Archive

Vikram Pandit: let’s talk

Here’s the coverage from Business Insider.

Here’s the letter (also posted on Naked Capitalism):

Dear Mr. Pandit,

Last October, in an interview with Fortune Magazine, you extended an invitation to Occupy Wall Street for a face-to-face meeting. The Alternative Banking Group, an official working group of Occupy Wall Street, hereby accepts.

As CEO of Citigroup, you recently announced “a new Citi.” You said that you are now “working hard to create a culture of responsible finance.” Our mission as the Alternative Banking Group is exactly the same. We look forward to a fruitful dialogue.

Since this conversation is of importance to the general public, we will have a small camera crew with us to document it. The video will be shared on the websiteoccupy.com, an emerging media platform for the Occupy movement.

Please respond to this email at your earliest convenience to schedule a time and place.

Sincerely,

Cathy O’Neil

Facilitator

The Alternative Banking Group

Occupy Wall Street

Please comment with questions we can ask Vikram if he accepts our offer.

I am the most boring person in the world

A few nights ago I went to a CFPB Town Hall Meeting after work. The discussion in the kitchen that morning went something like this:

me: “I’m going to be late tonight, guys, because I’m going to a CFPB Town Hall meeting… I’m really excited about it!”

my husband: “What the hell is CFPB?”

me: “Oh, it stands for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. You know, the thing that Elizabeth Warren started but then didn’t get to be in charge of? I need to go see if this guy Cordray is going to be pushy enough to lead an effective government agency. Today the issues at the meeting are things like checking accounts and debit cards and overdraft policies. I totally need to go, can you guys eat leftovers?”

my husband: “You are the most boring person in the world”

my three sons, simultaneously: “Yeah mom, he’s right. You are the most boring person in the world.”

Whatever. I guess they’re right, but I went anyway. After lots of incredibly congratulatory introductions, including a 5 minutes speech from New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, there were a bunch of questions from the audience.

There were lots of community groups represented, as well as individuals. Two themes emerged through the questions that seem like particularly egregious consumer issues affecting poor people.

First was the issue of pre-paid debit cards and the corresponding fees. This guy stood up at the microphone and described his friend who get a debit card for child support, court-ordered. But this debit card extracts enormous fees every time she takes money out, including things like $5 just to check the balance. The guy was saying, you know my friend needs that money for her children, and it’s not fair that so much of it goes to fees- it’s abusive. I was totally crying. I mean, I’m an easy cry, but still. That wasn’t the only story about such debit cards where there was no choice in the matter but the fees were extortionist.

Second the issue of Walmart issuing its pay to people in debit card form came up time after time as well. So it seems that Walmart is not only a retailer, but also a financial institution of the crappiest kind now. It issues debit cards as payment to people who don’t accept direct deposit or don’t have checking accounts, and again it seems that the money on the cards is somehow deeply tied to a fee structure. I need to look into this more (as does the CFPB) but I’m wondering off the top of my head whether people can just demand to be paid in cash instead. It’s like these people are being paid really badly, with very few benefits, and even when they get paid they’re being nickeled and dimed every step of the way. It’s like it’s not really their money even then.

So in other words, debit cards are the new check cashers, but maybe worse since their fee structure doesn’t seem to be as transparent.

Of course, I took the opportunity to ask a question too, since I am not shy. And I was told not to ask a question but rather to tell a story, but whatever, I decided to phrase is as “making three suggestions.” After introducing myself as coming from the Alternative Banking group, I mentioned the following:

- The CFPB should use its powers to bring together mortgage investors and homeowners to the same table, in order to align their interests and bypass the banks as servicers, since the banks are only endlessly delaying the process in order to extract fees.

- I mentioned that our group is working on a “find a credit union app” but that the CFPB should really be doing that with us, to help underbanked people find alternatives to crappy banking solutions (like debit cards).

- I mentioned that we had submitted a public comment letter demanding that the credit score models be open sourced, since there was no legitimate reason for such models, which directly affect consumers in their daily lives, to be kept proprietary.

Akshat was there too, from Occupy the SEC, and he asked about the Volcker Rule.

Condray took notes. I mean, what’s he going to say.

Well actually sometimes he did say stuff, like to Akshat, and for the most part it was something along the lines of, “that is not in our jurisdiction”, although there was one exception when he talked about how Walmart, being a retailer, is not in his jurisdiction but since it’s acting as a banking institution it actually is.

Overall I’m a bit disappointed. Although I did certainly like the fact that he held a town hall meeting at all, I am worried that he’s just too nice, and that he’s going to try to please everyone and be kind of wishy-washy. I would have loved to see him manage to sustain disgust at the abuses he was hearing about, but instead he sounded more concerned than angry, and I would put my money on angry any day. I want the CFPB to be led by a son-of-a-bitch that pisses people off and constantly tried to enlarge his jurisdiction rather than keeping well inside the lines. Time will tell.

#OWS Alternative Banking update

Crossposted from the Alternative Banking Blog.

I wanted to mention a few things that have been going on with the Alternative Banking group lately.

- The Occupy the SEC group submitted their public comments last week on the Volcker Rule and got AMAZING press. See here for a partial list of articles that have been written about these incredible folks.

- Hey, did you notice something about that last link? Yeah, Alt Banking now has a blog! Woohoo! One of our members Nathan has been updating it and he’s doing a fine job. I love how he mentions Jeremy Lin when discussing derivatives.

- Alt Banking also has a separate suggested reading list page on the new blog. Please add to it!

- We just submitted a short letter as a public comment to the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau regulation which gives them oversight powers on debt collectors and credit score bureaus. We basically told them to make credit score models open source (and I wasn’t even in the initial conversation about what we should say to these guys! Open source rules!!):

Today is Volcker Day

This is a guest post by George Bailey, who is part of Occupy the SEC. I just want insert here a congratulations to Occupy the SEC for submitting their public comments letter yesterday, and to point out that the organization SIFMA below is the same SIFMA I mentioned here and here (those guys are everywhere, defending the interests of the banks).

Today is “Volcker Day” and Paul Volcker was on a tear.

Mr Volcker added in a formal submission to regulators Monday that “proprietary trading is not an essential commercial bank service that justifies taxpayer support,” and that banks should stop “stonewalling.”

He went on:

“There should not be a presumption that evermore market liquidity brings a public benefit,” Volcker, 84, wrote in a letter submitted yesterday to regulators in defense of the rule curtailing banks’ bets on asset prices with their own money. “At some point, great liquidity, or the perception of it, may itself encourage more speculative trading (see here and here for the full story).

But then Jamie Dimon came along and bitch slapped Tall Paul. Ouch.

“Paul Volcker by his own admission has said he doesn’t understand capital markets,” Dimon told Francis in the Fox Business interview. “He has proven that to me.”

SIFMA, on behalf of the industry, took over to explain in detail just what it is that Mr. Volcker doesn’t understand in their comment letter. They reiterate their dire warning about the devastating effects on ‘corporate liquidity’’ from the Volcker Rule. Yet surprisingly, no non-financial corporate bond issuers filed any comments to acknowledge or object to this danger.

In fact, there are no comment letters from any non-financial companies. They did haul out the widely lampooned Oliver Wyman study to bolster their comment that ‘corporate’ America would suffer horribly if Volcker is enacted. But that just serves to remind us again that the corporate bond liquidity that will be affected is the liquidity in dodgy financial company ‘corporate’ bonds, like CDOs and other drek. They conclude the only solution is a rewrite . They request the rule makers go back and start all over again.

The SIFMA comment letter runs to 175 pages. I haven’t read all the other financial company letters, but the ones I’ve skimmed conform to SIFMAs position.

The Occupy the SEC comment letter logs in at 325 pages and oddly enough draws the exact opposite conclusions to each of SIFMAs objections. It’s an interesting contrast. For some reason (some familiarity with the subject matter and public interest primarily) the group seems to have understood and articulated Volcker’s (and the electorate’s) intent pretty effectively.

Of the comment letters received about 90% are from financial institutions, and another 5% are from foreign governments objecting to the priority the US regulators have gifted to US traders in US Government Bonds. The remaining 5% are from ordinary folks, like Mr. Volcker, Occupy the SEC and other public interest groups.

Its interesting that 95% of the comments reflect the views of the 1%, and the views of the 99% are embodied in the comments of the remaining 5% of commenters. I’m confident the regulators will recognize that, for all its complexity, the rules are comprehensible and can be refined to serve the public’s demand for control over a runaway financial system.

Mathematics has an Occupy moment

The Occupy Wall Street movement means a lot of things to a lot of people, but one of the things it pretty much universally represents is the concept of agency.

Instead of sitting passively by and allowing a dysfunctional system to detract from a culture, the participants in Occupy want to object, to reform the system, and if that doesn’t work, to build a new system. And the crucial point is that they feel that they have the right (if not obligation) to do so. Moreover, they wish to construct a new paradigm built on democratic understanding of the shared goals of the system itself, rather than letting whomever is in power decide how things work and who benefits.

I feel like there’s an analogy to be drawn between this process and what’s happening now in the fight between mathematicians and Elsevier, and for that matter the publishing world (as has been pointed out, Springer has the same issues as Elsevier, even though people like Springer a lot more).

It may seem like the fight against Elsevier is only a small part of the mathematics system, in that it’s really only one publisher of many, and some people (like the journal of Topology) have already gone ahead and started new journals that don’t share the more toxic properties that the Elsevier journals have. I don’t think that narrow view is justified.

In fact, part of tearing down Elsevier has to include a broader understanding of how antiquated the entire academic publishing world is, which immediately begs the question of what we need to build to replace it. This is not unlike the Occupy movement’s goal to replace the current financial system with another which would primarily serve the needs of the citizens and only secondarily the desires of bankers. A tall order to be sure, but luckily for mathematicians their system is less complicated, and moreover the community is much more empowered.

Why am I waxing so poetic over this struggle? Because, at the heart of the question of “what is the new system” is the even more fundamental question, “what do we, as a community, wish to treasure and what do we wish to discard?”. After all, we already have arXiv, or in other words a repository of everything, and the question then becomes, how do we sort out the good stuff from the crap?

I want to stop right there and examine that question, because it’s already quite loaded. Let’s face it, people don’t always agree on what it means for something to be good versus crap, and if there was ever a time to examine that question it’s now.

Here’s a thought experiment I’d like you to do with me. Since leaving academic mathematics, I’ve realized the enormous value of being able to explain mathematical concepts to broader audiences, and I’ve been left with the distinct impression that such a skill is underappreciated inside academic mathematics. In the past 8 months, since writing this blog, I’ve become sort of a hybrid mathematician and journalist, and it’s kind of cool, if unfocused. But what if I decided to really focus on the journalism side of mathematics inside mathematics, would that be appreciated?

So the thought experiment is this. Imagine if, every 6 months, I moved to a new field of mathematics and acted as a mathematical journalist, interviewing the people in math about their work, their field, where it’s going, what the important questions are, etc., and at the end of the 6 month gig I wrote an expository article that explained that field to the rest of the mathematicians. I’d do that every 6 months for 20 years, and I’ve covered 40 fields. Assuming I’m as good at explaining things as I say I am, I’ve really opened up these fields to a larger audience (albeit still math folks), which may allow for better communication between fields, or may avoid redundant work between fields, or may simply enrich the understanding of what’s going on. From my perspective, the work I’d be doing would really be mathematics, and would further the overall creation of mathematics.

However, think about those expository articles I’d be writing. They wouldn’t be original, nor would they be particularly hard- if anything the goal would be for people to understand them. Would they ever get published in a top journal (as of now)? I don’t think so. And please don’t suggest that papers like this, written by famous people in their fields, have been well-received. This is true but I claim more a result of the reputation of the writers than because of the content.

Let’s go back to the question of how we sort papers on arXiv. For some people, this question is really confusing and even scary. They fear that any system besides the one now in place would devalue contributions that are more technical, harder, and less accessible over results that are easy, flashy, and amenable to pop culture sound bytes. I exaggerate for effect, but this is the gist of worries I’ve been hearing. For these people, which I will call “the traditionalists”, the most they want to do is to circumvent the publishers’ fees but otherwise keep intact the referee system, whereby there are gatekeepers who choose experts to anonymously review papers. The publishers are the organizers of this system, and by inviting people to be editors for their journals essentially anoint the gatekeepers.

I actually think those traditionalists should be afraid, but not exactly for the reasons that they think. Instead of worrying that their hard, technical papers won’t be appreciated, they should worry that other, totally different kinds of skills will be appreciated. Of course in the end it’s the same result, namely that the top universities may not forever be populated exclusively by people who prove wonderfully difficult, original and ground-breaking results. They could also include people who are the great story-tellers of mathematics and are appreciated for their gifts of understanding and disseminating mathematics, as well as their broad understanding of the field.

In other words, a democratic system actually looks different from a oligarchy, and that’s not necessarily bad, although the oligarchs may think it is.

I’m going to make a prediction, namely that there will be two different systems in place in 15 years. Neither will involve traditional publishers, but one of them will keep that refereeing system intact whereas the other will be more of a crowd-sourced referee system. Maybe it will be something like this idea of Yann LeCun, for example. Maybe it will be better for women. That would be cool.

By the way, I want to be clear that I’m not suggesting all papers are written equally. There really are people who make huge contributions to their fields through proving hard, creative theorems. I just think there are also people who contribute to mathematics in other ways, that also require hard work and excellent skills. And there aren’t just two skills, of course; I just simplified matters for this discussion.

The discussion of the future of academic publishing is raging, as I posted about here. And that discussion is really important in itself, and the fact that so many people are participating in it, and figuring out the shared values of the mathematics community, is democracy in action. I fully believe we are witnessing a historic moment, and it’s weirdly, and happily, happening without police intervention, pepper spray, or drum circles.

#OWS upcoming events

Here ye, here ye, there will be an Occupy Town Square event this coming Saturday. Please come and help us reconstruct Zucotti Park inside a church at 86th and Amsterdam for the afternoon. Here’s the flyer:

Also, there will be a march from Liberty Plaza to the Fed and the SEC to celebrate very own Occupy the SEC’s submission of their Volcker Rule public comments, next Monday, February 13th, at 4:30pm.

Here’s the schedule:

4-430pm: Assemble at Liberty Plaza

5pm: March to the Fed (33 Liberty Street )

5:30pm: March to the SEC’s NY Office (3 World Financial Center, Suite 400)

Finally, the Alt Banking working group now has a twitter feed.

Alternative Banking in FT Alphaville (#OWS)

Alt Banking’s opinion piece about too-big-to-fail was published yesterday in FT Alphaville.

Woohoo!

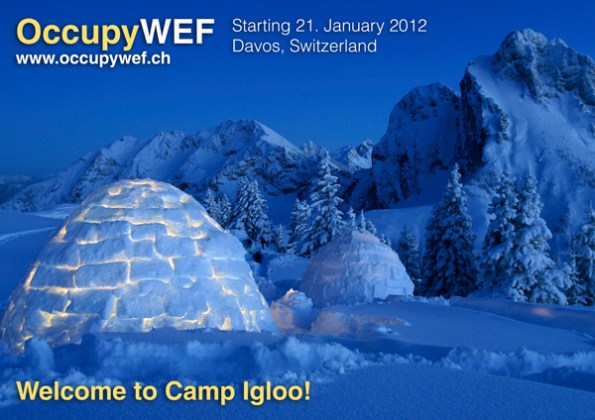

Occupy the World Economic Forum

How’s it going with the Volcker Rule?

Glad you asked.

Recall that Occupy the SEC is currently drafting a letter of public comment of the Volcker Rule for the SEC (for background on the Volcker Rule itself, see my previous post). I was invited to join them on a call with the SEC last week and I will talk further about that below, but first I want to give you more recent news.

Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism wrote this post a couple of days ago talking about a House Financial Services Committee meeting, which happened Wednesday. Specifically, the House Financial Services Committee was considering a study done by Oliver Wyman which warned of reduced liquidity if the Volcker Rule goes into effect. Just to be clear, Oliver Wyman was paid by a collection of financial institutions (SIFMA) who would suffer under the Volcker Rule to study whether the Volcker Rule is a good idea. In her post, Yves was discussed the meeting as well as Occupy the SEC’s letter to that Committee which refuted the findings of Oliver Wyman’s study.

Simon Johnson, who was somehow on the panel even though it was more or less stuffed with people who wouldn’t argue, had some things to say about how much it makes sense to listen to people who are paid to write studies in his New York Times column published yesterday. He also made lots of good arguments against the content of the study, namely about the assumptions going into it and how reasonable they are. From Simon’s article:

Specifically, the study assumes that every dollar disallowed in pure proprietary trading by banks will necessarily disappear from the market. But if money can still be made (without subsidies), the same trading should continue in another form. For example, the bank could spin off the trading activity and associated capital at a fair market price.

Alternatively, the relevant trader – with valuable skills and experience – could raise outside capital and continue doing an equivalent version of his or her job. These traders would, of course, bear more of their own downside risks.

If it turns out that the previous form or extent of trading existed only because of the implicit government subsidies, then we should not mourn its end.

The Oliver Wyman study further assumes that the sensitivity of bond spreads to liquidity will be as it was in the depth of the financial crisis, 2007-9. This is ironic, given that the financial crisis severely disrupted liquidity and credit availability more generally – in fact this is a major implication of the Dick-Nelson, Feldhutter and Lando paper.

If Oliver Wyman had used instead the pre-crisis period estimates from the authors, covering the period 2004-7, even giving their own methods the implied effects would be one-fifth to one-twentieth of the size (this adjustment is based on my discussions with Professor Feldhutter).

CSPAN taped the meeting, which was pretty long, but I’d suggest you watch minutes 50 through 57, where Congressman Keith Ellison took some of the panel to task for being, or acting, super dumb.

For whatever reason, Occupy the SEC wasn’t invited to the panel. You can read their letter that argues against Wyman’s study, which is on Yves’s post, or you can read this comment that one of the members of Occupy the SEC posted on Johnson’s NYTimes piece (“OW” refers to Oliver Wyman, the author of the paid study):

Your testimony at the hearings yesterday was a refreshing counterpoint to the other members of the panel.

On top of the flaws in the OW analysis you covered in the article, there was another misleading point that the OW report purported to prove.

The study focused on liquidity for corporate bonds, which SIFMA/OW characterized as ‘financing american businesses’ . But a quick review of the outstanding corporate bonds in the study reveals that the lions share of corporate bonds are CMOs and ABS. Additionally, the study reports that the majority of the holdings of corporate bonds are in the hands of the finance industry.

As a result the loss of liquidity anticipated by the SIFMA folks will mostly impact them, not the pensioners and soldiers (and their Congressmen) the bankers were trying to scare with the OW loss estimates.

If the banks are forced to withdraw as market makers for this debt, replacement market makers won’t enter until these bonds trade at much lower levels. These losses are currently stranded (and disguised) in the banking system, and by extension are inflating the value of the funds invested in these bonds.

It’s critical that the market making rules are clarified to ensure that liquidity provision for these instruments is driven out of the protected banks and into a transparent market where the mispricing will be corrected and the losses will be properly recognized.

So just to summarize, the Congressional committee listened to the results of a paid study talking about how bad the Volcker Rule would be for the market, when in fact it would be good for the market to be uninsured and realistic.

I’m not a huge fan of the Volcker Rule as it is written, but these are really terrible reasons to argue against it. To my mind, the real problem is that, as written, the Volcker Rule is too easy to game and has too many exceptions written into it.

Going back to the call with the SEC (and with Occupy the SEC). I haven’t kept abreast of the details of the Volcker Rule like these guys (they are super relentless), but I did have some questions about the risk part. Namely, were they going to end up referring to an already existing risk regulatory scheme like Basel or Basel II, or were they creating something separate altogether? They were creating something separate. They mentioned that they weren’t interested in risk per se but only to the extent that wildly fluctuating risk numbers expose proprietary trading, which is the big no-no under the Volcker Rule.

But here’s the thing, I explained, the risk numbers you are asking for are so vague that it’s super easy, if I’m a bank, to game this to make my risk numbers look calm. You don’t specify the lookback period, you don’t specify the kind of Value-at-Risk, and you don’t compare my risk model worked out on a benchmark portfolio so you really don’t know what it’s saying. Their response was: oh, yeah, um, if you could give us better wording for that section that would be great.

So to re-summarize, we have “experts”, being paid by the banks, who explain to Congress why we shouldn’t let the Volcker Rule go through, and in the meantime we’ve assigned the SEC the job of writing that rule even though they don’t know how to game a risk model (there’s a good example here of JP Morgan doing just that last week).

One last issue: when we asked about why repos had been exempted sometime in between the writing of the statute and the design of the implementation, the SEC people just told us we’d “have to ask the Fed that”.

Sunday Links

What do an upscale nightclub for Wall Streeters and the People’s Library from #Occupy Wall Street have in common? Turns out, nothing.

Someone thinks we can cure accounting shenanigans by rotating accounting firms. I’m not convinced.

I like this story from Matt Taibbi about one of the biggest assholes in the world.

For whatever reason I can’t get enough of this picture from a recent car show:

High Frequency Trading and Transaction Taxes

If you look at this list of the 20 biggest donors of the 2012 election, and you scroll down to number 20, you’ll find out stuff about Robert Mercer:

Robert Mercer is co-CEO of the $15 billion hedge fund company Renaissance Technologies. In 2009, according to the New York Daily News, he accused a builder of overcharging him $2 million for a construction project in his mansion—a “museum-quality” model train display “about half the size of a basketball court.” During the 2010 midterms, Mercer was outed as the funder behind $300,000 worth of attack ads targeting Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.). In the 2012 election cycle, he and his wife Diana have given $150,000 to the Republican National Lawyers Association and $100,000 to the free-market super-PAC Club for Growth Action.

Total giving for 2012 race: $384,100

• Giving to outside-spending groups: $260,000

• Giving to candidates and parties: $124,100

First, if I’m the model train set guy from above, I overcharge Mercer $2M and hope that he’s too embarrassed to sue me. And I am wrong.

Second, let’s look a bit more into the attack ads against DeFazio. Why is he spending so much time to work against this guy? Oh maybe this explains it. DeFazio was trying to impose a small transaction tax to curb high frequency trading, and Renaissance Technology, where Mercer works, makes their money through high frequency trading on the futures exchanges:

Capitol Hill Democrats introduced legislation today that would impose a tax on financial transactions in order to curb high-frequency trading and force Wall Street to contribute a bigger share to the federal budget.

A measure written by Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, and Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., would place a 0.03% levy on financial trading in stocks and bonds at their market value. It also would cover derivative contracts, options, puts, forward contracts and swaps at their purchase price.

So this is how politics works. As Sarkozy mentioned in this Bloomberg article where he was discussing imposing a similar transaction tax in France:

“If France waits for others to tax finance, then finance will never be taxed,” Sarkozy said today in a speech in the eastern French city of Mulhouse.

It seems like the Harkin/DeFazio transaction tax bill is still alive, for now. What’s so worrisome about it? To find out I registered to read this article from Investment News (registration is free), which starts out quite nicely:

Hark: Beware of Harkin tax plan

Investors, beware of the financial transactions tax proposed by Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, and Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore. The tax may appear to have no chance of adoption at present, with the Republicans in control of the House and in position to block many proposals in the Senate, but the situation could change after the 2012 elections.

If Barack Obama retains the presidency and the Democrats regain control of both houses of Congress, we could see a tax on securities trades, especially if the passions evidenced by the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations remain high.

Woohoo! I love it when people are afraid of Occupy Wall Street, especially when they think they are only talking to their insider friends. After explaining the scope of the tax (again, 3 cents on 100 dollars), the article goes on:

In a breathtaking display of economic ignorance, Mr. Harkin declared: “This measure is not likely to impact the decision to engage in productive economic activity. There’s no question that Wall Street can easily bear this modest tax.”

Does Mr. Harkin not realize that customers, not Wall Street, would pay the tax? As opponents of the proposal argue, the proposed levy — effectively, a sales tax — would increase the cost of investing and be passed on to the ultimate customer, not absorbed by the brokerage firms, hedge funds and other professional traders at whom it is nominally aimed.

In effect, it also is a tax on liquidity. As anyone who has studied economics knows, when you tax something, you get less of it, so the result would be less liquid markets and more-costly transactions.

The article then goes on to warn that such a tax would move business offshore:

Finally, a transactions tax might drive trading and investing offshore to financial centers, such as Singapore or Dubai, that don’t impose such taxes. Academic research suggests that after the imposition of a transactions tax, market volatility would rise, while trading volume —and with it, liquidity — declined.

Just in case you’re not sufficiently worried yet, the article makes some further scary suggestions, which bizarrely allows for the fact that the current plan is benign:

Other dangers regarding the transactions tax proposal are that the low initial tax rate, 0.03%, might be absorbed by investors without too much pain, leading it to be raised quickly to a more burdensome and damaging rate.

That is what happened with the income tax in the U.S., and, more recently, with the value-added tax throughout Europe.

Another danger is that a transactions tax could be extended quickly to other financial transactions, including credit and debit card transactions, checks and bill payments. These likely would be even more damaging to economic activity.

The financial services industry should continue to resist the financial transactions tax, even at the proposed low rate. Once the camel’s nose is in the tent, the whole camel soon follows.

I asked a quant friend of mine what he thought of this article, and he said the following:

I’m personally not a huge fan of transaction taxes because I guess I feel trades should be encouraged (people should, for example, be able to have an S&P500 account instead of a checking account, where you sell units of S&P each time you buy some milk) and in general tight spreads means more actionable information (in the sense of knowing whether a bank is solvent for example, or allocating resources to build a new power plant). In addition, they are often avoided at some additional cost to investors. In the UK, they have a stamp tax on equities, and as a result only a few people trade equities, and almost all funds trade “swaps” with some additional arb/copmlexity added to the system as a result.

That said, the doomsaying in the article is definitely overboard. It would certainly wipe out a lot of HF trading, which is of limited value to society (I think HF does make for better pricing, but the resources put into it might not match the societal benefit of the slightly more accurate prices).

This would cause some trading to go offshore. In the UK for example, various regulations were (a small) part of the reason ManU decided to list in Singapore. The loss in capital gain taxes are from a bunch of sources, but one of the major ones is sure to be deferred sales, meaning the taxes would just be paid later.

It does make some sort of intuitive sense to match the costs associated with overseeing transactions paid for by the transactions though. If you feel that financial transactions are burdensome and need more regulation, the people who are causing that burden should pay. Whether that should be via a transaction tax or by a profit tax or by an exchange/regulatory fee, I don’t know.

(You know my bias, that it’s really the hidden transactions that are the main issue, and so I think if anything you should be taking financial intermediaries for having illiquid/non-tradable assets on their books rather than encouraging them to have more of it).

I’m left kind of rooting for the transaction tax, personally, and it’s not just because I want to see Mercer miserable; it can be seen as a tax that most people will not notice but people who make enormous number of bets will be affected by. On the one hand, this means it’s a truly progressive tax, and on the other hand, it means you will actually need to think a trade is worthwhile before making it.

CBC Radio

If you are in Canada, or if you can figure out how to stream CBC Radio 1 online, then you can hear me talk #Occupy Wall Street stuff this morning at 8:30am Eastern time on their show The Current.

update: there’s a recording of the interview here. I was on with David Sauvage, a very cool man who created this commercial.

#OWS news

First, wanted to make sure people know we are having an #OWS Alternative Banking Working Group meeting today; the announcement is here. Topics on the agenda so far are:

Please come!

Next, Occupy the SEC, which is preparing public comments for the Volcker Rule, has a new blog post which examines other public comments and asks what the regulators’ actual goals are in writing and implementing the Volcker Rule. From the post:

It appears that many pundits and Asset Managers assume that a priority of the regulators writing the Volcker rules is to maintain the status quo in spite of the statute. In fact, their arguments actually strengthen the regulators’ hand to change the status quo. Simply put, the proprietary trading and market making definition need to be tightened.

Finally, I was in Boston yesterday and ran into two small #OWS demonstrations in Harvard Square, one in Brattle Square and the other in Harvard yard. It was great to connect with these guys, they are doing great work. For example, the Harvard occupiers told me that the investment banks no longer attempt to recruit on campus, which is a huge win and needs more attention. Right on!

#Occupy Wall Street course at Columbia University: update

I wrote this post a few days ago after I found an announcement of a Columbia University course on Occupy Wall Street. Unfortunately it looks like the course is not going to be held (according to Bwog).

However, it does look like NYU is going to offer an #OWS course, according to this article in the Gothamist.

It takes imagination to be boring

I suffer from a lack of imagination.

I have been so inculcated in the necessary complexity of finance and banking, that I’ve lost touch with some basic, simple realities. I have been brainwashed by the half-assed and lame attempts at regulation by the elements of the Dodd-Frank bill, losing myself in the details of the Volcker Rule for example, and I’ve lost the forest for the trees. I’m spending my time furiously figuring out how to allow banks to have all of their goodies (CDS, derivatives, repos, etc.), but not let them eat so much they get themselves (and us) sick.

Sometimes you need imagination to be boring.

Luckily, there was an op-ed article in the New York Times yesterday which served as a wake-up call. The article is called “Bring Back Boring Banks” and it’s written by Amar Bhide. I kind of feel like quoting the entire article, since it’s all so good, but I’ll make do with this part (emphasis mine):

Guaranteeing all bank accounts would pave the way for reinstating interest-rate caps, ending the competition for fickle yield-chasers that helps set off credit booms and busts. (Banks vie with one another to attract wholesale depositors by paying higher rates, and are then impelled to take greater risks to be able to pay the higher rates.) Stringent limits on the activities of banks would be even more crucial. If people thought that losses were likely to be unbearable, guarantees would be useless.

Banks must therefore be restricted to those activities, like making traditional loans and simple hedging operations, that a regulator of average education and intelligence can monitor. If the average examiner can’t understand it, it shouldn’t be allowed. Giant banks that are mega-receptacles for hot deposits would have to cease opaque activities that regulators cannot realistically examine and that top executives cannot control. Tighter regulation would drastically reduce the assets in money-market mutual funds and even put many out of business. Other, more mysterious denizens of the shadow banking world, from tender option bonds to asset-backed commercial paper, would also shrivel.

This is what we need to do. Thank you Amar Bhide, for having the clarity to say it.

#Occupy Wall Street course at Columbia University

Columbia University’s Anthropology department is offering a course on #Occupy Wall Street. You can see clever announcements in this Gothamist article and this Bwog post.

I’ve already contacted the instructor, Hannah Appel, and invited her students to join the Alternative Banking Working Group on Sunday afternoons. She seems very psyched to join us and have her students join us. Here’s the syllabus for her course.

Please spread the word about our working group. We are working on lots of different projects around reforming the current financial system. You don’t need to be an expert in finance to come.

The sin of debt (part 3)

I wrote here about the way normal people who are in debt are imbued with the stigma of immorality, whereas corporations are applauded for debt (and even for declaring bankruptcy). I admit that my second post, which contained outrageous examples of the ideas in the first post, was rather frustrated, because I had little in the way of solutions. I like to propose solutions rather than just point out problems.

First, I’ve got some good news. Namely, as described in this Wall Street Journal article, a judge has ruled that the debt collection agency harassing an elderly woman for her dead husband’s debt was indeed harassment. From the article:

The case could set a precedent across the U.S. and discourage lenders from using collectors to get money from surviving relatives on debts left behind by the deceased, according to other state-court judges.

That’s something!

Next, I’ve been discussing the language of debt with various people and we’ve come up with a plan. This language issue was the main point of my first post: the words we use make individuals feel dirty when they are indebted, but sanitizes the concept of debt for corporations (“restructuring”).

Let’s turn this around. Let’s come up with our own vocabulary to separate the issues and also to point out what brings people into debt in the first place. We’ve come up with three proposed vocabulary terms to add to the discourse:

- Poisonous debt: this is debt that comes from actually fraudulent lenders, or who lent to vulnerable people under false pretenses. Actually existing laws should be taking care of these things, but the problem is of course that people who are in massive amounts of debt typically don’t have good lawyers.

- Debt under duress: this term should refer to debt that people incur in emergency situations, like medical emergencies, divorces, or funerals. Elizabeth Warren has done a lot of work describing how many families in serious money trouble got there with exactly this kind of situational debt.

- School system debt: the school system in this country is inconsistent, which causes enormous competition for families to buy a house in a good school district, often buying houses they can’t quite afford for the sake of their childrens’ educations. This is well-documented and, for any individual, totally understandable.

What I like about the above terms is that they separate the people who take on the debt from the reasons they take on the debt. Anyone can relate to the above reasons, and when that happens, a sympathy, rather than a moral judgement, emerges. If I hear someone has taken on debt under duress, I immediately want to know if they’re ok.

They also provide a much-needed balance to the typical argument you hear against people who bristle at the idea of debt amnesty, namely the concept of free-loaders milking the system for cheap cash to spend on unnecessary trinkets and then not paying it back.

If you understand the extent to which people are in debt because of health issues, your response may be something more like, hey we should really make the health care system in this country more reasonable. In other words, it starts a much more interesting and potentially useful conversation than mere finger wagging.

Matt Stoller explains politics

I’ve never understood politics, partly because they’re complicated, partly because the people who do understand politics are so heavily involved they don’t know how to contextualize for people like me. I’ve come to think of it as a lot like finance, where there’s power to be had by withholding information, and part of that power is wielded simply by inventing a new vocabulary that makes people on the outside feel tired and hopeless. You really need a tour guide, a translator, to walk you through stuff to achieve a decent level of understanding.

I now consider Matt Stoller my personal translator. Matt regularly contributes to Naked Capitalism, my go-to blog for informed, vitriolic insights into the corrupt world of finance. His recent post on Naked Capitalism concerning Ron Paul and liberals beautifully explains how confused modern liberals are when confronted by someone like Ron Paul, who is both unattractive and on their side for a number of reasons. I confess that I’ve been that confused liberal myself at many an #OWS Alternative Banking Working Group meeting, when the Ron Paul fans come and talk about Fed transparency.

But Matt doesn’t just tell a good story, although he does that. He also give you insight into the process of politics. He peppers his story with helpful, nerdy explanations like this:

An old Congressional hand once told me, and then drilled into my head, that every Congressional office is motivated by three overlapping forces – policy, politics, and procedure. And this is true as far as it goes. An obscure redistricting of two Democrats into one district that will take place in three years could be the motivating horse-trade in a decision about whether an important amendment makes it to the floor, or a possible opening of a highly coveted committee slot on Appropriations due to a retirement might cause a policy breach among leadership. Depending on committee rules, a Sub-Committee chairman might have to get permission from a ranking member or Committee Chairman to issue a subpoena, sometimes he might not, and sometimes he doesn’t even have to tell his political opposition about it. Congress is endlessly complex, because complexity can be a useful tool in wielding power without scrutiny. And every office has a different informal matrix, so you have to approach each of them differently.

Another recent Stoller post that really blew my mind was How the Federal Reserve Fights, which explained Matt’s experiences as a Senior Policy Advisor to Alan Grayson, a congressman on the Financial Services Committee in 2009-2011. Grayson teamed up with Ron Paul to force more transparency at the Fed. It’s an awesome story, but my favorite part, because I’m such a nerd and I love my nerd heroes, is the following:

When it gets down to crunch time, as a staffer going up against a big force of lots of lawyers, you get really tired and cut corners. One obstacle in legislating is that it is really hard to tell what bills do, because they have multiple provisions like “In Section 203, delete “do” and replace with “shall”. You have to constantly reference pieces of the code and compare changes, which gets confusing. It’s like doing “track changes”, but on paper and with multiple versions. This is a problem software could easily solve and I’ve heard that agencies and (probably the Fed) have such software. But I didn’t. So the Fed thought we would do nothing more than cursory reading of Watt’s amendment, and rely on their validators who told us the amendment would increase transparency. And this is where Grayson showed legislative genius. We were exhausted, but he got all the difference pieces of the law, and spent a few hours deciphering exactly what this amendment meant. And he figured out that not only did the amendment not open up the Fed facilities to independent inspection, it actually increased the secrecy of the Fed. If you want the gory details, here’s Grayson’s argument during the markup.

I’m kind of wishing Matt Stoller would write a book about “How Politics Works,” but then again does anybody read books anymore? Is it better for him to just continue to write timely blog posts? I’ll take what I can get.

Information loss

When people ask me why the financial system is so complicated, I always say the same thing: because it benefits the insiders of the financial system to make it that way. The more complicated and opaque something is, the more opportunities to extract fees and withhold information. Or rather, to withhold information in order to extract fees.

In some sense you can think of the financial system as a huge “information loss” system, where people get paid based on how much more information they know than you do. Incidentally, this theory flies in the face of most economic assumptions of transparency, and explains the origin of the phrase “dumb money.” And it’s not my idea, it’s kind of an elemental fact for insiders; I’m bringing it up because I want to make sure people are aware of it.

As an analogy, think of the situation when you buy a used car from someone. They tell you some things, like its make and model, and they may let you test drive it, but you end up not knowing how many accidents it’s been in, and stuff like that. Your partial information in general lets them make money.

It’s kind of understandable why there’s so much insider trading going on. Insider trading is the ultimate and most efficient way to profit from information.

Another good example of information loss is with mortgages, and mortgage-backed securities. The original idea behind securitizing mortgages was that investors get to buy pieces of pools of mortgages, which “behave better” than individual mortgages: whereas an individual can refinance (and often does, when interest rates go down) or default, it’s less likely that a majority of the people in a pool refinance or default.

[Let’s ignore for now the issue that the banks got so high on the profits of securitization that the assumption of better behavior of pools got thrown out the window as the underlying mortgages became worse and worse – a gleaming example of information loss.]

In selling these pools, the banks were charging fees so that you, the investor, wouldn’t have to “deal with the details” of all of the individual mortgages in the pool. This is one way that people withhold information and charge a fee for it, by calling it a chore.

And it is a chore, if you actually do it. However, in the case of mortgages, lots of banks charged that fee for that chore and then never actually did the chore– they kept terrible accounts of the mortgages, and when they started to default in large numbers, started illegally pretending their papers were in order, through “robo-signing,” in order to foreclose quickly.

Here’s something you can do if you have a mortgage. Demand to see your mortgage note. It turns out there’s a legal way for you to ask your bank to trace the ownership of your mortgage through the securitization system, and you can do it for fun, you don’t need to be late on your mortgage payments or anything.

There does seem to be a risk associated with asking to see your note, however, namely to your credit score, which is bullshit. There’s also a form letter of complaint if your bank somehow doesn’t come up with the answer.

Need your vote

Footnoted needs your vote on the most outrageous handout to executives in 2011. Here are the candidates:

- MF Global agreeing to pay then-CEO Jon Corzine a $1.5 million retention bonus months before the company imploded.

- Clear Channel Media Holdings paying $3 million a year to a company controlled by Bob Pittman so that Pittman can fly in a Mystere Falcon 900 that Pittman owns for both business and personal use.

- Leo Apotheker collecting around $25 million in severance and other benefits from Hewlett-Packard, including relocation back to France or Belgium after less than a year on the job.

- IBM’s outgoing CEO Samuel Palmisano becoming eligible for as much as $170 million in retirement benefits, just by waiting until he was past 60 to announce his retirement.

- Nabors Industries agreeing to pay outgoing CEO Eugene Isenberg $100 million in severance on his way out the door.

Vote here.

Also, please read a letter to Jamie Dimon that I enjoyed, from the Reformed Broker blog. From the letter:

So please, do us all a favor and come to the realization that the loathing you feel from your fellow Americans has nothing to do with your “success” or your “wealth” and it has everything to do with the fact that your wealth and success have come at a cost to the rest of us. No one wants your money or opportunities, what they want is the same chance that their parents had to attain these things for themselves. You are viewed, and rightfully so, as part of the machine that has removed this chance for many – and that is what they hate.