Archive

The Neighbors

When I was a senior in high school, my parents moved house to the outskirts of Lexington, Massachusetts, from the center of town where I’d grown up. The neighborhood had a totally different feel, even though it was the same town. In particular it had a kind of prissiness that we didn’t understand or care for.

My best friend Becky ran away from home to live with my family during this year, so most of my memories of that house involve her. Our good friend Karen often visited as well; she drove her beat-up old VW van up the hill and parked it right across from our house on the street. This was totally legal, by the way, and there were plenty of people who parked on the street nearby.

Just to describe the van a bit more: it had about 5 different color paints on it, but not in any kind of artistic way. It was just old. And it had a million, possibly more than a million, memories of teenage sex hanging on to it- at some point there had even been a mattress installed in the back of the van. I remember this from earlier in high school, when the van had been owned by Karen’s older half-sister and had been parked out behind the high school.

Just in case this is getting too seedy for you, keep in mind we were the freaks and geeks of high school (J-House), we talked about D&D and always used condoms. I don’t even know why I’m saying “we” because I personally never got any action in the legendary van, but I was certainly aware of it.

So anyway, Karen would drive up the hill and park her ugly-but-legendary van there, and every time she’d do it, she’d get a nasty note on her windshield by the time she left, something along these lines:

“Please don’t part your van in front of our window. It is an eyesore. – the Neighbors”

I remember laughing hysterically with Karen and Becky the first time Karen got such a note and bringing it to my mom, who, in her characteristically nerdy way, said something about how it’s perfectly legal to park on the street and to ignore it.

What was awesome about this was how, from then on, Karen would very carefully park her van from then on right in front of the window of the Neighbors (their last name was actually “Neighbors”). Sometimes she’d pull up a bit, then pull back, then get it settled just so. And she always got the note, even though we never actually saw them leave the house. They were like magical prissy elves.

One more story about the Neighbors which is too good to resist. There was a swimming pool in the back of the house, which my mom hated with all her heart because she was in charge of the upkeep and it kept mysteriously turning green. And Becky and I were going through a back-to-nature phase, which meant we were planning to go hiking up in the White Mountains. So one day we were testing our tent out in the front yard, learning how to open and close it, and we happened to be wearing swimming suits, since we’d been swimming.

The Neighbors called my house (this is back when there were things called “telephone books” and you could find someone’s phone number without asking them) and complained to my grandma, who happened to answer the phone, and who also happened to be wearing nothing but a swimming suit, that “there are skimpily clad young ladies cavorting on the front lawn in an obscene manner.”

Now, my grandma had arthritis and couldn’t comfortably walk or stand for very long, but this phone call seemed to give her extra strength. She walked to the front door and stood there, arms crossed, looking defiantly out at the neighborhood for five minutes. After about four minutes I asked her if everything was all right and she said, “perfectly fine.”

Knitting porn

I owe you guys a post on my talk last night at Rachel Schutt’s Data Science course at Columbia (which I’ve been blogging about for the past four weeks here). Yesterday I spoke about time series, financial modeling, and ethics.

But unfortunately, right now I’m tending to my 3-year-old, who was up all night sick. While you wait I thought I’d show you some knitting porn I can’t get enough of:

A Few Words on the Soul

This is a poem by Wislawa Szymborska, h/t Catalina.

We have a soul at times.

No one’s got it non-stop,

for keeps.

Day after day,

year after year

may pass without it.

Sometimes

it will settle for awhile

only in childhood’s fears and raptures.

Sometimes only in astonishment

that we are old.

It rarely lends a hand

in uphill tasks,

like moving furniture,

or lifting luggage,

or going miles in shoes that pinch.

It usually steps out

whenever meat needs chopping

or forms have to be filled.

For every thousand conversations

it participates in one,

if even that,

since it prefers silence.

Just when our body goes from ache to pain,

it slips off-duty.

It’s picky:

it doesn’t like seeing us in crowds,

our hustling for a dubious advantage

and creaky machinations make it sick.

Joy and sorrow

aren’t two different feelings for it.

It attends us

only when the two are joined.

We can count on it

when we’re sure of nothing

and curious about everything.

Among the material objects

it favors clocks with pendulums

and mirrors, which keep on working

even when no one is looking.

It won’t say where it comes from

or when it’s taking off again,

though it’s clearly expecting such questions.

We need it

but apparently

it needs us

for some reason too.

Yesterday

I was suffering from some completely bizarre 24-hour flu yesterday, which is why I didn’t post as usual. The symptoms were weird:

What I didn’t do yesterday

- I didn’t sleep at all.

- That is to say, after my Datadive presentation shorty before noon Sunday, and after my Occupy group met Sheila Bair Sunday evening, I came home and stayed awake until I went to bed Monday night.

- So, in particular, being awake already for 24 hours by then, I didn’t write a post about whether pruning does or does not actually mitigate future disastrous events like falling trees. I owe you that post.

- I also didn’t blog about Sheila Bair. Will do soon.

- I also didn’t share my friend’s Chicago public school take on value-added testing for teachers. Stay tuned.

- Also I wanted to tell you guys about this amazing book I’m reading called Sh*tty Mom, which I didn’t do. Consider yourself told. Read immediately, even if you’re not a parent, because this will explain why your parent friends are so insane and annoying.

- I also didn’t read or write any emails, related to the fact that I was feeling like it was still about midnight for the entire day and I was wondering why people kept sending me emails in the middle of the night.

What I did yesterday

- I watched the pilot episode of Downton Abbey.

- Then I watched a few more.

- Then I finished the first season.

- Then I got my kids up, sent them or brought them to school and then came back home. Glad I did this because it meant I had to actually get dressed.

- Then I watched the second season. That’s an unbelievable amount of vegging out, an enormous investment. The kiss scene made it all worth it.

- For some reason, I also made a turkey dinner with mashed potatoes, gravy, and apple cider. No stuffing, that would have been overkill for September. Plus I couldn’t find fresh cranberries.

- Finally, and maybe it’s the turkey that did it, I felt tired, and after my 10-year-old helped me put my 3-year-old to bed, my 10-year-old then tucked me in at 7:30 last night.

I woke up feeling great! I’m back, baby!

Fair versus equal

In this multimedia presentation, Alan Honick explores the concept of fairness with archaeologist Brian Hayden. It’s entitled “The Evolution of Fairness”, and it’s published by Pacific Standard Magazine.

It’s a series of small writings and short videos which studies evidence of the emergence of inequality in the archaeological record of fishing at a place called Keatley Creek in British Columbia. While it isn’t the most convenient thing to go through, it’s worth the effort. Here are the highlights for me:

When the main concern of the people living at Keatley Creek was subsistence, their society was egalitarian – they shared everything and it wasn’t okay to hoard. Specifically, anyone found trying to game the system was ejected from society, which typically meant death.

