Archive

A rising tide lifts which boats?

My friend Jordan Ellenberg has a really excellent blog post over at Quomodocumque, which is one of my favorite blogs in that it combines hard-core math nerdiness with funny observations about how much the Baltimore Orioles stink (among other things).

In his post he talks about an anti-#OWS article called “The Occupy movement has it all wrong”, by Larry Kaufman, recently published in a Madison, WI newspaper called Isthmus.

Specifically, in that article, Kaufman tries to use the old saying “a rising tide lifts all boats” to argue that most people (in fact, 81% of them) are better off than their parents were. What’s awesome about Jordan is that he goes to the source, a Scott Winship article, and susses out the extent to which that figure is true. Turns out it’s kind of true with a certain way of weighting numbers depending on how many kids there are in the family and because so many women have started working in the past 40 years. Jordan’s conclusion:

So yes: almost all present adults have more money than their parents did. And how did they accomplish this? By having one or two kids instead of three or four, and by sending both parents to work outside the home. Now it can’t be denied that a society in which most familes have two income-earning parents, and the business-hours care of young children is outsourced to daycare and preschool, is more productive from the economic point of view. And I, who grew up with a single sibling and two working parents and went to plenty of preschool, find it downright wholesome. But it is not the kind of development political conservatives typically celebrate.

Another thing that Jordan tears apart from the article is that the original source specifically pointed out stuff that Kaufman seems to have missed, given his political agenda:

Winship also emphasizes the finding that children in Canada and Western Europe have an easier time moving out of poverty than Americans do. This part is absent from Kaufmann’s piece. Maybe he didn’t have the space. Maybe it’s because a comparison with higher-tax economies would make some trouble for his confident conclusion: “the punitive redistribution policies favored by Occupy Madison will divert capital away from productive initiatives that enhance growth and earnings opportunities for all, while doing nothing to build the stable families and “bottom-up” capabilities that are particularly important for helping the poorest Americans escape poverty.”

When the Isthmus is running a more doctrinaire GOP line on poverty than the National Review, the alternative press has arrived at a very strange place indeed.

Go, Jordan!

Let’s go back to that phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats”. It was the basis of Kaufman’s argument, and as Jordan points out was a pretty weak basis, in that the lift was arguable gotten only through sacrifice. But my question is, is that a valid argument to make anyway?

Let’s examine this metaphor a bit. When we think about it positively, and imagine something like the housing bubble which elevated many people’s net worth (ignoring the people who weren’t home owners at all during that time), we can see why “a rising tide lifts all boats” is a good thing: we want the generic imaginary person to do well, and we’re all happy for them to do well.

However, if we turn that phrase around in a negative moment, it’s really not clearly a good perspective. Let’s try it: “an ebbing tide lowers all boats”. Take the example of a housing crash analogously to the above. Firstly it’s not true, since for those people who couldn’t afford housing in the bubble, a more reasonable housing market is a good thing (for some reason people keep forgetting this). Secondly, when we are thinking about lowered boats we worry about those people whose boats are lowered. Who are those people? How much have they lost? Will they be okay?

The answers are, they are the people who were barely able to own the house in the good times. They’ve lost everything. They aren’t okay.

It’s a nearly vapid phrase when you think about it, but it’s used by conservatives a lot to justify policies that only work well in good times.

I’d argue that the real question we should be asking isn’t whether we are all sailing away in boats but how much risk we take on as individuals. I will go into this further in another post, but the gist is that, instead of the unit of measurement being assumed to be dollars, I’d like to reframe the concept of economic health in terms of a unit of risk. Risk is harder to measure than dollars, and there are lots of different kinds of risk, but even so it’s a worthy exercise.

For example, in the housing boom we had people who could barely afford a house get into ridiculous mortgage contracts, with resetting usurious interest rates. They were taking on enormous amounts of risk, in this case risk of being foreclosed on and losing their home. By contrast, people who were well-off at the start of the housing boom are for the most part still well off. There was very little risk for them.

I’d like to offer up an alternative phrase which would capture the risk perspective. Something like, “we should make sure everyone’s boats are water tight and firmly moored to the pier”. Not nearly as catchy, I know. But to make for it I’m linking to this related video called I’m On a Boat. I’ve actually been looking for excuses to link to this for a while. Here’s a kind of awesome picture from the video:

What up, New York Times? (#OWS)

There have been people complaining about the #OWS coverage by the New York Times, saying that it’s dismissive and slanted, generally not reporting enough and, when it does report, looking at things from the perspective of the Bloomberg administration.

I have tried to reserve judgment, although I did notice that the day of the 2-month anniversary of the occupation (a few days after Bloomberg cleared the park), where there were lots of actions and the big march, the NYT didn’t seem to cover anything in the morning at all, whereas the WSJ had live coverage of the hundreds of people trying to close down the exchange and disrupt the morning bell.

And I’m not sure if it’s the reporters or the editors who are responsible for the slanted coverage. It’s sometimes hard to tell.

Except sometimes. Here’s an article about Occupy Frankfurt from two days ago, in which a peaceful protest with a supportive police force is described:

“If all demonstrations went so well we wouldn’t have much to do,” said Michael Jenisch, a spokesman for the Frankfurt Ordnungsamt, or Office of Public Order, which issues permits for public gatherings and has been monitoring the Occupy Frankfurt encampment.

“If they have the staying power, they can camp there all winter,” Mr. Jenisch said. That attitude contrasts with that of the authorities in cities like New York, Oakland or Boston, where the police have evicted protesters from public space, and also with other financial centers in Europe.

That’s all fine, but here’s where I find the coverage outrageous. The article was not on the virtual front page; instead there was a link to the article from the front page, and the teaser line was:

Unlike at other Occupy sites, the Frankfurt protesters are being careful to make their points without inciting police interference.

What? Seriously??

I can’t tell you how often I was down at Zucotti, wondering why there were so many cops there, wasting our tax payer money, when the protesters were so incredibly peaceful. Who incited police interference? Was it the sleeping protesters in tents?

The message is not for protesters, on how to incite police aggression. The message here is for American cops, on how to deal with peaceful protesters. New York Times editors, did you even read your own article?

Where is Volcker’s letter? (#OWS)

At the Alternative Banking working group we are working on publicly commenting on the proposed Volcker Rule. Check out this blog post which addresses the exemption for repos. Keeping in mind that repos brought down MF Global a few weeks ago, this is a hot topic.

Here’s another hot topic, at least to me. Who has a copy of Volcker’s original 3-page letter? The published rumor has it that he wrote a 3-page letter to Obama outlining the goal of the regulation, but I can’t find it anywhere. I do have this quote from Volcker about the proposed 550 page behemoth (taken from a New York Times article):

“I’d write a much simpler bill. I’d love to see a four-page bill that bans proprietary trading and makes the board and chief executive responsible for compliance. And I’d have strong regulators. If the banks didn’t comply with the spirit of the bill, they’d go after them.” – Volcker

Also from the New York Times, a column of Simon Johnson’s on the Volcker rule and what it’s missing.

If anyone knows how to get their hands on the original letter, please tell me, I’d really love to see it. Maybe someone knows Volcker and can just ask him for a copy?

