Archive

If we bailed out the banks, why not Detroit? (#OWS)

I wrote a post yesterday to discuss the fact that, as we’ve seen in Detroit and as we’ll soon see across the country, the math isn’t working out on pensions. One of my commenters responded, saying I was falling for a “very right wing attack on defined benefit pensions.”

I think it’s a mistake to think like that. If people on the left refuse to discuss reality, then who owns reality? And moreover, who will act and towards what end?

Here’s what I anticipate: just as “bankruptcy” in the realm of airlines has come to mean “a short period wherein we toss our promises to retired workers and then come back to life as a company”, I’m afraid that Detroit may signal the emergence of a new legal device for cities to do the same thing, especially the tossing out of promises to retired workers part. A kind of coordinated bankruptcy if you will.

It comes down to the following questions. For whom do laws work? Who can trust that, when they enter a legal obligation, it will be honored?

From Trayvon Martin to the people who have been illegally foreclosed on, we’ve seen the answer to that.

And then we might ask, for whom are laws written or exceptions made? And the answer to that might well be for banks, in times of crisis of their own doing, and so they can get their bonuses.

I’m not a huge fan of the original bailouts, because it ignored the social and legal contracts in the opposite way, that failures should fail and people who are criminals should go to jail. It didn’t seem fair then, and it still doesn’t now, as JP Morgan posts record $6.4 billion profits in the same quarter that it’s trying to settle a $500 million market manipulation charge.

It’s all very well to rest our arguments on the sanctity of the contract, but if you look around the edges you’ll see whose contracts get ripped up because of fraudulent accounting, and whose bonuses get bigger.

And it brings up the following question: if we bailed out the banks, why not the people of Detroit?

The Stop and Frisk sleight of hand

I’m finishing up an essay called “On Being a Data Skeptic” in which I catalog different standard mistakes people make with data – sometimes unintentionally, sometimes intentionally.

It occurred to me, as I wrote it, and as I read the various press conferences with departing mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly when they addressed the Stop and Frisk policy, that they are guilty of making one of these standard mistakes. Namely, they use a sleight of hand with respect to the evaluation metric of the policy.

Recall that an evaluation metric for a model is the way you decide whether the model works. So if you’re predicting whether someone would like a movie, you should go back and check whether your recommendations were good, and revise your model if not. It’s a crucial part of the model, and a poor choice for it can have dire consequences – you could end up optimizing to the wrong thing.

[Aside: as I’ve complained about before, the Value Added Model for teachers doesn’t have an evaluation method of record, which is a very bad sign indeed about the model. And that’s a Bloomberg brainchild as well.]

So what am I talking about?

Here’s the model: stopping and frisking suspicious-looking people in high-crime areas will improve the safety and well-being of the city as a whole.

Here’s Bloomberg/Kelly’s evaluation method: the death rate by murder has gone down in New York during the policy. However, that rate is highly variable and depends just as much on whether there’s a crack epidemic going on as anything else. Or maybe it’s improved medical care. Truth is people don’t really know. In any case ascribing credit for the plunging death rate to Stop and Frisk is a tenuous causal argument. Plus since Stop and Frisk events have decreased drastically recently, we haven’t seen the murder rate shoot up.

Here’s another possible evaluation method: trust in the police. And considering that 400,000 innocent black and Latino New Yorkers were stopped last year under this policy (here are more stats), versus less than 50,000 whites, and most of them were young men, it stands to reason that the average young minority male feels less trust towards police than the average young white male. In fact, this is an amazing statistic put together by the NYCLU from 2011:

The number of stops of young black men exceeded the entire city population of young black men (168,126 as compared to 158,406).

If I’m a black guy I have an expectation of getting stopped and frisked at least once per year. How does that make me trust cops?

Let’s choose an evaluation method closer to what we can actually control, and let’s optimize to it.

Update: a guest columnist fills in for David Brooks, hopefully not for the last time, and gives us his take on Kelly, Obama, and racial profiling.

The creepy mindset of online credit scoring

Usually I like to think through abstract ideas – thought experiments, if you will – and not get too personal. I take exceptions for certain macroeconomists who are already public figures but most of the time that’s it.

Here’s a new category of people I’ll call out by name: CEO’s who defend creepy models using the phrase “People will trade their private information for economic value.”

That’s a quote of Douglas Merrill, CEO of Zest Finance, taken from this video taken at a recent data conference in Berkeley (hat tip Rachel Schutt). It was a panel discussion, the putative topic of which was something like “Attacking the structure of everything”, whatever that’s supposed to mean (I’m guessing it has something to do with being proud of “disrupting shit”).

Do you know the feeling you get when you’re with someone who’s smart, articulate, who probably buys organic eggs from a nice farmer’s market, but who doesn’t expose an ounce of sympathy for people who aren’t successful entrepreneurs? When you’re with someone who has benefitted so entirely and so consistently from the system that they have an almost religious belief that the system is perfect and they’ve succeeded through merit alone?

It’s something in between the feeling that, maybe you’re just naive because you’ve led such a blessed life, or maybe you’re actually incapable of human empathy, I don’t know which because it’s never been tested.

That’s the creepy feeling I get when I hear Douglas Merrill speak, but it actually started earlier, when I got the following email almost exactly one year ago via LinkedIn:

Hi Catherine,

Your profile looked interesting to me.

I’m seeking stellar, creative thinkers like you, for our team in Hollywood, CA. If you would consider relocating for the right opportunity, please read on.

You will use your math wizardry to develop radically new methods for data access, manipulation, and modeling. The outcome of your work will result in game-changing software and tools that will disrupt the credit industry and better serve millions of Americans.

You would be working alongside people like Douglas Merrill – the former CIO of Google – along with a handful of other ex-Googlers and Capital One folks. More info can be found on our LinkedIn company profile or at www.ZestFinance.com.

At ZestFinance we’re bringing social responsibility to the consumer loan industry.

Do you have a few moments to talk about this? If you are not interested, but know someone else who might be a fit, please send them my way!

I hope to hear from you soon. Thank you for your time.

Regards,

Adam

Wow, let’s “better serve millions of Americans” through manipulation of their private data, and then let’s call it being socially responsible! And let’s work with Capital One which is known to be practically a charity.

What?

Message to ZestFinance: “getting rich with predatory lending” doesn’t mean “being socially responsible” unless you have a really weird definition of that term.

Going back to the video, I have a few more tasty quotes from Merrill:

- First when he’s describing how he uses personal individual information scraped from the web: “All data is credit data.”

- Second, when he’s comparing ZestFinance to FICO credit scoring: “Context is developed by knowing thousands of things about you. I know you as a person, not just you via five or six variables.”

I’d like to remind people that, in spite of the creepiness here, and the fact that his business plan is a death spiral of modeling, everything this guy is talking about is totally legal. And as I said in this post, I’d like to see some pushback to guys like Merrill as well as to the NSA.

The regressive domestic complexity tax

I’ve been keeping tabs on hard it is to do my bills. I did my bills last night, and man, I’m telling you, I used all of my organizational abilities, all of my customer service experience, and quite a bit of my alpha femaleness just to get it done. Not to mention I needed more than 2 hours of time which I squeezed out by starting the bills while waiting for take-out.

By the way, I am not one of those sticklers for doing everything myself – I have an accountant, and I don’t read those forms, I just sign them and pray. But even so, removing tax issues from the conversation, the kind of expertise required to do my monthly bills is ridiculous and getting worse.

Take medical bills. I have three kids, so there’s always a few appointments pending, but it’s absolutely amazing to me how often I’m getting charged for appointments unfairly. I recently got charged for a physical for my 10-year-old son, even though I know that physicals are free thanks to ObamaCare.

So I call up my insurance company and complain, spend 15 minutes on the phone waiting, then it turns out he isn’t allowed to have more than one physical in a 12-month period which is why it was charged to me. But wait, he had one last April and one this April, what gives? Turns out last April it was on the 14th and this April it was on the 8th. So less than one year.

But surely, I object, you can’t ask for people to always be exactly 12 months apart or more! It turns out that, yes, they have a 30-day grace period for this exact reason, but for some reason it’s not automatic – it requires a person to call and complain to the insurance company to get their son’s physical covered.