As fishing technology improved, the average person could provide for themselves in normal times quite easily, and private ownership became acceptable and common. Those who game the system were no longer ejected, partly because the definitions were different.

At this point, Hayden suggests, people began to do things in small groups that seemed perfectly fair (“I’ll give you 20 fish loaves if you let me marry your daughter” or “Come to my feast tonight and invite me to your feast next week”) and moreover seemed like a private arrangement, until it became sufficiently widespread so that two things happened:

- The guys who didn’t have or couldn’t borrow 20 fish loaves couldn’t get married, or similarly the guys who couldn’t afford to serve a feast never entered into the feast-sharing ritual, and

- The truly rich guys would sometimes have a feast for everyone, which meant the poorer would “get something for nothing” and everyone would gain. Another way of saying this is that the poorer people would allow themselves to be coopted into the unequal system by the price of this free food. Those people who didn’t give feasts or cooperate with the free feasts were outcasts.

An interesting thing happened when Hayden goes to villages in the Mayan Highlands in Mexico and Guatemala which has similar size and social structure as the one on Keatley Creek (see the video on this page). He interviewed people about how the “rich” behaved in times of starvation. Did they take on a managerial role? Did they share and help out in bad times? This is referred to as “communitarian”.

Turns out, no, they exploited the people in the village in the hopes of having better status by the time things got better. They sold maize at exorbitant prices, took outrageous amounts of land for maize, etc. The driving force was individual self-interest.

The overall narrative describes the shifting definition of fairness as things became less and less equal, and how eventually the elite, who essentially got to define fairness, didn’t need to listen to the objections of the poor at all, because they had no power.

Sound familiar?

The author Alan Honick concludes by looking at our society and asks whether campaign finance laws, and Citizens United, is that different in effect from what we saw happening on Keatley Creek. He also points out that, because we humans are so individually obsessed with increasing our status, we can’t seem to get together to address really important issues such as global warming.

Automated call centers and superorganisms

Once upon a time there were people who worked in the insurance office and you could talk to them on the phone or even in person (annoying emphasis intentional).

Now everything is online and you need to call an automated call center to try to conduct business if there’s been an accident or they made a mistake or if you have a question which isn’t “how much do I owe the insurance company?”.

Recently my friend Becky got stuck in the penetralia of an automated call center and she likened the experience to the life of an ant and specifically to the “superorganism hypothesis” of myrmecologist E. O. Wilson (BTW, who here doesn’t love the word “myrmecologist”?). Her description:

Whether or not this is an accurate representation of their inner state, ants have long been described as having an automaton’s machine-like nature, one in which individual identity is subsumed under the totalitarian will of the collective in Borg-like, Communist wetdream fashion.

That’s how I feel when I’m lost in the labyrinthine bowels of automated customer service hell. I’m part of a network that works profitably at the superorganism level, but doesn’t serve the interests of the individual in the slightest, nor cares to nor purports to, driven as it is by the spare logic of collective efficiency.

Question: what is less human than the rigid caste societies of Army ants marching hollowly and inexorably on their prey, driven by the dictates of their genes?

Answer: only the hollowed-out computer-generated voice of the quasi-British phone operator who demands that you enter your social security number over and over again as an exercise in surrendering your will to a corporation whose power role in the financial arrangement is made ever more apparent to both parties by the dawning impossibility of ever speaking to a human at the end of the interminable and ultimately futile phone call.

Powerful analogy; I’ve tended to use the herded cows analogy myself. To entertain myself in the painful waits, I often emit audible “moos” to emphasize the forced passivity I object to. It sometimes backfires and interprets my sounds as a menu choice, though, so I’m thinking of going with the ants, who I don’t think make much noise.

A few thoughts:

- If you know you need to talk to a person eventually and that there’s no point going through all the stages, sometimes just dialing “0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0” a bunch of times will put you straight through. I usually try this straight away the first time I call. Sometimes it works, sometimes it totally fails and I have to call back. Worth a try.

- I wonder how efficient these call centers really are. I have a theory that people simply give up and pay (or default on) their incorrect bills rather than having to deal with this irredeemably opaque system.

- I also wonder what the built-up learned passivity does to us as a society. Having worked as a customer support person myself, I know that there are probably nice people at the other end of the system, and if I could only get through to them, which is a big if, they’d be super informed and helpful. But most people probably don’t think of it that way.

The country is going to hell, whaddya gonna do.

Yesterday I finished reading Chris Hayes’s book “Twilight of the Elites,” and although I enjoyed it, I have to say it was more about the elites than about their twilight.

He focused on the enormous distance between people in society, how the myth of meritocracy is widening that gap (with healthy references to Karen Ho’s book Liquidated, which I blogged about here), and how, as the entrenched elite get more and more entrenched, they get less and less competent.

But Hayes didn’t really paint a picture of how things would end, although he mentioned the Tea Party and Occupy as possible important sources of resistance, not unlike Barofsky’s recent book Bailout (which I blogged about here), in which Barofsky appealed to the righteous anger of the people to whom government is no longer accountable.

Well, I guess Hayes did add one wrinkle which surprised me. He said it would be the upper middle class, educated class that actually foments the coming revolution. Oh, and the bloggers (because the mainstream media is so captured they’re useless). So me and my friends.

His argument is that we are the ones sufficiently educated and sufficiently insiderish that we will be at the window, with our faces pressed against the glass, looking in at the true insider elites, and seeing how stupid and incompetent those guys are, and how they are rigging the system against the rest of us, and we’ll eventually explode with disgust and righteous anger and that will signal the end.

Kind of feels like that’s already happened, but maybe I’m being impatient.

Two things I really enjoyed about his book:

First, the fact that practically everyone thinks they’re an underdog and has fought tooth and nail to succeed in this world. Absolutely true, including the guys I worked with in finance. I think the phrase he used is “people born on third base think they hit a triple”.

Second, he does a really good job describing the never-can-be-too-rich culture of our country; his example of going to Davos is an excellent one and brings that concept to life perfectly.

It’s enough to get you kind of depressed overall, though. If we are to believe this book’s thesis, our entrenched elite and dysfunctional political structure and economic system are doomed to fail at some future moment, and the best we can hope for is a moment where the hypocrisy collapses in on itself. What is there to look forward to exactly?

I asked that of a friend of mine, and how it was getting me down. His advice to me was to own it more. To make the coming apocalypse an event, kind of like the 4th of July or a vacation, that you plan for and enjoy thinking about.

