Archive

Speaking tonight at NYC Open Data

Tonight I’ll be giving a talk at the NYC Open Data Meetup, organized by Vivian Zhang. I’ll be discussing my essay from last year entitled On Being a Data Skeptic, as well as my Doing Data Science book. I believe there are still spots left if you’d like to attend. The details are as follows:

When: Thursday, March 6, 2014, 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM

Where: Enigma HQ, 520 Broadway, 11th Floor, New York, NY (map)

Schedule:

- 6:15pm: Doors Open for pizza and casual networking

- 7:00pm: Workshop begins

- 8:30pm: Audience Q&A

Gaming the (risk/legal) system

A while back I was talking to some math people about how credit default swaps (CDSs), by their very nature, contain risk that is generally speaking undetectable with standard risk models like Value-at-Risk (VaR).

It occurred to me then that I could put it another way: that perhaps credit default swaps might have been deliberately created by someone who knew all about the standard risk models to game the system. VaR was commercialized in the mid 1990’s and CDSs existed around the same time, but didn’t take off for a decade or so until after VaR became super widespread, which makes it hard to prove without knowing the actors.

For that matter it is reasonable to assume something less deliberate occurred: that a bunch of weird instruments were created and those which hid risk the most thrived, kind of an evolutionary approach to the same theory.

I was reminded recently of this conspiracy theory when Joe Burns talked to my Occupy group last Sunday about his recent book, Reviving the Strike. He talked about the history of strikes as a tool of leverage, and how much less frequently we’ve seen large-scale strikes and industry-wide strikes. He made the point that the legality of strikes has historically been uncorrelated to the existence of strikes – that strikers cannot necessarily wait for the legal system to catch up with the needs of the worker. Sometimes strikers need to exert pressure on legislation.

Anyhoo, one question that came up in Q&A was how, in this world of subsidiaries and franchises, can workers strike against the upper management with control over the actual big money? After all, McDonalds workers work for franchisees who are often not well-off. The real money lives in the mother company but is legally isolated from the franchises.

Similarly, with Walmart, there are massive numbers of workers that don’t work directly for Walmart but do work in the massive supply chain network set up and run by Walmart. They would like to hold Walmart responsible for their working conditions. How does that work?

It seems like the same VaR/CDS story as above. Namely, the legal structure of McDonalds and Walmart almost seems deliberately set up to avoid legal responsibility from disgruntled workers. So maybe first you had the legal system, then lawyers set up the legal construction of the supply chain and workers such that striking workers could only strike against powerless figures, especially in the McDonalds case (since Walmart has plenty of workers working for the mother company as well).

Last couple of points. First, only long-term, powerful enterprises can go to the trouble of gaming such large systems. It’s an artifact of the age of the corporation.

And finally, I feel like it’s hard to combat. We could try to improve our risk or legal system but that makes them – probably – even more complicated, which in turn gives massive corporations more ways to game them. Not to be a cynic, but I don’t see a solution besides somehow separately sidestepping our personal risk exposure to these problems.

How much is your data worth?

I heard an NPR report yesterday with Emily Steel, reporter from the Financial Times, about what kind of attributes make you worth more to advertisers. She has developed an ingenious online calculator here, which you should go play with.

As you can see it cares about things like whether you’re about to have a kid or are a new parent, as well as if you’ve got some disease where the industry for that disease is well-developed in terms of predatory marketing.

For example, you can bump up your worth to $0.27 from the standard $0.0007 if you’re obese, and another $0.10 if you admit to being the type to buy weight-loss products. And of course data warehouses can only get that much money for your data if they know about your weight, which they may or may not since if you don’t buy weight-loss products.

The calculator doesn’t know everything, and you can experiment with how much it does know, but some of the default assumptions are that it knows my age, gender, education level, and ethnicity. Plenty of assumed information to, say, build an unregulated version of a credit score to bypass the Equal Credit Opportunities Act.

Here’s a price list with more information from the biggest data warehouser of all, Acxiom.

Report from an MSRI MOOC conversation

I am back from Berkeley where I attended a couple of hours of conversations about MOOCs last Friday up at MSRI.

It was a panel discussion given mostly by math and stats people who themselves run MOOCs, and I was wondering if the people who are involved have a better sense of the side effects and feedback loops involved in the process. After all, I’m claiming that the MOOC Revolution will lead to the end of math research, and I wanted to be proven wrong.

Unfortunately, I left feeling like I have even more evidence that my fears will be realized.

I think the critical moment came when Ani Adhikari spoke. Professor Adhikari is in the second semester of giving her basic stats MOOC, and from how she described it, she is incredibly good at it, and there’s a social network aspect of the class which seems like it’s going really well – she says she spends 30 minutes to an hour a day on it herself, interacting with students. I think she said 28,000 students took it her first semester in addition to her in-class students at Berkeley. I know and respect Professory Adhikari personally, as I taught for her at the Berkeley Mills summer program for women many years ago. I know how devoted she is to good teaching.

Even so, she lost me late in the discussion when she explained that EdX, the platform which hosts her stats MOOC, wanted to offer her class three times a year without her participation. She said something to the effect that MOOC professors had to be “extra vigilant” about this outrageous idea and guard against it at all costs.

After all, she said, at the end of the day the MOOC videos are something like a fancy textbook, and we don’t hand out textbooks and claim they are courses, so we by the same token cannot hand out MOOC videos (and presumably the social networks associated with them) and claim they are courses.

When I pressed her in the Q&A session as to how exactly she was going to remain vigilant against this threat, she said she has a legal contract with EdX that prevented them from offering the course without her approval.

And I’m happy for her and her great contract, but here are two questions for her and for the community.

First, how long until someone in math or stats makes a kick-ass MOOC and doesn’t remember to have that air-tight legal contract? Or has an actual legal battle with EdX and realized their lawyers are not as expensive? Or believes that “information should be free” and does it with the express intention of letting the MOOC be replayed forever?

Second, how much sense does it make to claim that you and your presence are super critical to the success of a MOOC if 28,000 people took this class and you interacted at most one hour a day? Can you possibly claim that the average student benefitted from your presence? It seems to me that the value proposition for the average MOOC student is very similar whether you are there or not.

Overall the impression I got from the speakers, who were mostly MOOC evangelists and involved with MOOCs themselves, was that they loved MOOCs because MOOCs were working for them. They weren’t looking much beyond that point to side effects.

There was one exception, namely Susan Holmes, who listed some side effects of MOOCs including a decreased need for math Ph.D.’s. Unfortunately the conversation didn’t dwell on this, though, and it happened at the very end of the day.

Here’s what I’d like to see: a conversation at MSRI about the future of math research funding in the context of MOOCs and a reduced NSF, where hopefully we come up with something besides “Jim Simons”. It’s extra ironic that the conversation, if it happens, would be held in the Simons Theater.

Data journalism

I’m in Berkeley this week, where I gave two talks (here are my slides from Monday’s talk on recommendation engines, and here are my slides from Tuesday’s talk on modeling) and I’ve been hanging out with math nerds and college friends and enjoying the amazing food and cafe scene. This is the freaking life, people.

Here’s what’s been on my mind lately: the urgent need for good data journalism. If you read this Washington Post blog by Max Fisher you will get at one important angle of the problem. The article talks about the need for journalists to be competent in basic statistics and exploratory data analysis to do reasonable reporting on data, in this case the state of journalistic freedoms.

And you might think that, as long as journalists report on other stuff that’s not data heavy, they’re safe. But I’d argue that the proliferation of data is leaking into all corners of our culture, and basic data and computing literacy is becoming increasingly vital to the job of journalism.

Here’s what I’m not saying (a la Miss Disruption): learn to code, journalists, and everything will be cool. To be clear, having data skills is necessary but not sufficient.

So it’s more like, if you don’t learn to code, and even more importantly if you don’t learn to be skeptical of the models and the data, then you will have yet another obstacle between you and the truth.

Here’s one way to think about it. A few days ago I wrote a post about different ways to define and regulate discriminatory acts. On the one hand you have acts or processes that are “effectively discriminatory” and on the other you have acts or processes that are “intentionally discriminatory.”

