Archive

WTF happened to feminism?!

I usually don’t talk about feminism per se, because honestly I usually don’t think about it. Thanks to role models like my mom, who was an MIT co-ed in the ’60’s and an original nerd, helping develop the internet at Bolt Beranek and Newman and teaching computer science at UMass Boston, I’ve never for one second doubted my personal right to be a thoughtful, argumentative, and ambitious woman. I learned from my mom, and from other trailblazers, that I can pursue my personal interests and trust that the world will welcome my contributions.

Two events in the past week have made me think about how confusing this message has become for today’s growing girls, however.

First, the Sheryl Sandberg thing. To be honest, I haven’t read the book. But I have read this Washington Post article describing the book, and here’s my take on it: a corporate branding campaign loosely tied to women, but mostly pushing forward the agenda of how to be a company drone. From the article:

Sandberg’s understanding of leadership so perfectly internalizes the power structures of institutions created and dominated by men that it cannot conceive of women’s leadership outside of those narrow spaces. Does this also explain why, for Sandberg, the biggest threat to our ability to occupy a position of leadership is a woman’s desire to have a child? This is what men have been telling us for years.

Sandberg may miss so many women in her movement simply because her brand of gender equity is almost entirely privatized, doled out from employer to employee. Women, she advises, will find their way to the top through telling employers upfront about their childbearing plans, through learning how to negotiate pay raises (say “we” instead of “I,” Sandberg cautions, though the collective here is the corporation), through comportment exercises, as taught through Lean In’s web videos.

Like I said in this post, wouldn’t an actual feminist agenda include saying “The hell with this!” to a corporation that is so stifling that all our imaginations could bring us is better maternity leave negotiation tactics with the Borg? Resistance is futile, man!

Here’s the second thing that pissed me off this week. Harvard MBA Rachel Greenwald tells women what makes men not call back after a date.

Answer? As it turns out, anything where you have an opinion and they feel intimidated by you. Solution? Dumb it down, sex it up, and act like a toy. That way, in her words, you’ll be empowered, because they’re all calling you back, and the choice is yours. The choice, I’d add, from a long list of wimps. No thank you.

The video:

Can we do better than this, people??

Is mathematics a vehicle for control fraud?

Bill Black

A couple of nights I ago I attended this event at Columbia on the topic of “Rent-Seeking, Instability and Fraud: Challenges for Financial Reform”.

The event was great, albeit depressing – I particularly loved Bill Black‘s concept of control fraud, which I’ll talk more about in a moment, as well as Lynn Turner‘s polite description of the devastation caused by the financial crisis.

To be honest, our conclusion wasn’t a surprise: there is a lack of political will in Congress or elsewhere to fix the problems, even the low-hanging obvious criminal frauds. There aren’t enough actual police to take on the job of dealing with the number of criminals that currently hide in the system (I believe the statistic was that there are about 1,000,000 people in law enforcement in this country, and 2,500 are devoted to white-collar crime), and the people at the top of the regulatory agencies have been carefully chosen to not actually do anything (or let their underlings do anything).

Even so, it was interesting to hear about this stuff through the eyes of a criminologist who has been around the block (Black was the guy who put away a bunch of fraudulent bankers after the S&L crisis) and knows a thing or two about prosecuting crimes. He talked about the concept of control fraud, and how pervasive control fraud is in the current financial system.

Control Fraud

Control fraud, as I understood him to describe it, is the process by which a seemingly legitimate institution or process is corrupted by a fraudulent institution to maintain the patina of legitimacy.

Once you say it that way, you recognize it everywhere, and you realize how dirty it is, since outsiders to the system can’t tell what’s going on – hey, didn’t you have overseers? Didn’t they say everything was checking out ok? What the hell happened?

So for example, financial firms like Bank of America used control fraud in the heart of the housing bubble via their ridiculous accounting methods. As one of the speakers mentioned, the accounting firm in charge of vetting BofA’s books issued the same exact accounting description for many years in the row (literally copy and paste) even as BofA was accumulating massive quantities of risky mortgage-backed securities (update: I’ve been told it’s called an “Auditors Report” and it has required language. But surely not all the words are required? Otherwise how could it be called a report?). In other words, the accounting firm had been corrupted in order to aid and abet the fraud.

“Financial Innovation”

To get an idea of the repetitive nature and near-inevitability of control fraud, read this essay by Black, which is very much along the lines of his presentation on Tuesday. My favorite passage is this, when he addresses how our regulatory system “forgot about” control fraud during the deregulation boom of the 1990’s:

On January 17, 1996, OTS’ Notice of Proposed Rulemaking proposed to eliminate its rule requiring effective underwriting on the grounds that such rules were peripheral to bank safety.

“The OTS believes that regulations should be reserved for core safety and soundness requirements. Details on prudent operating practices should be relegated to guidance.

Otherwise, regulated entities can find themselves unable to respond to market innovations because they are trapped in a rigid regulatory framework developed in accordance with conditions prevailing at an earlier time.”

This passage is delusional. Underwriting is the core function of a mortgage lender. Not underwriting mortgage loans is not an “innovation” – it is a “marker” of accounting control fraud. The OTS press release dismissed the agency’s most important and useful rule as an archaic relic of a failed philosophy.

Here’s where I bring mathematics into the mix. My experience in finance, first as a quant at D.E. Shaw, and then as a quantitative risk modeler at Riskmetrics, convinced me that mathematics itself is a vehicle for control fraud, albeit in two totally different ways.

Complexity

In the context of hedge funds and/or hard-core trading algorithms, here’s how it works. New-fangled complex derivatives, starting with credit default swaps and moving on to CDO’s, MBS’s, and CDO+’s, got fronted as “innovation” by a bunch of economists who didn’t really know how markets work but worked at fancy places and claimed to have mathematical models which proved their point. They pushed for deregulation based on the theory that the derivatives represented “a better way to spread risk.”

Then the Ph.D.’s who were clever enough to understand how to actually price these instruments swooped in and made asstons of money. Those are the hedge funds, which I see as kind of amoral scavengers on the financial system.

At the same time, wanting a piece of the action, academics invented associated useless but impressive mathematical theories which culminated in mathematics classes throughout the country that teach “theory of finance”. These classes, which seemed scientific, and the associated economists described above, formed the “legitimacy” of this particular control fraud: it’s math, you wouldn’t understand it. But don’t you trust math? You do? Then allow us to move on with rocking our particular corner of the financial world, thanks.

Risk

I also worked in quantitative risk, which as I see it is a major conduit of mathematical control fraud.

First, we have people putting forward “risk estimates” that have larger errorbars then the underlying values. In other words, if we were honest about how much we can actually anticipate price changes in mortgage backed securities in times of panic, then we’d say something like, “search me! I got nothing.” However, as we know, it’s hard to say “I don’t know” and it’s even harder to accept that answer when there’s money on the line. And I don’t apologize for caring about “times of panic” because, after all, that’s why we care about risk in the first place. It’s easy to predict risk in quiet times, I don’t give anyone credit for that.

Never mind errorbars, though- the truth is, I saw worse than ignorance in my time in risk. What I actually saw was a rubberstamping of “third part risk assessment” reports. I saw the risk industry for what it is, namely a poor beggar at the feet of their macho big-boys-of-finance clients. It wasn’t just my firm either. I’ve recently heard of clients bullying their third party risk companies into allowing them to replace whatever their risk numbers were by their own. And that’s even assuming that they care what the risk reports say.

Conclusion

Overall, I’m thinking this time is a bit different, but only in the details, not in the process. We’ve had control fraud for a long long time, but now we have an added tool in the arsenal in the form of mathematics (and complexity). And I realize it’s not a standard example, because I’m claiming that the institution that perpetuated this particular control fraud wasn’t a specific institution like Bank of America, but rather then entire financial system. So far it’s just an idea I’m playing with, what do you think?