Do you see what I mean? This is not actually a coincidence – insurance companies make big money from having non-automatic grace periods, because many people don’t have the time, the patience, and the pushiness to make them do it right, and that’s free money for insurance companies.

There are the (abstract) “rules” and then there’s what actually happens, and it’s a constant battle between what you know you’re paying for which you shouldn’t be and how much your time is worth. For example, if it’s less than $50 I just pay it even if it’s not reasonable. I’m sure other people have different limits.

I see this as a systemic problem. So this isn’t a diatribe against just insurance companies, because I have to jump through about 15 hoops a month like this just to get my paperwork sorted out, and they are mostly not medical issues. This is really a diatribe against complexity, and the regressive tax that complexity projects onto our society.

Rich people have people to work out their paperwork for them. People like me, we don’t have people to do this, but we have the time, skills, and patience to do it ourselves (and the money to buy takeout while we do it). There are plenty of people with no time, or who aren’t organized to have all the information they need at their fingertips when they make these calls, or are too intimidated by customer service phone lines to work it out.

And, as in the example above, there’s usually a perverse incentive for complexity to exist – people give up and pay extra because it’s not worth doing the paperwork. That means it’s always getting worse.

Bottomline: you shouldn’t need to have a college degree and customer service experience to do your bills. I’d love to see an estimate of how much more in unnecessary fees and accounting errors are paid by the poor in this country.

Payroll cards: “It costs too much to get my money” (#OWS)

If this article from yesterday’s New York Times doesn’t make you want to join Occupy, then nothing will.

It’s about how, if you work at a truly crappy job like Walmart or McDonalds, they’ll pay you with a pre-paid card that charges you for absolutely everything, including checking your balance or taking your money, and will even charge you for not using the card. Because we aren’t nickeling and diming these people enough.

The companies doing this stuff say they’re “making things convenient for the workers,” but of course they’re really paying off the employers, sometimes explicitly:

In the case of the New York City Housing Authority, it stands to receive a dollar for every employee it signs up to Citibank’s payroll cards, according to a contract reviewed by The New York Times.

Thanks for the convenience, payroll card banks!

One thing that makes me extra crazy about this article is how McDonalds uses its franchise system to keep its hands clean:

For Natalie Gunshannon, 27, another McDonald’s worker, the owners of the franchise that she worked for in Dallas, Pa., she says, refused to deposit her pay directly into her checking account at a local credit union, which lets its customers use its A.T.M.’s free. Instead, Ms. Gunshannon said, she was forced to use a payroll card issued by JPMorgan Chase. She has since quit her job at the drive-through window and is suing the franchise owners.

“I know I deserve to get fairly paid for my work,” she said.

The franchise owners, Albert and Carol Mueller, said in a statement that they comply with all employment, pay and work laws, and try to provide a positive experience for employees. McDonald’s itself, noting that it is not named in the suit, says it lets franchisees determine employment and pay policies.

I actually heard about this newish scheme against the poor when I attended the CFPB Town Hall more than a year ago and wrote about it here. Actually that’s where I heard people complain about Walmart doing this but also court-appointed child support as well.

Just to be clear, these fees are illegal in the context of credit cards, but financial regulation has not touched payroll cards yet. Yet another way that the poor are financialized, which is to say they’re physically and psychologically separated from their money. Get on this, CFPB!

Update: an excellent article about this issue was written by Sarah Jaffe a couple of weeks ago (hat tip Suresh Naidu). It ends with an awesome quote by Stephen Lerner: “No scam is too small or too big for the wizards of finance.”

Where’s the outrage over private snooping?

There’s been a tremendous amount of hubbub recently surrounding the data collection data mining that the NSA has been discovered to be doing.

For me what’s weird is that so many people are up in arms about what our government knows about us but not, seemingly, about what private companies know about us.

I’m not suggesting that we should be sanguine about the NSA program – it’s outrageous, and it’s outrageous that we didn’t know about it. I’m glad it’s come out into the open and I’m glad it’s spawned an immediate and public debate about the citizen’s rights to privacy. I just wish that debate extended to privacy in general, and not just the right to be anonymous with respect to the government.

What gets to me are the countless articles that make a big deal of Facebook or Google sharing private information directly with the government, while never mentioning that Acxiom buys and sells from Facebook on a daily basis much more specific and potentially damning information about people (most people in this country) than the metadata that the government purports to have.

Of course, we really don’t have any idea what the government has or doesn’t have. Let’s assume they are also an Acxiom customer, for that matter, which stands to reason.

It begs the question, at least to me, of why we distrust the government with our private data but we trust private companies with our private data. I have a few theories, tell me if you agree.

Theory 1: people think about worst case scenarios, not probabilities

When the government is spying on you, worst case you get thrown into jail or Guantanamo Bay for no good reason, left to rot. That’s horrific but not, for the average person, very likely (although, of course, a world where that does become likely is exactly what we want to prevent by having some concept of privacy).

When private companies are spying on you, they don’t have the power to put you in jail. They do increasingly have the power, however, to deny you a job, a student loan, a mortgage, and life insurance. And, depending on who you are, those things are actually pretty likely.

Theory 2: people think private companies are only after our money

Private companies who hold our private data are only profit-seeking, so the worst thing they can do is try to get us to buy something, right? I don’t think so, as I pointed out above. But maybe people think so in general, and that’s why we’re not outraged about how our personal data and profiles are used all the time on the web.

Theory 3: people are more afraid of our rights being taken away than good things not happening to them

As my friend Suresh pointed out to me when I discussed this with him, people hold on to what they have (constitutional rights) and they fear those things being taken away (by the government). They spend less time worrying about what they don’t have (a house) and how they might be prevented from getting it (by having a bad e-score).

So even though private snooping can (and increasingly does) close all sorts of options for peoples’ lives, if they don’t think about them, they don’t notice. It’s hard to know why you get denied a job, especially if you’ve been getting worse and worse credit card terms and conditions over the years. In general it’s hard to notice when things don’t happen.

Theory 4: people think the government protects them from bad things, but who’s going to protect them from the government?

This I totally get, but the fact is the U.S. government isn’t protecting us from data collectors, and has even recently gotten together with Facebook and Google to prevent the European Union from enacting pretty good privacy laws. Let’s not hold our breath for them to understand what’s at stake here.

(Updated) Theory 5: people think they can opt out of private snooping but can’t opt out of being a citizen

Two things. First, can you really opt out? You can clear your cookies and not be on gmail and not go on Facebook and Acxiom will still track you. Believe it.

Second, I’m actually not worried about you (you reader of mathbabe) or myself for that matter. I’m not getting denied a mortgage any time soon. It’s the people who don’t know to protect themselves, don’t know to opt out, that I’m worried about and who will get down-scored and funneled into bad options that I worry about.

Theory 5 6: people just haven’t thought about it enough to get pissed

This is the one I’m hoping for.

I’d love to see this conversation expand to include privacy in general. What’s so bad about asking for data about ourselves to be automatically forgotten, say by Verizon, if we’ve paid our bills and 6 months have gone by? What’s so bad about asking for any personal information about us to have a similar time limit? I for one do not wish mistakes my children make when they’re impetuous teenagers to haunt them when they’re trying to start a family.

When is shaming appropriate?

As a fat person, I’ve dealt with a lot of public shaming in my life. I’ve gotten so used to it, I’m more an observer than a victim most of the time. That’s kind of cool because it allows me to think about it abstractly.

I’ve come up with three dimensions for thinking about this issue.

- When is shame useful?

- When is it appropriate?

- When does it help solve a problem?

Note it can be useful even if it doesn’t help solve a problem – one of the characteristics of shame is that the person doing the shaming has broken off all sense of responsibility for whatever the issue is, and sometimes that’s really the only goal. If the shaming campaign is effective, the shamed person or group is exhibited as solely responsible, and the shamer does not display any empathy. It hasn’t solved a problem but at least it’s clear who’s holding the bag.

The lack of empathy which characterizes shaming behavior makes it very easy to spot. And extremely nasty.

