Big data, technology, and the elderly

The last time I visited my in-laws in Holland, I noticed my father-in-law, who is hard of hearing, was having serious trouble communicating with his wife. My husband was able to communicate with his father by patiently writing things on a piece of paper and waiting for him to write back, but his mother doesn’t have that patience or the motor control to do that.

But here’s the thing. We have technology that could help them communicate with each other. Why not have the mother-in-law speak to an iPad, or Siri, or some other voice-recognition software, and then that transcription could be sent to her husband? And he could, in turn, use a touch screen or his voice to communicate back to her.

This is just one simple example, but it made me wonder what the world of technology and big data is doing for elderly, and more generally for people with specific limited faculties.

There was a recent New York Times article that investigated so-called “Silver Tech,” and it painted a pretty dire picture: most of the tools being developed are essentially surveillance devices, monitors to allow caregivers more freedom. They had ways of monitoring urine in diapers, open refrigerators, blood sugar, or falls. They often failed or had too much set-up time. And more generally, the wearables industry is ignoring people who might actually benefit from their use.

I’m more interested in tools for older people to use that would make their lives more interactive, not merely so that they can be safely left alone for longer periods of time. And there have been tools made specifically for older people to use, but they are often too difficult to use or to charge or even to turn off and on. They don’t seem to be designed with the end-user in mind very often.

Of course, I should be the first person to point out that there’s a corner of the big data industry that’s already hard at work thinking about the elderly, but it’s in the realm of predatory consumer offers; specifically tailoring ads and services that prey on confused older people, with the help of data warehousing companies like Acxiom selling lists of names, addresses, and email addresses with names like “Suffering Seniors” and “Aching and Ailing” for 15 cents per person.

I know we talk about the Boomers too much, but let me just say: the Boomers are retiring, and they won’t want their quality of life to be diminished to the daytime soap opera watching that my grandmother put up with. They’re going to want iPads that help them stay in touch with their kids and each other. We should make that work.

And as the world lives longer, we’ll have more and more people who are perfectly healthy in all sorts of ways except one or two, and who could really benefit from some thoughtful and non-predatory technology solution. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Aunt Pythia is very excited to announce that she’s discovered her new career, thanks to her dear friend Becky Jaffe who sent her this video the other day:

That’s right, readers! Aunt Pythia has always wanted to be one of those “crazy old purple ladies” – although with dogs instead of cats – but she’s felt just too darn ridiculous to go it alone. Luckily, there’s a group of like-minded grannies whose goal is “the enhancement of the ridiculous.” Right on, right on. I’m wondering if I’m too young to qualify.

I have a feeling there are more people out there interested in this. Contact me and we’ll form a local chapter.

And now, on to business! Let’s go quickly to the part of Saturday morning where Aunt Pythia spouts nonsense to anyone who will listen, shall we? Homemade oatmeal chocolate chip cookies are on the dish, help yourself. Yes, that’s right, I said oatmeal and chocolate chip. There’s no fucking law against that.

After the cookies and advice, please don’t hesitate to:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dearest Aunt Pythia,

I have been trying on and off for almost a year to enter the word “binner” into Urban Dictionary, but it is always rejected! I’m at my wits’ end!

Below is my submission:

Binner: The inner erection of the clitoris that females get when aroused; the inner boner.

The part of the clitoris, the clitoral glans, that is seen on the outside of the body is only one piece of the clit, and it’s got all the nerve endings. However, the rest of the clit extends down into the body and is made of erectile tissue.

This part of the clitoris fills with as much blood as a penis does when males get erections, so it can be thought of as the inner boner or the “binner.”

Example the first: I got such a binner watching those smokin’ hot dudes playing beach volleyball.

Example the second: I can’t really think right now because my raging binner’s sucked all the blood from my brain.

Can you help?!?!

Blue Binnered in Indy

P.S. Hi Aunt Pythia! I’m Trisha Borowicz, one of the directors of Science, Sex and the Ladies. My web analytics led me to your post about the movie trailer. I stayed to read because you got some pretty cool, feminist, mathy shit going on here, and I just couldn’t resist asking Aunt Pythia a question. Anyway, thanks for writing about my trailer. Oh – and my question is absolutely true…and when I went to my original post about it, I see that it has been 2 years and probably about 5 tries.

——

Dear Blue,

Holy crap, that’s an awesome word. And we needed one for that. Next can you come up with a word for a mistress that’s a man? I’m thinking you’re gonna go with “manstress.” I can’t believe I didn’t think of that until now. You have inspired me.

I guess my only question about binners is this: how do we know if we’ve got one? I mean, I’m sure I get binners all the time but don’t know it, right? It’s not as obvious for us ladies is all. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Maybe that’s the missing ingredient in the submission?

Another possibility is that lots of different people have submit similar definitions for them to believe it’s really a word? What do you think, readers? Is this a great way to spend your Saturday mornings, or is it the best way to spend your Saturday mornings?

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What I love about mathematics is an amazing feeling of understanding what precisely someone meant, deciphering dense texts, capturing the idea someone tried to convey by an accidentally misleading example. Solving problems is not so enjoyable, but they help in the long run. The research is the worst. It’s so hard, and the results are usually boring compared to beautiful ideas already existing in the literature.

I am a PhD student at one of the top US universities, so I’ve done some research, somewhat successively, but didn’t enjoy it. I am fairly confident that I can finish my current program and eventually become a mediocre mathematician and maybe discover something awesome once or twice in my life.

Doing research to get a job and teaching calculus for thirty years is not a wonderful future, but it’s also not so bad. Am I ruining my life by sticking to this plan?

Most other careers also look bad for me in the same way. Everywhere from politics to videogames the core of success is the ability to extract information which exists, but wasn’t intentionally put there. Finding hidden patterns in the data, reading against the grain, applying ideas outside of their usual domain. All of this I don’t enjoy.

I am noticeably better than most other people at figuring what the creator of the information wanted me to understand from it. This skill sometimes help, but usually is absolutely pointless. Maybe personal relations benefit from it, but I’m not great at them for different reasons.

Should I just grow up more and accept that the world wasn’t designed to be enjoyable? But then I look at my friends who seem to really love doing original work and consider learning from books to be boring but necessary activity, and I feel that maybe I just have a different system of thinking. One where you don’t do awesome stuff and don’t earn millions, but instead, I dunno, have an inherent property of coolness in your soul. Or something. I usually avoid thinking about that. Sorry for such a long letter and a striking example of a “first world problem”.

Rather Educated Although Dumb

Dear READ,

I’m going to rephrase what I hear you saying. You love learning math, you are good with working stuff out that you know to be true, but you dislike working hard on something that might not end up being true.

So the payoff – that moment of clarity – is joyous, but the stuff leading up to it is painful for you. Without knowing more about why it’s painful, I can only guess. Here’s a list:

- You are anxious that you won’t ever discover the truth, and the anxiety gets in the way of enjoying anything.

- You choose problems that are too hard and so you go into the process unprepared.

- You postpone the process because of your dread and then you never feel like you have the mental space to think straight.

- You feel like other people have an easier time with not understanding math and it makes you feel bad in comparison because it’s hard.

- You are simply impatient.

I am just throwing around ideas here. I actually have no idea what is going on for you. Even so, I have a few thoughts.

First, part of me wants to tell you to look around and imagine you left math altogether. Then what? What do you think you’d want to do? Don’t think about it as a career for the rest of your life type of thing, but rather a project you’d embark on. What project do you think is cool? Work on that one. Give yourself space to choose; if not every project, at least some of them.

Next, I’d advise you to be realistic in the following sense. There is no perfect job. You can quit one job, or one career, and then start a new one, and you’d still have problems. Take it from someone who knows. Right now I’ve got an awesome consulting gig, doing a project I totally care about and I think is important, but even so I feel like a hustler, because being an independent consultant makes you a hustler.

Finally, I’d suggest that doing research requires patience, and a certain dose of humility, and a lack of caring about other people. These are all things that you can work on. But at the same time, there are fields in which the results are faster and easier and are still important. Data science is a faster, easier field than algebraic number theory. Projects go faster, people care about minor advances, and so on. On the other hand, the questions you answer weren’t asked by Diophantus. So there’s a trade-off too.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I am a young male professor in computer science. Being closer in age to postdocs and PhD students than other faculty, I find myself, especially at conferences, hanging out with them, going out in the evening, and so on.

While these kind of circumstances often lead to encounters and hookups, I have always been careful not to hook up with anyone, as I feel the differential of power and the scarcity of women in our field make it somewhat problematic for faculty to hook up with students (I am also in a monogamish long-time relationship, but that would not be a problem neither for me or my long time partner).

About two years ago, I found myself having a great connection with a PhD student at a conference (she studies in a different country, so I only see her at international meetings, but our fields have some overlap). We ended up talking all the time, and spent a lot of time together, nothing romantic being on the table.

Since then, every time we have seen each other, we have had incredible chemistry and end up going out a lot, in a group or not. This has been going on for a bunch of conferences now. I have no intention of acting on the situation, both because I feel it would ruin our relationship, and because I am afraid it would be detrimental to her career (though I am fairly certain we both feel very strongly about the other).

However, I am always very excited to see her each time there is a chance, and we both want to talk all the time, etc. As a consequence, I strongly suspect lots of people assume that we are indeed hooking up. I don’t want to be part of the creepy atmosphere that make it harder to be a woman in computer science, and I don’t want her reputation to be hurt by the situation, if people assume she is sleeping with older faculty. On the other hand, I really feel I am doing nothing wrong here! What should I do ?

Becoming the patriarchy

Dear Becoming,

You’re doing nothing wrong, they’re all jealous. Please enjoy each other.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

As a man approaching middle age and managing people in their twenties in the tech world, I often find that I just relate better to a lot of the men. We share common interests (sports, similar sense of humor) and I am just more comfortable asking them to grab the occasional drink in a one-on-one situation.

I can’t help wondering what some of the women in my group feel about this. Would they be grateful that I am leaving them alone, or resentful of the extra bonding their male colleagues get? I do regular meetings with the women, and take them out to coffee once in a while, but the guys get that extra, less guarded time.

It also makes my job more fun, as I like drinking and socializing with tech nerds. I think I am being fair when it comes to review time, but that could be a delusion on my part. I can also see that even if it was true, it may not be perceived as true .

I think the women on the team are funny, smart people too, and I would probably enjoy the occasional drink with them as well. It just feels weird to ask them to join me for a drink. I have no such problem with female colleagues, where there is no power imbalance in the relationship. What do I do?

Mature Intelligent Man Or Sexist Asshole

——

Dear MIMOSA,

Oh. My. God. I want a mimosa. With you. Right now.

OK, so I have no problem drinking with men. I’ve always done it, and I don’t think it’s weird. In fact I love it. Alcohol has the magical ability to help people find common interests. You don’t need to know what they are in advance. You don’t even need to drink alcohol; just being in a bar, ready to engage in a real conversation with another person, is enough. I think you should try it. Here are two suggestions.

First, ask a friendly, open-minded young woman you manage by saying something like, “Hey I sometimes have drinks after work with Tom or Jim, and I’m wondering if you’d like to join me one of these days? I’d love to get a chance to talk in a relaxed manner. It doesn’t have to be after work, and it doesn’t have to involve alcohol, but it could. What do you think?

Once you’ve done it with her, it will be easy for the other women to think of it as super normal.

If that seems weird – which I don’t think it is – then I’d suggest invited a small group of people for drinks and making sure the group involved one or two women. Like, make it a celebration of a project getting done or something.

The caveat is that women – and men of course – may have family duties with young children. For that reason, please never make it a spontaneous after-work drink event, or make it required. Always give people advance warning, at least 3 or 4 days, so they can arrange things.

And please have a drink for me next time!

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers? Aunt Pythia loves you so much. She wants to hear from you – she needs to hear from you – and then tell you what for in a most indulgent way. Will you help her do that?

Please, pleeeeease ask her a question. She will take it seriously and answer it if she can.

Click here for a form for later or just do it now:

No, let’s not go easier on white collar criminals

We all know the minimum sentencing laws for drug violations are nuts in this country. Combined with “broken windows” policing, those laws have sent entire generations of minority men to jail. We need criminal justice reform badly.

But one version of the bipartisan effort to address this issue, called H.R.4002 and backed by the Koch brothers, goes too far in a big way. In particular, it extends to white-collar crime and it insists that the defendant in a Federal criminal case “acted with intent.”

The entire bill is here, you can read it for yourself. Concentrate on Section 11, where it state:

if the offense consists of conduct that a reasonable person in the same or similar circumstances would not know, or would not have reason to believe, was unlawful, the Government must prove that the defendant knew, or had reason to believe, the conduct was unlawful.

Here’s why I am particularly aggravated about this. In writing my book I’ve been researching the way corporations rely on algorithms which are often unfair and discriminatory. Sometimes that unfairness is unintentional, but often it’s simply careless. In my book I’m calling for people to hold themselves and the algorithms accountable.

One of the trickiest things about the current state of affairs is that nobody in particular understands the algorithms they are using. They think of them, in a way, as “the voice of God.” Actually it’s more like “the voice of science,” because they are assumed to be scientific and objective. But in any case nobody interrogates them or their consequences, however unreasonable. Under this new law, there’d be no criminal charges against anyone, ever, who used such arbitrary tools.

I’d go further, in fact. If this law were on the books, there’d be every incentive in the world for corporations to hide tricky or criminal decisions in algorithms just for the reason that afterwards they would be able to say they didn’t know about it, and thus had no criminal intent. It would be an invitation for obfuscation. Such algorithms would be just the thing to introduce to allay litigation risk.

Have you noticed a lot of people going to jail for their part in mortgage fraud? Neither have I. We don’t actually need a new law that would make it harder for white-collar criminals to do time. We already live in a 2-tiered justice system; let’s not make it even worse.

There’s a Occupy the SEC petition that you can sign urging Congress to oppose this bill. It’s here. Please think about signing.

Uncollected Criminal Justice Data

This morning I was happy to stumble upon a new whitepaper put out on the Data & Civil Rights webpage entitled Open Data, the Criminal Justice System, and the Police Data Initiative and written by Robyn Caplan, Alex Rosenblat, and danah boyd.

The content concerns the White House initiative, which I am tangentially part of, to encourage police departments to “open up” more of their data. Ideally that would mean more information on crime rates, even though such data is often unreliable, because police departments are assessed on the basis of violent crime rates. Even more aspirationally, that would mean better data on how police officers and citizens interact on a daily basis.

But here’s the thing. You can’t open up data that you don’t collect. And for most precincts, they don’t collect that level of data. That’s my biggest takeaway of the whitepaper, and it was also the theme of a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at an “open data” conference I spoke at.

In other words, we are starting too downstream. When we ask police departments to “open up” their data, we are assuming they collect the data we want. But they only collect the data that makes them look efficient or successful. Other data collection efforts have failed because they are entirely voluntary.

So, it’s pretty well known that we don’t have a high-quality national register of fatal police shootings, and the Guardian has a better one. But the problems don’t end there. We also don’t generally speaking know whether the public of a given precinct trusts their cops. That’s also uncollected data. We also have little information on what the conditions are for people who have been arrested.

Here’s what I’d like to see: high-quality data on the conditions at Rikers, beyond the surveillance video that the public has no access to. I volunteer to do the data analysis for free. I’m not holding my breath, though: they cannot even be trusted to count inmate fights.

Big Data community, please don’t leave underrepresented students behind

This is a guest post by Nii Attoh-Okine, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Director of Big Data Center at the University of Delaware. Nii, originally from Ghana, does research in Resilience Engineering and Data Science. His new book, Resilience Engineering: Models and Analysis will be out in December 2016 with Cambridge Press. Nii is also working on a second book, Big Data and Differential Privacy: Analysis Strategies for Railway Track Engineering, which will be out Fall 2016 with John Wiley & Sons.

Big data has been a major revolutionary area of research in the last few years—although one may argue that the name change has created at least part of the hype. Only time will tell how much. In any case, with all the opportunities, hype, and advancement, it is very clear that underrepresented minority students are virtually missing in the big data revolution.

What do I mean? The big data revolution is addressing and tackling issues within the banking, engineering and technology, health and medical sciences, social sciences, humanities, music, and fashion industries, among others. But visit conferences, seminars, and other activities related to big data: underrepresented minority students are missing.

At a recent Strata and Hadoop conference in New York, one of the premier big data events, it was very disappointing and even alarming that underrepresented minority students (participants and presenters) were virtually nonexistent. The logical question that comes to mind is whether the big data community is not reaching out to underrepresented minority students or if underrepresented minority students are not reaching out to the big data community.

To address the importance of addressing and tackling the issues, there are a two critical facts to know, the first on the supply side, the other on the demand side:

- The demographics of the US population are undergoing a dramatic shift. Minority groups underrepresented in STEM fields will soon make up the majority of school-age children in the states (Frey, 2012). This means that currently underrepresented minorities are a rich pool of STEM talent, if we figure out how to tap into it.

- “‘Human resource inputs are a critical component to our scientific enterprise. We look to scientists for creative sparks to expand our knowledge base and deepen our understanding of natural and social phenomena. Their contributions provide the basis for technological advances that improve our productivity and the quality of lives. It is not surprising, therefore, that concern about the adequacy of the talent pool, both in number and quality, is a hardy perennial that appears regularly as an important policy issue.’ This statement, borrowed from Pearson and Fechter’s book, Who will Do Science?: Educating the Next Generation, remains a topic of serious debate” (A. James Hicks, Ph.D., NSF/LSAMP Program Director).

The issue at large is how the big data community can involve the underrepresented minority students. On that front I have some suggestions. The big data community can:

- Develop ‘invested mentors’ from the big data community who show a genuine interest in advising underrepresented minority students about big data.

- Forge partnerships with colleges and universities, especially minority-serving institutions.

- Identify professors who have genuine interest in working with underrepresented students in big data related research.

- Invite some students and researchers from underrepresented minorities to big data conferences and workshops.

- Attend and organize information sessions during conferences oriented toward underrepresented minority students.

The major advice to the big data community is this: please do make the effort to engage and include underrepresented minority students because there is so much talent within this group.

Math and the caveman imagination

This is a guest post by Ernie Davis Professor of Computer Science at NYU. Ernie has a BS in Math from MIT (1977) and a PhD in Computer Science from Yale (1984). He does research in artificial intelligence, knowledge representation, and automated commonsense reasoning. He and his father, Philip Davis, are editors of Mathematics, Substance and Surmise: Views on the Ontology and Meaning of Mathematics, published just last week by Springer.

We hear often that our cognitive limitations and our social and psychological flaws are due to our evolutionary heritage. Supposedly, the characteristics of minds and our psyches reflect the conditions in the primordial savannah or caves and therefore are not a good fit to the very different conditions of the 21st century.

The conditions of our primordial ancestors have been blamed for political conservativism, for religious belief , for vengefulness, and especially – since the subject is so fraught and so enjoyable – for gender differences, particularly in sexual fidelity. These kinds of theories have been extensively criticized, most notably by Steven Jay Gould, as being often “just-so” stories. You find a feature of the human mind that you dislike, or one that you think is an ineradicable part of human nature, and you make up a story about why it was good for the cavemen. You find a feature that some people have and others don’t, like political conservatism, and you explain that the stupid bad guys have inherited it from the cavemen, but that the smart good guys have overcome it. I gave my own opinions of the theories about conservatism and religion here.

This week, our ancestors are the fall guys for the fact that we find math difficult. In this week’s New Yorker, Brian Greene is quoted as saying, “[Math] is not what our brains evolved to do. Our brains evolved to survive in the wilderness. You didn’t have to take exponentials or use imaginary numbers in order to avoid that lion or that tiger or to catch that bison for dinner. So the brain is not wired, literally, to do the kinds of things that we now want it to do.”

The problem with this explanation is that it doesn’t explain. The question is not “Why is math hard in an absolute sense?” That’s hardly even a meaningful question. The question is “Why is math (for many people)particularly hard and unpleasant?”; that is to say, harder than a lot of other cognitive tasks. Saying that math is hard because it was useless for avoiding lions and catching bison doesn’t answer the question, because there are many other tasks that were equally useless but are easy and pleasant for people: reading novels, singing songs, looking at pictures, pretending, telling jokes, talking nonsense, dreaming. Nor can the comparative hardness of math be explained in terms of inherent computational complexity; if our experience with artificial intelligence is any indication, doing basic mathematics is much easier computationally than understanding stories. Until we have a much better understanding of how the mind carries out these various cognitive tasks, no explanation of why one task is harder than another can possibly hold much water.*

Conversely, our cognitive apparatus has all kinds of characteristics that, one has to suppose, were unhelpful for primitive people: our working memory is limited in size, our long-term memory is error-prone, we are susceptible to all manner of cognitive illusions and psychological illnesses, we are easily distracted and misled, we are lousy at three-dimensional mental rotation, our languages have any number of bizarre features. We find it harder to communicate distance and direction than bees; we find it harder to navigate long distances than migratory birds. Granted, imaginary numbers would have been useless in primitive life, but other forms of math which would probably have been useful, such as three-dimensional geometry, are also difficult.

Also, our distant ancestors should not be underestimated. The quotation from Greene seem to reflect Hobbes’ view that primitive life was “poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. These are, after all, the people from whom we inherit number systems, art, and language. They did not spend all their time escaping from lions and hunting bison.

Our ancestors on the savannah saw parabolic motion whenever they threw a stone; they experienced spherical geometry whenever they looked up at the starry sky. They never encountered a magic wand or a magic ring. Nonetheless, most people find it easier and much more enjoyable to read and remember and discuss four volumes of intricate tales about magic rings or seven about magic wands than to read a few dozen pages with basic information about parabolas; and even most mathematicians find spherical geometry unappealing and difficult. Why? We have absolutely no idea.

* “I well remember something that Francis Crick said to me many years ago, … ‘Why do you evolutionists always try to identify the value of something before you know how it’s made?’ At the time I dismissed this comment … Now, having wrestled with the question of adaptation for many years, I understand the wisdom of Crick’s remark. If all structures had a `why’ framed in terms of adaptation, then my original dismissal would be justified for we would know that “whys” exist whether or not we had elucidated the “how”. But I am now convinced that many structures … have no direct adaptational ‘why’. And we discover this by studying pathways of genetics and development — or, as Crick so rightly said to me, by first understanding how a structure is built. In other words, we must first establish ‘how’ in order to know whether or now we should be asking ‘why’ at all.” — Steven Jay Gould, “Male Nipples and Clitoral Ripples”, in Bully for Brontosaurus 1991.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

Readers, Aunt Pythia must apologize. She was taken over last weekend with the intense urge to craft. This is a coping mechanism of hers which takes over in times of stress, and the Paris attacks combined with anything Trump says, ever, overwhelmed her for about a week and it started last weekend. The good news is she got her project done:

It’s a baby blanket for my friend Adrian’s new baby. The design is here.

It’s reversible. Except for the name.

As for yesterday, Aunt Pythia had family over and was whipping up 5 dozen pancakes. Forgot to take pictures of them, but there were a lot of bananas and chocolate chips involved.

Anyhoo, that’s the explanation, but rest assured she has recovered and has emerged from her craft cave that exists inside the head. She is here for you and wants nothing more than to listen to your questions and give her half-reasoned and pseudo-sound advice. Before that, though, a small interruption.

Public Service Announcement: Reading Aunt Pythia has been known to improve mental and physical health, if only because it keeps you away from Thanksgiving leftovers for a few extra minutes. This effect is not statistically significant. I repeat, not statistically significant. This has been a Public Service Announcement brought to you by state and local authorities. In the event of an actual emergency, this announcement would not be helpful. I repeat, unhelpful.

If, after reading the below, you want to waste even more time, please don’t hesitate to:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

I’d like to tell you an anecdote, one that is both mortifying and instructive. I offer it in the hope that it will elicit some thoughtful discussion from you, and from your other readers.

I am a male mathematician of a certain age. About twenty years ago, in my capacity as a member of a journal editorial board, I received a paper to handle. The author, a European, was nobody I had heard of. I took a look at the paper and decided that it was not up to the journal’s standards. The theorem was correct, but I could explain it to myself quickly using standard ideas in a routine way, by arguments simpler than those in the paper.

So without sending it to a referee I wrote a polite rejection letter explaining my reasons. From the author’s name, I assumed she was a woman. In fact he was a man.

I learned this about ten years later, when I happened to meet him at a small international conference. I don’t believe that either of us acknowledged the fact that our paths had crossed long ago. Several embarrassing thoughts flew into my head. Had he received a rejection letter starting “Dear Ms ____”? I would like to think that I knew enough back then to write “Dear Professor ____” or “Dear Dr ____”. Maybe I did.