Break up the megabanks already (#OWS)

For the past few months at Occupy we’ve been focusing more and more on having a single message and goal. That has been to break up the big banks.

What’s great about this goal is that it’s a non-partisan issue; there is growing consensus (among non-bankers) from the left and the right that the current situation is outrageous and untenable. What’s not great, of course, is that the situation is so easy to spot because it’s so heinous.

Yesterday another voice joined the Break-Up-The-Big-Banks chorus in the form of an editorial at Bloomberg (hat tip Hannah Appel). They wrote a persuasive piece on breaking up the big banks based on simple arithmetic involving bank profits and taxpayer subsidy. Even the title fits that description: “Why Should Taxpayers Give Big Banks $83 Billion a Year?”. Here’s an excerpt from the editorial (emphasis mine):

…Banks have a powerful incentive to get big and unwieldy. The larger they are, the more disastrous their failure would be and the more certain they can be of a government bailout in an emergency. The result is an implicit subsidy: The banks that are potentially the most dangerous can borrow at lower rates, because creditors perceive them as too big to fail.

Lately, economists have tried to pin down exactly how much the subsidy lowers big banks’ borrowing costs. In one relatively thorough effort, two researchers — Kenichi Ueda of the International Monetary Fund and Beatrice Weder di Mauro of the University of Mainz — put the number at about 0.8 percentage point. The discount applies to all their liabilities, including bonds and customer deposits.

Big Difference

Small as it might sound, 0.8 percentage point makes a big difference. Multiplied by the total liabilities of the 10 largest U.S. banks by assets, it amounts to a taxpayer subsidy of $83 billion a year. To put the figure in perspective, it’s tantamount to the government giving the banks about 3 cents of every tax dollar collected.

The top five banks — JPMorgan, Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc., Wells Fargo & Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. – – account for $64 billion of the total subsidy, an amount roughly equal to their typical annual profits (see tables for data on individual banks). In other words, the banks occupying the commanding heights of the U.S. financial industry — with almost $9 trillion in assets, more than half the size of the U.S. economy — would just about break even in the absence of corporate welfare. In large part, the profits they report are essentially transfers from taxpayers to their shareholders.

Next time someone tells me I want to take money out of rich people’s pockets (and that makes me a free market hater), I’m going to remind them that every time I pay taxes, 3 cents out of every dollar (that I know of) goes directly to the banks for no good reason whatsoever except the fact that they have the lobbyists to support this system. They’re bullies, and I hate bullies.

So no, I’m not suggesting we take honestly earned money out of the pockets of those who deserve it, I’m suggesting we stop stuffing insiders’ pockets with our money. Big difference.

But it’s not just money I object to – it’s future liability. There’s now an established track record of discovered criminal acts that don’t get anyone at the big banks in trouble. We are setting ourselves up for an even bigger bailout of some form soon, one that we taxpayers really may not be able to afford.

I think of the too-big-to-fail problem as like having an alcoholic brother-in-law who not only sleeps on your couch every night but also knows the PIN code on your ATM card. The money is irksome, no doubt, but what if that guy fell asleep smoking a cigarette and me and my kids die in the resulting fiery inferno? And it’s not that I think all addicts could be magically cured, but I don’t want them to have access to my personal stuff. Get them out of my house.

So can we break up the megabanks already? I’d really like to stop worrying about them because I have better things to do.

Five false myths that make liberals feel good

1. The U.S. has a progressive tax code

Actually, no. Not when you include all kinds of taxes. From this Economist column, which states “The fact of the matter is that the American tax code as a whole is almost perfectly flat.”

2. The U.S. is a land of opportunity

Actually, the mobility of the U.S. is worse than Canada’s or anywhere in Western Europe. From the NY Times article:

Despite frequent references to the United States as a classless society, about 62 percent of Americans (male and female) raised in the top fifth of incomes stay in the top two-fifths, according to research by the Economic Mobility Project of the Pew Charitable Trusts. Similarly, 65 percent born in the bottom fifth stay in the bottom two-fifths.

3. The bailout worked

Actually, the bailout is still happening, as we see from monthly discoveries such as this recent back-door bailout, and it hasn’t worked for the majority of the people it was intended for, namely people stuck with unreasonable mortgages (people forget this sometimes, but the first half of TARP was for the banks, the second half was for mortgage holders). From a NY Times Op-ed by Elizabeth Lynch (emphasis mine):

So a lender can forgive a second mortgage — which in the event of foreclosure would be worthless anyway — and under the settlement claim credits for “modifying” the mortgage, while at the same time it or another bank forecloses on the first loan. The upshot, of course, is that the people the settlement was designed to protect keep losing their homes.

4. Our private data is protected by our government

Although on the one hand the CIA recently admitted to full monitoring of Facebook using fake personas (h/t Chris Wiggins), the U.S. government does not in fact take great pains to protect the data they collect about its citizens. Moreover, government workers who complain about the porous data protection are punished instead of protected, as is explained in this Times piece. My favorite quote is this bit of common sense:

Susan Landau, a Guggenheim fellow in cyber security, privacy and public policy, says companies and agencies are unlikely to improve data security without the threat of penalty.

“What are the personal consequences for employees who allow data breaches to happen?” Ms. Landau asks. “Until people lose their jobs, nothing is going to change.”

5. We are recovering from the great recession

From 2009-2011, the top 1% captured 121% of all income gains (h/t Matt Stoller).

Who says you can’t perform at 121%? Turns out you can if other people are actually losing income while you’re getting increasingly rich.

Don’t get me wrong, corporate profits have done even better – a 171% gains since we’ve had Obama. But I’d go by things that matter to the 99%, so payrolls and jobs. Payrolls are flat and we still have 5 million fewer jobs, so I’d say it’s not much of a recovery.

The smell test for big data

The other day I was chatting with a data scientist (who didn’t know me), and I asked him what he does. He said that he used social media graphs to see how we might influence people to lose weight.

Whaaaa? That doesn’t pass the smell test.

If I can imagine it happening in real life, between people, then I can imagine it happening in a social medium. If it doesn’t happen in real life, it doesn’t magically appear on the internet.

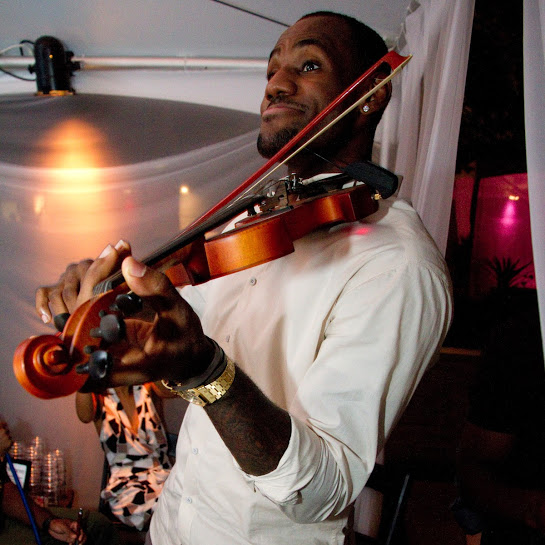

So if I have a huge crush on LeBron James (true), and if he tweets that I should go out and watch “Life of Pi” because it’s a great movie (true), then I’d do it, because I’d imagine he is here with me in my living room suggesting that I see that movie, and I’d do anything that man says if he’s in my living room, especially if he’s jamming with me.

But if LeBron James tells me to lose weight while we’re hanging, then I just feel bad and weird. Because nobody can influence someone else to lose weight in person*.