Let’s look at some examples of shaming through this lens:

Useful but not appropriate, doesn’t solve a problem

Example 1) it’s both fat kids and their parents who are to blame for childhood obesity:

Example 2) It’s poor mothers that are to blame for poverty:

These campaigns are not going to solve any problems, but they do seem politically useful – a way of doubling down on the people suffering from problems in our society. Not only will they suffer from them, but they will also be blamed for them.

Inappropriate, not useful, possibly solving a short-term discipline problem

Let’s go back to parenting, which everyone seems to love talking about, if I can go by the number of comments on my recent post in defense of neglectful parenting.

One of my later commenters, Deane, posted this article from Slate about how the Tiger Mom approach to shaming kids into perfection produces depressed, fucked-up kids:

Hey parents: shaming your kids might solve your short-term problem of having independent-minded kids, but it doesn’t lead to long-term confidence and fulfillment.

Appropriate, useful, solves a problem

Here’s when shaming is possibly appropriate and useful and solves a problem: when there have been crimes committed that affect other people needlessly or carelessly, and where we don’t want to let it happen again.

For example, the owner of the Bangladeshi factory which collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people got arrested and publicly shamed. This is appropriate, since he knowingly put people at risk in a shoddy building and added three extra floors to improve his profits.

Note shaming that guy isn’t going to bring back those dead people, but it might prevent other people from doing what he did. In that sense it solves the problem of seemingly nonexistent safety codes in Bangladesh, and to some extent the question of how much we Americans care about cheap clothes versus conditions in factories which make our clothes. Not completely, of course. Update: Major Retailers Join Plan for Greater Safety in Bangladesh

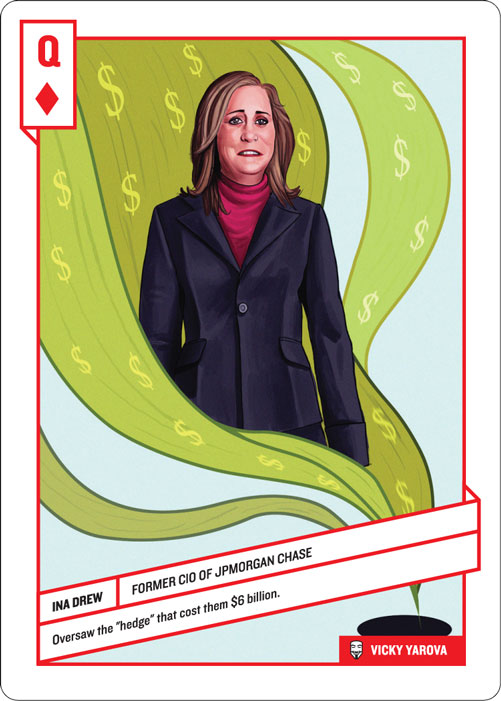

Another example of appropriate shame would be some of the villains of the financial crisis. We in Alt Banking did our best in this regard when we made the 52 Shades of Greed card deck. Here’s Robert Rubin:

Conclusion

I’m no expert on this stuff, but I do have a way of looking at it.

One thing about shame is that the people who actually deserve shame are not particularly susceptible to feeling it (I saw that first hand when I saw Ina Drew in person last month, which I wrote about here). Some people are shameless.

That means that shame, whatever its purpose, is not really about making an individual change their behavior. Shame is really more about setting the rules of society straight: notifying people in general about what’s acceptable and what’s not.

From my perspective, we’ve shown ourselves much more willing to shame poor people, fat people, and our own children than to shame the actual villains who walk among us who deserve such treatment.

Shame on us.

The rise of big data, big brother

I recently read an article off the newsstand called The Rise of Big Data.

It was written by Kenneth Neil Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger and it was published in the May/June 2013 edition of Foreign Affairs, which is published by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). I mention this because CFR is an influential think tank, filled with powerful insiders, including people like Robert Rubin himself, and for that reason I want to take this view on big data very seriously: it might reflect the policy view before long.

And if I think about it, compared to the uber naive view I came across last week when I went to the congressional hearing about big data and analytics, that would be good news. I’ll write more about it soon, but let’s just say it wasn’t everything I was hoping for.

At least Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger discuss their reservations regarding “big data” in this article. To contrast this with last week, it seemed like the only background material for the hearing, at least for the congressmen, was the McKinsey report talking about how sexy data science is and how we’ll need to train an army of them to stay competitive.

So I’m glad it’s not all rainbows and sunshine when it comes to big data in this article. Unfortunately, whether because they’re tied to successful business interests, or because they just haven’t thought too deeply about the dark side, their concerns seem almost token, and their examples bizarre.

The article is unfortunately behind the pay wall, but I’ll do my best to explain what they’ve said.

Datafication

First they discuss the concept of datafication, and their example is how we quantify friendships with “likes”: it’s the way everything we do, online or otherwise, ends up recorded for later examination in someone’s data storage units. Or maybe multiple storage units, and maybe for sale.

They formally define later in the article as a process:

… taking all aspect of life and turning them into data. Google’s augmented-reality glasses datafy the gaze. Twitter datafies stray thoughts. LinkedIn datafies professional networks.

Datafication is an interesting concept, although as far as I can tell they did not coin the word, and it has led me to consider its importance with respect to intentionality of the individual.

Here’s what I mean. We are being datafied, or rather our actions are, and when we “like” someone or something online, we are intending to be datafied, or at least we should expect to be. But when we merely browse the web, we are unintentionally, or at least passively, being datafied through cookies that we might or might not be aware of. And when we walk around in a store, or even on the street, we are being datafied in an completely unintentional way, via sensors or Google glasses.

This spectrum of intentionality ranges from us gleefully taking part in a social media experiment we are proud of to all-out surveillance and stalking. But it’s all datafication. Our intentions may run the gambit but the results don’t.

They follow up their definition in the article, once they get to it, with a line that speaks volumes about their perspective:

Once we datafy things, we can transform their purpose and turn the information into new forms of value

But who is “we” when they write it? What kinds of value do they refer to? As you will see from the examples below, mostly that translates into increased efficiency through automation.

So if at first you assumed they mean we, the American people, you might be forgiven for re-thinking the “we” in that sentence to be the owners of the companies which become more efficient once big data has been introduced, especially if you’ve recently read this article from Jacobin by Gavin Mueller, entitled “The Rise of the Machines” and subtitled “Automation isn’t freeing us from work — it’s keeping us under capitalist control.” From the article (which you should read in its entirety):

In the short term, the new machines benefit capitalists, who can lay off their expensive, unnecessary workers to fend for themselves in the labor market. But, in the longer view, automation also raises the specter of a world without work, or one with a lot less of it, where there isn’t much for human workers to do. If we didn’t have capitalists sucking up surplus value as profit, we could use that surplus on social welfare to meet people’s needs.

The big data revolution and the assumption that N=ALL

According to Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger, the Big Data revolution consists of three things:

- Collecting and using a lot of data rather than small samples.

- Accepting messiness in your data.

- Giving up on knowing the causes.

They describe these steps in rather grand fashion, by claiming that big data doesn’t need to understand cause because the data is so enormous. It doesn’t need to worry about sampling error because it is literally keeping track of the truth. The way the article frames this is by claiming that the new approach of big data is letting “N = ALL”.

But here’s the thing, it’s never all. And we are almost always missing the very things we should care about most.

So for example, as this InfoWorld post explains, internet surveillance will never really work, because the very clever and tech-savvy criminals that we most want to catch are the very ones we will never be able to catch, since they’re always a step ahead.

Even the example from their own article, election night polls, is itself a great non-example: even if we poll absolutely everyone who leaves the polling stations, we still don’t count people who decided not to vote in the first place. And those might be the very people we’d need to talk to to understand our country’s problems.

Indeed, I’d argue that the assumption we make that N=ALL is one of the biggest problems we face in the age of Big Data. It is, above all, a way of excluding the voices of people who don’t have the time or don’t have the energy or don’t have the access to cast their vote in all sorts of informal, possibly unannounced, elections.

Those people, busy working two jobs and spending time waiting for buses, become invisible when we tally up the votes without them. To you this might just mean that the recommendations you receive on Netflix don’t seem very good because most of the people who bother to rate things are Netflix are young and have different tastes than you, which skews the recommendation engine towards them. But there are plenty of much more insidious consequences stemming from this basic idea.

Another way in which the assumption that N=ALL can matter is that it often gets translated into the idea that data is objective. Indeed the article warns us against not assuming that:

… we need to be particularly on guard to prevent our cognitive biases from deluding us; sometimes, we just need to let the data speak.

And later in the article,

In a world where data shape decisions more and more, what purpose will remain for people, or for intuition, or for going against the facts?

This is a bitch of a problem for people like me who work with models, know exactly how they work, and know exactly how wrong it is to believe that “data speaks”.

I wrote about this misunderstanding here, in the context of Bill Gates, but I was recently reminded of it in a terrifying way by this New York Times article on big data and recruiter hiring practices. From the article:

“Let’s put everything in and let the data speak for itself,” Dr. Ming said of the algorithms she is now building for Gild.

If you read the whole article, you’ll learn that this algorithm tries to find “diamond in the rough” types to hire. A worthy effort, but one that you have to think through.

Why? If you, say, decided to compare women and men with the exact same qualifications that have been hired in the past, but then, looking into what happened next you learn that those women have tended to leave more often, get promoted less often, and give more negative feedback on their environments, compared to the men, your model might be tempted to hire the man over the woman next time the two showed up, rather than looking into the possibility that the company doesn’t treat female employees well.

In other words, ignoring causation can be a flaw, rather than a feature. Models that ignore causation can add to historical problems instead of addressing them. And data doesn’t speak for itself, data is just a quantitative, pale echo of the events of our society.

Some cherry-picked examples

One of the most puzzling things about the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article is how they chose their “big data” examples.

One of them, the ability for big data to spot infection in premature babies, I recognized from the congressional hearing last week. Who doesn’t want to save premature babies? Heartwarming! Big data is da bomb!

But if you’re going to talk about medicalized big data, let’s go there for reals. Specifically, take a look at this New York Times article from last week where a woman traces the big data footprints, such as they are, back in time after receiving a pamphlet on living with Multiple Sclerosis. From the article:

Now she wondered whether one of those companies had erroneously profiled her as an M.S. patient and shared that profile with drug-company marketers. She worried about the potential ramifications: Could she, for instance, someday be denied life insurance on the basis of that profile? She wanted to track down the source of the data, correct her profile and, if possible, prevent further dissemination of the information. But she didn’t know which company had collected and shared the data in the first place, so she didn’t know how to have her entry removed from the original marketing list.

Two things about this. First, it happens all the time, to everyone, but especially to people who don’t know better than to search online for diseases they actually have. Second, the article seems particularly spooked by the idea that a woman who does not have a disease might be targeted as being sick and have crazy consequences down the road. But what about a woman is actually is sick? Does that person somehow deserve to have their life insurance denied?

The real worries about the intersection of big data and medical records, at least the ones I have, are completely missing from the article. Although they did mention that “improving and lowering the cost of health care for the world’s poor” inevitable will lead to “necessary to automate some tasks that currently require human judgment.” Increased efficiency once again.

To be fair, they also talked about how Google tried to predict the flu in February 2009 but got it wrong. I’m not sure what they were trying to say except that it’s cool what we can try to do with big data.

Also, they discussed a Tokyo research team that collects data on 360 pressure points with sensors in a car seat, “each on a scale of 0 to 256.” I think that last part about the scale was added just so they’d have more numbers in the sentence – so mathematical!

And what do we get in exchange for all these sensor readings? The ability to distinguish drivers, so I guess you’ll never have to share your car, and the ability to sense if a driver slumps, to either “send an alert or atomatically apply brakes.” I’d call that a questionable return for my investment of total body surveillance.

Big data, business, and the government

Make no mistake: this article is about how to use big data for your business. It goes ahead and suggests that whoever has the biggest big data has the biggest edge in business.

Of course, if you’re interested in treating your government office like a business, that’s gonna give you an edge too. The example of Bloomberg’s big data initiative led to efficiency gain (read: we can do more with less, i.e. we can start firing government workers, or at least never hire more).

As for regulation, it is pseudo-dealt with via the discussion of market dominance. We are meant to understand that the only role government can or should have with respect to data is how to make sure the market is working efficiently. The darkest projected future is that of market domination by Google or Facebook:

But how should governments apply antitrust rules to big data, a market that is hard to define and is constantly changing form?

In particular, no discussion of how we might want to protect privacy.

Big data, big brother

I want to be fair to Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger, because they do at least bring up the idea of big data as big brother. Their topic is serious. But their examples, once again, are incredibly weak.

Should we find likely-to-drop-out boys or likely-to-get-pregnant girls using big data? Should we intervene? Note the intention of this model would be the welfare of poor children. But how many models currently in production are targeting that demographic with that goal? Is this in any way at all a reasonable example?

Here’s another weird one: they talked about the bad metric used by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in the Viet Nam War, namely the number of casualties. By defining this with the current language of statistics, though, it gives us the impression that we could just be super careful about our metrics in the future and: problem solved. As we experts in data know, however, it’s a political decision, not a statistical one, to choose a metric of success. And it’s the guy in charge who makes that decision, not some quant.

Innovation

If you end up reading the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article, please also read Julie Cohen’s draft of a soon-to-be published Harvard Law Review article called “What Privacy is For” where she takes on big data in a much more convincing and skeptical light than Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger were capable of summoning up for their big data business audience.

I’m actually planning a post soon on Cohen’s article, which contains many nuggets of thoughtfulness, but for now I’ll simply juxtapose two ideas surrounding big data and innovation, giving Cohen the last word. First from the Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger article:

Big data enables us to experiment faster and explore more leads. These advantages should produce more innovation

Second from Cohen, where she uses the term “modulation” to describe, more or less, the effect of datafication on society:

When the predicate conditions for innovation are described in this way, the problem with characterizing privacy as anti-innovation becomes clear: it is modulation, not privacy, that poses the greater threat to innovative practice. Regimes of pervasively distributed surveillance and modulation seek to mold individual preferences and behavior in ways that reduce the serendipity and the freedom to tinker on which innovation thrives. The suggestion that innovative activity will persist unchilled under conditions of pervasively distributed surveillance is simply silly; it derives rhetorical force from the cultural construct of the liberal subject, who can separate the act of creation from the fact of surveillance. As we have seen, though, that is an unsustainable fiction. The real, socially-constructed subject responds to surveillance quite differently—which is, of course, exactly why government and commercial entities engage in it. Clearing the way for innovation requires clearing the way for innovative practice by real people, by preserving spaces within which critical self-determination and self-differentiation can occur and by opening physical spaces within which the everyday practice of tinkering can thrive.

Who’s tracking the trackers?

This is a guest post by Josh Snodgrass.

As the Mathbabe noted recently, a lot of companies are collecting a lot of information about you. Thanks to two Firefox add-ons – Collusion (hat tip to Cathy) and NoScript — you can watch the process and even interfere with it to a degree.

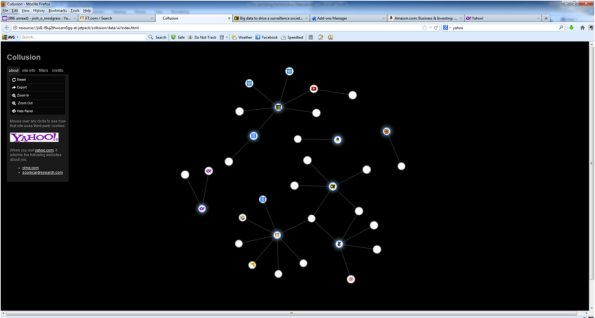

Collusion is a beautiful app that creates a network graph of the various companies that have information about your web activity. Here is an example.

On this graph, I can see that nytimes.com has sent info on me to 2mdn.net, linkstorm.net, serving-sys.com, nyt.com and doubleclick.net. Who are these guys? All I know is that they know more about me than I know about them.

Doubleclick is particularly well-informed. They have gotten information on me from nytimes.com, yahoo.com and ft.com. You may not be able to see it on the picture but there are faint links between the nodes. Some (few) of the nodes are sites I have visited. Most of the nodes, especially some of the central ones are data collectors such as doubleclick and googleanalytics. They have gotten info from sites I’ve visited.

This graph is pretty sparse because I cleared all of my cookies recently. If I let it go for a week and the graph will be so crowded it won’t all fit on a screen.

Pretty much everyone is sharing info about me (and presumably you, too). And, I do mean everyone. Mathbabe is a dot near the top. Collusion tells me that mathbabe.org has shared info with google.com, wordpress.com, wp.com, 52shadesofgreed.com, youtube.com and quantserve.com. Google has passed the info on to googleusercontent.com and gstatic.com

I can understand why. WordPress and presumably wp.com are hosting her blog. Google is providing search capabilities. 52shadesofgreed has an ad posted (You can still buy the decks but even better, come to Alt-Banking meetings and get one free). Youtube is providing some content. It is all innocent enough in a way but it means my surfing is being tracked even on non-commercial sites.

These are the conveniences of modern life. Try blocking all cookies and you will find it pretty inconvenient to use the internet. It would be nice to be selective about cookies but that seems very hard. All of this is happening even though I’ve told my browser not to allow third-party cookies. If you look at cookie policies, it seems you have two alternatives:

- Block all cookies and the site won’t work very well

- Allow cookies and we will send your info to whomever we choose (within the law, of course).

So, it would be nice if there were a law that constrained what they do. My impression is that we Americans have virtually no protection. Europe is better from what I understand.

I’ve found another add-on called NoScript that is very helpful but also very disturbing. It tells you about JavaScripts that want to run when you visit a site.

I’m trying to access a site and there are scripts waiting to run from:

- Brightcove.com

- Quantserve.com

- Facebook.com

- Po.st Scorecard.com

- Wxug.com

- Admeld.com

- Googleadservices.com

- Legolas-media.com

- Criteo.com

- Crwdcntrl.com

Clearly a lot of those are about tracking me or showing me ads. As with cookies, if you block all the scripts, the site probably won’t function properly. But the great thing about NoScript is that is makes it easy to allow scripts one by one. So, you can allow the ones that look more legitimate until the site works well enough. Also, you can allow them temporarily.

NoScript and Collusion are great. But mostly they are making me more aware of all the tracking that is going on. And they are also making it clear how hard it is to keep your privacy.

This isn’t just on the internet. Years ago, an economist had an idea about having people put boxes on their cars that would track where they went and charge them for driving, particularly in high congestion times and places. The motivation was to reduce travel that causes a lot of pollution while no one is going anywhere. But people ridiculed the idea. Who would let themselves be tracked everywhere they went.

Well, 40 years later, nearly everyone who has a car has an EZ-pass. And, even if you don’t, they will take a picture of your license plate and keep it on file. All in the name of improving traffic flow.

And, if you use credit cards, there are some big companies that have records of your spending.

What to do about this?

I don’t know.

I like conveniences. Keeping your privacy is hard. DuckDuckGo is a search engine that doesn’t track you (another hat tip to Cathy). But their search results are not as good as Google’s.

Google has all these nice tools that are free. Even if you don’t use them, the web sites you visit surely do. And if they do, google is getting information from them, about you.

This experience has made me even more of a fan of Firefox and add-ons available in it. But what else should I use. And, none of these tools is going to be perfect.

What information gets tracked? A lot of privacy policies say they don’t give out identifying information. But how can we tell?

Just keeping on top of what is going on is hard. For example: what are LSOs? They seem to be a kind of “supercookies”. And Better Privacy seems to be an add-on to help with them.

FT.com’s cookie policy tells me that:

“Our emails may contain a single, campaign-unique “web beacon pixel” to tell us whether our emails are opened and verify any clicks through to links or advertisements within the email”

Who knew that a pixel could do so much?

The truth is, I want to see these sites. So I am enabling scripts (some of them, as few as I can). The question is how to make the tradeoff. Figuring that out is time consuming. I’ve got better things to do with my life.

I’m going to go read a book.

10 reasons to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting tomorrow (#OWS)

The Alternative Banking group of #OWS is showing up bright and early tomorrow morning to protest at Citigroup’s annual shareholder meeting. Details are: we meet outside the Hilton Hotel, Sixth Avenue between 53rd and 54th Streets, tomorrow, April 24th, from 8-10 am. We’ve already made some signs (see below).

Here are ten reasons for you to join us.

1) The Glass-Steagall Act, which had protected the banking system since 1933, was repealed in order to allow Citibank and Traveler’s Insurance to merge.

In fact they merged before the act was even revoked, giving us a great way to date the moment when politicians started taking orders from bankers – at the time, President Bill Clinton publicly declared that “the Glass–Steagall law is no longer appropriate.”

2) The crimes Citi has committed have not been met with reasonable punishments.

From this Bloomberg article:

In its complaint against Citigroup, the SEC said the bank misled investors in a $1 billion fund that included assets the bank had projected would lose money. At the same time it was selling the fund to investors, Citigroup took a short position in many of the underlying assets, according to the agency.

The SEC only attempted to fine Citi $285 million, even though Citi’s customers lost on the order of $600 million from their fraud. Moreover, they were not required to admit wrongdoing. Judge Rakoff refused to sign off on the deal and it’s still pending. Citi is one of those banks that is simply too big to jail.

3) We’d like our pen back, Mr. Weill. Going back to repealing Glass-Steagall. Let’s take an excerpt from this article:

…at the signing ceremony of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley, aka the Glass Steagall repeal act, Clinton presented Weill with one of the pens he used to “fine-tune” Glass-Steagall out of existence, proclaiming, “Today what we are doing is modernizing the financial services industry, tearing down those antiquated laws and granting banks significant new authority.”

Weill has since decided that repealing Glass-Steagall was a mistake.

4) Do you remember the Plutonomy Memos? I wrote about them here. Here’s a tasty excerpt which helps us remember when the class war was started and by whom:

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization… Since we think the plutonomy is here, is going to get stronger… It is a good time to switch out of stocks that sell to the masses and back to the plutonomy basket.

5) Robert Rubin – enough said. To say just a wee bit more, let’s look at the Bloomberg Businessweek article, “Rethinking Robert Rubin”:

Rubinomics—his signature economic philosophy, in which the government balances the budget with a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, driving borrowing rates down—was the blueprint for an economy that scraped the sky. When it collapsed, due in part to bank-friendly policies that Rubin advocated, he made more than $100 million while others lost everything.

That $100 million was made at Citigroup, which was later bailed out because of bets Rubin helped them make. He has thus far shown no remorse.

6) The Revolving Door problems Citigroup has. Bill Moyers has a great article on the outrageous revolving door going straight from banks to the Treasury and the White House. What with Rubin and Lew, Citigroup seems pretty much a close second behind Goldman Sachs for this sport.

7) The bailout. Citigroup took $100 billion from the Fed at the height of the bailout in January 2009.

8) The bailout was actually for Citigroup. If you’ve read Sheila Bair’s book Bull by the Horns, you’ll see the bailout from her inside perspective. And it was this: that Citigroup was really the bank that needed it worst. That in fact, the whole bailout was a cover for funneling money to Citi.

9) The ongoing Fed dole. The bailout is still going on – and Citigroup is currently benefitting from the easy money that the Fed is offering, not to mention the $83 billion taxpayer subsidy. WTF?!

10) Lobbying for yet more favors. Citi spent $62 million from 2001 to 2010 on lobbying in Washington. What’s their return on that investment, do you think?

Join us tomorrow morning! Details here.

Ina Drew: heinously greedy or heinously incompetent?

Last night I went to an event at Barnard where Ina Drew, ex-CIO head of JP Morgan Chase, who oversaw the London Whale fiasco, was warmly hosted and interviewed by Barnard president Debora Spar.

[Aside: I was going to link to Ina Drew’s wikipedia entry in the above paragraph, but it was so sanitized that I couldn’t get myself to do it. She must have paid off lots of wiki editors to keep herself this clean. WTF, wikipedia??]

A little background in case you don’t know who this Drew woman is. She was in charge of balance-sheet risk management and somehow managed to not notice losing $6.2 billion dollars in the group she was in charge of, which was meant to hedge risk, at least according to CEO Jamie Dimon. She made $15 million per year for her efforts and recently retired.

In her recent Congressional testimony (see Example 3 in this recent post), she threw the quants with their Ph.D.’s under the bus even though the Senate report of the incident noted multiple risk limits being exceeded and ignored, and then risk models themselves changed to look better, as well as the “whale” trader Bruno Iksil‘s desire to get out of his losing position being resisted by upper management (i.e. Ina Drew).

I’m not going to defend Iksil for that long, but let’s be clear: he fucked up, and then was kept in his ridiculous position by Ina Drew because she didn’t want to look bad. His angst is well-documented in the Senate report, which you should read.

Actually, the whole story is somewhat more complicated but still totally stupid: instead of backing out of certain credit positions the old-fashioned and somewhat expensive way, the CIO office decided to try to reduce its capital requirements via reducing (manipulated) VaR, but ended up increasing their capital requirements in other, non-VaR ways (specifically, the “comprehensive risk measure”, which isn’t as manipulable as VaR). Read more here.

Maybe Ina is going to claim innocence, that she had no idea what was going on. In that case, she had no control over her group and its huge losses. So either she’s heinously greedy or heinously incompetent. My money’s on “incompetent” after seeing and listening to her last night. My live Twitter feed from the event is available here.

We featured Ina Drew on our “52 Shades of Greed” card deck as the Queen of diamonds:

Back to the event.

Why did we cart out Ina Drew in front of an audience of young Barnard women last night? Were we advertising a career in finance to them? Is Drew a role model for these young people?

The best answers I can come up with are terrible:

- She’s a Barnard mom (her daughter was in the audience). Not a trivial consideration, especially considering the potential donor angle.

- President Spar is on the board of Goldman Sachs and there’s a certain loyalty among elites, which includes publicly celebrating colossal failures. Possible, but why now? Is there some kind of perverted female solidarity among women that should be in jail but insist on considering themselves role models? Please count me out of that flavor of feminism.

- President Spar and Ina Drew actually don’t think Drew did anything wrong. This last theory is the weirdest but is the best supported by the tone of the conversation last night. It gives me the creeps. In any case I can no longer imagine supporting Barnard’s mission with that woman as president. It’s sad considering my fond feelings for the place where I was an assistant professor for two years in the math department and which treated me well.

Please suggest other ideas I’ve failed to mention.

New creepy model: job hiring software

Warmup: Automatic Grading Models

Before I get to my main take-down of the morning, let me warm up with an appetizer of sorts: have you been hearing a lot about new models that automatically grade essays?

Does it strike you that’s there’s something wrong with that idea but you don’t know what it is?

Here’s my take. While it’s true that it’s possible to train a model to grade essays similarly to what a professor now does, that doesn’t mean we can introduce automatic grading – at least not if the students in question know that’s what we’re doing.

There’s a feedback loop, whereby if the students know their essays will be automatically graded, then they will change what they’re doing to optimize for good automatic grades rather than, say, a cogent argument.

For example, a student might download a grading app themselves (wouldn’t you?) and run their essay through the machine until it gets a great grade. Not enough long words? Put them in! No need to make sure the sentences make sense, because the machine doesn’t understand grammar!

This is, in fact, a great example where people need to take into account the (obvious when you think about them) feedback loops that their models will enter in actual use.

Job Hiring Models

Now on to the main course.

In this week’s Economist there is an essay about the new widely-used job hiring software and how awesome it is. It’s so efficient! It removes the biases of of those pesky recruiters! Here’s an excerpt from the article:

The problem with human-resource managers is that they are human. They have biases; they make mistakes. But with better tools, they can make better hiring decisions, say advocates of “big data”.

So far “the machine” has made observations such as:

- Good if candidate uses browser you need to download like Chrome.

- Not as bad as one might expect to have a criminal record.

- Neutral on job hopping.

- Great if you live nearby.

- Good if you are on Facebook.

- Bad if you’re on Facebook and every other social networking site as well.

Now, I’m all for learning to fight against our biases and hire people that might not otherwise be given a chance. But I’m not convinced that this will happen that often – the people using the software can always train the model to include their biases and then point to the machine and say “The machine told me to do it”. True.

What I really object to, however, is the accumulating amount of data that is being collected about everyone by models like this.

It’s one thing for an algorithm to take my CV in and note that I misspelled my alma mater, but it’s a different thing altogether to scour the web for my online profile trail (via Acxiom, for example), to look up my credit score, and maybe even to see my persistence score as measured by my past online education activities (soon available for your 7-year-old as well!).

As a modeler, I know how hungry the model can be. It will ask for all of this data and more. And it will mean that nothing you’ve ever done wrong, no fuck-up that you wish to forget, will ever be forgotten. You can no longer reinvent yourself.

Forget mobility, forget the American Dream, you and everyone else will be funneled into whatever job and whatever life the machine has deemed you worthy of. WTF.

Hey WSJ, don’t blame unemployed disabled people for the crap economy

This morning I’m being driven crazy by this article in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal entitled “Workers Stuck in Disability Stunt Economic Recovery.”

Even the title makes the underlying goal of the article crystal clear: the lazy disabled workers are to blame for the crap economy. Lest you are unconvinced that anyone could make such an unreasonable claim of causation, here’s a tasty excerpt from the article that spells it out:

Economic growth is driven by the number of workers in an economy and by their productivity. Put simply, fewer workers usually means less growth.

Since the recession, more people have gone on disability, on net, than new workers have joined the labor force. Mr. Feroli estimated the exodus to disability costs 0.6% of national output, equal to about $95 billion a year.

“The greater cost is their long-term dependency on transfers from the federal government,” Mr. Autor said, “placing strain on the soon-to-be exhausted Social Security Disability trust fund.”

The underlying model here, then, is that there’s a bunch of people who have the choice between going on disability or “joining the labor force” and they’ve all chosen to go on disability. I wonder where their evidence is that people really have that choice, considering the unemployment numbers and participation rate numbers we see nowadays.

For example, the unemployment rate for youths is now 22.9%, and the participation rate for them has gone from 59.2% in December 2007, to 54.5% today. This is probably not because so many kids under the age of 25 are disabled, I suspect. If you look at the overall labor participation rate, it’s dropped from 66.0 in December 2007 to 63.3 in March 2013. Most of the people who have left the work force are also not disabled. They’ve been discouraged for some other mysterious reason. I’m gonna go ahead and guess it’s because they can’t find a job.

This leads me to ask the following question from the journalists LESLIE SCISM and JON HILSENRATH who wrote the article: Where is your evidence of causation??

Here’s another example from the article of a seriously fucked-up understanding of cause and effect:

With overall participation down, the labor force—a measure of people working and people looking for work—is barely growing.

They consistently paint the picture whereby people decide to stop working, and then yucky things happen, in this case the labor force stops growing. Damn those lazy people.

They even bring in a fancy word from physics to describe the problem, namely hysteresis. Now, they didn’t understand or correctly define the term, but it doesn’t really matter, because the point of using a fancy term from physics was not to add to the clarity of the argument but rather to impress.

The goal here is, in fact, that if enough economists use sophisticated language to describe the various effects, we will all be able to blame people with bad backs, making $13.6K per year, on why our economy sucks, rather than the rich assholes in finance who got us into this mess and are currently buying $2 million dollar personal offices instead of going to jail.

Just to be clear, that’s $1,130 a month, which I guess represents so enticing a lifestyle that the people currently enjoying it ‘are “pretty unlikely to want to forfeit economic security for a precarious job market”‘ according to M.I.T. economist David Autor. I’d love to have David Autor spell out, for us, exactly what’s economically secure about that kind of monthly check.

The rest of the article is in large part a description of how people get onto SSDI, insinuating that the people currently on it are not really all that disabled or worthy of living high on the hog, and are in any case never ever leaving.

How’s this for a slightly different take on the situation: there are of course some people who are faking something, that’s always the case. But in general, the people on SSDI need to be there, and before the recession might have had the kind of employers who kept them on even though they often called in sick, out of loyalty and kindness, because they didn’t want to fire them. But when the recession struck those employers had to cut them off, or they went out of business completely. Now those people can’t find work and don’t have many options. In other words, the recession caused the SSDI program to grow. That doesn’t mean it caused a bunch of people to get sick, but it does mean that sick people are more dependent on SSDI because there are fewer options.

By the way, read the comments of this article, there are some really good ones (“What were people with injuries and no high-value job skills to do? Is the number of people in the social security disability program the problem or the symptom?”) as well as some really outrageous ones (‘The current situation makes the picture of the “Welfare Queen” of the 1980s look like an honest citizen’).

We don’t need more complicated models, we need to stop lying with our models

The financial crisis has given rise to a series of catastrophes related to mathematical modeling.

Time after time you hear people speaking in baffled terms about mathematical models that somehow didn’t warn us in time, that were too complicated to understand, and so on. If you have somehow missed such public displays of throwing the model (and quants) under the bus, stay tuned below for examples.

A common response to these problems is to call for those models to be revamped, to add features that will cover previously unforeseen issues, and generally speaking, to make them more complex.

For a person like myself, who gets paid to “fix the model,” it’s tempting to do just that, to assume the role of the hero who is going to set everything right with a few brilliant ideas and some excellent training data.

Unfortunately, reality is staring me in the face, and it’s telling me that we don’t need more complicated models.

If I go to the trouble of fixing up a model, say by adding counterparty risk considerations, then I’m implicitly assuming the problem with the existing models is that they’re being used honestly but aren’t mathematically up to the task.

But this is far from the case – most of the really enormous failures of models are explained by people lying. Before I give three examples of “big models failing because someone is lying” phenomenon, let me add one more important thing.

Namely, if we replace okay models with more complicated models, as many people are suggesting we do, without first addressing the lying problem, it will only allow people to lie even more. This is because the complexity of a model itself is an obstacle to understanding its results, and more complex models allow more manipulation.

Example 1: Municipal Debt Models

Many municipalities are in shit tons of problems with their muni debt. This is in part because of the big banks taking advantage of them, but it’s also in part because they often lie with models.

Specifically, they know what their obligations for pensions and school systems will be in the next few years, and in order to pay for all that, they use a model which estimates how well their savings will pay off in the market, or however they’ve invested their money. But they use vastly over-exaggerated numbers in these models, because that way they can minimize the amount of money to put into the pool each year. The result is that pension pools are being systematically and vastly under-funded.

Example 2: Wealth Management

I used to work at Riskmetrics, where I saw first-hand how people lie with risk models. But that’s not the only thing I worked on. I also helped out building an analytical wealth management product. This software was sold to banks, and was used by professional “wealth managers” to help people (usually rich people, but not mega-rich people) plan for retirement.

We had a bunch of bells and whistles in the software to impress the clients – Monte Carlo simulations, fancy optimization tools, and more. But in the end, the banks and their wealth managers put in their own market assumptions when they used it. Specifically, they put in the forecast market growth for stocks, bonds, alternative investing, etc., as well as the assumed volatility of those categories and indeed the entire covariance matrix representing how correlated the market constituents are to each other.

The result is this: no matter how honest I would try to be with my modeling, I had no way of preventing the model from being misused and misleading to the clients. And it was indeed misused: wealth managers put in absolutely ridiculous assumptions of fantastic returns with vanishingly small risk.

Example 3: JP Morgan’s Whale Trade

I saved the best for last. JP Morgan’s actions around their $6.2 billion trading loss, the so-called “Whale Loss” was investigated recently by a Senate Subcommittee. This is an excerpt (page 14) from the resulting report, which is well worth reading in full:

While the bank claimed that the whale trade losses were due, in part, to a failure to have the right risk limits in place, the Subcommittee investigation showed that the five risk limits already in effect were all breached for sustained periods of time during the first quarter of 2012. Bank managers knew about the breaches, but allowed them to continue, lifted the limits, or altered the risk measures after being told that the risk results were “too conservative,” not “sensible,” or “garbage.” Previously undisclosed evidence also showed that CIO personnel deliberately tried to lower the CIO’s risk results and, as a result, lower its capital requirements, not by reducing its risky assets, but by manipulating the mathematical models used to calculate its VaR, CRM, and RWA results. Equally disturbing is evidence that the OCC was regularly informed of the risk limit breaches and was notified in advance of the CIO VaR model change projected to drop the CIO’s VaR results by 44%, yet raised no concerns at the time.

I don’t think there could be a better argument explaining why new risk limits and better VaR models won’t help JPM or any other large bank. The manipulation of existing models is what’s really going on.

Just to be clear on the models and modelers as scapegoats, even in the face of the above report, please take a look at minute 1:35:00 of the C-SPAN coverage of former CIO head Ina Drew’s testimony when she’s being grilled by Senator Carl Levin (hat tip Alan Lawhon, who also wrote about this issue here).

Ina Drew firmly shoves the quants under the bus, pretending to be surprised by the failures of the models even though, considering she’d been at JP Morgan for 30 years, she might know just a thing or two about how VaR can be manipulated. Why hasn’t Sarbanes-Oxley been used to put that woman in jail? She’s not even at JP Morgan anymore.

Stick around for a few minutes in the testimony after Levin’s done with Drew, because he’s on a roll and it’s awesome to watch.

Giving isn’t the secret

I don’t know if you read this article (h/t Radhika Sainath) on a hyperactive professor and Organizational Psychology researcher, Adam Grant, who always helps people when they ask and has a theory about giving. He claims that generous giving is the answer to getting ahead and feeling and being successful.

Well, as a “strategic giver” myself, let me tell you that giving isn’t the way to get ahead. Not as expressed by Grant, anyway*.

If you look carefully at the story, it reveals a bunch of things. Here are a few of them:

- Grant has a stay-at-home wife who deals with the kids all the time. Even so, she doesn’t seem all that psyched about how much time he devotes to helping other people (“Sometimes I tell him, ‘Adam — just say no,’ ”).

- He works all the time and misses sleep to get stuff done.

- He engages in high-profile strategic helping – he helps colleagues and students.

- Moreover, he does it in exaggerated and dramatic ways, leading to people talking about him and thanking him profusely, generally giving him attention.

- Considering that his area of research is how to get people to work hard and be more efficient through helping each other, this attention directly in line with his goal of gaining status.

- Just to be clear, he isn’t researching how to get other people to have high status like him, but rather how to get people to work harder in boring-ass jobs.

Put it all together, and you’ve got this disconnect between the way he applies “helping” to himself and to the subjects in his research.

He researches people in call centers, for example, and figures out how to get them to really believe in their work by seeing someone who benefitted from the associated scholarship program. But working harder doesn’t get them more status, it just makes them tired. The other examples in the article are similar. Actually some of them get grosser. Here’s a tasty excerpt from the article:

Jerry Davis, a management professor who taught Grant at the University of Michigan and is generally a fan of [Adam Grant]’s work, couldn’t help making a pointed critique about its inherent limits when they were on a panel together: “So you think those workers at the Apple factory in China would stop committing suicide if only we showed them someone who was incredibly happy with their iPhone?”

So what does he means by “giving” when he’s considering other people? Working really hard in a dead-end job? Kinda reminds me of this review of Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In” book, written by ex-Facebook disgruntled speech writer Kate Losse. Here’s my favorite line from that bitter essay:

For Sandberg, pregnancy must be converted into a corporate opportunity: a moment to convince a woman to commit further to her job. Human life as a competitor to work is the threat here, and it must be captured for corporate use, much in the way that Facebook treats users’ personal activities as a series of opportunities to fill out the Facebook-owned social graph.

In other words, Grant, like Sandberg, is selling us a message of working really hard with the underlying promise that it will make us successful, especially if we do it because we just love working really hard.

What?

First, it really matters what you work on and who you are helping. If you are not a strategic helper, you end up wasting your time for no good reason. How many times have we seen people who end up doing their job plus someone else’s job, without any thanks or extra money?

If you work really hard on a project which nobody cares about, nobody appreciates it. True.

And if you aren’t a political animal, able to smell out the projects and people that are worth working on extra hard and helping, then you’re pretty much out of luck.

But let’s take one step back from the terrible advice being given by Grant and Sandberg. What are their actual goals? Is it possible that they really think just by working extra hard at whatever shit corporate job we have will leave us successful and fulfilled? Are they that blind to other people’s options? Do they really know nobody in their private lives who found fulfillment by quitting their dead-end corporate job and became a poor but happy poet?

Here’s what Kate Losse says, and I think she hit the nail on the head:

Sandberg is betting that for some women, as for herself, the pursuit of corporate power is desirable, and that many women will ramp up their labor ever further in hopes that one day they, too, will be “in.” And whether or not those women make it, the companies they work for will profit by their unceasing labor.

Similarly, Grant’s personal academic success comes from getting people to work harder. His incentive is to get you to work harder, not be fulfilled. Just to be clear.

* I actually do think giving is a wonderful thing, but certainly not exclusively at work, and it’s not a secret.

Value-added model doesn’t find bad teachers, causes administrators to cheat

There’ve been a couple of articles in the past few days about teacher Value-Added Testing that have enraged me.

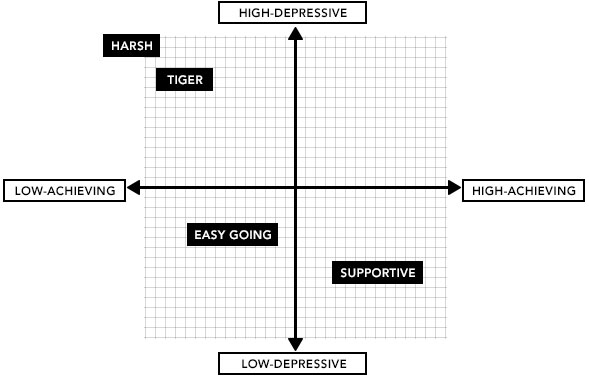

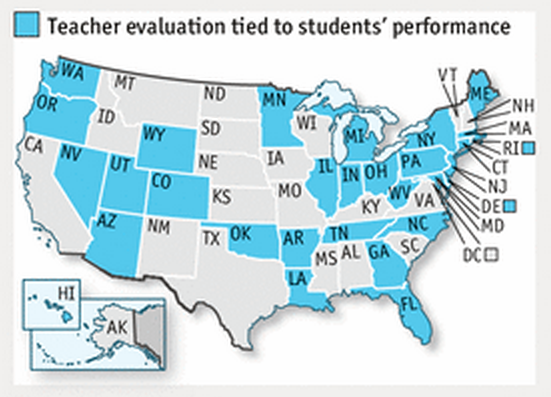

If you haven’t been paying attention, the Value-Added Model (VAM) is now being used in a majority of the states (source: the Economist):

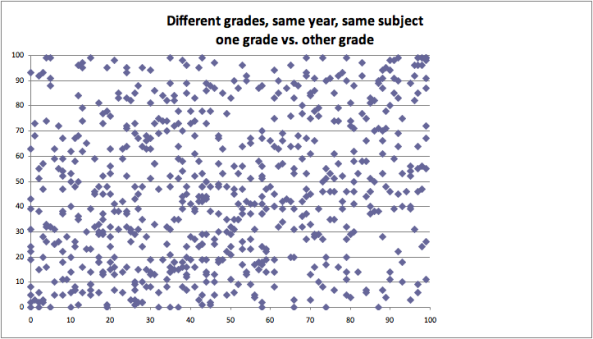

But it gives out nearly random numbers, as gleaned from looking at the same teachers with two scores (see this previous post). There’s a 24% correlation between the two numbers. Note that some people are awesome with respect to one score and complete shit on the other score:

Final thing you need to know about the model: nobody really understands how it works. It relies on error terms of an error-riddled model. It’s opaque, and no teacher can have their score explained to them in Plain English.

Now, with that background, let’s look into these articles.

First, there’s this New York Times article from yesterday, entitled “Curious Grade for Teachers: Nearly All Pass”. In this article, it describes how teachers are nowadays being judged using a (usually) 50/50 combination of classroom observations and VAM scores. This is different from the past, which was only based on classroom observations.

What they’ve found is that the percentage of teachers found “effective or better” has stayed high in spite of the new system – the numbers are all over the place but typically between 90 and 99 percent of teachers. In other words, the number of teachers that are fingered as truly terrible hasn’t gone up too much. What a fucking disaster, at least according to the NYTimes, which seems to go out of its way to make its readers understand how very much high school teachers suck.

A few things to say about this.

- Given that the VAM is nearly a random number generator, this is good news – it means they are not trusting the VAM scores blindly. Of course, it still doesn’t mean that the right teachers are getting fired, since half of the score is random.

- Another point the article mentions is that failing teachers are leaving before the reports come out. We don’t actually know how many teachers are affected by these scores.

- Anyway, what is the right number of teachers to fire each year, New York Times? And how did you choose that number? Oh wait, you quoted someone from the Brookings Institute: “It would be an unusual profession that at least 5 percent are not deemed ineffective.” Way to explain things so scientifically! It’s refreshing to know exactly how the army of McKinsey alums approach education reform.

- The overall article gives us the impression that if we were really going to do our job and “be tough on bad teachers,” then we’d weight the Value-Added Model way more. But instead we’re being pussies. Wonder what would happen if we weren’t pussies?

The second article explained just that. It also came from the New York Times (h/t Suresh Naidu), and it was a the story of a School Chief in Atlanta who took the VAM scores very very seriously.

What happened next? The teachers cheated wildly, changing the answers on their students’ tests. There was a big cover-up, lots of nasty political pressure, and a lot of good people feeling really bad, blah blah blah. But maybe we can take a step back and think about why this might have happened. Can we do that, New York Times? Maybe it had to do with the $500,000 in “performance bonuses” that the School Chief got for such awesome scores?

Let’s face it, this cheating scandal, and others like it (which may never come to light), was not hard to predict (as I explain in this post). In fact, as a predictive modeler, I’d argue that this cheating problem is the easiest thing to predict about the VAM, considering how it’s being used as an opaque mathematical weapon.

Guest Post SuperReview Part II of VI: The Occupy Handbook Part I: How We Got Here

Whatsup.

This is a review of Part I of The Occupy Handbook. Part I consists of twelve pieces ranging in quality from excellent to awful. But enough from me, in Janet Byrne’s own words:

Part 1, “How We Got Here,” takes a look at events that may be considered precursors of OWS: the stories of a brakeman in 1877 who went up against the railroads; of the four men from an all-black college in North Carolina who staged the first lunch counter sit-in of the 1960s; of the out-of-work doctor whose nationwide, bizarrely personal Townsend Club movement led to the passage of Social Security. We go back to the 1930s and the New Deal and, in Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff‘s “nutshell” version of their book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, even further.

Ms. Byrne did a bang-up job getting one Nobel Prize Winner in economics (Paul Krugman), two future Economics Nobel Prize winners (Robert Shiller, Daron Acemoglu) and two maybes (sorry Raghuram Rajan and Kenneth Rogoff) to contribute excellent essays to this section alone. Powerhouse financial journalists Gillian Tett, Michael Hilztik, John Cassidy, Bethany McLean and the prolific Michael Lewis all drop important and poignant pieces into this section. Arrogant yet angry anthropologist Arjun Appadurai writes one of the worst essays I’ve ever had the misfortune of reading and the ubiquitous Brandon Adams make his first of many mediocre appearances interviewing Robert Shiller. Clocking in at 135 pages, this is the shortest section of the book yet varies the most in quality. You can skip Professor Appadurai and Cassidy’s essays, but the rest are worth reading.

Advice from the 1 Percent: Lever Up, Drop Out by Michael Lewis

Framed as a strategy memo circulated among one-percenters, Lewis’ satirical piece written after the clearing of Zucotti Park begins with a bang.