Archive

I wish I knew now what I’ll know then

Yesterday I read this New York Times article which explains the so-called “end of history illusion,” a fancy way of saying that as we acknowledge having changed a lot in the past, we project more of the same into the future.

I guess this is supposed to mean we always see the present moment as the end of history. From the article:

“Middle-aged people — like me — often look back on our teenage selves with some mixture of amusement and chagrin,” said one of the authors, Daniel T. Gilbert, a psychologist at Harvard. “What we never seem to realize is that our future selves will look back and think the very same thing about us. At every age we think we’re having the last laugh, and at every age we’re wrong.”

For the record I thought my teenage self was pretty awesome, and it was the moment in my life where I actually lived as best I could avoiding hypocrisy. I never laugh at my teenage self, and I’m always baffled that other people do – think of everything we had to understand and deal with all at once! But back to the end of history.

Scientists explain the phenomenon by suggesting it’s good for our egos to think we are currently perfectly evolved and won’t need to modify anything in our beliefs. Another possibility they come up with: we are too lazy to do better than this, and it’s easier to remember the past than it is to think hard about the future.

Here’s another explanation that I came up with: we have no idea what the future holds, nor whether we will become more or less conservative, more or less healthy, or more or less irritable, etc., so in expectation we will be exactly the same as we are now. Note that’s not the same as saying we actually will be the same, it’s just that we don’t know which direction we’ll move.

In other words, we are doing something different when we look into the future than when we look into the past, and the honest best guess of our future selves may well be our current selves.

After all, we don’t know what random events will occur in the future (like getting hit by a car and breaking our leg, say) that will effect us, and the best we can go is our current plans for ourselves.

Even so, it’s interesting to think about how I’ve changed over my lifetime and continue the trend into the future. If I do that, I evoke something that is clearly not an extrapolation of my current self.

In particular, I can project that I will be very different in 10 years, more patient, more joyful, doing god knows what for a living (if I’m not totally broke), even more opinionated than I am now, and much much wiser about how to raise teenage sons. Come to think of it, I can’t wait!

Suggested New Year’s resolution: start a blog

I was thinking the other day how much I’ve gotten out of writing this blog. I’m incredibly grateful for it, and I want you to consider starting a blog too. Let’s go through the pros and cons:

Pros

- A blog forces you to articulate your thoughts rather than having vague feelings about issues.

- This means you get past things that are bothering you.

- You also get much more comfortable with writing, because you’re doing it rather than thinking about doing it.

- If your friends read your blog you get to hear what they think.

- If other people read your blog you get to hear what they think too. You learn a lot that way.

- Your previously vague feelings and half-baked ideas are not only formulated, but much better thought out than before, what with all the feedback. You’ll find yourself changing your mind or at least updating and modifying lots of opinions.

- You also get to make new friends through people who read your blog (this is my favorite part).

- Over time, instead of having random vague thoughts about things that bug you, you almost feel like you have a theory about the things that bug you (this could be a “con” if you start feeling all bent out of shape because the world is going to hell).

Cons

- People often think what you’re saying is dumb and they don’t resist telling you (you could think of this as a “pro” if you enjoy growing a thicker skin, which I do).

- Once you say something dumb, it’s there for all time, in your handwriting, and you’ve gone on record saying dumb things (that’s okay too if you don’t mind being dumb).

- It takes a pretty serious commitment to write a blog, since you have to think of things to say that might interest people (thing you should never say on a blog: “Sorry it’s been so long since I wrote a post!”).

- Even when you’re right, and you’ve articulated something well, people can always dismiss what you’ve said by claiming it can’t be important since it’s just a blog.

Advice if you’ve decided to go ahead and start a blog

- Set aside time for your blog every day. My time is usually 6-7am, before the kids wake up.

- Keep notes for yourself on bloggy subjects. I write a one-line gmail to myself with the subject “blog ideas” and in the morning I search for that phrase and I’m presented with a bunch of cool ideas.

- For example I might write something like, “Can I pay people to not wear moustaches?” and I leave a link if appropriate.

- I try to switch up the subject of the blog so I don’t get bored. This may keep my readers from getting bored but don’t get too worried about them because it’s distracting.

- My imagined audience is almost always a friend who would forgive me if I messed something up. It’s a friendly conversation.

- Often I write about something I’ve found myself explaining or complaining about a bunch of times in the past few days.

- Anonymous negative comments happen, and are often written by jerks. Try to not take them personally.

- Try to accept criticism if it’s helpful and ignore it if it’s hurtful. And don’t hesitate to delete hurtful comments. If that jerk wants a platform, he or she can start his or her own goddamn blog.

- Never feel guilty towards your blog. It’s inanimate. If you start feeling guilty then think about how to make it more playful. Take a few days off and wait until you start missing your blog, which will happen, if you’re anything like me.

Consumer segmentation taken to the extreme

I’m up in Western Massachusetts with the family, hidden off in a hotel with a pool and a nearby yarn superstore. My blogging may be spotty for the next few days but rest assured I haven’t forgotten about mathbabe (or Aunt Pythia).

I have just enough time this morning to pose a thought experiment. It’s in three steps. First, read this Reuters article which ends with:

Imagine if Starbucks knew my order as I was pulling into the parking lot, and it was ready the second I walked in. Or better yet, if a barista could automatically run it out to my car the exact second I pulled up. I may not pay more for that everyday, but I sure as hell would if I were late to a meeting with a screaming baby in the car. A lot more. Imagine if my neighborhood restaurants knew my local, big-tipping self was the one who wanted a reservation at 8 pm, not just an anonymous user on OpenTable. They might find some room. And odds are, I’d tip much bigger to make sure I got the preferential treatment the next time. This is why Uber’s surge pricing is genius when it’s not gouging victims of a natural disaster. There are select times when I’ll pay double for a cab. Simply allowing me to do so makes everyone happy.

In a world where the computer knows where we are and who we are and can seamlessly charge us, the world might get more expensive. But it could also get a whole lot less annoying. ”This is what big data means to me,” Rosensweig says.

Second, think about just how not “everyone” is happy. It’s a pet peeve of mine that people who like their personal business plan consistently insist that everybody wins, when clearly there are often people (usually invisible) who are definitely losing. In this case the losers are people whose online personas don’t correlate (in a given model) with big tips. Should those people not be able to reserve a table at a restaurant now? How is that model going to work?

And now I’ve gotten into the third step. It used to be true that if you went to a restaurant enough, the chef and the waitstaff would get to know you and might even keep a table open for you. It was old-school personalization.

What if that really did start to happen at every restaurant and store automatically, based on your online persona? On the one hand, how weird would that be, and on the other hand how quickly would we all get used to it? And what would that mean for understanding each other’s perspectives?

MOOCs and calculus

I’ve really enjoyed the discussion on my post from yesterday about MOOCs and how I predict they are going to affect the education world. I could be wrong, of course, but I think this stuff is super interesting to think about.

One thing I thought about since writing the post yesterday, in terms of math departments, is that I used to urge people involved in math departments to be attentive to their calculus teaching.

The threat, as I saw it then, was this: if math departments are passive and boring and non-reactive about how they teach calculus, then other departments which need calculus for their majors would pick up the slack and we’d see calculus taught in economics, physics, and engineering departments.

The reason math departments should care about this is that calculus is the bread and butter of math departments – math departments in other countries who have lost calculus to other departments are very small. If you only need to teach math majors, it doesn’t require that many people to do that.

But now I don’t even bother saying this, because the threat from MOOCs is much bigger and is going to have a more profound effect, and moreover there’s nothing math departments can do to stop it. Well, they can bury their head in the sand but I don’t recommend it.

Once there’s a really good calculus sequence out there, why would departments continue to teach the old fashioned way? Once there’s a fantastic calculus-for-physics MOOC, or calculus-for-economics MOOC available, one would hope that math departments would admit they can’t do better.