But the thing that really made me squirm was that, as soon as I learned that she was a he, it came to me in a flash that I had written the letter in a sexist frame of mind. Imagining that I was writing to a woman, probably a struggling new-fledged female PhD, I had adopted a condescending tone that I don’t think I would have taken with a struggling new-fledged male PhD.

I can’t say for sure whether the air of condescension would have been obvious to the reader, but it was certainly there in my head. If I couldn’t see my own sexism in that case until this chance discovery made it apparent, how can I guard against similar attitudes when I’m teaching, or writing a reference letter, or reading a job application or a grad school application?

Baffling, Our Own Biases, Yes?

Dear BOOBY?,

I get it. I’m like that too. In fact women are just as sexist as men. I often find myself wondering if I spoke too condescendingly to women. I sometimes wish I could “play back the tape,” as it were, from old conversations so that I could apologize when appropriate.

But of course, you can’t do that in a conversation, because we don’t record conversations, or for that matter take any other anti-bias steps for real-world interactions. On the other hand, we can and should for formal situations like submitting papers.

Here’s a very concrete suggestion: Make it a rule that you obscure the name of every article that comes in to every journal, and that at least one referee sees each one. This way you, who saw the name before it was obscured, will not be tempted to immediately dismiss articles written by women. And as a happy by-product you won’t have to fret later on about your own sexist impulses, which again we all have.

Maybe you can arrange for someone else to do the obscuring-of-the-names process so you can look at the papers yourself. Maybe you could arrange with another editor to obscure their names in return for them obscuring yours. Whatever. Do what it takes to make it a blind audition.

I’d like to add that, whenever possible, do this for grad school applications and job applications as well. I know it’s hard for job applicants, because they are known personally at that level, but try to put processes into place that at least mitigate this kind of thing.

Good luck, and please know that once this system is in place you will have accomplished way more than you are now by kicking yourself needlessly and fruitlessly.

Aunt Pythia

——

Aunt Pythia,

My wife, her sister and I are all in our late 40’s and empty nesters. My sister-in-law, Naomi, is divorced and currently between boyfriends. As a result, she usually shows up at our place Saturday mornings. She and my wife, Allison, go shopping or to an art exhibit or other places, returning to our house in the late afternoon. They both shower and get dressed and then the three of us go out for dinner and other activities. I’ve edited some of the conversation below to make it more coherent.

Allison showers in the master bath and Naomi in the guest bath. They both come to the double sink in the master bath to fix their makeup, do their hair, and talk. I’ve taken to joining them because they both primp while wrapped in bath towels and I’m hoping for a flash. Allison will usually oblige pretending to need to get something from the under sink. She bends over keeping her legs straight. Then she’ll straighten up and smirk at me.

Several weeks ago Allison was alone in front of her sink when I came in. She smelled so fresh that I couldn’t resist. I knelt in front of her, put a hand behind her thigh for balance, pulled down her towel, and licked her nipples. All of a sudden Naomi showed up. Allison was trapped.

“Ronnie, don’t embarrass Naomi!”

I took one more lick of each nipple making sure Naomi could see my tongue flicking each bud. I stood up.

“Sorry, sometimes I get carried away,” I said to Naomi.

“Looked like fun,” Naomi replied. “I wish I had someone to do that to me.”

The minor exhibitionism revved me up. That night I was harder than I had been in a long time. Allison was hot also. She had a couple of orgasms.

Since that Saturday night had gone so well, I decided to try the same thing the next week. When I walked into our bedroom Allison was naked and still drying off. Unfortunately Naomi was already there. My disappointment showed.

“Aww, no sugar tits this week, Ron,” Naomi said and laughed.

The following week I pulled down Allison’s towel before Naomi showed up. Allison was moaning when Naomi walked in on us.

“Ronnie, stop Naomi’s here.” But she didn’t push me away.

“Yeah, Ron. You’re making me jealous.”

I took one last long lick to make sure Naomi saw.

“Doesn’t your sister have nice breasts?” I cupped one of Allison’s breasts and turned to Naomi.

“Mine are bigger.” Naomi pulled her towel down for about three seconds before covering up again.

That night Allison was all over me as soon as Naomi left.

“Did you like seeing my slut sister’s big boobs?” I was sucking Allison’s breasts so it took me a few seconds to reply.

“They’re okay.”

“Don’t bullshit a bullshitter. I saw the way your eyes bugged out when she flashed you.”

“Honey, I’ve told you before, anything over a mouthful is wasted.”

“So you would waste a lot if you sucked her boobs?”

“I guess so.” After that the conversation waned as I moved lower on her body.

We all felt a certain excitement the next Saturday when the girls got ready for their showers.

Allison was still drying off when I caught her out of the shower. This time as I lowered my lips to her nipples I slipped the hand that I used to balance on the back of her thigh up higher until my fingers were against her sex.

“You be good if Naomi comes in. Don’t embarrass me.” Naomi showed up a minute later.

“Don’t you two ever get enough?” I licked both nipples before raising my head and looking at Allison.

“If Naomi is going to watch us each week, don’t you think she ought to show us something?”

“Yeah, Sis. Show us your boobs again.” I dropped my head back down and watched out of the corner of my eye as Naomi lowered her towel to her waist. After about fifteen seconds I raised my head again.

“Do you think she wants her nipples licked?”

“Sis, do you want Ronnie to lick your nipples?” Allison moaned. Then she spread her legs farther apart. My index finger slipped between her moistening lips.

Naomi didn’t reply, but she drifted over beside me. I turned my head and put my other hand on the back of Naomi ‘s thigh to balance. Of course that hand slipped higher to touch between her legs. I moved my mouth to her nearest nipple. As I sucked, Naomi spread her legs a little. I extended my finger upward. After about five minutes of switching back and forth and tonguing four nipples, I was about to explode.

“Ronnie, we need to finish getting ready for dinner.”

“Yeah, Ron, I bet you’re hungry,” Naomi added hoarsely.

I got up reluctantly.

That night I was licking between Allison’s legs.

“Do you think Naomi would like it if I licked her clit?” I asked as I stopped briefly.

“My sister’s such a slut. I bet she would give you a blowjob and swallow if you licked her clit. But maybe you shouldn’t get confused about which sister you’re married to.” With that she dug her fingernails into my shoulder hard enough to hurt. “Get back to my clit.

So, here’s my question. Is my wife giving me permission to steal third base or is she calling me out and sending me to the dugout?

Wants to Smell the Roses but Afraid of the Thorns

Dear WrStRbAotT,

First of all, I want to thank you for your letter. I appreciate the work you put into it, I really do. It’s obvious what you put yourself through on Aunt Pythia’s behalf, and she appreciates it.

Second of all, I don’t have a sister, but if I did, I am pretty sure I’d never want to be sexual with her or in her presence. I mean, I have a brother, so I know how I feel about that kind of thing, and I’m pretty sure sisters are similar. Even so, it seems like – and I’m generalizing from Happy Days and Fonzie, but who doesn’t – it seems like this is a common enough male fantasy.

I guess to probe just a bit on this topic, how would you react if I talked about having sex with you and your brother at the same time? Would that turn you on? I doubt it. Just saying.

In answer to your question, I think your wife has been giving you mixed signals, and maybe you should take that as a sign of ambivalence, or maybe she’s just saving the best for the next chapter, if you will.

To sum up: I’d definitely let her take the lead if I were you. If she wants you to do the nasty with her sister, believe me, she’ll tell you to. Or maybe show you how (cough).

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

About seventeen years ago when I was a grad student I was in the computer room of a national science facility analyzing my data. The only other person there was a fellow grad student analyzing her data when her thesis supervisor came in the room and started to sexually assault her.

Without thinking, I pulled him away from her and dragged him to my desk where I said “here are those plots which I mentioned before” which is true because a few hours earlier I was talking to him about that data. He looked quite livid, but said nothing and left the room.

The grad student was stunned and left the room. Neither of us said anything either then or later. I have not seen XXXXXX (AP: name redacted) for at least ten years. The recent news about the sexual harassment case at Berkeley has made me think of these memories after so many years of not wanting to think of them. I have also started wondering whether what I did really made a difference in her life and so I have thought of contacting her directly and asking that question.

