Archive

Alternative Banking in FT Alphaville (#OWS)

Alt Banking’s opinion piece about too-big-to-fail was published yesterday in FT Alphaville.

Woohoo!

“Where to start?”, I wondered.

Please consider purchasing a 55 gallon tub of lube from Amazon.com (pictured below). And before deciding, I suggest you read the reviews (hat tip Richard Smith via Yves Smith).

Also, please be sure to take this quiz to differentiate (if you can) between Newt Gingrich and a comic book supervillian.

How’s it going with the Volcker Rule?

Glad you asked.

Recall that Occupy the SEC is currently drafting a letter of public comment of the Volcker Rule for the SEC (for background on the Volcker Rule itself, see my previous post). I was invited to join them on a call with the SEC last week and I will talk further about that below, but first I want to give you more recent news.

Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism wrote this post a couple of days ago talking about a House Financial Services Committee meeting, which happened Wednesday. Specifically, the House Financial Services Committee was considering a study done by Oliver Wyman which warned of reduced liquidity if the Volcker Rule goes into effect. Just to be clear, Oliver Wyman was paid by a collection of financial institutions (SIFMA) who would suffer under the Volcker Rule to study whether the Volcker Rule is a good idea. In her post, Yves was discussed the meeting as well as Occupy the SEC’s letter to that Committee which refuted the findings of Oliver Wyman’s study.

Simon Johnson, who was somehow on the panel even though it was more or less stuffed with people who wouldn’t argue, had some things to say about how much it makes sense to listen to people who are paid to write studies in his New York Times column published yesterday. He also made lots of good arguments against the content of the study, namely about the assumptions going into it and how reasonable they are. From Simon’s article:

Specifically, the study assumes that every dollar disallowed in pure proprietary trading by banks will necessarily disappear from the market. But if money can still be made (without subsidies), the same trading should continue in another form. For example, the bank could spin off the trading activity and associated capital at a fair market price.

Alternatively, the relevant trader – with valuable skills and experience – could raise outside capital and continue doing an equivalent version of his or her job. These traders would, of course, bear more of their own downside risks.

If it turns out that the previous form or extent of trading existed only because of the implicit government subsidies, then we should not mourn its end.

The Oliver Wyman study further assumes that the sensitivity of bond spreads to liquidity will be as it was in the depth of the financial crisis, 2007-9. This is ironic, given that the financial crisis severely disrupted liquidity and credit availability more generally – in fact this is a major implication of the Dick-Nelson, Feldhutter and Lando paper.

If Oliver Wyman had used instead the pre-crisis period estimates from the authors, covering the period 2004-7, even giving their own methods the implied effects would be one-fifth to one-twentieth of the size (this adjustment is based on my discussions with Professor Feldhutter).

CSPAN taped the meeting, which was pretty long, but I’d suggest you watch minutes 50 through 57, where Congressman Keith Ellison took some of the panel to task for being, or acting, super dumb.

For whatever reason, Occupy the SEC wasn’t invited to the panel. You can read their letter that argues against Wyman’s study, which is on Yves’s post, or you can read this comment that one of the members of Occupy the SEC posted on Johnson’s NYTimes piece (“OW” refers to Oliver Wyman, the author of the paid study):

Your testimony at the hearings yesterday was a refreshing counterpoint to the other members of the panel.

On top of the flaws in the OW analysis you covered in the article, there was another misleading point that the OW report purported to prove.

The study focused on liquidity for corporate bonds, which SIFMA/OW characterized as ‘financing american businesses’ . But a quick review of the outstanding corporate bonds in the study reveals that the lions share of corporate bonds are CMOs and ABS. Additionally, the study reports that the majority of the holdings of corporate bonds are in the hands of the finance industry.

As a result the loss of liquidity anticipated by the SIFMA folks will mostly impact them, not the pensioners and soldiers (and their Congressmen) the bankers were trying to scare with the OW loss estimates.

If the banks are forced to withdraw as market makers for this debt, replacement market makers won’t enter until these bonds trade at much lower levels. These losses are currently stranded (and disguised) in the banking system, and by extension are inflating the value of the funds invested in these bonds.

It’s critical that the market making rules are clarified to ensure that liquidity provision for these instruments is driven out of the protected banks and into a transparent market where the mispricing will be corrected and the losses will be properly recognized.

So just to summarize, the Congressional committee listened to the results of a paid study talking about how bad the Volcker Rule would be for the market, when in fact it would be good for the market to be uninsured and realistic.

I’m not a huge fan of the Volcker Rule as it is written, but these are really terrible reasons to argue against it. To my mind, the real problem is that, as written, the Volcker Rule is too easy to game and has too many exceptions written into it.

Going back to the call with the SEC (and with Occupy the SEC). I haven’t kept abreast of the details of the Volcker Rule like these guys (they are super relentless), but I did have some questions about the risk part. Namely, were they going to end up referring to an already existing risk regulatory scheme like Basel or Basel II, or were they creating something separate altogether? They were creating something separate. They mentioned that they weren’t interested in risk per se but only to the extent that wildly fluctuating risk numbers expose proprietary trading, which is the big no-no under the Volcker Rule.

But here’s the thing, I explained, the risk numbers you are asking for are so vague that it’s super easy, if I’m a bank, to game this to make my risk numbers look calm. You don’t specify the lookback period, you don’t specify the kind of Value-at-Risk, and you don’t compare my risk model worked out on a benchmark portfolio so you really don’t know what it’s saying. Their response was: oh, yeah, um, if you could give us better wording for that section that would be great.