He said plenty of people do this, it’s in fact a huge industry of doom and gloom. The country is going to hell, whaddya gonna do, he said, might as well have some fun with it.

What? Who are these doom and gloom people? Start here, where Dmitry Orlov compares the preparedness of the US to the former USSR for the coming inevitable apocalypse. He calls this the “Collapse Gap”.

It’s got some great points (although he can’t both say that lawlessness ensues and people take what they want, and also say that people behind in their mortgages will be homeless) and it’s really funny as well, in a completely cynical, Russian way of course. My favorite lines:

One area in which I cannot discern any Collapse Gap is national politics. The ideologies may be different, but the blind adherence to them couldn’t be more similar.

It is certainly more fun to watch two Capitalist parties go at each other than just having the one Communist party to vote for. The things they fight over in public are generally symbolic little tokens of social policy, chosen for ease of public posturing. The Communist party offered just one bitter pill. The two Capitalist parties offer a choice of two placebos. The latest innovation is the photo finish election, where each party buys 50% of the vote, and the result is pulled out of statistical noise, like a rabbit out of a hat.

What makes us fat

I recently finished a book that made rethink being fat, and the cause of the worldwide “obesity epidemic”. Rethink in a good way.

Namely, it suggested the following possibility. What if, rather than getting fat because we are overeating, we overeat because we are getting fat? Another way of thinking about this is that there’s something going on that makes us both store fat away and overeat – that they are both symptomatic of some other problem.

In particular, this would imply that the fact of being fat is not a moral weakness, not a mere lack of willpower. Since I long ago dismissed the willpower hypothesis myself (I don’t seem to have trouble with other aspects of my life which require planning and willpower, why do I have so much trouble with this even though I’ve seriously tried?), this idea comes as something of a “duh” moment, but a welcome one.

To get in the appropriate mindset for this idea, think for a moment about all of the studies you hear about feeding animals such as rats, rabbits, monkeys, pigs, etc. different diets, and noting that sometimes the diet makes them super fat, and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes the animals are bred to have a genetic defect, or a pituitary or other gland is removed, and that has an effect on their fatness as well. In other words, there’s some kind of internal chemical thing going on with these animals which causes this condition.

Bottomline: we never accuse the fat mice of lacking will power.

So what is this thing that causes overeating and fat accumulation? The theory given in the book is as follows.

Fat cells are active little chemical warehouses which accept fat molecules and allow fat molecules to leave in two separate (but not unrelated) processes. Rather than thinking of fat as being stored there until the moment it is needed, instead think of the flow of fat molecules both into and out of each fat cell as two constant processes, so it’s actually better to consider the rate of those flows, the inward rate and the outward rate.

Suppose the outward rate of the fat molecules is somehow suppressed compared to the inward rate. So the fat molecules are being allowed into the fat cells just fine but they aren’t leaving the fat cells easily. What would happen?

In the short term, this would happen: lacking the appropriate amount of energy, the overall system would feel internally starved and get super hungry and quickly cause the animal to overeat to compensate for the lack of available energy.

In the longer term, the number of fat cells (or maybe the size of the average fat cell) would increase until the energy flow is sufficient to satisfy the internal needs of the system. In other words, the animal would gain a certain amount of weight (in the form of fat) and stay there, once the internal equilibrium is reached. This jives with the fact that people seem to have a certain “set point” of weight, including overweight. Indeed the amount of fat an animal has in equilibrium allows us to estimate how suppressed the outward flow of energy is.

What causes this suppressed outward rate? The book suggests that it’s elevated insulin. And what causes chronic elevated insulin? The book suggests that the main culprit is refined carbohydrates.

In particular, the author, Gary Taubes, suggests that by avoiding refined carbohydrates such as flour, sugar, and corn syrup, we can bring our insulin levels down to reasonable levels and the outward rate of fat from fat cells will no longer be suppressed.

Not everyone reacts in exactly the same way to refined carbs (i.e. not all insulin responses are identical) and scaled definitely matters, so eating 180 pounds of sugar a year is worse than 90 pounds a year, according to the theory. Moreover, things get progressively worse over time and it takes about 20 years of carb overloading to have such effects.

It’s easier said than done to avoid such foods as an individual living in our culture (nothing at Starbucks, nothing at a newsstand, almost nothing at a bodega), but one thing I like about this theory is that it actually explains the obesity epidemic pretty well: as the author points out, massively scaled refined carbohydrates have only been consumed at such rates for a short while, and the correlations with weight gain are pretty high.

Moreover, and I know this from personally avoiding most carbs for the past 6 months (which I started doing for another, related reason – I hadn’t read the book yet!). I’ve lost weight easily, and I haven’t ever been hungry, even compared to what I used to experience when I wasn’t dieting at all. According to the theory, my fat cells are releasing fat easily because my insulin levels are low, which means I don’t have internal starvation, which in turn explains my complete lack of hunger.

Also in the book: he claims we don’t actually know eating saturated fat raises cholesterol, nor that high cholesterol causes heart disease except when it’s super high, but then again it also seems to be bad to have super low cholesterol. I gotta hand it to this guy, he’s not afraid of going against conventional wisdom, at the risk of being ridiculed, which he most definitely has been.

But that doesn’t make me dismiss his theories, because I’m pretty sure he’s right when he says epidemiology is fraught with politics and bad selection bias.

It’s certainly an interesting book, and who knows, he may be right on some or all scores. On the other hand, maybe it doesn’t matter that much – not many people want to or are willing to avoid carbs, and maybe it’s not environmentally sustainable, although I don’t eat more meat than I used to, just more salad.

We are now ruling out the idea that people don’t exercise enough as the cause for being fat, and as we’ve attempted to follow the advice of the so-called experts, everyone seems to just get fatter all the time. As far as I’m concerned, all conventional bets are off.

Update on organic food

So I’m back from some town in North Ontario (please watch this video to get an idea). I spent four days on a tiny little island on Lake Huron with my family and some wonderful friends, swimming, boating, picnicking, and reading the Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan whenever I could.

It was a really beautiful place but really far away, especially since my husband jumped gleefully into the water from a high rock with his glasses on so I had to drive all the way back without help. But what I wanted to mention to you is that, happily, I managed to finish the whole book – a victory considering the distractions.

I was told to read the book by a bunch of people who read my previous post on organic food and why I don’t totally get it: see the post here and be sure to read the comments.

One thing I have to give Pollan, he has written a book that lots of people read. I took notes on his approach and style because I want to write a book myself. And it’s not that I read statistics on the book sales – I know people read the book because, even though I hadn’t, lots of facts and passages were eerily familiar to me, which means people I know have quoted the book to me. That’s serious!