There is no question in my mind that what I did was the right thing, yet somehow it would be nice to get some sort of acknowledgment. Do you think contacting her and asking her whether what I did made any kind of difference in her life be a good idea and if so, how would you word it ?

Old Memories Arise Again

Dear OMAA,

Hmm. I’m thinking, you maybe didn’t do the wrong thing, but I don’t think I’d characterize it as “the perfect thing”. That’s not to blame you at all, because I think your intuition was good, and you definitely defused the situation. But I’m wondering if the internal conflict you’re feeling might arise from the fact that you could have done more. In short, you diverted him but you didn’t keep him from trying it again.

The problem with diversion, as a technique, is that it doesn’t address the underlying issue, and it doesn’t call it out as fucked up. It simply avoids it in a short-term way. So for example, there’s no reason to think that your colleague ever felt safe going back to that computer lab to do work again, even if she got a new advisor.

So, if you’re wondering what you’d do if that situation came up again, I’d suggest 1) telling him he’s doing something illegal while he’s doing it, 2) telling your colleague she has every right to call the police, and 3) calling the police yourself in front of both of them. That way he gets the message, and even if he ends up thinking he did nothing wrong, which is typical in this kind of situation, at least he’s been through enough that he doesn’t think doing it again is worth it. Introduce serious friction into his predatory ways, in other words, and it will at least slow him down, and at best get him fired.

As far as contacting her, I don’t think you should, especially with your current expectation of “acknowledgement” for “doing the right thing.” If I were that woman, I’d kind of want to say, “why the fuck didn’t you speak up?” and I would definitely not appreciate it. If, on the other hand, you wanted to reach out and ask her what you should have done, and what would have helped her the most, then yeah, maybe that could fly. But it would have to be done carefully.

Finally, I think it’s strange that you’d say her name. Is that some kind of signal to me that this is a fake question? In that case, please don’t send me fake questions; better to say what you’re sending me is a hypothetical. Otherwise, I’m not clear on why you’d name the victim at all. Is it an unnecessary pseudonym? I don’t get it.

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

What do you think of the heartbreaking story of Anna Stubblefield – to me it reads like a Shakespearean tragedy: brave woman leaves her white cis-male husband for a differently-abled man of color, but instead of being praised she is arrested and send to prison on ridiculous charges without any evidence.

LIM

Dear LIM,

Wow. Seriously?

Anna Stubblefield is super nuts. Yes, in a tragic way, but still. The best thing I can say about her is that she’s nuts and I don’t think she had evil intentions. But she’s still nuts.

Otherwise said: people have an amazing ability to believe what they want to believe. I know this because I worked in finance and I get that Lloyd Blankfein was not joking when he said that Goldman Sachs was “doing God’s work.” For reals some people are true believers, and they are the scariest people around.

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers? Aunt Pythia loves you so much. She wants to hear from you – she needs to hear from you – and then tell you what for in a most indulgent way. Will you help her do that?

Please, pleeeeease ask her a question. She will take it seriously and answer it if she can.

Click here for a form for later or just do it now:

What are you thankful for in finance or economics?

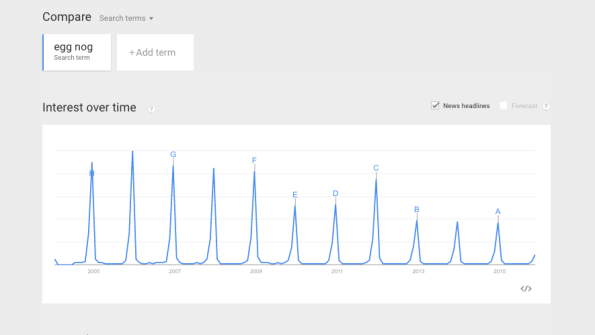

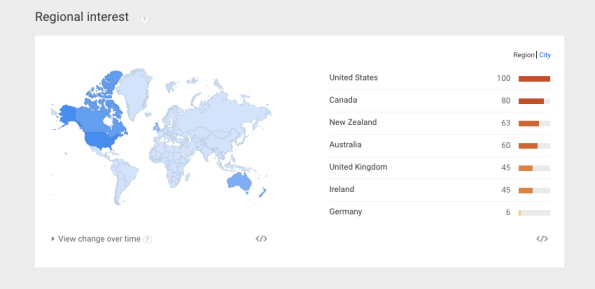

It’s been a few days, I’ve been listening to Adele’s new album pretty much on loop while knitting and sewing curtains. So yes, it’s that nesting time of year, where we hunker down and seriously consume creamy spiked drinks.

And by “we” I mean Americans, Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders. Obviously we blame the hobbits on that last one.

Well, here’s a question for you nog-quaffers: what are you thankful for from finance? I’ll extend it to the economy as well if you’d like.

The reason I’m asking is that this week, the Slate Money podcast I’m on is doing a special “thanksgiving” episode where we all talk about something we’re grateful for, and I’m having trouble coming up with something. Here’s what I’ve got so far:

- I’m grateful for consumer loans. After all, they help us out in rough times and allow us to invest in ourselves and our futures through mortgages and student loans. On the other hand, they also raise the price of everything through their availability. In fact I spent a couple of weeks ago on the show arguing that all college debt should be forgiven and that state colleges should be free. So I don’t think this works.

- I guess I’m thankful for inflation, in a sense. I mean, inflation makes it easier on debtors, since their debt is constantly dwindling in value, and it’s certainly better for an economy than deflation. But on the other hand, it can get out of hand and that’s bad, and it’s hard to control. So in the end I’m not actually all that excited by inflation.

- I could just be grateful for the entire financial system working at all. If you think about how much we depend on its functioning, to take out loans, to use our credit and debit cards, and to get paid monthly, it’s kind of amazing. On the other hand, if you think about the way finance deals with poor people, squeezing them for nickels and dimes, then you kind of lose respect. In fact it makes you want to be grateful for the CFPB instead, but that’s not financial enough.

- Finally, I’m thinking about how much I appreciate insurance. Yeah, I know there are plenty of problems with insurance (for example how cray-cray medical prices are for those without insurance, but I tend to blame a lack of reasonable transparency regulation on pricing in medicine on that, not insurance per se). But if you just think about how much insurance actually does for us, whether it’s medical or fire or car or life insurance, then you appreciate that it more or less functions as intended: to even out the bumpy risks of everyday life.

I’m still thinking about this question, and I’d love to hear your ideas!

Do Charter Schools Cherrypick Students?

Yesterday I looked into quantitatively measuring the rumor I’ve been hearing for years, namely that charter schools cherrypick students – get rid of troublesome ones, keep well-behaved ones, and so on.

Here are two pieces of anecdotal evidence. There was a “Got To Go” list of students at one charter school in the Success Academy network. These were troublesome kids that the school was pushing out.

Also, I recently learned that Success Academy doesn’t accept new kids after the fourth grade. Their reasoning is that older kids wouldn’t be able to catch up with the rest of the kids, but on the other hand it also means that kids kicked out of one school will never land there. This is another form of selection.

Now that I’ve said my two examples I realize they both come from Success Academy. There really aren’t that many of them, as you can see on this map, but they are a politically potent force in the charter school movement.

Also, to be clear, I am not against charter schools as a concept. I love the idea of experimentation, and to the extent that charter schools perform experiments that can inform how public schools run, that’s interesting and worthwhile.

Anyhoo, let’s get to the analysis. I got my data from this DOE website, down at the bottom where I clicked “citywide results” and grabbed the following excel file:

With that data, I built an iPython Notebook which is on github here so you can take a look, reproduce my results with the above data (I removed the first line after turning it in to a csv file), or do more.