Meritocracy and horizon bias

I read this article yesterday about racism in Silicon Valley. It’s interesting, written by an interesting guy named Eric Ries, and it touches on stuff I’ve thought about like stereotype threat and the idea that diverse teams perform better than homogeneous ones.

In spite of liking the article pretty well, I take issue with two points.

In the beginning of the article Ries lays down some ground rules, and one of them is that “meritocracy is good.” Is it really good? Always? And to what limit? People are born with talent just as they’re born rich or poor, and what makes talent a better or more fair way of sorting people? Or are we just claiming it’s more efficient?

Actually I could go on but this blog post kind of says everything I wanted to say on the matter. As an aside, I’m kind of sick of the way people use the idea of “meritocracy” to overpay people who they justify as having superhuman qualifications (I’m looking at you, CEO’s) or a ridiculous, massively scaleable amount of luck (most super rich entrepreneurs).

Second, I’m going to coin a term here, but I’m sure someone else has already done so. Namely, I consider it horizon bias to think that wherever you are, whatever you do, is the coolest place in the world and that everyone else is just super jealous of you and wishes they had that job. So you don’t look beyond your horizon to see that there are other jobs that may be more attractive to people. The reason this comes up is the following paragraph:

What accounts for the decidedly non-diverse results in places like Silicon Valley? We have two competing theories. One is that deliberate racisms keeps people out. Another is that white men are simply the ones that show up, because of some combination of aptitude and effort (which it is depends on who you ask), and that admissions to, say Y Combinator, simply reflect the lack of diversity of the applicant pool, nothing more.

I’d like to offer a third option, namely that only white guys show up because that’s who thinks working in Silicon Valley is an attractive idea. I know it’s kind of like the second option above, but it’s not exactly. The qualification “because of some combination of aptitude and effort” is the difference.

Let’s say I’m considering moving to Silicon Valley to work. But all of my images of that place come from movies and my experiences with my actual friends in the dotcom bubble era who slept under their desks at night. Plus I know that the housing market out there is crazy and that the commute sucks. Finally, I’d picture myself working with lots of single, ambitious, and arrogant young men who believe in meritocracy (code for: use vaguely libertarian philosophical arguments to act ruthlessly). I can imagine that these facts keep plenty of non-white non-men away.

Next, going on to the point about horizon bias. People who already work in Silicon Valley already selected themselves as people who think it’s a great deal. And then they sit around wondering why it’s not a more diverse place, in spite of having everything awesomely meritocratic.

Going back to the article, Ries mentions this idea that diverse teams outperform homogeneous ones. I’d like to look at that in light of horizon bias and ask whether that’s the wrong way to look at it. In other words maybe it’s more a function of what the common goal is, which leads to a diverse team if the common goal is broadly attractive, than how the exact team was created. If goals are super attractive, attractive enough to draw diverse people, then maybe those goals deserve success more.

For example, one of the strengths of Occupy Wall Street has been the diversity of its membership. People of all ages, all backgrounds, and all races have been coming together to speak for the 99%. It’s of course fitting, since 99% does represent lots of people, but I’d like to point out that it is diverse because the cause resonates with so many people, which makes it successful.

Another example. I worked at the math department at M.I.T., which is famously not diverse. And I saw the “Truth Values” play recently which made me think about that experience some more. There’s lots of horizon bias in math, because there’s this assumption that everyone who was ever a math major should want to someday become a math professor (at M.I.T. no less). So it’s easy enough to wring your hands when you see that, although 45% of the undergrad math majors are women, and 40% of the grad students in math are women (I’m making these numbers up by the way), only 1% of the tenured faculty at the top places are women (again totally made up).

And of course there’s real discrimination involved (trust me), but there’s also the possibility that a bunch of women just never wanted to be a professor, they just wanted to get a Ph.D. for whatever reason. But the horizon bias at the top places assumes that everyone would want to become a professor.

On the one hand I’m just making things worse, because I’m pointing out that in addition to the real discrimination that takes place for those women who actually do want to become professors, there’s also this natural but invisible self-selection thing going on where women leave the professorship train at some point. Seems like I’ve made one problem into two.

On the other hand, we can address this horizon bias, if it exists. But instead of addressing it by blotting out the names of candidates on applications (a good idea by the way, and one I think I’ll start using), we would need to address it by looking at the actual company or department or culture and see why it’s less than attractive to people who aren’t already there. It’s a bigger and harder kind of change.

ISDA has a blog!

ISDA, or International Swaps and Derivatives Organization, is an organization which sets the market standards in a bunch of ways for credit default swap (CDS) and other over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, in particular they legally define CDS and other swaps and have standard forms for other people to use to enter into such contracts. They also have a committee which decides when a CDS has been triggered, which is a big deal with all the Euro debt restructuring that’s happened and will probably continue to happen.

Anyhoo, what I wanted to mention today is their blog. Actually they have two, one for internal blogging about what they’re up to, and the other for responding to media comments about them.

What’s crazy about these blogs is that they’re well written and… funny. Yeah. You wouldn’t expect that from a legal organization which oversees OTC derivatives, but there you have it. Or else, maybe that just means I’m a complete and utter finance nerd.

And they’re also informative. This post talks about their decision to sue the CFTC for some position limits rule they don’t like. One of their arguments is that the CFTC ignored public comments and cost-benefit analysis which would have loosened the rule or argued against them, and they’re hoping that by suing they can at least force the CFTC to explain how they took into account the public comments.

This argument matters to me because I am involved with the Occupy the SEC folk (OMG those guys are relentless) in preparing public comments for the Volcker Rule, and until now I didn’t know what it meant that there will be public comments and someone has to read them. I mean, I still don’t, really, but it is certainly exciting to see if the CFTC’s hand will be forced in this matter.

Their media blog is informative too. This post talks about how misleading some of the media reports were about why MF Global tanked- it was through repos, not OTC derivatives. True! And by the way, also relevant to the Volcker Rule people, since repos are not considered risky trading in the Volcker Rule. Big huge hole! Doesn’t anybody remember the stuff that Lehman was doing near then end with repos? At the very least they are tools of deception, and need to be taken into account.

Obviously everything they say about CDS and the OTC market is pro-them, but that’s okay. They’re at least saying stuff. I’m impressed!

Crowdsourcing projects

There are lots of new crowdsourcing projects popping up everywhere nowadays, and I wanted to talk about a couple of them.

First I want to talk about a voting system called Votavox. The idea here is to have a massive database which stores the responses of various questions in order to act as a lobbyist for the people. The questions, or rather statements, can be generated by the users, but are encouraged to be relatively non-partisan (or at least stated in a way that isn’t difficult to disagree with), actionable, and tagged with a person who could actually make the action.

For example, if the #Occupy Wall Street website wanted to start using Votavox, they could create a voting item in the direction of, “Mayor Bloomberg should take down the barricades around Zucotti Park and allow free access.” Then everyone who comes to the nycga.net website could vote for this, and the results could be sent to Mayor Bloomberg.

It could be seen as an online petition. It is more convincing when people go to the trouble of registering, so Bloomberg would get to see how many people from different walks of life think this or that. It would also be even more robust if the voting item got placement on the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times as well. That’s the idea, though, to get people’s votes on statements and to send the result directly to a decision maker.