Instead of the old-fashioned calculus approach they’d figure out a way to incorporate the MOOC and supplement it by forming study groups and leading sections on the material. This would require a totally different set-up, and probably fewer mathematicians.

Another thing. I think I’ve identified a few separate issues in the discussion that it makes sense to highlight. There are four things (at least) that are all rolled together in our current college and university experience:

- learning itself,

- credentialing,

- research, and

- socializing

So, MOOCs directly address learning but clearly want to control something about credentialing too, which I think won’t necessarily work. They also affect research because the role of professor as learning instructor will change. They give us nothing in terms of socializing.

But as commenters have pointed out, socializing students is a huge part of the college experience, and may be even more important than credentialing. Or another way of saying that is people look at your resume not so much to know what you know but to know how you’ve been socialized.

It makes me wonder how we will address the “socializing” part of education in the future. And it also makes me wonder where research will be in 100 years.

MOOC is here to stay, professors will have to find another job

I find myself every other day in a conversation with people about the massive online open course (MOOC) movement.

People often want to complain about the quality of this education substitute. They say that students won’t get the one-on-one interaction between the professor and student that is required to really learn. They complain that we won’t know if someone really knows something if they only took a MOOC or two.

First of all, this isn’t going away, nor should it: it’s many people’s only opportunity to learn this stuff. It’s not like MIT has plans to open 4,000 campuses across the world. It’s really awesome that rural villagers (with internet access) all over the world can now take MIT classes anyway through edX.

Second, if we’re going to put this new kind of education under the microscope, let’s put the current system under the microscope too. Many of the people fretting about the quality of MOOC education are themselves products of super elite universities, and probably don’t know what the average student’s experience actually is. Turns out not everyone gets a whole lot of attention from their professors.

Even at elite institutions, there are plenty of masters programs which are treated as money machines for the university and where the quality and attention of the teaching is a secondary concern. If certain students decide to forgo the thousands of dollars and learn the stuff just as well online, then that would be a good thing (for them at least).

Some things I think are inevitable:

- Educational institutions will increasingly need to show they add value beyond free MOOC experiences. This will be an enormous market force for all but the most elite universities.

- Instead of seeing where you went to school, potential employers will directly test knowledge of candidates. This will mean weird things like you never actually have to learn a foreign language or study Shakespeare to get a job, but it will be good for the democratization of education in general.

- Professors will become increasingly scarce as the role of the professor is decreased.

- One-on-one time with masters of a subject will become increasingly rare and expensive. Only truly elite students will have the mythological education experience.

Costco visit

Yesterday I was in a bit of a funk.

I decided to try to get out and do something new, and since my neighbors were going to Costco, which I’d never been to (or maybe I had once but I couldn’t remember and it would have been at least 13 years ago), I invited myself to go with them. The change would do me good, I thought.

Here’s the thing about Costco which you probably already know if you shop there: it’s a rush, like taking a narcotic. I am sure that their data scientists have spent many computing hours munging through many terabytes of shopping behavior to perfect this effect [Update: an article has just appeared in the New York Times explaining this very thing].

For example, I’m on a budget, and I was planning to go for the sociological experience of it, not to buy anything. After all, I’ve already gotten my groceries for the week, and bought reasonable presents for the kids for Christmas. Nothing outrageous. So I was feeling pretty safe.

But then I got there, and I immediately came across things I didn’t know I needed until I saw them. The most ridiculous and startling version of this was my tupperware experience.

Tupperware is an essential tool in a house with three kids, because if you do the math you’ve got 15 school lunches to make per week. That’s not something you can scrounge up carelessly. So what you do is save plastic Chinese takeout containers and fill them up after dinners with things like pasta and chicken bits. Ready to go in the morning.

But when I came across the gorgeous 30-, no 42-, no 75-piece rainbow-colored tupperware kits that actually stack together beautifully, I instantaneously realized my hitherto scheme was laughably ridiculous and that I must own gorgeous tupperware right now.

This happened to me with a rainbow-colored knife set too, but I managed to hold myself back because, I argued, I already owned knives. I am not sure why that reasoning failed with the tupperware.

In fact I immediately filled up a cart with various (rainbow-colored) things I had no idea I needed until I got there ($50 for a cashmere sweater!?), and then I started wandering around the food area.

This is when my narcotic experience started to wear off. I think it was around the 6-pound block of mozzarella that I started to say to myself, wait, do I really want 6 pounds of mozzarella? I mean, it’s a great price, but won’t that take up half my fridge?

Then I started putting stuff back. It was amazingly easy to part with that stuff once the narcotic wore off. I was in deep withdrawal by the time we left the store. Paying in cash for the few items I did buy also helped.

My conclusions:

- I totally get why people own lots of stuff they don’t need.

- I’m sure people can get addicted to that narcotic shopping rush.

- We should consider treating Costco as a dealer in controlled substances.

- I have ugly tupperware and that’s okay.

How do we quantitatively foster leadership?

I was really impressed with yesterday’s Tedx Women at Barnard event yesterday, organized by Nathalie Molina, who organizes the Athena Mastermind group I’m in at Barnard. I went to the morning talks to see my friend and co-author Rachel Schutt‘s presentation and then came home to spend the rest of the day with my kids, but they other three I saw were also interesting and food for thought.

Unfortunately the videos won’t be available for a month or so, and I plan to blog again when they are for content, but I wanted to discuss an issue that came up during the Q&A session, namely:

what we choose to quantify and why that matters, especially to women.

This may sound abstract but it isn’t. Here’s what I mean. The talks were centered around the following 10 themes:

- Inspiration: Motivate, and nurture talented people and build collaborative teams

- Advocacy: Speak up for yourself and on behalf of others

- Communication: Listen actively; speak persuasively and with authority

- Vision: Develop strategies, make decisions and act with purpose

- Leverage: Optimize your networks, technology, and financing to meet strategic goals; engage mentors and sponsors

- Entrepreneurial Spirit: Be innovative, imaginative, persistent, and open to change

- Ambition: Own your power, expertise and value

- Courage: Experiment and take bold, strategic risks

- Negotiation: Bridge differences and find solutions that work effectively for all parties

- Resilience: Bounce back and learn from adversity and failure

The speakers were extraordinary and embodied their themes brilliantly. So Rachel spoke about advocating for humanity through working with data, and this amazing woman named Christa Bell spoke about inspiration, and so on. Again, the actual content is for another time, but you get the point.

A high school teacher was there with five of her female students. She spoke eloquently of how important and inspiring it was that these girls saw these talk. She explained that, at their small-town school, there’s intense pressure to do well on standardized tests and other quantifiable measures of success, but that there’s essentially no time in their normal day to focus on developing the above attributes.

Ironic, considering that you don’t get to be a “success” without ambition and courage, communication and vision, or really any of the themes.

In other words, we have these latent properties that we really care about and are essential to someone’s success, but we don’t know how to measure them so we instead measure stuff that’s easy to measure, and reward people based on those scores.

By the way, I’m not saying we don’t also need to be good at content, and tasks, which are easier to measure. I’m just saying that, by focusing on content and tasks, and rewarding people good at that, we’re not developing people to be more courageous, or more resilient, or especially be better advocates of others.

And that’s where the women part comes in. Women, especially young women, are sensitive to the expectations of the culture. If they are getting scored on X, they tend to focus on getting good at X. That’s not a bad thing, because they usually get really good at X, but we have to understand the consequences of it. We have to choose our X’s well.

I’d love to see a system evolve wherein young women (and men) are trained to be resilient and are rewarded for that just as they’re trained to do well on the SAT’s and rewarded for that. How do you train people to be courageous? I’m sure it can be done. How crazy would it be to see a world where advocating for others is directly encouraged?