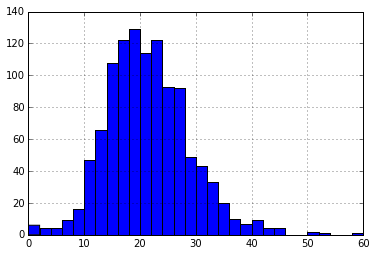

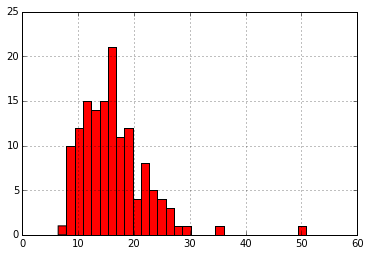

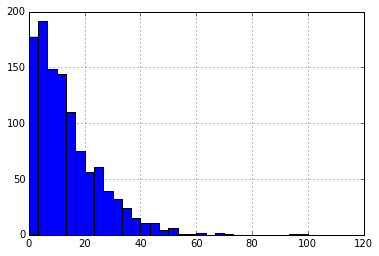

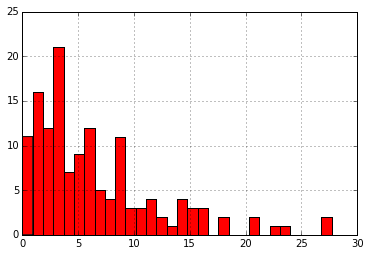

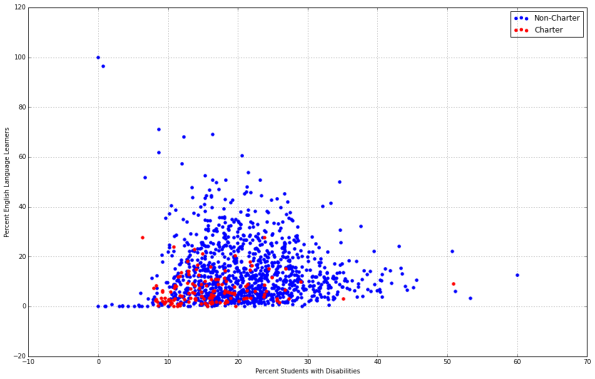

From talking to friends of mine who run NYC schools, I learned of two proxies for difficult students. One is ‘Percent Students with Disabilities’ and the other is ‘Percent English Language Learners’ (I also learned that charter schools’ DBN code starts with 84). Equipped with that information, I was able to build the following histograms:

Percent Students with Disabilities, non-Charter

Percent Students with Disabilities, Charter

Percent English Language Learners, non-Charter

Percent English Language Learners, Charter. Please note that the x-axis differs from above.

I also computed statistics which you can look at on the iPython notebook. Finally, I put it all together with a single scatterplot:

The blue dots to the left and all the way down on the x-axis are mostly test schools and “screened” schools, which are actually constructed to cherrypick their students.

The main conclusion of this analysis is to say that, generally speaking, charter schools don’t have as many kids with disabilities or poor language skills, and so when we compare their performance to non-charter schools, we need to somehow take this into account.

A final caveat: we can see just by looking at the above scatter plot that there are plenty of charter schools that are well inside the middle of the blue cloud. So this is not a indictment on any specific charter school, but rather a statistical statement about wanting to compare apples to apples.

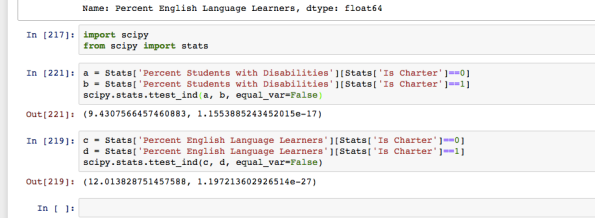

Update: I’ve now added t-tests to test the hypothesis that this data comes from the same distribution. The answer is no.

Those very small numbers are the p-values which are much smaller than 0.05. Other t-tests give similar results (but go ahead and try them yourself)

Line Edits

Right now I’m eyeball deep in line edits for my book, Weapons of Math Destruction: how big data increases inequality and threatens democracy.

Or rather, I’m in the phase of minor(ish) edits from my editor (post-existential threats, anyway, and that’s a big deal!) which is before the next phase, where I’ll be dealing with issues from the actual line editor, the person who knows all about commas and what gets italicized versus quoted and so forth.

Then come the galleys, and along the way of course I help choose a cover design. After that the blurbs start (who should I ask?) and they print a bunch of copies in China and have it all shipped back here by boat. The process takes months and it’s all new to me.

Point is, my brain is completely occupied with this stuff, which is the opposite of sexy but on the other hand is exactly why the book will be better (hopefully!) than a blog – it will be actually carefully edited.

Everyone, fingers crossed, but the tentative launch date is September 5th of 2016. I know, it’s forever from now, but at least it’s an actual date. I’m already planning the party.

Open Data Conference this Friday

I’m going to be on a panel Friday at a conference called Responsible Use of Open Data in Government and the Private Sector, which is being co-organized by Berkeley and NYU and is being held at NYU this Thursday evening and Friday all day.

The agenda is here. The first keynote, on Thursday night, is to be given by the Chief Analytics Officer of New York City, who I’m interested to hear from. I’m wondering what de Blasio’s administration is up to with respect to data and predictive modeling.

I’m going to miss Panel 2 because of my podcast taping, which is a shame, but I’m looking forward to Panel 1 which will discuss consequences of data sharing, unintended as well as intended: privacy concerns, discrimination concerns, and so on.

I’m on Panel 3, which with Panel 4 is devoted to the topic of private data use and collection versus the public good. The focus is on health care data and smart cities, but I will probably veer off to all kinds of ways that private companies use data to the detriment of the public, and how that should change.

Panel 5 discusses platforms for sharing data as well as the proposed governance of shared data. To be honest I’m a bit skeptical of the concept I’ve heard floated about recently that private companies will “donate” their data for the public good, but I’d love to be wrong.

Registration is free and open and available here.

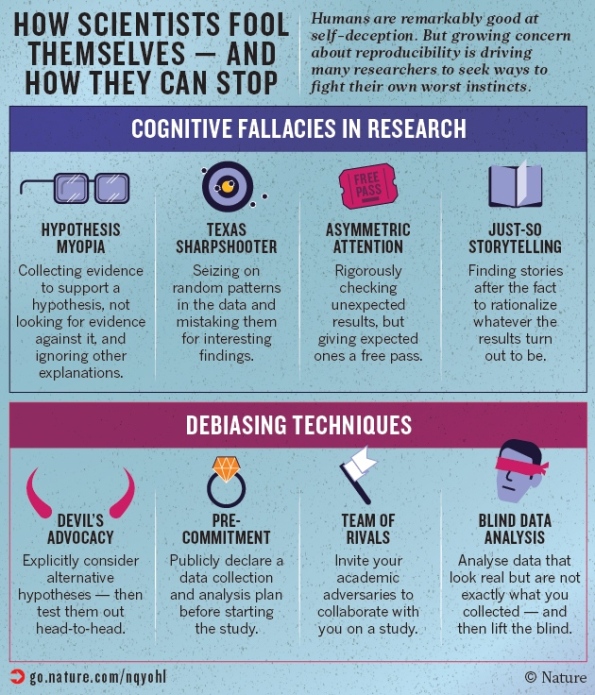

Debiasing techniques in science

My buddy Ernie Davis just sent me an article, published in Nature, called How scientists fool themselves – and how they can stop. It’s really pretty great – a list of ways scientists fool themselves, essentially through cognitive biases, and another list of ways they can try to get around those biases.

There’s even an accompanying graphic which summarizes the piece:

I’ve actually never heard of “blind data analysis” before, but I think it’s an interesting idea. However, it’s not clear how it would exactly work in a typical data science situation, where you perform exploratory data analysis to see what the data looks like, and you form a “story” based on that.

One thing they mentioned in the article but not in the graphic is the importance of having your research open sourced, which I think is the way to let the “devil’s advocacy” and “team of rivals” approaches actually happen in practice.

It’s all the rage nowadays to have meta analyses. I’d love for someone to somehow measure the ability of the above debiasing techniques to see which work well, and under what circumstances.

Aunt Pythia’s advice

It’s a crisp autumn morning, and Aunt Pythia is deeply enjoying snuggling into her La-Z-Boy whilst wearing her cottony and fluffy hoodie, and she’s looking forward to a good long chat. She’s drinking coffee but she’s willing to make you tea if that’s your preference. In any case, make yourself comfortable, Aunt Pythia has some explaining to do.

Confession the first: recently Aunt Pythia has been going on somewhat of a craft binge. She’s taken to sewing lined curtains for her New York apartment, and the learning curve for someone who has never successfully done more than seam pants is steep. So far one prototype, a lopsided affair that looks much more 1970’s than she had envisioned. Stay tuned for updates, but please also make it your plan to sympathize with uneven hemming and puckers for a little while. Solidarity, people.