In other words, there’s been feedback from this book to the culture and how we think about organic food vs. industrial farming. I can’t very well argue that I already knew most of the stuff in the book, even though I did, because I probably only know it because he wrote the book on it and it’s become part of our cultural understanding.

I terms of the content, first, I’ll complain, then I’ll compliment.

Complaint #1: the guy is a major food snob (one might even say douche). He spends like four months putting together a single “hunting and gathering” meal with the help of his friends the Chez Panisse chefs. It’s kind of like a “lives of the rich and famous” episode in that section of the book, which is to say voyeuristic, painfully smug, and self-absorbed. It’s hard to find this guy wise when he’s being so precious.

Complaint #2: a related issue, which is that he never does the math on whether a given lifestyle is actually accessible for the average person. He mentions that the locally grown food is more expensive, but he also suggests that poor people now spend less of their income on food than they used to, implying that maybe they have extra cash on hand to buy local free-range chickens, not to mention that they’d need the time and a car and gas to drive to the local farms to buy this stuff (which somehow doesn’t seem to figure into his carbon footprint calculation of that lifestyle). I don’t think there’s all that much extra time and money on people’s hands these days, considering how many people are now living on food stamps (I will grant that he wrote this book before the credit crisis so he didn’t anticipate that).

Complaint #3: he doesn’t actually give a suggestion for what to do about this to the average person. In the end this book creates a way for well-to-do people to feel smug about their food choices but doesn’t forge a path otherwise, besides a vague idea that not eating processed food would be good. I know I’m asking a lot, but specific and achievable suggestions would have been nice. Here’s where my readers can say I missed something – please comment!

Compliment #1: he really educates the reader on how much the government farm subsidies distort the market, especially for corn, and how the real winners are the huge businesses like ConAgra and Monsanto, not the farmers themselves.

Compliment #2: he also explains the nastiness of processed food and large-scale cow, pig, and chicken farms. Yuck.

Compliment #3: My favorite part is that he describes the underlying model of the food industry as overly simplistic. He points out that, by just focusing on the chemicals like nitrogen and carbon in the soil, we have ignored all sorts of other important things that are also important to a thriving ecosystem. So, he explains, simply adding nitrogen to the soil in the form of fertilizer doesn’t actually solve the problem of growing things quickly. Well, it does do that, but it introduces other problems like pollution.

This is a general problem with models: they almost by definition simplify the world, but if they are successful, they get hugely scaled, and then the things they ignore, and the problems that arise from that ignorance, are amplified. There’s a feedback loop filled with increasingly devastating externalities. In the case of farming, the externalities take the form of pollution, unsustainable use of petrochemicals, sick cows and chickens, and nasty food-like items made from corn by-products.

Another example is teacher value-added models: the model is bad, it is becoming massively scaled, and the externalities are potentially disastrous (teaching to the test, the best teachers leaving the system, enormous amount of time and money spent on the test industry, etc.).

But that begs the question, what should we do about it? Should we well-to-do people object to the existence of the model and send our kids to the private schools where the teachers aren’t subject to that model? Or should we acknowledge it exists, it isn’t going away, and it needs to be improved?

It’s a similar question for the food system and the farming model: do we save ourselves and our family, because we can, or do we confront the industry and force them to improve their models?

I say we do both! Let’s not ignore our obligation to agitate for better farming practices for the enormous industry that already exists and isn’t going away. I don’t think the appropriate way to behave is to hole up with your immediate family and make sure your kids are eating wholesome food. That’s too small and insular! It’s important to think of ways to fight back against the system itself if we believe it’s corrupt and is ruining our environment.

For me that means being part of Occupy, joining movements and organization fighting against lobbyist power (here’s one that fights against BigFood lobbyists), and broadly educating people about statistics and mathematical modeling so that modeling flaws and externalities are understood, discussed, and minimized.

Away for a week – will miss you

Like all good New Yorkers, I’m going away for a week’s vacation in August. I’ll be on a tiny island on Lake Ontario with no internet connection. I’ll miss you guys! See you in a week!

Subway etiquette: applying makeup on the 1 train

I’m a huge fan of public transportation, mostly subways. I used the New York City subway system on average three times a day, especially now that I’m not working. And I like to observe people on the subway, and the sometimes strange etiquette that you see there.

Specifically, I am interested in how people break what I call the two cardinal rules of public transportation:

- No eye contact or conversations with people you didn’t get on the subway with. Exceptions when, as described here, somebody incredibly smelly or incredibly sick leaves, or the subway gets irretrievably stuck in the tunnel.

- No doing anything weird, even by yourself, to attract undue attention. Things like reading, playing games on your phone, and pretending to sleep are OK, things like eating smelly food or humming or whistling: not okay.

Most people who break these rules I get – they are trying to get you to give them money, or they’re slightly to totally insane, or both. Fair enough, that’s part of the fabric of life in a big city.

But there’s one category of people I just don’t get, namely the women who put outlandish amounts of makeup on while sitting on the subway.

I’m not talking about a dab of lipstick, which seems fine and comparable to chapstick or something. I’m talking about the women who come with a complete set of foundation, eyeliners, mascara, the works. They sit there peering intensely into their tiny mirrors, creating a new persona, utterly absorbed in their transformation, and completely oblivious to the mesmerizing effect that it has on everyone.

Or maybe not, maybe it’s performance art – sometimes I think so. Or perhaps they are actually insane in a small way.

Because otherwise it seems like a contradiction in terms to me. From my perspective, wearing that much makeup usually indicates a willingness to conform at the highest level (these are usually young women, so the idea that they are actually in need of makeup to cover sun spots or wrinkles does not apply), but then the willingness to break the second cardinal rule of subway riding seems to be in direct conflict with that religion of conformism.

For example, whenever I see one of these 25-year-old foundation appliers, I’m wondering, who are you becoming? From whom are you hiding your real face? If it’s your coworkers, what if one of them is on this train right now? Then they’d see the real you in the before shot, at the beginning of your ride. Wouldn’t that defeat the purpose of the makeup? Isn’t that too large a risk to take for you?

Since I don’t wear makeup myself, I’m also wondering if I’m just not understanding the goal of that much makeup. Maybe if I understood more deeply why women wear these masks, I’d also understand why they’re willing to apply them in front of a crowd of strangers.

Gangnam Style

Best, most absurd video ever, and impossible not to feel cheered up after you watch it. From Gawker, hat tip Johan.

The douche burger, and putting a ruler to the dick.

I have been pretty hardcore and serious for a few weeks, and today I want to lighten it up for a change.