Let’s try to do this, and hell let’s quantify it too, since that desire, to quantify everything, is not going away. Instead of giving up because important things are hard to quantify, let’s just figure out a way to quantify them. After all, people didn’t think their musical tastes could be quantified 15 years ago but now there’s Pandora.

Update: Ok to quantify this, but the resulting data should not be sold or publicly available. I don’t want our sons’ and daughters’ “resilience scores” to be part of their online personas for everyone to see.

It’s Pro-American to be Anti-Christmas

This is a guest post by Becky Jaffe.

I know what you’re thinking: Don’t Christmas and America go together like Santa and smoking?

Why, of course they do! Just ask Saint Nickotine, patron saint of profit. This Lucky Strike advertisement is an early introduction to Santa the corporate shill, the seasonal cash cow whose avuncular mug endorses everything from Coca-Cola to Siri to yes, even competing brands of cigarettes like Pall Mall. Sorry Lucky Strike, Santa’s a bit of a sellout.

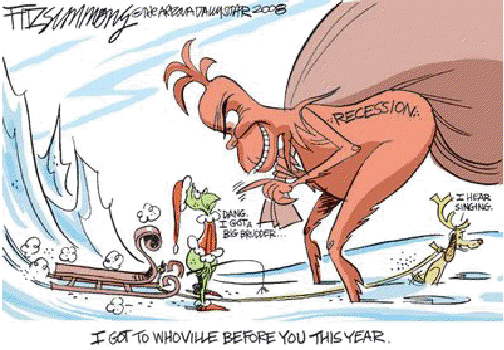

Nearly a century after these advertisements were published, the secular trinity of Santa, consumerism and America has all but supplanted the holy trinity the holiday was purportedly created to commemorate. I’ll let Santa the Spokesmodel be the cheerful bearer of bad news:

Christmas and consumerism have been boxed up, gift-wrapped and tied with a red-white-and-blue ribbon. In this guest post I’ll unwrap this package and explain why I, for one, am not buying it.

____________________

Yesterday was Thanksgiving, followed inexorably by Black Friday; one day we’re collectively meditating on gratitude, the next we’re jockeying for position in line to buy a wall-mounted 51” plasma HDTV. Some would argue that’s quintessentially American. As social critic and artist Andy Warhol wryly observed, “Shopping is more American than thinking.”

Such a dour view may accurately describe post WW II America, but not the larger trends nor longer traditions of our nation’s history. Although we may have become profligate of late, we were at the outset a frugal people; consumerism and America need not be inextricably linked in our collective imagination if we take a longer view. Long before there was George Bush telling us the road to recovery was to have faith in the American economy, there was Henry David Thoreau, who spoke to a faith in a simpler economy:

The Simple Living experiment he undertook and chronicled in his classic Walden was guided by values shared in common by many of the communities who sought refuge in the American colonies at the outset of our nation: the Mennonites, the Quakers, and the Shakers. These groups comprise not only a great name for a punk band, but also our country’s temperamental and ethical ancestry. The contemporary relationship between consumerism and Christmas is decidedly un-American, according to our nation’s founders. And what could be more American than the Amish? Or the secular version thereof: The Simplicity Collective.

Being anti-Christmas™ is as uniquely American as Thoreau, who summed up his anti-consumer credo succinctly: “Men have become the tools of their tools.” If he were alive today, I have no doubt that curmudgeonly minimalist would be marching with Occupy Wall Street instead of queuing with the tools on Occupy Mall Street.

Being anti-Christmas™ is as American as Mark Twain, who wrote, “The approach of Christmas brings harrassment and dread to many excellent people. They have to buy a cart-load of presents, and they never know what to buy to hit the various tastes; they put in three weeks of hard and anxious work, and when Christmas morning comes they are so dissatisfied with the result, and so disappointed that they want to sit down and cry. Then they give thanks that Christmas comes but once a year.” (From Following the Equator)

Being anti-Christmas™ is as American as “Oklahoma’s favorite son,” Will Rogers, 1920’s social commentator who made the acerbic observation, “Too many people spend money they haven’t earned, to buy things they don’t want, to impress people they don’t like.”

He may have been referring to presents like this, which are just, well, goyish:

Being anti-Christmas is as American as Robert Frost, recipient of four Pulitzer prizes in poetry, who had this to say in a Christmas Circular Letter:

He asked if I would sell my Christmas trees;

My woods—the young fir balsams like a place

Where houses all are churches and have spires.

I hadn’t thought of them as Christmas Trees.

I doubt if I was tempted for a moment

To sell them off their feet to go in cars

And leave the slope behind the house all bare,

Where the sun shines now no warmer than the moon.

I’d hate to have them know it if I was.

Yet more I’d hate to hold my trees except

As others hold theirs or refuse for them,

Beyond the time of profitable growth,

The trial by market everything must come to.

We inherit from these American thinkers a unique intellectual legacy that might make us pause at the commercialism that has come to consume us. To put it in other words:

- John Porcellino’s Thoreau at Walden: $18

- Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: $5.95

- Mary Oliver’s American Primitive: $9.99

- The Life and Letters of John Muir: $12.99

- Transcendentalist Intellectual Legacy: Priceless.

The intellectual and spiritual founders of our country caution us to value our long-term natural resources over short-term consumptive titillation. Unheeding their wisdom, last year on Black Friday American consumers spent $11.4 billion, more than the annual Gross Domestic Product of 73 nations.

And American intellectual legacy aside, isn’t that a good thing? Doesn’t Christmas spending stimulate our stagnant economy and speed our recovery from the recession? If you believe organizations like Made in America, it’s our patriotic duty to spend money over the holidays. The exhortation from their website reads, “If each of us spent just $64 on American made goods during our holiday shopping, the result would be 200,000 new jobs. Now we want to know, are you in?”

That depends once again on whether or not we take the long view. Christmas spending might create a few temporary, low-wage, part-time jobs without benefits of the kind described in Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By In America, but it’s not likely to create lasting economic health, especially if we fail to consider the long-term environmental and social costs of our short-term consumer spending sprees. The answer to Made in America’s question depends on the validity of the economic model we use to assess their spurious claim, as Mathbabe has argued time and again in this blog. The logic of infinite growth as an unequivocal net good is the same logic that underlies such flawed economic models as the Gross National Product (GNP) and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

These myopic measures fail to take into account the value of the natural resources from which our consumer products are manufactured. In this accounting system, when an old-growth forest is clearcut to make way for a Best Buy parking lot, that’s counted as an unequivocal economic boon since the economic value of the lost trees/habitat is not considered as a debit. Feminist economist and former New Zealand parliamentarian Marilyn Waring explains the idea accessibly in this documentary: Who’s Counting? Marilyn Waring on Sex, Lies, and Global Economics.

If we were to adopt a model that factors in the lost value of nonrenewable natural resources, such as the proposed Green National Product, we might skip the stampede at Walmart and go for a walk in the woods instead to stimulate the economy.

Other critics of these standard models for measuring economic health point out that they overvalue quantity of production and, by failing to take into account such basic measures of economic health as wealth distribution, undervalue quality of life. And the growing gap in income inequality is a trend that we cannot afford to overlook as we consider the best options for economic recovery. According to this New York Times article, “Income inequality has soared to the highest levels since the Great Depression, and the recession has done little to reverse the trend, with the top 1 percent of earners taking 93 percent of the income gains in the first full year of the recovery.”

For the majority of Americans who are still struggling to make ends meet, the Black Friday imperative to BUY! means racking up more credit card debt. (As American poet ee cummings quipped,” “I’m living so far beyond my income that we may almost be said to be living apart.”) The specter of Christmas spending is particularly ominous this season, during a recession, after a national wave of foreclosures has left Americans with insecure housing, exorbitant rents, and our beleaguered Santa with fewer chimneys to squeeze into.

Some proposed alternatives to the GDP and GNP that factor in income distribution are the Human Progress Index, the Genuine Progress Indicator, and yes, even a proposed Gross National Happiness.

A dose of happiness could be just the antidote to the dread many Americans feel at the prospect of another hectic holiday season. As economist Paul Heyne put it, “The gap in our economy is between what we have and what we think we ought to have – and that is a moral problem, not an economic one.”

____________________

Mind you, I’m not anti-Christmas, just anti-Christmas™. I’ve been referring thus far to the secular rites of the latter, but practicing Christians for whom the former is a meaningful spiritual meditation might equally take offense at its runaway commercialization, which the historical Jesus would decidedly not have endorsed.

I hate to pull the Bible card, but, seriously, what part of Ecclesiastes don’t you understand?

Photo by Becky Jaffe. http://www.beckyjaffe.com

Better is an handful with quietness, than both the hands full with travail and vexation of spirit. – Ecclesiastes 4:6

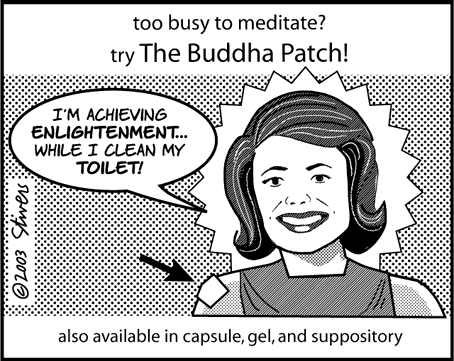

Just imagine if Buddhism were hijacked by greed in the same fashion.

After all,

Right?

Or is it axial tilt?

Whether you’re a practicing Christian, a Born-Again Pagan celebrating the Winter Solstice (“Mithras is the Reason for the Season”), or a fundamentalist atheist (“You know it’s a myth! This season, celebrate reason.”), we all have reason to be concerned about the corporatization of our cultural rituals.

The meaning of Christmas has gotten lost in translation:

So this year, let’s give Santa a much-needed smoke break, pour him a glass of Kwanzaa Juice, and consider these alternatives for a change:

1. Presence, not presents. Skip the spending binge (and maybe even another questionable Christmas tradition, the drinking binge), and give the gift of time to the people you love. I’m talking luxurious swaths of time: unstructured time, unproductive time, time wasted exquisitely together.

I’m talking about turning off the television in preparation for Screen-Free Week 2013, and going for a slow walk in nature, which can create more positive family connection than the harried shopping trip. And if Richard Louv’s thesis about Nature Deficit Disorder is merited, it may be healthier for your child to take a walk in the woods than to camp out in front of the X-Box you can’t afford anyway.

Whether you’re choosing to spend the holidays with your family of origin or your family of choice, playing a game together is a great way to reconnect. How about kibitzing over this new card game 52 Shades of Greed? It’s quite the conversation starter. And what better soundtrack for a card game than Sweet Honey in the Rock’s musical musings on Greed? Or Tracy Chapman’s Mountains of Things.

Or how about seeing a show together? You can take the whole family to see Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping at the Highline Ballroom in New York this Sunday, November 25th. He’s on a “mission to save Christmas from the Shopocalypse.” From the makers of the film What Would Jesus Buy?

2. Give a group gift. There is a lot of talk about family values, but how well do we know each other’s values? One way to find out is to pool our giving together and decide as a group who the beneficiaries should be. You might elect to skip Black Friday and Cyber Monday and make a donation instead to Giving Tuesday’s Hurricane Sandy relief efforts. Other organizations worth considering:

3. Think outside the box. If you’re looking for alternatives to the gift-giving economy, how about bartering? Freecycle is a grassroots organization that puts a tourniquet on the flow of luxury goods destined for the landfill by creating local voluntary swap networks.

Or how about giving the gift of debt relief? Check out the Rolling Jubilee, a “bailout for the people by the people.”

4. Give the Buddhist gift: Nothing!

Buy Nothing Do Something is the slogan of an organization proposing an alternative to Black Friday: On Brave Friday, we “choose family over frenzy.” One contributor to the project shared this family tradition: “We have a “Five Hands” gift giving policy. We can exchange items that are HANDmade (by us), HAND-me-down and secondHAND. We can choose to gift a helping HAND (donations to charities). Lastly and my favorite, we can gift a HAND-in-hand, which is a dedication of time spent with one another. (Think date night or a day at the museum as a family.)”

Adbusters magazine sponsors an annual boycott of consumerism in England called Buy Nothing Day.

5. Invent your own holiday. Americans pride ourselves on our penchant for innovation. We amalgamate and synthesize novelty out of eclectic sources. Although we often talk about “traditional values,” we’re on the whole much less tradition-bound than say, the Serbs, who collectively recall several thousand years of history as relevant to the modern instant. We tend to abandon tradition when it is incovenient (e.g. marriage), which is perhaps why we harken back to its fantasy status in such a treacly manner. Making stuff up is what we do well as a nation. Isn’t “DIY Christmas” a no-brainer? Happy Christmahannukwanzaka, y’all!

6. Keep it weird. Several of you wrote with these suggestions for Black Friday street theater:

“Someone said go for a hike in a park, not the Wal*Mart parking lot. But why not the Wal*Mart parking lot? With all your hiking gear and everything.”

“I’d love for 5-6 of us to sit at Union Square in front of Macy’s and sit and meditate. Perhaps passer-bys will take a notice and ponder. Anyone in? Friday 2-3 hours.”

Few pranksters have been so elaborate in their anti-corporate antics as the Yes Men. You may get inspired to come up with some political theater of your own after watching the documentary The Yes Men: The True Story of the End of the World Trade Organization.

____________________

However we choose to celebrate the holidays in this relativist pluralistic era, whatever our preferred religious and/or cultural December-based holiday celebration may be, we can disentangle our rituals from obligatory consumerism.

I’m not suggesting this is an easy task. Our consumer habits are wrapped up with our identities as social critic Alain de Botton observes: “We need objects to remind us of the commitments we’ve made. That carpet from Morocco reminds us of the impulsive, freedom-loving side of ourselves we’re in danger of losing touch with. Beautiful furniture gives us something to live up to. All designed objects are propaganda for a way of life.”

This year, let’s skip the propaganda.

We can choose to

Yes, we can.

Happy Solstice, everyone!

(If only I had a Celestron CPC 1100 Telescope with Nikon D700 DSLR adapter to admire the Solstice skies….)

A primer on time wasting

Hello, Aaron here.

Cathy asked me to write a post about wasting time. But I never got around to it.

Just kidding. I’m actually doing it.

Things move fast here in New York City, but where the hell is everyone going anyway?

When I was writing my dissertation, I lived on the west coast and Cathy lived on the east coast. I used to get up around 7 every morning. She was very pregnant (for the first time), and I was very stressed out. We talked on the phone every morning, and we got in the habit of doing the New York Times crossword puzzle. Mind you, this was before it was online – she actually had a newspaper, with ink and everything, and she read me the clues over the phone and we did the puzzle together. It helped get me going in the morning, and it warmed me up for dissertation writing.

After a long time of not doing crossword puzzles, I’ve taken it up again in recent years. Sometimes Cathy and I do it together, online, using the app where two people can solve it at the same time. [NYT, if you’re listening, the new version is much worse than the old! Gotta fix up the interfacing.] Sometimes I do it myself. Sometimes, like today, it’s Thanksgiving, and it’s a real treat to do the puzzle with Cathy in person. But one way or another, I do it just about every day.

At one point, early in the current phase of my habit, I got stuck and I wanted to cheat. I looked for the answers online, since I couldn’t just wait until the next day. I came across this blog, which I call rexword for short.

I got addicted. As happens so frequently with the internets, I discovered an entire community of people who are both really into something mildly obscure (read: nerdy) and also actually insightful, funny, and interesting (read: nerdy).

I’ve learned a lot about puzzling from rexword. I like to tell my students they have to learn how to get “behind” what I write on the chalkboard, to see it before it’s being written or as it’s being written as if they were doing it themselves, the way a musician hears music or the way anyone does anything at an expert level. Rex’s blog took me behind the crossword puzzle for the first time. I’m nowhere near as good at it as he is, or as many of his readers seem to be, but seeing it from the other side is a lot of fun. I appreciate puzzles in a completely different way now: I no longer just try to complete it (which is still a challenge a lot of the time, e.g. most Saturdays), but I look it over and imagine how it might have been different or better or whatever. Then, especially if I think there’s something especially notable about it, I go to the blog expecting some amusing discussion.

Usually I find it. In fact, usually I find amusing discussion and insights about way more things than I would ever notice myself about the puzzle. I also find hilarious things like this:

We just did last Sunday’s puzzle, and at the end we noticed that the completed puzzle contained all of the following: g-spot, tits, ass, cock. Once upon a time I might not have thought much of this (or noticed) but now my reaction was, “I bet there’s something funny about this on the blog.” I was sure this would be amply noted and wittily de- and re-constructed. In fact, it barely got a mention, although predictably, several commenters picked up the slack.

Anyway, I’ve got this particular addiction under control – I no longer read the blog every day, but as I said, when there’s something notable or funny I usually check it out and sometimes comment myself, if no one else seems to have noticed whatever I found.

What is the point of all this? In case you forgot, Cathy asked me to write about wasting time. I think she made this request because of the relish with which I tread the fine line between being super nerdy about something and just wasting time (don’t get me started about the BCS….).

Today, I am especially thankful to be alive and in such a luxurious condition that I can waste time doing crossword puzzles, and then reading blogs about doing crossword puzzles, and then writing blogs about reading blogs about doing crossword puzzles.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone.

Black Friday resistance plan

The hype around Black Friday is building. It’s reaching its annual fever pitch. Let’s compare it to something much less important to americans like “global warming”, shall we? Here we go:

Note how, as time passes, we become more interested in Black Friday and less interested in global warming.

How do you resist, if not the day itself, the next few weeks of crazy consumerism that is relentlessly plied? Lots of great ideas were posted here, when I first wrote about this. There will be more coming soon.

In the meantime, here’s one suggestion I have, which I use all the time to avoid over-buying stuff and which this Jane Brody article on hoarding reminded me of.

Mathbabe’s Black Friday Resistance plan, step 1:

Go through your closets and just look at all the stuff you already have. Go through your kids’ closets and shelves and books and toychests to catalog their possessions. Count how many appliances you own, in your kitchen alone.

Be amazed that anyone could ever own that much stuff, and think about what we really need to survive, and indeed, what we really need to be content.

In case you need more, here’s an optional step 2. Think about the Little House on the Prairie series, and how Laura made a doll out of scraps of cloth left over from the dresses, and how once a year when Pa sold his crop they’d have penny candy and it would be a huge treat. For Christmas one year, Laura got an orange. Compared to that we binge on consumerism on a daily basis and we’ve become enured to its effects.

Now, I’m not a huge fan of going back to those roots entirely. After all, during The Long Winter, as I’m sure you recall and which was very closely based on her real experience, Mary went blind from hunger and Carrie was permanently affected. If it hadn’t been for Almonzo coming to their rescue with food for the whole town, many might have died. Now that was a man.

I think we need a bit more insurance than that. Even so, we might have all the material possessions we need for now.

Support Naked Capitalism

Crossposted on Naked Capitalism.

Being a quantitative, experiment-minded person, I’ve decided to go about helping Yves Smith raise funds for Naked Capitalism using the scientific approach.

After a bit of research on what makes people haul their asses off the couch to write checks, I stumbled upon this blogpost, from nonprofitquarterly.org, which explains that I should appeal to readers’ emotions rather than reason. From the post:

The essential difference between emotion and reason is that emotion leads to action, while reason leads to conclusions.

Let’s face it, regular readers of Naked Capitalism have come to enough conclusions to last a life time, and that’s why they come back for more! But now it’s time for action!

According to them, the leading emotions I should appeal to are as follows:

anger, fear, greed, guilt, flattery, exclusivity, and salvation.

This is a model. The model is that, if I appeal to the above emotions, you guys will write checks. Actually the barrier to entry is even lower, because it’s all done electronically through Paypal. So you can’t even use the excuse that you’ve run out of checks or have lost your pen in the cushions of your sofa.

Here’s the experiment. This time I’ll do my best to appeal to the above emotions. Next time, so a year from now, I’ll instead write a well-reasoned, well-articulated explanation of how reasonable it would be for you to donate some funds towards the continuation of Naked Capitalism.

I’ll do my best to give them both my best shot so as to keep the experiment unbiased, but note I’m choosing this method first.

Anger

This one is kind of too easy. How many time have you gotten extremely pissed off at yet another example of the regulators giving a pass at outright criminal behavior in the financial industry? And where do you go to join in a united chorus of vitriol? Who’s got your back on this, people? That’s right, Yves does.

Fear

Have you guys wondered what the consequences of fighting back for your rights are when you’re foreclosed on and feeling all along fighting against a big bank? Yves has got your back here too, and she helps explain your rights, she helps inspire you to fight, and she gives voice to the voiceless.

Greed

You know what’s amazing about NC? It’s free consulting. Yves has an amazing background and could be charging the very big bucks for this research, but instead she’s giving it away free. That’s like free money.

Guilt

And you know what else? The New York Times charges you for their news, and it’s not even high quality, it has no depth, and they don’t dare touch anything that might harm their comfortable liberal existence. Pussies. Oh wait, maybe that goes into the “anger” section.

Back to guilt: how much money do you regularly spend on crappy stuff that doesn’t actually improve your life and doesn’t inform and inspire you?

Flattery

You know what’s super sexy? You, giving a bit of your money to NC in thanks and appreciation. Hot.

Exclusivity

Not everyone can do this, you know. Only people who are invited even know about this. Which to say, anyone reading this right now, so you. You!

Salvation

Be honest. How much work did you do in the financial sector before you saw the light? Maybe you’re even still working in that cesspool! Maybe you’re even feeling sorry for yourself because your bonus is gonna be shit again this year. Well, it’s time for a wee reality check and some serious paying of the piper. Where by “the piper” I of course refer to Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism.

I believe there’s a way to give to the “Tip Jar” on the top right-hand corner of this page. It might even be filled out for you! Please feel free to add “0”‘s to that number on the right, before clicking the “donate” button. I know it will make you feel better to atone.

When are taxes low enough?

What with the unrelenting election coverage (go Elizabeth Warren!) it’s hard not to think about the game theory that happens in the intersection of politics and economics.

[Disclaimer: I am aware that no idea in here is originally mine, but when has that ever stopped me? Plus, I think when economists talk about this stuff they generally use jargon to make it hard to follow, which I promise not to do, and perhaps also insert salient facts which I don’t know, which I apologize for. In any case please do comment if I get something wrong.]

Lately I’ve been thinking about the push and pull of the individual versus the society when it comes to tax rates. Individuals all want lower tax rates, in the sense that nobody likes to pay taxes. On the other hand, some people benefit more from what the taxes pay for than others, and some people benefit less. It’s fair to say that very rich people see this interaction as one-sided against them: they pay a lot, they get back less.

Well, that’s certainly how it’s portrayed. I’m not willing to say that’s true, though, because I’d argue business owners and generally rich people get a lot back actually, including things like rule of law and nobody stealing their stuff and killing them because they’re rich, which if you think about it does happen in other places. In fact they’d be huge targets in some places, so you could argue that rich people get the most protection from this system.

But putting that aside by assuming the rule of law for a moment, I have a lower-level question. Namely, might we expect equilibrium at some point, where the super rich realize they need the country’s infrastructure and educational system, to hire people and get them to work at their companies and the companies they’ve invested in, and of course so they will have customers for their products and the products of the companies they’ve invested in.

So in other words you might expect that, at a certain point, these super rich people would actually say taxes are low enough. Of course, on top of having a vested interest in a well-run and educated society, they might also have sense of fairness and might not liking seeing people die of hunger, they might want to be able to defend the country in war, and of course the underlying rule of law thingy.

But the above argument has kind of broken down lately, because:

- So many companies are off-shoring their work to places where we don’t pay for infrastructure,

- and where we don’t educate the population,

- and our customers are increasingly international as well, although this is the weakest effect since Europeans can’t be counted on that so much what with their recession.

In other words, the incentive for an individual rich person to argue for lower taxes is getting more and more to be about the rule of law and not the well-run society argument. And let’s face it, it’s a lot cheaper to teach people how to use guns than it is to give them a liberal arts education. So the optimal tax rate for them would be… possibly very low. Maybe even zero, if they can just hire their own militias.

This is an example of a system of equilibrium failing because of changing constraints. There’s another similar example in the land of finance which involves credit default swaps (CDS), described very well in this NYTimes Dealbook entry by Stephen Lubben.

Namely, it used to be true that bond holders would try to come to the table and renegotiate debt when a company or government was in trouble. After all, it’s better to get 40% of their money back than none.

But now it’s possible to “insure” their bonds with CDS contracts, and in fact you can even bet on the failure of a company that way, so you actually can set it up where you’d make money when a company fails, whether you’re a bond holder or not. This means less incentive to renegotiate debt and more of an incentive to see companies go through bankruptcy.

For the record, the suggestion Lubben has, which is a good one, is to have a disclosure requirement on how much CDS you have:

In a paper to appear in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, co-written with Rajesh P. Narayanan of Louisiana State University, I argue that one good starting point might be the Williams Act.

In particular, the Williams Act requires shareholders to disclose large (5 percent or more) equity positions in companies.

Perhaps holders of default swap positions should face a similar requirement. Namely, when a triggering event occurs, a holder of swap contracts with a notional value beyond 5 percent of the reference entity’s outstanding public debt would have to disclose their entire credit-default swap position.

I like this idea: it’s simple and is analogous to what’s already established for equities (of course I’d like to see CDS regulated like insurance, which goes further).

[Note, however, that the equities problem isn’t totally solved through this method: you can always short your exposure to an equity using options, although it’s less attractive in equities than in bonds because the underlying in equities is usually more liquid than the derivatives and the opposite is true for bonds. In other words, you can just sell your equity stake rather than hedge it, whereas your bond you might not be able to get rid of as easily, so it’s convenient to hedge with a liquid CDS.]

Lubben’s not a perfect solution to the problem of creating incentives to make companies work rather than fail, since it adds overhead and complexity, and the last thing our financial system needs is more complexity. But it moves the incentives in the right direction.

It makes me wonder, is there an analogous rule, however imperfect, for tax rates? How do we get super rich people to care about infrastructure and education, when they take private planes and send their kids to private schools? It’s not fair to put a tax law into place, because the whole point is that rich people have more power in controlling tax laws in the first place.

The NYC subway, Aunt Pythia, my zits, and Louis CK

Please pardon the meandering nature of this post. It’s that kind of Monday morning.

——————-

So much for coming together as a city after a disaster. The New York mood was absolutely brutal on the subway this morning.

I went into the subway station in awe of the wondrous infrastructure that is the NY subway, looking for someone to make out with in sheer rapture that my kids are all in school, but after about 15 minutes I was clawing my way, along with about 15 other people, onto the backs of people already stuffed like sausages on the 2 train at 96th street.

For god’s sakes, people, look at all that space up top! Can you people who are traveling together please give each other piggy-back rides so we don’t waste so much goddamn space? Sheesh.

——————-

I’m absolutely blown away by the questions I’ve received already for my Aunt Pythia advice column: you guys are brilliant, interesting, and only a little bit abusive.

My only complaint is that the questions so far are very, very deep, and I was hoping for some very silly and/or sexual questions so I could make this kind of lighthearted and fun in between solving the world’s pressing problem.

Even so, well done. I’m worried I might have to replace mathbabe altogether just to answer all these amazing questions. Please give me more!

——————-

After some amazing on-line and off-line comments for my zit model post from yesterday, I’ve come to a few conclusions:

- Benzoyl peroxide works for lots of people. I’ll try it, what the hell.

- An amazing number of people have done this experiment.

- It may be something you don’t actually want to do. For example, as Jordan pointed out yesterday, what if you find out it’s caused by something you really love doing? Then your pleasure doing that would be blemished.

- It may well be something you really don’t want other people to do. Can you imagine how annoyingly narcissistic and smug everyone’s going to be when they solve their acne/weight/baldness problems with this kind of stuff? The peer pressure to be perfect is gonna be even worse than it currently is. Blech! I love me some heterogeneity in my friends.

——————–

Finally, and I know I’m the last person to find out about everything (except Gangnam Style, which I’ll be sure to remind you guys of quite often), but I finally got around to absolutely digging Louis CK when he hosted SNL this weekend. A crazy funny man, and now I’m going through all his stuff (or at least the stuff available to me for free on Amazon Prime).

On my way to AGNES

I’m putting the finishing touches on my third talk of the week, which is called “How math is used outside academia” and is intended for a math audience at the AGNES conference.

I’m taking Amtrak up to Providence to deliver the talk at Brown this afternoon. After the talk there’s a break, another talk, and then we all go to the conference dinner and I get to hang with my math nerd peeps. I’m talking about you, Ben Bakker.

Since I’m going straight from a data conference to a math conference, I’ll just make a few sociological observations about the differences I expect to see.

- No name tags at AGNES. Everyone knows each other already from undergrad, grad school, or summer programs. Or all three. It’s a small world.

- Probably nobody standing in line to get anyone’s autograph at AGNES. To be fair, that likely only happens at Strata because along with the autograph you get a free O’Reilly book, and the autographer is the author. Still, I think we should figure out a way to add this to math conferences somehow, because it’s fun to feel like you’re among celebrities.

- No theme music at AGNES when I start my talk, unlike my keynote discussion with Julie Steele on Thursday at Strata. Which is too bad, because I was gonna request “Eye of the Tiger”.

For the nerds: what’s wrong with this picture?

h/t Dave:

(Update! Rachel Schutt blogged about this same sign on October 2nd! Great nerd minds think alike :))

Also from the subway:

As my 10-year-old son says, the green guys actually look more endangered since

- their heads are disconnected from their bodies, and

- they are balancing precariously on single rounded stub legs.

Amazon’s binder reviews

If you go to amazon.com and search for “binder” or “3-ring binder” (h/t Dan), the very first hit will take you to the sale page for Avery’s Economy Binder with 1-Inch Round Ring, Black, 1 Binder (3301). The reviews are hilarious and subversive, including this one entitled “A Legitimate Binder”:

I am so excited to order this binder! My husband said that I’ve been doing such a great job of cutting out of work early to serve him meat and potatoes all these years, and he’s finally letting me upgrade from a 2-ring without pockets to a binder with 3 rings and two pockets! The pockets excite me the most. I plan to use the left pocket to hold my resume which will highlight my strongest skills which include but are not limited to laughing while eating yogurt. The right pocket will be great for keeping my stash of aspirin, in case of emergencies when I need to hold it between my knees.

Here’s another, entitled “Doesn’t work as advertised“:

Could’t bind a single damn woman with it! Most women just seem vaguely annoyed when I put it on them and it falls right off. Am I missing something? How’d Mitt do it?

Or this one, called “Such a bargain!“:

I am definitely buying this binder full of women, because even though it works the same as other male binders, you only have to pay $.77 on the dollar for it!

But my favorite one is this (called “Great with Bic lady pens”), partly because it points me to another subversive Amazon-rated product:

I’ve been having a hard time finding a job recently, and realized it was because I wasn’t in a binder. I thought the Avery Economy Binder would be perfect. It needs some tweaks, though. It kicks me out at 5pm so I can cook dinner for a family I don’t have. I also don’t seem to be making as much as the binderless men. And sometimes the rings will snag the lady parts, so maybe mine is defective.

By the way, the BIC pens for Her are a great complement to this binder. I wondered why the normal pens just didn’t feel right. It turns out, I was using man pens. The pink and purple also affirms me as a woman. You can find them here.

I know it says “for her” on the package but I, like many, assumed it was just a marketing ploy seeking to profit off of archaic gender constructs and the “war of the sexes”. Little did I realize that these pens really are for girls, and ONLY girls. Non-girls risk SERIOUS side effects should they use this product. I lent one to my 13-year-old brother, not thinking anything of it, and woke up the next morning to the sound of whinnying coming from the room across the hall. I got out of bed and went to his room to find that my worst fears had been realized:

MY LITTLE BROTHER IS NOW A UNICORN and it’s all my fault. Sure, you’d think that having a unicorn for a little brother would be great but my parents are FURIOUS – I’ve been grounded for a MONTH!!! They made an appointment for him with our family practitioner, but I’m not sure it’ll do any good, and they told me that if it couldn’t be fixed I’d have to get a job to help pay for his feed and lodging D:I repeat, boys, DO NOT USE THIS PEN. Unless you want to be a unicorn, and even then be careful because there’s no telling that you’ll suffer the same side effects.SERIOUSLY BIC IT’S REALLY REALLY IRRESPONSIBLE FOR YOU TO PUT OUT THIS PRODUCT WITHOUT A CLEAR WARNING OF THE RISK IT POSES TO NON-GIRLS. Just saying it’s “For Her” is not enough!!!!

(I’m giving it two stars because even though they got me grounded, the pens still write really nice and bring out my eyes)

What’s a fair price?

My readers may be interested to know that I am currently composing an acceptance letter to be on the board of Goldman Sachs.

Not that they’ve offered it, but Felix Salmon was kind enough to suggest me for the job yesterday and I feel like I should get a head start. Please give me suggestions for key phrases: how I’d do things differently or not, why I would be a breath of fresh air, how it’s been long enough having the hens guard the fox house, etc., that kind of thing.

But for now, I’d like to bring up the quasi-modeling, quasi-ethical topic (my favorite!) of setting a price. My friend Eugene sent me this nice piece he read yesterday on recommendation engines describing the algorithms used by Netflix and Amazon among others, which is strangely similar to my post yesterday coming out of Matt Gattis’s experience working at hunch. It was written by Computer Science professors Joseph A. Konstan and John Riedl from the University of Minnesota, and it does a nice job of describing the field, although there isn’t as much explicit math and formulae.

One thing they brought up in their article is the idea of a business charging certain people more money for items they expect them to buy based on their purchase history. So, if Fresh Direct did this to me, I’d have to pay more every week for Amish Country Farms 1% milk, since we go through about 8 cartons a week around here. They could basically charge me anything they want for that stuff, my 4-year-old is made of 95% milk and 5% nutella.

Except, no, they couldn’t do that. I’d just shop somewhere else for it, somewhere nobody knew my history. It would be a pain to go back to the grocery store but I’d do it anyway, because I’d feel cheated by that system. I’d feel unfairly singled out. For me it would be an ethical decision, and I’d vocally and publicly try to shame the company that did that to me.

It reminds me of arguments I used to have at D.E. Shaw with some of my friends and co-workers who were self-described libertarians. I don’t even remember how they’d start, but they’d end with my libertarian friend positing that rich people should be charged more for the same item. I have some sympathy with some libertarian viewpoints but this isn’t one of them.

First of all, I’d argue, people don’t walk around with a sign on their face saying how much money they have in the bank (of course this is become less and less true as information is collected online). Second of all, even if Warren Buffett himself walked into a hamburger joint, there’s no way they’re going to charge him $1000 for a burger. Not because he can’t afford it, and not even because he could go somewhere else for a cheaper burger (although he could), but because it’s not considered fair.

In some sense rich people do pay more for things, of course. They spend more money on clothes and food than poor people. But on the other hand, they’re also getting different clothes and different food. And even if they spend more money on the exact same item, a pound of butter, say, they’re paying rent for the nicer environment where they shop in their pricey neighborhood.

Now that I write this, I realize I don’t completely believe it. There are exceptions when it is considered totally fair to charge rich people more. My example is that I visited Accra, Ghana, and the taxi drivers consistently quoted me prices that were 2 or 3 times the price of the native Ghanaians, and neither of us thought it was unfair for them to do so. When my friend Jake was with me he’d argue them down to a number which was probably more like 1.5 times the usual price, out of principle, but when I was alone I didn’t do this, possibly because I was only there for 2 weeks. In this case, being a white person in Accra, I basically did have a sign on my face saying I had more money and could afford to spend more.

One last thought on price gouging: it happens all the time, I’m not saying it doesn’t, I am just trying to say it’s an ethical issue. If we are feeling price gouged, we are upset about it. If we see someone else get price gouged, we typically want to expose it as unfair, even if it’s happening to someone who can afford it.

Growing old: better than the alternatives

I enjoyed this article in the Wall Street Journal recently entitled “The ‘New’ Old Age is No Way to Live”. In it the author rejects the idea of following his Baby Boomer brethren in continuing to exercise daily, being hugely productive, and just generally being in denial of their age. From the article:

We are advised that an extended life span has given us an unprecedented opportunity. And if we surrender to old age, we are fools or, worse, cowards. Around me I see many of my contemporaries remaining in their prime-of-life vocations, often working harder than ever before, even if they have already achieved a great deal. Some are writing the novels stewing in their heads but never attempted, or enrolling in classes in conversational French, or taking up jogging, or even signing up for cosmetic surgery and youth-enhancing hormone treatments.

The rest of the article is devoted to describing his trip to the Greek island of Hydra to research how to grow old. There are lots of philosophical references as well as counter-intuitive defenses of being set in your ways and how striving is empty-headed. Whatever, it’s his column. Personally, I like changing my mind about things and striving.

The point I want to make is this: there are far too few people coming out and saying that getting old can be a good thing. It can be a fun thing. Our culture is so afraid of getting old, it’s almost as bad as being fat on the list of no-nos.

I don’t get it. Why? Why can’t we be proud of growing old? It allows us, at the very least, to hold forth more, which is my favorite thing to do.

Since I turned 40 I’ve stopped dying my hair, which is going white, and I’ve taken to calling the people around me “honey”, “sugar”, or “baby”. I feel like I can get away with that now, which is fun. Honestly I’m looking forward to the stuff I can say and do when I’m 70, because I’m planning to be one of those outrageous old women full of spice and opinions. I’m going to make big turkey dinners with all the fixings even when it’s just October and invite my neighbors and friends to come over if my kids are too busy with their lives and family. But if they decide to visit, and if they have kids themselves, I’m going to spoil my grandkids rotten, because I’m totally allowed to do that when I’m the grandma.

Instead of lying about my age down, I’ve taken to lying about my age up. I feel like I am getting away with something if I can pass for 50. After all, why would I still want to be 30? I was close to miserable back then, and I’ve learned a ton in the past 10 years.

Update: my friend Cosma just sent me this poem by Jenny Joseph. For the record I’m wearing purple today:

Warning

When I am an old woman I shall wear purple

With a red hat which doesn’t go, and doesn’t suit me.

And I shall spend my pension on brandy and summer gloves

And satin sandals, and say we’ve no money for butter.

I shall sit down on the pavement when I’m tired

And gobble up samples in shops and press alarm bells

And run my stick along the public railings

And make up for the sobriety of my youth.

I shall go out in my slippers in the rain

And pick flowers in other people’s gardens

And learn to spit.

You can wear terrible shirts and grow more fat

And eat three pounds of sausages at a go

Or only bread and pickle for a week

And hoard pens and pencils and beermats and things in boxes.

But now we must have clothes that keep us dry

And pay our rent and not swear in the street

And set a good example for the children.

We must have friends to dinner and read the papers.

But maybe I ought to practice a little now?

So people who know me are not too shocked and surprised

When suddenly I am old, and start to wear purple.

The investigative mathematical journalist

I’ve been out of academic math a few years now, but I still really enjoy talking to mathematicians. They are generally nice and nerdy and utterly earnest about their field and the questions in their field and why they’re interesting.

In fact, I enjoy these conversations more now than when I was an academic mathematician myself. Partly this is because, as a professional, I was embarrassed to ask people stupid questions, because I thought I should already know the answers. I wouldn’t have asked someone to explain motives and the Hodge Conjecture in simple language because honestly, I’m pretty sure I’d gone to about 4 lectures as a graduate student explaining all of this and if I could just remember the answer I would feel smarter.

But nowadays, having left and nearly forgotten that kind of exquisite anxiety that comes out of trying to appear superhuman, I have no problem at all asking someone to clarify something. And if they give me an answer that refers to yet more words I don’t know, I’ll ask them to either rephrase or explain those words.

In other words, I’m becoming something of an investigative mathematical journalist. And I really enjoy it. I think I could do this for a living, or at least as a large project.

What I have in mind is the following: I go around the country (I’ll start here in New York) and interview people about their field. I ask them to explain the “big questions” and what awesomeness would come from actually having answers. Why is their field interesting? How does it connect to other fields? What is the end goal? How would achieving it inform other fields?

Then I’d write them up like columns. So one column might be “Hodge Theory” and it would explain the main problem, the partial results, and the connections to other theories and fields, or another column might be “motives” and it would explain the underlying reason for inventing yet another technology and how it makes things easier to think about.

Obviously I could write a whole book on a given subject, but I wouldn’t. My audience would be, primarily, other mathematicians, but I’d write it to be readable by people who have degrees in other quantitative fields like physics or statistics.

Even more obviously, every time I chose a field and a representative to interview and every time I chose to stop there, I’d be making in some sense a political choice, which would inevitably piss someone off, because I realize people are very sensitive to this. This is presuming anybody every read my surveys in the first place, which is a big if.

Even so, I think it would be a contribution to mathematics. I actually think a pretty serious problem with academic math is that people from disparate fields really have no idea what each other is doing. I’m generalizing, of course, and colloquiums do tend to address this, when they are well done and available. But for the most part, let’s face it, people are essentially only rewarded for writing stuff that is incredibly “insider” for their field. that only a few other experts can understand. Survey of topics, when they’re written, are generally not considered “research” but more like a public service.

And by the way, this is really different from the history of mathematics, in that I have never really cared about who did what, and I still don’t (although I’m not against name a few people in my columns). The real goal here is to end up with a more or less accurate map of the active research areas in mathematics and how they are related. So an enormous network, with various directed edges of different types. In fact, writing this down makes me want to build my map as I go, an annotated visualization to pair with the columns.

Also, it obviously doesn’t have to be me doing all this: I’m happy to make it an open-source project with a few guidelines and version control. But I do want to kick it off because I think it’s a neat idea.

A few questions about my mathematical journalism plan.

- Who’s going to pay me to do this?

- Where should I publish it?

If the answers are “nobody” and “on mathbabe.org” then I’m afraid it won’t happen, at least by me. Any ideas?

One more thing. This idea could just as well be done for another field altogether, like physics or biology. Are there models of people doing something like that in those fields that you know about? Or is there someone actually already doing this in math?

Suresh Naidu: analyzing the language of political partisanship

I was lucky enough to attend Suresh Naidu‘s lecture last night on his recent work analyzing congressional speeches with co-authors Jacob Jensen, Ethan Kaplan, and Laurence Wilse-Samson.

Namely, along with his co-authors, he found popular three-word phrases, measured and ranked their partisanship (by how often a democrat uttered the phrase versus a republican), and measured the extent to which those phrases were being used in the public discussion before congress started using them or after congress started using them.

Note this means that phrases that were uttered often by both parties were ignored. Only phrases that were uttered more by one party than the other like “free market system” were counted. Also, the words were reduced to their stems and small common words were ignored, so the phrase “united states of america” was reduced to “unite.state.america”. So if parties were talking about the same issue but insisted on using certain phrases (“death tax” for example), then it would show up. This certainly jives with my sense of how partisanship is established by politicians, and for the sake of the paper it can be taken to be the definition.

The first data set he used was a digitized version of all of the speeches from the House since the end of the Civil War, which was also the beginning of the “two-party” system as we know it. Third party politicians were ignored. The proxy for “the public discussion” was taken from Google Book N-grams. It consists of books that were published in English in a given year.

Some of the conclusions that I can remember are as follows:

- The three-word phrases themselves are a super interesting data set; their prevalence, how the move from one side of the aisle to the other over time, and what they discuss (so for example, they don’t discuss international issues that much – which doesn’t mean the politicians don’t discuss international issues, but that it’s not a particularly partisan issue or at least their language around this issue is similar).

- When the issue is economic and highly partisan, it tends to show up “in the public” via Google Books before it shows up in Congress. Which is to say, there’s been a new book written by some economist, presumably, who introduces language into the public discussion that later gets picked up by Congress.

- When the issue is non-economic or only somewhat partisan, it tends to show up in Congress before or at the same time as in the public domain. Members of Congress seem to feel comfortable making up their own phrases and repeating them in such circumstances.

So the cult of the economic expert has been around for a while now.

Suresh and his crew also made an overall measurement of the partisanship of a given 2-year session of congress. It was interesting to discuss how this changed over time, and how having large partisanship, in terms of language, did not necessarily correlate with having stalemate congresses. Indeed if I remember correctly, a moment of particularly high partisanship, as defined above via language, was during the time the New Deal was passed.

Also, as we also discussed (it was a lively audience), language may be a marker of partisan identity without necessarily pointing to underlying ideological differences. For example, the phrase “Martin Luther King” has been ranked high as a partisan democratic phrase since the civil rights movement but then again it’s customary (I’ve been told) for democrats to commemorate MLK’s birthday, but not for republicans to do so.

Given their speech, this analysis did a good job identifying which party a politician belonged to, but the analysis was not causal in the sense of time: we needed to know the top partisan phrases of that session of Congress to be able to predict the party of a given politician. Indeed the “top phrases” changed so quickly that the predictive power may be mostly lost between sessions.

Not that this is a big deal, since of course we know what party a politician is from, but it would be interesting to use this as a measure of how radical or centered a given politician is or will be.

Even if you aren’t interested in the above results and discussion, the methodology is very cool. Suresh and his co-authors view text as its own data set and analyze it as such.

And after all, the words historical politicians spoke is what we have on record – we can’t look into their brain and see what they were thinking. It’s of course interesting and important to have historians (domain experts) inform the process as well, e.g. for the “Martin Luther King” phrase above, but barring expert knowledge this is lots better than nothing. One thing it tells us, just in case we didn’t study political history, is that we’ve seen way worse partisanship in the past than we see now, although things have consistently been getting worse since the 1980’s.

Here’s a wordcloud from the 2007 session; blue and red are what you think, and bigger means more partisan: