Archive

“Our organization does not reward failure” – Koch

You have to check out this Bloomberg article about Koch Industries. Although it rambles a bit at times, it’s absolutely mesmerizing and horrible. Here’s the main premise, which bizarrely comes near the end of the article:

For six decades around the world, Koch Industries has blazed a path to riches — in part, by making illicit payments to win contracts, trading with a terrorist state, fixing prices, neglecting safety and ignoring environmental regulations. At the same time, Charles and David Koch have promoted a form of government that interferes less with company actions.

The phrase “our organization does not reward failure” comes from a book in 2007 written by one of the Koch brothers where he somehow fails to discuss a pipeline explosion that had recently killed two teenagers in Oklahoma:

The 570-mile-long pipeline carrying liquid butane from Medford, Oklahoma, to Mont Belvieu, Texas had corroded so badly that one expert, Edward Ziegler, likened it to Swiss cheese. The company didn’t give 40 of the 45 families near the explosion site — including the Smalley and Stone families — any information about what to do in case of an emergency, the NTSB wrote.

The article is complete, in that it even has a spiteful twin brother of one of the Koch brothers appearing to give away his brothers for stealing.

The Senate held hearings in May 1989 after Bill Koch, David Koch’s twin brother, told a U.S. Senate special committee on investigations that Koch Industries was stealing oil on American Indian reservations, cheating the federal government of royalties.

The investigators caught Koch Oil’s employees falsifying records so that the company would get more crude than it paid for, shortchanging Indian families, Elroy said. Koch’s records showed that the company took 1.95 million barrels of oil it didn’t pay for from 1986 to 1988, according to data compiled by the Senate.

One thing that fascinating to me is that there are two whistle-blowers in the story, both women who were essentially fired for having ethics (one reported on bribes and the other on toxic gas dumping, both sued the company after leaving). Doesn’t it seem like women are more often whistle-blowers? Especially if you consider the fact that high ranking people in these kinds of companies with access to the kind of information that whistle-blowers need to uncover fraud are typically men.

These Koch brothers are seriously despicable, and really all they seem to care about is the ability to make money without having to worry about rules, even basic rules of morality. They currently largely bankroll the Tea Party. It’s a scary thought that I could someday live in a country whose president owes a favor to these guys.

Is the Onion actually America’s finest news source?

Have you noticed that some of the best reporting nowadays is satire? I feel like I learn most of the news I know from reading newspapers online, but I’m unusual: most people, especially young people, seem to get their news from the Daily Show and Colbert, as well as the Onion.

And it’s not just the writing, which is generally excellent and intelligent, as well as hilariously entertaining. It’s the topics themselves that are incisive and that get to the heart of what’s ridiculous or dysfunctional about our financial, cultural, and political systems.

What if we started a newspaper that took its cues directly from the Onion, and rewrote every article in a straight, anti-satire way? Would that newspaper be better or worse than the New York Times? I claim it would be more bizarre but also more relevant to our lives. It may miss entire swaths of typical news coverage but then again it would cover certain things in a more holistic light.

For example, what would a anti-satirist do with this article? Or this one? Just having someone seriously articulate why these things are so funny would be a good start, and an article I’d love to read.

Go Rays!

As a long-time (yes since they sucked) Red Sox fan, let me just say, the Tampa Bay Rays totally deserve to be in the play-offs. They made me a fan last night with an absolutely amazing game.

Occupy Wall Street—Report

This is a guest post by FogOfWar.

I was originally going to lead with a tongue-in-cheek comment (later in the post now), but then the NYPD did something colossally stupid. If you haven’t seen it, here’s the video from this last weekend. It pretty much speaks for itself.

There’s a lot to be said about freedom of expression and police overreaction. I’ve been to see the protests a number of times, and they’ve never been violent and in fact seem pretty well trained in the confines of freedom of assembly in the US legal system. Using mace against an imminent threat of violence is OK for the police, but the video seems to show no threatening moves made at all (and it runs for a good period before the police attack so it wasn’t edited out).

I’d suggest the NYPD be shown the following video (taken from the protests in Greece) to demonstrate when things reach a level where force might be an appropriate response. Note that the crowd is attacking with sticks, Molotov cocktails and a fucking bowling ball. In contrast, the NYPD appears to be pepper spraying people for just holding signs and walking down the street. What the fuck?

There are maybe a few hundred people consistently protesting at “Occupy Wall Street” for about 10 days now. It’s got a definite crunchy vibe to the center. Drumming and Mohawks are mandatory:

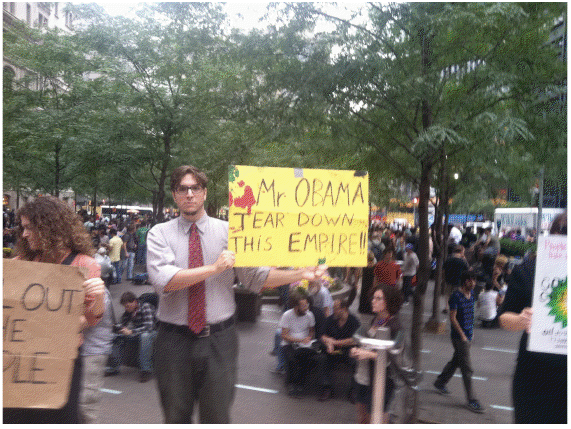

But also a (growing?) contingent of more mainstream participants like this one:

Here’s a crowd shot for scale:

And some people painting signs:

And then of course, there’s the dreaded “consensus circle”:

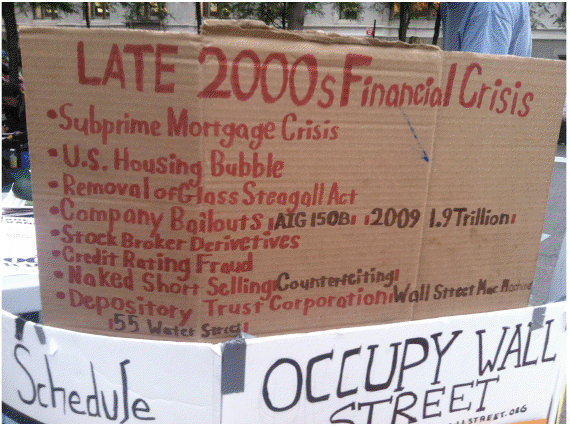

It’s hard to tell what they really want to happen—this was up at one of the information booths (but then down the next time I went):

Misspelled “derivatives”, and there are some things on that list that are spot on and then others that are just weird and irrelevant (DTC? Really?). I don’t think you can hold that against them though. I work in the industry, and I’ve been spending the last three years thinking about this stuff and I still find it confusing and hard to come up with a cohesive plan of what I think should be done. At least these people are doing something, even if it’s a bit incoherent at times.

I have to end with my all time favorite sign from the protest. Someone was looking for good cardboard and inadvertently came up with the following:

“Delicious pizza to pay off the taxpayers”. Now that’s a slogan I think we can all rally behind!

-FoW

The flat screen TV phenomenon

Do you remember, back in 2005 or 2006 or even up to early 2008, how absolutely everyone seemed to be buying flat screen TVs? And not only one, they’d actually buy new ones when new models came out, or ones with different high definition properties. And not just people who could afford it, either. The marketers did an excellent job in somehow convincing people that they needed these flat screen TVs so bad that they should just put it on their credit cards, all 3 thousand dollars of it, or whatever those things cost.

I don’t know exactly how much they cost because I never bought one. The last TV we bought was in 1997 and it still works, for the most part, although it’s really hard to turn it on and off. When it finally kicks the bucket I’m thinking we go without a TV, since TV pretty much sucks anyway. When we do watch it, it’s for live sports (local, or nationally televised, since we don’t pay for cable). Baseball we watch or listen to on the computer.

I was reminded of the the “flat screen TV era” by my friend Ian Langmore the other day when we were discussing household debt amnesty. His argument against debt amnesty for consumers was that they might spend it on crappy things. His example was luxury dog poo, but I’ve been obsessed with the flat screen TV phenomenon ever since a friend of mine, who was $120,000 in debt and didn’t have a salary, somehow managed to buy a flat screen TV in 2007. It blew me away in terms of wasteful consumerism. Ian found this unbelievable blog which kind of sums up my concerns.

In Ian’s opinion, the danger of amnesty, or any system where money is put willy-nilly into the hands of consumers, is twofold:

1) We waste time on unproductive activities. E.g. people spent time buying/building cars that are unneeded.

2) If a miscalculation is made, then the over-leveraged money-go-round stops with a huge mis-balance. E.g. home mortgage crisis.

These are very good points, and put together form a lesson we somehow can’t learn, although perhaps that can be partially explained by this article.

I have two thoughts. First, I’m also uncomfortable putting money in the hands of irresponsible consumers. But the truth is, the way I see it is currently working, we are already putting money in the hands of irresponsible bankers (that’s what the term “injection of liquidity” really means), and they are not doing anything with it, so let’s try something else. In other words, an alternative unpleasant idea.

Second, I don’t think we are going to see a new wave of flat screen TV buying any time soon. If we put money into the hands of consumers right now, I think we’d see them pay down their debts, go to the doctor, and buy jeans for their kids. Of course, there is always someone whose pockets burn with cash, and they would waste money in any situation. Let’s face it, though, credit is tight right now compared to the mid-2000’s. In fact, since economists seem to have a tough time spotting bubbles until afterwards, maybe we can take “a huge part of the population starts buying useless gadgets on credit” as almost a definition, or at least a leading indicator. Then at least there would be some point to all of that wasteful spending.

In German beard circles, tensions are high.

Best article ever about beards.

Are SAT scores going down?

I wrote here about standardizing tests like the SAT. Today I wanted to spend a bit more time on them since they’ve been in the news and it’s pretty confusing what to think.

First, it needs to be said that, as I have learned in this book I’m reading, it’s probably a bad idea to make statements about learning when you make “cohort-to-cohort comparisons” instead of following actual students along in time. In other words, if you compare how well the 3rd grade did in a test one year to the next, then for the most part the difference could be explained by the fact that they are different populations or demographics. Indeed the College Board, which administers the SAT, explains that the scores went down this year because more and more diverse kids are taking the test. So that’s encouraging, and it makes you think that the statement “SAT scores went down” is in this case pretty meaningless.

But is it meaningless for that reason?

Keep in mind that these are small differences we’re talking about, but with a pretty huge sample size overall. Even so, it would be nice to see some errorbars and see the methodology for computing errorbars.

What I’m really worried about though is the “equating” part of the process. That’s the process by which they decide how to compare tests from year to year, mostly by having questions in common that are ungraded. At least that’s what I’m guessing, it’s actually not clear from their website.

My first question is, are they keeping in mind the errors for the equating process? (I find it annoying how often people, when they calculate errors, only calculate based on the very last step they take in a very sketchy overall process with many steps.) For example, is their equating process so good that they can really tell us with statistical significance that American Indians as a group did 2 points worse on the writing test (see this article for numbers like this)? I am pretty sure that’s a best guess with significant error bars.

Additional note: found this quote in a survey paper on equating methodologies (top of page 519):

Almost all test-equating studies ignore the issue of the standard error of the equating

function.

Second, I’m really worried about the equating process and its errorbars for the following reason: the number of repeat testers varies widely depending on the demographic, and also from year to year. How then can we assess performance on the “linking questions” (the questions that are repeated on different tests) if some kids (in fact the kids more likely to be practicing for the test) are seeing them repeatedly? Is that controlled for, and how? Are they removing repeat testers?

This brings me to my main complaint about all of this. Why is the SAT equating methodology not open source? Isn’t the proprietary “intellectual property” in the test itself? Am I missing a link? I’d really like to take a look. Even better of course if the methodology is open source (as in there’s an available script which actually computes the scores starting with raw data) and the data is also available with anonymization of course.

Do higher taxes kill jobs?

Being a mathematician, I find myself forced to consider statements like “higher taxes kill jobs” as statements of theorems with missing stated assumptions. How could you fill in the assumptions and prove this theorem?

First I think about extreme cases- sometimes extreme situations need fewer assumptions, they kind of spill out as obvious. So here’s one, the tax rate is at 80%, what would happen if we raised taxes? My first reaction is, 80%!? That must mean you have way too much government and regulation and for those reasons businesses are probably already quite pinned down and don’t have lots of freedom- don’t tax them more, that will make their good ideas (if they have them) all the more suffocated. Just think of the paperwork you’d need to go through in a society that government-heavy, to hire someone.

What’s another extreme case? How about taxes are super low, more like fees for doing business. Then no, I don’t think raising them a moderate amount would kill jobs at all, in fact it may introduce enough government to make things less wild west and safer for businesses to operate.

So in other words at some level I buy the anti-regulation anti-government angle. I don’t want super duper high taxes because I think it encourages too much bureaucracy and that stuff is boring (but some amount of it is necessary to make things safe).

Moreover I’m assuming that governments generally use taxes to protect people from food poisoning and the like, regulate to force companies to play fair, and as social safety nets when things go bad, and that they’re not particularly efficient. Those of course are my assumptions, which anyone can disagree with.

But in terms of proving my theorem, I’m stuck thinking it’s more like, there’s some point in between very low and very high taxes where it gradually becomes true that raising taxes more will indeed start to kill jobs.

How about our situation now? Right now we have pretty low taxes by historical measures, and moreover the known loopholes mean that businesses (especially big ones with fancy lawyers) pay much less than their stated tax rate.

Why, in this case, would a moderate bump in their tax rates kill jobs?

Here’s a possible argument: if higher taxes actually encourage more regulation, then that could be a major problem for smaller businesses, who don’t have the margin for dealing with hiring that many lawyers for compliance issues. Although this article argues that “regulation kills jobs” is an invalid statement in general.

Pet peeve of mine: when you hear conservatives talk about killing jobs, they often frame it in terms of struggling small businesses, often run by a woman. But it’s easy enough to imagine that we introduce taxes and regulation that are easier for small businesses to avoid smothering them. It’s really the huge businesses that we want to see start hiring, and it’s the huge businesses that pay so little taxes.

Here’s another one: if you raise taxes people will spend their cash on taxes instead of hiring people. But wait, that doesn’t apply right now when we have so much frigging cash on hand (and hidden in other countries). In other words, companies are not not hiring people for cash flow reasons, it’s because they don’t see the demand.

In the end I can’t see how to prove or even argue that theorem, assuming today’s conditions. Would love to hear the argument I’m missing.

Back from Strata Jumpstart

So I gave my talk yesterday at the Strata Jumpstart conference, and I’ll be back on Thursday and Friday to attend the Strata Conference conference.

I was delighted to meet a huge number of fun, hopeful, and excited nerds throughout the day. Since my talk was pretty early in the morning, I was able to relax afterwards and just enjoy all the questions and remarks that people wanted to discuss with me.

Some were people with lots of data, looking for data scientists who could analyze it for them, others were working with packs of data scientists (herds? covens?) and were in search of data. It was fun to try to help them find each other, as well as to hear about all the super nerdy and data-driven businesses that are getting off the ground right now. It certainly was an optimistic tone, I didn’t feel like we were in the middle of a double-dip recession for the entire day (well, at least til I got home and looked at the Greek default news).

Conferences like these are excellent; they allow people to get together and learn each others’ languages and the existence of the new tools and techniques in use or in development. They also save people lots of time, make fast connection that would otherwise difficult or impossible, and of course sometimes inspire great new ideas. Too bad they are so expensive!

I also learned that there’s such thing as a “data scientist in residence,” held of course by very few people, which is the equivalent in academic math to having a gig at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Wow. I still haven’t decided whether I’d want such a cushy job. After all, I think I learn the most when I have reasonable pressure to get stuff done with actual data. On the other hand maybe that much freedom would allow one to do really cool stuff. Dunno.

How do you standardize tests?

I’m reading an interesting book by Douglas Harris about the value-added model movement, called Value-added Measures in Education, available here from Harvard Education Press. Harris goes into a very reasonable critique of how “snapshot” views of students, teachers, and school are a very poor assessment of teacher ability, since they are absolute measurements rather than changes in knowledge. Kind of like comparing the Dow to the S&P and concluding that you should definitely invest in Dow stocks since they are ten times better, it’s all about the return on a test score or an index, not the absolute number, when you are trying to gauge learning or profit.

His goal of the book is to explain how value-added models work, how they measure learning, how the take into account things like poverty level and other circumstances beyond the control of the school or the teachers, and other such factors. In his introduction he also promises not to be unreasonable about applying the results of these tests beyond where it makes sense. He certainly seems to be a smart guy; smart enough to know about errors and the problems with badly set up incentives – he uses the financial crisis as a model of how not to do it. I’m hopeful!

Here’s what I am interested in talking about today, which is how the “standardized” gets into standardized testing, because already at this point the mathematical modeling is pretty tricky (and involves lots of choices). There are many ways a test is ultimately standardized, assuming for simplicity that it’s a national test given at many grade levels yearly (pretend it’s an SAT that every grade takes):

- the test is normalized for being harder or easier than it was last year, for each grade’s test separately, and sometimes per question as well,

- the grading is normalized so that a student who learns exactly as much “as is expected” gets the same grade from year to year, and

- the grading is further normalized so that a student who gets 10 more points than expected in 3rd grade is doing as well as if she got 10 extra points in 4th grade.

One way of accomplishing all of the above would be to draw a histogram of raw results per year and per grade and normalize that distribution of raw scores by some standard mean and standard deviation, just as you would make a normal distribution standard, i.e. mean 0 and standard deviation 1. In fact, go ahead and demean it and divide by the standard deviation. That’s the first thing I’d do.

But if you actually do that, then you lose lots of the information you are actually trying to glean. Namely, how could you then conclude if students are doing better or worse than last year? I’m sure you’ve seen the recent news that SAT scores have fallen this year from last. I guess my question is, how can they tell? If we do something as simple as what I suggested, then the definition of doing as well “as is expected” is that you did “as well as the average person did”. But clearly this is not what the SAT people do, since they claim people aren’t doing as well as they used to. So how are they standardizing their test?

It isn’t really explained here or here, but there are clues. Namely, if you give 3rd and 4th graders some of the same questions on a given year, then you can infer how much better 4th graders do on those questions than 3rd graders do, and you can use that as a proxy for how to scale between grades (assuming that those questions represent the general questions well). Next, since you can’t repeat questions (at least questions that count towards the score) between years, because the stakes are too high and people would cheat, you can instead have ungraded sections that have repeated questions which give you a standard against which to compare between years. In fact the SAT does have ungraded sections, and so did the GREs as I recall, and my guess is this is why.

That brings up the question, do all standardized tests have ungraded sections? Is there some other clever way to get around this problem? Also in my mind, how well does standardization work, and what is a way to test it?

What the hell is going on in Europe?

This week has been particularly confusing when it comes to the European debt crisis. It’s complicated enough to think about the various countries, with their various current debt problems, future debt problems, and austerity plans, not to mention how they typically interact at the political level versus how the average citizen is affected by it all. But this week we’ve seen weird and coordinated intervention by a bunch of central banks to address a so-called “liquidity crisis”.

What is this all about? Is it actually a credit crisis disguised as a liquidity crisis? Is it just another stealth way to bail out huge banks?

I’m going to take a stab at answering these questions, at the risk of talking out of my ass (and when has that ever stopped me?).

Finance is a big messy system, and it’s hard to know where to begin on the merry-go-round of confusion, but let’s start with European banks since they are the ones in need of funding.

European banks have lots of euros on hand, just as American banks have lots of dollars, because of the actual deposits they hold. However, European banks invest in American things (like businesses) that need them to come up with short term funding denominated in dollars. Similarly American banks invest in Europe, but that’s not really relevant to the discussion yet.

How do European banks get these short term (3 month) loans? Historically they do a large majority of it through money-markets: much of the money people have in banks is funneled to huge vats called money markets, and the fund managers of those vats are very very conservatively trying to make a bit of interest on them. In fact they were burned in the credit crisis, when they famously “broke the buck” on Lehman short-term loans.

Well, guess what, those same American money managers are avoiding European short-term loans right now, because they are super afraid of losing money on them. So that source of funding has dried up. Note that this is a credit problem: the money market managers do not trust the banks to be around in 3 months.

Another source of funding for the European banks’ American investments has been just to use their euros, exchange them to dollars (the currency market is very very large and liquid, especially on this particular exchange), then wait until the term of the short-term financing is over, and then convert the dollars back to euros. What actually happens, in fact, is that they borrow euros (at the going rate of 1%), do the exchange, then financing, and then get their money back in the future.

The guys who work at the European banks and who do this short-term financing aren’t allowed to take on the risk that the exchange rate is going to violently change between now and when the short-term term is over. Therefore they need to hedge the risk, which means they have to have a guarantee that the dollars they get out at the end of the term will be turned into a reasonable number of euros.

This kind of guarantee is called a currency swap, and the market for those is also very large and liquid, but has been less liquid recently because of the one-sidedness of this problem: European banks need short-term dollars but American banks don’t need euros at the same rate at the same maturity. So the end result is that the swaps are very very expensive for European banks.

Let’s put this another way, the way that seems strangest and most confusing: right now the European banks can borrow at 1% in euros but at 4% in dollars (for three month maturity), and more generally the demand for USD seems to be skyrocketing recently from all over the place. Does this mean there’s an arbitrage opportunity somewhere? The swaps market is at 3% so no obvious arbitrage. More likely it means that the markets are expecting the exchange rate to drastically change, or at least they are pricing in the risk of it changing violently in the very near future. (The strangest thing to me is why it hasn’t just changed the spot exchange rate as well.)

By the way, a pet peeve or two I have with people talking about arbitrage: firstly, many people use the term so loosely it means nothing at all, as when they take risk over time (exposing themselves to the possibility of an exchange rate change for example). But even here, I’m misusing the term, since in an arbitrage it’s literally supposed to be a way to make money risk-free, but the whole point of my post is that this is really all about counter-party risk! In other words, there’s no arbitrage opportunity to get into contracts with people where you’d make money except if they go bankrupt tomorrow, when there’s a good chance that will happen.

The bottomline is that although the ECB and the Fed and the other central banks have spun this as a coordinated effort to help out a liquidity squeezed but functional market, it doesn’t pass the smell test. What’s actually happening is that the shoddy accounting and investments of French banks and others is not being trusted by American money market managers who are wise to them.

One more thing: the collateral being asked of the European banks is purportedly of low standard, which is to say the ECB is allowing thing like Greek debt as collateral, which wouldn’t past muster with other institutions (or with U.S. money markets!). In that sense this can be seen as a stealth bailout, although I think not the first one in Europe under that definition. This isn’t going away until they figure out how to deal with the Greek debt problem.

Politics: the good news and the bad news

I love Elizabeth Warren. I think she’s real, she cares about people, she’s smart and tough, and she’s incorruptible. The bizarre news, under these circumstances, is that she’s running for Congress. Is she too good to win in politics? Don’t you have to be a slime ball? Don’t you need to attract and sell out to megacorporations to succeed? We shall see. It could be really great.

And just in case you think I’m being too cynical, please read this. It’s an absolutely stunning, depressing insider’s view of the Republic Party from Mike Lofgren, who retired in June after 28 years as a Congressional staffer, having served 16 years as a professional staff member on the Republican side of both the House and Senate Budget Committees.

Monday morning links

First, if you know and love the Statistical Abstract as much as I do, then help save it! Go to this post and follow the instructions to appeal to the census to not discontinue its publication.

Next, if you want evidence that it sucks to be rich, or at least it sucks to be a child of rich people, then read this absolutely miserable article about how rich people control and manipulate their children. Note the entire discussion about “problem children” never discusses the possibility that you are actually a lousy, money-obsessed and withholding parent.

Next, how friggin’ cool is this? Makes me want to visit Mars personally.

And also, how cool is it that the World Bank is opening up its data?

Finally, good article here about Bernanke’s lack of understanding of reality.

Some cool links

First, right on the heels of my complaining about publicly available data being unusable, let me share this link, which is a FREAKING cool website which allows people to download 2010 census data in a convenient and usable form, and also allows you to compare those numbers to the 2000 census. It allows you to download it directly, or by using a url, or via SQL, or via Github. It was created by a group called Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) for other journalists to use. That is super awesome and should be a model for other people providing publicly available data (SEC, take notes!).

Next, I want you guys to know about stats.org, which is a fantastic organization which “looks at major issues and news stories from a quantitative and scientific perspective.” I always find something thought-provoking and exciting when I go to their website. See for example their new article on nature vs. nurture for girls in math. Actually I got my hands on the original paper about this and I plan to read it and post my take soon (thanks, Matt!). Also my friend Rebecca Goldin is their Director of Research (and is featured in the above article) and she rocks.

Along the same lines, check out straightstatistics.org which is based in the UK and whose stated goal is this: “we are a campaign established by journalists and statisticians to improve the understanding and use of statistics by government, politicians, companies, advertisers and the mass media. By exposing bad practice and rewarding good, we aim to restore public confidence in statistics. which checks the statistics behind news and politics.” Very cool.

Good for the IASB!

There’s an article here in the Financial Times which describes how the International Accounting Standards Board is complaining publicly about how certain financial institutions are lying through their teeth about how much their Greek debt is worth.

It’s a rare stand for them (in fact the article describes it as “unprecedented”), and it highlights just how much a difference in assumptions in your model can make for the end result:

Financial institutions have slashed billions of euros from the value of their Greek government bond holdings following the country’s second bail-out. The extent to which Greek sovereign debt losses were acknowledged has varied, with some banks and insurers writing down their holdings by a half and others by only a fifth.

It all comes down to whether the given institution decided to use a “mark to model” valuation for their Greek debt or a “mark to market” valuation. “Mark to model” valuations are used in accounting when the market is “sufficiently illiquid” that it’s difficult to gauge the market price of a security; however, it’s often used (as IASB is claiming here) as a ruse to be deceptive about true values when you just don’t want to admit the truth.

There’s an amusingly technical description of the mark to model valuation for Greek debt used by BNP Paribas here. I’m no accounting expert but my overall takeaway is that it’s a huge stretch to believe that something as large as a sovereign debt market is illiquid and needs mark to model valuation: true, not many people are trading Greek bonds right now, but that’s because they suck so much and nobody wants to sell them at their true price since then they’d have to mark down their holdings. It’s a cyclical and unacceptable argument.

In any case, it’s nice to see the IASB make a stand. And it’s an example where, although there are two possible assumptions one can make, there really is a better, more reasonable one that should be made.

That reminds me, here’s another example of different assumptions changing the end result by quite a lot. The “trillion dollar mistake” that S&P supposedly made was in fact caused by them making a different assumption than that which the White House was prepared to make:

As it turns out, the sharpshooters were wide of the target. S&P didn’t make an arithmetical error, as Summers would have us believe. Nor did the sovereign-debt analysts show “a stunning lack of knowledge,” as Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner claimed. Rather, they used a different assumption about the growth rate of discretionary spending, something the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office does regularly in its long-term outlook.

CBO’s “alternative fiscal scenario,” which S&P used for its initial analysis, assumes discretionary spending increases at the same rate as nominal gross domestic product, or about 5 percent a year. CBO’s baseline scenario, which is subject to current law, assumes 2.5 percent annual growth in these outlays, which means less new debt over 10 years.

Is anyone surprised about this? Not me. It also goes under the category of “modeling error”, which is super important for people to know and to internalize: different but reasonable assumptions going into a mathematical model can have absolutely huge effects on the output. Put another way, we won’t be able to infer anything from a model unless we have some estimate of the modeling error, and in this case we see the modeling error involves at least one trillion dollars.

We didn’t make money on TARP!

There’s a pretty good article here by Gretchen Morgenson about how the banks have been treated well compared to average people- and since I went through the exercise of considering whether corporations are people, I’ve decided it’s misleading yet really useful to talk about “treating banks” well- we should keep in mind that this is shorthand for treating the people who control and profit from banks well.

On thing I really like about the article is that she questions the argument that you hear so often from the dudes like Paulson who made the decisions back then, namely that it was better to bail out the banks than to do nothing. Yes, but weren’t there alternatives? Just as the government could have demanded haircuts on the CDS’s they bailed out for AIG, they could have stipulated real conditions for the banks to receive bailout money. This is sort of like saying Obama could have demanded something in return for allowing Bush’s tax cuts for the rich to continue.

But on another issue I think she’s too soft. Namely, she says the following near the end of the article:

As for making money on the deals? Only half-true, Mr. Kane said. “Thanks to the vastly subsidized terms these programs offered, most institutions were eventually able to repay the formal obligations they incurred.” But taxpayers were inadequately compensated for the help they provided, he said. We should have received returns of 15 percent to 20 percent on our money, given the nature of these rescues.

Hold on, where did she get the 15-20%? As far as I’m concerned there’s no way that’s sufficient compensation for the future option to screw up as much as you can, knowing the government has your back. I’d love to see how she modeled the value of that. True, it’s inherently difficult to model, which is a huge problem, but I still think it has to be at least as big as the current credit card return limits! Or how about the Payday Loans interest rates?

I agree with her overall point, though, which is that this isn’t working. All of the things the Fed and the Treasury and the politicians have done since the credit crisis began has alleviated the pain of banks and, to some extent, businesses (like the auto industry). What about the people who were overly optimistic about their future earnings and the value of their house back in 2007, or who were just plain short-sighted, and who are still in debt?

It enough to turn you into an anarchist, like David Graeber, who just wrote a book about debt (here’s a fascinating interview with him) and how debt came before money. He thinks we should, as a culture, enact a massive act of debt amnesty so that the people are no longer enslaved to their creditors, in order to keep the peace.

I kind of agree- why is it so much easier for institutions to get bailed out when they’ve promised too much than it is for average people crushed under an avalanche of household debt? At the very least we should be telling people to walk away from their mortgages or credit card debts when it’s in their best interest (and we should help them understand when it is in their best interest).

Should short selling be banned?

Yesterday it was announced that the short selling ban in France, Italy, and Spain for financial stocks would be continued; there’s also an indefinite short selling ban in Belgium. What is this and does it make sense?

Short selling is mathematically equivalent to buying the negative of a stock. To see the actual mechanics of how it works, please look here.

Typically people at hedge funds use shorts to net out their exposure to the market as a whole: they will go long some bank stock they like and then go short another stock that they are neutral to or don’t like, with the goal of profiting on the difference of movements of the two – if the whole market goes up by some amount like 2%, it will only matter to them how much their long position outperformed their short. People also short stocks for direct negative forecasts on the stock, like when they detect fraud in accounting of the company, or otherwise think the market is overpricing the company. This is certainly a worthy reason to allow short selling: people who take the time to detect fraud should be rewarded, or otherwise said, people should be given an incentive to be skeptical.

If shorting the stock is illegal, then it generally takes longer for “price discovery” to happen; this is sort of like the way the housing market takes a long time to go down. People who bought a house at 400K simply don’t want to sell it for less, so they put it on the market for 400K even when the market has gone down and it is likely to sell for more like 350K. The result is that fewer people buy, and the market stagnates. In the past couple of years we’ve seen this happen in the housing market, although banks who have ownership of houses through foreclosures are much less quixotic about prices, which is why we’ve seen prices drop dramatically more recently.

The idea of banning short-selling is purely political. My favorite quote about it comes from Andrew Lo, an economist at M.I.T., who said, “It’s a bit like suggesting we take heart patients in the emergency room off of the heart monitor because you don’t want to make doctors and nurses anxious about the patient.” Basically, politicians don’t want the market to “panic” about bank stocks so they make it harder to bet against them. This is a way of avoiding knowing the truth. I personally don’t know good examples of the market driving down a bank’s stock when the bank is not in terrible shape, so I think even using the word “panic” is misleading.

When you suddenly introduce a short-selling ban, extra noise gets put into the market temporarily as people “cover their shorts”; overall this has a positive effect on the stocks in question, but it’s only temporary and it’s completely synthetic. There’s really nothing good about having temporary noise overwhelm the market except for the sake of the politicians being given a few extra days to try to solve problems. But that hasn’t happened.

Even though I’m totally against banning short selling, I think it’s a great idea to consider banning some other instruments. I actually go back and forth about the idea of banning credit default swaps (CDS), for example. We all know how much damage they can do (look at AIG), and they have a particularly explosive pay-off system, by design, since they are set up as insurance policies on bonds.

The ongoing crisis in Europe over debt is also partly due to the fact that the regulators don’t really know who owns CDS’s on Greek debt and how much there is out there. There are two ways to go about fixing this. First we could ban owning CDS unless you also own the underlying bond, so you are actually protecting your bond; this would stem the proliferation of CDS’s which hurt AIG so badly and which could also hurt the banks holding Greek bonds and who wrote Greek CDS protection. Alternatively, you could enforce a much more stringent system of transparency so that any regulator could go to a computer and do a search on where and how much CDS exposure (gross and net) people have in the world. I know people think this is impossibly difficult but it’s really not, and it should be happening already. What’s not acceptable is having a political and psychological stalemate because we don’t know what’s out there.

There are other instruments that definitely seem worthy of banning: synthetic over-the-counter instruments that seem created out of laziness (since the people who invented them could have approximated whatever hedge they wanted to achieve with standard exchange-traded instruments) and for the purpose of being difficult to price and to assess the risk of. Why not ban them? Why not ban things that don’t add value, that only add complexity to an already ridiculously complex system?

Why are we spending time banning things that make sense and ignoring actual opportunities to add clarity?

Demographics: sexier than you think

It has been my unspoken goal of this blog to sex up math (okay, now it’s a spoken goal). There are just too many ways math, and mathematical things, are portrayed and conventionally accepted as boring and dry, and I’ve taken on the task of making them titillating to the extent possible. Anybody who has ever personally met me will not be surprised by this.

The reason I mention this is that today I’ve decided to talk about demographics, which may be the toughest topic yet to rebrand in a sexy light – even the word ‘demographics’ is bone dry (although there have been lots of nice colorful pictures coming out from the census). So here goes, my best effort:

Demographics

Is it just me, or have there been a weird number of articles lately claiming that demographic information explain large-scale economic phenomena? Just yesterday there was this article, which claims that, as the baby boomers retire they will take money out of the stock market at a sufficient rate to depress the market for years to come. There have been quite a few articles lately explaining the entire housing boom of the 90’s was caused by the boomers growing their families, redefining the amount of space we need (turns out we each need a bunch of rooms to ourselves) and growing the suburbs. They are also expected to cause another problem with housing as they retire.

Of course, it’s not just the boomers doing these things. It’s more like, they have a critical mass of people to influence the culture so that they eventually define the cultural trends of sprawling suburbs and megamansions and redecorating kitchens, which in turn give rise to bizarre stores like ‘Home Depot Expo‘. Thanks for that, baby boomers. Or maybe it’s that the marketers figure out how boomers can be manipulated and the marketers define the trends. But wait, aren’t the marketers all baby boomers anyway?

I haven’t read an article about it, but I’m ready to learn that the dot com boom was all about all of the baby boomers having a simultaneous midlife crisis and wanting to get in on the young person’s game, the economic trend equivalent of buying a sports car and dating a 25-year-old.

Then there are countless articles in the Economist lately explaining even larger scale economic trends through demographics. Japan is old: no wonder their economy isn’t growing. Europe is almost as old, no duh, they are screwed. America is getting old but not as fast as Europe, so it’s a battle for growth versus age, depending on how much political power the boomers wield as they retire (they could suck us into Japan type growth).

And here’s my favorite set of demographic forecasts: China is growing fast, but because of the one child policy, they won’t be growing fast for long because they will be too old. And that leaves India as the only superpower in the world in about 40 years, because they have lots of kids.

So there you have it, demographics is sexy. Just in case you missed it, let me go over it once again with the logical steps revealed:

Demographics – baby boomers – Bill Clinton – Monica Lewinsky – blow job under the desk. Got it?

I.P.O. pops

I’ve decided to write about something I don’t really understand, but I’m interested in (especially because I work at a startup!): namely, how IPO’s work and why there seem to be consistent pops. Pops are jumps in share price from the offering to the opening, and then sometimes the continued pop (or would that be fizz?) for the rest of the trading day. Here’s an article about the pop associated to LinkedIn a few weeks ago. The idea behind the article is that IPO pops are really bad for the companies in question.

The way a standard IPO works is that, when a company decides to go public, they hire an investment company to help them assess their value, i.e. form a sense of how many shares can be sold, and at what price.

A certain number of people (insiders and investors at the investment bank in particular) are then given the chance to buy some shares of the new company at the offering price. This is an obvious way in which the investment bank has an incentive to create a pop- their friends will directly benefit from pops. In fact the existence of pops and their accompanying incentives have inspired some people (like Google) to use Dutch auction methods instead of the standard.

And the myth is that there are consistent pops (here are some examples of truly outrageous pops during the dotcom bubble!). Is this really true? Or is it a case of survivorship bias? Or is there on average a pop the first day which fizzles out over the next week? I actually haven’t crunched the data, but if you know please do comment.

One question I want to know is, assuming that the pop myth is true, why does it keep happening? If it’s good for the investment bank but bad for the business, you’d think that businesses would, over time, train investment banks to stop doing this quite so much- they’d get bad reputations for big pops, or even possibly would get some of their fees removed, by contract, if the pop was too big (which would mean the investment bank hadn’t done its job well). But I haven’t heard of that kind of thing.

So who else is benefitting from pops? Is it possible that the investors themselves have an incentive to see a pop? While it’s true that the investors sell a bunch of their shares into the IPO to provide sufficient “float,” which they’d obviously like to see sold at a high price, they also have the opportunity to buy a restricted number of “directed shares“, which are shares they can buy at the offering price and then immediately sell; these they’d clearly like to buy at a low price and then see a pop. So I guess it depends on the situation for a given insider whether they are selling or buying more – I don’t know what the actual mix typically is, but I imagine it really depends on the situation; for example, there are always shared created out of thin air on an IPO day, so it will depend on how much of the float is coming from the investors and how much is coming from thin air.

The most standard thing though is for someone like an employee is to have common shares (or options to buy common shares) which they can only sell 6 months (or potentially more if the options are vested) after the IPO, which I guess means they are probably somewhat neutral to the pop, depending on its long term effect.

Speaking of long term effects, I think the biggest and most persuasive argument investment banks make to investors about stock evaluation, is that it’s better to underestimate the share price than to overestimate it. The argument is that a pop may hurt the business but it’s great for investors and thus the reputation value is overall good (this argument can obviously go too far if the pop is 50% and sustained), but that an overevaluation could result in not being able to sell the shares and having a sunken ship that never gets enough wind to sail. In other words, the risks are asymmetrical. I’m not sure this is actually true but it’s probably a good scare tactic for the investment banks to use to line their friends’ pockets.

Are Corporations People?

Recently Mitt Romney put his foot in his mouth when trying to deal with a heckler in Iowa. He said, “Corporations are people, my friend.” He’s gotten plenty of backlash since then, even though he attempted a softer follow-up with, “Everything corporations earn ultimately goes to people. Where do you think it goes?”

It makes me wonder two things. First, why is it viscerally repulsive (to me) that he should say that, and second, beyond the gut reaction, to what extent does this statement make sense?

The New York Times summed up the feeling pretty well with the statement, “…he seemed to reinforce another image of himself: as an out-of-touch businessman who sees the world from the executive suite.” Another way to say this is that the remark exposed a world view that I don’t share, and which goes back to this post containing the following:

Conservatives, for example, see business as primarily a source of social and economic good, achieved by the market mechanism of seeking to maximize profit. They therefore think government’s primary duty regarding businesses is to see that they are free to pursue their goal of maximizing profit. Liberals, on the other hand, think that the effort to maximize profit threatens at least as much as it contributes to our societies’ well-being. They therefore think that government’s primary duty regarding businesses is to protect citizens against business malpractice.

Fair enough- Mitt Romney doesn’t claim to be a liberal, after all. He was really doing us a favor by admitting how he sees things; heck, I wish all politicians would be susceptible to heckling and would go off-script and say what they actually mean every now and then.

In this way I can come to terms with the fact that Romney is essentially protective of corporations and their “human rights,” at least as an emotional response (like when discussing tax increases). But is he factually right? Are corporations equivalent to people in a legal or ethical way?

I’m no lawyer but it seems that, in certain ways, corporations are legally treated as persons, and that this has been an ongoing legal question for 200 years. In terms of political contributions, which is somehow easier to understand but maybe less systemically important, they are certainly treated like persons, in that there is no limit to the amount of money they can contribute politically (although this issue has gone back and forth historically).

Ethically, however, there seems to me to be a huge obstacle in considering corporations equivalent to people. Namely, it seems to be much easier to ascribe the rights of people to corporations than to ascribe the responsibilities of people to corporations. In particular, what if corporations behave badly and need to be punished? How do we follow through with that in a way that makes sense? Is there a death penalty for corporations? (This question originally came to me by way of Josh Nichols-Barrer, by the way)

The most obvious direct punishment we have for corporations is fines for accounting fraud or whatever, and the most obvious indirect punishment is market capitalization loss, i.e. the stock price goes down, if it’s a publicly traded company, or if not, reputation loss, which is vague indeed. However, in those cases it’s mostly the shareholders that suffer- the corporation itself, and its management, typically lives on.

Rarely, there is direct legal action against a decision maker at the company, but that certainly can’t count as a death penalty for the corporation itself, since the toxic culture which gave rise to those decisions is left intact. Even if we got serious and closed down a company, it’s not clear what effect that would have since a new legal entity could be re-formed with similar ideals and people (although the nuisance of doing this would be pretty substantial depending on the industry). But maybe that’s the best we can do: “moral bankruptcy” proceedings. Another problem with that idea is that many of the people who were in charge of the bad decisions would be the first to jump ship and go to other corporations to try again with more stealth; that’s certainly what I’ve seen happen in finance.

From my perspective, none of the punishments described above actually deter bad behavior in a meaningful way. If we treat corporations as people, then they would be people with a permanent diplomatic immunity; this doesn’t sit well with my sense of fairness or my sense of how people respond to incentives.