Also! Aunt Pythia readers, another confession/ brag. About a month ago Aunt Pythia received an email requesting her presence for an underwear modeling shoot, and she said yes (exact quote from CEO Julie at the shoot: “nobody has ever said yes that quickly. Most women have a million questions.”). It’s safe to say, dear readers, that the only question Aunt Pythia had about the underwear modeling gig was, why did it take you so long to ask me?

Two reasons this story might matter to you: first, you can check out the pictures here – please note Aunt Pythia’s hair goes with her shirt – and second, you can get an “Aunt Pythia discount” on Dear Kate underwear for women by using the discount code AuntPythia30, good through November 30th.

Now that all has been revealed! Aunt Pythia is getting on with the important stuff: your problems, ethical dilemmas, and general questions. Let’s do this, people! And after we do that, please don’t forget to:

ask Aunt Pythia any question at all at the bottom of the page!

By the way, if you don’t know what the hell Aunt Pythia is talking about, go here for past advice columns and here for an explanation of the name Pythia.

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

In light of the discussion started by “Woman not at a bar”, I’ve been thinking about what women say about where it is OK to express romantic and sexual interest. I have been repeatedly told that men shouldn’t approach women they don’t know, because that shows that they only care about her looks.

Also, that a man shouldn’t approach a woman at a recreational activity (sports team, crafts, class, etc), because if she says no she might feel uncomfortable or scared and feel forced to drop out of the activity. One shouldn’t approach a woman at work, because that implies not taking her seriously as a professional. And approaching a close friend risks ruining the friendship.

All of these make sense to me individually, and if a woman says that something makes her uncomfortable I believe her, but they don’t seem to leave much room. Sometimes people tell me to wait for a woman to show clear signs of interest before making a move, but that seems to mean waiting forever (twice in the last ten years for me; one was a student in a class I was teaching, and the other one turned out not to be interested after all).

So is there any way to approach a woman that doesn’t make her feel threatened if she isn’t interested? And if not, perhaps it’s time for women to switch to making the first move as a rule?

A Single Heterosexual Adult Male Experiencing Distress

Dear ASHAMED,

You had me until the student in your class. I don’t think it’s ever ok to “make a move” on a student in your class. I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt and assume you meant you waited at least long enough so that she wasn’t a student anymore. That’s a requirement. But let’s put it aside. It’s over there, next to the sugar bowl.

Here’s the thing. I think you might have gotten bad advice, but I think it happened before your scrutiny of the situation set in.

Because yes, if you assume the set-up is, “I approach a woman, not knowing if she likes me at all, and I make my moves” then I agree, it’s really hard to know when that’s appropriate. In fact it might never be. But the good news is, that’s not how it actually works. Or at least I’ve never seen that approach work unless it’s at a bar or a party and everyone’s incredibly drunk and horny, and even then it often doesn’t work.

What actually works, IRL, is that you slowly orbit around someone that you’re interested in, and you pick up on positive feedback, and you test things out with the other person, and after a bit of back-and-forth, and some body language, and after she laughs at your jokes, and you laugh at hers, and after you both figure out how to spend more time together without making it seem like it’s on purpose, then you find yourselves “Interested” with a capital I. It’s a whole lot of very ambiguous, somewhat ambiguous, then not-so-ambiguous communication leading up to the first “move.”

It’s called flirting. It’s fun, and it’s the number one way you determine whether someone wants to date you. I suggest you practice doing it, because it’s basically a requirement for someone who wants to avoid the above misunderstandings.

Why do I say that? Because if you’re trying to find a girlfriend in your native environment, then yes, it’s generally speaking not appropriate unless the flirting has established it the two of you as “a possible thing.” You cannot abruptly “make a move” on someone you work with, or someone you play sports with, or someone on the streets you’ve never met, without seeming like a creep. You just can’t. And that’s because it is creepy, actually, and it’s creepy because there’s this technology called “flirting” which everyone knows about and is an expected and required lead-in to making a move. Think of flirting as a means of obtaining consent for a move.

Exceptions can be made in the following circumstances:

- You are being set up by mutual friends. So it’s already a date.

- You meet online at a dating website, so it’s already a date.

But even if the above things happen, and it’s “already a date,” I suggest you still diligently engage in the flirting phase anyway, because it’s still a great way of establishing mutual feedback, a non-creepy persona, and an atmosphere of lighthearted and sexy fun.

Wait, I hear you saying, how do I flirt so that it’s not creepy? How do I slowly but surely cross the spectrum from “friendly” to “sexy”?

So, when you encounter a woman you are attracted to, you are friendly, and you listen. You figure out what she likes, and what she likes about you. You do not think to yourself, “I am attracted to this women, when can I make a move?” but rather you think, “how do I know if she’s interested in me? what encouragement has she given me that she likes me, and what encouragement have I given her that I like her?”

Evidence of encouragement can be stuff like, in order of ambiguity (a very incomplete list!):

- she makes eye contact when you arrive and smiles

- she laughs at your jokes and asks you questions about yourself

- she touches your arm or hand when she talks to you

- she mentions she’s going somewhere and invites you to come along

- she sits on your lap and grinds

Flirting works kind of like a ladder, where you and the woman are both climbing it at the same time. If she is on the 4th rung, you should be on the 3rd, 4th, or 5th for you guys to stay close. If she goes one rung further than you, then you can keep up, and then even go one rung further yourself.

But by no means do you ever leave her behind on the ladder. Then she’d feel like, “Dude, I’m not keeping up with you, haven’t you noticed? Why aren’t you paying attention to where I am on this flirt ladder?” And you will come across as a creep. Creeps are people who aren’t paying attention to what the woman actually wants and are just barreling ahead based on what they want.

Does this all make sense? And, given this context, does it make sense that “making a move” on someone is almost always creepy? It’s basically like showing up at the top of the ladder. Maybe like stilts, except even less stable. And the woman is like, holy crap, you might fall right on top of my head and give me a concussion.

I hope this little story has helped. Now, go forth and flirt!

Love,

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Another blogger I read got confused by the same sort of Google traffic and looked into it. Apparently it’s not incest, it’s that in India and Pakistan the word “aunt” is used in porn searches for older women the way people here might use “MILF”.

The blogger in question realized that his searches were coming from people who misspelled “auntie fuck” as “anti faq” and wound up on his Anti-Libertarian FAQ. No kidding. So unfortunately, a column by Aunt Pythia that mentions sex or boobs is going to get those kind of visitors…

Absurdly Understood Naughty Terminology

Dear AUNT,

I’m not complaining! But thanks, I do feel a bit better about it now that it’s less incestuous.

Auntie P

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Would you mind pointing me in the direction of resources for women in math trying to figure out how to be thoughtful about what it means to be a woman in math? (In addition to your blog, of course!)

I am a fourth year statistics and economics student at UVA, and I find myself increasingly desirous of things to read to help me articulate and name and talk about the challenges of being a lady in the math department.

As I have spent more and more time in math, there have been things that have happened that have made me upset, and I have struggled to articulate *why*. For example: I went to office hours for my probability class – maybe ~75% male, with a male professor – and there were four of my male classmates there as well. I asked a question, and immediately all five men responded with some version of “that’s a dumb/obvious question” in a please-don’t-waste-our-time-tone. I explained that they had misunderstood my question, that my question was really X not Y, and the professor kinda sorta answered X.

I left, very upset at what had just happened, but not being able to quite articular why. It would be natural to be upset if five people in general shut down my question. But what about how it had been five *men* did I find particularly offensive/upsetting?

Another example: A few weeks ago one of my (female) friends withdrew from our stochastic processes class, which had 4 women out of 22 students. For me this was a painful things to watch, but I again, I had difficulty saying why. She was a math major and withdrawing wouldn’t change that.

What was wrong? Was it that it felt so avoidable, that if things had gone so slightly differently I knew she would have stayed (and so this wasn’t even about gender at all)? Was it that I’ve watched the number of women in my math classes decrease with every successive class I’ve taken, and here I was watching this war of attrition happen before my eyes? She’s happy, so why am I upset?

Another: Until this semester I have never had either a female professor or TA in any economics, statistics, math, or CS class. I’m a fourth year, so I’ve taken a lot of classes aka had lots of opportunity to have had a female instructor in my field. I have yet to successfully explain why that’s hard – not just philosophically too bad, but hard – to my friends. Or to successfully communicate *how* that hard-ness presents itself. Sometimes I think the things that upset me maybe shouldn’t upset me, or that I’m seeing ghosts where there are none.