Bottomline: there’s a smell test, and it states that real influence happening inside a social graph isn’t magical just because it’s mathematically formulated. It is at best an echo of the actual influence exerted in real life. I have yet to see a counter-example to that. If you have one, please challenge me on this.

Any data scientist going around claiming they’re going to surpass this smell test should stop right now, because it adds to the hype and adds to the noise around big data without adding to the conversation.

* I’ll make an exception if they’re a doctor wielding a surgical knife about to remove my stomach or something, which doesn’t translate well into social media, and might not always work long-term. And to be fair, you (or LeBron) can influence me to not eat a given thing on a given day, or even to go on a diet, but by now we should know that doesn’t have long term effects. There’s a reason Weight Watchers either doesn’t publish their results or relies on survivorship bias for fake results.

Occupy HSBC: Valentine’s Day protest at noon #OWS

Protest with #OWS Alternative Banking Group

I’m writing to invite you to a protest against mega-bank HSBC at noon on Valentine’s Day (Thursday) starting on the steps of the New York Public Library at 42nd and 5th. Details are here but it’s the big green box on the map on the Fifth Avenue side:

Why are we protesting?

Like you, I’m sure, I’d like nothing more than to stop worrying about shit that goes on in our country’s banks.

We have better things to do with out time than to get annoyed over enormous bonuses being given to idiots for their repeated failures. We’re frankly exhausted from the outrage.

I mean, the average person doesn’t have a job where they get an $11 million bonus instead of a $22 million dollar bonus when they royally screw up. Outside the surreal realm of international banking, the normal response to screw-ups on that level is to get fired.

You might expect a company that has been caught criminally screwing minorities out of fair contracts might be at risk of being closed down, but in this day and age you’d know that big banks, or TIBACO (too interconnected, big, and complex to oversee) institutions, as we in Alt Banking like to call them, are immune to such action.

There’s a clear evolving standard of treatment in the banking sector when it comes to criminal activity:

- the powers that be (SEC, DOJ, etc.) make a huge production over the severity of the fine,

- which is large in dollar amounts but

- usually represents about 10% of the overall profit the given banks made during their exploit.

- Nobody ever goes to jail, and

- the shareholders pay the fine, not the perpetrators.

- The perps get somewhat diminished bonuses. At worst.

The bottomline: we have an entire class of citizens that are immune to the laws because they are considered too important to our financial stability.

But why HSBC?

HSBC is a perfect example of this. An outrageous example.

HSBC didn’t get a bailout in 2008 like many other banks, even though they were ranked #2 in subprime mortgage lending. But that’s not because they didn’t lose money – in fact they lost $6 billion but somehow kept afloat.

And now we know why.

Namely, they were money-laundering, earning asstons by facilitating drugs and terrorism. This was blood money, make no mistake, and it went directly into the pockets of HSBC bankers in the form of bonuses.

When this years-long criminal mafia activity was discovered, nothing much happened beyond a fine, as per usual. Well, to be honest, they were fined $1.9 billion dollars, which is a lot of money, but is only 5 weeks of earnings for the mammoth institution – depending on the way you look at it, HSBC is the 2nd largest bank in the world.

Too big to jail

And that’s when “Too big to fail” became “Too big to jail.” Even the New York Times was outraged. From their editorial page:

Federal and state authorities have chosen not to indict HSBC, the London-based bank, on charges of vast and prolonged money laundering, for fear that criminal prosecution would topple the bank and, in the process, endanger the financial system. They also have not charged any top HSBC banker in the case, though it boggles the mind that a bank could launder money as HSBC did without anyone in a position of authority making culpable decisions.

Clearly, the government has bought into the notion that too big to fail is too big to jail. When prosecutors choose not to prosecute to the full extent of the law in a case as egregious as this, the law itself is diminished. The deterrence that comes from the threat of criminal prosecution is weakened, if not lost.

National Threat

You may recall that there was an extensive FBI investigation of OWS before Zuccotti Park was even occupied.

Ironic? As the Village Voice said, “apparently non-violent demonstration against corrupt banking is subject to more criminal scrutiny than actual corrupt banking.”

Question for you: which is the bigger national security threat, OWS or HSBC?

We demand

HSBC needs its license revoked, and there need to be prosecutions. Those who are guilty need to be punished or else we have an official invitation to criminal acts by bankers. We simply can’t live in a country which rewards this kind of behavior.

Mind you, this isn’t just about HSBC. This is about all the megabanks. Citi or BoA are exempt from prosecution, too. Our message needs to be “break up the megabanks”.

I’ll end with what Matt Taibbi had to say about the HSBC settlement:

On the other hand, if you are an important person, and you work for a big international bank, you won’t be prosecuted even if you launder nine billion dollars. Even if you actively collude with the people at the very top of the international narcotics trade, your punishment will be far smaller than that of the person at the very bottom of the world drug pyramid. You will be treated with more deference and sympathy than a junkie passing out on a subway car in Manhattan (using two seats of a subway car is a common prosecutable offense in this city). An international drug trafficker is a criminal and usually a murderer; the drug addict walking the street is one of his victims. But thanks to Breuer, we’re now in the business, officially, of jailing the victims and enabling the criminals.

Join us on Valentine’s Day at noon on the steps of the New York Public Library and help us Occupy HSBC. Please redistribute widely!

Gender bias in math

I don’t agree with everything she always says, but I agree with everything Izabella Laba says in this post called Gender Bias 101 For Mathematicians (hat tip Jordan Ellenberg). And I’m kind of jealous she put it together in such a fantastic no-bullshit way.

Namely, she debunks a bunch of myths of gender bias. Here’s my summary, but you should read the whole thing:

- Myth: Sexism in math is perpetrated mainly by a bunch of enormously sexist old guys. Izabella: Nope, it’s everyone, and there’s lots of evidence for that.

- Myth: The way to combat sexism is to find those guys and isolate them. Izabella: Nope, that won’t work, since it’s everyone.

- Myth: If it’s really everyone, it’s too hard to solve. Izabella: Not necessarily, and hey you are still trying to solve the Riemann Hypothesis even though that’s hard (my favorite argument).

- Myth: We should continue to debate about its existence rather than solution. Izabella: We are beyond that, it’s a waste of time, and I’m not going to waste my time anymore.

- Myth: Izabella, you are only writing this to be reassured. Izabella: Don’t patronize me.

Here’s what I’d add. I’ve been arguing for a long time that gender bias against girls in math starts young and starts at the cultural level. It has to do with expectations of oneself just as much as a bunch of nasty old men (by the way, the above is not to say there aren’t nasty old men (and nasty old women!), just that it’s not only about them).

My argument has been that the cultural differences are larger than the talent differences, something Larry Summers strangely dismissed without actually investigating in his famous speech.

And I think I’ve found the smoking gun for my side of this argument, in the form of an interactive New York Times graphic from last week’s Science section which I’ve screenshot here:

What this shows is that 15-year-old girls out-perform 15-year-old boys in certain countries and under-perform them in others. Those countries where they outperform boys is not random and has everything to do with cultural expectations and opportunities for girls in those countries and is explained to some extent by stereotype threat. Go read the article, it’s fascinating.

I’ll say again what I said already at the end of this post: the great news is that it is possible to address stereotype threat directly, which won’t solve everything but will go a long way.

You do it by emphasizing that mathematical talent is not inherent, nor fixed at birth, and that you can cultivate it and grow it over time and through hard work. I make this speech whenever I can to young people. Spread the word!

It’s not that I don’t understand you, it’s that you’re wrong

Dear …..,

I’ve been meaning to explain this to you. It took me a while to get what was happening in our interactions, so it’s only fair for me to explain it to you now that I get it.

Namely, every time we meet, you try to explain the same thing to me, even though I already understood it the first time – maybe even before meeting you.

You see, it’s not that I don’t understand you, it’s that you’re wrong.

You obviously think that anybody who doesn’t agree with you must not understand you (because what you actually think is that anyone who understands your impeccable logic must agree with you), but take it from me, I don’t agree with you. At all. And I’m not interested in you explaining your logic to me again. Next time you try to do that, I will stop you.

Mind you, I don’t have huge hope for this plan, because I’ve tried it before. I spent one conversation with you very carefully giving you supporting evidence that I understood your points. I even did things like encouragingly rephrasing what you were saying in my own words to convince you that I understood. Then, after that, I explained to you that in spite of that clarity, your conclusions still held no sway with me. None whatsoever! They were based on naive and obvious simplifications! We might as well agree to disagree!

And yet… yet you seemed to have forgotten that episode entirely by the time we next met.

So, actually, here’s what’s gonna happen, next time we meet. I’m going to avoid you, and if that doesn’t work, I’ll avoid talking to you, and if that is impossible, I will nod and smile. I don’t want to have to resort to nastiness, and although I believe in being direct and I’m no conflict avoider, there are certain conflicts one can’t resolve, and one of them is you.

Thanks,

Cathy

Bad model + high stakes = gaming

Today let’s talk some oldish news about Michelle Rhee, the Chancellor of Washington public schools from 2007-2010, who recently appeared on the Daily Show.

Specifically I want to discuss a New York Times article from 2011 (hat tip Suresh Naidu) that is entitled “Eager for Spotlight, but Not if It Is on a Testing Scandal”.

When she was Chancellor, Rhee was a huge backer of the standardized testing approach to locating “bad teachers”. She did obnoxious stuff like carry around a broom to illustrate her “cleaning out the trash” approach. She fired a principal on camera.

She also enjoyed taking credit when scores went up, and the system rewarded those teachers with bonuses. So it was very high stakes: you get a cash incentive to improve your students’ scores and the threat of a broom if they go down.

And guess what, there was good evidence of cheating. If you want to read more details, read the article, then read this and this: short version is that a pseudo-investigation came up with nothing (surprise!) but then again scores went way down when they changed leadership and added security.

My point isn’t that we should put security in every school, though. My point is that when you implement a model which is both gameable and high stakes, you should expect it to be gamed. Don’t be surprised by that, and don’t give yourself credit that everyone is suddenly perfect by your measurement in the meantime.

Another way of saying it is that if you go around trusting the numbers, you have to be ready to trust the evidence of gaming too. You can’t have it both ways. We taxpayers should remember that next time we give the banks gameable stress tests or when we discover off-shore tax shelters by corporations.

Bill Gates is naive, data is not objective

In his recent essay in the Wall Street Journal, Bill Gates proposed to “fix the world’s biggest problems” through “good measurement and a commitment to follow the data.” Sounds great!

Unfortunately it’s not so simple.

Gates describes a positive feedback loop when good data is collected and acted on. It’s hard to argue against this: given perfect data-collection procedures with relevant data, specific models do tend to improve, according to their chosen metrics of success. In fact this is almost tautological.

As I’ll explain, however, rather than focusing on how individual models improve with more data, we need to worry more about which models and which data have been chosen in the first place, why that process is successful when it is, and – most importantly – who gets to decide what data is collected and what models are trained.

Take Gates’s example of Ethiopia’s commitment to health care for its people. Let’s face it, it’s not new information that we should ensure “each home has access to a bed net to protect the family from malaria, a pit toilet, first-aid training and other basic health and safety practices.” What’s new is the political decision to do something about it. In other words, where Gates credits the measurement and data-collection for this, I’d suggest we give credit to the political system that allowed both the data collection and the actual resources to make it happen.

Gates also brings up the campaign to eradicate polio and how measurement has helped so much there as well. Here he sidesteps an enormous amount of politics and debate about how that campaign has been fought and, more importantly, how many scarce resources have been put towards it. But he has framed this fight himself, and has collected the data and defined the success metric, so that’s what he’s focused on.

Then he talks about teacher scoring and how great it would be to do that well. Teachers might not agree, and I’d argue they are correct to be wary about scoring systems, especially if they’ve experienced the random number generator called the Value Added Model. Many of the teacher strikes and failed negotiations are being caused by this system where, again, the people who own the model have the power.

Then he talks about college rankings and suggests we replace the flawed US News & World Reports system with his own idea, namely “measures of which colleges were best preparing their graduates for the job market”. Note I’m not arguing for keeping that US News & World Reports model, which is embarrassingly flawed and is consistently gamed. But the question is, who gets to choose the replacement?

This is where we get the closest to seeing him admit what’s really going on: that the person who defines the model defines success, and by obscuring this power behind a data collection process and incrementally improved model results, it seems somehow sanitized and objective when it’s not.

Let’s see some more example of data collection and model design not being objective:

- We see that cars are safer for men than women because the crash-test dummies are men.

- We see that cars are safer for thin people because the crash-test dummies are thin.

- We see drugs are safer and more effective for white people because blacks are underrepresented in clinical trials (which is a whole other story about power and data collection in itself).

- We see that Polaroid film used to only pick up white skin because it was optimized for white people.

- We see that poor people are uninformed by definition of how we take opinion polls (read the fine print).

Bill Gates seems genuinely interested in tackling some big problems in the world, and I wish more people thought long and hard about how they could contribute like that. But the process he describes so lovingly is in fact highly fraught and dangerous.

Don’t be fooled by the mathematical imprimatur: behind every model and every data set is a political process that chose that data and built that model and defined success for that model.

The senseless war between business and IT/data

Last night I attended a NYC Data Business Meetup at Bloomberg, organized by Matt Turck of Bloomberg Ventures.

There were four startups talking about their analytics-for-big-data products. Most of the audience was on the entrepreneurial side of big data, and not themselves data scientists. Of the people on stage, there were four entrepreneur/marketing people and one data scientist.

I noticed, during the Q&A part at the end, that there was a weird vibe in relation to IT/data teams versus business teams. Not everyone present was involved, to be clear, but rather a consistent thread of the conversation.

There was a conflict, we were told, between business and data, and the goal of these analytics platforms seemed to be, to a large extent, a way of bypassing the need for letting data people own the data. The idea was to expedite the “handoff” between the data/IT people and the business people, so that the business people could do rapid, iterative data investigations (without interference, presumably, from pesky data people).

The discussion even went so far as to describe the IT/data team as “territorial” with the data, and there was a short discussion as to how to create processes so that control of the data is clearly spelled out and is in the hands of the business, rather than the data people.

All this left we wondering if I am crazy to believe that, as a data scientist, I am also a business person.

Are we in a war that I didn’t know about? Is it a war between the business side and the data side of the business? And are these analytics platforms the space on which the war is waged? Are they either going to make data people obsolete, by making it unnecessary to hire data scientists, or are they going to make business analytics people obsolete, by allowing data scientists to quickly iterate models?

Are there really such lines drawn, and are they necessary?

Personally, I didn’t leave research in academia so that I could be an mere implementer of a “business person”‘s idea. I left so that I could be part of the decision-making process in an agile business, so that I can be part of the process that figures out what questions to ask, and moreover how to answer them, using my quantitative background.

I don’t think this war is a good idea – instead, we should strive toward creating a scenario in which data scientists and domain experts work together towards forming the question and investigating a solution.

To silo a data person is to undervalue them – indeed my best guess as to why some business people see data people as belligerent is that they’ve been undervaluing their data people, and that tends to make people belligerent.

And to give a business analyst a button on a screen which says “clustering algorithm” is to give them tools they can perhaps use but very probably can’t interpret. It’s in nobody’s interest to do this, and it’s certainly not in the interest of the ambient business.

From now on, if someone asks me if they should accept an offer as a data scientist, I’ll suggest they find out if the place is engaged in an “IT/data versus business” war, and if they are, to run away quickly. It’s a mindset that spells trouble.

The complexity feedback loop of modeling

Yesterday I was interviewed by a tech journalist about the concept of feedback loops in consumer-facing modeling. We ended up talking for a while about the death spiral of modeling, a term I coined for the tendency of certain public-facing models, like credit scoring models, to have such strong effects on people that they arguable create the future rather than forecast it. Of course this is generally presented from the perspective of the winners of this effect, but I care more about who is being forecast to fail.

Another feedback loop that we talked about was one that consumers have basically inheriting from the financial system, namely the “complexity feedback loop”.

In the example she and I discussed, which had to do with consumer-facing financial planning software, the complexity feedback loop refers to the fact that we are urged, as consumers, to keep track of our finances one way or another, including our cash flows, which leads to us worrying that we won’t be able to meet our obligations, which leads to us getting convinced we need to buy some kind of insurance (like overdraft insurance), which in turn has a bunch of complicated conditions on it.

The end result is increased complexity along with an increasing need for a complicated model to keep track of finances – in other words, a feedback loop.

Of course this sounds a lot like what happened in finance, where derivatives were invented to help disperse unwanted risk, but in turn complicated the portfolios so much that nobody understand them anymore, so we have endless discussions about how to measure the risk of the instruments that were created to remove risk.

The complexity feedback loop is generalizable outside of the realm of money as well.

In general models take certain things into account and ignore others, by their nature; models are simplified versions of the world, especially when they involve human behavior. So certain risks, or effects, are sufficiently small that the original model simply doesn’t see them – it may not even collect the data to measure it at all. Sometimes this omission is intentional, sometimes it isn’t.

But once the model is widely used, then the underlying approximation to the world is in some sense assumed, and then the remaining discrepancy is what we need to start modeling: the previously invisible becomes visible, and important. This leads to a second model tacked onto the first, or a modified version of the first. In either case it’s more complicated as it becomes more widely used.

This is not unlike saying that we’ve seen more vegetarian options on menus as restauranteurs realize they are losing out on a subpopulation of diners by ignoring their needs. From this example we can see that the complexity feedback loop can be good or bad, depending on your perspective. I think it’s something we should at least be aware of, as we increasingly interact with and depend on models.

Planning for the robot revolution

Yesterday I read this Wired magazine article about the robot revolution by Kevin Kelly called “Better than Human”. The idea of the article is to make peace with the inevitable robot revolution, and to realize that it’s already happened and that it’s good.

I like this line:

We have preconceptions about how an intelligent robot should look and act, and these can blind us to what is already happening around us. To demand that artificial intelligence be humanlike is the same flawed logic as demanding that artificial flying be birdlike, with flapping wings. Robots will think different. To see how far artificial intelligence has penetrated our lives, we need to shed the idea that they will be humanlike.

True! Let’s stop looking for a Star Trek Data-esque android (although he is very cool according to my 10-year-old during our most recent Star Trek marathon).

Instead, let’s realize that the typical artificial intelligence we can expect to experience in our lives is the web itself, inasmuch as it is a problem-solving, decision-making system, and our interactions with it through browsing and searching is both how we benefit from artificial intelligence and how it takes us over.

What I can’t accept about the Wired article, though, is the last part, where we should consider it good. But maybe it is only supposed to be good for the Wired audience and I’m asking for too much. My concerns are touched on briefly here:

When robots and automation do our most basic work, making it relatively easy for us to be fed, clothed, and sheltered, then we are free to ask, “What are humans for?”

Here’s the thing: it’s already relatively easy for us to be fed, clothed, and sheltered, but we aren’t doing it. That doesn’t seem to be our goal. So why would it suddenly become our goal because there is increasing automation? Robots won’t change our moral values, as far as I know.

Also, the article obscures economic political reality. First imagines the audience as a land- and robot-owning master:

Imagine you run a small organic farm. Your fleet of worker bots do all the weeding, pest control, and harvesting of produce, as directed by an overseer bot, embodied by a mesh of probes in the soil. One day your task might be to research which variety of heirloom tomato to plant; the next day it might be to update your custom labels. The bots perform everything else that can be measured.

Great, so the landowners will not need any workers at all. But then what about the people who don’t have a job? Oh wait, something magical happens:

Everyone will have access to a personal robot, but simply owning one will not guarantee success. Rather, success will go to those who innovate in the organization, optimization, and customization of the process of getting work done with bots and machines.

Really? Everyone will own a robot? How is that going to work? It doesn’t seem to be a natural progression from our current system. Or maybe they mean like the way people own phones now. But owning a phone doesn’t help you get work done if there’s no work for you to do.

But maybe I’m being too cynical. I’m sure there’s deep thought being put to this question. Oh here, in this part:

I ask Brooks to walk with me through a local McDonald’s and point out the jobs that his kind of robots can replace. He demurs and suggests it might be 30 years before robots will cook for us.

I guess this means we don’t have to worry at all, since 30 years is such a long, long time.

Is mathbabe a terrorist or a lazy hippy? (#OWS)

The Occupy narrative, put forth by mainstream media such as the New York Times and led by friends of Wall Street such as Andrew Ross Sorkin, is sad and pathetic. A bunch of lazy hippies, with nothing much in the way of organized demands, and, by the way, nothing much in the way of reasonable grievances either. And moreover, according to Sorkin, Occupy had fizzled as of its first anniversary.

To an earnest reader of the New York Times, in other words, there’s no there there, and we can move on. Nothing to see.

From my perspective as an active occupier, this approach of casual indifference has seemed oddly inconsistent with the interest in the #OWS Alternative Banking group from other nations. I’ve been interviewed by mainstream reporters from the UK, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, and Japan, and none of them seemed as willing to dismiss the movement or our group quite as actively as the New York Times has.

And then there was the country-wide clearing of the parks, which seemed mysteriously coordinated, and the press (yes, the New York Times again) knowing when and where it would happen somehow, and taking pictures of the police gathering beforehand.

Really it was enough to make one consider a conspiracy theory between the authorities and mainstream media.

I’m not one for conspiracy theories, though, so I let it pass. But other people were more vigilant than myself after the coordinated clearings, and, as I learned from this Naked Capitalism post, first Truthout attempted a FOIA request to the FBI, and was told that “no documents related to its infiltration of Occupy Wall Street existed at all”, and then the Partnership for Civil Justice filed a FOIA request which was served.

Turns out there was quite a bit of worry about Occupy among the FBI, and Homeland Security, even before Zuccotti was occupied. Occupy was dubbed a terrorist organization, for example. See the heavily redacted details here.

I guess to some extent this makes sense, as the roots of Occupy are outwardly anarchist, and there is a history of anarchist bombings of the New York Stock Exchange. I guess this could also explain the meetings the FBI and Homeland Security had with the banks and the stock exchange. They wanted to cover their asses in case the anarchists were violent.

On the other hand, by the time they cleared the park the movement was openly peaceful. You don’t get called lazy dirty hippies because you’re throwing bombs into buildings, after all. And the coordination of the clearing of the parks is no longer a conspiracy, it’s verified. They were clearly afraid of us.

So which is it, lazy hippy or scary terrorist? There’s a baffling disconnect.

The truth, in this case, is not in between. Instead, Occupy lives in a different plane altogether, as I’ll explain, and this in turn explains both the “lazy” and the “scary” narrative.

The “lazy” can be put to rest here and now, it’s just wrong. The response and relief efforts of Occupy Sandy has convincingly shown that laziness is not an underlying principle of Occupy.

