying kids who care about doing fast math. They will slowly recede as you go to college and as high school algebra gives way to college algebra and then Galois Theory. As the math gets awesomer, the speed gets slower.

And in terms of your identity, let yourself fancy yourself a mathematician, or an astronaut, or an engineer, or whatever, because you don’t have to know exactly what it’ll be yet. But promise me you’ll take some math major courses, some real ones like Galois Theory (take Galois Theory!) and for goodness sakes don’t close off any options because of some false definition of “good at math” or because some dude (or possibly dudette) needs to care about knowing everything quickly. Believe me, as you know more you will realize more and more how little you know.

One last thing. Math is not a competitive sport. It’s one of the only existing truly crowd-sourced projects of society, and that makes it highly collaborative and community-oriented, even if the awards and prizes and media narratives about “precocious geniuses” would have you believing the opposite. And once again, it’s been around a long time and is patient to be added to by you when you have the love and time and will to do so.

Love,

Cathy

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is well-slept and excited to be here to answer your wonderful and thoughtful ethical conundrums. Please do comment on my answers, if you disagree but especially if you agree wholeheartedly and want me to keep up the good work. Love that kind of encouraging comment.

And please, don’t forget to ask me a question at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What is your text editor of choice? The most popular ones, the ones in which I know die-hard fans, are for Emacs, Vi/Vim, and Sublime. I am personally an Emacs user, but I haven’t given any other editors a chance, to be honest. Which do you prefer to use, and why?

Text Editor

Dear TE,

I use emacs mostly, and xemacs when it’s available. It’s easy, it “knows” about python and other languages, and the drop-down menu is easier than remembering keystroke commands. I’ve been known to use an IDE or two depending on codebase context. For me it’s all about ease of use and, since I’ve never been a professional engineer and so I’ve never spent a large majority of my time with source code, vim doesn’t attract me, even though everything is keystroke and you never need to use your mouse.

As an aside, I’d like to argue this point, because it’s often shrouded in weird macho crap: why not use your mouse? Does it really waste that much time? I honestly have never been prevented from coding efficiently because my arm is too tired from moving from the keyboard to the mouse and back. Is the goal really to be able to stay in the exact same position for as long as possible? I’m the kind of person that is too fidgety for such ideas. I take the “stand up and walk around every 20 minutes” rule seriously, at least before 4pm, when I become a zombie.

Good luck, young padawan!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What are your thoughts on the famous (infamous?) two-daughter problem? I have three PhDs who give different answers all of which appear to be statistically correct. Modinow says the answer is 1/2. The chair of the stats department at local university says the answer is 3/7, and a chap at Fl Coastal College has yet a 3rd answer which I have lost.

How can this be?

Tombs

Dear Tombs,

OK I’m pretty sure there’s only one answer to this if it’s stated precisely. So let’s try to do that. Here’s the question:

Suppose I have two children. One of them is a girl who was born on a Friday. What are the chances of both children being girls?

Now I’m a big fan of making things incredibly easy and visual. So what I’m going to do here is identify the fact that, as far as children go, there are two attributes of interest in this question, namely gender and day of birth. I will assume that all options are equally likely and that they are independent from each other as well as between kids, and in my first iteration I’ll draw up a list of equally likely bins for a given child, namely of either gender and of any day born. That’s 14 equally likely bins for a given single child, and that means they happen with probability 1/14.

Now, for the second iteration, let’s talk about having two kids. You have a 2-dimensional array of bins, which you arrange to be 14-by-14, and you assume that any of those 14*14 = 196 bins is a priori equally likely.

Label the bins with ordered pairs (gender, day). The x-axis is first kid, y-axis is 2nd kid. Each bin equally likely.

If you label the first bin as “(Female, Friday)” and the second bin as “(Female, Saturday)” and so on, you realize that the condition that “one of the two kids is a girl who was born on Friday” means that we already know we are working in the context where we are either in the left-most column or the bottom row. Here’s my awesome rendition of this area:

Specifically, the left bottom corner is the case where there are two girls, both born on Friday. The one to the right and above that corner refers to the case where there are two girls, one born on Friday and one born on Saturday. The stuff on the right and in the upper part of the column refers to the case where there’s a Friday girl and a boy.

Altogether we have 13 pink bins with two girls and 14 pink bins of a boy and a girl. So the overall chances of two girls, given one Friday girl, is 13/27.

I hope that’s convincing!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Auntie P,

What do you think about topological data analysis (some info here). Should we trust people who can’t tell the difference between their rear end and a coffee cup because the two are topologically equivalent?

Topological Fear

Dear TF,

Geez I don’t know about you but my rear end is not topologically equivalent to my coffee cups. You either need to go to a doctor or buy some coffee cups that don’t leak.

So, I don’t know very much about this stuff, but I do think it’s potentially interesting, and it’s maybe close to an idea I’ve had for a while now but for which I haven’t found a practical use. Yet.

The idea I have had, if it’s close to this idea, and I think from short conversations with people that it is, is that if you draw a bunch of scatter plots of, say, two attributes x1 and x2 and an outcome y (so you need numerical data for this), then you’ll notice in the resulting 3-dimensional blob of points some interesting topological properties. Namely, there seem to be pretty well-defined boundaries, and those boundaries might have certain kinds of curves, and there may possibly even be well-defined holes in the blob, at least if you “fatten up” the points (sufficiently but not more than necessary) and then take the union of all of the resulting spheres to be some kind of 3-d manifold. You can then play with the relationship between, say, the radius of these fattened points and the topological properties of the resulting blob.

Anyhoo, the idea could be that, if you see x1 and x2 then you can exclude a y that lives in a hole, or rather where point (x1, x2, y) would live in a hole. This is more than most kinds of modern models can do for you, but even so I’ve never seen this actually come in handy.

I hope that helps, and please do see a doctor!

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

This is a reaction to a previous post (maybe Oct 12?) where you said the following:

My kids, to be clear, hate team sports and suck at them, like good nerds.

Now, as a nerd whose parents never let play team sports growing up and now plays one in college (a “nerd” sport, but still…), I have a question for you: Why do “good nerds” have to hate sports and/or suck at them? What classifies a “good nerd”? Does this generalize to other things that nerds are stereotypically bad at, like sex lives? Is there another category that should be created for nerdy type people that are also jocky-er, like a nerock or a jord?

With Love,

A “Bad Nerd”

Dear Bad Nerd,

Great question, and you’re not the only nerd that called me out on my outrageous discrimination. I wasn’t being fair to my nerock and jord friends, and that ‘aint cool. Although, statistically I believe I still have a point, there’s no reason to limit people in arbitrary ways like that, and it’s fundamentally un-nerdy of me to do so.

For all you nerocks and jords out there: you go, girls! and boys!

But just for the record, nerds are categorically excellent at sex. We all know that. Say yes.

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Alan Greenspan still doesn’t get it. #OWS

Yesterday I read Alan Greenspan’s recent article in Foreign Affairs magazine (hat tip Rhoda Schermer). It is entitled “Never Saw It Coming: Why the Financial Crisis Took Economists By Surprise,” and for those of you who want to save some time, it basically goes like this:

I’ll admit it, the macroeconomic models that we used before the crisis failed, because we assumed people financial firms behaved rationally. But now there are new models that assume predictable irrational behavior, and once we add those bells and whistles onto our existing models, we’ll be all good. Y’all can start trusting economists again.

Here’s the thing that drives me nuts about Greenspan. He is still talking about financial firms as if they are single people. He just didn’t really read Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, or at least didn’t understand it, because if he had, he’d have seen that Adam Smith argued against large firms in which the agendas of the individuals ran counter to the agenda of the company they worked for.

If you think about individuals inside the banks, in other words, then their individual incentives explain their behavior pretty damn well. But Greenspan ignores that and still insists on looking at the bank as a whole. Here’s a quote from the piece:

Financial firms accepted the risk that they would be unable to anticipate the onset of a crisis in time to retrench. However, they thought the risk was limited, believing that even if a crisis developed, the seemingly insatiable demand for exotic financial products would dissipate only slowly, allowing them to sell almost all their portfolios without loss. They were mistaken.

Let’s be clear. Financial firms were not “mistaken”, because legal contracts can’t think. As for the individuals working inside those firms, there was no such assumption about a slow exhale. Everyone was furiously getting their bonuses pumped up while the getting was good. People on the inside knew the market for exotic financial products would blow at some point, and that their personal risks were limited, so why not make systemic risk worse until then.