Archive

#Occupy Wall Street meeting and news

First, I wanted to mention that there will be an Alternative Banking meeting on Sunday from 3-5pm at 1401 IAB (14th floor of the International Affairs Building), Columbia University. This is on the corner of Amsterdam and 118th. Please come!

Next I wanted to mention that I’ve been hearing from other occupied cities, namely Occupy Oakland and Occupy LA. I’ve been meeting the most amazing people this way and I’m super grateful for that. I should be talking to Cheryl from Occupy LA later today, and it sound like her posse of occupiers have really been making things happen with something called the “Responsible Banking Measure” recently passed by the LA City Council. Awesome stuff, and I’ll post more as I learn it. My favorite part was the last line of her email, “let’s do this!”

Another inspiring figure is coming from Occupy Oakland, a photographer named Miles Boisen, whose trademark phrase, “struggle and snuggle,” is very close to my heart. He recently met a group of four protesters who were so fascinating that he asked them to tell a bit more about their story. First, here’s their picture:

Next, here’s one of their stories:

Dear Myles,

It was wonderful to meet you at the time and place we did. I am happy to give you some background information. Feel free to use it (or not) any way you like.

I was born in San Francisco in 1944, the year that millions of Jews were being slaughtered by Hitlers minions in Europe. My mother, Hodee Edwards, is Jewish. My father, Harvey Richards, is of Welsh ancestry. I witnessed the 1950s in the streets of Oakland, watching my mother crying over the Rosenbergs execution, and experiencing the racism of our world through the eyes of my African American step father (George Edwards) and my sister (Lou Edwards). I dodged the FBI coming to my house to harrass my family and witnessed doors being slammed in the FBI’s faces as they sought to intimidate dissidents in Oakland. I traveled to the USSR in the summer of 1961, the year I graduated from high school, to help my father and his wife, my stepmother Alice Richards, make two films on ordinary life in the USSR. See this for a clip from that movie.

I entered UC Berkeley in the fall of 1961 and immediately joined the civil rights movement. My first demonstrations were against compulsory ROTC at Berkeley, a struggle that resulted in the cancellation of compulsory ROTC in my sophmore year. I participated in the sit-ins at Mel’s drive-in restaurants (see this for a clip of my father’s film showing those demos and a shot of me on the picket line), at the Sheraton Palace Hotel (see this which includes a shot of me being dragged out of the lobby by the SFPD) and along auto row on Van Ness in San Francisco in 1963 and 1964 against racial discrimination in hiring, then rampant all around the bay area. I spent 2 months in the San Francisco County Jail in San Bruno in 1966 for my efforts.

I resisted the draft from my graduation in 1966 when I was classified 1A to 1969 when the draft board just gave up on me and never sent me another nasty letter. See this for a slide show of events that took place on the day I was drafted (but slipped out of their grasp), Oct 18,1967 during the Stop the Draft Week events on the very same street Occupy Oakland’s general strikers walked down last Tuesday.

As you can see the events of those years are still very alive for me through the work I have done archiving my father’s film collection (see this). I have kept the memories of those movements alive because I believe in them now as I did then. So, for me, the Occupy Oakland movement is a dream come true. It finally gives voice to the cry for justice and sanity that has been silenced for so long under the hegemony of the Republican and Democratic Parties ever since the election of the crook, Richard Nixon, and continuing until the present day with the election of the most recent fraud, Obama the bomber.

I rejoice at the outpouring of outrage from our youth. They have made it possible for me to switch from the tiny minority who over the past 40 years have dissented against the American empire, to the 99% who are dissenting today. What a relief. I don’t know where this movement is headed nor how long it will last. But I do know that it has my whole hearted support and that it opens the door to ten thousand possibilities. I am in awe that I lived to witness it. Since I am retired now, my future plans are to continue to manage Estuary Press and the Harvey Richards Media Archive and to make sure that we do not forget our history, even as we are making it right now.

I guess you can’t call this brief, but I tried my best.

Thanks for asking, and hoping you don’t regret it,

Paul Richards

Gaming the system

It’s not easy being a European bank right now. Everyone is telling them to boost capital, otherwise known as raise money, exactly at the time that much of their investments are losing value on the market because of the European debt crisis.

If I were the person running such a bank, I’d be looking at fewer and fewer options. Among them:

- Ask China for some of their money

- Ask investors for some of their money

- Ask a middle eastern country for some of their money

- Cut bonuses or dividends

- Change the way I measure my money

Of the above possibilities, 5) is kind of attractive in a weird way.

And guess what? That’s exactly the option that the banks are choosing. According to this article from Bloomberg, the banks have suddenly noticed they have way more assets than they previously realized:

Spanish banks aren’t alone in using the practice. Unione di Banche Italiane SCPA (UBI), Italy’s fourth-biggest bank, said it will change its risk-weighting model instead of turning to investors for the 1.5 billion euros regulators say it needs. Commerzbank AG (CBK), Germany’s second-biggest lender, said it will do the same. Lloyds Banking Group Plc (LLOY), Britain’s biggest mortgage lender, and HSBC Holdings Plc (HSBA), Europe’s largest bank, both said they cut risk-weighted assets by changing the model.

“It’s probably not the highest-quality way to move to the 9 percent ratio,” said Neil Smith, a bank analyst at West LB in Dusseldorf, Germany. “Maybe a more convincing way would be to use the same models and reduce the risk of your assets.”

Ya THINK?!

European firms, governed by Basel II rules, use their own models to decide how much capital to hold based on an assessment of how likely assets are to default and the riskiness of counterparties. The riskier the asset, the heavier weighting it is assigned and the more capital a bank is required to allocate. The weighting affects the profitability of trading and investing in those assets for the bank.

One reason I couldn’t stomach any more time at the risk company I worked at is things like this. We would spend week after week setting up risk models for our clients, accepting whatever they wanted to do, because they were the client and we were working for them. Our application was flexible enough to allow them to try out lots of different things, too, so they could game the system pretty efficiently. Moreover, this idea of the “riskiness of counterparties” is misleading- I don’t think there is an actual model out there that is in use and is useful to broadly understand and incorporate counterparty risk (setting aside the question for now of gaming such a model).

For example, the amount of risk taken on by CDS contracts in a portfolio was essentially assumed to be zero, since, as long as they hadn’t written such contracts, they were only on the hook for the quarterly payments. However, as we know from the AIG experience, the real risk for such contracts is that they won’t pay out because the writers will have gone bankrupt. This is never taken into account as far as I know- the CDS contracts are allowed for hedging and never impose risk on the overall portfolio otherwise. If the entity in question is the writer of the CDS, the risk is also viciously underestimated, but for a slightly more subtle reason, which is that defaults are generally hard to predict.

Here’s not such a crappy idea coming from Vikram Pandit (it’s in fact a pretty good idea but doesn’t go far enough). Namely, standardize the risk models among banks by forcing them to assess risk on some benchmark portfolio that nobody owns, that’s an ideal portfolio, but that thereby exposes the banks’ risk models:

Pandit is championing an idea to make it easier to compare the way banks assess risk. To accomplish this, he wants to start with a standard, hypothetical portfolio of assets agreed by regulators the world over. Each financial institution would run this benchmark collection through its risk models and spit out four numbers: loan loss reserve requirements, value-at-risk, stress test results and the tally of risk-weighted assets. The findings would be made public.

Then, Pandit wants the same financial firms to run the same measures against their own balance sheets – and to publish those results, too. That way, not only can investors and regulators compare similar risk outputs across institutions for their actual portfolios, but the numbers for the benchmark portfolio would allow them to see how aggressively different firms test for risks.

I think we should do this, because it separates two issues which banks love to conflate: the issue of exposing their risk methodology (which they claim they are okay with) and the idea of exposing their portfolios (which they avoid because they don’t want people to read into their brilliant trading strategies). I don’t see this happening, although it should- in fact we should be able to see this on a series of “hypothetical” portfolios, and the updates should be daily.

As a consumer learning about yet more bank shenanigans, I am inspired to listen to George Washington:

The Numbers are in: Round 1 to #OWS

This is a guest post by FogOfWar:

CUNA (a trade industry group for credit unions) just announced that at least 650,000 customers and USD $4.5 Billion have switched from banks to credit unions in the last five weeks. I think this is a pretty impressive showing for the lead up to “Bank Transfer Day”, and, as posted before, am a supporter of the CU transfers. A few quick points on the announcement:

Are those numbers driven by “Move Your Money” or BofA’s $5 Debit Fee?

A little of both, I suspect, and there’s no hard survey data (that I know of) splitting it out. The two points aren’t completely separate, as one of the points of “move your money” (at least in my mind) is to let people know that credit unions generally have lower fees than large commercial banks & it often makes financial sense to shift your account over regardless of your political views on “Too Big To Fail (TBTF)”.

So is 4.5 Billion a lot or a little?

It isn’t a big number in the scope of overall deposits, but it’s a really big number for transfers in just one month. For scale, the total deposits in all 11,000+ CUs nationwide are somewhere around $800Bn, and that’s roughly 10% of the total deposits in the US. So $4Bn (to make the math easy) is a 0.5% increase in deposits for CUs and somewhere around a 0.05% reduction in the deposit base of US banks in the aggregate. I suspect the transfers are concentrated in the large “final four” banks (BAC, JPM, C, WFC which, if memory serves, account for somewhere around 40% of deposits), so the reduction might be closer to 0.10% for the TBTF quartet.

Wait, those seem like really small percentages—why do you think this matters?

Well, because it’s a greater increase in deposits in one month than credit unions (in aggregate) got in the entirety of last year (and last year was a good year for CUs in which they saw their market share increase). People (rightly) don’t change their checking accounts lightly (there’s a lot of “stickiness” to having direct deposit/ATM cards/etc.—in short it’s a pain in the ass to change your financial institution), so this is a pretty impressive number of people and amount of deposits in this span of time.

Also (and this will play out over time), this could be the start of a trend. Certainly there seems to be a large uptick in discussion of “move your money”, and, as the idea percolates around there’s a lag between thought an action, so this well could be a slow build.

“A Slow Deliberative Walk Away from the TBTF Banks.”

Another important point is that, in fact, you really don’t want too many people moving their accounts in a short period of time for two reasons. First, a rush of people all removing their deposits at the same time is, in fact, a “run on the bank”. This is destructive for a host of reasons—in particular it can cause the institution on which there’s been a run to go into bankruptcy (regardless of whether that bank is otherwise solvent), and, let’s not forget, we the taxpayer are ultimately on the hook for the deposits of bankrupt commercial banks through the FDIC, which is funded by bank fees but backed by the full faith and credit of the taxpayer (and a BofA bankruptcy might put that backstop to the test). So, much as I disagree with many of the decisions of the mega banks, I don’t want the “move your money” campaign to be a catalyst for their insolvency proceedings.

Instead, what I’d really like to see is a slow steady whittling down of their deposit base, and thus their overall size, until they are no longer considered “to big to fail” and thus pose no danger to the taxpayers, as they will be free to make good or bad decisions and live or die, respectively, by them. In short, I’d like to see a “slow deliberative walk away from the TBTF banks” playing out over the course of the next 2-3 years.

The other reason is that credit union’s can only take deposits at a certain pace without running into issues with their own capital buffers and operations. This is a slightly technical issue, but with a substantive point behind it. In essence, absorbing a large growth in new deposits takes some time, not just from an operational perspective (ramping up staff, at a certain point opening new branches and ATMs), but also because more capital needs to be accumulated to provide a safety buffer for the additional deposits that have been taken on. From this perspective, the $4.5 Bn in 5 weeks is a “goldilocks” level—not to much to overheat, not too little to be a rounding error, but just right (OK, actually think it could be 2-3 times the pace without overheating, but everyone else loves to use that hackneyed “goldilocks” metaphor and I just felt peer pressure to frame it that way).

I read that it won’t have an impact on the banks—is that true?

In a word, “total fucking bullshit”. The deposit base is the skeleton of a bank—it’s what holds the whole thing together. Deposits are steady (essentially) free money. Money that can be deployed wherever the bank finds interesting at the moment: loans to customers, speculative exotic derivatives, new branches, foreign investment, whatever. Moreover, if retail deposits mean so little to banks, then why in the world do they spend so much advertising coin chasing them? Generally for profit institutions advertise for products that are profitable to them, not one’s that are irrelevant. QED.

That’s true over the long term. It is worth noting, however, that at this exact moment in time the banks are flush with cash sitting idle on deposit with the fed. http://www.cnbc.com/id/44019510/Bank_of_New_York_Puts_Charge_on_Cash_Deposits Which, by the way, makes it perfect timing for the “move your money” campaign. As I said before, I really don’t want a “run” on the banks, and the fact that banks are flush with cash currently means they’re relatively safe in the immediate moment from a loss of deposits.

But the real reason you’re still seeing Chase commercials on TV even though they’re flush with cash doing nothing at the Fed, is that Chase knows that most people rarely change their primary checking accounts. The accounts that are moving over now are (statistically) gone for good. Later, when that flush cash at the Fed is no more and the banks want the easy money of a wide retail deposit base, they’ll find it very difficult to bring those people back. Not because credit unions are really awesome, just because people really don’t like switching accounts—BofA has to spend a lot of energy to bring in a new account from another institution and doesn’t actually care if it brings it in from lower east side people’s or from Citibank (money is fungible).

Lastly, and perhaps most important, the primary checking account is the primary point of entry to our financial lives. Big banks like the free money you give them on deposits, but equally much they like the chance to have your credit card business, your mortgage and car loan business, your insurance business, your investing business and possibly your retirement and college savings business. All that ancillary business can be (and very much is) statistically quantified on a per-account average basis. All those cross-sells add up over time to big numbers.

FoW

#OWS meeting tomorrow

I’ve been busy writing my speech for the Open Forum today. Finally finished it just now. I’m going to do it with Andrew, who’s also involved in the Alternative Banking working group. I’m very impressed with the work he and other people are doing for this group, it’s inspiring to see how much people care. I’ve been told that the Open Forum will be videotaped and put on YouTube- stay tuned for the link to that!

One outcome of all that hard work is that we found a place to meet! We’re meeting Saturday (tomorrow) from 4 to 6pm at the Community Church of New York, located at 28 East 35th Street. Hopefully we will have skype set up for people to call in. For skype details keep an eye on the Alternative Banking webpage. That webpage also has the minutes of our last meeting as well as the invitation to this one, complete with a questionnaire that we put together to make the actual meeting more productive.

It also looks like after that we have a room at Columbia reserved for a few Sundays, which is also very awesome.

Sorry for the incredibly boring post. It’s actually really exciting but I don’t imagine that’s coming through. I actually do have plenty of things to say about other stuff, specifically how crazy I’d be if I were an unemployed Greek person right now, but I’m really lacking in time and sleep so I will have to let Floyd Norris from the New York Times say those things:

There is little reason to think that Greek citizens will be more cooperative now that it has been made clear their opinions are irrelevant to the people who run Europe.

#OWS Alternative Banking meeting today

I’m excited to go to the second meeting today of the Alternative Banking working group, whose web page is still a work in progress. We’re meeting at 3pm at Carne Ross’s office.

Dial-in instructions:

At 3 PM Eastern Standard Time (in the US), please dial: (530) 881-1000

When you are asked to enter the conference code, enter this: 451166

Then hit the pound key (#).

Last week we set up an ambitious agenda for ourselves. After passing the “Move your Money” campaign to Alternative Economy (because they are already on it), we decided to focus on two things:

1) What are the legislative steps we think need to be made to fix the current system? To this end the discussion has been centered on commenting on the Volcker Rule, which the public can do until January 13th.

2) Reimagining our current financial system – what would it look like where our deposits, our retirements, and small businesses weren’t being held hostage by a few powerful banks and corporations? Much of this discussion will probably be centered on how things used to work in this country and how things work or worked in other countries.

In the meantime, I’ll share some great links with you:

- Credit unions are seeing a surge in new members.

- When you hear “recapitalization of banks,” what does that mean?

- How do CDS’s work, and what is going to happen in Greece if their 50% haircut counts as a default?

- My hero judge Jed Rakoff tells the SEC to do their job.

- More background on Jed Rakoff.

- A former derivatives guys explains where Wall St. went wrong and comments on #OWS.

- Trick-or-treating tips for #OWS sympathizers

Data Science and Engineering at Columbia?

Yesterday Columbia announced a proposal to build an Institutes for Data Sciences and Engineering a few blocks north of where I live. It’s part of the Bloomberg Administration’s call for proposals to add more engineering and entrepreneurship in New York City, and he’s said the city is willing to chip in up to 100 million dollars for a good plan. Columbia’s plan calls for having five centers within the institute:

- New Media Center (journalism, advertising, social media stuff)

- Smart Cities Center (urban green infrastructure including traffic pattern stuff)

- Health Analytics Center (mining electronic health records)

- Cybersecurity Center (keeping data secure and private)

- Financial Analytics Center (mining financial data)

A few comments. Currently the data involved in media 1) and finance 5) costs real money, although I guess Bloomerg can help Columbia get a good deal on Bloomberg data. On the other hand, urban traffic data 2) and health data 3) should be pretty accessible to academic researchers in New York.

There’s a reason that 1) and 5) cost money: they make money. The security center is kind of in the middle, since you can try to make any data secure, you don’t need to particularly pay for it, but on the other hand if you can find a good security system then people will pay for it.

On the other hand, even though it’s a great idea to understand urban infrastructure and health data, it’s not particularly profitable (not to say it doesn’t save alot of money potentially, but it’s hard to monetize the concept of saving money, especially if it’s the government’s or the city’s money).

So the overall cost structure of the proposed Institute would probably work like this: incubator companies from 1) and 5) and maybe 4) fund the research going on in (themselves and) 2) and 3). This is actually a pretty good system, because we really do need some serious health analytics research on an enormous scale, and it needs to be done ethically.

Speaking of ethics, I hope they formalize and follow The Modeler’s Hippocratic Oath. In fact, if they end up building this institute, I hope they have a required ethics course for all incoming students (and maybe professors).

Hmmm… I’d better get my “data science curriculum” plan together fast.

What’s your short list of actionable complaints?

After reading this article from the New York Times about what Volcker says still needs to be done about the financial system (the title of his speech was “Three Years Later: Unfinished Business in Financial Reform”), I’m wondering if he wants to join the #OWS Alternative Banking working group. He’s got his own “short list of actionable complaints” list, not that different from mine:

- make capital requirements for banks tough and enforceable,

- make derivatives more standardized and transparent,

- ensure auditors are truly independent by rotating them periodically,

- end too big to fail,

- create and enforce reserve requirements and capital requirements for money market funds, and

- get rid of Fannie and Freddie, or at least make a plan to.

He also pointed to the weakness of the ratings agencies as one of the big reasons for the credit crisis, so I assume that “making the ratings agencies accountable” may be on the list too, at least in the top 10.

I was interviewed last night about being on the Alternative Banking working group for #OWS (I will link to the article if and when it comes out), and I mentioned this speech as well as the general fact that many of these problems named above are really non-partisan, especially “Too Big to Fail”. This column from the New York Times, written by former IMF chief economist Simon Johnson points this out as well.

That makes me encouraged and depressed at the same time. Encouraged because there really does seem to be a consensus about what’s terribly wrong with at least some of the most obvious issues, but depressed because in spite of this we haven’t solved any of them. To make this vague sense of depression precise, just take a look at what has happened to the original “Volcker Rule”: it has expanded by a factor of 100, from 3 to 300 pages, making it impossibly difficult to understand or probably to follow (unless you have fancy lawyers who do nothing else besides find loopholes). It’s reminiscent of our tax code. Speaking of which, here’s yet another “short list of actionable complaints” to fix that.

I’m enjoying how many people are now coming up with personal short lists of actionable complaints (even if it’s in response to complete stalemate of the political process). It’s a way of claiming and maintaining our freedom and agency. It isn’t as easy at is seems, because you have to sort out the important from the annoying, and the actionable from the existential. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to write your own short list, and feel free to post it here.

Shareholder Value

This is a guest post by Mekon:

It was late August, 1990. The barely-above-mediocre Boston Red Sox (record: 73-57) led the definitely-mediocre Toronto Blue Jays (record: 67-64) by 6½ games in the American League East. Unsure his team could hold off the hard-charging Jays with a month left in the season, Sox general manager Lou Gorman decided to shore up his bullpen. He offered the Houston Astros a young minor league prospect named Jeff Bagwell for aging-but-competent relief pitcher Larry Andersen. The Astros, long out of the race, said yes. What happened next is the stuff of legend, sort of:

- In September, the Sox went from flirting with mediocrity to wrapping it in a loving embrace (a 15-17 record down the stretch), but still managed to hold off the mighty Jays by 2 games.

- As the Sox staggered to the division title, Andersen chipped in 22 innings in 15 games with 1 save and a good ERA (1.23). If you believe in the Win Shares statistic they quote here, Mr. Aging-but-Competent contributed the equivalent of about 1 win.

- In the playoffs, the 88-74 Red Sox faced the defending World Series champion Oakland A’s (record: 103-59). The A’s won all four games, by an aggregate score of 20-4. Andersen pitched three innings and gave up two runs. He was charged with the loss in the first game when he gave up a run in the 7th inning of a 1-1 game just before the A’s broke the game open.

- The A’s, overwhelming favorites to repeat as World Series champs, lost the Series to the 91-71 Cincinnati Reds in four straight. You never know, do you, baseball fans?

- Andersen was declared a free agent after the season ended. He left the Sox, signed with the San Diego Padres, and pitched in the majors for another four years. Somewhere along the way, “aging-but-competent” became just “aging,” as he compiled an aggregate record of 8-8.

- The Astros promoted Bagwell to the major leagues in 1991. He was the 1991 rookie-of-the-year, the 1994 MVP, and the face of the franchise for 15 seasons. He retired with an exceptional lifetime OPS (On-base Plus Slugging average, today’s batting statistic of choice) of .948, as well as 449 home runs, currently 35th of all time. In his first year of Hall of Fame eligibility (2011), he got about 40% of the vote, a figure dragged down by suspicions of steroid use.

- In later years, Gorman appeared to look back on the trade with pride: “I called Bob Watson and made the trade, Bagwell for Andersen. Andersen would strengthen our bullpen and help us win the Eastern Division title, and we’d go on to face the A’s,” Gorman would write. “He was exactly what we needed to bolster the pen at a critical juncture in our run at the division title.”

- Red Sox fans and ownership agreed. At the Sox’ 1990 holiday dinner, owner and chair Jean Yawkey announced a $2.5M bonus for Gorman for “enhancing ticketholder value” by getting the team to the playoffs. Grateful fans gave him a loud ovation on Opening Day the following April. While a few cranky Boston Globe writers made fun of the Bagwell-for-Andersen trade over the next few years, the public didn’t buy it. As the Sox finished well out of the running each of the next four years, fans always found comfort in the thrilling playoff run of 1990.

OK, I made that last one up: everyone, except apparently Gorman, realized almost from the outset that trading away Bagwell for Andersen was a disaster. As the Sox stumbled through the next several years (see, I didn’t make it all up), poor Lou, who had actually had a pretty good career as a major league GM, became a laughingstock, finally losing his job in 1993. His name still shows up near the top of any “Worst Trades Ever” list that baseball writers feel obligated to make every year around the trading deadline. You could even argue that teams became more cautious about holding on to their minor league prospects after seeing how badly Gorman and the Sox screwed up.

All well and good. But what if I told you that outside sports, in the world of business and finance, the little piece of fiction I put at the end of the Bagwell-for-Andersen story actually isn’t fiction at all?

Shareholder value. Google the phrase and you’ll find almost 5 million links. Virtually all of them (or at least the first five I checked) equate it with the value of the firm or the share price. If you think that’s just a shortcut, it’s not: at the end of every year, companies whose stock grew in price that year give their CEO’s hefty bonuses for – you guessed it – boosting shareholder value. The trouble with all this is that it misses the dimension that Sox fans demanding Lou Gorman’s head understood very well: time.

Say you’re a shareholder in IBM. Maybe you bought (or received) your stock outright, or maybe you gave some money to a manager and had them buy the stock, either directly in your name or pooled with money from other people just like you (i.e., through a fund). Either way, you are, in financial parlance, an asset owner (as distinguished from an asset manager, who manages what you, the owner, hold).

But step back a bit: why do you own this asset, anyway? You’re not going to consume it, like you might a gallon of milk or a car. You don’t get any pleasure from it, like you might from a piece of art that hangs on the wall. The only reason to own a share of IBM is so you can sell it. Hopefully at a high price. And if you own IBM stock now to sell it later, you have to think about time. When will you sell it? Five minutes from now? Five years from now?

When you’ll sell is driven by why. Essentially, there can be two reasons:

- You want to spend the money. You sell your IBM shares and use the proceeds to buy a car, or a house, or a nice picture, or to send your kids to college. A variant of this is that you expect to need the money soon (your kids are going to college next year), and you don’t want to risk IBM decreasing in value, so you sell your shares and put the money in the bank (or in another low-risk asset) until you need it.

- You (or an asset manager acting on your behalf) decide to replace IBM with an asset you like better. Time is embedded implicitly here too: if you’re selling IBM to buy AAPL, you expect AAPL to do better than IBM over some time horizon. Which could be until you need the money, or it could be sooner. For example, I might plan to hold AAPL for a year (over which time I expect it to do better than IBM), and reevaluate what I hold after that.

Asset owners who sell because of (1) are called buy-and-hold investors. Asset owners who sell because of (2) are called traders. Rebalancing, where you hold assets for some period of time, then decide whether to replace them, is essentially a disciplined form of trading.

Now that we know why asset holders sell, we can talk about when. Take buy-and-hold investors first. If you’re selling assets to fund expenses, you’re usually either buying something big (a house or a car, not a gallon of milk) or you no longer have income (you’re retired). Now, truly large expenses are rare, and people usually retire late in life, so asset sales by buy-and-hold investors are spread out across time. In any given year, only a small minority of buy-and-hold investors need to sell assets to raise funds.

Traders initially seem more complicated, and probably are. But we can capture them pretty well by saying they sell when they see a new asset they think will get them better future returns. The more they like the return profile of an asset they already hold, the more they behave like buy-and-hold investors.

Now let’s ask again: what is true shareholder value? Given what we know about asset owners, what is in their best interest? A related question: who benefits when the stock price goes up? Shareholders, surely. But that’s only half the answer. The full answer is shareholders who sell.

Let’s look at buy-and-hold investors first. If the stock price goes up over a year, it benefits investors who sell that year. The remaining investors realize the gains only to the extent that those gains persist when they sell. Since they sell at different times, there’s only one way to benefit them as a group: enhance the value of the company consistently over time.

Of course, once you realize that boosting the share price over the short term doesn’t actually enhance value for most shareholders, you also see that immediate stock price gains are a terrible measure of a CEO’s performance. Red Sox fans understood this right away, and did all they could to run out of town the guy who boosted the short-term stock price (likelihood of making the 1990 playoffs) at the expense of long-term value (Jeff Bagwell’s career).

If you don’t believe me, here’s Warren Buffett making a related point:

“If you expect to be a net saver during the next 5 years, should you hope for a higher or lower stock market during that period? Many investors get this one wrong. Even though they are going to be net buyers of stocks for many years to come, they are elated when stock prices rise and depressed when they fall. This reaction makes no sense. Only those who will be sellers of equities in the near future should be happy at seeing stocks rise. Prospective purchasers should much prefer sinking prices.”

Now, this doesn’t mean you should manage a company to make the stock price drop, in part because there’s a big difference between existing shareholders and prospective ones. But the intuition is the same: investors should worry about the stock price when they buy and sell, and at no other time, and CEO’s should worry about shareholder value across time, not in the short term.

We know, though, that not all asset owners are buy-and-hold investors. Does the presence of traders – whether disciplined rebalancers, day traders, or high-frequency hedge funds – change things? Should it make management pay more attention to short-term stock price movements?

Let’s start with the basics: when you own an asset, its price matters only when you sell, and traders sell when another asset has a better return profile (or when they need to raise funds). Ignoring the latter, and assuming other assets’ profiles don’t change, we conclude that a rising stock price benefits traders if it comes with a worsening future return profile. (By the way, rapidly rising asset prices do usually mean worse expected future returns – but that’s a longer discussion.) That’s clearly no way to run a company, but it’s worth articulating two important reasons why:

- It harms the rest of their shareholders, who plan to keep their shares for longer and want a good future return profile (duh).

- In the aggregate, it even harms short-term traders. Remember, we’re taking asset owners’ points of view here, and even asset owners who are traders need to get their long-term returns from somewhere!

In a little more detail, imagine a world where all companies are managed for the (supposed) benefit of short-term traders, maximizing short-term stock price growth and (purposely or not) making longer-term growth prospects less attractive. So now a year (say) goes by, and all stock prices have gone up a bunch (i.e., there’s a bubble). Asset owners who are traders want to take their profits and invest in another asset that’s more attractive in the long-term – but what? If all companies focus on short-term profit, then all assets are worse in the long term. So, as an asset owner, you’ve made some money, but what are you going to retire on?

Put another way, there’s no way to trade out of the economy – from a global point of view, everyone’s a buy-and-hold investor. If companies manage for the benefit of short-term traders, even traders lose.

So why do we keep rewarding CEO’s for short-term stock price boosts? Every Red Sox fan knew Lou Gorman was mismanaging the team, so why can’t the best minds in business and finance see it? Or does something about the system pervert perspectives and incentives? I’ll take that on in another post.

Credit Unions in NYC flyer

Also from FogOfWar; see also this post where FoW discusses “Why Credit Unions?”:

Why Credit Unions? (#OWS) (part 1)

This is a guest post by FogOfWar. See also the “Credit Unions in NYC flyer“.

Moving your money from a megabank to a credit union or community development bank makes for a good sound bite, but is it really an action that can have an impact in the right direction? I think so (although the matter is not free from doubt), and thought it would be worthwhile to lay out thoughts on the subject as a follow-up to the “What is a Credit Union?” post.

I’ll focus this discussion on credit unions, rather than community development banks or smaller locally owned banks as that’s where my knowledge lies.

Credit Unions are not Too Big To Fail

A quick google search indicates the largest credit union in America is Navy FCU with $34Bn in assets. (Internationally, it may be the Dutch Rabobank, although I’ve never gotten a good handle on whether Rabo is still a cooperative or not.) Individual credit unions fail regularly, just like individual banks, but there isn’t one CU that’s in danger of crashing the entire financial system in the same manner as BAC, C, JPM or WF.

During the 2008 crisis and aftermath the only credit unions that got a federal bailout were the corporate credit unions. There’s a good article about that here. The corporate credit unions definitely got into trouble buying structured products and I don’t want to gloss this fact over. There’s a split between the retail credit unions, who are going to have to pay for these mistakes, and the corporate credit unions which made the bad investments as well as the NCUA, who was asleep at the switch when the corporate CUs were making that investment. Also worth noting that the NCUA has filed suit against the banks for selling crap product to the corporate CUs.

The corporate credit union bailout was small proportionate to the overall credit union size. $30 bn of gov’t backed bonds equates to $270 bn proportionate for banks—less than ½ of the official state of TARP and a small fraction of the overall size of the taxpayer support given to the large (non-CU) banks indirectly through TAF, TSLF, PDFC, TARP, TALF, etc.,… (see this for an explanation of term).

All in all, I’d say CUs come out somewhat ahead by this measure.

Volker Rule/Glass Steagall

Unlike commercial banks, credit unions never revoked the Glass Steagall act and remained segmented as “pure” traditional banking entities. This means that CUs don’t mingle traditional banking (deposits, checking accounts, loans to customers), with investment banking activities (IPOs, M&A advisory) or derivatives trading or sales desks, let alone prop desk frontrunning of client information.

There’s a lot of ink out there on Volker and Glass Steagall. In short, it seems like a good idea, if not sufficient as a complete solution, to keep traditional banking segmented from investment banking and proprietary trading. The core point is that trading risk should not infect the core banking business putting it (and the taxpayer standing behind the federal deposit insurance) at risk. Very good recent example of this here.

CUs come out dramatically ahead on this measure.

Lobbying—just as bad?

Credit Unions do lobby, largely through two groups, CUNA and NAFCU. In fact, NAFCU has been an opponent of the CPFB, and the CU lobby got itself removed from the debit swipe fee cap.

There was a time I can remember when CUNA and NAFCU just went up to the hill to remind Congress that they existed and defend against the ABA’s occasional attempts to change the tax status of CUs. It seems times have, rather unfortunately, changed.

Regrettably, no advantage to Credit Unions here.

Part 2 will talk about investments in local communities, democratic control (the good, the bad and the ugly) and securitization/mortgage transfers.

FoW

Some really terrible ideas

I’m in the middle of writing up my talk about “math in business”. Turns out I can talk faster than I can type, since it’s taking me much longer to write this up that in took for me to say.

In the meantime I want to share with you some really terrible ideas I’ve seen in the news lately.

The prize goes to this idea of how to make the ratings agencies better in Europe. Namely, by banning them when they don’t like them. From the Wall Street Journal article:

In a press conference, Barnier acknowledged this was a “difficult” issue and said that Europe needed to “reduce its dependency on ratings.”

While Barnier gave no further details on the idea of banning some sovereign ratings, a person familiar with the situation explained when the ratings suspension or ban could be appropriate.

The official said the ban would only be used in a “specific” set of circumstances.

That could include if the consequences of a ratings move led to “volatility” or a threat to financial stability. The person also said that the ratings could be banned if there were “imminent changes to the creditworthiness of a state because of negotiations” on a bailout program.

It would be one thing if we had gotten the overall impression that the ratings agencies have been exaggerating a problem through their sovereign ratings… but I don’t have that impression, do you? Um, I have an idea, instead of banning them, how about we instead force them to explain their reasoning? How is turning off the heart rate monitor going to help the patient?

Next up, I just want to say how much I hate articles with misleading titles like this one. Now that I link to it I realize the title has been changed from “Jobless Claims in U.S. Dropped Last Week” to “Jobless Claims in U.S. Decreased Last Week.” This is slightly better but I’ll still complain: the drop from 409,000 to 403,000 is clearly not statistically significant, as anyone who knows any statistics could see just by how small that relative shift is. But even worse if you read the article, you’ll see that last week’s numbers had come in at 404,000 at this week had been corrected to 409,000. So the actual news should have read “U.S. Jobless Claims Changed Not At All”. I guess that’s not a snazzy title.

Here’s not such a bad idea: making people own the underlying sovereign bonds if they buy CDS contracts on them. I’ve seen enough damage cause by “not knowing where the CDS’s live” with regard to Greek debt to know that uncontrolled selling of CDS contracts needs to be curbed – even better if we can make people transparent about their holdings, of course, but that’s kind of a pipe dream.

However, you’ll notice in the article that it’s kind of a weird rule, where countries can “opt out” of the ban if they want to. When would they want to do that? From the Bloomberg article:

The opt out-clause won over some critics of possible bans.

“I never signed up to the belief that a ban on uncovered sovereign CDS would have any positive impact,” Syed Kamall, who represents London in the EU Parliament, said in an e-mailed statement. “However, I’m reassured that member states will have the ability to opt out of the ban, if they see signals that sovereign debt markets are distressed.”

So, I’m guessing that means that some people think that when nobody’s willing to buy their bonds, they will become willing if they can find some A.I.G.-like entity that is willing to sell CDS contracts on those bonds for way less than they’re worth? I don’t get it. Please explain if you do.

And also I don’t like how this idea of no naked CDS contracts is being lumped in with the idea of no short selling- maybe because there’s also the word “naked” associated with that? Let’s not get confused: naked short selling is already illegal. But short selling itself isn’t and shouldn’t be.

David Graeber on Occupy Wall Street

Could I love David Graeber any more? He wrote a fantastic book which I’ve blogged about here just in case you missed it.

Check out his account, cross posted from Naked Capitalism, on being one of the original Occupiers of Wall Street (I feel like I should have guessed this but I didn’t).

I hope he gets onto the Alternative Banking working group.

Alternative Banking System

I just got invited to join the Alternative Banking System working group from Occupy Wall Street. It’s run by Carne Ross, who has written a book called the Leaderless Revolution. I’m excited to meet the group this coming weekend. It looks like there will be many interesting and unconventional thinkers there.

I got back last night from my Cambridge, where I spoke to people about doing math in business. I will write up my notes from that talk soon and post them, and they will include my suggestions for how to prepare yourself to be a data scientist if you’re an academic mathematician. This is a first stab at a longer term project I have to define a possible “data science curriculum”.

What is a Credit Union? (#OWS)

This is a guest post by FogOfWar:

There’s been a call (associated with the “Occupy Wall Street” movement) for consumers to move their bank accounts from large TBTF banks into local credit unions. Nov. 5th is the target date. This is a similar message to one Arianna Huffington gave a few years back.

The above inspire a quick post on the subject of “What is a Credit Union and why is it different from a mega-bank?”

What can I do at a Credit Union?

Pretty much all the same stuff you can do at a bank. They have checking accounts (although they call them “share accounts”, it’s the same thing), savings accounts, CDs, credit cards, debit cards, auto loans, mortgages, lines of credit. All of the stuff a normal bank offers. Some of the smaller CUs (just like some of the smaller banks) don’t offer everything, but it’s substantially the same.

The only difference in services is that you generally can’t make investments (stocks, bonds, etc.) through your credit union. IMHO, this isn’t much of a downside, as the brokers associated with major banks generally aren’t as good as the standalone retail brokers (like Fidelity, Vanguard, TIAA-CREF, etc.)

The other difference is that you can’t just walk off the street and open a credit union account; you have to be eligible in their “field of membership” (more on that below).

How are the rates?

It varies, but in general you’ll get better rates at a credit union than at a bank (certainly than at a megabank). An easy way to check is to look at your checking account statement now (or call your bank) and see what the APY is (Annual Percentage Yield), and then check the credit union to see the APY on their basic share draft account.

There are credit unions with sucky rates out there (often the really small ones—they have a lot of operational costs), but I’ve usually found that I get better rates on savings and better rates on loans from a CU.

What’s the real difference?

The real difference is ownership. Banks are owned by outside investors—usually people who own the stock for a big bank—and they need to pay those owners a profit in the form of dividends (or share repurchases which are economically equivalent). Credit Unions are owned by their depositors (called “members”). That’s why the “checking account” is called a “share account”—you own a “share” (another name for stock) in the credit union. The board of directors is elected at an annual meeting, one person, one vote. BoD members are not paid for serving on the board.

This also explains why Credit Unions can offer better rates: they don’t have to pay a profit to their stockholders, instead that “profit” is returned back to you, the owners. Note that CUs are also exempt from corporate tax, and this makes some difference, but IMHO, it’s the absence of needing to pay dividends that really gives CUs the ability to pay better rates to their customer/owners.

Am I supporting the community when I deposit with a Credit Union?

There’s a good argument that yes, you are. Credit Union’s make loans back to the people in their membership. So the money you put on deposit is being leant back to people in the community of the credit union. Credit unions don’t trade derivatives or run speculative investment books. By and large they make loans to members and then hold on to those loans (i.e., they don’t “securitize” those loans out to other people).

For those who know the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, it’s a pretty good description of how a credit union can work within a community. Technically the movie describes a Thrift (somewhat similar), but it could just as easily been about a CU.

Who is eligible to join a Credit Union?

Each credit union has a “field of membership”. Some are employment-based, so you are eligible if you or an immediate family member works at a certain place. For example, NBC has a credit union for its NY employees. Note that NBC does not own the credit union, the CU is owned by its members (one person, one vote), it’s just that the credit union is there for NBC employees.

Some credit unions are associational. A good example of this is church credit unions (which are pretty common). There are also Community Development Credit Unions, which are set in lower-income areas and anyone in the area can join (Lower East Side People’s FCU is a good example).

There are a number of educational credit unions—these vary, but often faculty, students, employees and alumni are all eligible to join. Again, note that the university does not own the credit union—the CU is owned by the members—it’s just the prerequisite to join that particular credit union.

How do I find a credit union I can join?

There are some “credit union locators” online, but the one’s I’ve seen kinda suck. I’d say try a Google search. So if you live in Boise, I’d search for “Boise Credit Unions”. You can also try www.ncua.gov, which will give you all the credit unions in a particular area. I tend to like the larger credit unions (at least $20m in assets), as they tend to have hit a size where they’re operationally more together (making mistakes on your money is no fun).

You can also ask at the HR department at your job “hey, does working here make me eligible to join a credit union?” If they say “no”, you can say “why not? Is anyone working on having us join up with a good CU?”

Are there any downsides?

There aren’t a lot of ATMs, so every time you need cash & use a bank ATM, you’ll be paying that ridiculous fee. This can definitely suck, although one way around it is to have a debit card and take cash back all the time when you buy stuff (there’s no charge for taking cash back on a debit card—it’s just a question of whether the merchant lets you do it, and most supermarkets and drug stores do).

Also, this makes depositing paper checks a pain in the ass: you actually have to put them in an envelope and mail them to the credit union. How did society function before we had the internet?

Also, if it’s a work credit union, you can check to see if they have a branch at your office—this can make things a lot easier.

Anyway, that’s a quick rundown. Sure I missed something, but I’ll drop it in the comments if I remember later.

Here’s a flyer I made for OWS which contains information on a few credit unions in New York City:

FoW

Wall Street and the protests

Today I want to update you on my involvement with the Occupy Wall Street protest and also make an observation about the defensive behavior we see by the Wall Streeters themselves.

Update

Yesterday after work I went back to the protests and looked around to offer a teach-in. Unfortunately it hadn’t been sufficiently organized: the contact who had originally invited me wasn’t around, and hadn’t confirmed with me on email, and nobody else knew anything. It was also very windy, threatening rain, and the noise of the drumming was overbearing. There were drumming circles on two of the four corners of the square, and in the other two corners there were already meetings going on. It would be great if the protests could restrict the drumming area so that people could actually talk.

However, I kind of suspected this would happen, so I wasn’t disappointed. I handed out some flyers with a few friends that met me down there, and I met a few new really interesting and engaging people. I got re-invited to give a teach-in by a very nice man named Rock, who took my information. Rock suggested a daytime talk sometime around noon, and this sounds about right. Hopefully this will pan out, but even if it doesn’t now I have a flyer to distribute and it’s a conversation starter if nothing else. One of my friends also suggested having a t-shirt made with the phrase, “ask me about the financial system” printed on it. I think this is a great idea. I will go back down and be involved when I can make the time.

Also, I wanted to share Matt Taibbi’s column about the protest. His five top demands have a lot in common with the ones we came up with here.

Act Crazy

You know how some people win fights even though they’re not big or strong? They act totally crazy and angry, and it works because it confuses their opponents. This is what I think the tactic of the big bosses on Wall Street is right now. They’ve got Tim Geithner talking about it:

“They react to what is pretty modest, common sense observations about the system as if they are deep affronts to the dignity of their profession. And I don’t understand why they are so sensitive,” Geithner said at a forum hosted by The Atlantic and the Aspen Institute.

We’ve also seen Paul Krugman address this:

Last year, you may recall, a number of financial-industry barons went wild over very mild criticism from President Obama. They denounced Mr. Obama as being almost a socialist for endorsing the so-called Volcker rule, which would simply prohibit banks backed by federal guarantees from engaging in risky speculation. And as for their reaction to proposals to close a loophole that lets some of them pay remarkably low taxes — well, Stephen Schwarzman, chairman of the Blackstone Group, compared it to Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

The overall idea is to act like they are the victims somehow. Actually there’s another article in Bloomberg about the Wall St suffering, which I find fascinating as a phrase, and which contains passages like this one:

Bankers aren’t optimistic about those gains. Options Group’s Karp said he met last month over tea at the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York with a trader who made $500,000 last year at one of the six largest U.S. banks.

The trader, a 27-year-old Ivy League graduate, complained that he has worked harder this year and will be paid less. The headhunter told him to stay put and collect his bonus.

Here’s the thing. They are suffering, in exactly the same way that a child who is spoiled suffers when they are told they can’t get a toy in a store that they want even though they have one at home just like it. But that’s not real need, that’s a temper tantrum. It’s the parents’ responsibility to ignore that kind of posturing and establish reasonable expectations. But the analogy becomes kind of painful here, because who are the parents?

I guess you’d want them to be the government, or the regulators, but the problem is that those groups have shown the same lack of imagination (or fear) of a new world as the people on Wall Street.

So even though the protests are disorganized and sometimes annoying, the very fact that they are putting pressure on the system to fundamentally change is why I will continue to support them.

Koo: don’t be surprised by the crappy economy

First I wanted to thank you for the wonderful comments I’ve been enjoying and compiling from my last post about what’s corrupt about the financial system and what should be done about it. Even if I don’t end up doing the teach-in (hopefully I will! In any case I’ll go down there, even if it’s just to try to set up the teach-in for a later date) I think this is a really fantastic and important discussion. I’m putting together a final list of issues tonight and I think I’ll make a flyer to bring tomorrow, so if I don’t actually conduct the teach-in (yet) I’ll at least be able to give the info booth the flyers.

And it’s not too late! Please keep the comments coming.

Today I want to start a discussion on Richard Koo’s book, which is about Japan’s so-called “lost decade” (a reader suggested this book to me, and it’s fascinating, so thanks! And please feel free to make more suggestions for my reading list).

You can actually get a pretty good overview of his book by watching this excellent interview by Koo. For those of you, like me, whose sound doesn’t work on their computers, here’s his basic thesis:

- After the housing bubble in Japan burst, a bunch of firms, banks and otherwise, became technically insolvent. This meant that, although they had cash flow, they owed more than their assets.

- Because they were insolvent, they didn’t maximize profits like in normal times; instead they minimized debts.

- In other words, they didn’t borrow money to grow their businesses, like you’d expect in normal circumstances, which is proved by looking at data showing that corporate borrowing went down even as interest rates lowered to zero.

- The CEO’s didn’t talk about this because they don’t want anyone to know they’re insolvent!

- Investors are also somewhat blind to this, because they typically look at growth and cash flow issues.

- Japan’s government made massive investments in order to cover the lack of private investments.

- Rather than this being a mistake, this was absolutely essential to the Japanese economy and prevented a massive depression.

- Moreover, the idea that Japan had a lost decade is false: actually, there was a lot going on in that decade (actually, 15 years) but people didn’t see it. Namely, the balance sheets were slowly improved over the entire economy.

- This is a lesson for us all: any time there’s a massive credit bubble which breaks, we can expect a balance sheet recession where behavior like this is the rule. The U.S. economy right now is an example of this.

I have a few comments about this. I wanted to mention that I’m only about halfway through the book so it’s possible that Koo addresses some of these issues but on the other hand the book was published in 2009 but was clearly written before the U.S. credit crisis was really full-blown:

- A friend of mine who recently traveled to Japan noted that the people there live extremely well. In fact, if he hadn’t been told that their country has been in recession for nearly twenty years then he’d have never guessed it. This supports Koo’s claim that the Japanese government absolutely did the right thing by bankrolling the economy when it did. It also brings up a very basic question: how do we measure success? And why do we listen to economists when they tell us how to define success?

- Not every country can do what Japan did in terms of investing in its economy, although the U.S. probably can. In other words, it depends on how other countries see your credit risk whether you can go ahead and bail out an entire economy.

- Some of the businesses in the U.S. are clearly not technically insolvent; we’ve already seen ample evidence of cash hoarding. On the other hand, I guess if sufficiently many are, then the overall environment can be affected like Koo describes.

- In general it makes me wonder, how many of the firms out there today are technically insolvent? How insolvent? How long will it take for those that are to either fail outright or pay back their loans? If we go by this article, then the answer is pretty alarming, at least for the banks.

In general I like Koo’s book in that it introduces a new paradigm which explains something as totally self-evident that had been mysterious. It’s pretty bad news for us, though, for two reasons. First, it means we could be in this (by which I mean stagnant growth) for a long, long time, and second, considering the hyperbolic political situation, it’s not clear that the government will end up responding appropriately, which means we may be in it for even longer.

What’s wrong with Wall Street and what should be done about it?

I am trying to figure out the top five (or so) most important corrupt and actionable issues related to the financial system. I’m going to compile this list in order to conduct a “teach-in” at the Occupy Wall Street protest next week. The tentative date is Wednesday, October 12, at 5:30pm.

I’d love to hear your thoughts: please tell me if I’m missing something or got something wrong or left something out.

The list I have so far:

- Investment bankers trading their books and taking outrageous risks which lead to government-backed bailouts because they are “too big to fail”. The related action in the U.S. might be the “Volcker rule” (i.e. reinstating something like Glass-Steagall); unfortunately it’s being watered down as you read this.

- Ratings agencies in collusion with their clients. The actions here would be changing the pay structure of the ratings agencies and opening up the methods, as well as having better regulatory oversight. We also need to change the structure of ratings agencies, and either make it easier to form an agency or make the agencies that already exist and have government protection actually accountable for their “opinions”.

- SEC and other regulators in collusion with the industry. The action here would be to nurture and maintain an adversarial relationship between regulators and bankers. We’ve seen too many people skip from the SEC to the banks they were regulating and then back. There should be rules against this (how about a minimum time requirement of 5 years between jobs on the opposite sides?). There should also be much better funding for the SEC and the other regulators, so they can actually meet their expanded mandate.

- Conflict of interest issues from economists and business school professors. If you’ve seen “Inside Job” then you’ll know all about how professors at various universities use their credentials to back up questionable practices. Moreover, they are often not even required to expose their industry connections when they do expert witnessing or write “academic” papers. The action here would be, at the very least, to force full disclosure for all such appearances and all publications. I’ve heard some good news in this direction but there obviously should be a standard.

- Rampant buying of politicians and influence of lobbyists from the financial industry. This is maybe more of a political problem than a financial one so I’m willing to chuck this off the list. Please tell me if you have something else in mind. Someone has suggested the opaque and elevated pension fund management system. Although I consider that pretty corrupt, I’m not sure it’s as important as other issues to the average person. I’m on the fence.

Saturday afternoon quickie

Two things.

- If I see another fucking article about how the world is going to miss Steve Jobs I’m going to puke. He made and sold overpriced gadgets for fucks sake! It’s hero worship plain and simple, maybe even a sick cult.

- I am happy that I’ve been invited to give a “teach-in” at Occupy Wall Street next Wednesday at 5:30 (tentative date and time). I’ve promised an overview of the 5 top corrupt things in the financial system. I’d really appreciate your thoughts: what is your top 5 list? I want them to be both important and relatively actionable. So far I’ve got:

- Volcker rule (i.e. reinstating something like Glass-Steagall); it’s being watered down as you read this.

- Ratings agencies in collusion with their clients

- SEC and other regulators in collusion with the industry

- Rampant buying of politicians and influence of lobbyists from the financial industry

- Incredibly poor incentives for the individuals in the industry, both in terms of salary and whistleblowing

Financial Terms Dictionary

I’ve got a bunch of things to mention today. First, I’ll be at M.I.T. in less than two weeks to give a talk to women in math about working in business. Feel free to come if you are around and interested!

Next, last night I signed up for this free online machine learning course being offered out of Stanford. I love this idea and I really think it’s going to catch on. There are groups here in New York that are getting together to talk about the class and do homework. Very cool!

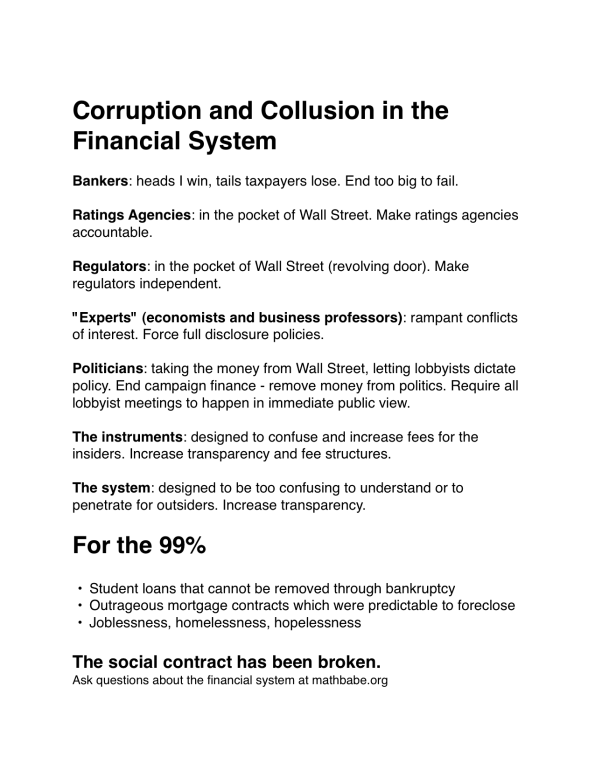

Next, I’m going back to the protests after work. The media coverage has gotten better and Matt Stoller really wrote a great piece and called on people to stop criticizing and start helping, which is always my motto. For my part, I’m planning to set up some kind of Finance Q&A booth at the demonstration with some other friends of mine in finance. It’s going to be hard since I don’t have lots of time but we’ll try it and see. One of my artistic friends came up with this:

Finally, one last idea. I wanted to find a funny way to help people understand financial and economic stuff, so I thought of starting a “Financial Terms Dictionary”, which would start with an obscure phrase that economists and bankers use and translate it into plain English. For example, under “injection of liquidity” you might see “the act of printing money and giving it to the banks”.

Finally, one last idea. I wanted to find a funny way to help people understand financial and economic stuff, so I thought of starting a “Financial Terms Dictionary”, which would start with an obscure phrase that economists and bankers use and translate it into plain English. For example, under “injection of liquidity” you might see “the act of printing money and giving it to the banks”.

I’d love comments and suggestions for the Financial Terms Dictionary! I’ll start a separate page for it if it catches on.