But Occupy Sandy did expose some principles that we occupiers have known to be true since the beginning:

- that we must overcome or even ignore structured and rigid rules to help one another at a human level,

- that we must connect directly with suffering and organically respond to it as we each know how to, depending on circumstances, and

- that moral and ethical responsibilities are just plain more important than rules.

Such a nuanced concept might seem, from the outside, to be a bunch of meditating hippies, although you’d have to kind of want to see that to think that’s all it is. So that explains the “lazy” narrative to me: if you don’t understand it, and if you don’t want to bother to look carefully, then just describe the surface characteristics.

Second, the “scary” part is right, but it’s not scary in the sense of guns and bombs – but since the cops, the FBI, and Homeland Security speak in that language, the actual threat of Occupy is again lost in translation.

It’s our ideas that threaten, not our violence. We ignore the rules, when they oppress and when they make no sense and when they serve to entrench an already entrenched elite. And ignoring rules is sometimes more threatening than breaking them.

Is mathbabe a terrorist? Is the Alternative Banking group a threat to national security because we discuss breaking up the big banks without worrying about pissing off major campaign contributors?

I hope we are a threat, but not to national security, and not by bombs or guns, but by making logical and moral sense and consistently challenging a rigged system.

I’m planning to file a FOIA request on myself and on the Alt Banking group to see what’s up.

Corporations don’t act like people

Corporations may be legally protected like people, but they don’t act selfishly like people do.

I’ve written about this before here, when I was excitedly reading Liquidated by Karen Ho, but recent overheard conversations have made me realize that there’s still a feeling out there that “the banks” must not have understood how flawed the models were because otherwise they would have avoided them out of a sense of self-preservation.

Important: “the banks” don’t think or do things, people inside the banks think and do things. In fact, the people inside the banks think about themselves and their own chances of getting big bonuses/ getting fired, and they don’t think about the bank’s future at all. The exception may be the very tip top brass of management, who may or may not care about the future of their institutions just as a legacy reputation issue. But in any case their nascent reputation fears, if they existed at all, did not seem to overwhelm their near-term desire for lots of money.

Example: I saw Robert Rubin on stage well before the major problems at Citi in a discussion about how badly the mortgage-backed securities market was apt to perform in the very near future. He did not seem to be too stupid to understand what the conversation was about, but that didn’t stop him from ignoring the problem at Citigroup whilst taking in $126 million dollars. The U.S. government, in the meantime, bailed out Citigroup to the tune of $45 billion with another guarantee of $300 billion.

Here’s a Bloomberg BusinessWeek article excerpt about how he saw his role:

Rubin has said that Citigroup’s losses were the result of a financial force majeure. “I don’t feel responsible, in light of the facts as I knew them in my role,” he told the New York Times in April 2008. “Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.”

In March 2010, Rubin elaborated in testimony before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. “In the world of trading, the world I have lived in my whole adult life, there is always a very important distinction between what you could have reasonably known in light of the facts at the time and what you know with the benefit of hindsight,” he said. Pressed by FCIC Executive Director Thomas Greene about warnings he had received regarding the risk in Citigroup’s mortgage portfolio, Rubin was opaque: “There is always a tendency to overstate—or over-extrapolate—what you should have extrapolated from or inferred from various events that have yielded warnings.”

Bottomline: there’s no such thing as a bank’s desire for self-preservation. Let’s stop thinking about things that way.

Nate Silver confuses cause and effect, ends up defending corruption

Crossposted on Naked Capitalism

I just finished reading Nate Silver’s newish book, The Signal and the Noise: Why so many predictions fail – but some don’t.

The good news

First off, let me say this: I’m very happy that people are reading a book on modeling in such huge numbers – it’s currently eighth on the New York Times best seller list and it’s been on the list for nine weeks. This means people are starting to really care about modeling, both how it can help us remove biases to clarify reality and how it can institutionalize those same biases and go bad.

As a modeler myself, I am extremely concerned about how models affect the public, so the book’s success is wonderful news. The first step to get people to think critically about something is to get them to think about it at all.

Moreover, the book serves as a soft introduction to some of the issues surrounding modeling. Silver has a knack for explaining things in plain English. While he only goes so far, this is reasonable considering his audience. And he doesn’t dumb the math down.

In particular, Silver does a nice job of explaining Bayes’ Theorem. (If you don’t know what Bayes’ Theorem is, just focus on how Silver uses it in his version of Bayesian modeling: namely, as a way of adjusting your estimate of the probability of an event as you collect more information. You might think infidelity is rare, for example, but after a quick poll of your friends and a quick Google search you might have collected enough information to reexamine and revise your estimates.)

The bad news

Having said all that, I have major problems with this book and what it claims to explain. In fact, I’m angry.

It would be reasonable for Silver to tell us about his baseball models, which he does. It would be reasonable for him to tell us about political polling and how he uses weights on different polls to combine them to get a better overall poll. He does this as well. He also interviews a bunch of people who model in other fields, like meteorology and earthquake prediction, which is fine, albeit superficial.

What is not reasonable, however, is for Silver to claim to understand how the financial crisis was a result of a few inaccurate models, and how medical research need only switch from being frequentist to being Bayesian to become more accurate.

Let me give you some concrete examples from his book.

Easy first example: credit rating agencies

The ratings agencies, which famously put AAA ratings on terrible loans, and spoke among themselves as being willing to rate things that were structured by cows, did not accidentally have bad underlying models. The bankers packaging and selling these deals, which amongst themselves they called sacks of shit, did not blithely believe in their safety because of those ratings.

Rather, the entire industry crucially depended on the false models. Indeed they changed the data to conform with the models, which is to say it was an intentional combination of using flawed models and using irrelevant historical data (see points 64-69 here for more (Update: that link is now behind the paywall)).

In baseball, a team can’t create bad or misleading data to game the models of other teams in order to get an edge. But in the financial markets, parties to a model can and do.

In fact, every failed model is actually a success

Silver gives four examples what he considers to be failed models at the end of his first chapter, all related to economics and finance. But each example is actually a success (for the insiders) if you look at a slightly larger picture and understand the incentives inside the system. Here are the models:

- The housing bubble.

- The credit rating agencies selling AAA ratings on mortgage securities.

- The financial melt-down caused by high leverage in the banking sector.

- The economists’ predictions after the financial crisis of a fast recovery.

Here’s how each of these models worked out rather well for those inside the system:

- Everyone involved in the mortgage industry made a killing. Who’s going to stop the music and tell people to worry about home values? Homeowners and taxpayers made money (on paper at least) in the short term but lost in the long term, but the bankers took home bonuses that they still have.

- As we discussed, this was a system-wide tool for building a money machine.

- The financial melt-down was incidental, but the leverage was intentional. It bumped up the risk and thus, in good times, the bonuses. This is a great example of the modeling feedback loop: nobody cares about the wider consequences if they’re getting bonuses in the meantime.

- Economists are only putatively trying to predict the recovery. Actually they’re trying to affect the recovery. They get paid the big bucks, and they are granted authority and power in part to give consumers confidence, which they presumably hope will lead to a robust economy.

Cause and effect get confused

Silver confuses cause and effect. We didn’t have a financial crisis because of a bad model or a few bad models. We had bad models because of a corrupt and criminally fraudulent financial system.

That’s an important distinction, because we could fix a few bad models with a few good mathematicians, but we can’t fix the entire system so easily. There’s no math band-aid that will cure these boo-boos.

I can’t emphasize this too strongly: this is not just wrong, it’s maliciously wrong. If people believe in the math band-aid, then we won’t fix the problems in the system that so desperately need fixing.

Why does he make this mistake?

Silver has an unswerving assumption, which he repeats several times, that the only goal of a modeler is to produce an accurate model. (Actually, he made an exception for stock analysts.)

This assumption generally holds in his experience: poker, baseball, and polling are all arenas in which one’s incentive is to be as accurate as possible. But he falls prey to some of the very mistakes he warns about in his book, namely over-confidence and over-generalization. He assumes that, since he’s an expert in those arenas, he can generalize to the field of finance, where he is not an expert.

The logical result of this assumption is his definition of failure as something where the underlying mathematical model is inaccurate. But that’s not how most people would define failure, and it is dangerously naive.

Medical Research

Silver discusses both in the Introduction and in Chapter 8 to John Ioannadis’s work which reveals that most medical research is wrong. Silver explains his point of view in the following way:

I’m glad he mentions incentives here, but again he confuses cause and effect.

As I learned when I attended David Madigan’s lecture on Merck’s representation of Vioxx research to the FDA as well as his recent research on the methods in epidemiology research, the flaws in these medical models will be hard to combat, because they advance the interests of the insiders: competition among academic researchers to publish and get tenure is fierce, and there are enormous financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies.

Everyone in this system benefits from methods that allow one to claim statistically significant results, whether or not that’s valid science, and even though there are lives on the line.

In other words, it’s not that there are bad statistical approaches which lead to vastly over-reported statistically significant results and published papers (which could just as easily happen if the researchers were employing Bayesian techniques, by the way). It’s that there’s massive incentive to claim statistically significant findings, and not much push-back when that’s done erroneously, so the field never self-examines and improves their methodology. The bad models are a consequence of misaligned incentives.

I’m not accusing people in these fields of intentionally putting people’s lives on the line for the sake of their publication records. Most of the people in the field are honestly trying their best. But their intentions are kind of irrelevant.

Silver ignores politics and loves experts

Silver chooses to focus on individuals working in a tight competition and their motives and individual biases, which he understands and explains well. For him, modeling is a man versus wild type thing, working with your wits in a finite universe to win the chess game.

He spends very little time on the question of how people act inside larger systems, where a given modeler might be more interested in keeping their job or getting a big bonus than in making their model as accurate as possible.

In other words, Silver crafts an argument which ignores politics. This is Silver’s blind spot: in the real world politics often trump accuracy, and accurate mathematical models don’t matter as much as he hopes they would.

As an example of politics getting in the way, let’s go back to the culture of the credit rating agency Moody’s. William Harrington, an ex-Moody’s analyst, describes the politics of his work as follows:

In 2004 you could still talk back and stop a deal. That was gone by 2006. It became: work your tail off, and at some point management would say, ‘Time’s up, let’s convene in a committee and we’ll all vote “yes”‘.

To be fair, there have been moments in his past when Silver delves into politics directly, like this post from the beginning of Obama’s first administration, where he starts with this (emphasis mine):

To suggest that Obama or Geithner are tools of Wall Street and are looking out for something other than the country’s best interest is freaking asinine.

and he ends with:

This is neither the time nor the place for mass movements — this is the time for expert opinion. Once the experts (and I’m not one of them) have reached some kind of a consensus about what the best course of action is (and they haven’t yet), then figure out who is impeding that action for political or other disingenuous reasons and tackle them — do whatever you can to remove them from the playing field. But we’re not at that stage yet.

My conclusion: Nate Silver is a man who deeply believes in experts, even when the evidence is not good that they have aligned incentives with the public.

Distrust the experts

Call me “asinine,” but I have less faith in the experts than Nate Silver: I don’t want to trust the very people who got us into this mess, while benefitting from it, to also be in charge of cleaning it up. And, being part of the Occupy movement, I obviously think that this is the time for mass movements.

From my experience working first in finance at the hedge fund D.E. Shaw during the credit crisis and afterwards at the risk firm Riskmetrics, and my subsequent experience working in the internet advertising space (a wild west of unregulated personal information warehousing and sales) my conclusion is simple: Distrust the experts.

Why? Because you don’t know their incentives, and they can make the models (including Bayesian models) say whatever is politically useful to them. This is a manipulation of the public’s trust of mathematics, but it is the norm rather than the exception. And modelers rarely if ever consider the feedback loop and the ramifications of their predatory models on our culture.

Why do people like Nate Silver so much?

To be crystal clear: my big complaint about Silver is naivete, and to a lesser extent, authority-worship.

I’m not criticizing Silver for not understanding the financial system. Indeed one of the most crucial problems with the current system is its complexity, and as I’ve said before, most people inside finance don’t really understand it. But at the very least he should know that he is not an authority and should not act like one.

I’m also not accusing him of knowingly helping cover up the financial industry. But covering for the financial industry is an unfortunate side-effect of his naivete and presumed authority, and a very unwelcome source of noise at this moment when so much needs to be done.

I’m writing a book myself on modeling. When I began reading Silver’s book I was a bit worried that he’d already said everything I’d wanted to say. Instead, I feel like he’s written a book which has the potential to dangerously mislead people – if it hasn’t already – because of its lack of consideration of the surrounding political landscape.

Silver has gone to great lengths to make his message simple, and positive, and to make people feel smart and smug, especially Obama’s supporters.

He gets well-paid for his political consulting work and speaker appearances at hedge funds like D.E. Shaw and Jane Street, and, in order to maintain this income, it’s critical that he perfects a patina of modeling genius combined with an easily digested message for his financial and political clients.

Silver is selling a story we all want to hear, and a story we all want to be true. Unfortunately for us and for the world, it’s not.

How to push back against the celebrity-ization of data science

The truth is somewhat harder to understand, a lot less palatable, and much more important than Silver’s gloss. But when independent people like myself step up to denounce a given statement or theory, it’s not clear to the public who is the expert and who isn’t. From this vantage point, the happier, shorter message will win every time.

This raises a larger question: how can the public possibly sort through all the noise that celebrity-minded data people like Nate Silver hand to them on a silver platter? Whose job is it to push back against rubbish disguised as authoritative scientific theory?

It’s not a new question, since PR men disguising themselves as scientists have been around for decades. But I’d argue it’s a question that is increasingly urgent considering how much of our lives are becoming modeled. It would be great if substantive data scientists had a way of getting together to defend the subject against sensationalist celebrity-fueled noise.

One hope I nurture is that, with the opening of the various data science institutes such as the one at Columbia which was a announced a few months ago, there will be a way to form exactly such a committee. Can we get a little peer review here, people?

Conclusion

There’s an easy test here to determine whether to be worried. If you see someone using a model to make predictions that directly benefit them or lose them money – like a day trader, or a chess player, or someone who literally places a bet on an outcome (unless they place another hidden bet on the opposite outcome) – then you can be sure they are optimizing their model for accuracy as best they can. And in this case Silver’s advice on how to avoid one’s own biases are excellent and useful.

But if you are witnessing someone creating a model which predicts outcomes that are irrelevant to their immediate bottom-line, then you might want to look into the model yourself.

Empathy, murder, and the NRA

I’ve been having lots of dinnertime discussions with my kids about the following three news stories:

- the guy who was pushed into the subway and nobody helped him

- the Sandy Hook murders

- the Syrian uprising

When my son asked why people care so much about the kids murdered in Connecticut but not nearly as much in a random day when as many rebels are murdered by their government in Syria, I talk about how for whatever reason people have more empathy for individuals closer to them, and Connecticut is closer than Syria. It doesn’t feel good but it kind of makes sense.

But of course this doesn’t apply to the guy who was pushed off the subway.

And, speaking of the subway incident, let me be the person who stands up and says that yes, if I’d been there I would have tried to help that man get out of the subway tracks. There were 22 seconds to help him after the crazy guy fled.