Douchery

First, I want everyone to read this article about a New York City food truck that sells douche burgers. From the article:

For just $666 you can purchase a foie gras-stuffed Kobe patty covered in Gruyere cheese that’s been melted with champagne steam and topped with lobster, truffles, caviar, and a BBQ sauce made with Kopi Luwak coffee beans that have been pooped out by some sort of animal called the Asian palm civet. The whole thing is then served in a gold-leaf wrapper.

Two things I like about this article, first that it’s hilarious and over the top satire, which is always excellent, and second that the world is picking up on my idea of calling people douches when they get really into esoteric stuff.

If you don’t believe me, read my previous post My friend the coffee douche. It’s one of my favorites.

Putting a ruler to the dick

Next, speaking of using language in a funny but pointed way, are you with me that “opening the kimono” is an offensive and sexist phrase? Well, how about we replace it with a better, more offensive, and more sexist phrase that’s even more fun to say, namely “putting a ruler to the dick”??

This was my friend Laura Strausfeld’s idea, and I love it. It’s gonna be the buzzword (buzzphrase) of the year, we just know it.

Here’s how it works in context:

guy A: “So do you think you’ll invest in those guys? They seemed really excited about that new technique they’ve developed!”

guy B: “I don’t know. They talked a big game, but until I can put a ruler to the dick I’m not putting my money there.”

Tu-du leest bork bork

What with finishing a job up at the end of June, and then immediately going off to three weeks of math camp, I’ve put off lots of stuff around the house. My to-do list, just on household stuff alone, is getting kind of intimidating:

- Call Richard to get air conditioners installed

- Call insurance company about crazy bills

- Send care package to junior staff

- Deposit paycheck in bank

- Replace broken window shades

- Replace lightbulbs in bedroom

- Find babysitter for this Friday

- Find babysitter for early September

But I’ve figured out a way to avoid being too down about it. Namely, I just put it through the Swedish Chef Translator (if you can’t remember the Swedish Chef, check this out), and I’m good (borks added):

- Cell Reecherd tu get eur cundeeshuners instelled bork bork

- Cell insoorunce-a cumpuny ebuoot crezy beells bork bork

- Send cere-a peckege-a tu jooneeur steffff bork bork

- Depuseet peycheck in bunk bork bork

- Replece-a brukee veendoo shedes bork bork

- Replece-a leeghtboolbs in bedruum bork bork

- Feend bebyseetter fur thees Freedey bork bork

- Feend bebyseetter fur ierly September bork bork

Also available in Pig Latin to make me feel sneaky:

- allCay ichardRay otay etgay airway onditionerscay installedway

- allCay insuranceway ompanycay aboutway azycray illsbay

- endSay arecay ackagepay otay uniorjay affstay

- epositDay aycheckpay inway ankbay

- eplaceRay okenbray indowway adesshay

- eplaceRay ightbulbslay inway edroombay

- indFay abysitterbay orfay isthay idayFray

- indFay abysitterbay orfay earlyway eptemberSay

Mixing colors: pigment vs. light

Today we will address another topic in a list of “things I’m kind of ashamed I don’t understand considering I am a professional scientist of sorts” (please make suggestions!).

Why is it that when you mix light blue (cyan) and yellow paint you get green paint, but when you mix cyan and yellow light you get white light?

Unlike with yesterday’s analemma post, where I couldn’t find a satisfactory write-up on another blog, today’s blog is actually pretty nicely explained and beautifully illustrated here. I will crib their illustrations and summarize the explanations but it’s really out-and-out plagiarism for the moment.

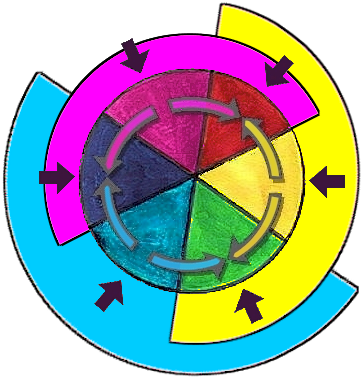

First, you’ve got the so-called “hue wheel” (which sounds more sophisticated than “color wheel”, don’t you agree?):

This is illustrating the following. There are three basic pigments: yellow, cyan and magenta. There are three basic colors of light, namely green, blue, and red. And if you mix the fundamental pigments pair-wise (as in, you get paints and mix them) you get the fundamental colors of lights.

And vice versa as well, although this time you’re mixing as in splicing them together but keeping them separate, like we use pixels on our screen. This means, specifically, that you can combine green and red to get yellow. That’s majorly unbelievable until you see this miraculous picture, also from this webpage:

See how that works? I just can’t get over this picture. The little piece of yellow on the left is just stripes of green and red. Really incredible. The purple I get because it’s blue and red just like it’s supposed to be.

So, why?

The first thing to understand is that this isn’t just a relationship between us and the object we are looking at. It is instead a three-part relationship between us (or more specifically, our eyes), the object, and the sun (or some other source of light, but it’s more traditional in explanations like this to use fundamental, macho objects of nature like the sun).

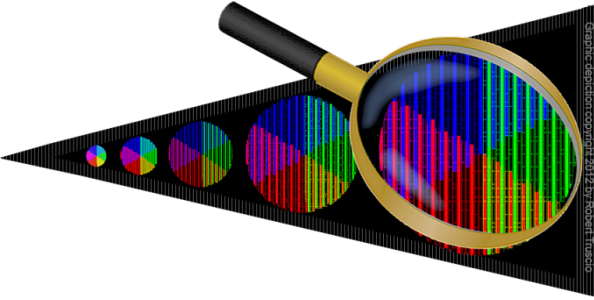

Nothing can happen without a source of light. Which begs the question, what is light anyway? Again a picture stolen from here:

The prism separates the white light into various wavelengths, where red is at 700 nanometers and violet at 400 nanometers. More on the visible spectrum here. Note that the hidden difficulty here is why a prism does this, which is explained here.

So when an apple looks red to us, we have to imagine white light from the sun hitting that apple, and the key is that the skin of the apple is absorbing everything except the red light:

That thing on top is the sun, and the thing on bottom is your eyeball. The point is the red part of the light is reflected off the apple skin into your eye. And even though white light from the sun is the whole spectrum, we are denoting it when just the fundamental three colors of light because other colors can be made from those. And this can be corroborated by looking at your computer screen with a magnifying glass, where you will see that the white background is actually made up of little pixels of green, red, and blue.