That math is just really hard, and it’s hard and even lonely for everyone, and that men/everyone experiences the same thing. I don’t know how to respond to that devil’s advocate in my head, or how to think well about that either. I would love your advice on what to read and where to go to learn how to coherently articulate my thoughts and frustrations in this arena. Especially because I only have room in my schedule to take either abstract algebra or a feminism class next semester, and I would really like to take the math class AND have the intellectual resources to think well about these things.

Sincerely,

Woman Here In Math Seeking Intellectual & Constructive Assistance, Legitimately (WHIMSICAL)

Dear WHIMSICAL,

I don’t know whether to be offended that you needed to spell out your sign-off for me. I supposed I deserve it, sometimes in the past I’ve missed some really good ones. Apologies to all those Aunt Pythia contributors!!

Here’s the thing. I think you’re already miles ahead of where I was at your age, because of two things. First, you’ve figured out what’s bothering you. I remember not knowing why I was upset, but simply bursting out in tears every now and then. It was bewildering.

Second, you’ve found my blog! And I’m so glad about that! One of the major goals of my blog is to be here for you.

Now, here’s the bad news. I don’t really have too much in the way of concrete advice for you. I’ll do my best though, here goes:

- I’d also be sad to see that woman go, and I’d also be confused as to why. I feel that way whenever I see women leave math, even though I myself left. But of course I don’t regret that I left, and I’m much happier now, so it doesn’t make sense at the individual level to feel sorry for a woman who chose to do something else.

- Maybe we’re both just feeling bad for math’s culture itself, that it can’t seem to get itself together to be a welcoming place for all these wonderful women. I’m sorry for you, math culture. And I’m not sure you can hear me, or what you’d say if you could answer me, but believe me you’re missing out on some majorly wonderful people by being so difficult.

- Having said that, the underlying math, the actual math questions and riddles and puzzles, is awesome, and when it’s just you and it, and the rest of the culture is shut out, then it can be magical.

- About the men: they are dumb, immature, and asinine. Including the professor. But not everyone is like that. So my advice here is: seek out men and women who are not like that, and figure out how to do math with them.

- I remember being in Victor Guillemin‘s MIT math grad class on differential geometry. He is so nice, and the math was super beautiful. There was this really badly off man who would come to the class, maybe he was homeless, and he’d ask bizarre and unrelated questions. Guillemin would, without fail, figure out a way to turn it into a really good question and would quite gallantly and kindly answer it, ending with something sincere like, “thanks so much for asking that!” Love that guy, and love how consistently elegant he made that potentially disastrous situation.

- Which is to say, we all have something to strive for. In your story above, the least we could expect from the professor is an honest answer to the question he thought you were asking, and we didn’t even get that. Lame.

- So, my advice to you is, trade up. Spend time with the people who are closer to Guillemin and further away from those people. And if that’s momentarily impossible, make do but keep in mind that there are better ways to run a culture, and that when you’re in charge you’ll see to it that it does get better.

- So when you’re a professor, you will never ridicule a question because it might end up being much deeper than you expect and after all math is really hard and sometimes we have brain farts and that’s ok too. Make your worst case scenario that you never humiliate anyone or call into question their basic dignity, and you’ll be rising the level of discourse by a mile and a half.

- Find women in math, at conferences and whatnot, and make friends. A little commiseration goes a long way.

Good luck!

Aunt Pythia

——

Dear Aunt Pythia,

Four-plus years after #OWS, I find myself within sight of a reputable liberal arts degree in both Politics and Economics, facing an uncertain job-market just over the horizon. So far, I feel like I’ve chosen well, trying to make sense of the financial system through an interdisciplinary lens. I have read a lot of the post-crisis canon, in hopes of new directions to pursue. I found your blog years ago following the Frontline feature, and was struck by mathbabe’s candor (No one understands the ‘whole financial system’) and quantitative rigor. As for my own skills, I’m good at compiling and interpreting research, written exposition, and creative analysis. I have some training in econometrics, but it’s definitely not my forte. I’ve done a couple of legislative internships, but I’m more and more certain that I need to pivot to a finance-related position or institution.

Grad school seems a remote possibility for the future, but right now I want to chart a course in the direction of economic journalism or policy analysis. I have major qualms about finance’s ability to confront long-term risk and deliver sustainable growth. Someday, I’d love to contribute to a prominent publication or think-tank, and help to craft the financial reforms we urgently need. (Stop me, please, if you see more effective ways to intervene for someone with my background). If you see fit, I am eager to hear which organizations you think are making the most progress, or what roles a newly-minted grad could hope to play therein.

So far, I’ve researched numerous SRI/ESG-based firms, government regulators (especially those agencies empowered by Dodd-Frank), industry monitors like FINRA, and even mission-oriented banks, CDFIs, B-corp lenders, and the like. I have yet to explore consulting or other professional services in as much depth. Is there a phylum that I’m neglecting here? Do you have any specific suggestions? I also wonder: if you or others in the Alt-Banking community knew as undergrads what you knew now, what organizations or roles would you have striven for?

Thanks for your consideration.

Curious About Robust Economic Empowerment & Risk Strategies

Dear CAREERS,

Thanks for the question. It’s a tricky one. One of the things that finance successfully does as a field is to make itself seem impenetrable for people not on the inside. At the same time, it’s an absolute requirement of a working modern economy. So there you have it, only insiders can penetrate and understand it, it has to exist and be healthy, and yet insiders are often corrupt (even when they don’t know they are).

So part of me doesn’t want you to go into field at all, because it kind of stinks. But on the other hand, the other effect that’s making things worse is that only money-grubbing jerks ever do go in. So, in the name of not wanting the field to be entirely overwhelmed by such people, I will in fact encourage you to go in, keeping your eyes open of course.

What I suggest is to get a job at a big bank and think of it as a sociological experiment, a la Karen Ho’s Liquidated. Then maybe go work for regulators or something. Honestly I know it sounds terrible – I’m suggesting you be part of the revolving door problem, but I don’t think it makes sense to be a financial regulator without actually having experience in finance.

Readers, weigh in if you have other ideas for CAREERS.

Good luck, and keep in touch!

Aunt Pythia

——

Readers? Aunt Pythia loves you so much. She wants to hear from you – she needs to hear from you – and then tell you what for in a most indulgent way. Will you help her do that?

Please, pleeeeease ask her a question. She will take it seriously and answer it if she can.

Click here for a form for later or just do it now:

Silicon Valley and Journalism conference at Columbia’s Tow Center

Today I’m excited to attend a Tow Center Journalism Conference on the relationship between Silicon Valley and journalism. Unfortunately it’s sold out at this point, but here’s the updated schedule.

Republicans would let car dealers continue racist practices undeterred

There’s an upcoming House Bill, HR1737, that would make it easier for auto dealers to get away with being racist. It’s being supported by Republicans* and is being voted on in the next couple of weeks. We should fight against it.

The issue centers on the problematic practice of “dealer markups,” discretionary fees that brokers slap on after the credit risk of a given borrower has been established. It turns out that these fees vary in size and are consistently bigger for blacks and Hispanics. Which means that if a number of people of different races but a similar credit history walk into a car dealership and buy a car, the minorities will typically end up paying more. This is illegal discrimination under the legal tool called the theory of “disparate impact.”

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has been making a valiant effort to hold accountable the financiers behind these loans. For political (read: lobbying) reasons the CFPB doesn’t have regulating power over auto dealers directly, but they do regulate the bankers that supply the money, and they’ve been nailing those bankers for unfair practices. For example, there’s an ongoing case against Ally Financial for upwards of $80 million, which would go to compensating the victims.

Here’s the amazing thing: Ally Financial doesn’t claim their loans weren’t racist. They simply claim that they were less racist than the CFPB thinks, and that the methodology that the CFPB used to measure the racism is flawed. The Republicans agree, and they’re trying to remove the CFPB’s ability to enforce disparate impact violations altogether**.

So, just to recap, the Republican argument is: if you can’t specify exactly how racist this practice is, then you can’t stop people from doing it at all. It’s a dumb and dangerous argument. It is, in fact, exactly what disparate impact was meant to avoid.