I met with the guy who started it a couple of days ago and I think it’s a cool idea. However, there are some important issues to suss out.

Namely, what’s the business model behind Votavox? One simple answer would be that the data is sold for people to mine. Unfortunately there are lots of unattractive things about this, verging on privacy issues and also the nuisance of having advertisers know all about your inner thoughts. I doubt that #OWS folk would be all that happy about their data being sold to mega advertisers.

On the other hand, servers and databases aren’t free, and maintaining and upgrading the Votavox software isn’t free either. Any ideas for this worthy project would be appreciated.

Next I wanted to talk about an applied mathematician named Lee Worden. Some of his past work has purportedly ‘challenged conventional wisdom on the possibilities of cooperation in situations where only competitive interactions have been assumed’, which is intriguing (maybe someone has a reference for that?). Right now he is interested in studying the mathematics of direct democracy, which is a cool and natural urge. In his words:

A few years ago I started telling friends that I would like to be an applied mathematician for the public, somehow. Unlike pure mathematicians, who work at a remove from everyday concerns and are something like composers, answering to nobody but the Muse, applied mathematicians live more of a have-gun-will-travel life, working for clients, solving the clients’ problems, and developing new theory along the way. The clients are often corporations and the military. Does this affect what we study, what we learn, and what we don’t learn? Of course it does! I decided I should work for the public, and address the public’s problems – but how?

I didn’t realize, when I started this experiment in crowd-funded research, that that’s just what it is: I actually get to work for regular people, on problems that relate to our collective future!

And here’s a video explanation of his #OWS work and a plea for funding. Some of his questions are really good and touch on stuff I’ve already experienced inside the #OWS working group Alternative Banking group, like whether, when we split into smaller groups, we should group people by similarity of opinion or whether we should make sure a range of opinions are represented. On the one hand, if you do group by similarity, the conversations go faster and seem more efficient, but on the other the chances of the end results being adopted by the larger group go way down.

Hank Paulson

A few days ago it came out that former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson is a complete asshole. Some people knew this already, but Felix Salmon kind of nailed it permanently to the wall with this Reuters column where he describes how Paulson told his buddies all about what was going on in the credit crisis a few weeks or days before the public was informed. Just in case descriptions of his behavior aren’t clear enough, Salmon ends his column with this delicious swipe:

Paulson, says Teitelbaum, “is now a distinguished senior fellow at the University of Chicago, where he’s starting the Paulson Institute, a think tank focused on U.S.-Chinese relations”. I’d take issue with the “distinguished” bit. Unless it means “distinguished by an astonishing black hole where his ethics ought to be”.

Here’s another thing that people may want to know about Paulson, and which some people know already but should be more loudly broadcast: he dodged tens of millions of dollars in taxes by becoming the Treasure Secretary. This article from the Daily Reckoning explains the conditions:

Under the guise of not wanting to “discourage able citizens from entering public service,” Section 1043 is an alteration of the government’s conflict of interest rules. Before 1043, executive appointees (mostly high-up cabinet members and judges) had to sell positions in certain companies to combat conflict of interest – like say, a former Goldman Sachs CEO-turned Treasury Secretary with millions of GS shares. After Sec. 1043, the appointee gets a one-time rollover. Upon their appointment, he or she can transfer their shares to a blind trust, a broad market fund or into treasury bonds. They’ll have to pay taxes on the position one day, but not immediately after the sale… like the rest of us.

I’m a big believer in incentives. And from where I sit, when you piece together Hank Paulson’s incentives, you get his actions. In some sense we shouldn’t even complain that he’s such an asshole, because we invented this system to let people like him act in these asshole ways.

[It brings up another related topic, namely that the level of corruption and misaligned incentives actually drives ethical people out of finance altogether. I want to devote more time to think about this, but as partial evidence, consider how few “leaders” from the financial world have stepped up and supported Occupy Wall Street, or for that matter any real challenge to business as usual. At the same time there are plenty of people in finance who are part of the movement, but they tend to be the foot soldiers, or young, or both. Maybe I’m wrong- maybe there are plenty of senior people who just are remaining anonymous, doing their thing to undermine the status quo, and I just haven’t met them. According to this article which I linked to already for a different reason, and which corroborates my experience, there are lots of people who see the rot but not too many doing anything about it.]

Here’s what we do. We ask people who want to be public servants to sacrifice something (besides their ethics) to actually serve the public. I’m convinced that there really are people who would do this, especially if the system were set up more decently. We don’t need to offer huge cash incentives to attract people like Paulson to be Treasury Secretary.

update: I’m not the only person who thinks like this.

Various #OWS links

Here’s an internal Fed blog describing an internal Fed report which proposes that we tie banker bonuses to the CDS spread of the bank. The crux of the idea:

Under our scheme, a high or increasing CDS spread would translate into a lower cash bonus, and vice versa. For banks that do not have a liquid CDS market, the bonus could be tied to the institution’s borrowing cost as proxied by the debt spread. However, the CDS spread has the benefit of being market based, and can be chosen optimally. It is the closest analogue a bank has to a stock price—it is the market price of credit risk. If CEO deferred compensation were tied directly to the bank’s own CDS spread, bank executives would have a direct financial exposure to the bank’s underlying risk and would have an incentive to reduce risk that does not enhance the value of the enterprise.

It’s an interesting idea and I’ll think about it more. I have two concerns off the bat though. First, the blog (I didn’t read the paper) acts like CDS can be honestly taken as a proxy for likeliness to default. However in the real world everything is juiceable. So this scheme will give people more incentives to push for, among other things, fraudulent accounting to avoid looking risky. My second concern is an add-on to the first: the insiders, who benefit directly from low CDS spread, will have very direct reasons to perpetuate such accounting fraud. Somehow I’d love to see (if possible) a scheme put forth where insiders have incentives to ferret out and expose fraud.

———

A beautiful post about the metamovement of which OWS is a part, by Umair Haque. A piece:

In a sense, that sentiment is the common thread behind each and every movement in the Metamovement — a sense of grievous injustice, not merely at the rich getting richer, but at the loss of human agency and sovereignty over one’s own fate that is the deeper human price of it.

He links to We Are the 99 Percent. Check it out if you haven’t already seen it.

———

Interfluidity blogs about how yes, the bankers really were bailed out. Big time. Great points, here is my favorite part:

Cash is not king in financial markets. Risk is. The government bailed out major banks by assuming the downside risk of major banks when those risks were very large, for minimal compensation. In particular, the government 1) offered regulatory forbearance and tolerated generous valuations; 2) lent to financial institutions at or near risk-free interest rates against sketchy collateral (directly or via guarantee); 3) purchased preferred shares at modest dividend rates under TARP; 4) publicly certified the banks with stress tests and stated “no new Lehmans”. By these actions, the state assumed substantially all of the downside risk of the banking system. The market value of this risk-assumption by the government was more than the entire value of the major banks to their “private shareholders”. On commercial terms, the government paid for and ought to have owned several large banks lock, stock, and barrel. Instead, officials carefully engineered deals to avoid ownership and control.

———

Next, read this Newsweek article if you’re still wondering what Mayor Bloomberg’s personal incentives are for letting OWS complain about crony capitalism and the power of lobbyists. The scariest part:

Let’s say a lobbyist for a coal company wants to squash any legislation that affects his employer’s mining operations. He logs onto BGov.com (the cost is $5,700 per year) and is automatically alerted to breaking news of a just-introduced energy bill. The data drill-down begins. BGov shows the lobbyist how similar legislation has fared, what subcommittee the new bill will face and when, who the key congressmen are, and how they have voted in the past. The lobbyist calls up information on the swing vote’s upcoming election contest: it’s competitive, and the congressman is behind in fundraising. Lists of major donors—who might be induced to contribute or, better yet, place a call to the officeholder himself—are a click away. These political pressure points and a thousand more are how lobbyists make their mark, and Bloomberg thinks BGov can deliver them faster than the competition.

———

Finally, a very nice blog about the Alternative Banking group and David Graeber by Joe Sucher. Here’s an excerpt:

I know the usual naysayers will nay say until they are blue in the face about changing the so-called system. “It will never happen, never will, so let’s wait for things to settle down and go back to business as usual.” These folks, I’d venture to say, may be exhibiting a fundamental crisis of imagination.

I remember an elderly immigrant anarchist reminded me (when I was naysaying) that if you were to tell a 14th century European serf, that some time in the next few hundred years, they’d actually have the ability to cast a vote that mattered, no doubt you’d be met with a blank stare. The thought just wouldn’t compute.

——–

updated: Jesse Eisenger of Propublica wrote this interesting article in DealBook, where he talks about the insiders on the Street who are frustrated by the rampant corruption. I agree with a lot he says but he clearly needs to join us at an Alternative Banking group meeting:

It’s progress that these sentiments now come regularly from people who work in finance. This is an unheralded triumph of the Occupy Wall Street movement. It’s also an opportunity to reach out to make common cause with native informants.

It’s also a failure. One notable absence in this crisis and its aftermath was a great statesman from the financial industry who would publicly embrace reform that mattered. Instead, mere months after the trillions had flowed from taxpayers and the Federal Reserve, they were back defending their prerogatives and fighting any regulations or changes to their business.

Perhaps a major reason so few in this secret confederacy speak out is that they are as flummoxed about practical solutions as the rest of us. They don’t know where to begin.

Um, there are plenty of very good places to begin. It’s a question of politics, not of solutions. Start with the very basics: enforce the rules that already exist. Give the SEC some balls. We’ll go from there. Sheesh!

Two pieces of good news

I love this New York Times article, first because it shows how much the Occupy Wall Street movement has resonated with young people, and second because my friend Chris Wiggins is featured in it making witty remarks. It’s about the investment bank recruiting machine on college campuses (Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Dartmouth, etc.) being met with resistance from protesters. My favorite lines:

Ms. Brodsky added that she had recently begun openly questioning the career choices of her finance-minded friends, because “these are people who could be doing better things with their energy.”

Kate Orazem, a senior in the student group, added that Yale students often go into finance expecting to leave after several years, but end up staying for their entire careers.

“People are naïve about how addictive the money is going to be,” she said.

Amen to that, and wise for you to know that! There are still plenty of my grown-up friends in finance who won’t admit that it’s a plain old addiction to money keeping them in a crappy job where they are unhappy, and where they end up buying themselves expensive trips and toys to try to combat their unhappiness.

And here’s my friend Chris:

“Zero percent of people show up at the Ivy League saying they want to be an I-banker, but 25 and 30 percent leave thinking that it’s their calling,” he said. “The banks have really perfected, over the last three decades, these large recruitment machines.”

Another piece of really excellent new: Judge Rakoff has come through big time, and rejected the settlement between the SEC and Citigroup. Woohoo!! From this Bloomberg article:

In its complaint against Citigroup, the SEC said the bank misled investors in a $1 billion fund that included assets the bank had projected would lose money. At the same time it was selling the fund to investors, Citigroup took a short position in many of the underlying assets, according to the agency.

“If the allegations of the complaint are true, this is a very good deal for Citigroup,” Rakoff wrote in today’s opinion. “Even if they are untrue, it is a mild and modest cost of doing business.”

A revised settlement would probably have to include “an agreement as to what the actual facts were,” said Darrin Robbins, who represents investors in securities fraud suits. Robbins’s firm, San Diego-based Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP, was lead counsel in more settled securities class actions than any other firm in the past two years, according to Cornerstone Research, which tracks securities suits.

Investors could use any admissions by Citigroup against the bank in private litigation, he said.

This raises a few questions in my mind. First, do we really have to depend on a randomly chosen judge having balls to see any kind of justice around this kind of thing? Or am I allowed to be hopeful that Judge Rakoff has now set a precedent for other judges to follow, and will they?

Second, something that came up on Sunday’s Alt Banking group meeting. Namely, how many more cases are there that the SEC hasn’t even bothered with, even just with Citigroup? I’ve heard the SEC was only scratching the surface on this, since that’s their method.

Even if they only end up getting $285m, plus the admission that they did wrong by their clients, could the SEC go back and prosecute them for 30 other deals for 30x$285m = $8.55b? Would that give us enough leverage to break up Citigroup and start working on our “Too Big to Fail” problems? And how about the other banks? What would this litigation look like if the SEC were really trying to kick some ass?

Regulation arbitrage, the Volcker Rule, and TBTF (#OWS)

Regulation arbitrage

We had a interesting, lively #OWS Alternative Banking group meeting yesterday, where we split into three groups: the Volcker Rule commenting group, the shadow banking system, and Too Big to Fail (TBTF). I was impressed by the number of people who could come even on Thanksgiving weekend.

These topics have lots of overlap, a fact which came through at the end when we got back together and disseminated our thoughts. Specifically, the question of “regulation arbitrage” came up repeatedly. This is the idea that, no matter what laws you pass on how the banks can behave, they will get around the spirit of the law with some clever sleight of hand. In other words, it’s really hard to avoid a bad outcome if you have to list all of the things that someone isn’t allowed to do- they can avoid a rule governing having repos of no longer than 7 days by inventing a new instrument, which they may call a “nepo,” which has an 8 day lifespan.

It’s frustrating, since real regulation is clearly needed right now, and it makes you want to depend more on standards than specific rules. However, the problem with standards is that they can be avoided as well, by the sheer fact that they are always open to interpretation. Moreover, both of these approaches run the risk of being essentially too complicated for regulators to understand, but the standards one is particularly open to that.

If anyone has a third option that I haven’t thought of, please tell. Oh wait, someone suggested one to me: jailtime. This is actually a good point, and also possibly the best idea I’ve heard of to give some balls back to the SEC and other regulators: give them handcuffs and the authority to use them.

It occurs to me that the software testing community may have an answer, or at least an approach. It may make sense to set up a series of exhaustive tests which evaluates the resulting portfolio of the bank for certain characteristics which would indicate whether the bank has been following the standards appropriately.

To some extent this is being done, using various risk measures, for example looking at the volatility of the PnL to determine if someone is really market making or not. But I’m not sure the super nerds have thought about this onetoo much. I’d be interested to talk to anyone who knows.

Volcker Rule

There are two articles I wanted to bring up today. First, we have this Huffington Post article about the Volcker Rule commenting group Occupy the SEC, which has been meeting with us on Sundays and whom I’ve blogged about here and here. Some key quotes:

A handful of protesters at Occupy Wall Street are doing what the authors of a complex piece of financial legislation may have hoped no one would do. They are reading it.

…

The Occupy Wall Street movement, now in its third month, has drawn fire from people who say its members are too vague in their criticism of the financial system. Occupy the SEC, which consists of between four and eight New York protesters, would seem immune to such charges. Its members are compiling a list of highly specific points, and their ultimate goal is to submit a letter to regulators detailing their concerns before the Jan. 13 deadline.

Anyone can send in comments on the draft of the Volcker rule — and regulators will review those submissions before producing a final version of the measure — but, as in most cases where draft rules are made available for public scrutiny, not everyone has the time or inclination to parse hundreds of pages of regulatory jargon. Goldstein noted that most of the comments on financial rules end up coming from the banks themselves, arguing for greater leniency.

…

Paul Volcker himself has expressed displeasure with the current proposal, which is 30 times as long as the version originally included in Dodd-Frank.

Go team!

TBTF

Next, during the meeting yesterday where we were discussing Too Big to Fail (TBTF) and what can be done about it, Bloomberg published this article, which ranks among the best I’ve seen from them (up there with the Koch brothers article from a few weeks ago which I blogged about here).

The article describes the extent and amount of the secret Fed loans given to each bank for “liquidity” purposes during the credit crisis. Here’s a good quote:

While Fed officials say that almost all of the loans were repaid and there have been no losses, details suggest taxpayers paid a price beyond dollars as the secret funding helped preserve a broken status quo and enabled the biggest banks to grow even bigger.

Thank you! Why doesn’t everyone see that it makes no sense to say “we were paid back” when the underlying problem is still there (in fact worse) and we have given up our standards? On a related note:

The Fed didn’t tell anyone which banks were in trouble so deep they required a combined $1.2 trillion on Dec. 5, 2008, their single neediest day. Bankers didn’t mention that they took tens of billions of dollars in emergency loans at the same time they were assuring investors their firms were healthy. And no one calculated until now that banks reaped an estimated $13 billion of income by taking advantage of the Fed’s below-market rates, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its January issue.

Even if the $13 billion is arguable (I don’t have an opinion about that), I know it’s an underestimate because the alternative to this secret unlimited liquidity was bankruptcy, not less revenue.

The article brings up lots of interesting issues, beyond the asstons of cash money that were thrown at the banks during that time. Among them:

- To what extent would Congress have blocked TARP if they had know the size of the Fed program? Remember they actually voted TARP down before coming back and changing their mind after the stock market dropped by 10%. My favorite quote for this question comes from Sherrod Brown, a Democratic Senator from Ohio: “This is an issue that can unite the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street. There are lawmakers in both parties who would change their votes now.” I agree- this is a non-partisan issue.

- How much freaking power does the Fed have to do stuff behind closed doors? To what extent was this motivated by their feelings of shame that they’d let the housing bubble inflate for so long? Related quote from the article: “I believe that the Fed should have independence in conducting highly technical monetary policy, but when they are putting taxpayer resources at risk, we need transparency and accountability,” says Alabama Senator Richard Shelby, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee.

- Geithner seems to be against the idea of ending TBTF: “Geithner argued that the issue of limiting bank size was too complex for Congress and that people who know the markets should handle these decisions.” The article then goes on to say that Geithner suggested we just let the international economic community decide the new rules, i.e. Basel III. But as we know, that treaty has zero chance of being adopted by the U.S. at this point, so the end result is that Geithner put off the discussion by arguing that it would be dealt with internationally, but then it hasn’t been, at all. Moreover, the article mentions that the Dodd-Frank bill has a mechanism for closing down too-big-to-fail banks, decided by a committee of which Geithner is chair. I’m not holding my breath.

The most embarrassing part of the article is next, and deals again with the TBTF issue.

Lobbyists argued the virtues of bigger banks. They’re more stable, better able to serve large companies and more competitive internationally, and breaking them up would cost jobs and cause “long-term damage to the U.S. economy,” according to a Nov. 13, 2009, letter to members of Congress from the FSF. The group’s website cites Nobel Prize-winning economist Oliver E. Williamson, a professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, for demonstrating the greater efficiency of large companies.

In an interview, Williamson says that the organization took his research out of context and that efficiency is only one factor in deciding whether to preserve too-big-to-fail banks. “The banks that were too big got even bigger, and the problems that we had to begin with are magnified in the process,” Williamson says. “The big banks have incentives to take risks they wouldn’t take if they didn’t have government support. It’s a serious burden on the rest of the economy.”

Nice! Hey FSF, you may want to find a new quote! Oh wait, that link no longer works, interestingly…

I’m planning a follow-up blog post to discuss what our group decided to do with respect to TBTF. Hint: it has something to do with a Republican presidential candidate.

Sing with me! (#OWS)

If there’s one thing we need right now in the Occupy movement, it’s a bit of inspiration, hope, and silliness. I was touched to hear that 300 people ate Thanksgiving dinner at Zuccotti Park yesterday (although the standoff with police over the drumming didn’t sound awesome) but let’s face it, it hurts that the park was cleared of tents.

It’s really easy to slide into a funk right about now: there’s bad press, the Eurozone is looking doomed, and politicians are frozen in conflict. I say don’t let it happen. Don’t take everything too seriously, because these things take a long time to work, and so much progress has already been made. Let’s look at winter as a time to hunker down and work on our projects so that in the Spring we can get together and be amazed by how far we’ve come.

I really like the idea of Occupying Black Friday- today will be the first time I actually participate at all, except for the time we drove all the way to Ithaca for Thanksgiving before realizing we forgot our suitcase and we ended up buying clothes and toothbrushes on Friday. That doesn’t really count though.

So I’m planning to be a consumer zombie today at the mall near Columbus Circle. That just means I’ll walk around like a zombie and wearing a sign that says “consumer”. I’m bringing my 3-year old; I’m thinking of putting a sign on his back saying “consumer in training” or something.

But here’s what I’m really into. Flash mob singing. Yeah, seriously, the inner musical performer in me is dying to get a group of people and come up with a seriously awesome song and associated line dance. In a mall or maybe a public space like Times Square. Something that makes people baffled and happy, that makes them think about how love works.

To see how I was thus inspired, see this wonderful Occupy Oakland protest. For those of you who don’t know me, I am the barefoot girl in the bright pink cocktail dress with a matching boa and backpack. I mean, not really since I haven’t gone to Oakland recently, but that’s who I am, if you can dig it.

So who’s in? I’m taking suggestions for song, dance, and venue. If you’re not local you can still participate by coming up with ideas! If you are local, grab your boa.

‘Move Your Money’ app (#OWS)

One of the most aggravating things about the credit crisis, and the (lack of) response to the credit crisis, is that the banks were found to be gambling with the money of normal people. They took outrageous risks, relying on the F.D.I.C. insurance of deposits. It is clearly not a good system and shouldn’t be allowed.

In fact, the Volcker Rule, part of the Dodd-Frank bill which is supposed to set in place new regulations and rules for the financial industry, is supposed to address this very issue, or risky trading on deposits. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the Volcker Rule itself goes far enough – or its implementation, which is another question altogether. I’ve posted about this recently, and I have serious concerns about whether the gambling will stop. I’m not holding my breath.

Instead of waiting around for the regulators to wade through the ridiculously complicated mess which is the financial system, there’s another approach that’s gaining traction, namely draining the resources of the big banks themselves by moving our money from big banks to credit unions.

I’ve got a few posts about credit unions from my guest poster FogOfWar. The basic selling points are as follows: credit unions are non-profit, they are owned by the depositors (and each person has an equal vote- it doesn’t depend on the size of your deposits), and their missions are to serve the communities in which they operate.

There are two pieces of bad news about credit unions. The first is that, because they don’t spend money on advertising and branches (which is a good thing- it means they aren’t slapping on fees to do so), they are sometimes less convenient in the sense of having a nearby ATM or doing online banking. However, this is somewhat alleviated by the fact that there are networks of credit union ATM’s (if you know where to look).

The second piece of bad news is that you can’t just walk into a credit union and sign up. You need to be eligible for that credit union, which is technically defined as being in its field of membership.

There are various ways to be eligible. The most common ones are:

- where you live (for example, the Lower East Side People’s Federal Credit Union allows people from the Lower East Side and Harlem into the field of membership)

- where you work

- where you worship or volunteer

- if you are a member of a union or various kinds of affiliated groups (like for example if you’re Polish)

This “field of membership” issue can be really confusing. The rules vary enormously by credit union, and since there are almost 100 credit unions in New York City alone, that’s a huge obstacle for someone to move their money. There’s no place where the rules are laid out efficiently right now (there are some websites where you can search for credit unions by your zipcode but they seem to just list nearby credit union regardless of whether you qualify for them; this doesn’t really solve the problem).

To address this, a few of us in the #OWS Alternative Banking group are getting together a team to form an app which will allow people to enter their information (address, workplace, etc.) and some filtering criteria (want an ATM within 5 blocks of home, for example) and get back:

- a list of credit unions for which the user is eligible and which fit the filtering criteria

- for each credit union, a map of its location as well as the associated ATM’s

- link to the website of the credit union

- information about the credit union: its history, its charter and mission, the products it offers, the fee structure, and its investing philosophy

It’s a really exciting project and we’ve got wonderful people working on it. Specifically, Elizabeth Friedrich, who has amazing knowledge about credit unions inside New York City (our plan is to start withing NYC but then scale up once we’ve got a good interface to add new credit unions), Robyn Caplan, who is a database expert and has worked on similar kinds of matching problems before, and Dahlia Bock, a developer from ThoughtWorks, a development consulting company which regularly sponsors social justice projects.

The end goal is to have an app, which is usable on any phone or any browser (this is an idea modeled after thebostonglobe.com’s new look- it automatically adjusts the view depending on the size of your browser’s window) and which someone can use while they watch the Daily Show with Jon Stewart. In fact I’m hoping that once the app is ready to go, we go on the Daily Show and get Jon Stewart to sign up for a credit union on the show just to show people how easy it is.

We’re looking to recruit more developers to this project, which will probably be built in Ruby on Rails. It’s not an easy task: for example, the eligibility by location logic, for which we will probably use google maps, isn’t as easy as zipcodes. We will need to implement some more complicated logic, perhaps with an interface which allows people to choose specific streets and addresses. We are planning to keep this open source.

If you’re a Rails developer interested in helping, please send me your information by commenting below (I get to review comments before letting them be viewed publicly, so if you want to help, tell me and won’t ever make it a publicly viewable comment, I’ll just write back to your directly). And please tell your socially conscious nerd friends!

What’s the Volcker Rule?

I wrote recently about the #OWS Alternative Banking working group preparing public comments on the Volcker Rule. I wanted to give a little bit more context. This is especially important right now because the watering-down period by financial lobbyists is getting intense.

The original Volcker Rule essentially states that banks shouldn’t do proprietary trading at all and they should also not invest in hedge funds or provate equity funds or in any way be liable for losses on such funds.

The idea is that the government and thus the taxpayer is backing (through the FDIC) the money inside banks and those banks shouldn’t use that insurance while at the same time risking the deposits themselves just to make a quick buck. To actually see this law, see Section 619 in the Dodd-Frank act. The law itself is only 11 pages, and some of that is around timing of implementation, so it’s a quick read.

Again, this 11-page document states what the Volcker Rule is supposed to implement. It summarizes the high-level thinking behind the rule. More importantly, the regulators’ mandate is to write a detailed rule that complies with what’s written in the law. When they ask for comments on the rule, they’re asking how well the rule implements the law.

This sounds pretty clean cut, but of course there are grey areas: for example, the law states that if banks fail to comply with the no-prop trading or hedge fund investing rules, then they’ll get punished by having higher capital requirements as well as fines. But it fails to say how stringent those punishments will be. So one way to technically implement the law is to make the punishment trivial.

The law also claims that the banks should be allowed to trade outside their clients’ direct interests in the name of hedging risks. The granularity of that allowed “hedging” is critical, since if they are hedging at the trade level, that’s very different from hedging at the macro level. The best example I’ve heard of this is that the bank may decide there’s “inflation risk” in their portfolio and start investing in long-term inflation hedges; then this really becomes more of a bet than a hedge but it depends on how you look at it and more importantly how one defines the word hedge.

To a large extent I feel like this could be resolved if we force a short-term horizon on the hedging basis. In other words, it’s a hedge if you can argue that you bought a bunch of 1-month puts so you need to hedge your risk on that one month period. However, a 5-year inflation outlook is clearly more of an opinion. On the other hand, forcing banks, as a group, to think in short horizons has its own dangers.

The law also states that banks are allowed to invest in certain U.S.-backed agencies:

PERMITTED ACTIVITIES… The purchase, sale, acquisition, or disposition of obligations of the United States or any agency thereof, obligations, participations, or other instruments of or issued by the Government National Mortgage Association, the Federal National Mortgage Association, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, a Federal Home Loan Bank, the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation, or a Farm Credit System institution chartered under and subject to the provisions of the Farm Credit Act of 1971 (12 U.S.C. 2001 et seq.), and obligations of any State or of any political subdivision thereof.

There are those who claim that we need to expand the above rule for the sake of national security and to prevent a deep, world-wide depression. Specifically, in this article in the Financial Times, the lobbyists are working hard to allow prop trading in European bonds, a huge market which is currently stipulated to be out of bounds:

They point out that Dodd-Frank exempts US sovereign bonds from the general prop trading ban for fear of disruptions. “What happens if you remove the US banks from Europe and they dump the stuff? Prices could collapse,” said Doug Landy, a regulatory lawyer at Allen & Overy.

There are lots of other permitted activities that don’t necessarily make sense to the historian of how other firms have gotten themselves into trouble: interest rate swaps (which are surely necessary tools for hedging basic bank hedging but it doesn’t seem to be restricted to hedging), spot commodities, foreign currency, and all kinds of loans (including repos). There are plenty of ways for banks to put deposits at risk within these instrument classes.

My conclusion is that, when the Alternative Banking group sends feedback to the regulators, we should separate comments on the implementation of the rule (e.g., what risk measures should be used and in how much detail they should be specified) from comments on the underlying law (e.g., whether this is actually preventing conflicts of interest).

The regulators are supposed to fix problems with the rule, but they can’t fix problems with the law (it takes an act of Congress to fix those). To the extent that we have problems with what’s in the law itself, it is worth a separate discussion about what the best way is to get those addressed.

What does “too big to fail” mean?

The Alternative Banking meeting yesterday was really good, and interesting. During the discussion someone raised the point that when we describe a bank as “too big to fail,” we almost always measure that in terms of their assets under management, or the percent of deposits they have, or their net or gross exposures. In other words, we measure the size of the individual institution.

However, what’s just as important in terms of being “too big” is the extent to which a given bank is too interconnected, meaning they are in deals with so many other counterparties that if they go under, they would set off a cascade of contractual defaults which would cause chaos in the entire system. In fact Lehman was like this, too interconnected to fail. It’s funny but I’m pretty sure Lehman wasn’t too big to fail under many of the current definitions.

Although this question of counterparty risk is brought up consistently, it’s never adequately addressed in terms of risk; we are still more or less asking people to measure the volatility of their PnL, and we typically don’t force them to expose their counterparty exposure in stress tests and whatnot.

What if we addressed this directly? How could we regulate the interconnectedness of a given institution? What would be the metric in the first place and what limits could we set? How could we set up a regulator to convincingly check that institutions are sticking to their interconnectedness quotas?

I’ll keep thinking about this, they are not easy questions. But I think they are important ones, because they get to the heart of the current problems more than most.

A further question brought up yesterday was, how do we know when the entire financial system is too big? I guess we don’t need any fancy metrics to say that for now we just know.

Alternative Banking meeting today

We’re meeting from 3-5pm today at 1401 International Affairs Building on Columbia Campus. That’s at Amsterdam and 118th, on the 14th floor. The meeting is open to everyone.

It’s going to be an interesting meeting today. Lots has happened this week with the movement, obviously, and it’s super important to keep the conversation going and productive. We got some press coverage in the Financial Times and perhaps because of that I’ve added quite a few new names to the email list. I’m very much looking forward to meeting the new members of our group.

Bloomberg’s decision with removing the tents from the park and the 2-month anniversary protests got lots of attention, not all of it positive. I participated in the protest the other day with my son, and since then I’ve had a few thoughts about it.

This movement is a big deal and can potentially be a bigger deal. It’s certainly one of the things I care about deeply. I understand people’s frustration and defiance, because even just thinking outside the system when it’s this huge and embedded is an act of defiance. But what I don’t want to see is the movement losing its head and giving in to anger and rage. Especially because it inevitably becomes something extremely narrow- us against the police, or us against Bloomberg.

The truth is the police, at least the ones on the ground in riot gear, have very little to do with setting up this system. Bloomberg has more to do with it, but he’s still just another scavenger picking out the juiciest meat of the system. What we need to do is understand the bigger picture and try to improve things in a meaningful and positive way.

That’s not to say that I want to work within the system to change it. I’m not that naive to think that people give up their honeypots so easily: this will be a war against corruption and vested interests. But I’d rather spend my time rooting out real corruption (like Jack Abramoff has done in this amazing Bloomberg article) and proposing realistic alternatives than being vaguely angry at the wrong things.

The democratic system that the OWS movement has created is based on the idea of mutual respect and trust. We need to enlarge that sense of trust to more and more people, including the cops and including the mayors. We want to invite them to join us, or at least to respect us.

It’s my experience that most people want to live in a just world- even if they take advantage of injustices for themselves. The majority of people working in the financial system see it as unfair and unreasonable. One reason they let things slide is that they really don’t believe the system could be changed; they don’t have the imagination or the faith to believe that. So that’s actually what we can and should provide: imagination and faith.

No system is perfect, of course, but there are certainly systems that are less imperfect, and we should be envisioning them and a path towards them which is reasonable and not terrifying. If we could do that we would get support rather than pepperspray. I know I’m sounding idealistic, but that’s actually what we need right now. After all the original protest started with nothing more than silly hand signals and ideals; its international growth has proven that ideals resonate with people.

Occupy the SEC: commenting on the Volcker Rule

One of the subgroups of the Alternative Banking group is an #OWS group called Occupy the SEC. Their goal is to make comments on the Volcker Rule before the public commenting period ends on January 13th, 2012.

At our last meeting we distributed a sheet where people put their email addresses and listed fields of expertise so that the people in Occupy the SEC could ask us specific clarifying questions about what the current version of the Volcker Rule says.

If you think you could have time to help them, please email them at occupythesec@gmail.com and tell them what your fields of expertise are. They are mostly looking for financial expertise and people who speak legalese, but anyone who is a good and careful reader will be super useful too.

My experience at Riskmetrics working with Value-at-Risk (VaR), where I was actually working on methodology questions of VaR usage for credit instruments like CDS, makes me pretty useful to these guys.

This morning I’ve been reading about the proposed risk reporting requirements for the “covered bank entity”. Basically they are required to report daily 99th percentile VaR. But left out are all other details, including:

- whether they should use parametric, historical, or MonteCarlo VaR methods,

- what their lookback period is (if historical)

- what their decay length is (if MonteCarlo)

- what exactly they need to admit as risk factors

- why they would ever use parametric VaR outside of stocks, since parametric VaR sucks outside of stocks.

They are also asked to report the skew and kurtosis of their daily PnL, but I believe are only required to report this for daily numbers on a quarterly basis, which means there’s no chance in hell those will be meaningful numbers.

How about this instead: report all three kinds of VaR, with a year lookback for historical VaR, and with various decay lengths for MonteCarlo VaR. Specify the risk factors and ask for each risk factor’s sensitivity (which is like a partial derivative if we are using parametric VaR) as well as min and max returns (if we are using historical VaR). Report skew and kurtosis using daily numbers with 2 years of data.

Even better if they abandon this altogether and go for something benchmarked as I discussed in this post.

There seems to be no stipulated need to report counter-party exposure or risk, at least in this section (Appendix A). This seems particularly egregious considering the current situation, namely that we are waiting for European sovereign debt defaults to cause broken CDS hedges through collapsing counterparties. We know this would happen, but we somehow don’t want to know more details.

This is only a few pages of the Volcker Rule, though, out of I think something like 550. We need your help for sure!

Protest today

I don’t know where you’re going today after work but there’s going to be a massive protest in front of city hall starting at 5pm.

See outrageous footage of this morning on Wall Street here coming from the Wall St. Journal.

I’m thinking of going with my oldest son, who is very excited about it and desperately wants to join, especially if it means missing school (but I think his enthusiasm would be sustained if he got to go to bed late as well). I actually brought him with me that very first day I went down to check out the protest on day 13, and he’s been bragging about being in the “opening bell march” ever since.

He also thinks kids should be able to vote (and wants to join the Alternative Banking working group). Here’s an article suggesting we should do something even more extreme, namely let people vote from birth. It’s an interesting idea and could encourage families to engage in politics more.

The truth is my son thinks and cares about issues of politics and justice more than most grownups. In fact he once was a huge Obama supporter, and around the election he’d watch Obama’s speeches after finishing his homework. I thought he must just be missing most of it, since it was mostly rhetoric, and after all he was only 8 years old at the time, but then something happened which changed my mind.

We were leaving a restaurant after eating dinner, and he held the door open for me to push the stroller through with his baby brother (I think this was actually the first time we ever went out to eat with the baby). As the door closed I saw little girl, maybe 3, who looked dangerously close to getting her hand caught in the door, and I jumped back to hold the door open. My son told me he felt bad that he almost let the door hurt the little girl, to which I replied, “first of all she wasn’t really that close to the door, and second of all it’s not your responsibility to worry about other people’s kids.” My son replied, “but when Obama says that we rise and fall as a people, he means that’s exactly what our responsibilities are!”

I heard rumors that people in Zuccotti Park, who I think are still being let in single-file through a big gate with cops doing a kind of airport check-in, have been told that they aren’t allowed to “carry signs inside the park.” First of all that’s ridiculous and second of all that’s not going to make the Bloomberg administration look reasonable. Is Bloomberg going for a legacy of squelching a non-violent legal protest? I thought he was all about bringing engineering to New York.

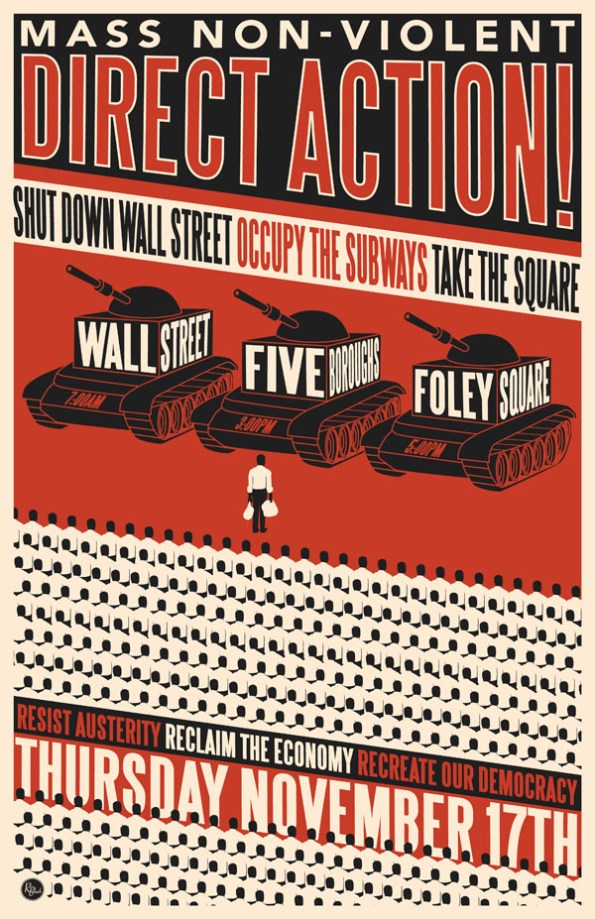

Here’s the poster for today’s protests. I’m a bit confused by the juxtaposition of the word “non-violent” and the presence of tanks, maybe someone could explain that one to me this is a reference to Tiananmen Square I’ve been told:

Zuccotti Park just now: updated

Police are keeping people out of the park.

In addition, the Atrium at 60 Wall is closed all day. They haven’t said when it will reopen.

You can register your opinion on this handy New York Times graphic.

They’re back in! Check it out live.

Postage paid protest

I’m glad I got a new laptop with sound, because now I can listen to and watch this awesome YouTube video with suggestions to keep Wall Street occupied.

The sin of debt

It’s fascinated me for a while how people use language to indicated the relationship between money and morality. David Graeber’s book about debt took this issue on directly, but even before reading it I had noticed the disconnect between individual debt and corporate debt.

It was clear from my experience in finance that debt is something that, at the corporate level, is considered important – you are foolish not to be in debt, because it means you’re not taking advantage of the growth opportunities that the business climate affords you. In fact you should maximize your debt within “reasonable” estimates of its risk. Notable this is called leveraging your equity, a term which if anything sounds like a power move.

That just describes the taking on of debt, which for an individual is something they are likely not going to describe with such bravado, since they’d be forced to use measly terms such as “I got a loan”. What about when you’re in trouble with too much debt?

My favorite term is debt restructuring, used exclusively at the corporate (or governmental) level. It makes defaulting on ones debt a business decision by a struggling airline or what have you, and the underlying tone is sympathy, because don’t we want our airlines (or other american companies) to succeed?

When you compare this language and its implied morality (neutral) to the moralistic preaching of late-night talk radio, it’s quite stark. It’s made clear on such shows that debt is a sin, that the reason the show is a success is that it’s entertainment to hear how messed up the callers’ finances are, and to hear the radio host drill into their most private details in the name of ferreting out that sin.

The Suzy Ormon show is another example of this, and this blog entry is a great description of the emotional and spiritual repentance required in our culture when one is in debt, bizarrely combined with her urging you to go out and consume some more.

For the individual there is no debt restructuring available – at best you can get your debt consolidated, but the people who do that are themselves considered icky. There’s no clean way to deal with out-of-control debt as an individual.

Until now! I found an interesting article the other day which somehow excludes certain people from the moral failing of being in debt – namely, if they have the help of another powerful buzzword – a moral reclamation if you will – namely, “entrepreneur.” Because we all want our entrepreneurs to succeed!

The fact that the program doesn’t apply to most of a typical person’s student debt load is only partly relevant – for me, the fascinating part is the way that, when you stick in the word “entrepreneur,” you suddenly have the vision of someone who shouldn’t be saddled with debt, who is immediately forgiven for their sins. It brings up the question, can we perform this moral cleansing for other groups of people who are currently in debt?

What if we coopted the language of the corporations for the individual? I’d love to hear people talking about large-scale restructuring of their debt. Just the phrase makes me realize its possibilities. One of the main tools of leverage for such talks is the amount of money on the table. If sufficiently many people got together to formally restructure their credit card debts, what would the banks do? What could they do except negotiate?

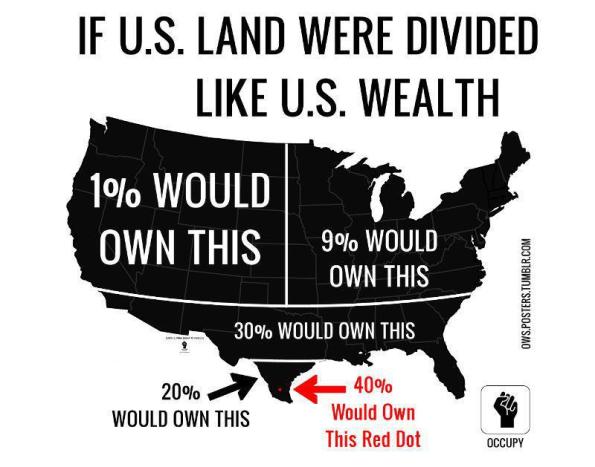

Here’s a graphic I like just in case you haven’t seen it yet: