Archive

High frequency trading: how it happened, what’s wrong with it, and what we should do

High frequency trading (HFT) is in the news. Politicians and regulators are thinking of doing something to slow stuff down. The problem is, it’s really complicated to understand it in depth and to add rules in a nuanced way. Instead we have to do something pretty simple and stupid if we want to do anything.

How it happened

In some ways HFT is the inevitable consequence of market forces – one has an advantage when one makes a good decision more quickly, so there was always going to be some pressure to speed up trading, to get that technological edge on the competition.

But there was something more at work here too. The NYSE exchange used to be a non-profit mutual, co-owned by every broker who worked there. When it transformed to a profit-seeking enterprise, and when other exchanges popped up in competition with it was the beginning of the age of HFT.

All of a sudden, to make an extra buck, it made sense to allow someone to be closer and have better access, for a hefty fee. And there was competition among the various exchanges for that excellent access. Eventually this market for exchange access culminated in the concept of co-location, whereby trading firms were allowed to put their trading algorithms on servers in the same room as the servers that executed the trades. This avoids those pesky speed-of-light issues when sitting across the street from the executing servers.

Not surprisingly, this has allowed the execution of trades to get into the mind-splittingly small timeframe of double-digit microseconds. That’s microseconds, where from wikipedia: “One microsecond is to one second as one second is to 11.54 days.”

What’s wrong with it

Turns out, when things get this fast, sometimes mistakes happen. Sometimes errors occur. I’m writing in the third-person passive voice because we are no longer talking directly about human involvement, or even, typically, a single algorithm, but rather the combination of a sea of algorithms which together can do unexpected things.

People know about the so-called “flash crash” and more recently Knight Capital’s trading debacle where an algorithm at opening bell went crazy with orders. But people on the inside, if you point out these events, might counter that “normal people didn’t lose money” at these events. The weirdness was mostly fixed after the fact, and anyway pension funds, which is where most normal people’s money lives, don’t ever trade in the thin opening bell market.

But there’s another, less well known example from September 30th, 2008, when the House rejected the bailout, shorting stocks were illegal, and the Dow dropped 778 points. The prices as such common big-ticket stocks such as Google plummeted and, in this case, pension funds lost big money. It’s true that some transactions were later nulled, but not all of them.

This happened because the market makers of the time had largely pulled their models out of the market after shorting became illegal – there was no “do this algorithm except make sure you’re never short” button on the algorithm, so once the rule was called, the traders could only turn it all of completely. As a result, the liquidity wasn’t there and the pension funds, thinking they were being smart to do their big trades at close, instead got completely walloped.

Keep this in mind, before you go blaming the politicians on this one because the immediate cause was the short-sighted short-selling ban: the HFT firms regularly pull out of the market in times of stress, or when they’re updating their algorithms, or just whenever they want. In other words, it’s liquidity when you need it least.

Moreover, just because two out of three times were relatively benign for the 99%, we should not conclude that there’s nothing potentially disastrous going on. The flash crash and Knight Capital have had impact, namely they serve as events which erode our trust in the system as a whole. The 2008 episode on top of that proved that yes, we can be the victims of the out-of-control machines fighting against each other.

Quite aside from the instability of the system, and how regular people get screwed by insiders (because after all, that’s not a new story at all, it’s just a new technology for an old story), let’s talk about resources. How much money and resources are being put into the HFT arena and how could those resources otherwise be used?

Putting aside the actual energy consumed by the industry, which is certainly non-trivial, let’s focus for a moment on money. It has been estimated that overall, HFT firms post about $80 billion in profits yearly, and that they make on the order of 10% profit on their technology investments. That would mean that there’s in the order of $800 billion being invested in HFT each year. Even if we highball the return at 25%, we still have more than $300 billion invested in this stuff.

And to what end?

Is that how much it’s really worth the small investor to have decreased bid-ask spreads when they go long Apple because they think the new iPhone will sell? What else could we be doing with $800 billion dollars? A couple of years of this could sell off all of the student debt in this country.

What should be done

Germany has recently announced a half-second minimum for posting an share order. This is eons in current time frames, and would drastically change how trading is done. They also want HFT algorithms to be registered with them. You know, so people can keep tabs on the algorithms and understand what they’re doing and how they might interact with each other.

Um, what? As a former quant, let me just say: this will not work. Not a chance in hell. If I want to obfuscate the actual goals of a model I’ve written, that’s easier than actually explaining it. Moreover, the half-second rule may sound good but it just means it’s a harder system to game, not that it won’t be gameable.

Other ideas have been brought forth as to how to slow down trading, but in the end it’s really hard to do: if you put in delays, there’s always going to be an algorithm employed which decides whose trade actually happens first, and so there will always be some advantage to speed, or to gaming the algorithm. It would be interesting but academically challenging to come up with a simple enough rule that would actually discourage people from engaging in technological warfare.

The only sure-fire way to make people think harder about trading so quickly and so often is a simple tax on transactions, often referred to as a Tobin Tax. This would make people have sufficient amount of faith in their trade to pay the tax on top of the expected value of the trade.

And we can’t just implement such a tax on one market, like they do for equities in London. It has to be on all exhange-traded markets, and moreover all reasonable markets should be exchange-traded.

Oh, and while I’m smoking crack, let me also say that when exchanges are found to have given certain of their customers better access to prices, the punishments for such illegal insider information should be more than $5 million dollars.

Telling people to leave finance

I used to work in finance, and now I don’t. I haven’t regretted leaving for a moment, even when I’ve been unemployed and confused about what to do next.

Lots of my friends that I made in finance are still there, though, and a majority of them are miserable. They feel trapped and they feel like they have few options. And they’re addicted to the cash flow and often have families to support, or a way of life.

It helps that my husband has a steady job, but it’s not only that I’m married to a man with tenure that I’m different. First, we have three kids so I actually do have to work, and second, there are opportunities to leave that these people just don’t consider.

First, I want to say it’s frustrating how risk-averse the culture in finance is. I know, it’s strange to hear that, but compared to working in a start-up, I found the culture and people in finance to be way more risk-averse in the sense of personal risk, not in the sense of “putting other people’s money at risk”.

People in start-ups are optimistic about the future, ready for the big pay-out that may never come, whereas the people in finance are ready for the world to melt down and are trying to collect enough food before it happens. I don’t know which is more accurate but it’s definitely more fun to be around optimists. Young people get old quickly in finance.

Second the money is just crazy. People seriously get caught up in a world where they can’t see themselves accepting less than $400K per year. I don’t think they could wean themselves off the finance teat unless the milk dried up.

So I was interested in this article from Reuters which was focused on lowering bankers’ bonuses and telling people to leave if they aren’t happy about it.

On the one hand, as a commenter points out, giving out smaller bonuses won’t magically fix the banks- they are taking massive risks, at least at the too-big-to-fail banks, because there is no personal risk to themselves, and the taxpayer has their back. On the other hand, if we take away the incentive to take huge risks, then I do think we’d see way less of it.

Just as a thought experiment, what would happen if the bonuses at banks really went way down? Let’s say nobody earns more than $250K, just as a stab in the arm of reality.

First, some people would leave for the few places that are willing to pay a lot more, so hedge funds and other small players with big money. To some extent this has already been happening.

Second, some people would just stay in a much-less-exciting job. Actually, there are plenty of people who have boring jobs already in these banks, and who don’t make huge money, so it wouldn’t be different for them.

Finally, a bunch of people would leave finance and find something else to do. Their drug dealer of choice would be gone. After some weeks or months of detox and withdrawal, they’d learn to translate their salesmanship and computer skills into other industries.

I’m not too worried that they’d not find jobs, because these men and women are generally very smart and competent. In fact, some of them are downright brilliant and might go on to help solve some important problems or build important technology. There’s like an army of engineers in finance that could be putting their skills to use with actual innovation rather than so-called financial innovation.

Emanuel Derman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua

Why, if I’m so aware of the powers and dangers of modeling, do I still earn my living doing mathematical modeling? How am I to explain myself?

It’s not an easy question, and I’m happy to see that my friend Emanuel Derman has addressed this a couple of weeks ago in an essay published by the Journal of Derivatives, of all places (h/t Chris Wiggins). Its title is Apologia Pro Vita Sua, which means “in defense of one’s life.” Please read it – as usual, Derman has a beautiful way with words.

Before going into the details of his reasoning, I’d like to say that any honest attempt at trying to answer this question by someone intrigues and attracts me to them – what is more threatening and interesting that examining your life for its flaws? Never mind publishing it for all to see and to critique.

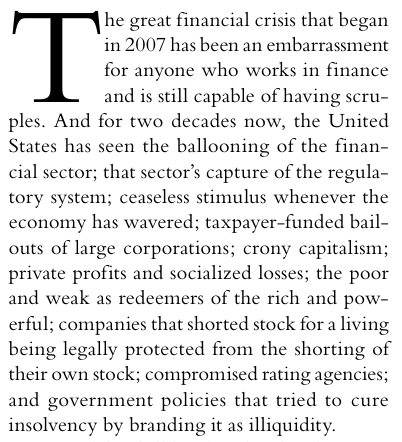

Emanuel starts his essay by listing off the current flaws in finance better than any Occupier I’ve ever met:

After giving some background about himself and setting up the above question of justifying oneself as a modeler, Derman reveals himself to be a Blakean, by which he means that “part of our job on earth is to perceptively reveal the way the world really works”.

And how does the world work? According to Norman Mailer, anyway, it’s an enormous ego contest – we humans struggle to compete and to be seen as writers, scientists, and, evidently, financial engineers.

It’s not completely spelled out but I understand his drift to be that the corruption and crony capitalism we are seeing around us in the financial system is understandable from that perspective – possibly even obvious. As an individual player inside this system, I naturally compete in various ways with the people around me, to try to win, however I define that word.

On the one hand you can think of the above argument as weak, along the lines of “because everybody else is doing it.” On the other hand, you could also frame it as understanding the inevitable consequences of having a system which allows for corruption, which has built-in bad incentives.

From this perspective you can’t simply ask people not to be assholes or not to use lobbyists to get laws passed for their benefit. You need to actually change the incentive system itself.

Derman’s second line of defense is that the current system isn’t ideal but he uses his experience to carefully explain the dangers of modeling to his students, thereby training a generation not to trust too deeply in the idea of financial engineering as a science:

Unfortunately, no matter what academics, economists, or banks tell you, there is no truly reliable financial science beneath financial engineering. By using variables such as volatility and liquidity that are crude but quantitative proxies for complex human behaviors, financial models attempt to describe the ripples on a vast and ill-understood sea of ephemeral human passions. Such models are roughly reliable only as long as the sea stays calm. When it does not, when crowds panic, anything can happen.

Finally, he quotes the Modelers’ Hippocratic Oath, which I have blogged about multiple times and I still love:

Although I agree that people are by nature tunnel visioned when it comes to success and that we need to set up good systems with appropriate incentives, I personally justify my career more along the lines of Derman’s second argument.

Namely, I want there to be someone present in the world of mathematical modeling that can represent the skeptic, that can be on-hand to remind people that it’s important to consider the repercussions of how we set up a given model and how we use its results, especially if it touches a massive number of people and has a large effect on their lives.

If everyone like me leaves, because they don’t want to get their hands dirty worrying about how the models are wielded, then all we’d have left are people who don’t think about these things or don’t care about these things.

Plus I’m a huge nerd and I like technical challenges and problem solving. That’s along the lines of “I do it because it’s fun and it pays the rent,” probably not philosophically convincing but in reality pretty important.

A few days ago I was interviewed by a Japanese newspaper about my work with Occupy. One of the questions they asked me is if I’d ever work in finance again. My answer was, I don’t know. It depends on what my job would be and how my work would be used.

After all, I don’t think finance should go away entirely, I just want it to be set up well so it works, it acts as a service for people in the world; I’d like to see finance add value rather than extract. I could imagine working in finance (although I can’t imagine anyone hiring me) if my job were to model value to people struggling to save for their retirement, for example.

This vision is very much in line with Derman’s Postscript where he describes what he wants to see:

Finance, or at least the core of it, is regarded as an essential service, like the police, the courts, and

the firemen, and is regulated and compensated appropriately. Corporations, whose purpose is relatively straightforward, should be more constrained than individuals, who are mysterious with possibility.

People should be treated as adults, free to take risks and bound to suffer the consequent benefits and disadvantages. As the late Anna Schwartz wrote in a 2008 interview about the Fed, “Everything works much better when wrong decisions are punished and good decisions make you rich.”

No one should have golden parachutes, but everyone should have tin ones.

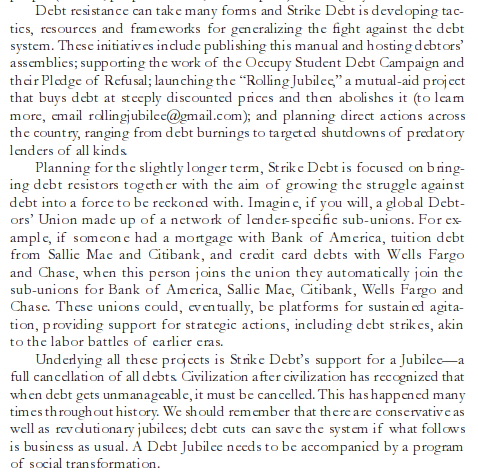

The Debt Resistors’ Operation Manual

A newer group grown out of Occupy called Strike Debt is making waves with their newly released Debt Resistors’ Operation Manual, available to read here with commentary from Naked Capitalism’s Yves Smith and available for download as a pdf here.

Their goal is compelling, and they state it in their manifesto on page 2:

We gave the banks the power to create money because they promised to use it to help us live healthier and more prosperous lives—not to turn us into frightened peons. They broke that promise. We are under no moral obligation to keep our promises to liars and thieves. In fact, we are morally obligated to find a way to stop this system rather than continuing to perpetuate it.

This collective act of resistance may be the only way of salvaging democracy because the campaign to plunge the world into debt is a calculated attack on the very possibility of democracy. It is an assault on our homes, our families, our communities and on the planet’s fragile ecosystems—all of which are being destroyed by endless production to pay back creditors who have done nothing to earn the wealth they demand we make for them.

