Archive

How the Value-Added Model sucks

One way people’s trust of mathematics is being abused by crappy models is through the Value-Added Model, or VAM, which is actually a congregation of models introduced nationally to attempt to assess teachers and schools and their influence on the students.

I have a lot to say about the context in which we decide to apply a mathematical model to something like this, but today I’m planning to restrict myself to complaints about the actual model. Some of these complaints are general but some of them are specific to the way the one in New York is set up (still a very large example).

The general idea of a VAM is that teachers are rewarded for bringing up their students’ test scores more than expected, given a bunch of context variables (like their poverty and last year’s test scores).

The very first question one should ask is, how good is the underlying test the kids are taking? This is famously a noisy answer, depending on how much sleep and food the kids got that day, and, with respect to the content, depends more on memory than on deep knowledge. Another way of saying this is that, if a student does a mediocre job on the test, it could be because they are learning badly at their school, or that they didn’t eat breakfast, or it could be that the teachers they have are focusing more on other things like understanding the reasons for the scientific method and creating college-prepared students by focusing on skills of inquiry rather than memorization.

This brings us to the next problem with VAM, which is a general problem with test-score cultures, namely that it is possible to teach to the test, which is to say it’s possible for teachers to chuck out their curriculums and focus their efforts on the students doing well on the test (which in middle school would mean teaching only math and English). This may be an improvement for some classrooms but in general is not.

People’s misunderstanding of this point gets to the underlying problem of skepticism of our teachers’ abilities and goals- can you imagine if, at your job, you were mistrusted so much that everyone thought it would be better if you were just given a series of purely rote tasks to do instead of using your knowledge of how things should be explained or introduced or how people learn? It’s a fact that teachers and schools that don’t teach to the test are being punished for this under the VAM system. And it’s also a fact that really good, smart teachers who would rather be able to use their pedagogical chops in an environment where they are being respected leave public schools to get away from this culture.

Another problem with the New York VAM is the way tenure is set up. The system of tenure is complex in its own right, and I personally have issues with it (and with the system of tenure in general), but in any case here’s the way it works now. New teachers are technically given three years to create a portfolio for tenure- but the VAM results of the third year don’t come back in time, which means the superintendent looking at a given person’s tenure folder only sees two years of scores, and one of them is the first year, where the person was completely inexperienced.

The reason this matters is that, depending on the population of kids that new teacher was dealing with, more or less of the year could have been spent learning how to manage a classroom. This is an effect that overall could be corrected for by a model but there’s no reason to believe was. In other words, the overall effect of teaching to kids who are difficult to manage in a classroom could be incorporated into a model but the steep learning curve of someone’s first year would be much harder to incorporate. Indeed I looked at the VAM technical white paper and didn’t see anything like that (although since the paper was written for the goal of obfuscation that doesn’t prove anything).

For a middle school teacher, the fact that they have only two years of test scores (and one year of experienced scores) going into a tenure decision really matters. Technically the breakdown of weights for their overall performance is supposed to be 20% VAM, 20% school-wide assessment, and 60% “subjective” performance evaluation, as in people coming to their classroom and taking notes. However, the superintendent in charge of looking at the folders has about 300 folders to look at in 2 weeks (an estimate), and it’s much easier to look at test scores than to read pages upon pages of written assessment. So the effective weighting scheme is measurably different, although hard to quantify.

One other unwritten rule: if the school the teacher is at gets a bad grade, then that teacher’s chances of tenure can be zero, even if their assessment is otherwise good. This is more of a political thing than anything else, in that Bloomberg doesn’t want to say that a “bad” school had a bunch of tenures go through. But it means that the 20/20/60 breakdown is false in a second way, and it also means that the “school grade” isn’t an independent assessment of the teachers’ grades- and the teachers get double punished for teaching at a school that has a bad grade.

That brings me to the way schools are graded. Believe it or not the VAM employs a binning system when they correct for poverty, which is measured in terms of the percentage of the student population that gets free school lunches. The bins are typically small ranges of percentages, say 20-25%, but the highest bin is something like 45% and higher. This means that a school with 90% of kids getting free school lunch is expected to perform on tests similarly to a school with half that many kids with unstable and distracting home lives. This penalizes the schools with the poorest populations, and as we saw above penalized the teachers at those schools, by punishing them for when the school gets a bad grade. It’s my opinion that there should never be binning in a serious model, for reasons just like this. There should always be a continuous function that is fit to the data for the sake of “correcting” for a given issue.

Moreover, as a philosophical issue, these are the very schools that the whole testing system was created to help (does anyone remember that testing was originally set up to help identify kids who struggle in order to help them?), but instead we see constant stress on their teachers, failed tenure bids, and the resulting turnover in staff is exactly the opposite of helping.

This brings me to a crucial complaint about VAM and the testing culture, namely that the emphasis put on these tests, which we’ve seen is noisy at best, reduces the quality of life for the teachers and the schools and the students to such an extent that there is no value added by the value added model!

If you need more evidence of this please read this article, which describes the rampant cheating on test in Atlanta, Georgia and which is in my opinion a natural consequence of the stress that tests and VAM put on school systems.

One last thing- a political one. There is idiosyncratic evidence that near elections, students magically do better on tests so that candidates can talk about how great their schools are. With that kind of extra variance added to the system, how can teachers and school be expected to reasonably prepare their curriculums?

Next steps: on top of the above complaints, I’d say the worst part of the VAM is actually that nobody really understands it. It’s not open source so nobody can see how the scores are created, and the training data is also not available, so nobody can argue with the robustness of the model either. It’s not even clear what a measurement of success is, and whether anyone is testing the model for success. And yet the scores are given out each year, with politicians adding their final bias, and teachers and schools are expected to live under this nearly random system that nobody comprehends. Things can and should be better than this. I will talk in another blog post about how they should be improved.

Data Viz

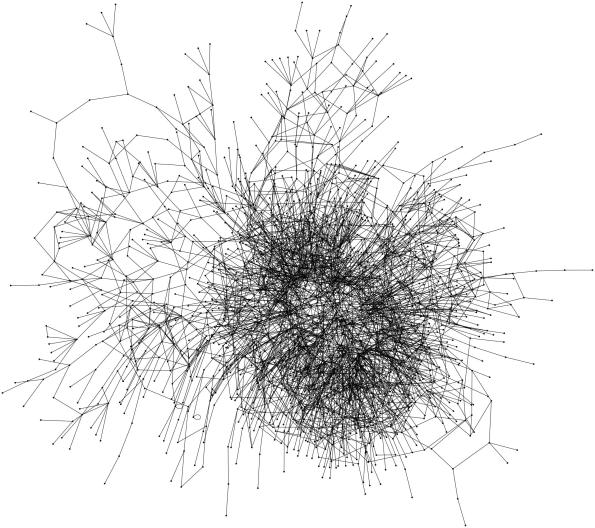

The picture below is a visualization of the complexity of algebra. The vertices are theorems and the edges between theorems are dependencies. Technically the edges should be directed, since if Theorem A depends on Theorem B, we shouldn’t have it the other way around too!

This comes from data mining my husband’s open source Stacks Project; I should admit that, even though I suggested the design of the picture, I didn’t implement it! My husband used graphviz to generate this picture – it puts heavily connected things in the middle and less connected things on the outside. I’ve also used graphviz to visualize the connections in databases (MySQL automatically generates the graph).

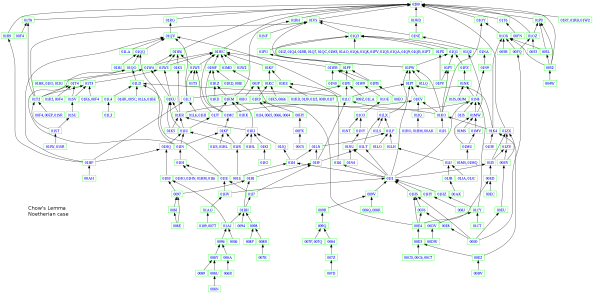

Here’s another picture which labels each vertex with a tag. I designed the tag system, which gives each theorem a unique identifier; the hope is that people will be willing to refer to the theorems in the project even though their names and theorem numbers may change (i.e. Theorem 1.3.3 may become Theorem 1.3.4 if someone adds a new result in that section). It’s also directed, showing you dependency (Theorem A points to Theorem B if you need Theorem A to prove Theorem B). This visualizes the results needed to prove Chow’s Lemma:

Some R code and a data mining book

I’m very pleased to add some R code which does essentially the same thing as my python code for this post, which was about using Bayesian inference to thing about women on boards of directors of S&P companies, and for this post, which was about measuring historical volatility for the S&P index. I have added the code to those respective posts. Hopefully the code will be useful for some of you to start practicing manipulating visualizing data in the two languages.

Thanks very much to Daniel Krasner for providing the R code!

Also, I wanted to mention a really good book I’m reading about data mining, namely “Data Analysis with Open Source Tools,” by Phillipp Janert, published by O’Reilly. He wrote it without assuming much mathematics, but in a sophisticated manner. In other words, for people who are mathematicians, the lack of explanation of the math will be fine, but the good news is he doesn’t dumb down the craft of modeling itself. And I like his approach, which is to never complicate stuff with fancy methods and tools unless you have a very clear grasp on what it will mean and why it’s going to improve the situation. In the end this is very similar to the book I would have imagined writing on data analysis, so I’m kind of annoyed that it’s already written and so good.

Speaking of O’Reilly, I’ll be at their “Strata: Making Data Work” conference next month here in New York, who’s going to meet me there? It looks pretty great, and will be a great chance to meet other people who are as in love with sexy data as I am.

Cool example of Bayesian methods applied to education

My friend Matt DeLand teamed up recently with Jared Chung to enter a data mining hacking contest sponsored by Donors Choose, which is a well-known online charity connecting low-income classrooms across the country to donors who get to choose which projects to support.

Their goal was to figure out how many of the thousands of projects up for funding were directly related to career preparation, and they performed a nifty Bayesian analysis to do it. Turns out it’s less than 1%!

Here’s their report. It’s really well explained in the 5-page pdf, if you have a few minutes.

Speaking of Donors Choose, it was featured at a HackNY Summer Fellows event I went to last week. The Summer Fellows is essentially like the math camp I taught at for high school students except it’s a computer camp for college students – same level of nerdy loveliness though. The event was a showcase for the fantastically nerdy student hackers, and there were some very impressive exhibits.

The hack involving Donors Choose shows a movie of how the donations are being given from some location to the classroom that’s benefitting on a big map of the country, and shown quickly from 2005 or so really exhibits how quickly the concept grew. It’s not unlike this visualization of the history of the world through the lens of Wikipedia.

What kind of math nerd job should you have?

Say you’re a math nerd, finishing your Ph.D. or a post-doc, and you’re wondering whether academics is really the place for you. Well I’ve got some advice for you! Actually I will have some advice for you, after you’ve answered a few questions. It’s all about fit. Since I know them best, I will center my questions and my advice around academic math vs. hedge fund quant vs. data scientist at a startup.

By the way, this is the advice I find myself telling people when they ask. It’s supposed to be taken over a beer and with lots of tongue in cheek.

1) What are your vices?

It turns out that the vices of the three jobs we are considering are practically disjoint! If you care about a good fit for your vices, then please pay attention.

NOTE: I am not saying that everyone in these fields has all of these vices! Far from it! It’s more like, if one or more of these vices drives you nuts, then you may get frustrated when you encounter them in these fields.

In academics, the major vices are laziness, envy, and arrogance. It’s perhaps true that laziness (at least outside of research) is typically not rewarded until after tenure, but at that point it’s pretty much expected, unless you want to be the fool who spends all of his(her) time writing recommendation letters and actually advising undergraduates. Envy is, of course, a huge deal in academics, because the only actual feedback is in the form of adulating rumor. Finally, arrogance in academics is kind of too obvious to explain.

At a hedge fund, the major vices are greed, covetousness, and arrogance. The number one source of feedback is pay, after all, so it’s all about how much you got (and how much your officemate got). Plus the isolation even inside your own office can lead to the feeling that you know more and more interesting, valuable, things than anyone else, thus the arrogance.

Finally, at a startup, the major vices are vanity, impatience, and arrogance. People really care about their image- maybe because they are ready to jump ship and land a better job as soon as they start to smell something bad. Plus it’s pretty easy in startups as well to live inside a bubble of self-importance and coolness and buzz. Thus the arrogance. On the flip side of vanity, startups are definitely the sexiest of the three, and the best source by far for good karaoke singers.

Okay it turns out they all have arrogance. Maybe that’s just a property of any job category.

2) What do you care about?

Do you care about titles? Don’t work at a startup.

Do you care about stability? Don’t work at a startup. Actually you might think I’d say don’t work at a hedge fund either, but I’ve found that hedge funds are surprisingly stable, and are full of people who are surprisingly risk averse. Maybe small hedge funds are unstable.

Do you care about feedback? Don’t work in academics.

Do you care about publishing? Don’t work outside academics (it’s sometimes possible to publish outside of academics but it’s not always possible and it’s not always easy).

Do you care about making lots of money? Don’t work in academics. In a startup you make a medium amount of money but there are stock options which may pan out someday, so it’s kind of in between academics and Wall St.

Do you care about being able to decide what you’re working on? Definitely stay in academics.

Do you care about making the world a better place? I’m still working on that one. There really should be a way of doing that if you’re a math nerd. It’s probably not Wall Street.

3) What do you not care about?

If you just like math, and don’t care exactly what kind of math you’re doing, then any of these choices can be really interesting and challenging.

If you don’t mind super competitive and quasi-ethical atmospheres, then you may really enjoy hedge fund quant work- the modeling is really interesting, the pay is good, and you are part of the world of finance and economics, which leaks into politics as well and is absolutely fascinating.

If you don’t mind getting nearly no vacation days and yet feeling like your job may blow up any minute, you may like working at a startup. The people there are real risk lovers, care about their quality of life (at least at the office!), and know how to throw a great party.

If you don’t mind being relatively isolated mathematically, and have enormous internal motivation and drive, then academics is a pretty awesome job, and teaching is really fun and rewarding. Also academic jobs have lots of flexibility as well as cool things like sabbaticals.

4) What about for women who want kids?

Let’s face it, the tenure clock couldn’t have been set up worse for women who want children. And startups have terrible vacation policies and child-care policies as well; it’s just the nature of living on a Venture Capitalist’s shoestring. So actually I’d say the best place to balance work and life issues is at an established hedge fund or bank, where the maternity policies are good; this is assuming though that your personality otherwise fits well with a Wall St. job. Actually many of the women I’ve met who have left academics for government research jobs (like at NASA or the NSA) are very happy as well.

Quit your job and become a data miner!?

Today my friend sent me this link, which is a pretty interesting and inspiring video of a talk from a guy from Google named Steve Yegge talking at an O’Reilly conference about how he’s sick of working on uninspiring projects involving social media and cat pictures, and wants to devote himself (and wants you to devote yourself) to more important questions about the nature of human existence. And he things the way to go about this is to become a data miner. I dig it! Of course he’s preaching to the choir at that conference. I wonder what other people will make of his appeal. Can one nerd change an entire culture of endless cat pic collections?

And lest you think that data mining is the answer to everything, here’s an article about how much data mining (in the form of “Value-added modeling”) can screw up other peoples’ lives when it’s misdirected. It’s written by John Ewing, who is the fabulous president of MfA, an organization that trains and mentors excellent college math majors to become effective math teachers in the New York Public School system and beyond- the “beyond” part is partly due to the crazy state of the budgets for new teachers here in NYC- we now have access to these wonderful MfA graduates but have hiring freezes so we can’t hire them. Also, my good friend Japheth Wood, a.k.a. the Math Wizard, is one of the MfA mentors.

I’m planning to post more soon on how crappy the value-added modeling (VAM) system is and how’s it’s a perfect example of mathematics being used to make things seem magical and therefore inaccessible, the exact opposite of what should be going on.

Happiest being sad

I’m done with math camp, and I am stopping off in Harvard Square on the way home to New York. I collected my two older sons from their first stint at overnight camp yesterday evening, a two-week middle-of-the-woods experience complete with a cold lake, dirty socks and sticky bunk beds. They were actually happy to see me, I could tell by the way they let me hug them in front of other people. I cried when I realized they had each grown two inches.

The past few days have been incredibly emotional. Somehow I started to pine for the program and for the students at the program before it had ended, and now I seem to miss my kids even though I have them back. I’m a mess of yearning, for a million things at once, and it seems like I’ve set myself up for this.

Of course when I think about it I absolutely have, and I guess the only real question is why I’m surprised. I keep falling in love with people and experiences that often even love me back, and even though I’m an experienced piner it doesn’t get any less painful. And yet it seems like the only alternative, if it is a choice I could even make, would be to close myself off from that openness and compassion and live in a careless void. That is certainly more terrifying to me than the safety of wistful suffering.

My friend Moon came to the program a couple of nights ago and gave a kick-ass talk to the students about the Banach-Tarski paradox. She stuck around that night for dinner and asked the program director, who has been doing this for 40 years, whether I had ever been shy. The director said, “No, Cathy was never shy, but she was memorable for the fact that she always said the same thing whenever someone started a conversation with her.” I had no idea what that could have been, and to tell you the truth I was a little worried what he’d say. So Moon asked, and he said the phrase was, “I love math!” It brought back a clear memory of the passion I had then and still have, and hopefully will always have. I am happy to be this sad.

Follow up on: math contests kind of suck

I have been really impressed with the comments and thoughts of my first post about how I think math contests kind of suck. Thinking about it some more, I’d like to make two corrections to my original thoughts as well as a clarification.

The first correction is that it’s the MAA, not the NSF, that mysteriously only seems to support contests, or at least for the most part supports contests and not enrichment. The NSF, as has been pointed out in the comments, mysteriously supports primarily college-level math enrichment (through REUs) instead of high-school level stuff, but that’s a different mystery.

The second correction is that, instead of saying about contests “most people don’t get close to winning, and in particular give those people the impression that because they lost a contest they don’t “have it” when it comes to math,” I should have said, “most people don’t get close to winning, and for the subset of people who care about winning, in gives them the impression that because they lost a contest they don’t “have it” when it comes to math.” In other words, I’m not discussing the subpopulation who don’t care if they win. (To those people I’d say: you are rare and you are lucky.)

Except I am discussing them, and this is where the clarification comes in. My point about girls is this: girls are more likely to be in the subpopulation of kids who care, and therefore more likely to be disappointed in themselves. In fact I would add that girls are more likely to underestimate their performance, even if it was great, and moreover they are more likely to do badly in the presence of the negative stereotype that tells them girls aren’t good at math.

These are all statistical statements. In particular, an argument that won’t convince me I’m wrong is something like: I’m a guy and I didn’t care if I won or lost and I loved (or hated) contests. That just means you are not in the population of kids I am talking about. Another argument that won’t convince me I’m wrong goes like this: I’m a guy and I cared and I did awesome. In fact won’t even really change my mind if a woman writes and said she cared and did badly (or well) but loved (or hated) them anyway. Because what I’m talking about is essentially a statistical statement, and idiosyncratic examples probably won’t change my mind.

In fact I’d argue that it’s very very difficult to prove or disprove my claim, at least with comments, because there’s a strong survivorship bias in place, namely that people who got scared away from math won’t be reading my blog at all. In order to give evidence to support or discredit my claim we would have to look at examples of populations which were or weren’t exposed to enrichment, versus contests, versus perhaps something else (like no math outside their classroom) and see who became mathematicians. Oh wait here’s something.

By the way, it’s important to make clear that I’m not suggesting stripping contest math out of the picture altogether. I think there’s a case to be made that they’re better than nothing. But we don’t need to settle for nothing! However, I think we should be creating alternatives that are not competitive or timed. I was very happy to hear about the month-long test and I also heard about a team 24-hour test (does anyone know the name of that and if it still exists?)

Two last tangentially related issues:

- I would argue that any time a bunch of nerd kids get together they have a blast. So we definitely should be getting math nerd kids together. We just shouldn’t be having them compete against each other. I claim they’d have an even better time that way.

- Also, has anyone else noticed the prevalence of girls who are good at competitions and very involved fathers? It’s really interesting. My dad is a mathematician too, and many (but not all) of the women mathematicians I know have heavily involved and/or mathematical dads.

Math contests kind of suck

I’m going to annoy quite a few people with this post, but I’ve been thinking about this for a while and it comes down to this: I think math contests for kids kind of suck.

Here’s the short version of my argument.

Math contests discourage most people who take them, because most people don’t get close to winning, and in particular give those people the impression that because they lost a contest they don’t “have it” when it comes to math. At the same time, although they are encouraging for a few people, it’s not clear to me that the kind of encouragement they give those kids is healthy. Finally, they are bad for women.

Now I will argue this more thoroughly.

The way math contests are set up nowadays, they start in middle school, at the school level, and if a student does well at a given test they move on to a larger stage, perhaps at the state level, and they typically culminate in a national test, or sometimes even an international test (in the case of the IMO).

This system sets up nearly all the participating students for a feeling afterwards of having not been good enough. It encourages competition over collaboration, which is a huge problem in my opinion, but even worse, it tends to make young people feel like they aren’t smart enough to be mathematicians. It is in fact well-documented that people seem to think that one is either born good at math or not, in spite of the fact that there’s ample evidence that practicing math competition-type problems makes you good at them (why else would Stuyvesant kids consistently beat other kids? Is it really possible that smart people somehow know to be born in New York?). The bottomline is that these extremely young, impressionable kids get early impressions that the contests are measuring their genetic abilities, and that they aren’t cutting it.

When I was in middle school, there were no math contests. I was lucky enough to have a great teacher in 7th grade, who let us nerds debate amongst ourselves for an entire class whether 0.999999… is equal to 1 or not. He put himself in the position of a mediator. It was a great moment for me, and made me realize how much creativity and originality could be involved in the process of making and understanding math.

When I got to high school, I was on the math team, and although I wasn’t bad, I also wasn’t good – and I felt bad about that, consistently. In fact there were definitely moments when I doubted my chances at becoming a mathematician. It is really a testament to my internal love for mathematics, combined with finding this math camp that I’m teaching at now, that motivated me to become a mathematician. If I had not had that 7th grade teacher, and if I had had earlier experiences being so-so at math contests, it’s possible I would have been turned off of math altogether.

Perhaps you are thinking, well of course there’s a selection process for math contests, because they select for people who are good at math! I discussed this with another mathematician today and he refined that argument as follows: some people are good at understanding concepts but can’t work out the details, and some people are good at working out details by rote but don’t understand the concepts- you can’t really be a good mathematician without both, and perhaps the contests select for the details people, but after all you need that aspect.

But I would go further: although I agree you can’t be a good mathematician without both, I don’t think the contests select for the details people. They actually select for people who do or don’t understand the concepts (probably do for the higher level tests) but who in any case are extremely fast at the details. I have never been particularly fast at working out the details of something from the conceptual understanding (for example, it takes me a long time to solve a 7x7x7 Rubik’s cube) but it turns out the Rubik’s cube doesn’t mind. And in fact mathematics in real life isn’t a timed tests- the idea that you need to be original and creative really quickly is just a silly, arbitrary way to select for talent.

I guess if you could have math competitions that aren’t timed then I might start being okay with them. Especially if they were collaborative.

The reason I claim math contests are bad for math is that women are particularly susceptible to feelings that they aren’t good enough or talented enough to do things, and of course they are susceptible to negative girls-in-math stereotypes to begin with. It’s not really a mystery to me, considering this, that fewer girls than boys win these contests – they don’t practice them as much, partly because they aren’t expected by others, nor do they expect themselves, to be good at them. It’s even possible that boys brains develop differently which makes them faster at certain things earlier- I don’t know and I don’t care, because I don’t think that the speed issue is correlated to later deep thought or mathematical creativity.

Finally, I don’t necessarily think that winning math contests is even all that good for the winners either. In spite of the fact that many of my favorite people are mathematicians who were excellent at contests, I also know quite a few people who were absolutely dominant in math contests in their youth who really seemed to suffer later on from that, especially in grad school. From my armchair psychologist’s perspective, I think it’s because they got addicted to the rush of doing math really fast and really well, and winning all these prizes, and when they get to grad school and realize how hard math really is, they can’t stand it.

One related complaint to this rant: it seems like there is way money out there for math contests for young people than there is for math enrichment programs like the program I’m working at now (I’m looking at you, NSF). Why is this? Probably a combination of the fact that’s it’s easier to organize, it seems quantitatively measurably “successful” because there’s a winner at the end, and maybe even because it makes the United States look good compared to other countries to have a winning IMO team- in other words, spin. Booo! How about throwing a little bit of money towards programs that sponsor a sense of collaborative, exploratory mathematics and which encourages women?

Before I get people too riled up, I will say this in favor of math contests: they do tend to expose kids to different kinds of math than is normally offered in their classrooms, which can be really great, and expansive, for kids that have drab math curriculums with drab teachers. Lots of kids first find out there’s math beyond quadratic equations by going to a math contest. That’s cool, but can’t we do it in a better way?

I love math nerd kids

So I’m almost at the end of my second week here at HCSSiM, and the pathetic truth is I already miss these kids. They are so freaking adorable, and of course I miss my own kids so much, that the emotional turmoil of the situation combines to create the reality that I am actually nostalgic for each moment with them before that moment happens. Pathetic!! It’s something about identifying with their nerdy selves finding each other and figuring out that they have a community of nerds that accepts them… whatever, now I’m tearing up. Pitiful.

As for what I’m teaching them, the first week it was number theory, number theory, and more number theory. Can you tell I like number theory? At the end of the first week I looked around and I saw a bunch of earnest faces wondering if I was going to prove yet another thing about relatively prime numbers and solving polynomials modulo n and I thought to myself, these kids are going to think there’s no other examples of proof by induction! How shameless! So this week I talked about graph theory. Next week: I’m going back to number theory. Yes I know, but it’s AWESOME. I’m going to talk about Farey numbers and continued fractions and maybe the Pell equation. They will know all about the golden ratio and maybe we’ll even measure each other’s faces. I can’t wait.

Last night we went to the director’s house and ate corn on the cob (we made the kids husk the corn- did you know teenagers today have mostly never husked corn before in their lives?) and pizza and we played “Mafia,” which was hilarious and sweetly innocent.

This weekend is “Yellow Pig day” at the camp program, which is a day where we celebrate yellow pigs and the number 17. We take this incredibly seriously, including making t-shirts with yellow pigs, having a 4-hour (feels like 17) talk about interesting properties of the number 17, and finally, singing yellow pig carols and eating a yellow pig cake at the end. It’s a wild time for math nerd kids. They will remember this and each other for the rest of their lives. Woohoo!!

Did I mention that I was a minor celebrity last night because I solved a 7x7x7 Rubik’s cube in front of them? This is status at its best. I even showed them my trick, and one of the kids came back to me at breakfast this morning proudly displaying his cube with a 3-cycle. Update: he has solved his entire cube using 3-cycles. Now he’s moving on to a dodecahedron puzzle.

LOVE these kids.

Short Post!

I’ve been told my posts are intimidatingly long, what with the twitter generation’s sound byte attention span. Normally I’d say, screw that! It’s because my ideas are so freaking nuanced they can’t be condensed to under a paragraph without losing their essence!

But today I acquiesce; here’s a short post containing at most one idea.

Namely, I’ve been getting pretty strong reactions online and offline regarding my post about whether an academic math job is a crappy job. I just want to set the record straight: I’m not even saying it’s a crappy job, I’m simply talking about someone else’s essay which describes it that way. But moreover, even if I were saying that, I would only be saying it’s crappy (which I’m not) compared to other jobs that very very smart mathy people could get. Obviously in the grand scheme of things it’s a very good job- safe working conditions, regular hours, well-respected, etc., and many people in this world have far crappier jobs and would love a job with those conditions. But relative to other jobs that math people could be getting, it may not be the best.

Many professors of math (you know who you are) have this weird narrow world view, that they feed their students, which goes something like, “if you want to be a success, you should be exactly like me (which is to say, an academic)”. So anyone who gets educated in a math department is apt to run into all these people who define success as getting tenure in an academic math department, and they just don’t know about or consider other kinds of gigs. It would be nice if there was a way to get a more balanced view of the pros and cons of all of the options.

Adding-up rules and Hockey Sticks

So I’m at the math program HCSSiM, teaching for three weeks in a “workshop,” which means I am responsible for teaching 12 teenagers the basic language and techniques of math- things like induction, proof by contradiction, the pigeon-hole principle, and how to correctly use phrases like “without loss of generality we can assume…” and “the following is a well-defined function…”, as well as familiarity with basic group theory, graph theory, number theory, cardinality, and fun things like Pascal’s triangle.

It’s really beautiful, classical math, and the students are eager and fantastically bright. They are my temporary brood, and I adore them and feed them chocolate at evening problem sets.

It’s also a fine opportunity to do some silly math doodling just for fun, the only rules being you can’t use a computer to look anything up until you’re done, and you can only use the stuff your kids at the program already learned. I’m going to describe what my mom and I, and then a junior (Amber Verser) and senior (Benji Fisher) staff member at the math program, figured out in the last couple of days. It’s super cool and turns out is at least 400 years old.

One of the most common examples of proof by induction is the formula for the sum of the counting numbers up to n:

1 + 2 + 3 + … + n = n(n+1)/2

And then, once you figure that out, you move on to the next case:

1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 + … + n^2 = n(n+1)(2n+1)/6.

If you’re really into it, you can put the next case on the problem set:

1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 + … + n^3 = (n(n+1)/2)^2.

Two obvious patterns are emerging when you add up successive dth powers up to n.

- It’s a polynomial of degree d+1, and

- The roots of the polynomial are symmetric about -1/2 (mom noticed this!).

How do you prove those two facts?

If you think it’s totally easy, stop reading now and give it a shot. There are about a million things you could try and none of them seem to work. I’ll wait.

…okay, let’s say you gave up, or already know, or don’t care. (Why are you reading still if you don’t care?!)

First let’s generalize the question to, if we add up values of some degree d polynomial for values i=0, 1, 2, …, n, then we want to prove the result is a degree d+1 polynomial in n. That this is equivalent to the first statement above is pretty easy to see by just re-arranging the terms of the double sum over i and over the terms of the polynomial in question. But it still seems like you need to know at least the answer to the question of what is a formula for 0^d + 1^d + 2^d + … + n^d, which is of course where we started.

But that’s where Pascal’s triangle comes in! We can generate Pascal’s triangle by the familiar “add up two consecutive numbers and put the answer below,” but we also can think of the element on the nth row and kth (tilted) column of Pascal’s triangle as the number of ways to choose k things from n things, which is referred to as “n choose k”, and where we start both the row and column counts at 0, not at 1. That definition satisfies the addition law because, if we have n things, we can label one as “special,” and then the choice of size k subsets of the n things divide into two categories: the size k subsets that contain the special guy and the ones that don’t. If they do, then we need only find k-1 other things in the remaining n-1 size set, and the number of ways to do that is given by the element on row n-1 and column k-1. If they don’t contain the special guy, we need to find k things in the remaining n-1 size set, and the number of ways to do that is given by the element on row n-1 and column k.

On the other hand, we also know a formula for the numbers in Pascal’s triangle: the guy on the nth row and kth column is given by a degree k polynomial in n, namely n!/k!(n-k)!. (This is because we can label all of the guys 1 through n, and just take the first k guys, and there are n! ways to label n things, but we don’t actually care about the order among the first k or among the last n-k.)

For example, in the second column, where we are looking at “n choose 2” for various n, we have the equation n(n-1)/2. This is a LOT like n^2 but has extra terms sticking on the end of lower order. When you’re looking at the third column, you’re working with the formula n(n-1)(n-2)/6, which is like the basic polynomial n^3 with extra stuff. In other words, the formula for “n choose k” is a degree k polynomial in n which we can think of as being a stand-in for n^k. Awesome.

The last ingredient is something called the “Hockey Stick Theorem,” which you gotta love just because of the name. It states that if we add up the values along a column, from the top of the rows down to the nth row, then the sum will be the number just below and to the right, and the entire picture will resemble a hockey stick.

The proof of the Hockey Stick Theorem is trivial- the answer is of course the sum of the two above it, and we have one in the sum already, but the other isn’t… but that other is the sum of the two above it, one of which is again already in the sum but the other isn’t… and you keep going until you get to the top edge of Pascal’s triangle, where the missing number is just 0.

Why does the Hockey Stick Theorem give us what we want? Going back to our generalized statement, we want to show the sum of values on a (any) degree d polynomial for i = 0, 1, 2, …, n is a degree d+1 polynomial. Well, use the dth column and make a hockey stick from the top to row n. Then the sum is on the (n+1)st row, in the (d+1)st column, which we know is a degree d+1 polynomial in n. Woohoo!

One way of looking at this is that we were actually asking the wrong question: instead of asking what the sum of the dth powers is we should have perhaps been asking what the sum of the dth column of Pascal’s triangle is; in other words, there is a better basis for the vector space of polynomials than x^d, namely “x choose d”. In fact, if there were an agreement in the world that actually the “x choose d” polynomials should be the standard basis, (by the way, these basis polynomials would be called “Pascalinomials”!) then the hockey stick theorem would be the last word on how do those things add up. As it stands, to figure out the actual formula for the sum of the dth powers for i=0, 1, 2, …, n, we need to write the first row of the change-of-basis matrix from one basis to the other.

As for the second question, we simply need to extend the definition of the sum F(n) of dth powers from 0 to n to the case where n is negative, by iteratively using the relation:

F(n) = F(n-1) + n^d, or

F(n-1) = F(n) – n^d.

Then we have F(0) = 0, F(-1) = 0, F(-2) = (-1)^(d+1), F(-3) = (-1)^(d+1) – (-2)^d = (-1)^(d+1)(1^d + 2^d) …, and it’s easy to prove that, for any n,

F(n) = (-1)^(d+1)F(-n-1).

This means that if we have a root at -1/2 + a, we also have a root at -1/2 – a = -(-1/2 +a) -1.

Does an academic job in math really suck?

My cousin recently sent me a link to this article about women in science. Actually it’s really about jobs in science, and how much they suck, and how women are too practical to want them. It’s definitely interesting- and pretty widely read, as well, although I’d never seen it. It makes a few excellent points, especially about the crappy amount of money and feedback one gets as an academic, two issues which were definitely part of my personal decision to leave my academic career.

I think his overall argument, though, is simultaneously too practical-minded and not practical-minded enough. And although his essay is about science, I’ll concentrate on how it relates to math.

It’s too practical in that it doesn’t really understand the attraction- the nearly carnal desire- people have to math. It essentially assumes that after some amount of time, maybe 20 years, people will lose interest in their subject, perhaps because they are getting poorly paid.

Is this really true? Maybe for some people this is true, but the nerds I know are nerds for life – they don’t wake up one day thinking math isn’t cool after all. And from what I know about people, they acclimate pretty thoroughly to their standard of living by the time they are 40.

It’s not practical enough, though, because it doesn’t get at one of the most important reasons women leave math, namely because they are married and maybe have kids and they simply can’t be that person who moves across the country for a visiting semester in Berkeley because their husband has a job already and it’s not in Berkeley.

[As a side note, if someone wants to actually encourage women in math, and they are loaded, I would encourage them to set up a fund that would pay costs for quality childcare and airplane tickets for kids when woman go to math conferences. You don’t even need to help organize the babysitting, just pay for it. It would help out a lot of young women and free them up to go to way more conferences, evening the playing field with young men.]

In fact there are plenty of women who are super nerdy and would love to go do math across the country, but when it comes to choosing between that lifestyle and having a family life, they will choose the family life more times than not. Really it’s the “nomadic monk” system itself that is crappy for women at that moment, even if they are theoretically happy to be a poor nerd for the rest of their lives.

I have another complaint (which will make it sound like I don’t like the essay but actually I do). It says that people in science don’t have the ability to switch careers, essentially because they don’t have the money. But that’s really not true, at least in math, and I’m a testament to the possibility of switching careers. One thing a nerd is really good at is learning new things quickly.

I also thought that there was something missing about the alternative jobs he mentions, in industry or otherwise, which is that, yes you do get paid better outside of academics, but on the other hand pretty much any nonacademic job requires you to have a boss, which can be really fine or really horrible, and restricts your vacation time to 3 or 4 weeks. By contrast the quality of life as an academic is, if not luxurious, at least much more under one’s control.

Why “mathbabe”?

Let me tell you a bit about my childhood.

I grew up in Lexington, MA, which is an upper-middle class liberal suburb of Boston. Most of the people I went to school with had parents that either worked at or went to Harvard or M.I.T. – it was a pretty nerdy, intellectual environment. My parents, both computer scientists, moved there for the public schools.

In spite of that, I was a hopeless, pathetic nerd. My idea of fun was practicing classical piano, watching “Amadeus” over and over again, and factoring license plate numbers in my head. When you add to that the facts that I wore glasses, braces, and was chubby, you are talking about one pathetic young nerd girl. When, you top *that* off with the fact that I went through puberty at the wrong time, you can imagine that I went through junior high wondering what everyone was smoking. Oh, and did I mention that my mom hated shopping so I was always wearing one of two bright pink stretch polyester pants? And that my personal hygiene skills were undeveloped? You get the picture.

I was lucky enough to have a best friend starting in 7th grade, who saved me from many pits of despair (although not all). But come high school, my self-esteem was pretty crappy, and the only thing I seemed to be good at, my refuge, was piano and math team.

My parents did an excellent job of not really caring about what I did for the most part, so I wasn’t at all pressured into doing math, and definitely not pressured into doing music. When I came home with an advertisement from a math camp at Hampshire College in western Massachusetts, though, my parents essentially bribed me to go. It didn’t take much convincing, I was intrigued.

Here’s where we get to the title of the post. When I got there, I quickly noticed there were 50 boys and 10 girls. And then I noticed that a bunch of these guys were kind of… cool, they were mostly from places like Stuyvesant and Bronx Science and Evanston, places I’d never heard of but which obviously placed a premium on being a math nerd. Then, this was the miracle, I noticed that these cool, sexy guys, thought I was cool and sexy. OMG, I was a math babe!

It was the first moment I had ever felt like I belonged somewhere, that I was with my peeps. I learned lots of math that first summer, and although most of the specifics kind of wore away over the following year, the feeling that I had a community never did. Actually the one thing I did really learn for good that summer was how to solve the Rubik’s cube using group theory (a subject for another post!). And I distinctly remember carrying around a Rubik’s cube like a piece of platinum my entire junior year of high school, just because it reminded me that I was, in fact, a math babe, at least in one context (although not here! not here whatsoever!).

Which reminds me! This summer, I’m very excited to be going back to the same math camp to teach as a senior staff member. Here’s the list of stuff I have prepared to teach this crop of math studs and math babes:

1) magic squares and generalizations. I just figured out how to generate all 3×3 magic squares! I love those little guys.

2) elementary number theory: fundamental theorem of arithmetic

3) cool geometry stuff like bisectors of angles and sides and all those cool theorems

4) pigeon hole principle, lots of examples

5) euler’s formula and the platonic solids

6) cool stuff with perfect numbers and non-perfect numbers

7) proof by induction, lots of examples

8) basic graph theory

9) bipartite graphs and related theorems.

10) basic ramsey theory

11) more number theory

12) farey fractions

13) continued fractions and the golden ratio

I can’t friggin wait!! Please send me more suggestions if I’m missing something that they really need to know. By the way I’m only teaching the first three weeks, because I couldn’t arrange for the whole 6- the second half they will be learning more specialized subjects from some very cool mathematicians.

Actually there’s another reason I ultimately decided to call this blog “mathbabe,” namely when I googled it, I was first of all offended that the name wasn’t already taken by some other woman math nerd who posting about cool stuff, but what really offended me was that there’s another site with a very similar name which simply shows nearly naked women next to cliff notes on basic math subjects. WTF?!? It is ridiculously obvious to me that math babes should be doing math, not adorning it. So I kind of had to call myself mathbabe after that.

What’s it take to be a woman in math?

One of the first things I’d like to set people straight on is what it takes to be a woman in math. The short answer is, a warrior. The longer answer starts like this. At least in this country, in this culture*, it required near-constant resistance to the niggling feeling that you don’t belong, that you are an outsider, and that you will always be an outsider. It takes the belief in yourself as an abstract thinker, as a scientist, and as a _source_ of wisdom. This is completely counter to how the average woman has been taught to behave: demurely, modestly, quietly. Unleaderly. And the above description refers only to the psychological barriers, not the underlying mathematics.

Considering how difficult the material itself is, it’s not surprising how many women drop out eventually.

To be fair, we are seeing many more women finishing college degrees in mathematics and Ph.D.s in mathematics, and that is frigging awesome. But we are still not seeing that many professors, not in the numbers you might think from the Ph.D. programs. Why is this? I think I can explain this at least in part. When one decides to become a math major, it’s a difficult decision in terms of the surrounding cultural expectations, but there’s very good, very consistent feedback (at least outside of Harvard), namely in the form of homework and test grades from undergrad classes. In other words, it may be a weird decision to be a woman in math, but you can *see* your success whenever your homework comes back with a good grade. It’s proof positive that you are doing ok. To some extent in grad school this feedback loop continues, and with luck you have a good advisor who is encouraging and nurturing. However, once outside of grad school the feedback loop all but vanishes and you are left to decide, *within yourself* whether you are good at what you do. This is when you as a woman (and of course this happens to men too but for whatever reason, maybe just hormones, maybe culture, not as often) question yourself, and then look to the outside world for affirmation, and to be honest that’s a pretty tough moment. Many women leave at that moment.

In some sense I am one of them, because I did leave academics. But I left because I decided I wanted more, so more of a moment of strength than a moment of fear. I got a Ph.D. at Harvard, went to M.I.T. for a post-doc, then became an assistant professor at Barnard College. I got to the point where I was pretty sure I’d be able to get tenure, or in other words to the point that I was sure I deserved tenure, and I looked around and decided, this isn’t the kind of feedback loop I want in my life. I need actual feedback, in real time. I left to be a quant in finance (and since then a data scientist at an internet ad company). I feel very lucky that I could make that decision without fear, and I still consider myself a woman in math, and I still encourage women in math to stay in math or at least stay mathematical.

I think if people understood what women in math need to do in order to just be themselves every day, they would be treated less like anomalies and more like superheroes. It’s a tough thing to do, and they should be respected for it. And they are cool. I mean, what’s cooler than someone who lives as an outsider and has come to terms with that? It’s a strength that not everyone has.

Here’s the thing, I don’t want to end this post on a negative note. In spite of everything I’ve said, being a math babe totally rocks, because math rocks. I hope to convincingly illustrate just how much math rocks in future posts.

* I’ve talked to women outside the US about being mathematicians in their country. One thing that commonly comes up is that in Italy, and to some extent France, it is much more common to see women mathematicians. Why is this? One of my Italian women mathematician friends described it to me like this: in Italy, the academic track to become a mathematician is identical to that of becoming a high school math teacher- indeed the two tracks diverge only after a masters degree. The outcome of this system is that it is not seen as a particularly glamorous or even difficult profession- perhaps similar to that of an engineer. According to her, truly ambitious Italians become politicians, not mathematicians.

Hello world! [stet]

Welcome to my new “mathbabe” blog! I’d like to outline my aspirations for this blog, at least as I see it now.

First, I want to share my experiences as a female mathematician, for the sake of young women wanting to know what things are like as a professional woman mathematician. Second, I want to share my experiences as an academic mathematician and as a quant in finance, and finally as a data scientist in internet advertising. (Wait, did I say finally?)

I also want to share explicit mathematical and statistical techniques that I’ve learned by doing these jobs. For some reason being a quant is treated like a closed guild, and I object to that, because these are powerful techniques that are not that difficult to learn and use.

Next I want to share thoughts and news on subjects such as mathematics and science education, open-source software packages, and anything else I want, since after all this is a blog.

Finally, I want to use this venue to explore new subjects using the techniques I have under my belt, and hopefully develop new ones. I have a few in mind already and I’m really excited by them, and hopefully with time and feedback from readers some progress can be made. I want to primarily focus on things that will actually help people, or at least have the potential to help people, and which lend themselves to quantitative analysis.

Woohoo!