So to re-summarize, we have “experts”, being paid by the banks, who explain to Congress why we shouldn’t let the Volcker Rule go through, and in the meantime we’ve assigned the SEC the job of writing that rule even though they don’t know how to game a risk model (there’s a good example here of JP Morgan doing just that last week).

One last issue: when we asked about why repos had been exempted sometime in between the writing of the statute and the design of the implementation, the SEC people just told us we’d “have to ask the Fed that”.

Sunday Links

What do an upscale nightclub for Wall Streeters and the People’s Library from #Occupy Wall Street have in common? Turns out, nothing.

Someone thinks we can cure accounting shenanigans by rotating accounting firms. I’m not convinced.

I like this story from Matt Taibbi about one of the biggest assholes in the world.

For whatever reason I can’t get enough of this picture from a recent car show:

Who the hell is buying European debt?

I’m a bit confused about the “successful” European sovereign debt auctions we’ve been hearing about lately.

If I’m a European bank, say in Italy, Spain, or Portugal, or maybe even France, then about 10 months ago or so I’d be buying all the sovereign debt of my own country that I can get or that my country wants me to, because I’d figure, hey we’re in the same boat- if my country defaults then we’re going down, probably exorcised from the Euro zone.

But nowadays, because of Greece’s example, it seems increasingly likely that a country could default on its bonds, and if orderly (and “voluntary”), the country gets to stay in the Euro zone and the banks get to live on- if they can.

So if I’m a European bank now in a peripheral country, I’m going to try to stay solvent in the case of my country’s default. And I don’t even need to be completely solvent, I just need to be more solvent than most of the other banks in my country, because, especially if the Euro zone does stay intact, they probably won’t allow all the banks to fail, but they might easily let the weakest banks fail.

Wouldn’t that reasoning mean I’d avoid buying my country’s crappy debt? So why is crappy debt bought at all anymore? I realize that the yields are high, but I don’t think they’re high enough, and I just don’t get it. Maybe I’m being dumb. Here are the possibilities as I see them:

- I’m exaggerating the problem altogether, and the debt is actually fairly priced and not so risky. In answer to this let me quote Princeton economist Alan Blinder, a former U.S. Federal Reserve vice chairman, in this Wall Street Journal article about what to worry about in 2012: “Europe is absolutely my No. 1 concern. It is so far in the lead I can’t think of what my No. 2 concern is.”

- The governments are putting backroom pressure on the banks to buy their debt. This seems quite probable. I definitely get the impression that there’s real politics behind the accumulation of Greek debt in French banks, for example, because otherwise the enormous holdings in BNP Paribas and others is frankly impenetrable, and certainly not in the interest of the bank itself.

- There is some short or medium term gaming of the system going on right now, using the ECB’s recent action to restore “liquidity” in order to look better. Specifically, we have this quote from Bill Gross of PIMCO: “Amazingly, Italian banks are now issuing state guaranteed paper to obtain funds from the European Central Bank (ECB) and then reinvesting the proceeds into Italian bonds, which is QE by any definition and near Ponzi by another.”

- Actually, the next time peripheral countries issue debt nobody will show up to buy it.

I’d love to hear comments from people who have different theories.

It takes imagination to be boring

I suffer from a lack of imagination.

I have been so inculcated in the necessary complexity of finance and banking, that I’ve lost touch with some basic, simple realities. I have been brainwashed by the half-assed and lame attempts at regulation by the elements of the Dodd-Frank bill, losing myself in the details of the Volcker Rule for example, and I’ve lost the forest for the trees. I’m spending my time furiously figuring out how to allow banks to have all of their goodies (CDS, derivatives, repos, etc.), but not let them eat so much they get themselves (and us) sick.

Sometimes you need imagination to be boring.

Luckily, there was an op-ed article in the New York Times yesterday which served as a wake-up call. The article is called “Bring Back Boring Banks” and it’s written by Amar Bhide. I kind of feel like quoting the entire article, since it’s all so good, but I’ll make do with this part (emphasis mine):

Guaranteeing all bank accounts would pave the way for reinstating interest-rate caps, ending the competition for fickle yield-chasers that helps set off credit booms and busts. (Banks vie with one another to attract wholesale depositors by paying higher rates, and are then impelled to take greater risks to be able to pay the higher rates.) Stringent limits on the activities of banks would be even more crucial. If people thought that losses were likely to be unbearable, guarantees would be useless.

Banks must therefore be restricted to those activities, like making traditional loans and simple hedging operations, that a regulator of average education and intelligence can monitor. If the average examiner can’t understand it, it shouldn’t be allowed. Giant banks that are mega-receptacles for hot deposits would have to cease opaque activities that regulators cannot realistically examine and that top executives cannot control. Tighter regulation would drastically reduce the assets in money-market mutual funds and even put many out of business. Other, more mysterious denizens of the shadow banking world, from tender option bonds to asset-backed commercial paper, would also shrivel.

This is what we need to do. Thank you Amar Bhide, for having the clarity to say it.

Politics of teacher pay disguised as data science

I am super riled up about this report coming out of the Heritage Foundation. It’s part of a general trend of disguising a political agenda as data science. For some reason, this seems especially true in education.

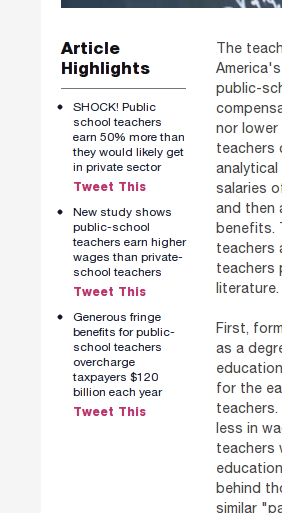

The report claims to prove that public school teachers are overpaid. As proof of its true political goals, let me highlight a screen shot of the “summary” page (which has no technical details of the methods in the paper):

I’m sorry, but are you pre-writing my tweets for me now? Are you seriously suggesting that you have investigated the issue of public school teacher pay in an unbiased and professional manner with those pre-written tweets, Heritage Foundation?

If you read the report, which I haven’t had time to really do yet, you will notice how few equations there are, and how many words. I’m not saying that you need equations to explain math, but it sure helps when your goal is to be precise.

And I’d also like to say, shame on you, New York Times, for your coverage of this. You allow the voices of the authors, from the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, as well as another political voice from the Reason Foundation. But you didn’t ask a data scientist to look at the underlying method.

The truth is, you can make the numbers say whatever you want, and good data scientists (or quants, or statisticians) know this. The stuff they write in their report is almost certainly not the whole story, and it’s obviously politically motivated. I’d love to be hired to research their research and see what kind of similar results they’ve left out of the final paper.

#Occupy Wall Street course at Columbia University

Columbia University’s Anthropology department is offering a course on #Occupy Wall Street. You can see clever announcements in this Gothamist article and this Bwog post.

I’ve already contacted the instructor, Hannah Appel, and invited her students to join the Alternative Banking Working Group on Sunday afternoons. She seems very psyched to join us and have her students join us. Here’s the syllabus for her course.

Please spread the word about our working group. We are working on lots of different projects around reforming the current financial system. You don’t need to be an expert in finance to come.

The sin of debt (part 3)

I wrote here about the way normal people who are in debt are imbued with the stigma of immorality, whereas corporations are applauded for debt (and even for declaring bankruptcy). I admit that my second post, which contained outrageous examples of the ideas in the first post, was rather frustrated, because I had little in the way of solutions. I like to propose solutions rather than just point out problems.

First, I’ve got some good news. Namely, as described in this Wall Street Journal article, a judge has ruled that the debt collection agency harassing an elderly woman for her dead husband’s debt was indeed harassment. From the article:

The case could set a precedent across the U.S. and discourage lenders from using collectors to get money from surviving relatives on debts left behind by the deceased, according to other state-court judges.

That’s something!

Next, I’ve been discussing the language of debt with various people and we’ve come up with a plan. This language issue was the main point of my first post: the words we use make individuals feel dirty when they are indebted, but sanitizes the concept of debt for corporations (“restructuring”).

Let’s turn this around. Let’s come up with our own vocabulary to separate the issues and also to point out what brings people into debt in the first place. We’ve come up with three proposed vocabulary terms to add to the discourse:

- Poisonous debt: this is debt that comes from actually fraudulent lenders, or who lent to vulnerable people under false pretenses. Actually existing laws should be taking care of these things, but the problem is of course that people who are in massive amounts of debt typically don’t have good lawyers.

- Debt under duress: this term should refer to debt that people incur in emergency situations, like medical emergencies, divorces, or funerals. Elizabeth Warren has done a lot of work describing how many families in serious money trouble got there with exactly this kind of situational debt.

- School system debt: the school system in this country is inconsistent, which causes enormous competition for families to buy a house in a good school district, often buying houses they can’t quite afford for the sake of their childrens’ educations. This is well-documented and, for any individual, totally understandable.

What I like about the above terms is that they separate the people who take on the debt from the reasons they take on the debt. Anyone can relate to the above reasons, and when that happens, a sympathy, rather than a moral judgement, emerges. If I hear someone has taken on debt under duress, I immediately want to know if they’re ok.

They also provide a much-needed balance to the typical argument you hear against people who bristle at the idea of debt amnesty, namely the concept of free-loaders milking the system for cheap cash to spend on unnecessary trinkets and then not paying it back.

If you understand the extent to which people are in debt because of health issues, your response may be something more like, hey we should really make the health care system in this country more reasonable. In other words, it starts a much more interesting and potentially useful conversation than mere finger wagging.

Need your vote

Footnoted needs your vote on the most outrageous handout to executives in 2011. Here are the candidates:

- MF Global agreeing to pay then-CEO Jon Corzine a $1.5 million retention bonus months before the company imploded.

- Clear Channel Media Holdings paying $3 million a year to a company controlled by Bob Pittman so that Pittman can fly in a Mystere Falcon 900 that Pittman owns for both business and personal use.

- Leo Apotheker collecting around $25 million in severance and other benefits from Hewlett-Packard, including relocation back to France or Belgium after less than a year on the job.

- IBM’s outgoing CEO Samuel Palmisano becoming eligible for as much as $170 million in retirement benefits, just by waiting until he was past 60 to announce his retirement.

- Nabors Industries agreeing to pay outgoing CEO Eugene Isenberg $100 million in severance on his way out the door.

Vote here.

Also, please read a letter to Jamie Dimon that I enjoyed, from the Reformed Broker blog. From the letter:

So please, do us all a favor and come to the realization that the loathing you feel from your fellow Americans has nothing to do with your “success” or your “wealth” and it has everything to do with the fact that your wealth and success have come at a cost to the rest of us. No one wants your money or opportunities, what they want is the same chance that their parents had to attain these things for themselves. You are viewed, and rightfully so, as part of the machine that has removed this chance for many – and that is what they hate.

Why work?

In his recent Vanity Fair article, Joseph Stiglitz puts forth the following theory about why the Great Depression was inevitable (and in particular wouldn’t have been prevented by the Fed loosening monetary policy). Namely, that our society was transitioning from an agrarian society to something else- which turned out to be a manufacturing society, kicked off in earnest at the beginning of World War II. He goes on to say that we are now going through another great transition, from manufacturing to something else- he calls it service. And he also says there’s no way monetary policy will fix this trauma either- we need to invest heavily in infrastructure in order to prepare ourselves for the coming service society we will be.

Take a few steps back, and we see this picture: a hundred years ago we got so efficient at farming that we didn’t need everyone to farm to be well fed. Then we figured out how to make things so efficiently that we don’t need to worry about having enough stuff. So now, what are we all working for exactly? If service means we take care of each other (medical stuff) and we educate each other, that is fine, but not everyone is a doctor or a teacher. If service means we spend all our time making video games and entertaining each other, than it seems like we need to rethink this plan.

There are two essays I’ve read about the nature of this change that I think will help us rethink work and how our society values work and how it doles it out. First, there’s this highbrow essay on the language of work. From the essay:

Work deploys a network of techniques and effects that make it seem inevitable and, where possible, pleasurable. Central among these effects is the diffusion of responsibility for the baseline need to work: everyone accepts, because everyone knows, that everyone must have a job. Bosses as much as subordinates are slaves to the larger servomechanisms of work. In effect, work is the largest self-regulation system the universe has so far manufactured, subjecting each of us to a panopticon under which we dare not do anything but work, or at least seem to be working, lest we fall prey to a disapproval all the more powerful for its obscurity. The work idea functions in the same manner as a visible surveillance camera, which need not even be hooked up to anything. No, let’s go further: there need not even be a camera. Like the prisoners in the perfected version of Bentham’s utilitarian jail, workers need no overseer because they watch themselves. When we submit to work, we are guard and guarded at once.

What is less clear is why we put up with this demand-structure of a workplace, why we don’t resist more robustly. As Max Weber noted in his analysis of leadership under capitalism, any ideology must, if it is to succeed, give people reasons to act. It must offer a narrative of identity to those caught within its ambit, otherwise they will not continue to perform, and renew, its reality. As with most truly successful ideologies, the work idea latches on to a very basic feature of human existence: our character as social animals forever competing for relative advantage.

The author Mark Kingwell makes a pretty convincing case that people have bought into work just as they buy into other cultural norms. It underlines the real audacity of the #Occupy Wall Streeters who dared to do something with their time than be baristas at Starbucks.

Paired with the Stiglitz view of our culture and its future, though, it makes me think about the extent to which we’ve synthesized work. Mark Kingwell points out that one of the major outputs of workplaces is more work, a kind of purely synthetic made-up idea which we all need to believe in as long as we are all convinced about this work-as-cultural imperative.

The quintessential example of work-creating-work comes from finance, of course, where there isn’t even really a product at the end of the day. It’s essentially all completely made up, pushing around numbers on a spreadsheet.

What happens when people question this industry and its associated maniacal belief in work as moral? I say “maniacal” based on the number of hours people put in at most financial firms, sacrificing their families and even their internal lives, not to mention their associated martyred attitudes at having worked so hard.

This article from Bloomberg addresses the issue indirectly. In it, Richard Sennett talks about what bonds people to their colleagues and their workplace. He compares manufacturing jobs in 1970’s Boston to the recent financial services industry, and notes that people nowadays in finance have no loyalty to each other or to their workplace, and also have very little respect for the bosses. He blames this on unthoughtful hierarchical structures and the fact that bosses are essentially incompetent and everybody knows it. He concludes his article as follows:

These employees were relentless judges of their bosses, always on the lookout for details of conversation or behavior to suggest that the executives didn’t deserve their powers and perks. Such vigilance naturally weakened the bosses’ earned authority. And it didn’t make the people judging feel good about themselves either, as they were stuck in the relationship. On the contrary, it was more likely to be embittering than a cause for secret satisfaction.

Even for those workers who have recovered quickly, the crash isn’t something they are likely to forget. The front office may want to get back as quickly as possible to the old regime, to business as usual, but lower down the institutional ladder, people seem to feel that during the long boom something was missing in their lives: the connections and bonds forged at work.

Although those are fine reasons to dismiss loyalty, as I know from experience, I’d like to suggest another reason we are seeing so much disloyalty, namely that people see through the meaningless of their job, and are wondering why the system has even been set up this way in the first place.

In other words, I don’t think a better hierarchy and super smart bosses in finance is going to make back office people gung-ho. I think that the credit crisis has clearly exposed what people already suspected, namely that they are working hard but not accomplishing much. If we want people to feel fulfilled, wouldn’t it make more sense to work less, and spend more time off with their families and their thoughts? Could we as a society imagine something like that?

How to challenge the SEC

This is a guest post by Aaron Abrams and Zeph Landau.

No, not the Securities and Exchange Commission. We are talking about the Southeastern Conference, a collection of 12 (or so) college football teams.

College football is a mess. Depending on your point of view, you can take it to task for many reasons: universities exploiting student athletes, student athletes not getting an education, student athletes getting special treatment, money corrupting everybody’s morals . . .

Putting those issues aside, however, there is virtually unanimous discontent with an aspect of the sport that is very quantitative, namely, how the season ends. Fans hate it, coaches hate it, players hate it, and there is a substantial controversy almost every single year. Only a few people who make lots of money off the current system seem to like it. (Never mind that anyone with a brain thinks there should be a playoff … perhaps that’s the subject of another post.)

Here’s how it works. There are roughly 120 major college football teams and each team plays 12 or 13 games in the fall. Almost all the teams belong to one of eleven conferences — these are like regional leagues — and most of the games they play are against other teams in their conference. (How they schedule their out-of-conference games is an interesting issue that we may write about another day.) At the end of the season, teams are invited to play in bowl games: games hosted at big stadiums with names like the Rose Bowl, the Orange Bowl, etc., that have long traditions. The problem centers around how teams are chosen to compete in these bowl games.

Basically, a cartel comprised of six of the eleven conferences (those that historically have been the strongest, including the SEC) created a system, called the BCS, that favors their own teams to get into the 5 most prestigious (and lucrative) bowl games, including the so called “national championship game” that claims to feature the top two teams in the country. The prestige gained by the 10 teams that compete in these games is matched by large amounts of money, coming mainly from television contracts and ticket sales. For each of these teams, we are talking about 10-20 million dollars that goes to a combination of the team and their conference. This is not a paltry sum for schools facing major budget cuts.

The most blatant problem with this system is that is it literally unfair: the rules of the system are written in such a way that at the beginning of the season, before any games are played and regardless of how good the teams are, the teams from the six “BCS conferences” have a better chance of getting into one of the major bowls than a team from a non-BCS conference. (You can read the rules, but notably, each of the conference champions of the six BCS conferences automatically gets to play in a BCS bowl game; whereas the other conference champions only get to play in a BCS bowl game if various other conditions are met, like they’re highly ranked in the polls).

There are lots of other problems, too, but we’re not really going to talk about those. For instance the method for choosing the top two teams (which is based on both human and computer polls) is deeply and fundamentally flawed. These are the teams that play for the “BCS championship”, so it matters who the top two are. But again, that’s the subject of a different post.

Back to the inherent unfairness. Colleges in the non-BCS conferences are well aware of this situation. Led by Tulane, they filed a lawsuit several years ago and essentially won; the rules used to be even worse before that. But in the face of the continued lack of fairness, colleges from non-BCS conferences have lately taken to responding by trying to get into the BCS conferences, jockeying for opportunity at big money. It has gotten so bad that a BCS conference called the Big East now includes teams from Idaho and California. Realignment has caused the Big 12 to have only 10 teams, while the Big 10 has 12.

But realignment takes a lot of work to pull off, and it only benefits the teams that get into the major conferences. The minor conferences themselves are still left behind. So here is a better idea. If you’re a non-BCS conference, do what any good red-blooded american corporation would do: find a loophole.

Here is one we thought of.

The current rules force the BCS to choose a team from one of the 5 non-BCS conferences if:

(a) a team has won its conference AND is ranked in the top 12, or

(b) a team has won its conference AND is ranked in the top 16 AND is ranked higher than the conference champion from one of the BCS conferences.

What they don’t say is what it means for a team to “win its conference.” Some conferences determine their champion by overall record, and others have a championship game to decide the champion. This is the chink in the armor.

This year two interesting things happened: (1) in the Western Athletic Conference (WAC), Boise State ended up ranked #7, but did not win their conference. The WAC doesn’t have its own championship game, and the conference winner was TCU by virtue of beating Boise State in a game in the middle of the season. However, TCU also lost a game to a team outside their conference, and they ended up ranked only #18. As a result, neither team satisfied condition (a) or (b) above.

And (2) in Conference USA, Houston was undefeated and ranked #6 in the country before the final game of the season, when it lost its conference championship game to USM. The loss dropped Houston to #19 in the rankings, whereas USM, the conference champion, finished with a final ranking of #21. Thus neither of these teams met (a) or (b), either.

Here is what we noticed: if the Western Athletic Conference had a conference championship game, then either Boise St would have won it, been declared the champion, and qualified for a BCS bowl, or else TCU would have won it and would almost surely have ended up with a high enough rank to qualify for a BCS bowl. (As it was, TCU finished the season at #18, but one more victory against a top ten team would very likely have gained them at least two spots. This would have been good enough for (b) to apply, since the champion of the Big East (a BCS conference) was West Virginia, who finished ranked #23.)

On the other hand, if Conference USA hadn’t had a championship game, Houston would have been declared the conference champion (by virtue of being undefeated before the championship game) and they would easily have been ranked highly enough to get into a BCS bowl. Indeed, it has been estimated that their loss to USM cost Conference USA $17 million.

So, what should these non-BCS conferences do? Hold a conference championship game . . . if, and only if, it benefits them. They can decide this during the last week of the season. This year, with nothing to lose and plenty to gain, the WAC would clearly have chosen to have a championship game. With nothing to gain and plenty to lose, Conference USA would have chosen not to.

Bingo. Loophole. 17 million big ones. Cha ching.

Bloomberg engineering competition goes to Cornell

This just in. Pretty surprising considering we were supposed to hear the results January 15th. I wrote about this here and here.

I wonder what Columbia is going to do with their plans?? I guess there may be two winners, so still exciting.

A rising tide lifts which boats?

My friend Jordan Ellenberg has a really excellent blog post over at Quomodocumque, which is one of my favorite blogs in that it combines hard-core math nerdiness with funny observations about how much the Baltimore Orioles stink (among other things).

In his post he talks about an anti-#OWS article called “The Occupy movement has it all wrong”, by Larry Kaufman, recently published in a Madison, WI newspaper called Isthmus.

Specifically, in that article, Kaufman tries to use the old saying “a rising tide lifts all boats” to argue that most people (in fact, 81% of them) are better off than their parents were. What’s awesome about Jordan is that he goes to the source, a Scott Winship article, and susses out the extent to which that figure is true. Turns out it’s kind of true with a certain way of weighting numbers depending on how many kids there are in the family and because so many women have started working in the past 40 years. Jordan’s conclusion:

So yes: almost all present adults have more money than their parents did. And how did they accomplish this? By having one or two kids instead of three or four, and by sending both parents to work outside the home. Now it can’t be denied that a society in which most familes have two income-earning parents, and the business-hours care of young children is outsourced to daycare and preschool, is more productive from the economic point of view. And I, who grew up with a single sibling and two working parents and went to plenty of preschool, find it downright wholesome. But it is not the kind of development political conservatives typically celebrate.

Another thing that Jordan tears apart from the article is that the original source specifically pointed out stuff that Kaufman seems to have missed, given his political agenda:

Winship also emphasizes the finding that children in Canada and Western Europe have an easier time moving out of poverty than Americans do. This part is absent from Kaufmann’s piece. Maybe he didn’t have the space. Maybe it’s because a comparison with higher-tax economies would make some trouble for his confident conclusion: “the punitive redistribution policies favored by Occupy Madison will divert capital away from productive initiatives that enhance growth and earnings opportunities for all, while doing nothing to build the stable families and “bottom-up” capabilities that are particularly important for helping the poorest Americans escape poverty.”

When the Isthmus is running a more doctrinaire GOP line on poverty than the National Review, the alternative press has arrived at a very strange place indeed.

Go, Jordan!

Let’s go back to that phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats”. It was the basis of Kaufman’s argument, and as Jordan points out was a pretty weak basis, in that the lift was arguable gotten only through sacrifice. But my question is, is that a valid argument to make anyway?

Let’s examine this metaphor a bit. When we think about it positively, and imagine something like the housing bubble which elevated many people’s net worth (ignoring the people who weren’t home owners at all during that time), we can see why “a rising tide lifts all boats” is a good thing: we want the generic imaginary person to do well, and we’re all happy for them to do well.

However, if we turn that phrase around in a negative moment, it’s really not clearly a good perspective. Let’s try it: “an ebbing tide lowers all boats”. Take the example of a housing crash analogously to the above. Firstly it’s not true, since for those people who couldn’t afford housing in the bubble, a more reasonable housing market is a good thing (for some reason people keep forgetting this). Secondly, when we are thinking about lowered boats we worry about those people whose boats are lowered. Who are those people? How much have they lost? Will they be okay?

The answers are, they are the people who were barely able to own the house in the good times. They’ve lost everything. They aren’t okay.

It’s a nearly vapid phrase when you think about it, but it’s used by conservatives a lot to justify policies that only work well in good times.

I’d argue that the real question we should be asking isn’t whether we are all sailing away in boats but how much risk we take on as individuals. I will go into this further in another post, but the gist is that, instead of the unit of measurement being assumed to be dollars, I’d like to reframe the concept of economic health in terms of a unit of risk. Risk is harder to measure than dollars, and there are lots of different kinds of risk, but even so it’s a worthy exercise.

For example, in the housing boom we had people who could barely afford a house get into ridiculous mortgage contracts, with resetting usurious interest rates. They were taking on enormous amounts of risk, in this case risk of being foreclosed on and losing their home. By contrast, people who were well-off at the start of the housing boom are for the most part still well off. There was very little risk for them.

I’d like to offer up an alternative phrase which would capture the risk perspective. Something like, “we should make sure everyone’s boats are water tight and firmly moored to the pier”. Not nearly as catchy, I know. But to make for it I’m linking to this related video called I’m On a Boat. I’ve actually been looking for excuses to link to this for a while. Here’s a kind of awesome picture from the video:

What up, New York Times? (#OWS)

There have been people complaining about the #OWS coverage by the New York Times, saying that it’s dismissive and slanted, generally not reporting enough and, when it does report, looking at things from the perspective of the Bloomberg administration.

I have tried to reserve judgment, although I did notice that the day of the 2-month anniversary of the occupation (a few days after Bloomberg cleared the park), where there were lots of actions and the big march, the NYT didn’t seem to cover anything in the morning at all, whereas the WSJ had live coverage of the hundreds of people trying to close down the exchange and disrupt the morning bell.

And I’m not sure if it’s the reporters or the editors who are responsible for the slanted coverage. It’s sometimes hard to tell.

Except sometimes. Here’s an article about Occupy Frankfurt from two days ago, in which a peaceful protest with a supportive police force is described:

“If all demonstrations went so well we wouldn’t have much to do,” said Michael Jenisch, a spokesman for the Frankfurt Ordnungsamt, or Office of Public Order, which issues permits for public gatherings and has been monitoring the Occupy Frankfurt encampment.

“If they have the staying power, they can camp there all winter,” Mr. Jenisch said. That attitude contrasts with that of the authorities in cities like New York, Oakland or Boston, where the police have evicted protesters from public space, and also with other financial centers in Europe.

That’s all fine, but here’s where I find the coverage outrageous. The article was not on the virtual front page; instead there was a link to the article from the front page, and the teaser line was:

Unlike at other Occupy sites, the Frankfurt protesters are being careful to make their points without inciting police interference.

What? Seriously??

I can’t tell you how often I was down at Zucotti, wondering why there were so many cops there, wasting our tax payer money, when the protesters were so incredibly peaceful. Who incited police interference? Was it the sleeping protesters in tents?

The message is not for protesters, on how to incite police aggression. The message here is for American cops, on how to deal with peaceful protesters. New York Times editors, did you even read your own article?

Where is Volcker’s letter? (#OWS)

At the Alternative Banking working group we are working on publicly commenting on the proposed Volcker Rule. Check out this blog post which addresses the exemption for repos. Keeping in mind that repos brought down MF Global a few weeks ago, this is a hot topic.

Here’s another hot topic, at least to me. Who has a copy of Volcker’s original 3-page letter? The published rumor has it that he wrote a 3-page letter to Obama outlining the goal of the regulation, but I can’t find it anywhere. I do have this quote from Volcker about the proposed 550 page behemoth (taken from a New York Times article):

“I’d write a much simpler bill. I’d love to see a four-page bill that bans proprietary trading and makes the board and chief executive responsible for compliance. And I’d have strong regulators. If the banks didn’t comply with the spirit of the bill, they’d go after them.” – Volcker

Also from the New York Times, a column of Simon Johnson’s on the Volcker rule and what it’s missing.

If anyone knows how to get their hands on the original letter, please tell me, I’d really love to see it. Maybe someone knows Volcker and can just ask him for a copy?

Thank you, Inside Job

The documentary Inside Job put a spotlight on conflict of interest for “experts,” specifically business school and economic professors at well-known universities. The conflict was that they’d be consulting for some firm or government, getting paid tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, and would then write academic papers investigating the methods of that firm or government, without disclosing the payments.

Since it’s human nature to do so, these academic papers would end up supporting those methods, more often than not, even when the methods weren’t sound. I’m being intentionally generous, because the alternative is to think that they actually sell their endorsements; I’m sure that happens, but I’m guessing it isn’t always a conscious, deliberate decision.

Last Spring, the Columbia Business School changed its conflict of interest policy to address this exact problem. From the Columbia Spectator Article:

Under the new policy, Business School professors will be required to publicly disclose all outside activities—including consulting—that create or appear to create conflicts of interest.

“If there is even a potential for a conflict of interest, it should be disclosed,” Business School professor Michael Johannes said in an email. “To me, that is what the policy prescribes. That part is easy.”

The policy passed with “overwhelming” faculty support at a Tuesday faculty meeting, according to Business School Vice Dean Christopher Mayer, who chaired the committee that crafted the policy.

The new policy mandates that faculty members publish up-to-date curricula vitae, including a section on outside activities, on their Columbia webpages. In this section, they will be required to list outside organizations to which they have provided paid or unpaid services during the past five years, and which they think creates the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Good for them!

Next up: the Harvard Business School. I don’t think they yet have a comparable policy. When you google for “Harvard Business School conflict of interest” you get lots of links to HBS papers written about conflict of interest, for other people. Interesting.

I don’t understand what the reasoning could be that they are stalling. Is there some reason Harvard Business School professors wouldn’t want to disclose their outside consulting gigs? I mean, we already know about them advising Gaddafi back in 2006, so that can’t be it. Just in case you missed that, here’s an excerpt from the Harvard Crimson article from last Spring:

But Harvard professors have focused on the political conclusions of the report, which, among a set of recommendations, indicated that Libya was a functioning democracy and heralded the country’s system of local political gatherings as “a meaningful forum for Libyan citizens to participate directly in law-making.”

The report was a product of Monitor’s work consulting for Gaddafi from 2006 to 2008. The Libyan government—headed by Gaddafi, who has ruled since a 1969 military coup—hired consultants from Monitor Group to provide policy recommendations, economic advice, and several other services.

The consulting group carries a distinct Harvard flavor. On its website, the company touts the Harvard ties of several of its founders and current leaders.

I’m wondering if this would have happened if there already was a conflict of interest policy, like Columbia’s, in place. And I’m focusing on Harvard because if both Harvard and Columbia set such policies, I think other places will follow. As far as I can see, this is just as important as conflict of interest policies for doctors with respect to drug companies.

Hank Paulson

A few days ago it came out that former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson is a complete asshole. Some people knew this already, but Felix Salmon kind of nailed it permanently to the wall with this Reuters column where he describes how Paulson told his buddies all about what was going on in the credit crisis a few weeks or days before the public was informed. Just in case descriptions of his behavior aren’t clear enough, Salmon ends his column with this delicious swipe:

Paulson, says Teitelbaum, “is now a distinguished senior fellow at the University of Chicago, where he’s starting the Paulson Institute, a think tank focused on U.S.-Chinese relations”. I’d take issue with the “distinguished” bit. Unless it means “distinguished by an astonishing black hole where his ethics ought to be”.

Here’s another thing that people may want to know about Paulson, and which some people know already but should be more loudly broadcast: he dodged tens of millions of dollars in taxes by becoming the Treasure Secretary. This article from the Daily Reckoning explains the conditions:

Under the guise of not wanting to “discourage able citizens from entering public service,” Section 1043 is an alteration of the government’s conflict of interest rules. Before 1043, executive appointees (mostly high-up cabinet members and judges) had to sell positions in certain companies to combat conflict of interest – like say, a former Goldman Sachs CEO-turned Treasury Secretary with millions of GS shares. After Sec. 1043, the appointee gets a one-time rollover. Upon their appointment, he or she can transfer their shares to a blind trust, a broad market fund or into treasury bonds. They’ll have to pay taxes on the position one day, but not immediately after the sale… like the rest of us.

I’m a big believer in incentives. And from where I sit, when you piece together Hank Paulson’s incentives, you get his actions. In some sense we shouldn’t even complain that he’s such an asshole, because we invented this system to let people like him act in these asshole ways.

[It brings up another related topic, namely that the level of corruption and misaligned incentives actually drives ethical people out of finance altogether. I want to devote more time to think about this, but as partial evidence, consider how few “leaders” from the financial world have stepped up and supported Occupy Wall Street, or for that matter any real challenge to business as usual. At the same time there are plenty of people in finance who are part of the movement, but they tend to be the foot soldiers, or young, or both. Maybe I’m wrong- maybe there are plenty of senior people who just are remaining anonymous, doing their thing to undermine the status quo, and I just haven’t met them. According to this article which I linked to already for a different reason, and which corroborates my experience, there are lots of people who see the rot but not too many doing anything about it.]

Here’s what we do. We ask people who want to be public servants to sacrifice something (besides their ethics) to actually serve the public. I’m convinced that there really are people who would do this, especially if the system were set up more decently. We don’t need to offer huge cash incentives to attract people like Paulson to be Treasury Secretary.

update: I’m not the only person who thinks like this.

Various #OWS links

Here’s an internal Fed blog describing an internal Fed report which proposes that we tie banker bonuses to the CDS spread of the bank. The crux of the idea:

Under our scheme, a high or increasing CDS spread would translate into a lower cash bonus, and vice versa. For banks that do not have a liquid CDS market, the bonus could be tied to the institution’s borrowing cost as proxied by the debt spread. However, the CDS spread has the benefit of being market based, and can be chosen optimally. It is the closest analogue a bank has to a stock price—it is the market price of credit risk. If CEO deferred compensation were tied directly to the bank’s own CDS spread, bank executives would have a direct financial exposure to the bank’s underlying risk and would have an incentive to reduce risk that does not enhance the value of the enterprise.

It’s an interesting idea and I’ll think about it more. I have two concerns off the bat though. First, the blog (I didn’t read the paper) acts like CDS can be honestly taken as a proxy for likeliness to default. However in the real world everything is juiceable. So this scheme will give people more incentives to push for, among other things, fraudulent accounting to avoid looking risky. My second concern is an add-on to the first: the insiders, who benefit directly from low CDS spread, will have very direct reasons to perpetuate such accounting fraud. Somehow I’d love to see (if possible) a scheme put forth where insiders have incentives to ferret out and expose fraud.

———

A beautiful post about the metamovement of which OWS is a part, by Umair Haque. A piece:

In a sense, that sentiment is the common thread behind each and every movement in the Metamovement — a sense of grievous injustice, not merely at the rich getting richer, but at the loss of human agency and sovereignty over one’s own fate that is the deeper human price of it.

He links to We Are the 99 Percent. Check it out if you haven’t already seen it.

———

Interfluidity blogs about how yes, the bankers really were bailed out. Big time. Great points, here is my favorite part:

Cash is not king in financial markets. Risk is. The government bailed out major banks by assuming the downside risk of major banks when those risks were very large, for minimal compensation. In particular, the government 1) offered regulatory forbearance and tolerated generous valuations; 2) lent to financial institutions at or near risk-free interest rates against sketchy collateral (directly or via guarantee); 3) purchased preferred shares at modest dividend rates under TARP; 4) publicly certified the banks with stress tests and stated “no new Lehmans”. By these actions, the state assumed substantially all of the downside risk of the banking system. The market value of this risk-assumption by the government was more than the entire value of the major banks to their “private shareholders”. On commercial terms, the government paid for and ought to have owned several large banks lock, stock, and barrel. Instead, officials carefully engineered deals to avoid ownership and control.

———

Next, read this Newsweek article if you’re still wondering what Mayor Bloomberg’s personal incentives are for letting OWS complain about crony capitalism and the power of lobbyists. The scariest part:

Let’s say a lobbyist for a coal company wants to squash any legislation that affects his employer’s mining operations. He logs onto BGov.com (the cost is $5,700 per year) and is automatically alerted to breaking news of a just-introduced energy bill. The data drill-down begins. BGov shows the lobbyist how similar legislation has fared, what subcommittee the new bill will face and when, who the key congressmen are, and how they have voted in the past. The lobbyist calls up information on the swing vote’s upcoming election contest: it’s competitive, and the congressman is behind in fundraising. Lists of major donors—who might be induced to contribute or, better yet, place a call to the officeholder himself—are a click away. These political pressure points and a thousand more are how lobbyists make their mark, and Bloomberg thinks BGov can deliver them faster than the competition.

———

Finally, a very nice blog about the Alternative Banking group and David Graeber by Joe Sucher. Here’s an excerpt:

I know the usual naysayers will nay say until they are blue in the face about changing the so-called system. “It will never happen, never will, so let’s wait for things to settle down and go back to business as usual.” These folks, I’d venture to say, may be exhibiting a fundamental crisis of imagination.

I remember an elderly immigrant anarchist reminded me (when I was naysaying) that if you were to tell a 14th century European serf, that some time in the next few hundred years, they’d actually have the ability to cast a vote that mattered, no doubt you’d be met with a blank stare. The thought just wouldn’t compute.

——–

updated: Jesse Eisenger of Propublica wrote this interesting article in DealBook, where he talks about the insiders on the Street who are frustrated by the rampant corruption. I agree with a lot he says but he clearly needs to join us at an Alternative Banking group meeting:

It’s progress that these sentiments now come regularly from people who work in finance. This is an unheralded triumph of the Occupy Wall Street movement. It’s also an opportunity to reach out to make common cause with native informants.

It’s also a failure. One notable absence in this crisis and its aftermath was a great statesman from the financial industry who would publicly embrace reform that mattered. Instead, mere months after the trillions had flowed from taxpayers and the Federal Reserve, they were back defending their prerogatives and fighting any regulations or changes to their business.

Perhaps a major reason so few in this secret confederacy speak out is that they are as flummoxed about practical solutions as the rest of us. They don’t know where to begin.

Um, there are plenty of very good places to begin. It’s a question of politics, not of solutions. Start with the very basics: enforce the rules that already exist. Give the SEC some balls. We’ll go from there. Sheesh!

Zuccotti Park just now: updated

Police are keeping people out of the park.

In addition, the Atrium at 60 Wall is closed all day. They haven’t said when it will reopen.

You can register your opinion on this handy New York Times graphic.

They’re back in! Check it out live.