To the financial establishment of the world, we have only one thing to say: We owe you nothing. To our friends, our families, our communities, to humanity and to the natural world that makes our lives possible, we owe you everything. Every dollar we take from a fraudulent subprime mortgage speculator, every dollar we withhold from the collection agency is a tiny piece of our own lives and freedom that we can give back to our communities, to those we love and we respect. These are acts of debt resistance, which come in many other forms as well: fighting for free education and healthcare, defending a foreclosed home, demanding higher wages and providing mutual aid.

Here’s what I love about this manual and this Occupy group:

- They position the current debt and money situation as a system that is changeable and that, if it isn’t working for the 99%, should be changed. Too often people assume that nothing can be done.

- They explain things about debt, credit scores, and legal rights in plain English.

- They give real advice to people with different kinds of problems. For example, here’s an excerpt for people battling a mistake in their credit report:

- They also give advice on: understanding your medical bills, disputing incorrect bills, negotiating with credit card companies, and fighting for universal health care.

- They give background on why there’s so much student debt and mortgage debt and what the consequences of default are or could be.

- They talk about odious municipal debt, and give some background on that seedy side of finance.

- They describe predatory services for the underbanked like check-cashing services and payday lenders – they also explain in detail how to default on payday loans.

- They explain pre-paid debit cards and their possibilities.

- They talk about debt collectors and what you need to know to deal with them.

- They explain the ways to declare bankruptcy and the consequences of bankruptcy.

They explicitly create solidarity with all kinds of debtors with this conclusion:

The threat of large-scale debt resistance is a great idea for putting pressure on the creditors to at least negotiate reasonably, as they already negotiate when large companies want to. It basically levels the playing field that already exists, i.e. addresses the double standards we have with respect to debt when we compare corporations to people (see my posts here and here for example).

In spite of this potential power in debt resistance, I have historically had reservations about the idea of asking a bunch of people, especially young people, to default on their debt, because I’m concerned for them individually – the banks, debt collection agencies, and other creditors have all the power in this situation – see this New York Times article from this morning if you don’t believe that.

Here’s the thing though: this manual does an exceptional job of educating people about the actual consequences of default, so they can understand what their options are and what they’d be getting into if they join a resistance movement. It’s actual information, written for struggling people, the very people who need this advice.

Thank you, Strike Debt, we needed this. I’m going to try to make it tomorrow morning for the protest.

How is math used outside academia?

Help me out, beloved readers. Brainstorm with me.

I’m giving two talks this semester on how math is used outside academia, for math audiences. One is going to be at the AGNES conference and another will be a math colloquium at Stonybrook.

I want to give actual examples, with fully defined models, where I can explain the data, the purported goal, the underlying assumptions, the actual outputs, the political context, and the reach of each model.

The cool thing about these talks is I don’t need to dumb down the math at all, obviously, so I can be quite detailed in certain respects, but I don’t want to assume my audience knows the context at all, especially the politics of the situation.

So far I have examples from finance, internet advertising, and educational testing. Please tell me if you have some more great examples, I want this talk to be awesome.

The ultimate goal of this project is probably an up-to-date essay, modeled after this one, which you should read. Published in the Notices of the AMS in January 2003, author Mary Poovey explains how mathematical models are used and abused in finance and accounting, how Enron booked future profits as current earnings and how they manipulated the energy market. From the essay:

Thus far the role that mathematics has played in these financial instruments has been as much inspirational as practical: people tend to believe that numbers embody objectivity even when they do not see (or understand) the calculations by which particular numbers are generated. In my final example, mathematical principles are still invisible to the vast majority of investors, but mathematical equations become the prime movers of value. The belief that makes it possible for mathematics to generate value is not simply that numbers are objective but that the market actually obeys mathematical rules. The instruments that embody this belief are futures options or, in their most arcane form, derivatives.

Slightly further on she explains:

In 1973 two economists produced a set of equations, the Black-Scholes equations, that provided the first strictly quantitative instrument for calculating the prices of options in which the determining variable is the volatility of the underlying asset. These equations enabled analysts to standardize the pricing of derivatives in exclusively quantitative terms. From this point it was no longer necessary for traders to evaluate individual stocks by predicting the probable rates of profit, estimating public demand for a particular commodity, or subjectively getting a feel for the market. Instead, a futures trader could engage in trades driven purely by mathematical equations and selected by a software program.

She ends with a bunch of great questions. Mind you, this was in 2003, before the credit crisis:

But what if markets are too complex for mathematical models? What if irrational and completely unprecedented events do occur, and when they do—as we know they do—what if they affect markets in ways that no mathematical model can predict? What if the regularity that all mathematical models assume effaces social and cultural variables that are not subject to mathematical analysis? Or what if the mathematical models traders use to price futures actually influence the future in ways the models cannot predict and the analysts cannot govern? Perhaps these are the only questions that can challenge the financial axis of power, which otherwise threatens to remake everything, including value, over in the image of its own abstractions. Perhaps these are the kinds of questions that mathematicians and humanists, working together, should ask and try to answer.

Citigroup’s plutonomy memos

Maybe I’m the last person who’s hearing about the Citigroup “plutonomy memos”, but they’re blowning me away.

Wait, now that I look around, I see that Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism posted about this on October 15, 2009, almost three years ago, and called for people to protest the annual meetings of the American Bankers Association. Man, that’s awesome.

So yeah, I’m a bit late.

But just in case you didn’t hear about the plutonomy memos (h/t Nicholas Levis), which were featured on Michael Moore’s “Capitalism: a Love Story” as well, then you’ll have to read this post immediately and watch Bill Moyer’s clip at the end as well.

The basic story, if you’re still here, is that certain “global strategists” inside Citigroup drafted some advice about investing based on their observation that rich people have all the money and power. They even invented a new word for this, namely “plutonomy.” This excerpt from one of the three memos kind of sums it up:

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization… Since we think the plutonomy is here, is going to get stronger… It is a good time to switch out of stocks that sell to the masses and back to the plutonomy basket.

The lawyers for Citigroup keep trying to make people take down the memos, but they’re easy to find once you know to look for them. Just google it.

Nothing that surprising, economically speaking, except for maybe the fact that their reaction, far from being outrage, is something bordering on gleeful. But they aren’t totally complacent:

Low-end developed market labor might not have much economic power, but it does have equal voting power with the rich.

This equal voting power seems to be a pretty serious concern for their plans. They go on to say:

A third threat comes from the potential social backlash. To use Rawls-ian analysis, the invisible hand stops working. Perhaps one reason that societies allow plutonomy, is because enough of the electorate believe they have a chance of becoming a Pluto-participant. Why kill it off, if you can join it? In a sense this is the embodiment of the “American dream”. But if voters feel they cannot participate, they are more likely to divide up the wealth pie, rather than aspire to being truly rich.

Could the plutonomies die because the dream is dead, because enough of society does not believe they can participate? The answer is of course yes. But we suspect this is a threat more clearly felt during recessions, and periods of falling wealth, than when average citizens feel that they are better off. There are signs around the world that society is unhappy with plutonomy – judging by how tight electoral races are.

But as yet, there seems little political fight being born out on this battleground.

This explains to me why Occupy was treated the way it was by Bloomberg’s cops and the entrenched media like the New York Times (and nationally) – the idea that people are opting out and no longer believe they have a chance of being a Pluto-participant is essentially the most threatening thing they can think of. Interestingly, they also say this:

A related threat comes from the backlash to “Robber-barron” economies. The

population at large might still endorse the concept of plutonomy but feel they have lost out to unfair rules. In a sense, this backlash has been epitomized by the media coverage and actual prosecution of high-profile ex-CEOs who presided over financial misappropriation. This “backlash” seems to be something that comes with bull markets and their subsequent collapse. To this end, the cleaning up of business practice, by high-profile champions of fair play, might actually prolong plutonomy.

This is what Dodd-Frank has done, to some extent: a law that makes things seem like they’re getting better, or at least confuses people long enough so they lose their fighting spirit.

Finally, from the third memo:

➤ What could go wrong?

Beyond war, inflation, the end of the technology/productivity wave, and financial collapse, we think the most potent and short-term threat would be societies demanding a more ‘equitable’ share of wealth.

Note the perspective: what could go wrong. Lest we wonder who inititated class warfare.

#OWS update

I’m happy to show you that Alternative Banking now has a working blog, thanks to a newer member Nicholas Levis. He blogged recently about a Reality Sandwich event I went to last Wednesday, where David Graeber, author of Debt: the first 5000 years was speaking. Interesting and stimulating.

We also have a playing card project called “52 Shades of Greed” which is coming out soon. Check out some of the amazing art here.

Finally, we are about to launch a Kickstarter campaign for our “move your money” app, as soon as I figure out how to accept the money without doing something illegal. Please tell me if you have experience with such things!

More exciting things in the works which I can’t talk about yet. I’ll keep you updated.

Someone didn’t get the memo about regulatory capture

So there’s this guy named Benjamin Lawsky, and he’s the New York State Superintendent of Financial Services. Last week he blew open a case against a British bank named Standard Chartered for money laundering and doing business with Iran.

The other regulators don’t like his style one bit, even though he managed to force Standard Chartered to pay $340 million for their misdeeds, as well as look like bad guys. I’ll get back to why the other regulators are pissed but first a bit more on the settlement.

What’s not cool about a fine is that nobody goes to jail and they continue business as usual, hopefully without the money laundering (their stock has mostly recovered as well).

What is cool about the $340 million fine is that it took almost no time compared to other settlements with banks (a nine month investigation before the blowup last week) and that it’s actually pretty big – bigger, for example, then the proposed settlement SEC is making with Citigroup which judge Rackoff blocked for shorting their clients in 2008 and not admitting wrongdoing.

In this case of Standard Chartered, they may not be admitting wrongdoing but we’ve all already read the evidence, as well as the smoking gun email:

The business chugged along even after the banking unit’s chief executive in the Americas warned in a 2006 memo that the company and its management might be vulnerable to “catastrophic reputational damage” and “serious criminal liability.”

According to the regulatory order, a bank official in London replied: “You f- Americans. Who are you to tell us, the rest of the world, that we’re not going to deal with Iranians.”

[Aside: do you think, being a polite Brit, that this guy actually wrote “f-” in his email?]

Back to the other regulators. They are so used to working for the banks, it is inconceivable to them to publicize damning evidence before giving the heads up to the bank in question looking for a quiet settlement. That’s the way they do things. And then they never get much money, and nobody ever goes to jail. Oh, and it takes forever.

They argue that this is because they don’t have enough resources to go the distance with lawyers, but it’s also because their approach is so weak.

So naturally they’ve been pretty upset that Lawsky has balls when they don’t, especially since he doesn’t have nearly the resources that the SEC has.

My favorite ridiculous argument against Lawsky and his approach came from this article I read yesterday on Reuters. It stipulates that Lawsky is creating an environment where there’s a possibility of regulatory arbitrage. From the article:

But a central lesson of the financial crisis was the need for regulators to better cooperate and share information. Working at cross purposes creates opportunities for what’s known as “regulatory arbitrage,” whereby banks circumvent regulations by exploiting rivalries among their various overseers.

Um, what? That whole mindset is clearly off.

The goal would be the regulators get to decide who’s the bad guy, not the banks. And don’t tell me loopholes in the regulatory structure are introduced by having a regulator willing to do his job without sucking everybody’s dick first. Please.

And if I’m a regulator, and if it would work better to share my information with Lawsky to do my job as a regulator, you better believe I’m willing to share it with him if I can get credit alongside him for exposing illegal activities. That is, if I really want to expose illegal activities.

The U.S. Treasury is a bad baby daddy

It occurs to me, when reading Treasury’s latest excuse for the unbelievably shitty performance of HAMP, that Treasury has been a really crappy baby daddy. From a recent New York Times article (also see this):

Mr. Summers declined to comment on the record, but other current and former officials echoed Mr. Geithner’s view that the administration had done well under the circumstances. Some said they underestimated the complexity of helping millions of people. Some said they tried too hard at first to protect taxpayers from unnecessary losses. But they agreed that the most important problem was beyond their control: the mortgage industry was set up either to collect payments or to foreclose, and it was not ready to help people.

“They were bad at their jobs to start with, and they had just gone through this process where they fired lots of people,” said Michael S. Barr, a former assistant Treasury secretary who served as Mr. Geithner’s chief housing aide in 2009 and 2010. “The only surprise was that they were even more screwed up than the high level of screwiness that we expected.”

I mean, let’s say I have a whining teenager who I’ve just realized has stolen my money, signed my name to various notes to the principal, and has been playing hooky for months or even years. I might not ask that same kid to help his friends with their college applications unsupervised.

I might think he needs to be watched, and that I’d keep in mind the selfishness and immaturity that he’s already exposed as I watch him, to make sure he doesn’t end up plagiarizing his best friends’ college essay, or steal the application fees, or something else I hadn’t even thought of.

What I wouldn’t worry about is the possibility that he’s not smart enough to help his friends – he’s already shown me how manipulative and clever he can be when it benefits him.

Moreover, if I didn’t supervise that kid, then after none of his friends get into college I’d blame myself, and not the kid, for my failing. Because he’s only a kid, and I’m supposed to be the grownup. I’d be a bad baby daddy.

That’s what Treasury is doing. Those guys knew better than to trust the banks with something like HAMP, which was essentially unsupervised and had too many conflicting incentives for the banks to ever be expected to actually help people in trouble with their mortgage. They set it up terribly, looked the other way when the banks did nothing (and as Barofsky explained to us, this was intentional – they were foaming the runway for the banks to recover), and now they’re trying to say it’s because the banks were screwed up.

Not good enough, Treasury.

Looterism

My friend Nik recently sent me a PandoDaily article written by Francisco Dao entitled Looterism: The Cancerous Ethos That Is Gutting America.

He defines looterism as the “deification of pure greed” and says:

The danger of looterism, of focusing only on maximizing self interest above the importance of creating value, is that it incentivizes the extraction of wealth without regard to the creation or replenishment of the value building mechanism.

I like the term, I think I’ll use it. And it made me think of this recent Bloomberg article about private equity and hedge funds getting into the public schools space. From the article:

Indeed, investors of all stripes are beginning to sense big profit potential in public education.

The K-12 market is tantalizingly huge: The U.S. spends more than $500 billion a year to educate kids from ages five through 18. The entire education sector, including college and mid-career training, represents nearly 9 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, more than the energy or technology sectors.

Traditionally, public education has been a tough market for private firms to break into — fraught with politics, tangled in bureaucracy and fragmented into tens of thousands of individual schools and school districts from coast to coast.

Now investors are signaling optimism that a golden moment has arrived. They’re pouring private equity and venture capital into scores of companies that aim to profit by taking over broad swaths of public education.

The conference last week at the University Club, billed as a how-to on “private equity investing in for-profit education companies,” drew a full house of about 100.

[I think I know why that golden moment arrived, by the way. The obsession with test scores, a direct result of No Child Left Behind, is both pseudo-quantitative (by which I mean it is quantitative but is only measuring certain critical things and entirely misses other critical things) and has broken the backs of unions. Hedge funds and PE firms love quantitative things, and they don’t really care if they numbers are meaningful if they can meaningfully profit.]

Their immediate goal is out-sourcing: they want to create the Blackwater (now Academi) of education, but with cute names like Schoology and DreamBox.

Lest you worry that their focus will be on the wrong things, they point out that if you make kids drill math through DreamBox “heavily” for 16 weeks, they score 2.3 points higher in a standardized test, although they didn’t say if that was out of 800 or 20. Never mind that “heavily” also isn’t defined, but it seems safe to say from context that it’s at least 2 hours a day. So if you do that for 16 weeks, those 2.3 points better be pretty meaningful.

So either the private equity guys and hedge funders have the whole child in mind here, or it’s maybe looterism. I’m thinking looterism.

High frequency trading: does it hurt the little guy?

I’ve already written about high frequency trading here, and I came out in favor of a transaction tax to slow that shit down a little bit. After all, the argument that liquidity is good so more liquidity is better only holds to a point – we don’t need infinite liquidity. It makes sense to actually have a small barrier to trade – you actually have to think it’s a good idea one way or another, otherwise you have no incentive not to do something dumb.

And as we’ve seen recently with Knight Capital, dumb things definitely are likely to happen.

It’s been interesting to see the media reaction. On the one hand, the Room for Debate over at the New York Times has a bunch of people discussing high frequency trading (HFT), and the most pro-HFT guy essentially says that the SEC should keep up technology-wise with these guys, and everything will be ok. That’s called living in a fantasy world.

More interesting to me was Felix Salmon’s post yesterday, where he rightly complained that, all too often, journalists dumb down and simplify reporting on these things, and then he proceeds to dumb down and simplify reporting on this thing.

Specifically, he complains that no “little guys” were hurt in Knight’s crash, even though the press is always looking for the little guy that gets hurt. [Side note: he also complains about the LIBOR manipulation not hurting municipalities, which is false, it did hurt them. He needs to understand that better before he dismisses it.]

But, if I’m not dreaming, Fidelity was one of the large customers of Knight that’s pulled out, and if I’m not unconscious, Fidelity manages quite a few of my many 401K accounts, as well as a huge proportion of the 401K accounts in this country. So it’s quite possible that my retirement money was part of that massive screw-up which is now owned by Goldman Sachs, not that I’ve been notified by Fidelity of any harm (but that’s another post).

As for small investors vs. little guys, there’s a difference. If you have enough money that you’re investing it through brokers, I personally don’t count you as small, even if you appear small to Goldman Sachs. So I’m not interested in whether the small investor was all that harmed by Knight’s meltdown, but I’m pretty sure the small investor was scared away by it.

But looking at the larger picture, I’d definitely say this is an indication of the outrageous complexity of the financial system, which most definitely is hurting the little guy, i.e. the taxpayer. This complexity is why we have the government guarantee in place, the Too-Big-and-Too-Complex-To-Fail banks and markets, and the little guy on the hook when things melt down. Moreover, there’s a direct line from that whole mess to the destruction of unions and pension programs, even if people don’t want to draw it.

So if you want to be myopic you can say that this was one firm, making one major blunder, and it’s self-contained and that firm is failing just like it should. But if you take a step back you see they were doing this as part of a larger culture of competition for speed and technology that they are so focused on, they threw risk to the wind in order to achieve a tiny edge over NYSE.

That laser focus on having a tiny edge really is the underlying story, and will continue to be, at the expense of risk, at the expense of our retirement funds trading for us, without regard to unnecessary complexity or, yes, the little guy, until our politicians and regulators grow some balls and put an end to it.

Bailout, the book

You know that feeling, where you feel like a conspiracy theorist because, even though you don’t have cold hard evidence for it, you have a distinct feeling that someone is trying to thwart you even though they claim to be your friend, or thwart an idea they claim to believe in, or even worse, thwart a principle they claim to stand by?

That’s how I was feeling about Tim Geithner, and frankly the entire Obama administration, until I read “Bailout,” the recently published tell-all book by Neil Barofsky, who was put in charge of detecting and preventing fraud related to TARP.

I recently blogged about how I consider this book a call to Occupy, but I had only read the excerpt from Bloomberg at that point. Now that I’ve read the book, it’s most definitely a call to Occupy, as well as to any group or individual who still has principles and enough energy up to summon outrage.

Going back to the feeling of being a conspiracy theorist.

Nothing in this book was really new to me or really surprised me, except the fact that Barofsky was willing to write it down in black and white. Thank goodness there are still a few people who still have principles, even inside Washington.

Everything there was something I’d pieced together either working in finance, where I lost faith in the Obama administration right away when it introduced HAMP, which was clearly set up to fail homeowners, or by meeting people in the Alternative Banking group of #OWS, specifically Yves Smith, who explained the technical details of the more recent mortgage settlement, and how it is a backdoor bailout to the banks. Yet another one!

Where was the corresponding bailout for the people? Why this doublespeak, where we’d talk about moral hazard for people who have been screwed by the predatory loan industry, but the moral hazard for AIG executives getting multi-million dollar bonuses after an $85 billion bailout is just something we have to swallow, out of deference to the sanctity of contract?

And if we care so much about contracts, why do we allow companies to enter bankruptcy just to jettison pension promises but we don’t allow individuals (who are not too-big-to-fail) to renegotiate crippling student debt loads?

I’m confused no longer. It was never Geithner’s intention, or Obama’s intention, to help out the people. It has always been their intention solely to prop up a failed banking system. What they’ve been doing, rather than saying, is much more consistent with this theory anyway. Lots of roundabout efforts to explain why they’d set up a mortgage modification system to help homeowners was completely ineffective; it’s because it was actually set up to slow down foreclosures in order to “foam the runway” for banks to get back into the black. That makes much more sense!

It actually restores my faith in the Obama administration a bit. Before this I was sometimes torn between thinking they were bought by the banks or they were utterly incompetent. But now I know they aren’t entirely incompetent in the follow-through with their goals: they actually did succeed in slavishly working for the banks in the name of helping out homeowners.

Thank you, Neil Barofsky, for a great book. Thank you for maintaining your justified anger and for being courageous enough, and enough of a dick, to write it.

Why is LIBOR such a big deal? (#OWS)

The manipulation of LIBOR interest rates by the big, mostly-European banks (but not entirely, see a full list here) was an open secret inside finance in 2008. As in so open that I didn’t think of it as a secret at all.

The fact that that manipulation is now consistently creating huge headlines is interesting to me – it brings up a few issues.

- People seem surprised this out-and-out manipulation was happening. That says to me that they clearly still don’t understand what the culture of finance is really like. The fact that Bob Diamond of Barclays claims to have felt “physically ill” when he saw the emails of the traders manipulating LIBOR is either an out-and-out lie or they guy is simple-minded, as in stupid. And word on the street is he’s not stupid.

- People still buy the line that most of the problems from the credit crisis arose from legal but wrong-headed efforts to make money, plus corrupt ratings on mortgage-backed securities. This is incredible to me. Let’s get it clear: the culture of finance is to take advantage of every opportunity to juice your bottom line, even if it’s wrong, even if it’s fraudulent, even if it affects the terms of loans on millions of houses and towns in other countries, and even if only your trading desk is benefiting.

- The LIBOR manipulation in 2008 was about more than that, namely trying not to look as bad as other banks, to avoid being the next Lehman. It was done in the name of not looking weak and requiring a government bailout. Bob Diamond still doesn’t think they did anything wrong by lying there. It was almost like they were doing something noble.

- Speaking of towns in other countries, read this article about how LIBOR manipulation has screwed U.S. cities to the ground. I’ve got a lot more to say about municipal debt and how that sleazy system works but it’s waiting for another post.

- Finally, why did it take so long for the media to pick up on LIBOR manipulation? It tempts me to make a list of the illegal stuff that we all knew about back then and send it around just to make sure.

Is open data a good thing?

As much as I like the idea of data being open and free, it’s not an open and shut case. As it were.

I’m first going to argue against open data with three examples.

The first is a pretty commonly discussed concern of privacy. Simply put, there is no such thing as anonymized data, and people who say there is are either lying or being naive. The amount of information you’d need to remove to really anonymize data is not known to be different from the amount of data you have in the first place. So if you did a good job to anonymize a data set, you’d probably remove all interesting information anyway. Of course, you could think this is only important with respect to individual data.

But my next example comes from land data, specifically Tamil Nadu in Southern India. There’s an interesting Crooked Timber blogpost here (hat tip Suresh Naidu) explaining how “open data” has screwed a local population, the Dalits. Although you could (and I would) argue that the way the data is collected and disseminated, and the fact that the courts go along with this process, is itself politically motivated and disenfrachising, there are some important point made in this post:

Open data undermines the power of those who benefit from “the idiosyncracies and complexities of communities… Local residents [who] understand the complexity of their community due to prolonged exposure.” The Bhoomi land records program is an example of this: it explicitly devalues informal knowledge of particular places and histories, making it legally irrelevant; in the brave new world of open data such knowledge is trumped by the ability to make effective queries of the “open” land records.15 The valuing of technological facility over idiosyncratic and informal knowledge is baked right in to open data efforts.

The Crooked Timber blog post specifically called out Tim O’Reilly and his “Government as Platform” project as troublesome:

The faith in markets sometimes goes further among open data advocates. It’s not just that open data can create new markets, there is a substantial portion of the push for open data that is explicitly seeking to create new markets as an alternative to providing government services.

It’s interesting to see O’Reilly’s Mike Loukides’s reaction (hat tip Chris Wiggins), entitled the Dark Side of Data, here. From Loukides:

The issue is how data is used. If the wealthy can manipulate legislators to wipe out generations of records and folk knowledge as “inaccurate,” then there’s a problem. A group like DataKind could go in and figure out a way to codify that older generation of knowledge. Then at least, if that isn’t acceptable to the government, it would be clear that the problem lies in political manipulation, not in the data itself. And note that a government could wipe out generations of “inaccurate records” without any requirement that the new records be open. In years past the monied classes would have just taken what they wanted, with the government’s support. The availability of open data gives a plausible pretext, but it’s certainly not a prerequisite (nor should it be blamed) for manipulation by the 0.1%.

[Speaking of DataKind (formerly Data Without Borders), it’s also a problem, as I discovered as a data ambassador working with the NYCLU on Stop, Question and Frisk data, when the government claims to be open but withholds essential data such as crime reports.]

My final example comes from finance. On the one hand I want total transparency of the markets, because it sickens me to think about how nobody knows the actual price of bonds, or the correct interest rate, or the current default assumption of the market, how all of that stuff is being kept secret by Wall Street insiders so they can each skim off their little cut and the dumb money players get constantly screwed.

But on the other hand, if I imagine a world where everything really is transparent, then even in the best of all database situations, that’s just asstons of data which only the very very richest and most technologically savvy high finance types could ever munge through.

So who would benefit? I’d say, for some time, the average dumb money customer would benefit very slightly, by not paying extra fees, but that the edgy techno finance firms would benefit fantastically. Then, I imagine, new ways would be invented for the dumb money customers to lost that small amount of benefit altogether, probably by just inundating them with so much data they can’t absorb it.

In other words, open data is great for the people who have the tools to use it for their benefit, usually to exploit other people and opportunities. It’s not clearly great for people who don’t have those tools.

But before I conclude that data shouldn’t be open, let me strike an optimistic (for me) tone.

The tools for the rest of us are being built right now. I’m not saying that the non-exploiters will ever catch up with the Goldman Sachs and credit card companies, because probably not.

But there will be real tools (already are things like python and R, and they’re getting better every day), built out of the open software movement, that will help specific people analyze and understand specific things, and there are platforms like wordpress and twitter that will allow those things to be broadcast, which will have real impact when the truth gets out. An example is the Crooked Timber blog post above.

So yes, open data is not an unalloyed good. It needs to be a war waged by people with common sense and decency against those who would only use it for profit and exploitation. I can’t think of a better thing to do with my free time.

Today is a day for politics

President Obama made comments last Friday in Fort Myers, Florida, about the Aurora theater shooting in Colorado. Here’s an excerpt of what he had to say:

So, again, I am so grateful that all of you are here. I am so moved by your support. But there are going to be other days for politics. This, I think, is a day for prayer and reflection.

This makes no sense. Actually, it’s offensive. When is it a day for politics, President Obama? And why are we treating this tragedy like an act of nature?

When a guy gets enough ammunition shipped to him legally, through the U.S. Post Office, to perform a massacre, and he rigs his house with sophisticated booby traps over months of preparation, we can safely say two things. First, this guy was absolutely insane, and second he had all of the resources available to him to kill dozens of people.

I can understand why, for the families of the victims, their therapists or priests may ask them to accept this fatalistically – they can’t get their loved one back. But as a nation, we should not be willing to be so passive in the face of what is obviously a fucked up system. We can imagine, I hope, a culture where it’s a wee bit more difficult to massacre innocent people if and when you decide that’s a good idea.

If you’re in doubt that this system is skewed towards the madman, keep in mind that the uninsured Aurora shooting victims are at risk of debtor’s prison in this country.

It begs the question of why we’ve become so inured to bad politicians. Notice I’m not saying inured to violence and random shootings, because we’re not, actually. We are all horrified, but in the face of such tragedy we shrug our shoulders and say stuff about the fact that there’s nothing we can do. Because that’s what our politicians say.

I’ll draw an analogy between this and the financial crisis, which is ongoing and could be getting worse. We often hear passive, third person narratives coming from our politicians and central bankers, who talk about the bankrupt banks and the corruption like there’s nothing we can actually do to fix this. Again, acts of nature.

Bullshit. These guys have been paid off by bank lobbyists and told to act impotent. They are following orders. Our country deserves better than this leadership, whose politicians give money to banks, which they turn around and use to buy off politicians. As Neil Barofsky said in his new book:

“The suspicions that the system is rigged in favor of the largest banks and their elites, so they play by their own set of rules to the disfavor of the taxpayers who funded their bailout, are true,” Mr. Barofsky said in an interview last week. “It really happened. These suspicions are valid.”

I’d like to separate, for a moment, two issues. First, what we have come to expect from Obama, who gave us such hope when he was elected. Second, what we deserve – what we should expect from a politician who cares about people and doing the right thing.

There’s a huge difference, but let’s not lose sight of that second thing. That’s when I turn from pissed to bitter, and I really don’t want to be bitter.

This is a day for politics, President Obama, so step it up. I’m not giving up hope that someone, though probably not you, can deliver it to us.

A call to Occupy: we should listen.

Yesterday a Bloomberg View article was published, written by Neil Barofsky.

In case you don’t remember, Barofsky was the special inspector general of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which meant he was in charge of watching over TARP until he resigned in February 2011. And if you can judge a man by his enemies, then Barofsky is doing pretty well by being cussed out by Tim Geithner.

The Bloomberg View article was an excerpt from his new book, which comes out July 24th and which I’m going to have to find time to read, because this guy knows what’s going on and the politics behind possible change.

In the article, Barofsky tears through some of the most obvious and ridiculous shenanigans that the Obama administration and the Treasury have been up to in preserving the status quo whereby the banks get bailed out and the average person pays. In order, he obliterates:

- Obama’s HAMP project: “with fewer than 800,000 ongoing permanent modifications as of March 31, 2012, a number that is growing at the glacial pace of just 12,000 per month.”

- The recent mortgage settlement: “In return for what was touted as a $25 billion payout, the banks received broad immunity from future civil cases arising out of their widespread use of forged, fraudulent or completely fabricated documents to foreclose on homeowners.” and “As a result, the settlement will actually involve money flowing, once again, from taxpayers to the banks.”

- The recent so-called Task Force for investigating toxic mortgage practices: “it seems unlikely that an 11th-hour task force will result in a proliferation of handcuffs on culpable bankers.”

- The Dodd-Frank Bill: “…the market distortions that flow from the presumption of bailout may have gotten worse. By failing to alter this presumption, Dodd-Frank may have inadvertently sowed the seeds for the next financial crisis.”

- Specifically, the Volcker Rule, where he quotes a milquetoast Geithner: `“We’re going to look at all the concerns expressed by these rules,” he said. “It is my view that we have the capacity to address those concerns.”’ – Barofsky draws a line directly from Geithner to the conclusion of Senator Levin, `“Treasury are willing to weaken the law.”’ Barofsky here highlights out the most basic problem we face, namely that regulators are suckling from their Wall Street masters: “Indeed, words like Geithner’s, when accompanied by actions such as the Fed’s authorization of the largest banks to release capital, send what should be a clear message. We may be in danger of quickly returning to the pre-crisis status quo of inadequately capitalized banks that take outsized risks while being coddled by their over-accommodating regulators. A repeat of the financial crisis would soon be upon us.”

- Finally, he gets on my favorite riff about TARP, namely that it’s not about the money being paid back, it’s about the risk that we’ve taken on as a nation.

But what’s most interesting to me about the article is the fact that he’s not proposing a political solution to the unbelievably unbalanced distribution of resources. Probably this is because the political power is so firmly entrenched and because it is so firmly corrupt that there’s no use barking up that tree. Instead, he is asking for Occupy and other popular movements to step it up. The article ends:

The missteps by Treasury have produced a valuable byproduct: the widespread anger that may contain the only hope for meaningful reform. Americans should lose faith in their government. They should deplore the captured politicians and regulators who distributed tax dollars to the banks without insisting that they be accountable. The American people should be revolted by a financial system that rewards failure and protects those who drove it to the point of collapse and will undoubtedly do so again.

Only with this appropriate and justified rage can we hope for the type of reform that will one day break our system free from the corrupting grasp of the megabanks.

The question I have is, will we need yet another financial crisis to get this done? (Not that I think one is far off- the banning of short selling recently by Spain and Italy is a desperate move, kind of like throwing in the towel and admitting you’d rather openly manipulate markets than let people have honest opinions.)

I for one think we’ve got plenty of evidence right now, and I’m outraged. But maybe not everyone is, and I take responsibility for that.

I think my job now, as an Occupier, is to make sure people understand that these decisions and speeches made at the Treasury and the White House are directly related to people illegally losing their homes and jobs and town services and having their pensions rewritten after they’ve reached retirement age. I absolutely believe that, if people knew all of those connections, we’d have an enormous number of people ready to occupy and the political power to do something.

Center for Popular Economics Summer Institute 2012

I’ll going to be giving a plenary talk on Tuesday, July 24th at the CPE Summer Institute 2012, which is being held this summer at Columbia the week of July 23rd – July 27th. I’ll be joined by Richard Wolff, an economist, radio show host, and author of multiple books, most recently Occupy the Economy. You can register for the Institute here (sliding scale).

The Summer Institute open to non-experts to teach them about the financial system and economics. They have two core courses, one based in the U.S. and the other international. From their web page:

The U.S. Economy/ Topics include

» Roots of the economic meltdown and solutions

» Speculation, finance and housing bubbles

» Economy, race, class and gender

» Economic histories – from personal to global

» Labor and jobs

» Democratizing the Federal Reserve and banks.

» Economic alternatives, socialism and the solidarity economy

The International Economy/ Topics include

» Roots of the economic meltdown and solutions

» Brief history of the global economy

» International trade, production and finance

» The IMF, World Bank, WTO

» Global climate change and the environment

» Creating a new world economy

In addition to hosting this cool and open Summer Institute, the Center for Popular Economics also recently came out with a booklet explaining some economic history of the U.S. written for the non-expert; take a look here.

I’m about halfway through, and I’ve spotted things you usually don’t see in economics texts you might read in high school, such as the following phrase:

So What Caused This Crisis?

Neoliberal capitalism has had three features that both explain how it promoted 25 years of economic expansions and why it led to a massive crisis in 2008. First, inequality grew rapidly, as profits rose while workers’ wages actually fell. From 1979 to 2007, the average inflation-corrected hourly wage of non-supervisory workers declined by 1 percent, while inflation-corrected nonfinancial corporate profits after taxes rose by a remarkable 255 percent. While surging profits pleased the capitalists, it brought a problem: who could buy the growing output that comes with economic expansion? The solution was debt. Somehow, people would have to borrow more and more if a form of capitalism that brings skyrocketing profits and falling wages was to function.

I think it would be cool to have a typical high school “history of economics” text side by side with this one, and have students read both and argue them.

I’m going to try to go to as much of the Summer Institute as I can as a student. I hope I see you there!

Is a $100,000 pension outrageous?

There are lots of stories coming out recently about how public workers, typically police or firefighters, are retiring with “outrageous” pensions of $100,000. Here’s one from the Atlantic. From the article:

That doesn’t frustrate Maviglio, who insists that “people who put their lives on the line every day deserve a secure retirement.” But do they “deserve” more than twice the US median income? Do they “deserve” the sum the average California teacher makes, plus $32,000? Do they “deserve” pensions far higher than the highway workers whose jobs are much more dangerous? These aren’t idle questions, given the public safety worker retirements we can expect in the near future.

Okay, let’s go there. If the median income in the country is 38,000, then $100,000 is a lot. But the median income in the communities where these retired firefighters live is sometimes much higher. For example, in Orange County, where the pension system is getting lots of flak, the median incomes can be seen here. In only one community out of is it below $50,000, and in 8 it’s above $100,000. So if you look at it that way then it doesn’t seem so outrageous.

And maybe we should be paying our teachers and our highway workers more, for that matter.

Point #1: California is a rich state, and it costs a lot of money to live there.

Now let’s move on to articles like this, which frame the issue in a very specific way. The title:

Police and Firefighter Pensions Threaten Government Solvency

How about all the other things that have contributed? Why are we blaming these guys, who have worked all their lives to protect their community? Why aren’t we blaming the mafia behind the muni bond deals, or sometimes even the local politicians as well?

Point #2: This is all a political blame game, trying to manipulate you from thinking about who are the actual crooks behind the scenes here.

My momma always said double down, and this is the ultimate double-down opportunity. Instead of looking for where the money went, or why it was handled so badly, we are going to blame the guys on taking the boring public servant job, and doing it for their adult lives, and trying to retire. Basically, we are blaming them for being right, for making the better choice between public and private.

Point #3: They made the right choice and we can’t swallow it because we thought our whole lives they were suckers for working in public service instead of in finance.

And what about that? Why do we compare $100,000 pensions to median incomes but not to golden parachute retirement packages of failing CEOs? Where’s the real outrage? Here’s another list of some seriously outrageous golden parachutes.

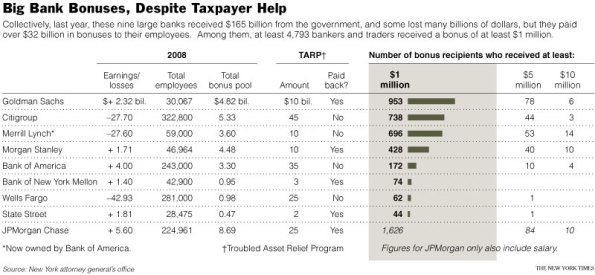

Maybe it’s because we feel like private pay is not our business, as taxpayers. It’s a different arena, and we have no right to judge. Let me remind you then that we taxpayers paid for bonuses at too-big-to-fail banks:

Point #4: These pensions don’t look very big when you compare them to what happens in the private sector.

And yes, I’m talking about the extreme cases, but so does everyone else when they talk about “outrageous pensions”, so it’s extreme-case apples to extreme-case apples.

The basic unit is risk

Today I’m going to gush over two excellent blog posts I read recently written over at Interfluidity. But first I’m going to state a pet theory of mine about what units we talk in.

In a mathematical sense, units make no difference. If I give you measurements in inches rather than feet, all I’m doing is multiplying by 12. If I say something in French rather than German, all I need is a translation and we’re talking about equivalent information.

But in a psychological sense, a choice of units can make an enormous different. Things sound bigger in inches, and sometimes you barely understand French and can make bad guesses.

I’d argue that speaking in terms of wealth is a mistake. We should instead speak in terms of risk. It’s a different unit, and it’s harder to quantify, but I think risk is what we actually care about. I claim it’s more basic than money.

For example, why are we afraid of not having money? It’s because we run the risk of not having resources to eat, sleep, or get medicine or treatment when we’re sick. If we didn’t have fears about this stuff then people would have a very different relationship to money. The underlying issue is the risk, not the money.

Financial markets putatively push around money, but I’d argue that why they exist and how they actually function is as a way to spread around risk. That’s why the futures market was developed, for farmers to have less risk, and that’s why the credit default swap market was created, to put a price on risk and sell it to people who think they can handle it.

It also kind of explains, to me at least, the weirdness of super rich people- people who have more money than they can ever use. Why do they continue to collect money so aggressively when they already have so much? My guess is that they are confused about their units- they think all their problems can be solved by money, but their remaining actual problems are problems of risk that can’t be controlled by money. Things like the fact that we all get old and die. Things like that people don’t like you if you’re an asshole or that your wife may leave you. These are risks that most people never get to the point of trying to solve through money, because they’re still stuck in a different part of reality where inflation could screw their retirement plans. But for super rich weirdos, we have the Singularity University where you get to learn how to transcend humanity and live forever.

I’m not making a deep statement here. I’m just suggesting that, next time you hear of a plan by politicians or regulators or Wall Street bankers, think not about where the money is flowing but where the risk is flowing.

A perfect example is when you hear bankers say they “paid back all the bailout”; perhaps, but note that the risk went to the taxpayers and is firmly fixed here with us. We haven’t given the risk back to the banks, and there doesn’t seem to be a plan afoot to do so.

Which gets me to Interfluidity’s first plan, namely to have the government protect up to $200,000 of an individual’s savings from inflation.

Now, on the face of it, this plan is not all that protective of the 99%, because it’s definitely benefiting people who have savings, where we know that the lowest 25% or so of the population is in net debt. Only people with savings to protect can actually benefit.

But if you think about it more, it is good for people like my parents, whose retirement from a state school does not rise with inflation, or more generally for people who have a fixed savings put aside for retirement. And it isn’t at all good for very rich people, who would see a benefit only on a small percentage of their savings (assuming it is possible, as Interfludity says it is, to outlaw the bundling of these inflation-protected accounts like some people now bundle life insurance policies).

Most economic policies in this country are made to benefit rich people, and are defended by saying we need to protect middle-class people nearing retirement with a modest nest-egg. As Interfluidity said, those middle guys are used as “human shields”. Very few policies go into to the weeks sufficiently to figure out how to protect that group without having outsized benefits at the top.

Said in terms of risk, this plan is pushing inflation risk to people who can handle it, and removing it from people who are extremely vulnerable to it.

Which brings me to the second post I want to rave about, namely this one in which Interfluidity dissects the lack of political will in the face of the current depression. From the post:

We are in a depression, but not because we don’t know how to remedy the problem. We are in a depression because it is our revealed preference, as a polity, not to remedy the problem. We are choosing continued depression because we prefer it to the alternatives.

The reason? Because no matter how much someone might say that we care about the middle class, the truth is we are protecting rich people from the risk of getting poor. We have, as he says, a population with individual power roughly weighted in proportion to their wealth (or, to be consistent with my theme, inversely proportional to their risk), and when you take a vote with those weightings, we get a “weighted consensus view,” manifested among the macroeconomists in charge of this stuff, that we should avoid inflation at all costs (ironic that the people with the least risk are also the people with the most influence).

In order to remedy this situation, we’d need to implement something like the inflation-protected bank accounts up to $200,000 for the individual. Then the weighted consensus may change – we might instead actually pull for a policy that would have some risk for inflation and would also possible create jobs.

But of course, in order to implement such a policy, we’d need to have the political will to change the risk profile, which goes back to the weighted consensus thing. Keeping in mind that this policy would push the risk to rich people, I’m guessing they wouldn’t vote for it.

On the other hand, smallish savers would. So it’s not a mathematical impossibility, because there may be enough people in favor of the inflation-protection plan to make it happen, and then the second question, of how to get us out of the current depression, would be easier to address. I’m definitely in favor of trying.