In this day and age, we have complicated, opaque, and proprietary models: in other words, a perfect hiding place for bad intentions. It would be idiotic for someone with the intention of being discriminatory to do so outright. It’s much easier to embed such a thing in an opaque model where it will seem unintentional and will probably never be discovered at all.

But how is an investigative journalist going to even approach that? The first thing they need is to arm themselves with the right questions and the right attitude. And it wouldn’t help if they or their team can perform a test on the data and algorithm as well.

I’m not saying that we’re going to suddenly have do-everything super human journalists. Just as the list of job requirements for data scientists is outrageously long and nobody can be expert at everything, we will have to form teams of journalists which as a whole has lots of computing and investigative expertise.

The alternative is that the models go unchallenged, which is a really bad idea.

Here’s a perfect example of what I think needs to happen more: when ProPublica reverse-engineered Obama’s political messaging model.

What privacy advocates get wrong

There’s a wicked irony when it comes to many privacy advocates.

They are often narrowly focused on the their own individual privacy issues, but when it comes down to it they are typically super educated well-off nerds with few revolutionary thoughts. In other words, the very people obsessing over their privacy are people who are not particularly vulnerable to the predatory attacks of either the NSA or the private companies that make use of private data.

Let me put it this way. If I’m a data scientist working at a predatory credit card firm, seeking to build a segmentation model to target the most likely highly profitable customers – those that ring up balances and pay off minimums every month, sometimes paying late to accrue extra fees – then if I am profiling a user and notice an ad blocker or some other signal of privacy concerns, chances are that becomes a wealth indicator and I leave them alone. The mere presence of privacy concerns signals that this person isn’t worth pursuing with my manipulative scheme.

If you don’t believe me, take a look at a recent Slate article written by Cyrus Nemati and entitled Take My Data Please: How I learned to stop worrying and love a less private internet.

In it he describes how he used to be privacy obsessed, for no better reason than that he like to stick up a middle finger to those who would collect his data. I think that article should have been called something like, Well-educated white guy was a privacy freak until he realized he didn’t have to be because he’s a well-educated white guy.

He concludes that he really likes how well customized things are to his particular personality, and that shucks, we should all just appreciate the web and stop fretting.

But here’s the thing, the problem isn’t that companies are using his information to screw Cyrus Nemati. The problem is that the most vulnerable people – the very people that should be concerned with privacy but aren’t – are the ones getting tracked, mined, and screwed.

In other words, it’s silly for certain people to be scrupulously careful about their private data if they are the types of people who get great credit card offers and have a stable well-paid job and are generally healthy. I include myself in this group. I do not prevent myself from being tracked, because I’m not at serious risk.

And I’m not saying nothing can go wrong for those people, including me. Things can, especially if they suddenly lose their jobs or they have kids with health problems or something else happens which puts them into a special category. But generally speaking those people with enough time on their hands and education to worry about these things are not the most vulnerable people.

I hereby challenge Cyrus Nemati to seriously consider who should be concerned about their data being collected, and how we as a society are going to address their concerns. Recent legislation in California is a good start for kids, and I’m glad to see the New York Times editors asking for more.

Ya’ make your own luck, n’est-ce pas?

This is a guest post by Leopold Dilg.

There’s little chance we can underestimate our American virtues, since our overlords so seldom miss an opportunity to point them out. A case in point – in fact, le plus grand du genre, though my fingers tremble as I type that French expression, for reasons I’ll explain soon enough – is the Cadillac commercial that interrupted the broadcast of the Olympics every few minutes.

A masterpiece of casting and directing and location scouting, the ad follows a middle-aged man, muscular enough but not too proud to show a little paunch – manifestly a Master of the Universe – strutting around his chillingly modernist $10 million vacation house (or is it his first or fifth home? no matter), every pore oozing the manly, smirky bearing that sent Republican country-club women swooning over W.

It starts with Our Hero, viewed from the back, staring down his infinity pool. He pivots and stares down the viewer. He shows himself to be one of the more philosophical species of the MotU genus. “Why do we work so hard?” he puzzles. “For this? For stuff?….” We’re thrown off balance: Will this son of Goldman Sachs go all Walden Pond on us? Fat chance.

Now, still barefooted in his shorts and polo shirt, he’s prowling his sleak living room (his two daughters and stay-at-home wife passively reading their magazines and ignoring the camera, props in his world no less than his unused pool and The Car yet to be seen) spitting bile at those foreign pansies who “stop by the café” after work and “take August off!….OFF!” Those French will stop at nothing.

“Why aren’t YOU like that,” he says, again staring us down and we yield to the intimidation. (Well gee, sir, of course I’m not. Who wants a month off? Not me, absolutely, no way.) “Why aren’t WE like that” he continues – an irresistible demand for totalizing merger. He’s got us now, we’re goose-stepping around the TV, chanting “USA! USA! No Augusts off! No Augusts off!”

No, he sneers, we’re “crazy, hardworking believers.” But those Frogs – the weaklings who called for a double-check about the WMDs before we Americans blasted Iraqi children to smithereens (woops, someone forgot to tell McDonalds, the official restaurant of the U.S. Olympic team, about the Freedom Fries thing; the offensive French Fries are THERE, right in our faces in the very next commercial, when the athletes bite gold medals and the awe-struck audience bites chicken nuggets, the Lunch of Champions) – might well think we’re “nuts.”

“Whatever,” he shrugs, end of discussion, who cares what they think. “Were the Wright Brothers insane? Bill Gates? Les Paul?… ALI?” He’s got us off-balance again – gee, after all, we DO kinda like Les Paul’s guitar, and we REALLY like Ali.

Of course! Never in a million years would the hip jazz guitarist insist on taking an August holiday. And the imprisoned-for-draft-dodging boxer couldn’t possibly side with the café-loafers on the WMD thing. Gee, or maybe…. But our MotU leaves us no time for stray dissenting thoughts. Throwing lunar dust in our eyes, he discloses that WE were the ones who landed on the moon. “And you know what we got?” Oh my god, that X-ray stare again, I can’t look away. “BORED. So we left.” YEAH, we’re chanting and goose-stepping again, “USA! USA! We got bored! We got bored!”

Gosh, I think maybe I DID see Buzz Aldrin drumming his fingers on the lunar module and looking at his watch. “But…” – he’s now heading into his bedroom, but first another stare, and pointing to the ceiling – “…we got a car up there, and left the keys in it. You know why? Because WE’re the only ones goin’ back up there, THAT’s why.” YES! YES! Of COURSE! HE’S going back to the moon, I’M going back to the moon, YOU’RE going back to the moon, WE’RE ALL going back to the moon. EVERYONE WITH A U.S. PASSPORT is going back to the moon!!

Damn, if only the NASA budget wasn’t cut after all that looting by the Wall Street boys to pay for their $10 million vacation homes, WE’D all be going to get the keys and turn the ignition on the rover that’s been sitting 45 years in the lunar garage waiting for us. But again – he must be reading our mind – he’s leaving us no time for dissent, he pops immediately out of his bedroom in his $12,000 suit, gives us the evil eye again, yanks us from the edge of complaint with a sharp, “But I digress!” and besides he’s got us distracted with the best tailoring we’ve ever seen.

Finally, he’s out in the driveway, making his way to the shiny car that’ll carry him to lower Manhattan. (But where’s the chauffer? And don’t those MotUs drive Mazerattis and Bentleys? Is this guy trying to pull one over on the suburban rubes who buy Cadillacs stupidly thinking they’ve made it to the big time?)

Now the climax: “You work hard, you create your own luck, and you gotta believe anything is possible,” he declaims.

Yes, we believe that! The 17 million unemployed and underemployed, the 47 million who need food stamps to keep from starving, the 8 million families thrown out of their homes – WE ALL BELIEVE. From all the windows in the neighborhood, from all the apartments across Harlem, from Sandy-shattered homes in Brooklyn and Staten Island, from the barren blast furnaces of Bethlehem and Youngstown, from the foreclosed neighborhoods in Detroit and Phoenix, from the 70-year olds doing Wal-mart inventory because their retirement went bust, from all the kitchens of all the families carrying $1 trillion in college debt, I hear the national chant, “YOU MAKE YOUR OWN LUCK! YOU MAKE YOUR OWN LUCK!”

And finally – the denouement – from the front seat of his car, our Master of the Universe answers the question we’d all but forgotten. “As for all the stuff? That’s the upside of taking only two weeks off in August.” Then the final cold-blooded stare and – too true to be true – a manly wink, the kind of wink that makes us all collaborators and comrades-in-arms, and he inserts the final dagger: “N’est-ce pas?”

N’est-ce pas?

How can we regulate around discrimination?

I am looking into the history of anti-discrimination laws like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, (ECOA) and how it got passed, and hopefully find data to measure how well it’s worked since it got passed in 1974.

Putting aside the history of this legislation for now – although it is fascinating – I’d like to talk this morning about this paper from 1989 written by Gregory Elliehausen and Thomas Durkin from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, which discusses the abstract question of approaches to defining and regulation around discrimination.

This came up because when Congress passed ECOA, they left it to the regulators – in this case the Federal Reserve – to decide exactly how to write the rules, which pertain to credit decisions (think credit card offerings). From the article:

The term “discriminate against an applicant” was defined in Section 202. 2(n) as meaning “to treat an applicant less favorably than other applicants.” By itself, this rule does not offer an unquestionably unambiguous operational definition of socially unacceptable discrimination in a screening context where limited selections are constantly being made from a longer list of applicants.

The paper then goes on to list 3 separate regulatory approaches to anti-discrimination regulation. I have found these three definition really interesting and thought-provoking. I won’t even go into the rest of the paper on this post because I think just this list of three approaches is so interesting. Tell me if you agree.

1) The “effects-based” approach to regulation. This is the idea that, we don’t need to know how you actually make credit decisions, but if the effect is that no women or minorities ever get credit from you, then you’re doing something wrong. If you want to be really extreme in this category you get to things like quotas. if you want to be less extreme you think about studying applications that are similar except for one thing like race or gender, kind of like the the male vs. female science lab application test studied here. Needless to say, effects-based regulation is not in use, it’s considered too extreme.

2) The “intent-based” approach to regulation. This is where you have to prove intent to discriminate. It’s super rare that you can do that, because it’s super rare that people aiming to discriminate are dumb enough to make it obvious. Far easier to embed discrimination in a model where you can maintain plausible deniability. Although intent-based regulation is considered too extreme in the other direction, it seems to be what surfaces when there’s a legal case (although I’m not a legal expert).

3) The “practices-based” approach to regulation. This is where you make a list of acceptable or unacceptable practices in extending credit and hope you cover everything. So for example you aren’t allowed to explicitly use race or marital status or governmental assistance status in your credit models. This is what the Fed finally decided to use, and it makes sense in that it’s easy to implement, but of course the lists change over time, and that’s the key issue (for me anyway): we need to update those lists in the age of big data.

Tell me if you think there’s yet another approach not mentioned. And note these regulatory approaches correspond to different ways of thinking about or even defining discrimination, which is itself a great reason to list them comprehensively. I think my future discussions about what constitutes discrimination will be informed by which above approach will pick up on a given instance.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia has some exciting news.

After spending about 5 days of the last 7 in bed with an awful flu, and finishing off both seasons of House of Cards (with the associated feeling of being simultaneously drowned in cynicism and phlegm), Aunt Pythia started in on Battlestar Galactica, which she honestly should have done years ago.

And do you know who stars in that series, at least in Season 2? None other than yours truly, Pythia the Oracle of Delphi! I am honored, and I hope you are honored by association. Go ahead, feel the honor.

After you enjoy my column (and the honor!) today please don’t forget to:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I gave a talk at this year’s JMM in Baltimore. It was one of those super rushed 10-minute talks. But giving any talk at all sufficed for my university to pay for my travel and lodging. That’s not to say that I didn’t take it seriously. I did. I even dressed nice for it, which I don’t normally do as a grad student and mother of a toddler. I bothered to care about a talk that has only enough time to explain its title because this year is an important year for me. It’s my last year of my PhD and I’m applying for postdocs and jobs. It’s why I attended the JMM.

My talk went well enough. I got a few questions at the end and I didn’t go over my time. And that should be the end of it. JMM is over. I can get back to stressing over my dissertation. But I got an email. An email from someone who was in the audience. He wrote to me that he enjoyed my talk and would like to meet me for dinner. He even added that this is “to be clear, a non-math invitation.”

My first thought was that I should send a reply correcting the many grammatical errors I found in his very short email. But that thought quickly changed into anger. I traveled a very long distance to work. I’m taking time away from my research, away from my 2-year-old so that I can present myself professionally to an audience of my peers and potential employers. I hope and expect to be treated like a real scientist. I remembered all the stories, all of the frustration of so many of my friends and colleagues, scientists who also happen to be women, who were treated with anything but respect just because they weren’t born with a penis. I was insulted, furious that some stupid little boy thought that this sort of behavior is appropriate.

But there was always the small chance that he is, in fact, stupid—in certain ways. After all, this is a math conference. There are mathematicians who, while brilliant, may not have (let’s just say) mature social skills. (Though this guy’s probably not too clever since a quick Google search would have revealed that I have a webpage containing a photo of me and my family and therefore not likely to be interested in dating.)

I replied with an invitation to meet for lunch. So that I can verify that he’s not developmentally challenged and confirm his implied intention. And then yell at him to his face. He didn’t end up showing, even though he sounded eager to meet in the multiple emails he sent following my response. He was probably scared away by the large crowd of my friends that had gathered around our meeting place to support me or, more likely, to witness the spectacle.

Most of the men I spoke to about this incident were sympathetic to the poor idiotic horny kid who clearly had no idea how to talk to girls. They recalled some embarrassing moments from their youth and said that I should have just mercifully sent him a gentle rejection.

I, on the other hand, find his action to be a stark example of how women are not taken seriously in science and feel he should be told that this sort of behavior is not excusable. Granted, a public shaming may not have been warranted. But I think that I am right to feel insulted in this situation.

I’m still thinking about emailing this guy and telling him off. My friend (who is usually a feminist) thinks that while the guy had absolutely no tact and needs some guidance on interacting with other humans, finding a speaker attractive and approaching her at a conference is not wrong. He thinks that had the guy joined me and my friends for drinks after my talk and then later admitted to his interest in me, I would not have been offended. I disagree.

What do you think? Am I overreacting?

Scientista (in training)

Dear Scientista,

Wow, that was a really long question, but I decided to publish it all anyway, because I can see you earnestly want my advice. Not so sure you’re going to like my advice though.

Because here’s the thing, you are absolutely overreacting. I mean, that’s ok, and no actual harm done, but what a huge amount of time wasted at JMM where you could have been doing math, drinking bourbon, or playing bridge.

That’s not to say I like what the guy did, it was definitely obtuse to the point of idiocy, but there you have it, he’s an idiot. Best thing to do in that situation is to delete the email and not give it another thought.

I mean, I guess there might have been a side benefit for the rest of the math community in this planned public shaming, if word had gotten out that this guy had written such an unsolicited and unwelcome email. It might have given pause to the 450 other such emails that happened that weekend. Or not.

Also, I think we should be careful to separate your efforts in preparing your talk and coming to the conference, which were real, from this guy’s sexual interest. I’m guessing that, had you gotten 5 emails talking about the math and how awesome it is, and this email to boot, you would have been able to shrug this one off. It’s the unfortunate nature of short talks that they take a lot to prepare for but there’s little chance of getting good feedback. But let’s not take out that frustration on him entirely.

In one way I’d like to defend this guy: at least he made his explicit desires known. It would have been worse, in my opinion, if he’d come up with some math pretext for meeting and then put his hand on your knee at lunch.

Plus, I’d like to take this opportunity to defend sex at math conferences in general. I mean, it’s one of the classic ways of blowing off some steam after a long day of whirlwind 10-minute talks, married or unmarried.

Finally, and I hope this doesn’t sound too harsh, I’d like to give you some general advice. You are a woman in math, which means you are a warrior, even if you didn’t want to sign up for that. And the best and easiest way to be a warrior is to have a thick skin, to remember the victories, and to ignore the defeats.

And I don’t mean stay quiet about awful, actionable sexism that threatens your job or your responsibilities at work, but I do mean deleting idiotic emails without a second thought, from now on.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Given that the entire financial industry seems to be loaded with unethical behavior, what do you think are ethical ways to invest your money? Certainly choosing credit unions over large banks seems to be a good way for your savings but I am curious about how you would invest for retirement. Do you think there are ethical ways to invest in stocks, bonds, etc?

Thanks!

Serious Pondering About Money

Dear SPAM,

I get asked this a lot, but I don’t have a good answer. And honestly I worry more about people who don’t have any money saved for retirement at all, and are stuck in student or medical debt.

If you really want my advice, I’d say there are three things you could or should worry about regarding savings: liquidity, risk, and ethics. You may have more things you worry about, but this is just a starting point. I’d suggest you divide your money up into those categories, depending on how you weight the associated concerns.

For the liquidity part, keep cash in a savings account (FDIC insured) or a money market account (not FDIC insured). For the risk part, invest in an ETF for the overall market, because we’ve seen that the government props up the market so you want to ride that buffered wave whilst minimizing fees. For the ethical part, track down a company – or even an individual – doing stuff you think is good for the world and invest in it. It’s highly illiquid and highly risky to do that, but you’ve already taken care of those concerns.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Is it OK to review NSA grant proposals?

You might have seen Beilinson’s letter to the AMS notices extolling mathematicians to break ties with the NSA. I kind of sympathize with it. The AMS helps the NSA administer its grants program and I recently got two proposals to referee. These were from young mathematicians that I hold in high regard and think deserve to be funded. As NSF funding is dwindling, if they don’t get the NSA grant they might be unfunded. Moreover, I am knowledgeable about their work and felt that if I turned down the request it would be bad for them, so I decided to review the proposals. Have I done the right thing?

Not Sure Actually

Dear NSA,

I feel your pain. The funding is drying up for these worthy researchers, but you’d rather not feel like a collaborator. Those are directly conflicting issues.

And it’s exactly what I fear when I think of the oncoming MOOC revolution and the end of math research. Who is going to fund math research when calculus is gone? The obvious answer is private companies, private individuals, and places like the NSA. Not a pretty picture.

My best advice for you is to review the proposals because you want those researchers funded – and feel slightly better that they’re doing research external to the NSA – and at the same time get involved with solving the larger funding problem for mathematics. This could mean going to talk to your congressperson about the need for mathematical funding or it could mean spreading the word more generally about the importance of math research.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Auntie Pythia,

The Facebook Data Science folks posted a series of blog posts about love (or at least relationships). As a data scientist and sex oracle, what do you make of the results and/or on the use of social network data for these kinds of studies?

Love,

Lots Of Valentine’s Extrapolations

Dear LOVE,

Wow, thanks for the link. I happen to know the author, Mike Develin, of those posts, first because he was a (brilliant) student of mine at math camp way back in like 1993, and second because we worked at D.E. Shaw together – although he worked in the California office.

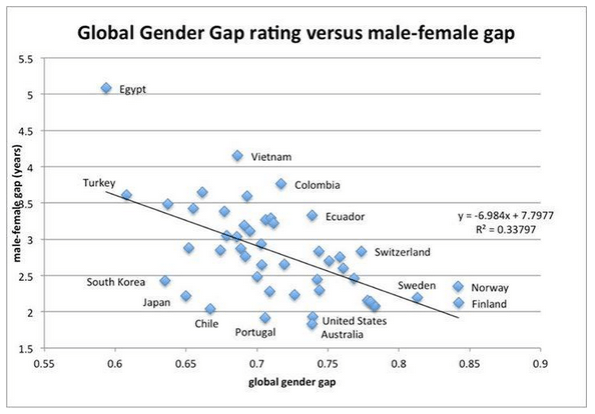

So anyhoo, I like the posts. They’re smart. The one thing I’d say, for example about the age difference of couples in different countries, is that I have to assume there’s a bias away from older middle-aged couples and towards couples where the husband is old and the wife is young. Here’s a picture:

I say this because, even if both members of the couple are on Facebook (and that already skews somewhat young), I would guess older people are less likely to divulge their marital status. That kind of thing makes me think we should look at these charts with the caveat that they are true “in the context of Facebook data”.

In terms of the ethics of this kind of use of aggregated data, I’d say it’s great. The stuff I think is scary is the stuff that isn’t aggregated and is hidden from us.

Best,

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

The CARD Act works

Every now and then you see a published result that has exactly the right kind of data, in sufficient amounts, to make the required claim. It’s rare but it happens, and as a data lover, when it happens it is tremendously satisfying.

Today I want to share an example of that happening, namely with this paper entitled Regulating Consumer Financial Products: Evidence from Credit Cards (hat tip Suresh Naidu). Here’s the abstract:

We analyze the effectiveness of consumer financial regulation by considering the 2009 Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act in the United States. Using a difference-in-difference research design and a unique panel data set covering over 150 million credit card accounts, we find that regulatory limits on credit card fees reduced overall borrowing costs to consumers by an annualized 1.7% of average daily balances, with a decline of more than 5.5% for consumers with the lowest FICO scores. Consistent with a model of low fee salience and limited market competition, we find no evidence of an offsetting increase in interest charges or reduction in volume of credit. Taken together, we estimate that the CARD Act fee reductions have saved U.S. consumers $12.6 billion per year. We also analyze the CARD Act requirement to disclose the interest savings from paying off balances in 36 months rather than only making minimum payments. We find that this “nudge” increased the number of account holders making the 36-month payment value by 0.5 percentage points.

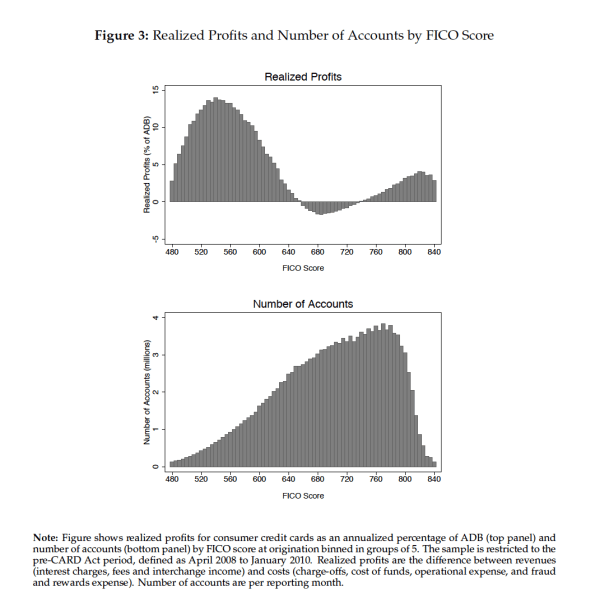

That’s a big savings for the poorest people. Read the whole paper, it’s great, but first let me show you some awesome data broken down by FICO score bins:

Interestingly, some people in the middle lose money for credit card companies. Poor people are great customers but there aren’t so many of them.

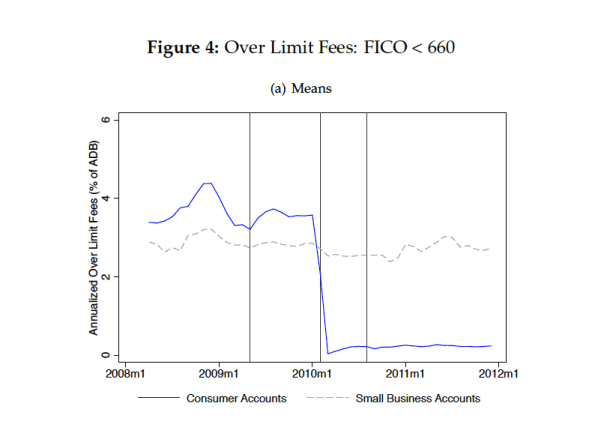

The study compared consumer versus small business credit cards. After CARD Act implementation, fees took a nosedive.

This data, and the results in this paper, fly directly in the face of the myth that if you regulate away predatory fees in one way, they will pop up in another way. That myth is based on the assumption of a competitive market with informed participants. Unfortunately the consumer credit card industry, as well as the small business card industry, is not filled with informed participants. This is a great example of how asymmetric information causes predatory opportunities.

JP Morgan suicides and the clustering illusion

Yesterday a couple of people sent me this article about mysterious deaths at JP Morgan. There’s no known connection between them, but maybe it speaks to some larger problem?

I don’t think so. A little back-of-the-envelope calculation tells me it’s not at all impressive, and this is nothing but media attention turned into conspiracy theory with the usual statistics errors.

Here are some numbers. We’re talking about 3 suicides over 3 weeks. According to wikipedia, JP Morgan has 255,000 employees, and also according to wikipedia, the U.S. suicide rate for men is 19.2 per 100,000 per year, and for women is 5.5. The suicide rates for Hong Kong and the UK, where two of the suicides took place, are much higher.

Let’s eyeball the overall rate at 19 since it’s male dominated and since may employees are overseas in higher-than-average suicide rate countries.

Since 3 weeks is about 1/17th of a year, we’d expect to see about 19/17 suicides per year per 100,000 employees, and seince we have 255,000 employees, that means about 19/17*2.55 = 2.85 suicides in that time. We had three.

This isn’t to say we’ve heard about all the suicides, just that we expect to see about one suicide a week considering how huge JP Morgan is. So let’s get over this, it’s normal. People commit suicide pretty regularly.

It’s very much like how we heard all about suicides at Foxconn, but then heard that the suicide rate at Foxconn is lower than the general Chinese population.

There is a common statistical problem called the clustering illusion, whereby actually random events look clustered sometimes. Here’s a 2-dimensional version of the clustering illusion:

Actually my calculation above points to something even dumber, which is that we expected 2.85 suicides and we saw 3, so it’s not even a proven cluster. Although it could be, because again we probably didn’t hear about all of them. Maybe it’s a cluster of “really obvious jump-from-a-building” suicides.

And I’m not saying JP Morgan is a nice place to work. I feel suicidal just thinking about working there myself. But I don’t want us to jump to any statistically unsupported conclusions.

Crashing a Wall Street party

I’m just recovering from a killer flu that had me wheezing and miserable for 5 days. I have a whole backlog of rants and vents but no time this morning to even start, so instead let me suggest you read this article (hat tip Chris Wiggins) about a New York Times reporter who crashed the yearly party of Kappa Beta Phi, a Wall Street secret society. Pretty amazing, if true.

Does making it easier to kill people result in more dead people?

A fascinating and timely study just came out about the “Stand Your Ground” laws. It was written by Cheng Cheng and Mark Hoekstra, and is available as a pdf here, although I found out about in a Reuters column written by Hoekstra. Here’s a longish but crucial excerpt from that column:

It is fitting that much of this debate has centered on Florida, which enacted its law in October of 2005. Florida provides a case study for this more general pattern. Homicide rates in Florida increased by 8 percent from the period prior to passing the law (2000-04) to the period after the law (2006-10).By comparison, national homicide rates fell by 6 percent over the same time period. This is a crude example, but it illustrates the more general pattern that exists in the homicide data published by the FBI.

The critical question for our research is whether this relative increase in homicide rates was caused by these laws. Several factors lead us to believe that laws are in fact responsible. First, the relative increase in homicide rates occurred in adopting states only after the laws were passed, not before. Moreover, there is no history of homicide rates in adopting states (like Florida) increasing relative to other states. In fact, the post-law increase in homicide rates in states like Florida was larger than any relative increase observed in the last 40 years. Put differently, there is no evidence that states like Florida just generally experience increases in homicide rates relative to other states, even when they don’t pass these laws.

We also find no evidence that the increase is due to other factors we observe, such as demographics, policing, economic conditions, and welfare spending. Our results remain the same when we control for these factors. Along similar lines, if some other factor were driving the increase in homicides, we’d expect to see similar increases in other crimes like larceny, motor vehicle theft and burglary. We do not. We find that the magnitude of the increase in homicide rates is sufficiently large that it is unlikely to be explained by chance.

In fact, there is substantial empirical evidence that these laws led to more deadly confrontations. Making it easier to kill people does result in more people getting killed.

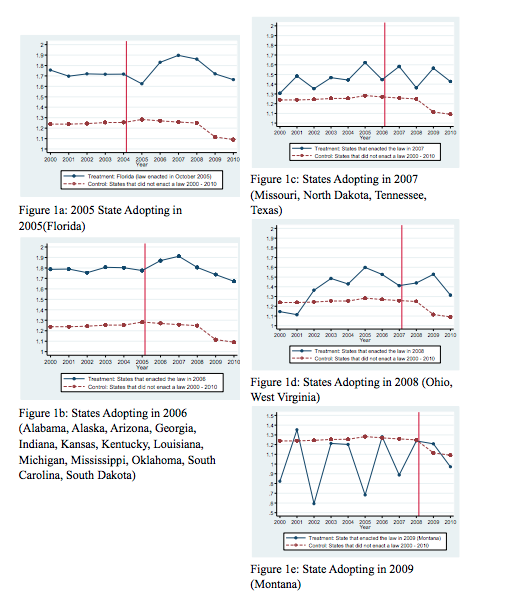

If you take a look at page 33 of the paper, you’ll see some graphs of the data. Here’s a rather bad picture of them but it might give you the idea:

That red line is the same in each plot and refers to the log homicide rate in states without the Stand Your Ground law. The blue lines are showing how the log homicide rates looked for states that enacted such a law in a given year. So there’s a graph for each year.

In 2009 there’s only one “treatment” state, namely Montana, which has a population of 1 million, less than one third of one percent of the country. For that reason you see much less stable data. The authors did different analyses, sometimes weighted by population, which is good.

I have to admit, looking at these plots, the main thing I see in the data is that, besides Montana, we’re talking about states that have a higher homicide rate than usual, which could potentially indicate a confounding condition, and to address that (and other concerns) they conducted “falsification tests,” which is to say they studied whether crimes unrelated to Stand Your Ground type laws – larceny and motor vehicle theft – went up at the same time. They found that the answer is no.

The next point is that, although there seem to be bumps for 2005, 2006, and 2008 for the two years after the enactment of the law, there doesn’t for 2007 and 2009. And then even those states go down eventually, but the point is they don’t go down as much as the rest of the states without the laws.

It’s hard to do this analysis perfectly, with so few years of data. The problem is that, as soon as you suspect there’s a real effect, you’d want to act on it, since it directly translates into human deaths. So your natural reaction as a researcher is to “collect more data” but your natural reaction as a citizen is to abandon these laws as ineffective and harmful.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Good morning, fine readers! Aunt Pythia is very happy to be here this morning, and she’s got some wonderful news and a request.

First the news. It’s not snowing today! I take it back it just started snowing.

Now the request. As readers know, Aunt Pythia never makes up questions, but she’s not above making requests. That’s just how her ethics roll. And Aunt Pythia is itching to discuss this vile Valentine’s Day column from Susan Patton, so please take a look and let the questions roll in, thanks.

After you enjoy my column today – there’s sex at the end – please don’t forget to:

think of something to ask Aunt Pythia at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Before reading about the Target data loss, I didn’t realize that each company is responsible for the security of the in-store network that contains and transmits the data entered when I purchase an item. I thought there was some standard national process that controlled/enacted all debit/credit card transactions. How dumb I was. Now I am seriously thinking of trying to switch to using only cash. (This is leaving aside the motivation of achieving privacy in what I purchase.) I trust you to be savvy, so here are some questions:

- Is it worth switching to using only cash in-store?

- What about online? Just use Paypal? (How safe is that?) Have a credit card only used for online purchases, that isn’t linked to my bank accounts?

- To be honest, I am somewhat freaking out that with an all-digital banking system my money (and millions of other people’s) could just vanish from my “bank account” in some hacking extravaganza. After all my “bank account” is just some picture on my screen representing my hard-earned savings. Should we print out bank statements every month and keep them under our mattresses? I have decided that I’ll count on the FDIC, but how do I prove to the FDIC how much money I had if my bank’s been hacked and all my online records destroyed?

Dr. Suspicious Ignorant Naive

Dear Dr. SIN,

Let me try to convince you to be more worried about being tracked than this particular security issue.

Your potential losses on lost or stolen credit cards and debit cards top out at $50 if you report the loss quickly – see the FTC website for more information on this. And by “quickly” that means from the moment you are made aware of it, either by being told by the company or by monthly statements that show erroneous charges. So keep an eye on those statements and you’re pretty well protected.

Credit cards have slightly better protection and you don’t ever actually pay the bad charges, which is why I opt for credit cards over debit cards when I can.

That’s not to say it’s fun to have your identity stolen, but that’s actually pretty rare.

On the other hand, the tracking issue is real, and is happening, and cash purchases will help but won’t be sufficient. Lots of tracking happens just by your phone usage, and even turning off your cell phone might not be enough, although you might like that feature if you lose your phone.

In other words, to get off the grid you’d need to use cash, leave your cell phone at home, and avoid the various cameras and sensors being placed everywhere. Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Will the bitcoin protocol disrupt investment banking? Does this finally imply a means for fairer banking practices without putting regular folks on the hook? Here’s a related article.

Quantifried in Canada

Dear Quantrified,

I haven’t read that article, but I’ll just go ahead and answer the question anyway: no. The reasons that regular folks are on the hook for crazy bets on things like mortgage backed securities is complicated, deep, and will not go away because of bitcoin.

I’m not sure where or how this mythology got started, but even if an alternative currency worked flawlessly – which bitcoin does not, by far – we’d still have deep ties to Wall Street, and we’d still be bailing them out if and when.

For one thing, people’s retirement savings are increasingly involved in the fate of the markets and the banks, and that’s not gonna change just because our cash system gets separated from bank fees.

Don’t get me wrong, I’d love the banks to have fewer ways to control their power, and part of their power definitely includes things like fees on international money transfers. Let’s free ourselves! Cool. But let’s not pretend that’s a panacea.

Plus it would be great if we could find an alternative currency where you get more money for saving energy, not for wasting it. Too much to ask?

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am friends with you on Facebook and I have recently got your book Doing Data Science on my kindle (to give you insight about our one sided relationship). There is more I want to say: with the inspiration and courage from you, I have quit my academic path in number theory.

I looked for jobs in the U.S.. However, a math Ph.D. was not good enough for the employers to jump on me. I now work as an evidence-based policy maker in science and technology matters in my home country.

However there are some problems. One is: I left a boy friend behind to get this job. Second: I do miss U.S., the wild nature, blue sky, fresh air and enough space for everyone. How can I be productive and still feel that I live in a beautiful world? The two notions does not seem to come together after quitting academia. Why is not U.S. more generous to let in people who would like to live there or let them look for jobs without time pressure?

No Acronym

Dear NA,

Holy crap, I don’t think I ever told anyone to be like me.

Here’s the thing, you never get rid of problems, you just exchange them for new problems. And your new problems sound pretty deep.

My suggestion for you is to understand your options – all of them – and make a plan to increase those options in the medium and long term so that you have a 5-year and 10-year plan to make your problems closer to your ideal set of problems.

I know that sounds vague, but I can’t help you much more than that because everyone’s ideal set of problems is different. Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am visiting U.S.A. from overseas. The guidebook says that a 15% to 20% gratuity based on the bill before sales taxes (with a minimum of 1$) should be given to staff of restaurants, taxis, salons etc. Are there other rounding conventions? And, is any of this discretionary according to customer’s appreciation of the service received?

I am from a country that has spent a generation (and indeed is still making efforts) to eradicate bribery and bring the informal economy into the realm of taxation, so it’s an awkward custom for me. I want to be respectful but prefer not to overpay due to ignorance.

Confused Foreign Visitor

Dear CFV,

First of all, it’s not bribery. These people depend on good tips for their salary. Waiting staff in restaurants have a minimum wage of $2.13, which is outrageous. They need those tips to survive.

I’m not saying it’s a great system, but it’s a system.

Second, your rules do not jibe with how I understand the rules of tipping. Here’s how I do it:

- For restaurant meals, I tip at least 1/6th of the cost of the food after tax. So if the bill with tax is $60 I pay $70.

- For taxies, I pay 10% for long trips and 15% or 20% for shorter trips.

- For delivery in my neighborhood, I pay the larger of $5 or 10% of the meal’s cost.

- For haircuts it really depends on the situation and whether the person listened to what I asked for. I give between between 10% and 25%. Then again I get about 1 haircut per year.

Good luck, and welcome to our country!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’m in the 5th or 6th year of long distance in an almost decade long relationship with my girlfriend. I love her very much and intend to marry her when we settle down eventually. When we’re together we have great sex.

Anyway, I’m a very horny guy. Oftentimes, my mind wanders off to very naughty things. If it wasn’t for my awesome girlfriend, I’d probably be a classic man slut. I’ve never cheated on her, nor have I ever been in a relationship with anyone else actually, but that doesn’t stop me from frequently checking out girls, dreaming of threesomes, and watching porn. Usually it doesn’t really get to me, because there are much more pressing problems in my life I have to deal with (e.g. career), but in moments when those problems get put on the backburner for one reason or another, it’s like my libido starts consuming me alive. I just really, really want to have sex with another girl.

Aunt Pythia, what should I do? What mental pep talk should I give myself in these moments of anguish? I love my girlfriend and want to be with her, but I’m just so goddamn horny.

Brandishing One Nasty Erection Rythmically

Dear BONER,

First, nice acronym.

Next, I’m pretty sure this is a fake question, but I’ma include it anyway because I’m desperate to juice up this rather tame column.

Why fake? Because, if you were really a man slut, and if you’re really long-distance for your 6th year, then you’re almost definitely 100% already having sex with other people.

I mean, I would be! WTF?! Who stays faithful for 6 years?

OK OK I know what you’re saying – you made an oath. I get that. But nobody – and I mean nobody – can be expected to live apart from their lover for that long. It’s just nuts. My personal opinion, and I can already sense the disgust and dismissal of some people upon reading this. I’m shallow and overly devoted to my cruder instincts, all true. But I also have a standard of decency and quality of life that includes regular physical contact.

My advice to you: start living with your future wife very very soon, or break up with her and get relief with a local. Or tell your GF that you need to take a lover, maybe you guys can work something out.

You asked.

Aunt Pythia

——

Please submit your well-specified, fun-loving, cleverly-abbreviated question to Aunt Pythia!

Intentionally misleading data from Scott Hodge of the Tax Foundation

Scott Hodge just came out with a column in the Wall Street Journal arguing that reducing income inequality is way too hard to consider. The title of his piece is Scott Hodge: Here’s What ‘Income Equality’ Would Look Like, and his basic argument is as follows.

First of all, the middle quintile already gets too much from the government as it stands. Second of all, we’d have to raise taxes to 74% for the top quintile to even stuff out. Clearly impossible, QED.

As to the first point, his argument, and his supporting data, is intentionally misleading, as I will explain below. As to his second point, he fails to mention that the top tax bracket has historically been much higher than 74%, even as recently as 1969, and the world didn’t end.

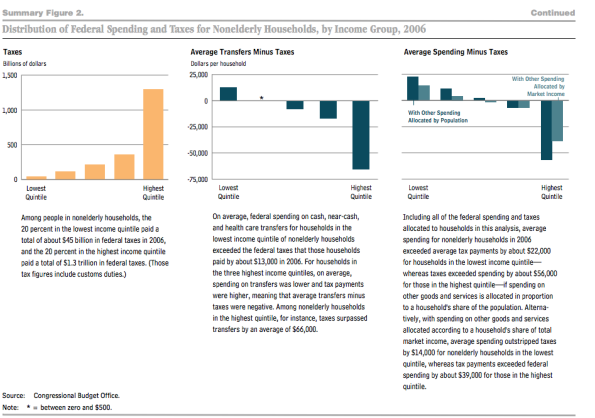

Hodge argues with data he took from a report from the CBO called The Distribution of Federal Spending and Taxes in 2006. This report distinguishes between transfers and spending. Here’s a chart to explain what that looks, before taxes are considered and by quintile, for non-elderly households (page 5 of the report):

The stuff on the left corresponds to stuff like food stamps. The stuff in the middle is stuff like Medicaid. The stuff on the right is stuff like wars.

Here are a few things to take from the above:

- There’s way more general spending going on than transfers.

- Transfers are very skewed towards the lowest quintile, as would be expected.

- If you look carefully at the right-most graph, the light green version gives you a way of visualizing of how much more money the top quintile has versus the rest.

Now let’s break this down a bit further to include taxes. This is a key chart that Hodge referred to from this report (page 6 of the report):

OK, so note that in the middle chart, for the middle quintile, people pay more in taxes than they receive in transfers. On the right chart, for the middle quintile, which includes all spending, the middle quintile is about even, depending on how you measure it.

Now let’s go to what Hodge says in his column (emphasis mine):

Looking at prerecession data for non-elderly households in 2006 in “The Distribution of Federal Spending and Taxes in 2006,” the CBO found that those in the bottom fifth, or quintile, of the income scale received $9.62 in federal spending for every $1 they paid in federal taxes of all kinds. This isn’t surprising, since people with low incomes pay little in taxes but receive a lot of transfers.

Nor is it surprising that households in the top fifth received 17 cents in federal spending for every $1 they paid in all federal taxes. High-income households hand over a disproportionate amount in taxes relative to what they get back in spending.

What is surprising is that the middle quintile—the middle class—also got more back from government than they paid in taxes. These households received $1.19 in government spending for every $1 they paid in federal taxes.

In the first paragraph Hodge intentionally conflates the concept of “transfers” and “spending”. He continues to do this for the next two paragraphs, and in the last sentence, it is easy to imagine a middle-quintile family paying $100 in taxes and receiving $119 in food stamps. This is of course not true at all.

What’s nuts about this is that it’s mathematically equivalent to complaining that half the population is below median intelligence. Duh.

Since we have a skewed distribution of incomes, and therefore a skewed distribution of tax receipts as well as transfers, then in the context of a completely balanced budget, we would expect the middle quintile – which has a below-mean average income – to pay slightly less than the government spends on them. It’s a mathematical fact as long as our federal tax system isn’t regressive, which it’s not.

In other words, this guy is just framing stuff in a “middle class is lazy and selfish, what could rich people possibly be expected do about that?” kind of way. Who is this guy anyway?

Turns out that Hodge is the President of the Tax Foundation, which touts itself as “nonpartisan” but which has gotten funding from Big Oil and the Koch brothers. I guess it’s fair to say he has an agenda.

Why is math research important?

As I’ve already described, I’m worried about the oncoming MOOC revolution and its effect on math research. To say it plainly, I think there will be major cuts in professional math jobs starting very soon, and I’ve even started to discourage young people from their plans to become math professors.

I’d like to start up a conversation – with the public, but starting in the mathematical community – about mathematics research funding and why it’s important.

I’d like to argue for math research as a public good which deserves to be publicly funded. But although I’m sure that we need to make that case, the more I think about it the less sure I am how to make that case. I’d like your help.

So remember, we’re making the case that continuing math research is a good idea for our society, and we should put up some money towards it, even though we have competing needs to fund other stuff too.

So it’s not enough to talk about how arithmetic helps people balance their checkbooks, say, since arithmetic is already widely known and not a topic of research.

And it’s also a different question from “Why should I study math?” which is a reasonable question from a student (with a very reasonable answer found for example here) but also not what I’m asking.

Just to be clear, let’s start our answers with “Continuing math research is important because…”.

Here’s what I got so far and also why I find the individual reasons less than compelling:

——

1) Continuing math research is important because incredibly useful concepts like cryptography and calculus and image and signal processing have and continue to come from mathematics and are helping people solve real-world problems.

This “math as tool” is absolutely true and probably the easiest way to go about making the case for math research. It’s a long-term project, we don’t know exactly what will come out next, or when, but if we follow the trend of “useful tools,” we trust that math will continue to produce for society.

After all, there’s a reason so many students take calculus and linear algebra for their majors. We could probably even put a dollar value on the knowledge they gain in such a class, which is more than one could probably say about classes in many other fields.

Perhaps we should go further – mathematics is omnipresent in the exact science. And although much of that math is basic stuff that’s been known for decades or centuries, there are probably many examples of techniques being used that would benefit from recent updates.

The problem I have with this answer is that no mathematician ever goes into math research because someday it might be useful for the real world. At least no mathematician I know. And although that wasn’t a requirement for my answers, it still strikes me as odd.

In other words, it’s an answer that, although utterly true, and one we should definitely use to make our case, will actually leave the math research community itself cold.

So where does that leave us? At least for me straight to the next reason:

2) Continuing math research is important because it is beautiful. It is an art form, and more than that, an ancient and collaborative art form, performed by an entire community. Seen in this light it is one of the crowning achievements of our civilization.

This answer allows us to compare math research directly with some other fields like philosophy or even writing or music, and we can feel like artisans, or at least craftspeople, and we can in some sense expect to be supported for the very reason they are, that our existence informs us on the most basic questions surrounding what it means to be human.

The problem I have with this is that, although it’s very true, and it’s what attracted me to math in the first place, it feels too elitist, in the following sense. If we mathematicians are performing a kind of art, like an enormous musical piece, then arguably it’s a musical piece that only we can hear.

Because let’s face it, most mathematics research – and I mean current math research, not stuff the Greeks did – is totally inaccessible to the average person. And so it’s kind of a stretch to be asking the public for support on something that they can’t appreciate directly.

3) Continuing math research is important because it trains people to think abstractly and to have a skeptical mindset.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: one of the most amazing things about mathematicians versus anyone else is that mathematicians – and other kinds of scientists – are trained to admit they’re wrong. This is just so freaking rare in the real world.

And I don’t mean they change their arguments slightly to acknowledge inconvenient truths. I mean that mathematicians, properly trained, are psyched to hear a mistake pointed out in their argument because it signifies progress. There’s no shame in being wrong – it’s an inevitable part of the process of learning.

I really love this answer but I’ll admit that there may be other ways to achieve this kind of abstract and principled mindset without having a fleet of thousands of math researchers. It’s perhaps too indirect as an answer.

——

So that’s what I’ve got. Please chime in if I’ve missed something, or if you have more to add to one of these.

Interview on Math-Frolic with Shecky Riemann

Crossposted from mathtango.

I’ve been reading Cathy O’Neil’s “Mathbabe” blog off-and-on pretty much since its inception, but either I’ve changed or her blog has, because for the last several months almost every entry seems like a gem to me. Cathy is somewhat outside-the-box of the typical math bloggers I follow… a blogger with a tad more ‘attitude’ and range of issues. She is a Harvard (PhD) graduate (also Berkeley and MIT) and a data scientist, who left the finance industry when disillusioned.

Political candidates often talk of having a “fire in the belly,” and that’s also the sense I’ve had of Cathy’s blog for awhile now. So I was very happy to learn more about the life of the blogosphere’s mathbabe, and think you will as well:

************************************

1) To start, could you tell readers a little about your diverse background and how you came to be a sort of math “freelancer” and blogger… including when did your interest in mathematics originally arise, and when did you know you wished to pursue it professionally?

I started liking math when I was 4 or 5. I remember thinking about which numbers could be divided into two equal parts and which couldn’t, and I also remember understanding about primes versus composites, and for that matter g.c.d., when I played with spirographs and taking note of different kinds of periodicities and when things overlap. Of course I didn’t have words for any of this at that point.

Later on in elementary school I got really into base 2 arithmetics in 3rd grade, and I was fascinated by the representation of the number 1 by 0.9999… in 7th grade. I was actually planning on becoming a pianist until I went to a math camp after 9th grade (HCSSiM), and ever since then I’ve known. In fact it was in that summer, when I turned 15, that I decided to become a math professor.

Long story short I spent the next 20 years achieving that goal, and then when I got there I realized it wasn’t the right speed for me. I went into finance in the Spring of 2007 and was there throughout the crisis. It opened my eyes to a lot of things that I’d been ignoring about the real world, and when I left finance in 2011 I decided to start a blog to expose some of the stuff I’d seen, and to explain it as well. I joined Occupy when it started and I’ve been an activist since then.

[Because so many carry the stereotyped image of a mathematician as someone standing at a blackboard writing inscrutable, abstract symbols, I think Cathy’s “activism” has been one of the most appealing aspects of her blog!]

2) You’re involved in quite a number of important activities/issues… what would you list as your most ardent (math-related) goals, for say the next year, and then also longer-term?

My short- or medium- term goal is to write a book called “Weapons of Math Destruction” which I recently sold to Random House. It’s for a general audience but I’ve been giving a kind of mathematical version of it to various math departments. The idea is that the modeling we’re seeing proliferate in all kinds of industries has a dark side and could be quite destructive. We need to stop blindly assuming that because it has a mathematical aspect to it that it should be considered objective or benign.

[…Love the title of the book.]

Longer term I want to promote the concept of open models, where the public has meaningful access to any models that are being used on them that are high impact and high stakes. So credit scoring models or Value-Added Teacher models are good examples of that kind of thing. I think it’s a crime that these models are opaque and yet have so much power over people’s lives. It’s like having secret laws.

3) Related to the above, you’ve been especially outspoken about various financial/banking issues and the “Occupy Wall Street” movement… I have to believe that there are both very rewarding and very frustrating/exasperating aspects to tackling those issues… care to comment?

I’d definitely say more rewarding than frustrating. Of course things don’t change overnight, especially when it comes to the public’s perception and understanding of complex issues. But I’ve seen a lot of change in the past 7 years around finance, and I expect to see more skepticism around the kind of modeling I worry about, especially in light of the NSA surveillance programs that people are up in arms over.

4) Your blog covers a wider diversity of topics than most “math” blogs. Sometimes your blogposts seem to be a combination of educating the public while also simultaneously, venting! (indeed your subheading hints at such)… how might you describe your feelings/attitude/mood when writing typical posts? And what are your favorite (math-related) subjects to write about or study?

Honestly blogging has crept into my daily schedule like a cup of coffee in the morning. It would be really hard for me to stop doing it. One way of thinking about it is that I’m naturally a person who gets kind of worked up about how people just don’t think about a subject X the right way, and if I don’t blog about those vents then they get stuck in my system and I can’t move past them. So maybe a better way of saying it is that getting my daily blog on is kind of like having an awesome poop. But then again maybe that’s too gross. Sorry if that’s too gross.

[Let’s just say that I may never think about composing blog posts in quite the same way again! 😉 ]

5) Is “Mathbabe” blog principally “a labor of love” or is it more than that for you (some sort of means to an end)? i.e., You’re writing a book and you do speaking engagements, along with other activities… is the blog a mechanism to help promote/sustain those other endeavors, or do you view it as just a recreational side activity?

I’ve been really happy with a decision to never let mathbabe be anything except fun for me. There’s no money involved at all, ever, and there never will be. Nobody pays me for anything, nobody gets paid for anything. I do it because I learn more quickly that way, and it forces me to organize my half-thoughts in a way that people can understand. And although the thinking and learning and discussions have made a bunch of things possible, I never had those goals until they just came to me.

At the same time I wouldn’t call it a side activity either. It’s more of a central activity in my life that has no other purpose than being itself.

6) Go ahead and tell us about the book you have in the works and its timetable…

It’s fun to write! I can’t believe people are willing to let me interview them! It won’t be out for a couple of years. At first I thought that was way too long but now I’m glad I have the time to do the research.

7) How do you select the topic you post about on any given day? And are there certain blogposts you’ve done that stand out as personal favorites or ones that were the most fun to work on? From the other side, which posts seem to have been most popular or attention-getting with readers?

I send myself emails with ideas. Then I wake up in the morning and look at my notes and decide which issue is exciting me or infuriating me the most.

I have different audiences that get excited about different things. The math education community is fun, they have a LOT to say on comments. People seem to like Aunt Pythia but nobody comments — I think it’s a guilty pleasure.

[Yes, I was skeptical of Aunt Pythia when you announced it (seemed a bit of a stretch), but it too is a fun read… though I most enjoy the passionate posts about issues tangential to mathematics.]

I guess it’s fair to say that people like it when I combine venting with strong political views and argumentation. My most-viewed post ever was when I complained about Nate Silver’s book.

8) What are some of the math-related books you’ve most enjoyed reading and/or ones you would particularly recommend to lay folks?

I don’t read very many math books to be honest. I’ve always enjoyed talking math with people more than reading about it.

But I have been reading a lot of mathish books in preparation for my writing. For example, I really enjoyed “How to Lie with Statistics” which I read recently and blogged about.

Most of the time I kind of hate books written about modeling, to be honest, because usually they are written by people who are big data cheerleaders. I guess the best counterexamples of that would be “The Filter Bubble,” by Eli Pariser which is great and is a kind of prequel to my book, and “Super Sad True Love Story” by Gary Shteyngart which is a dystopian sci-fi novel that isn’t actually technical but has amazing prescience with respect to the kind of modeling and surveillance — and for that matter political unrest — that I think about all the time.

9) Anything else you’d want to say to a captive audience of math-lovers, that you haven’t covered above?

Math is awesome!

[INDEED!]

************************************

Thanks so much, Cathy, for filling in a bit about yourself here. Good luck in all your endeavors!

Cathy tweets, BTW, at @mathbabedotorg and she did this fascinating interview for PBS’s “Frontline” in 2012 (largely on the financial crisis):

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/oral-history/financial-crisis/cathy-oneil/

(I highly recommend this!)

Interview with Bill McCallum, lead writer of Math Common Core

This is an interview I had on 2/4/2014 with Bill McCallum, who is a University Distinguished Professor of Mathematics and member of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Arizona. Bill also led the Work Team which recently wrote the Mathematics Common Core State Standards, and was graciously willing to let me interview him on that.

Q: Tell me about how the Common Core State Standards Mathematics Work Team got formed and how you got onto it.

A: There were actually two separate documents and two separate processes, and people often get confused between them.

The first part happened in the summer of 2009 and produced a document called “College and Career Readiness Standards“. It didn’t go grade by grade but rather described what a high school student leaving and ready for college and career looks like. The team that wrote that pre-cursor document consisted of people from the College Board, ACT, and Achieve and was organized and managed by CCSSO (which represents state education commissioners and the like) and NGA (which represents Governors). Gene Wilhout, then executive director of CCSSO, led the charge.

I was on that first panel representing Achieve. Achieve does not write assessments, but College Board and ACT do, and I think that’s where the charge that the standards were developed by testing companies comes from. It’s worth noting in the context of that charge that both ACT and College Board are non-profits.

The second part of the process, called the Work Team, took that document and worked backwards to create the actual Common Core State Standards for mathematics. I was the chair of the Work Team and was one of the 3 lead writers, the other two being Jason Zimba and Phil Daro. But the other members of the Work Team represent many educators, mathematicians, and math education folks, as well as DOE folks, and importantly there are no testing or textbook companies represented. The full list is here.

Q: Explain what Achieve is and is not.

A: Achieve is not a testing company, so let’s put that to rest.

Without going into too much historical detail (some of which is available here), Achieve was launched as an initiative of a combination of business and education leaders with the goal to improve education. It’s a non-profit think tank, which came out with benchmarks for mathematics education and tried to get states to align standards to them.

I started working with Achieve around 2005 and pretty soon I found myself chairing a committee to revise the benchmarks, which is how I got involved in the drafting of the first document I talked about above.

One more word about getting states on board with the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). There were 48 states that had committed to being involved in the writing, but not necessarily to adopt the standards. The states were involved in the review process as the CCSS were being written in 2009-2010. And here by “states” we usually mean teams from the various Department of Education, but different states had different team makeups.

For example, Arizona heavily involved teachers and some other states had their mathematics specialists at the DOE look things over and make comments.The American Federation of Teachers took the review quite seriously, and Jason and I met twice over the weekend to talk to teams of teachers assembled by AFT, listening to comments and making revisions.The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics was also quite involved in reviews and meetings.

Q: What are the goals of CCSS?

A: The goal is educational: to describe the mathematical achievements, skills, and understandings that we want students to have by the time they leave high school, broken down by grades.

It’s important to note at this point that this is not a new idea. Indeed states have had standards since the early 1990’s. But those standards were pretty unfocused and incoherent in many cases. What’s new is that we have common standards, and that they are focused and coherent.

Q: So what’s the difference between standards and tests?