That thing on top is the sun, and the thing on bottom is your eyeball. The point is the red part of the light is reflected off the apple skin into your eye. And even though white light from the sun is the whole spectrum, we are denoting it when just the fundamental three colors of light because other colors can be made from those. And this can be corroborated by looking at your computer screen with a magnifying glass, where you will see that the white background is actually made up of little pixels of green, red, and blue.

By the way, we are again sidestepping the actual hard part here, namely why some surfaces such as apple skins reflect some colors like red. I have no idea. But I don’t feel as guilty about not understanding that.

Finally, back to the first question, of why cyan and yellow paint make green whereas cyan and yellow light make white. Turns out the light one is actually easier, since our second picture above shows us that yellow light is actually a mix of red and green, and when you add cyan, you now have all three fundamental colors of light, which gives us white light.

If you have cyan paint, then it is reflecting blue and green light, so absorbing red light. If you have yellow paint then that’s a material which is reflecting both green and red, so absorbing blue. For some weird reason (a third moment of stuffing things under the rug), the mixture of the paint is additive on absorbing things, so absorbs both blue and red, leaving only green reflected.

In the end we get a kind of mini De Morgan’s Law for color.

I’ve convinced myself that, modulo the following three questions I understand this explanation:

- How does a prism separate white light into the colors really?

- How do different surfaces decide which lights to reflect and which to absorb? And a related question from Aaron, why do colors fade when they’ve been in the sun?

- Why is “absorbing light” an additive procedure when you mix materials? I feel like if I understood 2 then I’d get 3 for free.

Analemma

Today is a day of new things, since I finished my last day at my job yesterday and I’m going to math camp tomorrow. It’s exciting, and I’m going to kick off this first day of new things with a silly but fun thing I recently learned about the earth and the sun.

Some people know this already, but some people don’t, so sorry in advance if I bore you, but it’s super interesting the first time you think about it.

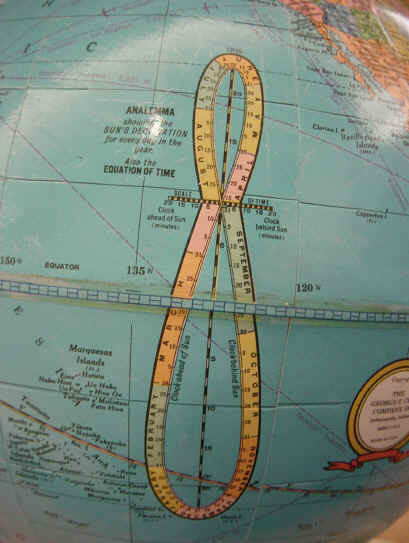

Namely, have you ever noticed, on your globe, a weird figure eight looking thing?

Nobody could be blamed for their curiosity, because there are so many important looking notches and then of course there’s the phrase “Equation of Time” next to it looking both pompous and intriguing. What is that thing??

After a few moments of contemplation, you’ve probably noticed there are months indicated, and since it’s a closed loop it’s probably describing something that is periodic with a one year period. Plus there are two axes, the vertical axis looks to be measured in degrees and the horizontal is called the “scale of time”.

Whenever I see north/south degrees I think of the earth’s tilt, and when I see something about time, it makes me think about how we measure time, which is vague to me, but probably has something to do with the sun, and orbiting around the sun, and spinning while we do it, again at a tilt. And if I want to be expansive at a time like this I’ll remember that the (pretty much circular) orbit of the earth lies on some plane where the sun also lives.

Now as soon as I get to this point I get nervous. What is time, anyway? How do we know what time it is? What with time zones, and daylight savings time, we’ve definitely corrupted the idea of it being noon when the sun is at its highest in the sky or anything as definitive as that.

So let’s imagine there are no time zones, that you are just in some specific place on the earth. You never move from that spot, because you’re afraid of switching time zones or what have you, and you’re’r wondering what time it is. If someone comes by and tells you it’s daylight savings time and to reset your clock, you tell them to go to hell because you’re thinking.

From this vantage point it’s definitely hard to know when it’s midnight, but you can for sure detect three things: sunrise, high noon, and sunset. I say “high noon” to mean as high as it gets, because obviously if you’re way north or way south of the equator the sun will never be totally overhead, as I noticed from living in the northeast my whole life.

But wait, even if you’re at the equator, the sun won’t be directly overhead most of the time. This goes back to the tilt of the earth, and if you imagine your left fist is the sun and your right fist is an enormous earth, and you tilt your right fist and stick your finger out and make it move around the sun (with your finger staying stuck out in the same direction because the tilt of the earth doesn’t change). As you imagine the earth spinning, you realize a point on the equator is only going to be directly in line to see the sun straight overhead about twice a year, and even then only if things line up perfectly.

Similarly you can see that, for any point between the equator and some limit latitude, you see the sun straight overhead twice a year – at the limit it’s once.

Going back to the point of view of a single person looking for high noon at a single place, we can see the height of the sun when it reaches its apex, from her perspective, is going to move around every day, possibly passing overhead depending on her latitude.

This is starting to sound like a periodic loop with a one-year period – and it makes me think we understand the x-axis. But what’s with the y-axis, the so-called “scale of time”?

Turns out it’s a definition thing, namely about what time noon is. Sometimes it takes the earth less time to spin around once than other times, and so the definition of “noon” can either be what we’ve said, namely “high noon,” or when the sun is at its highest in the sky, or you could use a clock, which has, by construction, averaged out all the days of the years so they all have the same length (pretty boring!). The difference between high noon and clock noon is called the equation of time.

By the way, back when we used sundials, we just let different days have different lengths. And when they first made clocks, they adjusted the clocks to the equation of time to agree with sundials (see this). It was only after people got picky about all their days having the same length that we moved away from sundial time. So it’s really just a cultural choice.

But why are some days shorter than others in terms of high noon? There are actually two reasons.

The first one, quaintly named “The Effect of Obliquity,” is again about the tilt. Imagine yourself sitting at the equator, looking up at the sun. It might be better to think of your position as fixed and the sun as going around the earth. And for that matter, we will assume the orbit of the earth around the sun is a perfect circle for this part.

Then what is being held constant is the spin of the tilted earth, or in other words the speed of the sun in the sky from the point of view of an observer on earth (this point is actually not obvious, but I do think it’s true because we’ve assumed a fixed tilt and a perfectly circular orbit. I will leave this to another post).

You can decompose this motion, this velocity vector, at a given moment, into two perpendicular parts: the part going in the direction of the equator (so the direction of some ideal sun if there were no tilt to the earth) and the part going up or down, i.e. in a right angle to the equator. Since we already know the sun doesn’t stay the same height all year, we know there has to be some non-zero part to the second part of this vector.

But since we also know the total vector has constant length, that means that the first vector, in the direction of the equator, is also not constant. Which means the length of the days actually varies throughout the year. The extent to which it does vary is approximated by a sin curve (see here)

The second reason for a varying length of a day, also beautifully named “The Effect of Orbital Eccentricity,” is that we don’t actually have a circular orbit around the sun- it’s an ellipse, and the sun is one of the two foci of the ellipse.

The thing about the earth being on an elliptical orbit is that it goes faster when it’s near the focus, which also causes it to spin more, due to the Conservation of Angular Momentum, which also makes an ice skater spin faster when her legs and arms are close to her body. Update (thanks Aaron!): no, it doesn’t cause it to spin more, although that somehow made sense to me. It turns out it just traverses a larger amount of angle with respect to the sun that we would “expect” because it’s moving faster. Since it turns as it moves faster, the day is shorter than you’d expect (this only works because of the way the earth spins – it’s counterclockwise if you’re looking down at the plane on which the earth is orbiting the sun clockwise). We therefore have faster days when we are closer to the sun.

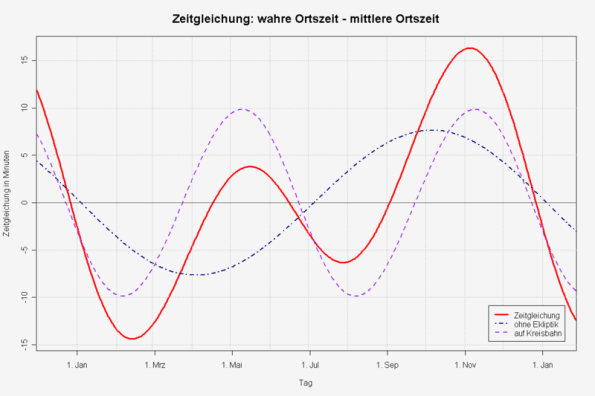

When you add up these two effect, both approximated by sin curves, you get a weird function.

This is the “x-axis” of the analemma.

You can take a picture of the analemma by shooting a picture of the sun every day at noon, like these guys in the Ukraine did.

And by the way, you can use stuff about the analemma to figure out when sunrise and sunset will be, and why on the longest day of the year it’s not necessarily the day of the earliest sunrise and latest sunset.

And also by the way, there are lots of old things written about this stuff (see here for example) and there’s an awesome CassioPeia Project video (here uploaded on YouTube) explaining how all of this stuff varies over long periods of time.

Coding is like being in a band

I asked my friend Nikolai last week what I should learn if I want to be a really awesome data scientist (since I’m an alpha female I’m sure I phrased it more like, how can I be even more awesome than I already am?).

Being a engineer, Nik gave me the most obvious advice possible: become an engineer.

So this past weekend I’ve looked in to learning Scala, which is the language he and I agreed on as the most useful for large-scale machine learning, both because it’s designed to be scalable and because the guys at Twitter are open sourcing tons of new stuff all the time.

That begs the question, though, to what extent can I become an engineer by reading books about languages in my spare time? According to Nik, real coding is an experience you can’t do alone. It’s more like joining a band. So I need to read my books, and I need to practice on my computer, but I won’t really qualify as an engineer until I’ve coded within a group of engineers working on a product.

Similarly, a person can get really good at an instrument by themselves, they can learn to play the electric guitar, they can perfect the solos of Jimi Hendrix, but when it comes down to it they have to do it in conjunction with other people. This typically means adding lots of process they wouldn’t normally have to think about or care about, like making sure the key is agreed upon, as well as the tempo, as well as deciding who gets to solo when (i.e. sharing the show-offy parts). Not to mention the song list. Oh, and then there’s tuning up at the beginning, choosing a band name, and getting gigs.

It’s a similar thing for coders, and I’ve seen it working with development teams. When they bring in someone new, they have to merge their existing culture with the ideas and habits of the new person. This means explaining how unit tests and code reviews are done, how work gets divided and played, how people work together, and of course how success gets rewarded. Moreover, like musicians, coders tend to have reputations and egos corresponding to their skills and talents which, like a good band, a development team wants to nurture, without letting itself become a pure vehicle to it.

Which means that when you hire a superstar coder (and yes the word seems to be superstar- great coders can do the job of multiple mediocre coders), you tend to listen more carefully to their ideas on how to do things, and that includes how to change the system entirely and try something new, or switch languages etc. I imagine that bands who get to work with Eric Clapton would be the same way.

I’ve been in bands, usually playing banjo, as well as in chamber music groups back when I played piano, so this analogy works great for me. And it makes me more interested in the engineering thing rather than less: my experience was that, although my individual contribution was slightly less in a band setting, the product of the group was something I was always very proud of, and was impossible to accomplish alone.

Now I don’t want you to think I’ve done no coding at all. As a quant, I learned python, which I used extensively at D.E. Shaw and ever since, and some Matlab, as well as SQL and Pig more recently. But the stuff I’ve done is essentially prototyping models. That is, I work alone, playing with data through a script, until I’m happy with the overall model. Since I’m alone I don’t have to follow any process at all, and trust me you can tell by looking at my scripts. Actually I wrote some unit tests for the first time in python, and it was fun. Kind of like solving a Sudoku puzzle.

The part I don’t think works about the coding/ band analogy is that I don’t think coders have quite as good a time as bands. Where are the back-stage groupies? Where are the first two parts of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll? I think coding groups have their work cut out for them if they really want to play on that analogy.

Saturday morning reading

I’m feeling deliciously lazy today, with one more week left of my current job and one more week of hazy New York weather before I head up to math camp for three weeks (woohoo!). I’m trying to figure out what to do with my life after that, and suggestions are very welcome! Bonus for ideas on how to use modeling techniques to help people rather than to exploit them.

In the meantime, please join me in some light reading:

1) Read this (hat tip Kurt Schrader). Seriously, it’s incredibly snarky and funny and right on – a gawker’s view on the New York Times Style Section and its systematic approach of torturing its readers. My favorite line:

I want to take this sentence, drag it out into the backyard, and beat it to death with a shovel.

2) How are bee hives like too-big-to-fail banks? Turns out, in fewer ways than you think. Read more to understand a beekeeper’s perspective on risk (hat tip Eugene Stern). A nugget:

Take, for example, their approach toward the “too-big-to-fail” risk our financial sector famously took on. Honeybees have a failsafe preventive for that. It’s: “Don’t get too big.” Hives grow through successive divestures or spin-offs: They swarm. When a colony gets too large, it becomes operationally unwieldy and grossly inefficient and the hive splits. Eventually, risk is spread across many hives and revenue sources in contrast to relying on one big, vulnerable “super-hive” for sustenance.

3) As we already knew, people with bad credit scores don’t really have access to all this amazing lending at amazing rates, as the Fed now admits and as I suggested in this post, “A low Fed rate: what does it means for the 99%?”. I think the next step is a data dive into credit scoring histograms (say, aggregate FICO scores for all Americans) over the past 20 years, compared to corresponding credit card offers – I want to see what kind of deals average people can expect to get on loans. If you know how to get this data, please tell me!

4) One of my readers was kind enough to leave a link to this article on why incompetent people think they’re awesome. I’m sharing it with you guys but I reserve the right to write a post on this as well. Specifically, I’m thinking of writing a meta-piece about why, when people read about incompetent people thinking they’re awesome, they somehow always smugly conclude that those pathetic fools should get a clue and realize this article is about them.

Germany’s risk

My friend Nathan recently sent me this Credit Writedowns article on the markets in German risk. There’s basically a single, interesting observation in the article, namely that 5-year bond yields are going down while credit default (CDS) spreads are going up.

When I was working in risk, we’d use both the bond market prices and the CDS market prices to infer the risk of default of a debt issuer – mostly we thought about companies, but we also generalized to countries (although mostly not in Europe!).

For example with bonds, we would split up the yield (how much the bond pays) into two pieces. Namely, you’d get some money back simply because you have to wait for the money, so you’re kind of being compensated for inflation, and then the other part of the money is your compensation for taking on the risk that it might not be paid back at all. This second part is the default risk, and we’d measure default risk of a company like GM in the U.S., for example, by comparing U.S. bond yields to GM yields, the assumption being that there’s no default risk for the U.S. at all. Note this same calculation was typical in lots of countries, but especially the U.S. and Germany, which were considered the two least risky issuers in the world.

With the CDS market, it was a bit more complicated in terms of math but the same idea was underneath – CDS is kind of like an insurance on bonds, although you don’t need to buy the underlying bonds to buy the insurance (something like buying fire insurance on a house you don’t own). The amount you’d have to pay would go up if the perceived risk of default of the issuer went up, all other things being equal.

And that’s what I want to talk about now- in the case of Germany, are all other things equal? I’ve got a short list of things that might be coming into play here besides the risk of a German default.

- Counterparty risk – whereas you only have to worry about Germany defaulting on German bonds, you actually have to worry about whomever wrote the CDS when you buy a CDS. Remember AIG? They went down because they wrote lots of CDS they couldn’t possibly pay out on, and the U.S. taxpayer paid all their bills. But that may not happen again. The counterparty risk is real, especially considering the state of banks in Europe right now.

- People might be losing faith in the CDS market. There’s a group of people who call themselves ISDA and who decide when the issuer of the debt has “defaulted”, triggering the payment of the CDS. But when Greece took a haircut on their debt, it took ISDA a long time to decide it constituted a default. If I’m a would-be CDS buyer, I think hard about whether CDS is a proper hedge for my German bonds (or whatever).

- As the writer of the article mentioned, even though it looks like there’s an “arbitrage opportunity,” people aren’t piling into the trade. Part of this may be because it’s a five year trade and nobody thinks that far ahead when they’re afraid of the next 12 months, which is I think what the author was saying.

- There are rules for some funds about what they are allowed to invest in, and bonds are deemed more elemental and therefore safe than CDSs, for good reason. Another possibility for the German bond/ CDS discrepancy is that certain funds need exposure to highly rated bonds, so German bonds or U.S. bonds, and they can’t substitute writing CDSs for that long exposure.

- Finally, in the formula for how much big a CDS spread is compared to the price, there’s an assumption about how much of a “haircut” the debt owner would have to take on their bond – but this isn’t clear from the outset, it’s determined (as it was in Greece) through a long, drawn-out, political process. If the market thinks this number is changing the spreads on CDS could be moving without the perceived default risk moving.

My followership problem

David Brooks wrote an interesting and provocative column recently in the New York Times about leadership and followership, claiming our country has forgotten how to follow. First he talks about how we dismiss leaders, focusing only on the victims:

We live in a culture that finds it easier to assign moral status to victims of power than to those who wield power. Most of the stories we tell ourselves are about victims who have endured oppression, racism and cruelty.

Then there is our fervent devotion to equality, to the notion that all people are equal and deserve equal recognition and respect. It’s hard in this frame of mind to define and celebrate greatness, to hold up others who are immeasurably superior to ourselves.

I have to admit, I agree with him here. It’s hard for me to swallow the phrase, “immeasurably superior to ourselves” when I think about the role models we have today in politics and elsewhere. I think it’s smart that he’s keeping this stuff abstract, because any given example would seem kind of embarrassing.

He then goes on to make what I think is a great point:

But the main problem is our inability to think properly about how power should be used to bind and build. Legitimate power is built on a series of paradoxes: that leaders have to wield power while knowing they are corrupted by it; that great leaders are superior to their followers while also being of them; that the higher they rise, the more they feel like instruments in larger designs. The Lincoln and Jefferson memorials are about how to navigate those paradoxes.

This idea of legitimacy of power is key. The truth is, the last time I felt myself in the presence of legitimate power was when Obama was sworn in. Ever since then I’ve been pretty much despairing, although there have been moments of relief and hope, like when Occupy started. But overall, yes, I have become a major skeptic of authority.

But I’d argue, nobody wants to feel this way. We all want there to be legitimate authority, we want to stop worrying about the economy, or whatever, and get to work and think about nothing more complicated than our personal careers, or our kids, or our haircuts, knowing that there are honest and reasonable stewards doing their job in the background. But the environment is not conducive to such blissful ignorance right now. Not in finance, not in economics, and not in government.

I’m pretty sure it’s not our attitudes here that are the problem, although they may take some time to adjust if things spontaneously improved. I think it’s the system itself, combined with modernity.

The system has become too dysfunctional for leaders to lead well. Obama has not impressed, but I’d also have to admit he hasn’t been given that many opportunities to. There’s a reason people are hating on politicians these days, and when they again fail to come to agreement on the debt ceiling it’s not going to be getting any better.

Modernity has played its part too. One of the reasons it’s harder to glorify people nowadays is that we simply know too much about them. It’s kind of in the “everybody poops” category – and that’s not going away.

I think we need a new way of appreciating just authority, if and when it comes up (i.e. if we can somehow improve our dysfunctional system). Namely, we need to appreciate people are flawed and sometimes greedy or mean, but mostly trying their best, and set up systems that don’t tempt them to be downright corrupt. Then we need to trust just as much in our systems as the leaders we set up in those systems, and see if it can work.