For me the ethical obligations are obvious and the empathy I feel for strangers in danger is visceral. I’ve been in situations not entirely unlike this in the subway, and I saw firsthand how other people ran away and start talking about themselves rather than trying to help someone suffering, and it amazes and disgusts me.

It makes me wonder how we develop what I’ll term “working empathy”, to distinguish between someone who actually tries to help in real time and in a meaningful way when someone else is in pain versus someone who is gawking at arm’s length.

This New York Times article touches on it but doesn’t go very deep; it basically suggests we model it for children and talk about how other people feel. It also talks about how monetary rewards stifle empathy (which I knew already from working in finance).

I’m not wondering this abstractly or philosophically. I’m wondering it because if I had a good theory about creating and spreading working empathy, I’d try to join the NRA and apply the technique to see if it works on tough cases. As in, they actually try to prevent unreasonable guns in unreasonable places, not that they issue press releases.

Fighting the information war (but only on behalf of rich people)

There’s an information war out there which we have to be prepared for. Actually there a few of them.

And according to this New York Times piece, there’s now a way to fight against the machine, for a fee. Companies like Reputation.com will try to scour the web and remove data you don’t want floating around about you, and when that’s impossible they’ll flood the web with other good data to balance out the bad stuff.

At least that’s what I’m assuming they do, because they of course don’t really explain their techniques. And that’s the other information war, where they scare rich people with technical sounding jargon and tell them unlikely stories to get their money.

I’m not claiming predatory information-gatherers aren’t out there. But this is the wrong way to deal with it.

First of all, most of the data out there systematically being used for nefarious purposes, at least in this country, is used against the poor, denying them reasonable terms on their loans and other services. So the idea that people will need to pay for a service to protect their information is weird. It’s like saying the air quality is bad for poor people, so let’s charge rich people for better air.

So what kind of help is Reputation.com actually providing? Here’s my best guess.

First it targets people to get overly scared in the spirit of this recent BusinessWeek article, which explains that cosmetic companies have gone to China and started a campaign to convince Chinese women they are too hairy so they’ll start buying products to remove hair. From that article, which is guaranteed to make you understand something about American beauty culture too:

Despite such plays on women’s fears of embarrassment, Reckitt Benckiser’s Sehgal says that Chinese women are too “independent-minded” to be coaxed into using a product they don’t really need. Others aren’t so sure. Veet’s Chinese marketing “plays a role that is very similar to that of the apple in the Bible,” says Benjamin Voyer, a social psychologist and assistant professor of marketing at ESCP Europe business school. “It creates an awareness, which subsequently creates a feeling of shame and need.”

Second, Reputation.com gets their clients off nuisance lists, like the modern version of a do-not-call program (which, importantly, is run by the government). This is probably equivalent to setting up a bunch of email filters and clearing their cookies every now and then, but they can’t tell their clients that.

Finally, for those rich people who are also super vain, they will try to do things like replace the unflattering photos of them that come up in a google image search with better-looking ones they choose. Things like that, image issues.

I just want to point out one more salient fact about Reputation.com. It’s not just in their interest to scare-monger, it’s actually in their interest to make the data warehouses more complete (they have themselves amassed an enormous database on people), and to have people who don’t pay for their services actually need their services more. They could well create a problem to produce a market for their product.

What drives me nuts about this is how elitist it is.

There are very real problems in the information-gathering space, and we need to address them, but one of the most important issues is that the very people who can’t afford to pay for their reputation to be kept clean are the real victims of the system.

There is literally nobody who will make good money off of actually solving this problem: I challenge any libertarian to explain how the free market will address this. It has to be addressed through policy, and specifically through legislating what can and cannot be done with personal data.

Probably the worst part is that, through using the services from companies Reputation.com and because of the nature of the personalization of internet usage, the very legislators who need to act on behalf of their most vulnerable citizens won’t even see the problem since they don’t share it.

Can we put an ass-kicking skeptic in charge of the SEC?

The SEC has proven its dysfunctionality. Instead of being on top of the banks for misconduct, it consistently sets the price for it at below cost. Instead of examining suspicious records to root out Ponzi schemes, it ignores whistleblowers.

I think it’s time to shake up management over there. We need a loudmouth skeptic who is smart enough to sort through the bullshit, brave enough to stand up to bullies, and has a strong enough ego not to get distracted by threats about their future job security.

My personal favorite choice is Neil Barofsky, author of Bailout (which I blogged about here) and former Special Inspector General of TARP. Simon Johnson, Economist at MIT, agrees with me. From Johnson’s New York Times Economix blog:

… Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector general in charge of oversight for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. A career prosecutor, Mr. Barofsky tangled with the Treasury officials in charge of handing out support for big banks while failing to hold the same banks accountable — for example, in their treatment of homeowners. He confronted these powerful interests and their political allies repeatedly and on all the relevant details – both behind closed doors and in his compelling account, published this summer: “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.”

His book describes in detail a frustration with the timidity and lack of sophistication in law enforcement’s approach to complex frauds. He could instantly remedy that if appointed — Mr. Barofsky is more than capable of standing up to Wall Street in an appropriate manner. He has enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the past and could be confirmed by the Senate (just as he was previously confirmed to his TARP position).

Barofsky isn’t the only person who would kick some ass as the head of the SEC – William Cohan thinks Eliot Spitzer would make a fine choice, and I agree. From his Bloomberg column (h/t Matt Stoller):

The idea that only one of Wall Street’s own can regulate Wall Street is deeply disturbing. If Obama keeps Walter on or appoints Khuzami or Ketchum, we would be better off blowing up the SEC and starting over.

I still believe the best person to lead the SEC at this moment remains former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer. He would fearlessly hold Wall Street accountable for its past sins, as he did when he was New York State attorney general and as he now does as a cable television host. (Disclosure: I am an occasional guest on his show.)

We need an SEC head who can inspire a new generation of investors to believe the capital markets are no longer rigged and that Wall Street cannot just capture every one of its Washington regulators.

How to evaluate a black box financial system

I’ve been blogging about evaluation methods for modeling, for example here and here, as part of the book I’m writing with Rachel Schutt based on her Columbia Data Science class this semester.

Evaluation methods are important abstractions that allow us to measure models based only on their output.

Using various metrics of success, we can contrast and compare two or more entirely different models. And it means we don’t care about their underlying structure – they could be based on neural nets, logistic regression, or decision trees, but for the sake of measuring the accuracy, or the ranking, or the calibration, the evaluation method just treats them like black boxes.

It recently occurred to me a that we could generalize this a bit, to systems rather than models. So if we wanted to evaluate the school system, or the political system, or the financial system, we could ignore the underlying details of how they are structured and just look at the output. To be reasonable we have to compare two systems that are both viable; it doesn’t make sense to talk about a current, flawed system relative to perfection, since of course every version of reality looks crappy compared to an ideal.

The devil is in the articulated evaluation metric, of course. So for the school system, we can ask various questions: Do our students know how to read? Do they finish high school? Do they know how to formulate an argument? Have they lost interest in learning? Are they civic-minded citizens? Do they compare well to other students on standardized tests? How expensive is the system?

For the financial system, we might ask things like: Does the average person feel like their money is safe? Does the system add to stability in the larger economy? Does the financial system mitigate risk to the larger economy? Does it put capital resources in the right places? Do fraudulent players inside the system get punished? Are the laws transparent and easy to follow?

The answers to those questions aren’t looking good at all: for example, take note of the recent Congressional report that blames Jon Corzine for MF Global’s collapse, pins him down on illegal and fraudulent activity, and then does absolutely nothing about it. To conserve space I will only use this example but there are hundreds more like this from the last few years.